Oxford University Press's Blog, page 745

October 31, 2014

Oxytocin and emotion recognition

Imagine you are in class and your friend has just made a fool of the teacher. How do you feel? Although this will depend on the personalities of those involved, you might well find yourself laughing along with your classmates at the teacher’s expense. The experience of sharing an emotion with your friends (in this case the fun of getting one over on the teacher) will probably strengthen your friendship further. But in a class of one hundred students, there are likely to be one or two who have trouble understanding the joke.

The ability to infer and understand other peoples’ emotions and beliefs plays an important role in human social relationships. However, for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) — a developmental disorder that affects approximately 1% of the population and for which there is no established treatment — this can be challenging. While high-functioning individuals with ASD may be able to compensate for difficulties in inferring others’ beliefs, they often continue to have trouble understanding others’ emotions, and this leads to impaired social functioning.

Increasing evidence suggests that oxytocin — a neuropeptide that promotes social behavior and bonding in humans and in animals — can improve emotion recognition in ‘typically developing’ individuals, i.e. those without ASD. Notably, oxytocin improves the ability to infer others’ emotions more than the ability to identify their beliefs. Oxytocin has also been shown to improve social behavior in individuals with autism and to partially reverse patterns of brain dysfunction thought to be responsible for the deficits. This has led to the suggestion that oxytocin could be used to develop medications for currently untreatable psychiatric conditions characterized by social impairments.

However, studies to date have only investigated the ability of oxytocin to improve recognition of basic emotions such as fear or happiness. These differ from “social” emotions such as embarrassment and shame, which require us to represent the mental state of another. Moreover, most existing studies have provided participants with so-called “direct cues” as to others’ emotions, such as their facial expressions or tone of voice. However, these cues are not always available in real life and the ability to identify others’ emotions using only indirect cues is itself important for social functioning. We therefore decided to investigate whether oxytocin would also improve the ability of individuals with ASD to recognise social emotions, even in the absence of direct cues.

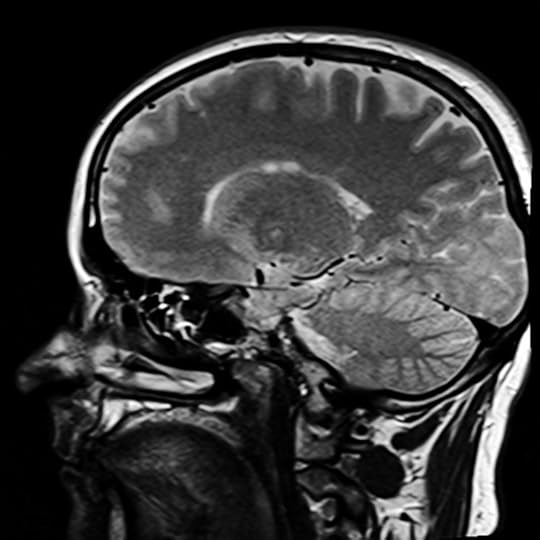

MRI of brain by bykst. Public Domain via Pixabay.

MRI of brain by bykst. Public Domain via Pixabay.To do so, we modified a cartoon-based task called the “Sally-Anne task,” which is commonly used to test for understanding of other peoples’ false beliefs, and used MRI scans to measure brain activity in subjects with and without ASD as they performed the task. In the standard version, participants are shown a cartoon in which one protagonist (Sally) places a ball in a box and then leaves the room. In her absence, another protagonist (Anne) moves the ball to a second box to the right of the first, and Sally then returns. At the end of the story, participants are asked the following questions: “Is the ball in the left-hand box?” to test comprehension of the story, and “Does Sally look for her ball in the left-hand box?” to test for understanding of Sally’s false belief about the location of the ball. To examine participants’ ability to infer others’ emotions, we introduced a third question: “How does Anne feel when Sally opens the left-hand box?”. Given that Ann’s gain effectively depends on Sally’s loss, the emotions involved will be complex social emotions: Ann, for example, might gloat upon realizing that she has fooled Sally by moving the ball.

We discovered that individuals with ASD are less accurate than IQ-matched controls in inferring social emotions in the absence of direct cues such as facial expressions. Moreover, individuals with ASD showed lower activity than controls in two brain regions that contribute to this ability, namely the right anterior insula and superior temporal sulcus. Individuals with ASD who had a normal IQ were not significantly impaired in inferring others’ beliefs; however, they did show lower brain activity than controls in a region implicated in this process, the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.

In order to determine whether oxytocin could improve the ability of individuals with ASD to identify others’ social emotions, we conducted a double-blind trial. We administered a single dose of either oxytocin or placebo in the form of an intranasal spray to subjects with ASD and to matched controls. As predicted, oxytocin increased the accuracy with which individuals with ASD were able to identify others’ social emotions in the absence of direct cues, and also enhanced their originally-diminished brain activity in the right anterior insula. This increase in activity was not observed in other brain regions or during attempts to understand others’ beliefs, suggesting that oxytocin acts specifically on the ability to infer social emotions.

Ultimately therefore, the results of our behavioral experiments and brain activity studies lend support to the idea that intranasal oxytocin could potentially form the basis of a treatment for at least some of the social impairments in ASD.

Heading image: Oxytocin-neurophysin by Edgar181. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Oxytocin and emotion recognition appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesStress before birthNeurology and psychiatry in BabylonStem cell therapy for diabetes

Related StoriesStress before birthNeurology and psychiatry in BabylonStem cell therapy for diabetes

Stem cell therapy for diabetes

This month, it was reported that scientists at Harvard University have successfully made insulin-secreting beta cells from human pluripotent stem cells. This is an important milestone towards a “stem cell therapy” for diabetes, which will have huge effects on human medicine.

Diabetes is a group of diseases in which the blood glucose is too high. In type 1 diabetes, the patients have an autoimmune disease that causes destruction of their insulin-producing cells (the beta cells of the pancreas). Insulin is the hormone that enables glucose to enter the cells of the tissues and in its absence the glucose remains in the blood and cannot be used. In type 2 diabetes the beta cells are usually somewhat defective and cannot adapt to the increased demand often associated with age and/or obesity. Despite the availability of insulin for treating diabetes since the 1920s, the disease is still a huge problem. If the level of blood glucose is not perfectly controlled it will cause damage to blood vessels and this eventually leads to various unpleasant complications including heart failure, stroke, kidney failure, blindness, and gangrene of limbs. Apart from the considerable suffering of the affected patients, the costs of dealing with diabetes is a huge financial burden for all health services. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in particular is rising in most parts of the world and the number of patients is now counted in the hundreds of millions.

To get perfect control of blood glucose, insulin injections will never be quite good enough. The beta cells of the pancreas are specialised to secrete exactly the correct amount of insulin depending on the level of glucose they detect in the blood. At present the only sources of beta cells for transplantation are the pancreases taken from deceased organ donors. However this has enabled a clinical procedure to the introduced called “islet transplantation”. Here, the pancreatic islets (which contain the beta cells) are isolated from one or more donor pancreases and are infused into the liver of the diabetic patient. The liver has a similar blood supply to the pancreas and the procedure to infuse the cells is surgically very simple. The experience of islet transplants has shown that the technique can cure diabetes, at least in the short term. But there are three problems. Firstly the grafts tend to lose activity over a few years and eventually the patients are back on injected insulin. Secondly the grafts require permanent immunosuppression with drugs to avoid rejection by the host, and this can lead to problems. Thirdly, and most importantly, the supply of donor pancreases is very limited and only a tiny fraction of what is really needed.

Syringe, by Blausen.com staff. “Blausen gallery 2014″. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Syringe, by Blausen.com staff. “Blausen gallery 2014″. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThis background may explain why the production of human beta cells has been a principal objective of stem cell research for many years. If unlimited numbers of beta cells could be produced from somewhere then at least the problem of supply would be solved and transplants could be made available for many more people. Although there are other potential sources, most effort has gone into making beta cells from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSC). These resemble cells of the early embryo: they can be grown without limit in culture, and they can differentiate into most of the cell types found in the body. hPSC comprise embryonic stem cells, made by culturing cells directly from early human embryos; and also “induced pluripotent stem cells” (iPSC), made by introducing selected genes into other cell types to reprogram them to an embryonic state. The procedures for making hPSC into beta cells have been designed based on the knowledge obtained by developmental biologists about how the pancreas and the beta cells arise during normal development of the embryo. This has shown that there are several stages of cell commitment, each controlled by different extracellular signal substances. Mimicking this series of events in culture should, theoretically, yield beta cells in the dish. In reality some art as well as science is required to create useful differentiation protocols. Many labs have been involved in this work but until now the best protocols could only generate immature beta cells, which have a low insulin content and do not secrete insulin when exposed to glucose. The new study has developed a protocol yielding fully functional mature beta cells which have the same insulin content as normal beta cells and which secrete insulin in response to glucose in the same way. These are the critical properties that have so far eluded researchers in this area and are essential for the cells to be useful for transplantation. Also, unlike most previous procedures, the new Harvard method grows the cells as clumps in suspension, which means that it is capable of producing the large number of cells required for human transplants.

These cells can cure diabetes in diabetic mice, but when will they be tried in humans? This will depend on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the USA. The FDA has so far been very cautious about stem cell therapies because they do not want to see cells implanted that will grow without control and become cancerous. One thing they will insist on is extremely good evidence that there are absolutely none of the original pluripotent cells left in the transplant, as they would probably develop into tumours. This highlights the fact that the treatment is not really “stem cell therapy” at all, it is actually “differentiated cell therapy” where the transplanted cells are made from stem cells instead of coming from organ donors. The FDA will also much prefer a delivery method which will enable the cells to be removed, something which is not the case with current islet transplants. One much discussed possibility is “encapsulation” whereby the cells are enclosed in a semipermeable membrane that can let nutrients in and insulin out but will not allow cells to escape. This might also enable the use of immunosuppressive drugs to be avoided, as encapsulation is also intended to provide a barrier against the immune cells of the host.

Stem cell therapy has been hyped for years but with the exception of the long established bone marrow transplant it has not yet delivered. An effective implant which is easy to insert and easy to replace would certainly revolutionize the treatment of diabetes, and given the importance of diabetes worldwide, this in itself can be expected to revolutionize healthcare.

Featured image credit: A colony of embryonic stem cell. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Stem cell therapy for diabetes appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA taxonomy of kissesStress before birthNeurology and psychiatry in Babylon

Related StoriesA taxonomy of kissesStress before birthNeurology and psychiatry in Babylon

October 30, 2014

Another Gaza war: what if the settlers were right?

Before they were evicted from their homes and forcibly removed from their communities by the Israeli government in 2005, Jewish settlers in the Gaza Strip warned that their removal would only make things worse. They warned that the front line of violence between Israelis and Palestinians would move closer to those Israelis who lived inside the Green Line. They claimed their presence provided a buffer. They said God promised this Land to the Jewish people and that they should not abandon it. They said Jewish settlement in the Gaza Strip, unlike many other places inside Israel, did not involve the destruction of Palestinian communities or the displacement of Palestinians. Israeli Jews living in Gaza predicted that life would become more dangerous for other Israelis if the government pulled out.

Indeed, that is exactly what has happened. In the southern part of Israel, previously quiet communities have found themselves at the forefront of violent conflict since the 2005 disengagement when Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza, removing its soldiers and citizens. Palestinian attacks on Israeli citizens, once aimed at the settlements in Gaza, have since turned to the communities inside the internationally recognized borders of Israel. Now, missiles are fired from Gaza into the southern towns of the Israeli periphery. While it might seem strange, this has also had some benefits for those communities. In support of those who live on the front lines, the government has reduced taxes in those towns. The train ride from some peripheral areas is now provided free of charge. People began purchasing inexpensive real estate and were able to easily commute to their jobs in center of the country. Towns like Sederot became targets of missile fire, but also began to prosper in ways they had not before. More recently, Palestinian missile fire has increased in number and in range, disrupting life for Israelis throughout the country.

The settlers might not have made public predictions about the lives of Palestinians in Gaza, but surely their situation has become markedly worse since the 2005 disengagement. So far, there have been three major military campaigns and intermittent exchanges of fire resulting in the deaths of thousands of Palestinians. The number of casualties and deaths, and the destruction of property has only increased for Gazans since the Israeli withdrawal from Palestinian territory. This might seem strange, but it was probably entirely predictable.

Armored corps operating in the Gaza Strip. Photo by Israel Defense Forces. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

Armored corps operating in the Gaza Strip. Photo by Israel Defense Forces. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.Such might have been the prediction of James Ron in Frontiers and Ghettos: State Violence in Serbia and Israel, for example, who compares state violence in Israel and Serbia. When a minority is contained within a nation-state, he explains, they may be subject to extensive policing, as has been the case for Palestinians in the West Bank, which he describes as similar to a “ghetto”, or what we might think of as a reservation, or a camp. The ghetto, he says, implies subordination and incorporation, and ghettos are policed but not destroyed.

But state violence increases when those considered outsiders or enemies of the nation are separated and on the “frontier” of the state. In the American West, for example, when the frontier was open and indigenous populations were unincorporated into the United States, they were targeted for dispossession and massacre. And, he explains, when Western powers recognized Bosnian independence in 1992, that helped transform Bosnia into a frontier, setting the stage for ethnic cleansing.

We might ask ourselves if the disengagement set up Gaza as such a frontier. If so, we might have anticipated the extreme violence that has since ensued. Then we are also left to wonder if the settlers were right. What if dismantling Jewish settlements is more dangerous for Palestinians than for Israelis?

Many of those who support the rights of Palestinians have been calling for an end to Israeli settlement and for dismantling existing settlements in Israeli Occupied Territories, in preparation for the establishment of two states for two peoples, side by side.

But what is gained if the ethno-national foundation of the nation-state necessarily leads to containment or removal of those who are not considered members of the nation? This was Hannah Arendt’s warning about the danger inherent in the nation-state formation that makes life precarious for those who are not considered part of the national group that has sovereignty. As Judith Butler so eloquently explains in Who Sings the Nation-State?: “The category of the stateless is reproduced not simply by the nation-state but by a certain operation of power that seeks to forcibly align nation with state, one that takes the hyphen, as it were, as a chain.”

If the danger lies in that hyphen as chain, then removing Jewish settlers, like demolishing Palestinian homes, is also part of a larger process of separation, a power that seeks to forcibly align a people with a territory. That separation might seem liberating; a stage on the way to independence. But partition does not necessarily lead to peace. In the case of Gaza, removing Israeli citizens might just have made it possible for increased violence. If it is true that war is only politics by other means, or politics only war, then we have to think further. The political terrain of Israel has changed. If, prior to the 2005 disengagement, there was a vibrant Left Wing opposed to settlement in the Occupied Territories, those voices have faded.

The political terrain has changed, but the foundations of the seemingly intractable conflict in Israel/Palestine have not. Those foundations lie in the normative episteme of nations and states that form the basis for international relations and liberal peacemaking. If Israel/Palestine is a struggle between two national groups for one piece of territory, then fighting for that hyphen as chain will continue and the violence, death and destruction will only increase. As evidenced in Patrick Wolfe’s Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. Writing Past Colonialism, if Israel/Palestine is a settler colonial polity, then the forces of separation required for two states should be understood as part of a foundational structure that requires elimination of the natives (Wolfe 1999). It matters little if one believes that Jews have a right to sovereignty in their homeland or if one believes the Palestinian struggle for liberation is justified. If liberation relies on the ethnic purification of territory there can be no winners.

The post Another Gaza war: what if the settlers were right? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlace of the Year 2014: the longlist, then and nowPlace of the Year 2014: behind the longlistAnnouncing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pick

Related StoriesPlace of the Year 2014: the longlist, then and nowPlace of the Year 2014: behind the longlistAnnouncing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pick

Eight facts about the waterphone

What in this galaxy is waterphone? You’ve might have not seen one, but if you’ve watched a horror or science fiction movie, chances are you’ve heard the eerie sounds of the waterphone. With Halloween around the corner and a spooky soundtrack required, I toured through Grove Music Online to learn more about the monolithic, acoustic instrument.

1. The waterphone was invented in 1967 and patented in 1975 by Richard A. Waters. It was manufactured individually to order by him (formerly under the company name Multi-Media in Sebastopol, California) so each was unique.

2. The Standard model is a stainless steel bowl resonator containing water. The dome-shaped top opens into a vertical unstopped, cylindrical tube that serves as a handle. Around the edge of the resonator are attached between 25 and 55 nearly vertical bronze rods, which (depending on the model) are tuned in equal or unequal 12-note or microtonal systems.

3. Various sizes have been produced; the earliest (‘Standard’) had a resonator 17.8 cm in diameter. Current models (‘Whaler’, ‘Bass’, and ‘MegaBass’) are constructed from flat, stainless steel pans.

4. The rods can be struck with sticks or Superball mallets or rubbed by a bow or the hands.

5. The movement of water in the resonator produces timbre changes and glissandi.

6. It has been played in a wide variety of musics, including rock and jazz, and featured in the compositions of Tan Dun and Sofia Gubaidulina.

7. It is an important element in the Gravity Adjusters Expansion Band founded by Waters in 1967.

8. It has been featured in many horror and science fiction film and television soundtracks, such as Poltergeist and The Matrix.

Headline image credit: Waterphone. Photo by Hangklang. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Eight facts about the waterphone appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn inside look at music therapyCelebrating Dylan Thomas’s centenaryReligious organizations in the public health paradigm

Related StoriesAn inside look at music therapyCelebrating Dylan Thomas’s centenaryReligious organizations in the public health paradigm

Stress before birth

Stress seems to be everywhere we turn. Much of the daily news is stressful, whether it pertains to the recent Ebola outbreak in western Africa (and its subsequent entry into the United States), beheadings by the radical Islamic group called ISIS, or the economic doldrums that continue to plague much of the developed world. Moreover, we all experience frequent stress in our daily lives. Stress can come from your job, your family, a romantic relationship, personal attacks by way of social media, or, if you’re a student, your school performance. Counselors, psychotherapists, even self-help books and other materials may help us cope with stress, but these sources don’t usually give us very much information about what is actually happening to our brain and our body when we’re stressed.

If we think about it for a moment, it becomes clear that stress is not a recent phenomenon brought about by the features of contemporary western societies. Our hominid ancestors who evolved on the African savanna were surely stressed in the course of meeting their basic biological needs of finding food and water, acquiring shelter, and keeping safe from predators. Moreover, the principal brain and endocrine (i.e. hormonal) systems that underlie the cognitive, behavioral, and physiological responses to stress are found throughout the animal kingdom, indicating that these systems arose much earlier in evolutionary history than the appearance of the first hominids. So just what are these systems and how do they work?

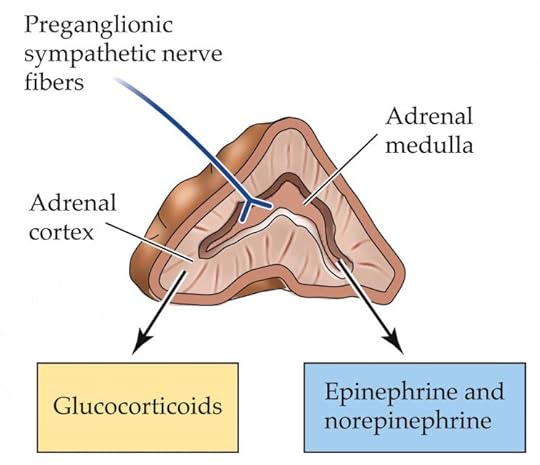

Insert drawing of adrenal gland here with the following caption: Structure of the adrenal gland, showing the outer cortex and the inner medulla along with the hormones they secrete. Reproduced from Psychopharmacology. Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior, second edition, by Jerrold S. Meyer and Linda F. Quenzer. © Sinauer Associates.

Insert drawing of adrenal gland here with the following caption: Structure of the adrenal gland, showing the outer cortex and the inner medulla along with the hormones they secrete. Reproduced from Psychopharmacology. Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior, second edition, by Jerrold S. Meyer and Linda F. Quenzer. © Sinauer Associates.A lot of research has focused on the hormonal systems that are turned on during stress. These responses are easier to access than brain responses, since researchers usually need only to obtain samples of the person’s blood, saliva, or urine to determine whether her endocrine system is showing a normal stress response or perhaps is functioning abnormally due to the effects of previous stress exposure. There are two parts to the endocrine stress response, both involving the adrenal glands. The inner part of the adrenal gland, called the adrenal medulla, rapidly secretes the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine (also called adrenalin and noradrenalin) in response to a stressor. These hormones help prepare the person for rapid physical action by elevating heart rate and blood pressure, mobilizing sugar from the liver for instant energy, and increasing blood flow to the skeletal muscles. The outer part of the adrenal gland, called the adrenal cortex, is also activated by stressors but a bit more slowly. This part of the gland secretes glucocorticoids such as cortisol, which not only works in conjunction with epinephrine and norepinephrine but also affects inflammation, immune function, and brain activity.

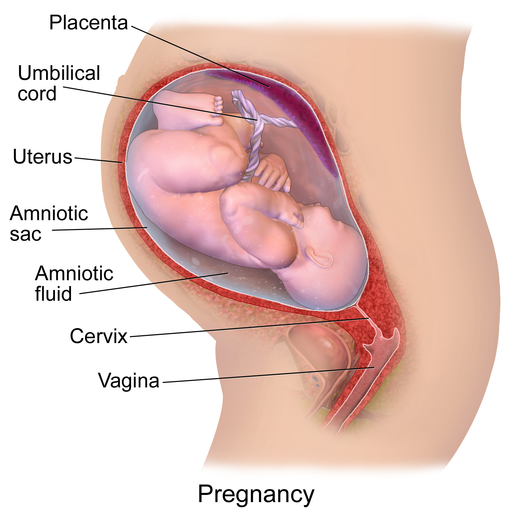

For many years, researchers focused on how stress, especially chronic stress, can damage the adult brain and body. More recently, however, it has become clear that stress may be particularly destructive during development. We now know, for example, that repeated childhood maltreatment and abuse increase the child’s vulnerability to a later onset of clinical depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. But stress can exert deleterious effects even earlier in development, namely during the prenatal period. Although the fetal adrenal glands begin to function before birth, it seems likely that stress is transmitted to the fetus mainly through maternal hormones such as cortisol. The placenta breaks down much of the mother’s cortisol before it reaches the fetus, but some of the hormone manages to get through. One example that shows how prenatal stress can adversely affect offspring development stems from a terrible ice storm that hit Québec Province in Canada in January of 1998. Three million people lost electrical power for up to 40 days, resulting in significant privation. David Laplante and colleagues at Douglas Hospital of McGill University later studied 89 five-and-a-half-year-old children whose mothers had been pregnant with them during the power outage. Children whose mothers endured the greatest hardship as a result of the storm scored noticeably lower in verbal IQ scores and in a vocabulary test than children whose mother experienced low or moderate hardship.

Late pregnancy human fetus. Illustration by Bruce Blaus. Source: Blausen.com staff. “Blausen gallery 2014”. Wikiversity Journal of Medicine. DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 20018762. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Late pregnancy human fetus. Illustration by Bruce Blaus. Source: Blausen.com staff. “Blausen gallery 2014”. Wikiversity Journal of Medicine. DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 20018762. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.While natural disasters like the Québec ice storm afford researchers the opportunity to investigate some of the deleterious effects of prenatal stress exposure, there are many limitations of such studies because the stress cannot be controlled experimentally and there are additional confounding variables such as differing postnatal experiences among the participants. To overcome some of these limitations and additionally permit a more detailed examination of behavioral, endocrine, and brain function than normally available with human participants, models of stress (including prenatal stress) have been developed for studying nonhuman primates such as rhesus monkeys. Offspring of rhesus monkeys exposed during mid-to-late pregnancy either to repeated mild stress or to pharmacological stimulation of cortisol release show behavioral and brain abnormalities that are still present at least several years later.

Young rhesus monkey, courtesy of author

Young rhesus monkey, courtesy of authorThe implication of both the human and primate research is clear. We must pay closer attention to the well-being of pregnant women in order to minimize whatever life stresses can be controlled. By so doing, we can help newborn children begin life with better prospects for their future mental and physical health.

The post Stress before birth appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA taxonomy of kissesFood insecurity and the Great RecessionFood insecurity and the Great Recession - Enclosure

Related StoriesA taxonomy of kissesFood insecurity and the Great RecessionFood insecurity and the Great Recession - Enclosure

A taxonomy of kisses

Where kissing is concerned, there is an entire categorization of this most human of impulses that necessitates taking into account setting, relationship health and the emotional context in which the kiss occurs. A relationship’s condition might be predicted and its trajectory timeline plotted by observing and understanding how the couple kiss. For instance, viewed through the lens of a couple’s dynamic, a peck on the cheek can convey cold, hard rejection or simply signify that a loving couple are pressed for time.

A kiss communicates a myriad of meanings, its reception and perception can alter dramatically depending on the couple’s state of mind. A wife suffering from depression may interpret her husband’s kiss entirely differently should her symptoms be alleviated. Similarly, a jealous, insecure lover may receive his girlfriend’s kiss of greeting utterly at odds to how she intends it to be perceived.

So if the mind can translate the meaning of a kiss to fit with its reading of the world, what can a kiss between a couple tell us? Does this intimate act mark out territory and ownership, a hands-off-he’s-mine nod to those around? Perhaps an unspoken negotiation of power between a couple that covers a whole range of feelings and intentions; how does a kiss-and-make-up kiss differ from a flirtatious kiss or an apologetic one? What of a furtive kiss; an adulterous kiss; a hungry kiss; a brutal kiss? How does a first kiss distinguish itself from a final kiss? When the husband complains to his wife that after 15 years of marriage, “we don’t kiss like we used to”, is he yearning for the adolescent ‘snog’ of his youth?

Engulfed by techno culture, where every text message ends with a ‘X’, couples must carve out space in their busy schedules to merely glimpse one another over the edge of their laptops. There isn’t psychic space for such an old-fashioned concept as a simple kiss. In a time-impoverished, stress-burdened world, we need our kisses to communicate more. Kisses should be able to multi-task. It would be an extravagance in the 21st-century for a kiss not to mean anything.

And there’s the cultural context of kissing to consider. Do you go French, Latin or Eskimo? Add to this each family’s own customs, classifications and codes around how to kiss. For a couple, these differences necessitate accepting the way that your parents embraced may strike your new partner as odd, even perverse. For the northern lass whose family offer to ‘brew up’ instead of a warm embrace, the European preamble of two or three kisses at the breakfast table between her southern softie of a husband and his family, can seem baffling.

The context of a kiss between a couple correlates to the store of positive feeling they have between them; the amount of love in the bank of their relationship. Take 1: a kiss on the way out in the morning can be a reminder of the intimacy that has just been. Take 2: in an acrimonious coupling, this same gesture perhaps signposts a dash for freedom, a “thank God I don’t have to see you for 11 hours”. The kiss on the way back in through the front door can be a chance to reconnect after a day spent operating in different spheres or, less benignly, to assuage and disguise feelings of guilt at not wanting to be back at all.

Couple, by Oleh Slobodeniuk. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Couple, by Oleh Slobodeniuk. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.While on the subject of lip-to-lip contact, the place where a kiss lands expresses meaning. The peck on the forehead may herald a relationship where one partner distances themselves as a parental figure. A forensic ritualized pattern of kisses destined for the cheeks carries a different message to the gentle nip on the earlobe. Lips, cheek, neck, it seems all receptors convey significance to both kisser and ‘kissee’ and could indicate relationship dynamics such as a conservative-rebellious pairing or a babes-in-the-wood coupling.

Like Emperor Tiberius, who banned kissing because he thought it helped spread fungal disease, Bert Bacarach asks, ‘What do you get when you kiss a guy? You get enough germs to catch pneumonia…’ Conceivably the nature of kissing and the unhygienic potential it carries is the ultimate symbol of trust between two lovers and raises the question of whether kissing is a prelude or an end in itself, ergo the long-suffering wife who doesn’t like kissing anymore “because I know what it’ll lead to…”

The twenty-first century has witnessed the proliferation of orthodontistry with its penchant for full mental braces. Modern mouths are habitually adorned with lip and tongue piercings as fetish wear or armour. Is this straying away from what a kiss means or a consideration of how modern mores can begin to create a new language around this oldest of greetings? There is an entire generation maturing whose first kiss was accompanied by the clashing of metal, casting a distinct shadow over their ideas around later couple intimacy.

Throughout history, from Judas to Marilyn Monroe, a kiss has communicated submission, domination, status, sexual desire, affection, friendship, betrayal, sealed a pact of peace or the giving of life. There is public kissing and private kissing. Kissing signposts good or bad manners. It is both a conscious and unconscious coded communication and can betray the instigator’s character; from the inhibited introvert to the narcissistic exhibitionist. The 16th-century theologian Erasmus described kissing as ‘a most attractive custom’. Rodin immortalized doomed, illicit lovers in his marble sculpture, and Chekhov wrote of the transformative power of a mistaken kiss. The history and meaning of the kiss evolves and shifts and yet remains steadfastly the same: a distinctly human, intimate and complex gesture, instantly recognizable despite its infinite variety of uses. I’ve a feeling Sam’s ‘You must remember this, a kiss is just a kiss’ may never sound quite the same again.

Headline image credit: Conquered with a kiss, by .craig. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

The post A taxonomy of kisses appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesStress before birthFive lessons from extreme placesPlato and contemporary bioethics

Related StoriesStress before birthFive lessons from extreme placesPlato and contemporary bioethics

October 29, 2014

Monthly etymology gleanings for October 2014, Part 1

It so happened that at the end of this past summer I was out of town and responded to the questions and comments that had accumulated in August and September in two posts. We have the adjectives biennial and biannual but no such Latinized luxury for the word month. Although I realized that in this case bimonthly would be misleading, I hoped that the context would disambiguate it. Let me assure our correspondents that my gleanings will keep appearing every last Wednesday until some unpredictable circumstance (for example, a sudden lack of queries: I can’t think of anything else) do us part. My bimonthly meant “gleanings for two months.”

Etymologies

Gaul, Walloon, Wallachian

Wallachian, Walloon, and Welsh share the same Germanic root, which means “foreign” (one can also see it in walnut, as well as in the family names Wallace, Welsh, and Walshe). The Anglo-Saxons called the Celts and the Romans foreigners. The element -wall in Cornwall is related to them. Gaulish is a Romanized form of the same adjective (compare ward and guard, Wilhelm and Guillaume). But one should not argue from etymological affinity to tribal or national identity. Calling some people foreigners does not say anything about their origin.

Hull gull

Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) has an entry for the word, and descriptions of the game abound, but the origin of the name remains undiscovered. My browsing has not yielded anything worth reporting. What little has been said on the subject in books on games can be found on the Internet in five minutes. The idea that hull goes back to the Old Engl. verb for “hide” (hellan ~ helian, in Modern English, rare and dialectal hele; compare German hehlen, hüllen, and their cognate -ceal in Engl. conceal, from Latin, via French) is, in my opinion, fanciful. Hull gull is known among American Indians, but in the absence of its native name nothing follows from this fact. The hully gully dance seems to have been called after the game. Some people have looked for its source in Africa, yet no facts bear out its African origin. In my experience, the nucleus of such reduplications (hugger-mugger and the like) is more often the second element; the first is then added to rhyme with it. This is especially true of the words whose first element begins with an h. Should some brave word sleuth decide to search for the etymology of hull gull, it may pay off to begin with gull. Perhaps some of our correspondents have ideas on this subject. If so, kindly don’t hide them.

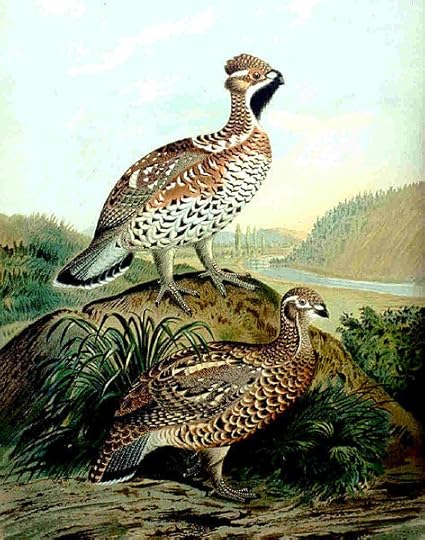

A hazel-grouse

A hazel-grouseColor words

Brown

My gratitude is due those who informed me about the origin of brown shirts in Germany. I knew most of what was said in the comments but can now state with certainty that brown had no symbolic value in the choice of that uniform. As regards the name of the hazel grouse, it indeed has a root with wide Indo-European connections. The remark on braun und blau (see the quotation from Deutsches Wörterbuch adduced by Roland Schumann) should be considered, but in such binomials a descending scale is also possible: compare Engl. black and blue.

Livid

I am sure Michael Lamb is right. It did not occur to me to consult dictionaries. The OED explains that livid with anger means “pale with anger.” However, I still wonder whether anger, rather than fear, causes pallor. In those few cases in which I heard the phrase, the speakers always meant “suffused with red.” Apparently, I err in (good) company.

One as a pronoun

One is responsible for one’s mistakes. Is this a silly sentence? In at least one opinion, it is as silly as John is responsible for John’s mistakes. I am afraid I disagree. One, our correspondent points out, is not only an indefinite pronoun but also a noun, a circumstance ignored by grammarians. However, grammarians have always been aware of the nature of one. In the United States, grammar is seldom taught today (where some watered down elements of it remain, grammar has been replaced by the less offensive term structure; I cannot vouch for the rest of the English-speaking world), but those of us who did study this allegedly-devoid-of-fun subject at school have heard about the parts of speech (nouns, adjectives, verbs, and the rest). The division of the vocabulary into parts of speech is a minor catastrophe. For instance, adverbs often resemble a trashcan (what is not a noun or an adjective finds refuge there, and, to add to the confusion, nouns and adjectives in oblique cases tend to be “adverbialized”). Numerals fare even worse: we provide a list of them (one, two, three, etc.) and say: “This is your part of speech.” Is twice a numeral or an adverb? Twelve is a numeral, while dozen is a noun. Is threescore a numeral or a noun? Sixty is certainly a numeral. In the Old Germanic languages, the words for one, two, three, and four could be declined (as they still are in Icelandic) and belonged to the same classes as nouns; yet we call them numerals. All this is common knowledge. One is the worst offender, because, despite its meaning, in Old Germanic it had a plural form and sometimes meant “only.” Modern Engl. ones shows how natural that plural sounds, while once is a petrified genitive.

My next point concerns usage. John is responsible for John’s mistakes is unnecessary and even silly, because his, instead of John’s, would refer to the subject quite clearly. But one has no correlate, hence the trouble. One is responsible for his (her) mistakes is embarrassing, because one is neither a man nor a woman. Their is safe and politically correct, but one is singular, while their is plural. To be sure, those who say when a student comes, I never make them wait will find the correlation one/their unobjectionable, and let them enjoy their usage (“every man in his humor”). In addition to those variants, we can say either one is responsible for one’s mistakes (logical but perhaps inelegant) or rephrase the sentence (all of us are responsible for our mistakes). “John” is doing better: he pays the price for his folly, just as “Mary” rues her missteps. While speaking English, one occasionally hits the wall, and there is no help for it.

Come one, come all

Come one, come allI wrote my response before Michael Lamb’s comment appeared. There was no need for me to change anything in my text, and “at this point of time,” as so deplorably many people say and write, I invite our correspondents to read our “polemic” and express their opinion: come one, come all.

Disagreements over strategy, or a maid of all work: over

Some prepositions succeed in ousting all their competitors. Henry W. Fowler, the author of the immortal book Modern English Usage, wrote with contempt about those who say as to, because they are too lazy to think of for, about, and their synonyms. I have a dim recollection that in one of my old posts I discussed over as an example of an evil invasive species. Recently, Walter Turner has sent me a list of such overdone phrases from the most respectable British and American newspapers. Some of them are offered below for the wise to be aware. “Egypt jails nine men over sex assaults”; “Moscow faces bank curbs over new public-sector projects” (= because of? in connection with?); “Journalists face jail over spy leaks”; “Cameron ambushes Labour over tax plans”; “Cameron criticized over plans to knight Tory reshuffle victims”; “X warns Y over boozy night out,” and many more. This virus, like all viruses, knows no borders. Take note and think it over.

I have something to say about the Indo-European names of fruits, the phrase in brown study, the origin of Viking, and about the ever-green subject of English spelling but will do so next Wednesday.

Image credits: (1) Hazel grouse. Naumann, Naturgeschichte der Vögel Mitteleuropas, Band VI, Tafel 8 – Gera, 1897 digitale Bearbeitung : Peter v. Sengbusch. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Marx Super Circus Tent Side 2 Inside Detail 1. Photo by Ed Berg. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for October 2014, Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 2

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 2

The Catholic Supernatural

From eighteenth century Gothic novels to contemporary popular culture, the tropes and sacred culture of Catholicism endure as themes in entertainment. OUP author Diana Walsh Pasulka sat down with The Conjuring (2013) screenwriters Patrick Wilson and Vera Farmiga in The Conjuring. New Line Cinema. © 2013 Warner Bros Entertainment.

Diana Walsh Pasulka: A few years ago, Carey, you coined the term “The Religious Supernatural” to differentiate what you were doing from other screenwriters who wrote movies about the supernatural. Why designate it “religious?”

Carey Hayes: I coined the term to identify a certain framework, and, I suppose, to suggest a history. Today there is a lot of focus in popular culture on the supernatural or the paranormal. It is almost all secular. In the past, the supernatural and paranormal occurred within a worldview that allowed for the supernatural but within a religious framework. People had tools like prayers to deal with the supernatural, which, you have to admit, is scary. We wanted, in our movies, to return to that. We thought that, in many ways, religion deals with the big questions, and the supernatural is usually a scary thing that interrupts daily life and causes people to think about the big questions. So, we wanted to pair the two, religion and the supernatural, and remind audiences that this is, ultimately, what scary movies are about: ultimate questions about life.

Diana Walsh Pasulka: Are you ever frightened by what you write about?

Chad Hayes: We’re not afraid when we write and produce movies about the supernatural. But our research frightens us!

Carey Hayes: Right! It is frightening because some of this is supposed to be true, or based on events that are true.

Diana Walsh Pasulka: I wondered about that. Part of the appeal of your movies, and other movies like it such as The Exorcist, is that they play on the ambiguity of fiction and non-fiction, or the realism of your subject. The Blair Witch Project (1999) is a great example of the play on realism. The movie was presented as recovered footage of an actual university student project. I was in Berkeley, California for the pre-release of that movie, and I couldn’t get tickets for three days because the lines outside of the theaters were so long. When I finally got to see the movie members of the audience were wondering, is this real? Of course, we knew that it wasn’t, but we were also intrigued that it was presented as real. That definitely contributed to its popularity. The marketing campaign for that movie was unique at the time, too, in that they emphasized the question of the potential realism of the movie.

Chad Hayes: We purposely look for stories that are based on true events. We do that for this very reason: because people can relate. They can Google the story and see that maybe its folklore, or its real, but it is out there and is an experience for other people. So that contributes, no doubt, to the scare factor.

Diana Walsh Pasulka: Do you think this also has something to do with the appeal of the Catholic aesthetic, like the use of real Catholic sacred objects — the sacramentals, the crucifix, and the robes of the priests?

Chad Hayes: Absolutely. Ed and Lorraine Warren are practicing Catholics. Ed has passed away, but Lorrain still attends a Catholic Mass almost every day. That part of The Conjuring is based on her real Catholic practice. We were in contact with Lorraine throughout the writing of the movie and we included the objects that she and Ed actually used, like the sacramentals, the blessed objects, and holy water. My Catholic friends tell me that most Catholics don’t use these objects in their daily lives, but then they aren’t exorcizing demons, are they?

Diana Walsh Pasulka: I suppose not!

The post The Catholic Supernatural appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive lessons from extreme placesSix classic tales of horror for HalloweenHow well do you know the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984?

Food insecurity and the Great Recession

While food insecurity in America is by no means a new problem, it has been made worse by the Great Recession. And, despite the end of the Great Recession, food insecurity rates remain high. Currently, about 49 million people in the U.S. are living in food insecure households. In a recently-released article in Applied Economics Policy and Perspectives my co-authors, Elaine Waxman and Emily Engelhard, and I provide an overview of Map the Meal Gap, a tool that is used to establish food insecurity rates at the local level for Feeding America (the umbrella organization for food banks in the United States).

For 35 years, Feeding America has responded to the hunger crisis in America by providing food to people in need through a nationwide network of food banks. Today, Feeding America is the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization—a powerful and efficient network of 200 food banks across the country. You can learn more about food insecurity rates in America by listening to the below podcast:

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/aepp_36.03.mp3

What are the state-level determinants of food insecurity? What is the distribution of food insecurity across counties in the United States? How do the county-level food insecurity estimates generated in Map the Meal Gap compare with other sources? Along with reviewing Map the Meal Gap and finding out the answers to these questions, we discuss ways that policies can and are being used to reduce food insecurity in the United States.

Headline image credit: Supermarket trolleys, by Rd. Vortex. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Food insecurity and the Great Recession appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFood insecurity and the Great Recession - EnclosureMarital transfers and the welfare of womenCorporate short-termism, the media, and the self-fulfilling prophecy

Related StoriesFood insecurity and the Great Recession - EnclosureMarital transfers and the welfare of womenCorporate short-termism, the media, and the self-fulfilling prophecy

Five lessons from extreme places

Throughout history, some people have chosen to take huge risks. What can we learn from their experiences?

Extreme activities, such as polar exploration, deep-sea diving, mountaineering, space faring, and long-distance sailing, create extraordinary physical and psychological demands. The physical risks, such as freezing, drowning, suffocating or starving, are usually obvious. But the psychological pressures are what make extreme environments truly daunting.

The ability to deal with fear and anxiety is, of course, essential. But people in extremes may endure days or weeks of monotony between the moments of terror. Solo adventurers face loneliness and the risk of psychological breakdown, while those whose mission involves long-term confinement with a small group may experience stressful interpersonal conflict. All of that is on top of the physical hardships like sleep deprivation, pain, hunger, and squalor.

What can the rest of us learn from those hardy individuals who survive and thrive in extreme places? We believe there are many psychological lessons from hard places that can help us all in everyday life. They include the following.

Cultivate focus.

Focus – the ability to pay attention to the right things and ignore all distractions, for as long as it takes – is a fundamental skill. Laser-like concentration is obviously essential during hazardous moves on a rock face or a spacewalk. Focus also helps when enduring prolonged hardship, such as on punishing polar treks. A good strategy for dealing with hardship is to focus tightly on the next bite-sized action rather than dwelling on the entire daunting mission.

The ability to focus attention is a much-underestimated skill in everyday life. It helps you get things done and tolerate discomfort. And it is rewarding: when someone is utterly absorbed in a demanding and stretching activity, they experience a satisfying psychological state called ‘flow’ (or being ‘in the zone’). A person in flow feels in control, forgets everyday anxieties, and tends to perform well at the task in hand. The good news is that we can all become better at focusing our attention. One scientifically-proven method is through the regular practice of meditation.

Value ‘knowhow’

Focus helps when tackling difficult tasks, but you also need expertise – high levels of skills and knowledge – to perform those tasks well. Expertise underpins effective planning and preparation and enables informed and measured judgements about risks. In high-risk situations experts make more accurate decisions than novices, who may become paralysed with indecision or take rapid, panicky actions that make things worse.

Expertise also helps people in extreme environments to manage stress. Stress occurs when the demands on you exceed your actual or perceived capacity to cope. An effective way of reducing stress, in everyday life as well as extremes, is by increasing your ability to cope by developing high levels of skills and experience.

Developing expertise requires hard work and persistence. But it’s worth the investment – the dividends include better assessment of risk, better decision-making, and less vulnerability to stress.

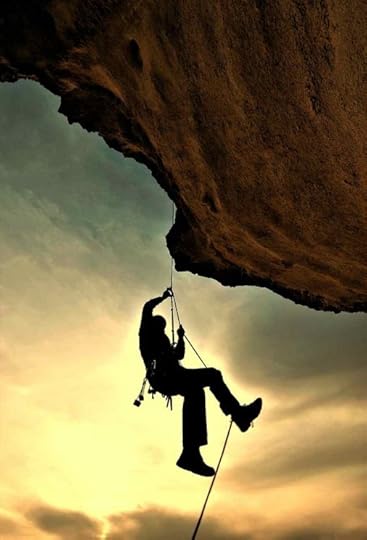

Climber, by aatlas. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Climber, by aatlas. Public Domain via Pixabay.Value sleep.

Getting enough sleep is often difficult in extreme environments, where the physical demands can deprive people of sleep, disrupt their circadian rhythms, or both.

Bad sleep has a range of adverse effects on mental and physical wellbeing, including impairing alertness, judgment, memory, decision-making, and mood. Unsurprisingly, it makes people much more likely to have accidents.

Many of us are chronically sleep deprived in everyday life: we go to bed late, get up early, and experience low-quality sleep in between. Most of us would feel better if we slept more and slept better. So don’t feel guilty about spending more time in bed.

Experts in extreme environments often make use of tactical napping. Research has shown that napping is an effective way of alleviating the adverse consequences of bad sleep. It’s also enjoyable.

Be tolerant and tolerable.

Adventures in extreme environments often require small groups of people to be trapped together for months at a time. Even the best of friends can get on each other’s nerves under such circumstances. Social conflict can build rapidly over petty issues. Groups split apart, individuals are ostracised, and simmering tensions may even explode into violence.

When forming a team for an extreme mission, as much emphasis should be placed on team members’ interpersonal skills as on their specialist skills or physical capability. Research shows that team-building exercises – though often mocked – can be an effective way of enhancing teamwork.

Effective teams are alert to mounting tensions. Individuals keep the little annoyances in perspective and respect others’ need for privacy. To survive and thrive in demanding situations, people must learn to be tolerant and tolerable. The same is true in everyday life.

Cultivate resilience

Extreme environments are dangerous places where people endure great hardship. They may suffer terrifying accidents or watch others die. Such experiences can be traumatic and, in some cases, cause long-term damage to mental health.

But this is by no means inevitable. Research has shown that many individuals emerge from extreme experiences with greater resilience and a better understanding of their own strengths. By coping with life-threatening situations, they become more self-confident and more appreciative of life.

Resilience is a common quality in everyday life. We tend to underestimate our own ability to cope with stress, and overestimate its adverse consequences. Some stress is good for us and we should not try to avoid it completely.

Featured image credit: Mount Everest, by tpsdave. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Five lessons from extreme places appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSix classic tales of horror for HalloweenHow well do you know the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984?A composer’s thoughts on re-presentation and transformation

Related StoriesSix classic tales of horror for HalloweenHow well do you know the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984?A composer’s thoughts on re-presentation and transformation

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers