Oxford University Press's Blog, page 749

October 20, 2014

Place of the Year 2014: behind the longlist

Voting for the 2014 Atlas Place of the Year is now underway. However, you still be curious about the nominees. What makes them so special? Each year, we put the spotlight on the top locations in the world that make us go, “wow”. For good or for bad, this year’s longlist is quite the round-up.

Just hover over the place-markers on the map to learn a bit more about this year’s nominations.

Make sure to vote for your Place of the Year below. If you have another Place of the Year that you would like to nominate, we’d love to know about it in the comments section. Follow along with #POTY2014 until our announcement on 1 December.What do you think Place of the Year 2014 should be?

Make sure to vote for your Place of the Year below. If you have another Place of the Year that you would like to nominate, we’d love to know about it in the comments section. Follow along with #POTY2014 until our announcement on 1 December.What do you think Place of the Year 2014 should be?

Image Credits: Ferguson: “Cops Kill Kids”. Photo by Shawn Semmler. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. Liberia: Ebola Virus Particles. Photo by NIAID. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. Ukraine: Euromaiden in Kiev 2014-02-19 10-22. Photo by Amakuha. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Colorado: Grow House 105. Photo by Coleen Whitfield. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. Nauru: In front of the Menen. Photo by Sean Kelleher. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. Sochi: Olympic Park Flags (2). Photo by american_rugbler. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. Mount Sinjar: Sinjar Karst. Photo by Cpl. Dean Davis. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Gaza: The home of the Kware family after it was bombed by the military. Photo by B’Tselem. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Scotland: Vandalised no thanks sign. Photo by kay roxby. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. Brazil: World Cup stuff, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (15). Photo by Jorge in Brazil. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Heading image: Old Globe by Petar Milošević. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Place of the Year 2014: behind the longlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnouncing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pickCountries of the World Cup: NetherlandsCountries of the World Cup: Argentina

Related StoriesAnnouncing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pickCountries of the World Cup: NetherlandsCountries of the World Cup: Argentina

Race, sex, and colonialism

As an Africanist historian committed to reaching broader publics, I was thrilled when the research team for the BBC’s genealogy program Who Do You Think You Are? contacted me late last February about an episode they were working on that involved the subject of some of my research, mixed race relationships in colonial Ghana. I was even more pleased when I realized that their questions about shifting practices and perceptions of intimate relationships between African women and European men in the Gold Coast, as Ghana was then known, were ones I had just explored in a newly published American Historical Review article, which I readily shared with them. This led to a month-long series of lengthy email exchanges, phone conversations, Skype chats, and eventually to an invitation to come to Ghana to shoot the Who Do You Think You Are? episode.

After landing in Ghana in early April, I quickly set off for the coastal town of Sekondi where I met the production team, and the episode’s subject, Reggie Yates, a remarkable young British DJ, actor, and television presenter. Reggie had come to Ghana to find out more about his West African roots, but he discovered along the way that his great grandfather was a British mining accountant who worked in the Gold Coast for close to a decade. His great grandmother, Dorothy Lloyd, was a mixed-race Fante woman whose father — Reggie’s great-great grandfather — was rumored to be a British district commissioner at the turn of the century in the Gold Coast.

The episode explores the nature of the relationship between Dorothy and George, who were married by customary law around 1915 in the mining town of Broomassi, where George worked as the paymaster at the local mine. George and Dorothy set up house in Broomassi and raised their infant son, Harry, there for two years before George left the Gold Coast in 1917 for good. Although their marriage was relatively short lived, it appears that Dorothy’s family and the wider community that she lived in regarded it as a respectable union and no social stigma was attached to her or Harry after George’s departure from the coast.

George and Dorothy lived openly as man and wife in Broomassi during a time period in which publicly recognized intermarriages were almost unheard of. As a privately employed European, George was not bound by the colonial government’s directives against cohabitation between British officers and local women, but he certainly would have been aware of the informal codes of conduct that regulated colonial life. While it was an open secret that white men “kept” local women, these relationships were not to be publicly legitimated.

Precisely because George and Dorothy’s union challenged the racial prescripts of colonial life, it did not resemble the increasingly strident characterizations of interracial relationships as immoral and insalubrious that frequently appeared in the African-owned Gold Coast press during these years. Although not a perfect union, as George was already married to an English woman who lived in London with their children, the trajectory of their relationship suggests that George and Dorothy had a meaningful relationship while they were together, that they provided their son Harry with a loving home, and that they were recognized as a respectable married couple. The latter helps to account for why Dorothy was able to “marry well” after George left. Her marriage to Frank Vardon, a prominent Gold Coaster, would have been unlikely had she been regarded as nothing more than a discarded “whiteman’s toy,” as one Gold Coast writer mockingly called local women who casually liaised with European men. In her own right, Dorothy became an important figure in the Sekondi community where she ultimately settled and raised her son Harry, alongside the children she had with Frank Vardon.

The “white peril” commentaries that I explored in my American Historical Review article proved to be a rhetorically powerful strategy for challenging the moral legitimacy of British colonial rule because they pointed to the gap between the civilizing mission’s moral rhetoric and the sexual immorality of white men in the colony. But rhetoric often sacrifices nuance for argumentative force and Gold Coasters’ “white peril” commentaries were no exception. Left out of view were men like George Yates, who challenged the conventions of their times, albeit imperfectly, and women like Dorothy Lloyd who were not cast out of “respectable” society, but rather took their place in it.

This sense of conflict and connection and of categorical uncertainty surrounding these relationships is what I hope to have contributed to the research process, storyline development, and filming of the Reggie Yates episode of Who Do You Think You Are? The central question the show raises is how do we think about and define relationships that were so heavily circumscribed by racialized power without denying the “possibility of love?” By “endeavor[ing] to trace its imperfections, its perversions,” was Martinican philosopher and anticolonial revolutionary Frantz Fanon’s answer. His insight surely reverberates throughout the episode.

All images courtesy of Carina Ray.

The post Race, sex, and colonialism appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNeurology and psychiatry in BabylonPolitical Analysis Letters: a new way to publish innovative researchRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

Related StoriesNeurology and psychiatry in BabylonPolitical Analysis Letters: a new way to publish innovative researchRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

Preparing for the International Law Weekend 2014

The 2014 International Law Weekend Annual Meeting is taking place this month at Fordham Law School, in New York City (24-25 October 2014).

The theme of this year’s meeting is “International Law in a Time of Chaos”, exploring the role of international law in conflict mitigation. Panel discussions will examine various aspects of both public international law and private international law, including trade, investment, arbitration, intellectual property, combatting corruption, labor standards in the global supply chain, and human rights, as well as issues of international organizations and international security.

ILW is sponsored and organized by the American Branch of the International Law Association (ABILA) and the International Law Students Association (ILSA). Every year more than one thousand practitioners, academics, diplomats, members of the governmental and nongovernmental sectors, and students attend this conference.

This year’s conference highlights include:

This year’s keynote from Lori Damrosch, Hamilton Fish Professor of International Law and Diplomacy, Columbia Law School, and President of the American Society of International Law. “Democratization of Foreign Policy and International Law, 1914-2014” Friday, 1:30PM (Room 2-02A) Several talks on recent events in Crimea. (Check out our OPIL Debate Map: Ukraine Use of Force, to learn more on the subject in advance.) “European Union – Challenges or Chaos,” Friday, 9:00AM (Room 2-02A) “Update on the International Criminal Court’s Crime of Aggression: Considering Crimea,” Friday, 10:45AM (Room 2-02B) The “International Adjudication in the 21st Century” panel, including OUP author Cesare Romano, will discuss the key findings of the recently published The Oxford Handbook of International Adjudication. Friday, 9:00AM (Room 2-01B). (Read up on the topic before the event, with free content from the book.) Top practitioners in the field discuss “International Investment Arbitration and the Rule of Law”, Friday 4:45PM (Room 2-02A). (Sign up for our Free Investment Claims Webinar on October 20th to brush up on VCLT in BIT arbitrations in time for this panel.) Looking for career advice? Attend this roundtable discussion on Saturday afternoon “Careers in International Human Rights, International Development, and International Rule of Law,” Saturday, 3:30PM (Room 2-02B)This year we are excited to see a number of OUP authors sitting on panels, including: Cesare Romano, editor of The Oxford Handbook of International Adjudication (with Karen J. Alter, and Yuval Shany); Ryan Goodman, author of the ASIL award winning book Socializing States: Promoting Human Rights through International Law (with Derek Jinks); August Reinisch, editor of The Privileges and Immunities of International Organizations in Domestic Courts; Jose E. Alvarez, author of The Evolving International Investment Regime (with Karl P. Sauvant); Ruti G. Teitel, author of Globalizing Transitional Justice: Contemporary Essays; Daniel H. Joyner, author of Interpreting the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty; and Philip Alston, author of International Human Rights (with Ryan Goodman), to name a few.

For the full International Law Weekend 2014 schedule of events, visit ILSA and American Branch of the International Law Association websites.

Fordham Law School is located in the wonderful Lincoln Square neighborhood of New York and just around the corner from some great activities after the conference:

ILW Opening Reception. The wine and cheese reception at the Association of the Bar of the City of New York is open to all ILW attendees. 2nd Floor, Reception Area, ABCNY, Thursday at 8:00PM. Reception at the Permanent Mission of South Africa to the United Nations, 333 E. 38th Street., 9th Floor, New York, NY at 6:30PM (Pre-registration is required for this event) Art fans can head over to the American Folk Art Museum, open Friday 12:00 – 7:30PM, and Saturday 11:30AM – 7:00PM. Admission is free. Prefer parks and poetry? Take a stroll in Dante Park, established by Italian-Americans in honor of the Italian poet Dante Alighieri. Head over to Lincoln Center to catch a symphony, an opera, or one of the many fantastic performances. Fancy a spot of shopping? Check out The Shops at Columbus Circle.Of course, we hope to see you at Oxford University Press booth. We’ll be offering the chance to browse and buy our new and bestselling titles on display at a 20% conference discount, discover what’s new in Oxford Law Online, and pick up sample copies of our latest law journals.

To follow the latest updates about the ILW Conference as it happens, follow us on Twitter at @OUPIntLaw and the hashtag #ILW2014.

See you in there!

Headline image credit: 2011, 62nd St by Cornerstones of New York, CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Preparing for the International Law Weekend 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive key moments in the Open Access movement in the last ten yearsNeurology and psychiatry in Babylon2014 AES Convention: shrinking opportunities in music audio

Related StoriesFive key moments in the Open Access movement in the last ten yearsNeurology and psychiatry in Babylon2014 AES Convention: shrinking opportunities in music audio

Neurology and psychiatry in Babylon

How rapidly does medical knowledge advance? Very quickly if you read modern newspapers, but rather slowly if you study history. Nowhere is this more true than in the fields of neurology and psychiatry.

It was believed that studies of common disorders of the nervous system began with Greco-Roman Medicine, for example, epilepsy, “The sacred disease” (Hippocrates) or “melancholia”, now called depression. Our studies have now revealed remarkable Babylonian descriptions of common neuropsychiatric disorders a millennium earlier.

There were several Babylonian Dynasties with their capital at Babylon on the River Euphrates. Best known is the Neo-Babylonian Dynasty (626-539 BC) associated with King Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC) and the capture of Jerusalem (586 BC). But the neuropsychiatric sources we have studied nearly all derive from the Old Babylonian Dynasty of the first half of the second millennium BC, united under King Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC).

The Babylonians made important contributions to mathematics, astronomy, law and medicine conveyed in the cuneiform script, impressed into clay tablets with reeds, the earliest form of writing which began in Mesopotamia in the late 4th millennium BC. When Babylon was absorbed into the Persian Empire cuneiform writing was replaced by Aramaic and simpler alphabetic scripts and was only revived (translated) by European scholars in the 19th century AD.

The Babylonians were remarkably acute and objective observers of medical disorders and human behaviour. In texts located in museums in London, Paris, Berlin and Istanbul we have studied surprisingly detailed accounts of what we recognise today as epilepsy, stroke, psychoses, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), psychopathic behaviour, depression and anxiety. For example they described most of the common seizure types we know today e.g. tonic clonic, absence, focal motor, etc, as well as auras, post-ictal phenomena, provocative factors (such as sleep or emotion) and even a comprehensive account of schizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy.

Epilepsy Tablet and the Dying Lioness, reproduced with kind permission of The British Museum.

Epilepsy Tablet and the Dying Lioness, reproduced with kind permission of The British Museum. Early attempts at prognosis included a recognition that numerous seizures in one day (i.e. status epilepticus) could lead to death. They recognised the unilateral nature of stroke involving limbs, face, speech and consciousness, and distinguished the facial weakness of stroke from the isolated facial paralysis we call Bell’s palsy. The modern psychiatrist will recognise an accurate description of an agitated depression, with biological features including insomnia, anorexia, weakness, impaired concentration and memory. The obsessive behaviour described by the Babylonians included such modern categories as contamination, orderliness of objects, aggression, sex, and religion. Accounts of psychopathic behaviour include the liar, the thief, the troublemaker, the sexual offender, the immature delinquent and social misfit, the violent, and the murderer.

The Babylonians had only a superficial knowledge of anatomy and no knowledge of brain, spinal cord or psychological function. They had no systematic classifications of their own and would not have understood our modern diagnostic categories. Some neuropsychiatric disorders e.g. stroke or facial palsy had a physical basis requiring the attention of the physician or asû, using a plant and mineral based pharmacology. Most disorders, such as epilepsy, psychoses and depression were regarded as supernatural due to evil demons and spirits, or the anger of personal gods, and thus required the intervention of the priest or ašipu. Other disorders, such as OCD, phobias and psychopathic behaviour were viewed as a mystery, yet to be resolved, revealing a surprisingly open-minded approach.

From the perspective of a modern neurologist or psychiatrist these ancient descriptions of neuropsychiatric phenomenology suggest that the Babylonians were observing many of the common neurological and psychiatric disorders that we recognise today. There is nothing comparable in the ancient Egyptian medical writings and the Babylonians therefore were the first to describe the clinical foundations of modern neurology and psychiatry.

A major and intriguing omission from these entirely objective Babylonian descriptions of neuropsychiatric disorders is the absence of any account of subjective thoughts or feelings, such as obsessional thoughts or ruminations in OCD, or suicidal thoughts or sadness in depression. The latter subjective phenomena only became a relatively modern field of description and enquiry in the 17th and 18th centuries AD. This raises interesting questions about the possibly slow evolution of human self awareness, which is central to the concept of “mental illness”, which only became the province of a professional medical discipline, i.e. psychiatry, in the last 200 years.

The post Neurology and psychiatry in Babylon appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBiologists that changed the worldGoing inside to get a taste of natureCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014

Related StoriesBiologists that changed the worldGoing inside to get a taste of natureCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014

October 19, 2014

Five key moments in the Open Access movement in the last ten years

In 2014 Oxford University Press celebrates ten years of open access (OA) publishing. In that time open access has grown massively as a movement and an industry. Here we look back at five key moments which have marked that growth.

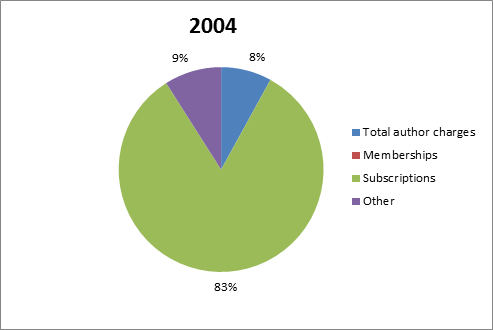

2004/05 – Nucleic Acids Research (NAR) converts to OAAt first glance it might seem parochial to include this here, but as Rich Roberts noted on this blog in 2012, Nucleic Acids Research’s move to open access was truly ‘momentous’. To put it in context, in 2004 NAR was OUP’s biggest owned journal and it was not at all clear that many of the elements were in place to drive the growth of OA. But in 2004/2005 NAR moved from being free to publish to free to read – with authors now supporting the journal financially by paying APCs (Article Processing Charges). No wonder Roberts adds that it was ‘with great trepidation’ that OUP and the editors made the change. Roberts needn’t have worried — NAR’s switch has been a huge success — its impact factor has increased, and submissions, which could have fallen off a cliff, have continued to climb. As with anything, there are elements of the NAR model which couldn’t be replicated now, but NAR helped show the publishing world in particular that OA could work. It’s saying something that it’s only ten years on, with the transition of Nature Communications to OA, that any journal near NAR’s size has made the switch.

NAR Revenue Streams 2004

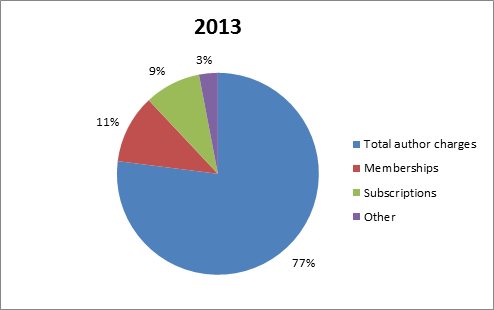

NAR Revenue Streams 2004  NAR Revenue Streams 2013 2008 – National Institutes of Health (NIH) Mandate Introduced

NAR Revenue Streams 2013 2008 – National Institutes of Health (NIH) Mandate Introduced Open access presents huge opportunities for research funders; the removal of barriers to access chimes perfectly with most funders’ aim to disseminate the fruits of their research as widely as possible. But as both the NIH and Wellcome, amongst others, have found out, author interests don’t always chime exactly with theirs. Authors have other pressures to consider – primarily career development – and that means publishing in the best journal, the journal with the highest impact factor, etc. and not necessarily the one with the best open access options. So it was that in 2008 the NIH found it was getting a very low rate of compliance with its recommended OA requirements for authors. What happened next was hugely significant for the progress of open access. As part of an Act which passed through the US legislature, it was made mandatory for all NIH-funded authors to make their works available 12 months after publication. This was transformative in two ways: it meant thousands of articles published from NIH research became available through PubMed Central (PMC), and perhaps just as importantly it legitimised government intervention in OA policy, setting a precedent for future developments in Europe and the United Kingdom.

2008 – Springer buys BioMed Central (BMC)BioMed Central was the first for-profit open access publisher – and since its inception in 2000 it was closely watched in the industry to see if it could make OA ‘work’. When it was purchased by one of the world’s largest publishers, and when that company’s CEO declared that OA was now a ‘sustainable part of STM publishing’, it was a pretty clear sign to the rest of the industry, and all OA-watchers, that the upstart business model was now proving to be more than just an interesting side line. It also reflected the big players in the industry starting to take OA very seriously, and has been followed by other acquisitions – for example Nature purchasing Frontiers in early 2013. The integration of BMC into Springer has happened gradually over the past five years, and has also been marked by a huge expansion of OA at the parent company. Springer was one of the first subscription publishers to embrace hybrid OA, in 2004, but since acquiring BMC they have also massively increased their fully OA publishing. It seems bizarre to think that back in 2008 there were even some who feared the purchase was aimed at moving all BMC’s journals back to subscription access.

2007 on – Growth of PLOS ONE The head and shoulders of Janet Finch, pictured on the platform as a guest speaker at the 11 November 2003 General Meeting of the Keele University Students’ Union. KUSU Ballroom, Keele, Staffordshire, UK. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The head and shoulders of Janet Finch, pictured on the platform as a guest speaker at the 11 November 2003 General Meeting of the Keele University Students’ Union. KUSU Ballroom, Keele, Staffordshire, UK. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. The Public Library of Science (PLOS) started publishing open access journals back in 2003, but while its journals quickly developed a reputation for high-quality publishing, the not-for-profit struggled to succeed financially. The advent of PLOS ONE changed all that. PLOS ONE has been transformative for several reasons, most notably its method of peer review. Typically top journals have tended to have their niche, and be selective. A journal on carcinogens would be unlikely to accept a paper about molecular biology, and it would only accept a paper on carcinogens if it was seen to be sufficiently novel and interesting. PLOS ONE changed that. It covers every scientific field, and its peer review is methodological (i.e. is the basic science sound) rather than looking for anything else. This enabled PLOS ONE to rapidly turn into the biggest journal in the world, publishing a staggering 31,500 papers in 2013 alone. PLOS ONE’s success cannot be solely attributed to its OA nature, but it was being OA which enabled PLOS ONE to become the ‘megajournal’ we know today. It would simply not be possible to bring such scale to a subscription journal. The price would balloon beyond the reach of even the biggest library budget. PLOS ONE has spawned a rash of similar journals and more than any one title it has energised the development of OA, dispelling previously-held notions of what could and couldn’t be done in journals publishing.

2012 – The ‘Finch’ ReportIt’s difficult to sum up the vast impact of the Finch Report on journals publishing in the UK. The product of a group chaired by the eponymous Dame Janet Finch, the report, by way of two government investigations, catalysed a massive investment in gold open access (funded by APCs) from the UK government, crystallised by Research Councils UK’s OA policy. In setting the direction clearly towards gold OA, ‘Finch’ led to a huge number of journals changing their policies to accommodate UK researchers, and the establishment of OA policies, departments, and infrastructure at academic institutions and publishers across the UK and beyond. The wide-ranging policy implications of ‘Finch’ continue to be felt as time progresses, through 2014’s Higher Education Funding Council (HEFCE) for England policy, through research into the feasibility of OA monographs, and through deliberations in other jurisdictions over whether to follow the UK route to open access. HEFCE’s OA mandate in particular will prove incredibly influential for UK researchers – as it directly ties the assessment of a university’s funding to their success in ensuring their authors publish OA. The mainstream media attention paid to ‘Finch’ also brought OA publishing into the public eye in a way never seen before (or since).

Headline image credit: Storm of Stars in the Trifid Nebula. NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA

The post Five key moments in the Open Access movement in the last ten years appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs American higher education in crisis?2014 AES Convention: shrinking opportunities in music audioPolitical Analysis Letters: a new way to publish innovative research

Related StoriesIs American higher education in crisis?2014 AES Convention: shrinking opportunities in music audioPolitical Analysis Letters: a new way to publish innovative research

2014 AES Convention: shrinking opportunities in music audio

Checking the website for the Audio Engineering Society (AES) convention in Los Angeles, I took note of the swipes promoting the event. Each heading was framed as follows: If it’s about ____________, it’s at AES. The slide show contained nine headings that are to be a part of the upcoming convention (in no particular order because you start at whatever point in the slide show you happened to log-in to the site).

Archiving & Restoration

Networked Audio

Broadcast & Streaming

Product Design

Recording

Project Studios

Sound for Picture

Live Sound

Game Sound

The list was interesting to me on many levels, but one significant one that struck me immediately was the absence of mixing and mastering (my main areas of work in audio). A relatively short time ago almost half of these categories did not exist. There was no streaming, no project studios, no networked audio and no game sound. So what is the state of affairs for the young audio engineering student or practitioner?

Yamaha M7CL digital live sound mixing console left half angled. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

Yamaha M7CL digital live sound mixing console left half angled. CC0 via Wikimedia CommonsInterestingly, of the four new fields mentioned, three of them represent diminished opportunities in the field of music recording, with one a singular beacon of hope.

Streaming audio represents the brave new world of audio delivery systems. As these services continue to capture more of the consumer market share they continue to diminish artists ability to earn a decent living (or pay an accomplished audio engineer). A friend of mine with 3 CD releases recently got his Spotify statement and saw that he had more that 60,000 streams of his music. His check was for $17. CDs don’t pay as well as vinyl records used to, downloads don’t pay as well as CDs, and streaming doesn’t pay as well as downloads (not to mention “file-sharing” which doesn’t pay anything). Sure, there may be jobs at Pandora and Spotify for a few engineers helping with the infrastructure of audio streaming, but generally streaming is another brick in the wall that is restricting audio jobs by shrinking the earning capacity of recording artists.

Project studios now dominate most recording projects outside the reasonably well-funded major label records and even most of that work is done in project studios (though they might be quite elaborate facilities). Project studios rarely have spots for interns or assistant engineers so they provide no entree positions for those trying to come up in the engineering ranks. Not only does that limit the available sources of income, but it also prevents the kind of mentoring that actually trains young engineers in the fine points of running sessions. Of course, almost no project studios provide regular, dependable work or with any kind of benefits.

Networked audio systems provide new, faster, and more elaborate connectivity of audio using digital technology. While there may be opportunities in the tech realm for engineers designing and building digital audio networks there is, once again, a shrinking of opportunities for those aspiring to making commercial music recordings. In many instances, these networking systems allow fewer people to do more—a boon only to a small number of audio engineers working with music recordings who can now do remote recordings without having to be present and without having to employ local recording engineers and studios to complete projects with musicians in other locations.

The one bright spot here is Game Sound. The explosive world of video games is providing many good jobs for audio engineers who want to record music. These recordings have become more interesting, higher quality, and featuring more prominent and talented composers and musicians than virtually any other area of music production. The only reservation here is that the music is intended as secondary to the game play (of course) and there is a preponderance of violent video games and therefore musical styles that tend to fit well into a violent atmosphere. However, this is changing with a much broader array of game types achieving new levels of popularity (Mindcraft!).

I do not fault AES for pointing to these areas of interest for audio engineers (other than the apparent absence of mixing and mastering). These are the places where significant activity, development, and change are occurring. They’re just not very encouraging for those of us who became audio engineers because of our deep love of music and our desire to be engaged in its production.

Headline Image: Sound Mixing via CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay

The post 2014 AES Convention: shrinking opportunities in music audio appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn person online: the human touchWhat is the most important issue in music education today?Political Analysis Letters: a new way to publish innovative research

Related StoriesIn person online: the human touchWhat is the most important issue in music education today?Political Analysis Letters: a new way to publish innovative research

Political Analysis Letters: a new way to publish innovative research

There’s a lot of interesting social science research these days. Conference programs are packed, journals are flooded with submissions, and authors are looking for innovative new ways to publish their work.

This is why we have started up a new type of research publication at Political Analysis, Letters.

Research journals have a limited number of pages, and many authors struggle to fit their research into the “usual formula” for a social science submission — 25 to 30 double-spaced pages, a small handful of tables and figures, and a page or two of references. Many, and some say most, papers published in social science could be much shorter than that “usual formula.”

We have begun to accept Letters submissions, and we anticipate publishing our first Letters in Volume 24 of Political Analysis. We will continue to accept submissions for research articles, though in some cases the editors will suggest that an author edit their manuscript and resubmit it as a Letter. Soon we will have detailed instructions on how to submit a Letter, the expectations for Letters, and other information, on the journal’s website.

We have named Justin Grimmer and Jens Hainmueller, both at Stanford University, to serve as Associate Editors of Political Analysis — with their primary responsibility being Letters. Justin and Jens are accomplished political scientists and methodologists, and we are quite happy that they have agreed to join the Political Analysis team. Justin and Jens have already put in a great deal of work helping us develop the concept, and working out the logistics for how we integrate the Letters submissions into the existing workflow of the journal.

I recently asked Justin and Jens a few quick questions about Letters, to give them an opportunity to get the word out about this new and innovative way of publishing research in Political Analysis.

Political Analysis is now accepting the submission of Letters as well as Research Articles. What are the general requirements for a Letter?

Letters are short reports of original research that move the field forward. This includes, but is not limited to, new empirical findings, methodological advances, theoretical arguments, as well as comments on or extensions of previous work. Letters are peer reviewed and subjected to the same standards as Political Analysis research articles. Accepted Letters are published in the electronic and print versions of Political Analysis and are searchable and citable just like other articles in the journal. Letters should focus on a single idea and are brief—only 2-4 pages and no longer than 1500-3000 words.

Why is Political Analysis taking this new direction, looking for shorter submissions?

Political Analysis is taking this new direction to publish important results that do not traditionally fit in the longer format of journal articles that are currently the standard in the social sciences, but fit well with the shorter format that is often used in the sciences to convey important new findings. In this regard the role model for the Political Analysis Letters are the similar formats used in top general interest science journals like Science, Nature, or PNAS where significant findings are often reported in short reports and articles. Our hope is that these shorter papers also facilitate an ongoing and faster paced dialogue about research findings in the social sciences.

What is the main difference between a Letter and a Research Paper?

The most obvious difference is the length and focus. Letters are intended to only be 2-4 pages, while a standard research article might be 30 pages. The difference in length means that Letters are going to be much more focused on one important result. A letter won’t have the long literature review that is standard in political science articles and will have much more brief introduction, conclusion, and motivation. This does not mean that the motivation is unimportant; it just means that the motivation has to briefly and clearly convey the general relevance of the work and how it moves the field forward. A Letter will typically have 1-3 small display items (figures, tables, or equations) that convey the main results and these have to be well crafted to clearly communicate the main takeaways from the research.

If you had to give advice to an author considering whether to submit their work to Political Analysis as a Letter or a Research Article, what would you say?

Our first piece of advice would be to submit your work! We’re open to working with authors to help them craft their existing research into a format appropriate for letters. As scholars are thinking about their work, they should know that Letters have a very high standard. We are looking for important findings that are well substantiated and motivated. We also encourage authors to think hard about how they design their display items to clearly convey the key message of the Letter. Lastly, authors should be aware that a significant fraction of submissions might be desk rejected to minimize the burden on reviewers.

You both are Associate Editors of Political Analysis, and you are editing the Letters. Why did you decide to take on this professional responsibility?

Letters provides us an opportunity to create an outlet for important work in Political Methodology. It also gives us the opportunity to develop a new format that we hope will enhance the quality and speed of the academic debates in the social sciences.

Headline image credit: Letters, CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Political Analysis Letters: a new way to publish innovative research appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the USThe pros and cons of research preregistrationBiologists that changed the world

Related StoriesGangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the USThe pros and cons of research preregistrationBiologists that changed the world

Linguistic necromancy: a guide for the uninitiated

It’s fairly common knowledge that languages, like people, have families. English, for instance, is a member of the Germanic family, with sister languages including Dutch, German, and the Scandinavian languages. Germanic, in turn, is a branch of a larger family, Indo-European, whose other members include the Romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish, and more), Russian, Greek, and Persian.

Being part of a family of course means that you share a common ancestor. For the Romance languages, that mother language is Latin; with the spread and then fall of the Roman empire, Latin split into a number of distinct daughter languages. But what did the Germanic mother language look like? Here there’s a problem, because, although we know that language must have existed, we don’t have any direct record of it.

The earliest Old English written texts date from the 7th century AD, and the earliest Germanic text of any length is a 4th-century translation of the Bible into Gothic, a now-extinct Germanic language. Though impressively old, this text still dates from long after the breakup of the Germanic mother language into its daughters.

How does one go about recovering the features of a language that is dead and gone, and which has left no records of itself in spoken or written form? This is the subject matter of linguistic necromancy – or linguistic reconstruction, as it is more conventionally known.

The enterprise, dubbed “darkest of the dark arts” and “the only means to conjure up the ghosts of vanished centuries” in the epigraph to a chapter of Campbell’s historical linguistics textbook, really got off the ground in the 1900s due to a development of a toolkit of techniques known as the comparative method.

Crucial to the comparative method was a revolutionary empirical finding: the regularity of sound change. Though it has wide-reaching implications, the basic finding is simple to grasp. In a nutshell: it’s sounds that change, not words, and when they change, all words which include those sounds are affected.

Detail of a page from the Codex Argenteus. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Detail of a page from the Codex Argenteus. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Let’s take an example. Lots of English words beginning with a p sound have a German counterpart that begins with pf. Here are some of them:

English p ath: German Pf ad

English p epper: German Pf effer

English p ipe: German Pf eife

English p an: German Pf anne

English p ost: German Pf oste

If the forms of words simply changed at random, these systematic correspondences would be a miraculous coincidence. However, in the light of the regularity of sound change they make perfect sense. Specifically, at some point in the early history of German, the language sounded a lot more like (Old) English. But then the sound p underwent a change to pf at the beginning of words, and all words starting with p were affected.

There’s much more to be said about the regularity of sound change, since it underlies pretty much everything we know about language family groupings. (If you’re interested in finding out more, Guy Deutscher’s book The Unfolding of Language provides an accessible summary.) But for now let’s concentrate on its implications for necromantic purposes, which are immense.

If we want to invoke the words and sounds of a long-dead language like the mother language Proto-Germanic (the ‘proto-’ indicates that the language is reconstructed, rather than directly evidenced in texts), we just need to figure out what changes have happened to the sounds of the daughter languages, and to peel them back one by one like the layers of an onion. Eventually we’ll reach a point where all the daughter languages sound the same; and voilà, we’ve conjured up a proto-language.

There’s more to living languages than just sounds and words though. Living languages have syntax: a structure, a skeleton. By contrast, reconstructed protolanguages tend to look more like ghosts: hauntingly amorphous clouds of words and sounds. There are practical reasons why the reconstruction of proto-syntax has lagged behind. One is simply that our understanding of syntax, in general, has come a long way since the work of the reconstruction pioneers in the 19th century.

Another is that there is nothing quite like the regularity of syntactic change in syntax: how can we tell which syntactic structures correspond to each other across languages? These problems have led some to be sceptical about the possibility of syntactic reconstruction, or at any rate about its fruitfulness. Nevertheless, progress is being made. To take one example, English is a language that doesn’t like to leave out the subject of a sentence. We say “He speaks Swahili” or “It is raining”, not “Speaks Swahili” or “Is raining”. Though most of the modern Germanic languages behave the same, many other languages, like Italian and Japanese, have no such requirement; speakers can include or omit the subject of the sentence as the fancy takes them. Was Proto-Germanic like English, or like Italian or Japanese, in this respect? Doing a bit of necromancy based on the earliest Germanic written records suggests that Proto-Germanic was, like the latter, quite happy to omit the subject, at least under certain circumstances.Of course the issue is more complex than that – Italian and Japanese themselves differ with regard to the circumstances under which subjects can be omitted.

Slowly but surely, though, historical linguists are starting to add skeletons to the reanimated spectres of proto-languages.

The post Linguistic necromancy: a guide for the uninitiated appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe role of grammar for the teaching of LatinFacebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronounsFrom “Checkers” to Watergate

Related StoriesThe role of grammar for the teaching of LatinFacebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronounsFrom “Checkers” to Watergate

Efficient causation: Our debt to Aristotle and Hume

Causation is now commonly supposed to involve a succession that instantiates some lawlike regularity. This understanding of causality has a history that includes various interrelated conceptions of efficient causation that date from ancient Greek philosophy and that extend to discussions of causation in contemporary metaphysics and philosophy of science. Yet the fact that we now often speak only of causation, as opposed to efficient causation, serves to highlight the distance of our thought on this issue from its ancient origins. In particular, Aristotle (384-322 BCE) introduced four different kinds of “cause” (aitia): material, formal, efficient, and final. We can illustrate this distinction in terms of the generation of living organisms, which for Aristotle was a particularly important case of natural causation. In terms of Aristotle’s (outdated) account of the generation of higher animals, for instance, the matter of the menstrual flow of the mother serves as the material cause, the specially disposed matter from which the organism is formed, whereas the father (working through his semen) is the efficient cause that actually produces the effect. In contrast, the formal cause is the internal principle that drives the growth of the fetus, and the final cause is the healthy adult animal, the end point toward which the natural process of growth is directed.

Aristotle, by Raphael Sanzio. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Aristotle, by Raphael Sanzio. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.From a contemporary perspective, it would seem that in this case only the contribution of the father (or perhaps his act of procreation) is a “true” cause. Somewhere along the road that leads from Aristotle to our own time, material, formal and final aitiai were lost, leaving behind only something like efficient aitiai to serve as the central element in our causal explanations. One reason for this transformation is that the historical journey from Aristotle to us passes by way of David Hume (1711-1776). For it is Hume who wrote: “[A]ll causes are of the same kind, and that in particular there is no foundation for that distinction, which we sometimes make betwixt efficient causes, and formal, and material … and final causes” (Treatise of Human Nature, I.iii.14). The one type of cause that remains in Hume serves to explain the producing of the effect, and thus is most similar to Aristotle’s efficient cause. And so, for the most part, it is today.

However, there is a further feature of Hume’s account of causation that has profoundly shaped our current conversation regarding causation. I have in mind his claim that the interrelated notions of cause, force and power are reducible to more basic non-causal notions. In Hume’s case, the causal notions (or our beliefs concerning such notions) are to be understood in terms of the constant conjunction of objects or events, on the one hand, and the mental expectation that an effect will follow from its cause, on the other. This specific account differs from more recent attempts to reduce causality to, for instance, regularity or counterfactual/probabilistic dependence. Hume himself arguably focused more on our beliefs concerning causation (thus the parenthetical above) than, as is more common today, directly on the metaphysical nature of causal relations. Nonetheless, these attempts remain “Humean” insofar as they are guided by the assumption that an analysis of causation must reduce it to non-causal terms. This is reflected, for instance, in the version of “Humean supervenience” in the work of the late David Lewis. According to Lewis’s own guarded statement of this view: “The world has its laws of nature, its chances and causal relationships; and yet — perhaps! — all there is to the world is its point-by-point distribution of local qualitative character” (On the Plurality of Worlds, 14).

Portrait of David Hume, by Allan Ramsey (1766). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of David Hume, by Allan Ramsey (1766). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Admittedly, Lewis’s particular version of Humean supervenience has some distinctively non-Humean elements. Specifically — and notoriously — Lewis has offered a counterfactural analysis of causation that invokes “modal realism,” that is, the thesis that the actual world is just one of a plurality of concrete possible worlds that are spatio-temporally discontinuous. One can imagine that Hume would have said of this thesis what he said of Malebranche’s occasionalist conclusion that God is the only true cause, namely: “We are got into fairy land, long ere we have reached the last steps of our theory; and there we have no reason to trust our common methods of argument, or to think that our usual analogies and probabilities have any authority” (Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, §VII.1). Yet the basic Humean thesis in Lewis remains, namely, that causal relations must be understood in terms of something more basic.

And it is at this point that Aristotle re-enters the contemporary conversation. For there has been a broadly Aristotelian move recently to re-introduce powers, along with capacities, dispositions, tendencies and propensities, at the ground level, as metaphysically basic features of the world. The new slogan is: “Out with Hume, in with Aristotle.” (I borrow the slogan from Troy Cross’s online review of Powers and Capacities in Philosophy: The New Aristotelianism.) Whereas for contemporary Humeans causal powers are to be understood in terms of regularities or non-causal dependencies, proponents of the new Aristotelian metaphysics of powers insist that regularities and dependencies must be understood rather in terms of causal powers.

Should we be Humean or Aristotelian with respect to the question of whether causal powers are basic or reducible features of the world? Obviously I cannot offer any decisive answer to this question here. But the very fact that the question remains relevant indicates the extent of our historical and philosophical debt to Aristotle and Hume.

Headline image: Face to face. Photo by Eugenio. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr

The post Efficient causation: Our debt to Aristotle and Hume appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 3Is American higher education in crisis?Illuminating the drama of DNA: creating a stage for inquiry

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 3Is American higher education in crisis?Illuminating the drama of DNA: creating a stage for inquiry

October 18, 2014

Is American higher education in crisis?

American higher education is at a crossroads. The cost of a college education has made people question the benefits of receiving one. To better understand the issues surrounding the supposed crisis, we asked Goldie Blumenstyk, author of American Higher Education in Crisis: What Everyone Needs to Know, to comment on some of the most hot button topics today.

A discussion on the rising cost of higher education.

What does the future of higher education look like?

Are the salaries of university presidents and coaches too high?

A look into the accountability movement in higher education today.

Featured image credit: Grads with diplomas by Saint Louis University Plus Memorial Library. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Is American higher education in crisis? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTrue or False: facts and myths on American higher educationHow threatened are we by Ebola virus?Limiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemic

Related StoriesTrue or False: facts and myths on American higher educationHow threatened are we by Ebola virus?Limiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemic

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers