Oxford University Press's Blog, page 747

October 24, 2014

Coded letters reveal an illicit affair and a woman of substance

When an old friend told me he had saved the former Edward Everett Hale house in Matunuck, Rhode Island from demolition and gifted it to a local historical society with an endowment fund for its restoration, I remembered there was a significant collection of E. E. Hale letters at the Library of Congress that might throw light on the house. How could I have guessed this would lead me to uncovering the revered minister’s decades-long love affair with a forgotten, much younger and truly remarkable woman named Harriet E. Freeman?

First I had to unlock the code the writers used in passages throughout some 3,000 surviving letters. As I transcribed the letters, I recognized the “code” as a defunct shorthand, which I traced to its inventor, Thomas Towndrow. Hale taught himself this shorthand while a student at Harvard, and Towndrow’s 1832 textbook became my “Rosetta Stone” to unlocking an intimate, sometimes passionate, and mutually supportive relationship — the nature of which was concealed by the two of them, their families, and generations of Hale biographers.

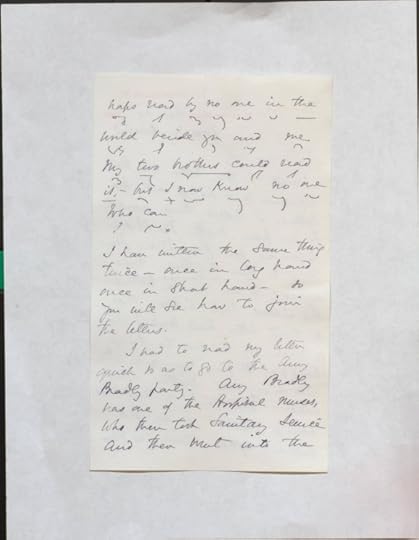

Hale to Freeman, September 29, 1884. Hale-Freeman Special Correspondence, Hale Family Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

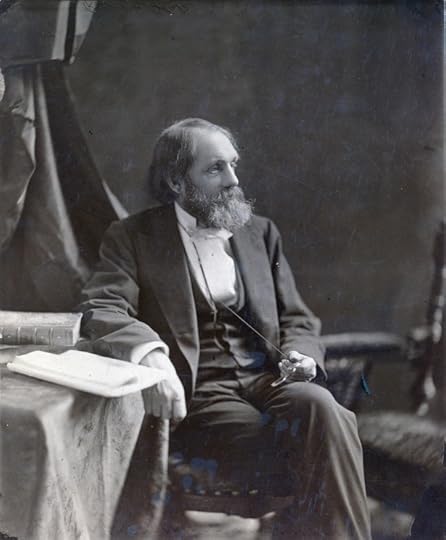

Hale to Freeman, September 29, 1884. Hale-Freeman Special Correspondence, Hale Family Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. Edward Everett Hale in about 1884. Harriet E. Freeman Papers, Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School.

Edward Everett Hale in about 1884. Harriet E. Freeman Papers, Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School. Fifteen-year-old Hattie Freeman and her cousin Helen Atkins, 1862. Courtesy of Phoebe Bushway.

Fifteen-year-old Hattie Freeman and her cousin Helen Atkins, 1862. Courtesy of Phoebe Bushway.Hale’s public life and career are well documented, but who was this Harriet Freeman? As I discovered from reminiscences in the letters, Hale’s special relationship with Freeman had its origins in his close friendship with the wealthy Freeman family, his parishioners since her teenage years. In her early twenties, Freeman began working as a volunteer in Hale’s church, the South Congregational Church in Boston’s South End, just a block away from the Freeman’s town house. Soon, she became his favorite literary amanuensis, to whom he dictated more than half of his sermons and a significant number of his fifty books and countless articles. Their coded expressions of devotion to each other in the letters that begin in 1884, when Hale, married with six surviving children, was 62 and Freeman 37, often seem “over-the-top” in typical Victorian fashion, but the longhand portions of the letters are rich in evidence of their shared intellectual and activist interests and love of the outdoors. Quite simply, they were soul mates.

Freeman and Hale were photographed in adjoining canoes on Wash Pond behind the Hales’ summer house during her late summer 1887 stay at Matunuck. Copy print in Harriet E. Freeman Papers, Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School.

Freeman and Hale were photographed in adjoining canoes on Wash Pond behind the Hales’ summer house during her late summer 1887 stay at Matunuck. Copy print in Harriet E. Freeman Papers, Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School.Far from being just an adjunct to an older man’s life, Freeman fashioned a full and useful life of her own. She had a passion for botany and geology, which she studied at the Teacher’s School of Science (a venture of the Boston Society of Natural History and Boston Tech, later MIT) and then as a special student at Boston Tech, when she participated in multiple field trips in North America. Active in leadership roles in a number of the women’s clubs and organizations that pursued philanthropy and reform in women’s higher education and human rights, she also became a member of the Appalachian Mountain Club once women were allowed to join in 1879. Spending her summers in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, where Hale joined her for the month of August and other shorter visits, she was an activist for preserving the severely threatened forests of the region, persuading Hale to lend his authority to the cause when he became chaplain to the US Senate in 1904.

Freeman, at second left, greets a cousin and is accompanied by her naturalist traveling companion and friend Emma Cummings and nephew Fred Freeman at the start of a week-long hike in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains in July 1902. From an album of photographs documenting the hike, courtesy of Alan Lowe.

Freeman, at second left, greets a cousin and is accompanied by her naturalist traveling companion and friend Emma Cummings and nephew Fred Freeman at the start of a week-long hike in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains in July 1902. From an album of photographs documenting the hike, courtesy of Alan Lowe.The story of Harriet Freeman and Edward Hale is valuable for two reasons: it sheds new light on the already celebrated E. E. Hale and it comprehensively documents the life of a truly remarkable woman. I began by thinking that “Hattie” could only be overshadowed by the overpowering legend and charismatic personality of Edward Everett Hale. Instead, I found multiple reasons why he felt she transformed his life. At last, and 84 years after her death, the formerly obscure Harriet Freeman is recognized with a profile in American National Biography Online.

Sara Day at Harriet Freeman’s grave in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sara Day at Harriet Freeman’s grave in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.The post Coded letters reveal an illicit affair and a woman of substance appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBiologists that changed the worldThe Oxford DNB at 10: biography and contemporary historyRita Angus, Grove Art Online

Related StoriesBiologists that changed the worldThe Oxford DNB at 10: biography and contemporary historyRita Angus, Grove Art Online

Navanethem Pillay on what human rights are for

Today is United Nations Day, celebrating the day that the UN Charter came into force in 1945. We thought it would be an excellent time to share thoughts from one of their former Commissioners to highlight the work this organization undertakes. The following is an edited extract by Navanethem Pillay, former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, from International Human Rights Law, Second Edition.

I was born a non-white in apartheid South Africa. My ancestors were sugarcane cutters. My father was a bus driver. We were poor.

At age 16 I wrote an essay which dealt with the role of South African women in educating children on human rights and which, as it turned out, was indeed fateful. After the essay was published, my community raised funds in order to send this promising, but impecunious, young woman to university.

Despite their efforts and goodwill, I almost did not make it as a lawyer, because when I entered university during the apartheid regime everything and everyone was segregated. However, I persevered. After my graduation I sought an internship, which was mandatory under the law; it was a black lawyer who agreed to take me on board, but he first made me promise that I would not become pregnant. And when I started a law practice on my own, it was not out of choice but because no one would employ a black woman lawyer.

Yet, in the course of my life, I had the privilege to see and experience a complete transformation in my country. Against this background it is no surprise that when I read or recite Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, I intimately and profoundly feel its truth. The article stated that: ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood’.

The power of rights made it possible for an ever-expanding number of people, people like myself, to claim freedom, equality, justice, and well-being.

Human rights underpin the aspiration to a world in which every man, woman, and child lives free from hunger and protected from oppression, violence, and discrimination, with the benefits of housing, healthcare, education, and opportunity.

Yet for too many people in the world, human rights remain an unfulfilled promise. We live in a world where crimes against humanity are ongoing, and where the most basic economic rights critical to survival are not realized and often not even accorded the high priority they warrant.

The years to come are crucial for sowing the seeds of an improved international partnership that, by drawing on individual and collective resourcefulness and strengths, can meet the global challenges of poverty, discrimination, conflict, scarcity of natural resources, recession, and climate change.

United Nations Building. Photo by Ashitaka San. CC BY-NC 2.0 via mononoke Flickr.

United Nations Building. Photo by Ashitaka San. CC BY-NC 2.0 via mononoke Flickr.In 2005, the world leaders at their summit created the UN Human Rights Council, an intergovernmental body which replaced the much-criticized UN Human Rights Council, with the mandate of promoting ‘universal respect for the protection of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all’. The Council began its operations in June 2006. Since then, it has equipped itself with its own institutional architecture and has been engaged in an innovative process known as the Universal Periodic Review (UPR). The UPR is the Council’s assessment at regular intervals of the human rights record of all UN member states.

In addition, at each session of the Council several country-situations are brought to the fore in addresses and documents delivered by member states, independent experts, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Today, the Office of the High Commissioner is in a unique position to assist governments and civil society in their efforts to protect and promote human rights. The expansion of its field offices and its presence in more than 50 countries, as well as its increasing and deepening interaction with UN agencies and other crucial partners in government, international organizations, anad civil society are important steps in this direction. With these steps we can more readily strive for practical cooperation leading to the creation of national systems which promote human rights and provide protection and recourse for victims of human rights violations.

In the final instance, however, it is the duty of states, regardless of their political, economic, and cultural systems, to promote and protect all human rights and fundamental freedoms. Our collective responsibility is to assist states to fulfil their obligations and to hold them to account when they do not.

The post Navanethem Pillay on what human rights are for appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPreparing for the 2014 FDI International Arbitration MootUnderstanding virusesRipe for retirement?

Related StoriesPreparing for the 2014 FDI International Arbitration MootUnderstanding virusesRipe for retirement?

Navanethem Pillay on what are human rights for

Today is United Nations Day, celebrating the day that the UN Charter came into force in 1945. We thought it would be an excellent time to share thoughts from one of their former Commissioners to highlight the work this organization undertakes. The following is an edited extract by Navanethem Pillay, former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, from International Human Rights Law, Second Edition.

I was born a non-white in apartheid South Africa. My ancestors were sugarcane cutters. My father was a bus driver. We were poor.

At age 16 I wrote an essay which dealt with the role of South African women in educating children on human rights and which, as it turned out, was indeed fateful. After the essay was published, my community raised funds in order to send this promising, but impecunious, young woman to university.

Despite their efforts and goodwill, I almost did not make it as a lawyer, because when I entered university during the apartheid regime everything and everyone was segregated. However, I persevered. After my graduation I sought an internship, which was mandatory under the law; it was a black lawyer who agreed to take me on board, but he first made me promise that I would not become pregnant. And when I started a law practice on my own, it was not out of choice but because no one would employ a black woman lawyer.

Yet, in the course of my life, I had the privilege to see and experience a complete transformation in my country. Against this background it is no surprise that when I read or recite Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, I intimately and profoundly feel its truth. The article stated that: ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood’.

The power of rights made it possible for an ever-expanding number of people, people like myself, to claim freedom, equality, justice, and well-being.

Human rights underpin the aspiration to a world in which every man, woman, and child lives free from hunger and protected from oppression, violence, and discrimination, with the benefits of housing, healthcare, education, and opportunity.

Yet for too many people in the world, human rights remain an unfulfilled promise. We live in a world where crimes against humanity are ongoing, and where the most basic economic rights critical to survival are not realized and often not even accorded the high priority they warrant.

The years to come are crucial for sowing the seeds of an improved international partnership that, by drawing on individual and collective resourcefulness and strengths, can meet the global challenges of poverty, discrimination, conflict, scarcity of natural resources, recession, and climate change.

United Nations Building. Photo by Ashitaka San. CC BY-NC 2.0 via mononoke Flickr.

United Nations Building. Photo by Ashitaka San. CC BY-NC 2.0 via mononoke Flickr.In 2005, the world leaders at their summit created the UN Human Rights Council, an intergovernmental body which replaced the much-criticized UN Human Rights Council, with the mandate of promoting ‘universal respect for the protection of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all’. The Council began its operations in June 2006. Since then, it has equipped itself with its own institutional architecture and has been engaged in an innovative process known as the Universal Periodic Review (UPR). The UPR is the Council’s assessment at regular intervals of the human rights record of all UN member states.

In addition, at each session of the Council several country-situations are brought to the fore in addresses and documents delivered by member states, independent experts, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Today, the Office of the High Commissioner is in a unique position to assist governments and civil society in their efforts to protect and promote human rights. The expansion of its field offices and its presence in more than 50 countries, as well as its increasing and deepening interaction with UN agencies and other crucial partners in government, international organizations, anad civil society are important steps in this direction. With these steps we can more readily strive for practical cooperation leading to the creation of national systems which promote human rights and provide protection and recourse for victims of human rights violations.

In the final instance, however, it is the duty of states, regardless of their political, economic, and cultural systems, to promote and protect all human rights and fundamental freedoms. Our collective responsibility is to assist states to fulfil their obligations and to hold them to account when they do not.

The post Navanethem Pillay on what are human rights for appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPreparing for the 2014 FDI International Arbitration MootUnderstanding virusesRipe for retirement?

Related StoriesPreparing for the 2014 FDI International Arbitration MootUnderstanding virusesRipe for retirement?

Understanding viruses

The reemergence of the Ebola epidemic provokes the kind of primal fear that has always gripped humans in the face of contagious disease, even though we now know more about how viruses work than ever before. Viruses, like all living organisms, are constantly evolving. This ensures that new viruses and their diseases will always be with us.

For thousands of years, people knew little about the “plagues” that afflicted them and, despite the impossibility to define causality, there were many attempts to explain how they happened.

Thucydides wrote in the History of the Peloponnesian War during the plague of Athens in 431 BCE that

“no pestilence of such extent nor any scourge so destructive of human lives is on record anywhere. For neither were physicians able to cope with the disease, since they at first had to treat it without knowing its nature, the mortality among them being greatest because they were most exposed to it, … And the supplications made at sanctuaries, or appeals to oracles and the like, were futile, and at last men desisted from them, overcome by the calamity.”

Even two thousand years later, scientists were at a loss to explain the workings of contagion. William Harvey, who described the circulation of blood in humans and is quoted in The Works of William Harvey by Tr. Robert Wills, wrote in 1653,

“So do I hold it scarcely less difficult to conceive how pestilence or leprosy should be communicated to a distance by contagion, by (an)…element contained in woolen or linen things, household furniture, even the walls of a house … How, I ask, can contagion, long lurking in such things … after a long lapse of time, produce its like nature in another body? Nor in one or two only, but in many, without respect of strength, sex, age, temperament, or mode of life, and with such violence that the evil can by no art be stayed or mitigated.”

In the absence of information, humankind resorted to any number of explanations for the origins of disease. Physicians, natural philosophers, and religious figures hypothesized causes of contagious diseases based on their view of the way the world worked. Disease theories became part of the discourse about the causes of events such as earthquakes, lightning and the movement of the planets.

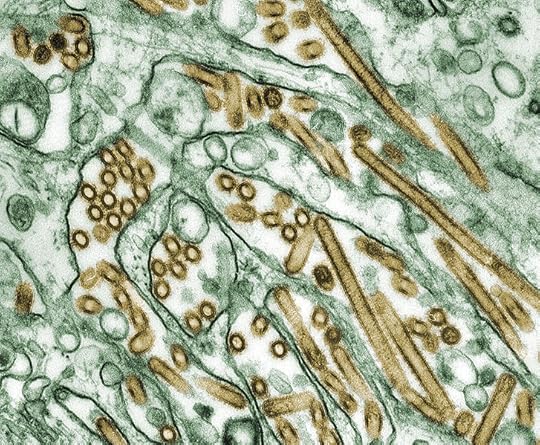

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses. virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Image Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses. virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Image Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Viruses are a fascinating group of entities that infect humans, other animals, plants, and bacteria. Their presence was anticipated when on 1 April 1717 Lady Mary Montagu, the wife of the British Ambassador to Turkey, wrote to a friend in England about smallpox. She was delighted to report that the disease did so little mischief. Why? Because an old woman would come with a “nutshell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox,” (fluid derived from poxes) and immunize the children. The children would suffer some slight fever but soon recover, possibly never to contract the disease. What remained unknown was the contents of the fluid used by the old women to inoculate the children.

Near the close of the 19th century, scientists had come to understand that many plant diseases were caused by fungi, while a number of human diseases, such as tuberculosis, were caused by bacteria. But viruses remained a mystery.

That changed from the late 1880s to 1917, as the result of the discovery of contagious diseases whose causes could not be isolated or observed with ordinary microscopes. These included a contagion of tobacco plants, called mosaic disease, a disease of cattle (foot-and-mouth disease), yellow fever in humans, and another disease that attacked bacteria. It turned out they were all caused by viruses.

But the study of viruses posed unique challenges. Viruses are not cells like pathogenic bacteria or fungi which can multiply independently in their hosts or on artificial media. The agent that caused flu could not be grown in culture, and there was no experimental animal that could be infected. It was also impossible for researchers to visualize the agent of disease. After the great flu epidemic of 1918, scientists made numerous attempts to isolate the agent, but it was not until 1933 that three British investigators discovered that ferrets could be infected by nasal washings from patients with the disease. Thus they proved that an entity contained in nasal material could transmit the disease.

The mysteries of viruses were largely revealed by investigators working with those that infect bacteria. These viruses attracted the attention of researchers who speculated that they might lead to discoveries in the field of genetics. They worked with a virus that infects E. coli — which lives in the intestinal tracts of humans — and, while taking over the machinery of the bacterial cell, causes these bacteria to blow open, releasing hundreds of viral particles. Chemical analysis revealed their composition to be DNA and proteins. These studies contributed significantly to the conclusion that DNA is the genetic material of cellular life.

We now know that viruses that infect humans have their origin in animal populations that are in close contact with humans. Many of the flu viruses originate in Southeast Asia where bird and swine populations live in close proximity to humans. The viruses undergo mutations so that humans must be immunized each year against new strains. The rapid production of astronomical numbers of Ebola virus ensures that new strains will be constantly produced.

We also know that all viruses are composed of DNA or RNA and proteins. Ebola, influenza, polio, and AIDS are caused by RNA viruses. The virus that infects tobacco plants also is an RNA virus. Because we know how they work, we have had some success in interfering with the disease process with various drugs.

All of these modern procedures contribute to understanding the cause of disease. Humankind has long believed that understanding would lead to cures. As Hippocrates stated 2,500 years ago, “To know the cause of a disease and to understand the use of the various methods by which disease may be prevented amounts to the same thing in effect as being able to cure.”

And yet, as we have seen with Ebola, understanding the cause is not always the same as curing. We have arrived at a point in the 21st century where we can mitigate some contagious diseases and prevent other catastrophic diseases such as smallpox. But others will be with us now and in the future, for contagion is a general biological phenomenon, a natural phenomenon. Contagious agents evolve like all living organisms and constantly challenge us to understand their origin, spread and pathology.

Headline Image: Ebola virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Image Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Understanding viruses appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow much are nurses worth?Ripe for retirement?What will it take to reduce infections in the hospital?

Related StoriesHow much are nurses worth?Ripe for retirement?What will it take to reduce infections in the hospital?

Ripe for retirement?

In 1958, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the US ambassador to the United Nations, summarized the role of the world organization: “The primary, the fundamental, the essential purpose of the United Nations is to keep peace. Everything which does not further that goal, either directly or indirectly, is at best superfluous.” Some 30 years later another ambassador expressed a different view. “In the developing countries the United Nations… means environmental sanitation, agricultural production, telecommunications, the fight against illiteracy, the great struggle against poverty, ignorance and disease,” remarked Miguel Albornoz of Ecuador in 1985.

These two citations sum up the basic dilemma of the United Nations. It has always been burdened by high expectations: to keep peace, fix economic injustices, improve educational standards and combat various epidemics and pandemics. But inflated hopes have been tempered by harsh realities. There may not have been a World War III but neither has there been a day’s worth of peace on this quarrelsome globe since 1945. Despite all the efforts of the various UN Agencies (such as the United Nations Development Programme) and related organizations (like the World Bank), there exists a ‘bottom billion’ that survives on less than one dollar a day. The average lifespan in some countries barely exceeds thirty. According to UNESCO 774 million adults around the world lacked basic literacy skills in 2011.

Given such a seemingly dismal record, it is worth asking whether the UN has outlived its usefulness. After all, the organization turns 69 today (October 24th, 2014), a time when many citizens in the industrialized world exchange the stress of daily jobs for leisurely early retirement. Has the UN not had enough of a chance to keep peace and fix the world’s problems? Isn’t the obvious conclusion that the organization is a failure and the earlier it is scrapped the better?

The answer is no. The UN may not have made the world a perfect place but it has improved it immensely. The UN provides no definite guarantees of peace but it has been – and remains – instrumental for pacifying conflicts and enabling mediation between adversaries. Its humanitarian work is indispensable and saves lives every day. In simple terms: if the UN – or the various subsidiary organization that make up the UN – suddenly disappeared, lives would be lost and livelihoods would be endangered.

Henry Cabot, Jr. By Harris & Ewing. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Henry Cabot, Jr. By Harris & Ewing. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsIn fact, the real question is not whether the UN has outlived its usefulness, but how can the UN perform better in addressing the many tasks it has been charged with?

The answer is twofold. First, the UN needs to be empowered to do what it does best. Today, for example, one of the most pressing global challenges is the potential spread of the Ebola virus. Driven by irrational fear, politicians in a number of countries suggest closing borders in order to safeguard their populations. But the only realistic way of addressing a virus that does not know national borders is surely international collaboration. In practical terms this means additional support for the World Health Organization (WHO), the only truly global organization equipped to deal with infectious diseases. But the WHO, much like the UN itself, is essentially a shoestring operation with a global mandate. Its budget in 2013 was just under 4 billion dollars. The US military spent that amount of money in two days.

Second, the UN must become better at ‘selling’ itself. Too much of what the UN and its specialized agencies do around the world is simply covered in fog. What about child survival and development (UNESCO)? Environmental protection (UNEP) and alleviation of poverty (UNDP)? Peaceful uses of atomic energy (IAEA)? Why do we hear so little about the UN’s (or the International Labour Organization’s) role in improving workers’ rights? Does anyone know that the UNHCR has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize twice (out of a total of 11 Nobel Peace Prizes awarded to the UN, its specialized agencies, related agencies, and staff)? It’s not a bad CV!

We tend to hear, ad nauseam, that the 21st century is a globalized one, filled with global problems but apparently lacking in global solutions. What we tend to forget is the simple fact that there exists an organization that has been addressing such global challenges – with limited resources and without fanfare – for almost seven decades.

Indeed, it seems that in today’s world the UN is more relevant than ever before. At 69 it is certainly not ripe for retirement.

Featured image credit: United Nations Flags, by Tom Page. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Ripe for retirement? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow much do you know about Alexander the Great?Are we alone in the Universe?What’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?

Related StoriesHow much do you know about Alexander the Great?Are we alone in the Universe?What’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?

October 23, 2014

Rita Angus, Grove Art Online

We invite you to explore the biography of New Zealand painter Rita Angus, as it is presented in Grove Art Online.

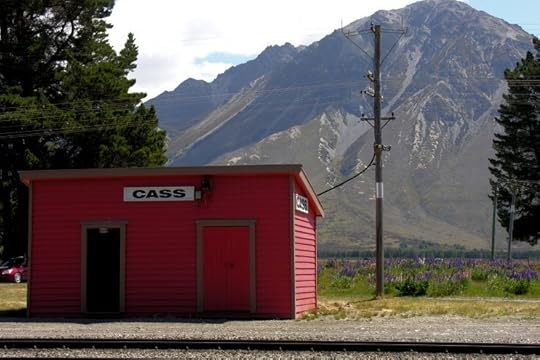

New Zealand painter. Angus studied at the Canterbury School of Art, Christchurch (1927–33). In 1930 she married the artist Alfred Cook (1907–70) and used the signature Rita Cook until 1946; they had separated in 1934. Her painting Cass (1936; Christchurch, NZ, A.G.) is representative of the regionalist school that emerged in Canterbury during the late 1920s, with the small railway station visualizing both the isolation and the sense of human progress in rural New Zealand. The impact of North American Regionalism is evident in Angus’s work of the 1930s and 1940s. However, Angus was a highly personal painter, not easily affiliated to specific movements or styles. Her style involved a simplified but fastidious rendering of form, with firm contours and seamless tonal gradations (e.g. Central Otago). Her paintings were invested with symbolic overtones, often enigmatic and individual in nature. The portrait of Betty Curnow (1942; Auckland, A.G.) has generated a range of interpretations relating both to the sitter, wife of the poet Allen Curnow, and its social context.

In her self-portraits, Angus pictured a complex array of often contradictory identities. In Self-portrait (1936–7; Dunedin, NZ, Pub. A.G.) she played the part of the urban, sophisticated and assertive ‘New Woman’. Amongst her most candid works are a series of nude self-portrait pencil drawings, while her watercolours also constitute an important body of work, ranging from portraits and landscapes to painstaking but striking botanical studies such as Passionflower (1943; Wellington, Mus. NZ, Te Papa Tongarewa). The watercolourTree (1943; Wellington, Mus. NZ, Te Papa Tongarewa) carries a sense of mystery, with its surreal stillness and emptiness. Angus’s ‘Goddess’ paintings are equally mysterious. A Goddess of Mercy (1945–7; Christchurch, NZ, A.G.) is an image of peace and harmony. Angus was a pacifist and a conscientious objector during World War II. In Rutu (1951; Wellington, Mus. NZ, Te Papa Tongarewa), she modelled the goddess on her own features, but created a composite figure, half Maori, half European, which suggests an ideal condition of bicultural harmony. The lotus flower held by Rutu reflects Angus’s interest in Buddhism. She thought the Goddess paintings were her most important, and it is on the basis of these works that Angus was hailed as a feminist by subsequent artists and writers.

Cass Station, Canturbury, which inspired Rita Angus’s painting, Cass. Photo by Phillip Capper. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Cass Station, Canturbury, which inspired Rita Angus’s painting, Cass. Photo by Phillip Capper. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. Angus aimed to evoke transcendental states of being, or a vision beyond mundane reality. In this respect her work connects to European modernism, more so than on the basis of any stylistic affinities. Nonetheless, Angus absorbed some of modernism’s formal innovations, notably degrees of simplification and flattening of form. Towards the end of her career, while she retained motifs based on observation, these were schematic and assembled into composite images, such as Flight(1968–9; Wellington, Mus. NZ, Te Papa Tongarewa). Her Fog, Hawke’s Bay (1966–8; Auckland, A.G.) manifests elements of the faceting and multiple viewpoints of Cubism. Angus’s hard-edged style influenced a younger generation of New Zealand painters, including Don Binney (b 1940) and Robin White.

Bibliography

Docking: Two Hundred Years of New Zealand Painting(Wellington, 1970), p. 146 Rita Angus (exh. cat. by J. Paul and others, Wellington, NZ, N.A.G., 1982) Rita Angus (exh. cat., ed. L. Bieringa; Wellington, N.A.G., 1983) Rita Angus: Live to Paint, Paint to Live (exh. cat. by V. Cochran and J. Trevvelyan; Auckland, C.A.G., 2001) V. Cochran and J. Trevelyan: Rita Angus: Live to Paint, Paint to Live(Auckland, 2001) M. Dunn: New Zealand Painting: A Concise History(Auckland, 2003), pp. 85–8 P. Simpson: ‘Here’s Looking At You: The Cambridge Terrace Years of of Leo Bensemann and Rita Angus’,Journal of New Zealand Art History, xxv (2004), pp. 23–32 J. Trevelyan: Rita Angus: An Artist’s Life(Wellington, 2008) Rita Angus: Life and Vision (exh. cat., ed. W. McAloon and J. Trevelyan; Wellington, Mus. NZ, Te Papa Tongarewa, 2008)The post Rita Angus, Grove Art Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA conversation with Dr. Steven Nelson, Grove Art Online guest editorDispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War IAn inside look at music therapy

Related StoriesA conversation with Dr. Steven Nelson, Grove Art Online guest editorDispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War IAn inside look at music therapy

Watching the watch people

A time-traveler, visiting from 1970s Britain, would be surprised by pretty much everything on the modern high street. While prestige brands such as Rolls Royce and Berry Bros. & Rudd have formed part of a much older landscape, the discriminating buyer of the Wilson and Heath eras would be astounded by the topsy-like growth of the modern luxury market. No longer the preserve of a privileged elite, myriad luxury brands now reach out to everyone. Specialist glossy magazines abound, for every interest, from hi-tech snowboards to waterproof smartphones — and the iPhone, in its regular updates, feeds a mass market appetite for the desirable luxury good. Apple has also spent years developing a related personal accessory — the iWatch — but for one group of discerning luxury buyers, this has proved to be a potentially disturbing phenomenon.

The market for luxury (or “high-end”) watches, in a world that naturally goes by a French title — haute horlogerie — has never been stronger. That market’s history has unfolded remarkably differently for participants in different countries. For the most tech-savvy punters — with funds enough for an iPhone — the rhetorical question posed of a fine Patek Philippe watch might be “why would I want such a single-function device?” Yet modern high-end brands can sell their entire output, and are coveted by collectors who own many valuable watches, yet perhaps leave them unworn, locked away safely, housed in boxes with motorized compartments that will keep the rotors of the automatic models turning and the lubrication properly distributed. The cult of the prestige watch has never been stronger, and one of its English bibles is QP, a magazine added by The Telegraph to its stable of luxury publications in 2013. And if there are bibles, so there is a temple, in that the Saatchi Gallery plays host each year to SalonQP, the showcase for haute horlogerie.

The phenomenon of the modern watch collector reflects the triumphant survival, rebirth, and stunning success of the Swiss watchmaking industry in particular, and is often credited to the intervention of one man — Nicolas Hayek — who rescued many heavily over-indebted brands from oblivion in the 1980s, and thereby saved a group of Swiss bankers’ bacon. The emergence of the popular Swatch at the popular end of the market underpinned the capacity of the high-end to recover its equilibrium and to forge forwards.

Swatch by Motor-Head. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Swatch by Motor-Head. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr. No such luck for the British market of the same period. Our time-traveler would recall the 1970s witnessing the last gasp of a small British watchmaking industry, born just twenty-five years earlier, in the wake of the Second World War. Preparation in the 1930s had seen firms such as S. Smith & Sons of Cricklewood forge alliances with Jaeger and LeCoultre, and these were vital at the outbreak of war, in securing deliveries from Switzerland of tools, complete watches, and a huge range of parts, including millions of tiny synthetic jewels, needed in every fine instrument across the cockpit of the Spitfire and Hurricane.

As such supplies continued throughout the war, generally through diplomatic smuggling, the realization crystallized that Britain required a larger capacity in light and fine engineering, leading to ambitious plans for the development of a post-war watch manufacturing capacity. With the backing of Stafford Cripps and Hugh Dalton, Attlee’s post-war Labour administration did indeed back the creation of a new industry, centred around Smiths, with factories in development areas of Wales and Scotland, offering much needed employment and generating vital foreign exchange.

But technology, as well as political backdrops and personalities, moved on. The demand for guided missile technology waxed as the need for mechanical fuzes for weapons waned. The watchmakers recalled Cripps committing to their support in the Commons, and believed a covenant had been established between government and the horological industry, in which tariffs and quantitative restrictions on foreign imports would remain in place and at effective levels, ad infinitum. They were wrong.

The affirmation of free-trade doctrine under the Conservative government of the 1950s saw the dismantling of the protectionism that had characterized the post-war Labour government. A long and painful demise of the newborn British watchmaking industry resulted. When Heath replaced Wilson, Smiths was already winding down its watch businesses, returning briefly to the historic practice of importing Swiss mechanisms, and simply adding its name to the dial.

Spitfire by johntrathome. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Spitfire by johntrathome. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr. Remarkably, however, a dream of establishing high-end watchmaking in the UK was nevertheless kept alive, not by industry, and not supported by government subsidy, tariffs, and restrictions. The principal guardian of the flame was the determined and eccentric genius George Daniels (1926–2011), now considered one of the finest watchmakers ever. His methods involved a significant element of handcraft and he made nearly every part of his limited series of watches, which have risen colossally in value since his death. His successor and acolyte, Roger Smith, has in turn found huge support from a continuing market that demands the finest and most exclusive hand-crafted products. Another arrival in this rarefied atmosphere, Frodshams — a distinguished British clockmaking name of old — expect to produce watches in the coming years that will out-Daniels Daniels.

Thus the determined British private sector appears to have forged a new and successful small corner of a wider market, and the memory of the UK’s brief-dalliance with a state-supported and subsidized watch industry will gradually fade away in the slipstream. Corporate survival requires anticipation, commitment, investment, risk-taking, and many other qualities. Smiths risked and lost much in its involvement in watches (despite success in other industries), and the temptation is to imagine the Swiss watch industry revival merely preserved the natural order. In truth, the degree of sponsorship and backing for that industry in the last sixty years has been colossal.

If the British government’s support for an upstart post-war infant industry failed in short order, owing to overwhelming foreign competition, it will be interesting to see if the Swiss state and its horological industry, after the scare of the 1980s, have this time looked far enough forward, to support any repositioning necessary. Can the luxury ‘single-function device’ continue to thrive? We live in interesting times.

Headline image credit: 1970 by Noodlefish. CC BY-NC 2.0 via flickr.

The post Watching the watch people appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMarital transfers and the welfare of womenWhat’s new in oral history?The Salem Witch Trials [infographic]

Related StoriesMarital transfers and the welfare of womenWhat’s new in oral history?The Salem Witch Trials [infographic]

An inside look at music therapy

We have all experienced the effect music can have on our emotions and state of mind. We have felt our spirit lift when a happy song comes on the radio, or a pinging sense of nostalgia when we hear the songs of our childhood. While this link between music and emotion has long been a part of human life, only in recent decades have we had the technology and foundational knowledge to understand music’s effect on our brains in concrete terms. This knowledge has enabled trained professionals to use music therapy to help people with symptoms of depression, addiction, autism, and more.

I recently worked with a group, called Clarity Way, to put together an informative infographic all about modern music therapy and how it works. The infographic shows everything from how the field is growing–over 70 colleges offer a degree in music therapy–to how it can be applied to patients such as children with speech impediments.

Infographic by Clarity Way.

Infographic by Clarity Way. While the concept of music therapy may be quite old, new techniques and applications are being discovered and developed all the time. We may even start to see more and more hospitals and medical institutions employ full time music therapists as part of their staff in the next few years. It will be interesting to see just how powerful music can be.

Headline image credit: Baby Bloo taking a dip. Photo by Marcus Quigmire. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An inside look at music therapy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating Julie AndrewsGetting to know Anna-Lise Santella, Editor of Grove Music OnlineSalamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance Mantua

Related StoriesCelebrating Julie AndrewsGetting to know Anna-Lise Santella, Editor of Grove Music OnlineSalamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance Mantua

Once upon a time, part 1

I’m writing from Palermo where I’ve been teaching a course on the legacy of Troy. Myths and fairy tales lie on all sides in this old island. It’s a landscape of stories and the past here runs a live wire into the present day. Within the same hour, I saw an amulet from Egypt from nearly 3000 years ago, and passed a young, passionate balladeer giving full voice in the street to a ballad about a young woman – la baronessa Laura di Carini – who was killed by her father in 1538. He and her husband had come upon her alone with a man whom they suspected to be her lover. As she fell under her father’s stabbing, she clung to the wall, and her hand made a bloody print that can still be seen in the castle at Carini – or so I was told. The cantastorie – the ballad singer – was giving the song his all. He was sincere and funny at the same time as he knelt and frowned, mimed and lamented.

The eye of Horus, or Wadjet, was found in a Carthaginian’s grave in the city and it is still painted on the prows of fishing boats, and worn as a charm all over the Mediterranean and the Middle East, in order to ward off dangers. This function is, I believe, one of the deepest reasons for telling stories in general, and fairy tales in particular: the fantasy of hope conjures an antidote to the pain the plots remember. The street singer was young, curly haired, and had spent some time in Liverpool, he told me later, but he was back home now, and his song was raising money for a street theatre called Ditirammu (dialect for Dithryamb), that performs on a tiny stage in the stables of an ]old palazzo in the district called the Kalsa. Using a mixture of puppetry, song, dance, and mime, the troupe give local saints’ legends, traditional tales of crusader paladins versus dastardly Moors, and pastiches of Pinocchio, Snow White, and Alice in Wonderland.

A balladeer in Palermo. Photograph taken by Marina Warner. Do not use without permission.

A balladeer in Palermo. Photograph taken by Marina Warner. Do not use without permission.Their work captures the way fairy tales spread through different media and can be played, danced or painted and still remain recognisable: there are individual stories which keep shape-shifting across time, and there is also a fairytale quality which suffuses different forms of expression (even recent fashion designs have drawn on fairytale imagery and motifs). The Palermo theatre’s repertoire also reveals the kinship between some history and fairy tale: the hard facts enclosed and memorialised in the stories. Although the happy ending is a distinguishing feature of fairy tales, many of them remember the way things were – Bluebeard testifies to the kinds of marriages that killed Laura di Carini.

A few days after coming across the cantastorie in the street, I was taken to see the country villa on the crest of Capo d’Orlando overlooking the sea, where Casimiro Piccolo lived with his brother and sister. The Piccolo siblings were rich Sicilian landowners, peculiar survivals of a mixture of luxurious feudalism and austere monasticism. A dilettante and dabbler in the occult, Casimiro believed in fairies. He went out to see them at twilight, the hour recommended by experts such as William Blake, who reported he had seen a fairy funeral, and the Revd. Robert Kirk, who had the information on good authority from his parishioners in the Highlands, where fairy abductions, second sight, and changelings were a regular occurrence in the seventeenth century.

The Eye of Horus, By Marie-Lan Nguyen, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Eye of Horus, By Marie-Lan Nguyen, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Casimiro’s elder brother, Lucio, a poet who had a brief flash of fame in the Fifties, was as solitary, odd-looking, and idiosyncratic as himself, and the siblings lived alone with their twenty servants, in the midst of a park with rare shrubs and cacti from all over the world, their beautiful summer villa filled with a vast library of science, art, and literature, and marvellous things. They slept in beds as narrow as a discalced Carmelite’s, and never married. They loved their dogs, and gave them names that are mostly monosyllables, often sort of orientalised in a troubling way. They range from ‘Aladdin’ to ‘Mameluk’ to ‘Book’ and the brothers built them a cemetery of their own in the garden.

Casimiro was a follower of Paracelsus, who had distinguished the elemental beings as animating matter: gnomes, undines, sylphs and salamanders. Salamanders, in the form of darting, wriggling lizards, are plentiful on the baked stones of the south, but the others are the cousins of imps and elves, sprites and sirens, and they’re not so common. The journal Psychic News, to which Casimiro subscribed, inspired him to try to take photographs of the apparitions he saw in the park of exotic plants around the house. He also ordered various publications of the Society of Psychical Research and other bodies who tried to tap immaterial presences and energies. He was hoping for images like the famous Cottingley images of fairies sunbathing or dancing which Conan Doyle so admired. But he had no success. Instead, he painted: a fairy punt poled by a hobgoblin through the lily pads, a fairy doctor with a bag full of shining golden instruments taking the pulse of a turkey, four old gnomes consulting a huge grimoire held up by imps, etiolated genies, turbaned potentates, and eastern sages. He rarely left Sicily, or indeed, his family home, and he went on painting his sightings in soft, rich watercolour from 1943 to 1970 when he died.

Photograph by Marina Warner. Do not use without permission.

Photograph by Marina Warner. Do not use without permission.His work looks like Victorian or Edwardian fairy paintings. Had this reclusive Sicilian seen the crazed visions of Richard Dadd, or illustrations by Arthur Rackham or John Anster Fitzgerald? Or even Disney? Disney was looking very carefully at picture books when he formed the famous characters and stamped them with his own jokiness. Casimiro doesn’t seem to be in earnest, and the long-nosed dwarfs look a little bit like self-mockery. It is impossible to know what he meant, if he meant what he said, or what he believed. But the fact remains, for a grown man to believe in fairies strikes us now as pretty silly.

The Piccolo family’s cousin, close friend and regular visitor was Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, the author of The Leopard, and he wrote a mysterious and memorable short story about a classics professor who once spent a passionate summer with a mermaid. But tales of fairies, goblins, and gnomes seem to belong to an altogether different degree of absurdity from a classics professor meeting a siren.

And yet, the Piccolo brothers communicated with Yeats, who held all kinds of beliefs. He smelted his wonderful poems from a chaotic rubble of fairy lore, psychic theories, dream interpretation, divinatory methods, and Christian symbolism: “Out of the quarrel with others we make rhetoric; out of the quarrel with ourselves we make poetry.”

Featured image credit: Capo d’Orlando, by Chtamina. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Once upon a time, part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow much are nurses worth?A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3In defence of horror

Related StoriesHow much are nurses worth?A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3In defence of horror

October 22, 2014

Has open access failed?

At the Conference on Open Access Scholarly Publishing in Paris last month, Claudio Aspesi, Senior Analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein, raised an uncomfortable question. Did the continuing financial health of traditional publishers like Elsevier indicate that open access had “failed”? According to Aspesi, “Expectations that OA will address the serial costs crisis are fading away.”

Is Aspesi right? Has open access failed? I certainly don’t think so – but that doesn’t mean the job is done…

Defining success

When we launched BioMed Central in 2000, the goal was a simple and positive one – it wasn’t to fix library budgets or to destroy the businesses of existing publishers, but to introduce a new form of publishing that would help researchers communicate their findings more effectively by challenging the established notion that published results “belonged” to the publisher.

The success of the open access movement is demonstrated most clearly by the extent to which it is simply no longer acceptable to the world’s largest science funders for the results of their funding to end up trapped indefinitely behind publisher paywalls.

For example, the pilot for open access to research outputs in the EU’s 7th Framework program (FP7) has become, with Horizon 2020 (the successor to FP7), a mandatory policy covering all funded research. If this is failure, it is a strange-looking form of failure, with the results of the full €80 billion of H2020 funding now set to be made publicly available. This is in addition to similar mandatory public access policies already in force or announced for the major UK research funders, all US government funded research, two of the largest funders in China, and many others.

Of course, existing publishers have found ways to adapt to funders’ expectations of open access, and even to grow their businesses thanks to the additional funding made available to cover “Gold” open access fees. This isn’t such a bad thing; traditional publishers are responsible for many good journals. As more of them convert to a fully open access model (Nature Communications being one recent example), we are seeing a ratchet mechanism at work which is progressively shifting an ever higher fraction of the scientific literature to being open access immediately on publication and in authoritative final form.

While some bemoan the fees associated with “Gold” open access publishing, the model has the powerful advantage of providing a funding mechanism which scales with the increasing volume of research funding, unlike library budgets. By making the costs of publishing visible to authors, it also has the potential to eventually save costs by creating a more efficient market for publishing services (though this does depend on authors showing at least some degree of price sensitivity).

As for the perceived failure of open access to knock the incumbents from their perch, this seems a curious metric of success. We don’t regard AirBnB as a failure because hotel chains still exist, and nor is the continued existence of national airline carriers seen as a fundamental failure of the budget airline model. In both cases, the landscape has been profoundly transformed by the new model, and existing players are having to adapt, improve, and refocus their offering to compete.

Perhaps the most important success of the open access movement is not what it has already achieved, but the foundation it provides for further improvements to scientific communication.

Data concept: Opened Padlock on digital background. © maxkabakov via iStock.

Data concept: Opened Padlock on digital background. © maxkabakov via iStock.Open access to open data

Establishment of open access to research articles as a basic norm has paved the way for the EU pilot of Open Research Data within H2020, seeking to ensure that not only the published article but the underlying data resulting from scientific research should be routinely made available in a form that facilitates reuse and further analysis.

The need for improved access to research data is not a new idea. Funders such as the Wellcome Trust and NSF already require grantees to specify Data Management Plans to indicate how the results of funded research will be made accessible. Unfortunately these plans often aren’t worth the (virtual) paper they are printed on. With suitable data standards and data management infrastructure either absent or not widely used, obtaining a copy of the underlying data from a particular research project can still be tortuous or even impossible.

Even if the data can be obtained, often the metadata and experimental details available are insufficient to make the experimental results reliably reproducible. With luck, the lab member who carried out the experiment may still be around and may be able (with considerable effort) to dig out such information, but the longer that has elapsed since publication, the more likely it is that the exact details of what was done will have vanished forever.

To address this problem, it is not enough to change the way science is published, we also need to look upstream at how scientific experiments are carried out, and how the results are analysed and prepared for publication.

Improving the scientific method

In computational research, significant steps have been made towards improving the situation. The Galaxy platform allows researchers to share genomic analysis pipelines in a form which can be readily reused by other researchers, and the journal GigaScience (published by BioMed Central in collaboration with the BGI) has embraced this approach by making available a public Galaxy server to ensure that data and analyses associated with the articles it publishes are readily accessible. More generally, there is strong enthusiasm amongst computational researchers for the use of new tools such as Docker to allow arbitrary ‘experimental setups’ for in silico research to be shared efficiently.

At the lab bench, sharing full experimental details and data descriptions is more challenging due to the wide range of data types and experimental descriptions which need to be represented. The NIH’s Big Data 2 Knowledge (BD2K) initiative, which recently announced its first round of funding awards, shows that this challenge is now receiving serious attention, and the use by journals such as Scientific Data and GigaScience of (Investigation, Study, Assay Tabular format) as a general high-level metadata standard shows promise, though there is some way to go before we have tools in place to make preparing data for publication in such a formats a pleasure rather than a chore.

At Riffyn, we are working with academic and industrial partners to develop cloud-based tools which will help researchers design their experiments up front using a friendly modern user interface, and to capture data from those experiments in a way which retains a connection to the experimental design and context, with the goal of making results more reliable and reproducible, and helping to rapidly distinguish genuine insights in the data from artefacts and noise. The long term goal is to ensure that making data well-described and reusable isn’t an afterthought or a tedious additional step, but is at the heart of the experimental process.

Any attempt to improve the way science is done will only succeed through collective effort and widespread adoption of shared standards. We hope to see a whole ecosystem of tools and standards emerge which will support the smooth flow of data and accompanying descriptive metadata all the way from experimental design, through data capture, to analysis, visualization, authoring and publication, retaining as much as possible of the provenance information and structure at every stage.

The future

This will not be easy, but the building blocks do seem to be falling into place. The Force11 conference (spawned from earlier Beyond the PDF workshops), which next takes place in Oxford in January 2015, has created a useful framework for such collaboration. This weekend (25-26 October 2014) at the Mozilla Festival in London, the science track will offer a data-driven authoring workshop. Tools providers including Authorea, WriteLaTeX, Papers, Pensoft and F1000 will run demos and tutorials, whilst discussing how best such tools can be made to work together and integrate smoothly with lab data systems and publisher platforms, so that ultimately data can flow freely and in meaningful form through the entire process. If you can, please join us there to work with us on the next chapter of the open access success story.

The opinions and other information contained in this blog post and comments do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Oxford University Press.

The post Has open access failed? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQuestions surrounding open access licensingFive key moments in the Open Access movement in the last ten yearsHow much are nurses worth?

Related StoriesQuestions surrounding open access licensingFive key moments in the Open Access movement in the last ten yearsHow much are nurses worth?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers