Oxford University Press's Blog, page 716

January 4, 2015

A very short trivia quiz

In order to celebrate Trivia Day, we have put together a quiz with questions chosen at random from Very Short Introductions online. This is the perfect quiz for those who know a little about a lot. The topics range from Geopolitics to Happiness, and from French Literature to Mathematics. Do you have what it takes to take on this very short trivia quiz and become a trivia master? Take the quiz to find out…

Get Started! Your Score: Your Ranking:We hope you enjoyed testing your trivia knowledge in this very short quiz.

Headline image credit: Pondering Away. © GlobalStock via iStock Photo.

The post A very short trivia quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMisunderstanding World War IIDiscovering microbiologyWhy be rational (or payday in Wonderland)?

Related StoriesMisunderstanding World War IIDiscovering microbiologyWhy be rational (or payday in Wonderland)?

Speak of the Devil: Satan in imaginative literature

Al Pacino is John Milton. Not John Milton the writer of Paradise Lost, although that is the obvious in-joke of the movie The Devil’s Advocate (1997). No, this John Milton is an attorney and — in what thus might be another obvious in-joke — he is also Satan, the Prince of Darkness. In the movie, he hires a fine young defense attorney, Kevin Lomax (Keanu Reeves), and offers him an escalating set of heinous — and high-profile — cases to try, a set of ever-growing temptations if you will. What will happen to Kevin in the trials to come?

The Devil is a terrifying foe in this film, which should not surprise us. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote in the Duino Elegies that “Every angel is terrifying.” We sometimes forget that our devils were angels first. Tales of angels fallen from goodness particularly bother us, and Satan’s rebellion is supposed to have inspired the most terrible of conflicts. In The Prophecy (1995), Simon (Eric Stoltz) describes the conflict in Heaven and its consequences: “I remember the First War, the way the sky burned, the faces of angels destroyed. I saw a third of Heaven’s legion banished and the creation of Hell. I stood with my brothers and watched Lucifer Fall.”

The Doctor Who episode “The Satan Pit” (2006) also retells the story of this conflict. The Doctor (David Tennant) encounters The Beast (voiced by Gabriel Woolf) deep within a planet. The Beast tells The Doctor that he comes from a time “Before time and light and space and matter. Before the cataclysm. Before this universe was created.” In this time before Creation, The Beast was defeated in battle by Good and thrown into the pit, an origin that clearly matches that of the Satan whose legend he is said to have inspired: “The Disciples of the Light rose up against me and chained me in the pit for all eternity.”

Satan, photo by Adrian Scottow, CC by 2.0 via Flickr

Satan, photo by Adrian Scottow, CC by 2.0 via Flickr A majority of Americans believe in Satan, a personified cosmic force of evil, but why? The Hebrew and Christian testaments say almost nothing about the Devil. As with Heaven, Hell, Purgatory, angels, and other topics related to the afterlife, most of what we know — or believe we know — about Satan comes from human imagination, not from holy scripture.

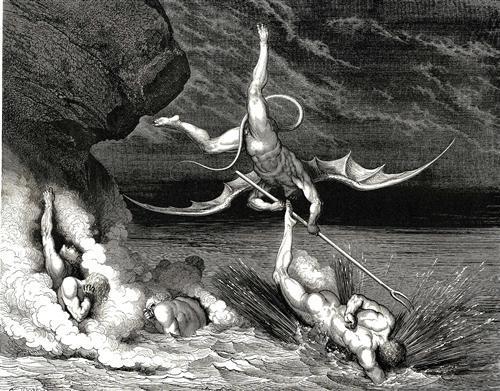

We have used stories, music, and art to flesh out the scant references to the Devil in the Bible. We find Satan personified in medieval mystery plays and William Langland’s Piers Plowman (ca. 1367), and described in horrifying—and heartbreaking—detail in Dante’s Inferno: “If he was fair as he is hideous now, / and raised his brow in scorn of his creator, / he is fit to be the source of every sorrow.” (Inferno 34.34-36) We find the Devil represented in the art of Gustave Dore and William Blake, and in our own time, represented graphically in the comics The Sandman, Lucifer, and disguised as “The First of the Fallen” in Hellblazer. We watch Satan prowling the crowds for the entirety of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004), and arriving for an earthly visit at the end of Constantine (2005).

And we are terrified. Like him or not, the Devil is the greatest villain of all time. Who else stands for every quality and condition that we claim to despise? Who else helps us to understand why the world contains evil — and why we are ourselves sometimes inclined toward it?

The Inferno Canto 22, Gustave Dore, Public Domain via WikiArt

The Inferno Canto 22, Gustave Dore, Public Domain via WikiArt We also work out these questions through characters who are not explicitly Satan, but who embody supernatural or preternatural evil. If writers and artists can be said to create “Christ figures,” then it makes sense that they might also create “Satan figures.” Professor Weston in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra space trilogy, Sauron in The Lord of the Rings trilogy of books and films, Darkseid (the ruler of the hellish planet Apokolips in DC Comics), Lord Voldemort (The Dark Lord of the Harry Potter mythos), and Thomas Harris’s Hannibal Lecter all fit this profile. Such characters — dark, scheming, and because of their tremendous capacity for evil, all but all-powerful — may tell us as much about evil as our stories of Satan do. In fact, Mads Mikkelsen, who plays Lecter in the television series Hannibal, makes that comparison explicit:

“I believe that Hannibal Lecter is as close as you can come to the devil, to Satan. He’s the fallen angel. His motives are not banal reasons, like childhood abuse or junkie parents. It’s in his genes. He finds life is most beautiful on the threshold to death, and that is something that is much closer to the fallen angel than it is to a psychopath. He’s much more than a psychopath, and there is a fascination for us.”

In our consumption of narratives and images of the Devil, we are trying to work out what — if anything — the devil means. Even if we don’t believe in an actual fallen angel who rules this world and contends with God, most of us have come to accept that Satan is an emotionally-satisfying explanation for all that goes wrong in real life. The stories in which Satan chills us prove this beyond doubt. What could be more frightening than Al Pacino’s John Milton plotting the destruction of our hero in The Devil’s Advocate, his schemes only moments away from coming to fruition?

Evil is real, and has real power. We see that in the daily headlines and history books, in our own lives and even in ourselves. To find out where that evil comes from — to understand why human beings do things that are so clearly wrong — perhaps we do need to wrestle with the Devil, even if the only way we encounter him is as a character in a story.

The post Speak of the Devil: Satan in imaginative literature appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAlmost paradise: heaven in imaginative literatureAtheism: Above all a moral issueThe commodification and anti-commodification of yoga

Related StoriesAlmost paradise: heaven in imaginative literatureAtheism: Above all a moral issueThe commodification and anti-commodification of yoga

January 3, 2015

Atheism: Above all a moral issue

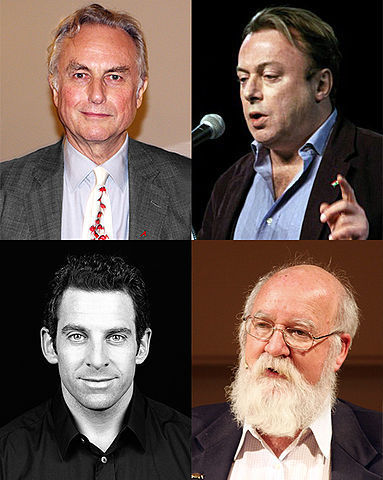

The New Atheists – Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Dan Dennett, and the late Christopher Hitchens – are not particularly comfortable people. The fallacies in their arguments beg to be used in classes on informal reasoning. The narrowness of their perspectives are remarkable even by the standards of modern academia. The prejudices against those of other cultures would be breathtaking even in the era when Britannia ruled the waves. But there is a moral fervor unknown outside the pages of the Old Testament. And for this, we can forgive much.

Atheism is not just a matter of the facts – does God exist or not? It is as much, if not more, a moral matter. Does one have the right to believe in the existence of God? If one does, what does this mean morally and socially? If one does not, what does this mean morally and socially?

Now you might say that there has to be something wrong here. Does one have the right to believe that 2+2=4? Does one have the right to believe that the moon is made of green cheese? Does one have the right to believe that theft is always wrong? Belief or non-belief in matters such as these is not a moral issue. Even though it may be that how you decide is a moral issue or something with moral implications. How should one discriminate between a mother stealing for her children and a professional burglar after diamonds that he will at once pass on to a fence?

But the God question is rather different, because, say what you like, it is nigh impossible to be absolutely certain one way or the other. Even Richard Dawkins admits that although he is ninety-nine point many nines certain that there is no god, to quote one of the best lines of that I-hope-not-entirely-forgotten review, Beyond the Fringe, there is always that little bit in the bottom that you cannot get out. There could be some kind of deity of a totally unimaginable kind. As the geneticist J. B. S. Haldane used to say: “My own suspicion is that the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.”

(Clockwise from top left} Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Daniel Dennett, and Sam Harris. “Four Horsemen” by DIREKTOR. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

(Clockwise from top left} Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Daniel Dennett, and Sam Harris. “Four Horsemen” by DIREKTOR. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. So in some ultimate sense the God question is up for grabs, and how you decide is a moral issue. As the nineteenth-century English philosopher, William Kingdom Clifford, used to say, you should not believe anything except on good evidence. But the problem here is precisely what is good evidence – faith, empirical facts, arguments, or what? Decent, thoughtful people differ over these and before long it is no longer a simple matter of true or false, but of what you believe and why; whether you should or should not believe on this basis; and what are going to be the implications of your beliefs, not only on your own life and behavior but also on the lives and behaviors of other people.

If you go back to Ancient Greece, you find that above all it is the moral and social implications of non-belief that worried people like Plato. In the Laws, indeed, he prescribed truly horrendous restrictions on those who failed to fall in line – and this from a man who himself had very iffy views about the traditional Greek views on the gods and their shenanigans. You are going to be locked up for the rest of your life and receive your food only at the hands of slaves and when you die you are going to be chucked out, unburied, beyond the boundaries of the state.

Not that this stopped people from bringing up a host of arguments against God and gods, whether or not they thought that there truly is nothing beyond this world. Folk felt it their duty to show the implausibility of god-belief, however uncomfortable the consequences. And this moral fervor, either in favor or against the existence of a god or gods, continues right down through the ages to the present. Before Dawkins, in England in the twentieth century the most famous atheist was the philosopher Bertrand Russell. His moral indignation against Christianity in particular – How dare a bunch of old men in skirts dictate the lives of the rest of us? — shines out from every page. And so it is to the present. No doubt, as he intended, many were shocked when, on being asked in Ireland about sexual abuse by priests, Richard Dawkins said that he thought an even greater abuse was bringing a child up Catholic in the first place. He is far from the first to think in this particular way.

Believers think they have found the truth and the way. Non-believers are a lot less sure. What joins even – especially – the most ardent of partisans is the belief that this is not simply a matter of true and false. It is a matter of right and wrong. Abortion, gay marriage, civil rights – all of these thorny issues and more are moral and social issues at the heart of our lives and what you believe about God is going to influence how you decide. Atheism, for or against, matters morally.

Featured image credit: “Sky clouds” by 12345danNL. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Atheism: Above all a moral issue appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe commodification and anti-commodification of yogaGroup beliefThe food we eat: A Q&A on agricultural and food controversies

Related StoriesThe commodification and anti-commodification of yogaGroup beliefThe food we eat: A Q&A on agricultural and food controversies

Meet Ellen Carey, Senior Marketing Executive for Social Sciences

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into work in our offices around the globe, so we are excited to bring you an interview with Ellen Carey, Senior Marketing Executive for Social Sciences books. Ellen started working at Oxford University Press in February 2013 in Law Marketing, before moving to the Academic Marketing team.

What publication do you read regularly to stay up to date on industry news?

I work on the Social Sciences lists, which includes Business, Politics, and Economics, and lots of the books I work on are very relevant to current affairs. I tend to read the top news stories in The Economist, Financial Times, BBC News website, The Guardian, and The Times every morning. This especially helps with commissioning newsworthy blog posts and writing tweets for the @OUPEconomics Twitter feed. I’ve always been interested in current affairs, and this is something I really enjoy.

What is the most important lesson you learned during your first year in the job?

That everyone makes mistakes and there’s usually a way to fix them, and lots of people are willing to help. Though we obviously try to get things right the first time round!

What is your typical day like at OUP?

My day starts with a huge cup of coffee and a catch up with the team. My day is divided between author correspondence, marketing plans, events and conferences, project work, and social media.

What is the strangest thing currently on your desk?

I have a promotional penguin toy from an insurance law firm – his name is André 3000 – which was given to me by one of my friends who works for a law firm.

Ellen Carey

Ellen Carey What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

This afternoon I’ll be working on the Politics catalogue for 2015.

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

It would be a prima ballerina in the Royal Ballet – that would be the dream!

How would you sum up your job in three words?

Busy, challenging, diverse.

Favourite animal?

I love cats! I have a really old, grumpy, 17-year-old cat called Paddy, and my friends and I regularly send Snapchat updates of our cats. I like to be kept in the know with what’s going on in Pickles’ and Mag’s lives.

What is the most exciting project you have been a part of while working at OUP?

The Economics social media group. It’s been really exciting to be part of the team that set up and launched the Economics Twitter feed, and it was great to see us reach 1,000 followers in six months. I’ve also really enjoyed working with colleagues to commission blog posts and we’re looking forward to increasing our social media activities.

What is your favourite word?

Pandemonium. My Mum read me the Mr Men and Little Miss books when I was little, and I always remember this line from Mr Tickle because she’d put on a funny voice: “There was a terrible pandemonium.”

The post Meet Ellen Carey, Senior Marketing Executive for Social Sciences appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy are structural reforms so difficult?Making choices between policies and real livesUnderstanding the local economic impacts of projects and policies

Related StoriesWhy are structural reforms so difficult?Making choices between policies and real livesUnderstanding the local economic impacts of projects and policies

The afterlife of the Roman Senate

When the Senate of the Free City of Krakow oversaw the renovation of the main gate to the Royal Castle in 1827, it commemorated its action with an inscription: SENATUS POPULUSQUE CRACOVIENSIS RESTITUIT MDCCCXXVII. The phrase ‘Senatus Populusque Cracoviensis’ [the Senate and People of Krakow], and its abbreviation SPQC, clearly and consciously invoked comparison with ancient Rome and its structures of government: Senatus Populusque Romanus, the Senate and People of Rome. Why did a political entity created only in 1815 find itself looking back nearly two millennia to the institutional structures of Rome and to its Senate in particular?

The situation in Krakow can be seen as a much wider phenomenon current in Europe and North America from the late eighteenth century onwards, as revolutionary movements sought models and ideals to underpin new forms of political organisation. The city-states of classical antiquity offered examples of political communities which existed and succeeded without monarchs and in the case of the Roman Republic, had conquered an empire. The Senate was a particularly intriguing element within Rome’s institutional structures. To the men constructing the American Constitution, it offered a body which could act as a check on the popular will and contribute to political stability. During the French Revolution, the perceived virtue and courage of its members offered examples of civic behaviour. But the Roman Senate was not without its difficulties. Its members could be seen as an aristocracy; and for many historians, its weaknesses were directly responsible for the collapse of the Roman Republic and the establishment of the Empire.

In these modern receptions of the Roman Senate, the contrast between Republican Rome and the Roman Empire was key. The Republic could offer positive models for those engaged in reshaping and creating states, whilst the Roman Empire meant tyranny and loss of freedom. This Tacitean view was not, however, universal in the imperial period itself. Not only was the distinction we take for granted, between Republic and Empire, slow to emerge in the first century A.D.; senatorial writers of the period could celebrate the happy relationship between Senate and Emperor, as Pliny the Younger does in his Panegyricus and many of his letters. Indeed, by late antiquity senators could pride themselves on the improvement of their institution in comparison with its unruly Republican form.

The reception history of the Republican Senate of ancient Rome thus defies a simple summary. Neither purely positive nor purely negative, its use depended and continues to depend on a variety of contextual factors. But despite these caveats, the Roman Senate can still offer us a way of thinking about how we choose our politicians, what we ask them to do, and how we measure their achievements. This continuing vitality reflects too the paradoxes of the Republican institution itself. Its members owed their position to election, yet often behaved like a hereditary aristocracy; a body offering advice in a state where the citizen body was sovereign, it nonetheless controlled vast swathes of policy and action and asserted it could deprive citizens of their rights. These peculiarities contributed to making it an extraordinarily fruitful institution in subsequent political theory.

Headline image credit: Representation of a sitting of the Roman senate: “Cicero Denounces Catiline.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The afterlife of the Roman Senate appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow the US government invented and exploited the “patent troll” hold-up mythAn enigma: the codes, the machine, the manAdderall and desperation

Related StoriesHow the US government invented and exploited the “patent troll” hold-up mythAn enigma: the codes, the machine, the manAdderall and desperation

January 2, 2015

Getting to know Reference Editor Robert Repino

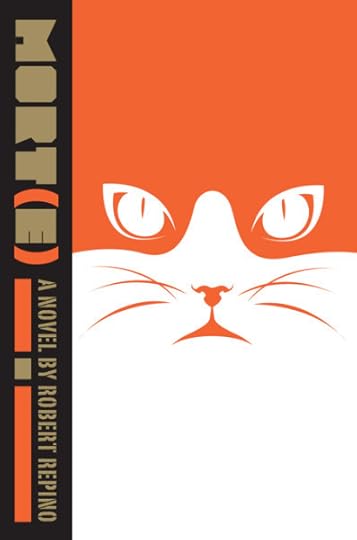

In an effort to introduce readers to our global staff and life here at Oxford University Press (OUP), we are excited to bring you an interview with Robert Repino, an editor in the reference department. His debut novel, Mort(e), will publish in January with Soho Press.

When did you start working at OUP?

October 2006.

Can you tell us a bit about your current position here?

I am the editor of three online resource centers: Oxford Islamic Studies Online (OISO), Oxford Biblical Studies Online (OBSO), and the Oxford African American Studies Center (AASC). The term editor, though, is a bit misleading, since I spend more time managing projects than actually editing text. The main part of my job is recruiting scholars in different fields to write or review new content for the site, which consists mostly of encyclopedia-style articles, but can also include primary source documents, editorials, and teaching aids. I also plan out the different areas of focus for each year. For example, this year we obviously need more content covering the situation in Syria and Iraq for Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Finally, I coordinate with the Marketing team to bring more attention to the sites through blog posts, interviews, and partnerships with academic organizations.

You are about to publish your first novel. Where did your inspiration come from for the book?

I had a dream one night in which aliens landed on earth and somehow altered all of the non-human animals to make them intelligent. The animals could speak, walk upright, and form armies that could fight the humans. It was very alarming—I remember in particular an image of a saucer hovering over my childhood home, with animal soldiers exiting it, marching down a giant gangplank into my backyard.

Robert Repino

Robert RepinoAs I thought about it in those first few moments, the idea reminded me of all the big stories I’ve wanted to write since I was much younger. Like many nerdy kids who grew up watching Star Wars and Star Trek, I had always wanted to create some kind of science fiction epic, only I wanted mine to be a little subversive, and I wanted it to comment on politics, religion, and morality. Very quickly, I decided to frame this story around a sentient animal fighting in a rebellion against humanity. I turned the aliens into ants because I wanted them to have a good reason for being angry with humans. And I grounded the story in the unlikely relationship between a cat and a dog. In fact, these characters are based on the cat I grew up with, and the dog who was his playmate. Perhaps because of this friendship, my cat apparently came to believe he was a dog. The scene in the novel in which the cat “guards” the house against a babysitter is based on a true story. (We never saw the babysitter again after that.)

Did the projects that you are working on here at OUP influence you at all while writing your novel?

Yes, especially with regard to religious studies. The Queen of the ants believes that humans are evil because they see themselves as the center of the universe, the species chosen by their creator to rule over the world. Meanwhile, the main character, Mort(e), discovers that he is the prophesied savior whom the humans believe will end the war and destroy the Queen. As a result, the novel devotes a lot of space to exploring the power of religious beliefs, the promise (or threat) of the afterlife, the cryptic nature of sacred scriptures, and the difficult and often lonely decision one faces when rejecting a religion in certain contexts. In some ways, Mort(e) is an inversion of the prophet/savior archetype, as he doesn’t believe in the mythology that the humans have crafted around his life story. At the same time, he recognizes the power of these religious traditions, and accepts that spiritual experience is perhaps universal among all sentient beings. As you can imagine, a lot of this stuff is in Oxford Islamic Studies Online and Oxford Biblical Studies Online, and scholars of religious studies will probably recognize some of the terminology and imagery. (Plus, the epigraph is from Numbers 22:28–31. Look that up, and you’ll see why it’s quite appropriate.)

Mort(e), Rob’s debut novel

Mort(e), Rob’s debut novelHas your experience as an author impacted the way that you edit?

I think so. It took me a year to write the book, but nearly four years to revise, edit, and proofread it. So, I now understand, after much resistance, that editing is writing. It can be hard to accept that sometimes. But I think I’m better at seeing the big picture in a given article or essay than I used to be. And, very often, I understand a simple cut solves a ton of problems.

What was the most surprising thing that you learned?

A novelist who was kind enough to blurb the book told me that a scene in Mort(e) in which a giant rat throws up at the sight of a corpse is not accurate. Apparently, rats and horses are the only mammals that cannot vomit. I’ll just leave that for you to ponder.

Do you have any advice for first time authors?

Write as much as you possibly can. For sheer volume—and therefore, more practice—short stories are easier to work on than novels. (Novels can become extremely discouraging between pages 30 and 50.) Write a story, and when you’re finished, celebrate by writing another. There is a great speech by Ray Bradbury that is available on YouTube in which he challenges people to write a short story a week (or a month, whatever) for a year. At the end of that year, most of your work will stink. Some of it might be good. But no matter what, you will be a much better writer.

Any suggestions for others working in publishing with dreams of finishing their novel?

I think that finishing a novel can be daunting for anyone who has a full-time job. It’s so important to set up a time of day to write that works for you, and to stick to that as best as you can. And, to occasionally sequester yourself on a weekend if you have to. Even writing 100 words that you later delete is better than writing nothing (and then binge watching a reality show). And then, when you have finally powered through, you have to embrace the revision process, which can often require reaching out to people you trust for help. This being publishing, you should be able to find someone.

The post Getting to know Reference Editor Robert Repino appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTop ten OUPblog posts of 2014 by the numbersThe commodification and anti-commodification of yogaResidency training and specialty mis-match

Related StoriesTop ten OUPblog posts of 2014 by the numbersThe commodification and anti-commodification of yogaResidency training and specialty mis-match

The commodification and anti-commodification of yoga

Nearly all of us who live in urban areas across the world know someone who “does yoga” as it is colloquially put. And should we choose to do it ourselves, we need not travel farther than a neighborhood strip mall to purchase a yoga mat or attend a yoga class.

The amount of spending on yoga depends largely on brand. A consumer can purchase a pair of yoga pants with an unfamiliar brand at the popular retail store Target for $19.99 or purchase a pair from Lululemon, a high-end yoga-apparel brand that on average charges $98 for yoga pants. On Amazon, the consumer can choose from a variety of yoga mats with unfamiliar brands for under $20, or she can go to a specialty shop and purchase a stylish Manduka-brand yoga mat, which will cost as much as $100. And all that does not include the cost of yoga classes, which widely range from $5 to over $20 per class.

If a consumer is really dedicated to investing money in yoga, for thousands of dollars she can purchase a spot in a yoga retreat in locations throughout the United States, in Europe, or even in the Bahamas or Brazil, with yoga teachers marketing their own popular brands, such as Bikram Choudhury, whose brand is Bikram Yoga. Spending on yoga is steadily increasing. In the United States alone, spending doubled from $2.95 billion to $5.7 billion from 2004 to 2008 and climbed to $10.3 billion between 2008 and 2012.

The dandayamana-bibhaktapada paschimotthana asana (standing separate leg stretching posture). Photographed by Michael Petrachenko. (Images courtesy of Kirsten Greene.)

The dandayamana-bibhaktapada paschimotthana asana (standing separate leg stretching posture). Photographed by Michael Petrachenko. (Images courtesy of Kirsten Greene.)Consumers convey the meaning of yoga, however, not only through what products and services they choose to purchase but also what they choose not to purchase. In other words, consumption can require exchange of money and commodities, and the amount of money spent on commodities largely depends on the brand choices of individual consumers. However, consumption can also lack an exchange of money and commodities. Many contemporary yoga practitioners, in fact, oppose the commodification of yoga by choosing free yoga services and rejecting certain yoga products.

For the founder of postural yoga brand Yoga to the People, Greg Gumucio, and those who choose the services associated with his brand, yoga’s meaning transcends its commodities. The anti-commodification brand of Yoga to the People signifies, quite directly, a very particular goal: a better world. It is believed that is possible as more and more people become self-actualized or come into their full being—yoga is “becoming”—through strengthening and healing their bodies and minds. The individual who chooses Yoga to the People still acts as a consumer even if consumption does not require the exchange of money. The consumer chooses Gumucio’s brand as opposed to others because of that brand’s success in capturing what yoga means to him or her.

Some yoga practitioners reject the yoga mat for its perceived over-commodification. The mat, for most practitioners of postural yoga, is a necessity, not just because it allows one to perform postures without slipping or to mark one’s territory in a crowded class, but also because it signifies various non-utilitarian meanings. The mat signifies a “liminal space” set apart from day-to-day life as one participates in a self-developmental ritual of rigorous physical practice. It is also often a status symbol. But yoga insiders who reject mats argue that they are not necessary, that they interfere with practice, and that they are simply commodities without any profound meaning. It is worth noting that the first purpose-made yoga mat was not manufactured and sold until the 1990s. Yoga practitioners who reject the mat choose brands of yoga that do not require the mat, such as Laughing Lotus, because those brands are believed to better signify the true meaning of yoga. For them, the meaning of yoga is experiential and transcends ownership of a commodity as seemingly arbitrary as a mat.

The post The commodification and anti-commodification of yoga appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs yoga religious?Residency training and specialty mis-matchBob Hope, North Korea, and film censorship

Related StoriesIs yoga religious?Residency training and specialty mis-matchBob Hope, North Korea, and film censorship

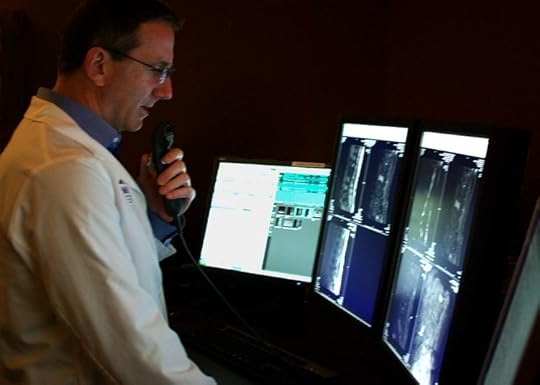

Residency training and specialty mis-match

The country has long had too many specialists and subspecialists, so the common wisdom holds. And, the common wisdom continues, the fault lies with the residency system, which overemphasizes specialty medicine and devalues primary care, in flagrant disregard of the nation’s needs.

It was not always that way. Before World War II, medical education practiced birth control with regard to the production of specialists. Roughly 80% of doctors were general practitioners, only 20% specialists. This was because the number of residency positions (which provided the path to specialization) was strictly limited. The overwhelming majority of medical graduates had to take rotating internships, which led to careers in general practice.

After World War II, the growth of specialty medicine could not be contained. The limit on residency positions was removed; residency positions became available to all who wanted them. Hospitals needed more and more residents, as specialty medicine grew and medical care became more technologically complex and scientifically sophisticated. Most medical students were drawn to the specialties, which they found more intellectually exciting and professionally fulfilling than general practice (which in the 1970s became called primary care). The satisfaction of feeling they were in command of their area of practice as an additional draw, as was greater social prestige and higher incomes. By 1960, over 80% of students were choosing careers in specialty medicine — a figure that has not changed through the present.

The transformation of residency training from a privilege to a right embodied the virtues of a democratic free enterprise system, where individuals were free to choose their own careers. In medicine, there were now no restrictions on professional opportunities. Individual hospitals and residency programs sought residents on the basis of their particular service needs and educational interests, while students sought the field that interested them the most. The result was that specialty and subspecialty medicine emerged triumphant, while primary care languished, even after the development of family practice residencies converted primary care into its own specialty.

Radiologist in San Diego CA by Zackstarr. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Radiologist in San Diego CA by Zackstarr. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.This situation poses a perplexing dilemma for the residency system. More and more doubts have surfaced about whether graduate medical education is producing the types of doctors the country needed. No one doubts that having well-trained specialists is critically important to the nation’s welfare, but fear that graduate medical education has overshot the mark. Ironically, no one knows for sure what the proper mix of specialists and generalists should be. A popular consensus is a 50-50 mix, but that is purely a guess. One thing is clear, however: The sum of individual decisions is not meeting perceived public needs.

At the root of the problem is that fundamental American values conflict with each other. On the one hand, the ascendance of specialty practice service serves as a testimony to the power of American individualism and personal liberty. Hospitals and medical students make decisions on the basis of their own interests, desires, and preferences, not on the basis of national needs. The result is the proliferation of specialty practice to the detriment of primary care. This situation occurs only in the United States, for the rest of the Western world makes centralized decisions to match specialty training with perceived workforce needs. Medical students in other countries are not guaranteed residency positions in a specialty of their choice, or even a specialty residency in the first place.

On the other hand, by not producing the types of doctors the country is thought to need, there is growing concern that graduate medical education is not serving the national interests. This would be a problem for any profession, given the fact that a profession is accountable to the society that supports it and grants it autonomy for the conduct of its work. This poses an especially thorny dilemma for medicine, in view of the large amounts of public money graduate medical education receives. Some medical educators worry that if the profession itself cannot achieve a specialty mix more satisfactory to the public, others will do it for them. Various strategies have been tried — for instance, loan forgiveness or higher compensation for those willing to work in primary care. However, none of these strategies have succeeded — in part because of the professional lure of the specialties, and because of the traditional American reluctance to restrict an individual’s right to make his own career decisions. Thus, the dilemma continues.

Headline image credit: Hospital at Scutari, 1856. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Residency training and specialty mis-match appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAchieving patient safety by supervising residentsWhat do nurses really do?The practical genomics revolution

Related StoriesAchieving patient safety by supervising residentsWhat do nurses really do?The practical genomics revolution

Misunderstanding World War II

The Second World War affected me quite directly, when along with the other students of the boarding school in Swanage on the south coast of England I spent lots of time in the air raid shelter in the summer of 1940. A large German bomb dropped into the school grounds fortunately did not explode so that we survived. To process for entry into the United States, I then had to go to London and thus experienced the beginnings of the Blitz before crossing the Atlantic in September. Perhaps this experience had some influence on my deciding to write on the origins and course of the Second World War.

Over the years, there have been four trends in the writing on that conflict that seemed and still seem defective to me. One has been the tendency to overlook the fact that the earth is round. The Axis Powers made the huge mistake of failing to engage this fact during the war and never coordinated their strategies accordingly, and too many have followed this bad example in looking at the conflict in retrospect. Events in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific often influenced each other, and it has always seemed to me that it was the ability of Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt to engage the global reality that made a significant contribution to the victory of the Allies.

A second element in distortions of the war has been the influence of mendacious memoirs of German generals and diplomats, especially those translated into English. The enthusiasm of Germany’s higher commanders for Adolf Hitler and his projects vanished in the postwar years as they blamed him for whatever went wrong, imagined that it was cold and snowed only on the German army in Russia, and evaded their own involvement in massive atrocities against Jews and vast numbers of other civilians. They were happy to accept bribes, decorations, and promotions from the leader they adored; but in an interesting reversal of their fakery after the First World War, when they blamed defeat on an imaginary “stab-in-the-back,” this time they blamed their defeat on the man at the top. Nothing in their memoirs can be believed unless substantiated by contemporary evidence.

A third contribution to misunderstanding of the great conflict comes from an all too frequent neglect of the massive sources that have become available in recent decades. It is much easier to manufacture fairy tales at home and in a library than to dig through the enormous masses of paper in archives. A simple but important example relates to the dropping of two atomic bombs on Japan. One can always dream up alternative scenarios, but working through the mass of intercepted and decoded Japanese messages is indeed tedious work. It does, however, lead to the detailed recommendation of the Japanese ambassador in Moscow in the summer of 1945 urging surrender rather than following the German example of fighting to the bitter end, and to the reply from Tokyo thanking him for his advice and telling him that the governing council had discussed and unanimously rejected it.

Nagasaki, Japan. Photo by Cpl. Lynn P. Walker, Jr. (Marine Corps). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Nagasaki, Japan. Photo by Cpl. Lynn P. Walker, Jr. (Marine Corps). Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsA fourth type of misunderstanding comes from a failure to recognize the purpose of the war Germany initiated. Hitler did not go to war because the French refused to let him visit the Eiffel tower, invade the Soviet Union because Joseph Stalin would not let the German Labor Front place a “Strength through Joy” cruise ship on the Caspian Sea, or have a murder commando attached to the headquarters of Erwin Rommel in Egypt in the summer of 1942 to dismantle one of the pyramids for erection near Berlin renamed “Germania.” The purpose of the war was not, like most prior wars, for adjacent territory, more colonies, bases, status, resources, and influence. It was for a demographic revolution on the globe of which the extermination of all Jews was one facet in the creation of a world inhabited solely by Germanic and allegedly similar peoples. Ironically it was the failure of Germany’s major allies to understand this concept that led them over and over again, beginning in late 1941, to urge Hitler to make peace with the Soviet Union and concentrate on crushing Great Britain and the United States. World War II was fundamentally different from World War I and earlier conflicts. If we are ever to understand it, we need to look for something other than the number popularly attached to it.

Featured image credit: Air raid shelter, by Rasevic. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Misunderstanding World War II appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Battle of the BulgeBehind Korematsu v. United StatesThe “comfort women” and Japan’s honor

Related StoriesThe Battle of the BulgeBehind Korematsu v. United StatesThe “comfort women” and Japan’s honor

January 1, 2015

Top ten OUPblog posts of 2014 by the numbers

We’re kicking off the new year with a retrospective on our previous one. What was drawing readers to the OUPblog in 2014? Apparently, a passion for philosophy and a passion for lists. Here’s our top posts published in the last year, in descending order, as judged by the total number of pageviews they attracted.

(10) “True or false? Ten myths about Isaac Newton” by Sarah Dry

(9) “A map of Odysseus’s journey”

(8) “10 facts about the saxophone and its players” by Maggie Belnap

(7) “Five things 300: Rise of an Empire gets wrong” by Paul Cartledge

(6) “Coffee tasting with Aristotle” by Anna Marmodoro

(5) “Reading Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations with a modern perspective” by Christopher Gill

(4) “Is Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?” by Cherif Bassioun

(3) “25 recent jazz albums you really ought to hear” by Ted Gioia

(2) “The impossible painting” by Roy T. Cook

(1) “Why study paradoxes?” by Roy T. Cook

Older (pre-2014) blog posts that continued to attract attention this year include: “10 facts about Galileo Galilei” by Matt Dorville; “Ten things you might not know about Cleopatra” by Anne Zaccardelli; “Cleopatra’s True Racial Background (and Does it Really Matter?)” by Duane W. Roller; “Quantum Theory: If a tree falls in forest…” by Jim Baggott; “SciWhys: Why are we told always to finish a course of antibiotics?” by Jonathan Crowe; and many more.

Headline image credit: Bunting Flag by Raul Varela – @Shonencmyk via The Pattern Library.

The post Top ten OUPblog posts of 2014 by the numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBob Hope, North Korea, and film censorshipThe practical genomics revolutionMonthly etymology gleanings for December 2014, Part 1

Related StoriesBob Hope, North Korea, and film censorshipThe practical genomics revolutionMonthly etymology gleanings for December 2014, Part 1

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers