Oxford University Press's Blog, page 739

November 14, 2014

Immigration and emigration: taking the long-term perspective for our better health

Immigration is an inflammatory matter and probably always has been. Immigrant groups, with few exceptions, have to endure the brickbats of prejudice of the recipient population. Emigration, by contrast, hardly troubles people — but the departure of one’s people is not a trifling matter. I wonder why these differential responses occur. It seems to me that humans are highly territorial and territory signifies resources and power. Immigration usually means sharing of resources, at least in the short-term, while emigration means more for those left behind and brings hope of acquiring even more from overseas in the long term. This might explain why those most needy of settled immigrant status — asylum seekers, the persecuted or denigrated, and the poor — are most resisted while those least in need of immigration status, such as the rich, are often welcomed.

Notwithstanding, consternation about migration it is rapidly leading to diverse, multiethnic and multicultural nations across the world. Many people dislike the changes this brings but it is hard to see what they are to do except change themselves. The forces for migration are strong, for example, globalization of trade and education, increasing inequalities in wealth and employment opportunities, and changing demography whereby rich economies are needing younger migrants to keep them functioning.

Whether you are a migrant (like me) or the host to migrants it is wise to remember that migration is a fundamental human behavior that is instrumental to the success of the human species. Without migration Homo sapiens would be confined to East Africa, and other species (or variants of humans — all now extinct) would be enjoying the bounties of other continents. Surely, migration will continue to bring many benefits to humanity in the future.

Harmony Day by DIAC images. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Harmony Day by DIAC images. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons My special research interest is in the comparative health of migrants and their offspring, who together comprise ethnic (or racial, as preferred in some countries) minority groups. There is a remarkable variation in the pattern of diseases (and the factors that cause diseases) among migrant and ethnic groups and very often the minorities are faring better than the recipient populations. Probing these patterns scientifically, especially in the discipline of epidemiology, which describes and interprets the occurrence of disease in large populations, helps in understanding the causes of disease. There are opportunities to apply such learning to improve the health of the whole population; migrants, minorities and settled majority populations alike.

Let me share with you three observations from my research areas that help illustrate this point, one concerns heart disease and diabetes, another colorectal cancer, and the third smoking in pregnancy. Coronary heart disease (CHD) and its major co-disease type 2 diabetes (DM2) have been studied intensively but still some mysteries remain. The white Scottish people are especially notorious for their tendency to CHD. Our studies in Scotland have shown that the recently settled Pakistani origin population has much higher CHD rates than white Scottish people. Amazingly, the recently settled Chinese origin population has much lower rates of CHD than the white Scottish people. These intriguing observations raise both scientific questions and give pointers to public health. If we could all enjoy the CHD rates of the Chinese in Scotland the public’s health would be hugely improved.

Intriguingly, although colorectal cancer, heart disease and diabetes share risk factors (especially high fat, low fibre diet) we found that Pakistani people in Scotland had much lower risks than the white Scottish Group. This makes us re-think what we know about the causes of this cancer. In our scientific paper we put forward the idea that Pakistani people may be protected by their comparatively low consumption of processed meats (fresh meat is commonly eaten).

Might the high risk of CHD in Pakistani populations in Scotland be a result of heavier tobacco use? The evidence shows that while the smoking prevalence in Pakistani men is about the same as in white men, the prevalence in Pakistani women is very low. Smoking in white Scottish woman, even in pregnancy, is about 25% but it is close to nil in pregnant Pakistani women. This raises interesting questions about the cultural and environmental circumstances that maintain high or low use of tobacco in populations. These observations raise public health challenges of a high order — how can we maintain the cultures that lead to low tobacco use in some ethnic groups while altering the cultures that lead to high tobacco use in others?

The intermingling of migrants and settled populations creates new societies that provide innumerable opportunities for learning and advancement. While my examples are from the health arena, the same is true for other fields: education, entrepreneurship, social capital, crime, and child rearing to name a few. This historical perspective on human migration, evolution and advancement can benefit our health, as well as providing a foundation to contextualize the challenges and changes we face.

Heading image: People migrating to Italy on a boat in the Mediterranean Sea by Vito Manzari from Martina Franca (TA), Italy (Immigrati Lampedusa). CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Immigration and emigration: taking the long-term perspective for our better health appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPatterns in physicsTest your knowledge of neuroanatomical terminologyWhat do rumors, diseases, and memes have in common?

Related StoriesPatterns in physicsTest your knowledge of neuroanatomical terminologyWhat do rumors, diseases, and memes have in common?

Bioethics and the hidden curriculum

The inherent significance of bioethics and social science in medicine is now widely accepted… at least on the surface. Despite an assortment of practical problems—limited curricular time compounded by increased concern for “whitespace”—few today deny outright that ethical practice and humanistic patient engagement are important and need to be taught. But public acknowledgements all too often are undercut by a different reality, a form of hidden curriculum that overpowers institutional rhetoric and the best-laid syllabi. Most medical schools now make an effort to acknowledge that ethics and humanities training is part of their mission and we have seen growing inclusion of bioethics and medical humanities in medical curricula. However, more curricular time, in and of itself, is not enough.

Even with increases in contact hours, the value of medical ethics and humanities can be undercut by problems of frequency and duration. Many schools have dedicated significant time to bioethics when measured in contact hours, but in the form of intensive seminars that are effectively quarantined from the rest of the curriculum. While this is a challenge for modular curricula in general, it can be harder for students to integrate ethics and humanities content into biomedical contexts. Irrespective of the number of contact hours, placing bioethics in a curricular ghetto risks sending a message that it is simply is a hoop to jump through, something to eventually be set aside as one returns to the real curriculum.

While partitioning ethics and humanities content presents problems, the integration of ethics into systems-based curricula poses different challenges. While, case-based formats make integration easier, they limit the extent to which one can teach core concepts themselves. For organ systems curricula, where ethics lectures often are “sprinkled in,” the linkages with the biomedical components of the course are underspecified or inherently weak. Medical ethics and humanities are diffused in actual practice such that attempts at thematic alignment with organ systems curricula often are noticeably artificial. In turn, there is an unintentional but palpable message that ethics is an interruption to medical learning. Anyone who has delivered an ethics lecture, sandwiched between two pathology lectures in a GI course knows this feeling only too well.

Finally, there is a misalignment of goals and assessment in bioethics that remains a significant challenge. Certainly, one goal of ethics and humanities education in medical curricula is to provide concrete information about legal directives and consensus opinions. Most of us, however, want to go beyond a purely instrumental approach to ethics and promote the ability to empathize with patients and think critically about ethical and humanistic features of patient care. These issues are much more important than an instrumental approach. While there are a variety of ways to assess these higher-order capacities within a course, board exams loom large in the medical student consciousness (and rightfully so). On a multiple choice exam, being reflexive about one’s ethical framework and exploring the large supply of contingencies surrounding a particular case is a recipe for disaster. In turn, I often find myself encouraging students to pursue interesting and creative lines of thought or to challenge consensus statements from professional bodies, only to end the discussion by warning that they should abandon all such efforts on board exams. Most would agree that ethics is a dialogical activity, yet the examinations with the highest stakes send hidden messages that it is formulaic and instrumental. When “assessment drives learning,” it is difficult for students to set aside concerns about gateway exams and engage the genuine complexity of ethics.

Doctor writing. © webphotographeer via iStock.

Doctor writing. © webphotographeer via iStock. While these challenges are curricular, pedagogical, and even cultural, I think there are practical ways that medical schools, and even individual instructors, can destabilize the messages of this hidden curriculum. First, with regard to assessment, we can teach both complex and instrumental ethical methodologies. While this may appear a rather dismal prospect, it can be made respectable by explicating the conditions under which each way of thinking is useful (e.g. the former in real life, the latter on exams). Students then learn not only to turn on and off particular test taking strategies, but this also bolsters their ability to be critical and reflexive—in this case about a instrumental processes of ethical decision-making that are problematic, but nonetheless widespread, even in practice.

Second, we need to move beyond simply including more bioethics education and toward addressing its rhythms within our curricula. I have been fortunate enough to recently join a new medical school unencumbered by a historical (read: petrified) curriculum. In addition to an institutional culture genuinely amenable to ethics and humanities, our curriculum utilizes longitudinal courses that run in parallel to the biomedical systems courses. Instructors therefore have the ability to build the sort of conceptual complexity that truly attends ethics and students have the spaced practice that is key to their development. This structure therefore avoids the problems both of quarantining and random inclusion.

Finally, bioethics curricula need to develop less emphasis on information and a greater utilization of “threshold concepts”. No medical curriculum affords enough time to exhaust the terrain of bioethics and medical humanities. Certainly we need to accept the reality that we typically are not training ethics and humanities scholars, but, at a minimum, physicians with those competencies and even more ideal, physicians who embody those values. However, where the idea of delivering ethics at an appropriate level for physicians often serves as a call for simplicity, I believe it supplies a warrant for focus on our most complex concepts, which also are the most generative and useful. When training practitioners, epistemological concepts—for example, integrative and differentiating ways of thinking—often are eschewed in favor of simpler kinds of information that promote instrumental applications to situations, and a limited ability engage the messy nuances of real world situations. Richer, more complex threshold concepts—like the sociological imagination (the ability to see the interweaving of macro and micro level phenomena)—are broadly relevant and transposable to any number of complex situations.

In the contemporary landscape, few deny outright the significance of ethics and humanities in medicine. But the explicit messaging about their importance remains outmatched by implicit messages hidden in curricula. Having just returned from the annual meeting of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, I cannot help but feel that we are spending too much time fighting old battles by repetitiously announcing the relevance of bioethics and too little time confronting the more insidious, hidden messages nestled deeper in the trenches of curriculum and pedagogy. This is a critical challenge.

The post Bioethics and the hidden curriculum appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychologyA new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returnsWhy be rational (or payday in Wonderland)?

Related StoriesEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychologyA new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returnsWhy be rational (or payday in Wonderland)?

November 13, 2014

Why be rational (or payday in Wonderland)?

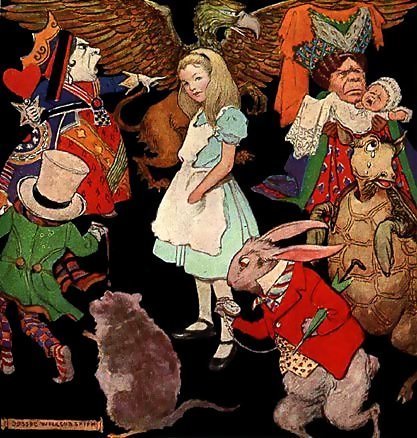

Please find below a pastiche of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland that illustrates what it means to choose rationally:

‘Sit down, dear’, said the White Queen.

Alice perched delicately on the edge of a chair fashioned from oyster-shells.

‘Coffee, or tea, or chocolate?’, enquired the Queen.

‘I’ll have chocolate, please.’

The Queen turned to the Unicorn, standing, as ever, behind the throne: ‘Trot along to the kitchen and bring us a pot of chocolate if you would. There’s a good Uni.’

Off he trots. And before you can say ‘jabberwocky’ is back: ‘I’m sorry, Your Majesty, and Miss Alice, but we’ve run out of coffee.’

‘But I said chocolate, not coffee’, said a puzzled Alice.

The Unicorn was unmoved: ‘I am well aware of that, Miss. As well as a horn I have two good ears, and I’m not deaf’.

Alice thought again: ‘In that case’, she said, ‘I’ll have tea, if I may?’

‘Of course you may,’ replied the Queen. ‘But if you do, you’ll be violating a funny little thing that in the so-called Real World is known as the contraction axiom; in Wonderland we never bother about such annoyances. In the Real World they claim that they do, but they don’t.’

‘Don’t they?’ asked Alice.

‘No. I’ve heard it said, though I can scarce believe it, that their politicians ordain that a poor girl like you when faced with the choice between starving or taking out a payday loan is better off if she has only the one option, that of starving. No pedantic worries about contraction there (though I suppose your waist would contract, now I come to think of it). But this doesn’t bother me: like their politicians, I am rich, a Queen in fact, as my name suggests’.

Alice in Wonderland, by Jessie Wilcox Smith. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Alice in Wonderland, by Jessie Wilcox Smith. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons ‘On reflection, I will revert to chocolate, please. And do they have any other axes there?’

‘Axioms, child, not axes. And yes, they do. They’re rather keen on what they call their expansion axiom – the opposite, in a sense, of their contraction axiom. What if Uni had returned from the kitchen saying that they also had frumenty – a disgusting concoction, I know – and you had again insisted on tea? Then as well making your teeth go brown you’d have violated that axiom.’

‘I know I’m only a little girl, Your Majesty, but who cares?’

‘Not I, not one whit. But people in the Real World seem to. If they satisfy both of these axiom things they consider their choice to be rational, which is something they seem to value. It means, for example, that if they prefer coffee to tea, and tea to chocolate, then they prefer coffee to chocolate.’

‘Well, I prefer coffee to tea, tea to chocolate, and chocolate to tea. And why shouldn’t I?’

‘Because, poor child, you’ll be even poorer than you are now. You’ll happily pay a groat to that greedy little oyster over there to change from tea to coffee, pay him another groat to change from coffee to chocolate, and pay him yet another groat to change from chocolate to tea. And then where will you be? Back where you started from, but three groats the poorer. That’s why if you’re not going to be rational you should remain in Wonderland, or be a politician.’

This little fable illustrates three points. The first is that rationality is a property of patterns of choice rather than of individual choices. As Hume famously noted in 1738, ‘it is not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger; it is not contrary to reason for me to chuse [sic] my total ruin to prevent the least uneasiness of an Indian’. However, it seems irrational to choose chocolate when the menu comprises coffee, tea, and chocolate; and to choose tea when it comprises just tea and chocolate. It also seems irrational to choose chocolate from a menu that includes tea; and to choose tea from a larger menu. The second point is that making consistent choices (satisfying the two axioms) and having transitive preferences (not cycling, as does Alice) are, essentially, the same thing: each is a characterisation of rationality. And the third point is that people are, on the whole, rational, for natural selection weeds out the irrational: Alice would not lose her three groats just once, but endlessly.

These three points are equally relevant to the trivia of our daily lives (coffee, tea, or chocolate) and to major questions of government policy (for example, the regulation of the loan market).

Featured image credit: ‘Drink me Alice’, by John Tenniel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Why be rational (or payday in Wonderland)? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is African American religion?How much do you know about Alexander the Great?Why do you love the VSIs?

Related StoriesWhat is African American religion?How much do you know about Alexander the Great?Why do you love the VSIs?

The Civil War in five senses

Historians are tasked with recreating days past, setting vivid scenes that bring the past to the present. Mark M. Smith, author of The Smell of Battle, the Taste of Siege: A Sensory History of the Civil War, engages all five senses to recall the roar of canon fire at Vicksburg, the stench of rotting corpses in Gettysburg, and many more of the sights and sounds of battle. In doing so, Smith creates a multi-dimensional vision of the Civil War and captures the human experience during wartime. Here, Smith speaks to how our senses work to inform our understanding of history and why the Civil War was a singular sensory event.

Sensory overload in the Civil War

Using sensory history to understand the past

How the Civil War transformed taste

Headline image credit: The Siege of Vicksburg. Litograph by Kurz and Allison, 1888. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

The post The Civil War in five senses appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaking leadersJawaharlal Nehru, moral intellectualSeven common misconceptions about the Hebrew Bible

Related StoriesMaking leadersJawaharlal Nehru, moral intellectualSeven common misconceptions about the Hebrew Bible

Composer Michael Finnissy in 8 questions

We asked our composers a series of questions based around their musical likes and dislikes, influences, challenges, and various other things on the theme of music and their careers. Each month we will bring you answers from an OUP composer, giving you an insight into their music and personalities.

Here’s what OUP composer Michael Finnissy had to say:

Which composer were you most influenced by?

Charles Ives, when I was twelve or thirteen. I think Anthony Hopkins introduced the Concord Sonata in his BBC Radio ‘Talking about Music’ series, from which I learned so much about aesthetics and the craft of composing.

Can you describe the first piece of music you ever wrote?

The first piece I ever wrote was called ‘The Chinese Bridge’, I was just over 4 years old, and had been told the ‘story’ of the willow-pattern pottery. The piece was one line long, clumsily pentatonic, and all in the middle octave of the piano. I thought my mother’s sister had kept the music-book it was written in, but in several moves of house it got lost.

Michael Finnissy. Photo credit: Ben Britton.

Michael Finnissy. Photo credit: Ben Britton. Have the challenges you face as a composer changed over the course of your career?

The main challenges for a composer, to maintain integrity and authenticity, take quite a battering from the UK ‘music business’ — pressures to conform, to be intelligible, to be ‘amusing’. Teaching keeps me up to speed, but I still suffer terrible uncertainties and depressions. Being stubborn, intensely obsessive and passionate probably helps. None of this ever seems to get any better.

What is the last piece of music you listened to?

The last thing I listened to properly was some Chinese traditional music, wonderfully played on a recent visit to Taipei. But I am half-way through watching a DVD of a slightly irritating production of Richard Strauss’s ‘Die Liebe der Danae’, having to close my eyes to focus on the sound.

What might you have been if you weren’t a composer?

You don’t choose to be a composer, it’s what you are put here to do. My parents wanted me to teach English. I had to fight.

Is there an instrument you wish you had learnt to play and do you have a favourite work for that instrument?

I only played the piano ‘by accident’, and if I had chosen the viola (the sound of which I love), could I have endured the stupid jokes and insults? I would have liked to sing well, but was told I sounded like a .

What would be your desert island playlist? (three pieces)

Busoni’s Doktor Faust, Stravinsky’s Les Noces, and Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage. All singing, all dancing. I would also hope to have the scores of a couple of late Beethoven quartets, Matthijs Vermeulen’s 2nd Symphony, and — right now — some of the Voices and Piano pieces by Peter Ablinger, which I need to investigate further!

How has your music changed throughout your career?

Oddly enough I never intended to write the same piece over and over again: so of course I think my music, and my life, has changed, and I’ve been lucky enough to get older and research a bit more deeply. But in other respects it is said that ‘leopards don’t change their spots’. I am thinking about the NEXT piece, not my ‘career’! Working in a university has made me aware that there are many people better qualified than I am, and musicians who – if they are interested – can better tell you HOW my music (and anyone else’s) has changed.

Headline image credit: Music Piano Keys by geralt. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Composer Michael Finnissy in 8 questions appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAdele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler on the Hebrew BibleSeven common misconceptions about the Hebrew BibleEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

Related StoriesAdele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler on the Hebrew BibleSeven common misconceptions about the Hebrew BibleEvidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

Evidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology

The field of pediatric psychology has been changing rapidly over the last decade with both researchers and practitioners working to keep up with the latest innovations. To address the latest evidence-based interventions and methodological improvements, the editors of the Journal of Pediatric Psychology and Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology decided to join efforts and publish special issues on evidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology. We sat down with guest editors Tonya M. Palermo, Ph.D. (Journal of Pediatric Psychology) and Bryan D. Carter, Ph.D. (Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology) to discuss the latest issue in the field and what was learned in this collaborative review of the field.

Why did you want to do a tandem issue on evidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology?

Tonya Palermo: I was interested in putting together the special issue for Journal of Pediatric Psychology (JPP) because the last comprehensive reviews of evidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology were published in JPP in 1999. In the past 15 years, so much movement has occurred in the field around development and evaluation of interventions that an updated review of the state of the science was long overdue. My goal in conducting the special issue was also to increase the quality of the reviews by using rigorous systematic review methods. In this way, the special issue best represents the state of the science of interventions that comprise the professional practice of pediatric psychology.

Bryan Carter: I wanted to see how this special issue topic could be used to provide examples of “real world” applications of evidence-based interventions. The editors of JPP and Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology (CPPP) had the wisdom to recognize that linking the topics in both journals could provide the perfect opportunity to showcase practitioner-level applications of those representative interventions chosen for the JPP special issue. My goal was to make the end product as useful as possible for the reader to have access to those proven efficacious psychological interventions representing the best science our profession has to offer, while also being able to learn from the applied clinical experiences of practitioners as to the challenges and barriers to employing evidence-based interventions with unique clinical conditions, patients, and populations.

Were there any major lessons learned that would inform future methodological improvements in research on pediatric psychological interventions?

Tonya Palermo: One of the lessons learned from the JPP special issue is that the quality of the intervention research (randomized controlled trials) needs to be improved upon in virtually all areas of pediatric psychology interventions. We need to design trials that test a priori hypotheses about intervention effects using well-validated outcomes. We need to use appropriate control conditions and rigorous methods of data collection including blinding where possible to mitigate against bias. We also need to follow established standards for trial reporting so that readers can have a full and transparent reporting of our results. By improving the quality of our intervention research we will enhance the ability to draw firm conclusions about pediatric psychology interventions and to impact decisions made about delivery of these interventions in health systems.

Bryan Carter: Pediatric psychology has grown over the decades to encompass an increasingly bigger tent. Pediatric psychologists can learn important lessons concerning intervention implementation from reports of the application of science-based empirical interventions in day-to-day clinical work. The rich detail that can be addressed from these formats will hopefully lead to replication and stimulate larger scale intervention studies that impact the practice of pediatric psychology, as well as the policies of organizations and governments responsible for optimizing health care for children and families.

Young woman lying on therapist’s couch. © 4774344sean via iStock.

Young woman lying on therapist’s couch. © 4774344sean via iStock. What do you believe are the overall take-home findings from the tandem special issues?

Tonya Palermo: From my perspective I see the glass as half full. In many areas of pediatric psychology within cross-cutting areas such as health promotion, adherence, and pain interventions, the evidence base has grown tremendously. There is evidence for psychological interventions to have robust effects for behavior change and symptom reduction in pediatric populations. This type of evidence is needed to establish pediatric psychology interventions as firstline treatments for children and families in hospital and community settings. Researchers can build from the evidence base to address specific knowledge gaps and to design stronger research to better understand which children and families receive the most benefit from which specific interventions. Clinicians can use these systematic reviews as a starting point for guiding practice in the absence of current consensus statements and clinical practice guidelines in pediatric psychology.

Bryan Carter: Despite the breadth of topics covered in the tandem issues, they represent only a sampling of the wide range of areas in which pediatric psychological interventions have been developed. In most pediatric medical conditions (e.g. late neurocognitive effects of pediatric cancer treatment, acute and chronic pain) and clinical settings (e.g. integrated primary care, in-hospital, school-based, home intervention), pediatric psychologists have implemented interventions. Many of the evidence-based interventions that have proven effective for certain pediatric conditions have relevance to the study of other pediatric health problems, and other areas of investigation, e.g. adherence studies, stress management, family interventions. Researchers and clinicians can draw from the representative systematic analyses and clinical “real world” application reports represented in the tandem JPP and CPPP special issues to inform their own investigations and practice.

Are there implications and recommendations for training psychology students in evidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology?

Tonya Palermo: Core competencies for training in pediatric psychology have been recently published in JPP. The tandem special issues highlight the areas of evidence-based practice that are particularly relevant for pediatric psychology training both in terms of clinical applications as well as scientific training. The next generation of pediatric psychologists can effect major changes in the delivery of pediatric psychology services by building on the evidence base through the conduct of rigorous clinical trials that address cost effectiveness and cost offset of these interventions; advocating for evidence-based interventions for their patients; and teaching other health care professionals, hospital systems, and insurers about the value of evidence-based pediatric psychological interventions.

Bryan Carter: Pediatric psychologists have many challenges ahead in solidifying their role in a rapidly evolving health care system that places a high premium on efficiency, expediency, and technology. For pediatric psychological services to be truly integrated into developing health care models, we must continue to demonstrate how we contribute to better health and quality of life outcomes. The tandem special issue of CPPP demonstrates areas of evidence-based practice critical to students learning to intervene with these populations. It is our hope that this will serve to encourage others to submit their data-based studies, commentaries, reviews, clinical case reports/series, outcome studies, examples of program development, etc., as these serve a valuable role in informing the process of designing theory-based clinical trials that are responsive to the realities of everyday clinical settings and diverse populations.

The post Evidence-based interventions in pediatric psychology appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat do rumors, diseases, and memes have in common?Test your knowledge of neuroanatomical terminologyA new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returns

Related StoriesWhat do rumors, diseases, and memes have in common?Test your knowledge of neuroanatomical terminologyA new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returns

November 12, 2014

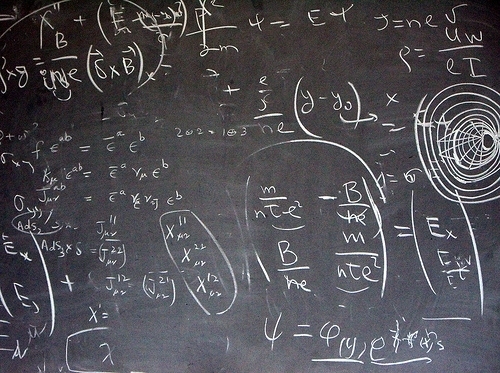

Patterns in physics

The aim of physics is to understand the world we live in. Given its myriad of objects and phenomena, understanding means to see connections and relations between what may seem unrelated and very different. Thus, a falling apple and the Moon in its orbit around the Earth. In this way, many things “fall into place” in terms of a few basic ideas, principles (laws of physics) and patterns.

As with many an intellectual activity, recognizing patterns and analogies, and metaphorical thinking are essential also in physics. James Clerk Maxwell, one of the greatest physicists, put it thus: “In a pun, two truths lie hid under one expression. In an analogy, one truth is discovered under two expressions.”

Indeed, physics employs many metaphors, from a pendulum’s swing and a coin’s two-sidedness, examples already familiar in everyday language, to some new to itself. Even the familiar ones acquire additional richness through the many physical systems to which they are applied. In this, physics uses the language of mathematics, itself a study of patterns, but with a rigor and logic not present in everyday languages and a universality that stretches across lands and peoples.

Rigor is essential because analogies can also mislead, be false or fruitless. In physics, there is an essential tension between the analogies and patterns we draw, which we must, and subjecting them to rigorous tests. The rigor of mathematics is invaluable but, more importantly, we must look to Nature as the final arbiter of truth. Our conclusions need to fit observation and experiment. Physics is ultimately an experimental subject.

Physics is not just mathematics, leave alone as some would have it, that the natural world itself is nothing but mathematics. Indeed, five centuries of physics are replete with instances of the same mathematics describing a variety of different physical phenomena. Electromagnetic and sound waves share much in common but are not the same thing, indeed are fundamentally different in many respects. Nor are quantum wave solutions of the Schroedinger equation the same even if both involve the same Laplacian operator.

Advanced Theoretical Physics by Marvin (PA). CC-BY-NC-2.0 via mscolly Flickr.

Advanced Theoretical Physics by Marvin (PA). CC-BY-NC-2.0 via mscolly Flickr. Along with seeing connections between seemingly different phenomena, physics sees the same thing from different points of view. Already true in classical physics, quantum physics made it even more so. For Newton, or in the later Lagrangian and Hamiltonian formulations that physicists use, positions and velocities (or momenta) of the particles involved are given at some initial instant and the aim of physics is to describe the state at a later instant. But, with quantum physics (the uncertainty principle) forbidding simultaneous specification of position and momentum, the very meaning of the state of a physical system had to change. A choice has to be made to describe the state either in terms of positions or momenta.

Physicists use the word “representation” to describe these alternatives that are like languages in everyday parlance. Just as with languages, where one needs some language (with all equivalent) not only to communicate with others but even in one’s own thinking, so also in physics. One can use the “position representation” or the “momentum representation” (or even some other), each capable of giving a complete description of the physical system. The underlying reality itself, and most physicists believe that there is one, lies in none of these representations, indeed residing in a complex space in the mathematical sense of complex versus real numbers. The state of a system in quantum physics is in such a complex “wave function”, which can be thought of either in position or momentum space.

Either way, the wave function is not directly accessible to us. We have no wave function meters. Since, by definition, anything that is observed by our experimental apparatus and readings on real dials, is real, these outcomes access the underlying reality in what we call the “classical limit”. In particular, the step into real quantities involves a squared modulus of the complex wave functions, many of the phases of these complex functions getting averaged (blurred) out. Many so-called mysteries of quantum physics can be laid at this door. It is as if a literary text in its ur-language is inaccessible, available to us only in one or another translation.

In Orbit by Dave Campbell. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via limowreck666 Flickr.

In Orbit by Dave Campbell. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via limowreck666 Flickr. What we understand by a particle such as an electron, defined as a certain lump of mass, charge, and spin angular momentum and recognized as such by our electron detectors is not how it is for the underlying reality. Our best current understanding in terms of quantum field theory is that there is a complex electron field (as there is for a proton or any other entity), a unit of its excitation realized as an electron in the detector. The field itself exists over all space and time, these being “mere” markers or parameters for describing the field function and not locations where the electron is at an instant as had been understood ever since Newton.

Along with the electron, nearly all the elementary particles that make up our Universe manifest as particles in the classical limit. Only two, electrically neutral, zero mass bosons (a term used for particles with integer values of spin angular momentum in terms of the fundamental quantum called Planck’s constant) that describe electromagnetism and gravitation are realized as classical electric and magnetic or gravitational fields. The very words particle and wave, as with position and momentum, are meaningful only in the classical limit. The underlying reality itself is indifferent to them even though, as with languages, we have to grasp it in terms of one or the other representation and in this classical limit.

The history of physics may be seen as progressively separating what are incidental markers or parameters used for keeping track through various representations from what is essential to the physics itself. Some of this is immediate; others require more sophisticated understanding that may seem at odds with (classical) common sense and experience. As long as that is kept clearly in mind, many mysteries and paradoxes are dispelled, seen as artifacts of our pushing our models and language too far and “identifying” them with the underlying reality, one in principle out of reach. We hope our models and pictures get progressively better, approaching that underlying reality as an asymptote, but they will never become one with it.

Headline Image credit: Milky Way Rising over Hilo by Bill Shupp. CC-BY-2.0 via shupp Flickr

The post Patterns in physics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTest your knowledge of neuroanatomical terminologyAre we alone in the Universe?Celebrating 60 years of CERN

Related StoriesTest your knowledge of neuroanatomical terminologyAre we alone in the Universe?Celebrating 60 years of CERN

Test your knowledge of neuroanatomical terminology

Neuroanatomical Terminology by Larry Swanson supplies the first global, historically documented, hierarchically organized human nervous system parts list. This defined vocabulary accurately and systematically describes every human nervous system structural feature that can be observed with current imaging methods, and provides a framework for describing accurately the nervous system in all animals including invertebrates and vertebrates alike. Just how well do you know your neuroanatomical terminology? Test your knowledge!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Heading image: An anatomical illustration from Sobotta’s Human Anatomy 1908 by Dr. Johannes Sobotta. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Test your knowledge of neuroanatomical terminology appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlace of the Year 2014 nominee spotlight: Brazil [Infographic]Meeting and mating with our ancient cousinsThe evolution of life

Related StoriesPlace of the Year 2014 nominee spotlight: Brazil [Infographic]Meeting and mating with our ancient cousinsThe evolution of life

A new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returns

For investors and asset managers, expected stock returns are the rates of return over a period of time in the future that they require to earn in exchange for holding the stocks today. Expected returns are a central input in their decision process of allocating wealth across stocks, and are essential in determining their welfare. For corporate managers, expected returns on the stocks of their companies, or the costs of equity, are the rates of returns over a period of time in the future that their shareholders require to earn in exchange for injecting equity to their companies today. The costs of equity play a key role in the decision process of corporate managers when deciding which investment projects to take and how to finance the investment. Despite the paramount importance, no consensus exists on how to best estimate expected stock returns. In fact, one of the most important challenges in academic finance is to explain anomalies, empirical patterns of expected stock returns that seem to evade traditional theories.

A manager should optimally keep investing until the investment costs today equal the value of future investment benefits discounted to today’s dollar terms, using her firm’s expected stock return as the discount rate. This economic logic implies that all else equal, stocks of firms with high investment should have lower discount rates than stocks with low investment. Intuitively, low discount rates lead to high discounted values of new projects and high investment. In addition, stocks with high profitability (investment benefits) relative to low investment should have higher discount rates than stocks with low profitability. Intuitively, the high discount rates are necessary to offset the high profitability to induce low discounted values for new projects and low investment.

Forex stock exchanges, by Allan Ajifo. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Forex stock exchanges, by Allan Ajifo. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.To implement this idea, we use a standard technique in academic finance that “explains” a stock’s return with the contemporaneous returns on a number of factors. In a highly influential study, Fama and French (1993) specify three factors: the return spread between the overall stock market and the one-month Treasury bill, the return spread between small market cap and big market cap stocks, and the return spread between stocks with high accounting relative to market value of equity and stocks with low accounting relative to market value of equity. Carhart (1997) forms a four-factor model by augmenting the Fama-French model with the return spread between stocks with high prior six to twelve month returns and stocks with low prior six to twelve month returns.

We propose a new four-factor model, dubbed the q-factor model, which includes the market factor, a size factor, an investment factor, and a profitability factor. The market and size (market cap) factors are basically the same as before. The investment factor is the return spread between stocks with low investment and stocks with high investment. The profitability factor is the return spread between stocks with high profitability and stocks with low profitability. The q-factor model captures most of the anomalies that prove challenging for the Fama-French and Carhart models in the data.

Specifically, during the period from January 1972 to December 2012, the investment factor earns an average return of 0.45% per month, and the profitability factor earns 0.58%. The Fama-French and Carhart models cannot capture our factor returns, but the q-factor model can capture the returns on the Fama-French and Carhart factors. More important, the q-factor model outperforms the Fama-French and Carhart models in “explaining” a comprehensive set of 35 significant anomalies in the US stock returns. The average magnitude of the unexplained returns is on average 0.20% per month in the q-factor model, which is lower than 0.55% in the Fama-French model and 0.33% in the Carhart model. The number of unexplained anomalies is 5 in the q-factor model, which is lower than 27 in the Fama-French model and 19 in the Carhart model. The q-factor model’s performance, combined with its economic intuition, suggests that it can serve as a new benchmark for estimating expected stock returns.

The post A new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returns appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaking leadersInnovation and safety in high-risk organizationsI miss Intrade

Related StoriesMaking leadersInnovation and safety in high-risk organizationsI miss Intrade

November 11, 2014

Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler on the Hebrew Bible

Winner of the 2004 National Jewish Book Award for Scholarship, The Jewish Study Bible is a landmark, one-volume resource tailored especially for the needs of students of the Hebrew Bible. We sat down with co-editors Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler to talk about the revisions in the Second Edition of The Jewish Study Bible, and the Biblical Studies field as a whole.

What led to the decision to revise the Jewish Study Bible?

It has been ten years since the first edition of the Jewish Study Bible (JSB) was published. During that time our knowledge of the Bible and of ancient Israel has advanced tremendously. At the same time, a new generation of scholars has entered the field, with fresh approaches to the study of the Bible. We wanted to build on our very successful first edition by introducing our readers to new knowledge and new approaches.

How extensive are the revisions?

They are very extensive. Many books of the Bible have entirely new annotations/commentaries, by new authors, and all have been revised to reflect new scholarship. The essays have been revised, some by new authors. In addition, many new essays on a wide variety of topics have been added, ranging from topics such as the calendar to the place of the Bible in American Jewish culture.

What has changed in research in Biblical Studies since the publication of the first edition?

We now have a much broader and sophisticated appreciation of how the Bible came to be the Bible, and how its various parts were re-shaped and interpreted in ancient times. Much current emphasis is on the Persian and Hellenistic periods, when the biblical canon and its earliest interpretation were developing. The history and archaeology of these periods have given us a firmer grasp on how Jewish identity was being formed. This, in turn, helps us to better understand the development of the biblical text and its message for the audiences of those times. We recognize that there were multiple Jewish communities with differing views on certain matters, and we are sensitive to the many voices reflected (or suppressed) within the biblical books. Finally, even when scholars recognize that biblical books are composite and have a complex editorial history, it is valuable to examine the final form that an editor imposed upon them, and what this final form may mean.

Where do you see Biblical Studies heading in the next 10 years?

We are neither prophets not children of prophets (Amos 7:14). It is likely that further archaeological discoveries will help us better understand certain passages and institutions. Perhaps the debate raging about dating biblical literature will be resolved, and we will be able to better understand biblical books in their historical contexts. Finally, it is important to remember that Jewish participation in mainstream biblical scholarship began only half a century ago, and it is likely that in the coming decade Jewish scholars will find new ways of integrating classical Jewish sources with critical approaches.

What is the most important issue in the Biblical Studies field right now?

It is hard to single out just one important issue. Some of the older questions, like the history and growth of the biblical text, continue to engage scholars and they have proposed new models and new answers. A more recent development is the concern with biblical or ancient Jewish theology, a relatively neglected area until now. The general current interest in religion, religious concepts, and the importance of religious beliefs is shared by biblical scholars and has become a fruitful way to approach the study of the Bible.

Headline image credit: Rachel Preparing Bible Homework by David King. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler on the Hebrew Bible appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSeven common misconceptions about the Hebrew BibleRemembrance DayTop four high profile cases in Intellectual Property law

Related StoriesSeven common misconceptions about the Hebrew BibleRemembrance DayTop four high profile cases in Intellectual Property law

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers