Oxford University Press's Blog, page 750

October 18, 2014

Illuminating the drama of DNA: creating a stage for inquiry

Many bioethical challenges surround the promise of genomic technology and the power of genomic information — providing a rich context for critically exploring underlying bioethical traditions and foundations, as well as the practice of multidisciplinary advisory committees and collaborations. Controversial issues abound that call into question the core values and assumptions inherent in bioethics analysis and thus necessitates interprofessional inquiry. Consequently, the teaching of genomics and contemporary bioethics provides an opportunity to re-examine our disciplines’ underpinnings by casting light on the implications of genomics with novel approaches to address thorny issues — such as determining whether, what, to whom, when, and how genomic information, including “incidental” findings, should be discovered and disclosed to individuals and their families, and whose voice matters in making these determinations particularly when children are involved.

One creative approach we developed is narrative genomics using drama with provocative characters and dialogue as an interdisciplinary pedagogical approach to bring to life the diverse voices, varied contexts, and complex processes that encompass the nascent field of genomics as it evolves from research to clinical practice. This creative educational technique focuses on inherent challenges currently posed by the comprehensive interrogation and analysis of DNA through sequencing the human genome with next generation technologies and illuminates bioethical issues, providing a stage to reflect on the controversies together, and temper the sometimes contentious debates that ensue.

As a bioethics teaching method, narrative genomics highlights the breadth of individuals affected by next-gen technologies — the conversations among professionals and families — bringing to life the spectrum of emotions and challenges that envelope genomics. Recent controversies over genomic sequencing in children and consent issues have brought fundamental ethical theses to the stage to be re-examined, further fueling our belief in drama as an interdisciplinary pedagogical approach to explore how society evaluates, processes, and shares genomic information that may implicate future generations. With a mutual interest in enhancing dialogue and understanding about the multi-faceted implications raised by generating and sharing vast amounts of genomic information, and with diverse backgrounds in bioethics, policy, psychology, genetics, law, health humanities, and neuroscience, we have been collaboratively weaving dramatic narratives to enhance the bioethics educational experience within varied professional contexts and a wide range of academic levels to foster interprofessionalism.

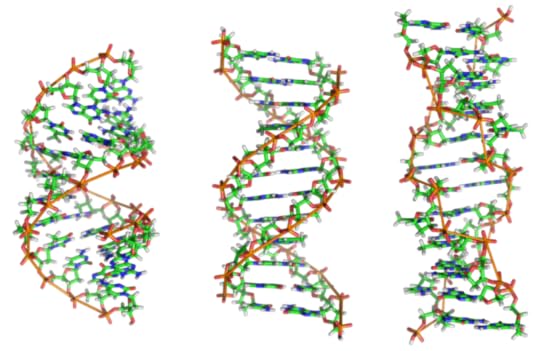

From left to right, the structures of A-, B-, and Z-DNA by Zephyris (Richard Wheeler). CC-BY-SA-3.0 from Wikimedia Commons.

From left to right, the structures of A-, B-, and Z-DNA by Zephyris (Richard Wheeler). CC-BY-SA-3.0 from Wikimedia Commons.Dramatizations of fictionalized individual, familial, and professional relationships that surround the ethical landscape of genomics create the potential to stimulate bioethical reflection and new perceptions amongst “actors” and the audience, sparking the moral imagination through the lens of others. By casting light on all “the storytellers” and the complexity of implications inherent with this powerful technology, dramatic narratives create vivid scenarios through which to imagine the challenges faced on the genomic path ahead, critique the application of bioethical traditions in context, and re-imagine alternative paradigms.

Building upon the legacy of using case vignettes as a clinical teaching modality, and inspired by “readers’ theater”, “narrative medicine,” and “narrative ethics” as approaches that helped us expand the analyses to implications of genomic technologies, our experience suggests similar value for bioethics education within the translational research and public policy domain. While drama has often been utilized in academic and medical settings to facilitate empathy and spotlight ethical and legal controversies such as end-of-life issues and health law, to date there appears to be few dramatizations focusing on next-generation sequencing (NGS) in genomic research and medicine.

We initially collaborated on the creation of a short vignette play in the context of genomic research and the informed consent process that was performed at the NHGRI-ELSI Congress by a geneticist, genetic counselor, bioethicists, and other conference attendees. The response by “actors” and audience fueled us to write many more plays of varying lengths on different ethical and genomic issues, as well as to explore the dialogues of existing theater with genetic and genomic themes — all to be presented and reflected upon by interdisciplinary professionals in the bioethics and genomics community at professional society meetings and academic medical institutions nationally and internationally.

Because narrative genomics is a pedagogical approach intended to facilitate discourse, as well as provide reflection on the interrelatedness of the cross-disciplinary issues posed, we ground our genomic plays in current scholarship and ensure that it is accurate scientifically as well as provide extensive references and pose focused bioethics questions which can complement and enhance the classroom experience.

In a similar vein, bioethical controversies can also be brought to life with this approach where bioethics reaching incorporates dramatizations and excerpts from existing theatrical narratives, whether to highlight bioethics issues thematically, or to illuminate the historical path to the genomics revolution and other medical innovations from an ethical perspective.

Varying iterations of these dramatic narratives have been experienced (read, enacted, witnessed) by bioethicists, policy makers, geneticists, genetic counselors, other healthcare professionals, basic scientists, bioethicists, lawyers, patient advocates, and students to enhance insight and facilitate interdisciplinary and interprofessional dialogue.

Dramatizations embedded in genomic narratives illuminate the human dimensions and complexity of interactions among family members, medical professionals, and others in the scientific community. By facilitating discourse and raising more questions than answers on difficult issues, narrative genomics links the promise and concerns of next-gen technologies with a creative bioethics pedagogical approach for learning from one another.

Heading image: Andrzej Joachimiak and colleagues at Argonne’s Midwest Center for Structural Genomics deposited the consortium’s 1,000th protein structure into the Protein Data Bank. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Illuminating the drama of DNA: creating a stage for inquiry appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat will it take to reduce infections in the hospital?Biologists that changed the worldA Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 3

Related StoriesWhat will it take to reduce infections in the hospital?Biologists that changed the worldA Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 3

Battels and subfusc: the language of Oxford

Now that Noughth Week has come to an end and the university Full Term is upon us, I thought it might be an appropriate time to investigate the arcane world of Oxford jargon — the University of Oxford, that is. New students, or freshers, do not arrive in Oxford but come up; at the end of term they go down (irrespective of where they live). If they misbehave they may find themselves being sent down by the proctors (a variant of the legal procurator), or — for less heinous crimes — merely rusticated, a form of suspension which, etymologically at least, involves being sent to the countryside (Latin rusticus). The formal beginning of a degree is known as matriculation, a ceremony held in the Sheldonian Theatre, in which membership of the university is conferred by being having one’s name entered on the register, or matricula.

Tutors, fellows, and readers

Being a student of the university involves membership of one of the colleges or private halls; despite their names, St Edmund (Teddy) Hall and Lady Margaret Hall are actually colleges; Regent’s Park College is neither a college nor a park. Christ Church should be referred to simply as Christ Church, rather than Christ Church College, although it is also known as ‘the House’. Magdalen is pronounced ‘maudlin’ and should never be confused with another college of the same name at Cambridge University (affectionately known as ‘The Other Place’, originally a euphemism for hell), which is pronounced the same but spelled Magdalene.

Oxford students in subfusc at 2003 Matriculation in the Sheldonian Theatre. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Oxford students in subfusc at 2003 Matriculation in the Sheldonian Theatre. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.Each college has a head of house, referred to by a variety of terms: Principal, President, Dean, Master, Provost, Rector, or Warden. Teaching in college takes the form of tutorials (or tutes), overseen by Colleges tutors (from a Latin word for ‘protector’); the earliest tutors were responsible for a student’s general welfare — a post now known as moral tutor. Colleges are governed by a body of fellows (students at Christ Church), or dons, from Latin dominus ‘master’. The title reader, a medieval term for a teacher used to refer to a lecturer below the rank of professor, has recently been retired at Oxford in favour of the American title associate professor.

Mods and battels

At Oxford, students read rather than study a subject, a usage which goes back to the Middle Ages. Final examinations were originally known as Greats; this term is now used only of the degree of Literae Humaniores (‘more humane letters’) — Classics to everyone else. No longer in use is the equivalent term Smalls for the first year exams; these are now known as Moderations (or Mods) in the Humanities, or Preliminaries (or Prelims) in the Sciences. Sadly, the slang equivalents great go and little go have now fallen out of use. University examinations are sat in Schools, a forbidding edifice on the High Street (or ‘the High’) which gets its name from its original use for holding scholastic disputations. Students are required to wear formal academic dress to sit exams; this is known as subfusc, from Latin subfuscus ‘somewhat dark’.

College exams, rather less formal affairs, are known today as collections, from Latin collectiones, ‘gathering together’, so-called because they occurred at the end of term when fees were due for collection. Confusingly, the term collection is also used to refer to the end-of-term meeting where a progress report is read by a student’s tutor in the presence of the master of the college. As well as fees, students must pay their battels, a bill for food purchased from the College buttery — originally a wine store, from Latin butta ‘cask’, but now extended to include a range of student delicacies.

Lecturers dusting off their notes and preparing for the new term, for whom such usages are second-nature, may benefit from the salutary lesson of the wall-lecture –a term coined by their 17th-century forbears for a lecture delivered to an empty room. The term may be obsolete, but the prospect remains all too real.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Heading image: New College Oxford chapel by Olaf Davis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Battels and subfusc: the language of Oxford appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1Why learn Arabic?

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1Why learn Arabic?

Biologists that changed the world

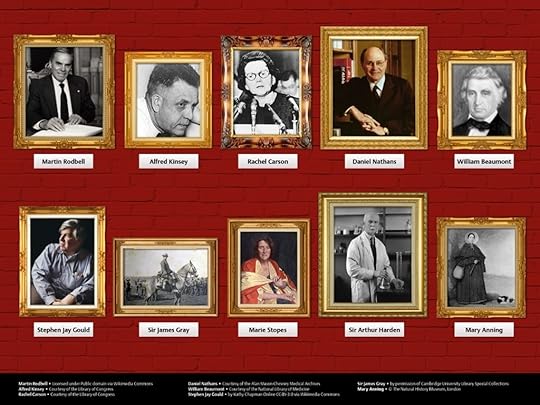

Biology Week is an annual celebration of the biological sciences that aims to inspire and engage the public in the wonders of biology. The Society of Biology created this awareness day in 2012 to give everyone the chance to learn and appreciate biology, the science of the 21st century, through varied, nationwide events. Our belief that access to education and research changes lives for the better naturally supports the values behind Biology Week, and we are excited to be involved in it year on year.

Biology, as the study of living organisms, has an incredibly vast scope. We’ve identified some key figures from the last couple of centuries who traverse the range of biology: from physiology to biochemistry, sexology to zoology. You can read their stories by checking out our Biology Week 2014 gallery below. These biologists, in various different ways, have had a significant impact on the way we understand and interact with biology today. Whether they discovered dinosaurs or formed the foundations of genetic engineering, their stories have plenty to inspire, encourage, and inform us.

If you’d like to learn more about these key figures in biology, you can explore the resources available on our Biology Week page, or sign up to our e-alerts to stay one step ahead of the next big thing in biology.

Headline image credit: Marie Stopes in her laboratory, 1904, by Schnitzeljack. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Biologists that changed the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe life of a bubbleGoing inside to get a taste of natureCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014

Related StoriesThe life of a bubbleGoing inside to get a taste of natureCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014

The chimera of anti-politics

Anti-politics is in the air. There is a prevalent feeling in many societies that politicians are up to no good, that establishment politics are at best irrelevant and at worst corrupt and power-hungry, and that the centralization of power in national parliaments and governments denies the public a voice. Larger organizations fare even worse, with the European Union’s ostensible detachment from and imperviousness to the real concerns of its citizens now its most-trumpeted feature. Discontent and anxiety build up pressure that erupts in the streets from time to time, whether in Takhrir Square or Tottenham. The Scots rail against a mysterious entity called Westminster; UKIP rides on the crest of what it terms patriotism (and others term typical European populism) intimating, as Matthew Goodwin has pointed out in the Guardian, that Nigel Farage “will lead his followers through a chain of events that will determine the destiny of his modern revolt against Westminster.”

At the height of the media interest in Wootton Bassett, when the frequent corteges of British soldiers who were killed in Afghanistan wended their way through the high street while the townspeople stood in silence, its organizers claimed that it was a spontaneous and apolitical display of respect. “There are no politics here,” stated the local MP. Those involved held that the national stratum of politicians was superfluous to the authentic feeling of solidarity that could solely be generated at the grass roots. A clear resistance emerged to national politics trying to monopolize the mourning that only a town at England’s heart could convey.

Academics have been drawn in to the same phenomenon. A new Anti-politics and Depoliticization Specialist Group has been set up by the Political Studies Association in the UK dedicated, as it describes itself, to “providing a forum for researchers examining those processes throughout society that seem to have marginalized normative political debates, taken power away from elected politicians and fostered an air of disengagement, disaffection and disinterest in politics.” The term “politics” and what it apparently stands for is undoubtedly suffering from a serious reputational problem.

Tottenham Riots, by Beacon Radio. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Tottenham Riots, by Beacon Radio. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.But all that is based on a misunderstanding of politics. Political activity and thinking isn’t something that happens in remote places and institutions outside the experience of everyday life. It is ubiquitous, rooted in human intercourse at every level. It is not merely an elite activity but one that every one of us engages in consciously or unconsciously in our relations with others: commanding, pleading, negotiating, arguing, agreeing, refusing, or resisting. There is a tendency to insist on politics being mainly about one thing: power, dissent, consensus, oppression, rupture, conciliation, decision-making, the public domain, are some of the competing contenders. But politics is about them all, albeit in different combinations.

It concerns ranking group priorities in terms of urgency or importance—whether the group is a family, a sports club, or a municipality. It concerns attempts to achieve finality in human affairs, attempts always doomed to fail yet epitomised in language that refers to victory, authority, sovereignty, rights, order, persuasion—whether on winning or losing sides of political struggle. That ranges from a constitutional ruling to the exasperated parent trying to end an argument with a “because I say so.” It concerns order and disorder in human gatherings, whether parliaments, trade union meetings, classrooms, bus queues, or terrorist attacks—all have a political dimension alongside their other aspects. That gives the lie to a demonstration being anti-political, when its ends are reform, revolution, or the expression of disillusionment. It concerns devising plans and weaving visions for collectivities. It concerns the multiple languages of support and withholding support that we engage in with reference to others, from loyalty and allegiance through obligation to commitment and trust. And it is manifested through conservative, progressive, or reactionary tendencies that the human personality exhibits.

When those involved in the Wootton Bassett corteges claimed to be non-political, they overlooked their organizational role in making certain that every detail of the ceremony was in place. They elided the expression of national loyalty that those homages clearly entailed. They glossed over the tension between political centre and periphery that marked an asymmetry of power and voice. They assumed, without recognizing, the prioritizing of a particular group of the dead – those that fell in battle.

People everywhere engage in political practices, but they do so in different intensities. It makes no more sense to suggest that we are non-political than to suggest that we are non-psychological. Nor does anti-politics ring true, because political disengagement is still a political act: sometimes vociferously so, sometimes seeking shelter in smaller circles of political conduct. Alongside political philosophy and the history of political thought, social scientists need to explore the features of thinking politically as typical and normal features of human life. Those patterns are always with us, though their cultural forms will vary considerably across and within societies. Being anti-establishment, anti-government, anti-sleaze, even anti-state are themselves powerful political statements, never anti-politics.

Headline image credit: Westminster, by “Stròlic Furlàn” – Davide Gabino. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The chimera of anti-politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the USCan Cameron capture women’s votes?Who decides ISIS is a terrorist group?

Related StoriesGangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the USCan Cameron capture women’s votes?Who decides ISIS is a terrorist group?

October 17, 2014

What will it take to reduce infections in the hospital?

The outbreak of Ebola, in Africa and in the United States, is a stark reminder of the clear and present danger that infection represents in all our lives, and we need reminding. Despite all of our medical advances, more familiar infections still take tens of thousands of American lives each year – and too often these deaths are avoidable.

Hospital infections kill 75,000 Americans a year — more than twice the number of people who die in car crashes. Most people know that motor vehicle deaths could be drastically reduced. What’s not as widely appreciated is that the far greater number of hospital infections could be reduced by up to 70%.

Changes that would reduce infections are evidence-based and scientific, supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For example, the campaign against hospital-acquired urinary tract infection — one of the most common hospital infections in the world — seeks to minimize the use of internal, Foley catheters, a major vector of infection. Nurses who have always relied on Foleys to deal with patients who have urinary incontinence are told to use straight catheters intermittently instead, which increases their workload. Surgeons who are accustomed to placing Foley catheters in their patients for several days after an operation are told to remove the catheter shortly after surgery – or not to use one at all. Similar approaches can be used to reduce other common infections. If we know what needs to be done to lower the rate of hospital infections, why have the many attempts to do so fallen so woefully short?

Our research shows that a major reason is the unwillingness of some nurses and physicians to support the desired new behaviors. We have found that opposition to hospitals’ infection prevention initiatives comes from the three groups we call Active Resisters, Organizational Constipators, and Timeservers. While we know these types of individuals exist in hospitals since we have seen them in action, we suspect they can also be found in all types of organizations.

Active resisters refuse to abide by and sometimes campaign against an initiative’s proposed changes. Some active resisters refuse to change a practice they have used for years because they fear it might have a negative impact on their patients’ health. Others resist because they doubt the scientific validity of a change, or because the change is inconvenient. For others it’s simply a matter of ego, as in, “Don’t tell me what to do.” Some ignore the evidence. Many initiatives to prevent urinary tract infection ask nurses to remind physicians when it’s time to remove an indwelling catheter, but many nurses are unwilling to confront physicians – and many physicians are unwilling to be so confronted.

Organizational constipators present a different set of challenges. Most are mid- to upper-level staff members who have nothing against an infection prevention initiative per se but simply enjoy exercising their power. Sometimes they refuse to permit underlings to help with an initiative. Sometimes they simply do nothing, allowing memos and emails to pile up without taking action. While we have met some physicians in this category, we have seen, unfortunately, a surprising number of nursing leaders employ this approach.

Timeservers do the least possible in any circumstance. That applies to every aspect of their work, including preventing infection. A timeserver surgeon may neglect to wash her hands before examining a patient, not because she opposes that key infection prevention requirement but because it’s just easier that way. A timeserver nurse may “forget” to conduct “sedation vacations” for patients who are on mechanical breathing machines to assess if the patient can be weaned from the ventilator sooner for the simple reason that sedated patients are less work.

Hospital corridor. © Spotmatik via iStock.

Hospital corridor. © Spotmatik via iStock.We have learned that different overcoming these human-related barriers to improvement requires different styles of engagement.

To win support among the active resisters, we recommend employing data both liberally and strategically. Doctors are trained to respond to facts, and a graph that shows a high rate of infection department can help sway them. Sharing research from respected journals describing proven methods of preventing infection can also help overcome concerns. Nurse resisters are similarly impressed by such data, but we find that they are also likely to be convinced by appeals to their concern for their patients’ welfare – a description, for example, of the discomfort the Foley causes their patients.

Organizational constipators and timeservers are more difficult to win over, largely because their negative behavior is an incidental result of their normal operating style. Managers sometimes try to work around the organizational constipators and assign an authority figure to harass the timeservers, but their success is limited. Efforts to fire them can sometimes be difficult.

Hospitals’ administrative and medical leaders often play an important role in successful infection prevention initiatives by emphasizing their approval in their staff encounters, by occasionally attending an infection prevention planning session, and by making adherence to the goals of the initiative a factor in employee performance reviews. Some innovative leaders also give out physician or nurse champion-of-the-year awards that serve the dual purpose of rewarding the healthcare workers who have been helpful in a successful initiative while encouraging others by showing that they, too, could someday receive similar recognition. It may help to include potential obstructors in planning for an infection prevention campaign; the critics help spot weaknesses and are also inclined to go easy on the campaign once it gets underway.

But the leadership of a successful infection prevention project can also come from lower down in a hospital’s hierarchy, with or without the active support of the senior executives. We found the key to a positive result is a culture of excellence, when the hospital staff is fully devoted to patient-centered, high-quality care. Healthcare workers in such hospitals endeavor to treat each patient as a family member. In such institutions, a dedicated nurse can ignite an infection prevention initiative, and the staff’s all-but-universal commitment to patient safety can win over even the timeservers. The closer the nation’s hospitals approach that state of grace, the greater the success they will have in their efforts to lower infection rates.

Preventing infection is a team sport. Cooperation — among doctors, nurses, microbiologists, public health officials, patients, and families — will be required to control the spread of Ebola. Such cooperation is required to prevent more mundane infections as well.

The post What will it take to reduce infections in the hospital? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGoing inside to get a taste of natureThe deconstruction of paradoxes in epidemiologyCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014

Related StoriesGoing inside to get a taste of natureThe deconstruction of paradoxes in epidemiologyCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014

Recap of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

Last weekend we were thrilled to see so many of you at the 2014 Oral History Association (OHA) Annual Meeting, “Oral History in Motion: Movements, Transformations, and the Power of Story.” The panels and roundtables were full of lively discussions, and the social gatherings provided a great chance to meet fellow oral historians. You can read a recap from Margo Shea, or browse through the Storify below, prepared by Jaycie Vos, to get a sense of the excitement at the meeting. Over the next few weeks, we’ll be sharing some more in depth blog posts from the meeting, so make sure to check back often.

We look forward to seeing you all next year at the Annual Meeting in Florida. And special thanks to Margo Shea for sending in her reflections on the meeting and to Jaycie Vos (@jaycie_v) for putting together the Storify.

[View the story "OHA 2014" on Storify]

Headline image credit: Madison, Wisconsin cityscape at night, looking across Lake Monona from Olin Park. Photo by Richard Hurd. CC BY 2.0 via rahimageworks Flickr.

The post Recap of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe power of oral history as a history-making practiceSo Long, FarewellA preview of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

Related StoriesThe power of oral history as a history-making practiceSo Long, FarewellA preview of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

A Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 3

We’re getting ready for Halloween this month by reading the classic horror stories that set the stage for the creepy movies and books we love today. Check in every Friday this October as we tell Fitz-James O’Brien’s tale of an unusual entity in What Was It?, a story from the spine-tingling collection of works in Horror Stories: Classic Tales from Hoffmann to Hodgson, edited by Darryl Jones. Last we left off the narrator was headed to bed after a night of opium and philosophical conversation with Dr. Hammond, a friend and fellow boarded at the supposed haunted house where they are staying.

We parted, and each sought his respective chamber. I undressed quickly and got into bed, taking with me, according to my usual custom, a book, over which I generally read myself to sleep. I opened the volume as soon as I had laid my head upon the pillow, and instantly flung it to the other side of the room. It was Goudon’s ‘History of Monsters,’—a curious French work, which I had lately imported from Paris, but which, in the state of mind I had then reached, was anything but an agreeable companion. I resolved to go to sleep at once; so, turning down my gas until nothing but a little blue point of light glimmered on the top of the tube, I composed myself to rest.

The room was in total darkness. The atom of gas that still remained alight did not illuminate a distance of three inches round the burner. I desperately drew my arm across my eyes, as if to shut out even the darkness, and tried to think of nothing. It was in vain. The confounded themes touched on by Hammond in the garden kept obtruding themselves on my brain. I battled against them. I erected ramparts of would-be blankness of intellect to keep them out. They still crowded upon me. While I was lying still as a corpse, hoping that by a perfect physical inaction I should hasten mental repose, an awful incident occurred. A Something dropped, as it seemed, from the ceiling, plumb upon my chest, and the next instant I felt two bony hands encircling my throat, endeavoring to choke me.

I am no coward, and am possessed of considerable physical strength. The suddenness of the attack, instead of stunning me, strung every nerve to its highest tension. My body acted from instinct, before my brain had time to realize the terrors of my position. In an instant I wound two muscular arms around the creature, and squeezed it, with all the strength of despair, against my chest. In a few seconds the bony hands that had fastened on my throat loosened their hold, and I was free to breathe once more. Then commenced a struggle of awful intensity. Immersed in the most profound darkness, totally ignorant of the nature of the Thing by which I was so suddenly attacked, finding my grasp slipping every moment, by reason, it seemed to me, of the entire nakedness of my assailant, bitten with sharp teeth in the shoulder, neck, and chest, having every moment to protect my throat against a pair of sinewy, agile hands, which my utmost efforts could not confine,—these were a combination of circumstances to combat which required all the strength, skill, and courage that I possessed.

At last, after a silent, deadly, exhausting struggle, I got my assailant under by a series of incredible efforts of strength. Once pinned, with my knee on what I made out to be its chest, I knew that I was victor. I rested for a moment to breathe. I heard the creature beneath me panting in the darkness, and felt the violent throbbing of a heart. It was apparently as exhausted as I was; that was one comfort. At this moment I remembered that I usually placed under my pillow, before going to bed, a large yellow silk pocket-handkerchief. I felt for it instantly; it was there. In a few seconds more I had, after a fashion, pinioned the creature’s arms.

I now felt tolerably secure. There was nothing more to be done but to turn on the gas, and, having first seen what my midnight assailant was like, arouse the household. I will confess to being actuated by a certain pride in not giving the alarm before; I wished to make the capture alone and unaided.

Never losing my hold for an instant, I slipped from the bed to the floor, dragging my captive with me. I had but a few steps to make to reach the gas-burner; these I made with the greatest caution, holding the creature in a grip like a vice. At last I got within arm’s-length of the tiny speck of blue light which told me where the gas-burner lay. Quick as lightning I released my grasp with one hand and let on the full flood of light. Then I turned to look at my captive.

I cannot even attempt to give any definition of my sensations the instant after I turned on the gas. I suppose I must have shrieked with terror, for in less than a minute afterward my room was crowded with the inmates of the house. I shudder now as I think of that awful moment. I saw nothing! Yes; I had one arm firmly clasped round a breathing, panting, corporeal shape, my other hand gripped with all its strength a throat as warm, and apparently fleshly, as my own; and yet, with this living substance in my grasp, with its body pressed against my own, and all in the bright glare of a large jet of gas, I absolutely beheld nothing! Not even an outline,—a vapor!

I do not, even at this hour, realize the situation in which I found myself. I cannot recall the astounding incident thoroughly. Imagination in vain tries to compass the awful paradox.

It breathed. I felt its warm breath upon my cheek. It struggled fiercely. It had hands. They clutched me. Its skin was smooth, like my own. There it lay, pressed close up against me, solid as stone,—and yet utterly invisible!

I wonder that I did not faint or go mad on the instant. Some wonderful instinct must have sustained me; for, absolutely, in place of loosening my hold on the terrible Enigma, I seemed to gain an additional strength in my moment of horror, and tightened my grasp with such wonderful force that I felt the creature shivering with agony.

Just then Hammond entered my room at the head of the household. As soon as he beheld my face—which, I suppose, must have been an awful sight to look at—he hastened forward, crying, ‘Great heaven, Harry! what has happened?’

‘Hammond! Hammond!’ I cried, ‘come here. O, this is awful!

I have been attacked in bed by something or other, which I have hold of; but I can’t see it,—I can’t see it!’

Hammond, doubtless struck by the unfeigned horror expressed in my countenance, made one or two steps forward with an anxious yet puzzled expression. A very audible titter burst from the remainder of my visitors. This suppressed laughter made me furious. To laugh at a human being in my position! It was the worst species of cruelty. Now, I can understand why the appearance of a man struggling violently, as it would seem, with an airy nothing, and calling for assistance against a vision, should have appeared ludicrous. Then, so great was my rage against the mocking crowd that had I the power I would have stricken them dead where they stood.

‘Hammond! Hammond!’ I cried again, despairingly, ‘for God’s sake come to me. I can hold the—the thing but a short while longer. It is overpowering me. Help me! Help me!’

‘Harry,’ whispered Hammond, approaching me, ‘you have been smoking too much opium.’

‘I swear to you, Hammond, that this is no vision,’ I answered, in the same low tone. ‘Don’t you see how it shakes my whole frame with its struggles? If you don’t believe me, convince yourself. Feel it,— touch it.’

Hammond advanced and laid his hand in the spot I indicated. A wild cry of horror burst from him. He had felt it! In a moment he had discovered somewhere in my room a long piece of cord, and was the next instant winding it and knotting it about the body of the unseen being that I clasped in my arms.

‘Harry,’ he said, in a hoarse, agitated voice, for, though he preserved his presence of mind, he was deeply moved, ‘Harry, it’s all safe now. You may let go, old fellow, if you’re tired. The Thing can’t move.’

I was utterly exhausted, and I gladly loosed my hold.

Check back next Friday, 24 October to find out what happens next. Missed a part of the story? Catch up with part 1 and part 2.

Headline image credit: Green Scream by Matt Coughlin, CC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 3 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it?A Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 2“There is no escape.” Horace Walpole and the terrifying rise of the Gothic

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it?A Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 2“There is no escape.” Horace Walpole and the terrifying rise of the Gothic

Going inside to get a taste of nature

For many of us, nature is defined as an outdoor space, untouched by human hands, and a place we escape to for refuge. We often spend time away from our daily routines to be in nature, such as taking a backwoods camping trip, going for a long hike in an urban park, or gardening in our backyard. Think about the last time you were out in nature, what comes to mind? For me, it was a canoe trip with friends. I can picture myself in our boat, the sound of the birds and rustling leaves in the background, the smell of cedars mixed with the clearing morning mist, and the sight of the still waters in front of me. Most of all, I remember a sense of calmness and clarity which I always achieve when I’m in nature.

Nature takes us away from the demands of life, and allows us to concentrate on the world around us with little to no effort. We can easily be taken back to a summer day by the smell of fresh cut grass, and force ourselves to be still to listen to the distant sound of ocean waves. Time in nature has a wealth of benefits from reducing stress, improving mood, increasing attentional capacities, and facilitating and creating social bonds. A variety of work supports nature being healing and health promoting at both an individual level (such as being energized after a walk with your dog) and a community level (such as neighbors coming together to create a local co-op garden). However, it can become difficult to experience the outdoors when we spend most of our day within a built environment.

I’d like you to stop for a moment and look around. What do you see? Are there windows? Are there any living plants or animals? Are the walls white? Do you hear traffic or perhaps the hum of your computer? Are you smelling circulated air? As I write now I hear the buzz of the florescent lights above me, and take a deep inhale of the lingering smell from my morning coffee. There is no nature except for the few photographs of the countryside and flowers that I keep tapped to my wall. I often feel hypocritical researching nature exposure sitting in front of a computer screen in my windowless office. But this is the reality for most of us. So how can we tap into the benefits of nature in order to create healthy and healing indoor environments that mimic nature and provide us with the same benefits as being outdoors?

Crater Lake Garfield Peak Trail View East by Markgorzynski. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Crater Lake Garfield Peak Trail View East by Markgorzynski. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Urban spaces often get a bad rap. Sure, they’re typically overcrowded, high in pollution, and limited in their natural and green spaces, but they also offer us the ability to transform the world around us into something that is meaningful and also health promoting. Beyond architectural features such as skylights, windows, and open air courtyards, we can use ambient features to adapt indoor spaces to replicate the outdoors. The integration of plants, animals, sounds, scents, and textures into our existing indoor environments enables us to create a wealth of natural environments indoors.

Notable examples of indoor nature, are potted plants or living walls in office spaces, atriums providing natural light, and large mural landscapes. In fact, much research has shown that the presence of such visual aids provides the same benefits of being outdoors. Incorporating just a few pieces of greenery into your workspace can help increase your productivity, boost your mood, improve your health, and help you concentrate on getting your work done. But being in nature is more than just seeing, it’s experiencing it fully and being immersed into a world that engages all of your senses. The use of natural sounds, scents, and textures (e.g. wooden furniture or carpets that look and feel like grass) provides endless possibilities for creating a natural environment indoors, and encouraging built environments to be therapeutic spaces. The more nature-like the indoor space can be, the more apt it is to illicit the same psychological and physical benefits that being outdoors does. Ultimately, the built environment can engage my senses in a way that brings me back to my canoe trip, and help me feel that same clarity and calmness that I did on the lake.

On a broader level, indoor nature may also be a means of encouraging sustainable and eco-friendly behaviors. With more generations growing up inside, we risk creating a society that is unaware of the value of nature. It’s easy to suggest that the solution to our declining involvement with nature is to just “go outside”; but with today’s busy lifestyle, we cannot always afford the time and money to step away. Integrating nature into our indoor environment is one way to foster the relationship between us and nature, and to encourage a sense of stewardship and appreciation for our natural world. By experiencing the health promoting and healing properties of nature, we can instill individuals with the significance of our natural world.

As I look around my office I’ve decided I need to take some of my own advice and bring my own little piece of nature inside. I encourage you to think about what nature means to you, and how you can incorporate this meaning into your own space. Does it involve fresh cut flowers? A photograph of your annual family campsite? The sound of birds in the background as you work? Whatever it is, I’m sure it’ll leave you feeling a little bit lighter, and maybe have you working a little bit faster.

Image: World Financial Center Winter Garden by WiNG. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Going inside to get a taste of nature appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014Celebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014 - EnclosureThe deconstruction of paradoxes in epidemiology

Related StoriesCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014Celebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014 - EnclosureThe deconstruction of paradoxes in epidemiology

The deconstruction of paradoxes in epidemiology

If a “revolution” in our field or area of knowledge was ongoing, would we feel it and recognize it? And if so, how?

I think a methodological “revolution” is probably going on in the science of epidemiology, but I’m not totally sure. Of course, in science not being sure is part of our normal state. And we mostly like it. I had the feeling that a revolution was ongoing in epidemiology many times. While reading scientific articles, for example. And I saw signs of it, which I think are clear, when reading the latest draft of the forthcoming book Causal Inference by M.A. Hernán and J.M. Robins from Harvard (Chapman & Hall / CRC, 2015). I think the “revolution” — or should we just call it a “renewal”? — is deeply changing how epidemiological and clinical research is conceived, how causal inferences are made, and how we assess the validity and relevance of epidemiological findings. I suspect it may be having an immense impact on the production of scientific evidence in the health, life, and social sciences. If this were so, then the impact would also be large on most policies, programs, services, and products in which such evidence is used. And it would be affecting thousands of institutions, organizations and companies, millions of people.

One example: at present, in clinical and epidemiological research, every week “paradoxes” are being deconstructed. Apparent paradoxes that have long been observed, and whose causal interpretation was at best dubious, are now shown to have little or no causal significance. For example, while obesity is a well-established risk factor for type 2 diabetes (T2D), among people who already developed T2D the obese fare better than T2D individuals with normal weight. Obese diabetics appear to survive longer and to have a milder clinical course than non-obese diabetics. But it is now being shown that the observation lacks causal significance. (Yes, indeed, an observation may be real and yet lack causal meaning.) The demonstration comes from physicians, epidemiologists, and mathematicians like Robins, Hernán, and colleagues as diverse as S. Greenland, J. Pearl, A. Wilcox, C. Weinberg, S. Hernández-Díaz, N. Pearce, C. Poole, T. Lash , J. Ioannidis, P. Rosenbaum, D. Lawlor, J. Vandenbroucke, G. Davey Smith, T. VanderWeele, or E. Tchetgen, among others. They are building methodological knowledge upon knowledge and methods generated by graph theory, computer science, or artificial intelligence. Perhaps one way to explain the main reason to argue that observations as the mentioned “obesity paradox” lack causal significance, is that “conditioning on a collider” (in our example, focusing only on individuals who developed T2D) creates a spurious association between obesity and survival.

Influenza virus research by James Gathany for CDC. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Influenza virus research by James Gathany for CDC. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The “revolution” is partly founded on complex mathematics, and concepts as “counterfactuals,” as well as on attractive “causal diagrams” like Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs). Causal diagrams are a simple way to encode our subject-matter knowledge, and our assumptions, about the qualitative causal structure of a problem. Causal diagrams also encode information about potential associations between the variables in the causal network. DAGs must be drawn following rules much more strict than the informal, heuristic graphs that we all use intuitively. Amazingly, but not surprisingly, the new approaches provide insights that are beyond most methods in current use. In particular, the new methods go far deeper and beyond the methods of “modern epidemiology,” a methodological, conceptual, and partly ideological current whose main eclosion took place in the 1980s lead by statisticians and epidemiologists as O. Miettinen, B. MacMahon, K. Rothman, S. Greenland, S. Lemeshow, D. Hosmer, P. Armitage, J. Fleiss, D. Clayton, M. Susser, D. Rubin, G. Guyatt, D. Altman, J. Kalbfleisch, R. Prentice, N. Breslow, N. Day, D. Kleinbaum, and others.

We live exciting days of paradox deconstruction. It is probably part of a wider cultural phenomenon, if you think of the “deconstruction of the Spanish omelette” authored by Ferran Adrià when he was the world-famous chef at the elBulli restaurant. Yes, just kidding.

Right now I cannot find a better or easier way to document the possible “revolution” in epidemiological and clinical research. Worse, I cannot find a firm way to assess whether my impressions are true. No doubt this is partly due to my ignorance in the social sciences. Actually, I don’t know much about social studies of science, epistemic communities, or knowledge construction. Maybe this is why I claimed that a sociology of epidemiology is much needed. A sociology of epidemiology would apply the scientific principles and methods of sociology to the science, discipline, and profession of epidemiology in order to improve understanding of the wider social causes and consequences of epidemiologists’ professional and scientific organization, patterns of practice, ideas, knowledge, and cultures (e.g., institutional arrangements, academic norms, scientific discourses, defense of identity, and epistemic authority). It could also address the patterns of interaction of epidemiologists with other branches of science and professions (e.g. clinical medicine, public health, the other health, life, and social sciences), and with social agents, organizations, and systems (e.g. the economic, political, and legal systems). I believe the tradition of sociology in epidemiology is rich, while the sociology of epidemiology is virtually uncharted (in the sense of not mapped neither surveyed) and unchartered (i.e. not furnished with a charter or constitution).

Another way I can suggest to look at what may be happening with clinical and epidemiological research methods is to read the changes that we are witnessing in the definitions of basic concepts as risk, rate, risk ratio, attributable fraction, bias, selection bias, confounding, residual confounding, interaction, cumulative and density sampling, open population, test hypothesis, null hypothesis, causal null, causal inference, Berkson’s bias, Simpson’s paradox, frequentist statistics, generalizability, representativeness, missing data, standardization, or overadjustment. The possible existence of a “revolution” might also be assessed in recent and new terms as collider, M-bias, causal diagram, backdoor (biasing path), instrumental variable, negative controls, inverse probability weighting, identifiability, transportability, positivity, ignorability, collapsibility, exchangeable, g-estimation, marginal structural models, risk set, immortal time bias, Mendelian randomization, nonmonotonic, counterfactual outcome, potential outcome, sample space, or false discovery rate.

You may say: “And what about textbooks? Are they changing dramatically? Has one changed the rules?” Well, the new generation of textbooks is just emerging, and very few people have yet read them. Two good examples are the already mentioned text by Hernán and Robins, and the soon to be published by T. VanderWeele, Explanation in causal inference: Methods for mediation and interaction (Oxford University Press, 2015). Clues can also be found in widely used textbooks by K. Rothman et al. (Modern Epidemiology, Lippincott-Raven, 2008), M. Szklo and J Nieto (Epidemiology: Beyond the Basics, Jones & Bartlett, 2014), or L. Gordis (Epidemiology, Elsevier, 2009).

Finally, another good way to assess what might be changing is to read what gets published in top journals as Epidemiology, the International Journal of Epidemiology, the American Journal of Epidemiology, or the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Pick up any issue of the main epidemiologic journals and you will find several examples of what I suspect is going on. If you feel like it, look for the DAGs. I recently saw a tweet saying “A DAG in The Lancet!”. It was a surprise: major clinical journals are lagging behind. But they will soon follow and adopt the new methods: the clinical relevance of the latter is huge. Or is it not such a big deal? If no “revolution” is going on, how are we to know?

Feature image credit: Test tubes by PublicDomainPictures. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The deconstruction of paradoxes in epidemiology appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014Celebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014 - EnclosureTrauma and emotional healing

Related StoriesCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014Celebrating World Anaesthesia Day 2014 - EnclosureTrauma and emotional healing

October 16, 2014

The Oxford DNB at 10: biography and contemporary history

Autumn 2014 marked the tenth anniversary of the publication of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. In a series of blog posts, academics, researchers, and editors looked at aspects of the ODNB’s online evolution in the decade since 2004. In this final post of the series, Alex May—ODNB’s editor for the very recent past— considers the Dictionary as a record of contemporary history.

When it was first published in September 2004, the Oxford DNB included biographies of people who had died (all in the ODNB are deceased) on or before 31 December 2001. In the subsequent ten years we have continued to extend the Dictionary’s coverage into the twenty-first century—with regular updates recording those who have died since 2001. Of the 4300 people whose biographies have been added to the online ODNB in this decade, 2172 died between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2010 (our current terminus)—i.e., about 220 per year of death. While this may sound a lot, the average number of deaths per year over the same period in the UK was just short of 500,000, indicating a roughly one in 2300 chance of entering the ODNB. This does not yet approach the levels of inclusion for people who died the late nineteenth century, let alone earlier periods: someone dying in England in the first decade of the seventeenth century, for example, had a nearly three-times greater chance of being included in the ODNB than someone who died in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

‘Competition’ for spaces at the modern end of the dictionary is therefore fierce. Some subjects are certainties—prime ministers such as Ted Heath or Jim Callaghan, or Nobel prize-winning scientists such as Francis Crick or Max Perutz. There are perhaps fifty or sixty potential subjects a year about whose inclusion no-one would quibble. But there are as many as 1500 people on our lists each year, and for perhaps five or six hundred of them a very good case could be made.

This is where our advisers come in. Over the last ten years we have relied heavily on the help of some 500 people, experts and leading figures in their fields whether as scholars or practitioners, who have given unstintingly of their time and support. Advisers are enjoined to consider all the aspects of notability, including achievement, influence, fame, and notoriety. Of course, their assessments can often vary, particularly in the creative fields, but even in those it is remarkable how often they coincide.

Our advisers have also in most cases been crucial in identifying the right contributor for each new biography, whether he or she be a practitioner from the same field (we often ask politicians to write on politicians—Ted Heath and Jim Callaghan are examples of this—lawyers on lawyers, doctors on doctors, and so on), or a scholar of the particular subject area. Sadly, a number of our advisers and contributors have themselves entered the dictionary in this decade, among them the judge Tom Bingham, the politician Roy Jenkins, the journalist Tony Howard, and the historian Roy Porter.

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf at the Lucerne Festival, by Max Albert Wyss. CC-BY-2.5-Switzerland via Wikimedia Commons.

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf at the Lucerne Festival, by Max Albert Wyss. CC-BY-2.5-Switzerland via Wikimedia Commons.Just as the selection of subjects is made with an eye to an imaginary reader fifty or a hundred years’ hence (will that reader need or want to find out more about that person?), so the entries themselves are written with such a reader in view. ODNB biographies are not always the last word on a subject, but they are rarely the first. Most of the ‘recently deceased’ added to the Dictionary have received one or more newspaper obituary. ODNB biographies differ from newspaper obituaries in providing more, and more reliable, biographical information, as well as being written after a period of three to four years’ reflection between death and publication of the entry—allowing information to emerge and reputations to settle. In addition, ODNB lives attempt to provide an understanding of context, and a considered assessment (implicit or explicit) of someone’s significance: in short, they aim to narrate and evaluate a person’s life in the context of the history of modern Britain and the broad sweep of a work of historical reference.

The result, over the last ten years, has been an extraordinary collection of biographies offering insights into all corners of twentieth and early twenty-first century British life, from multiple angles. The subjects themselves have ranged from the soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf to the godfather of punk, Malcolm McLaren; the high tory Norman St John Stevas to the IRA leader Sean MacStiofáin; the campaigner Ludovic Kennedy to the jester Jeremy Beadle; and the turkey farmer Bernard Matthews to Julia Clements, founder of the National Association of Flower Arranging Societies. By birth date they run from the founder of the Royal Ballet, Dame Ninette de Valois (born in 1898, who died in 2001), to the ‘celebrity’ Jade Goody (born in 1981, who died in 2009). Mention of the latter reminds us of Leslie Stephen’s determination to represent the whole of human life in the pages of his original, Victorian DNB. Poignantly, in light of the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War, among the oldest subjects included in the dictionary are three of the ‘last veterans’, Harry Patch, Henry Allingham, and Bill Stone, who, as the entry on them makes clear, reacted very differently to the notion of commemoration and their own late fame.

The work of selecting from thousands of possible subjects, coupled with the writing and evaluation of the chosen biographies, builds up a contemporary picture of modern Britain as we record those who’ve shaped the very recent past. As we begin the ODNB’s second decade this work continues: in January 2015 we’ll publish biographies of 230 people who died in 2011 and we’re currently editing and planning those covering the years 2012 and 2013, including what will be a major article on the life, work, and legacy of Margaret Thatcher.

Links between biography and contemporary history are further evident online—creating opportunities to search across the ODNB by profession or education, and so reveal personal networks, associations, and encounters that have shaped modern national life. Online it’s also possible to make connections between people active in or shaped by national events. Searching for Dunkirk, or Suez, or the industrial disputes of the 1970s brings up interesting results. Searching for the ‘Festival of Britain’ identifies the biographies of 35 men and women who died between 2001-2010: not just the architects who worked on the structures or the sculptors and artists whose work was showcased, but journalists, film-makers, the crystallographer Helen Megaw (whose diagrams of crystal structures adorned tea sets used during the Festival), and the footballer Bobby Robson, who worked on the site as a trainee electrician. Separately, these new entries shed light not only on the individuals concerned but on the times in which they lived. Collectively, they amount to a substantial and varied slice of modern British national life.

Headline image credit: Harry Patch, 2007, by Jim Ross. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Oxford DNB at 10: biography and contemporary history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA welcome from David Cannadine, the new editor of the Oxford DNBThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biographyThe Oxford DNB at 10: new research opportunities in the humanities

Related StoriesA welcome from David Cannadine, the new editor of the Oxford DNBThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biographyThe Oxford DNB at 10: new research opportunities in the humanities

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers