Oxford University Press's Blog, page 748

October 22, 2014

How much are nurses worth?

If you ask many people about nurses, they will tell you how caring and kind nurses are. The word “angel” might even appear. Nursing consistently tops the annual Gallup poll comparing the ethics and honesty of different professions.

But it’s worth exploring the extent to which society really values nursing. In recent decades, a global nursing shortage has often meant too few nurses to fill open positions, woefully inadequate nurse staffing levels, and not enough funds for nursing education. Many nurses have migrated across the globe, easing shortages in developed nations but exacerbating them in the developed world, where health systems are already under great stress. In a world where funds for health care are limited, nursing does not seem to be getting the love we profess to have for it.

This all starts with how decision-makers and members of the public view nursing. In reality, nurses are autonomous, college-educated science professionals who save lives and improve patient outcomes, in settings that range from war zones to high-tech ICUs. But nursing remains subject to a set of toxic gender-related stereotypes, which the mass media both reflects and reinforces, undermining the profession’s claims to scarce resources. Research in the field of health communication confirms that what the public sees on television and in films has a significant effect on health-related views and actions.

Consider some recent examples. The recent Ebola outbreak has attracted great interest from the global news media. There have been stories about the work of nurses to fight the disease, such as a strong piece in the Guardian earlier this month in which nurses described in great detail what they were doing to care for patients in West Africa. Some reports about the recent infections of the nurses in Dallas have highlighted allegations by nurses at Texas Health Presbyterian about infection control failures, and a few of the pieces have even consulted nurse experts.

A British nurse writing her notes. Photo by Louise (goodcatmum). CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

A British nurse writing her notes. Photo by Louise (goodcatmum). CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.But most Ebola pieces consult only physicians for expert comment, and many suggest that physicians are the only health workers who really matter, with nurses as their faithful assistants. One long article from August 2014 in the New York Times described the shortage of local and international physicians in Liberia and suggested that this shortage was the main health staffing problem. In fact, nurses provide far more hands-on care to patients suffering from debilitating infectious diseases, and so they tend to face greater associated burdens and risks, as the first infections in the United States have now made clear. Indeed, it’s likely that those first cases were nurses because nurses provide most skilled in-patient care, not because they are unusually poor at infection control. Yet even many reports that have mentioned nurses and other health workers have used “doctors” as shorthand for everyone, reinforcing the message that even if physicians aren’t the only ones involved, they are the only ones who count.

Much Ebola coverage has involved the prominent aid group Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), whose name has long suggested that it’s an organization comprised solely of physicians. In reality, nurses outnumber physicians among MSF health professionals. But each time MSF’s name is mentioned, physicians receive all the credit for its work.

Hollywood’s vision of nursing remains largely caught in a time warp of unskilled handmaidens, pathetic losers, and prickly battleaxes, despite the gifted (if flawed) Nurse Jackie and a few other good portrayals. ABC’s Grey’s Anatomy has spent a decade telling the world that nursing consists of chirping “Right away, doctor!” and handing things to the brilliant, pretty surgeons who provide all meaningful health care. Fox’s The Mindy Project is mostly about the romantic interactions of quirky New York City OB-GYN physicians, but it also includes three stooges, uh, nurses, who make lots of ludicrous remarks yet seem to know almost nothing about health care. Fox’s new Red Band Society features a senior nurse (a.k.a. “Scary Bitch”) who is often portrayed as a battle-axe. But the nurse shows little expertise. She once asked a physician colleague about a recent operation, in which he had chosen not to amputate a cancer patient’s leg, this way: “So, getting to keep his leg was a bad thing…?”

The naughty nurse remains an advertising staple worldwide. In one current US television ad, a young woman suggests that colleagues should eat food from the sandwich chain Subway so they’ll be able to fit into skimpy Halloween outfits. She proceeds to demonstrate with a very skimpy hot nurse costume, among others. Another recent ad campaign presents the new Klondike Kandy Bar as the love child of what Adweek accurately describes as “an illicit tryst between a [male] Klondike bar and a tall, striking, chocolaty [female] candy-bar nurse,” who seems to have seduced her surprised ice cream patient. Yes, those images are “just jokes.” But research shows that jokes have great influence over attitudes, and of course jokes remain a primary vehicle for delivering prejudice.

Nurses must take the lead in improving understanding of their profession, but we can all do something. We urge people to pay close attention when interacting with nurses and to ask if what they observe bears any relation to what they often see in the media. Was it just a “caring angel,” or did the nurse also save a life by educating a patient or detecting a subtle change in condition? Even the language we use matters. For instance, hospitals are not so much “medical centers” as they are “nursing centers,” since patients wouldn’t stay there unless they needed 24/7 nursing care. And calling physicians “doctors” wrongly implies that they are the only health professionals who earn doctorates. Yet nurses and others get doctorates as well. We hope the public can see past traditional assumptions about nursing—because they threaten our lives.

The post How much are nurses worth? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat will it take to reduce infections in the hospital?A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3What we’ve learned and what we missed

Related StoriesWhat will it take to reduce infections in the hospital?A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3What we’ve learned and what we missed

A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3

If you have read the previous parts of this “study,” you may remember that brown is defined as a color between orange and black, but lexicographical sources often abstain from definitions and refer to the color of familiar objects. They say that brown is the color of mud, dirt, coffee, chocolate, hazel, or chestnut. Sometimes compounds like golden-brown turn up. Despite such differences, most people associate brown with a dark hue. The standard Latin gloss of Engl. brown is fuscus “dark” (compare the verb obfuscate). In using descriptive adjectives for “brown,” language follows the ancient trend (green is the color of vegetation, red is the color of ore, and so forth). Modern Greek has lost the ancient names of this color and uses a word having the root of the noun chestnut, while Russian speakers refer to cinnamon, an unexpectedly exotic product (koritsa—korichnevyi). The more “genuine” Russian word for “brown” (byryi, stress on the first syllable) is probably a borrowing: it seems to have been taken over along with brown horses. Romance speakers went the same way, but their lender was Germanic.

If we consider that brown is an intermediate color, we may perhaps understand the uses of the epithets mentioned last week. Dante’s “brown [that is, clotted] blood” is about the blood that lost its glow and no longer looked red. Red is likewise a broad term: we call crimson and scarlet objects red, but Tyrian purple and especially Tuscan red are almost black. Russian words beginning with ryab- are applied to speckled creatures and objects. Quite properly, the hazel-grouse is called ryabchik (-chik is a diminutive suffix), but the Russian for “rowan tree” (“mountain ash”) is ryabina (stress on the second syllable), though the bright berries of the mountain ash look shining red, especially in winter.

The standard epithet Homer applied to the sea was wine-colored, and today it causes surprise. However, there is probably no riddle. The colors of the wines the Ancient Greeks produced varied from inky black to nearly clear. Since waves reflect the color of the sky, we find their surface blue or black. A look at the pictures by realistic painters shows that under the surface tossing waves often appeared green to them. The question is not whether sea waves can be wine-colored, because, considering how many brands of wine there are, they certainly can, but why Homer associated them with wine rather than with some other dark liquid. Can we conclude that in his time dark wines were especially popular? The brown waves of Old English poetry mean simply “dark waves.” If we are puzzled, it happens because, as pointed out, today the color brown evokes the image of chestnuts, hazel, and chocolate rather than sea water. In a modern poem, chestnut-colored, chocolate-colored, or wine-colored waves would sound either incongruous or pretentious. Yet only usage, not color perception, has changed since the days of the Odyssey and Beowulf. The idea that “primitive cultures” had an indistinct idea of colors should be ruled out by definition. In similar fashion, we wear neither chiton nor toga, but at one time people wore both and would have reacted to our expensive torn jeans with amazement and justifiable horror.

We are in more trouble with brown meaning “violet” (see Part 2 of the present essay). Recent etymological dictionaries trace this sense of brown (or rather brun ~ braun, because only German is involved) to Latin prunum “plum.” If we were dealing with poetic diction, we could accept the idea of Latin influence, but the word has wide currency in dialects, and one wonders to what extent Latin was instrumental in the emergence of brown “violet.” I would again like to cite a parallel from Slavic. The Russian for plum is sliva, a cognate of Latin lividus “livid” (some of our readers may remember what I once wrote about movable s, or s-mobile). It is instructive to follow the transformation of this color name. Although dictionaries differ when it comes to details, all of them say approximately the same about livid. I found the glosses “ashen or pallid,” “bluish gray,” “purplish,” “dull blue,” “grayish blue,” and “black-and-blue.” They agree that the color of a bruise is livid and that livid, when used in everyday speech, is understood as “furiously angry.” But many people think that livid means “red,” and it is easy to understand them, because red is the color of the face flushed with anger.

Portraits of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning by Thomas Buchanan Read, 1853 (Christie’s). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portraits of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning by Thomas Buchanan Read, 1853 (Christie’s). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Another instructive case is lurid (from Latin luridus “wan or yellowish”). In English, the word surfaced only in the eighteenth century but since that time has changed from “sallow, sickly pale” to “shining with a red glare; yellow-brown.” Shelley begins his narrative poem Queen Mab so:

“How wonderful is Death,

Death and his brother Sleep!

One, pale as yonder waning moon

With lips of lurid blue;

The other rosy as the morn….”

In Shelley’s language, lurid meant, as it did in Latin, “deadly pale,” but don’t miss “yellow-brown” and especially “shining with a red glare” above. Note also how the contextual use of livid (“angry”) affected its main sense. I have no explanation for German dialectal braun “violet,” but, before we jump to conclusions and refer to borrowing and homonymy, it may be useful to remember how unpredictable the interplay of color names sometimes is.

It remains for me to say something about brown study. To be in a brown study means “to be in intense reverie.” Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot is often described in this state of mind. Why brown? Some people thought of “corruption” and traced brown in this idiom to barren or to some German word. The OED dismissed the reference to German as untenable and suggested that brown here means “gloomy” (first published 1888). As far as I can judge, this little problem of English phraseology has attracted little or no attention, so that it might be useful to quote an anonymous reviewer (The Nation 48, 1889, p. 288).

The journal review of the OED’s first volume (A and B) is laudatory, but its author wrote:

“In only one instance, so far as we have observed, have they [the editors] laid themselves open to criticism…; and the variation from their usual practice is noteworthy enough to merit special comment. It occurs in the case of the somewhat peculiar expression brown study. The adjective here has assuredly the general idea of ‘deep,’ profound,’ ‘abstracted.’ It is hard to fix upon the phrase the sense of ‘gloomy meditation’, by which Johnson defined it; and the particular meaning given to it in this dictionary of ‘an idle and purposeless reverie’ is certainly not common. But it is in the explanation of its origin that conjecture appears here for once to have triumphed over judgment. The meaning is declared to have apparently come in the first place from brown in the sense of ‘gloomy,’ but that this sense of the adjective has to a great extent been forgotten. When, however, we turn to the adjective itself, we find that so far from such a sense having been forgotten, there is not the slightest record that it ever existed…. …the origin of the meaning of brown study remains in the dark as ever. It may be added that stiff seems formerly to have been an equivalent expression. In the romance of William of Palerne one of the characters is represented as having fallen ‘into a styf studie’….”

Who could have written this well-informed review? Richard Bailey (in Mugglestone, 2000) identified the author as Thomas R. Lounsbury, though it was indeed originally printed as anonymous, like all reviews in The Nation.

So it goes: brown “red,” brown “violet,” brown blood (as opposed to blue blood!), brown waves, brown nights, in a brown study, brownie, Father Brown, and Good Mrs. Brown.

Headline image credit: Mountain Ash (Rowan Tree) in the winter. Photo by Hella Delicious. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 2

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 2

What we’ve learned and what we missed

A ten-year anniversary seems an opportune time to take stock. Much has been said already about Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) as it moves into its second decade, and let’s cast the net a bit wider and focus not on OSO, per se, but on what the academic publishing industry has gotten right and what we’ve missed since OSO was in its infancy.

The biggest change, of which OSO has been a central component at Oxford University Press, has of course been the transition from a print-centric, manufacturing-based industry to a print-and-online, service-oriented industry.

Drawing on that general context, below then are two lists: (1) what publishers have learned in this age of online publishing, and (2) what we took too long to learn or didn’t see coming.

10 things we’ve learned

1. The Long Tail. While the long tail is a familiar concept in statistical circles, it became a cultural conceit owing to Chris Anderson’s influential 2004 article in Wired magazine, which subsequently became a bestselling book. The lesson publishers took from this article/book was that, rather than endlessly pursuing new and different audiences and markets, you need to make sure you’re doing a good job of providing your goods — no matter how old — to the people — no matter how few in number — who have already demonstrated a desire for it. Too many publishers were terrible at keeping their books in stock, owing to the constraints imposed by the economies of scale associated with traditional offset printing. The ability to print books digitally and in very small batches or even one at a time in response to demand had a revolutionary effect on academic publishing, the very definition of a long-tail industry.

2. The E-book Revolution. E-books have taught us a great deal about consumer behavior, specifically what prompts people to make the decision to buy. E-books have proven to be an effective way to draw readers to overlooked books or to reinvigorate proven backlist titles. And, to the surprise of many, the massive glut of self-published work has had relatively little impact on the high-quality vetted non-fiction published by university presses.

3. Discoverability. Invest in the digital infrastructure necessary to draw attention to your offerings. Period.

E-book between paper books by Maximilian Schönherr. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

E-book between paper books by Maximilian Schönherr. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.4. Get the Basics Right. Populated by people who are better with metaphors than spreadsheets, publishing has historically been an inefficient industry, with more attention devoted to ideas than to execution. The valuable skills of demand planners, of project managers, of efficiency experts can, when properly incorporated into a publishing environment, greatly enhance the ability of a press to fulfill its mission.

5. Mistrust the Theologians. Whether it’s open access evangelists, Wikipedia detractors, print-will-never-die bibliophiles, print-is-dead technophiles, there’s generally little other than provocative headlines in absolutist prognostications about the future. The truth almost always lies in the messy, complicated middle. We are powerfully drawn to binaries and oppositional dichotomies but that’s rarely the way things play out.

6. Authors still want to be edited and advised. That’s really all there is to say. Even as many things about publishing have changed, the intellectual bond between author and editor — and often publicist or marketer — is paramount. Furthermore, in a world where the lingua franca of the academy and of business is now irrefutably English, and where one in three people is either Indian or Chinese, there are a lot of researchers and scholars who could use our editing and translational skills.

7. We’re a hardier industry than we give ourselves credit for. What seemed very scary just a few short years ago seems a bit less scary now. We’ve weathered the decline of independent stores, the rise of the chains, the demise of Borders, the rise of Amazon and Apple, the arrival of e-readers, and the unexpected flattening of e-book sales once the initial “load-up-your-e-reader” euphoria had subsided. The ubiquity of the web, and the transition from an information-scarcity economy to an information-glutted world in under 20 years, has highlighted the need for filters, which is, after all, a defining characteristic of publishers.

8. University presses are hard to run, but they’re even harder to kill. “Hard to kill” isn’t a business model but it does speak to the value that our regional communities place on the work we do. Numerous attempts to shutter or trim university presses have been met with howls of protest, often resulting in a reversal or tempering of the original decision.

9. The difference between extractive research and immersive reading. The web has highlighted the different ways in which people use books. Most bluntly, people read fiction but consume much non-fiction in an extractive, “dip-in-and-dip-out” manner. We may have presumed as much ten years ago but we can now trace the “user journey” of researchers and readers forensically via usage reporting.

10. The value of the physical book. A great many articles and books have appeared in the last decade extolling the virtues and utility and durability of the printed book. The emotional intensity of these affirmations of the physical book has surprised even some publishers. And, as we now know in a way we only presumed a decade ago, the physical book has an appeal that can happily run side-by-side with its digital and online cousins.

5 things we took too long to learn or didn’t see coming

1. POD and digital printing changed the world while we were nattering on about e-books, long before the market for them matured. See #1 above. We prognosticate endlessly about the future because we don’t want to seem anachronistic or Luddite (a historian recently said to me that she thought a great deal of innovation in business was driven by middle-aged people not wanting to appear old), but too often we focus too much on what will happen, rather than when it will happen, which is frequently the real question.

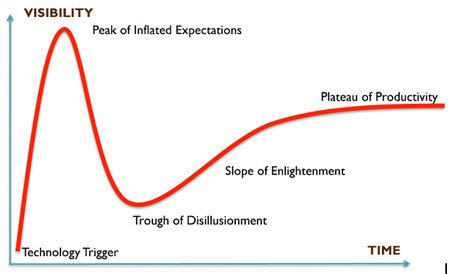

Trough of Disillusionment

Trough of Disillusionment2. Things tend to happen more slowly than we think, and then they happen suddenly and fast. Exhibit A: E-book sales. Exhibit B: Social media relevance. If there is one tendency with which publishers have become very familiar since the onset of online publishing, it’s the phenomenon known in business-speak as Gartner’s Hype Cycle, depicted in the graph. In a sentence, new technologies are often met with wildly inflated expectations in the early days, resulting in inevitable disappointment, and then gradually gain a foothold and become established. Others, of course, never emerge from the “Trough of Disillusionment.”

Examples of technology-driven phenomena that have spent some time on the hype cycle, or remain there, are:

Print on Demand book manufacturing (which took years to become viable, both from a cost and a quality standpoint)

E-books (in the early days)

Apps (especially apps that aren’t free)

Websites for individual books (not useful now, if they ever were)

Book trailers for all but a very few books

Augmented e-book rights (about which there was a great fuss a few years ago)

Sales of individual book chapters

College textbook e-readers

And, perhaps most conspicuously, MOOCs

3. Back-office technology. Many publishers have underestimated the back-office technology challenges presented by the fragmenting media and sales landscape: the changing revenue streams, the multi-format sales models, the double running costs.

4. The potential perils of “secular stagnation”. The early years of digital publishing were typified by “retroconversion” efforts, in other words the digitizing of legacy backlist. Is there a risk that the one-time bumps granted publishers from the maturation of e-books, of POD efficiencies, of sales from journals back issues has concealed a slowdown or even a hollowing out of core markets? This is an unanswerable question when posed broadly but it’s a question all publishers should be asking themselves as they weigh their futures.

5. Access, access, access. Discussions about online publishing often focus on all the new and different things authors, educators, and publishers can do in an online environment. What has been relatively overlooked is the great promise of online publishing when it comes to access. Online delivery has the potential — already being realized in a number of ways — to enable authors and publishers to reach more people more efficiently and quickly, and at a lower cost, than ever before.

The post What we’ve learned and what we missed appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQuestions surrounding open access licensingChanges in digital publishing: a marketer’s perspectivePlace of the Year 2014: behind the longlist

Related StoriesQuestions surrounding open access licensingChanges in digital publishing: a marketer’s perspectivePlace of the Year 2014: behind the longlist

Marital transfers and the welfare of women

Throughout history and across cultures, marriage has often been accompanied by substantial exchange of wealth. However, the practice has mostly died out in western societies, which is perhaps why the meanings of these marital transfers are often not well understood. In anthropological terms, a dowry can be seen as a form of pre-mortem bequest to the bride from her parents, while bride-price or groom-price is a transaction between the kin of the groom and the kin of the bride. The former is an intergenerational transfer within the bride’s family, even though the groom and his family can also benefit when it is used to help set up the conjugal household, while the latter is a transfer between affinal families.

These conceptually distinct transfers are supposed to serve different functions. Recent economic research suggests that the bride-price or groom-price is a means of distributing gains generated by the marriage in accordance with overall social/cultural/economic conditions as well as personal attributes of the bride and the groom. Dowry, on the other hand, can be interpreted as a gift from altruistic parents to the bride to help establish her position in the new household. This is important since virilocality, whereby the bride leaves her natal family to join her husband’s household, is the norm in most traditional cultures. Empirical studies, using data from medieval Tuscany to modern-day China and Taiwan, appear to support these interpretations, particularly with regard to the beneficial effect of dowry on the welfare of women.

The picture is, however, quite different in South Asia, where dowry has taken on extravagant proportions in recent years and is often considered a social evil, morally offensive, and legally banned. Stories abound of Indian women abused or even murdered by their husbands or in-laws when the latter’s demands for dowries are not met. There is no shortage of commentaries on this issue, but relatively few rigorous empirical studies in this region. Nevertheless, the South Asian experience does raise a valid question: is dowry really good for the bride?

Indian Wedding Celebration, by Cleiph. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Indian Wedding Celebration, by Cleiph. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.The answer to this question depends partly on what is meant by dowry, and in India today, it is synonymous with groom-price rather than a bequest to the bride. However, there is some evidence that, even in India, a “dowry” can include both components. Since these transfers are supposed to serve different purposes, we must first decompose “dowry” into these components before we can ascertain their effects on the welfare of women. This is what I did in a recent study using an Indian data set. By taking into account the control that various individuals (the wife, the husband, or other family members) exercise over the use of different types of marital transfers (land, cash, jewelry, etc.) as reported by the wife, I estimate the amounts of the bequest and the groom-price in a dowry, and find that a larger bequest does allow Indian women a greater say in a broad range of household decisions, from whom to invite to dinner, to children-rearing decisions, to making small independent purchases.

There can be alternative interpretations of this result. It is possible that a resourceful wife can secure a larger bequest from her parents as well as more decision power in her conjugal family, causing a spurious causal relationship between the two. However, even after I have controlled for this “endogeneity problem” using econometric methods, the positive effects of the bequest component of a dowry remain. Yet another possibility is that, in a patriarchal society such as India, any marital transfer will inevitably be appropriated by the husband and his family, regardless of the original intent of the bride’s parents. But since the Indian researchers who collected the data are confident that the women’s responses on the amount and control over marital transfers in my sample are reliable, we would have to take the data at face value, at least until better data become available.

This finding leads to the sensitive question of whether dowry should be banned in the first place: if a dowry enhances the status of the wife, wouldn’t banning it deprive parents a channel through which they can help their daughter? One can perhaps reject dowry simply because it is demeaning to women if marriage has to be consecrated by marital payments, although this objection lies more with the groom-price component of a “dowry” rather than the bequest component. Even if the ban were to apply only to groom-price, it would be a case of trying to fix the symptom without getting to the root of the problem. If parents voluntarily enter into a marriage agreement for their daughter even though it involves an exorbitant amount of groom-price, it must be because they believe the high price would secure a “good” marriage for their daughter. They would stop paying high groom-prices if they could be convinced that higher caste status is not worth the extra cash, or that a young man with a civil service career does not necessarily promise a better life for their daughter.

Alternatively, the government can ban dowry and impose heavy penalties on offenders. Neither seemed to have worked in India so far, as dowry remains prevalent, almost fifty years after the first dowry prohibition act was passed. What has changed is that marital transfers cannot be contracted upon because they are illegal. Enforcement of prior agreement depends on the good faith and concern for the reputation of the parties involved. When this mechanism fails, there is no legal recourse for the aggrieved party. The bride and her family are particularly vulnerable because she can literally be held hostage in ex post bargaining. If dowry is decriminalized and marital transfers can be negotiated, contracted, and accorded legal status, then not only can women enjoy the benefits of their dowry and better protection for their property rights, but opportunistic behavior by the grooms and their families to extract further concessions can also be discouraged. What looks like a step backward in history may bring positive dividends for women in the region.

The post Marital transfers and the welfare of women appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCorporate short-termism, the media, and the self-fulfilling prophecyPolitical economy in AfricaEarly blues and country music

Related StoriesCorporate short-termism, the media, and the self-fulfilling prophecyPolitical economy in AfricaEarly blues and country music

In defence of horror

A human eyeball shoots out of its socket, and rolls into a gutter. A child returns from the dead and tears the beating heart from his tormentor’s chest. A young man has horrifying visions of his mother’s decomposing corpse. A baby is ripped from its living mother’s womb. A mother tears her son to pieces, and parades around with his head on a stick… These are scenes from the notorious, banned ‘video nasty’ films Eaten Alive, Zombie Flesh Eaters, I Spit on Your Grave, Anthropophagous: The Beast, and Cannibal Holocaust.

Well, no. They could be – but they’re not. All these scenes and images can be found safely inside the respectable covers of Oxford World’s Classics, in the works of Edgar Allan Poe, M.R. James, James Joyce, William Shakespeare, and Euripides. Only the first two of these are avowedly writers of horror, and none of these books comes with any kind of public health warning or age-suitability guideline. What does this mean?

Euripides’s The Bacchae, first performed around 400 BC, is one of the foundational works of the Western literary canon. In describing graphically the actions of Agave and her Maenads, dismembering King Pentheus and putting his head on a pole, it also sets the bar very high for artistic representations of violence and gore. The episode of the baby ripped from the mother’s womb to which I alluded in the first paragraph is from Macbeth, of course – it’s Macduff’s account of his own birth. And Macbeth, though certainly no slouch in the mayhem department, isn’t even Shakespeare’s most violent play. That would be Titus Andronicus, whose opening scene makes the connections between civilization and horror very clear, as Tamora, Queen of the Goths, sees her son brutally killed by the conquering Romans:

See, lord and father, how we have performed

Our Roman rites: Alarbus’ limbs are lopp’d,

And entrails feed the sacrificing fire,

Whose smoke, like incense, doth perfume the sky.

What follows is well known: further mutilation, rape, cannibalism. Shocking, yes; surprising, no. After all, the greater part of the Western literary tradition follows, or celebrates, a faith whose own sacrificial rites have at their heart symbolic representations of torture and cannibalism, the cross and the host. A case could plausibly be made that the Western literary tradition is a tradition of horror. This may be an overstatement, but it’s an argument with which any honest thinker has to engage.

![M. R. James [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1413970848i/11588409.jpg) M. R. James, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

M. R. James, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons The classic argument adduced in defence of the brutality of tragedy (a form which I have come to think of as highbrow horror) is the Aristotelian concept of catharsis, according to which the act of witnessing artistic representations of cruelty and monstrosity, pity and fear, purges the audience of these emotions, leaving them psychologically healthier. Horror is good for you! I confess I have always had difficulty accepting this hypothesis (though I recognize that many people far more learned and brilliant than me have had no trouble accepting it). It seems to me to be a classic example of an intellectual’s gambit, a theory offered without recourse to any evidence. And yet catharsis seems to me to be far preferable to another, more common, response to horror: the urge to censor or ban extreme documents and images in the name of public morality. If catharsis is Aristotelian, then this hypothesis is Pavlovian: horror conditions our responses; a tendency to watch violent acts leads inexorably to a tendency to commit violent acts. For many people, this seems to make intuitive sense (on more than one occasion, I’ve noticed people backing away from me when I tell them I work on horror), and it’s the impetus behind the framing of the Video Recordings Act of 1984, after which Cannibal Holocaust and all those other video nasties were banned. As a number of commentators and critics have noted, there’s no evidence for this Pavlovian hypothesis, either. Worse than that, there’s a distinct class animus behind such thinking. You and I, cultured, literate, educated, middle class folks that we are, are perfectly safe: when we watch Cannibal Holocaust (which I do, even if you don’t) we know what we are seeing, we can contextualize the film, interpret it, recognize it for what it is. The problem, the argument implicitly goes, is not us, it is them, those festering, semi-bestial proletarians whose extant propensity for violence (always simmering beneath the surface) can only be stoked by watching these films. That’s why no-one seriously considers banning The Bacchae or Titus Andronicus – why any suggestion that we do so would be treated as an act of appalling philistinism. They are horror for the educated classes.

Horror is, unquestionably, an extreme art form. Like all avant-garde art, I would suggest, its real purpose is to force its audiences to confront the limits of their own tolerance – including, emphatically, their own tolerance for what is or is not art. Commonly, when hitting these limits, we respond with fear, frustration, and even rage. Even today, this is not an unusual reaction on first reading Finnegans Wake, for example: I see it occasionally in my students, who are (a) voluntarily students of literature, and (b) usually Irish, not to say actual Dubliners. So we shouldn’t be surprised that audiences respond to horror with – well, with horror. But we need to recognize that the reasons for doing this are complex, and are deeply bound up with the meaning and function of art, and of civilization.

Headline image: Pentheus torn apart by Agave and Ino. Attic red-figure lekanis (cosmetics bowl) lid, ca. 450-425 BC, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The post In defence of horror appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 3A Halloween horror story : What was it?A Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 2

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 3A Halloween horror story : What was it?A Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 2

October 21, 2014

What’s new in oral history?

Preparing a new edition of an oral history manual, a decade after the last appeared, highlighted dramatic changes that have swept through the field. Technological development made previous references to equipment sound quaint. The use of oral history for exhibits and heritage touring, for instance, leaped from cassettes and compact discs to QR codes and smartphone apps. As oral historians grew more comfortable with new equipment, they expanded into video and discovered the endless possibilities of posting interviews, transcripts, and recordings on the Internet. Having found a way to get oral history off the archival shelves and into the community, interviewers also had to consider the ethical and legal issues of exposing interviewees to worldwide scrutiny.

Over the last decade, the Internet left no excuses for parochialism. As the practice of oral history grew more international, a manual could neither address a single nation nor ignore the rest of the world. Wherever social, political, or economic turmoil has occurred, oral histories have recorded the change — because state archives tend to reflect the old regimes. War, terrorism, hurricanes, floods, fires, pandemics, and other natural and human-made disasters spurred interviews with those who endured trauma and tragedy, and required interviewers to adjust their approaches. Issues of empathy for those suffering emotional distress increasingly became part of the discourse among oral historians. At the same time, the use of interviewing grew more interdisciplinary, with historians examining the fieldwork techniques and needs of social scientists. Sociologists, anthropologists, and ethnographers have long employed interviewing, usually through participant observation. Many have gradually shifted from quantitative to qualitative analysis, raising questions about identifying their sources rather than rendering them anonymous, and bringing their methods closer to oral history protocols.

Evergreen Protective Association volunteer recording an oral history by Baltimore Heritage. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Evergreen Protective Association volunteer recording an oral history by Baltimore Heritage. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. New theoretical interests developed, particularly around memory studies. Oral historians became more concerned about not only what people remember, but also what they forget, and how they express these memories. Weighing the relationship between language and thought, and suggesting that that outward behavior reflects underlying signs, narrative theory has challenged the notion of objective history. It sees the past as recalled and recounted as simply a construction, shaped by the way it is told. Memory theories have dealt with the way suggestive questions can reshape memories, and the way recent experiences can block out memories of earlier ones. These theories suggest that people reconstruct memories of past experiences rather than mentally retrieve exact copies of them.

An increasingly litigious culture raised other concerns for oral historians. Lawsuits have alleged that some online interviews are defamatory. A court case with international implications arose when the United States supported British police efforts to subpoena closed interviews that might shed light on a murder case in Northern Ireland, exposing the vulnerability of oral history to judicial intervention. Although the courts treated closed interviews seriously and limited the amount of material to be opened, the case reminded oral historians that they could not promise absolute confidentiality when dealing with sensitive and possibly criminal issues.

It has been breathtaking to document the scope of change in oral history over the last two decades, and sobering to see how dated it made much of the past information and even some of the language. Looking back over the past decade also provided some reassurance about continuity. While it sometimes seems that everything about the practice of oral history has changed, the personal dynamics of conducting an interview have remained very much intact. Whether sitting down face-to-face or using some means of electronic communication, the human interaction of the interview has stayed the same. So have the basic steps: the interviewer’s need for prior research; for knowing how to operate the equipment; for crafting thoughtful, open-ended questions; for establishing rapport; for listening carefully and following up with further questions; and for doing everything possible to elicit candid and substantive responses.

I was glad to see so many of these new trends prominently displayed at the Oral History Association’s recent meeting in Madison, Wisconsin, (October 8-12) where sessions focused on oral history “in motion.” Motion aptly describes the forward-looking nature of oral history, with its expanding methodology and embrace of the latest technology, as well as its eagerness to confront established narratives with alternative voices.

The post What’s new in oral history? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingThe Salem Witch Trials [infographic]A preview of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

Related StoriesRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingThe Salem Witch Trials [infographic]A preview of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

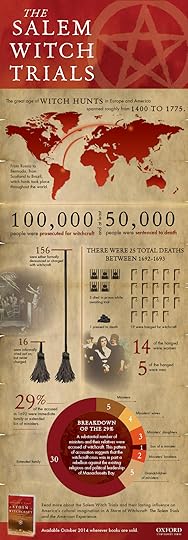

The Salem Witch Trials [infographic]

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692-1693 were by far the largest and most lethal outbreak of witchcraft hysteria in American history. Yet Salem was just one of many incidents during the Great Age of Witch Hunts which took place throughout Europe and her colonies over many centuries. Indeed, by European standards, Salem was not even a large outbreak. But what exactly were the factors that made Salem stand out?

In A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience, Emerson Baker places the Salem trials in their broader context and reveals why it has become an enduring legacy. He explains why the Salem crisis marked a turning point in colonial history from Puritan communalism to Yankee independence, from faith in collective conscience to skepticism toward moral governance. Below is an infographic detailing some of the numbers involved in Salem and other witch hunts.

Download the infographic in jpg or pdf.

Headline image credit: Witchcraft at Salem Village. Engraving. The central figure in this 1876 illustration of the courtroom is usually identified as Mary Walcott. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Salem Witch Trials [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCaught in Satan’s StormGeorge Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witchRace, sex, and colonialism

Related StoriesCaught in Satan’s StormGeorge Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witchRace, sex, and colonialism

Early blues and country music

Beginning in the early 1920s, and continuing through the mid 1940s, record companies separated vernacular music of the American South into two categories, divided along racial lines: the “race” series, aimed at a black audience, and the “hillbilly” series, aimed at a white audience. These series were the precursors to the also racially separated Rhythm & Blues and Country & Western charts, and arguably the source of the frequent racial divisions of today’s recording industry. But a closer examination reveals that the two populations rely heavily on many of the same musical resources, and that early blues and country music exhibit thorough interpenetration.

Many admirers of early blues and country music observe that black and white musicians from the 1920s to the 1940s share much with respect to repertoire and genre, and that the separation of the two on commercial recordings grew out of the prejudices of record companies. It becomes even more apparent how deeply intertwined the two traditions are when we examine blues and country musicians’ shared stock of schemes. Schemes are preexisting harmonic grounds and melodic structures that are common resources for the creation of songs. A scheme generates multiple distinct songs, with different lyrics and titles. Many schemes generated songs in both blues and country music.

There are several different types of blues and country schemes. One type is a harmonic progression that combines with one particular tune. The “Trouble In Mind” scheme, for example, generates both Bertha Chippie Hill’s “Trouble in Mind” (1) and the Hackberry Ramblers’ “Fais Pas Ça” (2). Both use the same harmonic progression, and the two melodies have relatively slight variation. Hill recorded for the “race” series, and the Hackberry Ramblers for the “hillbilly” series.

1. Bertha “Chippie” Hill, “Trouble in Mind” (Bertha “Chippie” Hill—Document Records)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/1.trouble-in-mind.wav2. Hackberry Ramblers, “Fais Pas Ça” (Jolie Blonde—Arhoolie Productions)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/2.fais-pas-ca.wavA second type of scheme is a preexisting harmonic progression that musicians associate primarily with a specific tune, which they set to lyrics about various subjects, but which they also use to support original melodies. In the “Frankie and Johnny” scheme, the same melody combines with lyrics about Frankie’s shooting of Johnny (or Albert) (3), the Boll Weevil infestation at the turn of the twentieth century (4), and the gambler Stack O’Lee, who shot and killed fellow gambler Billy Lyons (5). Singers also use the harmonic progression to support original melodies, with lyrics about Frankie (6), Stack O’Lee (7), or another subject (8).

In all of the examples, the same correspondence between lyrics and harmony is evident in the harmonic shift that accompanies the completion of the opening rhyming couplet, on the words “above” (3), “your home” (4), “road” (5), “beer” (6), the first “Stack O’Lee” (7), and “that line” (8), and in the harmonic shifts that accompany emphasized words in the refrain, on the words “man” and “wrong” (3, 5, and 6), “no home” and “no home” (4), “bad man” and “Stack O’Lee” (7), and “bad” and “bad” (8). Four of the recordings given here are from the “race” labels, and two are from the “hillbilly” labels, but the same scheme generates all of them.

Jimmie Rodgers. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Jimmie Rodgers. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 3. Jimmie Rodgers, “Frankie and Johnny” (The Essential Jimmie Rodgers—Sony)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/3.franky-and-johnny.wav4. W. A. Lindsey, “Boll Weevil” (People Take Warning—Tomkins Square)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/4.boll-weevil.wav5. Ma Rainey, “Stack O’Lee Blues” (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom—Yazoo)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/5.stack-olee-blues.wav6. Charley Patton, “Frankie and Albert” (Charley Patton Complete Recordings—JSP Records)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/6.frankie-and-albert.wav7. Mississippi John Hurt, “Stack O’Lee” (Before the Blues—Yazoo)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/7.stack-olee-blues.wav8. Henry Thomas, “Bob McKinney” (Texas Worried Blues—Document Records)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/8.bob-mckinney.wavA third type of scheme is a preexisting harmonic progression that musicians use primarily to support original melodies. This type of scheme is the most productive, and often supports countless melodies. The most well-known and productive of this type is the standard twelve-bar blues scheme. All seven of the following recordings (9–15)—four from the “race” series and three from the “hillbilly” series—contain original melodies combined with the standard twelve-bar blues harmonic progression, and all demonstrate the AAB poetic form that typically combines with the scheme, in which singers state the opening A line of a couplet twice and follow it with one statement of the rhyming B line.

9. Ida Cox, “Lonesome Blues” (Ida Cox Complete Recorded Works—Document Records)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/9.lonesomeblues.wav10. Charley Patton, “Moon Going Down” (Charlie Patton Founder of the Delta Blues—Mastercopy Pty Ltd)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/10.moon-going-down.wav11. Jesse “Babyface” Thomas, “Down in Texas Blues” (The Stuff that Dreams are Made Of)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/11.down-in-texas-blues.wav12. Lonnie Johnson, “Mr. Johnson’s Blues No. 2” (A Smithsonian Collection of Classic Blues Singers—Sony/Smithsonian)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/12.mr-johnsons-blues-no2.wav13. W. Lee O’Daniel & His Hillbilly Boys, “Dirty Hangover Blues” (White Country Blues—Sony)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/13.dirty-hangover-blues.wav14. Jesse “Babyface” Thomas, “Down in Texas Blues” (The Stuff that Dreams are Made Of) (White Country Blues—Sony)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/14.haunted-road-blues.wav15. Carlisle & Ball, “Guitar Blues” (White Country Blues—Sony)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/15.guitar-blues.wavA fourth type of scheme is a preexisting melodic structure whose harmonizations display considerable variance and yet also certain requirements. The following four examples—two by black musicians and two by white musicians—are all realizations of the “Sitting on Top of the World” scheme, and use the same melodic structure. Their harmonizations are in some ways quite similar—for example, all four harmonize the beginning of the second, rhyming line with the same harmony, and accelerate the rate of harmonic change going into the cadence—but the harmonizations vary more than the melodic structure.

16. Tampa Red, “Things ‘Bout Coming My Way No. 2” (Tampa Red the Guitar Wizard—Sony)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/16.things-bout-comin-my-way-no2.wav17. Bill Broonzy, “Worrying You Off My Mind” (Big Bill Broonzy Good Time Tonight—Sony)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/17.worrying-you-off-my-mind.wav18. Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys, “Sittin’ on Top of the World” (Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys Anthology—Puzzle Productions)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/18.sittin-on-top-of-the-world.wav19. The Carter Family, “I’m Sitting on Top of the World” (On Border Radio—Arhoolie)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/19.im-sitting-on-top-of-the-world.wavFinally, a fifth type of scheme is a preexisting melodic structure for which performers have little shared conception of the harmonic progression. The last four examples—one by a black musician and three by white musicians—are all realizations of the “John Henry” scheme, and use the same melodic structure, but very different harmonic progressions. Riley Puckett, in his instrumental version, uses only one harmony throughout (20). Woody Guthrie uses two harmonies (21). The Williamson Brothers & Curry also use two harmonies, but arrive at a much different harmonization than Guthrie (22). Leadbelly uses three harmonies (23).

20. Riley Puckett, “A Darkey’s Wail” (White Country Blues—Sony)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/20.a-darkeys-wail.wav21. Woody Guthrie, “John Henry” (Woody Guthrie Sings Folk Songs—Smithsonian Folkways Recordings)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/21.john-henry.wav22. Williamson Brothers & Curry, “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand” (Anthology of American Folk Music—Smithsonian Folkways Recordings)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/22.gonna-die-with-my-hammer-in-my-hand.wav23. Leadbelly, “John Henry” (Lead Belly’s Last Sessions— Smithsonian Folkways Recordings)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/23.john-henry.wavRecord companies presented American vernacular music in the context of a racial divide, but examining the common stock of schemes helps to reveal how extensively black and white musical traditions are intertwined. There are stylistic differences between blues and country music, but many differences lie on the surface, while on a deeper level the two populations frequently rely on the same musical foundations.

Headline image credit: Fiddlin’ Bill Hensley. Asheville, North Carolina. Public domain via Library of Congress.

The post Early blues and country music appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEarly blues and country music - EnclosureCorporate short-termism, the media, and the self-fulfilling prophecyRace, sex, and colonialism

Related StoriesEarly blues and country music - EnclosureCorporate short-termism, the media, and the self-fulfilling prophecyRace, sex, and colonialism

Corporate short-termism, the media, and the self-fulfilling prophecy

The business press and general media often lament that firm executives are exhibiting “short-termism”, succumbing to the pressure by stock market investors to maximize quarterly earnings while sacrificing long-term investments and innovation. In our new article in the Socio-Economic Review, we suggest that this complaint is partly accurate, but partly not.

What seems accurate is that the maximization of short-term earnings by firms and their executives has become somewhat more prevalent in recent years, and that some of the roots of this phenomenon lead to stock market investors. What is inaccurate, though, is the assumption that investors – even if they were “short-term traders” – would inherently attend to short-term quarterly earnings when making trading decisions. Namely, even “short-term trading” (i.e. buying stocks with the aim to sell them after few minutes, days, or months) does not equal or necessitate “short-term earnings focus”, i.e., making trading decisions based on short-term earnings (let alone based on short-term earnings only). This means that in case the media observes – or executives perceive – that firms are pressured by stock market investors to focus on short-term earnings, such a pressure is illusionary, in part.

The illusion, in turn, is based on the phenomenon of “vociferous minority”: a minority of stock investors may be focusing on short-term earnings, causing some weak correlation between short-term earnings and stock price jumps / drops. But the illusion is born when this gets interpreted as if most or all investors (i.e., the majority) would be focusing on short-term earnings only. Alas, such an interpretation may, in the dynamic markets, lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy – whereby an increasing number of investors join the vociferous minority and focus increasingly on short-term earnings (even if still not the majority of investors would focus on short-term earnings only). And more importantly – or more unfortunately – firm executives may start to increasingly maximize short-term earnings, too, due to the (inaccurate) illusion that the majority of investors would prefer that.

Rolls Royce, by Christophe Verdier. CC-BY-2.0 vis Flickr.

Rolls Royce, by Christophe Verdier. CC-BY-2.0 vis Flickr.A final paradox is the role of the media. Of course, the media have good intentions in lamenting about short-termism in the markets, trying to draw attention to an unsatisfactory state of affairs. However, such lamenting stories may actually contribute to the emergence of the self-fulfilling prophecy. Namely, despite the lamenting tone of the media articles, they are in any case emphasizing that the market participants are focusing just on short-term earnings. This contributes to the illusion that all investors are focusing on short-term earnings only – which in turn may lead a bigger majority of investors and firms to actually join the minority’s bandwagon, in the illusion that everyone else is doing that too.

Should the media do something different, then? Well, we suggest that in this case, the media should report more on “positive stories”, or cases whereby firms have managed to create great innovations with a patient, longer-term focus. The media could also report on an increasing number of investors looking at alternative, long-term measures (such as patents or innovation rates) instead of short-term earnings.

So, more stories like this one about Rolls-Royce – however, without claiming or lamenting that most investors are just wanting “quick results” (i.e., without portraying cases like Rolls-Royce just as rare exceptions). Such positive stories could, in the best scenario, contribute to a reverse, self-fulfilling prophecy – whereby more and more investors, and thereafter firm executives, would replace some of the excessive focus on short-term earnings that they might currently have.

The post Corporate short-termism, the media, and the self-fulfilling prophecy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Hunger Games and a dystopian Eurozone economyOn the importance of independent, objective policy analysisChina’s economic foes

Related StoriesThe Hunger Games and a dystopian Eurozone economyOn the importance of independent, objective policy analysisChina’s economic foes

October 20, 2014

Questions surrounding open access licensing

Open access (OA) publishing stands at something of a crossroads. OA is now part of the mainstream. But with increasing success and increasing volume come increasing complexity, scrutiny, and demand. There are many facets of OA which will prove to be significant challenges for publishers over the next few years. Here I’m going to focus on one — licensing — and discuss how the arguments seen over licensing in recent months shine a light on the difference between OA as a movement, and OA as a reality.

Today’s authors face a number of conflicting pressures. Publish in a high impact journal. Publish in a journal with the correct OA options as mandated by your funder. Publish in a journal with the correct OA options as mandated by your institution. Publish your article in a way which complies with government requirements on research excellence. They are then met by a wide array of options, and it’s no wonder we at OUP sometimes receive queries from authors confused as to which OA option they should choose.

One of the most interesting aspects of the various surveys Taylor & Francis (T&F) have conducted on open access over the past year or two has been the divergence between what authors say they want, and what their funders/governments mandate. The T&F findings imply that, whilst there is generally a shared consensus as to what is meant by accessible, there are divergent positions and preferences between funders and researchers as to what constitutes reasonable reuse. T&F’s surveys always reveal the most restrictive licences in the Creative Commons (CC) suite such as Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No-Derivs (CC BY-NC-ND) to be the most popular, with the liberal Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence coming in last. This neither squares with the mandates of funders which are usually, but not always, pro CC BY, or author behaviour at OUP, where CC BY-NC-ND usually comes in a resounding third behind CC BY and CC BY-NC where it’s available. It’s not a dramatic logical step to think that proliferation may lead to confusion, but given the conflicting evidence and demand, and potential for change, it’s logical for publishers to offer myriad options. At the same time elsewhere in the OA space we have a recent example of pressure to remove choice.

Creative Commons. Image by Giulio Zannol. CC BY 2.0 via giuli-o Flickr.

Creative Commons. Image by Giulio Zannol. CC BY 2.0 via giuli-o Flickr.In July 2014, the International Association of Science, Technical and Medical Publishers (STM) released their ‘model licences’ for open access. These were at their core a series of alternatives for, and extensions to the terms of the established CC licences. STM’s new addition did not go down well in OA circles, as a ‘Global Coalition’ subsequently called for their withdrawal. One of the interesting elements of the Coalition’s call was that, in amongst some very valid points about interoperability, etc. it fell back on the kind of language more commonly associated with a sermon to make the STM actions seem incompatible with some fundamental precepts about the practice of science: “let us work together in a world where the whole sum of human knowledge… is accessible, usable, reusable, and interoperable.” At root, it could be interpreted that the Coalition was using positive terminology to frame an essentially negative action – barring a new entry to the market. Personally, I don’t have a strong opinion on the new STM licences. We don’t have any plans to adapt them at OUP (we use CC). But it was odd and striking that rather than letting a competitor to the CC status quo exist and in all likelihood fail, some serious OA players felt the need to call for that competitor’s withdrawal.

This illustrates one of the central challenges of the dichotomy of OA. On one hand you have OA as a political movement seeking to replace commercial interests with self-organized and self-governed communities of interest – a bottom-up aspiration for the common good, often suggested to be applied in quite restricted ways, usually adhering to the Berlin, Budapest, and Bethesda declarations. On the other you have OA as a top-down pragmatic means to an end, aiming to improve the flow of research and by extension, economic performance. The OA pragmatist might suggest that it’s fine for an author to be given the choice of liberal or less liberal OA licences, as long as they meet the basic criteria of being free to read and easy to re-use. The OA dogmatist might only be satisfied with the most liberal licence, and with OA along the terms they’ve come to believe is the correct interpretation of their core precepts. The danger of this approach is that there is a ‘right’ and a ‘wrong’ and, as can be seen from the language of the Global Coalition in responding to the STM licences, that can very easily translate into; “If you’re not with us, you’re against us.”

Against this backdrop, publishers find themselves in a thorny position. Do you (a) respect author choice, but possibly at some expense of simplicity, or do you (b) offer fewer options, but potentially leave members of the scholarly community feeling dissatisfied or disenfranchised by your standard option?

Oxford University Press at the moment chooses option (a), as we feel this is the more inclusive way to proceed. To me at least it feels right to give your customers choice. But there is an argument for streamlining processes, avoiding confusion, and giving users consistent knowledge of what to expect. Nature Publishing Group (NPG), for example, recently announced that as part of their move to full OA for Nature Communications they would be making CC BY their default, and only allowing other options on request. This is notable in as much as it’s a very strong steer in a particular direction, while not ruling out everything else. NPG has done more than most to examine the choice issue – changing the order of their licences to see what authors select, sometimes varying charges, etc. Empirical evidence such as this is essential for a viable and credible resolution to the future of OA licensing. Perhaps the Global Coalition should have given a more considered and less emotional response to the STM licences. Was repudiation necessary in a broad OA community which should be able to recognise and accept different variants of OA? It would be a shame if all the positive impacts of open access for the consumer come hand in hand with a diminution of scholarly freedom for the producer.

The opinions and other information contained in this blog post and comments do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Oxford University Press.

The post Questions surrounding open access licensing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive key moments in the Open Access movement in the last ten yearsRace, sex, and colonialismIs American higher education in crisis?

Related StoriesFive key moments in the Open Access movement in the last ten yearsRace, sex, and colonialismIs American higher education in crisis?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers