Oxford University Press's Blog, page 738

November 16, 2014

After the elections: Thanksgiving, consumerism, and the American soul

The elections, thankfully, are finally over, but America’s search for security and prosperity continues to center on ordinary politics and raw commerce. This ongoing focus is perilous and misconceived. Recalling the ineffably core origins of American philosophy, what we should really be asking these days is the broadly antecedent question: “How can we make the souls of our citizens better?”

To be sure, this is not a scientific question. There is no convincing way in which we could possibly include the concept of “soul” in any meaningfully testable hypotheses or theories. Nonetheless, thinkers from Plato to Freud have understood that science can have substantial intellectual limits, and that sometimes we truly need to look at our problems from the inside.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit philosopher, inquired, in The Phenomenon of Man: “Has science ever troubled to look at the world other than from without?” This not a silly or superficial question. Earlier, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American Transcendentalist, had written wisely in The Over-Soul: “Even the most exact calculator has no prescience that something incalculable may not balk the next moment.” Moreover, he continued later on in the same classic essay: “Before the revelations of the soul, Time, Space, and Nature shrink away.”

That’s quite a claim. What, precisely, do these “phenomenological” insights suggest about elections and consumerism in the present American Commonwealth? To begin, no matter how much we may claim to teach our children diligently about “democracy” and “freedom,” this nation, whatever its recurrent electoral judgments on individual responsibility, remains mired in imitation. More to the point, whenever we begin our annual excursions to Thanksgiving, all Americans are aggressively reminded of this country’s most emphatically soulless mantra.

“You are what you buy.”

This almost sacred American axiom is reassuringly simple. It’s not complicated. Above all, it signals that every sham can have a patina, that gloss should be taken as truth, and that any discernible seriousness of thought, at least when it is detached from tangible considerations of material profit, is of no conceivably estimable value.

Ultimately, we Americans will need to learn an altogether different mantra. As a composite, we should finally come to understand, every society is basically the sum total of individual souls seeking redemption. For this nation, moreover, the favored path to any such redemption has remained narrowly fashioned by cliché, and announced only in chorus.

Where there dominates a palpable fear of standing apart from prevailing social judgments (social networking?), there can remain no consoling tolerance for intellectual courage, or, as corollary, for any reflective soulfulness. In such circumstances, as in our own present-day American society, this fear quickly transforms citizens into consumers.

Black Friday at the Apple Store on Fifth Avenue, New York City, 2011by JoeInQueens. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Black Friday at the Apple Store on Fifth Avenue, New York City, 2011by JoeInQueens. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. While still citizens, our “education” starts early. From the primary grades onward, each and every American is made to understand that conformance and “fitting in” are the reciprocally core components of individual success. Now, the grievously distressing results of such learning are very easy to see, not just in politics, but also in companies, communities, and families.

Above all, these results exhibit a debilitating fusion of democratic politics with an incessant materialism. Or, as once clarified by Emerson himself: “The reliance on Property, including the reliance on governments which protect it, is the want of self-reliance.”

Nonetheless, “We the people” cannot be fooled all of the time. We already know that nation, society, and economy are endangered not only by war, terrorism, and inequality, but also by a steadily deepening ocean of scientifically incalculable loneliness. For us, let us be candid, elections make little core difference. For us, as Americans, happiness remains painfully elusive.

In essence, no matter how hard we may try to discover or rediscover some tiny hints of joy in the world, and some connecting evidence of progress in politics, we still can’t manage to shake loose a gathering sense of paralyzing futility.

Tangibly, of course, some things are getting better. Stock prices have been rising. The economy — “macro,” at least — is improving.

Still, the immutably primal edifice of American prosperity, driven at its deepest levels by our most overwhelming personal insecurities, remains based upon a viscerally mindless dedication to consumption. Ground down daily by the glibly rehearsed babble of politicians and their media interpreters, we the people are no longer motivated by any credible search for dignity or social harmony, but by the dutifully revered buying expectations of patently crude economics.

Can anything be done to escape this hovering pendulum of our own mad clockwork? To answer, we must consider the pertinent facts. These unflattering facts, moreover, are pretty much irrefutable.

For the most part, we Americans now live shamelessly at the lowest common intellectual denominator. Cocooned in this generally ignored societal arithmetic, our proliferating universities are becoming expensive training schools, promising jobs, but less and less of a real education. Openly “branding” themselves in the unappetizing manner of fast food companies and underarm deodorants, these vaunted institutions of higher education correspondingly instruct each student that learning is just a commodity. Commodities, in turn, learns each student, exist solely for profit, for gainful exchange in the ever-widening marketplace.

Optimally, our students exist at the university in order, ultimately, to be bought and sold. Memorize, regurgitate, and “fit in” the ritualized mold, instructs the college. Then, all be praised, all will make money, and all will be well.

But all is not well. In these times, faced with potentially existential threats from Iran, North Korea, and many other conspicuously volatile places, we prefer to distract ourselves from inconvenient truths with the immense clamor of imitative mass society. Obligingly, America now imposes upon its already-breathless people the grotesque cadence of a vast and over-burdened machine. Predictably, the most likely outcome of this rhythmically calculated delirium will be a thoroughly exhausted country, one that is neither democratic, nor free.

Ironically, we Americans inhabit the one society that could have been different. Once, it seems, we still had a unique opportunity to nudge each single individual to become more than a crowd. Once, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the quintessential American philosopher, had described us as a unique people, one motivated by industry and “self-reliance,” and not by anxiety, fear, and a hideously relentless trembling.

America, Emerson had urged, needed to favor “plain living” and “high thinking.” What he likely feared most was a society wherein individual citizens would “measure their esteem of each other by what each has, and not by what each is.”

No distinctly American philosophy could possibly have been more systematically disregarded. Soon, even if we can somehow avoid the unprecedented paroxysms of nuclear war and nuclear terrorism, the swaying of the American ship will become unsustainable. Then, finally, we will be able to make out and understand the phantoms of other once-great ships of state.

Laden with silver and gold, these other vanished “vessels” are already long forgotten. Then, too, we will learn that those starkly overwhelming perils that once sent the works of Homer, Goethe, Milton, and Shakespeare to join the works of more easily forgotten poets are no longer unimaginable. They are already here, in the newspapers.

In spite of our proudly heroic claim to be a nation of “rugged individuals,” it is actually the delirious mass or crowd that shapes us, as a people, as Americans. Look about. Our unbalanced society absolutely bristles with demeaning hucksterism, humiliating allusions, choreographed violence, and utterly endless political equivocations. Surely, we ought finally to assert, there must be something more to this country than its fundamentally meaningless elections, its stupefying music, its growing tastelessness, and its all-too willing surrender to near-epidemic patterns of mob-directed consumption.

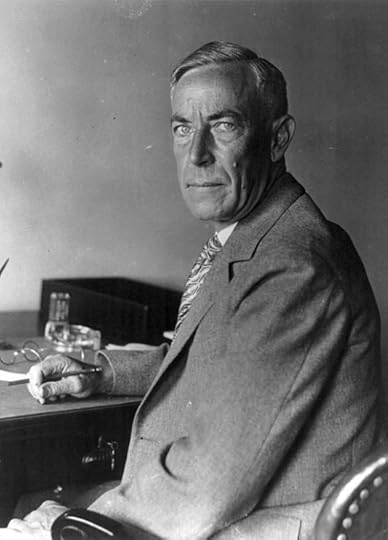

In an 1897 essay titled “On Being Human,” Woodrow Wilson asked plaintively about the authenticity of America. “Is it even open to us,” inquired Wilson, “to choose to be genuine?” This earlier American president had answered “yes,” but only if we would first refuse to stoop so cowardly before corruption, venality, and political double-talk. Otherwise, Wilson had already understood, our entire society would be left bloodless, a skeleton, dead with that rusty death of machinery, more unsightly even than the death of an individual person.

“The crowd,” observed the 19th century Danish philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, “is untruth.” Today, following recent elections, and approaching another Thanksgiving, America’s democracy continues to flounder upon a cravenly obsequious and still soulless crowd. Before this can change, we Americans will first need to acknowledge that our institutionalized political, social, and economic world has been constructed precariously upon ashes, and that more substantially secure human foundations now require us to regain a dignified identity, as “self-reliant” individual persons, and as thinking public citizens.

Heading image: Boxing Day at the Toronto Eaton Centre by 松林 L. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post After the elections: Thanksgiving, consumerism, and the American soul appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Republican view on bipartisanshipI miss IntradeHow to naturalize God

Related StoriesThe Republican view on bipartisanshipI miss IntradeHow to naturalize God

November 15, 2014

How to naturalize God

A former colleague of mine once said that the problem with theology is that it has no subject-matter. I was reminded of Nietzsche’s (unwittingly self-damning) claim that those who have theologians’ blood in their veins see all things in a distorted and dishonest perspective, but it was counterbalanced a few years later by a comment of another philosopher – on hearing of my appointment to Heythrop College – that it was good that I’d be working amongst theologians because they are more open-minded than philosophers.

Can one be too open-minded? And isn’t the limit traversed when we start talking about God, or, even worse, believe in Him? Presumably yes, if atheism is true, but it is not demonstrably true, and it is unclear in any case what it means to be either an atheist or a theist. (Some think that theists make God in their own image, and that the atheist is in a better position to relate to God.)

The atheist with which we are most familiar likewise takes issue with the theist, and A.C. Grayling goes so far as to claim that we should drop the term ‘atheist’ altogether because it invites debate on the ground of the theist. Rather, we should adopt the term ‘naturalist’, the naturalist being someone who accepts that the universe is a natural realm, governed by nature’s laws, and that it contains nothing supernatural: ‘there is nothing supernatural in the universe – no fairies or goblins, angels, demons, gods or goddesses’.

I agree that the universe is a natural realm, governed by nature’s laws, and I do not believe in fairies or goblins, angels, demons, gods or goddesses. However, I cannot accept that there is nothing supernatural in the universe until it is made absolutely clear what this denial really means.

The trouble is that the term ‘naturalism’ is so unclear. To many it involves a commitment to the idea that the scientist has the monopoly on nature and explanation, in which case the realm of the supernatural incorporates whatever is not natural in this scientific sense.

Others object to this brand of naturalism on the ground that there are no good philosophical or scientific reasons for assigning the limits of nature to science. As John McDowell says: ‘scientism is a superstition, not a stance required by a proper respect for the achievements of the natural sciences’.

Lonely place, by Amaldus Clarin Nielsen. Public domain via The Athenaeum.

Lonely place, by Amaldus Clarin Nielsen. Public domain via The Athenaeum. McDowell endorses a form of naturalism which accommodates value, holding that it cannot be adequately explained in purely scientific terms. Why stick with naturalism? In short, the position – in its original inception – is motivated by sound philosophical presuppositions.

It involves acknowledging that we are natural beings in a natural world, and gives expression to the demand that we avoid metaphysical flights of fancy, ensuring that our claims remain empirically grounded. To use the common term of abuse, we must avoid anything spooky.

The scientific naturalist is spooked by anything that takes us beyond the limits of science; the more liberal or expansive naturalist is not. However, the typical expansive naturalist stops short of God. Understandably so, given his wish to avoid metaphysical flights of fancy, and given the assumption that such a move can be criticised on this score.

Yet what if his reservations in this context can be challenged in the way that he challenges the scientific naturalist’s reluctance to accept his own position? (The scientific naturalist thinks that McDowell’s values are just plain spooky, and McDowell challenges this complaint on anti-scientistic grounds.)

McDowell could object that the two cases are completely different – God is spooky in the way that value is not. Yet this response simply begs the question against the alternative framework at issue – a framework which challenges the assumption that God must be viewed in these pejorative terms.

The idea that there is a naturalism to accommodate God does not mean that God is simply part of nature – I am not a pantheist – but it does mean that the concept of the divine can already be understood as implicated in our understanding of nature, rather than being thought of as entirely outside it.

So I am rejecting deism to recuperate a form of theistic naturalism which will be entirely familiar to the Christian theist and entirely strange (and spooky) to the typical atheist who is a typical naturalist. McDowell is neither of these things – that’s why his position is so interesting.

The post How to naturalize God appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSan Diego, here we comeAdele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler on the Hebrew BibleThe Republican view on bipartisanship

Related StoriesSan Diego, here we comeAdele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler on the Hebrew BibleThe Republican view on bipartisanship

Back to the future with the ASC’s new Division of Policing

On 31 December 1941, August Vollmer hosted the first meeting of the National Association of College Police Training Officials at his home. The organization initially focused on developing standardized curricula for university-based policing programs, but soon expanded its scope to include the more general field of criminology. In 1958, the American Society of Criminology (ASC) name was officially adopted.

Vollmer, first police chief of Berkeley, CA and founder of the first school of criminology at the University of California Berkeley, is generally regarded as the father of modern policing.

O.W. Wilson, himself a prominent figure in modern policing, perhaps summed up Vollmer’s influence best in a 1953 article in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology: “August Vollmer, police administrator and consultant, student, educator, author, and criminologist, will be recorded in American police history as the man who contributed most to police professionalization by promoting the application of scientific principles to police service.”

While Vollmer’s focus on science was largely on forensic and physical sciences, in part because of a lack of social science research on the police at the time, he was one of the first to recognize that the police could partner with scientists and other outsiders to increase their effectiveness and efficiency. He embodied the idea of infusing policing with research and scientific knowledge that is the hallmark of efforts to make policing more evidence-based today.

We can only speculate on how Vollmer would run a police department today. But based on his strong belief that officers should be well-educated and exposed to the latest research findings through extensive training throughout their careers, we might assume he would embrace close collaboration between police and social scientists and the use of findings from rigorous studies to guide police practice. Today, our evidence base outside of the hard sciences is far larger. The Evidence-Based Policing Matrix, for example, includes nearly 130 methodologically rigorous studies of the crime control effectiveness of policing strategies.

As O.W. Wilson’s quote suggested, Vollmer not only incorporated research into policing, but he also was one of the first to straddle the line between science and practice through his work as a police chief and university professor. Vollmer’s interest in the link between universities and policing inspired that New Year’s Eve meeting in 1941, which eventually led to the formation of the ASC, now the largest professional organization devoted to criminology in the world.

August Vollmer, “father of modern law enforcement,” 6 September 1929, photo by Underwood & Underwood. Public domain via Library of Congress.

August Vollmer, “father of modern law enforcement,” 6 September 1929, photo by Underwood & Underwood. Public domain via Library of Congress.The initial close link between the ASC and police education quickly dissipated, however. Many of the police practitioners and professors initially involved in the creation of the ASC began to feel as though the organization had become too sociological and concerned with questions of crime causation and uninterested in police practice. As Willard Oliver describes in his History of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences (ACJS), the International Association of Police Professionals was established by former ASC members in 1963 to focus more on police education. The organization eventually expanded its focus to the entire criminal justice system and took on its current name of ACJS. Thus, while Vollmer was instrumental in the creation of the ASC, his followers soon abandoned the organization in favor of ACJS. As a result, police practitioners have traditionally been more involved in the Annual Meetings of the ACJS, which has had a section on policing for more than 20 years.

Recently, a group of scholars and practitioners brought together by Cynthia Lum of George Mason University have begun the critical work of highlighting policing as an important part of criminology and the ASC. In May of this year, the ASC approved a new Division of Policing, with membership open to any ASC member. We encourage members to consider joining the Division when renewing (or beginning) their ASC membership for 2015.

As Anthony Braga, Cynthia Lum, and Edward Davis described in a recent article in The Police Chief, a major goal of the Division is to build strong partnerships between police and researchers that will ideally increase the number of completed research studies and improve translation of research findings into police practice. The Division thus marks a return to the roots of the ASC and Vollmer’s vision of a policing profession consistently using the best science and research to guide policy and practice.

Even without a formal Division in place, policing presentations have become a major component of the ASC conference. A guide to policing sessions of interest at the Annual Meeting next week includes more than 120 panels with policing presentations. This number should only increase in future years with the Division’s efforts, and ideally the number of police practitioners presenting at ASC will increase exponentially.

We invite everyone attending the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Criminology to join us at the inaugural event for the Division of Policing to be held 20 November 2014 from 4:00-5:30pm.

The event will include opening remarks from San Francisco District Attorney and former Police Chief George Gascón. Wesley Skogan of Northwestern University will then provide a brief history of police research and introduce a distinguished group of police researchers and practitioners who will each speak briefly about their vision for the future of policing research.

It seems especially appropriate that this kick-off event for the Division will take place at the Marriott Marquis San Francisco, less than 15 miles away from 923 Euclid Avenue in Berkeley, Vollmer’s former home and the birthplace of the ASC.

The post Back to the future with the ASC’s new Division of Policing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow well do you know the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984?Global solidarity and Cuba’s response to the Ebola outbreakAcademics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. Pickron

Related StoriesHow well do you know the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984?Global solidarity and Cuba’s response to the Ebola outbreakAcademics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. Pickron

San Diego, here we come

Ever since last year’s American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature meeting in Baltimore, the Religion and Bibles team at Oxford University Press has eagerly awaited San Diego in 2014. As we gear up to travel to the west coast, we asked our staff across divisions and offices: What is on your to-do list while in San Diego?

Tom Perridge, Academic/Trade, UK:

I’m looking forward to returning to San Diego, having previously visited for the 2007 AAR/SBL. Oxford is cold, grey, and autumnal at the moment, so some Californian sunshine will be welcome! It’s always a pleasure to connect with both authors and readers and to cook up ideas for exciting new projects.

Don Kraus, Bibles, US:

As part of my task in publishing Oxford Study Bibles, I am meeting with the editorial boards of various projects in order to keep them moving along. I also hope to see some of the scholars I’ve worked with over the past years, just to catch up and have a chance to hear how they are doing. I look forward to meeting, either again or for the first time, as many scholars as possible who have worked on the second edition of The Jewish Study Bible, our brand-new, fully revised and updated revision of a text that’s already a classic.

Steve Wiggins, Academic/Trade and Bibles, US:

I hope to meet a long-lost cousin (literally!), as well as authors I’ve only met by email. Of course, seeing people I’ve known over the past two decades of attending is always a highlight. It’s all about the people.

Sara McNamara, Journals, US:

Though spending as much time outside exploring San Diego’s parks and beaches is definitely a priority, number one on my to-do list is a breakfast event for journals editors I’ve organized with the AAR and SBL. The breakfast will provide a rare opportunity for religious, biblical, and theological studies journals editors to come together to discuss the unique challenges facing journals and their editors. Emceed by Amir Hussain, the editor of Journal of the American Academy of Religion, the breakfast promises to be both fun and informative.

Gina Chung, Academic/Trade, US:

This year will not only be my first time at AAR, but also my first time in San Diego! I’m really excited to meet our authors in person, and I’m looking forward to getting some sun and 70 degree weather in November as well.

Alyssa Bender, Academic/Trade and Bibles, US:

I can’t wait to meet this year’s new batch of authors at the meeting, and hopefully snap some pictures of them with their books. I’m also excited to explore the city and find some fun restaurants! Hopefully at least one with outdoor seating—have to take advantage of the beautiful San Diego weather!

We hope to see you at Oxford University Press booth 829! We’ll be offering the chance to:

Check out which books we’re featuring.

Browse and buy our new and bestselling titles on display at a 20% conference discount.

Peruse our conference ebook promotion (up to 90% off!)

Get free trial access to our suite of online products.

Pick up sample copies of our latest religion journals.

Enter giveaways for free OUP books.

Meet all of us!

See you there!

The post San Diego, here we come appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Republican view on bipartisanshipOn World Diabetes Day, a guide to managing diabetes during the holidaysImmigration and emigration: taking the long-term perspective for our better health

Related StoriesThe Republican view on bipartisanshipOn World Diabetes Day, a guide to managing diabetes during the holidaysImmigration and emigration: taking the long-term perspective for our better health

The Republican view on bipartisanship

Anyone who expects bipartisanship in the wake of last Tuesday’s elections has not been paying attention. The Republican Party does not believe in a two-party system that includes the Democrats, and it never has. Ever since the Civil War, when the Republicans were convinced that their Democratic opposition was in treacherous league with the Confederacy, the Grand Old Party in season and out has doubted the legitimacy of the Democrats to hold power. While the Republicans have accepted the results of national elections as facts they could not change, they have not believed that the Democrats were ever legitimately holding power. Democratic victories, in the minds of Republicans, are the result of fraud and abuse.

Consider some examples: In 1876, Republicans in New York said the Democratic party was “the same in character and spirit as when it sympathized with treason.” Half a century later, speaking of Woodrow Wilson, Henry Cabot Lodge told the 1920 Republican national convention that “Mr. Wilson stands for a theory of administration and government which is not American.” When Senator Joseph R. McCarthy spoke of “twenty years of treason” in the 1950s, he was not joking. He meant the statement as literal fact. So too did an aide to George H.W. Bush in 1992 when he observed, “We are America. These other people are not America.”

So when Rush Limbaugh comments that “Democrats were not elected to govern,” or Leon H. Wolf of Redstate says Democrats “should not be even be invited to be part of the discussion lest their gangrenous, festering and destructive ideas should further infect our caucus,” they are reflecting an attitude toward the Democrats that is at least a century and a half old.

If, as many Republicans believe, there are elements of illegitimacy and evil in the Democratic Party under the leadership of President Obama, then a posture of intense resistance become a necessary GOP tactic. Meeting the threat that the Democrats pose in terms of such issues as same-sex marriage, climate change and immigration reform requires going beyond politics as usual and employing any means necessary to save the nation.

For contemporary Republicans, scorched earth tactics and all-out opposition seem the appropriate response to the presence of a pretender in the White House who in their minds is pursuing the collapse of the American republic. There no longer exists between Republicans and Democrats a rough consensus about the purpose of the United States.

The 2008 Republican National Convention. Photo part of the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress.

The 2008 Republican National Convention. Photo part of the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress.How has it come to this? A long review of both political parties suggests that the experience of the Civil War introduced a flaw into American democracy that was never resolved or recognized. The Republicans regarded the wartime flirtation of some Democrats with the Confederacy as evidence of treason. So it may have been at that distant time. What rendered that conclusion toxic was the perpetuation of the idea of Democratic illegitimacy and betrayal long after 1865.

After their extended years in the wilderness during the New Deal, Republicans reasserted their presidential dominance, with a few Democratic interruptions from 1952 to 1992. Republicans thus saw in the ascendancy of Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and the two Bushes a return to the proper order of politics in which the Republicans were destined to be in charge and Democrats to occupy a position of perennial deference outside of Congress.

Then the unthinkable happened. Not just a Democrat but a black Democrat won the White House. The southern-based Republican Party saw its worst fears coming true. A man with a foreign-sounding name, an equivocal religious background, and a black skin was president and pursuing what were to most Republicans sinister goals. Under his administration, blacks became assertive, gays married, the poor got health care, and the wealthy faced both a lack of due respect and a claim on their income.

The Republican allegiance to traditional democratic practices now seemed to them outmoded in this national crisis. Americans could not really have elected Barack Obama and put his party in control of the destiny of the nation. Such an outcome must be illegitimate. And what is the remedy for illegitimacy, treason, and godlessness? To quote Leon Wolf again: “Working with these people is not what America elected you to do. Republicans, it elected you to stop them.” Pundits who forecast a new era of bipartisanship comparable to what Dwight D. Eisenhower, Everett Dirksen, Sam Rayburn, and Lyndon B. Johnson achieved in the 1950s are living in a nostalgic dream world. Richard Nixon viewed politics as war and contemporary Republicans will proceed to explore the validity of his insight over the next two years. For the American voter, clinging to the naive notion of the parties working together, each taking part of the loaf, the best guide may be Bette Davis in All About Eve: “Fasten your seat belts. It’s going to be a bumpy night.”

Featured image: Members of the Republican Party gather at the 1900 National Convention. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Republican view on bipartisanship appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMapping historic US electionsThe Civil War in five sensesI miss Intrade

Related StoriesMapping historic US electionsThe Civil War in five sensesI miss Intrade

Global solidarity and Cuba’s response to the Ebola outbreak

How did the international community get the response to the Ebola outbreak so wrong? We closed borders. We created panic. We left the moribund without access to health care. When governments in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Senegal, Guinea, Mali, and Nigeria called out to the world for help, the global response went to mostly protect the citizens of wealthy nations before strengthening health systems on the ground. In general, resources have gone to guarding borders rather than protecting patients in the hot zone from the virus. Yet, Cuba broke this trend by sending in hundreds of its own health workers into the source of the epidemic. Considering the broader global response to Ebola, why did Cuba get it so right?

Ebola impacted countries, and the World Health Organization (WHO), called out for greater human resources for health. While material supplies arrived, many countries tightened travel restrictions, closed their doors and kept their medical personnel at home. At a time when there has never been greater knowledge, more money, and ample resources for global health, the world responded to an infectious pathogen with some material supplies, but also with securitization, experimental vaccines, and forced quarantines – all of which oppose accepted public health ethics. The result is that without human resources for health on the ground, the supplies stay idle, the vaccines remain questionable, and the securitization instills fear.

The Global North evacuated their infected citizens. These evacuations spawned donations to the WHO and then led to travel bans. The United Kingdom provided £230 million in material aid to West Africa. The United States committed $175 million to combat the virus by transporting supplies and personnel, with an estimated 3,000 soldiers to be involved in the response. Canada’s government provided some $35 million to Ebola, including a mobile testing lab, sanitary equipment and 1,000 vials of experimental vaccines that have yet to arrive in West Africa or even be tested on humans. Canada then followed the example of Australia, North Korea, and other nervous nations, in imposing a visa ban on persons traveling from Ebola affected countries. Even Rwanda imposed screening on Americans because of confirmed cases in the United States.

View of Havana skyline from Hotel Nacional by Hmaglione10. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

View of Havana skyline from Hotel Nacional by Hmaglione10. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Despite this global trend, Cuba — a small and economically hobbled nation — chose to make a world of difference for those suffering from Ebola by sending in 465 health workers, expanding hospital beds, and training local health workers on how to treat and prevent the virus. Cuba is the only nation to respond to the call to stop the Ebola epidemic by actually scaling up health care capacity in the very places where it is needed the most. Even with a Gross Domestic Product per capita to that of Montenegro, Cuba has proven itself as a global health power during the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Many scholars and pundits have been left wondering not only how a low-income country, with its own social and economic challenges, could send impressive medical resources to West Africa, but also why they would dive into the hot zone in the first place — especially when nobody else dares to do so.

Cuba is globally recognized as an outstanding health-care power in providing affordable and accessible health services to its own citizens and to the citizens of 76 countries around the world, including those impacted by Ebola. Cuba’s health outreach is grounded in the epistemology of solidarity — a normative approach to global health that offers a unique ability of strengthening the core of health systems through long-term commitments to health promotion, disease prevention and primary care. Solidarity is a cooperative relationship between two parties that is mutually transformative by maximizing health-care provision, eroding power structures that promote inequity, and by seeking out mutual social and economic benefit. The reason for the general amazement and wonder over Cuba’s Ebola-response stems from a lack of depth in understanding the normative values of solidarity, as it is not a driving force in the global health outreach by most wealthy nations. The ethic of solidarity can even be seen on the ground in West Africa with Cuban doctors like Ronald Hernandéz Torres posting photos of his Ebola team wearing the protective gear, while giving the thumbs and peace sign — an incredible snapshot of humanity that contrasts the typically frightening images of Ebola health workers.

Solidarity is not charity. Charity is governed by the will of the donor and cannot be broad enough to overcome health calamities at a systems level. Solidarity is also not pure altruism. Selfless giving is based on exceptional, and often short-term, acts for no expectation of reward or reciprocity. For Cuba, solidarity in global health comes with the expectation of cooperation, meaning that the recipient nation should offer some level of support to Cuba, be it financial or political. Solidarity also means that there is a long-term relationship to improve the strength of a health system. Cuba’s current commitment to Ebola could last months, if not years.

Cuba’s global health outreach can be approached through the lens of solidarity. This example implies engaging global health calamities with cooperation over charity, with human resources in addition to material resources, and ultimately with compassion over fear. This approach could well be at the heart of wiping out Ebola — along with every other global health calamity that continues to get the best of us because we have not yet figured out how to truly take care of each other.

Heading image: Ebola treatment unit by CDC Global. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Global solidarity and Cuba’s response to the Ebola outbreak appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImmigration and emigration: taking the long-term perspective for our better healthBioethics and the hidden curriculumEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

Related StoriesImmigration and emigration: taking the long-term perspective for our better healthBioethics and the hidden curriculumEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

November 14, 2014

Who should be shamefaced?

Jose Nuñez lives in a homeless shelter in Queens with his wife and two children. He remembers arriving at the shelter: ‘It’s literally like you are walking into prison. The kids have to take their shoes off, you have to remove your belt, you have to go through a metal detector. Even the kids do. We are not going into a prison, I don’t need to be stripped and searched. I’m with my family. I’m just trying to find a home’.

Maryann Broxton, a lone mother of two, finds life exhausting and made worse by ‘the consensus that, as a poor person, it is perfectly acceptable to be finger printed, photographed and drug-tested to prove that I am worthy of food. Hunger is not a crime. The parental guilt is punishment enough.’

Palma McLaughlin, a victim of domestic violence, notes that ‘now she is poor, she is stigmatised’; no longer ‘judged by her skills and accomplishments but by what she doesn’t have’.

People in poverty feel ashamed because they cannot afford to live up to social expectations. Being a good parent means feeding your children; being a good relative means exchanging gifts at celebrations. Friendships need to be sustained by buying a round of drinks or returning money that has been borrowed. When you cannot afford to do these things, your sense of shame is magnified by others. Friends, even close relatives, avoid you. Your children despise you, asking, for example: ‘why was I born into this family?’. Society similarly accuses you of being lazy, abusing drugs or promiscuity, assumed guilty until proved innocent. You can even be blamed for the ills of your country, the high levels of crime or its relative economic decline. The middle class in Uganda ask: ‘how can Uganda be poor when the soils are rich and the climate is good if it’s not the fault of subsistence farmers’?’

In the US, as in Britain, it may be welfare expenditure that is blamed for stifling productive investment.

Beggar’s sign, by Gamma Man. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Beggar’s sign, by Gamma Man. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.Shame is debilitating as well as painful. People avoid it by attempting to keep up appearances, pretending everything is fine. In so doing, they often live in fear of being found out and risk overextending finances and incurring bad debts. People in poverty typically avoid social situations where they risk being exposed to shame; in so doing lose the contacts that might help them out when times get particularly harsh. Sometimes shame drives people into clinical depression, to substance abuse and even to suicide. Shame saps self-esteem, erodes social capital and diminishes personal efficacy raising the possibility that it serves also to perpetuate poverty by reducing individuals’ ability to help themselves.

Shame also divides society. While the stigma attaching to policies can be unintentional, sometimes the result of underfunding and staff working under pressure, the public rhetoric of deserving and undeserving exacerbates misunderstanding between rich and poor, nurturing the presumption that the latter are invariably inadequate or dishonest. Often around the world, stigmatising welfare recipients is deliberate and frequently supported by popular opinion. Blaming and shaming are commonly thought to be effective ways of policing access to welfare benefits and regulating anti-social and self-destructive behaviour. However, such beliefs are based on two assumptions that are untenable. The first is that poverty is overwhelmingly of people’s own making, the result of individual inadequacy. This can hardly be the case in Uganda, Pakistan or India. Nor is so elsewhere. Poverty is for the most part structural, caused by factors beyond individual control relating to the workings of the economy, the mix of factors of production and the outcome of primary and secondary resource allocation. The second assumption is that shaming people changes their behaviour enabling them to lift themselves out of poverty. However, the scientific evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that shaming does not facilitate behavioural change but merely imposes further pain.

Jose, Maryann and Palma were not participants in a research project. Rather they are members of ATD Fourth World, an organisation devoted to giving people in poverty voice, and their testimonials are available to read online. Echoing Martin Luther King, Palma dreams that one day her four children will be judged not by the money in their bank accounts but by the quality of their character.

Headline image credit: ‘Someone Special to Someone, Sometime’ by John W. Iwanski. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Who should be shamefaced? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesI miss IntradeWhat could be the global impact of the UK’s Legal Services Act?Innovation and safety in high-risk organizations

Related StoriesI miss IntradeWhat could be the global impact of the UK’s Legal Services Act?Innovation and safety in high-risk organizations

Academics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. Pickron

This week, we bring you an interview with activist and historian Jeffrey W. Pickron. He and three other scholars spoke about their experiences as academics and activists on a riveting panel at the recent Oral History Association Annual Meeting. In this podcast, Pickron talks to managing editor Troy Reeves about his introduction to both oral history and activism, and the risks and rewards of speaking out.

Heading image: Boeing employees protest meeting in Seattles City Hall Park, 1943 by Seattle Municipal Archives. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Academics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. Pickron appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe power of oral history as a history-making practiceBioethics and the hidden curriculumEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

Related StoriesThe power of oral history as a history-making practiceBioethics and the hidden curriculumEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

On World Diabetes Day, a guide to managing diabetes during the holidays

The International Diabetes Foundation has marked 14 November as World Diabetes Day, commemorating the date that Frederick Banting and his team first discovered insulin, and the link between it and diabetic symptoms.

As we approach the festive season, a time of year when indulgence and comfort are positively encouraged, keeping track of, or even thinking about blood glucose levels can become a difficult and annoying task. If good diabetic practice relies on building routines suited to the way your blood sugar levels change throughout the day, then the holidays can prove a big disruption to the task of keeping diabetes firmly in the background. With this in mind, take a look at this list of tips, facts, and advice taken from Diabetes by David Matthews, Niki Meston, Pam Dyson, Jenny Shaw, Laurie King, and Aparna Pal to help you stay in control and happy throughout the festive months:

Eat regularly. When big occasions cause your portion sizes to increase alarmingly, it’s tempting to skip or put off other meals. But eating large amounts at irregular intervals can cause blood glucose levels to rise significantly. For many, it’s better to snack throughout the day, including some starchy rather than sugary carbohydrates, promoting slow glucose release into the bloodstream. Alternate drinks. Big dinners, big nights, and family days are likely to mean you consume more alcohol than normal. Alternating alcoholic drinks with diet drinks, soda, or mineral water can minimize their effect on blood glucose levels, so you can stay out, and keep up, without worrying. Help your liver. Alcohol is metabolized by the liver, an organ that also helps release glucose into the bloodstream when levels start to drop. After drinking, the liver is busy processing alcohol, so cannot release glucose as effectively. This increases the risk of hypoglycaemia, especially in people who take insulin or sulphonylurea tablets. To combat this risk, try to avoid drinking on an empty stomach, or eat starchy foods when drinking. You may also need to snack before bed if you’re drinking in the evening. Eat more, exercise more. Regular activity can have major benefits on your diabetes, making the insulin you produce or inject work more efficiently. Both aerobic and anaerobic exercise will have positive effects, and are excellent ways of giving you a mental boost (though blood glucose levels should be monitored). Many symptoms of hypos are similar to those of exercise, such as hotness, sweating or an increased heart rate. Check blood glucose levels regularly and make necessary adjustments; fruit contains natural sugar and is a healthy way of quickly raising levels. Go for your New Year’s resolution. Losing five to ten percent of your starting weight can have a positive impact on your diabetes, not to mention your overall health. Although exercise and eating well are of course promoted by all as the best way to lose weight, there is no medical consensus on one ideal way to achieve weight loss. The key lies in finding an effective approach that you can maintain. Remember that insulin can slow down weight loss, and if you are trying to lose weight, but find you’re having hypos, you’ll need to adjust your medication. Discuss this with your healthcare team. Check Labels. Sodium isn’t synonymous with salt, but many food manufacturers often list sodium rather than salt content on food packaging. To convert a sodium figure into salt, you need to multiply the amount of sodium by 2.5. (For example: A large 12 inch cheese and tomato pizza provides 3.6 g of sodium. 3.6 multiplied by 2.5 is 9, so, the pizza contains approximately 9g of salt; one and a half times the recommended maximum of 6g.) Don’t worry! Although a good routine is important, occasional lapses shouldn’t have a drastic effect on blood glucose levels (though this varies from person to person). Pick up a healthy routine in the New Year, when you’ll feel most motivated, and stick to it. The World Health Organization estimates over 200 million people will have type 2 diabetes by the year 2015, but (according to the international diabetes foundation) over 70% of cases of type 2 diabetes could be prevented by adopting healthier lifestyles. Healthy living is not just a supplement, but part of the treatment of diabetes.Heading image: Christmas Eve by Carl Larsson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post On World Diabetes Day, a guide to managing diabetes during the holidays appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImmigration and emigration: taking the long-term perspective for our better healthBioethics and the hidden curriculumPatterns in physics

Related StoriesImmigration and emigration: taking the long-term perspective for our better healthBioethics and the hidden curriculumPatterns in physics

Celebrating Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (1912-1954) was a mathematician and computer scientist, remembered for his revolutionary Automatic Computing Engine, on which the first personal computer was based, and his crucial role in breaking the ENIGMA code during the Second World War. He continues to be regarded as one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century.

We live in an age that Turing both predicted and defined. His life and achievements are starting to be celebrated in popular culture, largely with the help of the newly released film The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing and Keira Knightley as Joan Clarke. We’re proud to publish some of Turing’s own work in mathematics, computing, and artificial intelligence, as well as numerous explorations of his life and work. Use our interactive Enigma Machine below to learn more about Turing’s extraordinary achievements.

Image credits: (1) Bletchley Park Bombe by Antoine Taveneaux. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Alan Turing Aged 16, Unknown Artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Good question by Garrett Coakley. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Celebrating Alan Turing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRemembrance DayBioethics and the hidden curriculumEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

Related StoriesRemembrance DayBioethics and the hidden curriculumEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers