Oxford University Press's Blog, page 741

November 9, 2014

Replication, data access, and transparency in social science

Improving the transparency of the research published in Political Analysis has been an important priority for Jonathan Katz and I as co-editors of the journal. We spent a great deal of time over the past two years developing and implementing policies and procedures to insure that all studies published in Political Analysis have replication data available through the journal’s Dataverse. At this point in time, we have over 220 studies available in the journal’s Dataverse archive, and those studies have had more than 14,400 downloads. We see this as a major accomplishment for Political Analysis.

We are also optimistic that soon many political science journals will join us in implementing similar replication standards. An increasing number of journals developing and implementing replication standards will improve the quality of research in political science, aid in the distribution of materials that can be used in our classrooms, and make the publication process more straightforward for authors.

In late September, Jonathan and I had the opportunity to participate in a two-day “Workshop on Data Access and Research Transparency” at the University of Michigan. The workshop is part of an initiative sponsored by the American Political Science Association (APSA) to develop a discipline-wide discussion of how to improve research transparency in political science. The primary goal was to bring the editors of the primary journals in political science into this conversation. While there is no doubt that there was widespread agreement among the journal editors present that making research more transparent and making data more accessible are important goals, there are still open questions about how such goals can be implemented.

One of the major products of this workshop was a statement of principles for political science journals. While the statement has not yet been released, it contains a short set of principles, the most important of which are that the signing journals will require authors to make replication materials accessible, and that the signing journals will take steps to make the research published in their journal more transparent. Political Analysis is one of the signatories of this statement: we will continue to work to improve the accessibility of data and other research materials for the papers we publish in Political Analysis, as well as assist other journals as they work to develop their own replication and research transparency standards.

As part of this initiative, we have revised our author and reviewer instructions. Our new instructions include:

Updated and clarified standards for how authors should present empirical results in their submissions, in particular tables and figures.

More detailed instructions on our replication requirement.

Encouragement and guidance for authors who wish to pre-register their research studies.

We hope that other journals will follow our lead, and that they will quickly develop strong standards for replication and research transparency. The APSA initiative is laudable, and it is helping to position political science as a leader in these areas, certainly in the social sciences but also throughout the sciences and humanities. We welcome the APSA DART initiative, and will continue to work to position Political Analysis as a leader in developing and implementing data access and research transparency standards.

Headline image credit: Circuit board. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Replication, data access, and transparency in social science appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesForgiveness makes late-life sweeterMapping historic US electionsFood insecurity and the Great Recession

Related StoriesForgiveness makes late-life sweeterMapping historic US electionsFood insecurity and the Great Recession

Reading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall

“This is a historic day. East Germany has announced that, starting immediately, its borders are open to everyone. The GDR is opening its borders … the gates in the Berlin Wall stand open.”

—Hans Joachim Friedrichs, reporting for the Tagesthemen, 9 November 1989

On 9 November 1989, at midnight, the East German government opened its borders to West Germany for the first time in almost thirty years: a city divided, families and friends separated for a generation, reunited again. For much of its existence, attempting to cross the wall meant almost certain death, and around 80 East Germans were killed in the attempt, shot down by the border guards as they tried to make their escape. With this announcement, however, the gates were thrown open.

The mood was euphoric. East Germans surged through the opened gates, shouting and cheering, to be met by the West Germans on the other side. That same night, they began dismantling the barrier which had kept them apart together, chipping away the bricks to keep as mementos. The fall of the Wall — an ugly scar across Berlin, adorned in barbed wire and patrolled by guards with machine guns — was a pivotal event in German history. A nation crippled by the most devastating conflict in living memory, and then carved up and separated from itself by the victors, could finally shrug off the long shadow cast by a dark history, and look toward a brighter, unified future.

The seismic consequences of the demolition were also felt well beyond the borders of Germany, and, along with the slow rusting and decay of the Iron Curtain, helped to spell the end for the USSR. In just two years after the wall’s demolition, the Soviet Union would cease to exist, thus ending the era we now call the Cold War. A period of around fifty years, marked by suspicion, space rockets, assassinations, espionage, show trials, paranoia, and propaganda, and which brought the world to the brink of destruction with the Cuban Missile Crisis, was finally at an end.

To mark the 25th anniversary of this momentous moment, we’ve compiled a selection of free chapters and articles across our online resources, which shed further light on the history behind the wall, what it meant to live in a city divided by it, and how the USSR declined and eventually fell.

‘Walled in: 13 August 1961’ in Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the Frontiers of Power by Patrick Major

On Sunday 13 August 1961, the wall was erected. This chapter, drawing on first-hand accounts, examines the initial reactions to the wall. As quoted in the chapter, one source describes the atmosphere of the day the wall went up as if “East Berlin was dead. It was as if a bell‐jar had been placed over it and all the air sucked out. The same oppressiveness which hung over us, hung over all Berlin. There was no trace of big city life, of hustle and bustle. Like when a storm moves across the city. Or when the sky lowers and people ask if hail is on the way.”

‘Escape tunnels, death, and the commemoration of the GDR’s hero-victims’ in Death at the Berlin Wall by Pertti Ahonen

Whilst taking very little direct action against the wall, the West did offer covert assistance to groups of East Berlin activists trying to provide escape routes for those who wanted it. One of these groups was led by Rudolf Müller and his associates, who had dug a tunnel underneath the wall and were busy ferrying through escapees when a group of East German soldiers surprised them. Though they escaped unscathed, the confrontation left a twenty-one year-old soldier – Egon Schultz – dead. This chapter examines how Schultz and his death became idealised and politicised by the East German state, transforming him into a hero-victim of the ‘socialist frontier.’

Berlin Wall on 16 November 1989. Photo by Yann. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Berlin Wall on 16 November 1989. Photo by Yann. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.‘The final phase, 1980–90’ in The Cold War: A Very Short Introduction by Robert J. McMahon

In the early 1980s the USSR was struggling with a war in Afghanistan, economic problems, and changes of leadership. From the middle of the 1980s, Soviet policy changes under Gorbachev ended the arms race and eventually relinquished control of Eastern Europe, bringing about an end to the Cold War and the USSR. This chapter looks at these final years of the Cold War, and explores the impact of Reagan and Gorbachev.

‘Gorbachev and the Reversal of History’ in The Rise and Fall of Communism in Russia by Robert Daniels

One of the key factors in the demise of the USSR was the USSR itself – or, rather, the reforms of Gorbachev. With twin policies of ‘perestroika’ (literally ‘restructuring’) and ‘glasnost’ (a policy calling for increased transparency in the Soviet Union), Gorbachev began the slow process toward democratization, dismantling the totalitarian psychology that had marked previous Soviet regimes and paving the way for progressive reforms.

‘The Collapse of the East German State’ in Nonviolent Revolutions: Civil Resistance in the Late 20th Century by Sharon Erickson Nepstad

Gorbachev’s policies, coupled with Hungary opening its borders to tens of thousands of East Germans, left the state with a crisis on its hands. When it decided to close its Hungarian borders, many citizens took to the streets to protest in what quickly became a large movement. Troops were sent to forcibly dispel the protesters, but their use of non-violent tactics made it difficult to justify the use of force, leading many of the troops to defy orders and defect. As the momentum for the movement grew, the strength of the state declined, leading to the fall of the wall and the eventual dismantling of East Germany.

‘The End of the Cold War’ in The Oxford Handbook of the Cold War by Nicholas Guyatt

Guyatt examines different historical perspectives on what caused the end of the Cold War, as well as the psychological, strategic, and political effects of its aftermath. Was it the press statement made by Gorbachev’s spokesman after the fall of the Berlin Wall that the tensions, which spread “from Yalta to Malta,” were over that marked the War’s official end? Perhaps the end came with Gorbachev’s statement to the United Nations announcing the end of Soviet Union military force to subdue the satellite states of the Warsaw Pact in 1988. The article explores these catalysts, among others, to present a comprehensive look at the War’s end and its resulting feelings of anxiety, fear, and “triumphalism” that abounded in Western Europe.

‘After the Fall of the Wall: Living Through the Post-Socialist Transformation in East Germany’ in After the Fall of the Wall: Life Courses in the Transformation of East Germany, ed. Martin Diewald, Anne Goedicke, and Karl Ulrich Mayer

As the wall came down, Germans were faced with a new challenge: how to forge a new, modern Germany. Linking the ‘macro’ worlds of institutional change to the ‘micro’ worlds of the lives and individual histories of its citizens, this chapter paints a fascinating portrait of once socialist and totalitarian state transitioning into the democratic Federal Republic of Germany.

‘Making Room for November 9, 1989?: The Fall of the Berlin Wall in German Politics and Memory’ in Twenty Years After Communism by Michael Bernhard and Jan Kubik

The dismantling of the wall, which was both a symbolic and literal division between East and West, could have served as a potent symbol for a unified Germany and played an integral part in its foundation myth, yet this was not the case. Why was this? Charting the reasons behind this – including the pre-existing German fields of memory left by its dark past – the chapter explains why the fall of the wall is likely to remain a “muted, tempered memory” in German politics.

What books would you add to our Berlin Wall reading list?

The post Reading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBig state or small state?Beethoven and the Berlin WallTrapped in the House of Unity

Related StoriesBig state or small state?Beethoven and the Berlin WallTrapped in the House of Unity

Big state or small state?

As we head towards another General Election in 2015, once again politicians from the Right and Left will battle it out, hoping to persuade the electorate that either a big state or small state will best address the challenges facing our society. For 40 years, Germans living behind the Iron Curtain in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) had first-hand experience of a big state, with near-full employment and heavily subsidized rent and basic necessities. Then, when the Berlin Wall fell, and East Germany was effectively taken over by West Germany in the reunification process, they were plunged into a new capitalist reality. The whole fabric of daily life changed, from the way people voted, to the brand of butter they bought, to the newspapers that they read. Circumstances forced East Germans to swap Communism for Capitalism, and their feelings about this change remain quite diverse.

Initially, East Germans flooded across the border, bursting with excitement and curiosity to see what the West was like – a ‘West’ that most had only known through watching Western television. For some, sampling a McDonald’s hamburger – the ultimate symbol of Western capitalism – was high on the to-do list, for others it was access to Levi’s jeans or exotic fruit that was particularly novel.

Going over the Berlin Wall, November, 1989, by gavinandrewstewart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Going over the Berlin Wall, November, 1989, by gavinandrewstewart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.At the same time as delighting in consumer improvements however, many East Germans felt ambivalent about the wider changes. Decades of state propaganda that painted Western societies as unjust places where homelessness, drugs and unemployment were rife, had left its mark, and many East Germans felt unsure and slightly fearful of what was to come.

From a position of full employment in 1989, 3 years after reunification 15% of East Germans were out of work. For those who struggled to put bread on the table after reunification, the advantages of having a wider range of goods to buy remained a largely theoretical gain. For others however, reunification led to greater freedom to pursue individual career choices that were not dictated by the state’s needs.

The end of East Germany’s ‘big state’ model led to the disbanding of its Secret Police, the Stasi, which had rooted out opposition to the State’s dictates. In the 1980s, 91, 000 people worked for the Stasi full time and a further 173, 000 acted as informers. To enforce socialism, they tapped people’s phones, wired their houses, trailed suspects and even collected smell samples in jars, so that sniffer dogs could track their movements.

For those who were made to feel vulnerable and afraid by a regime that watched, trailed and threatened to imprison them, such as political opponents, Christians, environmental activists or other non-conformists, the fall of the Wall and the end of the GDR most often brought relief: the Western set-up allowed for greater freedom of expression and greater freedom of movement.

Juggling on the Berlin Wall, by Yann Forget. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Juggling on the Berlin Wall, by Yann Forget. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.For the majority of East Germany though, this was not how they felt: since many say they had no idea of the extent to which the Stasi was intertwined with daily life, the end of the GDR did not bring with it a sense of relief. In fact, many East Germans felt that there were many things the West could learn from the GDR, and were resentful at the lack of openness to incorporating any East German policies or practices in the reunification process.

Leaving a Communist society behind and joining an existing Capitalist one brought concrete advantages for East Germans, but it simultaneously threw up a whole new set of challenges. For East Germans, unfamiliar cultural norms in reunited Germany, and also the absence of their usual way of life was profoundly unsettling. As one East German woman put it in a diary entry from December 1989:

“Everywhere is becoming like a foreign land. I have long wished to travel to foreign parts, but I have always wanted to be able to come home … The landscapes remain the same, the towns and villages have the same names, but everything here is becoming increasingly unfamiliar.”

This view was echoed my many East Germans, who were conscious that they, for example, dressed differently from their Western compatriots, didn’t know how to pronounce items on the McDonalds menu when they were ordering and didn’t know how to work coin-operated supermarket trolleys in the West. With the fall of the Wall, a whole way of life evaporated. The certainties on which day to day routines had been built ceased to exist.

Swapping Communism for Capitalism has prompted diverse reactions from East Germans. Few would wish to return to the GDR, even if it were possible. However while many delight in having greater individual choice about what they eat, where they go, what they do and what they say, they often also have a wistful nostalgia for life before reunification, where the disparity between rich and poor was smaller and the solidarity between citizens seemed to be greater.

The post Big state or small state? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBeethoven and the Berlin WallTrapped in the House of Unity1989 revolutions, 25 years on

Related StoriesBeethoven and the Berlin WallTrapped in the House of Unity1989 revolutions, 25 years on

November 8, 2014

Beethoven and the Berlin Wall

The collapse of the Berlin Wall twenty-five years ago this month prompted a diverse range of musical responses. While Mstislav Rostropovich celebrated the momentous event by giving a very personal, impromptu performance of Bach’s Cello Suites in front of the Wall two days after it had been breached, David Hasselhoff regaled Berliners from atop of what remained of the Wall on New Year’s Eve of 1989 with a glitter-studded rendition of his chart hit “Looking for Freedom.” The values ascribed in the West to the demise of communism were captured especially clearly in the role assigned to Beethoven during this heady period. From the free concert of the First Piano Concerto and Seventh Symphony that was offered to the newly-liberated East Germans by West Berlin’s flagship Philharmonic Orchestra three days after the fall of the Wall to Leonard Bernstein’s performances of the Ninth Symphony in the East and West of the city a month later, the message was consistent; Beethoven’s music was deemed to embody both the triumph of liberal democracy and the unification of a once-divided people. This symbolism was particularly apparent in Bernstein’s two concerts. While the emancipation of East Germany was reflected in his substitution of “Freiheit” (freedom) for “Freude” (joy) in the choral finale, the performances themselves staged a musical act of universal brotherhood; the orchestra compromised of musicians from both Germanies and all four of the Allied powers, and the events were broadcast live across the globe.

Such unironic celebrations of the universal Beethoven obscured the complex relationship that East Germans had with the composer. Cultural policy in the German Democratic Republic was driven by an Enlightenment conviction in the transformative, unifying, and humanizing powers of art, and from the outset the government had harnessed Beethoven as a pivotal figure in their plans to implement state socialism. His revolutionary zeal was hailed as a template for East German citizens and his heroic style as the ultimate expression of socialist ideals. This narrative persisted in official portrayals of the composer for the duration of the state’s forty-year existence. Beyond the sphere of official rhetoric, however, Beethoven’s reception was far more conflicted. As the promised socialist utopia failed to materialize and the chasm widened between the rhetoric of revolution propagated by the party and the realities of life in the socialist state, Beethoven was approached increasingly not as an iconic statesman but as a vehicle for exploring of the problematic position of art and the artist in East German society.

An early example of this phenomenon can be observed in Reiner Kunze’s 1962 poem “Die bringer Beethovens” (the bringers of Beethoven), in which Beethoven serves as an allegory for totalitarianism rather than Enlightenment humanism. Published in the 1969 collection sensible wege, the poem relates the battle of “the man M.” against the faceless “bringers of Beethoven,” who inculcate the masses by subjecting them to a recording of the Fifth Symphony. The man attempts to resist this indoctrination by retreating inside his house only to have the bringers first fix loudspeakers over his windows, and then force their way in armed with the record. He responds by beating them with an iron ladle. A trial follows at which he is judged to be redeemable. Redemption, however, inevitably lies in the Fifth Symphony to which he is sentenced to listen. His punishment kills him, but death provides no release: at his funeral his children request that none other than the Fifth Symphony be played.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, November 1989. Photo by Gavin Stewart. CC BY 2.0 via gavinandrewstewart Flickr.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, November 1989. Photo by Gavin Stewart. CC BY 2.0 via gavinandrewstewart Flickr.In the years that followed, alternative readings of Beethoven became increasingly prominent. Characteristic, for instance, is Reiner Bredemeyer’s short piece for orchestra and piano Bagatellen für B. of 1970, which sets the opening chords of the “Eroica” Symphony against the Bagatelles op. 119, no. 4 and op. 126 no. 2. Bredemeyer’s focus on the Bagatelles was a pointed challenge to the socialist Beethoven. Grounded in the femininity of the nineteenth-century drawing room rather than the revolutionary public sphere, these piano miniatures represented a significant affront to the one-dimensional heroic portrayals of the composer that dominated in the German Democratic Republic. A similar confrontation can be observed in Horst Seemann’s 1976 biopic Beethoven – Tage aus einem Leben. Here Beethoven is depicted not as a socialist deity, but as a very human and conflicted individual, plagued by failed love affairs, domestic ineptitude, and an inability to reconcile himself with society around him.

Driving these works was a pointed questioning of the social and political efficacy of art. Striking in this context are the opening scenes of Seemann’s film, which cut between a live performance of Beethoven’s “Battle Symphony” and a gory re-enactment of the Battle of Vittoria itself. Far from heralding the symphony as a revolutionary force, however, this juxtaposition of concert hall and battlefield exposes the fallacy of the Beethoven myth. Graphic images of wounded and dying soldiers sit uncomfortably with frames of the concert audience, who clap delightedly in response to the music and eat chocolates as they listen. Art serves here not as a harbinger of political change but simply as a mode of entertainment.

The demise of the German Democratic Republic did little to quell this disillusioned perspective, and the triumphant narratives of Beethoven that resurfaced in 1989 stood decidedly at odds with the prevailing mood among East German artists. Crucially, the euphoria that accompanied the fall of the Wall was tempered for the latter group by a sense of a loss, a loss not for their repressive country but for the ideals and hopes that this country had once promised. Key among these was the notion that art could serve as a force for good and play a profound role in effecting social reform. From this perspective, the failure of the German Democratic Republic was not just a failure of socialism. It was also a failure of art. As Bredemeyer observed in a 1992 interview with reference to the East German composer Hanns Eisler: “If music is an instrument of intervention in the sense of Eisler … then I have to say, very well then. Eisler lost, I too; it doesn’t work anymore.”

Headline image credit: Partly destructed Berlin Wall with border police, view from west, Brandenburg Gate in the background in November 1989. Photo by Stefan Richter. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beethoven and the Berlin Wall appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTrapped in the House of UnityInternational Day of Radiology and brain imagingThe Road to Ypres

Related StoriesTrapped in the House of UnityInternational Day of Radiology and brain imagingThe Road to Ypres

Jawaharlal Nehru and his troubled legacy

Jawaharlal Nehru’s contribution would have had a much longer life had not members of his family systematically tarnished it. From breaking the Congress organization in 1969, to the declaration of Emergency, to the initiation of caste wars, to the encouragement of Sikh militancy, to the decision on Shah Bano, to the opening of the Babri Masjid, and the list goes on, it was Nehru’s bloodline that most effectively downgraded his memory. Experts and commentators connived in this for they were blindsided by the family connection and failed to see the break that was being repeatedly wrought on Nehru’s memory first by his daughter, then his son and then his daughter-in-law and great grandson. So when the time came, and come it would, the haters and baiters of the first Prime Minister easily positioned his memory in the short hairs of their blunderbusses and shot it down.

As it is, Nehru tripped himself up on a number of policies he had staked his reputation on. In times of economic crisis or border threats — as from China — he sidestepped non-alignment and turned to America first. Or, when it came to socialism, he made it known that he would never stand for the Soviet model and preferred the mixed economy instead. That this position was supported by India’s fledgling entrepreneurs of the time only made Nehru’s claim to be a socialist”’ somewhat contrived. Even if socialism were to be interpreted as “welfare statism”, he did precious little on issues like universal health and education.

Nehru, however, played a sterling role in keeping India together in its most critical years after Independence. He was not alone in this, but without his whole hearted support to the making of the Indian Constitution, we would have been a poorer Republic. He weighed in heavily in favour of anti- untouchability, minority rights, and the abolition of feudal privileges which, together, make our Constitution so outstanding. India was a young Republic in 1950, but it looked, talked and walked like a seasoned democratic nation-state. True, he was not alone in this, but as Prime Minister, it was Nehru, more than anybody else, who fleshed out these most singular aspects of our Constitution. It would have been the easiest thing to renege on them given the tensions and uncertainties India faced in the early post- Independence years, but Nehru remained firm.

What made Nehru stand out was his insistence on the principle of fraternity. Unfortunately, it is not difficult to undermine him on this score as fraternity is fashioned on intangibles; it is not made of brick and mortar, nor can it be measured monetarily. Yet, without this all important attribute, neither liberty nor equality makes much sense- they actually ring hollow. Nehru’s contribution to fraternity came through in his insistence on secularism which went all the way from anti-casteism to anti religious sectarianism. He made no compromises on any of these but, unfortunately for him, these can easily be shafted in the name of political expediency. And this is exactly what his daughter, grandson and the succeeding generation did. Secularism has been the single greatest casualty in the five decades of Congress rule after Nehru. It is for this reason that ‘secularism’ today has become the butt of ridicule, and even half literates have a field day in mocking it.

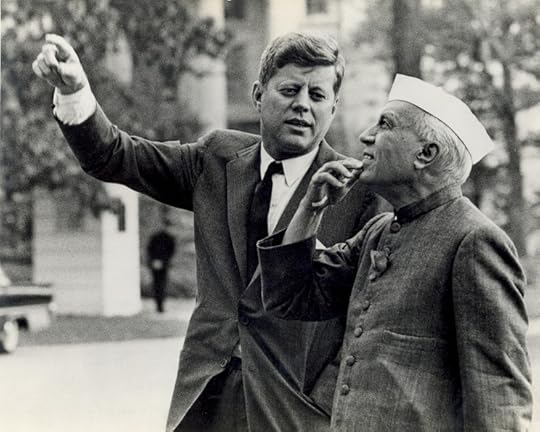

US President John F. Kennedy speaks with Prime Minister Jawarharlal Nehru at the White House, 1961, from the US Embassy New Delhi. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

US President John F. Kennedy speaks with Prime Minister Jawarharlal Nehru at the White House, 1961, from the US Embassy New Delhi. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.Nehru’s industrialization programme required a long gestation period which people, with a limited time horizon, found difficult to accept. Further, for the mixed economy to succeed, state enterprises had to be super efficient in infrastructure creation. Without laying out this groundwork it would be difficult for the other half of the mixed economy to come of age. This was the true meaning of self-reliance as Nehru saw it and all autarkic versions of it put out by his enemies, and some admirers too, are contrary to this vision. None of this could be accomplished overnight by token gestures and oratorical flourishes; they all required careful calculation, and hard core research and development. Mistakes were made, plans recalibrated, Constitutional impasses overcome and before any of these could be firmed up, Nehru was gone.

Perhaps his record as Prime Minister would have been different had he lived longer. True, he had set himself a gigantic task by standing up for India’s economic sovereignty and battling ceaselessly against traditional prejudices. Yet, sadly and oddly, he failed most monumentally in his lifetime not so much on these grounds as he did because he was an extremely prickly nationalist. Whenever India’s physical integrity faced a threat, even imaginary ones, he was unable to take a proper democratic decision. He blundered on Kashmir and we are still paying for it; he totally miscalculated on China; he did not understand the Sikhs or the sentiments that had been stirred up in the North-East. One could possibly excuse him for these sins for India had just emerged as a Nation-State and the fear of Balkanization was very real in the minds of many. In fact, he feared the breakup of India so profoundly that he was even against the formation of Maharashtra and Gujarat as well as the unilingual state of Punjab.

That is not quite all. Nehru could have set an example and kept his daughter out of politics instead of making her the Congress President. This was the first big nepotistic step in Indian politics which was later justified on all kinds of specious grounds by many Nehru acolytes. The other unpardonable thing he did was to choose Teen Murti, the biggest house in the capital, as his official residence. This encouraged pomp and splendour among ministers and bureaucrats, and this strain has only become worse over time. The subsequent conversion of Teen Murti as Nehru Memorial Museum and Library has also set up a negative precedence. Since then, children of many departed Prime Ministers and political heroes have turned their dead ancestor’s home into public monuments.

In balance, Nehru’s legacy is on its way out. It is, however, in our national interest to keep alive his devotion to the cause of “fraternity”. This can best be done if we do not see the regimes of Indira or Rajiv or Rahul as a continuation of what Nehru stood for. If ever fraternity truly becomes relevant in our country again, nobody will remember that Jawaharlal Nehru was its prime mover once upon a time.

Headline image credit: Lord Mountbatten swears in Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru as the first Prime Minister of free India at the ceremony on August 15, 1947. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Jawaharlal Nehru and his troubled legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDeath of a DemocratThe economic consequences of NehruEleanor Roosevelt’s last days

Related StoriesDeath of a DemocratThe economic consequences of NehruEleanor Roosevelt’s last days

Furphies and Whizz-bangs

In 2015, Australia will mark the centenary of the landing of Australian and New Zealand soldiers at what came to be known as Anzac Cove (Gaba Tepe). For Australia, this event has been a significant marker of nationhood, and the legacy of Anzac plays an important role in Australian cultural and political life. The experience of the First World War also had a lasting impact on language.

We can trace the language of Australians during the war years through a variety of sources, including letters, diaries, trench publications, and newspapers. These sources attest to the impact the war had on both British English and Australian English. Australian newspapers took note of the emerging lexicon of war, printing glossaries and articles that explained the military terminology that readers might encounter in the lengthy descriptions of battles and actions being reported. Words like emplacement, grenade, mortar, and redoubt were new or unfamiliar to the average Australian reader, and explanations were necessary. As the OED’s ‘100 words that define the First World War’ shows, the war generated a language of modern warfare that forever changed the lexicon.

It was also evident as the war progressed that a lot of slang was being generated. Australian soldiers used a variety of terms to describe aspects of army life: for example, army biscuits were variously forty-niners, Anzac wafers, or concrete macaroons, and jam or treacle was referred to as flybog. Soldiers were also introduced to a range of British army slang terms, which they quickly adopted into their vocabulary: for example, rooty for bread, iron rations for emergency rations, short arm parade for a venereal disease inspection, and gravel-crushing for route marching – this last being one of many terms reflecting the tedious life of the infantryman. Many terms for information or rumours were generated as well, reflecting a general concern about a lack of information about the war or likely activities: these included terms such as dinkum oil, good oil, and furphy, all of which remained popular in Australian English after the war.

The experience of the battlefield also produced a range of terms. There was a particular variety of terms for weapons, shells, and guns: Black Maria, whizz-bang, Jack Johnson, woolly bear, and Beachy Bill are just a few of them. Death and the fear of death generated its own vocabulary. To die was to be put into cold storage, to go west, or chuck a seven. While there were some words particular to the Australians (for example, possie for position, king-hit for a significant wound, and stoush for a fight), but the fact that much of the vocabulary of the war was shared by the Anglophone armies attests to their common experiences.

Men, women and children line the streets to watch the procession of the 41st Battalion through Brisbane on Anzac Day, 1916. State Library Queensland. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Men, women and children line the streets to watch the procession of the 41st Battalion through Brisbane on Anzac Day, 1916. State Library Queensland. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Australian soldiers liked to believe in their own unique creativity when it came to language. Soldiers’ publications during the war served to promote a particular image of the Australian soldier as brave, fearless, with a disregard for authority, and ready to crack a joke whatever the circumstances. While this didn’t always match reality, it became part of an emerging ‘Anzac legend’. Language played a role in this: Australian soldiers were inveterate users of slang who spoke a language few outsiders could comprehend, and they often used this to poke fun at others. One humorous item published in a Western Australian newspaper described an Australian soldier meeting King George V, and responding to his questions with colloquialisms such as bonzer and ribuck. It ended with the King commenting: ‘I’m no snide mug at languages … but I’d give a pot of dinkum dough if I could speak Australian.’ (Perth Daily News, 28 January 1919, p. 8)

During the war years, a language of commemoration also began to emerge, which developed more fully after the war. The first Anzac Day (initially also known as Gallipoli Day), was held in 1916, marking the anniversary of the landing at Anzac Cove. Subsequent Anzac Days would incorporate features such as the Anzac service (or Anzac Day service), Dawn service, and the Anzac Day march. Anzac Day has become a day of central importance in Australia.

The First World War had a lasting effect on the English lexicon. It also had a lasting effect on Australian English, and more importantly perhaps, language became one of the vehicles by which an emerging Australian national identity with the Anzac legend at its core began to take shape. This has been a contentious aspect of Australian public culture and discussions about identity, but it is undoubtedly true that the centenary of the Anzac landing will once again emphasise the significance the war has had for Australia.

This article originally appeared on the Oxford Australia blog.

The post Furphies and Whizz-bangs appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Road to YpresEleanor Roosevelt’s last daysDeath of a Democrat

Related StoriesThe Road to YpresEleanor Roosevelt’s last daysDeath of a Democrat

A reading list of Roman classics

Roman literature often derived from Greek sources, but took Greek models and made them its own. It includes some of the best known classical authors such as Ovid and Virgil, as well as a Roman emperor who found time to write down his philosophical reflections.

Saint Augustine’s Confessions by Saint Augustine

Augustine was a gifted teacher who abandoned his secular career and eventually became bishop of Hippo. His Confessions are a remarkable record of his wrestlings to accept his faith, his struggles to overcome sexual desire and renounce marriage and ambition. His final moment of conversion in a Milan garden is deeply moving.

On Obligations by Cicero

The great Roman statesman Cicero lived at the center of power. He was an advocate and orator as well as philosopher, who met his death bravely at the hands of Mark Antony’s executioners. On Obligations was written after the assassination of Julius Caesar to provide principles of behavior for aspiring politicians. Exploring as it does the tensions between honorable conduct and expediency in public life, it should be recommended reading for all public servants.

The Rise of Rome by Livy

The Roman historian Livy wrote a massive history of Rome in 142 books, of which only 35 survive in their entirety. In the first five books, translated here, he covers the period from Rome’s beginnings to her first major defeat, by the Gauls, in 390 BC. Among the many stories he includes are Romulus and Remus, the rape of Lucretia, Horatius at the bridge, and Cincinnatus called from his farm to save the state.

On the Nature of the Universe by Lucretius

Lucretius lived during the collapse of the Roman republic, and his poem De rerum natura sets out to relieve men of a fear of death. He argues that the world and everything in it are governed by the laws of nature, not by the gods, and the soul cannot be punished after death because it is mortal, and dies with the body. The book is an astonishing mix of scientific treatise, moral tract, and wonderful poetry.

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was probably on military campaign in Germany when he wrote his philosophical reflections in a private notebook. Drawing on Stoic teachings, particularly those of Epictetus, Marcus tried to summarize the principles by which he led his life, to help to make sense of death and to look for moral significance in the natural world. Intimate writings, they bring us close to the personality of the emperor, who is often disillusioned with his own status, and with human life in general.

Metamorphoses by Ovid

The Metamorphoses is a wonderful collection of legendary stories and myth, often involving transformation, beginning with the transformation of Chaos into an ordered universe. In witty and elegant verse Ovid narrates the stories of Echo and Narcissus, Pyramus and Thisbe, Perseus and Andromeda, the rape of Proserpine, Orpheus and Eurydice, and many more.

Agricola and Germany by Tacitus

Tacitus is perhaps best known for the Histories and the Annals, an account of life under emperors Tiberius, Claudius and Nero. The shorter Agricola and Germany consist of a life of his father-in-law, who completed the conquest of Britain, and an account of Rome’s most dangerous enemies, the Germans. They are fascinating accounts of the two countries and their people, the northern ‘barbarians’. Later, German nationalists attempted to appropriate Germania in support of National Socialist racial ideas.

Georgics by Virgil

The Georgics is a poem of celebration for the land and the farmer’s life. Virgil doesn’t romanticize, rather he describes the setbacks as well as the rewards of working the land, and provides memorable descriptions of vine and olive cultivation, raising crops, and bee-keeping. It is both a practical agricultural manual and allegory, and brings the ancient rural world vividly to life.

Aeneid by Virgil

The story of Aeneas’ seven-year journey from the ruins of Troy to Italy, where he becomes the founding ancestor of Rome, is a narrative on an epic scale. Not only do Aeneas and his companions have to contend with the natural elements, they are at the whim of the gods and goddesses who hamper and assist them. It tells of Aeneas’ love affair with Dido of Carthage and of Aeneas’ encounters with the Harpies and the Cumaean Sibyl, and his adventures in the Underworld.

Heading image: Roman Virgil Folio. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A reading list of Roman classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA reading list of Ancient Greek classicsSix classic tales of horror for HalloweenAncient voices for today [infographic]

Related StoriesA reading list of Ancient Greek classicsSix classic tales of horror for HalloweenAncient voices for today [infographic]

November 7, 2014

What could be the global impact of the UK’s Legal Services Act?

In 2007, the UK Parliament passed the Legal Services Act (LSA), with the goal of liberalizing the market for legal services in England and Wales and encouraging more competition—in response to the governmentally commissioned ‘Clementi’ report finding the British legal market opaque, inflexible, overly complex, and insulated from innovation and competition.

Among other salient provisions, the LSA authorized the creation of ‘Alternative Business Structures,’ permitting non-lawyers to take managerial, professional, and ownership roles, and explicitly opening the door to law firms raising capital from outside investors and combining with other professional services firms—even listing publicly on a stock exchange. All this has made the UK’s £25-billion/year legal marketplace “one of the most liberalized in the world,” according to the Financial Times.

Gavel and scales of justice, by pennstatenews. CC BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Gavel and scales of justice, by pennstatenews. CC BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.Our question for today is whether this bracing demolition of guild-like protectionist rules will stop at the English coastline—more specifically, whether it will leap the North Atlantic to the US, the single largest legal marketplace in the world by far, now just north of $250-billion (£150-billion) per year. It would be the irresistible force meeting the immovable object.

Two predictions may be made without fear of contradiction.

First is that the American Bar Association (ABA), with its 400,000 members, will resist any incursions into US lawyers’ monopoly over legal services with every weapon at their disposal short of, perhaps, violence. A core function of the ABA is promulgating the “Model Rules of Professional Conduct,” which have the force of law in 49 states. ABS’s would flatly offend Rule 5.4(a), prohibiting fee-sharing with a non-lawyer, and 5.4(d), prohibiting practicing in any organization where a non-lawyer owns an interest.

We know ABA opposition will be fierce because it happened once before. In 2000, the ABA’s governing House of Delegates entertained a proposal to amend the ethical rules to permit “multidisciplinary practices” (consider them the functional equivalent of the UK’s ABS’s). This went down to “crushing defeat” as the state bars of Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Florida, and Ohio joined in “strident” denunciation of the heresy of fee sharing and vehement “reaffirmation of the core values of the law of lawyering.”

The horrified opposition cited fears of the invasion of the profession by predatory investors prepared to sacrifice clients on the altar of profits. Adam Smith – or for that matter Peter Drucker – might be skeptical of the long-run viability of a business premised on putting its clients last, but be that as it may, I’m reminded of the remark by American Lawyer editor-in-chief Aric Press some years ago that the magazine’s creation of the notorious profits-per-partner scorecard for law firms “did not introduce the profession to greed.”

Themis, by RaeAllen. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Themis, by RaeAllen. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.Lest you believe the world might have moved on in the intervening decade and a half, and that we have learned guilds tend to collapse of their own sclerosis by now, permit me to disabuse you of that hope. Earlier this year the state bar of Texas issued a binding opinion that law firms there may not include the terms “officer” or “principal” in the job title of non-lawyer employees. “Don’t mess with Texas,” indeed.

Finally, note that the states leading the charge here are six of the ten largest in the US, comprising nearly one-third of the country’s total population. Their opposition will not be trifling: They have ground troops.

My second prediction: A barrier which will effectively halt the flow of money and ideas at any essentially arbitrary line—such as a national border—has yet to be invented. If you doubt this, I refer you to the extended and unblemished track record of abject failure in US attempts to control or limit political campaign financing.

If globalization stands for anything, it is the accelerating movement of capital, people, and ideas across jurisdictional borders – movement which, despite hiccups and speed bumps, is becoming steadily more frictionless and irreversible. In the case of Law Land, this would mean a UK-based ABS coming to our shores (and I devoutly hope their beach-head would be little old New York – I want a front-row seat to this brawl) with a checkbook and an appetite for expansion.

The moment the announcement is made, I predict that two inter-related dynamics would begin playing themselves out.

First, managing partners of US-based firms would go through the famous stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and ultimately acceptance. Acceptance here could only translate into a demand for a “level playing field” for their firms. Since, then as now, they presumably will lack the votes in Parliament to repeal the LSA, that would mean adopting a functional equivalent – permitting MDP’s – here in the US. And a level playing field is, after all, a bedrock imperative of fairness. They would be making a nice argument.

Second, someone would sue. It matters not whether it be the ABS suing for permission or an aggrieved US lawyer suing for prohibition; a “real case or controversy” would be presented for adjudication. I’m not going to practice antitrust or constitutional law in these pages, but my strong intuition is that a challenge to the bar prohibitions on non-lawyer involvement would prevail on a combination of antitrust and commerce clause claims (the “commerce clause,” Article I, §8.3 of the US Constitution, prohibits unduly burdensome state interference with interstate commerce, and since at least the era of the New Deal it has been given extraordinarily wide reach).

But the outcome really shouldn’t be determined by tidy legalities. At root, it should come down to a socioeconomic and ethical choice driven by which of these views of the legal profession is on the right side of history.

Do we prefer the cozy walled precincts of the guild, righteously defending its economic rents under the cloak of claims of “the best interest of the client,” “confidentiality,” “privilege,” and so forth? Or do we prefer Schumpeter’s, or Silicon Valley’s, bracing call for “creative destruction,” as messy and fraught with failed experiments as we can be sure it will be?

I certainly know where my heart lies, and it’s with the best interests of the client truly and rightly understood. Unleash the market’s Darwinian selection process.

The post What could be the global impact of the UK’s Legal Services Act? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesI miss IntradeFood insecurity and the Great RecessionFood insecurity and the Great Recession - Enclosure

Related StoriesI miss IntradeFood insecurity and the Great RecessionFood insecurity and the Great Recession - Enclosure

Death of a Democrat

On 17 and 18 December 1961, on Nehru’s orders, Indian troops marched into Goa, an area of about 1,500 square miles on the country’s western coast, to ‘liberate’ it from the Portuguese, who had ruled the territory since 1510. Condemnation was swift, both from critics at home and abroad.

In the election campaign that took place immediately after the invasion Nehru was able to strike a patriotic chord, capitalising on ‘restoring Goa to the Motherland’. His ruling Congress party was re-elected in 361 out of 494 parliamentary seats and was back in power for a third successive term. Yet, in spite of the criticism, no one could foresee that the triumphant note sounded over Goa also marked the countdown to the end of Nehru’s leadership. The military conflict with China that broke out in full force in October 1962 would be momentous for India, bringing about extraordinary tribulations for Nehru. In its aftermath came growing tensions with Pakistan, political unrest in the Kashmir valley and domestic criticism and challenges to his political authority.

In November 1961, just before the Goa campaign, in response to stinging criticism in parliament, Nehru and his defence minister, V.K. Krishna Menon, had taken steps to reclaim from the Chinese some territory by setting up forward posts. Arguably, this much debated ‘forward policy’ inflamed the situation. In August 1962 Nehru informed parliament that Indian soldiers had re-occupied around 4,000 sq km of some 19,000 sq km of territory that the Chinese had taken.

Yet, when the Chinese strike came on 19 and 20 October, the Indian leadership called it an unprovoked and sudden offensive, a ‘Himalayan Pearl Harbor’. A month later, on 21 November, a unilateral ceasefire was called by the Chinese; by then they had wrestled over 23,200 sq km of territory from India, retaining 4,000 sq km in the Ladakh region.

The Himalayan War was a dramatic turning point for Nehru’s leadership. Although India and the Soviet Union had signed a deal in August 1962 for MiG-21 fighter planes, these never materialized during the hostilities, leading to speculation that the Soviets would not permit the use of their weapons against another Communist country.

Nehru was upset that US and British offers of military help came with strings attached. India was now forced to accept outside mediation and to open a dialogue with Pakistan over the highly contentious issue of Kashmir. Both the US and UK governments had used the Himalayan crisis to put pressure on India to make concessions to Pakistan and to settle the Kashmir issue. Nehru’s carefully nurtured policy of non-alignment suffered a setback and India’s stature on the global stage, which he had worked so hard to build, diminished.

In April 1963 the Congress Party lost three critical parliamentary by-elections. In parliament’s monsoon session Kripalani moved a motion of no confidence, the first such challenge to his leadership Nehru had faced since 1947. Although defeated, the motion was deeply symbolic of the shifting political dissatisfaction with the government.

Anxious stirrings within the Congress party reflected the mood. The Congress party heavyweights realised that they had to face up to the inevitable question: ‘After Nehru Who?’ The party had to survive, take care of its electoral interests and move on in uncertain times. Some of these men, including Kamaraj, met quietly in October 1963 in the temple town of Tirupati in southern India to form what came to be known as the ‘Syndicate’, an informal leadership collective to manage the question of political succession.

The outbreak of war with China brought another hopelessly tangled issue to Nehru’s urgent attention, that of Kashmir. Talks began between the Indian minister Swaran Singh and the Pakistani foreign minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Held over six prolonged rounds between December 1962 and May 1963, the talks proved unproductive and only hardened attitudes on both sides. American and British diplomatic efforts now turned to getting Nehru and Ayub Khan to accept third party international mediation to solve the Kashmir deadlock, a proposal that went against the grain of Nehru’s creed of non-alignment.

Meanwhile, in Kashmir – from where Nehru’s ancestors came and a region with which he identified strongly – the political crisis deepened. People regarded the detention of Abdullah, imprisoned for 11 years without trial, as being part of a political vendetta. To aggravate the situation, on 26 December 1963 a crisis arose due to the mysterious theft of a relic of the Prophet Muhammad from the shrine of Hazratbal in Srinagar.

The Hazratbal incident had far-reaching consequences. Sectarian violence broke out Nehru dreaded the vicious cycle of Hindu-Muslim violence, with its inevitable displacement of people from their homes. He had lived through the horrors of Partition. To his distress it had begun once again.

Through these turbulent months, Nehru kept his nerve. Even in the gloomiest moments of the war he did not seek scapegoats. Neither did he conceal his grief for the loss of Indian soldiers. In January 1963 he is said to have been moved to tears before more than 50,000 people when the singer Lata Mangeshkar performed the patriotic Hindi elegy ‘Aye Mere Watan Ke Logon!’ (Oh the People of My Country!). During this time he continued to seek the counsel of President Radhakrishnan and of close Cabinet colleagues such as Shastri, T.T. Krishnamachari and Y.B. Chavan, who took over the defence portfolio from Menon.

On 7 January 1964 Nehru suffered a mild stroke at Bhubaneswar in eastern India. Arrangements were now made to lighten Nehru’s responsibilities. Lal Bahadur Shastri was appointed to the Cabinet as minister without portfolio. Shastri was to ‘look after’ Nehru’s work relating to foreign affairs, planning and atomic energy, besides handling all important matters requiring the prime minister’s attention. Nehru soon recovered and from March onwards resumed attending parliament.

On the morning of 27 May after returning in apparently good health from a few days’ holiday at Dehra Dun, Nehru suffered a sudden heart attack. He died later that afternoon.

Among the mourners was a tearful Sheikh Abdullah, who, on learning of Nehru’s death, had cancelled his tour of the Pakistani-held ‘Azad Kashmir’ and rushed back to Delhi.

Deeply respectful of the norms and processes of a young democracy, Nehru always believed that the question of succession should be decided by the party and the people after he was gone. The political transition that followed his death was remarkably smooth. With the support of the Syndicate, Lal Bahadur Shastri was unanimously elected Nehru’s successor.

Shastri’s unexpected death in January 1966 brought about yet another political succession. This propelled to the fore Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi – the beginning of a political dynasty, of which Nehru would have strongly disapproved for a democratic country such as India.

A version of this article originally appeared in History Today.

The post Death of a Democrat appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe economic consequences of NehruTrapped in the House of UnityEleanor Roosevelt’s last days

Related StoriesThe economic consequences of NehruTrapped in the House of UnityEleanor Roosevelt’s last days

Trapped in the House of Unity

I emerged after a long day in the soundproofed cabins at the back of the reading room in the onetime Institute of Marxism-Leninism, which pieces of black sticky tape now proclaimed as the ‘Institute of the Labour Movement’. It was spring 1990 and I was in East Berlin, as one of the first western researchers into the German Democratic Republic. Normally, I would have seen fellow researchers gathering their papers, and archive staff ushering them gently out. But this evening the main reading room was in complete darkness.

It soon became apparent that I was locked in. I could mentally see the red plasticine seal over the lock on the other side of the door, with the logo of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany pressed into it, which staff dutifully unpeeled each morning. What to do? Locked into a building I had spent so long trying to get into! Furtively, I tried the card catalogue, just to see if there was a secret archive they were keeping from me. Locked too. My stomach began to rumble. I didn’t think I could pull an all-nighter, even for scholarship. I cast around for a means of escape. A telephone directory was lying on the desk with ‘Central Committee – for the use of the Comrades only!’ handwritten across the top.

I scanned the various numbers until I came across one for the porter. I dialled. A man replied in a thick Berlin accent. I explained that I was locked in the main reading room. Could he come and let me out? After some grumbling he said he would see. After twenty minutes of anxious waiting, I phoned again. I was in the ‘Benutzersaal’, on the fifth floor. There was a baffled silence at the other end of the line, before my would-be rescuer intoned, chillingly: ‘There is no fifth floor.’

It transpired that I had been talking to a man in a different building entirely, in the Karl Liebknecht Haus (named after one of the Spartacist martyrs of 1919). After a series of proxy phone calls, I eventually reached a rather flustered wife of the Institute director, and was liberated by the deputy-head archivist at 10pm. Locking in visitors was ‘so bad for business’, apologised Frau Pardon.

It turned out that the Institute had been down-sizing as the communist state continued to totter. Security staff had been let go, and the archivists had not quite learned the ropes. When I had arrived in February, entering the building had been like passing a checkpoint. A ‘Vopo’, or People’s Police officer, had scrutinised my passport, after the head archivist had come down with the stamp which made me an official visitor of the Central Party Archive. Ordnung muß sein!

This had not been without its difficulties. At the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall the previous November, I had been doing my Oxford DPhil at West Germany’s main GDR think-tank in Mannheim. All of its staff had been routinely banned from East Germany as ‘bourgeois’ historians. But following the people’s storming of the Stasi headquarters in January, sudden invitations had appeared. Please come and use the archive! Perhaps we were going to be used as human shields to ward off the mob’s fury should it turn on the party. Would we have to throw ourselves on the files to stop them from being defenestrated?

Beyond the Vopo check-point was like a dismantled stage-set. The slogan ‘Marxism-Leninism is not a dog..’ adorned the rear wall. A workman on a step-ladder had just unscrewed the final two letters ‘..ma’. A bust of Ernst Thälmann, the Weimar communist leader murdered by the Gestapo at Buchenwald in 1944, had been unceremoniously parked in the corner.

A 217 class REKO tram in Friedrichstrasse, January 1990, photo by Felix O. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A 217 class REKO tram in Friedrichstrasse, January 1990, photo by Felix O. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.But as a foreigner, and especially as a ‘Wessi’, I was still escorted everywhere. My minder was ‘Rudi’, an affable, bespectacled man in late middle age with his jet-black hair brylcreemed back, who made a point of telling me jokes about the ex-East German party leader, Erich Honecker, but only when no-one else was around. His job included accompanying me to the canteen every day, until we agreed that I knew the way. And he stopped.

I also learned about the history of the building. In the Weimar Republic it had been a Jewish-owned department store, but had been ‘Aryanised’ by the Nazis in 1939. Then it had become Hitler Youth Headquarters, before being turned over by the Soviets to the East German party in 1946. But it still had the form of a department store, with lifts at the back of the main lobby, which must once have ascended to soft furnishings, next stop Politbüro. But now the building was reverting to type. The Vopo was moved from the porter’s cubicle, and a tuck shop selling Coke and Snickers moved in.

Later that spring, in May, the Institute closed at short notice. The former Central Committee on the far side of the Alexanderplatz, housed in the old Reichsbank building – the equivalent of the Bank of England – had been forced to vacate its premises, since the West German Bundesbank was reclaiming it. (German history knows its continuities when it wants to.) The Central Committee files would have to find temporary refuge in the Institute, which was turned into a depository. But I managed one last mass photocopying bonanza by changing money illicitly on the black market at the Bahnhof Zoo in West Berlin: German historians know when to exploit the present too – für die Wissenschaft!

And then the Institute itself was finally evicted in the mid-1990s. For the next twenty years it remained a derelict reminder of the past, an inlaid relief profile of one of the Party leaders, Otto Grotewohl, the only outside reminder of previous occupancy. Yet the last time I looked, it had finally discovered its post-communist identity: ‘Soho House Berlin’, a private members’ club in the heart of the city, whose website simply states that the building has a ‘remarkable history’. So, indeed.

The post Trapped in the House of Unity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInternational Day of Radiology and brain imagingThe Road to Ypres1989 revolutions, 25 years on

Related StoriesInternational Day of Radiology and brain imagingThe Road to Ypres1989 revolutions, 25 years on

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers