Oxford University Press's Blog, page 735

November 21, 2014

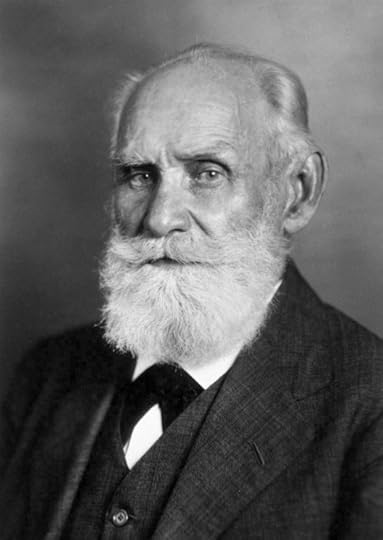

Ivan Pavlov in 22 surprising facts

An iconic figure of 20th century science and culture, Ivan Pavlov is best known as a founding figure of behaviorism who trained dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell and offered a scientific approach to psychology that ignored the “subjective” world of the psyche itself.

While researching Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science, I discovered that these and other elements of the common images of Pavlov are incorrect. The following 22 facts and observations are a small window onto the life of a man whose work, life and values were much more complex and interesting than the iconic figure with whom we are so familiar.

Pavlov didn’t use a bell, and for his real scientific purposes, couldn’t. English-speakers think he did because of a mistranslation of the Russian word for zvonok (buzzer) and because the behaviorists interpreted Pavlov in their own image for people in the U.S. and much of the West. He didn’t use the term and concept “conditioned reflex,” either – rather, “conditional,” and it makes a big difference. For him, the conditional reflex was not just a phenomenon, but a tool for exploring the animal and human psyche – “our consciousness and its torments.” Unlike the behaviorists, Pavlov believed that dogs (like people) had identifiable personalities, emotions, and thoughts that scientific psychology should address. “Essentially, only one thing in life is of real interest to us,” he declared: “our psychical experience.” As a youth, he identified worriedly with Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov – fearing that his devotion to rationality might strip him of human morality and feelings – but also believed that science (especially physiology) might teach humans to be more reasonable and humane. Ivan Pavlov. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Although one would expect that this investigator of reflexive reactions would think otherwise, he believed in free will. Pavlov was from a religious family and trained for the priesthood, but left seminary for science studies at St. Petersburg University. He pondered the relationship of science, religion, morality, and the human quest for certainty throughout his life. Although an atheist, he appreciated religion’s cultural value, protested its repression under the Bolsheviks, and supported financially the local church near his lab at Koltushi. (His wife was deeply religious and their apartment was full of icons.) Pavlov’s beloved mentor in college was fired as a result of student demonstrations against him as a Jew, a political conservative, and (most importantly) a hard grader. This was a great blow to Pavlov and left him on his own as he attempted to make a career. He first got a “real job” at age 41 – as a professor of pharmacology. He didn’t win his Nobel Prize (1904) for research on conditional reflexes, but rather for his studies of digestive physiology. He more than doubled the budget for his labs by bottling the gastric juice he drew from lab dogs and selling it as a remedy for dyspepsia. (A big hit, not just in Russia, but in France and Germany as well. Like Darwin, Pavlov believed that dogs had full-fledged thoughts, emotions and personalities. His lab dogs were given names that captured their personalities and were routinely described in lab notebooks as heroic or cowardly, smart or obtuse, weak or strong, good or bad workers, etc. Pavlov constantly interpreted his own biography and personality in terms of his experiments on dogs (and interpreted dogs according to what he thought he knew about himself and other people). He was famous for his explosive temper –“spontaneous morbid paroxysms,” as he put it. Students and coworkers all had their favorite stories about these vintage explosions. Afterwards, he would make his apologies and get on with his work. Pavlov was an art collector – with a massive collection of Russian realist art in his apartment. His best friends before 1917 were artists. To maintain a “balanced” organism, Pavlov spent three months every year at a dacha (summer home) where he avoided science entirely. A devotee of physical exercise, he spent these months gardening, bicycling, and playing gorodki (a Russian sport in which the players throw heavy wooden bats at formations of other heavy bats, trying to knock them down in as few throws as possible; Pavlov was a champion player even in his old age). He seriously contemplated leaving Russia after the Bolshevik seizure of power in 1917, but finally decided to stay. His Western colleagues helped him financially during the hungry years of civil war (1918 – 1921), but did not offer to support him as a scientist in the West: they thought that, at age 68, he was washed up – but the research on conditional reflexes that would make him an international icon continued full blast for another two decades. He corresponded with Communist leaders Nikolai Bukharin and Vyacheslav Molotov and was one of very few public critics of the Bolsheviks’ political repression, persecution of religion, and terror in the 1930s. He also praised the state for its great support of science and highly respected some of his Communist coworkers, who succeeded in changing his opinion about some important scientific issues. Publically always very confident, privately he suffered constantly from what he called his “Beast of Doubt” – his fear that the psyche would never yield its secrets to his research. Pavlov’s closest scientific collaborator for the last 20+ years of his life, Maria Petrova, was also his lover. During a trip to the U. S. in 1923 he was mugged and robbed of all his money in Grand Central Station, and wanted to go home “where it is safe,” but was convinced to stay and had a great visit. When the Communist state sent a political militant to purge his lab of political undesirables, Pavlov literally kicked him down the stairs and out of the building. When he died, Pavlov was working on two surprising manuscripts that he never completed: one on the relationship of science, Christianity, Communism, and the human search for morality and certainty; the other making an important change in his doctrine of conditional reflexes. According to Pavlov, the most terrible, frightening thing in life was uncertainty, unforeseen accidents (sluchainosti), against which people could turn to religion or – his choice – science.

Ivan Pavlov. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Although one would expect that this investigator of reflexive reactions would think otherwise, he believed in free will. Pavlov was from a religious family and trained for the priesthood, but left seminary for science studies at St. Petersburg University. He pondered the relationship of science, religion, morality, and the human quest for certainty throughout his life. Although an atheist, he appreciated religion’s cultural value, protested its repression under the Bolsheviks, and supported financially the local church near his lab at Koltushi. (His wife was deeply religious and their apartment was full of icons.) Pavlov’s beloved mentor in college was fired as a result of student demonstrations against him as a Jew, a political conservative, and (most importantly) a hard grader. This was a great blow to Pavlov and left him on his own as he attempted to make a career. He first got a “real job” at age 41 – as a professor of pharmacology. He didn’t win his Nobel Prize (1904) for research on conditional reflexes, but rather for his studies of digestive physiology. He more than doubled the budget for his labs by bottling the gastric juice he drew from lab dogs and selling it as a remedy for dyspepsia. (A big hit, not just in Russia, but in France and Germany as well. Like Darwin, Pavlov believed that dogs had full-fledged thoughts, emotions and personalities. His lab dogs were given names that captured their personalities and were routinely described in lab notebooks as heroic or cowardly, smart or obtuse, weak or strong, good or bad workers, etc. Pavlov constantly interpreted his own biography and personality in terms of his experiments on dogs (and interpreted dogs according to what he thought he knew about himself and other people). He was famous for his explosive temper –“spontaneous morbid paroxysms,” as he put it. Students and coworkers all had their favorite stories about these vintage explosions. Afterwards, he would make his apologies and get on with his work. Pavlov was an art collector – with a massive collection of Russian realist art in his apartment. His best friends before 1917 were artists. To maintain a “balanced” organism, Pavlov spent three months every year at a dacha (summer home) where he avoided science entirely. A devotee of physical exercise, he spent these months gardening, bicycling, and playing gorodki (a Russian sport in which the players throw heavy wooden bats at formations of other heavy bats, trying to knock them down in as few throws as possible; Pavlov was a champion player even in his old age). He seriously contemplated leaving Russia after the Bolshevik seizure of power in 1917, but finally decided to stay. His Western colleagues helped him financially during the hungry years of civil war (1918 – 1921), but did not offer to support him as a scientist in the West: they thought that, at age 68, he was washed up – but the research on conditional reflexes that would make him an international icon continued full blast for another two decades. He corresponded with Communist leaders Nikolai Bukharin and Vyacheslav Molotov and was one of very few public critics of the Bolsheviks’ political repression, persecution of religion, and terror in the 1930s. He also praised the state for its great support of science and highly respected some of his Communist coworkers, who succeeded in changing his opinion about some important scientific issues. Publically always very confident, privately he suffered constantly from what he called his “Beast of Doubt” – his fear that the psyche would never yield its secrets to his research. Pavlov’s closest scientific collaborator for the last 20+ years of his life, Maria Petrova, was also his lover. During a trip to the U. S. in 1923 he was mugged and robbed of all his money in Grand Central Station, and wanted to go home “where it is safe,” but was convinced to stay and had a great visit. When the Communist state sent a political militant to purge his lab of political undesirables, Pavlov literally kicked him down the stairs and out of the building. When he died, Pavlov was working on two surprising manuscripts that he never completed: one on the relationship of science, Christianity, Communism, and the human search for morality and certainty; the other making an important change in his doctrine of conditional reflexes. According to Pavlov, the most terrible, frightening thing in life was uncertainty, unforeseen accidents (sluchainosti), against which people could turn to religion or – his choice – science.

Featured image: Pavlov, center, operates on a dog to create an isolated stomach or implant a permanent fistula. After the dog recovered, experiments began on an intact and relatively normal animal, which was a central feature of Pavlov’s scientific style. Courtesy of Wellcome Institute Library, London. Used with permission.

The post Ivan Pavlov in 22 surprising facts appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUnderstanding placebo effects: how rituals affect the brain and the bodyWorld Philosophy Day reading listViolence, and diverse forms of oppression

Related StoriesUnderstanding placebo effects: how rituals affect the brain and the bodyWorld Philosophy Day reading listViolence, and diverse forms of oppression

Understanding placebo effects: how rituals affect the brain and the body

In a typical prehistoric scene, say in 4000 BC, a wounded warrior is dragged to the shaman tent. The respected shaman takes a look at the wound and assures the warrior that he will be healed with the proper prayers and ritual dances. He then prepares a strong-smelling mixture of herbs and seeds, and as the whole tribe chants rhythmically around the campfire, he carefully applies it to the wound, all the while uttering incomprehensible sentences passed on to him by a venerable line of ancestral shamans.

Now let’s come to more recent times, say in 2010 AD. A wounded soldier is carried to the military hospital. The medical staff completes a physical examination. A CT scan to rule out internal lesions is carried out to the reassuring buzz of the most recent technology, and a respected clinician wearing a spotless white coat reassures the soldier that he will be healed with the proper drugs and physiotherapy.

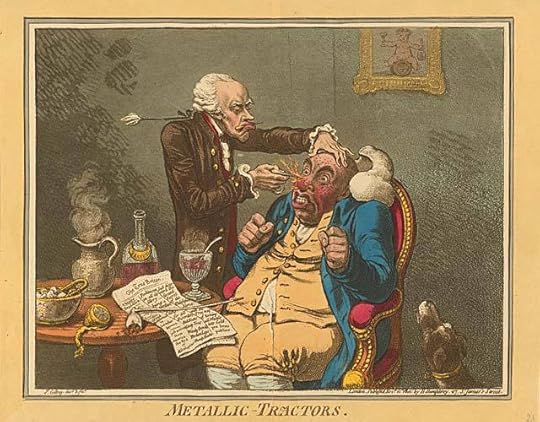

A quack treating a patient with Perkins Patent Tractors by James Gillray, 1801. This remedy was used to illustrate the power of the placebo effect. James Gillray, 1801. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A quack treating a patient with Perkins Patent Tractors by James Gillray, 1801. This remedy was used to illustrate the power of the placebo effect. James Gillray, 1801. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Across the divide of millennia, what do these two pictures have in common? The ritual of the medical and therapeutic act. Shamans of the past and clinicians of today share instinctual knowledge that the context surrounding a therapy is an important part of the therapy itself. Rituals have changed and adapted to the contemporary world, but they are still here. In spite of the huge time span across human history, contexts help both ancient and modern patients to develop trust and expectation that they will eventually regain their health.

Placebo effects work in this way too. Giving a placebo consists of essentially delivering a context without the substance. It is a wrapping devoid of content. Yet, the empty box itself acts subtly on the patient’s mind, just as an active drug would do, activating or silencing synapses, altering neurotransmitter content in specific brain areas, and modifying brain activity in ways that are today amenable to scientific inquiry. Placebos are not only the archetypal sugar pills but can be anything with the power to impact on the patient’s expectations. Placebos are made of words, symbols, rituals, meanings. What is important is not really the tool used, but the changes it triggers in neural activity, and how these changes ultimately affect psychological and bodily functions.

Within this framework, today we are witnessing an epochal transition in the medical paradigm, whereby general concepts, such as suggestibility and power of mind, can now be described in terms of a true biology of placebo effects and doctor-patient interaction. Thanks to modern scientific tools, important questions have been addressed and partially answered, such as psychological and emotional influences on symptoms, diseases, and responses to therapies.

The main concept that is emerging today is that placebos, words, therapeutic rituals and patients’ expectations modulate the same biochemical pathways that are affected by the drugs used in routine medical practice. As a matter of fact, this statement should be reversed. It would be more appropriate to say that drugs use the same biochemical pathways of rituals. In fact, rituals were born long before drugs.

Rituals heal but they can also kill. Nocebo effects are the evil twins of placebo effects, the negative consequence of negative rituals and contexts that induce distrust and hopelessness. These can be triggered by a variety of contexts in non-western societies, such as voodoo, and in western society, such as exaggerated health warnings in the media. A social contagion of negative expectations can spread across people very quickly, sometimes inducing worrisome mass phenomena.

Placebo effects are all of these things. The crucial point, and indeed the big revolution, is that today we can study these phenomena, once the domain of psychology, sociology and anthropology, with the tools of the modern biomedical paradigm. These biological tools involve cellular and molecular accuracy, with rituals and contexts interpreted in terms of specific brain regions and biochemical pathways, thus eliminating the old dichotomy between biology and psychology.

Heading image courtesy of Fabrizio Benedetti. Do not use without permission.

The post Understanding placebo effects: how rituals affect the brain and the body appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnxiety in non-human primatesViolence, and diverse forms of oppressionWorld Philosophy Day reading list

Related StoriesAnxiety in non-human primatesViolence, and diverse forms of oppressionWorld Philosophy Day reading list

Should we let them play?

Ched Evans was convicted at Caernarfon Crown Court in April 2012 of raping a 19 year old woman, and sentenced to five years in prison. He was released from prison in October 2014. Shortly after his release Evans protested his innocence and suggested that his worst offence had been cheating on his fiancée. He also looked to restart his career as a professional soccer player in the third tier of the English league with his former club Sheffield United. What has ensued is a huge debate about whether the club should offer Evans a new contract. One side argues that Evans has served his time and should be allowed to continue his career, whereas the other claims that his role as a professional sportsman marks him out as a role model for his local community and the youngsters that support his team. A rape conviction they say is not compatible with the standards that society demands from its sports stars.

The debate in England over Evans is nothing new. In the US the National Football League (NFL) has had a personal conduct policy in place since 1997. This allows the NFL to take action against any player convicted of a domestic abuse offence including suspensions and fines. Similarly in Australian Rules Football (AFL) the governing body introduced its Respect and Responsibility programme in 2005 to educate players about violence against women. The problem in all these cases, indeed a difficulty for most branches of the sporting world, is that the big box office draws are highly paid male athletes operating out of dressing rooms that are hyper masculine and underpinned by an atmosphere of sexual aggression. As the star players are vital to the industry and ensure that box office receipts and television income remain high, the governing authorities of many male team sports have been slow to act decisively in cases where players have been charged or convicted of rape or domestic abuse. Since the start of the new millennium 48 NFL players have been found guilty of domestic abuse. In 88% of the cases the NFL either banned the player for a single game or else took no action. Similarly the AFL has been slow to take action against players. In the last two years players at the St Kilda Saints and North Melbourne clubs were charged with rape, and in both cases the clubs and the AFL stated that the players would remain available for selection and on full salaries prior to their trials.

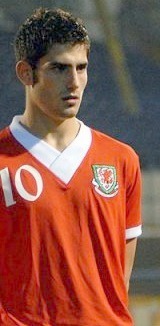

Ched Evans representing Wales in 2009. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Ched Evans representing Wales in 2009. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsIt is clear that the male sporting world has not taken the issue of violence against women seriously. Clubs and managers that demand a strong dressing room, where loyalty to the team is paramount and aggression is part of the game has create a masculine environment where women cannot be respected. In a sporting world where those players are then highly paid, cosseted by their management and agents, women have little function beyond their sexual availability.

The debate in the US around the case of NFL player Ray Rice, who was caught on camera punching his partner unconscious, and that of Ched Evans in England, have piled pressure on clubs and governing bodies to take the issues of sexual and domestic violence by players seriously. In the Ched Evans case the Sheffield born gold medal winning athlete, Jessica Ennis-Hill, stated that if Evans was offered a contract by the club she would ask that her name be removed from the stand that was named after her when she won her Olympic title in 2012. Ennis-Hill stated that ‘those in positions of influence should respect the role’s they play in young people’s lives and set a good example’. And herein lies the whole contradiction around the issue of male sports stars and their attitudes towards sexual and domestic violence.

Modern sport had its roots in Victorian Britain, and would spread around the world in various forms. No matter what type of sport emerged in any given setting across the globe the Victorian obsession that sport had an ethical ethos of fair play and gentlemanly conduct was hard wired into the meaning that society gave sport. As a result contemporary sport is supposed to be played in the right way in accordance with the rules, and athletes are supposed to conduct themselves in a certain way. To be an elite athlete is to be a role model and society expects athletes to display positive attributes on and off the field of play. But why should society expect that athletes, often from the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum and with poor educational attainment, to behave like some form of idealised Victorian gentleman? However, as the sports star is expected to be the model citizen, because the ethics of sport are so deeply embedded in the collective consciousness, their conduct does matter. It matters to many followers of sport, is of interest to the media, and is increasingly becoming important to sponsors as they assess the value of any team or athlete in terms that stretch beyond their success on the field of play.

This is why sports teams and governing bodies will have to start taking firm action against those found guilty of sexual and domestic violence. Guilty players will have to be banned from the game and lose their chance of earning their fortune. Not only will this send a clear message to players that violence against women in unacceptable, it will also shape the thinking of the generation of young boys who see their sporting heroes as role models. If, in the future, they see players who respect women, then male attitudes will improve across society. Those who govern the world of male professional sport have to realise that they administer not simply their games, but they are also responsible for the meaningful creation of men with positive values who can act, in the best ways, as role models.

Featured image credit: “Blades”, by Kopii90 (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Should we let them play? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy be rational (or payday in Wonderland)?Reading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin WallLooking for Tutankhamun

Related StoriesWhy be rational (or payday in Wonderland)?Reading up on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin WallLooking for Tutankhamun

November 20, 2014

Violence, and diverse forms of oppression

The theme of the American Society of Criminology meeting this November is “Criminology at the Intersections of Oppression.” The burden of violence and victimization remains markedly unequal. The prevalence rates, risk factors, and consequences of violence are not equally distributed across society. Rather, there are many groups that carry an unequal burden, including groups disadvantaged due to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual identity, place of residence, and other factors. Even more problematically, there is an abundance of evidence that there are marked disparities in service access and service quality across sociocultural and socioeconomic groups. Unfortunately, even today this still extends to instances of outright bias and maltreatment, as evidenced by ongoing problems with disproportionate minority contact, harsher sentencing, and barriers to services.

However, there is promising news, because advances in both research and practice are readily attainable. Regarding research, there are a number of steps that can be taken to improve our existing state of knowledge. To give just a few examples, we need much more research on hate crimes and bias motivations for violence. Hate crimes remain one of the most understudied forms of violence. We also need many more efforts to adapt violence prevention and intervention programs for diverse groups. The field has still made surprisingly few efforts to assess whether prevention and intervention programs are equally efficacious for different socioeconomic and sociocultural groups. Even after more than 3 decades of program evaluation, only a handful of such efforts exist. Program developers should pay more systematic attention to ensuring that materials that use diverse images and settings. However, it is also important to note that cultural adaptation means more than just superficial changes in name use or images.

Clasped Hands. Photo by Rhoda Baer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Clasped Hands. Photo by Rhoda Baer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Regarding practice, what is needed is more culturally appropriate approaches. In many cases, this means more flexible approaches and avoiding a “one size fits all” approach to services. Most providers, I believe, have good intentions and are trying to avoid biased interactions, but many of them lack the tools for more culturally appropriate services. One specific tool that can help is called the ‘VIGOR’, for Victim Inventory of Goals, Options, and Risks. It is a safety planning and risk management tool for victims of domestic violence. It is ideally suited for people from disadvantaged groups, because, unlike virtually all other existing safety plans, it has places for social and community issues, financial strain, institutional challenges, and other issues that affect people who experience multiple forms of disadvantage. The safety plan does not just focus on physical violence. The VIGOR has been tested with two highly diverse groups of low-income women, who rated it as better than all safety planning they had received.

The VIGOR also offers a model for how other interventions can be expanded and adapted to consider the intersections of oppression with victimization in an effort to be more responsive to all of the needs of those who have sustained violence. With greater attention to these issues, there is the potential to make a real impact and help reduce the burden of violence and victimization for all members of society.

Dr. Hamby attended an Author Meets Critics session at the ASC annual meeting yesterday morning. The session was chaired by Dr. Claire Renzetti, co-editor of the ‘Oxford Series of Interpersonal Violence’.

The post Violence, and diverse forms of oppression appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBeyond #WhyIStayed and #WhyILeftBack to the future with the ASC’s new Division of PolicingFive facts about women’s involvement in organized crime

Related StoriesBeyond #WhyIStayed and #WhyILeftBack to the future with the ASC’s new Division of PolicingFive facts about women’s involvement in organized crime

Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnets

In continuation of our Word of the Year celebrations and the selection of bae for Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year shortlist, I’m presenting my annual butchering of Shakespeare (previous victims include MacBeth and Hamlet). Of the many terms of endearment the Bard used — from lambkin to mouse — babe was not among them. In the 16th century, babe (which Shakespeare used a great deal) referred to a baby (young child) rather than a loved one. So instead, let us see how Shakespeare would address his mistress if he courted her like Pharrell Williams.

Sonnet 130

My bae’s eyes are nothing like the sun,

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks,

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my bae reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound.

I grant I never saw a goddess go:

My bae when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

Sonnet 138

When my bae swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutored youth,

Unlearnèd in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue.

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed:

But wherefore says she not she is unjust?

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

O, love’s best habit is in seeming trust,

And age in love loves not to have years told.

Therefore I lie with her, and she with me,

And in our faults by lies we flattered be.

Sonnet 154

The little Love-god lying once asleep

Laid by his side his heart-inflaming brand,

Whilst many nymphs, that vowed chaste life to keep,

Came tripping by; but in her maiden hand

The fairest votary took up that fire,

Which many legions of true hearts had warmed,

And so the general of hot desire

Was, sleeping, by a virgin hand disarmed.

This brand she quenched in a cool well by,

Which from love’s fire took heat perpetual,

Growing a bath and healthful remedy

For men diseased; but I, my bae’s thrall,

Came there for cure, and this by that I prove:

Love’s fire heats water; water cools not love.

For the original sonnets, plus expert commentary and notes, visit Oxford Scholarly Editions Online: Sonnet 130, Sonnet 138, and Sonnet 154.

The post Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnets appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBae in hip hop lyricsScholarly reflections on ‘bae’Scholarly reflections on ‘slacktivism’

Related StoriesBae in hip hop lyricsScholarly reflections on ‘bae’Scholarly reflections on ‘slacktivism’

Scholarly reflections on ‘bae’

What do you call your loved one? Babe and baby have been used for centuries to discuss small children, and eventually a significant other. With the inclusion of bae on Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year shortlist, we asked a number of scholars for their thoughts on this new word and emerging phenomenon.

* * * * *

“Childish Gambino, the rap persona of entertainment industry generalist Donald Glover, rapped ‘Hanalei Bay with my bae, what can I say?’ on a song he posted on his Soundcloud in late August. Titled ‘Candler Road’ after the thoroughfare in his native Atlanta, he borrows the enunciative and ominous sound that fellow Atlantan Future has employed on his recent roster of hits, and then the melodic and contemplative approach child actor-turned-rapper Drake has perfected. Bae is integral to the line’s internal rhyme and to the insouciance Gambino—who famously left the NBC sitcom Community, pausing his acting, television writing, and stand up comedy career for the love of hip hop and the attendant cool it inspires. Bae, quite simply a devolution of babe (baby), truncates the consonance of the sound, and arguably the sentiment. In hashtag form it imprints social media posts of a relationship status with cool. This newest addition to the shifting slanguage of belonging is an accessory to ‘I won’ (in rapper Future and Kanye West’s parlance from a their hit song of the same name last spring). ‘I just want to take you out and show you off’ is precisely how Future warbled it on the chorus, boastful, like invoking an image of yourself lounging on the island Kauaʻi with ‘bae’ and then declaring yourself speechless.”

— Jalylah Burrell, music critic, deejay, educator, and PhD Candidate, Yale University, Departments of American and African American Studies

* * * * *

“When Jeremy Meeks AKA ‘Prison Bae’ entered my Twitter timeline I did not expect the whirlwind of debate about the significance of the term bae. It was not my first time hearing it; I grew up in the rural South and the slow drag of ‘baaae’ in daily conversations and southern rap did not warrant any further questioning about its significance or meaning. It was a term of endearment and at times all encompassing — anyone could be bae. However, Meeks’ mug shot turned meme demanded a different type of engagement, shifting bae as a term of endearment to something more pleasurable, a recognition of black women’s (physical) desires in the 21st century. Prison Bae memes and the hilarious – if at times nauseating – ‘Cooking for Bae’ Instagram account make me think about how race and women’s desires are signified upon in social media. Instead of black women being restricted to objects of desire for men, bae carves out room for black women to enter the conversation on their own terms. Using bae as a social media meme not only archives black women’s desires but complicates how black women’s pleasures and experiences fit into a constantly shifting social-culturescape that is heavily vested in technology and popular culture. Responses to black women’s use of bae memes suggests an unfamiliarity and unwillingness to engage how bae complicates the ownership and expression of women’s desirability and racial identities in a digital era.”

— Regina N. Bradley, researcher of contemporary African American Popular Culture and founder/host of OutKasted Conversations

* * * * *

“Bae couldn’t be Word of the Year in 2014 because Urban Dictionary has an entry about it from 2008! Slang that old may already be on the way out. Even as a runner-up, though, I’m sure it will ignite a firestorm of slacktivism to reinstate that second /b/.”

— Michael Adams, Indiana University at Bloomington, author of Slayer Slang: A Buffy the Vampire Slayer Lexicon, Slang: The People’s Poetry, editor of From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages

* * * * *

“Bae doesn’t save you much effort, if the word you have in mind is babe. But if you like rhymes, ‘Hey, Bae’ makes for a nifty lexical duo.”

— Naomi S. Baron, Professor of Linguistics and Executive Director of the Center for Teaching, Research & Learning at American University in Washington, DC; author of Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World and the forthcoming Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World

* * * * *

Headline image credit: Beautiful African American couple wearing white shirts laying in grass. © phakimata via iStock.

The post Scholarly reflections on ‘bae’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBae in hip hop lyricsShakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnetsScholarly reflections on ‘slacktivism’

Related StoriesBae in hip hop lyricsShakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnetsScholarly reflections on ‘slacktivism’

Bae in hip hop lyrics

Oxford Dictionaries included bae on its Word of the Year 2014 shortlist, so we invited several experts to comment on the growth of this word in music and language.

Today we’re here to talk about the word bae and the ways in which it’s used in hip hop lyrics. Bae is another way of saying babe or baby (though some say it can also function as an acronym for the phrase “before anyone else”). Here are some examples:

Childish Gambino’s “The Palisades”

In this song, Donald Glover sings “Now why can’t every day be like this…Hang with bae at the beach like this.” Judging from the rest of the lyrics and recent pictures of him with a young woman on the beach, I’d say he’s talking about a girlfriend in this case.

Jay-Z’s “30 Something”

In the chorus of this song, Jay-Z repeats the line, “bae boy, now I’m all grown up”. The overall song reads like an updated version of 1 Corinthians 13:11 (“When I was a child, I talked like a child…When I became a man, I put away childish things”). Here bae seems to be standing in for the word baby, as in baby boy.

Pharrell Williams’ “Come Get It Bae”

The video pretty much makes it crystal clear what the use is here: babe, referring to all the dancing ladies presumably.

Lil Wayne’s “Marvin’s Room (Sorry 4 the Wait)”

Bae shows up right at the end of the track, in the line “She call me ‘baby’ and I call her ‘bae’”. Here it’s clear that Lil Wayne’s bae is an alternate version of her baby.

Fifth Harmony’s “Bo$$”

Ok, I know this is actually pop, but I wanted to include it because it’s so catchy. The overall tone of the lyrics is classic girl power, including the line “I ain’t thirsty for no bae cuz I already know watchu tryna say”. Given the content of the rest of the lyrics, it seems like bae is being substituted for the sense in which babe can refer to boyfriend.

It will be interesting to see what kind of cultural capital bae will accrue in the coming years. Will it thrive, or go the way of flitter-mouse? For more on the many and varied terms of endearment the English language has offered through the ages, check out these unusual terms of endearment in the Oxford English Dictionary.

Headline image credit: Post-Sopa Blackout Party for Wikimedia Foundation staff by Victor Grigas (Victorgrigas). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Bae in hip hop lyrics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on ‘slacktivism’Slacktivism as optical illusionSlacktivism, clicktivism, and “real” social change

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on ‘slacktivism’Slacktivism as optical illusionSlacktivism, clicktivism, and “real” social change

Ten facts about cumbia, Colombia’s principal musical style

In celebration of tonight’s Latin Grammy Awards, I delved into Grove Music Online to learn more about distinct musical styles and traditions of Latin American countries. Colombia’s principal musical style is the cumbia, with its related genres porro and vallenato. In the traditional cumbia proper, couples dance in a circle around seated musicians, with the woman shuffling steps while the man moves in a more zigzag pattern around her. The cumbia usually takes place at night while women hold bundles of candles in colored handkerchiefs in their right hands. Although traditional cumbia is now primarily performed by folklore troupes at Carnivals and other festivals, cumbia has contributed significantly to the development of related musical styles. Below are ten interesting facts about the cumbia.

The cumbia is accompanied by one of two ensembles: the conjunto de cumbia (also known as cumbiamba) and the conjunto de gaitas. The former consists of five instruments, while the latter includes two duct flutes, a llamador and a maraca.

The conjunto de cumbia includes one melody instrument called the caña de millo (‘cane of millet’), locally known as the pito, which is a clarinet made of a tube open at both ends with four finger holes near one end and a reed cut from the tube itself at the other end.

Other instruments include the gaita hembra (‘female flute’) and the gaita macho (‘male flute’). While the gaita hembra is used for the melody, the gaita macho provides heterophony in conjunction with a maraca.

The bullerengue and the danza de negro are two other musical genres of the region, which have African characteristics. The bullerengue is an exhibition dance, filled with hip movement, performed by a single couple. Meanwhile, the danza de negro is a special Carnival dance performed by men who paint themselves blue, strip to the waist, dance in a crouched position with wooden swords, and demand money or rum from passerby.

In the early 20th century, town brass bands began adapting the cumbia to a more cosmopolitan style. Between 1905 and 1910, musicians in numerous towns began these adaptations, which were strongly developed in the town of San Pelayo. Thus, the terms pelayera or papayeraare commonly used in reference to this type of ensemble.

Vallenato, a genre related to traditional cumbia, also originated in the Colombian Atlantic region. Performed by an ensemble consisting of accordion, vocals, caja (a small double-headed drum) and guacharaca (a notched gourd scraper), vallenato is similar to cumbia in accenting beats 2 and 4, but places a stronger emphasis on the crotchet-quaver rhythmic cell.

Another style of music related to cumbia is Música tropical, which developed from the dance band arrangements of Afro-Colombian styles during the 1930s and 40s. Música tropical is similar to the ballroom rumba popular throughout the Americas and Europe, although with it maintains a simpler rhythmic base and more florid melodic style.

Música tropical also offered a response to the international vogue for Cuban Music, which was both Caribbean and uniquely Colombian at the same time. By the late 1950s, música tropical had found its way into the leading social clubs and ballrooms of the country.

Throughout the 1960s, música tropical remained the national Colombian style. Recordings by groups like La Sonora Dinamita, Los Corraleros de Majagual and Los Graduados enjoyed a brief national popularity, but had a greater impact outside the country, spreading a simplified form of cumbia to Mexico, Central America, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Chile, where the style became very important.

During the 1940s and 50s the musical pioneers Lucho Bermúdez and Pacho Galán composed and arranged big-band adaptations of cumbias, among other genres, popularizing the sound which became the new national music of Colombia.

Finally, watch a well-known cumbia — La pollera colera:

Headline image credit: Monumento a la cumbia, 2006. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ten facts about cumbia, Colombia’s principal musical style appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSalamone Rossi as a Jew among JewsGetting to know Anna-Lise Santella, Editor of Grove Music OnlineWorld Philosophy Day reading list

Related StoriesSalamone Rossi as a Jew among JewsGetting to know Anna-Lise Santella, Editor of Grove Music OnlineWorld Philosophy Day reading list

Anxiety in non-human primates

Anxiety disorders adversely affect millions of people and account for substantial morbidity in the United States. Anxiety disrupts an individual’s ability to effectively engage and interact in social and non-social situations. The onset of anxiety disorders may begin at an early age or occur in response to life events. Thus, the effects of anxiety are broad ranging, affecting both family and work dynamics, and may limit an individual’s quality of life.

While there has been a great deal of research focused on anxious behavior and anxiety disorders in the past few decades, there is still much we do not know. In order to better understand anxiety disorders, and to develop novel options for those who are nonresponsive to current treatments, scientists need to investigate the biobehavioral mechanisms that underlie the expression of anxiety related behavior. Research with humans subjects is one strategy used to gain insight on how to effectively treat anxiety disorders. However, there are inherent difficulties with such studies, including complex life histories and differences in access to resources (such as health care), as well as ethical issues. Common physiology between humans and other animals allow for the development of animal models that allow scientists to examine the neurobiological underpinnings of anxiety disorders. The non-human primate (NHP) has been used in the study of anxiety due to the physiological, behavioral and neural commonalities we share.

One type of anxiety assessment in non-human primates relies on direct behavioral observations, either in the animal’s ‘home environment’ or in a situation in which the animal is mildly challenged to induce an anxious state. In these procedures, observers typically look for the presence of behaviors indicative of anxiety, including fear and displacement behaviors (normal behaviors that may occur at seemingly inappropriate times). For example, in certain stressful situations, macaques may pick at their hair, a behavior similar to hair twirling in humans. Importantly anxiolytic drugs that reduce the occurrence of these behaviors in humans have been shown to reduce these behaviors in non-human primates, suggesting a common biological mechanism.

One commonly used procedure to assess anxiety in non-human primates is the “Human Intruder Test” (HIT). This procedure was designed to evaluate an animal’s response to the “uncertainty” of the presence of an unfamiliar human. The species appropriate response when presented with this mild challenge is to remain still and vigilant; however, there is a range of responses, with some animals showing little response and others excessive freezing behavior. Variations of this procedure have used similar stimuli, including unfamiliar conspecifics and predatory threats (e.g., stuffed predator) to measure anxiety-related responses. Animals that exhibit heightened anxiety responses in the Human Intruder Test also show alterations in the same neurobiological systems affected in humans with anxiety disorders.

Barbary macaque. CC0 via Pixabay.

Barbary macaque. CC0 via Pixabay.Another class of anxiety tests in non-human primates relies on measuring physiological response following the presentation of an unexpected auditory or motor stimulus. For example, anxious people are more likely than others to react to a brief, unexpected sound with an exaggerated heart rate. Researchers have adopted similar methodology to assess startle response for nonhuman primates using a wide range of stimuli and physiological parameters.

Other research has focused on the cognitive processes involved in the regulation of anxiety responses. These tests of “cognitive bias” are based on the idea that an individual’s tendency to attend to potentially noxious stimuli tell us something about how the individual processes or weighs the experience. Therefore, an individual’s “anxious” state can be by assessed from his or her judgment about or attention to stimuli with different potentials to evoke anxiety. Cognitive bias procedures have been adapted and successfully employed in humans and other animals with similar response strategies across species, making these tests valuable comparative tools in our understanding of anxious behavior behavior.

Our review presents non-human primate models used by scientists in an effort to understand the biobehavioral mechanisms that mediate anxiety. The cross-species approach of modeling human psychopathology aims to discover targets for treatment toward the goal of reducing human suffering caused by anxiety disorders. Additionally, the knowledge gained from our investigation of anxiety-like behavior inform captive care of non-human primates. The studies reviewed have refined our understanding of factors that may result in anxiety-like behavior and provide information on how to manage them. Modeling psychopathology in non-human primates is necessary and critical to our understanding and treatment of these disorders in humans and nonhuman primates.

The post Anxiety in non-human primates appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDoes workplace stress play a role in retirement drinking?Evidence-based interventions in pediatric psychologyWorld Philosophy Day reading list

Related StoriesDoes workplace stress play a role in retirement drinking?Evidence-based interventions in pediatric psychologyWorld Philosophy Day reading list

World Philosophy Day reading list

World Philosophy Day was created by UNESCO in 2005 in order to “win recognition for and give strong impetus to philosophy and, in particular, to the teaching of philosophy in the world”. To celebrate World Philosophy Day, we have compiled a list of what we consider to be the most essential philosophy titles. We are also providing free access to several key journal articles and online products in philosophy so that you can explore this discipline in more depth. Happy reading!

Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will by Alfred R. Mele

Does free will exist? The question has fueled heated debates spanning from philosophy to psychology and religion. The answer has major implications, and the stakes are high. To put it in the simple terms that have come to dominate these debates, if we are free to make our own decisions, we are accountable for what we do, and if we aren’t free, we’re off the hook.

Philosophy Bites Again by David Edmonds and Nigel Warburton

This is really a conversation, and conversations are the best way to see philosophy in action. It offers engaging and thought-provoking conversations with leading philosophers on a selection of major philosophical issues that affect our lives. Their subjects include pleasure, pain, and humor; consciousness and the self; free will, responsibility, and punishment; the meaning of life and the afterlife.

Think: A Compelling Introduction to Philosophy by Simon Blackburn

Here at last is a coherent, unintimidating introduction to the challenging and fascinating landscape of Western philosophy. Written expressly for “anyone who believes there are big questions out there, but does not know how to approach them.”

What Does It All Mean? A Very Short Introduction to Philosophy by Thomas Nagel

In this cogent and accessible introduction to philosophy, the distinguished author of Mortal Questions and The View From Nowhere brings the central problems of philosophical inquiry to life, demonstrating why they have continued to fascinate and baffle thinkers across the centuries.

Riddles of Existence: A Guided Tour of Metaphysics by Earl Conee and Theodore Sider

Two leading philosophers explore the most fundamental questions there are, about what is, what is not, what must be, and what might be. It has an informal style that brings metaphysical questions to life and shows how stimulating it can be to think about them.

Killing in War by Jeff McMahan

This is a highly controversial challenge to the consensus about responsibility in war. Jeff McMahan argues compellingly that if the leaders are in the wrong, then the soldiers are in the wrong.

Reason in a Dark Time by Dale Jamieson

In this book, philosopher Dale Jamieson explains what climate change is, why we have failed to stop it, and why it still matters what we do. Centered in philosophy, the volume also treats the scientific, historical, economic, and political dimensions of climate change.

Poverty, Agency, and Human Rights edited by Diana Tietjens Meyers

Collects thirteen new essays that analyze how human agency relates to poverty and human rights respectively as well as how agency mediates issues concerning poverty and social and economic human rights. No other collection of philosophical papers focuses on the diverse ways poverty impacts the agency of the poor.

Aha! The Moments of Insight That Shape Our World by William B. Irvine

This book incorporates psychology, neurology, and evolutionary psychology to take apart what we can learn from a variety of significant “aha” moments that have had lasting effects. Unlike other books on intellectual breakthroughs that focus on specific areas such as the arts, Irvine’s addresses aha moments in a variety of areas including science and religion.

On What Matters: Volume One by Derek Parfit

Considered one of the most important works in the field since the 19th century, it is written in the uniquely lucid and compelling style for which Parfit is famous. This is an ambitious treatment of the main theories of ethics.

The Emergent Multiverse: Quantum Theory according to the Everett Interpretation by David Wallace

Quantum physics is the most successful scientific theory we have. But no one knows how to make sense of it. We need to bite the bullet – it’s common sense that must give way. The universe is much stranger than we can think.

The Best Things in Life: A Guide to What Really Matters by Thomas Hurka

An engaging, accessible survey of the different things that can make life worth living: pleasure, knowledge, achievement, virtue, love, and more. A book that considers what really matters in one’s life, and making decisions around those values.

What should I do?: Plato’s Crito’ in Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction by Edward Craig

What should I do?: Plato’s Crito’ in Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction by Edward Craig

Plato, born around 427 BC, is not the first important philosopher, with Vedas of India, the Buddha, and Confucius all pre-dating him. However, he is the first philosopher to have left us with a substantial body of complete works that are available to us today, which all take the form of dialogues. This chapter focuses on the dialogue called Crito in which Socrates asks ‘What should I do?’

A biography of John Locke in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

A philosopher regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers, John Locke was born on 29th August 1632 in Somerset, England. In the late 1650s he became interested in medicine, which led easily to natural philosophy after being introduced to these new ideas of mechanical philosophy by Robert Boyle. Discover what happened next in Locke’s life with this biography

‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ from Mind, published in 1950.

In this seminal paper, celebrated mathematician and pioneer Alan Turing attempts to answer the question, ‘Can machines think?’, and thus introduces his theory of ‘the imitation game’(now known as the Turing test) to the world. Turing skilfully debunks theological and ethical arguments against computational intelligence: he acknowledges the limitations of a machine’s intellect, while boldly exposing those of man, ultimately laying the groundwork for the study of artificial intelligence – and the philosophy behind it.

‘Phenomenology as a Resource for Patients’ from The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, published in 2012

Patient support tools have drawn on a variety of disciplines, including psychotherapy, social psychology, and social care. One discipline that has not so far been used to support patients is philosophy. This paper proposes that a particular philosophical approach, phenomenology, could prove useful for patients, giving them tools to reflect on and expand their understanding of their illness.

Do you have any philosophy books that you think should be added to this reading list? Let us know in the comments below.

Headline image credit: Rays at Burning Man by foxgrrl. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post World Philosophy Day reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLuciano Floridi responds to NYROB review of The Fourth RevolutionBioethics and the hidden curriculumShakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnets

Related StoriesLuciano Floridi responds to NYROB review of The Fourth RevolutionBioethics and the hidden curriculumShakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnets

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers