Oxford University Press's Blog, page 732

November 28, 2014

Slavery, rooted in America’s early history

No one can discuss American history without talking about the prevalence of slavery. When the Europeans attempted to colonize America in its early days, Indians and Africans were enslaved because they were “different from them”. The excerpt below from American Slavery: A Very Short Introduction follows the dark past of colonial America and how slavery proceeded to root itself deeply into history:

America held promises of wealth and freedom for Europeans; in time, slavery became the key to the fulfillment of both. Those who ventured to the lands that became the United States of America arrived determined to extract wealth from the soil, and they soon began to rely on systems of unpaid labor to accomplish these goals. Some also came with dreams of acquiring freedoms denied them in Europe, and paradoxically slavery helped to make those freedoms possible as well. As European immigrants to the colonies initiated a system of slavery, they chose to enslave only those who were different from them—Indians and Africans. A developing racist ideology marked both Indians and Africans as heathens or savages, inferior to white Europeans and therefore suited for enslavement. When continued enslavement of Indians proved difficult or against colonists’ self-interest, Africans and their descendants alone constituted the category of slave, and their ancestry and color came to be virtually synonymous with slave.

Although Europeans primarily enslaved Africans and their descendants, in the early 1600s in both northern and southern colonies, Africans were not locked into the same sort of lifetime slavery that they later occupied. Their status in some of the early colonies was sometimes ambiguous, but by the time of the American Revolution, every English colony in America—from Virginia, where the English began their colonization project, to Massachusetts, where Puritans made claims for religious freedom—had people who were considered lifetime slaves. To understand how the enslavement of Africans came about, it is necessary to know something of the broader context of European settlement in America.

In the winter of 1606, the Virginia Company, owned by a group of merchants and wealthy gentry, sent 144 English men and boys on three ships to the East Coast of the North American continent. English explorers had established the colony of Roanoke in Carolina in 1585, but when a ship arrived to replenish supplies two years later, the colony was nowhere to be found. The would-be colonists had either died or become incorporated into Indian groups. The English failed in their first attempt to establish a permanent colony in North America. Now they were trying again, searching for a place that would sustain and enrich them.

By the time the English ships got to the site of the new colony in April 1607, only 105 men and boys were left. Despite the presence of thousands of Algonquian-speaking Indians in the area, the leader of the English group planted a cross and named the territory on behalf of James, the new king of England. They established the Jamestown Settlement as a profit-making venture of the Virginia Company, but the colony got off to a bad start. The settlers were poorly suited to the rigors of colonization. To add to their troubles, the colony was located in an unhealthy site on the edge of a swamp. The new arrivals were often ill, plagued by typhoid and dysentery from lack of proper hygiene. Human waste spilled into the water supply, the water was too salty for consumption at times, and mosquitoes and bugs were rampant. No one planted foodstuffs. The colonists entered winter unprepared and only gifts of food from the Powhatan Indians saved them.

In the winter of 1609/10, a period that colonist John Smith called the “starving time,” several of the colonists resorted to cannibalism. According to Smith, some of the colonists dug up the body of an Indian man they had killed, boiled him with roots and herbs, and ate him. One man chopped up his wife and ate her. John Smith feared that the colony would disappear much as Roanoke had, so he established a militarized regime, divided the men into work gangs with threats of severe discipline, and told them that they would either work or starve. Smith’s dramatic strategy worked. The original settlers did not all die, and more colonists, including women and children, arrived from England to help build the struggling colony.

Tobacco Wharf in Colonial America. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Tobacco Wharf in Colonial America. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The first dozen years of the Jamestown Colony saw hunger, disease, and violent conflicts with the Native People, but it also saw the beginnings of a cash crop that could generate wealth for the investors in the Virginia Company back in England, as well as for planters within the colony. In 1617, the colonist John Rolfe brought a new variety of tobacco from the West Indies to Jamestown. In tobacco the colonists found the saleable commodity for which they had been searching, and they shipped their first cargo to England later that year. The crop, however, made huge demands on the soil. Cultivation required large amounts of land because it quickly drained soil of its nutrients. This meant that colonists kept spreading out generating immense friction with the Powhatan Indians who had long occupied and used the land. Tobacco was also a labor-intensive crop, and clearing land for new fields every few years required a great deal of labor. The colony needed people who would do the work.

Into this unsettled situation came twenty Africans in 1619. According to one census there were already some Africans in the Jamestown colony, but August 1619, when a Dutch warship moored at Point Comfort on the James River, marks the first documented arrival of Africans in the colony. John Rolfe wrote, “About the last of August came in a dutch man of warre that sold us twenty Negars.” According to Rolfe, “the Governor and Cape Marchant bought [them] for victuals at the easiest rates they could.” Colonists who did not have much excess food thought it worthwhile to trade food for laborers.

The Africans occupied a status of “unfreeness”; officials of the colony had purchased them, yet they were not perpetual slaves in the way that Africans would later be in the colony. For the most part, they worked alongside the Europeans who had been brought into the colony as indentured servants, and who were expected to work usually for a period of seven years to pay off the cost of their passage from England, Scotland, Wales, the Netherlands, or elsewhere in Europe. For the first several decades of its existence, European indentured servants constituted the majority of workers in the Jamestown Colony. Living conditions were as harsh for them as it was for the Africans as noted in the desperate pleas of a young English indentured servant who begged his parents to get him back to England.

In March 1623, Richard Frethorne wrote from near Jamestown to his mother and father in England begging them to find a way to get him back to England. He was hungry, feared coming down with scurvy or the bloody flux, and described graphically the poor conditions under which he and others in the colony lived. He was worse off, he said, than the beggars who came to his family’s door in England. Frethorne’s letter is a rare document from either white or black servants in seventeenth-century Virginia, but it certainly reflects the conditions under which most of them lived. The Africans, captured inland, taken to the coast, put on ships, taken to the Caribbean, and captured again by another nation’s ships, were even farther removed from any hope of redemption than Frethorne. Even if they could have written, they would have had no way of sending an appeal for help. As it happens, Frethorne was not successful either. His letter made it to London but remained in the offices of the Virginia Company. His parents probably never heard his appeal.

Featured headline image: Cotton gin harpers. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Slavery, rooted in America’s early history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe history of the newspaperThanksgiving with Benjamin FranklinWhat is African American religion?

Related StoriesThe history of the newspaperThanksgiving with Benjamin FranklinWhat is African American religion?

November 27, 2014

Thank you: musicians recall special ways their parents helped them blossom

“My thanks to my parents is vast,” says Toyin Spellman-Diaz, oboist with the Imani Winds woodwind quintet. “Without their help, I would never have become a musician.”

Many professional musicians I’ve interviewed have responded as Ms. Spellman-Diaz did, saying that their parents helped in so many ways: from locating good music teachers, schools, and summer programs, to getting them to lessons, rehearsals and performances on time, while also figuring out how to pay for it all. In addition, there are those reminders (often not well received) that parents tend to give about not forgetting to practice. Ms. Spellman-Diaz received her share of reminders, noting that “at some points, I didn’t feel like practicing. Dad’s going to be thrilled that I’ve admitted that it helped that he nagged me to practice. For decades he has been bugging me to admit that.”

But beyond these basics, when I ask musicians to recall something especially mhelpful that they’re thankful to their parents for in terms of furthering their musical development, the responses tend to focus on how a parent helped them find their own musical way.

Toyin Spellman-Diaz as a teenager, during a summer she spent at the Interlochen Arts Academy. Courtesy, Interlochen Arts Academy.

Toyin Spellman-Diaz as a teenager, during a summer she spent at the Interlochen Arts Academy. Courtesy, Interlochen Arts Academy. Toyin-Spellman Diaz: The non-musical goal her parents had while looking for a good private flute teacher for their daughter during elementary school had a profound effect on Ms. Spellman-Diaz’s musical future. “They wanted an African-American teacher so I could see a classical musician who looked like me, to show me that there were African-American classical musicians out there,” she says. Her second flute teacher was also black, as was one of the three oboe teachers she had during high school, after she switched instruments. “It absolutely made an impact and is partly why I play in the Imani Winds.” This woodwind quintet of African American musicians was started in 1997 with much the same goal her parents had: to show the changing face of classical music. However, one of her flute teachers was also into jazz. “I think my parents were trying to steer me toward jazz. They would have been really excited if I became a jazz flutist,” she says. But classical music won out, and that was fine, too. “With my parents, it was knowing when to let go and let me find my own voice, my own passion for it.”

Jonathan Biss: This pianist credits his parents with creating an “atmosphere that I didn’t feel I was doing it to please them or because it was good for me. I was doing it because I loved music.” When he was young, he too sometimes needed practice reminders. “But if they said, ‘Go practice,’ which wasn’t often, it was always accompanied by ‘if you want to do this.’ Their point was that you don’t have to do anything you don’t want to, but if you choose to do it, you have to do it well.”

Paula Robison: After she started flute at age eleven, her father realized that she had a special flair for it and “saw a possible life for me as a musician,” says Ms. Robison. He knew regular practice was essential, but he didn’t want to become an overbearing, nagging parent. So when she was twelve, they shook hands on an agreement: she promised to practice at a certain time every day and if she didn’t, it would be all right with her for him to remind her. That went well until one day during her early teens when she was “lounging around on the couch” during the hour she was supposed to practice. He reminded her of their agreement. She says she angrily “stomped up the stairs” to practice and “whirled around and shouted, ‘Someday I’m going to thank you for this!’” And she has. “I thank my father every time I pick up the flute.”

Liang Wang: When asked what he was most grateful to his parents for, this New York Philharmonic principal oboist says, “They allowed me to be what I wanted to be. A lot of parents want their kid to fit into what they think the kid should do. Oboe was an unusual choice. There aren’t many Chinese oboe players.” But he fell in love with the sound of the oboe. They supported him in his choice. He notes that his mother “wanted me to pursue my dream.”

Mark Inouye: When asked about the best musical advice he received as a young musician, Mark Inouye recalls something his father said to him at about age eleven, after a particularly disappointing Little League baseball game “in which I had played poorly,” says this principal trumpet with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. The pep talk his father gave him carried over to his beginning efforts on trumpet, too. He says his father told him, “You may not be the one with the most talent, but if you are the one who works the hardest, you will succeed.”

Sarah Chang: “Mom understood I had enough music teachers in my life. The best thing she did was leave the music part to everyone else and be a mom,” says violinist Sarah Chang, who started performing professionally at age eight. “Bugging me about taking my vitamins, eating my vegetables, fussing about the dresses I wore in concerts. . . She was always encouraging, my number-one supporter.”

Headline image credit: Classical Music. Notes. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Thank you: musicians recall special ways their parents helped them blossom appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe history of the newspaperA look at Thanksgiving favoritesAMS/SMT 2014: Highlights from the OUP booth

Related StoriesThe history of the newspaperA look at Thanksgiving favoritesAMS/SMT 2014: Highlights from the OUP booth

Leonard Cohen and smoking in old age

Leonard Cohen’s decision to take up cigarettes again at 80 reveals a well kept secret about older age: you can finally live it up and stop worrying about the consequences shortening your life by much. Risk taking is not such a risk anymore, given the odds. Of course some take that more literally than others. I don’t plan to do a parachute jump when I turn 90, as President Bush #1 did. However, a new breath of freedom (and less worry) is an unexpected and pleasant benefit of older age that isn’t well known.

Research findings confirm this is true. In recent studies of many adults from many countries, people were asked to rate their level of well being on a scale of 1-10. Researchers found a fascinating relationship between age and well-being. 20 year olds start out pretty high, after which well-being consistently goes down with age, bottoming out around the early 50’s. What happens next came as a surprise to many: after this trough, well-being actually goes up with age, with 85-year-olds reporting slightly higher well-being than the 20-year-olds. These are known as the U-bend studies, because well-being through adult life takes the shape of a “U.”

One question we can ask is: how can elders feel better when they are much closer to death than younger people? My personal and clinical experiences suggest that we accept the reality of death, which helps us enjoy each day and its positives more, because we appreciate their preciousness. Pleasure in listening to music, seeing a beautiful sunrise or hearing early morning bird calls elicits more enjoyment than when we were younger.

We live in the “now”. One woman expressed it well in our support group for aging and illness: “My papers are in order, my will and all that. Only, I just got four chairs recovered in my apartment. I want to stick around at least to see how they look with the new covers.” Concerns about career are gone; elderly parents are gone and adult children are on their own (hopefully). Elders begin to see life from a broader perspective than their own personal being—we are concerned about the future of the planet and the fate of our children’s children’s children whom we may never see.

Leonard Cohen. Photo by Rama. CeCILL, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR via Wikimedia Commons.

Leonard Cohen. Photo by Rama. CeCILL, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR via Wikimedia Commons. At 86, I heartily endorse Cohen’s decision to forego all the illness prevention and screening that made sense in his 50s but not in his 80s when it is not likely to prolong life. For me, that means enjoying the pleasures of food and drink as I choose. My modern vegetarian-ish children chide me for the red meat on the table and insist I should be serving kale smoothies and brown rice for dinner and drinking bottled water with lemon instead of alcohol. My husband of 89 and I enjoy beef and wine for dinner, and we have no plans to change that. As to more wholesome drinks, as a Texan, I have drunk Dr. Peppers since the age of 10. I could easily be a poster girl for its benefits, but I am warned about the dangers I run every day of their poisoning my brain by the artificial “everything” in them.

As to fall prevention, which is a big concern of our children, I understand their wishes to prevent a broken hip, but I love most of my rugs and they are part of the pleasure in my home. I will compromise just so far in taking them up. I will be prudent but not coerced into a life style my children feel is more appropriate for us. My colleague, Dr. Mindy Greenstein, is a psychologist who works with me in a geriatric research group, and with whom I compare notes on aging from our middle and old old age perspectives. I complain that my children act too “parental” at times and I remind her that at 91, if her father eats another latke beyond what his wife deems appropriate, is that really a make or break issue in his survival? Children want to help us oldsters to outsmart the Grim Reaper, and that is very tender. But eventually he wins. So why sweat the odds? We are lucky—and happy—to be here in our upper 80s.

The bottom line is that Cohen has it right about the freedom to do things we want over 80, but wrong about paying too much attention to calculating the prevention risk ratio. The best story to put this into perspective is the old man who went to his doctor and asked. “Doc, if I give up alcohol, cigarettes and women will I live longer?” The doctor replied, “No, but it will seem longer.”

The post Leonard Cohen and smoking in old age appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDoes workplace stress play a role in retirement drinking?Intergenerational perspectives on psychology, aging, and well-beingChemical warfare in terrestrial flatworms

Related StoriesDoes workplace stress play a role in retirement drinking?Intergenerational perspectives on psychology, aging, and well-beingChemical warfare in terrestrial flatworms

The history of the newspaper

On 28th November 1814 The Times in London was printed by automatic, steam powered presses for the first time. These presses, built by the German inventors Friedrich Koenig and Andreas Friedrich Bauer, meant that newspapers were now available to a new mass audience, and by 1815 The Times had a circulation of approximately 5,000 people. Now, 200 years later, newspapers around the globe inform millions of people about hundreds of topics, from current events and local news, to sports results, opinion pieces, and comic strips. The Times, along with many other newspapers, is now available online, on desktops, mobile phones, and tablets, with a circulation of over 390,000 people. Newspapers themselves date back further than November 1814, to the early 17th century when printed periodicals started replacing hand-written newssheets and the term ‘newspaper’ began to make its way into common vernacular. These first newspapers are defined as such because they were printed and dated, had regular publication intervals, and contained many different types of news. As the technology of printing improved, the spread of newspapers to more and more people grew – it may be said that as the physical printing press was invented, ‘the press’ as an entity came into being.

To celebrate this milestone in newspapers and printing we’ve brought together a reading list of free content across our online resources. Below you can discover more about the history of printing, its influence on society, how computers are used in the newspaper industry today, and much more:

‘What News?’ in The Invention of the Newspaper: English Newsbooks 1641-1649 by Joad Raymond

How did we find out about news before the newspaper? Before the publication of the newsbooks, the inhabitants of early-modern Britain had to rely on gossip, hearsay, occasional printed pamphlets and word-of-mouth to get to grips with what was going on outside of their communities. When newsbooks, the precursors to the modern-day newspaper, began to be printed in Britain in the 1640s, this, however, began to change. This chapter examines not just the literary and historical merit of these publications, but also analyses what they reveal about a burgeoning, British print culture.

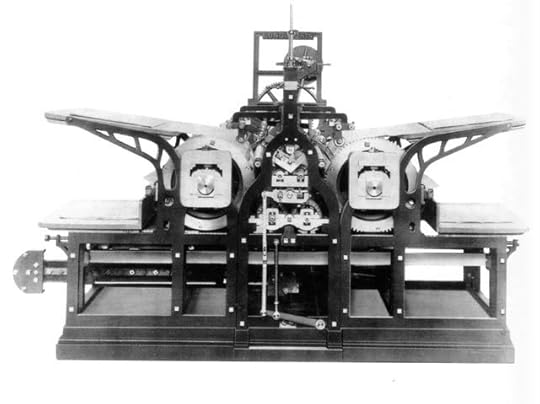

Koenig’s 1814 steam-powered printing press. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Koenig’s 1814 steam-powered printing press. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. ‘Printing and Printedness’ in The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern European History, Volume 1 (Forthcoming) by James Raven

From Gutenberg’s printed bibles in 1438 to the advent of newspaper printing in the 17th century, the social, economic, and political implications of newspaper production and circulation transformed early modern Europe into a more socially aware society. The introduction of new typographical styles allowed for a more accessible and inclusive written history, contributing to a rise in European literacy no longer restricted to the upper classes. Raven tracks the impact of this evolving “print culture” on job creation and industrialization, demographic variation and new literary forms, and geographical innovations resulting from periodical dissemination.

‘Uses of Computing in Print Media Industries: Book Publishing, Newspapers, Magazines’ in The Digital Hand: Volume II: How Computers Changed the Work of American Financial, Telecommunications, Media, and Entertainment Industries by James W. Cortada

The rise of the computer has been a relatively sudden and recent one, and yet has changed almost every facet of our daily lives – from how we entertain ourselves, to how we communicate with each other, and much more. One field in which computers have come to reign supreme is the workplace, and this chapter examines the huge impact they have had on the world of print media industries, including book, newspaper, and magazine publishing.

‘Gossip and Scandal: Scrutinizing Public Figures’ in Family Newspapers?: Sex, Private Life, and the British Popular Press 1918-1978 by Adrian Bingham

Our attitudes towards celebrities, and how they are reported in the news media, have changed drastically throughout the last century. During the time of Edward VIII’s affair with American socialite Wallis Simpson in the 1930s, the press – in marked contrast to how they would have reacted today – remained silent. Things began to change in the 1950s, however, as a market developed in Britain for sensational and scandalous stories featuring the celebrities of the era. This chapter then analyses the relevance of the Profumo Affair which broke in 1963, as an example of the increasing invasive investigations undertaken by the industry.

‘Murder is my meat: the ethics of journalism’ in Journalism: A Very Short Introduction by Ian Hargreaves

Journalism in all forms, including newspapers, must intrinsically be truthful and accurate. Without either of these the trust of the journalist or newspaper is undermined, so codes, laws, and standards have been put in place in order to eliminate serious misconduct. This chapter reflects on the UK phone-hacking scandal and considers the ethical issues that surround journalism today.

‘Clicking on What’s Interesting, Emailing What’s Bizarre or Useful, and Commenting on What’s Controversial’ in The News Gap: When the Information Preferences of the Media and the Public Diverge edited by Pablo J. Boczkowski and Eugenia Mitchelstein

With the advent of the internet and mobile devices, how does society now read newspapers? With the increasing digitisation of news content, we are starting to consume and interact with news stories in different, complex ways. Taking a closer look at the data behind our interaction with online news content, this chapter analyses what might make us click on an article, and why we might comment on one, whilst emailing another to friends or family.

Headline image credit: Newspaper stack. Image by Ivy Dawned. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Flickr.

The post The history of the newspaper appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBand Aid (an infographic)Peanut butter: the vegetarian conspiracyIntersections of documentary and avant-garde filmmaking

Related StoriesBand Aid (an infographic)Peanut butter: the vegetarian conspiracyIntersections of documentary and avant-garde filmmaking

November 26, 2014

A look at Thanksgiving favorites

What started as a simple festival celebrating the year’s bountiful harvest has turned into an archetypal American holiday, with grand dinners featuring savory and sweet dishes alike. Thanksgiving foods have changed over the years, but there are still some iconic favorites that have withstood time. Hover over each food below in this interactive image and find out more about their role in this day of feasting:

What are your favorite Thanksgiving dishes? Let us know in the comments below!

The post A look at Thanksgiving favorites appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA map of the world’s cuisineNine types of meat you may have never triedWhat’s your gut feeling?

Related StoriesA map of the world’s cuisineNine types of meat you may have never triedWhat’s your gut feeling?

Monthly etymology gleanings for November 2014

As always, I want to thank those who have commented on the posts and written me letters bypassing the “official channels” (though nothing can be more in- or unofficial than this blog; I distinguish between inofficial and unofficial, to the disapproval of the spellchecker and some editors). I only wish there were more comments and letters. With regard to my “bimonthly” gleanings, I did think of calling them bimestrial but decided that even with my propensity for hard words I could not afford such a monster. Trimestrial and quarterly are another matter. By the way, I would not call fortnightly a quaint Briticism. The noun fortnight is indeed unknown in the United States, but anyone who reads books by British authors will recognize it. It is sennight “seven nights; a week,” as opposed to “fourteen nights; two weeks,” that is truly dead, except to Walter Scott’s few remaining admirers.

The comments on livid were quite helpful, so that perhaps livid with rage does mean “white.” I was also delighted to see Stephen Goranson’s antedating of hully gully. Unfortunately, I do not know this word’s etymology and have little chance of ever discovering it, but I will risk repeating my tentative idea. Wherever the name of this game was coined, it seems to have been “Anglicized,” and in English reduplicating compounds of the Humpty Dumpty, humdrum, and helter-skelter type, those in which the first element begins with an h, the determining part is usually the second, while the first is added for the sake of rhyme. If this rule works for hully gully, the clue to the word’s origin is hidden in gully, with a possible reference to a dupe, a gull, a gullible person; hully is, figuratively speaking, an empty nut. A mere guess, to repeat once again Walter Skeat’s favorite phrase.

The future of spelling reform and realpolitikSome time ago I promised to return to this theme, and now that the year (one more year!) is coming to an end, I would like to make good on my promise. There would have been no need to keep beating this moribund horse but for a rejoinder by Mr. Steve Bett to my modest proposal for simplifying English spelling. I am afraid that the reformers of our generation won’t be more successful than those who wrote pleading letters to journals in the thirties of the nineteenth century. Perhaps the Congress being planned by the Society will succeed in making powerful elites on both sides of the Atlantic interested in the sorry plight of English spellers. I wish it luck, and in the meantime will touch briefly on the discussion within the Society.

Number 1 by OpenClips. CC0 via Pixabay.

Number 1 by OpenClips. CC0 via Pixabay. In the past, minimal reformers, Mr. Bett asserts, usually failed to implement the first step. The first step is not an issue as long as we agree that there should be one. Any improvement will be beneficial, for example, doing away with some useless double letters (till ~ until); regularizing doublets like speak ~ speech; abolishing c in scion, scene, scepter ~ scepter, and, less obviously, scent; substituting sk for sc in scathe, scavenger, and the like (by the way, in the United States, skeptic is the norm); accepting (akcepting?) the verbal suffix -ize for -ise and of -or for -our throughout — I can go on and on, but the question is not where to begin but whether we want a gradual or a one-fell-swoop reform. Although I am ready to begin anywhere, I am an advocate of painless medicine and don’t believe in the success of hav, liv, and giv, however silly the present norm may be (those words are too frequent to be tampered with), while til and unskathed will probably meet with little resistance.

I am familiar with several excellent proposals of what may be called phonetic spelling. No one, Mr. Bett assures me, advocates phonetic spelling. “What about phonemic spelling?” he asks. This is mere quibbling. Some dialectologists, especially in Norway, used an extremely elaborate transcription for rendering the pronunciation of their subjects. To read it is a torture. Of course, no one advocates such a system. Speakers deal with phonemes rather than “sounds.” But Mr. Bett writes bás Róman alfàbet shud rèmán ùnchánjd for “base Roman alphabet should remain unchanged.” I am all for alfabet (ph is a nuisance) and with some reservations for shud, but the rest is, in my opinion, untenable. It matters little whether this system is clever, convenient, or easy to remember. If we offer it to the public, we’ll be laughed out of court.

Mr. Bett indicates that publishers are reluctant to introduce changes and that lexicographers are not interested in becoming the standard bearers of the reform. He is right. That is why it is necessary to find a body (The Board of Education? Parliament? Congress?) that has the authority to impose changes. I have made this point many times and hope that the projected Congress will not come away empty-handed. We will fail without influential sponsors, but first of all, the Society needs an agenda, agree to the basic principles of a program, and for at least some time refrain from infighting.

The indefinite pronoun one once againI was asked whether I am uncomfortable with phrases like to keep oneself to oneself. No, I am not, and I don’t object to the sentence one should mind one’s own business. A colleague of mine has observed that the French and the Germans, with their on and man are better off than those who grapple with one in English. No doubt about it. All this is especially irritating because the indefinite pronoun one seems to owe its existence to French on. However, on and man, can function only as the subject of the sentence. Nothing in the world is perfect.

Sir John Vanbrugh by Thomas Murray (died 1735). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sir John Vanbrugh by Thomas Murray (died 1735). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Our dance around pronouns sometimes assumes grotesque dimensions. In an email, a student informed me that her cousin is sick and she has to take care of them. She does not know, she added, when they will be well enough, to allow her to attend classes. Not that I am inordinately curious, but it is funny that I was protected from knowing whether “they” are a man or a woman. In my archive, I have only one similar example (I quoted it long ago): “If John calls, tell them I’ll soon be back.” Being brainwashed may have unexpected consequences.

Earl and the HeruliansOur faithful correspondent Mr. John Larsson wrote me a letter about the word earl. I have a good deal to say about it. But if he has access to the excellent but now defunct periodical General Linguistics, he will find all he needs in the article on the Herulians and earls by Marvin Taylor in Volume 30 for 1992 (the article begins on p. 109).

The OED: Behind the scenesMany people realize what a gigantic effort it took to produce the Oxford English Dictionary, but only insiders are aware of how hard it is to do what seems trivial to a non-specialist. Next year we’ll mark the centennial of James A. H. Murray’s death, and I hope that this anniversary will not be ignored the way Skeat’s centennial was in 2012. Today I will cite one example of the OED’s labors in the early stages of work on it. In 1866, Cornelius Payne, Jun. was reading John Vanbrugh’s plays for the projected dictionary, and in Notes and Queries, Series 3, No. X for July 7 he asked the readers to explain several passages he did not understand. Two of them follow. 1) Clarissa: “I wish he would quarrel with me to-day a little, to pass away the time.” Flippanta: “Why, if you please to drop yourself in his way, six to four but he scolds one Rubbers with you.” 2) Sir Francis:…here, John Moody, get us a tankard of good hearty stuff presently. J. Moody: Sir, here’s Norfolk-nog to be had at next door.” Rubber(s) is a well-known card term, and it also means “quarrel.” See rubber, the end of the entry. Norfolk-nog did not make its way into the dictionary because no idiomatic sense is attached to it: the phrase means “nog made and served in Norfolk” (however, the OED did not neglect Norfolk). Such was and still is the price of every step. Read and wonder. And if you have a taste for Restoration drama, read Vanbrugh’s plays: moderately enjoyable but not always fit for the most innocent children (like those surrounding us today).

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for November 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe ayes have itOn idioms in general and on “God’s-Acre” in particularMonthly etymology gleanings for October 2014, Part 2

Related StoriesThe ayes have itOn idioms in general and on “God’s-Acre” in particularMonthly etymology gleanings for October 2014, Part 2

The Classical World from A to Z

For over 2,000 years the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome have captivated our collective imagination and provided inspiration for many aspects of our lives, from culture, literature, drama, cinema, and television to society, education, and politics. With over 700 entries on everything and anything related to the classical world in the Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization, we created an A-Z list of facts you should know about the time period.

Alexander the Great: He believed himself the descendent of Heracles, Perseus, and Zeus. By 331 he had begun to represent himself as the direct son of Zeus, with dual paternity comparable to that of Heracles.

Baths: Public baths, often located near the forum (civic centre), were a normal part of Roman towns in Italy by the 1st century BC, and seem to have existed at Rome even earlier. Bathing occupied a central position in the social life of the day.

Christianity: By the end of the 4th century, Christianity had largely triumphed over its religious competition, although a pagan Hellenic tradition would continue to flourish in the Greek world and rural and local cults also persisted.

Democracy: Political rights were restricted to adult male Athenians. Women, foreigners, and slaves were excluded. An Athenian came of age at 18 when he became a member of his father’s deme and was enrolled in the deme’s roster, but as epheboi, most young Athenians were liable for military service for two years, before at the age of 20, they could be enrolled in the roster of citizen who had access to the assembly. Full political rights were obtained at 30 when a citizen was allowed to present himself as candidate at the annual sortation of magistrate and jurors.

The goddess Juno. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The goddess Juno. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. Education, Greek: Greek ideas of education, whether theoretical or practical, encompassed upbringing and cultural training in the widest sense, not merely school and formal education. The poets were regarded as the educators of their society.

Food and drink: The Ancient diet was based on cereals, legumes, oil, and wine. Meat was a luxury for most people.

Gems: Precious stones were valued in antiquity as possessing magical and medicinal virtues, as ornaments, and as seals when engraved with a device.

Hephaestus was the Greek god of fire, of blacksmiths, and of artisans.

Ivory plaques at all classical periods decorated furniture and were used for the flesh parts of cult statues and for temple doors.

Juno was an old and important Italian goddess and one of the chief deities of Rome. Her name derives from the same root as iuventas (youth), but her original nature remains obscure.

Kinship in antiquity constituted a network of social relationship constructed through marriage and legitimate filiation, and usually included non-kin — especially slaves.

Libraries: The Great Roman libraries provided reading-rooms, one for Greek and one for Latin with books in niches around the walls. Books would generally be stored in cupboards which might be numbered for reference.

Marriage in the ancient world was a matter of personal law, and therefore a full Roman marriage could exist only if both parties were Roman citizen or had the right to contract marriage, either by grant to a group or individually.

Narrative: An interest in the theory of narrative is already apparent in Aristotle, whose Poetics may be considered the first treatise of narratology.

Ostracism in Athenian society the 5th century BC was a method of banishing a citizen for ten years. It is often hard to tell why a particular man was ostracized. Sometimes the Athenians seem to have ostracized a man to express their rejection of a policy for which he stood for.

Plato of Athens descended from wealthy and influential Athenian families on both sides. He rejected marriage and the family duty of producing citizen sons; he founded a philosophical school, the Academy; and he published written philosophical works.

Quintilian, a Roman rhetorician, advised that children start learning Greek before Latin. The Roman Empire was bilingual at the official, and multilingual at the individual and non-official, level.

Ritual: The central rite of Greek and Roman religion is animal sacrifice. It was understood as a gift to the gods.

Samaritans, the inhabitants of Samaria saw themselves as the direct descendants of the northern Israelite tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh, left behind by the Assyrians in 722 BC.

Temple of Zeus. Photo by David Stanley. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Temple of Zeus. Photo by David Stanley. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. Toga: The toga was the principal garment of the free-born Roman male. As a result of Roman conquest the toga spread to some extent into the Roman western provinces, but in the east it never replaced the Greek rectangular mantle.

Urbanization: During the 5th, 4th, and 3rd centuries, urban forms spread to mainland northern Greece, both to the seaboard under the direct influence of southern cities, and inland in Macedonia, Thessaly, and even Epirus, in association with the greater political unification of those territories.

Venus: From the 3rd century BC, Venus was the patron of all persuasive seductions, between gods and mortals, and between men and women.

Wine was the everyday drink of all classes in Greece and Rome. It was also a key component of one of the central social institutions of the élite, the dinner and drinking party. On such occasions large quantities of wine were drunk, but it was invariably heavily diluted with water. It was considered a mark of uncivilized peoples, untouched by Classical culture, that they drank wine neat with supposed disastrous effects on their mental and physical health.

Xanthus was called the largest city in Lycia (southern Asia Minor). The city was known to Homer, and Herodotus described its capitulation to Persia in the famous siege of 545 BC.

Zeus, the Indo-European god of the bright sky, is transformed in Greece into Zeus the weather god, whose paramount and specific place of worship is a mountain top.

Featured image: Colosseum in Rome, Italy — April 2007 by Diliff. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Classical World from A to Z appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTiberius on Capri: in pursuit of vice or just avoiding mother?The literature and history of ChaucerBand Aid (an infographic)

Related StoriesTiberius on Capri: in pursuit of vice or just avoiding mother?The literature and history of ChaucerBand Aid (an infographic)

Thanksgiving and the economics of sharing

For this American, my favorite holiday has always been Thanksgiving. Why? I have an image in my mind of Native Americans and colonists meeting and sharing food together; they share knowledge and stories. In the midst of their concerns about each other, they found respect for each other. Their spirit of sharing is a great inspiration.

As an economist in this upside-down world of people stressing over their future and present, I find answers in that image of Thanksgiving. People eventually survive by sharing with each other as a community. The poor are fed. The sick are cared for. The struggling are helped, and communal ties are strengthened.

Thanksgiving morning at Lake Tahoe. Photo by Beau Rogers. CC BY-NC 2.0 via beaurogers Flickr

Thanksgiving morning at Lake Tahoe. Photo by Beau Rogers. CC BY-NC 2.0 via beaurogers Flickr There is a term in economics, social capital. This term refers to the cultural interactions within a society forming cohesion, coordination, and cooperation that allow an economy to function better. An economy relies on people from diverse backgrounds talking, sharing concerns, negotiating, making plans, and working toward common goals. The social quality of their communication determines the true strength and potential of their economy.

When the Native Americans and the colonists met and shared, I see social capital being built. The society became stronger. People would be better able to have their needs met. There would be less conflict and more enjoyment of work. The society would be able to grow in potential.

The focus of my research as an economist is in the area of labor share, which is the percentage of the income from production that is shared with labor. I research how changes in labor share affect such things as potential production, employment, productivity, investment, and even monetary policy from a central bank.

In almost all advanced countries, even in China where labor share was already low, labor share has fallen in an exorbitant way since the turn of the century. What has been the effect of labor receiving less share of a national income? Potential output has fallen. Unemployment will be higher than before. Productivity growth will stall much quicker, or even fall as in the United Kingdom. Nominal interest rates from central banks will be stuck near 0%.

The fall in labor share represents a problem in the social capital of advanced countries. Labor is being excluded from economic development. Their concerns are not being heard, while corporate profits extend to new records. Labor’s wages are expected to fall in order for companies to be more competitive globally.

Stop. Take a moment of silence.

Acknowledge the growing problem of inequality, and return now to celebrate this holiday of Thanksgiving. Within this day exists the answers to our economic concerns. As societies, we only need to share more. And in sharing, we show our respect for the value of people within society.

A man can’t get rich if he takes proper care of his family.

The Navajo, or Diné, have a saying: “A man can’t get rich if he takes proper care of his family.” The wisdom embodied in this saying is immense. The wisdom not only assures the strength of each member of the community by building social capital, but it assures a stronger economy.

Now we need to answer the question: Who is family?

Here comes the true meaning of Thanksgiving: We are all family. The poor, the rich, the uneducated, the educated, the powerful, and the powerless, as well as those of different races and cultures. Families, friends, and strangers are invited into our homes to celebrate Thanksgiving. The abundance is shared and ties of respect are celebrated.

The extent to which a society can see everyone within the society as family determines the potential of their economy and eventually the quality of life. So Thanksgiving is a moment to celebrate how different people can embrace each other in a spirit of sharing. In that sharing, a broader vision of family is cultivated. In that vision, sick economies can be healed.

Featured image ‘Home to Thanksgiving’ litohraph by Currier and Ives (1867). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Thanksgiving and the economics of sharing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe not so thin blue line: policing economic crimeThanksgiving with Benjamin FranklinTop 10 Turkey-Dumping Day breakup songs

Related StoriesThe not so thin blue line: policing economic crimeThanksgiving with Benjamin FranklinTop 10 Turkey-Dumping Day breakup songs

AMS/SMT 2014: Highlights from the OUP booth

We had a great time at this year’s AMS/SMT meeting! Milwaukee was a bit chilly, but we drank lots of coffee, cozied up with thrilling new books, and listened to some fantastic presentations!

Weren’t able to make it, or just feeling nostalgic? Take a tour through the eyes of OUP music, and check out some memorable highlights from this year’s joint meeting:

Check out the OUP booth all ready for AMS/SMT!

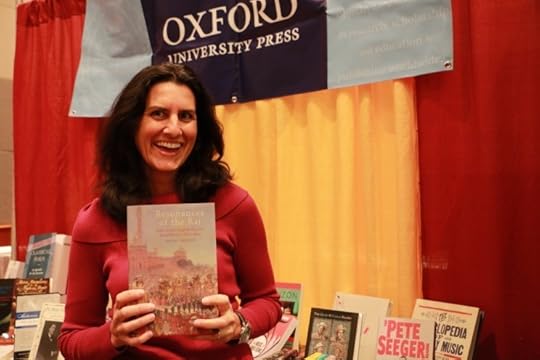

Check out the OUP booth all ready for AMS/SMT!  Smile, and say, 'OXFORD!' Nalini Ghuman poses with her book, 'Resonances of the Raj'!

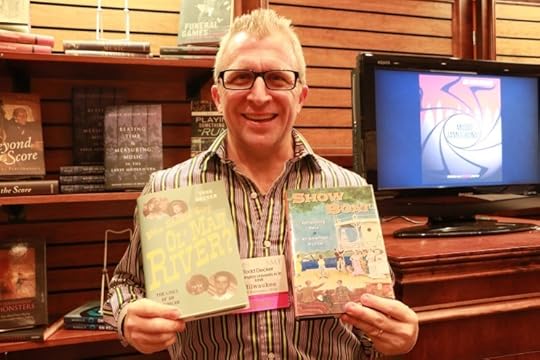

Smile, and say, 'OXFORD!' Nalini Ghuman poses with her book, 'Resonances of the Raj'!  Not one, but TWO! Todd Decker posing with both of his books at AMS/SMT, 'Who Should Sing, Ol' Man River?' and 'Show Boat'

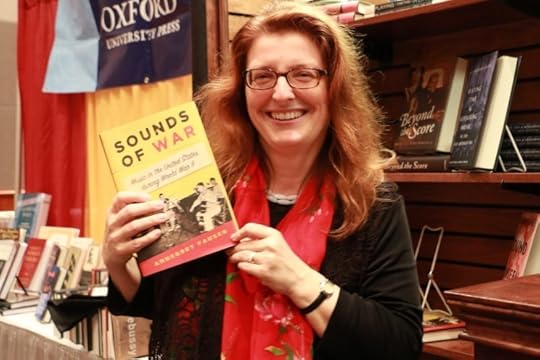

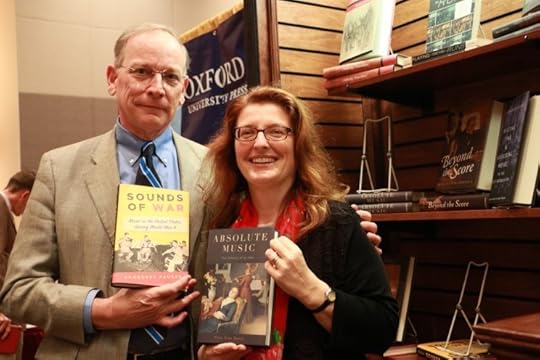

Not one, but TWO! Todd Decker posing with both of his books at AMS/SMT, 'Who Should Sing, Ol' Man River?' and 'Show Boat'  Annegret Fauser, winner of this year's Music in American Culture Award of the American Musicological Society, is happy to see her book, 'Sounds of War' at the OUP Booth!

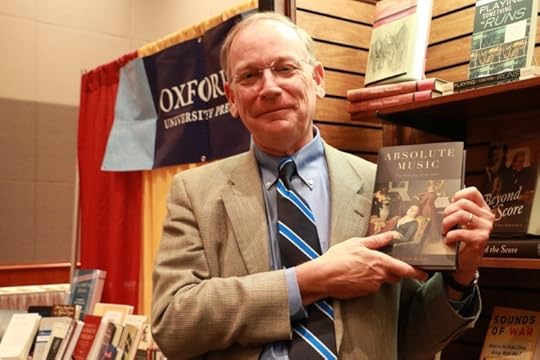

Annegret Fauser, winner of this year's Music in American Culture Award of the American Musicological Society, is happy to see her book, 'Sounds of War' at the OUP Booth!  Mark Evan Bonds holding up his book, 'Absolute Music'

Mark Evan Bonds holding up his book, 'Absolute Music'  I spy a swap! Annegret Fauser and Mark Evan Bonds showcasing eachother's books at the OUP booth

I spy a swap! Annegret Fauser and Mark Evan Bonds showcasing eachother's books at the OUP booth  Mark J. Butler Posing with his book, "Playing with Something that Runs"

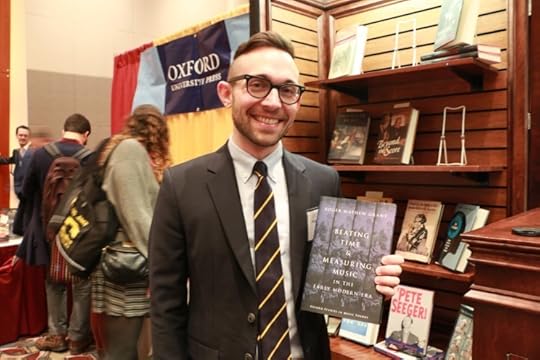

Mark J. Butler Posing with his book, "Playing with Something that Runs"  Look what I found! Mark J. Butler posing with his former student's book, 'Beating Time and Measuring Music in the Early Modern Era' by Roger Mathew Grant

Look what I found! Mark J. Butler posing with his former student's book, 'Beating Time and Measuring Music in the Early Modern Era' by Roger Mathew Grant  Spotted OUP author Roger Mathew Grant and his new book, "Beating Time and Measuring Music in the Early Modern Era" hanging out at the OUP booth!

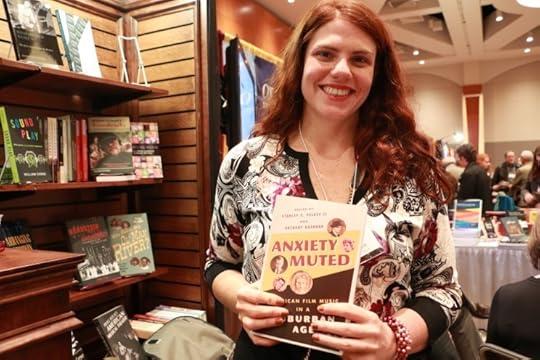

Spotted OUP author Roger Mathew Grant and his new book, "Beating Time and Measuring Music in the Early Modern Era" hanging out at the OUP booth!  'Anxiety Muted' contributor, Meghan Schrader, strikes a pose!

'Anxiety Muted' contributor, Meghan Schrader, strikes a pose!  Fantastic view from the Skywalk from the Milwaukee Hilton to the Milwaukee Convention Center!

Fantastic view from the Skywalk from the Milwaukee Hilton to the Milwaukee Convention Center!  You know you're in Milwaukee when ... POLKA!

You know you're in Milwaukee when ... POLKA!  Teardown adventures after doors close. Goodbye for now!

Teardown adventures after doors close. Goodbye for now! You can find out more information about the AMS/SMT 2014 conference by visiting their website. We already can’t wait for next year!

The post AMS/SMT 2014: Highlights from the OUP booth appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBand Aid (an infographic)Keytar Appreciation 101Bae in hip hop lyrics

Related StoriesBand Aid (an infographic)Keytar Appreciation 101Bae in hip hop lyrics

November 25, 2014

Religion and the paranormal

OUP author Diana Walsh Pasulka recently caught up with fellow scholar of religion Jeffrey J. Kripal, to discuss the study of the supernatural and the paranormal within the university.

Diana Walsh Pasulka: You’ve written about the origin of the term paranormal and its link to the British and American Spiritualist movements. You’ve noted that the paranormal is inextricably linked to the idea of the sacred. How do you see the paranormal as different from the idea of the supernatural, which has traditionally been used to describe events that exceed naturalist explanations, like miracles, for instance?

Jeffrey J. Kripal: As a category or coinage, the paranormal is an attempted secularization of the supernatural. I like to translate it as the “super natural.” This is what the original inventors of the term meant, anyway. They meant to suggest that (a) psychical phenomena were quite real but (b) beyond our present scientific modeling and theorizing. The phenomena in question were thus both “normal” but also “beyond” (para-). Someday, these theorists thought, we would be able to incorporate these phenomena into our understanding of the natural world. So, for example, poltergeist phenomena were read not as the work of “angry ghosts” floating around but as expressions of the “ghosts of anger,” that is, they understood these as exteriorized symbolic expressions of pent-up frustration, conflict or angst. This may have been an advance, but it is still deeply offensive to our rationalisms. How, say, an abused or conflicted adolescent can start the curtains on fire or explode a vase at a distance might still be natural, but this is clearly a nature behaving in some most extraordinary or special ways. This is a kind of supernature.

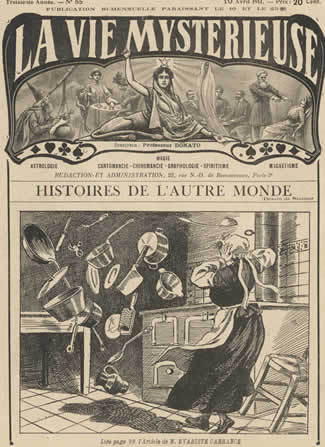

A 14-year-old domestic servant, Therese Selles, experiences poltergeist / spontaneous PK activity in the home of her employer, the Todeschini family at Cheragas, Algeria, as featured on the cover of the French magazine La Vie Mysterieuse in 1911. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A 14-year-old domestic servant, Therese Selles, experiences poltergeist / spontaneous PK activity in the home of her employer, the Todeschini family at Cheragas, Algeria, as featured on the cover of the French magazine La Vie Mysterieuse in 1911. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Diana Walsh Pasulka: In your most recent work you’ve called for a renewed examination of the supernatural and paranormal aspects of religion. You’ve also noted the irony that scholars of religion have tended to avoid these subjects even as they are presumably at the heart of most religious traditions. Can you say a bit more about how you would like to see this renewed emphasis develop? For example, is this an interdisciplinary project?

Jeffrey J. Kripal: I find it curious that the study of religion has “taken off the table” precisely those anomalous aspects of human experience that lie behind or within some of the most universally distributed religious ideas–say, strikingly real encounters with dead loved ones who carry some empirical information (say, about the means or mode of their death) that in turn give rise to the belief in a surviving “soul.” We are allowed to treat these beliefs as “discourses” or as power-plays, of course, but never as empirical phenomena in their own right. Then we are told that there is nothing essentially “religious” about religion, that it is all just context and construction, which, of course, is perfectly true, since we just took all of the stuff that is not just context and construction off the table. I find this situation circular, inadequate and, above all, depressing. It is not that it is wrong. It is simply that it is half-right. I think it is time to bring the other half back in and re-enchant reason.

Diana Walsh Pasulka: You’ve stated that popular culture has adopted the paranormal elements that have been well documented in the history of religion and folklore. Do you see popular culture, science fiction and superhero movies, for instance, replacing this aspect of religion? Or, perhaps, complimenting it? Or, does this development indicate something entirely different?

Jeffrey J. Kripal: I think the paranormal has migrated into popular culture and entertainment because it has been effectively exiled from both elite intellectual culture (which is more or less controlled now by scientific or Marxist materialism) and, oddly, the religious traditions themselves. But paranormal phenomena are clearly part of our human nature, part of human history. If we will not talk about them either in our public intellectual and scientific lives or in our public religious lives, where are they supposed to go? They will never go away, by the way, not at least as long as we are here, and for one simple reason: they are expressions of us.

Headline image credit: Urach waterfall. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Religion and the paranormal appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRepresentations of purgatory and limbo in popular cultureThe Catholic SupernaturalThe past, present, and future of overlapping intellectual property rights

Related StoriesRepresentations of purgatory and limbo in popular cultureThe Catholic SupernaturalThe past, present, and future of overlapping intellectual property rights

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers