Oxford University Press's Blog, page 771

August 22, 2014

An Oxford Companion to being the Doctor

If you share my jealousy of Peter Capaldi and his new guise as the Doctor, then read on to discover how you could become the next Time Lord with a fondness for Earth. However, be warned: you can’t just pick up Matt Smith’s bow-tie from the floor, don Tom Baker’s scarf, and expect to save planet Earth every Saturday at peak viewing time. You’re going to need training. This is where Oxford’s online products can help you. Think of us as your very own Companion guiding you through the dimensions of time, only with a bit more sass. So jump aboard (yes it’s bigger on the inside), press that button over there, pull that lever thingy, and let’s journey through the five things you need to know to become the Doctor.

(1) Regeneration

Being called two-faced may not initially appeal to you. How about twelve-faced? No wait, don’t leave, come back! Part of the appeal of the Doctor is his ability to regenerate and assume many faces. Perhaps the most striking example of regeneration we have on our planet is the Hydra fish which is able to completely re-grow a severed head. Even more striking is its ability to grow more than one head if a small incision is made on its body. I don’t think it’s likely the BBC will commission a Doctor with two heads though so best to not go down that route. Another example of an animal capable of regeneration is Porifera, the sponges commonly seen on rocks under water. These sponge-type creatures are able to regenerate an entire limb which is certainly impressive but are not quite as attractive as The David Tenants or Matt Smiths of this world.

Sea sponges, by Dimitris Siskopoulos. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Sea sponges, by Dimitris Siskopoulos. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.(2) Fighting aliens

Although alien invasion narratives only crossed over to mainstream fiction after World War II, the Doctor has been fighting off alien invasions since the Dalek War and the subsequent destruction of Gallifrey. Alien invasion narratives are tied together by one salient issue: conquer or be conquered. Whether you are battling Weeping Angels or Cybermen, you must first make sure what you are battling is indeed an alien. Yes, that lady you meet every day at the bus-stop with the strange smell may appear to be from another dimension but it’s always better to be sure before you whip out your sonic screwdriver.

(3) Visiting unknown galaxies

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field telescope captures a patch of sky that represents one thirteen-millionth of the area of the whole sky we see from Earth, and this tiny patch of the Universe contains over 10,000 galaxies. One thirteen-millionth of the sky is the equivalent to holding a grain of sand at arm’s length whilst looking up at the sky. When we look at a galaxy ten billion light years away, we are actually only seeing it by the light that left it ten billion years ago. Therefore, telescopes are akin to time machines.

The sheer vastness and mystery of the universe has baffled us for centuries. Doctor Who acts as a gatekeeper to the unknown, helping us imagine fantastical creatures such as the Daleks, all from the comfort of our living rooms.

Tardis, © davidmartyn, via iStock Photo.

Tardis, © davidmartyn, via iStock Photo.(4) Operating the T.A.R.D.I.S.

The majority of time-travel narratives avoid the use of a physical time-machine. However, the Tardis, a blue police telephone box, journeys through time dimensions and is as important to the plot of Doctor Who as upgrades are to Cybermen. Although it looks like a plain old police telephone box, it has been known to withstand meteorite bombardment, shield itself from laser gun fire and traverse the time vortex all in one episode. The Tardis’s most striking characteristic, that it is “much bigger on the inside”, is explained by the Fourth Doctor, Tom Baker, by using the analogy of the tesseract.

(5) Looking good

It’s all very well saving the Universe every week but what use is that without a signature look? Tom Baker had the scarf, Peter Davison had the pin-stripes, John Hurt even had the brooding frown, so what will your dress-sense say about you? Perhaps you could be the Doctor with a cravat or the time-traveller with a toupee? Whatever your choice, I’m sure you’ll pull it off, you handsome devil you.

Don’t forget a good sense of humour to compliment your dashing visage. When Doctor Who was created by Donald Wilson and C.E. Webber in November 1963, the target audience of the show was eight-to-thirteen-year-olds watching as part of a family group on Saturday afternoons. In 2014, it has a worldwide general audience of all ages, claiming over 77 million viewers in the UK, Australia, and the United States. This is largely due to the Doctor’s quick quips and mix of adult and childish humour.

You’ve done it! You’ve conquered the cybermen, exterminated the daleks, and saved Earth (we’re eternally grateful of course). Why not take the Tardis for another spin and adventure through more of Oxford’s online products?

Image credit: Doctor Who poster, by Doctor Who Spoilers. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post An Oxford Companion to being the Doctor appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarRadiology and Egyptology: insights from ancient lives at the British MuseumThe biggest threat to the world is still ourselves

Related StoriesThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarRadiology and Egyptology: insights from ancient lives at the British MuseumThe biggest threat to the world is still ourselves

Radiology and Egyptology: insights from ancient lives at the British Museum

Egyptian mummies continue to fascinate us due to the remarkable insights they provide into ancient civilizations. Flinders Petrie, the first UK chair in Egyptology did not have the luxury of X-ray techniques in his era of archaeological analysis in the late nineteenth century. However, twentieth century Egyptologists have benefited from Roentgen’s legacy. Sir Graham Elliott Smith along with Howard Carter did early work on plain x-ray analysis of mummies when they X-rayed the mummy Tuthmosis in 1904. Numerous X-ray analyses were performed using portable X-ray equipment on mummies in the Cairo Museum.

Since then, many studies have been done worldwide, especially with the development of more sophisticated imaging techniques such as CT scanning, invented by Hounsfield in the UK in the 1970s. With this, it became easier to visualize the interiors of mummies, thus revealing their hidden mysteries under their linen wrapped bodies and the elaborate face masks which had perplexed researchers for centuries. Harwood Nash performed one of the earliest head scans of a mummy in Canada in 1977 and Isherwood’s team along with Professor David also performed some of the earliest scannings of mummies in Manchester.

Tori Randall, PhD prepares a 550-year old Peruvian child mummy for a CT scan, by Samantha A. Lewis for the US Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Tori Randall, PhD prepares a 550-year old Peruvian child mummy for a CT scan, by Samantha A. Lewis for the US Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.A fascinating new summer exhibition at the British Museum has recently opened, and consists of eight mummies, all from different periods and Egyptian dynasties, that have been studied with the latest dual energy CT scanners. These scanners have 3D volumetric image acquisitions that reveal the internal secrets of these mummies. Mummies of babies and young children are included, as well as adults. There have been some interesting discoveries already, for example, that dental abscesses were prevalent as well as calcified plaques in peripheral arteries, suggesting vascular disease was present in the population who lived over 3,000 years ago. More detailed analysis of bones, including the pelvis, has been made possible by the scanned images, enabling more accurate estimation of the age of death.

Although embalmers took their craft seriously, mistakes did occur, as evidenced by one of the mummy exhibits, which shows Padiamenet’s head detached from the body during the process, the head was subsequently stabilized by metal rods. Padiamenet was a temple doorkeeper who died around 700BC. Mummies had their brains removed with the heart preserved as this was considered the seat of the soul. Internal organs such as the stomach and liver were often removed; bodies were also buried with a range of amulets.

The exhibit provides a fascinating introduction to mummies and early Egyptian life more than 3,000 years ago and includes new insights gleaned from cutting edge twenty first century imaging technology.

Ancient Lives: New Discoveries is on at the British Museum until the 30 November 2014.

Heading image: Mummy. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Radiology and Egyptology: insights from ancient lives at the British Museum appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarThe 150th anniversary of Newlands’ discovery of the periodic systemDmitri Mendeleev’s lost elements

Related StoriesThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarThe 150th anniversary of Newlands’ discovery of the periodic systemDmitri Mendeleev’s lost elements

The biggest threat to the world is still ourselves

At a time when the press and broadcast media are overwhelmed by accounts and images of humankind’s violence and stupidity, the fact that our race survives purely as a consequence of Nature’s consent, may seem irrelevant. Indeed, if we think about this at all, it might be to conclude that our world would likely be a nicer place all round, should a geophysical cull in some form or other, consign humanity to evolution’s dustbin, along with the dinosaurs and countless other life forms that are no longer with us. While toying with such a drastic action, however, we should be careful what we wish for, even during these difficult times when it is easy to question whether our race deserves to persist. This is partly because alongside its sometimes unimaginable cruelty, humankind also has an enormous capacity for good, but mainly because Nature could – at this very moment – be cooking up something nasty that, if it doesn’t wipe us all out, will certainly give us a very unpleasant shock.

After all, nature’s shock troops are still out there. Economy-busting megaquakes are biding their time beneath Tokyo and Los Angeles; volcanoes are swelling to bursting point across the globe; and killer asteroids are searching for a likely planet upon which to end their lives in spectacular fashion. Meanwhile, climate change grinds on remorselessly, spawning biblical floods, increasingly powerful storms, and baking heatwave and drought conditions. Nonetheless, it often seems – in our security obsessed. tech-driven society – as if the only horrors we are likely to face in the future are manufactured by us; nuclear terrorism; the march of the robots; out of control nanotechnology; high-energy physics experiments gone wrong. It is almost as if the future is nature-free; wholly and completely within humankind’s thrall. The truth is, however, that these are all threats that don’t and shouldn’t materialise, in the sense that whether or not we allow their realisation is entirely within our hands.

The same does not apply, however, to the worst that nature can throw at us. We can’t predict earthquakes and may never be able to, and there is nothing at all we can do if we spot a 10-km diameter comet heading our way. As for encouraging an impending super-eruption to ‘let of steam’ by drilling a borehole, this would – as I have said before – have the same effect as sticking a drawing pin in an elephant’s bum; none at all.

San Francisco after 1906 earthquake. National Archives, College Park. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

San Francisco after 1906 earthquake. National Archives, College Park. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The bottom line is that while the human race may find itself, at some point in the future, in dire straits as a consequence of its own arrogance, aggression, or plain stupidity, this is by no means guaranteed. On the contrary, we can be 100 percent certain that at some point we will need to face the awful consequences of an exploding super-volcano or a chunk of rock barreling into our world that our telescopes have missed. Just because such events are very rare does not mean that we should not start thinking now about how we might prepare and cope with the aftermath. It does seem, however, that while it is OK to speculate at length upon the theoretical threat presented by robots and artificial intelligence, the global economic impact of the imminent quake beneath Tokyo, to cite one example of forthcoming catastrophe, is regarded as small beer.

Our apparent obsession with technological threats is also doing no favours in relation to how we view the coming climate cataclysm. While underpinned by humankind’s polluting activities, nature’s disruptive and detrimental response is driven largely by the atmosphere and the oceans, through increasingly wild weather, remorselessly-rising temperatures and climbing sea levels. With no sign of greenhouse gas emissions reducing and concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere crossing the emblematic 400 parts per million mark in 2013, there seems little chance now of avoiding a 2°C global average temperature rise that will bring dangerous, all-pervasive climate change to us all.

Sakurajima, by kimon Berlin. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Sakurajima, by kimon Berlin. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The hope is that we come to our collective senses and stop things getting much worse. But what if we don’t? A paper published last year in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and written by lauded NASA climate scientist, James Hansen and colleagues, provides a terrifying picture of what out world will be be like if we burn all available fossil fuels. The global average temperature, which is currently a little under 15°C will more than double to around 30°C, transforming most of our planet into a wasteland too hot for humans to inhabit. If not an extinction level event as such, there would likely be few of us left to scrabble some sort of existence in this hothouse hell.

So, by all means carry on worrying about what happens if terrorists get hold of ‘the bomb’ or if robots turn on their masters, but always be aware that the only future global threats we can be certain of are those in nature’s armoury. Most of all, consider the fact that in relation to climate change, the greatest danger our world has ever faced, it is not terrorists or robots – or even experimental physicists – that are to blame, but ultimately, every one of us.

The post The biggest threat to the world is still ourselves appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPractical wisdom and why we need to value itBiting, whipping, tickling1914: The opening campaigns

Related StoriesPractical wisdom and why we need to value itBiting, whipping, tickling1914: The opening campaigns

August 21, 2014

Early Modern Porn Wars

One day in 1668, the English diarist Samuel Pepys went shopping for a book to give his young French-speaking wife. He saw a book he thought she might enjoy, L’École des femmes or The School of Women, “but when I came to look into it, it is the most bawdy, lewd book that ever I saw,” he wrote, “so that I was ashamed of reading in it.” Not so ashamed, however, that he didn’t return to buy it for himself three weeks later — but “in plain binding…because I resolve, as soon as I have read it, to burn it, that it may not stand in the list of books, nor among them, to disgrace them if it should be found.” The next night he stole off to his room to read it, judging it to be “a lewd book, but what doth me no wrong to read for information sake (but it did hazer my prick para stand all the while, and una vez to decharger); and after I had done it, I burned it, that it might not be among my books to my shame.” Pepys’s coy detours into mock-Spanish or Franglais fail to conceal the orgasmic effect the lewd book had on him, and his is the earliest and most candid report we have of one reader’s bodily response to the reading of pornography. But what is “pornography”? What is its history? Was there even such a thing as “pornography” before the word was coined in the nineteenth century?

The announcement, in early 2013, of the establishment of a new academic journal to be called Porn Studies led to a minor flurry of media reports and set off, predictably, responses ranging from interest to outrage by way of derision. One group, self-titled Stop Porn Culture, circulated a petition denouncing the project, echoing the “porn wars” of the 1970s and 80s which pitted anti-censorship against anti-pornography activists. Those years saw an eruption of heated, if not always illuminating, debate over the meanings and effects of sexual representations; and if the anti-censorship side may seem to have “won” the war, in that sexual representations seem to be inescapable in the age of the internet and social media, the anti-pornography credo that such representations cause cultural, psychological, and physical harm is now so widespread as almost to be taken for granted in the mainstream press.

The brave new world of “sexting” and content-sharing apps may have fueled anxieties about the apparent sexualization of popular culture, and especially of young people, but these anxieties are anything but new; they may, in fact, be as old as culture itself. At the very least, they go back to a period when new print technologies and rising literacy rates first put sexual representations within reach of a wide popular audience in England and elsewhere in Western Europe: the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Most readers did not leave diaries, but Pepys was probably typical in the mixture of shame and excitement he felt when erotic works like L’École des femmes began to appear in London bookshops from the 1680s on. Yet as long as such works could only be found in the original French or Italian, British censors took little interest in them, for their readership was limited to a linguistic elite. It was only when translation made such texts available to less privileged readers — women, tradesmen, apprentices, servants — that the agents of the law came to view them as a threat to what the Attorney General, Sir Philip Yorke, in an important 1728 obscenity trial, called the “public order which is morality.” The pornographic or obscene work is one whose sexual representations violate cultural taboos and norms of decency. In doing so it may lend itself to social and political critique, as happened in France in the 1780s and 90s, when obscene texts were used to critique the corruptions of the ancien régime; but the pornographic can also be used as a vehicle of debasement and violence, notably against women — which is one historical reality behind the US porn wars of the 1970s.

Front page of L’École des femmes—engraving from the 1719 edition. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Front page of L’École des femmes—engraving from the 1719 edition. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Pornography’s critics in the late twentieth or early twenty-first centuries have had less interest in the written word than in visual media; but recurrent campaigns to ban books by such authors as Judy Blume which aim to engage candidly with younger readers on sexual concerns suggest that literature can still be a battleground, as it was in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Take, for example, the words of the British attorney general Dudley Ryder in the 1749 obscenity trial of Thomas Cannon’s Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplify’d, a paean to male same-sex desire masquerading as an attack. Cannon, Ryder declared, aimed to “Debauch Poison and Infect the Minds of all the Youth of this Kingdom and to Raise Excite and Create in the Minds of all the said Youth most Shocking and Abominable Ideas and Sentiments”; and in so doing, Ryder contends, Cannon aimed to draw readers “into the Love and Practice of that unnatural detestable and odious crime of Sodomy.” Two and a half centuries ago, Ryder set the terms of our ongoing porn wars. Denouncing the recent profusion of sexual representations, he insists that such works create dangerous new desires and inspire their readers to commit sexual crimes of their own.

Then as now, attitudes towards sexuality and sexual representations were almost unbridgeably polarized. A surge in the popularity of pornographic texts was countered by increasingly severe campaigns to suppress them. Ironically, however, those very attempts to suppress could actually bring the offending work to a wider audience, by exciting their curiosity. No copies of Cannon’s “shocking and abominable” work survive in their original form; but the text has been preserved for us to read in the indictment that Ryder prepared for the trial against it. Eighty years earlier, after his encounter with L’École des femmes, Pepys guiltily burned the book, but at the same time immortalized the sensual, shameful experience of reading it. Of such contradictions is the long history of porn wars made.

The post Early Modern Porn Wars appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonsters in the library: Karl August Eckhardt and Felix LiebermannThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarGetting to know Anna-Lise Santella, Editor of Grove Music Online

Related StoriesMonsters in the library: Karl August Eckhardt and Felix LiebermannThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarGetting to know Anna-Lise Santella, Editor of Grove Music Online

Getting to know Anna-Lise Santella, Editor of Grove Music Online

Meet the woman behind Grove Music Online, Anna-Lise Santella. We snagged a bit of Anna-Lise’s time to sit down with her and find out more about her own musical passions and research.

Do you play any musical instruments? Which ones?

My main instrument is violin, which I’ve played since I was eight. I play both classical and Irish fiddle and am currently trying to learn bluegrass. In a previous life I played a lot of pit band for musical theater. I’ve also worked as a singer and choral conductor. These days, though, you’re more likely to find a mandolin or guitar in my hands.

Do you specialize in any particular area or genre of music?

My research interests are pretty broad, which is why I enjoy working in reference so much. Currently I’m working on a history of women’s symphony orchestras in the United States between 1871 and 1945. They were a key route for women seeking admission into formerly all-male orchestras like the Chicago Symphony. After that, I’m hoping to work on a history of the Three Arts Clubs, a network of residential clubs that housed women artists in cities in the US and abroad. The clubs allowed female performers to safely tour or study away from their families by giving them secure places to live while on the road, places to rehearse and practice, and a community of like-minded people to support them. In general, I’m interested in the ways public institutions have affected and responded to women as performers.

What artist do you have on repeat at the moment?

I tend to have my listening on shuffle. I like not being sure what’s coming next. That said, I’ve been listening to Tune-Yards’ (a.k.a. Merill Garbus) latest album an awful lot lately. Neko Case with the New Pornographers and guitarist/songwriter/storyteller extraordinaire Jim White are also in regular rotation.

What was the last concert/gig you went to?

I’m lucky to live not far from the bandshell in Prospect Park and I try to catch as many of the summer concerts there as I can. The last one I attended was Neutral Milk Hotel, although I didn’t stay for the whole thing. I’m looking forward to the upcoming Nickel Creek concert. I love watching Chris Thile play, although he makes me feel totally inadequate as a mandolinist.

How do you listen to most of the music you listen to? On your phone/mp3 player/computer/radio/car radio/CDs?

Mostly on headphones. I’m constantly plugged in, which makes me not a very good citizen, I think. I’m trying to get better about spending some time just listening to the city. But there’s something about the delivery system of headphones to ears that I like – music transmitted straight to your head makes you feel like your life has a soundtrack. I especially like listening on the subway. I’ll often be playing pieces I’m trying to learn on violin or guitar and trying to work out fingerings, which I’m pretty sure makes me look like an insane person. Fortunately insane people are a dime a dozen on the subway.

Do you find that listening to music helps you concentrate while you work, or do you prefer silence?

I like listening while I work, but it has to be music I find fairly innocuous, or I’ll start thinking about it and analyzing it and get distracted from what I’m trying to do. Something beat driven with no vocals is best. My usual office soundtrack is a Pandora station of EDM.

Detail of violin being played by a musician. © bizoo_n via iStockphoto.

Detail of violin being played by a musician. © bizoo_n via iStockphoto.Has there been any recent music research or scholarship on a topic that has caught your eye or that you’ve found particularly innovative?

In general I’m attracted to interdisciplinary work, as I like what happens when ideologies from one field get applied to subject matter of another – it tends make you reevaluate your methods, to shake you out of the routine of your thinking. Right now I’ve become really interested in the way in which we categorize music vs. noise and am reading everything I can on the subject from all kinds of perspectives – music cognition, acoustics, cultural theory. It’s where neuroscience, anthropology, philosophy and musicology all come together, which, come to think of it, sounds like a pretty dangerous intersection. Currently I’m in the middle of The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies (2012) edited by Trevor Pinch and Karin Bijsterveld. At the same time, I’m rereading Jacques Attali’s landmark work Noise: The Political Economy of Music (1977). We have a small music/neuroscience book group made up of several editors who work in music and psychology who have an interest in this area. We’ll be discussing the Attali next month.

Who are a few of your favorite music critics/writers?

There are so many – I’m a bit of a criticism junkie. I work a lot with period music journalism in my own research and I love reading music criticism from the early 20th century. It’s so beautifully candid — at times sexy, cruel, completely inappropriate — in a way that’s rare in contemporary criticism. A lot of the reviews were unsigned or pseudonymous, so I’m not sure I have a favorite I can name. There’s a great book by Mark N. Grant on the history of American music criticism called Maestros of the Pen that I highly recommend as an introduction. For rock criticism, Ellen Willis’columns from the Village Voice are still the benchmark for me, I think. Of people writing currently, I like Mark Gresham (classical) and Sasha Frere-Jones (pop). And I like to argue with Alex Ross and John von Rhein.

I also like reading more literary approaches to musical writing. Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful is a poetic, semi-fictional look at jazz, with a mix of stories about legendary musicians like Duke Ellington and Lester Young interspersed with an analytical look at jazz. And some of my favorite writing about music is found in fiction. Three of my favorite novels use music to tell the story. Richard Powers’ The Time of Our Singing uses Marian Anderson’s 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial as the focal point of a story that alternates between a musical mixed-race family and the story of the Civil Rights movement itself. In The Fortress of Solitude, Jonathan Lethem writes beautifully about music of the 1970s that mediates between nearly journalistic detail of Brooklyn in the 1970s and magical realism. And Kathryn Davies’ The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf contains some of the best description of compositional process that I’ve come across in fiction. It’s a challenge to evoke sound in prose – it’s an act of translation – and I admire those who can do it well.

Headline image credit:

The post Getting to know Anna-Lise Santella, Editor of Grove Music Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSalamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance MantuaGetting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann Wilhoite

Related StoriesSalamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance MantuaGetting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann Wilhoite

Are we too “smart” to understand how we see?

About half a century ago, an MIT professor set up a summer project for students to write a computer programme that can “see” or interpret objects in photographs. Why not! After all, seeing must be some smart manipulation of image data that can be implemented in an algorithm, and so should be a good practice for smart students. Decades passed, we still have not fully reached the aim of that summer student project, and a worldwide computer vision community has been born.

We think of being “smart” as including the intellectual ability to do advanced mathematics, complex computer programming, and similar feats. It was shocking to realise that this is often insufficient for recognising objects such as those in the following image.

Fig 5.51 from Li Zhaoping, Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data

Fig 5.51 from Li Zhaoping, Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and DataCan you devise a computer code to “see” the apple from the black-and-white pixel values? A pre-school child could of course see the apple easily with her brain (using her eyes as cameras), despite lacking advanced maths or programming skills. It turns out that one of the most difficult issues is a chicken-and-egg problem: to see the apple it helps to first pick out the image pixels for this apple, and to pick out these pixels it helps to see the apple first.

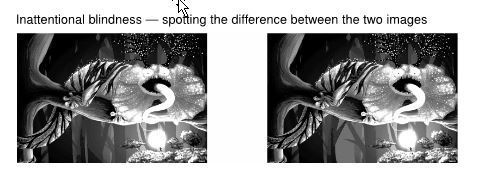

A more recent shocking discovery about vision in our brain is that we are blind to almost everything in front of us. “What? I see things crystal-clearly in front of my eyes!” you may protest. However, can you quickly tell the difference between the following two images?

Alyssa Dayan, 2013 Fig. 1.6 from Li Zhaoping

Alyssa Dayan, 2013 Fig. 1.6 from Li ZhaopingUnderstanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data. Used with permission

It takes most people more than several seconds to see the (big) difference – but why so long? Our brain gives us the impression that we “have seen everything clearly”, and this impression is consistent with our ignorance of what we do not see. This makes us blind to our own blindness! How we survive in our world given our near-blindness is a long, and as yet incomplete, story, with a cast including powerful mechanisms of attention.

Being “smart” also includes the ability to use our conscious brain to reason and make logical deductions, using familiar rules and past experience. But what if most brain mechanisms for vision are subconscious and do not follow the rules or conform to the experience known to our conscious parts of the brain? Indeed, in humans, most of the brain areas responsible for visual processing are among the furthest from the frontal brain areas most responsible for our conscious thoughts and reasoning. No wonder the two examples above are so counter-intuitive! This explains why the most obvious near-blindness was discovered only a decade ago despite centuries of scientific investigation of vision.

Fig 5.9 from Li Zhaoping, Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data

Fig 5.9 from Li Zhaoping, Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and DataAnother counter-intuitive finding, discovered only six years ago, is that our attention or gaze can be attracted by something we are blind to. In our experience, only objects that appear highly distinctive from their surroundings attract our gaze automatically. For example, a lone-red flower in a field of green leaves does so, except if we are colour-blind. Our impression that gaze capture occurs only to highly distinctive features turns out to be wrong. In the following figure, a viewer perceives an image which is a superposition of two images, one shown to each of the two eyes using the equivalent of spectacles for watching 3D movies.

To the viewer, it is as if the perceived image (containing only the bars but not the arrows) is shown simultaneously to both eyes. The uniquely tilted bar appears most distinctive from the background. In contrast, the ocular singleton appears identical to all the other background bars, i.e. we are blind to its distinctiveness. Nevertheless, the ocular singleton often attracts attention more strongly than the orientation singleton (so that the first gaze shift is more frequently directed to the ocular rather than the orientation singleton) even when the viewer is told to find the latter as soon as possible and ignore all distractions. This is as if this ocular singleton is uniquely coloured and distracting like the lone-red flower in a green field, except that we are “colour-blind” to it. Many vision scientists find this hard to believe without experiencing it themselves.

Are these counter-intuitive visual phenomena too alien to our “smart”, intuitive, and conscious brain to comprehend? In studying vision, are we like Earthlings trying to comprehend Martians? Landing on Mars rather than glimpsing it from afar can help the Earthlings. However, are the conscious parts of our brain too “smart” and too partial to “dumb” down suitably to the less conscious parts of our brain? Are we ill-equipped to understand vision because we are such “smart” visual animals possessing too many conscious pre-conceptions about vision? (At least we will be impartial in studying, say, electric sensing in electric fish.) Being aware of our difficulties is the first step to overcoming them – then we can truly be smart rather than smarting at our incompetence.

Headline image credit: Beautiful woman eye with long eyelashes. © RyanKing999 via iStockphoto.

The post Are we too “smart” to understand how we see? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe 150th anniversary of Newlands’ discovery of the periodic systemDmitri Mendeleev’s lost elementsAn etymological journey paved with excellent intentions

Related StoriesThe 150th anniversary of Newlands’ discovery of the periodic systemDmitri Mendeleev’s lost elementsAn etymological journey paved with excellent intentions

The real story of allied nursing during the First World War

The anniversaries of conflicts seem to be more likely to capture the public’s attention than any other significant commemorations. When I first began researching the nurses of the First World War in 2004, I was vaguely aware of an increase in media attention: now, ten years on, as my third book leaves the press, I find myself astonished by the level of interest in the subject. The Centenary of the First World War is becoming a significant cultural event. This time, though, much of the attention is focussed on the role of women, and, in particular, of nurses. The recent publication of several nurses’ diaries has increased the public’s fascination for the subject. A number of television programmes have already been aired. Most of these trace journeys of discovery by celebrity presenters, and are, therefore, somewhat quirky – if not rather random – in their content. The BBC’s project, World War One at Home, has aired numerous stories. I have been involved in some of these – as I have, also, in local projects, such as the impressive recreation of the ‘Stamford Military Hospital’ at Dunham Massey Hall, Cheshire. Many local radio stories have brought to light the work of individuals whose extraordinary experiences and contributions would otherwise have remained hidden – women such as Kate Luard, sister-in-charge of a casualty clearing station during the Battle of Passchendaele; Margaret Maule, who nursed German prisoners-of-war in Dartford; and Elsie Knocker, a fully-trained nurse who established an aid post on the Belgian front lines. One radio story is particularly poignant: that of Clementina Addison, a British nurse, who served with the French Flag Nursing Corps – a unit of fully trained professionals working in French military field hospitals. Clementina cared for hundreds of wounded French ‘poilus’, and died of an unnamed infectious disease as a direct result of her work.

The BBC drama, The Crimson Field was just one of a number of television programmes designed to capture the interest of viewers. I was one of the historical advisers to the series. I came ‘on board’ quite late in the process, and discovered just how difficult it is to transform real, historical events into engaging drama. Most of my work took place in the safety of my own office, where I commented on scripts. But I did spend one highly memorable – and pretty terrifying – week in a field in Wiltshire working with the team producing the first two episodes. Providing ‘authentic background detail’, while, at the same time, creating atmosphere and constructing characters who are both credible and interesting is fraught with difficulty for producers and directors. Since its release this spring, The Crimson Field has become quite controversial, because whilst many people appear to have loved it, others complained vociferously about its lack of authentic detail. Of course, it is hard to reconcile the realities of history with the demands of popular drama.

The Crimson Field poster, with permission from the BBC.

The Crimson Field poster, with permission from the BBC.I give talks about the nurses of the First World War, and often people come up to me to ask about The Crimson Field. Surprisingly often, their one objection is to the fact that the hospital and the nurses were ‘just too clean’. This makes me smile. In these days of contract-cleaners and hospital-acquired infection, we have forgotten the meticulous attention to detail the nurses of the past gave to the cleanliness of their wards. The depiction of cleanliness in the drama was, in fact one of its authentic details.

One of the events I remember most clearly about my work on set with The Crimson Field is the remarkable commitment of director, David Evans, and leading actor, Hermione Norris, in recreating a scene in which Matron Grace Carter enters a ward which is in chaos because a patient has become psychotic and is attacking a padre. The matron takes a sedative injection from a nurse, checks the medication and administers the drug with impeccable professionalism – and this all happens in the space of about three minutes. I remember the intensity of the discussions about how this scene would work, and how many times it was ‘shot’ on the day of filming. But I also remember with some chagrin how, the night after filming, I realised that the injection technique had not been performed entirely correctly. I had to tell David Evans that I had watched the whole sequence six times without noticing that a mistake had been made. Some historical adviser! The entire scene had to be re-filmed. The end result, though, is an impressive piece of hospital drama. Norris looks as though she has been giving intramuscular injections all her life. I shall never forget the professionalism of the director and actors on that set – nor their patience with the absent-minded-professor who was their adviser for the week.

In a centenary year, it can be difficult to distinguish between myths and realities. We all want to know the ‘facts’ or the ‘truths’ about the First World War, but we also want to hear good stories – and it is all the better if those elide facts and enhance the drama of events – because, as human beings, we want to be entertained as well. The important thing, for me, is to fully realise what it is we are commemorating: the significance of the contributions and the enormity of the sacrifices made by our ancestors. Being honest to their memories is the only thing that really matters –the thing that makes all centenary commemoration projects worthwhile.

Image credit: Ministry of Information First World War Collection, from Imperial War Museum Archive. IWM Non Commercial Licence via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The real story of allied nursing during the First World War appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe First World War and the development of international lawRemembering 100 years: Fashion and the outbreak of the Great WarThe month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914

Related StoriesThe First World War and the development of international lawRemembering 100 years: Fashion and the outbreak of the Great WarThe month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914

August 20, 2014

An etymological journey paved with excellent intentions

As can be guessed from the above title, my today’s subject is the derivation of the word road. The history of road has some interest not only because a word that looks so easy for analysis has an involved and, one can say, unsolved etymology but also because it shows how the best scholars walk in circles, return to the same conclusions, find drawbacks in what was believed to be solid arguments, and end up saying: “Origin unknown (uncertain).” The public should know about the effort it takes to recover the past of the words we use. I am acutely aware of the knots language historians have to untie and of most people’s ignorance of the labor this task entails. In a grant application submitted to a central agency ten or so years ago, I promised to elucidate (rather than solve!) the etymology of several hundred English words. One of the referees divided the requested number of dollars by the number of words and wrote an indignant comment about the burden I expected taxpayers to carry (in financial matters, suffering taxpayers are always invoked: they are an equivalent of women and children in descriptions of war; those who don’t pay taxes and men do not really matter). Needless to say, my application was rejected, the taxpayers escaped with a whole skin, and the light remained under the bushel I keep in my office. My critic probably had something to do with linguistics, for otherwise he would not have been invited to the panel. In light of that information I am happy to report that today’s post will cost taxpayers absolutely nothing.

According to the original idea, road developed from Old Engl. rad “riding.” Its vowel was long, that is, similar to a in Modern Engl. spa. Rad belonged with ridan “to ride,” whose long i (a vowel like ee in Modern Engl. fee) alternated with long a by a rule. In the past, roads existed for riding on horseback, and people distinguished between “a road” and “a footpath.” But this seemingly self-evident etymology has to overcome a formidable obstacle: in Standard English, the noun road acquired its present-day meaning late (one can say very late). It was new or perhaps unknown even to Shakespeare. A Shakespeare glossary lists the following senses of road in his plays: “journey on horseback,” “hostile incursion, raid,” “roadstead,” and “highway” (“roadstead,” that is, “harbor,” needn’t surprise us, for ships were said to ride at anchor.) “Highway” appears as the last of the four senses because it is the rarest, but, as we will see, there is a string attached even to such a cautious statement. Raid is the Scots version of road (“long a,” mentioned above, developed differently in the south and the north; hence the doublets). In sum, road used to mean “raid” and “riding.” When English speakers needed to refer to a road, they said way, as, for example, in the Authorized Version of the Bible.

No disquisition, however learned, will answer in a fully convincing manner why about 250 years ago road partly replaced way. But there have been attempts to overthrow even the basic statement. Perhaps, it was proposed, road does not go back to Old. Engl. rad, with its long vowel! This heretical suggestion was first put forward in 1888 by Oxford Professor of Anglo-Saxon John Earle. In his opinion, the story began with rod “clearing.” The word has not made it into the Standard, but we still rid our houses of vermin and get rid of old junk. Rid is related to Old Engl. rod.

Earle’s command of Old English was excellent, but he did not care much about phonetic niceties. In his opinion, if meanings show that certain words are allied, phoneticians should explain why something has gone wrong in their domain rather than dismissing an otherwise persuasive conclusion as invalid. This type of reasoning cut no ice with the etymologists of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Nor does it thrill modern researchers, even though at all times there have been serious scholars who refused to bow to the tyranny of so-called phonetic laws. Such mavericks face a great difficulty, for, if we allow ourselves to be guided by similarity of meaning in disregard of established sound correspondences, we may return to the fantasies of medieval etymology. Earle tried to posit long o in rod, though not because he had proof of its length but because he needed it to be long. A. L. Mayhew, whom I mentioned in the post on qualm, and Skeat dismissed the rod-road etymology as not worthy of discussion. Surprisingly, it was revived ten years ago (without reference to Earle), now buttressed by phonetic arguments. It appears that rod with a long vowel did exist, but, more probably, its length was due to a later process. In any case, Earle would have been thrilled. I have said more than once that etymology is a myth of eternal return.

Before 1917, crowds of prisoners in shackles marched along the Vladimir Highway, known as Vladimirka, to the place of their exile in Siberia. (Isaak Levitan. The Vladimirka (1892). Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Before 1917, crowds of prisoners in shackles marched along the Vladimir Highway, known as Vladimirka, to the place of their exile in Siberia. (Isaak Levitan. The Vladimirka (1892). Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)Whatever the origin of road, we still wonder why its modern sense emerged so late. In 1934, this question was the subject of a lively exchange in the pages of The Times Literary Supplement. In response to that discussion the German scholar Max Deutschbein showed that Shakespeare never used road “way” without making it clear what he meant. Once he used the compound roadway. Elsewhere some road is followed by as common as the way between…. We read about the even road of a blank verse, easy roads (for riding), and a thievish living on the common road. The word way helps us understand what is meant in You know the very road (= “journey”: OED) into his kindness, / and cannot lose your way (Coriolanus). Deutschbein concluded that Shakespeare hardly knew our sense of road.

This sense had become universally understood only by the sixteen-seventies (Shakespeare died in 1616), and Milton (1608-1674) used it “unapologetically.” So how did it arise? Extraneous influences—Scottish and Irish—have often been considered; the arguments for their role are thin. The anonymous initiator of the discussion in The Times Literary Supplement (I am sure the author’s name is known) spun a wonderful yarn about how Shakespeare met a group of Scotsmen, learned something about the Scots, and picked up a new word. The story is clever but not particularly trustworthy. The Irish connection is even less likely. Deutschbein noted that, according to the OED, the compound roadway reached the peak of its popularity in the seventeenth century and disappeared once road established itself. Is it possible that this is where we should look for the solution of the riddle? Etymological riddles are always hard, while solutions are usually simple, and the simpler they are, the higher the chance that they are correct.

No citations for the noun roadway antedating 1600 have been found. We don’t know how early in the sixteenth century it arose, but in this case an exact date is of little consequence. The OED suggests that the earliest meaning of roadway was “riding way,” and so it must have been. At some time, speakers probably reinterpreted this noun as a tautological compound (which it was not), a word like pathway, apparently, a sixteenth-century coinage, and many others like them. Words having this meaning are prone to be made up of two near-synonyms (way-way, road-road, path-path); see my old post on such compounds. Roadway could have continued its existence for centuries, but at some time the second element was dumped as superfluous. For a relatively short period road coexisted with way as its equal partner, but then they divided their spheres of influence: road began to refer to physical reality and way to more abstract situations. We speak of impassable roads and road maps, as opposed to the way of all flesh and ways and means committees. Extraneous influences were not needed for such a process to happen.

I often complain that the scholarly literature on some words is meager. By contrast, the literature on road is extensive. A long paper devoted to it was published as recently as a year ago, whence an extremely detailed etymological introduction to the entry road in the OED online. Even if I failed to discern the complexity of the problem and untie or cut the knot, my intentions were good.

The post An etymological journey paved with excellent intentions appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe history of the word “qualm”There are more ways than one to be thunderstruckMonthly etymology gleanings for July 2014

Related StoriesThe history of the word “qualm”There are more ways than one to be thunderstruckMonthly etymology gleanings for July 2014

The 150th anniversary of Newlands’ discovery of the periodic system

The discovery of the periodic system of the elements and the associated periodic table is generally attributed to the great Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. Many authors have indulged in the game of debating just how much credit should be attributed to Mendeleev and how much to the other discoverers of this unifying theme of modern chemistry.

In fact the discovery of the periodic table represents one of a multitude of multiple discoveries which most accounts of science try to explain away. Multiple discovery is actually the rule rather than the exception and it is one of the many hints that point to the interconnected, almost organic nature of how science really develops. Many, including myself, have explored this theme by considering examples from the history of atomic physics and chemistry.

But today I am writing about a subaltern who discovered the periodic table well before Mendeleev and whose most significant contribution was published on 20 August 1864, or precisely 150 years ago. John Reina Newlands was an English chemist who never held a university position and yet went further than any of his contemporary professional chemists in discovering the all-important repeating pattern among the elements which he described in a number of articles.

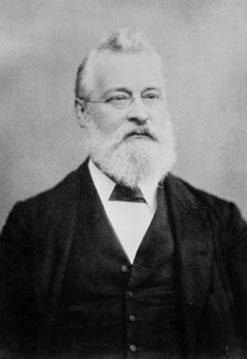

John Reina Newlands. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Reina Newlands. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Newlands came from Southwark, a suburb of London. After studying at the Royal College of chemistry he became the chief chemist at Royal Agricultural Society of Great Britain. In 1860 when the leading European chemists were attending the Karlsruhe conference to discuss such concepts as atoms, molecules and atomic weights, Newlands was busy volunteering to fight in the Italian revolutionary war under Garibaldi. This is explained by the fact that his mother was Italian descent, which also explains his having the middle name Reina. In any case he survived the fighting and set about thinking about the elements on his return to London to become a sugar chemist.

In 1863 Newlands published a list of elements which he arranged into 11 groups. The elements within each of his groups had analogous properties and displayed weights that differed by eight units or some factor of eight. But no table yet!

Nevertheless he even predicted the existence of a new element, which he believed should have an atomic weight of 163 and should fall between iridium and rhodium. Unfortunately for Newlands neither this element, or a few more he predicted, ever materialized but it does show that the prediction of elements from a system of elements is not something that only Mendeleev invented.

In the first of three articles of 1864 Newlands published his first periodic table, five years before Mendeleev incidentally. This arrangement benefited from the revised atomic weights that had been announced at the Karlsruhe conference he had missed and showed that many elements had weights differing by 16 units. But it only contained 12 elements ranging between lithium as the lightest and chlorine as the heaviest.

Then another article, on 20 August 1864, with a slightly expanded range of elements in which he dropped the use of atomic weights for the elements and replaced them with an ordinal number for each one. Historians and philosophers have amused themselves over the years by debating whether this represents an anticipation of the modern concept of atomic number, but that’s another story.

More importantly Newlands now suggested that he had a system, a repeating and periodic pattern of elements, or a periodic law. Another innovation was Newlands’ willingness to reverse pairs of elements if their atomic weights demanded this change as in the case of tellurium and iodine. Even though tellurium has a higher atomic weight than iodine it must be placed before iodine so that each element falls into the appropriate column according to chemical similarities.

The following year, Newlands had the opportunity to present his findings in a lecture to the London Chemical Society but the result was public ridicule. One member of the audience mockingly asked Newlands whether he had considered arranging the elements alphabetically since this might have produced an even better chemical grouping of the elements. The society declined to publish Newlands’ article although he was able to publish it in another journal.

In 1869 and 1870 two more prominent chemists who held university positions published more elaborate periodic systems. They were the German Julius Lothar Meyer and the Russian Dmitri Mendeleev. They essentially rediscovered what Newlands found and made some improvements. Mendeleev in particular made a point of denying Newlands’ priority claiming that Newlands had not regarded his discovery as representing a scientific law. These two chemists were awarded the lion’s share of the credit and Newlands was reduced to arguing for his priority for several years afterwards. In the end he did gain some recognition when the Davy award, or the equivalent of the Nobel Prize for chemistry at the time, and which had already been jointly awarded to Lothar Meyer and Mendeleev, was finally accorded to Newlands in 1887, twenty three years after his article of August 1864.

But there is a final word to be said on this subject. In 1862, two years before Newlands, a French geologist, Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois had already published a periodic system that he arranged in a three-dimensional fashion on the surface of a metal cylinder. He called this the “telluric screw,” from tellos — Greek for the Earth since he was a geologist and since he was classifying the elements of the earth.

Image: Chemistry by macaroni1945. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The 150th anniversary of Newlands’ discovery of the periodic system appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDmitri Mendeleev’s lost elementsGeorge Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witchChanging legal education

Related StoriesDmitri Mendeleev’s lost elementsGeorge Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witchChanging legal education

Dmitri Mendeleev’s lost elements

Dmitri Mendeleev believed he was a great scientist and indeed he was. He was not actually recognized as such until his periodic table achieved worldwide diffusion and began to appear in textbooks of general chemistry and in other major publications. When Mendeleev died in February 1907, the periodic table was established well enough to stand on its own and perpetuate his name for upcoming generations of chemists.

The man died, but the myth was born.

Mendeleev as a legendary figure grew with time, aided by his own well-organized promotion of his discovery. Well-versed in foreign languages and with a sort of overwhelming desire to escape his tsar-dominated homeland, he traveled the length and breadth of Europe, attending many conferences in England, Germany, Italy, and central Europe, his only luggage seemingly his periodic table.

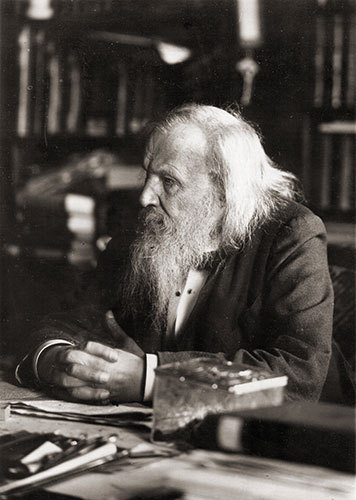

Dmitri Mendeleev, 1897. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Dmitri Mendeleev, 1897. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Mendeleev had succeeded in creating a new tool that chemists could use as a springboard to new and fascinating discoveries in the fields of theoretical, mineral, and general chemistry. But every coin has two faces, even the periodic table. On the one hand, it lighted the path to the discovery of still missing elements; on the other, it led some unfortunate individuals to fall into the fatal error of announcing the discovery of false or spurious supposed new elements. Even Mendeleev, who considered himself the Newton of the chemical sciences, fell into this trap, announcing the discovery of imaginary elements that presently we know to have been mere self-deception or illusion.

It probably is not well-known that Mendeleev had predicted the existence of a large number of elements, actually more than ten. Their discoveries were sometimes the result of lucky guesses (like the famous cases of gallium, germanium, and scandium), and at other times they were erroneous. Historiography has kindly passed over the latter, forgetting about the long line of imaginary elements that Mendeleev had proposed, among which were two with atomic weights lower than that of hydrogen, newtonium (atomic weight = 0.17) and coronium (Atomic weight = 0.4). He also proposed the existence of six new elements between hydrogen and lithium, whose existence could not but be false.

Mendeleev represented a sort of tormented genius who believed in the universality of his creature and dreaded the possibility that it could be eclipsed by other discoveries. He did not live long enough to see the seed that he had planted become a mighty tree. He fought equally, with fierce indignation, the priority claims of others as well as the advent of new discoveries that appeared to menace his discovery.

In the end, his table was enduring enough to accommodate atomic number, isotopes, radioisotopes, the noble gases, the rare earth elements, the actinides, and the quantum mechanics that endowed it with a theoretical framework, allowing it to appear fresh and modern even after a scientific journey of 145 years.

Image: Nursery of new stars by NASA, Hui Yang University of Illinois. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Dmitri Mendeleev’s lost elements appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistryGeorge Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witchThe environmental case for nuclear power

Related StoriesNicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistryGeorge Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witchThe environmental case for nuclear power

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers