Oxford University Press's Blog, page 772

August 20, 2014

Changing legal education

Martin Partington discussed a range of careers in his podcasts yesterday. Today, he tackles how new legal issues and developments in the professional environment have in turn changed organizational structures, rules and regulations, and aspects of legal education.

Co-operative Legal Services: An interview with Christina Blacklaws

Co-operative Legal Services was the first large organisation to be authorised by the Solicitors Regulatory Authority as an Alternative Business Structure. In this podcast, Martin talks to Christina Blacklaws, Head of Policy of Co-operative Legal Services.

The role of chartered legal executives: An interview with Diane Burleigh

The Chartered Institute of Legal Executives sets standards for and regulates the activities of legal executives, who play an important role in the delivery of legal services. In this podcast Martin talks with Diane Burleigh, the Chief Executive of CILEX, about the challenges facing the legal profession and the opportunities provided for Legal Executives in the rapidly developing legal world.

Educating Judges and the Judicial College: An interview with Lady Justice Hallett

The Judicial College was created by bringing together separate arrangements that had previously existed for training judicial office-holders in the courts (the Judicial Studies Board) and Tribunals Service (through the Tribunals Judicial Training Group). In this podcast Martin talks to its Chairman, Lady Justice Hallett, about the reasons for the change and ways in which the College is developing new ideas about judicial education.

Headline image credit: Law student and lecturer or academic. © Palto via iStockphoto.

The post Changing legal education appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLaw careers from restorative justice, to legal ombudsman, to mediaChallenges facing UK law studentsThe OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition

Related StoriesLaw careers from restorative justice, to legal ombudsman, to mediaChallenges facing UK law studentsThe OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition

The road to egalitaria

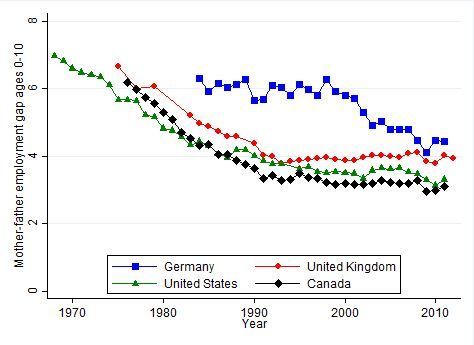

In 1985, Nobel Laureate Gary Becker observed that the gap in employment between mothers and fathers of young children had been shrinking since the 1960s in OECD countries. This led Becker to predict that such sex differences “may only be a legacy of powerful forces from the past and may disappear or be greatly attenuated in the near future.” In the 1990s, however, the shrinking of the mother-father gap stalled before Becker’s prediction could be realized. In today’s economy, how big is this mother-father employment gap, what forces underlie it, and are there any policies which could close it further?

A simple way to characterize the mother-father employment gap is to sum up how much more work is done by fathers compared to mothers of children from ages 0 to 10. In 2010, fathers in the United States worked 3.1 more years on average than mothers over this age 0 to 10 age range. In the United Kingdom, the comparable number is 3.8, while in Canada it is 2.9 and Germany 4.5. The figure below traces the evolution of this mother-father employment gap for all four of these countries.

Graph shows the difference in years worked by mothers and fathers when their children are between the ages of 0 to 10. (Graph credit: Milligan, 2014 CESifo Economic Studies)

Graph shows the difference in years worked by mothers and fathers when their children are between the ages of 0 to 10. (Graph credit: Milligan, 2014 CESifo Economic Studies)Becker’s theorizing about the family can help us to understand the development of this mother-father employment gap. Becker’s theoretical models suggest that if there are even slight differences between the productivity of mothers and fathers in the home vs. the workplace, spouses will tend to specialize completely in either in-home or in out-of-home work. These kind of productivity differences could arise because of cultural conditioning, as society pushes certain roles and expectations on women and men. Also, biology could be important as women have a heavier physical burden during pregnancy and after the birth of a child women have an advantage in breastfeeding. It is possible that the initial impact of these unique biological roles for mothers lingers as their children age. Biology is not destiny, but should be acknowledged as a potential barrier that contributes to the origins of the mother-father work gap.

Will today’s differences in mother-father work patterns persist into the future? To some extent that may depend on how cultural attitudes evolve. But there’s also the possibility that family-friendly policy can move things along more quickly. Both parental leave and subsidized childcare are options to consider.

Analysis of some data across the four countries suggest that these kinds of policies can make some difference, but the impact is limited.

Parental leave makes a very big difference when the children are age zero and the parent is actually taking the leave—but because mothers take much more parental leave than fathers, this increases the mother-father employment gap rather than shrinking it. Evidence suggests that after age 0 when most parents return to work, there doesn’t seem to be any lasting impact of having taken a maternity leave on mothers’ employment patterns when their children are ages 1 to 10.

Another policy that might matter is childcare. In the Canadian province of Quebec, a subsidized childcare program was put in place in 1997 that required parents to pay only $5 per day for childcare. This program not only increased mothers’ work at pre-school ages, but also seems to have had a lasting impact when their children reach older ages, as employment of women in Quebec increased at all ages from 0 to 10. When summed up over these ages, Quebec’s subsidized childcare closed the mother-father employment gap by about half a year of work.

Gary Becker’s prediction about the disappearance of mother-father work gaps hasn’t come true – yet. Evidence from Canada, Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom suggests that policy can contribute to a shrinking of the mother-father employment gap. However, the analysis makes clear that policy alone may not be enough to overcome the combination of strong cultural attitudes and any persistence of intrinsic biological differences between mothers and fathers.

Image credit: Hispanic mother with two children, © Spotmatik, via iStock Photo.

The post The road to egalitaria appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?Why referendum campaigns are crucialWhat is the role of governments in climate change adaptation?

Related StoriesCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?Why referendum campaigns are crucialWhat is the role of governments in climate change adaptation?

Pigment profile in the photosynthetic sea slug Elysia viridis

How can sacoglossan sea slugs perform photosynthesis – a process usually associated with plants?

Kleptoplasty describes a special type of endosymbiosis where a host organism retain photosynthetic organelles from their algal prey. Kleptoplasty is widespread in ciliates and foraminifera; however, within Metazoa animals (animals having the body composed of cells differentiated into tissues and organs, and usually a digestive cavity lined with specialized cells), sacoglossan sea slugs are the only known species to harbour functional plastids. This characteristic gives these sea slugs their very special feature.

The “stolen” chloroplasts are acquired by the ingestion of macro algal tissue and retention of undigested functional chloroplasts in special cells of their gut. These “stolen” chloroplasts (thereafter named kleptoplasts) continue to photosynthesize for varied periods of time, in some cases up to one year.

In our study, we analyzed the pigment profile of Elysia viridis in order to evaluate appropriate measures of photosynthetic activity.

The pigments siphonaxanthin, trans and cis-neoxanthin, violaxanthin, siphonaxanthin dodecenoate, chlorophyll (Chl) a and Chl b, ε,ε- and β,ε-carotenes, and an unidentified carotenoid were observed in all Elysia viridis. With the exception of the unidentified carotenoid, the same pigment profile was recorded for the macro algae C. tomentosum (its algal prey).

In general, carotenoids found in animals are either directly accumulated from food or partially modified through metabolic reactions. Therefore, the unidentified carotenoid was most likely a product modified by the sea slugs since it was not present in their food source.

Image credit: Lettuce sea slug, by Laszlo Ilyes. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Lettuce sea slug, by Laszlo Ilyes. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Pigments characteristic of other macro algae present in the sampling locations were not detected inthe sea slugs. These results suggest that these Elysia viridis retained chloroplasts exclusively from C. tomentosum.

In general, the carotenoids to Chl a ratios were significantly higher in Elysia viridis than in C. tomentosum. Further analysis using starved individuals suggests carotenoid retention over Chlorophylls during the digestion of kleptoplasts. It is important to note that, despite a loss of 80% of Chl a in Elysia viridis starved for two weeks, measurements of maximum capacity of performing photosynthesis indicated a decrease of only 5% of the photosynthetic capacity of kleptoplasts that remain functional.

This result clearly illustrates that measurement of photosynthetic activity using this approach can be misleading when evaluating the importance of kleptoplasts for the overall nutrition of the animal.

Finally, concentrations of violaxanthin were low in C. tomentosum and Elysia viridis and no detectable levels of antheraxanthin or zeaxanthin were observed in either organism. Therefore, the occurrence of a xanthophyll cycle as a photoregulatory mechanism, crucial for most photosynthetic organisms, seems unlikely to occur in C. tomentosum and Elysia viridis but requires further research.

The post Pigment profile in the photosynthetic sea slug Elysia viridis appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat goes up must come downWhy referendum campaigns are crucialCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?

Related StoriesWhat goes up must come downWhy referendum campaigns are crucialCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?

August 19, 2014

Why referendum campaigns are crucial

As we enter the potentially crucial phase of the Scottish independence referendum campaign, it is worth remembering more broadly that political campaigns always matter, but they often matter most at referendums.

Referendums are often classified as low information elections. Research demonstrates that it can be difficult to engage voters on the specific information and arguments involved (Lupia 1994, McDermott 1997) and consequently they can be decided on issues other than the matter at hand. Referendums also vary from traditional political contests, in that they are usually focused on a single issue; the dynamics of political party interaction can diverge from national and local elections; non-political actors may often have a prominent role in the campaign; and voters may or may not have strong, clear views on the issue being decided. Furthermore, there is great variation in the information environment at referendums. As a result the campaign itself can be vital.

We can understand campaigns through the lens of LeDuc’s framework which seeks to capture some of the underlying elements which can lead to stability or volatility in voter behaviour at referendums. The essential proposition of this model is that referendums ask different types of questions of voters, and that the type of question posed conditions the behaviour of voters. Referendums that ask questions related to the core fundamental values and attitudes held by voters should be stable. Voters’ opinions that draw on cleavages, ideology, and central beliefs are unlikely to change in the course of a campaign. Consequently, opinion polls should show very little movement over the campaign. At the other end of the spectrum, volatile referendums are those which ask questions on which voters do not have pre-conceived fixed views or opinions. The referendum may ask questions on new areas of policy, previously un-discussed items, or items of generally low salience such as political architecture or institutions.

Another essential component determining the importance of the campaign are undecided voters. When voter political knowledge emanates from a low base, the campaign contributes greatly to increasing political knowledge. This point is particularly clear from Farrell and Schmitt-Beck (2002) where they demonstrated that voter ignorance is widespread and levels of political knowledge among voters are often overestimated. As Ian McAllister argues, partisan de-alignment has created a more volatile electoral environment and the number of voters who make their decisions during campaigns has risen. In particular, there has been a sharp rise in the number of voters who decide quite late in a campaign. In this case, the campaign learning is vital and the campaign may change voters’ initial disposition. Opinions may only form during the campaign when voters acquire information and these opinions may be changeable, leading to volatility.

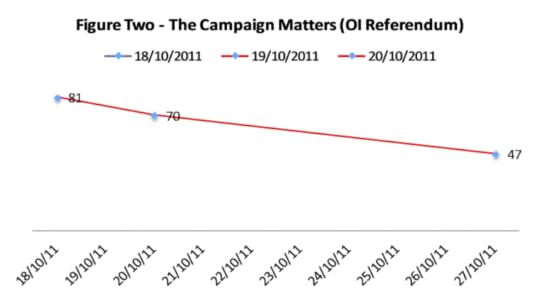

The experience of referendums in Ireland is worth examining as Ireland is one of a small but growing number of countries which makes frequent use of referendums. It is also worth noting that Ireland has a highly regulated campaign environment. In the Oireachtas Inquiries Referendum 2011, Irish voters were asked to decide on a parliamentary reform proposal (Oireachtas Inquiries – OI) in October 2011. The issue was of limited interest to voters and co-scheduled with a second referendum on reducing the pay of members of the judiciary along with a lively presidential election.

The OI referendum was defeated by a narrow margin and the campaign period witnessed a sharp fall in support for the proposal. Only a small number of polls were taken but the sharp decline is clear from the figure below.

The Campaign Matters (OI Referendum)

The Campaign Matters (OI Referendum)Few voters had any existing opinion on the proposal and the post-referendum research indicated that voters relied significantly on heuristics or shortcuts emanating from the campaign and to a lesser extent on either media campaigns or rational knowledge. The evidence showed that just a few weeks after the referendum, many voters were unable to recall the reasons for their voting decision. An interesting result was that while there was underlying support for the reform with 74% of all voters in support of Oireachtas Inquiries in principle, it failed to pass. There was a very high level of ignorance of the issues where some 44% of voters could not give cogent reasons for why they voted ‘no’, underlining the common practice of ‘if you don’t know, vote no’.

So are there any lessons we can draw for Scottish Independence campaign? Scottish independence would likely be placed on the stable end of the Le Duc spectrum in that some voters could be expected to have an ideological predisposition on this question. Campaigns matter less at these types of referendums. However, they are by no means a foregone conclusion. We would expect that the number of undecided voters will be key and these voters may use shortcuts to make their decision. In other words the positions of the parties, of celebrities of unions and businesses and others will likely matter. In addition, the extent to which voters feel fully informed on the issues will also possibly be a determining factor. It may be instructive to look at another Irish referendum, on the introduction of divorce in the 1980s, during which voters’ opinions moved sharply during the campaign, even though the referendum question drew largely from the deep rooted conservative-liberal cleavage in Irish politics (Darcy and Laver 1990). The Scottish campaign might thus still conceivably see some shifts in opinion.

Headline image: Scottish Parliament Building via iStockphoto.

The post Why referendum campaigns are crucial appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?Improving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna AtkesonThe First World War and the development of international law

Related StoriesCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?Improving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna AtkesonThe First World War and the development of international law

George Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witch

On 19 August 1692, George Burroughs stood on the ladder and calmly made a perfect recitation of the Lord’s Prayer. Some in the large crowd of observers were moved to tears, so much so that it seemed the proceedings might come to a halt. But Reverend Burroughs had uttered his last words. He was soon “turned off” the ladder, hanged to death for the high crime of witchcraft. After the execution, Reverend Cotton Mather, who had been watching the proceedings from horseback, acted quickly to calm the restless multitude. He reminded them among other things “that the Devil has often been transformed into an Angel of Light” — that despite his pious words and demeanor, Burroughs had been the leader of Satan’s war against New England. Thus assured, the executions would continue. Five people would die that day, one of most dramatic and important in the course of the Salem witch trials. For the audience on 19 August realized that if a Puritan minister could hang for witchcraft, then no one was safe. Their tears and protests were the beginning of the public opposition that would eventually bring the trials to an end. Unfortunately, by the time that happened, nineteen people had been executed, one pressed to death, and five perished in the wretched squalor of the Salem and Boston jails.

The fact that a Harvard-educated Puritan minister was considered the ringleader of the largest witch hunt in American history is one of the many striking oddities about the Salem trials. Yet, a close look at Burroughs reveals that his character and his background personified virtually all the fears and suspicions that ignited witchcraft accusations in 1692. There was no single cause, no simple explanation to why the Salem crisis happened. Massachusetts Bay faced a confluence of events that produced the fears and doubts that led to the crisis. Likewise, a wide range of people faced charges for having supposedly committed diverse acts of witchcraft against a broad swath of the populace. Yet, there were many reasons people were suspicious of George Burroughs, indeed he was the perfect witch.

In 1680 when Burroughs was hired to be the minister of Salem Village he quickly became a central figure in the on-going controversy over religion, politics, and money that would span more than thirty years and result in the departure of the community’s first four ministers. One of Burroughs’s parishioners wrote to him, complaining that “Brother is against brother and neighbors against neighbors, all quarreling and smiting one another.” After a little over two years in office, the Salem Village Committee stopped paying Burroughs’s salary, so he wisely left town to return to his old job, as minister of Falmouth (now Portland, Maine).

George Burroughs spent most of his career in Falmouth, a town on the edge of the frontier. He was fortunate to escape the bloody destruction of the settlement by Native Americans in 1676 (during King Philip’s War) and 1690 (during King William’s War). The latter conflict brought a string of disastrous defeats to Massachusetts, and as many historians have noted, the ensuing war panic helped trigger the witch trials. The war was a spiritual defeat for the Puritan colony as they were losing to French Catholics allied with people they considered to be “heathen” Indians. It seemed Satan’s minions would end the Puritans’ New England experiment. Burroughs was one of many refugees from Maine who were either afflicted by or accused of witchcraft. In addition, most of the judges were military officers as well as speculators in Maine lands that the war had made worthless. Some of the afflicted refugees were suffering what today would be considered post-traumatic shock. Used to the manual labor of the frontier, Burroughs was so incredibly strong that several would testify in 1692 to his feats of supernatural strength. The minister’s seemingly miraculous escapes from Falmouth in 1676 and 1690 also brought him under suspicion. Perhaps he had done so with the help of the devil, or the Indians.

Bench in memory of George Burroughs at the Salem Witch Trials Memorial, Salem, Massachusetts. Photo by Emerson W. Baker.

Bench in memory of George Burroughs at the Salem Witch Trials Memorial, Salem, Massachusetts. Photo by Emerson W. Baker.Tainted by his frontier ties, the twice-widowed Burroughs’s personal life and perceived religious views amplified fears of the minister. At his trial, several testified to his secretive ways, his seemingly preternatural knowledge, and his strict rule over his wives. He forbid his wives to speak about him to others, and even censored their letters to family. Meanwhile the afflicted said they saw the specters of Burroughs’s late wives, who claimed he murdered them. The charges were groundless. However, his controlling ways and the spectacular testimony against him at least raised the question of domestic abuse. Such perceived abuse of authority — at the family, community or colony-wide level — is a common thread linking many of Salem’s accused.

Some observers believed Burroughs was secretive because they suspected he was a Baptist. This Protestant sect had legal toleration but like the Quakers, was considered dangerous by most Massachusetts Puritans because of their belief in adult baptism and adult-only membership in the church. Burroughs admitted to the Salem judges that he had not recently received Puritan communion and had not baptized his younger children (both signs that he might be a Baptist). His excuse was that he was never ordained and hence could not lead the communion service, nor could he baptize children. However, since Burroughs left his post in Maine, he admitted he had visited Boston and Charlestown and had failed to take advantage of these rights there.

Even if he was not a Baptist, as a Puritan minister he was at risk. Burroughs was just one of five ministers cried out upon in 1692. Fully, 30 percent of the people accused were ministers, their immediate family members, or extended kin. In many ways, the witch trials were a critique of the religious and political policies of the colony. But that is another story.

Header image taken by Emerson W. Baker.

The post George Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witch appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEngaged Buddhism and community ecologyThe First World War and the development of international lawSalamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance Mantua

Related StoriesEngaged Buddhism and community ecologyThe First World War and the development of international lawSalamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance Mantua

Salamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance Mantua

Grove Music Online presents this multi-part series by Don Harrán, Artur Rubinstein Professor Emeritus of Musicology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, on the life of Jewish musician Salamone Rossi on the anniversary of his birth in 1570. Professor Harrán considers three major questions: Salamone Rossi as a Jew among Jews; Rossi as a Jew among Christians; and the conclusions to be drawn from both.

Salamone Rossi as a Jew among Jews

What do we know of Salamone Rossi’s family? His father was named Bonaiuto Azaria de’ Rossi (d. 1578): he composed Me’or einayim (Light of the Eyes). Rossi had a brother, Emanuele (Menaḥem), and a sister, Europe, who, like him, was a musician. She is known to have performed as a singer in the play Il ratto di Europa (“The Rape of Europa”) in 1608. The court chronicler Federico Follino raved over her performance, describing it as that of “a woman understanding music to perfection” and “singing, to the listeners’ great delight and their greater wonder, in a most delicate and sweet-sounding voice.”

Salamone Rossi appears to have used his connections at court to improve his family’s situation, as in 1602 when Rossi wrote to Duke Vincenzo on behalf of his brother Emanuele:

Letter that Salamone Rossi wrote on behalf of his brother Emanuele (21 February 1606); fair copy, with the close and signature in Rossi’s own hand. Archivio Storico, Archivio Storico, Mantua.

Letter that Salamone Rossi wrote on behalf of his brother Emanuele (21 February 1606); fair copy, with the close and signature in Rossi’s own hand. Archivio Storico, Archivio Storico, Mantua.The duke granted the request in order to “to show Salamone Rossi ebreo some sign of gratitude for services that he, with utmost diligence, rendered and continues to render over many years. We have resolved to confer the duties of collecting the fees on the person of Emanuele, Salamone’s brother, in whose faith and diligence we place our confidence.”

Until now, it has been thought that Rossi earned his livelihood from his salary at the Mantuan court, and since the salary was—by comparison with that of other musicians at the court—very small, Rossi tried to supplement it by earning money on the side by investments. From 1622 on he was earning 1,200 lire, a large sum of money for a musician whose annual wages at the court were only 156 lire. Rossi needed the money to cover the cost of his publications and to support his family.

Rossi’s situation within the community can only be conjectured. By “community,” we are talking about some 2,325 Jews living in the city of Mantua out of a total population of 50,000. True, Rossi was its most distinguished “musician” and his service for the court would have brought honor on the Jewish community. But because of his non-Jewish connections, he enjoyed privileges denied his coreligionists. In 1606, for example, he was exempted from wearing a badge. The badge was shameful to Jews who, in their activities, were in close touch with Christians, as were Rossi and other Jews who performed before them as musicians or actors or who engaged in loan banking.

As other “privileged” Jews, Rossi occupied a difficult situation: his Christian employers considered him a Jew, yet the Jews probably considered him an outsider. He could choose from two alternatives: convert to Christianity to improve his situation with the Christians; or solidify his position within the Jewish community, which he probably did whenever he could by representing its interests before the authorities and by providing compositions for Jewish weddings, circumcisions, the inauguration of Torah scrolls, and for Purim festivities. All this is speculative, for we know nothing about these activities. We are better informed about Rossi’s role in the Jewish theater, whose actors were required to prepare each year one or two plays with musical intermedi. Since the Jews were expected to act, sing, and play instruments, their leading musician Salamone Rossi probably contributed to the theater by writing vocal and instrumental works, rehearsing them and, together with others, playing or even singing them.

Salamone Rossi, Ha-shirim asher li-Shelomoh (“Songs by Solomon”), 1623, no. 8. See Salamone Rossi, Complete Works, ed. Don Harrán (Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae 100), vols. 1–12 (Neuhausen-Stuttgart: Hänssler-Verlag for the American Institute of Musicology), vols. 13a and 13b (Madison WI: American Institute of Musicology, 1995), 13b: 24–26.

Salamone Rossi, Ha-shirim asher li-Shelomoh (“Songs by Solomon”), 1623, no. 8. See Salamone Rossi, Complete Works, ed. Don Harrán (Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae 100), vols. 1–12 (Neuhausen-Stuttgart: Hänssler-Verlag for the American Institute of Musicology), vols. 13a and 13b (Madison WI: American Institute of Musicology, 1995), 13b: 24–26.It was in his Hebrew collection, however, that Rossi demonstrated his connections with his people. His intentions were good: after having published collections of Italian vocal music and instrumental works, Rossi decided, around 1612, to write Hebrew songs. He describes these songs as “new songs [zemirot] that I devised through ‘counterpoint’ [seder].” True, attempts were made to introduce art music into the synagogue in the early seventeenth century. But none of these early works survive. Rossi’s thirty-three “Songs by Solomon” (Ha-shirim asher li-Shelomoh) are the first Hebrew polyphonic “songs” to be printed. Here is an example from the opening of the collection, “Elohim, hashivenu”.

Good intentions are one thing; the status of art music in the synagogue is another. The prayer services made no accommodation for art music. Rossi’s aim, to quote him, was to write works “for thanking God and singing [le-zammer] to His exalted name on all sacred occasions” to be performed in prayer services, particularly on Sabbaths and festivals.

Headline image credit: Opening of Salomone de Rossi’s Madrigaletti, Venice, 1628. Photo of Exhibit at the Diaspora Museum, Tel Aviv. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Salamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance Mantua appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSongs of the Alaskan InuitJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever saw

Related StoriesSongs of the Alaskan InuitJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever saw

Law careers from restorative justice, to legal ombudsman, to media

What range of career options are out there for those attending law school? In this series of podcasts, Martin Partington talks to influential figures in the law about topics ranging from restorative justice to legal journalism.

Restorative Justice: An interview with Lizzie Nelson

The Restorative Justice Council is a small charitable organisation that exists to promote the use of restorative justice, not just in the court (criminal justice) context, but in other situations of conflict as well (e.g. schools). In this podcast Martin talks to Lizzie Nelson, Director of the Restorative Justice Council.

Handling complaints against lawyers: An interview with Adam Sampson

In this podcast, Martin talks to Adam Sampson, Chief Legal Ombudsman. They discuss the work of the Legal Ombudsman, how it operates, the kinds of issue it deals with, and some of the limitations the office has to deal with matters raised by dissatisfied clients.

Reporting the law: An interview with Joshua Rozenberg

Joshua Rozenberg is one of a very small number of specialist journalists who cover legal issues in a serious and thoughtful way. He has worked in a wide variety of media, including the BBC, The Daily Telegraph, and The Guardian. In this interview, he describes how he decided to become a journalist rather than a practising lawyer and comments on the challenges of devising ways to enable legal issues to be raised in mass media.

Headline image credit: Law student and lecturer or academic. © Palto via iStockphoto.

The post Law careers from restorative justice, to legal ombudsman, to media appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesChallenges facing UK law studentsThe OUP and BPP National Mooting CompetitionThe First World War and the development of international law

Related StoriesChallenges facing UK law studentsThe OUP and BPP National Mooting CompetitionThe First World War and the development of international law

August 18, 2014

Introducing the new OUPblog

Loyal readers will have noticed a few changes to the OUPblog over the past week. Every few years, we redesign the OUPblog as technology changes and the needs of our editors and readers evolve. We have retired the design we have been using since 2010 and updated the OUPblog to a fresh look and feel.

Our top priority has been making the OUPblog easier to navigate. We have streamlined many of the links and widgets that you see — and the processes that you don’t see — so that it is more straightforward to scroll through and click. We have shifted to a responsive design, so that the OUPblog is effortless to view on desktop, tablet, or mobile phone. Our blog is now more closely aligned with other Oxford University Press websites so you will have a consistent experience moving from one site to the next. We have tested to ensure the website appears properly on different browsers and devices. (If you are having problems, please update to the latest version of your browser.)

We are still working out a few kinks from this initial launch, and we will continue to update the blog, our RSS feeds, and e-newletters over the coming months and years as technology and readership evolves.

What hasn’t changed? We will continue to publish the same quality scholarship from authors, editors, and academics around the globe.

Thank you to our designers and developers at Electric Studio, and the invaluable input from staff at Oxford University Press. We welcome feedback from our readers on the design and hope to integrate your suggestions in future. Please leave a comment below.

Thank you!

The post Introducing the new OUPblog appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 questions for Garnette CadoganCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?Challenges facing UK law students

Related Stories10 questions for Garnette CadoganCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?Challenges facing UK law students

10 questions for Garnette Cadogan

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 19 August 2014, Garnette Cadogan, freelance writer and co-editor of the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of the Harlem Renaissance, leads a discussion on Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.

What was your inspiration for working on the Oxford Handbook of the Harlem Renaissance?

I kept encountering the influence of the Harlem Renaissance — on art, music, literature, dance, and politics, among other spheres – and longed for a fresh, interesting discussion of the Renaissance in its splendid variety. My close friend and colleague Shirley Thompson, who teaches at UT-Austin, often discussed with me the enormous accomplishments and rich legacies of that movement. So, when she invited me to help her bring together myriad voices to talk about central cultural, intellectual, and political figures and ideas of the Harlem Renaissance, I, of course, gleefully joined her to arrange The Oxford Handbook of the Harlem Renaissance.

Where do you do your best writing?

On the kitchen counter. The comfort of the kitchen is like nowhere else, nothing else. (Look where everyone gathers at your next house party). To boot, nothing gets my mind revving like cooking. I’ll often run from skillet to keyboard shouting “Yes!”

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

No one moment — it was a multitude of taps, then a grab — but having one of my professors in college call me to ask that I read my final paper to him over the phone was a big motivator. I took it as encouragement to be a writer, though, in retrospect, I recognize that it was my strange accent and not my prose style that was the appeal.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

Someone who could handle the distractible, chatterbox me, the troublemaker who had absolutely no interest in books or learning. Someone with a love for books who led a fascinating life and could tell a good story. Why, yes, George Orwell — What a remarkable life! What remarkable work! — would hold my attention and interest.

What is your secret talent?

Remarkably creative procrastination, coupled with the ability to trick myself that I’m not procrastinating. (Sadly, no one else but me is fooled.)

What is your favorite book?

Wait, what day is it? It all depends on the day you ask me. Sometimes, even the time of day you ask. Right now, it’s The Poems of Emily Dickinson (the handsome, authoritative edition edited by R.W. Franklin). I stand by this decision for another forty-eight hours.

Who reads your first draft?

Two friends who possess the right balance of grace and brutal honesty, the journalists Eve Fairbanks and Ilan Greenberg. They know just how to knock down and lift up, especially Eve, who has almost supernatural discernment and knows exactly what to say — and, more important in the early stages, what not to say. But who really gets the first draft are my friends John Wilson, the affable sage who edits Books and Culture, and John Freeman, whose eagle eye used to edit Granta; I verbally unload on them my fugitive ideas trying to assemble into a story (poor fellas), and then wait for red, yellow, green, or detour. Without this quartet, everything I write reads like the journal entries of Cookie Monster.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

My books haven’t been published yet, but I imagine that I’ll treat them like the rest of my writing: mental detritus I avoid looking at. I’m cursed with a near-pathological ability to only see what’s wrong with my writing.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

Painful as it is to transcribe my hieroglyphics from writing pads (or concert programs and restaurant napkins), I prefer writing longhand. My second-guessing, severe, demanding, judgmental inner-editor makes it so. On a laptop, it’s cut this, change that, insert who-knows-what, and at day’s end I’m behind where I began. And yet, I never learn. I still do most of my writing on a computer.

What book are you currently reading? (And is it in print or on an e-Reader?)

I own two e-readers but never use them; I get too much enjoyment from the tactile pleasures of bound paper. I’m now reading a riveting, touching account of the thirty-three miners trapped underground in Chile four years ago, Hector Tobar’s Deep Down Dark, which is much more than the story of their survival. It’s also a story about faith and family and perseverance. Emily St. John’s novel Station Eleven is another book that intriguingly explores survival and belief and belonging. And art and culture, too. It’s partially set in a post-apocalyptic era, but without the clichés and cloying, overplayed scenarios that come with that setting. And I’ve been regularly dipping into Michael Robbins’ new book of poems, The Second Sex — smart, smart-alecky, “sonicky,” vibrantly awake to sound and meaning — not because he’s a friend, but because he’s oh-so-good. I’ll be pressing all three books on everyone I know that can read.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

The em-dash — since it allows my sentences to breathe much easier once it’s around. It’s so forgiving, too — I get to clear my throat and then be garrulous, and readers will put up with me trying have it both ways. The em-dash is both chaperone and wingman; which other punctuation mark can make that boast? Plus, it’s a looker — bold and purposeful and lean.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

Something that takes me outdoors — and in the streets — as much as possible. Anything that doesn’t require sitting at a desk with my own boring thoughts for hours. And where I get to meet lots of new people. Bike messenger, perhaps.

Image credits: (1) Bryant Park, New York. Photo by cerfon. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via cerfon Flickr. (2) Garnette Cadogan. Photo by Bart Babinski. Courtesy of Garnette Cadogan.

The post 10 questions for Garnette Cadogan appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 questions for Ammon Shea10 questions for Jenny DavidsonFive questions for Rebecca Mead

Related Stories10 questions for Ammon Shea10 questions for Jenny DavidsonFive questions for Rebecca Mead

Can changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?

In the 1990s, policing in major US cities was transformed. Some cities embraced the strategy of “community policing” under which officers developed working relationships with members of their local communities on the belief that doing so would change the neighborhood conditions that give rise to crime. Other cities pursued a strategy of “order maintenance” in which officers strictly enforced minor offenses on the theory that restoring public order would avert more serious crimes. Numerous scholars have examined and debated the efficacy of these approaches.

A companion concept, called “community prosecution,” seeks to transform the work of local district attorneys in ways analogous to how community policing changed the work of big-city cops. Prosecutors in numerous jurisdictions have embraced the strategy. Indeed, Attorney General Eric Holder was an early adopter of the strategy when he was US Attorney for the District of Columbia in the mid-1990s. Yet, community prosecution has not received the level of public attention or academic scrutiny that community policing has.

A possible reason for community prosecution’s lower profile is the difficulty of defining it. Community prosecution contrasts with the traditional model of a local prosecutor, which is sometimes called the “case processor” approach. In the traditional model, police provide a continuous flow of cases to the prosecutor, and she prioritizes some cases for prosecution and declines others. The prosecutor secures guilty pleas in most of the pursued cases, often through plea bargains, and trials are rare. The signature feature of the traditional prosecutor’s work is quickly resolving or processing a large volume of cases.

Community prosecution breaks with the traditional paradigm and changes the work of prosecutors in several ways. It removes prosecutors from the central courthouse and relocates them to a small office in a neighborhood, often in a retail storefront. This permits the prosecutor to develop relationships with community groups and individual residents, even allowing residents to walk into the prosecutor’s office and express concerns. It frees the prosecutors from responsibility for managing the flow of cases supplied by police and allows them to undertake two main tasks. The first is that prosecutors partner with community members to identify the sources of crime within the neighborhood and formulate solutions that will prevent crime before it occurs. The second is that when community prosecutors seek to impose criminal punishments, they develop their own cases rather than rely on those presented by police, and they typically focus on the cases they anticipate will have the greatest positive impact on the local community.

In the past fifteen years, Chicago, Illinois, has had a unique experience with community prosecution that allowed the first examination of its impact on crime rates. The State’s Attorney in Cook County (in which Chicago is located), opened four community prosecution offices between 1998 and 2000. Each of these offices had responsibility for applying the community prosecution approach to a target neighborhood in Chicago, and collectively, about 38% of Chicago’s population resided in a target neighborhood. Other parts of the city received no community prosecution intervention. The efforts continued until early 2007, when a budget crisis compelled the closure of these offices and the cessation of the county’s community prosecution program. For more than two years, Chicago had no community prosecution program. In 2009, a new State’s Attorney re-launched the program, and during the next three years, the four community prosecution offices were re-opened.

Window of an apartment block at night. © bartosz_zakrzewski via iStockphoto.

Window of an apartment block at night. © bartosz_zakrzewski via iStockphoto.This sequence of events provided an opportunity to evaluate the impact of community prosecution on crime. The first adoption of community prosecution in the late 1990s lent itself to differences-in-differences estimation. The application of community prosecution to four sets of neighborhoods, each beginning at four different dates, enabled comparisons of crime rates before and after the program’s implementation within those neighborhoods. The fact that other neighborhoods received no intervention permitted these comparisons to drawn relative to the crime rates in a control group. Furthermore, Chicago’s singular experience with community prosecution – its launch, cancellation, and re-launch – furnished a sequence of three policy transitions (off to on, on to off again, and off again to on again). By contrast, the typical policy analysis observes only one policy transition (commonly from off to on). These multiple rounds of program application enhanced the opportunity to detect whether community prosecution affected public safety.

The estimates from this differences-in-differences approach showed that community prosecution reduced crime in Chicago. The declines in violent crime were large and statistically significant. For example, the estimates imply that aggravated assaults fell by 7% following the activation of community prosecution in a neighborhood. The estimates for property crime also showed declines, but they were too imprecisely estimated to permit firm statistical inferences. These results are the first evidence that community prosecution can produce reductions in crime and that the reductions are sizable.

Moreover, there was no indication that community prosecution simply displaced crime, moving it from one neighborhood to another. Neighborhoods just over the border of each community prosecution target area experienced no change in their average rates of crime. The declines thus appeared to reflect a true reduction instead of a reallocation of crime. In addition, the drops in offending were immediate and sustained. One might expect responses in crime rates would arrive slowly and gain momentum over time as prosecutors’ relationships with the community grew. But the estimates instead suggest that community prosecutors were able to identify and exploit immediately opportunities to improve public safety.

This evaluation of the community prosecution in Chicago offers broad lessons about the role of prosecutors. As with any empirical study, some caveats apply. The highly decentralized and flexible nature of community prosecution forbids reducing the program to a fixed set of principles and steps that can be readily implemented elsewhere. To the degree that its success depends on bonds of trust between prosecutor and community, its success may hinge on the personality and talents of specific prosecutors. (Indeed, the article’s estimates show variation in the estimated impacts across offices within Chicago.) At minimum, the results demonstrate that, under circumstances that require more study, community prosecution can reduce crime.

More broadly, the estimates suggest that the role of prosecutors is more far-reaching than typically thought. Crime control is conventionally understood to be primarily the responsibility of police. It was for this very reason that in the 1990s so much attention was devoted to the cities’ choice of policing style – community policing or order maintenance. Restructuring the work of police was thought to be a key mechanism through which crime could be reduced. By contrast, a conventional view of prosecutors is that their responsibilities pertain to the selection of cases, adjudication in the courtroom, and striking plea bargains. This article’s estimates show that this view is unduly narrow. Just as altering the structure and tasks of police may affect crime, so too can changing how prosecutors perform their work.

The post Can changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe First World War and the development of international lawMiles Davis’s Kind of BluePublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journal

Related StoriesThe First World War and the development of international lawMiles Davis’s Kind of BluePublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journal

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers