Oxford University Press's Blog, page 718

December 29, 2014

Defining the humanities

In December 2014, OxfordDictionaries.com added numerous new words and definitions to their database, and we invited experts to comment on the new entries. Below, Scott A. Trudell, Assistant Professor of English at the University of Maryland, College Park, discusses digital humanities. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Oxford Dictionaries or Oxford University Press.

Can you think of a professional field nowadays where it is unexpected or controversial to use computers? Before sitting down to write this post, I submitted an online maintenance request to fix a towel rack in my apartment and placed an online order to replenish my supply of oatmeal. When I don my tweed and head into my humanities department, it’s hardly surprising to find colleagues analyzing digital culture and using digital tools.

Yet there has been a lot of controversy and alarmism over what exactly the digital humanities “is” — there’s even a website that generates a new answer to “What Is the Digital Humanities” each time you load the page. If the question burns in you, I refer you to freely available essays by my colleague Matthew Kirschenbaum, to the recently published edited collection Debates in the Digital Humanities, and to a critique of “The Meaning of the Digital Humanities” by Alan Liu. Don’t expect fixed answers: a panel at the Modern Language Association in Vancouver next month, called “Disrupting the Digital Humanities,” is one of many ongoing efforts to “open the digital humanities more fully to its fringes and outliers,” resisting the impulse to gatekeeping and defining.

It can be easy to forget that the regular old “humanities” is also an unstable, shifting term. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the denotation, “Literary learning or scholarship; secular letters as opposed to theology; esp. the study of ancient Latin and Greek language, literature, and intellectual culture,” is still in use. At the University of Glasgow, Latin was studied in “the Department of Humanity” until 1988, when it merged with Greek to form the Department of Classics. The OED’s other, now dominant denotation of “the humanities” is: “The branch of learning concerned with human culture; the academic subjects collectively comprising this branch of learning, as history, literature, ancient and modern languages, law, philosophy, art, and music.” Yet humanities disciplines continue to vary by institution and country; law, for example, is separated from the humanities in most US universities. And what about Film, Communication, Performance Studies, Women’s Studies, and more? The list is neither fixed nor complete.

This year I’m a research fellow at the Institute for Research in the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where I am witnessing a plurality of definitions of the humanities first-hand. Each week, one of the fellows gives a presentation of their current research, followed by discussion. As you might expect, it is far from clear what unites disciplines as diverse as literary studies, philosophy, musicology, history, and anthropology.

Do we research “the best which has been thought and said in the world” (Matthew Arnold’s famous definition of human culture and justification for studying it in high Victorian England)? Of course not. Earlier this fall, Bethany Moreton showed us how the Catholic lay institution Opus Dei has powerful and even insidious ties to the finance industry; Aida Levy-Hussen uncovered startling tendencies toward masochism in contemporary black literature; and I talked about child sexual abuse in the Shakespearean theater.

Not that we are always a glum bunch. Levy-Hussen’s project locates something cathartic and even emancipatory about masochistic relationships to black history, while James Bromley understands Renaissance “cruising”—male masquerading in fashionable dress with queer overtones—as a way of carving out idealistic modes of being. In fact, quite a few of us take the humanities as an opportunity to search out something brighter or more hopeful. Lois Betty sees utopian tendencies in the revival of Spiritism beginning in late-nineteenth-century France. Alex Dressler locates a drive towards autonomous aesthetic spaces in the literature of ancient Rome.

Okay, but surely we humanists study “human culture” in all of its distopian and utopian complexity? Don’t count on it. One of the driving interests in humanistic research in the past decades has been in the non-human worlds in which we are embedded and from which we cannot, finally, be separated. Adam Mandelman, a doctoral student in geography, brought this to our attention in his presentation on the two-century history of permeability in the Mississippi River Delta. Mandelman studies not only how humans have changed the Delta, now said to be losing the equivalent of a football field of land per hour, but how this muddy, in-between, constantly shifting landscape has shaped what humans are. As the globe warms and coastlines are inundated, Louisiana’s ecological catastrophe is increasingly going to be the world we all live in—and Mandalman’s project has much to tell us about what human life looks like when it is permeated by water.

Call Mandalman a post-humanist if you like (in fact he is also a digital humanist); I say we have always been post-humanist. Humanistic methods and values come to seem unified or unalterable only in a back formation—that is, when they are defined against something (supposedly) different or new. “Humanities computing,” as it used to be called, is not particularly new. It is often said to date to the Index Thomisticus, a machine-processed concordance to the works of Thomas Aquinas begun in 1949 and completed in the 1970s. The re-branding initiative known as the digital humanities or “DH” is a trade-off. It helps to underscore the excitement of research agendas now underway, but it has contributed to the misleading sense that DH is a radically new and comprehensive paradigm. Ellen MacKay and I had this in mind when, inspired by an NEH Institute on the digital humanities at the Folger Shakespeare Library, we started a blog to try to bring out what is lost or fragmented in digital approaches to our field of Renaissance English literature.

Humanists don’t like to define things—or, rather, they love to define things, and then to change their definitions. Provocative articulations of a shared enterprise, adaptive means of approaching problems—what could be more humanistic than that? Just don’t expect the digital humanities to be any more stably defined than their not-explicitly-digital counterparts. Research fields are not supposed to be stable; we learn, change, adapt, and reexamine what we thought we had learned. Words are no different, which is why Oxford Dictionaries benefits from frequent updates.

Image credit: Typing on a Laptop by Daniel Foster. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Defining the humanities appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTechno-magic: Cinema and fairy taleGroup beliefOrphants to foster kids: a century of Annie

Related StoriesTechno-magic: Cinema and fairy taleGroup beliefOrphants to foster kids: a century of Annie

International Law at Oxford in 2014

International law has faced profound challenges in 2014 and the coming year promises further complex changes. For better or worse, it’s an exciting time to be working in international law at Oxford University Press. Before 2014 comes to a close, we thought we’d take a moment to reflect on the highlights of another year gone by.

January

To start off the year, we asked experts to share their most important international law moment or development from 2013 with us.

We published a new comprehensive study into the development, proliferation, and work of international adjudicative bodies: The Oxford Handbook of International Adjudication edited by Cesare Romano, Karen Alter, and Yuval Shany.

February

The editors of the London Review of International Law reflected on the language of ‘savagery’ and ‘barbarism’ in international law debates. The London Review of International Law will now remain free online through the end of February, 2015. Make sure to read the first three issues before a subscription is required for access.

March

As the Russian ‘spring’ of 2014 gained momentum, our law editors pulled together a debate map on the potential use of force in international law focused on the situation in Crimea. We also heard expert analysis from Sascha-Dominik Bachmann on NATO’s response to Russia’s policy of territorial annexation.

Professor Stavros Brekoulakis won the first ever Rusty Park Prize of the Journal of International Dispute Settlement for his article, “Systemic Bias and the Institution of International Arbitration : A New Approach to Arbitral Decision-Making.” His article is free online.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Commentary, Cases, and Materials edited by Ben Saul, David Kinley, and Jaqueline Mowbray published in March, bringing together all essential documents, materials, and case law relating to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

April

In early April, we were finalizing preparations for ASIL-ILA 2014, as were many of our authors and readers. By combining the American Society of International Law and the International Law Association, the schedule was full of interesting discussions and tough choices.

In line with the theme of ASIL-ILA, which focused on the effectiveness of international law, we asked our contributors, “Are there greater challenges to effectiveness in some areas of international law practice than in others? If so, what are they, and how can they be addressed?”

Throughout the conference we connected with authors, editors, and contributors to Oxford University Press publications.

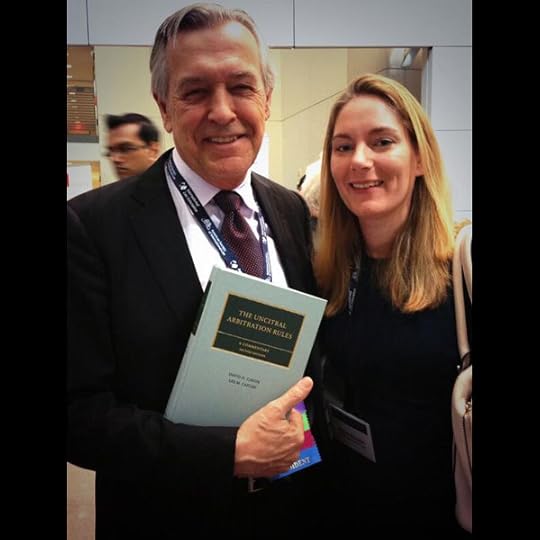

David Caron, co-author of the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules 2nd edition with OUP’s very own Merel Alstein

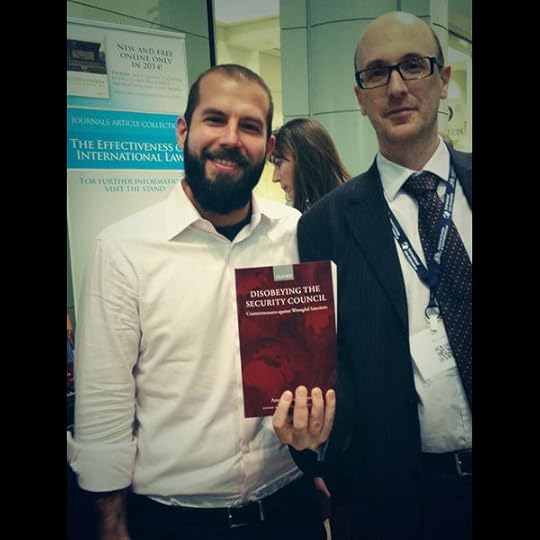

David Caron, co-author of the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules 2nd edition with OUP’s very own Merel Alstein Antonios Tzanakopoulos, author of Disobeying the Security Council: Countermeasures against Wrongful Sanctions, and OUP’s very own John Louth

Antonios Tzanakopoulos, author of Disobeying the Security Council: Countermeasures against Wrongful Sanctions, and OUP’s very own John LouthWe worked with the authors of The Locus Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the end of Violence, Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros, to develop an infographic and learn how solutions like media coverage and business intervention have begun to positively change countries like the Congo, Cambodia, Peru, and Brazil.

May

On 3 May, three years after a US Navy SEAL team killed Osama bin Laden, David Jenkins, discussed justice, revenge, and the law. Jenkins is one of the co-editors of The Long Decade: How 9/11 Changed the Law, which published in April 2014.

EJIL: Live!, the official podcast of the European Journal of International Law (EJIL), launched. Podcasts are released in both video and audio formats to coincide with the publication of each issue of EJIL. View all episodes.

John Yoo’s post on the OUPblog, Ukraine and the fall of the UN system, provided us with a timely analysis of Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula. His book Point of Attack: Preventive War, International Law, and Global Welfare published in April 2014.

June

On World Oceans Day, 8 June, we created a quiz on Law of the Sea. We also developed a reading list for World Refugee Day from Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law.

In June, we celebrated the World Cup in Brazil with a World Cup Challenge from Oxford Public International Law (OPIL). The questions in the challenge all tie to international law, and the answer to each question is the name of a country (or two countries) who competed in the 2013 World Cup Games. Try to work out the answers using your existing knowledge and deductive logic, and if you get stuck, do a bit of research at Oxford Public International Law to find the rest.

The World Cup highlighted the global issue of exploitation of low and unskilled temporary migrant workers, particularly the rights of migrant workers in Qatar in advance of the 2022 World Cup and the abuses of those rights.

July

On 17 July we celebrated World Day for International Justice and asked scholars working in international justice, “What are the most important issues in international criminal justice today?”

In July, Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 was shot down. Kevin Jon Heller answered the question, “Was the downing of flight MH17 a war crime?” in Opinio Juris. Sascha Bachman-Cohen discussed Russia’s potential new role as state sponsor of terrorism on the blog.

On 24 July we added 20 new titles to Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law.

August

To mark the centenary of the start of the Great War we compiled a brief reading list looking at the First World War and the development of international law.

In advance of September’s 10th anniversary European Society of International Law meeting, we asked our experts what they thought the future of international law might look like.

On 23 August we put together an infographic in honour of the UN’s International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

On 30 August we put together a content map of international law articles in recognition of the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances. Click the pins below to be taken to the full text articles.

August saw the publication of the third edition of one of our best-regarded works on international criminal law — Principles of International Criminal Law by Gerhard Werle and Florian Jeßberge — as well as our latest addition to the Oxford Commentaries on International Law series — The Chemical Weapons Convention: A Commentary edited by Walter Krutzsch, Eric Myjer, and Ralf Trapp.

Finally, in August the OUPblog had a revamp! Explore our blog pieces in law.

September

In September, Scotland voted in a referendum. Anthony Carty and Mairianna Clyde addressed what might it have meant for Scottish statehood had Scotland voted for independence? And Stephen Tierney addressed the question, what would an independent Scotland look like?

In celebration of ESIL’s 10th anniversary conference in September, we put together a quiz featuring the eleven cities that have had the honour of hosting an ESIL conference or research symposium since the first in 2004. Each place is the answer to one of these questions – see if you can match the international law event to the right city.

We are the proud publisher of not one but two ESIL Prize Winners! Congratulations to Sandesh Sivakumaran, author of The Law of Non-International Armed Conflict, and Ingo Venzke, author of How Interpretation Makes International Law, on their huge achievement.

Ingo Venzke at the European Society of International Law meeting in Vienna

Ingo Venzke at the European Society of International Law meeting in ViennaSeptember saw the release of Human Rights: Between Idealism and Realism by Christian Tomuschat, an unique and fully updated study on a fundamental topic of international law.

Amal Alamuddin, Barrister at Doughty Street Chambers, co-editor of The Special Tribunal for Lebanon: Law and Practice, and contributor to Principles of Evidence in International Criminal Justice, married the actor George Clooney. Congratulations, Amal!

On 21 September we celebrated Peace Day. We put together an interactive map showing a selection of significant peace treaties that were signed from 1648 to 1919. All of the treaties mapped here include citations to their respective entries in the Consolidated Treaty Series, edited and annotated by Clive Parry (1917-1982).

On 24 September Oxford Historical Treaties launched on Oxford Public International Law. Oxford Historical Treaties is a comprehensive online resource of nearly 16,000 global treaties concluded between 1648 and 1919 (between the Peace of Westphalia and the establishment of the League of Nations).

October

On 10 October, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi. In recognition of their tremendous work, we made a selection of articles on children’s rights free to read online for the month of October.

Michael Glennon, the author of National Security and Double Government, analyzed the continuity in US national security policy during the US attacks on ISIS elements in Syria in mid-October with “From Imperial Presidency to Double Government” on the OUPblog.

On 16 October, Ruti Teitel gave a talk on her new book Globalizing Transitional Justice, which published in May 2014, at Book Culture in New York. The event included a panel discussion with Luis Moreno-Ocampo, the first Prosecutor (June 2003-June 2012) of the new and permanent International Criminal Court, and Jack Snyder, the Robert and Renee Belfer Professor of International Relations in the Department of Political Science and the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia.

Ruti Teitel at Book Culture in New York

Ruti Teitel at Book Culture in New YorkIn October, we were preparing for the 2014 International Law Weekend Annual Meeting at Fordham Law School, in New York City (24-25 October 2014). We were also busy preparing for the FDI Moot, which gathers academics and practitioners from around the world to discuss developments and gain a greater understanding of growing international investment, the creation of international investment treaties, domestic legislation, and international investment contracts. Read more here.

In recognition of UN Day this year on 26 October, we created a free article collection featuring content from international law journals, the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, and The Charter of the United Nations.

In October we published the first in a major three-volume manual bringing together the law of the sea, shipping law, maritime environmental law, and maritime security law. Prepared in collaboration with the International Maritime Law Institute, the International Maritime Organization’s research and training institute, The IMLI Manual on International Maritime Law: Volume I: The Law of the Sea is edited by Malgosia Fitzmaurice, and Norman Martinez with David Attard as the General Editor.

November

In November we published our annual report on armed conflict around the world. The War Report: Armed Conflict in 2013, edited by Stuart Casey-Maslen, provides detailed information on every armed conflict which took place during 2013, offering an unprecedented overview of the nature, range, and impact of these conflicts and the legal issues they created.

In mid-November we published the second edition of Environmental Diplomacy: Negotiating More Effective Global Agreements, by Lawrence E. Susskind and Saleem H. Ali, which discusses the geopolitics of negotiating international environmental agreements. The new edition provides an additional perspective from the Global South and a broader analysis of the role of science in environmental treaty-making.

Judicial Review of National Security expanded our Terrorism and Global Justice Series in late November. Author David Scharia gave a book talk at NYU School of Law’s Center on Law and Security soon after the book published. The talk began with an introduction from President (ret.) Dorit Beinisch of the Supreme Court of Israel.

December

In celebration of Human Rights Day 2014, we asked some key thinkers in human rights law to share stories about their experiences of working in this field, and the ways in which they determined their specific focuses. These reflective pieces were collated into an article for the OUPblog. Additionally, we made a collection of over thirty articles from law and human rights journals free for six months, and promoted a number of books titles alongside the journal collection, on a central page. Finally, 50 landmark human rights cases were mapped across the globe.

Headline image credit: Gavel. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post International Law at Oxford in 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs international law just?Human Rights Awareness Month case mapKenneth Roth on human rights

Related StoriesIs international law just?Human Rights Awareness Month case mapKenneth Roth on human rights

December 28, 2014

Techno-magic: Cinema and fairy tale

Movie producers have altered the way fairy tales are told, but in what ways have they been able to present an illusion that once existed only in the pages of a story? Below is an excerpt from Marina Warner’s Once Upon a Time that explores the magic that movies bring to the tales:

From the earliest experiments by George Meliès in Paris in the 1890s to the present day dominion of Disney Productions and Pixar, fairy tales have been told in the cinema. The concept of illusion carries two distinct, profound, and contradictory meanings in the medium of film: first, the film itself is an illusion, and, bar a few initiates screaming at the appearance of a moving train in the medium’s earliest viewings, everyone in the cinema knows they are being stunned by wonders wrought by science. All appearances in the cinema are conjured by shadow play and artifice, and technologies ever more skilled at illusion: CGI produces living breathing simulacra—of velociraptors (Jurassic Park), elvish castles (Lord of the Rings), soaring bionicmonsters (Avatar), grotesque and terrifying monsters (the Alien series), while the modern Rapunzel wields her mane like a lasso and a whip, or deploys it to make a footbridge. Such visualizations are designed to stun us, and they succeed: so much is being done for us by animators and filmmakers, there is no room for personal imaginings. The wicked queen in Snow White (1937) has become imprinted, and she keeps those exact features when we return to the story; Ariel, Disney’s flame-haired Little Mermaid, has eclipsed her wispy and poignant predecessors, conjured chiefly by the words of Andersen’s story

A counterpoised form of illusion, however, now flourishes rampantly at the core of fairytale films, and has become central to the realization on screen of the stories, especially in entertainment which aims at a crossover or child audience. Contemporary commercial cinema has continued the Victorian shift from irresponsible amusement to responsible instruction, and kept faith with fairy tales’ protest against existing injustices. Many current family films posit spirited, hopeful alternatives (in Shrek Princess Fiona is podgy, liverish, ugly, and delightful; in Tangled, Rapunzel is a super heroine, brainy and brawny; in the hugely successful Disney film Frozen (2013), inspired by The Snow Queen, the younger sister Anna overcomes ice storms, avalanches, and eternal winter to save Elsa, her elder). Screenwriters display iconoclastic verve, but they are working from the premise that screen illusions have power to become fact. ‘Wishing on a star’ is the ideology of the dreamfactory, and has given rise to indignant critique, that fairy tales peddle empty consumerism and wishful thinking. The writer Terri Windling, who specializes in the genre of teen fantasy, deplores the once prevailing tendency towards positive thinking and sunny success:

The fairy tale journey may look like an outward trek across plains and mountains, through castles and forests, but the actual movement is inward, into the lands of the soul. The dark path of the fairytale forest lies in the shadows of our imagination, the depths of our unconscious. To travel to the wood, to face its dangers, is to emerge transformed by this experience. Particularly for children whose world does not resemble the simplified world of television sit-coms . . . this ability to travel inward, to face fear and transform it, is a skill they will use all their lives. We do children—and ourselves—a grave disservice by censoring the old tales, glossing over the darker passages and ambiguities

Fairy tale and film enjoy a profound affinity because the cinema animates phenomena, no matter how inert; made of light and motion, its illusions match the enchanted animism of fairy tale: animals speak, carpets fly, objects move and act of their own accord. One of the darker forerunners of Mozart’s flute is an uncanny instrument that plays in several ballads and stories: a bone that bears witness to a murder. In the Grimms’ tale, ‘The Singing Bone’, the shepherd who finds it doesn’t react in terror and run, but thinks to himself, ‘What a strange little horn, singing of its own accord like that. I must take it to the king.’ The bone sings out the truth of what happened, and the whole skeleton of the victim is dug up, and his murderer—his elder brother and rival in love—is unmasked, sewn into a sack, and drowned.

This version is less than two pages long: a tiny, supersaturated solution of the Grimms: grotesque and macabre detail, uncanny dynamics of life-in-death, moral piety, and rough justice. But the story also presents a vivid metaphor for film itself: singing bones. (It’s therefore apt, if a little eerie, that the celluloid from which film stock was first made was itself composed of rendered-down bones.)

Early animators’ choice of themes reveals how they responded to a deeply laid sympathy between their medium of film and the uncanny vitality of inert things. Lotte Reiniger, the writer-director of the first full-length animated feature (The Adventures of Prince Achmed), made dazzling ‘shadow puppet’ cartoons inspired by the fairy tales of Grimm, Andersen, and Wilhelm Hauff; she continued making films for over a thirty-year period, first in her native Berlin and later in London, for children’s television. Her Cinderella (1922) is a comic—and grisly— masterpiece.

Early Disney films, made by the man himself, reflect traditional fables’ personification of animals—mice and ducks and cats and foxes; in this century, by contrast, things come to life, no matter how inert they are: computerization observes no boundaries to generating lifelike, kinetic, cybernetic, and virtual reality.

Featured image credit: “Dca animation building” by Carterhawk – Own work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Techno-magic: Cinema and fairy tale appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOnce upon a quizWho is your favourite fairy-tale character?Once upon a time, part 2

Related StoriesOnce upon a quizWho is your favourite fairy-tale character?Once upon a time, part 2

Group belief

Groups are often said to believe things. For instance, we talk about PETA believing that factory farms should be abolished, the Catholic Church believing that the Pope is infallible, and the U.S. government believing that people have the right to free speech. But how can we make sense of a group believing something?

This is an important question, from both a theoretical and a practical point of view. If we don’t understand what group belief is, then we won’t be able to grasp what it means to say that a group knows or should have known something. This matters a great deal, given that belief, knowledge, and culpable ignorance are intimately connected to moral and legal responsibility.

For instance, if the Bush Administration believed that Iraq did not have weapons of mass destruction, then not only did the Administration lie to the public in saying that it did, but it is also fully culpable for the hundreds of thousands of lives needlessly lost in the Iraq war. And if BP should have known that its Deepwater Horizon oil rig was in need of repairs, then it is responsible for the vast quantity of oil that spilled into the Gulf of Mexico.

Despite the importance of this question, the topic of group belief has received surprisingly little attention in the philosophical literature. So far, the majority of those who have addressed it favor an inflationary approach where groups are treated as entities with “minds of their own.” That is to say, groups are something more than the mere collection of their members, and group belief is something more than their individual beliefs. This rather bold view is typically motivated by arguments that claim a group can be properly said to believe something even when not a single one of its members believes it. A classic example of this sort of case is where a group decides to let a view “stand” as what the group thinks, despite the fact that none of its members actually holds the view in question.

For instance, suppose that the Philosophy Department at a university is deliberating about the final candidate to whom it will extend admission to its graduate program. After hours of discussion, all of the members jointly agree that Jane Smith is the most qualified candidate from the remaining pool of applicants. However, not a single member of the department actually believes this; instead, they all think that Jane Smith is the candidate who is most likely to be approved by the administration. Here, it is argued that the Philosophy Department itself believes that Jane Smith is the most qualified candidate for admission, even though none of the members holds this belief. This attribution of belief to the group is supported by looking at its actions: the group asserts that Jane Smith is the most qualified candidate, it defends this position in conversation with administrators, it heavily recruits her to join the department, and so on. Why does the group do all of this? The most natural explanation of how the group behaves is that it really does think Jane is the best candidate—and this can be true even if each group member would deny it individually.

Berlin Street Scene by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Berlin Street Scene by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This argument has led some philosophers to say that a group’s believing something should be understood in terms of the members of the group intentionally and openly jointly accepting it, where it is possible to accept something without believing it. The Philosophy Department above, then, believes that Jane Smith is the most qualified candidate for admission, even though none of the members holds this belief, precisely because they jointly agree to let this position stand as the group’s.

There is, however, what I take to be a decisive objection to this way of thinking about group belief. Groups lie, and they do so with some frequency: a cursory review of recent news pulls up stories about the lies of Halliburton, Enron, the Bush Administration, and various pharmaceutical companies. And no matter how we understand group lies, a minimum condition is that a group must state what it believes to be false.

Here is a paradigmatic group lie, slightly fictionalized from a real case: Phillip Morris, one of the largest tobacco companies in the world, is aware of the massive amounts of scientific evidence revealing not only the addictiveness of smoking, but also the links it has with lung cancer. While all of the members of the board of directors of the company believe this conclusion, they all openly decide and then jointly accept that, because of what is at stake financially, the official position of Phillip Morris is that smoking is neither highly addictive nor detrimental to one’s health. This claim is then published in all of their advertising materials and defended against objections.

Herein lies the problem with the joint acceptance account: an adequate view of group belief should be able to tell the difference between a group’s stating its belief and a group’s lying. On the joint acceptance account, however, the actions of Phillip Morris in the case above make it the case that the group believes that smoking is neither highly addictive nor detrimental to one’s health. The relevant members of the company—namely, the board of directors—not only jointly accept this proposition, but also support it through their public statements, actions, planning, and so on. But surely the most natural way to think of what the company is doing is that they are lying about the health risks of smoking. Phillip Morris says what it does, not because the company genuinely believes that smoking isn’t dangerous, but because it wants to deceive others to believe this.

Because the joint acceptance account confuses group belief with group lying, we should look for a new way to think about group belief.

The post Group belief appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs yoga religious?Almost paradise: heaven in imaginative literatureEmbark on six classic literary adventures

Related StoriesIs yoga religious?Almost paradise: heaven in imaginative literatureEmbark on six classic literary adventures

December 27, 2014

Alternative access models in academic publishing

Disseminating scholarship is at the heart of the Oxford University Press mission and much of academic publishing. It drives every part of publishing strategy—from content acquisition to sales. What happens, though, when a student, researcher, or general reader discovers content that they don’t have access to?

For example, while a majority of Oxford Handbook Online (OHO) and Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) users have access through their institutions, not everyone does; sometimes even those who do need to conduct research at home or while on leave, when they aren’t connected to their campus networks. To facilitate such research, Oxford has partnered with the Copyright Clearance Center to begin offering chapters on a pay-per-view basis. Pay-per-view is a well-established business model in journal publishing but is only recently gaining traction for book-based content.

Beginning in October, unauthenticated users of Oxford Handbooks began seeing buy buttons on articles. Clicking the button will allow them to purchase 24-hour access or, for a premium, unlimited perpetual access. And starting in the New Year, just in time for the start of the new term, this option will be available at the chapter level in Oxford Scholarship Online.

As with any change, we didn’t take this lightly. Oxford, like any other publisher, needed to fully weigh the risks against the benefits. Our partnership with the Copyright Clearance Center is focused on expanding access while maintaining our robust global institutional partnerships. The benefits were clear from the start: allowing more users to access our content—from any device at any hour of the day—and in a multitude of currencies. A student rushing to finish a paper at the end of the term or a researcher away from her library can have full access to the best scholarship with just a few clicks and a credit card. They can cite with confidence.

© OJO_Images via iStock.

© OJO_Images via iStock. With just a few months under our belt, the early results are incredibly encouraging. Customers from around the globe are accessing award-winning content—some for just 24 hours, others choosing to retain the article in perpetuity. We’re working with these users throughout to learn more—from their geographical location to the ease of the transaction. All of this feedback helps us further develop this new access model, our platform, and the overall user experience. Over the next year, we will further experiment with discounting, personalization, and recommendations to make the most of this important project.

In the end, we hope to have learned great deal about getting the best research into the hands—and minds—of as many users as possible. That, after all, is our mission.

The post Alternative access models in academic publishing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSeven facts about American Christmas MusicPreparing for APA Eastern Meeting 2014On the future of environmental and natural hazard science

Related StoriesSeven facts about American Christmas MusicPreparing for APA Eastern Meeting 2014On the future of environmental and natural hazard science

Orphants to foster kids: a century of Annie

One of the best-known musicals of the 20th century is Annie, which tells the story of a plucky orphan girl who warms the hearts of all around her, and eventually finds a loving family of her own. The tale will be carried into the 21st century when the newest film adaptation (produced by Jay-Z and Will Smith; perhaps you’ve heard of them) is released on 19 December of this year. In honor of the long legacy of this famous story, here we take a look at the changing language of Annie.

Little orphant AllieSpeaking of long legacies, the 1977 musical Annie was not the first time the world had been introduced to the inspirational young character. The musical was based on an American comic strip entitled “Little Orphan Annie”. Well-known in its own time and called the most famous comic of 1937 by Fortune magazine, “Little Orphan Annie” ran for a whopping 86 years and even led to an equally famous radio show (religiously followed by Ralph in the 1983 film A Christmas Story). However, the story of Annie can be traced further back to a girl named Mary Alice Smith (nicknamed “Allie”), who inspired Indiana poet James Whitcomb Riley to pen the poem “The Elf Child” in 1885. He would eventually rename it “Little Orphant Allie”.

“Orphant”? Not a typo—just a US regional variant spelling that has since fallen largely out of use, as have other variants orphaunt, orfant, and even orphing (among many others). However, a literal typo or typographical error did come into play with Riley’s poem when the name “Annie” was accidentally typeset instead of “Allie”. When the poem gained popularity, Riley decided to stick with the new name.

The original hard knocksPeople looking for the familiar plot or song lyrics in the original poem will be disappointed: there is almost no resemblance between the Annie of the poem and Annie as she is popularly known today. The poem, like several of Riley’s others, is written in Hoosier dialect—the midland dialect of American English, or more specifically that from Indiana. In the poem, “little orphant Annie” tells stories to other orphaned children in which “gobble-uns” (goblins) steal poorly behaved children away (hence the original title “The Elf Child”). At the end of the didactic poem, Annie says

You better mind yer parunts, an’ yer teachurs fond an’ dear,

An’ churish them ‘at loves you, an’ dry the orphant’s tear,

An’ he’p the pore an’ needy ones ‘at clusters all about,

Er the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

However, like the Annie of the later comic strip, musical, and film adaptations, “little orphant Annie” is happy to take the “pore an’ needy” under her wing and to teach them what she knows.

Hoovervilles and ProhibitionThough the musical Annie opened on Broadway in 1977 and its film adaptation was released in 1982, the plot takes place in the 1930s. Apart from the clothing styles and the Hoovervilles, the song lyrics themselves—with many words unfamiliar to the modern English-speaker— are intended to transport audiences to the early 20th century.

Yank the whiskers from her chin!

Jab her with a safety-pin!

Make her drink a Mickey Finn!

Purportedly taking its name from the proprietor of a Chicago saloon who, in the early 20th century, was accused of poisoning customers with “knock-out drops”, a Mickey Finn is a surreptitiously drugged or doctored drink.

Every plot’s a dilly,

This we guarantee!

Dilly, an alteration of the first syllable of delightful or delicious, is a North American word for an excellent example of something.

You spend your evenings in the shanties,

Imbibing quarts of bathtub gin.

And here you’re dancing in your scanties.

To a modern-day reader, it may not be clear how much Daddy Warbucks is insulting Miss Hannigan in the song “Sign” from the 1982 film. When he accuses her of spending time in the shanties, he is probably referring to shantytowns: run-down areas consisting of large numbers of shanties, or small, crudely built shacks. These shantytowns (or Hoovervilles, as they were sometimes called, after the US President Herbert Hoover) were an all-too-familiar sight during the Great Depression, when as much as 25% of Americans were unemployed.

As for bathtub gin, readers familiar with the Prohibition era in the United States may know what it is—a concoction of spirits intended to simulate the taste of gin, representative of a time in which alcoholic drinks (rendered illegal by the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution in 1920) were often surreptitiously made in homes (and sometimes, presumably, in bathtubs). It goes without saying that, generally, the quality of “bathtub gin” was probably not very high.

Daddy Warbucks gets in one final jab by accusing Miss Hannigan of dancing around in her scanties, or brief underwear. (The word comes from scant + -y; scant is from the Old Norse word for “short”.) Interestingly, a modern word for a similar type of women’s underwear—panties—could be substituted here without sacrificing rhyme.

On the topic of modernizing lyrics, the upcoming movie Annie will debut such changes of its own; in the song “Hard-Knock Life”, what originally was

No one cares for you a smidge

When you’re in an orphanage

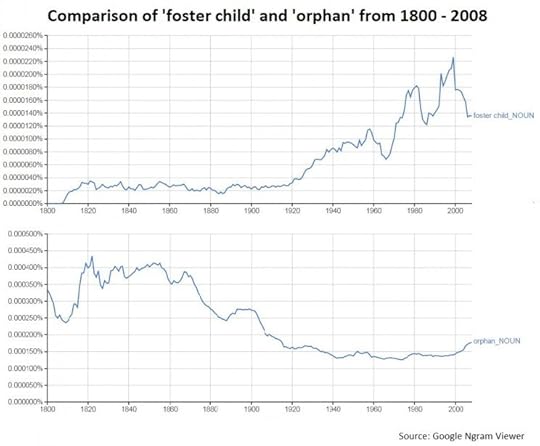

Comparison of ‘foster child’ to ‘orphan’ from 1800-2008

Comparison of ‘foster child’ to ‘orphan’ from 1800-2008 has been updated to

No one cares for you a bit

When you’re a foster kid

Here, bit may have replaced smidge as a better near rhyme, or it may been considered a safer bet in terms of plausible vocabulary for a 10-year-old in 2014 (it doesn’t seem a stretch to say that smidge is probably not in the parlance of today’s youth). As for the replacement of orphanage with “foster kid”, given that the new movie doesn’t involve an orphanage—instead, Annie is in a foster home—this change is practical.

However, it can also be noted that fostering has gradually taken the place of institutional care and sociocultural developments have shaped the concept of child welfare as we understand it today. For these reasons in part, it may not be surprising that the use of the word “foster child” has been increasing somewhat steadily over the last two centuries, while use of the word orphan (though still more common overall) has dwindled over the same period of time.

TomorrowThough Annie has been around long enough for “orphant” to eventually turn into “foster kid”, the fact remains that American audiences are perennial lovers of the rags-to-riches theme. For this reason, it should come as no surprise that the story of Annie is just as well-known today as when Ralph was racing to the radio—or that virtually everyone you know can sing at least a few bars of “Tomorrow”. It probably goes without saying that we’ll see many more iterations of Annie in the century to come.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

The post Orphants to foster kids: a century of Annie appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe advantage of ‘trans’Season’s greetings, or “That’s the cheese”The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is…vape

Related StoriesThe advantage of ‘trans’Season’s greetings, or “That’s the cheese”The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is…vape

December 26, 2014

Embark on six classic literary adventures

Despite fierce winds, piles of snow, and the biting cold, winter is the best season for some cozy reading (and drinking hot chocolate). If you’re inclined to stay in today, check out these favorite classics of ours that will take you on wild adventures, all while huddled underneath your sheets.

Jules Verne’s The Extraordinary Journeys: Around the World in Eighty Days

What starts out as a bet to settle an argument between club members transforms into a grand adventure. It is fascinating, fast-paced, and enchanting, and brings you around the world in just eighty days!

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s Don Quixote de la Mancha

In following the journey of Alonso Quixano, we find ourselves both amused and sad at the protagonist’s delusion of the world around him. The satirical elements of Don Quixote have permeated our modern literary culture and vocabulary: the term “quixotic” describes one who is too idealistic.

Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo

Jealousy, revenge, romance, hope, and justice flavor this jam-packed classic. After being thrown into jail for accused treason, Edmond Dantès only escapes after his fellow prisoner discloses the location of a vast wealth on the island of Monte Cristo. Once Dantès retrieves the hidden treasure, he poses as the Count of Monte Cristo and thus begins his plot of revenge against the men who put him away.

Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels

From the land of people no larger than six inches tall, to the land of horse people called Houyhnhnms, Lemuel Gulliver finds himself in lands like no other. His travels are sparked by (what we assume to be) a mid-life crisis, when his business fails. In a number of expeditions, Gulliver takes to the seas in a wanderlust sort of way, visiting his wife and children in between travels.

Image by Igor Ilyinsky. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

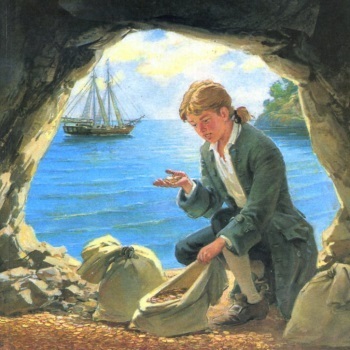

Image by Igor Ilyinsky. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island

In this six-part adventure, Jim Hawkins narrates his journey from the death of a patron at his family’s inn — leaving behind a map and other clues pointing to buried treasure — to encounters with pirates on the high seas. Treasure Island captivates with its simple, yet lively prose. It’s a coming-of-age story for anyone at any age.

Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers

Athos, Porthos, and Aramis—the three musketeers—join up with a young noble named d’Artagnan, who seems to find trouble for himself. In this riveting tale full of assassination attempts, a scandalous love affair, and revenge, there is also fierce loyalty, camaraderie, and energy among the four musketeers.

Headline image credit: Irving Johnson. Original photo courtesy of Glenn Batuyong, Port of San Diego. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Embark on six classic literary adventures appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVirginia Woolf’s Orlando and the country houseA reading list of Roman classicsA reading list of Ancient Greek classics

Related StoriesVirginia Woolf’s Orlando and the country houseA reading list of Roman classicsA reading list of Ancient Greek classics

Is yoga religious?

Many outsiders to contemporary popularized yoga profoundly trivialize it by reducing it to a mere commodity of global market capitalism, and to impotent borrowings from or “rebrandings” of traditional, authentic religious products. In other words, according to this account, popularized yoga can be reduced to mere commodities meant to fulfill utilitarian needs or meet hedonistic desires.

On the other hand, many yoga insiders frequently avoid categorizing yoga as religion, preferring to categorize it as spiritual or to invoke other non-explicitly religious terms to describe it. For example, Houston yoga practitioner, teacher, studio owner, and advocate Jennifer Buergermeister responded to attempts by the State of Texas to regulate yoga as a career school by suggesting, “Regulating Yoga as a career school detracted from its rightful place as a spiritual and philosophical tradition.” J. Brown, a New York yoga advocate has suggested yoga is “sacred,” is an “all-encompassing whole Truth,” and functions to explore the “self, health, and life.” Yoga studio owner and instructor Bruce Roger definitively stated, “Yoga is a spiritual practice. It’s not a purchase.”

Many yoga advocates avoid the category religion because it connotes an authoritative institution or doctrine in the popular imagination. Well-known yoga advocate T. K. V. Desikachar suggests yoga is not religious because it does not have a doctrine concerning the existence of God. Yoga Journal journalist Phil Catalfo, along with many other yoga insiders, suggests that yoga is spirituality, not religion, yet advocates define yoga in religious terms even if they avoid explicitly labeling it a “religion.”

If one closely evaluates examples from modern postural yoga, however, it becomes apparent that yoga, even in its popularized forms, can have robust religious qualities. Popularized yoga can serve as a body of religious practice in the sense of a set of behaviors that are treated as sacred, as set apart from the ordinary or mundane dimensions of everyday life; that are grounded in a shared ontology or worldview (although that ontology may or may not provide a metanarrative or all-encompassing worldview); that are grounded in a shared axiology or set of values or goals concerned with resolving weakness, suffering, or death; and that are reinforced through myth and ritual.

In the postural yoga context, for example, when Iyengar’s students repeat their teacher’s famous mantra—“The body is my temple, [postures] are my prayers”—or read in one of his monographs—“Health is religious. Ill-health is irreligious” (Iyengar 1988: 10)—they testify to experiencing the mundane flesh, bones, and physical movements and even yoga accessories as sacred. Yet a sacred body nevertheless remains a body of flesh and bone, and a sacred yoga mat nevertheless remains a commodity in the form of a rubber mat. The material and even commodified dimensions of yoga, therefore, are not incompatible with the religious dimensions of yoga.

Founder and Director of the Prison Yoga Project James Fox leads students through the uttihita chaturanga danda asana (plank posture) in 2012 at San Quentin State Prison in San Quentin, California. Photographed by Robert Sturman. (Courtesy of Robert Sturman.)

Founder and Director of the Prison Yoga Project James Fox leads students through the uttihita chaturanga danda asana (plank posture) in 2012 at San Quentin State Prison in San Quentin, California. Photographed by Robert Sturman. (Courtesy of Robert Sturman.) In the Prison Yoga Project, salvation is conceptualized as a form of bodily healing. In 2002, James Fox, postural yoga teacher and founder and director of the Prison Yoga Project, began teaching yoga to prisoners at the San Quentin State Prison, a California prison for men. According to the Prison Yoga Project, most prisoners suffer from “original pain,” pain caused by chronic trauma experienced early in life. The consequent suffering leads to violence and thus more suffering in a vicious cycle that can last a lifetime. Yoga, according to the Prison Yoga Project, provides prisoners dealing with original pain with a path toward healing and recovery.

Finally, consider the mythological dimensions of modern postural yoga. Yoga giants B. K. S. Iyengar (1918-2014) and K. Pattabhi Jois (1915-2009) serve as examples of how yoga branding and mythologizing go hand-in-hand. Both mythologize their systems of postural yoga in ways that tie those systems to ancient yoga traditions while simultaneously reflecting dominant cultural ideas and values by claiming biomedical authority. Their myths ground postural yoga in a linear trajectory of transmission from ancient yoga traditions. Claims to that transmission are frequently made and assumed to be historically accurate.

While Iyengar has historically claimed ties between Iyengar Yoga and the ancient yoga transmission going at least as far back as the Yoga Sutras (circa 350-450 CE), he recently introduced a ritual invocation to Patanjali, believed to be the author of the Yoga Sutras, at the beginning of each Iyengar Yoga class. Iyengar also presents yoga as biomedically legitimized as is evidenced by the biomedical discourse that permeates his work on yoga, referring, for example, to the postures’ benefits for “every muscle, nerve and gland in the body.”

In like manner, Jois suggested that verses from the earliest Vedas delineate the nine postures of the suryanamaskar sequences of postures in his Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga system. Simultaneoulsy, he reevaluates the purification function of yoga as resulting, not in the purification from karma, but in the purification from disease.

In the postural yoga world, branding and mythologizing simultaneously involve validating yoga based on its ties to both ancient origins and modern science.

Featured image credit: Yoga 4 Love Community Outdoor Yoga class for Freedom and Gratitude on Independence Day 2010 in Dallas, Texas. Photographed by Lisa Ware and Richard Ware. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is yoga religious? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat do nurses really do?Season’s greetings, or “That’s the cheese”What did the Treaty of Ghent do? A look at the end of the War of 1812

Related StoriesWhat do nurses really do?Season’s greetings, or “That’s the cheese”What did the Treaty of Ghent do? A look at the end of the War of 1812

What do nurses really do?

Nurses play a huge role in hospitals, clinics, and various care facilities throughout the world. However, there are widespread misconceptions about what responsibilities nurses have. Nurses are saving lives and making a difference every day in health care with little recognition from the media or the world at large. Test your knowledge and see how much you really know about what exactly goes into the job of being a nurse.

Get Started! Your Score: Your Ranking:Featured Image: USMC – 07790 by Ryan R. Jackson. Public Domain via WikiCommons

The post What do nurses really do? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow much are nurses worth?Once upon a quizA perfume for loneliness

Related StoriesHow much are nurses worth?Once upon a quizA perfume for loneliness

Discovering microbiology

Microbiology should be part of everyone’s educational experience. European students deserve to know something about the influence of microscopic forms of life on their existence, as it is at least as important as the study of the Roman Empire or the Second World War. Knowledge of viruses should be as prominent in American high school curricula as the origin of the Declaration of Independence. This limited geographic compass reflects the fact that the science of microbiology is a triumph of Western civilization, but the educational significance of the field is a global concern. We cannot understand life without an elementary comprehension of microorganisms.

Appreciation of the microbial world might begin by looking at pond water and pinches of wet soil with a microscope. Precocious children could be encouraged in this fashion at a very early age. Deeper inquiry with science teachers would build a foundation of knowledge for teenagers, before the end of their formal education or the pursuit of a university degree in the humanities.

Earth has always been dominated by microorganisms. Most genetic diversity exists in the form of microbes and if animals and plants were extinguished by cosmic bombardment, biology would reboot from reservoirs of this bounty. The numbers of microbes are staggering. Tens of millions of bacteria live in a crumb of soil. A drop of seawater contains 500,000 bacteria and tens of millions of viruses. The air is filled with microscopic fungal spores, and a hundred trillion bacteria swarm inside the human gut. Every macroscopic organism and every inanimate surface is coated with microbes. They grow around volcanoes and hydrothermal vents. They live in blocks of sea ice, in the deepest oceans, and thrive in ancient sediment on the seafloor. Microbes act as decomposers, recycling the substance of dead organisms. Others are primary producers, turning carbon dioxide into sugars using sunlight or by tapping chemical energy from hydrogen sulfide, ferrous iron, ammonia, and methane.

Bacterial infections are caused by decomposers that survive in living tissues. Airborne bacteria cause diphtheria, pertussis, tuberculosis, and meningitis. Airborne viruses cause influenza, measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox, and the common cold. Hemorrhagic fevers caused by Ebola viruses are spread by direct contact with infected patients. Diseases transmitted by animal bites include bacterial plague, as the presumed cause of the Black Death, which killed 200 million people in the 14th century. Typhus spread by lice decimated populations of prisoners in concentration camps and refugees during the Second World War. Malaria, carried by mosquitos, massacres half a million people every year.

Contrary to the impression left by this list of infections, relatively few microbes are harmful and we depend on a lifelong cargo of single-celled organisms and viruses. The bacteria in our guts are essential for digesting the plant part of our diet and other bacteria and yeasts are normal occupants of healthy skin. The tightness of our relationship with microbes is illustrated by the finding that human DNA contains 100,000 fragments of genes that came from viruses. We are surprisingly microbial.

Agar kontaminaatio. Photo by Mädi. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Agar kontaminaatio. Photo by Mädi. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons Missing the opportunity to learn something about microbiology is a mistake. The uninformed are likely to be left with a distorted view of biology in which they miscast themselves as the most important organisms. For example, “Sarah” is a significant manifestation of life from Sarah’s perspective, but her body is not the individual organism that she imagines, and nor, despite her talents, is she a major player in the ecology of the planet. Her interactions with microbes will include a healthy relationship with bacteria in her gut, bouts of influenza and other viral illnesses, and death in old age from an antibiotic-resistant infection. Sarah’s microbiology will continue after death with her decomposition by fungi. In happier times she will become an expert on Milton’s poetry, and delight students by reciting Lycidas through her tears, but she will never know a thing about microbiology. This is a pity. Learning about viruses that bloom in seawater and fungi that sustain rainforests would not have stopped her from falling in love with Milton.

Even brief consideration of microorganisms can be inspiring. A simple magnifying lens transforms the surface of rotting fruit into a hedgerow of glittering stalks topped with jet-black fungal spores. Microscopes take us deeper, to the slow revolution of the bright green globe of the alga Volvox as its beats its way through a drop of pond water. A greater number of microbes are quite dull things to look at and their appreciation requires greater imagination. Considering that our bodies are huge ecosystems supported by trillions of bacteria is a good place to start, and then we might realize that we fade from view against the grander galaxy of life on Earth. The science of microbiology is a marvel for our time.

Featured image credit: BglII-DNA complex By Gwilliams10. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Discovering microbiology appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLooking for TutankhamunDruids and naturePopulation ecologists scale up

Related StoriesLooking for TutankhamunDruids and naturePopulation ecologists scale up

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers