Oxford University Press's Blog, page 740

November 11, 2014

Seven common misconceptions about the Hebrew Bible

Everyone talks about the Bible, though few have read it cover to cover. This is not surprising—some sections of the Bible are difficult to understand without a commentary, others are tedious, and still others are boring. That is why annotated Bibles were created—to help orient readers as they read through the Bible or look into what parts of it mean. For those who have not read the Bible cover-to-cover—and even for many who have—here are some common misconceptions about the Hebrew Bible.

1. The Ten Commandments are the most important part of the Bible.

No biblical text calls them the Bible’s most important part. Various prophetic texts such as Ezekiel 18 summarize righteous behavior, but most of these do not refer to the Ten Commandments. In fact, the English term “Ten Commandments” is a misnomer from a Jewish perspective, since in the Jewish enumeration, “I am the LORD your God…” is the first divine utterance in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, and it is not a commandment at all. Thus, Jews prefer to call these the Decalogue, “the ten sayings,” which reflects the Hebrew aseret hadevarim (Exodus 24:38; Deuteronomy 4:13; 10:4).

2. We know what the original text of the Bible is.

Like all texts transmitted in antiquity, the Bible in its earliest stages of transmission was fluid. Scribes changed books that became part of the Bible accidentally and on purpose; this is now clear from evidence of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

3. The Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament are different names for the same books.

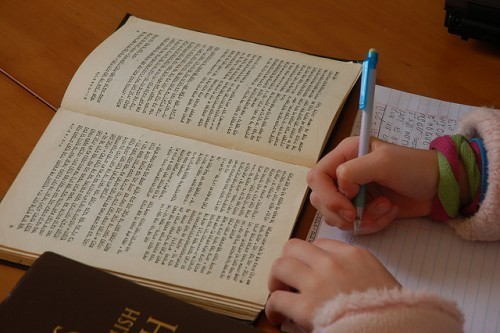

The Jewish Hebrew Bible and the Protestant Old Testament contain the same books, but in a different order—and order matters. The Catholic Old Testament is larger than the Jewish Hebrew Bible and the Protestant Old Testament. It contains the Apocrypha—select Jewish Hellenistic [Greek] Writings such as Sirach, Tobit, and Maccabees—and in two cases, Esther and Daniel, the Catholic book is larger than the Hebrew book, containing material found in the Greek texts of these works, but not in the Hebrew. Photo by David King. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

Photo by David King. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

4. We know the order of the biblical books.

Different religious groups have different orders to the Bible. Christians typically divide the Old Testament into four sections (Law [=Torah], historical books, wisdom and poetic books, prophetic books), while Jews divide the Hebrew Bible into three sections: Torah, Nevi’im [prophets] and Ketuvim [writings]. Both of these ways of ordering biblical texts probably reflect different ancient Jewish orders that ultimately helped to define Jewish versus Christian identity. In addition, Jewish manuscripts show many different orders of the final section, Ketuvim, and the Babylonian Talmud notes an order of Nevi’im that is different than the more commonly used.

5. Everything in a prophetic book is by that prophet.

Many prophetic books contain titles or superscriptions, as in Jeremiah 1:1-3: “The words of Jeremiah son of Hilkiah, one of the priests at Anathoth in the territory of Benjamin. The word of the LORD came to him in the days of King Josiah son of Amon of Judah, in the thirteenth year of his reign, and throughout the days of King Jehoiakim son of Josiah of Judah, and until the end of the eleventh year of King Zedekiah son of Josiah of Judah, when Jerusalem went into exile in the fifth month.” However, we never have the autographs of individual prophets, and often their disciples and others added material to early forms of prophetic books, in the names of the prophet himself!

6. The Bible is history.

The modern concept of history, judged by whether or not it gets the facts right, is by and large a modern conception. In the past, all peoples told stories set in the past for a variety of reasons, e.g. to entertain, to enlighten, but rarely to recreate what actually happened. Archaeologists have uncovered many cases where the biblical account disagrees with the archaeological account, or with what we might know from other ancient Near Eastern texts.

7. All of the Psalms are by King David.

About half of the psalms in Psalms contain the word ledavid, “to/of David,” in their first sentence. But many do not. Some are anonymous, while others are explicitly attributed to other figures such as Asaph (50, 73-81). We are not even sure how ledavid should be translated—does it mean to attribute authorship to David, or might it mean “in the style of David”? Furthermore, none of the psalms reflects tenth century Hebrew, the Hebrew of the period in which David was purported to have lived, and several psalms refer to events long after that period (see e.g. Psalm 126:1). In fact, scholars do not attribute any of Psalms to King David. And at least in Jewish tradition, attributing all of the Psalter to David is not dogma, and several medieval scholars acknowledge the existence of later psalms.

Headline image credit: By Alexander Smolianitski CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Seven common misconceptions about the Hebrew Bible appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRemembrance DayTop four high profile cases in Intellectual Property lawMeeting and mating with our ancient cousins

Related StoriesRemembrance DayTop four high profile cases in Intellectual Property lawMeeting and mating with our ancient cousins

Making leaders

Dwight D. Eisenhower described leadership as “the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because he wants to do it.” Eisenhower was a successful wartime general and president. What made him successful? It was not a full head of hair and a fit physique, two of the physical traits of a CEO. What made him an unsuccessful university president? Was it luck or skill, or his social interactions with those he led?

There are many theories on what makes a leader effective, where effective leaders go, and whether leaders are born or created, but little empirical work. We cannot run a field experiment to study leadership of an organization in a high-stakes setting. Empirical tests of leadership theories have to come from quantitative studies of leaders and organizations, but large, longitudinal datasets on CEOs and companies are rare. A unique longitudinal data set on Union Army soldiers augmented with information on the regiment level provides a testing ground for leadership theories. This sample (available at uadata.org), created from men’s army records and linked to their census records, is the most comprehensive longitudinal database in economic history. It has been used to study the economics of aging (Costa 1998) and the role that social capital plays in people’s decisions (Costa and Kahn 2008). The data contain information on men’s promotions and demotions, their jobs during the war, their socioeconomic and demographic information at enlistment, and their jobs and locations after the war.

Who became a leader and what made leaders effective? The more able, i.e. the literate and men who were in higher status occupations, were more likely to become officers. So were the tall and the native-born. There were benefits to being an officer – higher pay and lower odds of death, both on and off the battlefield. Game theoretic models of leader effectiveness have emphasized that one way to elicit effort from followers is to lead by example. Although on average commissioned officers did not imperil themselves in battle, when they did, it was an effective strategy in creating a cohesive fighting unit. Company desertion rates were lower for companies in which the regimental battlefield mortality of commissioned officers relative to enlisted men was higher.

After the war leaders moved to where their talent would have the highest pay-off, as predicted by economic models of sorting. The former sergeants and commissioned officers were more likely than privates to move to larger cities which provided higher wages and greater diversity in the dominant economic activity of the time, manufacturing. Even men who started in low status occupations in cities were able to climb the occupational ladder.

Are leaders created or born? The Army, and a large management literature, stresses that leaders have character, presence, and intellectual capacity. In contrast, economic theory emphasizes the management skills that can be learned. Union Army soldiers who missed being promoted because casualty rates were relatively low in their companies were likely to be in a large city after the war compared to men who were promoted, suggesting that in the long-run leaders are created. One of the skills learned in the army may have been to be a generalist. Sergeants and commissioned officers with more than strict military tasks while in the army were more likely to be in large cities.

A Civil War context for testing theories of personnel economics may be unusual. The 150th anniversary of the Civil War has focused more on historical research and re-enactments. But if a stress test of theories is their explanatory ability in very different contexts, academic personnel economics does very well.

Headline image credit: Field Band of 2nd R.I. Infantry. Photo by Mathew Brady. War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer. Brady National Photographic Art Gallery. US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Making leaders appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInnovation and safety in high-risk organizationsWhat could be the global impact of the UK’s Legal Services Act?Remembrance Day

Related StoriesInnovation and safety in high-risk organizationsWhat could be the global impact of the UK’s Legal Services Act?Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day is a memorial day observed in Commonwealth of Nations member states since the end of the First World War to remember those who have died in the line of duty. It is observed by a two-minute silence on the ’11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month’, in accordance with the armistice signed by representatives of Germany and the Entente on 11 November, 1918. The First World War officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. In the UK, Remembrance Sunday occurs on the Sunday closest to the 11th November, and is marked by ceremonies at local war memorials in most villages, towns, and cities. The red poppy has become a symbol for Remembrance Day due to the poem In Flanders Fields, by Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae.

You can discover more about the history behind the First World War by exploring the free resources included in the interactive image above.

Feature image credit: Poppy Field, by Martin LaBar. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Remembrance Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesArmistice Day: an interactive bibliographyInnovation and safety in high-risk organizationsReading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall

Related StoriesArmistice Day: an interactive bibliographyInnovation and safety in high-risk organizationsReading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall

Armistice Day: an interactive bibliography

Today is Armistice Day, which commemorates the ceasefire between the Allies and Germany on the Western Front during the First World War. Though battle continued on other fronts after the armistice was signed “on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month” of 1918, we remember 11 November as the official end of “the war to end all wars.”

In honor of the Great War, the Oxford Bibliographies team has created this interactive map, a visual bibliography of critical moments, battles, people, technology, and other elements that defined the spirit of the times across continents. Explore the trenches, navigate the front-lines, and track troop movements while gaining scholarly insights into this crucial period, from the outbreak of the War to its conclusion and lasting effects.

Note: This map may not be a completely accurate geographical portrayal, but it is intended to depict historical facts pertaining to the “Great War” and the countries and regions involved.

Featured image credit: Battle of Broodseynde [sic] Ridge. Troops moving up at eventide. Men of a Yorkshire regiment on the march. Ernest Brooks. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Armistice Day: an interactive bibliography appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFurphies and Whizz-bangsThe Road to YpresThe peace of Utrecht and the balance of power

Related StoriesFurphies and Whizz-bangsThe Road to YpresThe peace of Utrecht and the balance of power

November 10, 2014

Top four high profile cases in Intellectual Property law

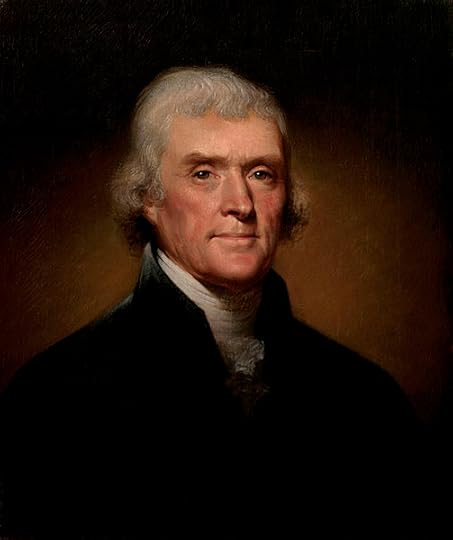

Thomas Jefferson is often quoted as remarking; “he who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.” His sentiments, while romantic, do not necessarily express a view that many companies, authors, and artists would agree with when it comes to protecting their intellectual property today. For businesses and individuals alike, it has become of increasing importance to defend expressions of creative ideas with trademarks, patents and copyrighting, especially in the digital age where sharing and reproducing images, music, text and art has become so easy and prevalent. Intellectual property law aims to protect artistic output and the expression of ideas, whilst maintaining an environment where creativity can still blossom. However, even some of the world’s biggest names in business have been caught up in intellectual property cases that have not only made world news, but have come to define how we view our intellectual property rights. Here is a run-down of some of the highest profile cases where companies and individuals have gone to court to protect their intellectual property:

A&M Record Inc v Napster Inc

In 2000, one of the most famous cases in intellectual property law was taken to the U.S. Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit, when a group of major record labels took on Napster, Inc. The music file-sharing company, set up by then 18-year old Northeastern University student Shawn Fanning and his partner Sean Parker, was a revolutionary piece of sharing software, which allowed users to share any number of music files online. At its peak the software had around 20 million users sharing files peer-to-peer. A&M Records, along with a list of 17 other companies and subsidiaries accused Napster of copyright infringement, for allowing users to search and download MP3 files from other users’ computers. Rock band, Metallica and hip hop star Dr Dre also filed separate cases against the sharing software company. These cases led to a federal judge in San Fransisco ordering Napster to close its free file-sharing capacities. After the judge’s decision, the company eventually declared bankruptcy before re-emerging as a paid online music service, while German Media Corporation Bertelsmann AG ended up paying $130 million in damages to the National Music Publisher Association, after propping Napster up during its financial decline. This case is remembered as a defining case of the 21st century, as it was one of the first to address the impact peer-to-peer file-sharing online could have on copyright.

Official Presidential portrait of Thomas Jefferson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Official Presidential portrait of Thomas Jefferson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Baigent & Leigh v Random House Group Ltd

The enigmatic story of Jesus’ fathering of a child with Mary Magdalen, and in doing so creating a bloodline that exists to this day, is not just a fictional tale that exists in Dan Brown’s bestselling book, The Da Vinci Code. It has also been the subject of deep historical research carried out by Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh who, along with author Henry Lincoln, wrote the non-fiction work The Holy Blood and The Holy Grail. Baigent and Leigh took issue with Brown’s novel, claiming that the storyline was borrowed from their historical research. After a lengthy court case against Random House Group (who also happen to have published the claimants’ book), the two authors lost their copyright infringement case. The judge ruled that while six chapters of The Da Vinci Code took much of their narrative from Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln’s research, Brown was not guilty of copyright infringement, since the ideas and historical facts were not protected by copyright. After a failed appeal in 2001, the two claimants had to pay legal bills of approximately £3 million.

Kellogg Co. v National Biscuit Co.

In a landmark 1938 case, world famous cereal brand Kellogg bested their rivals, the National Biscuit Company, over the manufacturing of a shredded wheat product which the National Biscuit Company claimed presented unfair competition to one of their products. The claimant objected to Kellogg’s use of the term “shredded wheat” to market their cereal, adding that there was too much of a similarity between Kellogg’s “pillow-shaped” cereal and their own shredded wheat product. Kellogg was allowed to continue their manufacturing of shredded wheat under this name and shape by Judge Brandeis, who rejected the National Biscuit Company’s argument under the premise that the shape was “functional”, while the name “Shredded Wheat” is simply descriptive, and therefore un-trademark-able. Judge Brandeis’ decision remains central to the U.S. statutory test for whether a name should remain un-trademarked because it is generic or descriptive.

Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. Haute Diggity Dog

Fashion house Louis Vuitton had a dog day when they decided to sue a Nevada-based pet product company, Haute Diggity Dog in 2007. The handbag maker, known around the world for its signature-branded luggage, filed a case against Haute Diggity Dog for trademark, trade dress and copyright infringement over a line of parody products entitled “Chewy Vuitton”. The defendant also reportedly had lines of products that played on the names of other international fashion brands, including “Chewnel No. 5” and “Sniffany & Co.” In a surprising move by the U.S. Court of Appeals, 4th Circuit, it was ruled that the Haute Diggity Dog products consisted of a successful parody, meaning they had not infringed on Louis Vuitton copyrights or trademarks. The court considered that the products were distinctly differentiated from Louis Vuitton products, and sought to convey a message of entertainment and amusement. It was also considered whether or not the “Chewy Vuitton” products could be confused in any way for Louis Vuitton products; a suggestion that was rejected by the court.

The post Top four high profile cases in Intellectual Property law appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMeet the Commercial Law marketing team at Oxford University Press!Meeting and mating with our ancient cousinsPlace of the Year 2014 nominee spotlight: Brazil [Infographic]

Related StoriesMeet the Commercial Law marketing team at Oxford University Press!Meeting and mating with our ancient cousinsPlace of the Year 2014 nominee spotlight: Brazil [Infographic]

Meeting and mating with our ancient cousins

Two of the biggest scientific breakthroughs in paleoanthropology occurred in 2010. Not only had we determined a draft genome of an extinct Neandertal from bones that lay in the Earth for tens of thousands of years, but the genome from another heretofore unknown ancient human relative, dubbed the Denisovans, was also announced.

A one-hundred-year-old conundrum was finally answered: did we mate with Neandertals? It was now undeniable that modern humans, with all our modern features – our rounded craniums, prominent chins, gracile faces tucked beneath an enlarged forehead, and long, slender skeletons – had met and mated with both of these extinct ancient human-like beings. After comparison with the human genome, 2-4% of the genomes of all peoples outside Africa had been directly inherited from Neandertal ancestors. And, DNA from the Denisovans (named after the cave in southern Siberia where their bones were discovered) makes up 3% to 6% of the genomes of many peoples living in South East Asia (Philippines, Melanesians, Australian Aborigines).

We now believe that it is in the Levant, regions just east of the Mediterranean, where humans met and mated with Neandertals. Remains of Neandertals are well known from this region. When modern humans ventured out of Africa into the Levant approximately 50,000 years ago, they mated with Neandertals. When they later spread into South East Asia they mated with Denisovans, although mating probably occurred in other regions of Asia as well. We now have evidence suggesting the ancient Denisovans occupied a very large geographic distribution extending from Southern Siberia all the way to the South East Asian tropics. It is tantalizing that, other than their distinctive genomes and their somewhat robust-looking molars, we know close to nothing about what they looked like.

Neanderthal skull discovered in Gibraltar in 1848. Photo by AquilaGib. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Neanderthal skull discovered in Gibraltar in 1848. Photo by AquilaGib. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.With these discoveries, the notion that modern humans would hardly have interbred with such dim-witted, brutish, and bent-kneed Neandertals – a reputation that had long dogged Neandertals since French Paleontologist Marcellin Boule studied them – was now clearly out of the question. Indeed, more recent research into the skeleton and the cultural artifacts of Neandertals has demonstrated their sophisticated material cultures (stone tools, body ornament, and symbolic culture) and that their skeletons, rather than being “primitive,” were adapted for the cold and for rugged daily physical activities. Furthermore, the almost paradigmatically-held view of a strict replacement of ancient peoples in Eurasia by colonizing modern humans is now laid to rest. This view, popularized in the 1980s and 1990s, rested on comparisons between the minute mitochondrial genomes (much less than 1% of our full genomes) of humans and Neandertals. Full genomes, as you can see, tell us a fuller and more fascinating story.

These breakthroughs open a window of fresh air into the field of anthropology after decades of speculation. They are simultaneous with advancements in detecting the genetic bases of common chronic human diseases like hypertension, obesity, and diabetes. Yet even these diseases have been shaped by our evolutionary past. Genomes tell us that our species has undergone contractions in population size during the evolutionary past, which reduced the effectiveness of natural evolutionary constraints, and allowed damaging mutations to slip through the cracks to take root in our genome. This is a new view of disease informed by evolution as well as genomes.

We are also making base-by-base comparisons of our genome with those of chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, as well as genomes of other primates, allowing us to start to look for the genomic bases of our unique features – our large and complex brains, our complex cognition, and our use of spoken language. At the same time, we are learning the degree to which there is a genetic continuum between us and our primate relatives. Darwin presciently wrote in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex that “the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.” Today, we are realizing Darwin’s dream.

We are also uncovering details about how different human populations adapted to hot and cold climates, high altitudes, different diets, and to the various pathogens modern humans encountered as we colonized different regions of the world. A large project is already well-underway to collect thousands of genomes of modern peoples from different regions of the world. Comparing these genomes allows the search for ancient footprints left by positive selection (the type of natural selection that shapes our adaptations). Surprisingly, the different pathogens we encountered as we left Africa and spread into different environments appears to have made some of the largest footprints on our genome.

The genomic highway has an unchecked speed limit; we are experiencing a unique problem where data are pouring in faster than it can be fully analyzed. Each new issue of our scientific journals is ripe with new, exciting discoveries unlocking intriguing secrets of our ancestry.

The post Meeting and mating with our ancient cousins appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe evolution of lifePlace of the Year 2014 nominee spotlight: Brazil [Infographic]Innovation and safety in high-risk organizations

Related StoriesThe evolution of lifePlace of the Year 2014 nominee spotlight: Brazil [Infographic]Innovation and safety in high-risk organizations

Place of the Year 2014 nominee spotlight: Brazil [Infographic]

With the recent announcement of our Place of the Year 2014 shortlist, we are spotlighting each of the contenders. First up is Brazil.

Brazil brought the world’s soccer fans together this year, as it hosted the 2014 FIFA World Cup in 12 different cities across the country. Learn more about this lively country in the infographic below:

Download the infographic in jpg or PDF format.

Do you think Brazil should be Place of the Year for 2014? Vote below, and keep following along with #POTY2014 until our announcement on 1 December to see which location will join previous winners.

The Place of the Year 2014 shortlist

Headline image: Amazon11. Photo by Neil Palmer (CIAT). CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Place of the Year 2014 nominee spotlight: Brazil [Infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2014 shortlist: Vote for your pickPlace of the Year 2014: the longlist, then and nowPlace of the Year 2014: behind the longlist

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2014 shortlist: Vote for your pickPlace of the Year 2014: the longlist, then and nowPlace of the Year 2014: behind the longlist

The peace of Utrecht and the balance of power

The years 2013 and 2014 mark the tercentenary of the peace settlement that put an end to one of the major and most devastating wars in early-modern European history, the War of the Spanish Succession (1700–1713/1714). The war erupted after the death without issue of the last Habsburg king of Spain, Charles II (1665–1700). Charles’s death triggered a violent conflagration of the European diplomatic system, which the major rulers of Europe had anticipated with dread but had proven incapable of averting.

When the sickly Charles II assumed the throne of Spain as a four-year-old in 1665, the problem of his succession already troubled the mind of many a European prince. The riddle of the future of the vast Spanish Monarchy — which contained among other territories Naples, Milan, the Southern Netherlands, and the colonies in Latin America and Asia — had the potential of disrupting the fabric of Europe and was a question of vital interest to all the powers of Europe. The possibility that the Spanish Monarchy might fall into the hands of another great power led France, Great Britain, and the Dutch Republic to enter into two partition treaties (22 CTS 197 and 22 CTS 471) in the interests of peace.

However, just before his death in November 1700, Charles II frustrated those hopes for lasting peace by making a new testament in which he (1) dictated that the Spanish Monarchy had to remain one and indivisible, (2) appointed Philip of Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV of France, to be his universal successor, and (3) stipulated that if Louis XIV rejected the succession, it would pass to Archduke Charles of Austria. Philip of Anjou’s assumption of the Spanish throne as Philip V (1700–1746) (as well as a series of French provocations) resurrected the grand alliance of Britain, the Dutch Republic, and the Austrian Habsburgs that had fought France in the Nine Years War. By 1702, the War of the Spanish Succession was in full flow and was to continue for more than a decade longer.

After having reached a secret, preliminary agreement with Versailles in late 1711, London forced its reluctant Dutch allies to convene a universal peace conference, which met at Utrecht in early 1712. After more than a year of further negotiations – most of which took place at a bilateral level between and in London and Versailles – on 11 April 1713, the first major peace treaties were signed at Utrecht (most important of all, that between France and Britain, 27 CTS 475). As had been the case at other ‘universal’ peace conferences before, peace was concluded not in one multilateral instrument, but through a series of bilateral peace treaties, some of them supplemented by a treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation. On 13 July 1713, the peace treaties between Spain and Britain (28 CTS 295) as well as between Spain and Savoy (28 CTS 269) followed. Between then and February 1715, some additional treaties were concluded at Utrecht. Meanwhile, Louis XIV also reached peace with the Austrian Habsburgs at Rastatt on 6 March 1714 (29 CTS 1) and with the Holy Roman Empire at Baden on 7 September 1714 (29 CTS 141).

Histoire amoureuse et badine du congres et de la ville d’Utrecht en plusieurs lettres écrites par le domestique d’un des plenipotentiaires à un de ses amis. / par Augustinus Freschot. Peace Palace Library. Digitized by Bert Mellink and Lilian Mellink-Dikker from the partnership “D-Vorm VOF”. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Histoire amoureuse et badine du congres et de la ville d’Utrecht en plusieurs lettres écrites par le domestique d’un des plenipotentiaires à un de ses amis. / par Augustinus Freschot. Peace Palace Library. Digitized by Bert Mellink and Lilian Mellink-Dikker from the partnership “D-Vorm VOF”. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.Through the Peace of Utrecht/Rastatt/Baden, the Spanish Monarchy was divided. While Philip V retained Spain and the Spanish colonies, the Italian and Belgian possessions for the most part went to the Austrian Habsburgs. But the crucial piece of the puzzle was the agreement that the French and Spanish monarchies would never be united under one person. Thereto, Philip V had to cede all his rights to the French throne, while the princes in line for the French and Spanish succession after him had to cede their rights to the Spanish throne.

Utrecht’s greatest claim to fame in the history of international law is the textual inclusion of the principle of the balance of power in the text of some peace treaties. Article 2 of the Hispano-British Peace of 13 July 1713 (28 CTS 295) literally stipulated that peace in Europe could only be sustained if the balance of power were preserved. Therefore, the union of the crowns of France and Spain could never be condoned and had to be excluded for the future. The article incorporated the different charters of cession of Philip V and the French princes, as well as their acceptance by Louis XIV. The article was based on similar clauses in the treaties of 11 April 1713, which did, however, lack a direct reference to the balance in the body of the article. But they also incorporated the same charters, all of which held such a reference.

It has been said by international lawyers that the introduction of the balance of power in the Utrecht Peace Treaties promoted it into a foundational principle of the positive law of nations. Others have pointed at the scarcity of references to balance of power in later treaties of the 18th century.

It is indeed remarkable that direct references to the balance of power in 18th-century treaties remain relatively rare and in almost all cases relate to matters of dynastic succession. The concrete legal implications of adopting the balance of power as a principle of the law of nations may indeed have been restricted to superseding the normal order of dynastic succession in a few cases but in the Europe of the 18th century this was a change of the greatest order. Since the rise of the dynastic ‘states’ in the late 15th and 16th centuries, claims to dynastic legitimacy to rule over certain territories formed the underlying fabric to the political and legal order of Europe. These were based on an amalgamation of feudal, canon and imperial law, historic rights, dynastic inheritance, conquest, and cession by treaty. Much of these lay embodied in the rules of succession that held together most states – which were in fact personal unions of different realms – and were constitutive and constitutional to that state. The supersession of these rules was nothing less, as Dhondt has convincingly argued (Frederik Dhondt, ‘From Contract to Treaty. The Legal Transformation of the Spanish Succession 1659–1713’, Journal of the History of International Law, 13 (2011) 347–75), than the transformation from a legal order based on legitimacy and at times ‘universal monarchy’ to a horizontal order based on treaties and agreement.

This new order assumed recognition of common responsibility for the ‘security and tranquillity of Europe’ – a much repeated catchphrase in late-17th and 18th-century treaties – and a special role of the great powers. Between 1713 and 1740, France and Britain would assume this responsibility by forming an objective alliance to uphold the Utrecht compromise. It is here that lurk the older roots of the modern system of collective security as a trust of the great powers.

Headline image credit: Allegory of the Consequences of the Peace of Utrecht by Paolo de Matteis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The peace of Utrecht and the balance of power appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin WallInnovation and safety in high-risk organizationsBig state or small state?

Related StoriesReading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin WallInnovation and safety in high-risk organizationsBig state or small state?

November 9, 2014

Innovation and safety in high-risk organizations

The construction or recertification of a nuclear power plant often draws considerable attention from activists concerned about safety. However, nuclear powered US Navy (USN) ships routinely dock in the most heavily populated areas without creating any controversy at all. How has the USN managed to maintain such an impressive safety record?

The USN is not alone, many organizations, such as nuclear public utilities, confront the need to maintain perfect reliability or face catastrophe. However, this compelling need to be reliable does not insulate them from the need to innovate and change. Given the high stakes and the risks that changes in one part of an organization’s system will have consequences for others, how can such organizations make better decisions regarding innovation? The experience of the USN is apt here as well.

Given that they have at their core a nuclear reactor, navy submarines are clearly high-risk organizations that need to innovate yet must maintain 100% reliability. Shaped by the disastrous loss of the USS Thresher in 1963 the U.S. Navy (USN) adopted a very cautious approach dominated by safety considerations. In contrast, the Soviet Navy, mindful of its inferior naval position relative to the United States and her allies, adopted a much more aggressive approach focused on pushing the limits of what its submarines could do.

Decision-making in both organizations was complex and very different. It was a complex interaction among individuals confronting a central problem (their opponents’ capabilities) with a wide range of solutions. In addition, the solution was arrived at through a negotiated political process in response to another party that was, ironically, never directly addressed, i.e. the submarines never fought the opponent.

Perhaps ironically, given its government’s reputation for rigidity, it was the Soviet Navy that was far more entrepreneurial and innovative. The Soviets often decided to develop multiple types of different attack submarines – submarines armed with scores of guided missiles to attack U.S. carrier battle groups, referred to as SSGNs, and smaller submarines designed to attack other submarines. In contrast the USN adopted a much more conservative approach, choosing to modify its designs slightly such as by adding vertical launch tubes to its Los Angeles class submarines. It helped the USN that it needed its submarines to mostly do one thing – attack enemy submarines – while the Soviets needed their submarines to both attack submarines and USN carrier groups.

The Hunt for Red October, Soviet Submarine – 1970s, by Kevin Labianco. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

The Hunt for Red October, Soviet Submarine – 1970s, by Kevin Labianco. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.As a result of their innovation, aided by utilizing design bureaus, something that does not exist in the U.S. military-industry complex, the Soviets made great strides in closing the performance gaps with the USN. Their Alfa class submarines were very fast and deep diving. Their final class of submarine before the disintegration of the Soviet Union – the Akula class – was largely a match for the Los Angeles class boats of the USN. However, they did so at a high price.

Soviet submarines suffered from many accidents, including ones involving their nuclear reactor. Both their SSGNs, designed to attack USN carrier groups, as well as their attack submarines, had many problems. After 1963 the Soviets had at least 15 major accidents that resulted in a total loss of the boat or major damage to its nuclear reactor. One submarine, the K429 actually sunk twice. The innovative Alfas, immortalized in The Hunt for Red October, were so trouble-prone that they were all decommissioned in 1990 save for one that had its innovative reactor replaced with a conventional one. In contrast, the USN had no accidents, though one submarine, the USS Scorpion, was lost in 1968 to unknown causes.

Why were the USN submarines so much more reliable? There were four basic reasons. First, the U.S. system allowed for much more open communication among the relevant actors. This allowed for easier mutual adjustment between the complex yet tightly integrated systems. Second, the U.S. system diffused power much more than in the Soviet political system. As a result, the U.S. pursued less radical innovations. Third, in the U.S. system decision makers often worked with more than one group – for example a U.S. admiral not only worked within the Navy, but also interacted with the shipyards and with Congress. Finally, Admiral Rickover was a strong safety advocate who instilled a strong safety culture that has endured to this day.

In short, share information, share power, make sure you know what you are doing and have someone powerful who is an advocate for safety. Like so much in management it sounds like common sense if you explain it well, but in reality it is very hard to do, as the Soviets discovered.

Feature image credit: Submarine, by subadei. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Innovation and safety in high-risk organizations appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat could be the global impact of the UK’s Legal Services Act?I miss IntradeFood insecurity and the Great Recession

Related StoriesWhat could be the global impact of the UK’s Legal Services Act?I miss IntradeFood insecurity and the Great Recession

The evolution of life

Molecular biology continues to inform science on a daily basis and reveal what it means to be human beings as we discover our place in the universe. With the ability to engage science in ways that were unimaginable only a few decades ago, we can obtain the genetic profile of a germ, discover the roots of unicellular life and uncover the mysteries of now extinct Neanderthals.

In One Plus One Equals One, author John Archibald unmasks the wonders of biotechnology, showing readers how evolution has interacted with the subcellular components of life from the beginning to present day. With molecular biology, we can look back more than three billion years to reveal the microbial activities that underpin the development of complex life, just as we can look at the inner workings of our own cells. Take a look around and ask yourself, how much do you know about the world around us?

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Headline image credit: HINGOLGADH. Photo by Kalpeshzala59. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The evolution of life appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin WallBig state or small state?Beethoven and the Berlin Wall

Related StoriesReading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin WallBig state or small state?Beethoven and the Berlin Wall

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers