Oxford University Press's Blog, page 752

October 13, 2014

From Imperial Presidency to Double Government

In the wake of US attacks on ISIS elements in Syria, the continuity in US national security policy has become ever more apparent. American presidents, whatever their politics or campaign rhetoric, over and over stick with essentially the same security programs as their predecessors. President Obama is but the most recent example. He has continued or even expanded numerous Bush administration policies including rendition to third countries, military detention without trial, denial of legal counsel to prisoners, drone strikes, offensive cyber-weapons, and whistleblower prosecutions.

Even seasoned insiders profess bewilderment. As a candidate, the President extolled the virtues of a nuclear-free world and promised to vigorously pursue disarmament. Yet he has recently approved plans for enormous new expenditures in a major ramping-up of the US nuclear arsenal. “A lot of it is hard to explain,” former Senator Sam Nunn told the New York Times. “The president’s vision was a significant change in direction. But the process has preserved the status quo.” The playbill changes, but the play does not.

The conventional explanation lies in the phenomenon described by the late historian Arthur Schlesinger—an imperial presidency. A series of overly-assertive chief executives, according to the theory, have dominated legislators and judges, knocking America’s carefully-balanced separation of powers out of kilter. Vietnam, Watergate, domestic CIA spying and other abuses all were attributed to this outsized presidency. The presumed remedy was to try to tie down the executive Gulliver with a web of new constraints, such as the War Powers Resolution, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, and a watchful new court and oversight committees.

It didn’t work. Forty years later, the United States has moved beyond an imperial presidency to a system in which the gargantuan US security apparatus not only has broken free of constraints but has engulfed even the presidency itself. Contemporary US security policy is seldom formulated in the Oval Office and handed down to compliant managers in the military, intelligence, and law enforcement agencies. Instead, nerve-center policies ranging from the troop buildup in Afghanistan to ABM deployment to NSA surveillance percolate up from the Pentagon, Langley, Fort Meade, and myriad Beltway facilities with no public names. With rare exceptions, that is where options originate, plans are formulated, and strategy ultimately defined.

Aerial photograph of the National Security Agency by Trevor Paglen. Commissioned by Creative Time Reports, 2013. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Aerial photograph of the National Security Agency by Trevor Paglen. Commissioned by Creative Time Reports, 2013. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.The resulting programs take on a life of their own, feeding on caution, living off the bureaucratic land, run by an entrenched and elaborate network of well-meaning careerists and political appointees who are invested in the status quo, committed to increased payrolls and broader missions, and able to outlast the shifting preferences of elected officials. The programs are, in economic terms, “sticky down”—easier to grow than shrink.

Thus when the CIA asked for authority to expand its drone program and launch new paramilitary operations, President Obama famously told his advisers, “The CIA gets what it wants.” Security managers elsewhere also get what they want. During deliberations on the Afghanistan troop surge, the President complained that the military “are not going to give me a choice.” The admirals and generals, his staff said, were “boxing him in.” More recently, the White House claimed that President Obama was unaware of NSA spying on world leaders; Secretary of State John Kerry explained that some US surveillance activities are “on autopilot.” The President in response formed a supposedly independent panel to safeguard civil liberties and restore public confidence—which, it turns out, operated under the auspices of Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, who oversees the NSA.

America’s new security system is best captured by an earlier concept: “double government.” The term is Walter Bagehot’s, the celebrated scholar of the English Constitution, who in 1867 described how Britain’s government had slowly changed in substance but not in form as it moved to a “disguised republic.” The monarchy and House of Lords, he suggested, provided the grand public façade needed to generate public deference, while another set of institutions—the House of Commons, the cabinet, and prime minister—efficiently worked behind the scenes to carry out the actual work of governing.

In the realm of national security, the US government also has changed in substance but not in form—but American double government has evolved in the opposite direction, toward greater centralization and away from democracy. Congress, the presidency, and the courts appear to exercise decisional authority, yet their control is increasingly illusory. The real shaping of security policy is carried out quietly, in highly classified facilities, by anonymous managers the public never sees.

As the NSA’s ubiquity gradually has been unveiled, the Watergate-era questions were asked again: “What did the President know and when did he know it?” The answers to those questions now matter little, however. The remedies of earlier times have proven ineffectual, and the structural forces that eroded accountability and empowered the security elite remain strong. The system’s vaunted capacity for self-correction is therefore severely limited. In this new epoch of American double government, the disquieting question is: Who really is in charge? Unless the United States confronts that question squarely, Congress, the judiciary, and the presidency itself will continue, slowly and quietly, to fade into museum pieces.

The post From Imperial Presidency to Double Government appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe need to reform whistleblowing lawsNine types of meat you may have never triedWhat exactly is intelligence?

Related StoriesThe need to reform whistleblowing lawsNine types of meat you may have never triedWhat exactly is intelligence?

Nine types of meat you may have never tried

Sometimes what is considered edible is subject to a given culture or region of the world; what someone from Nicaragua would consider “local grub” could be entirely different than what someone in Paris would eat. How many different types of meat have you experienced? Are there some types of meat you would never eat? Below are nine different types of meat, listed in The Oxford Companion to Food, that you may not have considered trying:

Camel: Still eaten in some regions, a camel’s hump is generally considered the best part of the body to eat. Its milk, a staple for desert nomads, contains more fat and slightly more protein than cow’s milk.

Beaver: A beaver’s tail and liver are considered delicacies in some countries. The tail is fatty tissue and was greatly relished by early trappers and explorers. Its liver is large and almost as tender and sweet as a chicken’s or a goose’s.

Agouti: Also spelled aguti; a rodent species that may have been described by Charles Darwin as “the very best meat I ever tasted” (though he may have been actually describing a guinea pig since he believed agouti and cavy were interchangeable names).

Armadillo: Its flesh is rich and porky, and tastes more like possum than any other game. A common method of cooking is to bake the armadillo in its own shell after removing its glands.

Hedgehog. Photo by Kalle Gustafsson. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

Hedgehog. Photo by Kalle Gustafsson. CC BY 2.0 via FlickrCapybara: The capybara was an approved food by the Pope for traditional “meatless” days, probably since it was considered semiaquatic. Its flesh, unless prepared carefully to trim off fat, tastes fishy.

Hedgehog: A traditional gypsy cooking method is to encase the hedgehog in clay and roast it, after which breaking off the baked clay would take the spines with it.

Alligator: Its meat is white and flaky, likened to chicken or, sometimes, flounder. Alligators were feared to become extinct from consumption, until they started becoming farmed.

Iguana: Iguanas were an important food to the Maya people when the Spaniards took over Central America. Its eggs were also favored, being the size of a table tennis ball, and consisted entirely of yolk.

Puma: Charles Darwin believed he was eating some kind of veal when presented with puma meat. He described it as, “very white, and remarkably like veal in taste”. One puma can provide a lot of meat, since each can weigh up to 100 kg (225 lb).

Has this list changed the way you view these animals? Would you try alligator meat but turn your nose up if presented with a hedgehog platter?

Headline Image: Street Food at Wangfujing Street. Photo by Jirka Matousek. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post Nine types of meat you may have never tried appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat’s your gut feeling?What exactly is intelligence?Does political development involve inherent tradeoffs?

Related StoriesWhat’s your gut feeling?What exactly is intelligence?Does political development involve inherent tradeoffs?

October 12, 2014

What exactly is intelligence?

Ask anybody that question and you will probably get a different answer every time. Most would argue that intelligence is limited to mankind and give examples of brainy people like Einstein or Newton.

Others might identify it as being clever, good in exams or being smart, having a high IQ. But was Einstein particularly intelligent or Newton? Both were very gifted at mathematics and certainly imaginative but outside that, their lives didn’t seem to be any smarter or express particular cleverness than millions of others; in some respects perhaps the opposite.

We don’t know how well either would have done in IQ tests. Although successful people generally have a higher IQ than average, the correlation with success is chequered and not outstanding. So it is hardly surprising one recent article found at least 70 different versions of intelligence and then proceeded to provide a novel summary of its own.

Intelligence is an aspect of behaviour, and behaviour is the response to our environment, more properly the signals we perceive. The word intelligence is derived from the Latin interlegere, which simply means to choose between. Choice implies something in past behaviour has opened up two or more different courses of future action. Skill in assessing and taking the right choice within the present context we should describe as intelligent behaviour.

IQ supposedly measures some intrinsic property of the individual brain but actually it was set up simply to identify pupils with special needs. The present test sets problems requiring some numeracy, spatial recognition, and logic; it is largely academic in character but also strongly cultural.

We can see more clearly what intelligence is about if we take away the present cultural bias for intelligence. Go back 50-100,000 years to earlier mankind. The problems he/she faced were basic: finding food and mates, and avoiding predators. Failure led to premature death; success increased sibling number thus fulfilling the basic biological property we call fitness. Advanced society has simply removed the fundamental base of intelligence.

No wonder it is so difficult to characterise. One psychologist Howard Gardener has imaginatively identified all kinds of intelligence, emotional and physical intelligence, linguistic, musical and spatial intelligence, and logico-mathematical intelligence. All except the last one would be crucial for early mankind’s survival.

But I don’t see Einstein or Newton genius though they are in logico-mathematical intelligence as doing particularly well 100,000 years ago. Furthermore mathematics simply didn’t exist then except perhaps simple numeracy. It is a modern day activity in a society in which the fundamentals of survival are no longer pressing.

Gymnocalycium stellatum with flowers. Photo by Bff. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Gymnocalycium stellatum with flowers. Photo by Bff. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The most common view amongst psychologists is that intelligence relates to problem-solving and given that the quality does vary amongst individuals, a capacity for problem-solving. But then we are faced with a conundrum. All living things from bacteria plants to animals face the same basic issues of life, finding food whatever it is, finding mates, and avoiding predators; all these require problem-solving and the sheer variety of them for any one individual means the solution can’t be fixed in the genes as some sort of homunculus but necessitates assessment, a process that in some way incorporates knowledge of past history and the ability to choose between alternatives.

Even swimming bacteria have to choose between swimming towards food and away from poisons. To do the opposite is guaranteed disaster, the decision leading to survival and fitness is obvious. But the assessment there does not involve brains or neural pathways; bacteria simply use a protein network whereas animals use a neural network.

It is the complexity of networks of interacting molecules or cells that provide for intelligent behaviour. In swarm intelligence interactions relatively simple in number occur between effectively cloned organisms in the self-organising beehive or colony.

Similar problems are faced by higher plants. Plant behaviour is not familiar to many; are they not often considered still life?

But higher plants simply work on a different time scale. They lack a nervous system but have complex chemical communication between millions of cells that forms the basis of assessment and leads to decisions within the context of detailed environmental perception.

Much visible behaviour requires growth and in virtually all organisms, growth can be a slow business. Plants forage for the resources of light, minerals, and water. They possess self-recognition and recognise competitors. They possess the capabilities of what we call learning and memory, particularly in response to herbivory. But all this in molecules, not nerves, although electrical connection occurs and is used to transfer information. Intelligent behaviour is as essential for them as any other organism.

The underpinning behaviour is just as surprising. Leaves maintain a relatively constant internal temperature, roots sense and seek out resources, the cambium (a kind of inner skin) comparatively assesses the behaviour of branch roots or shoots and awards additional resources to those which are more likely to be profitable in the future.

These are positive responses to signals in their environment that will increase fitness. Selection also operates in mating by a variety of methods to ensure the most fit do mate. Self-organisation is a fundamental plant attribute. Intelligent behaviour is a holistic quality expressed only by the individual and in plants it finds its most surprising expression but without it plants would not be here.

Headline image credit: Photograph of a carnivorous plant, cultivated by Martha Miller, part of a display featured at a First Friday event at the Chemical Heritage Foundation, Philadelphia, PA, USA, on November 6, 2009. Photograph by Conrad Erb, Chemical Heritage Foundation. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What exactly is intelligence? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlato and contemporary bioethicsRecurring decimals, proof, and ice floesRheumatology through the ages

Related StoriesPlato and contemporary bioethicsRecurring decimals, proof, and ice floesRheumatology through the ages

Does political development involve inherent tradeoffs?

For years, social scientists have wondered about what causes political development and what can be done to stimulate it in the developing world. By political development, they mean the creation of democratic governments and public bureaucracies that can effectively respond to citizens’ demands. Early in the Cold War era, most scholars were optimistic and assumed that political development would occur quickly and easily in the developing world. They expected that countries would democratize and that their governments would generate lots of state capacity to provide new public services. But, as time wore on, many observers came to realize that the process was often fitful.

Some scholars became convinced that countries faced inherent developmental tradeoffs. In the 1970s, Samuel Huntington and Joan Nelson — in a book titled No Easy Choice — warned that developing countries could not simultaneously sustain democracy and economic growth policies. They felt that democracy led to pressures for economic redistribution, which would impede growth, but also recognized that excluding people from democratic participation created turmoil. More recently, Francis Fukuyama (writing in the Journal of Democracy) concluded that countries couldn’t have a vigorous democracy unless their governments possessed significant state capacity. Herein lay a tradeoff: for a central government to uphold the rule of law — something necessary for a robust democracy — it has to concentrate power. But citizens in fledgling democracies often (justifiably) worry about governments holding too much power. Fukuyama suggested that political development was double-edged: implanting a strong democracy and building state capacity were in tension.

Around the time Fukuyama wrote his cautionary article, I set out to investigate how countries in the developing world had acquired state capacity in the past. I embarked on this research as American involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq was making one thing clear: it’s really hard to build functional and effective states. I thought case studies might clarify how some countries had historically generated state capacity through more organic means, which might be useful knowledge for policymakers wanting to build up weak or failed states today.

Sheep Mustering In Argentinian Patagonia. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Sheep Mustering In Argentinian Patagonia. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.I studied six countries in Latin America and Africa — Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Ghana, Mauritius, and Nigeria — and discovered a striking pattern. I found that when each of them experienced their first major commodity boom (in commodities as diverse as cattle, copper, sugar, and wheat), there were groups involved in the production and marketing of these goods that asked their governments for similar things. They wanted the state to provide new transportation infrastructure and help them obtain finance, so they could enlarge their operations. The situation seemed like a “win-win”: exporters could expand their businesses, and governments would stimulate economic growth.

But, curiously, governments often spurned these requests. I found that only when exporters were part of the governing coalition — meaning they were closely allied with politicians — did the government assist them. This was the case in Argentina, Chile, and Mauritius. When exporters were politically marginalized, governments refused to help them. In fact, governments worked against them, taxing their goods heavily and redistributing that wealth into boondoggles. Governments in Colombia, Ghana, and Nigeria essentially chose to sacrifice economic growth in order to redirect export wealth to their political cronies. These choices had lasting consequences. Over the longer term, Argentina, Chile, and Mauritius built fairly capable states, while the other countries did not.

My professional self was elated by these findings, since researchers hadn’t emphasized this coalitional perspective to analyze state building. And yet I was troubled by what seemed to be a tradeoff present in my “success” stories. The countries that expanded their state capacity often did so repugnantly. The Chilean government invaded and “pacified” the lands of the Mapuche Indians. It then sold the land to established landed elites, who wanted to prevent others from ending their stranglehold on the country’s farmland. In Argentina, ranchers in Buenos Aires province got the government to go to war with the country’s other littoral provinces, where upstart ranchers were challenging the economic hegemony of Buenos Aires pastoralists. The government also launched a ghastly military campaign to subjugate Indian tribes that were preventing ranchers from moving their herds southward into Patagonia. And Mauritius created a legal labyrinth to harass people who had legally left the harsh conditions of sugar estates in search of a better life. The government intimidated many of them back onto plantations, where some historians liken the working conditions to slavery. State building came at the expense of the weak.

I wrestle with these findings because governments with considerable state capacity can do lots of good things, especially for the powerless. They can uphold the rule of law, ensure democratic accountability, and provide public goods, such as education systems and clean water. And weak or failing states are environments where insurgent and terrorist groups can flourish. So there are manifest reasons why we should want countries to expand their state capacity. Nevertheless, the lessons from my book do not translate easily into sensible policy, since state building was doubled-edged. I hope that state building doesn’t require a tradeoff between enhancing government capabilities and treating vulnerable groups fairly. But one thing is clear: state building is politically charged. Building effective states isn’t simply a technical endeavor, but a deeply political process — one with enduring consequences.

Featured image: USAID works with Nigerians to improve agriculture, health, education, and governance. By USAID Africa Bureau. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Does political development involve inherent tradeoffs? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the USThe anti-urban tradition in America: why Americans dislike their citiesWhen tragedy strikes, should theists expect to know why?

Related StoriesGangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the USThe anti-urban tradition in America: why Americans dislike their citiesWhen tragedy strikes, should theists expect to know why?

When tragedy strikes, should theists expect to know why?

My uncle used to believe in God. But that was before he served in Iraq. Now he’s an atheist. How could a God of perfect power and perfect love allow the innocent to suffer and the wicked to flourish?

Philosophers call this the problem of evil. It’s the problem of trying to reconcile two things that at first glance seem incompatible: God and evil. If the world were really governed by a being like God, shouldn’t we expect the world to be a whole lot better off than it is? But given the amount, kind, and distribution of evil things on earth, many philosophers conclude that there is no God. Tragedy, it seems, can make atheism reasonable.

Theists—people who believe in God—may share this sentiment in some ways, but in the end they think that the existence of God and the existence of evil are compatible. But how could this be? Well, many theists attempt to offer what philosophers call a theodicy – an explanation for why God would allow evils of the sort we find.

Perhaps good can’t exist without evil. But would that make God’s existence dependent on another? Perhaps evil is the necessary byproduct of human free will. But would that explain evils like ebola and tsunamis? Perhaps evil is a necessary ingredient to make humans stronger and more virtuous. But would that justify a loving human father in inflicting similar evil on his children? Other theists reject the attempt to explain the existence of evils in our world and yet deny that the existence of unexplained evil is a problem for rational belief in God.

The central idea is simple: just as a human child cannot decipher all of the seemingly pointless things that her parent does for her benefit, so, too, we cannot decipher all of the seemingly pointless evils in our world. Maybe they really are pointless, but maybe they aren’t — the catch is that things would look the same to us either way. And if they would look the same either way, then the existence of these evils cannot be evidence for atheism over theism.

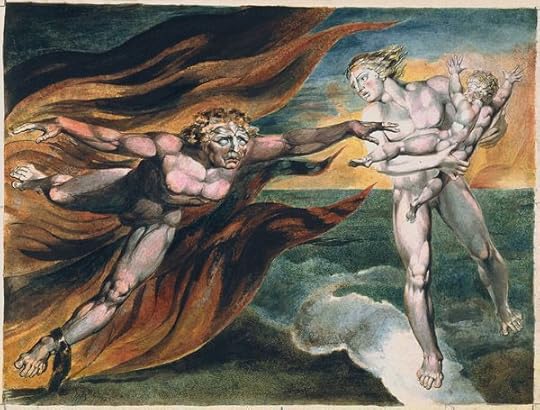

The Good and Evil Angels by William Blake. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Good and Evil Angels by William Blake. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Philosophers call such theists ‘skeptical’ theists since they believe that God exists but are skeptical of our abilities to decipher whether the evils in our world are justified just by considering them.

The debate over the viability of skeptical theism involves many issues in philosophy including skepticism and ethics. With regard to the former, how far does the skepticism go? Should theists also withhold judgment about whether a particular book counts as divine revelation or whether the apparent design in the world is actual design? With regard to the latter, if we should be skeptical of our abilities to determine whether an evil we encounter is justified, does that give us a moral reason to allow it to happen?

It seems that skeptical theism might invoke a kind of moral paralysis as we move through the world unable to see which evils further God’s plans and which do not.

Skeptical theists have marshalled replies to these concerns. Whether the replies are successful is up for debate. In either case, the renewed interest in the problem of evil has resurrected one of the most prevalent responses to evil in the history of theism — the response of Job when he rejects the explanations of his calamity offered by his friends and yet maintains his belief in God despite his ignorance about the evils he faces.

Headline image credit: Job’s evil dreams. Watercolor illustration by William Blake. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post When tragedy strikes, should theists expect to know why? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Second Vatican Council and John Henry NewmanFire in the nightPlato and contemporary bioethics

Related StoriesThe Second Vatican Council and John Henry NewmanFire in the nightPlato and contemporary bioethics

Plato and contemporary bioethics

Since its advent in the early 1970s, bioethics has exploded, with practitioners’ thinking expressed not only in still-expanding scholarly venues but also in the gamut of popular media. Not surprisingly, bioethicists’ disputes are often linked with technological advances of relatively recent vintage, including organ transplantation and artificial-reproductive measures like preimplantation genetic diagnosis and prenatal genetic testing. It’s therefore tempting to figure that the only pertinent reflective sources are recent as well, extending back — glancingly at most — to Immanuel Kant’s groundbreaking 18th-century reflections on autonomy. Surely Plato, who perforce could not have tackled such issues, has nothing at all to contribute to current debates.

This view is false — and dangerously so — because it deprives us of avenues and impetuses of reflection that are distinctive and could help us negotiate present quandaries. First, key topics in contemporary bioethics are richly addressed in Greek thought both within Plato’s corpus and through his critical engagement with Hippocratic medicine. This is so regarding the nature of the doctor-patient tie, medical professionalism, and medicine’s societal embedment, whose construction ineluctably concerns us all individually and as citizens irrespective of profession.

Second, the most pressing bioethical topics — whatever their identity — ultimately grip us not on technological grounds but instead for their bearing on human flourishing (in Greek, eudaimonia). Surprisingly, this foundational plane is often not singled out in bioethical discussions, which regularly tend toward circumscription. The fundamental grip obtains either way, but its neglect as a conscious focus harms our prospects for existing in a way that is most thoughtful, accountable, and holistic. Again a look at Plato can help, for his handling of all salient topics shows fruitfully expansive contextualization.

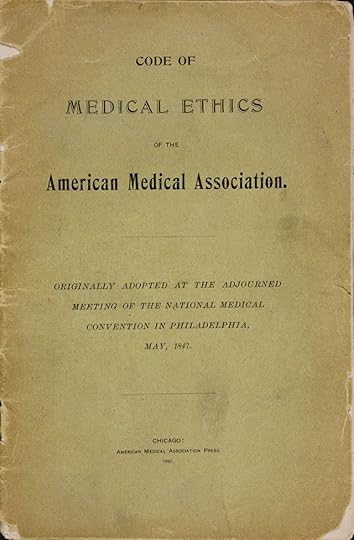

AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Public domain via Wikipedia Commons

AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Public domain via Wikipedia CommonsRegarding the doctor-patient tie, attempts to circumvent Scylla and Charybdis — extremes of paternalism and autonomy, both oppositional modes — are garnering significant bioethical attention. Dismayingly given the stakes, prominent attempts to reconceive the tie fail because they veer into paternalism, allegedly supplanted by autonomy’s growing preeminence in recent decades. If tweaking and reconfiguration of existing templates are insufficient, what sources not yet plumbed might offer fresh reference points for bioethical conversation?

Prima facie, invoking Plato, staunch proponent of top-down autocracy in the Republic, looks misguided. In fact, however, the trajectory of his thought — Republic to Laws via the Statesman — provides a rare look at how this profound ancient philosopher came at once to recognize core human fallibility and to stare firmly at its implications without capitulating to pessimism about human aptitudes generally. Captivated no longer by the extravagant gifts of a few — philosophers of Kallipolis, the Republic’s ideal city — Plato comes to appreciate for the first time the intellectual and ethical aptitudes of ordinary citizens and nonphilosophical professionals.

Human motivation occupies Plato in the Laws, his final dialogue. His unprecedented handling of it there and philosophical trajectory on the topic warrant our consideration. While the Republic shows Plato’s unvarnished confidence in philosophers to rule — indeed, even one would suffice (502b, 540d) — the Laws insists that human nature as such entails that no one could govern without succumbing to arrogance and injustice (713c). Even one with “adequate” theoretical understanding could not properly restrain himself should he come to be in charge: far from reliably promoting communal welfare as his paramount concern, he would be distracted by and cater to his own yearnings (875b). “Adequate” understanding is what we have at best, but only “genuine” apprehension — that of philosophers in the Republic, seen in the Laws as purely wishful — would assure incorruptibility.

The Laws’ collaborative model of the optimal doctor-patient tie in Magnesia, that dialogue’s ideal city, is one striking outcome of Plato’s recognition that even the best among us are fallible in both insight and character. Shared human aptitudes enable reciprocal exchanges of logoi (rational accounts), with patients’ contributing as equal, even superior, partners concerning eudaimonia. This doctor-patient tie is firmly rooted in society at large, which means for Plato that there is close and unveiled continuity between medicine and human existence generally in values’ application. From a contemporary standpoint, the Laws suggests a fresh approach — one that Plato himself arrived at only by pressing past the Republic’s attachment to philosophers’ profound intellectual and values-edge, whose bioethical counterpart is a persistent investment in the same regarding physicians.

If values-spheres aren’t discrete, it’s unsurprising that medicine’s quest to demarcate medical from non-medical values, which extends back to the American Medical Association’s original Code of Medical Ethics (1847), has been combined with an inability to make it stick. In addition, a tension between the medical profession’s healing mission and associated virtues, on the one side, and other goods, particularly remuneration, on the other, is present already in that code. This conflict is now more overt, with rampancy foreseeable in financial incentives’ express provision to intensify or reduce care and to improve doctors’ behavior without concern for whether relevant qualities (e.g., self-restraint, courage) belong to practitioners themselves.

“As Plato rightly reminds us, professional and other endeavors transpire and gain their traction from their socio-political milieu”

Though medicine’s greater pecuniary occupation is far from an isolated event, the human import of it is great. Remuneration’s increasing use to shape doctors’ behavior is harmful not just because it sends the flawed message that health and remuneration are commensurable but for what it reveals more generally about our priorities. Plato’s nuanced account of goods (agatha), which does not orbit tangible items but covers whatever may be spoken of as good, may be helpful here, particularly its addressing of where and why goods are — or aren’t — cross-categorically translatable.

Furthermore, if Plato is right that certain appetites, including that for financial gain, are by nature insatiable — as weakly susceptible to real fulfillment as the odds of filling a sieve or leaky jar are dim (Gorgias 493a-494a) — then even as we hope to make doctors more virtuous via pecuniary incentives, we may actually be promoting vice. Engagement with Plato supports our retreat from calibrated remuneration and greater devotion to sources of inspiration that occupy the same plane of good as the features of doctors we want to promote. If the goods at issue aren’t commensurable, then the core reward for right conduct and attitudes by doctors shouldn’t be monetary but something more in keeping with the tier of good reflected thereby, such as appreciative expressions visible to the community (a Platonic example is seats of honor at athletic games, Laws 881b). Of course, this directional shift shouldn’t be sprung on doctors and medical students in a vacuum. Instead, human values-education (paideia) must be devotedly and thoughtfully instilled in educational curricula from primary school on up. From this vantage point, Plato’s vision of paideia as a lifelong endeavor is worth a fresh look.

As Plato rightly reminds us, professional and other endeavors transpire and gain their traction from their socio-political milieu: we belong first to human communities, with professions’ meaning and broader purposes rooted in that milieu. The guiding values and priorities of this human setting must be transparent and vigorously discussed by professionals and non-professionals alike, whose ability to weigh in is, as the Laws suggests, far more substantive than intra-professional standpoints usually acknowledge. This same line of thought, combined with Plato’s account of universal human fallibility, bears on the matter of medicine’s continued self-policing.

Linda Emanuel claims that “professional associations — whether national, state or county, specialty, licensing, or accrediting — are the natural parties to articulate tangible standards for professional accountability. Almost by definition, there are no other entities that have such ability and extensive responsibility to be the guardians of health care values — for the medical profession and for society” (53-54). Further, accountability “procedures” may include “a moral disposition, with only an internal conscience for monitoring accountability” (54). On grounds above all of our fallibility, which is strongly operative both with and absent malice, the Laws foregrounds reciprocal oversight of all, including high officials, not just from within but across professional and sociopolitical roles; crucially, no one venue is the arbiter in all cases. Whatever the number of intra-medical umbrellas that house the profession’s oversight, transparency operates within circumscribed bounds at most, and medicine remains the source of the very standards to which practitioners — and “good” patients — will be held. Moreover, endorsing moral self-oversight here without undergirding pedagogical and aspirational structures is less likely to be effective than to hold constant or even amplify countervailing motivations.

As can be only briefly suggested here, not only the themes but also their intertwining makes further bioethical consideration of Plato vastly promising. I’m not proposing our endorsement of Plato’s account as such. Rather, some positions themselves, alongside the rich expansiveness and trajectory of his explorations, are two of Plato’s greatest legacies to us — both of which, however, have been largely untapped to date. Not only does reflection on Plato stand to enrich current bioethical debates regarding the doctor-patient tie, medical professionalism, and medicine’s societal embedment, it offers a fresh orientation to pressing debates on other bioethical topics, prominent among them high-stakes discord over the technologically-spurred project of radical human “enhancement.”

Headline image credit: Doctor Office 1. Photo by Subconsci Productions. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The post Plato and contemporary bioethics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRecurring decimals, proof, and ice floesRheumatology through the agesA spike in “compassion erosion”

Related StoriesRecurring decimals, proof, and ice floesRheumatology through the agesA spike in “compassion erosion”

October 11, 2014

Gangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the US

The spectacular arrival of thousands of unaccompanied Central American children at the southern frontier of the United States over the last three years has provoked a frenzied response. President Obama calls the situation a “humanitarian crisis” on the United States’ borders. News interviews with these vulnerable children appear almost daily in the global news media alongside official pronouncements by the US government on how it intends to stem this flow of migrants.

But what is not yet recognised is that these children represent only the tip of the iceberg of a deeper new humanitarian crisis in the region. Of course, recent figures for unaccompanied children (UAC) arriving in the US from the three countries of the Northern Triangle of Central America: El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras are alarming.

Apprehensions of unaccompanied children from these countries rose from about 3,000-4,000 per year to 10,000 in the 2012 financial year and then doubled again in the same period in 2013 to 20,000.

But it’s important to pull back and look at the bigger picture, which is that there has been a steep increase in border guard apprehensions of nationals from the three Northern Triangle countries – not just unaccompanied children, but adults and families as well.

The unaccompanied children we’ve been hearing so much about are not exceptional but represent just one strand (albeit a more photogenic and newsworthy strand) of a broader – and massive – increase in irregular migration to the US from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

If you dig a little deeper into US government data, it helps to explain why so many people are trying to get across the border any way they can. There’s been a striking rise, over the same period, in the number of people reporting that they are too scared to return to their country: from 3,000-4,000 claims from Northern Triangle nationals in previous years, the figure leaped to 8,500 for 2012 and then almost tripled to more than 23,000 in 2013.

It may be tempting to dismiss this fear of returning – “they would say that, wouldn’t they?” – but this increase is particular to the Northern Triangle and has been found increasingly by US officials to be credible – and not generally found among other asylum-seekers in the United States.

Fleeing gang violenceThis official data correlates with my ESRC-funded research in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras last year, which identified a dramatic increase in forced displacement generated by organised crime in these countries from around 2011.

As such, the timing of the increased numbers of UACs (and adults) arriving in the US corresponds closely to the explosion of people being forced from their homes by criminal violence in the Northern Triangle. The changing violent tactics of organised criminal groups are thus the principal motor driving the increased irregular migration to the US from these countries.

In all three countries, street gangs of Californian origin such as the Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 have consolidated their presence in urban locations, particularly in the poorer parts of bigger cities.

Gang violence: a member of the Mara Salvatrucha in a Honduran jail.</ br>

EPA/Stringer

In recent years these gangs have become more organised, criminal and brutal. Thus, for instance, whereas the gangs used to primarily extort only businesses, in the last few years they have begun to demand extortion monies from many local householders as well. This shift in tactics has fuelled a surge of people fleeing their homes in zones where the gangs are present.

There is variation within this bigger picture. For instance, the presence of gangs is extraordinary in El Salvador, quite extensive in the Honduras and relatively confined in Guatemala. This fact explains why, per head of population, the recent US government figures for Salvadorians claiming to fear return on arrival to the US are almost double those of Hondurans, which are almost double those of Guatemalans.

It also explains why 65% of Salvadorian UACs interviewed in the United States in 2013 mentioned gangs as their reason for leaving, as compared to 33% for Honduran UACs and 10% for Guatemalan UACs.

Worse than ColombiaWhat is not yet properly appreciated in the current debate is that these violent criminal dynamics are generating startling levels of internal displacement within these countries. If we take El Salvador as an example, we see that in 2012 some 3,300 Salvadorian children arrived in the US and 4,000 Salvadorians claimed to fear returning home.

By contrast, survey data for 2012 indicates that around 130,000 people were internally displaced within El Salvador due to criminal violence in just that one year.

The number of people seeking refuge in the United States fade in significance as against this new reality in the region.

Proportionally, 2.1% of El Salvadorians were forced to flee their homes in 2012 as a result of criminal violence and intimidation. Almost one-third of these people were displaced twice or more within the same period. If you compare this to even the worst years of gang-related violence in Colombia – the annual rate of internal displacement barely reached 1% of the population. Incredibly, the rates of forced displacement in countries such as El Salvador thus seem to surpass active war zones like Colombia.

The explosion of forced displacement caused by organised criminal groups in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras (not to mention Mexico) is the region’s true “humanitarian crisis”, of which the unaccompanied children are but one symptom.

Knee-jerk efforts by the US government to stop children arriving at its border miss this bigger picture and are doomed to failure. It would almost certainly be a better use of funds to help Central American governments to provide humanitarian support to the many uprooted families for whom survival in the resource-poor economies of the Northern Triangle is now an everyday struggle.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The post Gangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the US appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDomestic violence and the NFL. Are players at greater risk for committing the act?Falling out of love and down the housing ladder?Examining 25 years of public opinion data on gay rights and marriage

Related StoriesDomestic violence and the NFL. Are players at greater risk for committing the act?Falling out of love and down the housing ladder?Examining 25 years of public opinion data on gay rights and marriage

Recurring decimals, proof, and ice floes

Why do we teach students how to prove things we all know already, such as 0.9999••• =1?

Partly, of course, so they develop thinking skills to use on questions whose truth-status they won’t know in advance. Another part, however, concerns the dialogue nature of proof: a proof must be not only correct, but also persuasive: and persuasiveness is not objective and absolute, it’s a two-body problem. Not only to tango does one need two.

The statements — (1) ice floats on water, (2) ice is less dense than water — are widely acknowledged as facts and, usually, as interchangeable facts. But although rooted in everyday experience, they are not that experience. We have firstly represented stuffs of experience by sounds English speakers use to stand for them, then represented these sounds by word-processor symbols that, by common agreement, stand for them. Two steps away from reality already! This is what humans do: we invent symbols for perceived realities and, eventually, evolve procedures for manipulating them in ways that mirror how their real-world origins behave. Virtually no communication between two persons, and possibly not much internal dialogue within one mind, can proceed without this. Man is a symbol-using animal.

Seagull via Dreamstime, courtesy of author.

Seagull via Dreamstime, courtesy of author. Statement (1) counts as fact because folk living in cooler climates have directly observed it throughout history (and conflicting evidence is lacking). Statement (2) is factual in a significantly different sense, arising by further abstraction from (1) and from a million similar experiential observations. Partly to explain (1) and its many cousins, we have conceived ideas like mass, volume, ratio of mass to volume, and explored for generations towards the conclusion that mass-to-volume works out the same for similar materials under similar conditions, and that the comparison of mass-to-volume ratios predicts which materials will float upon others.

Statement (3): 19 is a prime number. In what sense is this a fact? Its roots are deep in direct experience: the hunter-gatherer wishing to share nineteen apples equally with his two brothers or his three sons or his five children must have discovered that he couldn’t without extending his circle of acquaintance so far that each got only one, long before he had a name for what we call ‘nineteen’. But (3) is many steps away from the experience where it is grounded. It involves conceptualisation of numerical measurements of sets one encounters, and millennia of thought to acquire symbols for these and codify procedures for manipulating them in ways that mirror how reality functions. We’ve done this so successfully that it’s easy to forget how far from the tangibles of experience they stand.

Statement (4): √2 is not exactly the ratio of two whole numbers. Most first-year mathematics students know this. But by this stage of abstraction, separating its fact-ness from its demonstration is impossible: the property of being exactly a fraction is not detectable by physical experience. It is a property of how we abstracted and systematised the numbers that proved useful in modelling reality, not of our hands-on experience of reality. The reason we regard √2’s irrationality as factual is precisely because we can give a demonstration within an accepted logical framework.

What then about recurring decimals? For persuasive argument, first ascertain the distance from reality at which the question arises: not, in this case, the rarified atmosphere of undergraduate mathematics but the primary school classroom. Once a child has learned rituals for dividing whole numbers and the convenience of decimal notation, she will try to divide, say, 2 by 3 and will hit a problem. The decimal representation of the answer does not cease to spew out digits of lesser and lesser significance no matter how long she keeps turning the handle. What should we reply when she asks whether zero point infinitely many 6s is or is not two thirds, or even — as a thoughtful child should — whether zero point infinitely many 6s is a legitimate symbol at all?

The answer must be tailored to the questioner’s needs, but the natural way forward — though it took us centuries to make it logically watertight! — is the nineteenth-century definition of sum of an infinite series. For the primary school kid it may suffice to say that, by writing down enough 6s, we’d get as close to 2/3 as we’d need for any practical purpose. For differential calculus we’d need something better, and for model-theoretic discourse involving infinitesimals something better again. Yet the underpinning mathematics for equalities like 0.6666••• = 2/3 where the question arises is the nineteenth-century one. Its fact-ness therefore resembles that of ice being less dense than water, of 19 being prime or of √2 being irrational. It can be demonstrated within a logical framework that systematises our observations of real-world experiences. So it is a fact not about reality but about the models we build to explain reality. Demonstration is the only tool available for establishing its truth.

Mathematics without proof is not like an omelette without salt and pepper; it is like an omelette without egg.

Headline image credit: Floating ice sheets in Antarctica. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Recurring decimals, proof, and ice floes appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRheumatology through the agesThe need to reform whistleblowing lawsThe Second Vatican Council and John Henry Newman

Related StoriesRheumatology through the agesThe need to reform whistleblowing lawsThe Second Vatican Council and John Henry Newman

Rheumatology through the ages

Today rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases affect more than 120 million people across Europe, but evidence shows that people have been suffering for many thousands of years. In this whistle-stop tour of rheumatology through the ages we look at how understanding and beliefs about the diseases developed.

Rheumatology is the branch of medicine dealing with the causes, pathology, diagnosis, and treatment of rheumatic disorders. In general, rheumatic disorders are those characterized by inflammation, degeneration, or metabolic derangement of the connective tissue structures of the body, especially the joints, joint capsules, tendons, bones, and muscles. There are over 150 different forms of rheumatic or musculoskeletal diseases. These conditions may be acute or chronic, and affect people of all ages and races.

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in paleopathology

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in paleopathology Palaeopathology is the study of the diseases of humans and other animals in prehistoric times, from examination of their bones or other remains.

Definition of 'rheum'

Definition of 'rheum' The term ‘rheuma’ dates back to the 1st century a.d., when it had a similar meaning to the Hippocratic term Catarrhos. Both terms refer to substances which flow, and are derived from the term phlegm, which was one of the four primary humors. The first known use in English is from the late 14th century.

Thomas Sydenham’s description of gout

Thomas Sydenham’s description of gout Thomas Sydenham, 1624–89, was an English physician who has often been called ‘the English Hippocrates’. He established the value of clinical observation in the practice of medicine and based his treatment on practical experience rather than upon the theories of Galen. He suffered from gout, of which he left a classic description and wrote frequently about it.

Famous suffers of gout

Famous suffers of gout Kings Henry VII and VIII; Queen Anne and King George IV; many of the Bourbons, Medicis, and Hapsburgs. Others said to have been affected include William Cecil, Francis Bacon, William Harvey, Oliver Cromwell, John Milton, Isaac Newton, William Pitt, Samuel Johnson, John Wesley, Horatio Nelson, Charles Darwin, Benjamin Franklin, and Martin Luther. Indeed, it is said that it was the incapacity from gout affecting William Pitt which kept him away from the English Parliament when it passed the heavy colonial duty on tea which resulted in the Boston Tea Party and the loss to England of the American colonies.

Augustin Jacob Landre-Beauvais

Augustin Jacob Landre-Beauvais The first clinical description of rheumatoid arthritis is credited to Landre-Beauvais (1880). He described a series of women with a disease he considered to be a variant of gout. The patients were nine long-term residents of the Salpêtrière hospice in Paris. After reviewing the main features of ordinary or regular gout, Landré-Beauvais points out that the disease he calls “asthenic gout” exhibits several distinctive features, including predominance in women, a chronic course, involvement of many joints from the onset, and a decline in general health.

First use of the term 'rheumatoid arthritis'

First use of the term 'rheumatoid arthritis' Sir Archibald Garrod first used the term ‘rheumatoid arthritis’ in the late 1850s, and he is Oxford English Dictionary’s first quotation for the term.

Philip Hench, awarded a Nobel prize for his work in Rheumatology

Philip Hench, awarded a Nobel prize for his work in Rheumatology Philip Showalter Hench 1896–1965, American physician won the Nobel prize in 1950 for his work developing the first steroid drug.

For many years Hench had been seeking a method of treating the crippling and painful complaint of rheumatoid arthritis. He suspected that it was not a conventional microbial infection since, among other features, it was relieved by pregnancy and jaundice. Hench therefore felt it was more likely to result from a biochemical disturbance that is transiently corrected by some incidental biological change. The search, he argued, must concentrate on something patients with jaundice had in common with pregnant women. At length he was led to suppose that the antirheumatic substance might be an adrenal hormone, since temporary remissions are often induced by procedures that stimulate the adrenal cortex. Thus in 1948 he was ready to try the newly prepared ‘compound E’, later known as cortisone, of Edward Kendall on 14 patients.

Foreward to the first edition of the journal Annals of Physical Medicine

Foreward to the first edition of the journal Annals of Physical Medicine Lord TJ Horder, in his foreword to the first edition of the Journal of the Annals of Physical Medicine, now called Rheumatology

Image credits: Brown rust paper background by cesstrelle; Public Domain via Pixabay. Texture background by Zeana; Public Domain via Pixabay. “English Caricaturists, ‘The Gout'” by James Gillray, 1893; Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Background abstract texture green; Public Domain via Pixabay. Hans Holbein the Younger; Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Portrait of Anne of Great Britain by Michael Dahl; Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Giovanni di Medici by Bronzino; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Francis Bacon, Viscount St Alban; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Oliver Cromwell Gaspard de Crayer by Caspar de Crayer; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Samuel Johnson by Joshua Reynolds; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Jwesleysitting by Frank O. Salisbury, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Horatio Nelson by Lemuel Francis Abbott; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Charles Darwin; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Benjamin Franklin 1767 by David Martin. Public domain Wikimedia Commons. Martin Luther, 1528 by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Renoir by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. J.B. Arrieu Albertini, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. James Coburn in Charade, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Lucy YankArmy cropped, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. George IV of the United Kingdom by Thomas Lawrence. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Abstract ink painting on grunge paper texture dreamy texture via Shutterstock. An anatomical illustration from the 1909 American edition of Sobotta’s Atlas and Text-book of Human Anatomy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. An anatomical illustration from the 1909 American edition of Sobotta’s Atlas and Text-book of Human Anatomy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Backdrop watercolour painting Public Domain via Pixabay. Colorful circles of light abstract background via Shutterstock.

The post Rheumatology through the ages appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesContagious disease throughout the agesThe need to reform whistleblowing lawsThe Second Vatican Council and John Henry Newman

Related StoriesContagious disease throughout the agesThe need to reform whistleblowing lawsThe Second Vatican Council and John Henry Newman

The need to reform whistleblowing laws

“Why didn’t anyone in the know say something about it?” That’s the natural reaction of the public when some shocking new scandal – financial wrongdoing, patient neglect, child abuse – comes to light. The question highlights the role of the whistleblower. He or she can play a vital role in ensuring that something is done about activity which is illegal or dangerous. But the price which the whistleblower pays may be high – ostracism by colleagues, victimisation by the employer, dismissal, informal blacklisting by other employers who fear taking on a “troublemaker”.

It is crucial that the public interest in encouraging the genuine whistleblower is fostered. The law can play an important role in promoting this aim. It ought to further the following objectives:

to provide protection for the whistleblower to ensure that he or she is given an adequate remedy if subjected to dismissal or other detriment; and to increase the prospect that something will be done to eliminate the danger and/or rectify the wrongdoing which is the subject of the disclosure.As things stand at present, our law addresses the second of those objectives – it does provide a remedy (through the employment tribunal system) for a whistleblower who is dismissed or otherwise victimised. In its recent Response to the Whistleblowing Call for Evidence , the UK government made it clear that “the whistleblowing framework is a remedy not a protection” – so objective 1 is not fulfilled by the law as it stands. It also conceded that “the framework is about addressing the workplace dispute that follows a disclosure rather than the malpractice reported by the disclosure”. So objective 3 is not part of our legal framework in any explicit way.

Project whistle. Photo by Holly Occhipinti. CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr

Project whistle. Photo by Holly Occhipinti. CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr On the government’s own analysis, then, the current legal framework on whistleblowing is not fit for purpose. One would expect this frank confession to be followed by a pledge to take action. In particular, what can be done about dealing with the danger and/or wrongdoing which the whistleblower has exposed?

The Call for Evidence and the debate which surrounded it certainly came up with various proposals. Primarily these focused on the role of the regulator. In statutory terms, the various regulators for everything from financial wrongdoing to patient neglect are known as “prescribed persons”, and are listed in statutory instruments promulgated from time to time. The whistleblower is entitled to make disclosures to such “prescribed persons” if they are reasonably believed to be true, and the prescribed person is one who is stated by the statutory instrument to be relevant in relation to the matters disclosed.

It follows that these regulators (such as the Financial Conduct Authority, the Environment Agency, the Health and Safety Executive, the Children’s Commissioner, and the Care Quality Commission to name a few random examples) could play an incredibly important role in furthering objective 3 above.

Prominent among the proposals for reform were those put forward by a prestigious commission set up by the charity Public Concern at Work. It made a number of suggestions across the board. But particularly material to the role of the regulator were the following:

regulators should require the organisations for which they are responsible to have effective whistleblowing arrangements in place they should review the licence of those organisations which do not have such arrangements a statutory Code of Practice for employers would provide the template for determining whether such arrangements were effective or not the regulators should provide feedback to whistleblowers, or explain why it is not possible to do so the current system of referral of employment tribunal claim forms should be strengthened to make referral mandatory unless the claimant opted out.The only legislative response from the government has been that contained in clause 135 of the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Bill 2014 . It gives the Secretary of State power make regulations to require a regulator to produce an annual report on whistleblowing. The regulations would set out the matters to be covered, but not in a form which would enable identification of either the whistleblower or their employer. They would set out requirements for publication e.g. by way of a report to the Secretary of State or on a website.

So far so good, and the proposed clause mirrors one of the suggestions emerging from the Public Concern at Work commission. Standing by itself, however, it is a totally inadequate response.

The crucial point is: what action will the regulators take in order to further the public interest? It is their role “to increase the prospect that something will be done to eliminate the danger and/or rectify the wrongdoing which is the subject of the disclosure”, as the government put it in its Response to the Call for Evidence. The proposals set out by the Public Concern at Work commission, or something very like them, are crucial if we are to hear the question “Why didn’t anyone in the know say something about it?” less frequently in future.

The post The need to reform whistleblowing laws appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDefinitions and dividing lines in the Employment Tribunals Rules of ProcedureThe Second Vatican Council and John Henry NewmanThe history of Christian art and architecture

Related StoriesDefinitions and dividing lines in the Employment Tribunals Rules of ProcedureThe Second Vatican Council and John Henry NewmanThe history of Christian art and architecture

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers