Oxford University Press's Blog, page 725

December 14, 2014

Parenting during the holidays

The holiday season can be an insanely stressful time. Looking for presents, wrapping them, cooking, getting the house ready for visitors, cleaning before and after. Nothing like a normal Saturday night on the couch in front of the TV or with a couple of close friends. The holidays demand perfection. You see it all around you, friends are talking about how stressed out they are, how much they still have to do in just a couple of days. Hyper-decorated stores are talking in their own way. As you approach the 25th of December you still haven’t bought half the gifts you need to rack up for family members, the house looks like a bomb crater and you occasionally wish yourself back in the office with piles of work on your desk waiting to be completed. There are even times when you would exchange a chilly Monday morning and an 8 o’clock meeting for this nerve-racking time that’s supposed to be happy, fun and merry.

What many rattled folks forget in the midst of buying last-minute bequests for loved ones or checking on the unhappy-looking beast in the oven minutes before guests arrive, wishing themselves far away, is that as many as half of the population face a holiday season without their dearest family members. There are people who have lost their loved ones in gruesome ways. I can’t even begin to imagine how they must feel, as they approach every new upcoming holiday season. There are people who have lost their parents to old age, people who have gone through heartbreaking divorces, separations and breakups and people who are overseas defending their country because they have no other choice. The holidays will not be what they once were for any of them. And then there are the single parents, parents many of which have decent custody agreements that are “in the best interest of the children.” According to the US Census Bureau, there are more than 10 million single parents in the United States today. Each year millions among them can look forward to days of loneliness because the little ones they really want to spend time with are with the other parent.

When sane parents separate, many judges, thankfully, divide custody equally. Each parent gets his or her fair share of custody, if at all possible. Even when it’s not possible to share the time with the children equally, judges will usually attempt to divide up the holidays evenly. The kids spend every other holiday with mom and every other holiday with dad. It certainly is in the children’s best interest to get to spend some time with each parent. Most kids, with decent moms and dads, would prefer to spend every holiday with both parents. The precious little ones secretly hope for the impossible: That their divorced or separated parents will get back together. But despite their wishes, they adjust to the situation. They have no other choice.

The array of Christmas presents, by SheepGuardingLlama. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

The array of Christmas presents, by SheepGuardingLlama. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr. Nor do the parents. As we face the holidays many single parents face a very lonely time. They may be with dear family members: parents, brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews, aunts and uncles. Yet they may nonetheless feel a profound pain in their hearts, even as they watch close relatives savor the pecan pie or scream in delight when they rip open their Christmas presents. Their own children are far away. In most cases the youngsters are in a safe place elsewhere, stuffing their faces with goodies or breaking out laughing when the other grandpa makes a funny face. In most cases single parents know that their children are enjoying themselves in the company of the other caregiver and his or her extended family.

Yet the children are missing from the scenery. Their absence is felt. “It hurts. It hurts every other Christmas when my kids are with their dad during the holidays,” says Wendy Thomas, a St. Louis, Missouri single mother of two girls ages 8 and 5. Thomas shares custody with the girls’ father, who lives in Illinois. “The first year was the hardest but I don’t think I will ever get used to it. Shopping malls and Silent Night make me shiver,” says the 38-year-old entrepreneur. This is her third Christmas and New Year’s without her children.

Each holiday a single parent truly misses his or her children on that one day that is supposed to bring delight to everyone. “It’s going to be a lonely, lonely Christmas without you” may just be tedious background music for the families that didn’t break apart. Each year, however, the oldie is causing a tiny tear to run quietly down the cheek of some single caregiver.

But could some of the reported agony over absent children during the holidays be the result of what psychologists call cognitive dissonance, a psychological mechanism we use to justify our choices and conflicting belief sets? For example, you choose to volunteer three hours a week at the local children’s hospital. It’s killing you. You can barely fit in everything else you have to do. But you tell everyone, including yourself, that volunteer work is truly rewarding and every (wo)man’s duty. Making irrational decisions seem rational is a way to preserve your sense of self worth.

Studies show that the hardship involved in raising children makes us idealize parenthood and consider it an enormously rewarding enterprise. In a study published in the January 2011 issue of the journal Psychological Science researchers primed 80 parents with at least one child in two different ways. One group was asked to read a document reporting the costs of raising a child. The other parents read the same document as well as a script reporting on the benefits of having raised children when you reach old age. The participants were then given a psychological test assessing their beliefs about parenting. The team found what they expected. Parents who had only read about the financial costs of parenthood initially felt more discomfort than the other group. But they went onto idealize parenthood much more than the other participants and when interviewed later their negative feelings were gone.

“How do single parents get through Christmas as painlessly as possible?”

Could cognitive dissonance explain why single parents feel empty-handed and depressed during holiday seasons without their children? St. Charles, MO, family counselor Deborah Miller doesn’t think that’s what’s going on. “This year it’s my turn to be one of those parents. I’ll be the first to admit that raising a child is not always a blessing. There are countless times when I feel more like a chauffeur or a waitress or a slave than a free agent with some real me-time.” She thinks the lonely-parent phenomenon evidently is not a manifestation of cognitive dissonance, as we don’t idealize away the pain of being without our children on Christmas or New Year’s. The heartache often doesn’t go away until we see our kids again in January and abruptly remember just how draining it is to raise a child. “I’ll finally get some time to myself, and I know my son will have a blast. But I’ll miss him immensely,” says Miller.

How do single parents get through Christmas as painlessly as possible? The solution is not necessarily to have a huge family gathering with your side of the family to ease the sorrow. A gala dinner on Christmas Day may have its advantages. You can hug your little nieces and nephews and maybe feel a bit of comfort as they open their presents in a way only children can approach surprises. You may feel a teensy bit of wonder (or is it jealousy) as you view your siblings and their spouses exchange loving smiles and their young ones take delight in the simplest of things. “It may work for some but there is a sense in which you will only be a spectator,” says Miller. She recalls her Christmas two years ago. “I felt gratified to be part of a functional family, and it was good to see my siblings interact with their children. I also remember being thankful that my parents were still alive and healthy and that they got one more holiday season with some of their grandchildren. But I also felt great sadness, because the dearest thing in my life wasn’t with me. I really missed my son that day.” This Christmas, Miller is getting together with a few friends. “Sure, we will still have Christmas dinner but there won’t be any children or presents or sacred family traditions. So hopefully I won’t be reminded of what I’m missing out on.”

Featured image credit: Christmas Decorations, by Ian Wilson. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Parenting during the holidays appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTop 10 Turkey-Dumping Day breakup songsA perfume for lonelinessHoliday traditions from around the world

Related StoriesTop 10 Turkey-Dumping Day breakup songsA perfume for lonelinessHoliday traditions from around the world

December 13, 2014

Ebola: the epidemic’s next phase

Although the number of Ebola cases and deaths has jumped dramatically in the short time since we wrote our December Briefing on the epidemic, there are signs of hope. Ebola is slowing down in areas where there was previously high transmission, in Liberia and in Eastern Sierra Leone for example. The lesson from past Ebola epidemics is that learning and local adaptation has played a central role in controlling previous outbreaks; now in West Africa the curve of the epidemic seems to be turning as people alter their behaviour. The apparent avoidance of continued exponential growth is a relief but it is no cause for complacency.

Freetown and the North of Sierra Leone are still suffering heavily. There is likely to be ongoing transmission for some time with sporadic clusters of cases as the epidemic moves into its next phase. The message, that local people should be involved and that their perspectives and knowledge are both valid and valuable, is still essential. Now is the time to find a balance between medical interventions, emergency thinking, and more humane and localised approaches based on collaboration.

As and when the epidemic ends, there should also be no complacency about the structural violence which produced this crisis. Structural violence refers to the way institutions and practices inflict avoidable harm by impairing basic human needs. The long term view — which locates this epidemic in the context of economic, social, technical, discursive and political exclusions and injustices — needs to be at the forefront of recovery and ‘development’ post-Ebola. The stark evidence of violence, in the form of distrust, the collapse of already dysfunctional health services, the catastrophic costs of Ebola on families and countries, the unpaid salaries of nurses and burial teams, the lack of protection – whether in the form of plastic gloves or welfare nets in times of crisis – must not fade with a return to business as usual. The Ebola crisis should be a game-changer for development.

In pointing to structural violence, we aren’t talking of a single social institution, but of overlapping institutions and practices that have produced interlocking inequalities, unsustainabilities, and insecurities. Aid and development have failed to address these conditions. Sierra Leone and Liberia attract considerable foreign direct investment and record some of the world’s highest growth figures yet most of their populations live in continued or worsening poverty. The emerging field of global health emphasizes networks and shared vulnerabilities, but in practice — through disjointed programmes and a tendency towards ‘quick wins’ — has neglected dire inequalities, which mean a virus like Ebola can tear a country up due to an absence of the most fundamental public health and state capacities. These structural and related socio-cultural conditions are not quickly or easily addressed, but Ebola has highlighted how vast disparities, internationally and within countries, are not sustainable. A greater focus on inclusive institutions and economies, and on conceiving of health as a global public good, is needed in order to build trust and resilience. Achieving that will involve asking difficult questions about aid and development as practiced in this region.

Both the crisis response and efforts to address its structural underpinnings are strengthened by recognition of the complex and historically-embedded logics and relationships which shape people’s lives. The Ebola Response Anthropology Platform has been set up to network anthropologists and other social scientists across the world with fieldworkers and communities, and to provide an interface with those planning and implementing the Ebola response so that such perspectives can be integrated into the response. Complementary initiatives, like one supported by the American Anthropological Association, mean that there is now a groundswell of debate and commentary on these critical dimensions. Much of this is building on research conducted over decades of post-colonial development and post-conflict reconstruction that, with the benefit of hindsight, is revealing of the fault-lines of the Ebola epidemic. As ‘the response’ transitions into another phase of reconstruction it is critical that these lessons, and the complexities they reveal, are fully appreciated to prevent further disasters for this region.

Headline image credit: Conakry, Guinea, 2011. Photo by CDC Global. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ebola: the epidemic’s next phase appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIt’s not just about treating the cancerGlobal solidarity and Cuba’s response to the Ebola outbreakLessons from the heart: listening after Ebola

Related StoriesIt’s not just about treating the cancerGlobal solidarity and Cuba’s response to the Ebola outbreakLessons from the heart: listening after Ebola

The advantage of ‘trans’

In the late 1990s, I attended a conference focused on “those who identify at the male end of the gender spectrum.” At the end of the conference, organizers asked each participant to fill out an exit poll, intended to capture demographic information about conference attendees. In addition to the usual geographic/age-related questions, organizers asked about gender identity, and included a checkbox for every term they had ever heard used as a self-descriptor by members of this community. The list included: transdike, transdyke, transexion, transsexual, transgender, transie, transindividual, transmale, translesbigay, transnatural, transman, transguy, tranz-fag, trannyfag, MTM (man to male), FTM, trannyboy, tranzboy, boi, transboi, tranzsissy, transsissy, sissyboi, transmasculine, dragboi, transperson, transhuman, transqueer. And below these check boxes was a box that said, “Other,” and a line to write in a term.

Despite its length, the above list is not fully inclusive; people are always adding to it. This is a population of people trying to morph English in ways that allow them to describe their experience of gender to others. If English is your first language, you grew up in a culture that recognizes two genders, male and female, believing them to be fixed reality and determined at birth. “It’s a boy!” or “It’s a girl!” are often the first words an emerging infant hears upon being born. Yet, this statement isn’t always true; sometimes, that baby grows up defying that birth pronouncement, revisiting that gender assignment.

Transgender flag, San Francisco. By torbakhopper CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Transgender flag, San Francisco. By torbakhopper CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Re-examining gender

With only two words to choose from, man or woman, boy or girl, those who re-examine gender find themselves bumping up against the limitations of English. How can two words begin to capture the experience of the complex social process we call gender? Those redefining gender for themselves expand the lexicon far beyond two words, such that it becomes clear there is no consensus at all on terminology. For instance, some happily call themselves transsexual, noting they did change the sex of their body and this feels the most descriptive to them; others recoil in horror at the idea, exclaiming, “How can you use that term, it’s so medical model and pathologizing!”

Note how many of the above terms include the prefix trans. In the interest of pragmatic inclusivity, the shorthand term trans has become part of the community lexicon. A newer term still is trans*, reinforcing the idea that there are multiple possible endings to follow trans. Even there, consensus isn’t possible. Some view trans and trans* as two different populations of people – trans is viewed as the umbrella term for those who undertake some form of physical transition, while those who are trans* are in a middle-ground of gender that doesn’t pursue physical body modification. Others view trans as a fluid, deliberately-vague term that stands on its own, much like the term queer; the term trans* makes more clear that there are multiple identities under consideration, that one should then ask, “What does your * stand for?”

The ever-changing lexicon of gender identity

When a community lacks consensus on its own terminology, it becomes difficult for allies to understand just what terminology is acceptable and what isn’t. What about words that have historically been used in a pejorative sense, such as tranny? A rule of thumb applies to all such words (queer among gay/lesbian people, nigger among African-Americans) — if an ally is asking, “Can I use that word, really?” then the word is not fully reclaimed yet, and should be avoided by allies. It still retains vestiges of its former negative connotation. If it were fully reclaimed, its former negative connotation would be forgotten, as if it were a new word being invented and used for the first time. An ally would not then wonder, “Can I use that word, really?”

Trans is not a reclaimed word; it is invented terminology without the baggage of historically-pejorative words such as tranny. As such, it is fine for an ally to use the word trans, in any context. But, that’s just my interpretation of the emerging trans lexicon; ask another trans person, and you may get a completely different opinion. The important thing for allies to remember is, none of us is right, or wrong, none of us has ownership over the vocabulary of our people. Respectful intention is what makes an ally an ally; precise use of vocabulary isn’t possible in the ever-changing lexicon of gender identity.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Headline image credit: Group of people. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The advantage of ‘trans’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe victory of “misgender” – why it’s not a bad wordThe Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is…vapeBattels and subfusc: the language of Oxford

Related StoriesThe victory of “misgender” – why it’s not a bad wordThe Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is…vapeBattels and subfusc: the language of Oxford

Moses the liberator: Exodus politics from Eusebius to Martin Luther King Jr.

Moses and Pharaoh are returning to the big screen in Ridley Scott’s seasonal blockbuster, Exodus: Gods and Kings. With a $200m budget and Christian Bale in the leading role, the British director will hope to replicate the success of Gladiator (where he resurrected the sword and sandals genre) and surpass the shock and awe of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. Even before its release, the movie sparked controversy. The casting of white actors as Egyptians provoked charges of racial discrimination; describing Moses as ‘barbaric’ and ‘schizophrenic’ did not endear the leading actor to traditional believers; and casting a truculent young boy as the voice of Yahweh was bound to raise eyebrows. In other respects, the storyline remains traditional. Indeed, the film follows a long tradition of interpretation by presenting the Exodus as a political saga of slavery and liberation. 600,000 slaves are delivered as an oppressive empire is overwhelmed by divine power.

This political reading of the biblical epic will be familiar to anyone who has studied its remarkable reception history. In Christian preaching, liturgy and hymnology, Exodus has been read as spiritual typology — Israel points forward to the Church, Pharaoh’s Egypt to enslavement by Satan, Moses to the Messiah, the Red Sea to salvation, the Wilderness Wanderings to earthly pilgrimage, the Promised Land to heavenly rest.

Yet there has been an almost equally potent tradition of reading Exodus politically. It originated with Eusebius of Caesarea in the fourth century, who hailed the Emperor Constantine as a Mosaic deliverer of the persecuted Church. It took on new intensity when the Protestant Reformation was promoted as liberation from ‘popish bondage’. As a vulnerable minority, European Calvinists identified with the oppressed children of Israel in Egypt and then celebrated national reformations in Britain and the Netherlands as a new exodus. The title page of the Geneva Bible (1560) pictured the Israelites pinned against the Red Sea by the chariots and horsemen of Pharaoh, the moment before their deliverance. Deliverance became a keyword in Anglophone political rhetoric, a term that fused Providence and Liberation.

© Twentieth Century Fox.

© Twentieth Century Fox.Over the coming centuries, this Protestant reading of Exodus would go through some surprising twists. The Reformers had sought deliverance from the Papacy, but radical Puritans condemned intolerant Protestant clergy as ‘Egyptian taskmasters’. Rhetoric that had once been trained on ecclesiastical oppression was turned against ‘political slavery’, as revolutionaries in 1649, 1688 and 1776 co-opted biblical narrative. For Oliver Cromwell, Israel’s journey from Egypt through the Wilderness towards Canaan was ‘the only parallel’ to the course of English Revolution. For John Milton, tolerationist and republican, England’s Exodus led to ‘civil and religious liberty’, a phrase coined in Cromwellian England. The most startling development occurred during the American Revolution, when Patriots unleashed the language of slavery and deliverance against ‘the British Pharaoh’, George III. The contradiction between their libertarian rhetoric and American slaveholding galvanized the nascent anti-slavery movement on both sides of the Atlantic. Black Protestants now seized upon Exodus and the language of deliverance. ‘For the first time in history’, writes historian John Saillant, ‘slaves had a book on their side’.

African Americans inhabited the story like no other people before them. When they fled from slavery and segregation and migrated to the North, they consciously re-enacted the Exodus. In slave revolts and in the American Civil War they called on God for deliverance from Egyptian taskmasters. In the spiritual ‘Go Down Moses’, they re-imagined the United States as ‘Egyptland’, throwing into question the biblical construction of the nation as an ‘American Zion’. They sang of a deliverer who would tell old Pharaoh, ‘Let my People go’. They celebrated the abolition of the slave trade, West Indian emancipation, and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation by recalling the song of Moses and Miriam at the Red Sea.

The black use of Exodus was not without its ironies. It owed more than has been recognized to the long tradition of Protestant Exodus politics, albeit reworked and subverted. African Americans took pride in the fact that Moses married an Ethiopian (Numbers 12:1), but they were embarrassed by the sanction given to slavery in the Mosaic Law, and by the Hebrews’ oppression at the hands of African Pharaohs. Yet Exodus spoke to African American experience like no other text. Like the Children of Israel, their Red Sea moment was followed by a long and bitter Wilderness experience. On the night before his assassination, Martin Luther King Jr assured his black audience that he had ‘seen the Promised Land’. Barack Obama talked of ‘the Joshua Generation’ completing the work of King’s ‘Moses Generation’, but the land of milk and honey can still seem like a distant prospect.

Heading image: Dura Europos Synagogue wall painting showing the Hebrews leaving Egypt. Adaptation by Gill/Gillerman slides collection, Yale. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Moses the liberator: Exodus politics from Eusebius to Martin Luther King Jr. appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTop five Robert Altman films by soundFrozen and the Disney Princess SongPopulation ecologists scale up

Related StoriesTop five Robert Altman films by soundFrozen and the Disney Princess SongPopulation ecologists scale up

Population ecologists scale up

“Life is a train of moods like a string of beads, and, as we pass through them, they prove to be many-colored lenses which paint the world their own hue, and each shows only what lies in its focus.” Ralph Waldo Emerson, Experience, 1844.

The concept of looking at nature through multiple lenses to see different things is not new and has been long recognized. As always, the devil is in the details. Recent developments in analytical tools and the embracement of an integrative metapopulation concept and the newly emergent field of functional biogeography, are allowing exciting new insights to be made by population ecologists that have direct bearing on our understanding of the effects of environmental change on biodiversity patterns.

The metapopulation concept posits that isolated populations of organisms are connected through dynamics of dispersal and extinction. Across a landscape, areas of suitable habitat occur, which at one point in time may or may not host a viable population of a particular species. I study this concept with terrestrial plants, and have asked what environmental conditions determine suitable habitat for metapopulations.

Much of the foundational work in this topic was conducted on butterfly populations in meadows across otherwise forested habitat. Regardless of study organism, embracement of this concept has been enough to make population ecologists realize that studying single populations may give only a limited view on generalities of ecology and evolution. Indeed, taking this concept on board, has led population ecologists to want to predict in which areas of suitable habitat across the landscape a new population may establish.

“There’s no getting away from field work!”

There are obvious conservation and management implications that result from being able to predict the geographical distribution of a species, whether an invasive exotic spreading across the globe, or an endangered organism. Unfortunately, just knowing where a species or a group of species may occur across the landscape is not enough. Individuals in some populations may have low fitness and their populations may be barely hanging on. For some species such as potential island colonizers, it has been proposed that limited ability to colonize vacant habitat patches may be due to the occurrence of closely related species occupying a similar niche.

Important ‘missing pieces’ from a full understanding of the metapopulation puzzle have been through inclusion of population growth rate estimates and incorporation of species evolutionary relationships (i.e., their phylogenic ancestry). Population ecologists have been toiling away making fitness estimates of their species of interest in the field. Systematists, on the other hand, have been grinding it out in the lab to generate the molecular data necessary to construct phylogenetic trees to help classify their species.

Larch Forest in Autumn. Skarbin Laerchen Mischwald. By Johann Jaritz. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Larch Forest in Autumn. Skarbin Laerchen Mischwald. By Johann Jaritz. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsCommunity ecologists studying multispecies assemblages, as a third-dimensional angle to this question, have been working with geographers to develop species distribution models. It is only recently that the analytical tools have emerged that allow these groups of scientists to collaborate and address questions of common interest about metapopulations.For example, Cory Merow and colleagues have recently shown how Bayesian models can be used to propagate uncertainty estimates in the application of integral projection models (IPMs) to forecast growth rates as part of predictive demographic distribution models (transition matrix models could also be used). In other words, species geographic distribution predictions can be improved by accounting for population-level fitness estimates.

In another study, Oluwatobi Oke and colleagues have shown how phylogenetic relationships among 66 co-occurring species in populations across a metapopulation structured landscape of Canadian barrens can improve understanding of species distribution patterns. The basis for Oke et al.’s phylogenetic patterns among their species was the large angiosperm supertree based upon nucleotide sequence data of three genes from over 500 species.

The basis for all of the work described above are precise and accurate estimates of individual fitness and population growth rates. There’s no getting away from field work! Methods for carrying out the field work component of these studies, to allow the use of modern statistical methods including Bayesian analysis, IPMs, and transition matrix models, have to be planned and carried out with care. We have come a long way in the last decade in enabling population studies to scale up to address fundamental questions at higher levels of the ecological hierarchy.

The field of population demography is moving fast. For example, the recent launch of the COMPADRE Plant Matrix Database, with accurate demographic information for over 500 plant species in their natural settings worldwide, will make addressing these scale-related types of comparative evolutionary and ecological questions even more tractable in the future.

The post Population ecologists scale up appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA perfume for lonelinessIt’s not just about treating the cancerRelax, inhale, and think of Horace Wells

Related StoriesA perfume for lonelinessIt’s not just about treating the cancerRelax, inhale, and think of Horace Wells

December 12, 2014

Top 5 reasons why young professionals love the OHA Annual Meeting

You may have seen representatives of the University of Florida’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP) at the OHA Annual Meeting this year. We rumbled down hallways in a pack six strong, all twenty-five years old and younger, all smiles, all ears, and all left feet. After years working behind the scenes, this was for most of us our first national academic conference–and the farthest north we’ve ever ventured. We were militantly ready to learn about the field and claim our place in it.

The relationship between junior and senior scholars is cyclical, yet the world we’re learning in is new and different in many ways: fraught with new ethics questions, digitization challenges, and multiplying global crises oral historians are called to record and interpret. Our advisors, older colleagues, and titan historians hand us the projects, the inspiration, and the advice, and with that comes meaning and structure that help us face the new day. The rest is up to us, and that responsibility is titillating and frightening.

Besides the food, music, and friendly faces, here are five reasons why young professionals loved the OHA Annual Meeting.

(1) Big ideas, executed.

SPOHP staff posing excitedly during the OHA Annual Meeting in Madison, WI.

SPOHP staff posing excitedly during the OHA Annual Meeting in Madison, WI.When undergraduates and postbacs transition into the staff at SPOHP, they have boundless ambitions that range from reorganizing project databases to writing field-redefining case studies. But how to get there? Oftentimes, those who collaborate on projects only see their share of the work and aren’t privy to the mainframe, the construction of a whole project start to finish. Individually, we become so concerned with doing our jobs right and on time that we miss the forest for the trees. We learned last month that we will connect to the field in ways that are meaningful to us, and in tandem with each other. Diana Dombrowski, our web coordinator, was most inspired by University of Kentucky Doug Boyd’s OHMS and the prospects of open-source programs. Our resident musician, Chelsea Carnes, arrived ridiculously early to Michael Honey, Jonathan Overby, and Pat Krueger’s plenary session on African-American song and poetry. Senior research staff Sarah Blanc says, “I was fascinated by the number of younger scholars pursuing incredibly cutting edge research. It made me want to step up my game. It was also reassuring to hear how much thought and energy went into the ethical aspects of their work.” Watching scholars present their lifetime work, with joy, reminded us that when it comes to developing our own innovations and interests, the reins are already ours.

(2) Openness to change — and to us.

Diana Dombrowski presenting at the OHA Annual Meeting.

Diana Dombrowski presenting at the OHA Annual Meeting.Diana was pleasantly dismayed facing a full house when she spoke during the roundtable, “Recording Voices and Inspiring Communities.” Professors leaned forward in seats and against walls and columns to listen for a while; voices from near the door shouted encouragement to the front during discussion. People really wanted to know, and wanted to share what they know.

It’s important to start talking soon because we will face the field’s challenges together. SPOHP’s Latina/o Diaspora in the Americas Coordinator, 22-year-old Genesis Lara, puts her experience as an audience member at Diana’s panel like this:

“The discussion of the panel quickly turned into a conversation regarding ethics in the oral history community, especially in terms of conducting oral histories among undocumented communities. It was a debate that was repeated in several of the panels that our staff was fortunate to attend. Throughout the entire meeting, there was this atmosphere of question and curiosity: where do we go from here?”

Knowing that established members of the OHA care what we think and how we do things encourages more people to join the conversation.

(3) The focus on fieldwork gives us a chance to shine.

SPOHP staff conducting fieldwork in Mississippi.

SPOHP staff conducting fieldwork in Mississippi.Every year, Sarah Blanc returns from UF’s annual trip to the Mississippi Delta, sleeps a couple of days, writes some thank you cards, and starts preparing all over again. “Fieldwork” rolls off the tongue dramatically, but it’s tough to coordinate with community members in another state while navigating university policies and student schedules; then, the fourteen-hour days on-site. Although the concept is Dr. Ortiz’s, the trips and their stories become ours and the interviewees’. Obviously, in oral history, no one can go it alone.

Then go on and try to condense those relationships, hundreds of hours of audio, and what it all means to you into a bullet list on a PowerPoint. Oral History in Motion teaches us that stories about topics from Freedom Summer to the anti-incarceration movement matter, and it’s our job not to give meaning but to interpret, to convey the excitement and sense of discovery to people who weren’t with us. We work hard but we’ve been privileged through the opportunities we’ve been given. It’s now our privilege to share with you the places that brought us to Madison, from Mississippi to the Dominican Republic.

(4) Oral history has a pantheon of heroes.

I can’t believe you did that.

I can’t believe you did that.Donald Ritchie was reclining in a chair eating those free Concourse Hotel hard candies. He was trying to enjoy a panel about the legacy of Freedom Summer, featuring the up-and-coming work of Senate and House oral historians Jackie Burns and Katherine Scott, and UF’s Sarah Blanc. That’s too bad.

My plan of attack, carefully conceived, started with casually sidling up (harder than you’d think) and saying a little too loudly, “SORRY TO LURK.” The final product of our brief conversation is above.

My overtures of friendship were by most standards terrible, but here’s the thing: I teach SPOHP’s internship class around Dr. Ritchie’s Doing Oral History every year, twice a year; it’s how I learned what to expect and what to ask as an undergraduate too. I watch students read it and discuss it, and then they get that oral history has distinct potential bounded only by the researcher. Donald Ritchie makes that moment possible every year, twice a year, in our classroom and many others. He embodies the transformation from student to researcher and in many cases, non-major to major in history. We can’t thank him correctly, so we took a picture together.

(5) Oral history has many faces: activists, public servants, poets, musicians.

Sarah Blanc discussing fieldwork at the OHA Annual Meeting

Sarah Blanc discussing fieldwork at the OHA Annual MeetingChelsea Carnes is a musician and activist as well as a student, but she found inspiration in a meeting of historians exactly because they weren’t just historians. There are both academics that fill multiple roles–Mike Honey, the activist, historian, and musician–and full-time artists and union organizers who have something to say. The resulting free exchange of inspiration and experience opened the door and let the fresh air in. Chelsea explains it best:

“Oral historians are addressing ways that history can come to life through activism, education, art…I’ve always been told that the career of historian is a very lonely and self-reliant one, but at the conference I saw and heard about historians working together cooperatively and really engaging with their communities. There was a real focus on a macroscopic objective and humanistic worldview that I found very progressive and exciting.”

Chelsea picked up on what Genesis calls our “essence as human beings who are trying to help other human beings, through the most elemental of things: our human stories.” We’re proud to be a part of oral history’s motley crew.

Oral history’s motley crew

Oral history’s motley crewAll images courtesy of Jessica Taylor.

The post Top 5 reasons why young professionals love the OHA Annual Meeting appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat we’re thankful forRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingAcademics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. Pickron

Related StoriesWhat we’re thankful forRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingAcademics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. Pickron

Top five Robert Altman films by sound

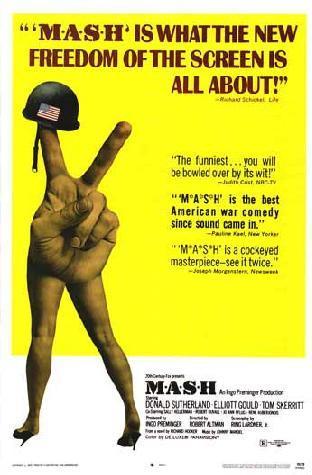

Director Robert Altman made more than thirty feature films and dozens of television episodes over the course of his career. The Altman retrospective currently showing at MoMA is a treasure trove for rediscovering Altman’s best known films (M*A*S*H, Nashville, Gosford Park) as well as introducing unreleased shorts and his little-known early work as a writer.

Every Altman fan has her or his own list of favorite films. For me, Altman’s use of music is always so innovative, original, and unprecedented that a few key films stand out from the crowd based on their soundtracks. Here are my top five Altman films based on their soundtracks:

1. Gosford Park (2001): The English heritage film meets an Agatha Christie murder mystery, combining an all-star ensemble cast and gorgeous location shooting with a tribute to Jean Renoir’s La Règle du Jeu (1939). Jeremy Northam plays the real-life British film star and composer Ivor Novello. Watch for the integration of Northam/Novello’s live performances of period songs with the central murder scene, in which the songs’ lyrics explain (in hindsight) who really committed the murder, and why.

2. Nashville (1975): Altman’s brilliant critique of American society in the aftermath of Vietnam and Watergate. Nashville stands as an excellent example of “Altmanesque” filmmaking, in which several separate story strands merge in the climactic final scene. Many, although not all, of the songs were provided by the cast, which includes Henry Gibson as pompous country music star Haven Hamilton, and the Oscar-nominated Lily Tomlin as the mother of two deaf children drawn into a relationship with sleazy rock star Tom Frank (Keith Carradine, whose song “I’m Easy” won the film’s sole Academy Award).

3. M*A*S*H (1970): Ok, I will admit it. It took me a long, long time to appreciate M*A*S*H. Growing up in 1970s Toronto, I couldn’t accept Donald Sutherland and Elliot Gould as Hawkeye Pierce and Trapper John — familiar characters from the weekly CBS TV series (but played by different actors). Looking back, I realize that M*A*S*H really did break all the rules of filmmaking in 1970, not least of which because it appealed to the anti-Vietnam generation. Like so many later Altman films, what appears to be a sloppy, improvised, slap-dash film is in fact sutured together through the brilliant, carefully edited use of Japanese-language jazz standards blared over the disembodied voice of the base’s loudspeaker.

4. McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971): Filmed outside of Vancouver, Altman’s reinvention of the Western genre stars Warren Beatty and Julie Christie. The film uses several of Leonard Cohen’s songs from his 1967 album The Songs of Leonard Cohen, allowing the songs to speak for often inarticulate characters. Watch for how the opening sequence, showing Beatty/McCabe riding into town, is closely choreographed to “The Stranger Song” as is Christie/Miller’s wordless monologue to “Winter Lady” later in the film — all to the breathtaking cinematography of Vilmos Zsigmond, who worked with Altman on Images (1972) and The Long Goodbye (1973) as well.

5. Aria (segment: “Les Boréades”) (1987): Made during Altman’s “exile” from Hollywood in the 1980s, this film combines short vignettes set to opera excerpts by veteran directors including Derek Jarman, Jean-Luc Godard, and Julien Temple. Altman’s contribution employs the music of 18th-century French composer Jean-Philippe Rameau. The sequence was a revelation to me personally, since it contains the only feature film documentation of Altman’s significant contributions to the world of opera. One of the first film directors to work on the opera stage, Altman directed a revolutionary production of Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress at the University of Michigan in the early 1980s: the work was restaged in France and used for the Aria Later, Altman collaborated with Pulitzer-Prize winning composer William Bolcom and librettist Arnold Weinstein to create new operas (McTeague, A Wedding) for the Lyric Opera of Chicago.

Rounding out the top ten would be Short Cuts (1993), Kansas City (1996), The Long Goodbye (1973), California Split (1974), and Popeye (1980) — Robin Williams’ first film, and definitely an off-beat but entertaining musical.

Headline Image: Film. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Top five Robert Altman films by sound appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFrozen and the Disney Princess SongCarols and CatholicismVirginia Woolf’s Orlando and the country house

Related StoriesFrozen and the Disney Princess SongCarols and CatholicismVirginia Woolf’s Orlando and the country house

It’s not just about treating the cancer

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is emotional and overwhelming for patients. While initially patients may appropriately focus on understanding their disease and what their treatment options are, supportive care should begin at diagnosis and is a vital part of care across the continuum of the cancer experience. Symptom management, as a part of supportive care, is aimed at preventing the side effects of the cancer and its treatment. Appropriately managing these side effects will help enable patients to maintain their quality of life through their cancer journey.

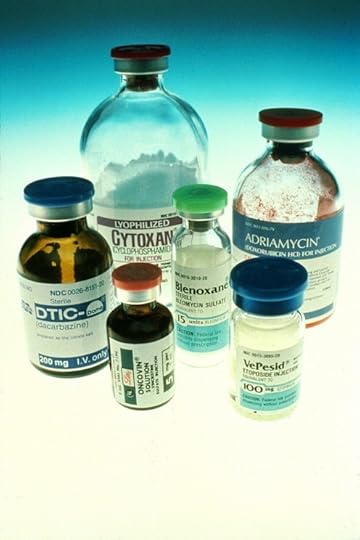

It is well-known that, unfortunately, many cancer treatments (mainly chemotherapy) will cause nausea and vomiting. Fortunately, decades of research have improved our understanding of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and have led to the development of very effective and safe drugs to prevent and manage these bothersome and potentially debilitating side effects. Research has also shown us that often combinations of two or three drugs taken together, sometimes over multiple days, offers the best CINV prevention with certain chemotherapies. With the appropriate use of these “antiemetic” drugs, CINV can now be prevented in the majority of patients. However, 20-30% of patients may still suffer from these side effects. Some of these patients are refractory in that the recommended antiemetic prophylactic treatments, for whatever reason, do not prevent the nausea and/or vomiting. Other patients, unfortunately, are incorrectly managed and are not given the appropriate preventative treatments. This is indefensible and not representative of an optimal patient-centered approach to cancer management. Physicians should be approaching symptom management in the same manner as they approach cancer therapeutics, utilizing the best and most appropriate treatments available.

Chemotherapy bottles, National Cancer Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Chemotherapy bottles, National Cancer Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.With the goal of making prevention of CINV simpler and more convenient, the first antiemetic combination product has recently been developed, combining two drugs in a single pill that only needs to be taken right before chemotherapy is administered along with a single dose of dexamethasone. This new product (called NEPA or Akynzeo®) was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (and is under review in Europe) after years of development. The combination not only comprises two drugs from two classes, an NK1 receptor antagonist (RA) and a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, representing the current standard-of-care. The NK1 RA (netupitant) and the 5-HT3 RA (palonosetron), however, are long-acting, and palonosetron is recommended by many guidelines committees as the preferred 5-HT3 RA.

Three of the pivotal studies conducted to establish the efficacy and safety of NEPA were recently published in Annals of Oncology. These selected articles convincingly show efficacy with the NEPA combination, superior prevention of CINV compared with that of oral palonosetron, and maintenance of efficacy when given over multiple cycles of chemotherapy known to result in nausea and vomiting.

NEPA appears to be a promising new agent with the potential to address some of the barriers interfering with physicians’ administration of recommended antiemetics. This is accomplished by conveniently packaging effective and appropriate antiemetic prophylaxis in a single, oral dose that is taken only once per chemotherapy cycle, along with a single dose of dexamethasone.

Hopefully this will help, because preventing the symptoms has to be as important as treating the disease.

Heading image: Cancer cells by Dr. Cecil Fox (Photographer) for the National Cancer Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post It’s not just about treating the cancer appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRelax, inhale, and think of Horace WellsWorld AIDS Day reading listA perfume for loneliness

Related StoriesRelax, inhale, and think of Horace WellsWorld AIDS Day reading listA perfume for loneliness

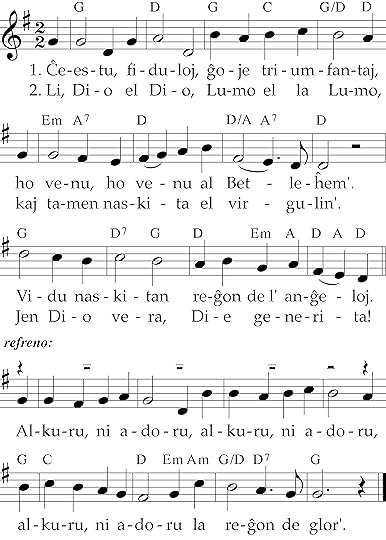

Carols and Catholicism

Carols bring Christians together around the Christ Child lying in the manger. During Advent and at Christmas, Christians everywhere sing more or less the same repertoire. Through our carols, we share the same deep delight at the birth of a poor child who was to become the Saviour of all human beings.

The carols are wonderfully ecumenical in their origins. Four verses and the tune of ‘Adeste Fideles’ (‘Come all ye faithful’) come from an eighteenth-century Roman Catholic layman, John Francis Wade. ‘Angels we have heard on high’ is a traditional French carol, now commonly sung to a tune arranged by Edward Shippen Barnes (d. 1958), an American organist and composer. The text of ‘Hark the herald angels sing’ was written by Charles Wesley. Its widely used melody is taken from Felix Mendelssohn, who was born into a Jewish family and brought up a Lutheran. Isaac Watts, a non-conformist, composed the words of ‘Joy to the world’. The music, although often attributed to George Frederick Handel, seems of be of English origin.

An Episcopalian bishop, Phillips Brooks, wrote ‘O little town of Bethlehem’, and the tune we normally hear accompanying this comes from Ralph Vaughan Williams.

‘Ding dong merrily on high‘ is sung to a dance tune from sixteenth-century France; the text was composed by an English enthusiast for carols, George Ratcliffe Woodward (d. 1934). We owe ‘Away in a manger’ to a nineteenth-century children’s book used by American Lutherans. The words for ‘See amid the winter’s snow’ were written by Edward Caswell, who became a Roman Catholic and joined Blessed John Henry Newman in the Birmingham Oratory. Sir John Goss, an Anglican organist and composer, provided the musical setting.

‘Silent night, holy night’ was the work of two Austrian Catholics, the priest and organist of a country church. An Irish Protestant, Nahum Tate, probably composed the text of ‘While shepherds watched their flocks‘, which is often sung to a tune taken from Handel.

These and other familiar carols have been composed by members of different Christian communities who lived in various parts of the world. The carols have also proved splendidly ecumenical in their use. No other collection of hymns are sung so widely by Christians when they celebrate one of the two central feasts of their liturgical year.

‘Adeste Fideles’ by Kronenberger (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

‘Adeste Fideles’ by Kronenberger (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia CommonsWith a happiness that lights up their faces, Christians sing together the carols. With the birth of the Christ Child, light has replaced darkness, and real freedom has taken over from sin. The beautiful ‘Sussex Carol’ catches the common joy of Christian believers: ‘On Christmas night all Christians sing/To hear the news the angels bring/News of great joy, news of great mirth/News of our merciful King’s birth.’ The words of this carol go back to a seventeenth-century Irish bishop, Luke Wadding. In the early twentieth century, Vaughan Williams discovered the text and the tune that we use today, when he heard it sung at Monk’s Gate in Sussex. Hence it is called the ‘Sussex Carol’.

Such carols bring Christians together around the manger. They blend beautifully text and music to unite us all and lift our spirits at Christmas. But they also remind us that the shadow of the cross falls across the birth of Jesus.

Some carols foreshadow the suffering which the Christ Child will endure for all human beings. Thus the penultimate verse of the traditional English carol, ‘The first Nowell‘, declares: ‘and with his blood mankind has bought’. ‘In dulci jubilo’, a medieval German carol, arranged by J. M. Neale (d. 1866) and entitled ‘Good Christian men, rejoice’, subtly links Bethlehem and Calvary when the second verse repeats: ‘Christ was born for this.’

The carols that feature the Magi and the gifts they offer foretell the passion of Christ. Myrrh is an aromatic resin that was widely used in the Middle East to embalm corpses. From early times Christians understood that gift to symbolize the death and burial of Jesus. ‘We three kings of Orient are’, a nineteenth-century Christmas carol from Pennsylvania, devotes a whole verse to the gift of myrrh: ‘Myrrh is mine, its bitter perfume/breathes a life of gathering gloom/sorrowing, sighing, bleeding, dying/sealed in the stone-cold tomb.’ Such carols unite Christians with the Magi in worshipping the Christ Child, whose birth is already overshadowed by the cross.

When we sing our favourite carols this Christmas, let us rejoice in their very ecumenical origins and in their use by Christians everywhere. The carols light up our faces with vivid joy. But they also recall how the shadow of Calvary fell over Bethlehem. Jesus was born into a world of all-pervasive pain and suffering.

Featured image credit: Little Twon of Bethlehem, by Phillips Brooks. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Carols and Catholicism appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFrozen and the Disney Princess SongAn excerpt from Scotland: A Very Short IntroductionThe development of peace

Related StoriesFrozen and the Disney Princess SongAn excerpt from Scotland: A Very Short IntroductionThe development of peace

December 11, 2014

Virginia Woolf’s Orlando and the country house

A ‘slobbering valentine to a member of the upper classes’, ‘an orgy of snobbery’, and ‘the apotheosis of brown-nosing’: Angela Carter’s excoriating dismissal of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928), delivered in Tom Paulin’s notorious televisual polemic, J’accuse Virginia Woolf (1991), serves as a reminder that this work has as much potential as any of her novels to provoke heated disagreements. That it should be so might seem surprising, as it is one of the most easy-going of her novels, one in which she consciously simplified her prose style in the interests of drawing in the reader effortlessly; it is also the most comic of her novels, mocking the conventions of history and biography. That Carter in particular should be so violently opposed to the novel is particularly surprising, as its willingness to rewrite conventional fictional forms anticipates her novels, and its employment of fantastic elements anticipates the ‘magic realist’ mode that she was to employ. Like Orlando, Carter’s own The Passion of New Eve (1977) also centres on a change of sex, albeit more violently wrought. Mostly intriguingly of all, in 1979 Glyndebourne Opera House commissioned Carter to write a libretto for an opera, never completed, of Woolf’s novel. Carter’s dismissal of Woolf might appear to stem from unease about working in her shadow.

To leave it there would neglect the prominence of social class in Carter’s opinion. Though the fragments of her libretto were published under the title Orlando: or, The Enigma of the Sexes, another working title was Orlando: An English Country House Opera; the country house and the aristocracy are significant factors in Orlando. Woolf’s novel was inspired by her passionate relationship with Vita Sackville-West in 1925 and 1926. Vita had been brought up at Knole in Kent, her family’s ancestral seat since the early seventeenth century; she loved the house and its history, but as a woman, she did not stand to inherit it. Vita’s family history made a strong impression on Woolf: ‘All these ancestors & centuries, & silver & gold, have bred a perfect body’, she wrote in 1924, with a hint of critical awareness of Vita’s privilege; in the same diary entry she noted how Knole could house all the poor of Judd Street, then one of the slum areas of Bloomsbury. In 1927 she was more overawed, more deeply in love, and less critical: walking round Knole with Vita, ‘All the centuries seemed lit up, the past expressive, articulate; not dumb & forgotten; but a crowd of people stood behind, not dead at all; not remarkable; fair faced, long limbed; affable; & so we reach the days of Elizabeth quite easily.’ Politically Woolf was liberal, progressive, and above all anti-authoritarian; by the 1930s she was actively involved in her local Labour Party. Visiting Knole in 1927, however, she seems to have been enchanted by a conservative ideology in which the country house serves as symbol of continuity between generations, of the centrality of monarchy to the British constitution, and of a benign relation between the aristocracy and the people. It is ‘ideological’ in the sense of masking and normalizing exploitative economic relations.

From left to right: Harold Nicolson, Vita Sackville-West, Rosamund Grosvenor, Lionel Sackville-West (1913). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

From left to right: Harold Nicolson, Vita Sackville-West, Rosamund Grosvenor, Lionel Sackville-West (1913). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. The strength of Carter’s hostility in 1991 may well have something to do with the revival of the country house ideology in British mass culture in the 1980s. ITV’s adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, in the depths of the economic recession of the early 1980s, was a particularly pointed example. Critical works such as Patrick Wright’s On Living in an Old Country (1985) and Robert Hewison’s The Heritage Industry (1987) highlighted the ways in which ‘heritage’ serves political ends. However, Carter’s remarks don’t tell the whole truth, no matter how much they resonated in their moment. Important though the country house is to Orlando, it is less important than poetry and the hero/heroine’s dogged pursuit of the muse, and poetry in turn is less important than the question of personal identity. House-building and poetry-writing stand in direct contrast to each other. In Chapter II, it is the scorn of the poet Nick Greene that makes Orlando turn to the refurbishment of his house; though when the work is complete he holds banquets there, when the banquets are at their height he retreats to his private room to enjoy the pleasures of poetry. When Orlando travels to Turkey, his/her English values are put into perspective. To the Turkish gipsies, a family lineage four or five hundred years is of negligible duration, and the desire to own a house with hundreds of bedrooms is vulgar. Viewed from a certain angle, the established aristocrat becomes a vulgar upstart. Although the house still matters to Orlando when she returns to it triumphantly in the final chapter, and although the house still holds vivid memories of the people she has known, the cause of the triumph is the recognition of Orlando’s writing; and she recalls the sceptical perspective of the gipsies.

Focusing on the relationship between Vita and Virginia, Vita’s son Nigel Nicolson described Orlando as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’, a phrase that was Carter’s starting point. If Carter’s estimate is distorted by the demands of her time, Nicolson’s isn’t quite right either: Orlando is more than a purely personal document. It raises questions about personal identity and national identity, about history and its transmission, and about the value of writing, and it does so in a way that persistently mocks established values.

Headline image: Knole House, owned by the National Trust (2009). In the early 17th century the Sackville family re-modelled the old archbishops’ palace into a stately home. Photo by John Wilder. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Virginia Woolf’s Orlando and the country house appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA reading list of Roman classicsTiberius on Capri: in pursuit of vice or just avoiding mother?A reading list of Ancient Greek classics

Related StoriesA reading list of Roman classicsTiberius on Capri: in pursuit of vice or just avoiding mother?A reading list of Ancient Greek classics

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers