Oxford University Press's Blog, page 731

December 1, 2014

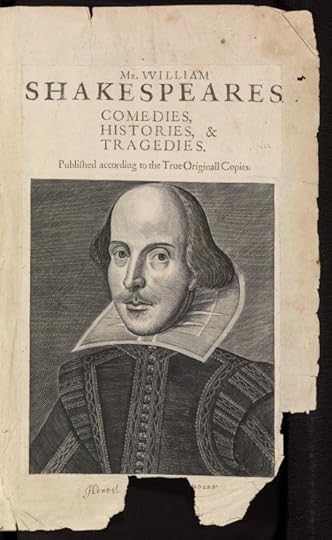

Shakespeare folio number 233

News that a previously unknown copy of the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays has been discovered in a French library has been excitedly picked up by the worldwide press. But apart from the treasure-hunt appeal of this story, does it really matter that instead of the 232 copies of this book listed by Eric Rasmussen and Anthony West in their The Shakespeare First Folios: A Descriptive Catalogue (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), there are now, apparently, 233? A book that was never particularly rare is now just a little bit less rare. Whoop dee doo. It’s not quite the discovery of – say – a new copy of the first edition of Venus and Adonis or Hamlet, each of which exists in only a single complete copy, still less the discovery of the lost ‘Cardenio’ or ‘Love’s Labour’s Won’: plays attributed to Shakespeare in the early modern period that have not survived. So (how) does it matter?

An easy answer is that every copy of an early modern book is unique. Around 500 press variants in copies of the First Folio have been identified, attesting to processes of proof-reading and stop-press correction in the printing shop of William and Isaac Jaggard at the Barbican where the book was produced. The St Omer copy may well have a different arrangement of corrected and uncorrected sheets than any other extant Folio. Some copies even include proof-sheets marked up with corrections: this one might provide another example. A full bibliographic description of the new find might also add to our understanding of, for example, the late inclusion of Troilus and Cressida in the First Folio, apparently because of problems about securing the rights to publish it. A couple of extant copies show the difficulties in placing this belated play, with cancelled sheets showing how the order of the plays had to be rethought: a new copy might shine new light on this bibliographic puzzle.

Image: Digital facsimile of the Bodleian First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, Arch. G c.7: CC-BY-3.0 via The Bodleian Library.

Image: Digital facsimile of the Bodleian First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, Arch. G c.7: CC-BY-3.0 via The Bodleian Library.Perhaps more immediately arresting about the new copy, though, is how it might develop our understanding of how the travels of the First Folio established and extended Shakespeare’s reputation and reach. Most copies of the First Folio show signs of use: the book that libraries now treat almost as a religious relic was once part of the everyday mess and activity of the household: a book for use rather than ornament. Seeing how this copy can testify to those forms of early use will add to the knowledge of how Shakespeare was consumed in the first century of the book’s life, before cheaper, more convenient reprints of the plays, beginning with Nicholas Rowe in 1709, replaced it as a standard reading edition.

The specific provenance of this new copy is tantalizing. Few details have emerged, but they immediately set off some very suggestive lines of inquiry. The St Omer librarians indicate that Henry IV is marked with some kind of early performance notes. If this is true, then it is a rare – although not unique – example of a copy that can be related to early theatrical performance in some way.

They also suggest it has the name ‘Nevill’ written in it, and speculate that this person may have been one of the students at the Jesuit college in St Omer which, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was an important training institution for English Catholics. In fact it might be possible to push a bit further with this identification: members of the prominent Jesuit family the Scarisbricks, from Ormskirk in Lancashire, took the name Neville. Edward Scarisbrick, born in 1639, was educated and later stationed at Saint-Omer. Perhaps he, or another member of his family, made his mark in their copy of Shakespeare. On his return to England at the beginning of the eighteenth century, he also wrote his name in another copy of the First Folio now in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC. Other Jesuit associations can also be traced. There’s a First Folio in Stonyhurst College – the English descendant of St Omer’s college. The English college at Valladolid had a copy of the 1632 edition of Shakespeare, heavily censored. The seedy nuns-and-friar comedy Measure for Measure was obviously beyond redemption, and has been torn in its entirety from the volume (that book is now also at the Folger). We don’t yet know if there is any censorship evident in the Saint Omer text.

So Folio 233 potentially has lots to tell us about the spread of Shakespeare in the seventeenth century, about his early readers and about the intellectual and religious contexts and predispositions they brought to their reading. The book itself may not be rare, but its specific journey since its publication – still to be explored – is what makes it unique.

The post Shakespeare folio number 233 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesShakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnetsThe impossible paintingA Q&A with a Keytar player

Related StoriesShakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnetsThe impossible paintingA Q&A with a Keytar player

November 30, 2014

What to expect on your 19th century Indus river steamer journey

Congratulations on your new posting in the Punjab. Rather than riding eight-hours-a-day on horseback, suffering motion-sickness on a camel’s heaving back, or breaking your back sitting on hard wooden boards in a mail-cart, you’ll be travelling on the Bombay Government Flotilla, one of four flotillas that carry thousands of Europeans and Indians up and down the Indus.

While you may question the expenditure of a government flotilla, we assure you it’s a lot simpler than loading a squadron onto a small fleet of country boats, with indifferent crews, in varying states of repair, which might never reach their destinations. On board we’ll keeping the regiment together arriving as it started out — in one piece and maintaining proper discipline in transit.

So what can you expect on this exciting journey?

1. Expect sun and swelter. Everything you touch will be red hot. You won’t be able to go below in the daytime, but the thin awnings on deck will do little to relieve you in the 115 degree heat. Many soldiers ask whether they should sleep with a berth next to a furnace or choose a wall of heat on deck. With dry winds that come down from the ‘burnt-up hills’, laden with fine sand, everything and everyone will be covered in a layer of fine grey grit. And don’t forget the sand-flies — they bite hard.

2. Expect an uproarious time. Remember that you’re travelling on white man’s mastery of nature, so don’t expect to be the most important thing afloat. Your accommodation will be conveniently crushed between the machinery of furnaces, boilers, pistons, transmission, and paddle-wheels. Passengers trapped in close proximity to the machinery enthuse about the clamour of pistons ‘working up to four or five hundred horse-power’, the splash of paddle-wheels beating the river-water into foam, and the deafening hurricanes when engineers blow off the boiler’s steam ‘half-a-dozen times a day’. And if you’re lucky enough to have the wind blowing in your direction, look forward to being choked by the smoke, singed by the sparks, and splattered by smuts from the funnels.

3. Expect to get intimate with your fellow passengers. When moving to a theatre of war, you’ll be squashed together on the decks ‘like pigs at a market in a pen at night’. Your comrades may jostle to get enough space to lie down; the top of a hatch is a prize reserved for the best bare-knuckle fighter. Never mind about a restless colleague, you’ll be packed so tight in the gaps between the baggage, that once you’re settled down it’ll be impossible to move until the morning.

4. Expect cool nights with fresh dew. As you lay on deck with only a thin cotton awning over your head, gather round the funnel to get a little warmth. Be sure to hang on to your guttery [very thin duvet stuffed with raw cotton] as there will be no great-coats among the soldiers. Not to worry, the women and children suffer most.

5. Expect to be out of your element and out of sorts. Feeling exposed? Living on the open decks for weeks on end in the winter will reduce your resistance to all common Indian diseases. Should you be lucky enough to get an attack fever and dysentery, you’ll lay stretched upon the hard planking without anything under or over you. The sepoys’ conditions, as one would expect, are the best of all. It will be impossible to cross the deck without walking on sick and dying invalids. If they die in the night, they will be ‘instantly thrown overboard’. And after the steamer arrives in the delta, the survivors are off-loaded into sea-going ships destined for Bombay.

A daguerreotype of a typical river paddle steamer from the 1850s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A daguerreotype of a typical river paddle steamer from the 1850s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 6. Expect unbelievable meals. Passengers praise our ‘coarse and unpalatable’ food. Everyone from the boat captains to the cooks have their special arrangements with prices too high for poorer travellers and meals ‘so indifferent’ that passengers who had paid for them refuse to eat them. Even the water is undrinkable! Perhaps your whole regiment will be reduced to foraging in the villages along the banks. Sheep and cows can be bought for a few rupees; Muslim butchers slaughter them; and you can enjoy broiling away till midnight.

7. Expect a tranquil environment. It takes a month or more to get up the whole navigable length of the Indus and they’ll be nothing to see on long stretches of the rivers, except ‘a vast dreary expanse’ of desert stretching out to the horizon, or an endless belt of tamarisk trees running along the low, muddy banks. Many villages are miles from the river to escape the floods, so it’s possible to sail all day without seeing another human being. Throughout the journey you’ll receive small stimulations from a native boat spreading its sail to taking pot shots at the largest living creatures to hand. Never mind the cost of the cartridges: simply steal rounds from the pouches of sick sepoys.

8. Expect a friendly drink or two. Fed up with watching the ‘dreary wilderness’ floating slowly past? Drink yourself stupid. As a hundred soldiers boarded the Meanee en route to the siege of Multan, one of them – delirious from drink – ‘slipped from the men who led him and fell overboard’, a second died of delirium tremens during the voyage, and a third ‘was expected to do so’. En route they ‘lost three or four in the river from drowning’. Worried the military authorities will restrict the sale of alcohol on the boats? Buy country liquor from the villagers – it has roughly the same side-effects.

9. Expect genuine thrills. The most intense excitement on a voyage on the Indus is the occasional shipwreck. Test your phlegm, and proof of national identity. Charles Stewart dismissed the danger of drowning with the utmost nonchalance on his sinking vessel. The really serious inconvenience was the interruption to his meals. React with that much aplomb, and we’ll know you’re British.

10. Expect to see people working together in new ways. Watch every latent animosity in race relations come to the surface. British captains beat Indian pilots every time a boat runs aground; engineers beat the lascars feeding logs into the furnaces if the steam pressure falls; and soldiers beat the cooks if they make a mess of the grub. Passengers straight from England are often shocked.

Remember, in an alien and often threatening environment, it’s worth paying a premium for the reassurance of a European-style cocoon: a steam-hotel, albeit a poor one, gliding along the river while the guests sit on the decks.

Headline image credit: Indus Sunset by Ahmed Sajjad Zaidi. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What to expect on your 19th century Indus river steamer journey appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLest we forgetSlavery, rooted in America’s early historyNature in motion: migration and its implications

Related StoriesLest we forgetSlavery, rooted in America’s early historyNature in motion: migration and its implications

Income inequality in the United States

How has the average American income shifted since the US Census bureau began collecting data in the 1950s? Are median wages rising or falling? Andrew Beveridge, Co-Founder and CEO of census data mapping program Social Explorer, gives us the hard data on income inequality in the United States. In the short video below, Beveridge analyzes decades of income data from the American census to illuminate the factors causing this economic disparity, which has increased significantly over the past four decades. Exploring median average income and wages through time, along with the implications behind these changes, allows for a more complete picture of the increasing wealth gap among modern-day Americans.

Featured image credit: A man sleeping under a luxury condo sign on the street of The Bowery in Manhattan. Photo by David Shankbone. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Income inequality in the United States appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWho should be shamefaced?The impossible painting

Related StoriesWho should be shamefaced?The impossible painting

Nature in motion: migration and its implications

For those of us living in the northern hemisphere one of the great annual events of nature is winding down. This is the autumn migration of numerous species from summer breeding grounds to wintering areas farther south. Even to the most casual observers of nature, it is apparent that migration is a conspicuous behavior for many organisms. Great whales moving along our coasts attract watchers to excursion vessels and promontories on our coasts; echelons of ducks, geese, and swans fly in V-formations to marshes and estuaries; and in North America millions of bright orange monarch butterflies inspire awe with their migrations to wintering sites in the mountains of central Mexico and the coast of California. Equally apparent, to the dismay of agriculture the world over, are the migrations of insects like locusts and armyworm moths that can cause enormous crop losses, even to the extent of stripping fields of ‘any green thing’ in the words of the Book of Exodus. What is not so appreciated, however, are the numerous tiny insects, mites, and spiderlings that also migrate. On spring and summer evenings at temperate latitudes the air to considerable heights is often filled with aphids and ballooning spiders that with the aid of selected winds can migrate for hundreds or even thousands of kilometers. From the tiniest to the largest of organisms migration can play a crucial role in the life cycle, allowing the exploitation of resources that can be distant in both space and time.

New methods reveal just how dramatic some migrations can be. Geolocators no larger than a fingernail attached to godwits have shown that these shorebirds departing Alaska in the autumn fly nonstop to their nonbreeding areas in Australia and New Zealand. Radio transmitters attached to European storks communicate with orbiting satellites and show that the tracks of birds migrating from eastern Europe to eastern and southern Africa often wander widely even as far Nigeria before heading back eastward to the wintering areas. Radar tracking of migrating moths demonstrates that these insects possess highly sophisticated navigation systems that allow them to select winds of seasonally appropriate directions to assist them on their passage. Winds are a major factor in migratory performance from tiny aphids to large raptorial birds like vultures and eagles. In the ocean and tidal estuaries currents assist the migrations of marine denizens from crab larvae returning to salt marshes to become breeding adults to sea turtles returning to nesting beaches from remote reaches of the open ocean.

Green sea turtle migration. Photo by Brocken Inaglory. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Green sea turtle migration. Photo by Brocken Inaglory. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons Migration for an individual is a ‘complete package’ of physiology, behavior, and ecology. Important defining behavioral characteristics include specific arrival and departure tactics and the refusal to stop even in favorable habitats until the migration program is complete. This is as true of the one-way migration flights of aphids as it is of the nearly pole to pole round-trips of arctic terns. In the words of David Quammen migrants “are flat-out just gonna get there.” The program or syndrome includes specific modifications of metabolic physiology like enhanced fat storage to fuel transit, and of sensory systems to detect inputs from the sun, stars, and magnetic field lines that indicate compass direction. Intimately involved in the latter are daily and yearly biological clocks – daily to time the movements of sun or stars and yearly to time the seasons. The pathway followed, whether round-trip in long-lived organisms or one-way in the short-lived is an outcome of the syndrome of migratory behavior and physiology and is part of the ecology that provides the natural selection acting to determine the evolution of migration. The whole performance has been likened to a marathon, but as Chris Guglielmo of the University of Western Ontario points out, the modifications of performance required make migration more akin to a trip to the moon than a marathon.

Migration syndromes ensure that a huge number and biomass of migrants move over the surface of the earth and impact ecosystems in a variety of ways many little appreciated. We are aware of the impacts of migrant pests on agriculture enhanced by our predilection to plant monocultures of ruderal crops that provide optimal habitats for these invaders. We are less aware of the benefits provided by migrants. Migrant birds and bats consume enormous quantities of insects, and it is hard to imagine what our world would like without this consumption. Many migrants transport energy and nutrients from one ecosystem to another. Salmon, for example, carry nutrients from the ocean thousands of kilometers inland where they fertilize both fresh waters and neighboring terrestrial environments via the predators and scavengers that feed on them. Not long ago salmon provided us with abundant cheap and healthy protein (the ‘poverty steak’ of the Great Depression), but we have now so dammed and polluted their freshwater rivers that current migrations are either extinct or shadows of their former abundance. Overall we have not treated migrants particularly well, and one wonders what a future of continued human population growth, overexploitation of our resources, and the consequences of a changing climate have in store for them. Migrants are a wonder, a resource, and an inspiration impacting humanity over most of the globe. They deserve our attention and protection.

Featured Image: Butterfly migration. Photo by Hillebrand Steve, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Public Domain.

The post Nature in motion: migration and its implications appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe impossible paintingLest we forgetOUP staff discuss their favorite independent bookstores

Related StoriesThe impossible paintingLest we forgetOUP staff discuss their favorite independent bookstores

The impossible painting

Supposedly, early 20th century packaging for Quaker Oats depicted the eponymous Quaker holding a package of the oats, where the art on this package depicted the Quaker holding a package of the oats, which itself depicted the Quaker holding a package of the oats, ad infinitum. I have not been able to locate an photograph of the packaging, but more than one philosopher and mathematician has attributed an early interest in the nature of the infinite to childhood contemplation of this image. Here, however, I want to examine a different phenomenon: whether artwork that depicts itself in this way can lead to paradoxes.

Let’s begin with two well-known puzzles. The older of the two– the Liar paradox – was known to ancient Greek philosophers, and challenges the following platitudes about truth:

(T1) A sentence is true if and only if what it says is the case.

(T2) Every sentence is exactly one of true and false.

Consider the Liar sentence:

This sentence is false.

Is the Liar sentence true or false? If it is true, then what it says must be the case. It says it is false, so this means it is false. If it’s false, then, since it says it is false, what it says is indeed the case. But this would make it true. So the Liar sentence is true if and only if it is false, violating the platitudes.

The second puzzle is the Russell paradox, discovered by Bertrand Russell at the beginning of the 20th Century. This paradox involves collections, or sets, of objects, and two central theses:

(S1) Given any property P, there is a set of objects containing all and only the objects that have P.

(S2) Sets are themselves objects, and can be contained in sets.

Given (S2), we can divide objects into two types: Those that contain themselves (such as the set containing all sets whatsoever) and those that do not contain themselves (such as the set of all kittens). Thus, “is a set that does not contain itself” picks out a perfectly good property, and so by (S1) there should be a set – let’s call it R – containing exactly those things that have this property. So:

A set is a member of R if and only if it is not a member of itself.

Now, is R a member of itself? Either it is or it isn’t. If R is a member of itself then R isn’t a member of itself. And if R isn’t a member of itself then R is a member of itself. Either way, R both is and isn’t a member of itself. Again, a contradiction.

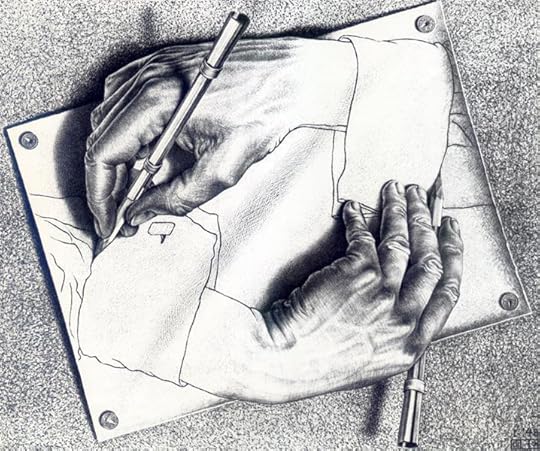

‘Drawing Hands’ 1948 M.C Escher. Public domain via WikiArt.org

‘Drawing Hands’ 1948 M.C Escher. Public domain via WikiArt.org There is another puzzle that seems intimately connected to these two paradoxes, however, that has not (as far as I know) been noticed or studied – the paradox of the impossible painting. This paradox stems from two principles governing the notion of depiction (or representation) rather than truth or set-theoretic membership.

First, it seems, at least at first glance, that we can paint anything that we can describe – if I tell you to paint a forest with exactly 28 trees, then you can produce a painting fitting that description. Thus:

(D1) Given any description D, we can create a painting that depicts things exactly as described in D.

Second, there is nothing to prevent a painting from being depicted within another painting – for example, Velazquez’s Las Meninas depicts the painter working on another painting. Thus:

(D2) Paintings can be depicted in paintings.

If some paintings can depict other paintings, then it seems like we can divide paintings into two types: those that depict themselves (such as the artwork on old Quaker Oats packaging) and those that do not. Thus, “a scene depicting all and only the paintings that do not depict themselves” is a perfectly good description, and so by (D1) it should be possible to produce a painting – let’s call it I – that depicts things as described. So:

A painting is depicted in I if and only if it does not depict itself.

Should I depict itself ? In other words, if you are creating this painting, should you include a depiction of I itself within the scene? If you include I in the painting, then I is a painting that depicts itself, so it should not be depicted in I after all. But if you don’t include I in the painting, then I is a painting that does not depict itself, so it should have been included. Either way, you can’t create a painting that depicts things exactly as described.

The paradox of the impossible painting is distinct from both the Liar paradox and the Russell paradox, since it involves depiction rather than truth or set-membership. But it has features in common with each. Most obviously, circularity plays a central role in all three paradoxes: the Liar paradox involves sentences that says something about themselves, the Russell paradox involves sets that are members of themselves, and the paradox of the impossible painting involves paintings that depict themselves.

“Who knew oats could be so deep?”

Nevertheless, the paradox of the impossible painting has features not shared by the Liar paradox, and other features not shared by the Russell paradox. First, the Liar paradox involves a sentence that clearly exists (and is grammatical, etc.) that must be accounted for, while the Russell paradox can be seen in different terms, as a sort of proof that the Russell set R just doesn’t exist, and that we need to revise (S1) accordingly. The proper response regarding the paradox of the impossible painting is more like the latter – we are not tempted to think that the paradoxical painting does or could exist, but instead conclude that there is something wrong with (D1).

There is another sense, however, in which the paradox of the impossible painting is more like the Liar paradox than the Russell paradox. The Liar paradox arguably arises because of circularity of reference: the Liar sentence refers to, or ‘picks out’, itself. And the paradox of the impossible painting arises because of circularity of depiction – that is, paintings that depict, or ‘pick out’, themselves. Reference and depiction are different, but, insofar as they are both ways of ‘picking out’, while set-theoretic membership is not, suggests that, in this respect at least, the paradox of the impossible painting has more in common with the Liar paradox than with the Russell paradox.

Thus, the paradox of the impossible painting ‘lies between’, or is a sort of hybrid of, the Liar paradox and the Russell paradox, with some features in common with the former and others in common with the latter. As a result, studying this puzzle further seems likely to reward us with deeper insights into these two much older and more well-known conundra. Who knew oats could be so deep?

The post The impossible painting appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Q&A with a Keytar playerThanks, teacher: musicians reflect on special ways a teacher helped them learn their craftThank you: musicians recall special ways their parents helped them blossom

Related StoriesA Q&A with a Keytar playerThanks, teacher: musicians reflect on special ways a teacher helped them learn their craftThank you: musicians recall special ways their parents helped them blossom

November 29, 2014

Lest we forget

One hundred years ago, in September 1914, Australia began its first ever joint military operation. The occupation of German New Guinea, taking place more than seven months before the Anzac landings, will always be overshadowed by the larger and more violent event at Gallipoli, but in its own regional context it was at least equally significant. Initiated in response to a British request, the operation sought to achieve a number of important outcomes in support of the Empire’s war effort, including the acquisition of German colonial resources, the disruption of Germany’s Pacific communications and the denial of an important coaling base to the German Navy’s East Asian Cruiser Squadron.

The force assembled for the occupation, known officially as the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF), numbered around 1500 troops, and their rapid deployment in the armed transport Berrima stands as a notable achievement for a people who had been at war for just over a month. Among the many newly enlisted military men were several companies of experienced naval reservists and protection for the whole came from a large Australian naval flotilla that included a battlecruiser, three cruisers, three destroyers, two submarines, and a gunboat. These warships would ensure that the German East Asian Squadron did not interfere. Auxiliary vessels were also required to provide fuel and stores and, since German resistance seemed likely, among them was the well-appointed hospital ship Grantala, with an embarked medical staff of more than 50, including a matron and six nurses. Although largely unrecognised at the time, these women became the Australian Navy’s first female entrants.

Embarkation of the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) for New Guinea. At the request of the British Government a special force, the Australian Navy and Military Expeditionary Force, was raised between 10 August 1914 and 18 August 1914, and despatched against the neighbouring German colonies. Public domain via Australian War Memorial.

Embarkation of the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) for New Guinea. At the request of the British Government a special force, the Australian Navy and Military Expeditionary Force, was raised between 10 August 1914 and 18 August 1914, and despatched against the neighbouring German colonies. Public domain via Australian War Memorial. The operation’s initial objective was the wireless station at Bitapaka near the German colonial capital at Rabaul, and the first landing by a company of naval reservists took place at dawn on 11 September at the small stone jetty at Kabakaul. Ashore, the enemy numbered some 300 German and native troops. They had prepared several well-defended trenches along the main road leading from Kabakaul, but by bold action and bluff the Australian naval men outflanked and overwhelmed the opposition and completed the destruction of the wireless station. For his bravery during the action, naval Lieutenant Thomas Bond was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, the first Australian serviceman to be decorated in World War I.

AN&MEF casualties were remarkably light, but included six killed and four wounded, again the first to be suffered by Australian forces during the war. Enemy casualties amounted to at least 31 killed, 11 wounded and 75 taken prisoner. Threatened by the big guns of the fleet and unable to contemplate further resistance, the local German Governor capitulated soon afterwards, and then in a series of bloodless affairs the Australians proceeded to occupy the remainder of German New Guinea.

In all, it was a remarkably successful expedition, expanding Australian influence at a critical time and highlighting what the young nation could achieve on its own account. But there remained one further tragedy to be suffered. On 14 September, the Australian submarine AE1 failed to return from a routine patrol outside Rabaul. A succession of searches revealed no trace either of the submarine or its crew, and it seems likely that she sank during a test dive, possibly following a marine accident. The loss, the new Navy’s first, brought condolences from around the Empire and has continued to be remembered by successive generations of naval men and women. This month, a new search has begun using a modern Australian minehunter, HMAS Yarra. We could do no better than wish her crew every success in their attempt to find the wreck.

Headline image credit: The light cruiser HMAS Sydney steams towards Rabaul. The Australian Naval & Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF), which included HMAS Sydney, HMAS Australia, HMAS Encounter, HMAS Warrego, HMAS Yarra and HMAS Parramatta, seized control of German New Guinea on 11 September 1914. Public domain via Australian War Memorial.

This article originally appeared on the Oxford Australia blog.

The post Lest we forget appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSlavery, rooted in America’s early historyThe history of the newspaperArmistice Day: an interactive bibliography

Related StoriesSlavery, rooted in America’s early historyThe history of the newspaperArmistice Day: an interactive bibliography

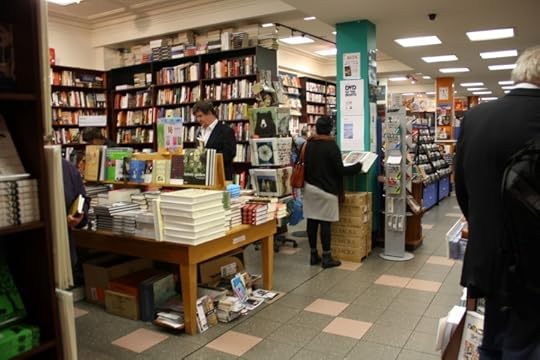

OUP staff discuss their favorite independent bookstores

In support of Indies First, a campaign run by the American Booksellers Association that supports independent bookstores, we asked Oxford University Press USA staff what their favorite independent bookstores were. We received quite an enthusiastic response, and discovered that our staff visits and revisits indies all over the country thanks to the love that these bookstores inspire. Here’s what they had to say about their personal favorites:

* * *

“My favorite thing about walking into town is grabbing a cup of coffee and stopping into Watchung Booksellers (Montclair, NJ). The store has a great collection of local authors, a nice selection of literature, and a fun and interactive children’s room. The staff is friendly and they are super creative in their events and workshops. It is a true neighborhood treasure.”

— Colleen Scollans, Global Marketing Director

* * *

“Unnameable Books – This is my local store in Prospect Heights on Vanderbilt Ave. I considered it a good omen that the store opened a few months before I moved to the neighborhood in 2009. Unnameable has a great selection of new and used books, and I still remember finding a copy of Anais Nin’s diary that I wanted to give a gift (published last year by Swallow Press, an imprint of Ohio University Press) and by some miracle they had a copy on the shelf. They also had a great event a few summers back in the backyard, where they screened Godard’s A Married Woman, with New Yorker writer Richard Brody.”

— Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Publicity Manager

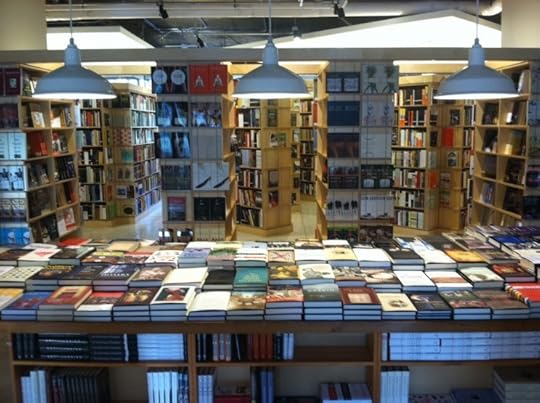

Seminary Co-op Bookstore, courtesy of Alana Podolsky. Used with permission.

Seminary Co-op Bookstore, courtesy of Alana Podolsky. Used with permission. * * *

“There are few things better than stepping off a Chicago street, unraveling the many layers of clothing required for -10°F weather and stepping into the warmth of the Seminary Co-Op. It’s easy to start gushing about the Sem Co-Op’s maze of books, where you can hide in a corner for hours reading store’s eclectic, charming and comprehensive collection.”

— Alana Podolsky, Assistant Marketing Manager for History, Academic and Trade Marketing

* * *

“I’ve been in the book business for over 30 years, starting as a part-time bookseller at Atticus Books in Richmond, VA to my current job working with indie stores nationwide. Throughout this time, I’ve had the pleasure of visiting some of the largest independent stores to the smallest specialty stores across the country, each with its own charm and treasures. Indie bookstores offer a chance to discover new authors, a connection to the local community, and a wonderful antidote to the “sameness” that pervades much shopping today.”

— Richard Fugini, Field Sales Manager

* * *

“One of my favorite places in the world is Von’s Books in West Lafayette, Indiana, near the campus of Purdue University. It is jammed with great books – so many that they overflow onto stacks on the floor between shelves – and there is reliably a familiar face from my undergraduate days behind the front desk when I go back for visits. (Von’s is also very conveniently located down the block from Harry’s Chocolate Shop, another Purdue institution.)”

— Kandice Rawlings, Associate Editor, Reference

* * *

“While visiting Seattle media in the winter/spring of 2014 my sales rep for the great northwest, George Carroll, took me around to some of his account (indie stores) in town. My favorite store was Ada’s Technical Books on 15th Ave. East in Seattle. It was a small intimate store with interesting lab equipment and technical gadgets displayed throughout the space. I remember walls lined with books about science, engineering, mathematics and technology, of course. And a few tables made out of shadowboxes in a café space, and a small backroom for events. The store has reclaimed and repurposed a lot of its decor from whatever had been in the space before it became a bookstore. Most memorable, however, was the congeniality of the staff. George and I had arrived just after they had closed, but they opened their door to me so I could browse the space for possible future events for OUP authors coming through Seattle. They never rushed me or complained, instead they halted their closing ritual and chatted amiably with me about books, publishing, bookselling, and the vibe they were trying to create at Ada’s and the neighborhood that surrounded them. The whole experience was rare and extraordinary. They will have a lifetime fan in me for their graciousness.”

— Purdy, Director of Publicity

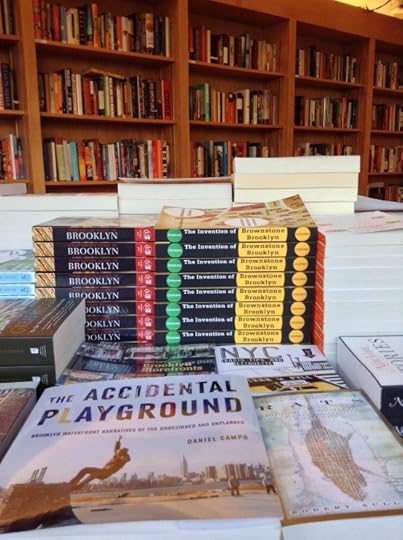

Greenlight Bookstore, Brooklyn. Courtesy of Margaret Williams. Used with permission.

Greenlight Bookstore, Brooklyn. Courtesy of Margaret Williams. Used with permission. * * *

“The community has really taken to Greenlight Bookstore in Fort Greene, as they offer a great selection of books and they have held numerous readings and book signings of local Brooklyn authors/artists. I’ve purchased a few books on reggae and cookbooks. The staff there is super friendly and they have a well-curated inventory of books on lots of subjects. It’s been great for the neighborhood.”

— Alan Goldberg, Demand Planner, GAB Operations

* * *

“Litchfield Books in Pawley’s Island, SC, has been a magical place for my family and me ever since we started vacationing on the SC coast 20 years ago. I don’t think any of us have ever left there without a half-dozen titles! Everyone who works there is so knowledgeable and kind, and you feel their love for books just as soon as you walk in the door. I can’t recommend it enough, especially if you are ever at a completely loss for a new book—they are bound to point you in the right direction!”

— Sarah Pirovitz, Associate Editor, Classics, Ancient Art, and Archaeology

* * *

“My favorite indie bookstore is Quail Ridge Books located in Raleigh, North Carolina. I started visiting Quail Ridge as an undergraduate at North Carolina State University located just down the street. I love this store mostly for their selection (I especially love their section on regional books) and also for their helpful and courteous staff. There is truly something to be said about Southern hospitality…it is definitely present at Quail Ridge.”

— Victoria Ohegyi , Sales Assistant

* * *

“Cobble Hill’s Book Court has been my dealer ever since I moved to Brooklyn seven years ago. They have a great selection, amazing author events, and if they don’t have it on the shelf, they’re happy to order it. As a new parent, I get to share their kids section with my one–year old, who already loves books and story time. We love to wander among the shelves and find new books to read. The neighborhood has gone through tremendous changes since Book Court first opened and it’s great to see that this indie book store is a true foundation of and for the community.”

— Burke Gerstenschlager, Acquisitions Editor

Readings, Carlton by Snipergirl. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Readings, Carlton by Snipergirl. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. * * *

“Readings in Carlton, Melbourne, Australia is my favorite independent bookstore. I discovered it while studying abroad at the University of Melbourne when I was in college. The staff is so helpful and the store’s location on Lygon Street is perfect for grabbing a cup of coffee and spending an afternoon browsing through their great selection of books and cards.”

— Ciara O’Connor, Marketing Assistant

* * *

“My favorite bookstore is and will always be Rakestraw Books, in the heart of my hometown in Danville, CA. They’ve been around since 1973 and have hosted events with a diverse and often eclectic range of authors over the years, making the store a favorite destination for both me and my mom. I still remember roaming the stacks as a kid, painfully deliberating between dozens of books before finally selecting on ‘just one’ book to bring to the check out. Even just thinking about Rakestraw Books still brings a nostalgic smile to my face.

“I also have a huge soft spot for Bookworks, a literary wonderland in my parents’ hometown of Albuquerque, NM. One of my most treasured Christmas gifts was a beautifully illustrated copy of the first Harry Potter book in Italian, Harry Potter e la Pietra Filosofale, which I received from my grandpa the year after I started learning Italian in college. Apparently, my grandpa and the Bookwords owners had teamed up to locate a copy and ship it over all the way from Italy — now THAT’s a dedicated staff!”

— Carrie Napolitano, Marketing Associate for Linguistics, Religion & Bibles

* * *

“One bookstore that really caught my eye is WORD Bookstore in Jersey City. It’s really a lovely place to go because there’s a coffee bar in the back, and they regularly host book group meetings, music shows, and a bunch of other types of events in addition to the typical author appearance and book signings. They also stock a lot of neat stationery, which (unfortunately for my wallet) happens to be one of my weaknesses…”

— Connie Ngo, Marketing Assistant

* * *

Heading image: A cubbyhole with education/sociology books, Seminary Co-op Bookstore, Chicago, IL, by Connie Ma. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post OUP staff discuss their favorite independent bookstores appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Q&A with a Keytar playerThanks, teacher: musicians reflect on special ways a teacher helped them learn their craftSlavery, rooted in America’s early history

Related StoriesA Q&A with a Keytar playerThanks, teacher: musicians reflect on special ways a teacher helped them learn their craftSlavery, rooted in America’s early history

A Q&A with a Keytar player

I sat down with V.J. Manzo, author of Max/MSP/Jitter for Music: A Practical Guide to Developing Interactive Music Systems for Education and More, and real-live Keytar player, to get the inside scoop on one of the coolest, retro electronic instruments on stage — the Keytar.

When and why did you decide to start playing Keytar?

I’ve been playing keytar for a little over 5 years now. I play in a group where it is necessary to use multiple keyboards at once. I wanted to play an instrument that allowed me to move around freely on the stage, instead of always being tethered to the keyboard on a stand that is stuck in one location. The keytar, in particular the vintage Roland AX-7, looked retro and quirky, so I decided to use it because it made the parts I perform on it a little bit more fun and noticeable for the audience.

What exactly is a Keytar, and what makes it different from the keyboard?

A keytar is a synthesizer instrument just like a keyboard synthesizer on a traditional stand, but it is tied to a strap and worn like a guitar. It’s played mostly for live or stage performances. It differs from a keyboard on a stand in that it has a smaller range of keys, and can be worn. Because of the way it’s held, it’s probably best used for one-handed solos, rather than 2-handed playing that is more common with the keyboard on a stand. Unlike a piano, the keytar sends computer messages using a protocol called MIDI, that say “I played this note, this hard.” Then the software receives the information from the instrument and synthesizes the note with different sounds. For this reason, a keyboard or keytar can sound like anything: a piano, a guitar, a bagpipe—anything, really!

V.J. Manzo playing Keytar. Image used with permission

V.J. Manzo playing Keytar. Image used with permission What was the first song you learned to play on Keytar?

The first song I learned on keytar was “Separate Ways” by Journey. It had a really nice melody that I thought would stand out and be able to catch the audience’s attention. I remember thinking, “That main melody is really memorable, and iconic. It’s nice to get to play an instrument that really shows the audience where on the stage that melody is coming from, and in such a fun and surprising way.”

Do you remember your first Keytar performance? What was running through your head?

Yes! I remember thinking, “WOW! This instrument takes a little bit of getting used to after playing keyboard. How do I hold this thing and play with good technique?! Oh, I can’t?— Oh well, at least it looks cool!”

What do you enjoy most about playing Keytar?

I really enjoy being able to move around on stage, and having the ability to really interact and engage with the audience. That flexibility is something keyboard players don’t really get with the stand. It’s lot of fun too — and I usually get good responses from the audience.

Are there any notable Keytar players that you like?

Lots of players have used and currently use a keytar! Jordan Rudess from Dream Theater, Herbie Hancock, and Stevie Wonder all shred on Keytar! They were popular in the 80’s, but have recently become popular again with the introduction of new technologies into the new Roland models. It takes a certain amount of confidence for a keytarist to be ok with the stigma having “guitar-envy”!

What is your favorite song to play on the Keytar?

My favorite song to play on the keytar is “Tom Sawyer” by Rush. The keyboard lick in the middle is iconic, and with a keytar, the audience can actually see the notes I’m playing. The musical figure itself works out nicely to be played with one hand, which is ideal for the keytar!

V.J. Manzo playing keytar:

Headline image credit: Korg RK-100 (1984) MIDI remote controller. CC-BY-2.0 via WikiCommons

The post A Q&A with a Keytar player appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThanks, teacher: musicians reflect on special ways a teacher helped them learn their craftThank you: musicians recall special ways their parents helped them blossomAMS/SMT 2014: Highlights from the OUP booth

Related StoriesThanks, teacher: musicians reflect on special ways a teacher helped them learn their craftThank you: musicians recall special ways their parents helped them blossomAMS/SMT 2014: Highlights from the OUP booth

November 28, 2014

Thanks, teacher: musicians reflect on special ways a teacher helped them learn their craft

“I was lucky all the time in having great teachers,” says clarinetist Richard Stoltzman. When I asked him about special ways his early teachers helped him, he mentioned his elementary school band director who was “enthusiastic and cheerful, no matter what,” and also a private teacher he had in high school who taught him how to practice with purpose. But the teacher who seems to have had a life-changing impact was his first private teacher, with whom he studied for about a year during junior high at a music store in San Francisco. That teacher instilled in young Mr. Stoltzman the idea that he could indeed become a musician.

Other musicians have cited similar confidence boosters when asked about the especially helpful things a teacher did for them. Here are teacher reminiscences from Mr. Stoltzman and other professional musicians.

Richard Stoltzman — “He taught me both saxophone and clarinet,” says Mr. Stoltzman of his first private teacher at that San Francisco music store. “He didn’t see any reason why I couldn’t play classical music and improvised music.” At this store, young Mr. Stoltzman played his first “crossover recital,” performing Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust” as well as a classical piece. “This was a big moment for me, that my teacher allowed me to do those things and encouraged them.” Then the Stoltzmans moved to Ohio. “I was so sad to leave that teacher. At my last lesson, he looked me in the eye and said something like, ‘You can do it. You can play music. Don’t stop.’ If somebody believes in you, that makes you say to yourself, ‘Well, this person believes in me. So even if I don’t think I can do it, I guess somehow I better keep doing it.’”

Isabel Trautwein — “My confidence was very low at the end of my undergraduate years. I was close to quitting because I was so uptight and just couldn’t stop worrying that I might play out of tune,” says Isabel Trautwein, violinist with the Cleveland Orchestra. “Then I went to Cleveland to study with Donald Weilerstein. He used the ultimate non-judgmental approach. He never used criticism. He would go through a piece line by line and wanted to know what I was trying to say, as a person. He would say, ‘In this phrase, where are you going?’ My eyes would open wide. I would think, ‘I don’t know. I’m just trying to play it in tune. I’m trying to play it well.’ But that’s a terrible goal. So he would say, ‘OK, but do you want it to be gutsy? Or dark? Are you going for the gypsy approach? Are you going for fantasy? ’ He had all these great words. He’d also say specific things like, ‘Feel your index finger when you play.’ It was a mixture of musical cues that have to do with the character and musical feel, and then physical cues that had the ability to take your mind away from that voice that says, ‘Oh, that wasn’t good,’ the critical voice. If I’m thinking about my fingertips, I’m not going to be able to judge myself on what just went wrong. Weilerstein’s lessons were only about the violin. Never psychoanalytical. It helped a lot.”

Paula Robison teaching at New England Conservatory. Courtesy, New England Conservatory and Andrew Hurlbut.

Paula Robison teaching at New England Conservatory. Courtesy, New England Conservatory and Andrew Hurlbut.Paula Robison — “I had been studying with Marcel Moyse for about five years, and was already in the professional world of music as well as the artistic one, but I still had many questions,” says flutist Paula Robison, who studied with this renowned teacher at the Marlboro Music School. “One day I came to a lesson with the Concerto in D of Mozart. I played the first movement. Mr. Moyse was silent. He puffed on his pipe, in deep thought. Minutes passed. I waited. Then he slowly said (in his wonderful French accent) ‘Paula, I have teach you many theeng, but now you MUST GO YOUR OWN WAY.’ I was shocked. I felt like a bird kicked out of the nest. But he was right. It was time for me to fly. And I did.”

Anne Akiko Meyers — “I am so thankful to all my teachers for their tireless commitment and dedication, but the one lesson that stands out was the lesson I learned from the great Dorothy DeLay,” says violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, who studied with Ms. DeLay at Juilliard. “She told me to go to the library and listen to all the recordings I could get my hands on and attend concerts as much as possible, to listen and learn as much as possible. She thought it would be incredibly helpful to study the phrasing, tempi, sound, and technique of all performers so that I could imbue my own sound with this insightful study and thoughtfulness. This purpose of being able to teach oneself with the right tools, so as to ‘own’ your sound, was the greatest lesson of all.”

Jennifer Undercofler — “I’m probably most grateful to my first piano teacher, a graduate of the Paris Conservatoire, who was deeply creative, with a wonderful, wry sense of humor. She always expected more out of me than I thought I could give. I remember her assigning me an Ives etude (I must have been 10 or 11 years old), declaring that she hated it, but knew that I would probably love it. She proceeded to break it down with me over the coming weeks, with considerable gusto. She was right, of course—I did love it. I don’t know many teachers, even now, who would have taken that particular plunge with an elementary school student,” says pianist and music educator Jenny Undercofler, whose fascination with ‘new music’ has continued ever since. “In a similar vein, I remember Jerry Lowenthal calling me when I was a masters student at Juilliard, to tell me to make time to play ‘new music’ on the Focus Festival. I was so surprised and flattered by the call, and of course I then played in the festival, which further opened the ‘new music’ door. I think of this when I encourage private teachers to have their students play with Face the Music. Their ‘endorsement’ can make a world of difference.” Face the Music is a ‘new music’ ensemble for teenagers that she started as an outgrowth of her work as music director of the Special Music School, a New York City public school.

Toyin Spellman-Diaz — “The impetus for my interest in music came from my first public school music teacher in fifth grade,” says the Imani Winds oboist, Toyin Spellman-Diaz. “She inspired in me a love of seeing a project come to fruition. She put on musical productions. She would play the piano, rehearse the choir, have kids get costumes. She had crazy ideas and somehow made them come to life and did it with determination and joy. I remember watching her as a young child and thinking that even though it was a lot of work, she enjoyed what she was doing. I remember thinking, ‘I would really like to do something like this when I grow up.’ I sang in the choir. She introduced me to the flute and I played in the school band. I wanted to follow in her footsteps and be a music teacher,” says Ms. Spellman-Diaz, who has a studio of pupils now. She also serves as another kind of teacher during Imani Winds concerts, with the informative comments that she and others in the quintet share with the audience before each piece.

Headline Image: Sheet Music, Piano. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Thanks, teacher: musicians reflect on special ways a teacher helped them learn their craft appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThank you: musicians recall special ways their parents helped them blossomThe history of the newspaperA look at Thanksgiving favorites

Related StoriesThank you: musicians recall special ways their parents helped them blossomThe history of the newspaperA look at Thanksgiving favorites

What we’re thankful for

Since we’re still recovering from eating way too much yesterday, Managing Editor Troy Reeves and I would like to sit back and just share a few of the things we’re thankful for.

Troy Reeves:

Wow! So many things I’m thankful for, such as family, friends, pie, turkey, cranberries (basically just about every food associated with Thanksgiving). Except the marshmallows on top the yams – don’t get it, don’t like it.

Oh, right, this post should focus on the oral history-related thankful things. Well, it still comes back to friendship. I have been blessed over my now 15 years in the Oral History Association in building a cadre (cabal?) of colleagues who double as friends. And I leaned on these people early on to help us build our presence on OUPblog.

From our first post (thanks Sarah) through our longest podcast (thanks Doug) and several in-between (looking at you Steinhauer – for both posts – Wettemann, Morse and Corrigan, and Cramer), I feel like Joe Cocker (or Ringo Starr): I “get by with a little help from my friends.” (And I did not mention the law firm of Larson, Moye, and Sloan who helped us tease the 2013 OHA Conference.)

Last but not least, I’m thankful and grateful for the social media work of Caitlin Tyler-Richards. Even though I have full faith in Andrew, your presence will be missed. But I can always return to your last post, when I need my Caitlin fix.

So, there you go. And in case you are wondering: Yes, I turned my part of this into a homage to the Simpson’s cheesy-clip show.

Andrew Shaffer:

As a recent addition to the Oral History Review team, and a recent transplant to Wisconsin, there are a ton of things I’m thankful for.

First, I have to echo Troy in being thankful for Caitlin. She’s been immensely helpful in teaching me the social media ropes. #StillNotSureHowToHashtagProperlyThough

I’d like to name my favorite OHR blog posts, but there are just too many to list. I’m especially thankful, though, for people who are finding innovative ways to fund, record, and think deeply about oral history. It’s a privilege to be part of such an exciting field.

Thanksgiving feast, by StarMama. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Thanksgiving feast, by StarMama. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.I met some amazing oral historians at the recent Oral History Association Annual Meeting, and I’m very grateful to all the people who helped to put on such a great conference.

I’m thankful to Troy for giving me a second interview, even after I showed up two hours late to the first one. Protip: When moving from the West Coast to the Midwest, make sure you update your calendar to the correct time zone.

And lastly, I should mention that I’m very thankful for my friends and family, even though most haven’t heard from me in a while!

———————-

Finally, after the recent polar vortex hitting us in Wisconsin, Troy and I are both very happy that next year’s OHA Annual Meeting will be in sunny Florida. Check out the Call For Papers here – we look forward to seeing you there!

We’ll be back with another blog post soon, but in the mean time, visit us on Twitter, Facebook, or Google+ to tell us what you’re thankful for.

Happy Thanksgiving everyone!

The post What we’re thankful for appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAcademics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. PickronRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingThe power of oral history as a history-making practice

Related StoriesAcademics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. PickronRecap of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingThe power of oral history as a history-making practice

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers