Oxford University Press's Blog, page 726

December 11, 2014

Relax, inhale, and think of Horace Wells

Many students, when asked by a teacher or professor to volunteer in front of the class, shy away, avoid eye contact, and try to seem as plain and unremarkable as possible. The same is true in dental school – unless it comes to laughing gas.

As a fourth year dental student, I’ve had times where I’ve tried to avoid professors’ questions about anatomical variants of nerves, or the correct way to drill a cavity, or what type of tooth infection has symptoms of hot and cold sensitivity. There are other times where you cannot escape having to volunteer. These include being the first “patient” to receive an injection from one of your classmate’s unsteady and tentative hands. Or having an impression taken with too much alginate so that all of your teeth (along with your uvula and tonsils) are poured up in a stone model.

But volunteering in the nitrous oxide lab … that’s a different story. The lab day is about putting ourselves in our patients’ shoes, to be able to empathize with them when they need to be sedated. For me, the nitrous oxide lab might have been the most enjoyable 5 minutes of my entire dental education.

In today’s dental practice, nitrous oxide is a readily available, well-researched, incredibly safe method of reducing patient anxiety with little to no undesired side effects. But this was not always the case.

The Oxford Textbook of Anaesthesia for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery argues that “with increasingly refined diets [in the mid-nineteenth century] and the use of copious amounts of sugar, tooth decay, and so dentistry, were on the increase.” Prior to the modern day local anesthesia armamentarium, extractions and dental procedures were completed with no anesthesia. Patients self-medicated with alcohol or other drugs, but there was no predictable or controllable way to prevent patients from experiencing excruciating pain.

That is until Horace Wells, a dentist from Hartford, Connecticut started taking an interest in nitrous oxide as a method of numbing patients to pain.

Dr Horace Wells, by Laird W. Nevius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr Horace Wells, by Laird W. Nevius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Wells became convinced of the analgesic properties of nitrous oxide on 11 December 1844 after observing a public display in Hartford of a man inhaling the gas and subsequently hitting his shin on a bench. After the gas wore off, the man miraculously felt no pain. With inspiration from this demonstration and a strong belief in the analgesic (and possibly the amnestic) qualities of nitrous oxide, on 12 December, Wells proceeded to inhale a bag of the nitrous oxide and have his associate John Riggs extract one of his own teeth. It was risky—and a huge success. With this realization that dental work could be pain free, Wells proceeded to test his new anesthesia method on over a dozen patients in the following weeks. He was proud of his achievement, but he chose not to patent his method because he felt pain relief should be “as free as the air.”

This discovery brought Wells to the Ether Dome at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Before an audience of Harvard Medical School faculty and students, Wells convinced a volunteer from the audience to have their tooth extracted after inhaling nitrous oxide. Wells’ success came to an abrupt halt when this volunteer screamed out in pain during the extraction. Looking back on this event, it is very likely that the volunteer did not inhale enough of the gas to achieve the appropriate anesthetic effect. But the reason didn’t matter—Wells was horrified by his volunteer’s reaction, his own apparent failure, and was laughed out of the Ether Dome as a fraud.

The following year, William Morton successfully demonstrated the use of ether as an anesthetic for dental and medical surgery. He patented the discovery of ether as a dental anesthetic and sold the rights to it. To this day, most credit the success of dental anesthesia to Morton, not Wells.

After giving up dentistry, Horace Wells worked unsuccessfully as a salesman and traveled to Paris to see a presentation on updated anesthesia techniques. But his ego had been broken. After returning the United States, he developed a dangerous addiction to chloroform (perhaps another risky experiment for patient sedation, gone awry) that left him mentally unstable. In 1848, he assaulted a streetwalker under the influence. He was sent to prison and in the end, took his own life.

This is the sad story of a man whose discovery revolutionized dentists’ ability to effectively care for patients while keeping them calm and out of pain. As a student at the University of Connecticut School of Dental Medicine, it is a point of pride knowing that Dr. Wells made this discovery just a few miles from where I have learned about the incredible effects of nitrous oxide. My education has taught me to use it effectively for patients who are nervous about a procedure and to improve the safety of care for patients with high blood pressure. This is a day we can remember a brave man who risked his own livelihood in the name of patient care.

Featured image credit: Laughing gas, by Rumford Davy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Relax, inhale, and think of Horace Wells appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLaying to rest a 224 year-old controversyWorld AIDS Day reading listLeonard Cohen and smoking in old age

Related StoriesLaying to rest a 224 year-old controversyWorld AIDS Day reading listLeonard Cohen and smoking in old age

December 10, 2014

A laughing etymologist in a humorless crowd

I have noticed that many of my acquaintances misuse the phrases a dry sense of humor and a quiet sense of humor. Some people can tell a joke with a straight face, but, as a rule, they do it intentionally; their performance is studied and has little to do with “dryness.” A quiet sense of humor is an even murkier concept. What is it: an ability to chuckle to oneself? Smiling complacently when everybody else is roaring with laughter? Being funny but inoffensive? Sometimes readers detect humor where it probably does not exist.

For example, in the Scandinavian myth of the final catastrophe, the great medieval scholar Snorri Sturluson noted that the lower jaw of the wolf, the creature destined to swallow the whole world, touched the ground, while the upper jaw reached to the sky. If the wolf, he added, could open its mouth wider, it would have done so. For at least two hundred years scholars have been admiring Snorri’s dry sense of humor, though there is no certainly that Snorri had any sense of humor at all. What we read in his text is an accurate statement of fact, a description of a monster with a mouth open to its full extent.

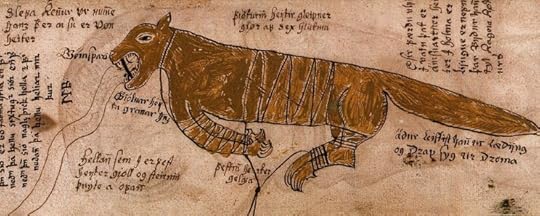

Fenrisulfr tied up, a river flows from his mouth. From the 17th century Icelandic manuscript AM 738 4to, now in the care of the Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Fenrisulfr tied up, a river flows from his mouth. From the 17th century Icelandic manuscript AM 738 4to, now in the care of the Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. In Europe, if we disregard the situation known form Ancient Greece and Rome, the modern sense of humor, which, first and foremost, presupposes laughter at verbal rather than at practical jokes, hardly existed before the Renaissance. (Practical jokes seldom thrill us.) The likes of Mark Twain and Oscar Wilde would not have had an appreciative audience in the Middle Ages. A look at the words pertaining to laughter may not be out of place here. The verb laugh has nothing to do with amusement. Its most ancient form sounded as khlakhkhyan (kh, which, as the above transcription shows, was long, stands for ch in Scots loch and in the family name MacLauchlan). If this word had currency before the formation of the system of Germanic consonants, its root was klak, which belongs with cluck, clack, click, clock, and other similar sound-imitative formations. The most primitive word for “laugh” seems to have designated a “guttural gesture,” akin to coughing or clearing one’s throat. Chuckle, a frequentative form of chuck, is a cousin of cackle. Giggle, another onomatopoeic verb, is a next-door neighbor of chuckle. The origin of Latin ridere (“to laugh”: compare ridiculous, deride, and risible) is unknown.

Nowadays, few words turn up in our speech more often than fun. Fun is the greatest attraction of everything. On campus, after the most timid souls get out of the math anxiety course, they are assured that math will be fun. A popular instructor is called a fun professor; students wish one another a fun class. Fun is the backbone of our education, and yet the word fun surfaced in texts only in the seventeenth century, and, like many nouns and verbs belonging to this semantic sphere, was probably a borrowing by the Standard from slang. Its etymology is disputable; perhaps fun is related to fond, and fond meant “stupid.” Joke, contemporaneous with fun, despite its source in Latin, also arose as slang.

We seldom think of the inner form of the word witty. Yet it is an obvious derivative of wit. One could expect witty to mean “wise, sagacious,” the opposite of witless (compare also unwitting), and before Shakespeare it did mean “clever, ingenious.” In German, the situation is similar. Geistreich (Geist + reich) suggests “rich in spirit (mind)” but corresponds to Engl. “witty.” Likewise, jest had little to do with amusement. Latin gesta (plural) meant “doings, deeds” and is familiar from the titles of innumerable Latin books (for example, Gesta danorum “The Deeds of the Danes”). Apparently, in the absence of the concept we associate with wit speakers had to endow the existing material with a meaning that suddenly gained in importance or surfaced for the first time. “The street,” where slang flourished, reveled in low entertainment and supplied names for it. Sometimes the learned also felt a need for what we call fun but were “lost for words” and used Latin nouns in contexts alien to them.

© Elnur via iStock.

© Elnur via iStock. Jest is by far not the only example of this process. Hoax, which originally meant “to poke fun at,” is an eighteenth-century verb (at first only a verb) derived from Latin hocus, as in hocus-pocus. By an incredible coincidence, Old English had hux “mockery,” a metathesized variant of husc, a word with a solid etymology, but in the remote past it may have meant “noise.” When the history of the verbs for “laugh” comes to light, it often yields the sense “noise.” Such is Swedish skratta (with near identical cognates in Norwegian and Danish). People, as rituals and books inform us, laughed on various occasions: to promote fertility (a subject I cannot discuss here), to express their triumph over a vanquished enemy, or to show that they were happy. Noise sometimes constituted part of their reaction. None of that had anything to do with our sense of humor.

German Scherz “joke” first denoted “a merry jump.” Its synonym Spaß reached German from Italian (spasso; in the seventeenth century, like so many words being discussed here), but German did not remain a debtor. It “lent” Scherz to Italian, which returned it to the European languages as Scherzo, a musical term. The origin of Dutch grap “joke” is uncertain (so probably slang). Almost the entire English vocabulary of laughter and mockery is late: either the words were coined about four hundred year ago, or new meanings of old words arose. It is as though a revolution in attitudes toward laughter (or at least one aspect of it) occurred during and soon after the Renaissance. People felt a need for new terms expressing what we take for eternal impulses and began to promote slang and borrow right and left.

Below I will list a few verbs with their dates and some indication of their origin. The roman numbers refer to the centuries.

Jeer (XVI; “fleer and leer have affinities for form and meaning”; so The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology), fleer (XV, possibly from Scandinavian), sneer (XVI; perhaps from Low German or Dutch), flout (XVI, possibly from Dutch), taunt (XVI, from French), banter (XVII, of unknown origin).Only scoff and scorn are considerably older, though both also came from abroad. To be sure, the picture presented above is too simple; it does not take into account the history of people. New words were borrowed, while old ones fell into desuetude. The formula “of unknown origin” does not mean that no suggestions about their etymology exist. They do, but none is fully convincing.

Our ancestors laughed as much as we do, but we have added a new dimension to this process: we can laugh at a witty saying (when they spoke their native languages, this was, apparently, a closed art to them). Strangely, the educated “barbarians” enjoyed Roman comedies, but laughing at Latin witticisms taught them nothing and did not become a transferable skill. The Europeans who descended from those “barbarians” needed a long time to catch up with their teachers. A study of laughter is not only a window to the development of European mentality. It also sheds light on popular culture. We observe how the slang of the past gained respectability and became part of the neutral style. Here etymologists can make themselves useful to everyone who is interested in how we have become what we are. Enjoy yourselves, friends, but don’t be always the last to laugh.

The post A laughing etymologist in a humorless crowd appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesYes? Yeah….Monthly etymology gleanings for November 2014The ayes have it

Related StoriesYes? Yeah….Monthly etymology gleanings for November 2014The ayes have it

Human Rights Awareness Month case map

To mark Human Rights Day, we have produced a map of 50 landmark human rights cases, each with a brief description and a link to a free article or report on the case.

The cases were chosen in conjunction with the editors of the Oxford Reports on International Law. These choices were intended to showcase the variety of international, regional, and national mechanisms and fora for adjudicating human rights claims, and the range of rights that have been recognized.

The following map provides a quick tour to these cases, highlighting trends and themes, some positive, some negative.

Major Historical Events

A lot of these cases are important because of the way they demonstrate the possibility of righting historic injustices: for the disappeared of Honduras, for victims of Argentina’s “dirty war,” for Hitler’s slaves, heroes of the Chernobyl disaster, and East Germans gunned down trying to reach the West. They also shine a light on what happens in the aftermath of war: Peruvian politicians attempting to pass amnesty laws to prevent accountability, people on the losing side of World War II having their property stolen, and the operation of post-World War I minorities treaties.

Africa

From a human rights standpoint we probably have a number of preconceptions about Africa – large scale atrocities and impunity. While that is horribly true in places there are also aspects of the cases highlighted in our map that might surprise some. The one case about an investor’s rights (Diallo) features an African state, not one of the typical capital exporting states, taking legal action on behalf of its citizen. There is also the range of fora in Africa that offer remedies. In addition to the obvious forum – the Commission and Court of the African regional human rights system, we have cases from the East-African Court of Justice and the ECOWAS Community Court both finding that they are empowered to adjudicate on human rights issues as universal as the rights of indigenous peoples and anti-slavery. Whereas you wouldn’t be surprised to see a post-Apartheid decision from the South African domestic courts in this list, it is instructive to see a case from Ugandan domestic courts on press freedom.

Expansion of Rights

The modern proliferation of rights is often a topic of humorous exaggeration. These cases exemplify a great breadth of rights beyond the classic civil and political rights of freedom from torture, or free speech. Where it does address these topics there is a novel twist: on torture, whether it is OK to extradite criminals to a place where they face torture; on free speech, whether Holocaust denial should be protected. Several have gender aspects: states’ obligations to prevent domestic violence, women being required to prove they are the “breadwinner” in order to have access to unemployment benefits, sexual violence against women as a means to silence political dissent. Others bring in group rights: self-determination, rights of indigenous peoples, and even the rights of tribes imported via the slave trade. Add to these cases on the execution of minors, anti-homosexuality laws, and treating a person’s DNA as their private matter, and we see how far the law has developed.

Unattractive Victims

Opponents of human rights litigation often point out that these rights are frequently claimed by people whom we deplore. It is true that many of the people making claims in these cases were accused of murder and terrorism, or at least were sworn enemies of the state that (allegedly) abused them. So the lesson here is that these are human rights, not “nice people’s” rights.

Human Rights as an Excuse

With so many human rights remedies available there is a temptation for litigants, whether states or individuals, to use human rights as a way to get an issue before a court. You would expect the case between Georgia and the Russian Federation at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to be about the illegal use of force by Russia. Instead, Georgia sued under a human rights treaty: the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD). Why? Ordinarily Russia could refuse to submit to a legal procedure at the ICJ, but the CERD contains a provision saying that in any dispute under that treaty between two states that have ratified it (which Russia and Georgia had) both parties must agree to the jurisdiction of the ICJ. So Georgia gets minor revenge for Russia’s invasion and annexation by suing Russia for racial discrimination.

Misleading Maps

You might think the clustering of pins in our map is about abuses, but actually it demonstrates access to a legal process (and, depending on implementation) a remedy. So plenty of pins in Europe, and Israel, but none in Saudi Arabia or North Korea.

These 50 cases are by no measurable sense the 50 greatest or most important cases, but they do amply demonstrate the expansion and increasing profile of this, mostly admirable, element of the rule of law.

Featured image credit: Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms”. Photo by dbking. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Human Rights Awareness Month case map appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesKenneth Roth on human rightsAcross the spectrum of human rightsCharting events in international security in 2013

Related StoriesKenneth Roth on human rightsAcross the spectrum of human rightsCharting events in international security in 2013

Kenneth Roth on human rights

Today, 10 December, is Human Rights Day, commemorating The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. In celebration, we’re sharing an edited extract from International Human Rights Law, Second Edition by Kenneth Roth, Executive Director of Human Rights Watch.

The modern state can be a source of both good and evil. It can do much good – protecting our security, ensuring our basic necessities, nurturing an environment in which people can flourish to the best of their abilities. But when it represses its people, shirks its duties, or misapplies its resources, it can be the source of much suffering.

International human rights law sets forth the core obligations of governments toward their people, prescribing the basic freedoms that governments must respect and the steps they must take to uphold public welfare. But the application of that law often differs from the enforcement of statutes typically found in a nation’s law books.

In countries that enjoy the rule of law, the courts can usually be relied on to enforce legislation. The rule of law means that courts have the independence to apply the law free of interference, and powerful actors, including senior government officials, are expected to comply with court orders.

In practice, there is no such presumption in most of the countries where my organization, Human Rights Watch, works, and where international human rights law is most needed. The judges are often corrupt, intimidated, or compromised. They may not dare hold the government to account, or they may have been co-opted to the point that they do not even try, or the government may succeed in ignoring whatever efforts they make.

International human rights law should be seen as a law of last resort when domestic rights legislation fails. Judicial enforcement is always welcome, but when it falls short, human rights law provides a basis that is distinct from domestic legislation for putting pressure on governments to uphold their obligations.

Human rights groups investigate and report on situations in which governments fall short of their obligations. The resulting publicity, through the media and other outlets, can undermine a government’s standing and credibility, embarrassing it before its people and peers and generating pressure for reform.

Beyond documenting and reporting violations of human rights law, human rights groups must shape public opinion to ensure that the exposure of government misconduct is met with opprobrium rather than approval. In part this is done by citing international law to convince the public of a global consensus about what is right or wrong in a given context. By presenting an issue in terms of rights, human rights groups help the public to develop a moral framework for assessing governmental conduct beyond public sentiment in any particular case or incident.

For the law to play this role of moral instruction, it is not enough simply to recite it. When people’s security or traditions are at stake, it takes more than a mere reference to the law to change the public’s sense of moral propriety. Human rights groups must be creative in moving the public to embrace what the law demands.

Sometimes it is difficult to convince a local public to disapprove of its government’s conduct. Thus, the great challenge facing human rights groups is often less concerned with arguing the law’s fine points or applying them to the facts of a case than with convincing the public that violations are wrong. That requires the hard work of helping the public to identify with the victim’s plight, making the law come alive, and generating outrage at its violation with some public of relevance. When human rights law can be made to correspond with the public’s sense of right and wrong, governments face intense pressure to respect that law. Shame can be a powerful motivator.

Headline image credit: Hands raised. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Kenneth Roth on human rights appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAcross the spectrum of human rightsNavanethem Pillay on what are human rights forWhy are structural reforms so difficult?

Related StoriesAcross the spectrum of human rightsNavanethem Pillay on what are human rights forWhy are structural reforms so difficult?

Across the spectrum of human rights

What are the ties that bind us together? How can we as a global community share the same ideals and values? In celebration of Human Rights Day, we have asked some key thinkers in human rights law to share stories about their experiences of working in this field, and the ways in which they determined their specific focuses.

* * * * *

“My area of research is complementary forms of international protection, which is where international refugee law and international human rights law merge. Since the beginning of time, there has been an element of compassion in customary and religious norms justifying the acceptance of and assistance to persons banned from their communities or forced to leave their homes for reasons of poverty, natural disasters, or other reasons outside their control. Based on a general conviction that the alleviation of suffering is a moral imperative, many industralized countries included in their domestic migration practice the possibility to grant residence permits to certain categories of persons, who seemingly fall outside their international obligations, but who they considered to deserve protection and assistance because of a sense that this is what humanity dictates. In the past twenty years, many of these categories have become regulated and categorized as beneficiaries of protection, either through a broad interpretation of the refugee concept or through the adoption of new legislation confirming the domestic practice of States, such as the EC Qualification Directive. I find this to be a fascinating area of international law because, it shows how human rights and the notion of ‘humanitarianism’ (i.e. reasons of compassion, charity or need) have generated legal obligations to protect and assist aliens outside their country of origin.”

— Liv Feijen, Doctoral Candidate in international law at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, and author of ‘Filling the Gaps? Subsidiary Protection and Non-EU Harmonized Protection Status(es) in the Nordic Countries’ in the International Journal of Refugee Law

* * * * *

“My work focuses on the forms and functions of the law when faced with contemporary mass crimes and their traces (testimony, archives, and the (dead) body). It questions the relationship between law, memory, history, science, and truth. To do so, I call into question the various legal mechanisms (traditional/alternative, judicial/extrajudicial) used in the treatment of mass crimes committed by the State and their heritage, especially at the heart of criminal justice (national and international), transitional justice, international human rights law, and constitutional law. In this context I have explored the close relationship between international criminal law and international human rights law. These two branches of law, that have distinct objects and goals, are linked by what they have in common: the protection of the individual. Their interaction culminated in the 90s when international criminal law, and in a larger sense transitional justice, boomed: an actual human rights turn took place with the strong mobilization of human rights in favour of the ‘fight against impunity’ of the gravest international crimes. At the heart of this human rights turn lays the consecration of a new human right, namely, the ‘right to the truth’, which is the object of my current research.”

— Sévane Garibian, Assistant Professor, University of Geneva, and lecturer, University of Neuchâtel, and author of ‘Ghosts Also Die: Resisting Disappearance through the ‘Right to the Truth’ and the Juicios por la Verdad in Argentina’ in the Journal of International Criminal Justice

* * * * *

“I decided early on to focus in my work on how rights perform when they are put under some kind of strain. That could be panic and fear emerging from a terrorist attack, or resource limitations at national or international level, or political structures that make effective enforcement of rights (un)feasible, for example. It seemed to me to be important to think about the resilience of the language and structures, as well as the law, of human rights because in the end of the day we rely on states to deliver rights in a meaningful way and this raises all sorts of challenges around legitimacy, will, embeddedness, international relations, domestic politics, legal systems, constitutional frameworks, and so on. These are factors that have to be accounted for when we think about what makes human rights law work as a means of ensuring human rights in practice; as a means of limiting the power of states to do as it wishes, regardless of the impact on individual and group welfare, dignity, and liberty. Thus, rather than specialise in any particular right per se, my interest is in frameworks of effective rights protection and understanding what makes them work, or makes them vulnerable, especially in times of strain or crisis.”

— Fiona de Londras, Professor of Law, Durham Law School, and author of ‘Declarations of Incompatibility Under the ECHR Act 2003: A Workable Transplant?’ in the Statute Law Review

* * * * *

“I have always been interested in the protection of individual rights from undue interference by executive authority. So, my scholarly roots arguably originate in classic social contractarianism. In my work, I have been mostly focusing on civil and political rights, whether in the context of constitutional law, criminal justice, or international (human rights) law. An important part of my research examines the (alleged) tension between ‘liberty’ and ‘security’ and explores how this tension plays out in both domestic and international contexts, often addressing the interface between the two dimensions. National security issues, such as terrorism, have featured prominently in my scholarship, but my human rights-related work also extends to the field of preventive justice, including questions relating to the post-sentence detention of ‘dangerous’ individuals for public safety purposes. A fascinating development that has captured my attention recently concerns the expansion of executive power of international organisations. International bodies such as the UN Security Council have become increasingly active in the administration and regulation of matters that once used to be the exclusive domain of States. This shift in governance functions, however, has not been accompanied by the creation of mechanisms to restrain or review the exercise of executive power. I suspect that it is in this area that much of my research will be carried out in the years ahead.”

— Christopher Michaelsen, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, UNSW Australia, member of Australian Human Rights Centre, and author of ‘Human Rights as Limits for the Security Council: A Matter of Substantive Law or Defining the Application of Proportionality?’ in the Journal of Conflict and Security Law

* * * * *

“I specialize in the interaction between international financial markets and human rights, both in relation to (a) understanding international legal obligations relating to socio-economic rights in the context of financial processes and dynamics; and (b) the business and human rights debate as it applies to financial institutions. My focus on these areas resulted from an awareness that as the world economy globalised over the last twenty years, the financial markets changed beyond all recognition to become a predominant force shaping economic processes. Therefore, although they are generally seen as remote from immediate human rights impacts, they set the context of socio-economic rights enjoyment. The practical challenges involved in realising these rights can only be fully understood by accepting the way financial markets shape economic and policy making options, and outcomes for individuals. As this is a huge field of enquiry and many of the connections have not so far been extensively explored from a human rights point of view, my focus tends to be determined by (a) a desire to bring new areas of the financial markets into a human rights framework, and (b) a desire to respond to issues of importance as they arise, such as financial crisis and austerity.”

— Mary Dowell-Jones, Fellow, Human Rights Law Centre, University of Nottingham, and author of ‘Financial Institutions and Human Rights’ in the Human Rights Law Review

* * * * *

“My research covers a variety of human rights issues, however I have a particular interest in the analysis of domestic violence as a human rights issue. Domestic violence affects vast numbers of people in every state around the globe. The practice of domestic violence constitutes a breach of internationally recognised rights such as the right to be free from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment; the right to private and family life; and, in some circumstances, the right to life itself. However it is only relatively recently that domestic violence has been analysed through the lens of human rights law. For example, it is only since 2007 that judgments of the European Court of Human Rights have been issued which directly focus on domestic violence. Nevertheless, there is now an ever-increasing awareness of domestic violence as a human rights issue, and there have been a number of important recent developments, such as the adoption of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, which entered into force on 1 August 2014.”

— Ronagh McQuigg, lecturer in School of Law, Queen’s University Belfast, and author of ‘The Human Rights Act 1998—Future Prospects’ in the Statute Law Review

* * * * *

“Human rights discourse has been proliferating. Yet I feel that the proliferation of the discourse of human rights does not contribute to the success of implementing human rights on the ground. Perhaps one reason is that human rights scholarship and activism has great appeal to idealists and while idealists whom I admire are good in articulating ideals, they are less capable of carrying out these ideals. I believe that a major difficulty in implementing human rights is the costs of implementation. Human rights organizations may be justifiably appalled by police brutality and urge states to restructure their police forces, but such a restructuring is not costless and it may be detrimental to other urgent concerns including human rights concerns. The good intentions of activists and the scholarly work of theorists (to which I have been committed in the past) may ultimately turn out to be detrimental to the protection of human rights. What I think is urgently needed in order to carry out the lofty ideals is not more human rights scholarship but scholarship which will focus its attention on the best ways to implement the most urgent and basic humanitarian concerns. This is not what I have been doing in my own work but I am convinced it is what needs at this stage to be done. In doing so one ought to constrain idealism in favor of modest pragmatism. Ironically those who can most effectively pursue modest pragmatism are not human rights activists or theorists.”

— Alon Harel, Professor in Law, Hebrew University Law Faculty and Center for Rationality, and author of ‘Human Rights and the Common Good: A Critique’ in the Jerusalem Review of Legal Studies

* * * * *

“It had long been assumed that the best protection of human rights was a strong, Western-style democracy – if it came to the test, the people would always decide in favour of human rights. Recent developments, however, have challenged this assumption: human rights restrictions introduced after 9/11 in the United States and other Western democracies had strong popular support; the current British government’s plans to weaken (or even withdraw from) the ECHR system seem primarily designed to gain votes; Swiss voters have approved several popular initiatives that conflict with international human rights guarantees. Is the relationship between democracy and human rights not as symbiotic as it is often thought? Do direct democratic systems lend themselves more to tyranny of the majority than representative democracies? What is needed so that the human rights of those in the minority can be effectively protected? These, I believe, are among the most pressing questions that human rights lawyers must confront today.”

— Daniel Moeckli, Assistant Professor of Public International Law and Constitutional Law, University of Zurich, co-editor of International Human Rights Law, Second Edition

* * * * *

Headline image credit: Canvas Orange by Raul Varela via the Pattern Library.

The post Across the spectrum of human rights appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNavanethem Pillay on what are human rights forHuman Rights Day: abolishing the death penaltyParental consent, the EU, and children as “digital natives”

Related StoriesNavanethem Pillay on what are human rights forHuman Rights Day: abolishing the death penaltyParental consent, the EU, and children as “digital natives”

Why are structural reforms so difficult?

In times of economic crisis, politicians and analysts alike are typically quick to call for structural reforms to stimulate economic growth. Job security regulations are often identified as a policy area in need of such reforms. These regulations restrict the managerial capacity to dismiss employees to allow for downsizing or to replace workers and use new forms of employment such as fixed-term contracts when hiring new workers. Mainstream economics typically blames such regulations for the sclerosis of European labour markets, in particular in southern Europe. But so far, European countries have mostly failed to reform dismissal protection – despite the economic crisis and pressure from international organizations. Why are these regulations so difficult to reform (i.e. dismantle)?

The easy answer is, of course, that some powerful groups, in particular trade unions, oppose these reforms. However, opposition to reform is costly, and unions have been under massive political pressure in recent years to assent to such structural reforms. Why are unions so adamantly opposed to structural reforms and in particular the reduction of dismissal protection in case of open-ended contracts? What is so special about these regulations?

Job security regulations are more important to trade unions than one might think at first sight. In fact, trade unions have at least three reasons to fight the reform of dismissal protection in case of open-ended contracts. The first reason is rather straightforward: unions need to represent their members’ interest in statutory dismissal protection. The two other reasons, however, are often overlooked: unions have an organizational interest in retaining dismissal protection because these regulations prevent employers hostile to trade unions from singling out union members in workforce reductions. Put differently, protection against arbitrary dismissal also involves the protection of the local union organization against anti-union employers. In addition, unions have an interest in protecting their involvement in the administration of dismissals because this involvement allows them to influence management decisions at the company level. In many countries, job security regulations give trade unions important co-decision rights in case of dismissals (e.g. Swedish regulations award unions the right to co-decide the selection of workers in case of dismissals for economic reasons). Put simply, job security regulations often make unions relevant actors in the workplace.

The Apprentice: you’re fired? by Adam Foster. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via flickr

The Apprentice: you’re fired? by Adam Foster. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via flickrOf course, these three reasons don’t have the same weight in all European countries. For instance, the fear of employers hostile to unions is probably more important in southern European countries characterized by conflictual industrial relations (in most of these countries, employers were not required to recognize local union representations before the 1970s), while the involvement in the administration of dismissals is particularly important in countries characterized by long traditions of cooperative industrial relations (e.g. Germany and Sweden). Everywhere though, unions have sufficient reason to fight any reform of dismissal protection.

Facing such union resistance, governments have typically resorted to the deregulation of temporary employment. Unions have been more accepting of such two-tier reforms because temporarily employed workers are underrepresented among the union rank-and-file and because in the case of temporary employment unions have no organizational interests to defend. The deregulation of temporary employment (while the protection awarded to workers on open-ended contracts has remained more or less constant) has become a prominent example of so-called dualization processes, which are characterized by a differential treatment of workers in standard employment relationships (‘insiders’) and workers in more precarious employment relationships (‘outsiders’). Arguably, in some countries like Italy, the share of workers benefitting from (overly?) strict dismissal protection is now lower than the share of workers benefitting from hardly any dismissal protection at all.

So where are we standing after about three decades of calls for structural reforms such as the deregulation of job security? The three aforementioned reasons for unions to oppose the reform of dismissal protection in case of open-ended contracts are still there. The average union member still benefits from these regulations, unions continue to be worried about employers taking advantage of collective dismissals to rid themselves of unionized workers, and the institutional involvement in the administration of dismissals continues to be an important source of union power – in particular in times of dwindling membership.

Today, however, unions have a fourth reason to oppose structural reforms. For three decades they have reluctantly assented to two-tier reforms only to be confronted with further calls for numerical flexibility. By now there are as many workers on precarious contracts as there are workers on regular open-ended contracts – in particular in the countries that are said to be in greatest need of structural reforms. Nevertheless, calls for reform focus almost exclusively on dismissal protection of workers on open-ended contracts rather than on measures to improve the lot of the disadvantaged young, women, or elderly on precarious contracts. You don’t have to be a radical Italian trade unionist to find this one-sidedness a little bit odd.

The post Why are structural reforms so difficult? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTouchy-feely politicsJohn Boyd and Sun Tzu’s The Art of WarThe Lerner Letters: Part 1 – The Stars

Related StoriesTouchy-feely politicsJohn Boyd and Sun Tzu’s The Art of WarThe Lerner Letters: Part 1 – The Stars

Christmas crime films

In order to spread some festive cheer, Blackstone’s Policing has compiled a watchlist of some of the best criminal Christmas films. From a child inadvertently left home alone to a cop with a vested interest, and from a vigilante superhero to a degenerate pair of blaggers, it seems that (in Hollywood at least) there’s something about this time of year that calls for a special kind of policing. So let’s take a look at some of Tinseltown’s most arresting Christmas films:

1. Die Hard, directed by John McTiernan, 1988

Considered by many to be one of the greatest action/Christmas films of all time, Die Hard remains the definitive cinematic alternative to the usual saccharine cookie-cut Christmas film offering. This is the infinitely watchable story of officer John McClane’s Christmas from hell. When a trip to win back his estranged wife goes awry and he unwittingly finds himself amidst an international terrorist plot, he must find a way to save the day armed only with a few guns, a walkie talkie, and a bloodied vest. With firefights and exploding fairy lights abundant, this Bruce Willis tour de force is the undisputed paragon of policing in Christmas films.

2. Home Alone, directed by Chris Columbus, 1990

In a parental blunder tantamount to criminal neglect, the McCallister family accidentally leave their youngest member, Kevin (played by precocious child star Macaulay Culkin), ‘home alone’ to fend for himself over Christmas as two omnishambolic burglars target the McCallister household. As the Chicago Police Department work through the confusion of the situation, Kevin traverses his way through a far from silent night. Cue copious booby traps and slapstick as the imagination of an eight-year-old boy ingeniously holds the line in this family-fun classic.

3. Batman Returns, directed by Tim Burton, 1992

Gotham is a city perennially infested with arch-criminals whose seemingly endless financial resources demand that they be tackled head-on by a force who can match them pound-for-pound (or dollar-for-dollar, if you prefer). Enter Gotham’s very own Christmas miracle: billionaire Bruce Wayne and his vigilante alter ego Batman (Michael Keaton), who provides a singular justice-hungry scourge against the criminal underworld. As the Penguin (Danny DeVito) hatches a nefarious plot which threatens the city, Batman’s wholly goodwill must prove resilient. Though director Tim Burton went on to make The Nightmare Before Christmas the following year, Batman Returns itself is hardly a Christmas classic.

4. Lethal Weapon, directed by Richard Donner, 1987

Ward Bond (1903-1960) as Bert the cop in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) by Insomnia Cured Here. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Ward Bond (1903-1960) as Bert the cop in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) by Insomnia Cured Here. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.With a blizzard of bullets and completely bereft of snow, LA-based Lethal Weapon lacks nearly all the usual trimmings of a Christmas film. Seasoned detective Roger Murtaugh (Danny Glover) is close to retirement when he’s paired with the young (and morose) Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson) to tackle a drug smuggling gang. As their stormy investigation progresses, Murtaugh and Riggs’ unlikely union flourishes into a double-act worthy of Donner and Blitzen (and, judging by the pair’s return in a subsequent three installments of the series, their entertaining policing partnership always leaves audiences wanting myrrh…).

5. National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, directed by Jeremiah Chechik, 1989

In this third installment of the Griswold family’s catastrophic holidays, Clark (Chevy Chase) navigates his way through the perils of yet another disastrous calamity, but at least this time he has his Christmas bonus to look forward to. Things take a bizarre turn for the criminal when the bonus isn’t forthcoming, resulting in a myriad of mishaps of Christmas paraphernalia and SWAT teams. As the tagline for the film attests, ‘Yule crack up!’

6. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, directed by Shane Black, 2005

Petty thief Harry Lockhart (Robert Downey Jr.) finds himself embroiled in a series of increasingly byzantine cases of mistaken identity as both a method actor and criminal investigator. Reality cuts through when Harry is shepherded into a murder investigation involving the sister of his childhood crush, Harmony Lane (Michelle Monaghan). Perhaps one of the less christmassy films on this list, there are definitely still a few seasonal signs parceled in to this murder/mystery thriller.

“There’s something about this time of year that calls for a special kind of policing”

7. Miracle on 34th Street, directed by George Seaton, 1947

Arguably the ultimate Christmas film, Miracle on 34th Street is the classic tale of the legal battle around the sanity and freedom of a man who claims to be the real Santa Claus. This original film won three Academy Awards including Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Edmund Gwenn’s portrayal of Kris Kringle (‘the real Santa Claus’). Despite being remade in 1994 and adapted into various other forms, the 1947 version remains the quintessential Christmas film which no comprehensive watchlist could be without.

8. Bad Santa, directed by Terry Zwigoff, 2003

Dastardly duo Willie (Billy Bob Thornton) and Marcus (Tony Cox) make their criminal living by posing as Santa and his Little Helper for department stores, and then opportunistically stealing as much as they can. As the security team for their latest blag hunts them down, Willie meets a boy determined that he is the real Santa and the race is on for the degenerate pair to reform their lifestyles before they are stuffed.

What would would you add to this list? Tell us your favourite policing Christmas film in the comments section below or let us know directly on Twitter. Merry Christmas everyone!

Headline image credit: [365 Toy Project: 019/365] Batman: Scarlet Part 1. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Christmas crime films appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIntersections of documentary and avant-garde filmmakingScoring loss across the multimedia universeThe Jerk Store called…and called and called

Related StoriesIntersections of documentary and avant-garde filmmakingScoring loss across the multimedia universeThe Jerk Store called…and called and called

December 9, 2014

Human Rights Day: abolishing the death penalty

Every year, on December 10, UN Human Rights Day commemorates the day in 1948 on which the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Although the Declaration itself said nothing about the death penalty, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) that incorporated its values in 1966 made it clear in Article 6(6) that ‘nothing … should be invoked to delay or to prevent the abolition of capital punishment by any State Party to the … Covenant,’ which now has been ratified by all but a handful of nations.

Today, we pause to consider the considerable changes that have taken place in the use of capital punishment around the world over the past quarter of a century, changes which have shifted our pessimism – believing that in many regions of the world there was little hope of worldwide abolition occurring soon – towards increasing optimism. Since the end of 1988, the number of actively retentionist countries (by which we mean countries that have carried out judicial executions in the past 10 years) has declined from 101 to 39, while the number that has completely abolished the death penalty has almost trebled from 35 to 99; a further seven are abolitionist for all ordinary crimes and 33 are regarded as abolitionist in practice: 139 in all. In 2013 only 22 countries were known to have carried out an execution and the number that regularly executes a substantial number of its citizens has dwindled. Only seven nations executed an average of 20 people or more over the five year period from 2009 to 2013: China (by far the largest number), Iran (the highest per head of population), Iraq, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Yemen. The change has been truly remarkable. Indeed, we have witnessed and recorded a revolution in the discourse on and practice of capital punishment since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

We have witnessed and recorded a revolution in the discourse on and practice of capital punishment since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

This year’s Human Rights Day slogan – Human Rights 365 – encompasses the idea that every day is Human Rights Day. It celebrates the fundamental proposition in the Universal Declaration that each one of us, everywhere, at all times is entitled to the full range of human rights, that human rights belong equally to each of us and bind us together as a global community with the same ideals and values. What better day then to reflect on the dynamo for this new wave of abolition – the development of international human rights law and norms.

Arising in the aftermath of the Second World War and linked to the emergence of countries from totalitarian imperialism and colonialism, the acceptance of international human rights principles transformed consideration of capital punishment from an issue to be decided solely or mainly as an aspect of national criminal justice policy to the status of a fundamental violation of human rights: not only the right to not to be arbitrarily deprived of life but the right to be free from cruel, inhuman, or degrading punishment or treatment. The idea that each nation has the sovereign right to retain the death penalty as a repressive tool of its domestic criminal justice system on the grounds of its purported deterrent utility or the cultural preferences and expectations of its citizens was being replaced by a growing acceptance that countries that retain the death penalty – however they administer it – inevitably violate universally accepted human rights.

A prison cell in Kilmainham Gaol. Photo by Aapo Haapanen. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

A prison cell in Kilmainham Gaol. Photo by Aapo Haapanen. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The human rights dynamic has not only resulted in fewer countries retaining the death penalty on their books, but also in the declining use of the ultimate penalty in many of those countries. Since the introduction of Safeguards Guaranteeing Protection of the Rights of those Facing the Death Penalty, which were first promulgated by the UN Economic and Social Council resolution 1984/50 and adopted by the General Assembly 30 years ago, there have been attempts to progressively restrict the use of capital punishment to the most heinous offences and the most culpable offenders and various measures to try to ensure that the death penalty is only applied where and when defendants have had access to a fair and safe criminal process. Hence, in many retentionist countries juveniles, the mentally ill, and the learning disabled are exempt from capital punishment, and some countries restrict the death penalty to culpable homicide.

There has been some strong resistance to the political movement to force change ever since the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1989. Attempts by the abolitionist nations at United Nations Congresses, in the General Assembly, beginning in 1994, and at the Commission on Human Rights, annually from 1997, to press for a resolution calling for a moratorium on the imposition of death sentences and executions met with hostility from many of the retentionist nations. By 2005, when an attempt had been made at the Commission on Human Rights to secure sufficient support to bring such a resolution before the United Nations, it had been opposed by 66 countries on the grounds that there was no international consensus that capital punishment should be abolished. Since then, as the resolution has been successfully brought before the General Assembly, the opposition has weakened as each subsequent vote was taken in 2007, 2008, 2010, and 2012, when 111 countries (60 per cent) voted in favour and 41 against. Just three weeks ago, 114 of the UN’s 193 member states voted in favour of the resolution which will go before the General Assembly Plenary for final adoption this month. The notion behind Human Rights 365 – that we are a part of a global community of shared values – is reflected in this increasing support for a worldwide moratorium as a further step towards worldwide abolition. We encourage all those who believe in human rights to continue working towards this ideal.

Headline image credit: Sparrow on barbed wire. Photo by See-ming Lee. CC BY 2.0 via seeminglee Flickr.

The post Human Rights Day: abolishing the death penalty appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesParental consent, the EU, and children as “digital natives”John Boyd and Sun Tzu’s The Art of WarWhy Republican governors embrace Obamacare

Related StoriesParental consent, the EU, and children as “digital natives”John Boyd and Sun Tzu’s The Art of WarWhy Republican governors embrace Obamacare

John Boyd and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War

Renowned US military strategist John Boyd is famous for his signature OODA (Observe-Orientation-Decision-Action) loop, which significantly affected the way that the West approached combat operations and has since been appropriated for use in the business world and even in sports. Boyd wrote to convince people that the Western military doctrine and practice of his day was fundamentally flawed. With this goal in mind, he naturally turned to the East to seek an alternative.

Sun Tzu: The Art of War happened to be the only theoretical book on war that Boyd did not find imperfect; it became his Rosetta stone. Boyd eventually owned seven translations of The Art of War, each with long passages underlined and with copious marginalia. He was at the same time familiar with Taoism (Lao Tzu mainly) and Miyamoto Musashi (a famous Japanese swordsman who practiced Samurai Zen). With this extensive knowledge of Eastern thought, Boyd aimed for an almost full adoption of Sun Tzu’s theory into the Western strategic framework. The theory of Sun Tzu was foreign to his audience’s way of thinking, so in order to convince them of its value he repackaged, rationalized, and modernized Eastern theories using various scientific theories from the West.

Why couldn’t such an adoption take place using existing translations of The Art of War? Boyd understood that he could get nowhere close to the heart of Chinese strategy without first understanding the cognitive and philosophical foundations behind Chinese strategic thought. These foundations are usually lost in translation, causing an impasse in understanding the Chinese strategy that remains today. Hence Boyd made use of new sciences to illuminate what the West had been unable to illuminate before.

For instance, Boyd recreated the naturalistic worldview of Chinese strategy in the Western framework. From this perspective, the OODA loop encompasses much more than a four-phase decision-making model: its real significance is that it reconstructs mental operations based on intuitive thinking and judgment. This kind of intuition is pivotal to strategy and strategic thinking, but was lost as the West embraced a more rational scientific mindset. It is an open secret that the speed and success of the OODA loop comes from a deep intuitive understanding of one’s relationship to the rapidly changing environment. This understanding of one’s environment comes directly from Chinese strategic thought.

Chinese warrior. CC0 via Pixabay.

Chinese warrior. CC0 via Pixabay.Another aspect of Chinese strategic thought that Boyd insisted on capturing and incorporating into the Western strategic framework is yin-yang (yin and yang). Yin-yang has been commonly misunderstood as the Chinese equivalent of “contradictions” in the West. Yin-yang, however, is not considered contradictory or paradoxical by the Chinese, but is actively used to resolve real-life contradictions and paradoxes—the key is to see yin-yang (such as win-lose, enemy-friend, strong-weak) as one concept or continuum, not two opposites. It is this Chinese philosophical and logical concept that forms the strategic chain linking Sun Tzu, Lao Tzu, and Mao Zedong.

Once this “oneness” of things is realized, a strategist will then be able to tap into the valuable strategic information it carries, including the dynamics of situations and relationships between things, resulting in a more complete grasp of a situation, particularly in complex and multifaceted phenomena like war. In short, yin-yang provides an intuitive means for understanding the essence of reality, opening a new door to strategic insights and forecasts that were once inaccessible by using Western methods.

Boyd’s thesis is not a general theory of war but, as one of his biographers noted, a general theory of the strategic behavior of complex adaptive systems in adversarial conditions. It is ironic that the scientific terminology used illustrates the systemic thinking behind Chinese strategic thought applied by Sun Tzu 2,500 years ago, as the terminology of complex adaptive systems and non-linearity did not exist then.

Boyd opened a crucial window of opportunity for Western thought by repackaging and rationalizing Eastern thought. His attempt to adopt Sun Tzu into the Western strategic framework was far from being successful, and many of his proposals have gone unnoticed, but nonetheless Boyd made very significant progress in “synchronizing” Chinese and Western strategy. Once the West grasps the significance behind this unprecedented opportunity to directly absorb and adopt elements of Chinese strategy, it will open many new avenues for the development and self-rectification of Western strategic thought and practices.

The post John Boyd and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Lerner Letters: Part 1 – The StarsChristmas for a nonbelieverScoring loss across the multimedia universe

Related StoriesThe Lerner Letters: Part 1 – The StarsChristmas for a nonbelieverScoring loss across the multimedia universe

Scoring loss across the multimedia universe

Well known is music’s power to stir emotions; less well known is that the stirring of specific emotions can result from the use of very simple yet still characteristic music. Consider the music that accompanies this sweet, sorrowful conclusion of pop culture’s latest cinematic saga.

When the on-set footage begins, so does some soft music that is rather uncomplicated because, in part, it simply alternates between two chords which last about four seconds each. These two chords are shown on the keyboard below. In classical as well as pop music, these two chords typically do not alternate with one another like this. Although the music for this featurette eventually makes room for other chords, the musical message of the more distinctive opening has clearly been sent, and it apparently worked on this blogger, who admits to shedding a few tears and recommends the viewer have a tissue nearby.

This simple progression has been used to accompany loss-induced sadness in numerous mainstream (mostly Hollywood) cinematic scenes for nearly 30 years. This association is not simply confined to movies, yet inhabits a larger media universe. For example, while the pop song “Comeback Story” by Kings of Leon, which opens this movie’s trailer, helps to convey the genre of the advertised product, the same two-chord progression—let’s call it the “loss gesture”—highlights the establishing narrative: a patriarchal death has brought a mourning family together (for comedic and sentimental results).

Loss gestures can play upon one’s heartstrings less discriminately; they can elicit both tears of joy as well as tears of sadness. Climaxes in Dreamer and Invincible, both underdog-comes-from-behind movies, are punctuated with loss gestures. As demonstrated at 2:06 in the following video, someone employed by the Republican Party appears to be keenly aware of this simple progression’s powerful capacity for moving a viewer (and potential voter).

Within the universe of contemporary media, the loss gesture has been used in radio as well. The interlude music that plays before or after a story on National Public Radio often has some relation to the content of the story. A week after the Sandy Hook school shootings, NPR aired a story by Kirk Siegler entitled “Newtown Copes With Grief, Searches For Answers.” Immediately after the story’s poignant but hopeful ending, the opening of Dustin O’Halloran’s “Opus 14” faded in, musically encapsulating the emotions of the moment.

How the loss gesture works its magic on listeners is a Gordian knot. However, it is undeniable that producers from several different corners of the media world know that the loss gesture works.

The post Scoring loss across the multimedia universe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesParental consent, the EU, and children as “digital natives”Why Republican governors embrace ObamacareGary King: an update on Dataverse

Related StoriesParental consent, the EU, and children as “digital natives”Why Republican governors embrace ObamacareGary King: an update on Dataverse

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers