Oxford University Press's Blog, page 729

December 4, 2014

Prophecy, demonology, and the Extraordinary Synod of Bishops on the Family

From 5-19 October 2014, Pope Francis held the Extraordinary Synod of Bishops on the Family in Rome. The purpose of the synod was to discuss the Church’s stance on such issues as divorce, birth control, and especially, the legalization of gay marriage. On 13 October, the Synod released a relatio (a mid-term report) on its preliminary findings. Paragraph 50 of the relatio stated:

Homosexuals have gifts and qualities to offer to the Christian community. Are we capable of providing for these people, guaranteeing them a place of fellowship in our communities? Oftentimes, they want to encounter a Church which offers them a welcoming home. Are our communities capable of this, accepting and valuing their sexual orientation, without compromising Catholic doctrine on the family and matrimony?

Even though the paragraph was phrased more as a question than a statement, it was immediately pronounced an “earthquake” in the history of Catholicism. Apparent sympathy toward homosexuals delighted liberal Catholics while horrifying conservatives and traditionalists. When the synod concluded, this language was removed from the final version of the document, having failed to acquire a necessary two-thirds vote from participants.

Although the Mother Church has always held synods and councils to reassess doctrines and practices, it presents itself as timeless and immutable. In the nineteenth century American bishop John Ireland mused, “The church never changes and yet she changes.” When change does occur (or is even suggested), conservatives often respond with horror. The paradox of an unchangeable, changing Church creates what sociologist Peter Berger calls a grenzsituation (drawing on the work of psychologist Karl Jaspers), in which a taken for granted reality suddenly appears alien and factitious. To articulate their feeling of betrayal, critics of Church Reform frequently invoke the language of evil and the demonic.

“Vatican Sunset – Rome, Italy – Easter 2008” (2008) by Giorgio Galeotti. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Vatican Sunset – Rome, Italy – Easter 2008” (2008) by Giorgio Galeotti. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. Following the “earthquake” of 13 October, those opposed to the relatio used a variety of strategies to express their dissent including legalistic arguments, suggestions that devil was confusing the synod, hints of conspiracy, and even snippets of prophecy delivered by Marian seers at Fatima and other apparition sites. This response demonstrated the same constellation of forces that occurred in the aftermath of Vatican II when traditionalist Catholics turned to a homemaker from Queens who claimed to see visions of the Virgin Mary. Veronica Lueken, “The Seer of Bayside,” was declared “the seer of age” primarily because her prophecies offered a framework by which traditionalists could make sense of the radical changes of Vatican II. Lueken’s most controversial revelation was that Paul VI––the pope who approved the Council’s reforms––had been replaced by a Soviet doppelganger. Accordingly, loyal Catholics were justified in rejecting Vatican II because it was, in reality, the product of a demonic conspiracy unfolding in the final days.

Today, as in the 1970s, conservative Catholics express pain and outrage that a pope would challenge their understanding of what it means to be Catholic. Some have presented legalistic arguments, citing such documents as a 1986 letter from the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith that described homosexuality as “an objective disorder.” But repeatedly, conservatives have articulated their dissent by invoking a dark triad of demonology, conspiracy theory, and millennial prophecy.

On 20 October, Archbishop Charles Chaput gave a talk entitled “Stranger in a Strange Land,” in which he suggested that Catholics were now the targets of intolerance for advocating traditional family values. When asked about the synod, Chaput first specified that he had not been there and that the media might be distorting what was actually said. He then added, “I think confusion is of the devil, and I think the public image that came across was one of confusion.”

In the Catholic magazine First Things, Peter Leithart discussed the synod in terms of spiritual warfare, suggesting that advocates of gay marriage are the victims of demonic deception. He explained, “When Christians see something that looks like a collective delusion, they’re looking at demonic deception and/or divine judgment. We live in a culture that has venerated idol-ologies of unbounded freedom with relentless zeal, and God has given us over to the logic of our folly.”

Others invoked the language of willful betrayal and conspiracy, rather than demonically-inspired confusion. John Smeaton, co-founder of Voice of the Family, commented, “Those who are controlling the Synod have betrayed Catholic parents worldwide. We believe that the Synod’s mid-way report is one of the worst official documents drafted in Church history.” In this assessment, it is not the synod itself that has betrayed Catholic families, but by a shadowy “them” who are controlling it.

“Rosary” (2005) by Michael Peligro. CC BY-ND 2.o via Flickr.

“Rosary” (2005) by Michael Peligro. CC BY-ND 2.o via Flickr. Outside the sphere of mainstream discourse, traditionalist groups have been much more explicit in framing the synod in terms of an apocalyptic war with Satan. Lueken died in 1995, but her followers, known as “Baysiders,” strongly opposed the 13 October announcement. These Last Days Ministries, a Baysider, website, prefaced a report on the relatio with a prophecy delivered by Lueken on behalf of Jesus on 3 May 1978:

The Eternal Father has given mankind a set of rules, and in discipline they must be obeyed. It behooves Me to say that My heart is torn by the actions, the despicable actions, of My clergy. I unite, as your God, man and woman into the holy state of matrimony. And what I have bound together no man must place asunder. And what do I see but broken homes, marriages dissolved through annulments! It has scandalized your nation, and it is scandalizing the world. Woe to the teachers and leaders who scandalize the sheep!”

A Catholic author named Kelly Bowring even speculated that the relatio signaled a the beginning of an prophesied end times scenario, writing:

Will today be remembered as the first day that led to the Church’s prophesied schism? Quite likely yes. By many accounts people are waking up to see that the Family Synod of October 2014 is an officially Vatican-orchestrated work of manipulation. The mid-way report was released October 13th, a day of great spiritual significance.

Like many apocalyptic Marian groups, Bowring has located the relatio within a “theology of history” by finding other significant dates that also occurred on 13 October. On 13 October 1884, Pope Leo XIII composed the prayer to Saint Michael. According to Catholic legend, he did so after a mystical experience in which he overheard a conversation between God and Satan in which Satan was given “time and power” so that he could attempt to overthrow the Church. The “Miracle of the Sun” in Fatima, Portugal occurred on 13 October 1917. The Marian apparitions at Fatima were the most significant in modern history and the three “secrets of Fatima” delivered by the child seers remain the object of intense speculation among traditionalist Catholics. Finally, on 13 October 1973, Sister Agnes Katsuko Sasagawa, a Marian seer near Akita, Japan, delivered a prophecy of a great schism that would destroy the Church. By forming these connections, Bowring can locate new developments like the relatio within a cosmic scheme of history.

These responses––from off-the-cuff remarks equating confusion with the devil, to intricate webs of numerical correspondences––can be read as attempts to make sense of what previously seemed unthinkable. For some, it is easy to dismiss such language as hysterical or even evidence of mental illness. But demonology, conspiracy, and millennial prophecies are all interpretive tools that can be brought to bear in times of crisis. For lay Catholics who feel helpless and betrayed as strangers in Rome attempt to shift the core values of their tradition, these are also discourses of resistance.

Critics of Veronica Lueken claimed she was either mad or a con artist. (One reporter even suggested that her visions were a side effect of diet pills.) But if we examine Catholic tradition as an asymmetric collaboration between lay Catholics and Church authorities, figures like Veronica Lueken are easier to understand. Marian seers do not simply pop up fully formed. Instead events like Church reform create an alignment of social forces in which seers arise. The relationship that forms between seers and their followers creates a charismatic authority that––in some cases––can rival the authority of the Catholic hierarchy. For this reason, it seems likely that as Pope Francis continues to voice his preference for social justice rather than tradition, we can expect a backlash that imbues reform with dark and apocalyptic significance. Like Paul VI, Francis will likely be a pope who gives rise to seers.

Featured image credit: “General Audience with Pope Francis” (2013) by Catholic Church England and Wales. © Mazur/catholicnews.org.uk. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Prophecy, demonology, and the Extraordinary Synod of Bishops on the Family appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs it really over for RG3? It’s too soon to tell.On the 50th anniversary of the premiere of Terry Riley’s In CCharting events in international security in 2013

Related StoriesIs it really over for RG3? It’s too soon to tell.On the 50th anniversary of the premiere of Terry Riley’s In CCharting events in international security in 2013

Is it really over for RG3? It’s too soon to tell.

In a recent article for Huffington Post, numberFire.com CEO Nik Bonaddio stated: “RG3: It’s Over”. Bonaddio is asserting that it is unlikely that Washington Redskins quarterback Robert Griffin III (RG3) will ever be able to return to the form that enabled him to win the 2012 Rookie of the Year Award and made him one of the best quarterbacks in the NFL that year. More specifically, Bonaddio claims, “The numbers are quite clear: no quarterback who suffered that bad of a precipitous fall in performance ever recovered.”

While Bonaddio may end up being proven correct, there are several problems with his analysis. More specifically, the numbers are not clear at all. Bonaddio starts with using his company’s Net Expected Points (NEP) metric that examines how many points a player’s team should score given his performance. He then states that only six QBs have ever had a drop in their NEP similar to RG3’s drop after his 2012 season. They are: Steve Beuerlein in 1999, Elvis Grbac in 2000, Jay Fiedler in 2001, Tommy Maddox in 2002, Derek Anderson in 2007, and David Garrard in 2007.

As far can be discerned from the information in the article, these are the only quarterbacks used by Bonaddio in his analysis. Having a sample size of six is a very small number to use in such an analysis. Furthermore, even this small sample has major problems when making a comparison to RG3. They are:

The average age for when each of the quarterbacks in the sample had their best years is 29.8 years old while RG3 was only 22 years old during his rookie year. Only Anderson, at age 24, was close to the age of RG3 in 2012 during his best season. Each of the quarterbacks had played in the NFL for at least one year before having their best season. Only Anderson had played in one season before his best year. The rest of the quarterbacks had played in multiple years before having their best years. None of the quarterbacks had a significant injury that could account for the subsequent decline in their performance. Each of the other quarterbacks had little mobility. RG3’s success, as stated by Bonaddio, is predicated on his ability to run the football. None of these quarterbacks was a Heisman Trophy winner or had the same level of success as RG3 did in college.At the end of the article, Bonaddio claims “Regardless of what the cause was [of the decline], the effect is obvious and it’s rather tragic.” The cause of RG3’s decline is extremely important, especially compared with these other six quarterbacks. For example, it is impossible to rule out that these six quarterbacks were never good, or at least as good as RG3. They had one good season in the midst of having many relatively mediocre or poor seasons.

In addition, an NFL quarterback’s prime is age 29 with his prime range being 26-30 according to Football Perspective. Again, the average age of the six quarterbacks is 29.8. Given his college and 2012 performances, RG3 could just be a more talented quarterback than any of these other players. Since he has not reached the prime age range in his career, RG3 could also continue to improve as he gets older and gains more experience.

There is also a clear reason for RG3’s decline: his injury history. Bonaddio does point out that RG3 did suffer significant injuries both during the 2012 and 2014 seasons that caused his NEP to decline. However, he does not fully account for the fact that RG3’s poor performances in 2013 and 2014 could be due to injuries and recovery from injuries rather than a decline in his skillset. It is definitely possible that RG3 may never recover his running ability from 2012 or that he is more injury prone than other NFL quarterbacks. However, it is impossible to know what RG3’s best performances can be until that can be proved to be the case or he has actually had played in more games where he has fully recovered from these injuries.

Bonaddio’s analysis does show the potential problem with working with advanced analytics in sports. The NEP could be a valuable metric that provides great insights about the true performance of quarterbacks. However, making assertions beyond the stated use of the metric that rely on small sample sizes with clear confounding variables can lead to problematic conclusions. It may or may not be over for RG3, but it is impossible to tell using the evidence presented in Bonaddio’s article.

Featured image credit: Robert Griffin III on a read-option run during the Redskins 24-16 loss to the Eagles in the 2013 season. Photo by Mr.schultz. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is it really over for RG3? It’s too soon to tell. appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnalyzing the advancement of sports analyticsDallas Cowboys: seven strategies that will guarantee a successful 2014 seasonA different kind of swindle

Related StoriesAnalyzing the advancement of sports analyticsDallas Cowboys: seven strategies that will guarantee a successful 2014 seasonA different kind of swindle

On the 50th anniversary of the premiere of Terry Riley’s In C

Last month marked the 50th anniversary of the premiere of Terry Riley’s In C. The date was 4 November 1964 at the San Francisco Tape Center. Having written a book on the topic, it’s a time of reflection for me as well. The piece continues to endure, and though only five years out, it becomes ever more clear that its inclusion in the OUP series Studies in Musical Genesis, Structure, and Interpretation was justified. In short, it’s a canonic work.

Happily, most of the participants in the event are still with us. In particular, Terry is celebrating his 80th next year, and such luminaries as Pauline Oliveros, Morton Subotnick, Steve Reich, Stuart Dempster, and Ramon Sender are still going strong. One of the great joys I experienced in the course of researching the book was to meet a group of composers about 20 years older than I who were not only still productive, but also not bitter. Their engagement with their work and purity of commitment was inspiring then, and continues to be.

By now minimalism is so ingrained in our era’s musical consciousness that it becomes ever harder to imagine what a break the piece represented. But it came over me recently in a different way, when listening to a new release on New World of the “TudorFest” that was organised in February 1964 by Oliveros. This was a series of concerts centered around David Tudor as both performer and general collaborative provacateur. The 3-CD set concentrates mostly on music of Cage (though there’s a great work for accordion and bandoneon by Oliveros, that she and Tudor perform on a multi-dimension seesaw—how I wish for a video!). Even though Cage’s ethos of experiment and freedom is obviously an inspiration to the circle that organized the event, it’s also clear just how different that sort of experimentalism was from what was about to erupt in the immediate future. Cage’s pieces, most from the 1950s, are amongst his most radical works, “atonal” in the purest sense for the word, and resolutely refusing any traditional form or teleology. Frankly, listening to several in a row, exhilarating as is their invention, they’re also tough.

For me this makes it clearer just how much the new music percolating under the surface in San Francisco wasn’t just about process or repetition, it was also about beauty (even if no one really wanted to use the word). Cage was a California boy, but he found his milieu in New York, with its intensity, rigor, and challenge. To take a counter-example, Lou Harrison, his early friend and collaborator, went there too, but he returned West and found himself in the pursuit of Asian sounds. I may be making too much of a dichotomy here, as there are many other factors involved in the making of a style and individual works therein. But the old trope of “mean old modernism” vs. minimalism is too pat; there was a generational shift at work as well. Cage was a beloved pioneer, but he wasn’t living the Haight life. The music that was about to resound in November had a new sensuality and freedom, in tune with the adventure, love, and sheer subversive fun that was erupting across the country.

Headline image credit: Music. CC0 via Pixabay

The post On the 50th anniversary of the premiere of Terry Riley’s In C appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCharting events in international security in 2013A different kind of swindleYes? Yeah….

Related StoriesCharting events in international security in 2013A different kind of swindleYes? Yeah….

What is psychology’s greatest achievement?

I am sure that there are some who still proclaim that psychology’s greatest achievement is buried somewhere in Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic papers, whereas others will reject the focus on early childhood memories in favor of present day Skinnerian contingencies of prediction and control. Still others might vote for a self-actualizing, Maslowian humanistic psychology, which has been more recently branded as positive psychology. Having studied in all three of these areas in my lifetime, I have found these models to be hopelessly individualistic and ecologically incomplete.

Regretfully, piecemeal and person-centered approaches have dominated these psychological world views, particularly when it comes to treatment and rehabilitation. For example, our massive investments in prisons has done little to protect us, but rather has stigmatized and victimized a generation of our most vulnerable citizens. Just think, hundreds of thousands of people are locked up for petty, non-violent crimes, often involving drug usage. Being warehoused in total institutions only serves to unwittingly teach prisoners how to become seasoned criminals. When inmates exit these desensitizing settings, they are given one-way tickets back to the networks, associates, and ineffective programs that often further cement hopelessness and demoralization. Formerly incarcerated individuals need safe housing and decent jobs, but are only provided dehumanizing shelters and dead end job training programs. As a consequence, most psychological models perpetuate programs that are expensive, ineffective, and fail to address the social environments that provide so few constructive opportunities or resources.

Drug overdose by Sam Metsfan (Apartment in New York). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Drug overdose by Sam Metsfan (Apartment in New York). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Our efforts to curb violence have had similarly disappointing outcomes. We know that adolescent violent behavior, for instance, is positively related to factors outside of the adolescent, such as peer behavior, family conflict, and exposure to community violence. Our youth are exposed to media saturated with violence, where negative consequences for aggressive behavior are rarely depicted. The ready availability of guns further fuels an erosion in the social fabric of neighborhoods. A tipping point arrives when schools with the greatest needs are provided the fewest resources and where illegal gang activities provide the best job prospects. And yet our therapeutic models continue to ignore these contextual barriers and risks, and the failure to embrace more preventive frameworks dooms our efforts to control or eradicate crime and violence.

Psychological models that attempt to eliminate deficits and problems for individuals rarely address the causes that contribute to those problems. Such models often only produce cosmetic change that provides, at best, short-term solutions. These interventions are alluring because they promise to solve the most deeply-rooted problems with simple solutions, yet they fail at the most basic levels due to ignoring the “elephant in the room” of racism, neighborhood disintegration, and poverty. Such interventions can render people powerless to overcome their oppression or unable to break out of a cycle of crime or addiction.

Fifty years ago, the field of community psychology emerged out of a comparable crisis in the 1960s, a time of turmoil involving the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement. Although not well known among the public, community psychology’s vital ecological model provides a far richer framework for solving our nation’s problems than those involving psychoanalytic, behavioral, or positive psychology. This new field offers the powerful message of prevention as an effort to move beyond attempts to treat each affected individual. The field also promotes collaboration, actively involving citizens as true partners in efforts to design and implement community-based interventions. This discipline further rejects simplistic linear cause and effect ways of understanding social problems and instead adopts a more elegant, complex, systems approach that seeks to understand how individuals affect and are influenced by their social environments. In other words, community psychology provides a unique framework from which to examine contextual influences that have been absent from prior models dominated by thinking of problems as resting solely within individuals. As a field, community psychology is a contribution that stirs the imagination by charting a course that can provide structural, comprehensive, and effective solutions to our most pressing problems.

Heading image: Prison fence by jodylehigh. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post What is psychology’s greatest achievement? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnna Freud’s lifeDo you have what it takes to be extreme? [quiz]Leonard Cohen and smoking in old age

Related StoriesAnna Freud’s lifeDo you have what it takes to be extreme? [quiz]Leonard Cohen and smoking in old age

Charting events in international security in 2013

The world today is a very complex place. Events such as the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, the devastating conflict erupting in Syria, and the often-fraught relations between the world’s superpowers highlight an intricate and interconnecting web of international relations and national interests. The SIPRI Yearbook, published every year, keeps track of these global developments around issues of security, and analyses the data and implications behind the headlines you’ve been reading in the past year – from conflicts and armaments to peace negotiations and treaties.

Did you know, for example, that in 2013, the Arms Trade Treaty was opened for signature in the UN HQ in New York City? This treaty, when it comes into force, will roll out international arms regulation for trading in arms, and prohibit the sale of any arms by a state party which will be used in genocide or crimes against humanity. Or that throughout 2013 the Democratic Republic of Congo, combined with international assistance, made considerable gains in stabilizing troubled regions of the country, bringing the state one step closer to security and safety?

With snippets taken from the SIPRI Yearbook 2014, which analyses significant events across the globe in the previous year, the map below helps you explore the global state of affairs, as they happened in 2013:

Headline image credit: Two destroyed tanks in front of a mosque in Azaz, Syria after the 2012 Battle of Azaz. Photo by Christian Triebert. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Charting events in international security in 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLooking beyond the Scottish referendumA different kind of swindleIs your commute normal?

Related StoriesLooking beyond the Scottish referendumA different kind of swindleIs your commute normal?

December 3, 2014

Anna Freud’s life

In celebration of what would have been Anna Freud’s 119th birthday, we have put together a timeline of important events, her influences and her most celebrated publications. From her education and love of learning, to her role as a teacher, children and child psychoanalysis always played a large part in the life of Anna Freud. Her strong relationship with her father only added to her interest in psychoanalysis, and her research is still held in extremely high regard today. You can check out the timeline of her life below or learn more about Anna Freud’s life in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

If you think we’ve missed a key part of Anna Freud’s life, we’d love to hear from you in the comment section below.

Headline image credit: Rorschach inkblot test, by Hermann Rorschach. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Anna Freud’s life appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs your commute normal?Do you have what it takes to be extreme? [quiz]How has World War I impacted United States immigration trends?

Related StoriesIs your commute normal?Do you have what it takes to be extreme? [quiz]How has World War I impacted United States immigration trends?

Yes? Yeah….

Two weeks ago, I discussed the troubled origin of the word aye “yes,” as in the ayes have it, and promised to return to this word in connection with some other formulas of affirmation. The main of them is yes. We may ignore the fanciful suggestions that connected yes with the imperative of Old Engl. agan, the etymon of Modern Engl. own (Horne Tooke derived hundreds of English words from imperatives), or from Irish Gaelic (tracing the bulk of the English vocabulary to Gaelic was John Mackay’s hobby). Etymology has always attracted more or less peaceful maniacs, and they usually had the same tempting idea, namely that all words of all languages have a single source or go back to a small number of monosyllabic roots.

The word gese (with g pronounced as y) has existed since the days of Old English. Noah Webster knew it but said nothing about its origin. Later etymologists did not doubt that gese is a combination of ge and se, with ge being preserved in the modern word yea and cognate with Dutch and German ja, Old Norse já, and Gothic ja ~ jai. The s-part remains in limbo. It may be the stump of swa “so” or of sie, the present subjunctive of the Old English verb to be. Thus, “yea so” or “yea, be it.” Some dictionaries favor the first variant, others the second. The most circumspect ones sit on the fence, and we will join them there.

Words meaning “yes” often go back to demonstrative pronouns; such are, for instance, Slavic da and Romance si. They tend to be short and to have multiple variants. Even Biblical Gothic, the only extant version of that fourth-century Germanic language, had, as we have seen, ja and jai. The Old Celtic and Germanic forms sounded nearly the same and were related: neither Germanic borrowed them from Celtic nor Celtic from Germanic. Perhaps, as etymological dictionaries say, Proto-Germanic had both ja and je, but there could be more. Only crumbs of old slang and conversational usage have come down to us. The hardest question about their history is just variation, so typical of emphatic words and interjections. English has retained its oldest word for “yes” in the form spelled as yea, but it rhymes with nay and may owe its pronunciation to the Scandinavian borrowing nay (the negation ne + ey “ay”).

Will you marry me? YES!

Will you marry me? YES! As mentioned in the older post, language historians tried but failed to derive aye from yea because the vowels do not match and aye has no y-. The second difficulty can perhaps be explained away. For no known reason, initial y- sometimes disappeared in English words. The oldest form of if was gif (pronounced as yif). Likewise, itch began with g- (= y): compare Dutch jeuken and German jucken. Less clear is the history of -ickle (Old Engl. gicel) in icicle. Its cognate is Icelandic jökull “glacier”; in the middle of a compound, the argument goes, j could be lost without anybody’s noticing it. This also happened in some Scandinavian languages. But as though to mock us, in one case Old Norse preserved initial j- in the position in which it was supposed to lose it. Compare German Jahr “year” and Icelandic ár. This is a regular correspondence: initial j has been dropped before a vowel. However, já has not become á.

Having disposed of j-, we wonder what to do with the vowels. Let me repeat: a word for yes or yes indeed occurred as an emphatic formula of affirmation, and a good deal in its life cycle depended on the rise and fall of the speaker’s voice. Wilhelm Horn, an outstanding German scholar (1876-1952), based many of his historical hypotheses on the caprices of intonation. In this he had few followers, for the intonation of past epochs is nearly impossible to reconstruct, but his opinions are worth knowing.

Both professionals and lay people have paid attention to the forms of yea in British dialects and especially American English. We find yeah approximately with a diphthong as in ear, yah (known from Lancashire to North America), eh-yuh (pronounced as ei-ya), and ayuh, the latter recorded in Maine and elsewhere in New England. Languages are most inventive when it comes to coining expressive words. For instance, the Swedish for “yes” is ja, but, to disagree with a negative statement, one says ju (“he won’t come”—“oh, yes, he will” [Ju!]); analogs of the ja ~ ju difference exist elsewhere in the Scandinavian area. The Russian for “already” is uzhe. This word, when it acquires threatening connotations, sounds as uzho (stress falls on the final syllables). Similar, often inexplicable, changes happen in humorous variants, as in Engl. brolly for umbrella and frosh for freshman.

We should not underrate the so-called ludic function of language: people like to play, and wordplay is among the greatest amusements there is. Could aye, a homophone of I, come into being as an emphatic variant of yea in contexts like: “You will do it, won’t you?”—“I, I!” (not a new idea)? That we will never know, but etymologists, predictably, shy away from vague suggestions, to save themselves from wild conjectures; however, such a possibility cannot be excluded. But one loses heart after discovering that the Korean for “yes” is also ye. Are we dealing with some near-universal interjection of assent?

As long as we are on the subject of emphasis, it may be useful to remember yep and nope (mainly but not exclusively American). The obvious things about them have been said more than once. While pronouncing such words, we are told, people sometimes articulate sounds very forcefully, that is, they close the mouth so energetically that some sort of final p is heard. This is not much of an explanation, but there is no better one. Scandinavian scholars, including the greatest among them (Axel Kock, Marius Kristensen, and Otto Jespersen) were especially intrigued by yep and nope, because Danish makes wide use of the so-called glottal stop, but even they were unable to come up with a more profound explanation. The fact that a Swiss German interjection once also ended in p does not take us much further.

Aye, aye, Sir.

Aye, aye, Sir. As was noted in the post on aye, this English word has a Frisian congener sounding exactly as in English, but I expressed some doubt about the borrowing of it from Frisian. Also, I cited the opinion that aye could come to English from nautical usage, as suggested by the formula “Aye, aye, Sir,” and referred to two researchers: Hermann Flasdieck and Rolf Bremmer. My half-baked reconstruction resolves itself into the following. Among the rather numerous variants of the word yeah, the variant aye (that is, i or I) developed among British sailors and became part of international nautical slang. Later, landlubbers in Frisia and Britain began to use it too. This process must have taken place some time before 1500; Bremmer’s earliest Frisian citation dates back to 1507.

By way of conclusion, I’ll again cite an example from Slavic. The Russian for “aye, aye, Sir” is est’! (a homonym of the third person singular of the verb to be: Engl. is, German ist, Latin est, and so forth). It has been suggested that this est’! is a slightly modified borrowing of Engl. yes, Sir. This etymology has been contested, but, if it is true, we have a curious example of the spread of nautical formulas in northern Europe. Russian est’! is not limited to the language of sailors.

Image credits: (1) The Proposal by Giacomo Mantegazza. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) U.S. Navy Ensign Michael O’Connor receives his first salute from Electronics Technician 1st Class Eric Walden April 30, 2010, in Tallahassee, Fla. U.S. Navy photo by Scott Thornbloom/Released via United States Navy Flickr.

The post Yes? Yeah…. appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe ayes have itMonthly etymology gleanings for November 2014On idioms in general and on “God’s-Acre” in particular

Related StoriesThe ayes have itMonthly etymology gleanings for November 2014On idioms in general and on “God’s-Acre” in particular

How Malcolm X’s visit to the Oxford Union is relevant today

Fifty years ago today, a most unlikely figure was called to speak at the Oxford Union Debating Society: Mr. Malcolm X. The Union, with its historic chamber modeled on the House of Commons, was the political training ground for the scions of the British establishment. Malcolm X, by contrast, had become a global icon of black militancy, with a reputation as a dangerous Black Muslim. The visit seemed something of an awkward pairing. Malcolm X encountered a hotel receptionist who tried to make him write his name in full in the guest book (she had never heard of him), sat through a bow tie silver service dinner ahead of the debate, and had to listen to a conservative debating opponent accuse him of being a racist on a par with the Prime Minister of South Africa. A closer look at the event, though, reveals the pairing of Malcolm X and the Oxford Union to be a good fit — and reveals much about the issues of race and rights then, and now.

From the perspective of the Oxford Union, a controversial speaker was an entirely good thing. The BBC covered Malcolm X’s costs and broadcast the debate. In late 1964, though, Malcolm X also spoke to student concerns about race equality. For many years, the British media’s (sympathetic) coverage of anti-racist protests in the American South and South Africa gave the impression that racial discrimination was chiefly to be found elsewhere. A bitter election which turned on anti-immigration sentiment in late 1964 in Smethwick, in the English midlands, with its infamous slogan, “If you want a n***** for you neighbour, vote Labour,” exposed the virulence of the race issue in Britain, too. Students followed this news abroad and at home. Some visited “racial hotspots” in person. Others joined demonstrations in solidarity. Still, on the surface, such issues seemed a world away from Oxford’s dreaming spires.

But some students in Oxford were also grappling with the question of race in their own institution. The Union President, Eric Antony Abrahams, was a Jamaican Rhodes Scholar, who had vowed to his sister in his first week that he would “fill the Union chamber with blacks.” Abrahams was part of a growing cohort of students from newly independent nations who studied in Britain, many of whom called for changes in curriculum and representation. Three days before Malcolm X arrived, Oxford students released a report showing that more than half of University landladies in the city refused to accept students of color. The University had an official policy of non-discrimination, but the fact that many landladies turned down black applicants in practice had been a running sore for years. The report, and Malcolm X’s visit, brought the matter to public attention. Student activism ultimately forced a change in practice, part of a nationwide series of protests against the unofficial color-bar in many British lodgings. At a time when Ferguson is rightly at the forefront of the news, events in Oxford in 1964 remind us that atrocities elsewhere should serve as a prompt to address, rather than a reason to ignore, questions of rights and representation nearer to home.

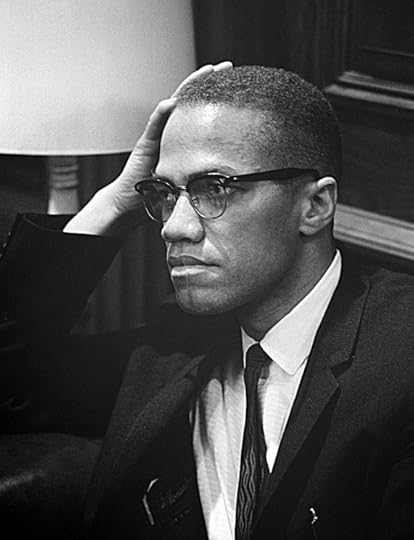

Malcolm X waiting for a press conference to begin on 26 March 1964. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Malcolm X waiting for a press conference to begin on 26 March 1964. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. For Malcolm X, coming to Oxford was an exciting challenge. He loved pitting his wits against the brightest and the best. As chance would have it, as Prisoner 22843 in the Norfolk Penal Colony in Massachusetts, he may well have debated against a visiting team from Oxford. More germane, though, was Malcolm’s desire in what turned out to be the final year of his life to place the black freedom struggle in America within the global context of human rights. He had spent the better part of 1964 in the Middle East and Africa. In each stop along his dizzying itinerary of states, he attempted to build support for international opposition to racial discrimination in America. Malcolm’s visits to Europe in late 1964 were no different. But it was Oxford that afforded him the opportunity to broadcast his views before his widest single audience yet. Citing the recent murders of civil rights activists in Mississippi, Malcolm X told his audience: “In that country, where I am from, still our lives are not worth two cents.”

At a time when cities across the United States have recently braced themselves against the threat of rebellion in the aftermath of the acquittal of Michael Brown’s killer, it is hard not to conclude that for many African Americans, Malcolm’s words at Oxford continue to haunt the nation. Indeed, by placing the civil rights movement in broad relief internationally, Malcolm sought to link the fate of African Americans with West Indians, Pakistanis, West Africans, Indians, and others, seeking their own justice in the capitals and banlieus of Europe. Emphasizing the independence of this new emergent world both within and outside of the confines of Europe, Malcolm hoped that the “time of revolution” his audience was living in would in part be defined by a broader sense of what it meant to be human. There could no longer be distinctions between “black” and “white” deaths — despite his condemnation of the media for continuing to indulge such distinctions.

The post How Malcolm X’s visit to the Oxford Union is relevant today appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat we’re thankful forThanksgiving with Benjamin FranklinLooking beyond the Scottish referendum

Related StoriesWhat we’re thankful forThanksgiving with Benjamin FranklinLooking beyond the Scottish referendum

Is your commute normal?

Ever wonder how Americans are getting to work? In this short video, Andrew Beveridge, Co-Founder and CEO of census data mapping program Social Explorer, discusses the demographics of American commuting patterns for workers ages sixteen and above.

Using census survey data from the past five years, Social Explorer allows you to explore different categories of American demographics through time. Here, Beveridge walks viewers through the functionality of the “Transportation” category, revealing the hard truth of Americans’ car dependency, as well as the true scope of the bike-to-work trend gaining speed across college towns and urban areas. Want to see how your travel time stacks up to the rest of the population’s workers? Use the “Travel Time to Work” category to explore other American commuting trends, or explore the various additional categories and surveys Social Explorer has to offer.

Whether it is the speed, assumed efficiency and control, or the status-marker of the automobile that makes it so ubiquitous, the numbers don’t lie – for most Americans, “going green” may be only secondary to “catching green” (lights, that is).

Featured image credit: Charles O’Rear, 1941-, Photographer (NARA record: 3403717) (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Is your commute normal? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow has World War I impacted United States immigration trends?Income inequality in the United States

Related StoriesHow has World War I impacted United States immigration trends?Income inequality in the United States

A different kind of swindle

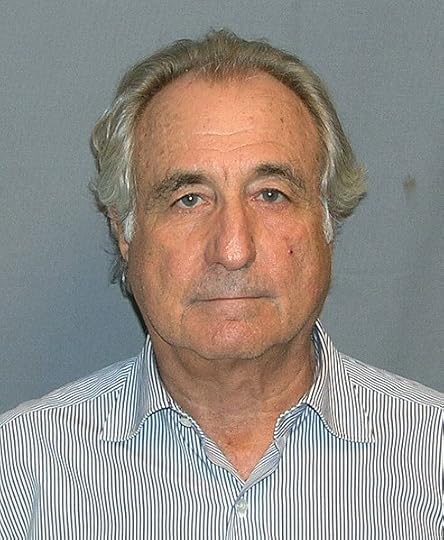

In the weeks and months following the subprime crisis, a number of financial swindles have come to light. Perhaps the most famous of these was the Bernie Madoff scandal.

Madoff ran a Ponzi scheme, in which he attracted money from individuals (and institutions) who were hoping that he would provide sound investment management and a healthy return on the funds entrusted to him. Instead, the money ended up in his pocket. The small number of “investors” who did withdraw their funds from Madoff were paid with money from new investors. Because the financial markets were booming at the time, there was a steady flow of funds into Madoff’s coffers and his scheme was not discovered.

The problem with all such swindles is that when the financial boom ends, more and more investors want to withdraw their money while few if any new investors are willing to provide funds, so veteran investors making withdrawals cannot be paid. This is what happened to Madoff, who is now serving a 150-year sentence for a variety of financial frauds.

As tragic as the Madoff scandal was for his victims, it pales in economic significance next to two far less heralded episodes: the Libor scandal, which emerged in 2012, and the foreign exchange (forex) scandal, in which six banks were fined a total of $4.3 billion by regulators in Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States last month. Because I have written quite a bit about Libor, this post will focus on the forex scandal.

In 2013 the Bank for International Settlements estimated the daily turnover in the foreign exchange market at $5.3 trillion. Because so much money flows through the foreign exchange market, even small changes in the prices of foreign currency can mean huge profits or losses for market participants.

Bernard Madoff, by United States Department of Justice. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Bernard Madoff, by United States Department of Justice. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. The banks were fined because the authorities found that they rigged the forex market in two ways: (1) by colluding to manipulate the daily “fix”; and (2) by intentionally triggering their client’s stop-loss orders in order to manipulate the price.

The daily “fix” refers to the WM/Reuters benchmark rates, which are calculated by taking the median of actual buy and sell transactions that take place in the 61 seconds between 3:59:30 and 4:00:30 pm London time (the European Central Bank also produces a fix two hours and 45 minutes earlier). These benchmarks are widely used, according to a Bank of England report “…in valuing, transferring and rebalancing multicurrency asset portfolios.” Small movements in the daily fix can therefore have a large impact on the value of asset portfolios—and on the wallets of the traders and their employers. This type of manipulation is reminiscent of the Libor scandal, in which a few traders fiddled with a widely used interest rate benchmark in order to make large trading profits.

Stop-loss orders are instructions placed by clients with their bank to buy or sell a currency when the price hits a specified rate. Clients do this if they are concerned that a large price movement will have an adverse impact on their bottom line: in such a case, a stop-loss order will, well, stop the loss. Traders were found to have manipulated currency prices just enough to trigger clients’ stop-loss orders and move the market for their own benefit.

The Libor and forex scandals have several especially troubling aspects in common. First, unlike Madoff, they did not require asset booms in order to succeed: profits could be made on days when a particular currency rose or fell. That is, no prolonged asset bubble was required for forex manipulation to succeed—nor would the scheme collapse if an asset bubble collapsed. In theory, forex manipulation could have continued indefinitely.

Second, unlike Madoff, who only required his own wits and the gullibility of investors to succeed, the forex scandal was a conspiracy—or rather a series of conspiracies. The efficient operation of all markets—foreign currency included—requires the active participation of large numbers of individuals and institutions. When those participants believe that the market is rigged, they will try to withdraw from those markets. Of course, it would be hard for any major multinational company to completely withdraw from the $5.3 billion foreign exchange market, but it is not inconceivable that they might attempt to find alternative mechanisms for dealing in foreign exchange.

Finally, the forex scandal is especially troubling because it persisted for more than two years after the Libor scandal was exposed. How did the discovery that one hugely important benchmark rate was being manipulated to profit a small group of individuals not lead to a greater scrutiny of other markets?

What other important prices—those set by the London Metals Exchange come to mind—are determined by a small number of traders whose interests might not align with ours? It is time for our governments and financial regulators to be proactive and stop the next episode of manipulation before it happens.

Featured image credit: Foreign money conversion, by McZusatz. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A different kind of swindle appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returnsI miss IntradeThe economics of Scottish Independence

Related StoriesA new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returnsI miss IntradeThe economics of Scottish Independence

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers