Oxford University Press's Blog, page 722

December 18, 2014

Dependent variables: a brief look at online gaming addictions

Over the last 15 years, research into various online addictions has greatly increased. Prior to the 2013 publication of the American Psychiatric Association’s fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), there had been some debate as to whether ‘Internet addiction’ should be introduced into the text as a separate disorder. Alongside this, there has been debate as to whether those in the online addiction field should be researching generalized Internet use and/or the potentially addictive activities that can be engaged on the Internet (e.g. gambling, video gaming, sex, shopping, etc.).

It should also be noted that given the lack of consensus as to whether video game addiction exists and/or whether the term ‘addiction’ is the most appropriate to use, some researchers have instead used terminology such as ‘excessive’ or ‘problematic’ to denote the harmful use of video games. Terminology for what appears to be for the same disorder and/or its consequences include problem video game playing, problematic online game use, video game addiction, online gaming addiction, Internet gaming addiction, and compulsive Internet use.

Following these debates, the Substance Use Disorder Work Group (SUDWG) recommended that the DSM-5 include a sub-type of problematic Internet use (i.e. Internet gaming disorder (IGD)) in Section 3 (‘Emerging Measures and Models’) as an area that needed future research before being included in future editions of the DSM. According to Dr. Nancy Petry and Dr. Charles O’Brien, IGD will not be included as a separate mental disorder until the

(i) defining features of IGD have been identified, (ii) reliability and validity of specific IGD criteria have been obtained cross-culturally, (iii) prevalence rates have been determined in representative epidemiological samples across the world, and (iv) etiology and associated biological features have been evaluated. Video game controller. CC0 via Pixabay.

Video game controller. CC0 via Pixabay. Although there is now a rapidly growing literature on pathological video gaming, one of the key reasons that Internet gaming disorder was not included in the main text of the DSM-5 was that the Substance Use Disorder Work Group concluded that no standard diagnostic criteria were used to assess gaming addiction across these studies. In 2013, some of my colleagues and I published a paper in Clinical Psychology Review examining all instruments assessing problematic, pathological, and/or addictive gaming. We reported that 18 different screening instruments had been developed, and that these had been used in 63 quantitative studies comprising 58,415 participants. The prevalence rates for problematic gaming were highly variable depending on age (e.g. children, adolescents, young adults, older adults) and sample (e.g. college students, Internet users, gamers, etc.). Most studies’ prevalence rates of problematic gaming ranged between 1% and 10%, but higher figures have been reported (particularly amongst self-selected samples of video gamers). In our review, we also identified both strengths and weaknesses of these instruments.

The main strengths of the instrumentation included the:

(i) the brevity and ease of scoring, (ii) excellent psychometric properties such as convergent validity and internal consistency, and (iii) robust data that will aid the development of standardized norms for adolescent populations.However, the main weaknesses identified in the instrumentation included:

(i) core addiction indicators being inconsistent across studies, (ii) a general lack of any temporal dimension, (iii) inconsistent cut-off scores relating to clinical status, (iv) poor and/or inadequate inter-rater reliability and predictive validity, and (v) inconsistent and/or dimensionality.It has also been noted by many researchers (including me) that the criteria for Internet gaming disorder assessment tools are theoretically based on a variety of different potentially problematic activities including substance use disorders, pathological gambling, and/or other behavioral addiction criteria. There are also issues surrounding the settings in which diagnostic screens are used, as those used in clinical practice settings may require a different emphasis that those used in epidemiological, experimental, and neurobiological research settings.

Video gaming that is problematic, pathological, and/or addictive lacks a widely accepted definition. Some researchers in the field consider video games as the starting point for examining the characteristics of this specific disorder, while others consider the Internet as the main platform that unites different addictive Internet activities, including online games. My colleagues and I have begun to make an effort to integrate both approaches, i.e., classifying online gaming addiction as a sub-type of video game addiction but acknowledging that some situational and structural characteristics of the Internet may facilitate addictive tendencies (e.g. accessibility, anonymity, affordability, disinhibition, etc.).

© FelixRenaud via iStock.

© FelixRenaud via iStock. Throughout my career I have argued that although all addictions have particular and idiosyncratic characteristics, they share more commonalities than differences (i.e. salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, conflict, and relapse), and likely reflects a common etiology of addictive behavior. When I started research Internet addiction in the mid-1990s, I came to the view that there is a fundamental difference between addiction to the Internet, and addictions on the Internet. However, many online games (such as Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games) differ from traditional stand-alone video games as there are social and/or role-playing dimension that allow interaction with other gamers.

Irrespective of approach or model, the components and dimensions that comprise online gaming addiction outlined above are very similar to the Internet gaming disorder criteria in Section 3 of the DSM-5. For instance, my six addiction components directly map onto the nine proposed criteria for IGD (of which five or more need to be endorsed and resulting in clinically significant impairment). More specifically:

preoccupation with Internet games [salience]; withdrawal symptoms when Internet gaming is taken away [withdrawal]; the need to spend increasing amounts of time engaged in Internet gaming [tolerance], unsuccessful attempts to control participation in Internet gaming [relapse/loss of control]; loss of interest in hobbies and entertainment as a result of, and with the exception of, Internet gaming [conflict]; continued excessive use of Internet games despite knowledge of psychosocial problems [conflict]; deception of family members, therapists, or others regarding the amount of Internet gaming [conflict]; use of the Internet gaming to escape or relieve a negative mood [mood modification]; and loss of a significant relationship, job, or educational or career opportunity because of participation in Internet games [conflict].The fact that Internet gaming disorder was included in Section 3 of the DSM-5 appears to have been well received by researchers and clinicians in the gaming addiction field (and by those individuals that have sought treatment for such disorders and had their experiences psychiatrically validated and feel less stigmatized). However, for IGD to be included in the section on ‘Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders’ along with ‘Gambling Disorder’, the gaming addiction field must unite and start using the same assessment measures so that comparisons can be made across different demographic groups and different cultures.

For epidemiological purposes, my research colleagues and I have asserted that the most appropriate measures in assessing problematic online use (including Internet gaming) should meet six requirements. Such an instrument should have:

(i) brevity (to make surveys as short as possible and help overcome question fatigue); (ii) comprehensiveness (to examine all core aspects of problematic gaming as possible); (iii) reliability and validity across age groups (e.g. adolescents vs. adults); (iv) reliability and validity across data collection methods (e.g. online, face-to-face interview, paper-and-pencil); (v) cross-cultural reliability and validity; and (vi) clinical validation.We also reached the conclusion that an ideal assessment instrument should serve as the basis for defining adequate cut-off scores in terms of both specificity and sensitivity.

The good news is that research in the gaming addiction field does appear to be reaching an emerging consensus. There have also been over 20 studies using neuroimaging techniques (such as functional magnetic resonance imaging) indicating that generalized Internet addiction and online gaming addiction share neurobiological similarities with more traditional addictions. However, it is critical that a unified approach to assessment of Internet gaming disorder is urgently needed as this is the only way that there will be a strong empirical and scientific basis for IGD to be included in the next DSM.

The post Dependent variables: a brief look at online gaming addictions appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGiving the gift of well-beingScorpion Bombs: the rest of the storyMoping on a broomstick

Related StoriesGiving the gift of well-beingScorpion Bombs: the rest of the storyMoping on a broomstick

Why do politicians break their promises on migration?

Immigration policies in the US and UK look very different right now. Barack Obama is painting immigration as part of the American dream, and forcing executive action to protect five million unauthorized immigrants from deportation. Meanwhile, David Cameron’s government is treating immigration “like a disease”, vowing to cut net migration “to the tens of thousands” and sending around posters saying “go home”. US immigration policies appear radically open while UK policies appear radically closed.

But beneath appearances there is a strikingly symmetrical gap between talk and action in both places. While courageously defying Congress to protect Mexico’s huddled masses, Obama is also presiding over a “formidable immigration enforcement machinery”, which consumes more federal dollars than all other law enforcement agencies combined, detains more unauthorized immigrants than inmates in all federal prisons, and has already deported millions.

While talking tough, the UK government remains even more open to immigration than most classic settler societies: it switched from open Imperial borders to open EU borders without evolving a modern migration management system in the interim. Net migration is beyond government control because emigration and EU migration cannot be hindered, family migrants can appeal to the courts, and foreign workers and students are economically needed.

So these debates are mirror images: the US is talking open while acting closed; the UK is talking closed but acting open. What explains this pattern? The different talk is no mystery: Obama’s Democrats lean Left while Cameron’s Conservatives lean Right. But this cannot explain the gaps between talk and action. These are related to another political division that cuts across the left-right spectrum: the division between “Open and Closed”.

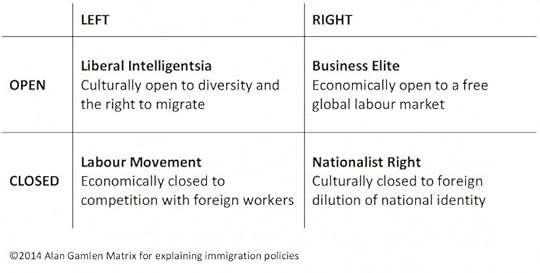

Different party factions have different reasons for being open or closed to immigration. On the Left, the Liberal Intelligentsia is culturally open, valuing diversity and minority rights, while the Labour Movement is economically closed, fearing immigration will undermine wages and working conditions. On the Right, the Business Elite is economically open to cheap and pliable migrant labour, while the Nationalist Right is culturally closed to immigration, fearing it dilutes national identity. Left and Right were once the markers of class, but now your education, accent and address only indicate whether you’re Open or Closed.

Image used with permission.

Image used with permission. Sympathetic talk can often satisfy culturally motivated supporters, but economic interest groups demand more concrete action in the opposite direction. So, a right-leaning leader may talk tough to appease the Nationalist Right, but keep actual policies more open to please the Business Elite. A left-leaning leader may talk open to arouse the Liberal Intelligentsia, but act more closed so as to soothe the Labour Movement. These two-track strategies can unite party factions, and even appeal to “strange bedfellows” across the aisle.

US and UK immigration debates illustrate this pattern. The UK government always knew it would miss its net migration target: its own 2011 impact assessments predicted making about half the promised reductions. This must have reassured Business Elites, who monitor such signals. Meanwhile for the Nationalist Right it’s enough to have “a governing party committed to reducing net migration” as “a longer term objective”. It’s the thought that counts for these easygoing fellows.

So, the Conservatives’ net migration targets are failing rather successfully. The clearest beneficiary is UKIP – a more natural Tory sidekick than the Lib Dems, and one which, by straddling the Closed end of the spectrum, siphons substantial support from the Labour Movement. Almost half the UK electorate supports the Tories or UKIP; together they easily dominate the divided Left which, by aping the old Tory One Nation slogan, offers nothing concrete to the Labour Movement, and disappoints the Liberal Intelligentsia, who ask, ‘Why doesn’t a man with Miliband’s refugee background stand up for what’s right?’

Maybe Miliband should have followed Barack Obama instead of David Cameron. Obama knows that the thought also counts for America’s Liberal Intelligentsia. For example, Paul Krugman writes, “Today’s immigrants are the same, in aspiration and behavior, as my grandparents were — people seeking a better life, and by and large finding it. That’s why I enthusiastically support President Obama’s new immigration initiative. It’s a simple matter of human decency.”

It’s also a simple matter of political pragmatism. Hispanics will comprise 30% of all Americans by 2050; many of those protected today are their parents. Both parties know this but the Democrats are more motivated by it. They have won amongst Hispanic voters in every presidential election in living memory, often with 60-80% majorities: losing Hispanic voters would be game changing. But the Republicans just can’t bring themselves to let Obama win by passing comprehensive immigration reform. Just spite the face now: worry about sewing the nose back on later.

Obama’s actions secure the Hispanic vote, but more importantly they pacify the Labour Movement. Milton Friedman once argued that immigration benefits America’s economy as long as it’s illegal. For ‘economy’ read ‘employers’, who want workers they can hire and fire at will without paying for costly minimum wages or working conditions. In other words, Friedman liked unauthorized immigration because he thought it undermined everything the Labour Movement believes in. No wonder the unions hated him: he was a red flag to a bull.

Luckily Obama’s actions don’t protect ‘illegal immigrants’. Those protected have not migrated for over five years, long enough for someone to become a full citizen in most countries, the US included. They are not immigrants anymore, but unauthorized residents. And once they’re authorized, they’ll just be plain old workers: no longer enemies of the Labour Movement, but souls ripe for conversion to it. For the real immigrants, the velvet glove comes off, and an iron-fisted border force instills mortal dread in anyone whose dreams of being exploited in the First World might threaten US health and safety procedures. To be clear, Obama’s actions protect the resident labour force from unauthorized immigration.

So, Obama’s talk-open-act-closed strategy is working quite nicely for the Democrats, throwing a bone to the Labour Movement while massaging the conscience of the Liberal Intelligentsia – and even courting the Business Elite, who would rather not break the law just by giving jobs to people who want them. So even if they don’t revive Obama’s standing, the executive orders are a shot in the arm for the Democrats. It’s Hillary’s race to lose in 2016 (although come to think of it, that’s what The Economist said during the 2007 primaries…).

In sum: the politics of international migration reveal a new political landscape that cannot be captured by the old categories of Left and Right. Governments on both sides of the Atlantic are talking one way on immigration but acting another, so as to satisfy conflicting demands from Open and Closed party factions while wooing their opponents’ supporters.

So are Left and Right parties dinosaurs? Not necessarily. Things may look different in countries with more parties, but I suspect that the four factions outlined above will crop up even in countries led by multi-party coalitions. We need more studies to know – if this framework works in your country, I’d be interested to hear. Another interesting challenge is to understand how these patterns relate to the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment – a question touched on by a recent special issue of Migration Studies.

To commemorate International Migrants Day this year, OUP have compiled scholarly papers examining human migration in all its manifestations, from across our law and social science journals. The highly topical articles featured in this collection are freely available for a limited time.

Featured image credit: Immigration at Ellis Island, 1900. By the Brown Brothers, Department of the Treasury. Records of the Public Health Service. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why do politicians break their promises on migration? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGary King: an update on DataverseThe other torture reportThe English question: a Burkean response?

Related StoriesGary King: an update on DataverseThe other torture reportThe English question: a Burkean response?

December 17, 2014

Scorpion Bombs: the rest of the story

The world recently learned that the Islamic State in Iraq (ISIS) has resurrected a biological weapon from the second century. Scorpion bombs are being lobbed into towns and villages to terrorize the inhabitants. As the story goes, this tactic was used almost 2,000 years ago against the desert stronghold of Hatra which was once a powerful, walled city 50 miles southwest of Mosul. But this historical interpretation might be just a bit too quick.

What we know from the writings of Herodian, who documented the ancient attacks by Hatrians on Roman invaders, is that the people crafted earthenware bombs loaded with “insects.” The favored hypothesis is that these devices were loaded with scorpions. And it’s true that these creatures (although not insects) were abundant in the desert. In fact, Persian kings offered bounties for these stinging arthropods to ensure the safe and pain-free passage of lucrative caravans through the region. But the local abundance of scorpions is not sufficient to draw a conclusion.

Scorpions tend toward cannibalism, so packing a bunch of these creatures into canisters for any period of time would have been (and presumably still is) a problem. According to an ancient writer, powdered monkshood could be used to sedate scorpions, although at high doses this plant extract is insecticidal (how ISIS solves this problem is not evident). But there’s another problem with the scorpion hypothesis.

A Syrian account of the siege of Hatra specified that the residents used “poisonous flying insects” to repulse the Romans. But, of course, scorpions don’t fly. One possibility is that the natural historians of yore were thinking of the scorpionfly (a flying insect in which the male genitalia curl over the back and resemble a scorpion’s tail), but these are small creatures are found in damp habitats, not deserts. Another possibility is that ancient reports of scorpions becoming airborne during high winds account for flying scorpions, although such a remarkable phenomenon hasn’t been reported by modern biologists. Finally, some scholars speculate that the clay bombshells were filled with assassin bugs, which can fly and deliver extremely painful bites.

Leiurus quinquestriatus, or deathstalker scorpion. Photo by Matt Reinbold. CC BY-SA 2.0 via furryscalyman Flickr.

Leiurus quinquestriatus, or deathstalker scorpion. Photo by Matt Reinbold. CC BY-SA 2.0 via furryscalyman Flickr. In the end, it seems likely that the Hatrian defenders and the ISIS militants latched onto the opportunities presented by the local arthropod fauna. But why would scorpions be so terrifying then or now? These creatures deliver a painful sting to be sure, but they are only rarely deadly. The responses of the Roman invaders and the Iranian townsfolk seem disproportionate to the consequences of being stung.

To understand why panic ensues when insects (or scorpions) rain down on a village, we must appreciate the evolutionary and cultural relationships between these creatures and the human mind. Our fear of insects and their relatives is rooted in six qualities of these little beasts—and scorpions score well.

First, our reaction arises from the capacity of these creatures to invade our homes and bodies. Scorpions, with their nocturnal activity and flattened bodies, are adept at slipping under doorsills and hiding in our shoes, closets, and furniture. Second, insects and their kin have the ability to evade us through quick, unpredictable movements. While scorpions might not skitter with the panache of cockroaches, they are still reasonably nimble. Third, many insects undergo rapid population growth and reach staggeringly large numbers which threaten our sense of individuality. While scorpions are not particulary prolific, having them scatter from exploding canisters (as described in the modern attacks), surely generates a sense of frightening abundance. Fourth, various arthropods can harm us both directly (biting and stinging) and indirectly (transmitting disease and destroying our property). Scorpions certainly qualify in the former sense, as they are well-prepared to deliver a dose of venom that elicits intense pain, sometimes accompanied by a slowed pulse, irregular breathing, convulsions—and occasionally, death. Fifth, insects and their relatives instill a disturbing sense of otherness with their alien bodies. Scorpions are hideously animalistic, even rather monstrous being like a demonic blending of a crab, spider, and a viper in terms of their form and function. Sixth, these creatures defy our will and control through a kind of depraved mindlessness or radical autonomy. Scorpions can appear to be like tiny robots, with their jointed bodies and legs taking them into the world without regard to fear or decency.Perhaps it is in this last sense that scorpions most resemble the ISIS assailants. Both seem to be predators, unconstrained by ethical constraints, maniacally and unreflectively seeking to satisfy their own bestial desires. Of course, we ought not to dehumanize our enemy—no matter how brutal his actions—by equating him with insects or their kin. (This rhetorical move has been made throughout history to justify horrible treatment of other people.) But perhaps this sense of amorality accounts for our fear of both ISIS and their unwitting, arthropod conscripts.

The post Scorpion Bombs: the rest of the story appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe other torture reportMoping on a broomstickGiving the gift of well-being

Related StoriesThe other torture reportMoping on a broomstickGiving the gift of well-being

Moping on a broomstick

One of the dialogues in Jonathan Swift’s work titled A complete Collection of Genteel and Ingenious Conversation (1738) runs as follows:

Neverout: Why, Miss, you are in a brown study, what’s the matter? Methinks you look like mumchance, that was hanged for saying nothing.

Miss: I’d have you know, I scorn your words.

Neverout: Well, but scornful dogs will eat dirty puddings.

Miss: My comfort is, your tongue is no slander. What! you would not have one be always on the high grin?

Neverout: Cry, Mapsticks, Madam; no Offence, I hope.

This is a delightfully polite conversation and a treasure house of idioms. To be in a brown study occupies a place of honor in my database of proverbial sayings (see a recent post on it). I am also familiar with scornful dogs will eat dirty puddings, but high grin made me think only of the high beam (and just for the record: mumchance is an old game of dice or “a dull silent person”). But what was Neverout trying to say at the end of the genteel exchange (see the italicized phrase)?

The first correspondent to Notes and Queries who wrote on the subject—and the problem was being thrashed out in the pages of Notes and Queries—suggested that it means “I ask pardon, I apologize for what I have said” (4 October 1856). Two weeks later, it was pointed out that mapsticks is a variant of mop-sticks, but no explanation followed this gloss. When fourteen years, rather than fourteen days, passed, someone sent another query to the same journal (8 May 1880), which ran as follows: “Like death on a mop-stick. How did this saying originate? I have heard it used by an old lady to describe her appearance on recovery from a long illness.” Joseph Wright did not miss the phrase and included it in his English Dialect Dictionary. His gloss was “to look very miserable.” Although the letter writer who used the pseudonym Mervarid and asked the question did not indicate where she lived, Wright located the saying in Warwickshire (the West Midlands). We will try to decipher the idiom and find out whether there is any connection between it and Swift’s mapsticks ~ mopsticks.

As could be expected, the OED has an entry on mopstick. The first citation is dated 1710 (from Swift!). In it the hyphenated mop-sticks means exactly what it should (a stick for a mop). The next one is from Genteel Conversation. Swift’s use of the word in 1738 received this comment: “Prob[ably] a humorous alteration of ‘I cry your mercy’.” This repeats the 1856 suggestion. After the Second World War, a four-volume supplement to the OED was published. The updated version of the entry contains references to the dialectal use of mopstick, a synonym for “leap-frog,” and includes such words pertaining to the game as Jack upon the mopstick and Johnny on the mopstick (the mopstick is evidently the player over whose back the other player is jumping), along with a single 1886 example of mopstick “idiot” (slang). The supplement did not discuss the derivation of the words included in the first edition. By contrast, the OED online pays great attention to etymology; yet mopstick has not been revised. I assume that no new information on its origin has come to light. In 1915 mopstick was used for “one who loafs around a cheap or barrel house and cleans the place for drinks” (US). This is a rather transparent metaphor. Mop would have been easier to understand than mopstick, but mopstick “idiot” makes it clear that despised people could always be called this. Johnny on the mopstick also refers to the inferior status of the player bending down. The numerous annotated editions of Swift’s works contain no new hypotheses; at most, they quote the OED.

I cannot explain the sentence in Genteel Conversation, but a few ideas occurred to me while I was reading the entries in the dictionaries. To begin with, I agree that Swift’s mapsticks is a variant of mopsticks, though it would be good to understand why Swift, who had acquired such a strong liking for mopsticks and first used the form with an o, chose a less obvious dialectal variant with an a. Second, I notice that the 1738 text has a comma between cry and mapsticks (Cry, Map-sticks, Madam…). Nearly all later editions probably take this comma for a misprint and therefore expunge it. Once the strange punctuation disappears, we begin to worry about the idiom cry mopsticks. However, there is no certainty that it ever existed, the more so because the sentence in the text does not end with an exclamation mark. Third, mopstick, for which we have no written evidence before 1710, is current in children’s regional names of leapfrog, and this is a sure sign of its antiquity (games tend to preserve local and archaic words for centuries). A mopstick is not a particularly interesting object, yet in 1886 it turned up with the sense “idiot” in a dictionary of dialectal slang. Finally, to return to the question asked above, to look like death on a mopstick means “to look miserable,” and we have to decide whether it sheds light on Swift’s usage or whether Swift’s usage tells us something about the idiom.

An old woman took here sweeping-broom

An old woman took here sweeping-broom And swept the kittens right out of the room.

I think Swift’s bizarre predilection for mopsticks goes back to the early years of the eighteenth century. In 1701 he wrote a parody called A Meditation upon a Broomstick (the manuscript was stolen, and an authorized edition could be brought out only in 1711). It seems that after Swift embarked on his “meditation” and the restitution of the manuscript broomsticks never stopped troubling him. At some time, he may have learned either the word mopstick “idiot” (perhaps in its dialectal form mapstick) and substituted mopstick ~ mapstick for broomstick; a broomstick became to him a symbol of human stupidity. To be sure, mopstick “idiot” surfaced only in 1886, but such words are often recorded late and more or less by chance, in glossaries and in “low literature.”

Swift hated contemporary slang. The last sentence in the quotation given above (Cry, mapsticks, Madam; no offence, I hope) seems to mean “I cry—d–n my foolishness!—Madam…”). The form mapsticks is reminiscent of fiddlesticks, another plural and also an exclamation. The dialectal (rustic) variant with a different vowel (map for mop) could have been meant as an additional insult. If I am right, the comma after cry remains, while the idiom cry mapsticks, along with its reference to cry mercy, joins many other ingenious but unprovable conjectures.

The phrase to look like death on a mopstick has, I believe, nothing to do with Swift’s usage. In some areas, mopstick probably served as a synonym of broomstick, and broomsticks are indelibly connected in our mind with witches and all kinds of horrors. Here a passage from still another letter to Notes and Queries deserves our attention.

“Fifty years ago [that is, in 1830] I recollect an amusement of our boyish days was scooping out a turnip, cutting three holes for eyes and mouth, and putting a lighted candle-end inside from behind. A stake or old mop-stick was then pointed with a knife and stuck into the bottom of the turnip, and a death’s head [hear! hear!] with eyes of fire was complete. Sometimes a stick was tied across it, to make it ghostly and ghastly….”

Those who have observed decorations at Halloween will feel quite at home. The recovering lady looked like death on a mopstick, and we now understand exactly what she meant. In 1880 the letter writer (Mr. Gibbes Rigaud) resided in Oxford. Oxfordshire is next door to Warwickshire, and of course we do not know where our “heroes” spent their childhood.

Image credits: Witch, CC0 via Pixabay. Kittens, public domain via Project Gutenberg.

The post Moping on a broomstick appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA laughing etymologist in a humorless crowdYes? Yeah….Monthly etymology gleanings for November 2014

Related StoriesA laughing etymologist in a humorless crowdYes? Yeah….Monthly etymology gleanings for November 2014

Giving the gift of well-being

In the film A Christmas Story, Ralphie desperately wants “an official Red Ryder, carbine action, 200 shot range model air rifle.” His mom resists because she reckons it will damage his well-being. (“You’ll shoot your eye out!”) In the end, though, Ralphie gets the air rifle and deems it “the greatest Christmas gift I ever received, or would ever receive.”

This Christmas, why not give your friends and family the gift of well-being? Even removing an air rifle and the possibility of eye injury from the mix, that’s easier said than done.

Well-being is tough to pin down. It takes many forms. A college student, a middle-aged parent, and a spritely octogenarian might all lead very different lives and still have well-being. What’s more, you can’t wrap up well-being and tuck it under the tree. All you can do is give gifts that promote it. But what kind of gift promotes well-being?

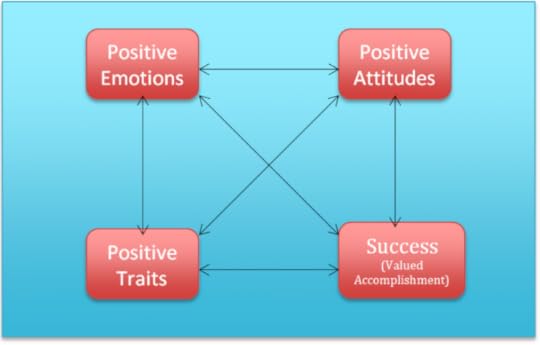

One that establishes or strengthens the positive grooves that make up a good life. You have well-being when you’re stuck in a “positive groove” of:

emotions (e.g., pleasure, contentment), attitudes (e.g., optimism, openness to new experiences), traits (e.g., extraversion, perseverance), and success (e.g., strong relationships, professional accomplishment, fulfilling projects, good health).Your life is going well for you when you’re entangled in a success-breeds-success cycle comprised of states you find (mostly) valuable and pleasant.

Well-being as a positive groove

Well-being as a positive groove Some gifts do this by producing what psychologists call flow. They immerse you in an activity you find rewarding. Flow gifts are easy to spot. They’re the ones, like Ralphie’s air rifle, that occupy you all day.

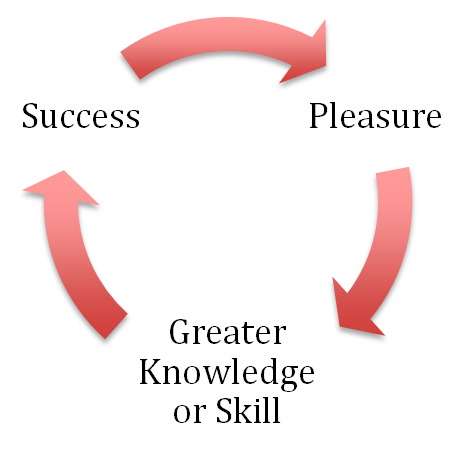

A flow gift promotes well-being by snaring you into a pleasure-mastery-success loop. A flow gift turns you inward, toward a specific activity and away from the rest of the world. It involves an activity that’s fun, that you get better at with practice, and that rewards you with success, even if that “success” is winning a video game car race.

The Flow Gift

The Flow Gift Flow is important to a good life. It feels good, and it fosters excellence. It’s the difference between the piano-playing wiz and the kid (like me) who fizzled out. But there’s more to well-being than flow and excellence.

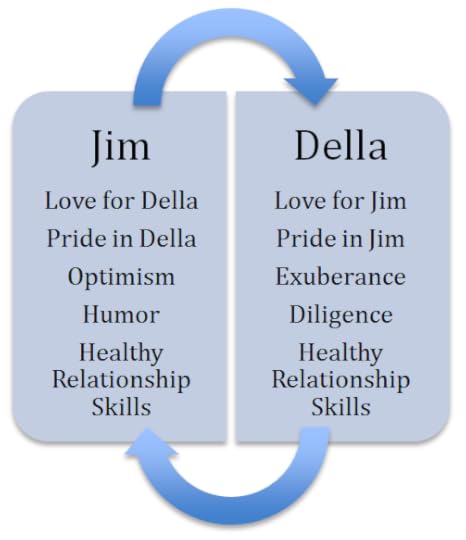

A bonding gift turns you outward, toward other people. A bonding gift shows how someone thinks and feels about you. In O. Henry’s short story The Gift of the Magi, a young couple, Jim and Della, sacrifice their “greatest treasures” to buy each other Christmas gifts. Della sells her luxurious long hair to buy a chain for Jim’s gold watch. And Jim sells his gold watch to buy the beautiful set of combs Della yearned for.

Bonding gifts change people’s relationships. The chain and the combs strengthen and deepen Jim and Della’s love, affection and commitment. This is why “of all who give gifts these two were the wisest.”

The bonds of love and friendship are not just emotional. They’re causal. We’re tangled up with the people we care about in self-sustaining cycles of positive feelings, attitudes, traits and accomplishments. Good relationships are shared, interpersonal positive grooves. This is why they make us better and happier people. Bonding gifts strengthen the positive groove you share with a person you care about.

A good relationship as an interpersonal positive groove

A good relationship as an interpersonal positive groove You’re probably wondering whether you can find something that’s an effective bonding and flow gift. I must admit, I’ve never managed it. A tandem bike? Alas, no. Perhaps you can do better.

So this holiday season, why not give “groovy” gifts – gifts that “keep on giving” by ensnaring your loved ones in cascading cycles of pleasure and value.

Image credit: Stockphotography wrapping paper via Hubspot.

The post Giving the gift of well-being appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesExcusing tortureHeart-stopped: Fiction and the rewards of discomfortWhere is the global economy headed and what’s in store for its citizens?

Related StoriesExcusing tortureHeart-stopped: Fiction and the rewards of discomfortWhere is the global economy headed and what’s in store for its citizens?

Heart-stopped: Fiction and the rewards of discomfort

Recently I was talking to a younger colleague, a recent PhD, about what we and our peers read for pleasure. He noted that the only fiction that most of his friends read is young adult fiction: The Hunger Games, Twilight, that kind of thing. Although the subject matter of these series is often dark, the appeal, hypothesized my colleague, lies elsewhere: in the reassuringly formulaic and predictable narrative arc of the plots. If his friends have a taste for something genuinely edgy, he went on, then they’ll read non-fiction instead.

When did we develop this idea that fiction, to be enjoyable, must be comforting nursery food? I’d argue that it’s not only in our recreational reading but also, increasingly, in the classroom, that we shun what seems too chewy or bitter, or, rather; we tolerate bitterness only if it comes in a familiar form, like an over-cooked Brussels sprout. And yet, in protecting ourselves from anticipated frictions and discomforts, we also deprive ourselves of one of fiction’s richest rewards.

One of the ideas my research explores is the belief, in the eighteenth-century, that fiction commands attention by soliciting wonder. Wonder might sound like a nice, calm, placid emotion, but that was not how eighteenth-century century thinkers conceived it. In an essay published in 1795 but probably written in the 1750s, Adam Smith describes wonder as a sentiment induced by a novel object, a sentiment that may be recognized by the wonderstruck subject’s “staring, and sometimes that rolling of the eyes, that suspension of the breath, and that swelling of the heart” (‘The Principles Which Lead and Direct Philosophical Enquiries’). And that was just the beginning. As Smith describes:

“when the object is unexpected; the passion is then poured in all at once upon the heart which is thrown, if it is a strong passion, into the most violent and convulsive emotions, such as sometimes cause immediate death; sometimes, by the suddenness of the extacy, so entirely disjoint the whole frame of the imagination, that it never after returns to its former tone and composure, but falls either into a frenzy or habitual lunacy.” (‘The Principles Which Lead and Direct Philosophical Enquiries’)

It doesn’t sound very comfortable, does it? Eighteenth-century novels risked provoking such extreme reactions in their tales of people in extremis; cast out; marooned; kidnapped. Such tales were not gory, necessarily, in the manner of The Hunger Games, and the response they invited was not necessarily horror or terror. More radically, in shape and form as well as content, eighteenth-century writers related stories that were strange, unpredictable, unsettling, and, as such, productive of wonder. Why risk discomforting your reader so profoundly? Because, Henry Home, Lord Kames argued in his Elements of Criticism (1762), wonder also fixes the attention: in convulsing the reader, you also impress a representation deeply upon her mind.

Spooky Moon by Ray Bodden. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr

Spooky Moon by Ray Bodden. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr One of the works I find particularly interesting to think about in relation to this idea of wonder is Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein. Frankenstein is a deeply pleasurable book to read, but I wouldn’t describe it as comfortable. Perhaps I felt this more acutely than some when I first read it, as a first year undergraduate. The year before I had witnessed my father experience a fatal heart attack. Ever since then, any description or representation that evoked the body’s motion in defibrillation would viscerally call up the memory of that night. One description that falls under that heading is the climactic moment in Shelley’s novel in which Victor Frankenstein brings his creature to life: “I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.” If the unexpected, in Smith’s account, triggers convulsive motions, then it seems fitting that a newly created being’s experience of its own first breath would indeed be felt as a moment of wonder.

When I was a nineteen year-old reading Frankenstein, there was no discussion about the desirability of providing “trigger warnings” when teaching particular texts; and even if there had been, it seems unlikely that this particular text would have been flagged as potentially traumatic (a fact that speaks to the inherent difficulty of labeling certain texts as more likely to serve as triggers than others, given the variety of people’s experience). I found reading Shelley’s novel to be a deeply, uncomfortably, wonder-provoking experience, in Smith’s terms, but it did not, clearly, result in my “immediate death.” What it did produce, rather, was a deep and lasting impression. Indeed, perhaps that is why, more than twenty years later, I felt compelled to revisit this novel in my research, and why I found myself taking seriously Percy Shelley’s characterization of the experience of reading Frankenstein as one in which we feel our “heart suspend its pulsations with wonder” at its content, even as we “debate with ourselves in wonder,” as to how the work was produced. High affect can be all consuming, but we may also revisit and observe, in more serene moments, the workings of the mechanisms which wring such high affect from us.

In Minneapolis for a conference a few weeks ago, I mentioned to my panel’s chair that I had run around Lake Calhoun. He asked if I had stopped at the Bakken Museum (I had not), which is on the lake’s west shore. He proceeded to explain that it was a museum about Earl Bakken, developer of the pacemaker, whose invention was supposedly inspired by seeing the Boris Karloff 1931 film of Frankenstein, and in particular the scene in which the creature is brought to life with the convulsive electric charge.

As Bakken’s experience suggests, the images that disturb us can also inspire us. Mary Shelley affirms as much in her Introduction to the 1831 edition of the novel, which suggests that the novel had its source in a nightmarish reverie. Shelley assumes that Frankenstein’s power depends upon the reproducible nature of her affect: “What terrified me will terrify others,” she predicts. Haunting images, whether conjured by fantasies, novels, or films, can be generative, although certainly not always in such direct and instrumental ways. Most of us won’t develop a life-saving piece of technology, like Earl Bakken (my father, in fact, had a pacemaker, and, although it didn’t save his life, it did prolong it) or write an iconic novel, like Mary Shelley. But that is not to say that the impressions that fiction can etch into our minds are not generative. If comfort has its place and its pleasures, so too does discomfort: experiencing “bad feelings” enables us to notice, in our re-tracings of them, the unexpected connections that emerge between profoundly different experiences—death; life; reading—all of them heart-stopping in their own ways.

The post Heart-stopped: Fiction and the rewards of discomfort appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Lerner Letters: Part 2 – Lerner and LoeweTouchy-feely politicsExcusing torture

Related StoriesThe Lerner Letters: Part 2 – Lerner and LoeweTouchy-feely politicsExcusing torture

Excusing torture

We have plenty of excuses for torture. Most of them are bad. Evaluating these bad excuses, as ethical philosophers are able to do, should disarm them. We can hope that clear thinking about excuses will prevent future generations–for the sake of their moral health–from falling into the trap.

Ignorance. Senator John McCain knows torture at first hand and condemns it unequivocally. Most of the rest of us don’t have his sort of experience. Does that give us an excuse to condone it or cover it up? Not at all. We can easily read accounts of his torture, along with his heroic response to it. Literature about prison camps is full of tales of torture. With a little imagination, we can feel how torture would affect us. Reading and imagination are crucial to moral education.

Anger and fear. In the grip of fear and anger, people do things they would never do in a calm frame of mind. This is especially true in combat. After heart-rending losses, soldiers are more likely to abuse prisoners or hack up the bodies of enemies they have killed. That’s understandable in the heat of battle. But in the cold-blooded context of the so-called war on terror this excuse has no traction. Of course we are angry at terrorists and we fear what they may do to us, but these feelings are dispositions. They are not the sort of passions that disarm the moral sense. So they do not excuse the torture of detainees after 9/11.

Even in the heat of battle, well-led troops hold back from atrocities. A fellow Vietnam veteran once told me that he had in his power a Viet Cong prisoner, who, he believed, had killed his best friend. He was raging to kill the man, and he could have done it. “What held you back?” I asked. “I knew if I shot him, and word got out, my commander would have me court-martialed.” He was grateful for his commander’s leadership. That saved him from a burden on his conscience.

Saving lives. Defenders of torture say that it has saved American lives. The evidence does not support this, as the Feinstein Committee has shown, but the myth persists. In military intelligence school in 1969 I was taught that torture is rarely effective, because prisoners tell you what they think you want to hear. Or they tell you what they want you to hear. In the case of the Battle of Algiers, one terrorist group gave the French information that led the French to wipe out competing groups.

Enhanced Interrogation by Drewdlecam. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Enhanced Interrogation by Drewdlecam. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr Suppose, however, that the facts were otherwise, that torture does save lives. That is no excuse. Suppose I go into hospital for an appendectomy and the next day my loved ones come to collect me. What they find is a cadaver with vital organs removed. “Don’t fret,” they are told. “We took his life painlessly under anesthetic and saved five other lives with his organs. A good bargain don’t you think?” No. We all know it is wrong to kill one person merely to save others. What would make it right in the case of torture?

The detainees are guilty of terrible crimes. Perhaps. But we do not know this. They have not had a chance for a hearing. And even if they were found guilty, torture is not permitted under ethics or law.

The ad hominem. The worst excuse possible, but often heard: Criticism of torture is politically motivated. Perhaps so, but that is irrelevant. Attacking the critics is no way to defend torture.

Bad leadership: the “pickle-barrel” excuse. Zimbardo has argued that we should excuse the guards at Abu Ghraib because they had been plunged into a situation that we know turns good people bad. His prison experiment at Stanford proved the point. He compares the guards to cucumbers soaked in a pickle barrel. If the cucumbers turn into pickles, don’t blame them. This is the best of the excuses so far; the bipartisan Schlesinger Commission cited a failure of leadership at Abu Ghraib. Still, this is a weak excuse; not all the guards turned sour. They had choices. But good leadership and supervision would have prevented the problem, as it would at the infamous Salt Pit of which we have just learned.

We need to disarm these bad excuses, and the best way to do that is through leadership and education. Torture is a sign of hubris–of the arrogant feeling that we have the power and knowledge to carry out torture properly. We don’t. The ancient Greeks knew that the antidote to hubris is reverence, a quality singularly missing in modern American life.

Headline image credit: ‘Witness Against Torture: Captive Hands’ by Justin Norman. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr

The post Excusing torture appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe other torture reportWhere is the global economy headed and what’s in store for its citizens?The Christmas truce: A sentimental dream

Related StoriesThe other torture reportWhere is the global economy headed and what’s in store for its citizens?The Christmas truce: A sentimental dream

Where is the global economy headed and what’s in store for its citizens?

The Great Recession of 2008–09 badly shook the global market, changing the landscape for finance, trade, and economic growth in some important respects and imposing tremendous costs on average citizens throughout the world. The legacies of the crisis—high unemployment levels, massive excess capacities, low investment and high debt levels, increased income and wealth inequality—reduced the standard of living of millions of people. There is an emerging consensus that global economic governance, as well as national policies, needs to be reformed to better reflect the economic interests and welfare of citizens.

Global recovery is sluggish and the outlook uncertain. The economies of the Eurozone, which may have fallen into a “persistent stagnation trap,” and Japan remain highly vulnerable to deflation and another bout of recession; in the advanced economies that are growing, recovery remains uneven and fragile. Growth in emerging and developing economies is slowing, as a result of tighter global financial conditions, slow growth of world trade, and lower commodity prices. Because consumption and business investment have been tepid in many countries, the gradual global recovery has been too weak to create enough jobs. Official worldwide unemployment climbed to more than 200 million people in 2013, including nearly 75 million people aged 15–24.

Professor Roubini, one of the few economists who predicted the 2008 crisis, has argued that the global economy is like a four-engine jetliner that is operating with only one functioning engine, the “Anglosphere.” The plane can remain in the air, but it needs all four engines (the Anglosphere, the Eurozone, Japan, and emerging economies) to take off and stay clear of storms. He predicts serious challenges, including from rising debt and income inequality.

Relatively slow growth in the advanced economies and potential new barriers to trade over the medium term have significant adverse implications for growth and poverty reduction in many developing countries. Emerging economies, including China and India, that thrived in recent decades in part by engaging extensively in the international economy are at risk of finding lower demand for their output and greater volatility in international financial flows and investments. A combination of weaker domestic currencies against the US dollar and falling commodity prices could adversely affect the private sector in emerging economies that have large dollar-denominated liabilities.

Money, money, money, by Wouter de Bruijn. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Money, money, money, by Wouter de Bruijn. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr. Rising inequality is holding back consumption growth. The ratio of wealth to income, as well as the income shares of the top 1% of income earners, has risen sharply in Europe and the United States since 1980, as Professor Piketty has shown.

The ratio of the share of income earned by the top 10% to the share of income earned by the bottom 90% rose in a majority of OECD countries since 2008, a key factor behind the sluggish growth of their household consumption. During the first three years of the current recovery (2009–12), incomes of the bottom 90% of income earners actually fell in the United States: the top 10%, who tend to have much lower propensity to consume than average earners, captured all the income gains. In developing countries for which data were available for 2006–12, the increase in the income or consumption of the bottom 40% exceeded the country average in 58 of 86 countries, but in 18 countries, including some of the poorest economies, the income or consumption of the bottom 40% actually declined, according to a report by the World Bank and IMF.

Some signs of possible relief may lie ahead. In September 2014, leaders at the G20 summit in Brisbane agreed on measures to increase investment infrastructure, spur international trade and improve competition, boost employment, and adopt country-specific macroeconomic policies to encourage inclusive economic growth. If fully implemented, the measures could add 2.1% to global GDP (more than $2 trillion) by 2018 and create millions of jobs, according to IMF and OECD analysis. (These estimates need to be treated with caution, as the measures that underpin them and their potential impact are uncertain, and the nature and strength of the policy commitments vary considerably across individual country growth strategies.)

Another potential sign of hope is the sharp decline in the prices of energy, a reflection of both weaker global demand and increased supply (particularly of shale oil and gas from the United States). The more than $40 a barrel decline in Brent crude prices is likely to raise consumers’ purchasing power in oil-importing countries in the OECD area and elsewhere and spur growth, albeit at considerable cost (and destabilizing effects) for the more populous and poorer oil exporters. It could also be a harbinger of energy price spikes down the road, as the massive investments needed to ensure adequate supplies of energy may not be forthcoming as a result of their unprofitability at low prices.

Pumping water in Malawi, by International Livestock Research Institute. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Pumping water in Malawi, by International Livestock Research Institute. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr. Major global challenges have wide-ranging long-term implications for the average citizen. By 2030, the world’s population is projected to reach 8.3 billion people, two-thirds of whom will live in urban areas. Massive changes in the patterns of energy and resource (particularly water) use will be needed to accommodate this 1.3 billion person increase—and the elevation of 2–3 billion people to the middle class.

A citizen-centered policy agenda would need to reform national economies to spur growth and job creation, placing greater reliance on national and regional markets and the sustainable use of resources; emphasize social policies and the economic health of the lower and middle classes; invest in human capital and increase access to clean water, sanitation and quality social services, including a stronger foundation during the early years of life and support for aging with dignity and equity; improve labor market flexibility to employ young people productively; and enhance human rights and the freedom of people to move, internally and internationally. These policies would need to be complemented by policies that use collective action to mitigate risks to the global economy.

To prevent another global crisis, there is an urgent need to strengthen global economic governance, including through global trade agreements that favor the bottom half of income distribution; reform of the international monetary system, including the functioning and governance structure of the international financial institutions; encouragement of inclusive finance; and institution of policies to discourage asset bubbles. To achieve sustainable growth, all countries need to remove fossil fuels and other harmful subsidies and begin pricing carbon and other environmental externalities.

Worldwide surveys show that citizens everywhere are becoming more aware and active in seeking changes in the global norms and rules that could make the global system and the global economy fairer and less environmentally harmful. This sense is highest among the young and better-educated, suggesting that over time it will increase, potentially leading to equitable results for all citizens through better national and international policies.

Headline image: World Map – Abstract Acrylic, by Free Grunge Textures. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Where is the global economy headed and what’s in store for its citizens? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDoing development differentlyA different kind of swindleThe other torture report

Related StoriesDoing development differentlyA different kind of swindleThe other torture report

The Christmas truce: A sentimental dream

By December 1914 the Great War had been raging for nearly five months. If anyone had really believed that it would be ‘all over by Christmas’ then it was clear that they had been cruelly mistaken. Soldiers in the trenches had gained a grudging respect for their opposite numbers. After all, they had managed to fight each other to a standstill.

On Christmas Eve there was a severe frost. From the perspective of the freezing-cold trenches the idea of the season of peace and goodwill seemed surrealistic. Yet parcels and Christmas gifts began to arrive in the trenches and there was a strange atmosphere in the air. Private William Quinton was watching:

We could see what looked like very small coloured lights. What was this? Was it some prearranged signal and the forerunner of an attack? We were very suspicious, when something even stranger happened. The Germans were actually singing! Not very loud, but there was no mistaking it. Suddenly, across the snow-clad No Man’s Land, a strong clear voice rang out, singing the opening lines of “Annie Laurie“. It was sung in perfect English and we were spellbound. To us it seemed that the war had suddenly stopped! Stopped to listen to this song from one of the enemy.

“We tied an empty sandbag up with its string and kicked it about on top – just to keep warm of course. We did not intermingle.”

On Christmas Day itself, in some sectors of the line, there was no doubting the underlying friendly intent. Yet the men that took the initiative in initiating a truce were brave – or foolish – as was witnessed by Sergeant Frederick Brown:

Sergeant Collins stood waist high above the trench waving a box of Woodbines above his head. German soldiers beckoned him over, and Collins got out and walked halfway towards them, in turn beckoning someone to come and take the gift. However, they called out, “Prisoner!” A shot rang out, and he staggered back, shot through the chest. I can still hear his cries, “Oh my God, they have shot me!”

This was not a unique incident. Yet, despite the obvious risks, men were still tempted. Individuals would get off the trench, then dive back in, gradually becoming bolder as Private George Ashurst recalled:

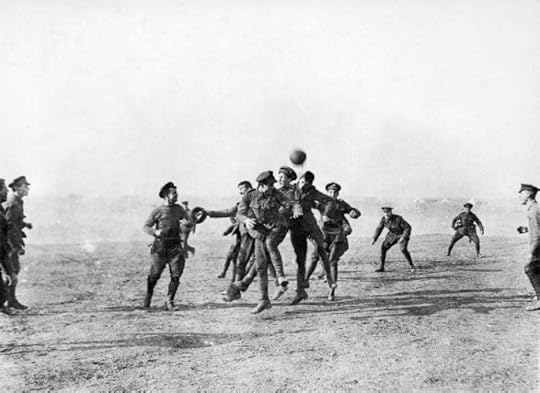

It was grand, you could stretch your legs and run about on the hard surface. We tied an empty sandbag up with its string and kicked it about on top – just to keep warm of course. We did not intermingle. Part way through we were all playing football. It was so pleasant to get out of that trench from between them two walls of clay and walk and run about – it was heaven.

The idea that football matches were played between the British and Germans in No Man’s Land has taken a grip, but the evidence is intangible.

“Officers and men of 26th Divisional Ammunition Train playing football in Salonika, Greece on Christmas day 1915.” (1915) by Varges Ariel, Ministry of Information. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Officers and men of 26th Divisional Ammunition Train playing football in Salonika, Greece on Christmas day 1915.” (1915) by Varges Ariel, Ministry of Information. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. The truce was not planned or controlled – it just happened. Even senior officers recognised that there was little that could be done in this strange state of affairs. Brigadier General Lord Edward Gleichen accepted the truce as a fait accompli, but was keen to ensure that the Germans did not get too close to the ramshackle British trenches:

They came out of their trenches and walked across unarmed, with boxes of cigars and seasonable remarks. What were our men to do? Shoot? You could not shoot unarmed men. Let them come? You could not let them come into your trenches; so the only thing feasible was done – and our men met them half-way and began talking to them. Meanwhile our officers got excellent close views of the German trenches.

Another practical reason for embracing the truce was the opportunity it presented for burying the dead that littered No Man’s Land. Private Henry Williamson was assigned to a burial party:

The Germans started burying their dead which had frozen hard. Little crosses of ration box wood nailed together and marked in indelible pencil. They were putting in German, ‘For Fatherland and Freedom!’ I said to a German, “Excuse me, but how can you be fighting for freedom? You started the war, and we are fighting for freedom!” He said, “Excuse me English comrade, but we are fighting for freedom for our country!”

It should be noted that the truce was by no means universal, particularly where the British were facing Prussian units.

For the vast majority of the participants, the truce was a matter of convenience and maudlin sentiment. It did not mark some deep flowering of the human spirit, or signify political anti-war emotions taking root amongst the ranks. The truce simply enabled them to celebrate Christmas in a freer, more jovial, and, above all, safer environment, while satisfying their rampant curiosity about their enemies.

The truce could not last: it was a break from reality, not the dawn of a peaceful world. The gradual end mirrored the start, for any misunderstandings could cost lives amongst the unwary. For Captain Charles Stockwell it was handled with a consummate courtesy:

At 8.30am I fired three shots in the air and put up a flag with ‘Merry Christmas!’ on it, and I climbed on the parapet. He put up a sheet with, ‘Thank you’ on it, and the German captain appeared on the parapet. We both bowed and saluted and got down into our respective trenches – he fired two shots in the air and the war was on again!

In other sectors, the artillery behind the lines opened up and the bursting shells soon shattered the truce.

War regained its grip on the whole of the British sector. When it came to it, the troops went back to war willingly enough. Many would indeed have rejoiced at the end of the war, but they were still willing to accept orders, still willing to kill Germans. Nothing had changed.

The post The Christmas truce: A sentimental dream appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMagical Scotland: the OrkneysRemembrance Day1914: The Battle for Basra

Related StoriesMagical Scotland: the OrkneysRemembrance Day1914: The Battle for Basra

December 16, 2014

The other torture report

At long last – despite the attempts at sabotage by and over the protests of the CIA, and notwithstanding the dilatory efforts of the State Department – the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence has finally issued the executive summary of its 6,300-page report on the CIA’s detention and interrogation program. We should celebrate its publication as a genuine victory for opponents of torture. We should thank Senator Dianne Feinstein (whom some of us have been known to call “the senator from the National Security Agency”) for her courage in making it happen.

Like many people, I’ve got my criticisms of the Senate report. Suffice it to say that we’ve still got work to do if we want to end US torture.

We now know something about the Senate report, but many folks may not have heard about the other torture report, the one that came out a couple of weeks ago, and was barely mentioned in the US media. In some ways, this one is even more damning. For one thing, it comes from the international body responsible for overseeing compliance with the UN Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment – the UN Committee Against Torture. For another, unlike the Senate report, the UN report does not treat US torture as something practiced by a single agency, or that ended with the Bush administration. The UN Committee Against Torture reports on US practices that continue to this day.

Here are some key points:

Guards from Camp 5 at Joint Task Force Guantanamo escort a detainee from his cell to a recreational facility within the camp. Photo by US Navy Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Kilho Park. Public domain via Joint Task Force Guantanamo. The United States still refuses to pass a law making torture a federal crime. It also refuses to withdraw some of the “reservations” it put in place when it signed the Convention. These include the insistence that only treatment resulting in “prolonged mental harm,” counts as the kind of severe mental suffering outlawed in the Convention. Many high civilian officials and some military personnel have not been prosecuted for acts of torture they are alleged to have committed. It would be nice, too, says the Committee, if the United States were to join the International Criminal Court, where other torturers have already been successfully tried. If we can’t prosecute them at home, maybe the international community can do it. The remaining 142 detainees at Guantánamo must be released or tried in civilian courts, and the prison there must be shut down. Evidence of US torture must be declassified, especially the torture of anyone still being held at Guantánamo. While the US Army Field Manual on Human Intelligence Collector Operations prohibits many forms of torture, a classified “annex” still permits sleep deprivation and sensory deprivation. These are both forms of cruel treatment which must end. People held in US jails and prisons must be protected from long-term solitary confinement and rape. “Supermax” facilities and “Secure Housing Units,” where inmates spend years and even decades in complete isolation must be shut down. As many as 80,000 prisoners are believed to be in solitary confinement in US prisons today – a form of treatment we now understand can cause lasting psychosis in as short a time as two weeks. The United States should end the death penalty, or at the very least declare a moratorium until it can find a quick and painless method of execution. The United States must address out-of-control police brutality, especially “against persons belonging to certain racial and ethnic groups, immigrants and LGBTI individuals.” This finding is especially poignant in a period when we have just witnessed the failure to indict two white policemen who killed unarmed Black men: Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City. Like many who have been demonstrating during the last few weeks against racially selective police violence, the Committee was also concerned about “racial profiling by police and immigration offices and growing militarization of policing activities.”

Guards from Camp 5 at Joint Task Force Guantanamo escort a detainee from his cell to a recreational facility within the camp. Photo by US Navy Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Kilho Park. Public domain via Joint Task Force Guantanamo. The United States still refuses to pass a law making torture a federal crime. It also refuses to withdraw some of the “reservations” it put in place when it signed the Convention. These include the insistence that only treatment resulting in “prolonged mental harm,” counts as the kind of severe mental suffering outlawed in the Convention. Many high civilian officials and some military personnel have not been prosecuted for acts of torture they are alleged to have committed. It would be nice, too, says the Committee, if the United States were to join the International Criminal Court, where other torturers have already been successfully tried. If we can’t prosecute them at home, maybe the international community can do it. The remaining 142 detainees at Guantánamo must be released or tried in civilian courts, and the prison there must be shut down. Evidence of US torture must be declassified, especially the torture of anyone still being held at Guantánamo. While the US Army Field Manual on Human Intelligence Collector Operations prohibits many forms of torture, a classified “annex” still permits sleep deprivation and sensory deprivation. These are both forms of cruel treatment which must end. People held in US jails and prisons must be protected from long-term solitary confinement and rape. “Supermax” facilities and “Secure Housing Units,” where inmates spend years and even decades in complete isolation must be shut down. As many as 80,000 prisoners are believed to be in solitary confinement in US prisons today – a form of treatment we now understand can cause lasting psychosis in as short a time as two weeks. The United States should end the death penalty, or at the very least declare a moratorium until it can find a quick and painless method of execution. The United States must address out-of-control police brutality, especially “against persons belonging to certain racial and ethnic groups, immigrants and LGBTI individuals.” This finding is especially poignant in a period when we have just witnessed the failure to indict two white policemen who killed unarmed Black men: Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City. Like many who have been demonstrating during the last few weeks against racially selective police violence, the Committee was also concerned about “racial profiling by police and immigration offices and growing militarization of policing activities.” Why should an international body focused specifically on torture care about an apparently broader issue like police behavior? In fact, torture and race- or identity-based police brutality are intimately linked by the reality that lies at the foundation of institutionalized state torture.

Every nation that uses torture must first identify one or more groups of people who are torture’s “legitimate” targets. They are legitimate targets because in the minds of the torturers and of the society that gives torture a home, these people are not entirely human. (In fact, the Chilean secret police called the people they tortured “humanoids.”) Instead, groups singled out for torture are a uniquely degraded and dangerous threat to the body politic, and therefore anything “we” must do to protect ourselves becomes licit. In the United States, with lots of encouragement from the news and entertainment media, many white people believe that African American men represent this kind of unique threat. The logic that allows police to kill unarmed Black men with impunity is not all that different from the logic that produces pogroms or underlies drone assassination programs in far-off places, or that makes it impossible to prosecute our own torturers.

At 15 pages, the whole UN report is certainly a quicker read than the Senate committee’s 500-page “summary.” And it’s a good reminder that, whatever President Obama might wish, this is not the time to close the book on torture. It’s time to re-open the discussion, to hold the torturers accountable, and to bring a real end to US torture.

The post The other torture report appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 quotes to inspire a love of winterDoing development differentlyMagical Scotland: the Orkneys

Related Stories10 quotes to inspire a love of winterDoing development differentlyMagical Scotland: the Orkneys

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers