Oxford University Press's Blog, page 743

November 5, 2014

Does chronic occupational stress cause brain damage?

During the last decade, Western societies have been facing increasing reports about a new work-related phenomenon. It affects healthy, productive, and highly functional individuals typically working long hours for many years without a normal weekend recovery. These persons complain of stereotyped symptoms, including memory and concentration problems, sleeplessness, profound fatigue, and a feeling of being emotionally drained, which they attribute to occupational stress. This condition is frequently misinterpreted as depression because of partially shared symptoms. However, it is seldom helped by anti-depressant medications and seems to represent a separate construct. The underlying mechanisms are unknown, and there is an ongoing discussion whether the described disabilities are caused by stress, if they could be associated with cerebral changes, or if we are confronted with a new medical condition.

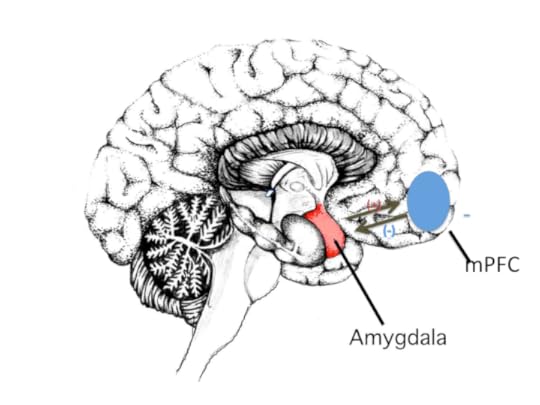

Psychosocial stress, initially defined by Lazarus and Folkman (1987), is thought to result from an “imbalance between demands and resources.” An adequate coping with stress stimuli involves specific networks in the brain, which encompass the structures processing emotion (primarily the amygdala), and parts of the frontal lobe that are involved in cognitive modulation of emotion (the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).

Brain, (viewed from side) showing mid-brain structures. The amygdala (marked in red), which is the first relay in the processing of stress stimuli, has tight and reciprocal connections to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC, marked in blue). Combined inhibitory and excitatory, so called top-down modulation, of the amygdala is necessary for normal stress coping. We believe that repetitive stress stimulation of the amygdala may lead to damage of the mPFC via targeted neurotransmitter release from the amygdla to mPFC, impaired stress modulation. This, in turn, causes further amygdala stimulation of the mPFC, leading to a cortical thinning in this region (as shown in figure 1), as well as the described cognitive symptoms.

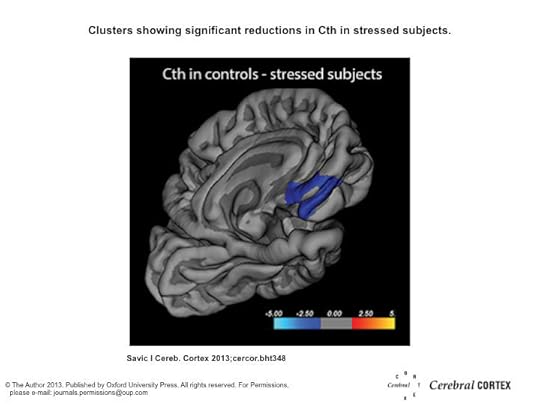

Brain, (viewed from side) showing mid-brain structures. The amygdala (marked in red), which is the first relay in the processing of stress stimuli, has tight and reciprocal connections to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC, marked in blue). Combined inhibitory and excitatory, so called top-down modulation, of the amygdala is necessary for normal stress coping. We believe that repetitive stress stimulation of the amygdala may lead to damage of the mPFC via targeted neurotransmitter release from the amygdla to mPFC, impaired stress modulation. This, in turn, causes further amygdala stimulation of the mPFC, leading to a cortical thinning in this region (as shown in figure 1), as well as the described cognitive symptoms.We hypothesized that repeated, chronic stress could lead to damage of the brain areas which modulate stress perception, leading to a vicious cycle with impaired ability to cope with stress and a further facilitation of stress perception. To measure whether such damage could exist, we used measurements of the cortical thickness and of the volumes of specific brain structures known to be involved with the processing of psychosocial stress stimuli, including the amygdala. These measures were carried out using brain MRIs compared between 40 subjects reporting symptoms of chronic occupational stress (on average 38 years old) and 40 matched controls. We found that in stressed subjects, there was a significant thinning of the mesial prefrontal cortex (see below). Furthermore, in the frontal cortex, which is essential for our cognitive functions, the normal thinning effect of age was more pronounced than in the controls. In addition, the amygdala volumes were increased in subjects with occupational stress and the increase was positively correlated with the degree of perceived stress.

Blue cluster shows significant reductions in Cth in stressed subjects. The calculation is corrected for age and gender. The projection of cerebral hemispheres (MR images of the Freesurfer atlas) is standardized. Scale is logarithmic and shows –log10(P). Warm colors indicate positive contrasts (higher values in stressed subjects), cool colors negative contrasts (lower values in stressed subjects). Reproduction from Savic I. 2013, Cerebral Cortex bht348.

Blue cluster shows significant reductions in Cth in stressed subjects. The calculation is corrected for age and gender. The projection of cerebral hemispheres (MR images of the Freesurfer atlas) is standardized. Scale is logarithmic and shows –log10(P). Warm colors indicate positive contrasts (higher values in stressed subjects), cool colors negative contrasts (lower values in stressed subjects). Reproduction from Savic I. 2013, Cerebral Cortex bht348.Together, these data suggest that chronic occupational stress may indeed be associated with specific changes in brain regions involved with the processing and modulation of stress stimuli.

Are the observed changes a cause to the increased stress sensitivity (and hence, the described symptoms), or an effect of excessive occupational stress?

The cross sectional study design used does not permit conclusions about the causality, but considering that stress perception was correlated with structural enlargement of the amygdala, it is plausible to believe that we are dealing with an effect of stress.

Are the changes reversible?

Our very preliminary results from follow-up investigations after treatment suggest that the observed cerebral changes may be reversible, which further argues that they might have been caused by stress.

Although several issues remain to be done for a better comprehension of the described condition, the already available findings indicate that it may well be a stress-related illness. Of note is that the locations of the observed cerebral changes in several aspects correspond to the locations of structural changes detected through MRI in persons suffering from other stress-related disabilities, such as post-traumatic disorder or early life traumas. Therefore, one may hypothesize that psychosocial stress affects our brains in a rather stereotyped manner, regardless of the underlying cause, and that cerebral changes occur not only in response to exposure to extreme and life threatening situations, but could also be an effect of accumulated everyday stress. Extreme occupational stress needs to be coped with at an early level, and if becoming associated with maladaptive coping effort and strategy, the result may be a drastically reduced recuperation, sleep problems, fatigue, and subsequently cognitive disability.

Headline image credit: Brain. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Does chronic occupational stress cause brain damage? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat do rumors, diseases, and memes have in common?Mapping historic US electionsEarly blues and country music - Enclosure

Related StoriesWhat do rumors, diseases, and memes have in common?Mapping historic US electionsEarly blues and country music - Enclosure

A history of Bonfire Night and the Gunpowder Plot

The fifth of November is not just an excuse to marvel at sparklers, fireworks, and effigies; it is part of a national tradition that is based on one of the most famous moments in British political history. The Gunpowder Plot itself was actually foiled on the night of Monday 4 November, 1605. However, throughout the following day, Londoners were asked to light bonfires in order to celebrate the failure of the assassination attempt on King James I of England. Henceforth, the fifth of November has become known as ‘Bonfire Night’ or even ‘Guy Fawkes Night’ – named after the most posthumously famous of the thirteen conspirators. Guy Fawkes became the symbol for the conspirators after being caught during the failed treason attempt. For centuries after 1605, boys creating a cloaked effigy – based on Guy Fawkes’ disguised appearance in the Vaults at the House of Lords – have been asking for “a penny for the Guy”.

Below is a timeline that describes the events leading up to the failed Gunpowder Plot and the execution of Guy Fawkes and his fellow conspirators. If you would like to learn more about Bonfire Night, you can explore the characters behind the Gunpowder Plot, the traditions associated with it, or simply learn how to throw the best Guy Fawkes Night party.

Feature image credit: Guy Fawkes, by Crispijn van de Passe der Ältere. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A history of Bonfire Night and the Gunpowder Plot appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Oxford DNB at 10: biography and contemporary historyA welcome from David Cannadine, the new editor of the Oxford DNBThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biography

Related StoriesThe Oxford DNB at 10: biography and contemporary historyA welcome from David Cannadine, the new editor of the Oxford DNBThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biography

I miss Intrade

Autumn is high season for American political junkies.

Although the media hype is usually most frenetic during presidential election years, this season’s mid-term elections are generating a great deal of heat, if not much light. By October 13, contestants in 36 gubernatorial races had spent an estimated $379 million on television ads, while hopefuls in the 36 Senate races underway had spent a total of $321 million.

For those addicted to politics, newspapers and magazines have long provided abundant, sometimes even insightful coverage. During the last hundred years, print outlets have been supplemented by radio, then television, then 24/7 cable TV news. And with the growth of the internet, consumers of political news now have access to more analysis than ever.

One analytical tool that the politics-following public will not have access to this year is Intrade, an on-line political prediction market. Political prediction markets work very much like financial markets. Investors “buy” a futures contract on a particular candidate; if that candidate wins, the contract pays a set amount (typically $1); if the candidate loses, the contract becomes worthless. The price of candidates’ contracts vary between zero and $1, rising and falling with their political fortunes—and their probability of winning. You can see a graph of Obama and Romney contracts in the months preceding the 2012 election here.

Organized political betting markets have existed in the United States since the early days of the Republic. According to a 2003 paper by Rhode and Strumpf, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries wagering on political outcomes was common and market prices of contracts were often published in newspapers along with those of more conventional financial investments. Rhode and Strumpf note that at the Curb Exchange in New York, the total sum placed on political contracts sometimes exceeded trading in stocks and bonds.

Political betting markets became less popular around 1940. Betting on election outcomes no doubt continued to take place, but it was a much less high-profile affair.

Modern political prediction markets emerged with the establishment in 1988 of the Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM), a not-for-profit small-scale exchange run by the College of Business at the University of Iowa. The IEM was created as a teaching and research tool to both better understand how markets interpret real-world events and to study individual trading behavior in a laboratory setting. The IEM usually offers only a few contracts at any one time and investors are allowed to invest a relatively small amount of money. As of mid-October, the Iowa markets—like the polls more generally—were predicting that the Republicans will gain seats in the House and gain control of the Senate.

Wooden Ballot Box, by the Smithsonian Institution. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wooden Ballot Box, by the Smithsonian Institution. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.An important feature of political prediction markets—like financial markets—is that they are efficient at processing information: the prices generated in those markets are a distillation of the collective wisdom of market participants. A desire to harness the market’s ability to process information led to an abortive attempt by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in 2003 to create the Policy Analysis Market, which would allow individuals to bet on the likelihood of political and military events—including assassinations and terrorist attacks–taking place in the Middle East. The idea was that by processing information from a variety disparate sources, monitoring the prices of various contracts would help the defense establishment identify hot-spots before they became hot. The project was hastily cancelled after Congress and the public expressed outrage that the government was planning to provide the means (and motive) to speculate on—and possibly profit from–terrorism.

Another, longer-lived—and for a time, quite popular–prediction market was Intrade.com. This Dublin-based company was established in 1999. At first, it specialized in sports betting, but soon expanded to include an extensive menu of political markets. During recent elections, Intrade operated prediction markets on the presidential election outcome at the national level, the contest for each state’s electoral votes, individual Senate races, as well as a number of other political races in the US and overseas. Thus, Intrade offered a far variety of betting options than the IEM.

Intrade was forced to close last year when the US Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) filed suit against it for illegally allowing Americans to trade options (by contract, the IEM secured written opinions in 1992 and 1993 from the CFTC that it would not take action against IEM, because of that market’s non-profit, educational nature). The CFTS’s threat to Intrade’s largest customer base very quickly led to a dramatic drop-off in visitors to the site, which subsequently closed. Alternative off-shore betting markets have entered the political markets (e.g., Betfair), but their offerings pale by comparison with those formerly offered by Intrade and are probably too small at present to spur the CFTC to action.

I regret the loss of Intrade, but not because I used their services—I didn’t. Given the federal government’s generally hostile view toward internet gambling, I felt it was prudent to abstain. Plus, having placed a two-pound wager on a Parliamentary election with a bookmaker when I lived in England many years ago convinced me that an inclination to bet with the heart, rather than the head, makes for an unsuccessful gambler.

No, I miss Intrade because it provided a nice summary of many different political campaigns. Sure, there are plenty of on-line tools today that provide a wide array of expert opinion and sophisticated polling data. Still, as an economist, I enjoyed the application of the mechanisms usually associated with financial markets to politics and observing how political news generated fluctuations in those markets. No other single source today does that for as many political races as Intrade did.

Feature image credit: Stock market board, by Katrina.Tuiliao. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post I miss Intrade appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2014 shortlist: Vote for your pickFull-circle in the Middle East?Food insecurity and the Great Recession

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2014 shortlist: Vote for your pickFull-circle in the Middle East?Food insecurity and the Great Recession

November 4, 2014

Learning to love democracy: A note to William Hague

British politics is currently located in the eye of a constitutional storm. The Scottish independence referendum shook the political system and William Hague has been tasked with somehow re-connecting the pieces of a constitutional jigsaw that – if we are honest – have not fitted together for some time. I have written an open letter, encouraging the Leader of the House to think the unthinkable and to put ‘the demos’ back into democracy when thinking about how to breath new life into politics.

Dear William (if I may),

I do hope the Prime Minister gave you at least a few minutes warning before announcing that you would be chairing a committee on the future constitutional settlement of the UK. Could you have ever hoped for a more exciting little project to sort out before you leave Parliament next May? Complex problems rarely have simple answers and this is why so many previous politicians have failed to deal with a whole set of questions concerning the distribution of powers and the respective roles of various sub-sets of both politicians and ‘publics’. The timetable you have been set is – how can I put it – demanding and those naughty people in the Labour Party have taken their bat and ball home and are refusing to play the constitutional game.

I’m sure you know how to sort all of this out but I just thought you might like to know that amongst all the critics and naysayers who claim the British constitution is in crisis I actually think that a crisis might be just what we need. Not a crisis in terms of burning cars and riots in the streets but a crisis in terms of ‘creative destruction’ and the chance for a new way of looking at perennial problems. What’s more – as the Scottish referendum revealed – there is a huge amount of latent democratic energy amongst the public. From Penzance to Perth and from Cardigan to Cromer the public is not apathetic or disinterested about politics but they feel disconnected from a London-based system that is remote in a number of ways.

The reasons for this sense of disconnection are numerous and complex but as a constitutional historian you will know better than most people that British democracy has evolved throughout the centuries with a deep animosity to public engagement. The (in)famous ‘Westminster Model’ that we imposed on countries around the world was explicitly elitist, centralized and to a great extent insulated from public pressure. These features and values – as Scotland revealed – are now crumbling under the weight of popular pressure that will not accept their legitimacy in the twenty first century. But as I said, this should be interpreted as a positive opportunity for re-imagining, for re-connecting and for breathing new life into the system.

The question is how to deliver on this potential for positive change in a way that takes the people with you?

William Hague, 2010, by U.S. Department of State. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Hague, 2010, by U.S. Department of State. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Now I’m no Vernon Bogdanor or Peter Hennessy and so writing notes to members of the Cabinet is not a common task but could I just offer three little ideas that might help smooth the path you have been asked to map out?

First and foremost, please ignore Russell Brand.

Secondly, make sure all your officials are also ignoring Russell Brand.

Finally, the trick to moving forward is thinking about constitutional reform not as being like moving pieces on a chessboard or as a zero-sum game in which a ‘win’ for one side means a ‘loss’ for the other. This traditional way of thinking about constitutional politics has served us badly and the aim has to be to turn the problem upside-down and inside-out in a way that creates new opportunities. This means starting with the people – with the demos – and viewing the constitutional puzzle not like a board game but as a multi-level game that suddenly focuses attention on the existence of connections or bonds.

The real challenge is not a lack of political interest amongst the public (indeed the appetite for meaningful engagement is huge) but a lack of ways of drawing upon the upsurges of bottom-up civic energy that keep exploding in various forms – from the off-line Occupy Movement to the on-line growth of ‘clicktivism’ – but to which the ‘traditional’ political institutions seem to offer no answers. Put slightly differently, the public no longer believes that traditional forms of political engagement are actually meaningful. In this context the promises of populist movements suddenly become attractive and Mr Farage gorges on a feast of anti-politics. The focus of your committee on a new constitutional settlement might therefore adopt a quite different approach to all those committees, commissions and inquiries that have gone before you by focusing on what I term ‘nexus politics’. That is, on the institutions and processes that can re-connect the spontaneous and the local and the single issue with the pre-existing institutional framework in a way that positively channels, absorbs and welcomes civic energy and activism. In short, British politics must learn to love democracy in a manner that is quite different to the one-night stand of five-yearly elections.

The problem is that despite the Prime Minister’s pledge on the 19 September to ensure “wider civic engagement… we will say more about this in the coming days”, the days have ticked by but the plans for public engagement remain unclear. What we are experiencing is best characterized as a (classically British top-down) ‘constitutional moment’ in which the existing elite decide what they think is best for the public. However, it has not yet evolved into a truly ‘democratic moment’ in which the public decide for themselves. My note – to bring things to a close – is therefore a simple plea for the Creation of a Citizens Assembly on Constitutional Reform that takes party politics out of discussions about the future and puts power in the power of the people. What a radical thought…

Yours truly,

Matt

P.S. Did I mention avoiding Russell Brand at all costs?

Feature image credit: Union Jack and Scotland, by Julien Carnot. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Learning to love democracy: A note to William Hague appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Dis-United KingdomFull-circle in the Middle East?Corruption, crime, and scandal in Turkey

Related StoriesThe Dis-United KingdomFull-circle in the Middle East?Corruption, crime, and scandal in Turkey

Corruption, crime, and scandal in Turkey

In December 2013, Turkish authorities arrested the sons of several prominent cabinet ministers on bribery, embezzlement, and smuggling charges. Investigators claimed that the men were contributing members in a conspiracy to illicitly trade Turkish gold for Iranian oil gas (an act which, among other things, violates the spirit of United Nations’ sanctions targeting Tehran). The scheme purportedly netted a vast fortune in proceeds in the form of dividends and bribes. Among those suspected of benefiting from the trade was Prime Minister (now President) Tayyip Erdoğan and members of his family. The firestorm from this scandal was initially so furious many feared that Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party would not survive its implications. Yet as of this September, the investigation into this scandal has all but come to an end. The officials involved in propagating and executing the investigation have all been dismissed or transferred. Consequently, virtually all charges related to the case have been dropped.

Most of the analysis of this scandal has focused upon the political implications of the arrests and the subsequent purges of Turkey’s national police force. Events since December have indeed underscored the intense levels of strife within Turkey’s governing institutions as well as the growing authoritarian tendencies of the country’s ruling party. Yet Turkey’s “oil for gold” corruption scandal also illuminates fundamental, yet long-standing, aspects of the relationship between prominent illicit trades and the country’s politics.

Turkey’s black market, by all accounts, is exceeding large and highly lucrative. As a country sitting at a major intersection in global commerce, Turkey acts as a spring, valve and spigot for multiple illicit industries. Weapons, narcotics and undocumented migrants, as well as contraband carpets, petroleum, cigarettes, and precious metals all pass in and through the country’s borders on a regular basis. Official statistics on cigarette smuggling offer a few hints of the extent of smuggling in and out of Turkey. According to Interior Ministry sources, Turkish seizures of smuggled cigarettes grew fourteen fold between 2009 and 2012 (with ten million cigarettes seized in 2009 and over 145 million in 2012). In January of this year, Bulgarian customs officials purportedly confiscated fourteen million cigarettes illegally imported from Turkey in one seizure alone. The numbers of arrests for cigarette smuggling has also climbed precipitously, with over 4000 people arrested in 2009 and over 24000 arrests in 2012.

Ankara Views taken by Peretz Partensky. CC BY-SA 2.0 by Flickr

Ankara Views taken by Peretz Partensky. CC BY-SA 2.0 by FlickrOrganized crime takes other forms in Turkey. Criminal networks, builders, and lawmakers have been known to violate laws governing land sales, usage, building safety, and contracting. Bribes and kickbacks to government officials and regulators historically have been essential elements in the rapid building projects undertaken throughout the country for much of the last century. Charges levied against the managers of Istanbul’s Fenerbahce soccer club stand as an example of the match fixing and extortion scandals that have rocked professional sports in Turkey in recent years. Gangsters and extortionists, known as kabadayı, have been counted among Turkey’s most noted and notorious figures in the public spotlight. All in all, organized criminal trades have generated an untold number of fortunes for a select few and have provided a subsistence living for an even larger number of average citizens for a very long time in Turkey.

If Tayyip Erdoğan and his family did glean a great fortune as a result of illicit doings (which some reports claim to amount to total in the tens of millions of dollars), Turkey’s president joins a fairly sizable host of Turkish politicians who have benefited from organized criminal trades. American officials in the 1950s, for example, secretly suspected that noted members of Adnan Menderes’ Democratic Party had protected major Turkish heroin traffickers. During the 1970s, at least four members of the Turkish Grand National Assembly were official charged with attempting to transport heroin abroad. Other politicians from this era, including one-time Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan, were unofficially suspected of engaging in the drug trade but never charged. Accusations of theft and corruption especially dogged the governments of the tumultuous 1990s. Tansu Ciller, the country’s first female prime minister, was implicated in organized criminal activity both before and after she was first elected to office. Tayyip Erdoğan’s JDP came to power in 2002 with the promise of bringing discipline and respectability to politics. Yet even as recent as last year, a regional JDP chairman was implicated in trading in heroin in the province of Van. The revelations of December 2013 now has many in Turkey convinced that the JDP is as dirty and corruptible as any of the parties that had preceded it.

Erdoğan’s ability to deflect last year’s corruption charges has not put the specter of smuggling and corruption to rest. Local media reports and other studies suggest that the Syrian civil war has stimulated a surge in smuggling along Turkey’s southern border. It is now estimated that fuel, cigarette, and cell phone smuggling has risen by 314%, 135%, and 563% respectively since the war began. The initial efforts to arm and maintain resistance groups in Syria were deeply indebted to Turkey’s smuggling trade. As smuggling continues, it is clear that some groups have attempted to tax trade into and out of Syria (al-Nusrah, for example, purportedly levies a fee of 500 Syrian lira for every barrel of fuel that crosses the border). What this means for the present and future of Turkey’s government is not entirely clear. Suggestions that Ankara has allowed for the passage of large numbers of foreign fighters into Syria has cast doubt over the country’s police and customs officials stationed on its borders (particularly after the official purges earlier this year). Trading schemes and corruption allegations like those revealed in December may yet again manifest themselves considering what international watchdogs call Turkey’s “grey” status as a state with loose embezzlement and money laundering controls. Whether these trends will dent the image of Tayyip Erdoğan or upend JDP control over Turkey remains to be seen.

Headline Image: Turkish flag photo by Abigail Powell. CC BY-NC 2.0 by Flickr

The post Corruption, crime, and scandal in Turkey appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMapping historic US electionsUmbrellas and yellow ribbons: The language of the 2014 Hong Kong protestsFull-circle in the Middle East?

Related StoriesMapping historic US electionsUmbrellas and yellow ribbons: The language of the 2014 Hong Kong protestsFull-circle in the Middle East?

Nuclear strategy and proliferation after the Cold War

On 4 November 1994, the United Nations Security Council formally endorsed the so-called “Agreed Framework,” a nuclear accord discussed for years but negotiated intensively from September to October 1994 between The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea) and the United States.

The framework had four main parts:

The nations would cooperate to replace the DPRK’s graphite-moderated reactors and related facilities with light-water reactor (LWR) power plants.

The United States and DPRK would work toward full normalization of political and economic relations.

The United States and the DPRK pledged to seek peace and security on a nuclear-free Korean peninsula.

The United States and the DPRK agreed to work together to strengthen the international nuclear non proliferation regime.

In light of recent events these are eye-catching promises. They were then as well. As The New York Times reported, the agreement was a remarkable event. The four key tenets of the accord, even to the jaundiced eye of a seasoned diplomat seemed symbolic of the post-Cold War era. However, according to the Times, the announcement of the agreement “kept secret many details of how the accord will be put into effect.”

It is unclear whether the momentum for the framework continued despite the secrecy or because of details hidden from view. Within two weeks of the agreement, the Security Council took up the cause and numerous nations were on board (many not yet privy to some more secret aspects of the Framework). The UN proclaimed support of North Korea’s decision to freeze its current nuclear program and to comply with a safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Yet perhaps such international approbation did more harm than good, because North Koreans objected to how the agreement was playing out symbolically. The UN statement seemed to emphasize only North Korea’s responsibilities under the framework agreement and not the reciprocal obligations of the United States and of South Korea.

North Korean leaders aimed for their nation to be perceived not as a rogue state being brought into line, but as holding the United States and its allies accountable in an agreement with mutual responsibilities. The agreement itself, as events unfolded, seemed promising enough. Within another two weeks, by 11 November 1994, the IAEA arranged to send inspectors, and soon thereafter United States and North Korean scientists and policymakers announced preliminary protocols regarding storage issues for over 8,000 spent fuel rods. South Korean diplomats pushed back, seeking security guarantees, but eventually bought into the agreement. By 18 November, according to Reuters, the United States, South Korea, and Japan agreed to lead an international consortium to finance more than $4 billion in construction and maintenance costs for light-water reactors in North Korea.

To many observers, the Agreed Framework of 1994 augured a new chapter in non-proliferation, tailored to the post-Cold War era. Despite difficult negotiations regarding the compromise framework and the international consortium, it seemed to be a real success.

Why such a promising framework collapsed bears further scrutiny and has profound implications for the future.

North Korea: By Roman Harak. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

North Korea: By Roman Harak. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The end of the Cold War did not eliminate the challenges of nuclear weapons and strategy. Far from it. Recognizing the new nuclear and strategic landscape, the Clinton Administration tried to align nuclear policy with new circumstances. “A wide-ranging and thorough bottom-up study conducted by the Pentagon during 1993,” writes Joseph Siracusa, “identified a number of key threats to United States national security. Foremost among them was the increased threat of proliferation of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction.”

Clinton’s strategy for dealing with obvious threats, such as a resurgent Russia and the need to keep track of former Soviet stockpiles, materials, technologies, and experts, was to pursue new agreements that addressed the concerns of individual states, while strengthening the existing Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Just months after the agreement with North Korea, for example, the United States, Britain, and Russia worked with Ukraine to send its inherited Soviet-era nuclear arsenal to Russia, persuading it to join the NPT in return for security guarantees. It seemed that new accords, adjusted to the new era, could be reached to foreclose future proliferation. Notorious cases of international trafficking in materials, technology, expertise, such as the transnational network of Pakistani scientist A.Q. Khan, served as a reminder that proliferation required constant attention. Through diplomatic channels, military threats, and economic coercion, the Clinton Administration sought to work with allies to alleviate nuclear threats in such places as Libya, Iraq, and North Korea. Subsequent administrations hoped for productive results into the early 21st century despite instability in the Balkans, Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere.

So, what changed?

First, on the Korean peninsula tensions persisted. “Pyongyang’s continued failure to come into full compliance with its IAEA safeguard obligations,” according to Daniel Poneman, “appeared to threaten the project.”

Second, US policymakers and many among their allies in the international community lost sight of the importance of perception for a country like North Korea. Third, American leaders too easily assumed that “unipolar” power, stability, and unilateralism could go hand-in-hand. US political rhetoric, especially related to nuclear and WMD negotiations and in sharp contrast to international economic agreements, abandoned the sense of mutual obligation and reciprocity that had been essential to Cold War and immediate post-Cold War diplomacy. Instead, American leaders tended to emphasize the pacts as treaties “to be enforced” rather than ones in which nations “shared,” which often resulted in resentment and retrenchment.

In terms of the Agreed Framework, Siracusa argues that the agreement collapsed because in 2002 President George W. Bush refused to honor the two most crucial precepts of the Agreement: helping to build light-water reactors and moving to normalize relations. North Korean diplomatic brinksmanship did not help, but rejecting direct negotiations was clearly a mistake. Pushing for new “six-party talks on North Korea, in which the two Koreas, China, Russia, Japan, and the United States were jointly to reach a solution with Kim Jong-il’s Stalinist regime” may have added too many voices and competing interests. Similarly, new incentives seemed to be aligning to make states like North Korea, in the wake of 9/11 seek nuclear power status as a bulwark against more overt attempts at regime change.

No longer obliged to the Framework, on 9 October 2006, North Korea exploded a nuclear bomb in a tunnel complex at Punggye, in the far north of the country, which made it the ninth nation in history to become a nuclear power.

In his 2002 State of the Union Address President Bush inveighed against all members of the “Axis of Evil.” Of the three “members” of this purported axis, Iraq was first to be invaded, in large part based on the premise that weapons of mass destruction were located there but no nuclear threshold had yet been reached. Iran has been attacked largely via sanctions and covert operations and to date there have been no recent military assaults on the nation’s nuclear facilities.

In contrast to Iraq and Iran, the already isolated, impoverished, and heavily sanctioned nuclear North Korean state, a nation that the New York Times deemed “too erratic, too brutal, and too willing to sell what it has to have a nuclear bomb,” has retained a high nuclear barrier to direct military action. Indeed, the Times in 2006 ruled out “a military strategy” entirely. The differential treatment of North Korea and Iraq, one nuclear-armed and the other not, has left strategists in Iran with mixed messages from the United States.

Even as nuclear stockpiles have been dramatically reduced, the new nuclear strategic world seems to be one of state proliferation. On the one hand “any confrontation between nuclear armed states runs the risk of escalating to the use of nuclear weapons, whether by inadvertence, accident, or bad decision-making,” reasons Tilman Ruff, co-chair of the International Steering Group and Australian Board member of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. On the other hand, without those weapons, states and groups out of favor with the United States, Russia, or other “great” powers may find themselves far more susceptible to coercion or even attack. In turn, with nuclear weapons as a credible threat, states may be able to negotiate better deals, even if those accords ultimately might result in the relinquishing the very weapons themselves.

The ability of the impoverished North Korean state to stand up to the United States and its allies in recent years remains a product of its nuclear deterrent. The Russian annexation of Crimea followed by Russian-backed separatist attacks and revolution in the Ukraine pinpoint a similar counterfactual lesson: would a nuclear Ukraine be able to stand up more effectively to Russia? Kazakhstan and Belarus, which also gave up their Soviet era stockpiles in the mid-1990s, are confronting this question today.

There is an unfortunate logic for states to develop nuclear weapons in the 21st century, even if they have no intention of using them. Despite the end of the Cold War, the concept of deterrence may have more legitimacy than ever before. Potential combatants around the world now see the development of weapons of mass destruction, particularly nuclear, as a means of neutralizing the hegemonic capacities of the United States and other major military and economic powers. The stubborn, persistent spread of nuclear weapons – in large part because of the apparent strategic-diplomatic need for them – in a multi-polar world is more complicated and more problematic than most would have predicted in November 1994. In no small measure the changes of the last two decades mark a moment of diminished US leadership and what Andrew Bacevich has depicted as the limits of American power. The United States, in the wake of 9/11 and in attempting to combat the spread of WMDs, has not exactly made the world safe for an NPT by all-too-often abandoning the interest- and mutual security-based discussions of the 1990s.

The post Nuclear strategy and proliferation after the Cold War appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCoded letters reveal an illicit affair and a woman of substanceMapping historic US electionsOf wing dams, tyrannous bureaucrats, and the rule of law

Related StoriesCoded letters reveal an illicit affair and a woman of substanceMapping historic US electionsOf wing dams, tyrannous bureaucrats, and the rule of law

Mapping historic US elections

Today is Election Day in the United States, and we’ve mapped out some of the stories behind historic American elections. Explore America’s presidential and Congressional history, from Abraham Lincoln’s first Senatorial race in 1858 to George W. Bush’s hotly-contested victory against Al Gore in 2000. We sourced our facts and figures from The Republicans: A History of the Grand Old Party by Lewis L. Gould and articles from the Journal of American History, Sociology of Religion, and the Journal of Church and State. Some of the contests featured here are widely known, others less so, but all of the locations on our map offer a piece of electoral history.

Heading image: The County Elections by George Caleb Bingham. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Mapping historic US elections appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Lame Duck” session of Congress should pass Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness ActAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2014 shortlist: Vote for your pickUmbrellas and yellow ribbons: The language of the 2014 Hong Kong protests

Related Stories“Lame Duck” session of Congress should pass Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness ActAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2014 shortlist: Vote for your pickUmbrellas and yellow ribbons: The language of the 2014 Hong Kong protests

Music teachers on Facebook: separating the wheat from the chaff

I just reviewed yet another “hot off the press” piano composition. It was posted on Facebook by someone I don’t know – either as a person or by reputation. It looks good, but that is only because note-writing software has become so easy-to-use that anyone with the most basic knowledge can quickly crank out a “could-have-been-published” looking piece.

This particular piece doesn’t sound very good. It is mismatched. The notes themselves are at an upper-beginning level, yet it’s written with a complicated key signature and accidentals only an advanced student could understand. There are notational errors. Yet, I know that many unknowing teachers will print it off and rush it to their unfortunate students before the day is out without knowing better.

My professional life is better because of my Facebook presence that I control from the comfort of my hilltop home in a small town. I have made connections with numerous wonderful teachers I might not have met otherwise. I have discovered new books and interesting repertoire and also have contributed my two cents when I felt called to do so. I recognize, however, that I have been thrown without rank or file, onto a massive heap of piano teachers. Perhaps I stand out because of my reputation, but probably not. Up until recent times, the gatekeepers of quality have included respected publishers and one’s reputation through professional associations. Facebook’s format equalizes everyone regardless of accomplishment or education. There is no gatekeeper here.

I work in an unregulated industry as an independent music teacher in the United States. No professional degrees, training, or licensing of any kind is necessary to start up a studio. One simply needs to hang a sign and gather willing students. While this has been a longstanding issue in our field, recent trends in social media have combined with advances in technology to make everyone look equally valid on the screen. It is impossible to discern from a glance whether one’s content is senseless, stellar, or stolen.

With the ease of creating websites, music teachers have jumped into the writing arena. No credentials are needed to set up a site, write something, and post links in every professional music group on Facebook. The volume is overwhelming and often includes blog posts that are only copies or rewrites of someone else’s work. From appearances on screen, there is no way to sort the good from the bad and unethical.

Likewise, when questions are posed in groups, anyone can answer. There are no algorithms measuring the veracity or usefulness of an answer, or even the level of competence of the person responding. Running parallel to this is an anti-educational drumbeat that attempts to elevate those who have no formal education in their field to the highest level of achievement simply because they have passion for what they do. “People don’t know what they don’t know” as the old saying goes, and on Facebook no one seems bashful in rushing to confirm the truth of this statement. On the ubiquitous blue and white screen we all stand as equals — or at least we look like we do.

Adding to this are the wearisome writers who purport that “having fun” should supersede the steady and sturdy learning that is required to gain success in any field. Certainly, there is nothing wrong with fun, but students subjected to a form of “teaching” with only pleasant, mindless activities devoid of content or educational merit will never see a reasonable level of achievement — certainly not enough for them to gain entry into a respectable music school.

Untrained teachers whose main goal is keeping kids happy are falling into this trap by droves by using well-marketed, but substandard and mostly self-published literature that is woefully lacking in sound pedagogy. There is a bandwagon mentality of rushing to download the latest composition or method, which leads to a sense of belonging to the coolest group in high school – I mean – on Facebook. But, when one method advertises that “Our teachers do not need to possess advanced playing skills, prior teaching experience or a music degree. They must simply love to play the piano…” where is it all headed?

Parents would never allow their children to study math with someone who simply had a passion for adding up numbers, yet many sign them up for music lessons without researching the qualifications of the instructors or the soundness of the materials. The books are slick, the websites dynamic, and the appearances on Facebook omnipresent. But does the emperor actually have any clothes?

With 8,000 piano teachers in one group and several thousand in others, it is an unmanageable task to separate the wheat from the chaff. I suspect that these groups will have short shelf lives moving forward as their members begin to realize the unreliability of the information and the questionable value of material shared. What this backlash will create is yet to be determined, but I trust it will be a positive, quality-driven platform. For me, this can’t happen soon enough.

Image courtesy of Deborah Rambo Sinn

The post Music teachers on Facebook: separating the wheat from the chaff appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn person online: the human touch“Lame Duck” session of Congress should pass Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness ActAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2014 shortlist: Vote for your pick

Related StoriesIn person online: the human touch“Lame Duck” session of Congress should pass Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness ActAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2014 shortlist: Vote for your pick

November 3, 2014

Umbrellas and yellow ribbons: The language of the 2014 Hong Kong protests

Late September and October 2014 saw Hong Kong experience its most significant political protests since it became a Special Administrative Region of China in 1997. This ongoing event shows the inherent creativity of language, how it succinctly incorporates history, and the importance of context in making meaning. Language is thus a “time capsule” of a place.

China, which resumed sovereignty over Hong Kong after it stopped being a British colony in 1997, promised universal suffrage in its Basic Law as the ‘ultimate aim’ of its political development. However, Beijing insists that candidates for Hong Kong’s top job, the chief executive, must be vetted by an electoral committee made up largely of tycoons, pro-Beijing, and establishment figures. The main demand of the protesters is full democracy, without sifting candidates through a selection mechanism. Protesters want the right to nominate and directly elect the head of the Hong Kong government.

‘Lennon Wall’, Hong Kong. Photo by Dr Jennifer Eagleton. Do not use without permission.

‘Lennon Wall’, Hong Kong. Photo by Dr Jennifer Eagleton. Do not use without permission. The protests are a combination of movements. For instance, the “Occupy Central with Love and Peace” movement is a civil disobedience movement that calls on thousands of protesters to block roads and paralyze Hong Kong’s financial district if the Beijing and Hong Kong governments do not agree to implement universal suffrage according to international standards.

The humble umbrella has become the predominant symbol of the 2014 protests – largely because of its use as protection against police pepper spray. I’m sure you will have seen the now-iconic photograph of a young student holding up umbrellas while clouds of tear gas swirl around him. Thus, the terms “umbrella movement” or “umbrella revolution” came into being.

Yellow or “democracy yellow” as the colour became known, became the symbolic colour of the 2014 protests. As the protests wore on, yellow ribbons have been tied to fences, trees, lapels and Facebook profile pictures as indicators of solidarity with the “umbrella movement”.

How yellow and the crossed yellow ribbon became the symbol of the campaign for democracy in Hong Kong is unclear. The yellow ribbon often signifies remembrance (“Tie a yellow ribbon round that ole oak tree”, a hit song from 1973 about a released prisoner hoping that his love would welcome him back). Perhaps it relates to the fact that in 1876, during the U.S. Centennial, women in the suffrage movement wore yellow ribbons and sang the song “The Yellow Ribbon”. Interestingly, one political party in Hong Kong’s uses the suffragette colours (green, white, and violet) as its political colours.

‘Wanted! Traitor, 689 CY Leung’, Hong Kong, Photo by Dr Jennifer Eagleton. Do not use without permission.

‘Wanted! Traitor, 689 CY Leung’, Hong Kong, Photo by Dr Jennifer Eagleton. Do not use without permission. From previous colour revolutions, we know that colour is significant (Beijing saw it as a separatist push, and the interchangeable use of “umbrella movement” and “umbrella revolution” did not help). Historically, in imperial times only the emperor could wear yellow. Nobles and commoners did so on pain of death. Yellow has now become a colour for the masses.

A blue ribbon movement also arose, signifying support for the police and against the action of the occupiers; the “blue ribboners” were also known as the “anti-occupiers”. Currently, Hong Kong society seems divided between the pro-occupiers and the anti-occupiers. Subsequently, there has been massive “unfriending” of people on Facebook. Thus arose a new verb: “to go blue ribbony”; as in “my friend said the group chat [FB] has gone blue ribbony so she left.”

Numbers have always been important in Hong Kong’s recent history. In 1984, with the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the year 1997 became important as that was the date of day Hong Kong “reverted” to Chinese sovereignty. The first opportunity to ask for universal suffrage was 2007 (denied), and then 2012 (also denied).

“689” is the “the number that explains Hong Kong’s upheaval” (quipped The Wall Street Journal). Invoked constantly in the streets and on social media, “689” is the protesters’ nickname for Hong Kong’s leader. The chief executive is elected by a 1,200 member Election Committee made up mostly of elite, pro-Beijing individuals after first being nominated by that committee. C.Y. Leung, the current chief executive, was elected by 689 members of that committee. This small circle election is at the heart of protesters’ frustrations, so they use “689” as an insult that emphasizes Leung’s illegitimacy. When they chant “689, step down!” they indict Mr. Leung along with the Beijing-backed political structure that they see threatening their city’s autonomy and freedoms. There is an expression “689 冇柒用” (there is no 7 in 689), where “柒” means “7” and “7冇柒用” means “(he is) no fucking use.” Interestingly, “689” could be read as “June 1989”, the time of the Tiananmen protests in Beijing.

Jennifer’s post-it note, Hong Kong. Photo by Dr Jennifer Eagleton. Do not use without permission.

Jennifer’s post-it note, Hong Kong. Photo by Dr Jennifer Eagleton. Do not use without permission. In addition to protest songs such as ‘Umbrella’ by Rihanna (naturally), ‘Do you hear the people sing’ from Les Miserables, and John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’, just to name a few, a very mundane ditty served as a tool of antagonism. This was the song “Happy Birthday”. Employing the happy birthday tactic was used by protesters when others shouted abuse at them. Singing “happy birthday” (sàangyaht faailohk, in Cantonese) to opponents, which served to annoy and disorientate them no end.

Chinese characters are made up of components called ‘radicals’. After the now iconic photograph of a young student holding up umbrellas while being tear-gassed, an enterprising individual came up with the following character扌傘, a combination of two ‘radicals’: 手 for “hand” → becoming 扌 on the left and the character for “umbrella” (傘) literally, a hand raising an umbrella. The definition for this character is to “to protest and persevere with peace and rationality until the end”, explaining that “with the radical ‘hand’, the word symbolizes the action of opening an umbrella”. The character ultimately has the meaning of “withstanding, supporting and not giving up the faith”.

The protests in Hong Kong are an ongoing phenomenon. The outpouring of linguistic and semiotic creative has been breath-taking.

Feature image credit: Hong Kong Protests, by Leung Ching Yau Alex. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Umbrellas and yellow ribbons: The language of the 2014 Hong Kong protests appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3Linguistic necromancy: a guide for the uninitiatedA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 3Linguistic necromancy: a guide for the uninitiatedA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2

“Lame Duck” session of Congress should pass Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act

There is a reason that Congress’s post-election meetings are called “lame duck” sessions. They often aren’t pretty. Senators and representatives not returning to Congress (because they retired or were defeated for re-election) may not have strong incentives to legislate responsibly. Senators and representatives who will be part of the new Congress starting in January may feel that the lame duck session is an imposition on them since they will be returning to Washington in the new year.

Nevertheless, it is sometimes possible for “lame duck” convocations of Congress to be productive. Some observers, for example, thought that the legislative session following the 2010 election was constructive. Among other accomplishments, that session of Congress abolished Don’t Ask-Don’t Tell and extended President Bush’s tax cuts – though, of course, opponents of those decisions would have preferred that Congress hadn’t legislated on these matters.

Can the “lame duck” congressional session following the 2014 election be productive? In the hope that it can be, I suggest that the 113th Congress enact in its final days the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act, previously known as the Telecommuter Tax Fairness Act.

The Multi-State Tax Worker Tax Fairness Act has been introduced in the House by Representatives Himes, DeLauro, and Esty as H.R. 4085. In the Senate, the Act has been introduced as S. 2347 by Senators Blumenthal and Murphy.

The Act is aimed at the pernicious tax practice by which New York (and other states) impose income taxes on nonresident telecommuters for days such telecommuters work at their out-of-state homes and never set foot in the Empire State. New York’s extraterritorial taxation results in double taxation of nonresident telecommuters as New York taxes the income earned on these days while the state in which the telecommuter lives and works legitimately taxes this day also since the home state is providing public services to the telecommuter on the day she works at home.

Sunrise at the George Washington Bridge. Photo by Anthony Quintano. CC BY 2.0 via quintanomedia Flickr.

Sunrise at the George Washington Bridge. Photo by Anthony Quintano. CC BY 2.0 via quintanomedia Flickr. Telecommuting is growing because, in a modern economy, it can entail significant benefits. Telecommuting extends job opportunities to individuals for whom traditional commuting is difficult, for example, the disabled, parents of small children, persons who live far from major employment centers. Telecommuting is also good for the environment, reducing the carbon footprints of employees who spend some of their work days at home and need not physically commute to work on those days.

Our concerns about Ebola reinforce the benefits of telecommuting. In an earlier time, a firm combating contamination simply had to shut its operations. Today, modern technology – the internet, email, cell phones, social media – can instead permit individuals to work and communicate with each other from their homes.

The benefits of interstate telecommuting explain why a diverse coalition supports the Multi-State Tax Worker Fairness Act to avoid double state income taxation of telecommuters on their days they work at home. Among the groups supporting the Act are the American Legion, the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, the National Taxpayers Union, The Small Business & Entrepreneurship Council, the Association for Commuter Transsportion, The Military Spouse JD Network, and the Telework Coalition.

It is, in short, anomalous for New York to double tax the income of nonresident telecommuters on the days such telecommuters work at their out-of-state homes and never enter the Empire State. New York engages in this double taxation throughout the country. In one instructive case, New York taxed Mr. Manohar Kakar of Gilbert, Arizona on the income he earned working at home in the Grand Canyon State. New York engages in such double taxation despite the long-term costs to New York of chasing from its borders firms which embrace interstate telecommuting. Thus, the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act would be good, not just for telecommuting, but for New York itself by encouraging firms which rely on out-of-state telecommuters to stay in the Empire State.

The upcoming “lame duck” session of Congress might fit the dominant pattern of post-election convocations of the House and Senate which accomplish little. But maybe not. If members of the 113th Congress choose to spend their final days in office productively, a productive place to start would be the Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act. Passing the Act would be good for the country by making state income tax systems safe for interstate telecommuting.

The post “Lame Duck” session of Congress should pass Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFull-circle in the Middle East?The ethics of a mercenaryOf wing dams, tyrannous bureaucrats, and the rule of law

Related StoriesFull-circle in the Middle East?The ethics of a mercenaryOf wing dams, tyrannous bureaucrats, and the rule of law

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers