Oxford University Press's Blog, page 719

December 25, 2014

Seasonal spirit in OUP offices across the globe

This holiday season, we asked staff in the Oxford University Press offices around the globe to send in photos of cheer and good spirit the the end of 2014.

Melbourne, Australia

Melbourne, Australia Courtesy of Nicola Wiedeling

Melbourne, Australia

Melbourne, Australia Courtesy of Nicola Wiedeling

Melbourne, Australia

Melbourne, Australia Courtesy of Nicola Wiedeling

New Delhi

New Delhi Courtesy of Saishah Joseph

New Delhi

New Delhi Courtesy of Saishah Joseph

New Delhi

New Delhi Courtesy of Saishah Joseph

New Delhi

New Delhi Courtesy of Saishah Joseph

Cape Town, South Africa

Cape Town, South Africa Courtesy of Zelda Rowan

Cape Town, South Africa

Cape Town, South Africa Courtesy of Zelda Rowan

Oxford, UK

Oxford, UK Courtesy of Jack Campbell-Smith

Oxford, UK

Oxford, UK Courtesy of Anna Silva

Oxford, UK

Oxford, UK Courtesy of Anna Silva

Oxford, UK

Oxford, UK Courtesy of Jack Campbell-Smith

Oxford, UK

Oxford, UK Courtesy of Jack Campbell-Smith

Oxford, UK

Oxford, UK Courtesy of Jack Campbell-Smith

Oxford, UK

Oxford, UK Courtesy of Jack Campbell-Smith

New York City

New York City Courtesy of Sara Levine

New York City

New York City Courtesy of Sara Levine

New York City

New York City Courtesy of Sara Levine

New York City

New York City Courtesy of Sara Levine

New York City

New York City Courtesy of Sara Levine

New York City

New York City Courtesy of Sara Levine

New York City

New York City Courtesy of Sara Levine

Cary, North Carolina

Cary, North Carolina Courtesy of Kimberly Taft

Cary, North Carolina

Cary, North Carolina Courtesy of Kimberly Taft

Cary, North Carolina

Cary, North Carolina Courtesy of Kimberly Taft

And Season’s Greetings from all of us at Oxford University Press…

The post Seasonal spirit in OUP offices across the globe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSeven facts about American Christmas MusicA smorgasbord of Christmas foodsA perfume for loneliness

Related StoriesSeven facts about American Christmas MusicA smorgasbord of Christmas foodsA perfume for loneliness

Seven facts about American Christmas Music

With that familiar chill in the air signaling winter’s imminent arrival, it’s time again to indulge our craving for Christmas music by Frank Sinatra, Mariah Carey, and more. But first, let’s take a step back and explore the history of Christmas music with the following facts.

From medieval Christmas celebrations onwards, the holiday has included Christian, pagan, and secular elements. For example, American Christmas songs range from religious hymns and carols to secular songs about Santa Claus and general goodwill. During the 17th and 18th centuries, American colonists celebrated Christmas with mumming practices, including costumes, pranks, dancing, and musical instruments. Boston tanner and composer William Billings wrote sacred Christmas music in the 18th century. American Christmas music developed from various immigrant traditions, gaining popularity in the United States during the 19th century. Charles Dickens contributed to the popularity of Christmas traditions with his successful novels The Pickwick Papers (1836-7) and A Christmas Carol (1843). Celebrations during this period included door-to-door Christmas caroling, Christmas cards, and “living nativity” scenes. Several classic Christmas carols were produced in the 19th century, including “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear” (1849), “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” (1863), and “Away in a Manager” (1885). The popularity of Christmas music exploded with radio, television, and film in the 20th century. Hollywood has played an important role in the popularity of Christmas music with films like Holiday Inn (1942), Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964), It’s A Wonderful Life (1946), and A Christmas Story (1983). (We couldn’t resist posting this classic scene below.)Check out our list of classic Christmas tunes below:

Headline image credit: Lighted Santa Reindeer, 2012. Photo by Anthony92931. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Seven facts about American Christmas Music appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA festive Festivus music playlist10 fun facts about sleigh bellsAnnie and girl culture

Related StoriesA festive Festivus music playlist10 fun facts about sleigh bellsAnnie and girl culture

A smorgasbord of Christmas foods

In many parts of the world, Christmas does not lack in spirit or rich flavors. Though sweets are a major highlight to this festive holiday, there are quite a few notable savory foods to consider. As you are sitting down to your third helping of turkey, take a look through just some of the Christmas foods people will be eating this year:

What sorts of Christmas foods do you have every year? Let us know in the comments below.

Headline image credit: Christmas decoration. Image by Hades2k. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A smorgasbord of Christmas foods appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA look at Thanksgiving favoritesA holiday food tourA map of the world’s cuisine

Related StoriesA look at Thanksgiving favoritesA holiday food tourA map of the world’s cuisine

December 24, 2014

Season’s greetings, or “That’s the cheese”

As every student of etymology knows, today, after at least five centuries of European historical linguistics, it is hard and often impossible to discover what has been said about the origin of any word of such well-researched languages as Classical Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, German, or English. Hence my fight for updated analytic etymological dictionaries that survey the entire field and leave little (and sometimes nothing) to glean. They describe the state of the art and invite the reader to pick up where older scholars and amateurs have left off. Fortunately, the goal of retracing the steps of one’s predecessors results in more than amassing footnotes and providing an impressive apparatus. In the process of reading old — and sometimes very old — articles and books we follow the paths of human thought with its victories and defeats. Few things are more interesting than finding out how people, in their wisdom, arrive at and, in their foolishness, reject the truth. If we agree that a drop of water reflects the whole world, we may also agree that a look at the history of the smallest problem may be important and instructive.

The origin of the idiom that’s the cheese is certainly a very small problem. At least as early as 1865 someone who revealed to the readership only his first initials — and whom, on the analogy of Mr. W. H., the famous “begetter” of Shakespeare’s sonnets, we will call Mr. W. S. (for this is how he signed the lettter) — wrote: “A friend of mine who has just returned from India has suggested that it is derived from a word very common in Bengalee [sic] as spoken in Calcutta.” Some wits, he added, say: “That’s the Stilton” or “That’s the Cheshire.” Another letter writer, also in 1865, confirmed W. S.’s opinion and stated that he had been familiar with this usage thirty years earlier. In 1853 still another correspondent remarked in Notes and Queries: “This phrase is only some ten or twelve years old.” His memory takes us to the beginning of the eighteen-forties.

A better etymology of cheese “the real thing” has not been found, though the OED was able to provide 1818 as the date of the first citation. Considering how many words reached Standard English from India, the Hindustani etymology is not improbable. All the serious later dictionaries, unless they say “origin unknown,” accepted it, which does not mean that we can celebrate the result, have a group photo featuring our happy faces, and say cheese, because cheese occurs in other, sometimes more, sometimes less, obscure idioms and metaphors. For example,

cheese “nonsense” get one’s cheese “to attain one’ goal” cheese it “stop it; let’s get out of here” (an exclamation of alarm and a warning at the approach of police or other authorities, once—or still?— common among British and American schoolboys) make the cheese more binding “snarl the matter” hard cheese “too bad” big cheese (the latter probably an extension of that’s the cheese) cheesy “vulgar, shabby, shoddy”It is hard to understand why cheese has been victimized to such a degree. Even the moon is said to be made of green (that is, fresh) cheese.

Henry Yule, the author of

Hobson Jobson

, a book on the English language in India, cited the idiom that’s the cheese, and the OED treated this source with confidence.

Henry Yule, the author of

Hobson Jobson

, a book on the English language in India, cited the idiom that’s the cheese, and the OED treated this source with confidence. Who knows? Perhaps that’s the cheese had its origin in British regional slang, coincided with the Hindustani noun, and was appropriated by English speakers in India. In bilingual jargons, puns of this type occur all the time. However unproductive such fantasies may be, they explain why some people tried to find other solutions. The following suggestion, borrowed from Vizetelly and De Bakker’s A Desk-Book of Idioms and Idiomatic Phrases in English Speech and Literature (one never knows where etymological hypotheses may turn up, which makes them almost impossible to find) was quoted in 1923 in a note titled “The Cheese, the Whole Cheese, and Nothing but the Cheese”:

“A low courtesy made by whirling the gown or petticoats around until they are inflated like a balloon or resemble a large cheese, then sinking to the ground. To this deep ceremonial courtesy has been traced the use of cheese meaning the correct thing; as ‘quite the cheese’, but it may also be traced to the Hindustani chiz, which means thing.”

Regrettably (especially so because Vizetelly was an experienced lexicographer and editor), the authors did not say who traced cheese in our idiom to a low courtesy and where. Also, it was pointed out at the beginning of the 1865 discussion that the correct pronunciation of the Hindustani word is cheeze, not chiz.

A hopeless derivation traced that’s the cheese to French.

“Some desperate witty fellows by way of giving a comic turn to the phrase c’est une autre chose [‘that’s another matter’] used to translate it ‘that is another cheese’, and after a while these words became household words.”

The cheese ~ chose connection enjoyed some popularity on both sides of the Atlantic, though the nasty wags responsible for the introduction of the phrase in question have not been found. This derivation is reminiscent of the desperate attempt to explain the idiom to sleep like a top by referring top to French taupe “mole” (animal).

Still another bold guesser was “disposed to think that it [the phrase] is a corruption of good Saxon, thus:—The word choice was formerly written chose, from ceosan [I have corrected two typos in the form] = to choose…. When one says ‘that the cheese’, I understand it to mean ‘that’s the proper thing—that’s what I would have chosen…’.” It is true that the infinitives of the verbs belonging to the choose/lose class have doublets with ee in the root, but an etymology connecting cheese “choose” and cheese “milk product” will strike every sober researcher as bizarre, to say the least. The moral is: never be “disposed” to think that you know the origin of a word or an idiom unless you have investigated the problem in depth. Look before you leap into the hot water of etymology.

Even if the facetious idiom that’s the cheese goes back to the usage of Englishmen who resided in India, it remains unclear when under what circumstances it gained currency. Linguists who study borrowings sometimes forget to ask the question about the reception of this or that loanword. I will finish this post with still another quotation:

“The late David Rees, an eminent comedian, well known in London and Dublin, was celebrated for original bon mots on the stage. The above phrase [that’s the cheese] was first introduced into Dublin by him, in a piece called The Red Eye, the scene of which was laid in the Morea. The phrase became very popular, and was used when a person wanted to impress on another that something very important had been said or done in reference to something in hand. I have a clear recollection of having asked Mr. Rees what was the origin of the term, and he replied it arose in consequence of a half-witted boy having eaten a piece of soap and then told his grandmother what a nice piece of cheese he had eaten. ‘It was soap’, cried the old lady. ‘Oh, no’, cried the boy, ‘that was the cheese’. Such is the story as it was told to me” (S. Redmond. Notes and Queries, Series 3, vol. VII, p. 465 for June 10, 1865).

The story of the boy (sometimes even his name—naturally, Paddy—is given) is of course sheer nonsense, regardless of how many people repeated it in both Ireland and England, but the connection or part of it with David Rees may be real. As to the Hindustani origin of the idiom, nothing militates against it. Cheese, along with the word for it, came to Anglo-Saxon England from the Romans. Why then couldn’t the idiom that’s the cheese come to Great Britain from India?

Image credits: (1) Dark Cherry Cheesecake. Photo by jpellgen. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via jpellgen Flickr. (2) Sir Henry Yule, from the Preface to The Book of Ser Marco Polo. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Season’s greetings, or “That’s the cheese” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMoping on a broomstickA laughing etymologist in a humorless crowdYes? Yeah….

Related StoriesMoping on a broomstickA laughing etymologist in a humorless crowdYes? Yeah….

What did the Treaty of Ghent do? A look at the end of the War of 1812

Two hundred years ago American and British delegates signed a treaty in the Flemish town of Ghent to end a two-and-a-half-year conflict between the former colonies and mother country. Overshadowed by the American Revolution and Napoleonic Wars in the two nations’ historical memories, the War of 1812 has been somewhat rehabilitated during its bicentennial. Yet arguing for the importance of a status quo antebellum treaty that concluded a war in which neither belligerent achieved its war aims, no territory was exchanged, and no victor formally declared can be a tough sell. Compared to the final defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, fought a just a few months later and forty odd miles down the road from Ghent, the end of the War of 1812 admittedly lacked cinema-worthy drama.

But the Treaty of Ghent mattered enormously (and not just to historians interested in the War of 1812). The war it ended saw relatively light casualties, measured in the thousands compared to the millions who died in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars that raged across the rest of the globe. Nevertheless, for the indigenous and colonizing peoples that inhabited the borderlands surrounding the United States, the conflict had proved devastating. Because the American and British economies were intertwined, the war had also wreaked havoc on American agriculture and British manufacturing, and wrecked each other’s merchant navies. Moreover, public support for the war in the British Empire and the United States had been lukewarm with plenty of outspoken opposition who had worked tirelessly to prevent and then quickly end the war.

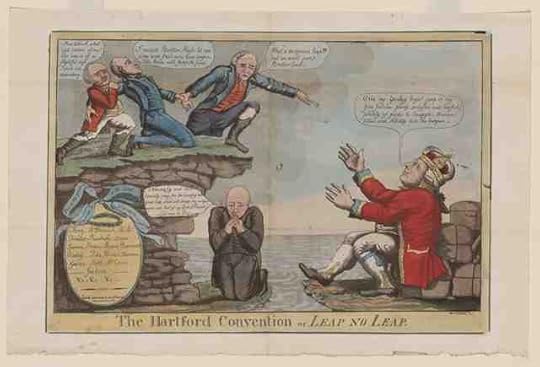

William Charles, “The Hartford Convention or Leap No Leap,” (Philadelphia, c. 1814). Library of Congress. The print depicts New England Federalist contemplating secession, which Charles equates to a return to the fold of the British Empire—represented as the open-armed King George III. In the center is Timothy Pickering, the former Secretary of State and outspoken opponent of the war in Congress, who is praying fervently (an attack on those New England clergy who publicly opposed the war) for secession and for the personal rewards of wealth and aristocratic title it would bring him.

William Charles, “The Hartford Convention or Leap No Leap,” (Philadelphia, c. 1814). Library of Congress. The print depicts New England Federalist contemplating secession, which Charles equates to a return to the fold of the British Empire—represented as the open-armed King George III. In the center is Timothy Pickering, the former Secretary of State and outspoken opponent of the war in Congress, who is praying fervently (an attack on those New England clergy who publicly opposed the war) for secession and for the personal rewards of wealth and aristocratic title it would bring him. Not surprisingly, peace resulted in widespread celebration across the Atlantic. The Leeds Mercury, many of whose readers were connected to the manufacturing industries that had relied on American markets, even compared the news with that of the Biblical account of the angelic chorus’s announcement of the birth of Jesus: “This Country, thanks to the good Providence of God, is now at Peace with Europe, with America, and with the World. . . . There is at length ‘Peace on Earth,’ and we trust the revival of ‘Good-will among men’ will quickly follow the close of national hostilities.” When the treaty reached Washington for ratification, President James Madison and Congress fell over themselves in a rush to sign it.

Far more interesting than what the relatively brief Treaty of Ghent includes is what was left out. When the British delegation arrived at Ghent in August 2014, they had every possible advantage. Britain had won the naval war, the United States was on brink of bankruptcy, and the end of Britain’s war with France meant that hardened veterans were being deployed for an imminent invasion of the United States. Later that month British troops would humiliatingly burn Washington. Even Ghent itself was a home field advantage, as it was occupied by British troops and within a couple of days of communication with ministers in London.

In consequence, Britain’s initial demands were severe. If the United States wanted peace, it had to cede 250,000 square miles of its northwestern lands (amounting to more than 15% of US territory, including all or parts of the modern states of Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Missouri, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota). These lands would be used to create an independent American Indian state—promises of which the British had used to recruit wary Indian allies. Britain also demanded a new border for Canada, which included the southern shores of the Great Lakes and a chunk of British-occupied Maine—changes that would have given Canada considerable natural defenses. The Americans, claimed the British, were “aggrandizers”, and these measures would ensure that such ambitions would be forever thwarted.

The significance of the terms is difficult to underestimate. Western expansion would have ground to a halt in the face of a powerful British-led alliance with the Spanish Empire and new American Indian state. The humiliation would likely have resulted in the collapse of the United States. The long-marginalized New England Federalists had been outspoken in their opposition to the war and President James Madison’s Southern-dominated Republican Party, with some of their leaders openly threatening secession. The Island of Nantucket had already signed a separate peace with Britain, and many inhabitants of British-occupied Maine had signed oaths of allegiance to Britain. The Governor of Massachusetts had even sent an agent to Canada to discuss terms of British support for his state’s secession, which included a request for British troops. The counterfactuals of a New England secession are too great to explore here, but the implications are epic—not least because, unlike in 1861, the US government in 1814 was in no position to stop one. In the end, a combination of the American delegates’ obstinacy and a rapidly fading British desire to keep the nation on an expensive war footing solely to fight the Americans led the British to abandon their harsh terms.

In consequence, the Treaty of Ghent cemented the United States rather than destroyed it. Historians have long debated who truly won the war. However, what mattered most was that neither side managed a decisive victory. The Americans lacked the organization and national unity to win; the British lacked the will to wage an expensive, offensive war in North America. American inadequacy ensured that all of Canada would prosper as part of the British Empire, even though Upper Canada (now Ontario) had arguably closer links to the United States and was populated largely by economic migrants from the United States. British desire to avoid further confrontation enabled the Americans to focus its attentions on eliminating the other, and considerably weaker, obstacles to continental supremacy: the American Indians and the remnants of the Spanish Empire, who proved to be the real losers of the War of 1812 and the Treaty of Ghent.

Featured image: The Signing of the Treaty of Ghent, Christmas Eve, 1814, Amédée Forestier (1814). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What did the Treaty of Ghent do? A look at the end of the War of 1812 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSherman’s March to the SeaBlack Israelites and the meaning of ChanukahBehind Korematsu v. United States

Related StoriesSherman’s March to the SeaBlack Israelites and the meaning of ChanukahBehind Korematsu v. United States

Understanding the local economic impacts of projects and policies

In central Africa, the World Food Program is shifting from aid in kind to cash and vouchers in the refugee camps that it runs. The hope is to create benefits for the surrounding host-country economies as well as for the refugees, themselves.

In West Gonja, Ghana, the UN Food and Agricultural Organization is investing in cassava processing and marketing, in the hope of stimulating incomes, employment, and welfare in one of the country’s poorest regions.

In a small-scale fishery in the Philippines, the government hopes to introduce new regulations to ensure the fishery’s long-term sustainability. The long-term gains are clear, but in the short run, nobody knows what limiting access will mean for an economy in which most fisher households are poor, and income from fishing is vital to these as well as other poor households with whom they interact.

These are classic situations in which local economy-wide impact evaluation (LEWIE) methods can be incredibly useful. These methods model the way local economies function, and can be used to simulate how these economies might behave under shifting conditions. In cases such as those mentioned above, impacts depend critically on how local economies adjust. For example, if local supply responses around refugee camps or in the cassava-producing communities of West Gonja are low, policies that simulate demand could raise prices and harm people they intend to benefit, with collateral damage on other linked sectors and household groups.

For those designing or evaluating a policy or program, LEWIE methods can highlight impacts not only on those directly affected by the intervention, but also the spillover impacts around them. Policy makers and donors want to know what sorts of complementary interventions might be needed in order to make sure that their programs are successful. Often, answers are needed before programs and policies are put into place. LEWIE methods were designed to provide such answers. The stakes are high, and as always, time and resources are limited.

We find that LEWIE often has impacts far beyond what we anticipate when we begin an evaluation. Often, it reveals benefits missed by other approaches. Documenting likely impacts beyond those affected directly by an intervention ex-ante can tip the cost-benefit scale in favor of funding the intervention. More and more, governments and donors want to know that a development project not only benefits targeted households and sectors but also creates positive economic spillovers—and they want to know what can be done to enhance those spillovers. Documenting impacts beyond the treated can be critical in order to garner political and institutional support for projects and policies.

The natural tractor, by Marwa Morgan. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via flickr

The natural tractor, by Marwa Morgan. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via flickr Here’s a recent example: Our LEWIE of LEAP, Ghana’s flagship social cash-transfer program, found that each cedi transferred to a poor household increases local income by as many as 2.5 cedi. (A summary of this evaluation can be found at the UN-FAO’s From Protection to Production website.

Ghana’s President John Dramani Mahama, opening the Pan-African Conference on Inequalities last April, stated: “LEAP has had a positive impact on local economic growth. Beneficiaries spend about 80 percent of their income on the local economy. Every GH1 transferred to a beneficiary has the potential of increasing the local economy by GH2.50.” His goal was clear: to demonstrate that social protection and economic growth can be complements. It appears that LEAP accomplishes both. Read the President’s speech.

Understanding LEWIE is basic to designing rigorous and innovative RCTs. Development projects are likely to create spillovers within treated localities as well as with neighboring ones. LEWIE gives us a way of thinking about these spillovers so that RCTs capture them and avoid control-group contamination and other problems that often raise questions about the validity of experimental results.

Most practitioners and policy makers do not construct LEWIE models or carry out RCTs, but they often find themselves involved in designing interventions and coming up with strategies to evaluate their impacts. Insights from LEWIE studies, which have been carried out for a wide variety of interventions in diverse contexts, can inform their work, at a time when more and more donors include “local economy impacts” in their list of evaluation criteria. LEWIE changes the way we think about impacts, direct or indirect, on people who are so vulnerable that we cannot risk being wrong.

Headline image credit: Highway Fruit Stall, by flöschen. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The post Understanding the local economic impacts of projects and policies appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhere is the global economy headed and what’s in store for its citizens?Why are structural reforms so difficult?Income inequality in the United States

Related StoriesWhere is the global economy headed and what’s in store for its citizens?Why are structural reforms so difficult?Income inequality in the United States

Once upon a quiz

From Little Red Riding Hood to Frozen, the contemporary fairy tales we know today had their beginnings in classic versions that may seem less familiar at first glance. Inspired by Once Upon a Time by Marina Warner, we’re testing your knowledge of well-known favorites with the quiz below. Do you know your Cinderella from your Sleeping Beauty? Try your hand at the questions to see if you have what it takes to be King or Queen of fairy tale lore.

Get Started! Your Score: Your Ranking:We hope you enjoyed taking this quiz. If you still don’t want to leave the world of ‘happily ever afters’, why not discover who the OUP staff chose as their favourite characters from fairy tale history?

Featured image credit: Beauty and the Beast, by Warwick Goble. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Once upon a quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWho is your favourite fairy-tale character?Once upon a time, part 2Once upon a time, part 1

Related StoriesWho is your favourite fairy-tale character?Once upon a time, part 2Once upon a time, part 1

December 23, 2014

A festive Festivus music playlist

As the holiday season is upon us, we thought we would recognize a tradition often lost in the hustle and bustle: Festivus. We’ve compiled our favorite, slightly more obscure seasonal tunes to wish you all a very merry Festivus season.

Metallica’s “Trapped Under Ice”

Darkthrone’s “Where Cold Winds Blow”

Celtic Frost’s “(Beyond the) Northern Winds”

“If Festivus celebrates the airing grievances and the performing of feats of strength by marginalized groups, then what could be more fitting than music that both expresses a host of grievances at the world and embodies performative strength? Here, then, are merely three of the many, many metal songs that both air grievances and perform strength, but further, lyrically embody the coldness of winter.

“Metallica, ‘Trapped Under Ice': If metal gives voice to the bleaker aspects of the human condition, and the image of being trapped in general or under ice in particular qualifies as bleak, then this song is a classic. The blazing speed of this song’s tempo (the sub-genre being ‘speed metal’) conveys the interior panic of the soul trapped in a frozen body: ‘Freezing/Can’t move at all/Screaming/Can’t hear my call/I am dying to live/Cry out/I’m trapped under the ice.’

“Darkthrone, ‘Where Cold Winds Blow': NB: the lyrics include swear words but they are indecipherable. Scandinavian black metal thematizes pre-Christian cultural memories, attempting to reckon with them in the modern age. This song in particular fantasizes about the self-as-warrior, now laid to rest ‘where the cold winds blow.’ Recalling the warrior’s relationships with nature and beast, caught between mind and sword, this song also features blazing speed (specifically, what are called ‘blast beats’), but here that speed normalizes into an energy that evokes wind-swept lands and internal calm within an external world of turmoil.

“Celtic Frost, ‘(Beyond the) Northern Winds': In this song, proto-black metal legends Celtic Frost imagine a time past, when the northern winds and frozen seas provided spiritual and physical solace and transported the protagonist on ‘dark ships’ ‘through gates to eternity,’ but an eternity that is now lost except in memory. The lyrics, fuzzed-out, raspy guitar tone and vocals, peaks and valleys of energy, all became the standard for the sub-genre, but the quasi-punk riffs, formal delineations, and tempo changes recall earlier metal.”

— Scott Gleason, Assistant Editor, Grove Music Online

* * * * *

Dean Martin’s “A Marshmallow World”

“Who doesn’t love a song about waking up in a marshmallow world?! If you need a sugary Festivus treat, this song is it!”

— Raquel Fernandes, Marketing Assistant, Academic/Trade Books

Run DMC’s “Christmas in Hollis”

“Although we’re from Brooklyn, this song is just a classic hip hop take on a Christmas carol gone all the way right and that just gets funnier when my brother-in-law and sister take turns rapping the verses.”

— Ayana Young, Marketing Assistant, Online Marketing

Chris Rae’s “Driving Home for Christmas”

“It always reminds me of the finishing work for the year and driving home to my parents’ house in the North of England (quite literally!) Christmas for me doesn’t start until I hear that song on the big drive home.”

— Emma Turner, Marketing Executive

Fleet Foxes’ “White Winter Hymnal”

The Staves’s “White Winter Trees”

“The first two winter songs that pop into mind are ‘White Winter Hymnal’ by Fleet Foxes, and ‘White Winter Trees’ by the Staves (wintery trees seem to be on the brain today!). They make me think of sunny wintery walks and heading somewhere warm!”

— Olivia Wells, Assistant Commissioning Editor

* * * * *

Cold Specks’ “Winter Solstice”

“Listening to Cold Specks’s voice is like sitting around a log fire on a cold night. This song is one of the standouts on her debut album, and the perfect soundtrack to cosy winter evenings!”

— Barney Cox, Marketing Executive, Online Marketing

Aled Jones’s “Walking in the Air”

“My favourite wintery song is ‘Walking in the Air’ sung by Aled Jones in the movie The Snowman. This film is one of my favourites for this season and whenever I hear it I know the holidays are just around the corner.”

— Hannah Charters, Associate Marketing Manager, Online Marketing

* * * * *

Thurl Ravenscroft’s “You’re a Mean One Mr. Grinch”

“One of my favorite non-religious songs is ‘You’re a mean one Mr. Grinch.’ It is a quintessential tune that sparks memories from my suburban childhood. Dr. Seuss is a cartoon genius with his catchy songs, allegoric stories, and caricature animations.”

— Miki Onwudinjo, Marketing Coordinator, Online Marketing

* * * * *

Sara Bareilles and Ingrid Michaelson’s “Winter Song”

“My a cappella group sang this song my sophomore year of college. We learned it second semester when the winter seemed unending. Though it’s sad at first listen, it now reminds me of gathering around a piano with my closest friends—my favorite thing to do around the holidays.”

— Georgia Brodsky, Marketing Coordinator, Online Marketing

Type O Negative’s “Red Water (Christmas Mourning)”

“Even though Christmas is in the title, I think Frank Costanza would approve of this morose (but actually quite beautiful) song by doom metal band Type O Negative for Festivus celebrations. Released a year before the Festivus episode aired on Seinfeld, ‘Red Water’ features dirge-like appearances of ‘Carol of the Bells’ and ‘God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen’ and the wonderfully evocative lyric by frontman Peter Steele, ‘Black lights hang from the tree/Accents of dead holly’. What can I say, I’m from southwest Florida, I like metal.”

— Meghann Wilhoite, Associate Editor, Grove Music Online

* * * * *

Game Theory’s “Regenisraen”

“Not sure if it totally counts, because its lyrics do mention Christmas (‘Winter houses turning on the glow/Christmas based on Christmas long ago’), but very much from the perspective of someone standing outside of it in the cold. And the chorus repeats the title, a word that the late Scott Miller, frontman for Game Theory and the Loud Family and penner of this song claimed in the liner notes to the 1990 compilation album Tinker to Evers to Chance ‘is Latin for ‘kill the pigs, acid is groovy.” It doesn’t get more Pagan than that.”

— Anna-Lise Santella, Senior Editor, Grove Music Online

Your complete holiday playlist for the rest of us:

Headline image credit: Las Golczewski zima. Photo by Radosław Drożdżewski. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A festive Festivus music playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnie and girl cultureOxford’s top 10 carols of 201410 fun facts about sleigh bells

Related StoriesAnnie and girl cultureOxford’s top 10 carols of 201410 fun facts about sleigh bells

Sherman’s March to the Sea

This week marks the 150th anniversary of the final leg of General William T. Sherman’s victorious “March to the Sea,” which concluded with the Union army’s capture of the all-important port city, Savannah, on 21 December 1864. Sherman’s troops tore across the deep South, ravaging cities from Atlanta to Savannah and overwhelming Southern soldiers and civilians. In The Smell of Battle, the Taste of Siege: A Sensory History of the Civil War, historian Mark M. Smith considers Sherman’s march according to each of the five senses, recalling the sight of 60,000 men charging across Georgia, the sound of cannon fire and hoof beats, and the smell of burning villages. Here, we chart the course of Sherman’s devastating advance and share Smith’s sensory insights into the Union’s storied March to the Sea.

Headline image credit: Sherman’s men destroying railroad in Atlanta, Georgia. Photo by George N. Barnard. Library of Congress.

The post Sherman’s March to the Sea appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Civil War in five sensesBlack Israelites and the meaning of ChanukahA perfume for loneliness

Related StoriesThe Civil War in five sensesBlack Israelites and the meaning of ChanukahA perfume for loneliness

The Lerner Letters: Part 3 – the unknown collaborators

This is the final of a three-part series from Dominic McHugh on the correspondence of Alan Jay Lerner. Read the previous letters to Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews; to Frederick Loewe.

This final post on my collection of the lyricist Alan Jay Lerner focuses on another exciting series of letters: correspondence with famous composers with whom Lerner hoped to work, but never completed a musical. Some of these letters reveal how certain figures – such as Hoagy Carmichael – wrote to Lerner, but were politely declined. With others, he produced some work but then ended the project. Huckleberry Finn, for example, was a movie musical that Lerner started to write with Burton Lane for MGM in the 1950s, but didn’t see to completion (though the screenplay and most of the songs were drafted). He also worked for quite a long time with Arthur Schwartz, writing nine songs for an unmade early movie adaptation of Paint Your Wagon in 1953 and contemplating an adaptation of Li’l Abner (the project later moved on to other writers).

But the two most intriguing aborted collaborations were with two of the most famous composers who dominated twentieth-century Broadway: Richard Rodgers and Andrew Lloyd Webber. After the retirement of Frederick Loewe in 1960, Lerner started to look for a new composer to work with. Rodgers seemed a natural choice, since he too needed a new collaborator, following the death of Oscar Hammerstein II. They set to work on a musical called I Picked a Daisy, which dealt with reincarnation and extra-sensory perception. Though only a few notes between them appear in the book, it is striking how intimate the correspondence is, for instance:

Dear, dear Dick:

I hope what will come between these covers will make this one of the happiest of your many happy years.

Affectionately,

Alan

* * * * *

Dear Dick:

Here are the first two scenes. The rest needs cutting. I’ll mail them on to you in a day or two.

XXX

Alan

Sadly, the partnership didn’t work out, though the pair managed to draft nine songs together. Rodgers withdrew, and Lerner replaced him with Burton Lane. the show was retitled On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, and it became a modest success.

At the end of his life, Lerner was invited to write the lyrics for one of the most successful musicals of the past century: The Phantom of the Opera. Yet, as the following letter reveals, Lerner’s participation was cut short for reasons beyond anybody’s control:

Who would have thought it? Instead of writing The Phantom of the Opera, I end up looking like him.

But, alas, the inescapable fact is I have lung cancer. After fiddling around with pneumonia they finally reached the conclusion that it was the big stuff.

I am deeply disconsolate about The Phantom and the wonderful opportunity it would have been to write with you. But I will be back! Perhaps not on time to write The Phantom, but as far as I am concerned this is a temporary hiccup. I have a 50/50 chance medically and a 50/50 chance spiritually. I shall make it. I have no intention of leaving my beautiful wife, this beautiful life and all of the things I still have to write. As far as I am concerned it is a challenge, and I fear nothing.

Lerner’s final decade or so was filled with artistic disappointments, including the flops 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Carmelina, and Dance a Little Closer. But who knows? Perhaps this project, cut brutally short by Lerner’s fatal cancer, would have brought the writer the late-career success that he deeply longed for. Either way, with this new collection of letters, we can enjoy a legacy of beautiful prose, full of new insights into the extraordinary career of this award-winning writer.

Headline Image: Old Letters. CC0 via Pixabay

The post The Lerner Letters: Part 3 – the unknown collaborators appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Lerner Letters: Part 2 – Lerner and LoeweAnnie and girl cultureA holiday food tour

Related StoriesThe Lerner Letters: Part 2 – Lerner and LoeweAnnie and girl cultureA holiday food tour

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers