Oxford University Press's Blog, page 721

December 20, 2014

Annie and girl culture

The musical version of little orphan Annie – as distinct from her original, cartoon incarnation – was born a fully formed ten-year-old in 1977, and she quickly became an icon of girlhood. Since then, thousands of girls have performed songs like “Maybe” and “Tomorrow,” sometimes in service to a production of the musical, but more often in talent shows, music festivals, or pedagogical settings. The plucky orphan girl seems to combine just the right amount of softness and sass, and her musical language is beautifully suited to the female prepubescent voice. So what can Annie teach us about what girls are?

Annie (c) Sony Pictures 2014

Annie (c) Sony Pictures 2014As with any role, the parts available to child performers are shaped by clichés and stereotypes, and these govern our thinking about what real children are like. For girls, the two most prominent archetypes have been the angelic, delicate, and wan girl who arouses our impulse to console and protect, and the feisty, spunky girl of the street who teaches us to know ourselves. These archetypes are often assigned to singing girls as “the little girl with the voice of an angel” and “the little girl with the great big voice.” A crucial aspect of Annie’s appeal is her blurring of this distinction through combining vulnerability with toughness.

These complementary characterizations of girls are invariably shaped by hegemonic understandings of race and class; and here, the figures of Topsy and Eva, from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, serve as paradigms. In the novel, Eva St. Clare is presented as an ethereal golden child, deeply religious and kind, and her angelic virtue is contrasted with the wilful slave girl Topsy, whose wicked ways and rough language are eventually tamed at the deathbed of her young mistress Eva. In her life beyond the book, however, Topsy reverts to her impish and disruptive nature.

The character of Annie seems to combine the sweetness of Eva and the sass of Topsy in ways that evidently continue to appeal in 2014, and the new film version opening this weekend contributes a new aspirational model of girlhood to young fans.

It is thus of enormous significance that the film, produced by Jay Z and Will Smith, casts an African American girl in what is, arguably, the single most-coveted musical theatre role for girls. A 2008 study concludes that girls of colour are the children least likely to see themselves reflected in children’s media because 85.5% of characters in children’s films are white, and three out of four characters are male. The symbolic impact of Quvenzhané Wallis’s visibility and audibility in this role is potentially tremendous.

Unlike most of the young actresses who have played Annie, Wallis had no prior training as a singer. The film’s producers specifically said they did not want “Broadway kids” in the cast, preferring instead untutored singing that would give Annie greater sincerity and naturalness. This ideal of naturalness attaches itself to almost all child performers; we prefer to think of children’s performance as artless and uncalculated. As Carolyn Steedman observes in her book Strange Dislocations: Childhood and the Idea of Human Interiority, “the child’s apparent spontaneity is part of what is purchased with the ticket.”

So it’s no coincidence that many child stars find it difficult to outgrow their most famous roles. Co-star Jamie Foxx gushes that Quvenzhané Wallis was “made to play the role,” an odd form of praise when we reflect that she is playing the part of a neglected, unloved child abandoned to a wretched foster home. In his book Inventing the Child: Culture, Ideology, and the Story of Childhood, Joseph Zornado has observed that

“Annie’s story is a particularly pronounced version of how contemporary culture tells itself a story about the child in order to defend its treatment of the child. Annie’s emotional state — her unflagging high spirits, angelic voice, and distinctly American optimism — grows out of the adult-inspired ideology of the child’s ‘resiliency.’”

Of course, Annie is not Wallis’s first role, and much of our sense of her has already been shaped by her extraordinary, Oscar-nominated performance in 2012’s Beasts of the Southern Wild. If child stars are often believed to be just like the characters they play by fans who resist the idea that children can be artful performers, this seems particularly true in the case of African American girls, because they are so seldom depicted in media that they are invariably reduced to clichés. Wallis’s role in Beasts was a semi-feral child of nature, an old soul raising herself in a dystopic world; yet she is repeatedly asked in interviews if she is like Hushpuppy. How, then, will the iconic role of Annie change our understanding of Quvenzhané Wallis as an actor? Perhaps more importantly, how will her performance shape future possibilities for black girls on the stage and screen?

I suspect that the crucial song in this new film production of Annie is not one of Strouse’s original pieces, but rather “Opportunity,” in which Annie reflects on her luck in being temporarily rescued from neglect. Within the context of the film’s story, she makes up the song on the spot, pulling pitches out of the air in a rhythmically-fluid phrase with an improvisatory style. Musicians on the stage join in, but her melody eludes a clear sense of key almost until the start of the chorus:

And now look at me, and this opportunity

It’s standing right in front of me

But one thing I know

It’s only part luck and so

I’m putting on my best show

Under the spotlight

I’m starting my life

Big dreams becoming real tonight

So look at me and this opportunity

You’re witnessing my moment, you see?

This gorgeous song has also been recorded by its composer Sia, who imbues it with a more adult, contemplative character, in keeping with her singer/songwriter aesthetic. Even in this recording, though, the final verse is given over to Wallis and her closely-mic’ed, child-like (albeit auto-tuned) voice. The song is Wallis’s as much as it is Annie’s. It remains to be seen just how her opportunity will be extended to other girls.

Headline image credit: 8 mm Kodak film reel. Photo by Coyau. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Annie and girl culture appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 fun facts about sleigh bellsFive tips for music directors during the holiday seasonThe Lerner Letters: Part 2 – Lerner and Loewe

Related Stories10 fun facts about sleigh bellsFive tips for music directors during the holiday seasonThe Lerner Letters: Part 2 – Lerner and Loewe

Catching up with Charlotte Green, Psychology Editor

How exactly does one become a book editor? I sat down with Charlotte Green, the Senior Assistant Commissioning Editor for Psychology and Social Work titles in the Oxford office, to discuss some common questions about her role, her interest in publishing, and her time at Oxford University Press.

When did you start working at the Press?

In May 2007. I was lucky enough to get onto the OUP internship scheme, starting immediately after my final exams at university. I’ve worked here ever since. Initially I worked as an Assistant Production Editor, staying with the production team for 18 months. A position then opened up in the editorial team and I transferred across.

When did you first become interested in publishing?

From age dot. I always wanted to work with books and words, so publishing fitted that bill. I was the child falling asleep at the front of the classroom because I’d stayed up most of the night hiding under my bed sheets with a torch, finishing my current book. I just always knew I wanted to put books out into the world.

Even now books are getting me into trouble at home. My partner has a one-in-one-out policy when it comes to our bookshelves, which is a constant source of argument.

Charlotte Green

Charlotte GreenWhy were you drawn to working on psychology books?

I think everyone is an amateur psychologist at heart. Walk into any cocktail bar on a Friday night and you’ll see groups of girls giving each other advice. Likewise in pubs or the grandstands, boys will be doing the same (but probably in far fewer words). People are fascinating. Being given the chance to work on the books that bring research in those topics to a wide audience, that is a true honour and I count myself lucky every single day that I get to be a part of that.

What is a typical day like for you as an editor?

The simple answer is that there is no such thing as a typical day; that is one of the reasons why I love my job. The only constant is communication. I spend most of my day communicating with people. Whether that be through email, on the phone, or in person; be it with other members of OUP, or external suppliers, or my authors, I spend all of my day chatting and that is amazing! Naturally I also spend a lot of time reading. Again, I read from a publisher’s perspective, not an academic’s, so I won’t be reading to spot factual errors, but instead for readability and formatting errors

What skills do you find to be the most important in your work as an editor?

Communication. Everything else you can learn but you are either born with outstanding communication skills or you aren’t. I receive between 100 and 160 emails a day. My phone will ring upwards of 10 times a day. I have no less than three hour-long meetings a day. None of that can be achieved unless you can radiate an aura of calm authority and get your meaning across in a confident manner.

How has academic publishing changed since you started working here?

When I started I worked in production. At that point we just had one focus: we were given a stack of printed A4 sheets and told to make a book out of them. There was no guidance, no hand holding. I was just abandoned with a (often very heavy) pile of paper and told to go forth and create a book. Eight months later the editor might stick their head around my office door and say, got that book yet? Now there are huge expectations, not just surrounding the advent of digital, although that plays a massive part in it. But everybody wants things more quickly, more cheaply, and just more of it.

What are you reading at the moment?

At work I’m reading chapters from three different volumes., one of which is Christopher Eccleston’s The Psychology of the Body, which will go into production in February/March time and publish late 2015. Each chapter of Chris’s book takes a different aspect of the human body (such as breathing) and looks at how psychology can affect its functionality.

At home I’m reading Twenty Chickens for a Saddle by Robyn Scott, which is an autobiography of a girl growing up in Botswanna during the AIDS crisis. It’s both funny and sad and I would thoroughly recommend it.

If you could have a dinner party with your favourite famous psychologists, who would make the guest list?

The first invite would have to go to Professor Philip Zimbardo. Zimbardo led a team of researchers in the early 1970s looking at the causes of conflict between military guards and prisoners. He conducted the famous Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE), in which 24 male students from Stanford University were randomly assigned the role either of guard or prisoner. Zimbardo and his team watched as behaviour changed dramatically: prisoners passively accepted psychological abuse and the guards readily harassed those in their care. It looked at human behaviour and forced us to ask, what would we do in a position of authority? You can watch original footage taken from the experiment here:

My second invite would go to someone who isn’t a psychologist in the traditional sense, Primo Levi, a survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Levi’s 1947 memoir If this is a man (UK edition) or Survival in Auschwitz (US edition) and its sequel describe his experiences as an Italian Jew imprisoned in Auschwitz and then life after the camp’s liberation. Levi’s biographies provide insights into a human being’s behaviour under duress. What it takes to survive and how one copes with the random nature of survival.

My final invite would go to Professor Colwyn Trevarthen. He is a psychologist working in the field of infant development who has been instrumental in some pretty major policy changes in early years education here in the UK.

The post Catching up with Charlotte Green, Psychology Editor appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesConstitutional shock and aweThe Battle of the Bulge10 medically-trained authors whose books all doctors should read

Related StoriesConstitutional shock and aweThe Battle of the Bulge10 medically-trained authors whose books all doctors should read

Constitutional shock and awe

Scotland has of course dominated the television and newsprint headlines over the last year, and has now emerged as the Oxford Atlas Place of the Year for 2014. This accolade is a fair reflection of the immense volume of recent discussion about Scotland’s constitutional future, and that of the United Kingdom. This in turn is surely linked to the fact that the recent rapid consolidation of support for Scots independence has shocked some sections of British (and wider, international) opinion. Constitutional shock and awe are linked, in turn, to deep-rooted complacency about Scotland’s participation in the Union, and the solidity of the United Kingdom itself.

In some ways this complacency is entirely understandable. Scotland and the Scots have occupied central positions in some of the key institutions of the British state – the monarchy, parliament, and the armed forces, to name but three. The culture of the army is squarely associated with the mythology and imagery surrounding the Scottish regiments – their distinctive dress and their reputation for bravery in battle. The British monarchy is thoroughly inflected through Scotland and the Scots, and particularly since the ‘Balmoralisation’ of that institution by Queen Victoria. The close linkages between the House of Windsor and Scotland were of course reinforced through the Queen Mother, a daughter of the 14th Earl of Strathmore of Glamis Castle in Angus.

But Scotland has also been central to the British parliament and to British ministerial politics. The office of Prime Minister was dominated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Scots – six of the eleven Prime Ministers between 1868 and 1935 were Scottish by birth or origin (Gladstone, Rosebery, Balfour, Campbell-Bannerman, Bonar Law, MacDonald). Two later PMs were Scots: Alec Douglas-Home and Gordon Brown. Of the others, Asquith and Churchill represented Scottish constituencies for substantial parts of their parliamentary careers, while Baldwin, Harold Macmillan, and Tony Blair all boasted (or failed to boast) significant Scottish elements to their familial background.

This centrality has, paradoxically, formed a fundamental part of the current challenge to the existing union. The Labour Party has for long dominated Scottish parliamentary representation, and indeed the three party leaders preceding Ed Miliband were also Scots-born: John Smith, Tony Blair, and Gordon Brown. The Labour cabinets of Blair and Brown were heavily populated by Scots; the roll-call is striking: Douglas Alexander, Des Browne, Robin Cook, Alistair Darling, Donald Dewar, Lord (Charles) Falconer, Lord (Derry) Irvine, Helen Liddell, Ian McCartney, Jim Murphy, John Reid, George Robertson, Gavin Strang. One third of Tony Blair’s first cabinet (discounting Blair himself) were Scots at a time when the Scottish Labour contingent at Westminster represented only thirteen per cent of the parliamentary party.

Dunnottar Castle. Photo by Maciej Lewandowski (Macieklew). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Dunnottar Castle. Photo by Maciej Lewandowski (Macieklew). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. This (often) marked overrepresentation of talented Scots has been simultaneously a huge diversion of talent from the newly established devolved parliament at Holyrood, where Alex Salmond and the SNP speedily established an ascendancy. But it also meant that criticisms of the Labour government, and particularly under Brown, were sometimes coloured by distinct (English) national resentments. The dominance of Scots, and the unpopularity of the Labour government, created passions which evoked the Scotophobia raised in the 1760s by the administration of Lord Bute.

The significant presence of Scots in British public life, combined with a general metropolitan detachment from Scotland itself, has helped to create a set of passionate and shocked responses to the very rapid strengthening of Scottish nationalism, and to the real prospect of independence. The intense debate over the two year lead-in to the referendum of 18 September 2014, and in particular the ferocious debate within and outwith Scotland in the weeks before referendum day, signaled (arguably) a degree of constitutional political passion not matched in these islands since the era of Irish Home Rule, and in particular the political crisis generated by the third Home Rule Bill of 1912-14. There were clear differences: the debate over Home Rule took a turn into militancy, particularly after 1913. Tensions over Home Rule were exacerbated by Westminster’s repudiation of a long-settled nationalist electoral majority in Ireland. The probability of Home Rule did not come as a surprise to a British public long aware of the strength of Irish feeling on the issue. But there remains a clear symmetry between the passions, the moral visions, and the deep-seated apprehensions generated by the constitutional crises of 1914 and 2014.

So little wonder then that Scotland has topped the OUP poll. A combination of the centrality of Scotland within the key institutions of the British state, the ubiquity of Scots within British public life, and the rapid consolidation of the independence movement, has taken much of the United Kingdom and the wider world by surprise. The consequence has been a degree of impassioned political debate and indeed (in some quarters) panic.

The post Constitutional shock and awe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLooking beyond the Scottish referendumLooking back at Scotland in 2014An excerpt from Scotland: A Very Short Introduction

Related StoriesLooking beyond the Scottish referendumLooking back at Scotland in 2014An excerpt from Scotland: A Very Short Introduction

Climate shocks, dynastic cycles, and nomadic conquests

Nomadic conquests have helped shape world history. We may indulge ourselves for a moment to imagine the following counterfactuals: What if Western Europe did not fall to seminomadic Germanic tribes, or Western Europe was conquered by the Huns, Arabs, or Mongols, or Kievan Rus did not succumb to Mongolian invaders, or Ming China did not give way to the Manchu Qing? For centuries, the mere mention of the names of Attila, Genghis Khan, or Tamerlane could strike terror into men and women throughout Eurasia.

But why did nomadic conquests happen? How could nomadic people, often considered barbaric and backward, possibly conquer their agricultural neighbours who had more advanced technology and larger populations? If there had been only a few nomadic conquests in history, it could be put down to chance, or the military genius of someone like Genghis Khan. On the contrary, nomadic conquests have been a recurring phenomenon in world history, and there were at least eight nomadic conquests in ancient China alone. Although historians have provided vivid accounts of the rise of nomadic powers and their conquests, very little is known about the determinants of nomadic conquests.

Historical China (from 221 BCE – 1911) provides an interesting case for studying the determinants of nomadic conquests: Sino-nomadic conflict endured for over two millennia – not least because the Chinese people are known for their obsession with meticulous recording of historical events, including droughts, floods, snow, frost and low-temperature disasters.

It is well known that the nomadic way of life, notably the keeping of livestock, depended heavily on climate. Thus, even a small negative climate shock could upset the delicate nomadic equilibrium and prompt nomads to act against their sedentary neighbours for survival, a possibility known as the climate pulsation hypothesis. Previous studies have found that less rainfall, (proxied by a “decadal share of years with recorded drought disasters”) was associated with more frequent nomadic attacks of China proper, and more rainfall (proxied by a “decadal share of years with a levee breach of the Yellow River”) reduced the frequency of nomadic attacks.

Image: Ortelius World Map, 1570. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: Ortelius World Map, 1570. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. However, climate change by itself is not the only driver of nomadic conquests. First, there is the question of why China was conquered by some nomadic regimes but not others, when these regimes were subjected to the same climate shocks; for example, why was the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) conquered by the Jin (Jurchens), but not the Liao (Khitan) or the Western Xia (Xianbei), all of which coexisted for some period of time. Second, the frequency and the outcomes of nomadic attacks varied; the outcomes of attacks also depended on the relative strengths of nomadic and sedentary peoples, which are linked to their relative positions in dynastic cycles.

The dynastic cycle hypothesis proposes that all historical regimes had life cycles that included rises and falls, and passed through inevitable stages of growth, maturity and decline. Usually, a dynasty reached its height of power during and shortly after the reign of its founder. As time passed, vested interests became increasingly entrenched, with the ruling class growing ever more corrupt and inefficient, inevitably diminishing the dynasty’s political and military power. An implication of the dynastic cycle hypothesis is that if a Chinese dynasty was established much earlier than a competing nomadic regime, then China faced an awkward situation in which an aging Chinese dynasty was confronted by a rising nomadic regime, resulting in heightened risk of China being conquered.

The main conclusions of this study are twofold. First, consistent with the dynastic cycle hypothesis, the likelihood of China being conquered was significantly and positively related to how long a Chinese dynasty existed relative to its nomadic rival. To a degree, whether a Chinese dynasty was conquered by a nomadic regime depended on a timing mismatch between the Chinese dynasty and its nomadic counterpart. That is, a growing new Chinese dynasty could usually defend itself, whereas an aging Chinese dynasty often could not resist a rising nomadic power. Second, climate shocks played a significant role in nomadic conquests, as the likelihood of conquest increased with less rainfall as proxied by drought disasters. These results contribute to our understanding of the perennial conflict between settled and nomadic peoples in ancient China and throughout world history.

Nomadic conquests did not just happen by chance – there were systematic forces at work, such as climate shocks and dynastic cycles.

The post Climate shocks, dynastic cycles, and nomadic conquests appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCalling oral history bloggers – again!The Battle of the BulgeBehind Korematsu v. United States

Related StoriesCalling oral history bloggers – again!The Battle of the BulgeBehind Korematsu v. United States

December 19, 2014

Calling oral history bloggers – again!

Last April, we asked you to help us out with ideas for the Oral History Review’s blog. We got some great responses, and now we’re back to beg for more! We want to use our social media platforms to encourage discussion within the broad community oral historians, from professional historians to hobbyists. Part of encouraging that discussion is asking you all to contribute your thoughts and experiences.

Whether you have a follow up to your presentation at the Oral History Association Annual Meeting, a new project you want to share, an essay on your experiences doing oral history, or something completely different, we’d love to hear from you.

Whether you have a follow up to your presentation at the Oral History Association Annual Meeting, a new project you want to share, an essay on your experiences doing oral history, or something completely different, we’d love to hear from you.

We are currently looking for posts between 500-800 words or 15-20 minutes of audio or video. These are rough guidelines, however, so we are open to negotiation in terms of media and format. We should also stress that while we welcome posts that showcase a particular project, we can’t serve as landing page for anyone’s kickstarter.

Please direct any questions, pitches or submissions to the social media coordinator, Andrew Shaffer, at ohreview[at]gmail[dot]com. You can also message us on Twitter (@oralhistreview) or Facebook.

We look forward to hearing from you!

Image credits: (1) A row of colorful telephones stands in Bangkok’s Hua Lamphong train station. Photo by Mark Fischer. CC BY-SA 2.0 via fischerfotos Flickr. (2) Retro Microphone. © Kohlerphoto via iStockphoto.

The post Calling oral history bloggers – again! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingSo Long, FarewellTop 5 reasons why young professionals love the OHA Annual Meeting

Related StoriesRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingSo Long, FarewellTop 5 reasons why young professionals love the OHA Annual Meeting

Santa Claus breaks the law every year

Each year when the nights start growing longer, everyone’s favourite rotund old man emerges from his wintry hideaway in the fastness of the North Pole and dashes around the globe in a red and white blur, delivering presents and generally spreading goodwill to the people of the world. Who can criticise such good intentions?

Despite this noble cause, Father Christmas is running an unconventional operation at best. At worst, the jolly old fool is flagrantly flaunting the law and his reckless behaviour should see him standing before a jury of his peers. Admittedly, it would be a challenge to find eleven other omnipotent, eternally-old, portly men with a penchant for elves.

Read on to find out four shocking laws Santa breaks every year. But be warned; this is just the tip of an iceberg of criminality that dates back centuries!

1) Illegal Surveillance – Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000

Even before the Christmas season rolls around, Santa is actively engaged in full-time surveillance of 1.9 billion children. This scale of intelligence-gathering makes the guys at GCHQ look like children with a magnifying glass. In the course of compiling this colossal “naughty-or-nice” list, Santa probably violates every single privacy law ever created, but he is definitely breaking the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act. Even if Secretary of State William Hague gave Santa the authorisation required to carry out intrusive surveillance on all the children of the UK, the British government would go weak-at-the-knees at the thought of being complicit in an intelligence scandal set to dwarf Merkel’s phone tap and permanently sour Anglo-global relations!

Christmas crime films

Christmas crime films

The Battle of the Bulge

Each year on 16 December, in the little Belgian town of Bastogne, a celebrity arrives to throw bags of nuts at the townsfolk. This year, it will be Belgium’s King Philippe and Queen Mathilde who observe the tradition. It dates from Christmas 1944, when attacking Germans overwhelmed and surrounded the small town and demanded that the US forces defending Bastogne to surrender. The American commander, General Anthony McAuliffe, searching for a word to vent his frustration and defiance, simply answered: ‘Nuts!’

The day marked the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge. Fought over the winter of 1944-5, it was Hitler’s last desperate attempt to snatch victory over the Allied armies who had been steamrollering their way into the Reich following the invasion of Europe the previous June. The commemorations this year have an added poignancy as hardly any of the veterans who fought in the campaign are left alive. The local Belgians remain grateful to their wartime liberators. Some have begun another tradition, dressing in wartime GI uniforms, as a mark of respect and remembrance.

It is a battle worthy or remembrance. The Wehrmacht’s attack—aided by Allied intelligence lapses and the Nazi’s ruthless secrecy–fell on a thin line of GIs defending the Belgium-Luxemburg border. It came as a shock and a complete surprise. Fielding their last panzers and thousands of new units, the Germans created complete mayhem for a few days. It seemed as if they might break through, as US Army units reeled. The savagery of the battle was horrific. In some sectors, there was hand-to-hand combat in sub-zero cold, and thousands of Americans were taken prisoner. In thick fog and snow at Malmedy, another small Belgian town, some American prisoners were massacred by fanatical SS troopers.

Infantrymen, attached to the 4th Armored Division, fire at German troops, in the American advance to relieve the pressure on surrounded airborne troops in Bastogne, Belgium. Department of Defense. Department of the Army. Office of the Chief Signal Officer. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Infantrymen, attached to the 4th Armored Division, fire at German troops, in the American advance to relieve the pressure on surrounded airborne troops in Bastogne, Belgium. Department of Defense. Department of the Army. Office of the Chief Signal Officer. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. The German plan had been based on speed and surprise, and success was to be measured in days and even hours. But when faced with the resistance of American soldiers throughout the Ardennes regions of Luxembourg, including at Bastogne and St. Vith, the Wehrmacht’s advance slowed, then stopped. The Germans soon ran low on fuel, food, and ammunition, After battling for over forty days, and in the face of overwhelming US counter-attacks, Hitler’s armies were forced back to where they had started.

Winston Churchill hailed the end result as ‘an ever-famous American victory’. But it came at a high cost: at the end of the offensive, 89,000 American soldiers were casualties, including 19,000 dead. The Germans lost more. Some British units also took part, losing 1,400, and 3,000 Belgian civilians were killed, caught by shellfire in their own homes.

The Battle of the Ardennes, as it was called at the time, was America’s greatest—and bloodiest—battle of World War II, and indeed the bloodiest in its history. Some 32 divisions fought in it, totaling 610,000 men, a bigger commitment for the US Army than Normandy, where nineteen divisions fought, and far larger than the Pacific. More than D-Day and the battle for Normandy the Ardennes was a far more fundamental test of American soldiers. Surprised and outnumbered, sometimes leaderless and operating in Arctic weather conditions, they managed to prevail against the best men that Nazi Germany could throw against them.

The quality of an army is measured not when all is going to plan, but when the unexpected happens. The 1944-45 Ardennes campaign was a test and on a scale like no other. So on 16 December each year, spare a thought for those GI veterans and civilians in Belgium, perhaps when you’re munching on some holiday nuts.

The post The Battle of the Bulge appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBehind Korematsu v. United StatesThe Christmas truce: A sentimental dreamMagical Scotland: the Orkneys

Related StoriesBehind Korematsu v. United StatesThe Christmas truce: A sentimental dreamMagical Scotland: the Orkneys

10 medically-trained authors whose books all doctors should read

Sir William Osler, the great physician and bibliophile, recommended that his students should have a non-medical bedside library that could be dipped in and out of profitably to create the well rounded physician. Some of the works mentioned by him, for example Religio Medici by Sir Thomas Browne is unlikely to be on most people’s reading lists today. There have been several recent initiatives in medical schools to encourage and promote the role of humanities in the education of tomorrow’s doctors. Literature and cinema has a role to play in making doctors more empathetic and understanding the human condition.

My idiosyncratic choice of books is as follows.

Firstly, I start with a work by the most respected physician of the twentieth century, Sir William Osler himself. The work I choose is Aeqanimitas, published in 1905 and is a collection of essays and addresses to medical students and nurses with essays ranging in title from “Doctor and Nurse,” “Teacher and Student,” “Nurse and Patient,” and “The Student Life”. They are as relevant today as the day they were penned with a prose style combining erudition and mastery of language rarely seen in practicing physicians. Osler was the subject of the great biography, written by the famous neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing, who was to win a Pulitzer prize for his efforts. (I am not including this biography on my list, however.)

Anton Chekhov is included in my list for his short stories ( he was also a successful playwright). Chekhov was a qualified Russian doctor who practiced throughout his literary career, saying medicine was his lawful wife and literature his mistress. In addition to a cannon of short stories and plays, he was a great letter writer with the letters, written primarily while he traveled to the penal colony in Sakhalin. He was so moved by the inhumanity of the place, that these letters are considered to be some of his best. Chekhov succumbed to tuberculosis and died in 1904, aged only 44 years.

William Somerset Maugham, the great British storyteller was once described by a critic as a first rate writer of the second rank. Maugham suffered from club foot and was educated at the King’s School, Canterbury, and St. Thomas’s hospital, London where he qualified as a doctor. His first novel Liza of Lambeth, published in 1897 describes his student experience of midwifery work among the slums of Lambeth led him to give up medicine and earn a living writing. He became a prolific author of novels, short stories, and plays. His autobiographical novel Of Human Bondage describes his medical student years at St. Thomas’s Hospital. Many of his stories and novels were turned into successful films.

A portrait of W. Somerset Maugham. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

A portrait of W. Somerset Maugham. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsAnother medical student from the United Guy’s and St. Thomas’s Hospital who never practiced as a doctor ( although he walked the wards of Guy’s Hospital and studied under the distinguished surgeon Astley Cooper), was John Keats, who lived a tragically short life, but became one of the greatest poets of the English language. His first poem “O Solitude,” published in The Examiner in 1816, laid the foundations of his legacy as a great British Romantic poet. Poems the first volume of Keats verse was not initially received with great enthusiasm, but today his legacy as a great poet is undisputed. Keats died, aged 25, of tuberculosis.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, the famous North American nineteenth-century physician, poet and writer, and friend and biographer of Ralph Waldo Emerson, popularized the term “anaesthesia,” and invented the American stereoscope, or 3D picture viewer. Perhaps his best known work is The Autocrat at the Breakfast Table his 1858 work dealing with important philosophical issues about life.

In Britain over a century later, in 1971, the distinguished physician Richard Asher published a fine collection of essays, Richard Asher Talking Sense which showcase his brilliant wit, verbal agility and ability to debunk medical pomposity. His writings went on to influence a subsequent generation of medical writers.

In the United States, another great physician and essayist was Sherwin Nuland, a surgeon whose accessible 1994 work How We Die became one of the twentieth centuries great books on this important topic a discourse on man’s inevitably fate.

Two modern authors next. The popular American writer Michael Crichton was a physician and immunologist before becoming an immensely successful best-selling author of books like Five Patients, The Great Train Robbery, Congo, and Jurassic Park, which was of course turned into a very popular film by the American film director Stephen Spielberg.

Khaled Hosseini the Afghan-born American physician turned writer is a recent joiner of the club of physician-writers, having achieved great fame with his books The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns.

I suppose we must finally include Sir Arthur Conan Doyle the Scottish physician and author. His stories of the sleuth Sherlock Holmes have given generations pleasure and entertainment, borne of the sharp eye of the masterful physician in Conan Doyle.

Heading image: Books. Public Domain via Pixabay

The post 10 medically-trained authors whose books all doctors should read appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDruids and natureBehind Korematsu v. United StatesFive tips for music directors during the holiday season

Related StoriesDruids and natureBehind Korematsu v. United StatesFive tips for music directors during the holiday season

Druids and nature

What was the relationship between the Druids and nature? The excerpt below from Druids: A Very Short Introduction looks at seasonal cycles, the winter solstice, and how the Druids charted the movement of the sun, moon, and stars:

How far back in time European communities began to recognize and chart the movements of the sun, moon, and stars it is impossible to say, but for the mobile hunting bands of the Palaeolithic period, following large herds through the forests of Europe and returning to base camps when the hunt was over, the ability to navigate using the stars would have been vital to existence. Similarly, indicators of the changing seasons would have signalled the time to begin specific tasks in the annual cycle of activity. For communities living by the sea, the tides provided a finer rhythm while tidal amplitude could be related to lunar cycles, offering a precise system for estimating the passage of time. The evening disappearance of the sun below the horizon must have been a source of wonder and speculation. Living close to nature, with one’s very existence depending upon seasonal cycles of rebirth and death, inevitably focused the mind on the celestial bodies as indicators of the driving force of time. Once the inevitability of the seasonal cycles was fully recognized, it would have been a short step to believing that the movements of the sun and the moon had a controlling power over the natural world.

The spread of food-producing regimes into western Europe in the middle of the 6th millennium led to a more sedentary lifestyle and brought communities closer to the seasonal cycle, which governed the planting of crops and the management of flocks and herds. A proper adherence to the rhythm of time, and the propitiation of the deities who governed it, ensured fertility and productivity.

The sophistication of these early Neolithic communities in measuring time is vividly demonstrated by the alignments of the megalithic tombs and other monuments built in the 4th and 3rd millennia. The great passage tomb of New Grange in the Boyne Valley in Ireland was carefully aligned so that at dawn on the day of the midwinter solstice the rays of the rising sun would shine through a slot in the roof and along the passage to light up a triple spiral carved on an orthostat set at the back of the central chamber. The contemporary passage grave at Maes Howe on Orkney was equally carefully placed so that the light of the setting sun on the midwinter solstice would flow down the side of the passage before filling the central chamber at the end. The passage grave of Knowth, in the same group as New Grange, offers further refinements.

Stonehenge, by .aditya. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Stonehenge, by .aditya. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Here there are two separate passages exactly aligned east to west: the west-facing passage captures the setting sun on the spring and autumn equinoxes (21 March and 21 September), while the east-facing passage is lit up by the rising sun on the same days. The nearby passage grave of Dowth appears to respect other solar alignments and, although it has not been properly tested, there is a strong possibility that the west-south-west orientation of its main passage was designed to capture the setting sun on the winter cross-quarter days (November and February) half way between the equinox and the solstice.

Other monuments, most notably stone circles, have also been claimed to have been laid out in relation to significant celestial events. The most famous is Stonehenge, the alignment of which was deliberately set to respect the midsummer sunrise and the midwinter sunset.

From the evidence before us there can be little doubt that by about 3000 BC the communities of Atlantic Europe had developed a deep understanding of the solar and lunar calendars – an understanding that could only have come from close observation and careful recording over periods of years. That understanding was monumentalized in the architectural arrangement of certain of the megalithic tombs and stone circles. What was the motivation for this we can only guess – to pay homage to the gods who controlled the heavens?; to gain from the power released on these special days?; to be able to chart the passing of the year? – these are all distinct possibilities. But perhaps there was another motive. By building these precisely planned structures, the communities were demonstrating their knowledge of, and their ability to ‘contain’, the phenomenon: they were entering into an agreement with the deities – a partnership – which guaranteed a level of order in the chaos and uncertainty of the natural world.

The people who made the observations and recorded them, and later coerced the community into the coordinated activity that created the remarkable array of monumental structures, were individuals of rare ability – the keepers of knowledge and the mediators between common humanity and the gods. They were essential to the wellbeing of society, and we can only suppose that society revered them.

The post Druids and nature appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCarols and CatholicismAn excerpt from Scotland: A Very Short IntroductionBehind Korematsu v. United States

Related StoriesCarols and CatholicismAn excerpt from Scotland: A Very Short IntroductionBehind Korematsu v. United States

December 18, 2014

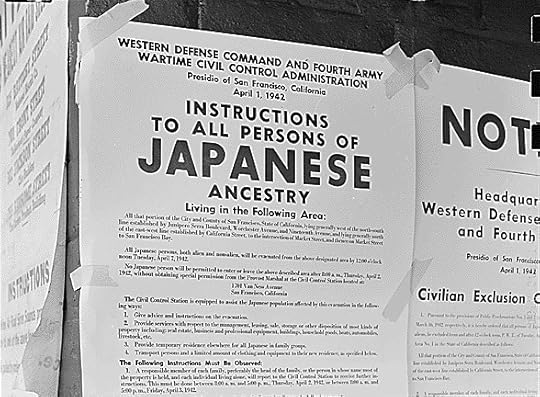

Behind Korematsu v. United States

Seventy years ago today, in Korematsu v. United States, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Japanese-American internment program authorized by President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. The Korematsu decision and the internment program that forcibly removed over 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry from their homes during World War II are often cited as ugly reminders of the dangers associated with wartime hysteria, racism, fear-mongering, xenophobia, an imperial president, and judicial dereliction of duty. But the events surrounding Korematsu are also a harrowing reminder of what happens to liberty when the “Madisonian machine” breaks down — that is, when the structural checks and balances built into our system of government fail and give way to the worst forms of tyranny.

Our 18th century system of separated and fragmented government — what Gordon Silverstein calls the “Madisonian machine” — was engineered to prevent tyranny, or rather tyrannies. Madison’s Federalist 51 outlines a prescription for avoiding “Big T Tyranny” — the concentration of power in any one branch of government. This would be accomplished by dividing and separating powers among the three branches of government and between the federal government and the states. “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” Madison wrote. Each branch would jealously protect its own powers while guarding against encroachments by the others.

But this wasn’t the only form of tyranny the framers worried about. In a democracy, minorities are always at risk of being oppressed by majorities — what I call “little t tyranny.” Madison’s solution to this kind of tyranny is articulated in Federalist 10. The cure to this disease was firstly to elect representatives who could filter the passions of the masses and make more enlightened decisions. Secondly, Madison observed that as long as the citizenry is sufficiently divided and carved up into numerous smaller “factions,” it would be unlikely that a unified majority would emerge to oppress a minority faction.

Official notice of exclusion and removal. By Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Official notice of exclusion and removal. By Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In the events leading up to and including the Supreme Court’s decision in Korematsu, these safeguards built into the Madisonian machine broke down, giving way to both forms of T/tyranny. Congress not only acquiesced to President Roosevelt’s executive order, it responded with alacrity to support it. After just one hour of floor debate and virtually no dissent, Congress passed Public Law 503, which promulgated the order and assigned criminal penalties for violating it. And the branch furthest removed from the whims and passions of the majority, the Supreme Court, declined to second-guess the wisdom of the elected branches. As Justice Hugo Black wrote for the majority in Korematsu, “we cannot reject as unfounded the judgment of the military authorities and of Congress…” If Congress had been more skeptical, perhaps the Supreme Court might have been, too. But the Supreme Court has a long track record of deference to the executive when Congress gives express consent for his actions – especially in times of war. Unfortunately, under the Madisonian design, this is exactly when the Supreme Court ought to be the most skeptical of executive power.

To be sure, these checks and balances built into the Madisonian system were only meant to function as “auxiliary precautions.” The most important safeguard against T/tyranny would be the people themselves. Through a campaign of misinformation and fear-mongering, however, this protection was also rendered ineffective. Public opinion data was used selectively to convey the impression to both legislators and west coast citizens that the majority of Americans supported the internment program. The passions of the public were further manipulated by the media and west coast newspaper headlines such as “Japanese Here Sent Vital Data to Tokyo,” “Lincoln Would Intern Japs,” and “Danger in Delaying Jap Removal Cited.” Any dissent or would-be countervailing “factions,” to use Madison’s phrase, were effectively silenced.

In Korematsu, ambition did not counteract ambition as Madison had intended, and the machine broke down. That’s because in order to function properly, the Madisonian machine requires access to information and time for genuine deliberation. It also requires friction. It requires people to disagree – for our elected representatives to disagree with one another, for the Supreme Court to police the elected branches, for citizens to pause, faction off, and check one another. So we can complain of gridlock in government, but let’s not forget that the alternative, as demonstrated by the unforgivable and tragic events of Korematsu, exposes the most vulnerable among us to the worst forms of tyranny.

Featured image credit: A young evacuee of Japanese ancestry waits with the family baggage before leaving by bus for an assembly center. US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Behind Korematsu v. United States appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRelax, inhale, and think of Horace WellsHow Malcolm X’s visit to the Oxford Union is relevant todayFive tips for music directors during the holiday season

Related StoriesRelax, inhale, and think of Horace WellsHow Malcolm X’s visit to the Oxford Union is relevant todayFive tips for music directors during the holiday season

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers