Oxford University Press's Blog, page 793

July 5, 2014

What test should the family courts use to resolve pet custody disputes?

This is my dog Charlie. Like many pet owners in England and Wales I see my dog as a member of my family. He shares the ups and downs of my family life and is always there for me. But what many people don’t realise is that Charlie, like all pets, is a legal ‘thing’. He falls into the same category as my sofa. The law distinguishes between legal persons and legal things and Charlie is a legal thing and is therefore owned as personal property. If my husband and I divorce and both want to keep Charlie, our dispute over where Charlie will live would come within the financial provision proceedings in the family courts. What approach will the family courts take to resolve this dispute? It is likely that the courts will adopt a property law test and give Charlie to the person who has a better claim to the property title. This can be evidenced by whose name appears on the adoption certificate from the local dogs home or who pays the food and veterinary bills. Applying a property test could mean that if my husband had a better property claim, Charlie would live with him even if Charlie is at risk of being mistreated or neglected.

Charlie the dog. Photo courtesy of Deborah Rook

Property versus welfare

Case law from the United States shows that two distinct tests have emerged to resolving pet custody disputes: firstly, the application of pure property law principles as discussed above; and secondly, the application of a ‘best interests of the animal’ test which has similarities to the ‘best interests of the child’ test used in many countries to determine the residency of children in disputes between parents. On the whole, the courts in the United States have used the property law test and rejected the ‘best interest of the animal’ test. However, in a growing number of cases the courts have been reluctant to rely solely on property law principles. For example, there are cases where one party is given ownership of the dog, having a better claim to title, but the other is awarded visitation rights to allow them to visit. There is no other type of property for which an award of visitation rights has been given. In another case the dog was given to the husband even though the wife had a better claim to title on the basis that the dog was at risk of severe injury from other dogs living at the wife’s new home.

Pets as sentient and living property

What the US cases show is that there is a willingness on the part of the courts to recognise the unique nature of this property as living and sentient. A sentient being has the ability to experience pleasure and pain. I use the terminology ‘pet custody disputes’ as opposed to ‘pet ownership disputes’ because it better acknowledges the nature of pets as living and sentient property. There are important consequences that flow from this recognition. Firstly, as a sentient being this type of property has ‘interests’, for example, the interest in not being treated cruelly. In child law, the interest in avoiding physical injury is so fundamental that in any question concerning the residency of a child this interest will prevail and a child will never be knowingly placed with a parent that poses a danger to the child. A pet is capable of suffering pain and has a similar relationship of dependence and vulnerability with its owners to that which a child has with its parents. Society has deemed the interest a pet has in avoiding unnecessary suffering as so important as to be worthy of legislation to criminalise the act of cruelty. There is a strong case for arguing that this interest in avoiding physical harm should be taken into account when deciding the residency of a family pet and should take precedence, where appropriate, over the right of an owner to possession of their property. This would be a small, but significant, step to recognising the status of pets at law: property but a unique type of property that requires special treatment. Secondly, strong emotional bonds can develop between the property and its owner. It is the irreplaceability of this special relationship that means that the dispute can’t be resolved by simply buying another pet of the same breed and type. This special relationship should be a relevant consideration in resolving the future residency of the pet and in some cases may prevail over pure property law considerations.

I argue that the unique nature of this property — the fact that it has an interest in not suffering pain and the fact that it has an ability to form special relationships — requires the adoption of a test unique to pet custody disputes: one that fits within the existing property category but nevertheless recognises the special nature of this living and sentient property and consequently permits consideration of factors that do not normally apply to other types of property in family law disputes.

Deborah Rook is a Principal lecturer in Law at the School of Law, Northumbria University and specialises in animal law. She is the author of ‘Who Gets Charlie? The Emergence of Pet Custody Disputes in Family Law: Adapting Theoretical Tools from Child Law’ (available to read for free for a limited time) in the International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family.

The subject matter of the International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family comprises the following: analyses of the law relating to the family which carry an interest beyond the jurisdiction dealt with, or which are of a comparative nature; theoretical analyses of family law; sociological literature concerning the family and legal policy; social policy literature of special interest to law and the family; and literature in related disciplines (medicine, psychology, demography) of special relevance to family law and research findings in the above areas.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What test should the family courts use to resolve pet custody disputes? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorshipHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityPsychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide

Related StoriesThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorshipHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityPsychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide

July 4, 2014

Rhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of July

Ever since 4 July 1777 when citizens of Philadelphia celebrated the first anniversary of American independence with a fireworks display, the “rockets’ red glare” has lent a military tinge to this national holiday. But the explosive aspect of the patriots’ resistance was the incendiary propaganda that they spread across the thirteen colonies.

Sam Adams understood the need for a lively barrage of public relations and spin. “We cannot make Events; Our Business is merely to improve them,” he said. Exaggeration was just one of the tricks in the rhetorical arsenal that rebel publicists used to “improve” events. Their satires, lampoons, and exposés amounted to a guerilla war—waged in print—against the Crown.

Cover of Common Sense, the pamphlet. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

While Independence Day is about commemorating the “self-evident truths” of the Declaration of Independence, the path toward separation from England relied on a steady stream of lies, rumor, and accusation. As Philip Freneau, the foremost poet-propagandist of the Revolution put it, if an American “prints some lies, his lies excuse” because the important consideration, indeed perhaps the final consideration, was not veracity but the dissemination of inflammatory material.In place of measured discourse and rational debate, the pyrotechnics of the moment suited “the American crisis”—to invoke the title of Tom Paine’s follow-up to Common Sense—that left little time for polite expression or logical proofs. Propaganda requires speed, not reflection.

Writing became a rushed job. Pamphlets such as Tom Paine’s had an intentionally short fuse. Common Sense says little that’s new about natural rights or government. But what was innovative was the popular rhetorical strategy Paine used to convey those ideas. “As well can the lover forgive the ravisher of his mistress, as the continent forgive the murders of Britain,” he wrote, playing upon the sensational language found in popular seduction novels of the day.

The tenor of patriotic discourse regularly ran toward ribald phrasing. When composing newspaper verses about King George, Freneau took particular delight in rhyming “despot” with “pisspot.” Hardly the lofty stuff associated with reason and powdered wigs, this language better evokes the juvenile humor of The Daily Show.

The skyrockets that will be “bursting in air” this Fourth of July are a vivid reminder of the rhetorical fireworks that galvanized support for the colonists’ bid for independence. The spread of political ideas, whether in a yellowing pamphlet or on Comedy Central, remains a vital part of our national heritage.

Russ Castronovo teaches English and American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His most recent book is Propaganda 1776: Secrets, Leaks, and Revolutionary Communications.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Rhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of July appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

1776, the First Founding, and America’s past in the present

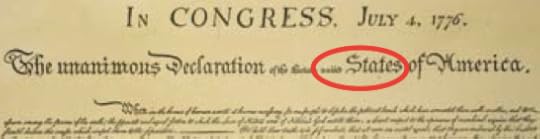

When a nation chooses to celebrate the date of its birth is a decision of paramount significance. Indeed, it is a decision of unparalleled importance for the world’s “First New Nation,” the United States, because it was the first nation to self-consciously write itself into existence with a written Constitution. But a stubborn fact stands out here. This new nation was created in 1787, and the Fourth of July that Americans celebrate today occurred on a different summer eleven years before.

The united States (capitalization, as can be found in the Declaration of Independence, is advised) declared themselves independent on 4 July 1776, but the nation was not yet to be. An act of severance did not a nation make. These united States would only become the United States when the idea of a collective We the People was negotiated and formally set on parchment in the sweltering summer of 1787. This means that while every American celebrates the revolution against government every July 4th, pro-government liberals do not quite have an equivalent red-letter day to celebrate and to mark the equally auspicious revolution in favor of government that transpired in 1787. Perhaps this is why the United States remains exceptional among all developed countries in her half-hearted attitude toward positive liberty, the welfare state, and government regulation on the one hand, and her seeming addiction to guns, individual rights, and negative liberty, on the other. In part because the nation’s greatest national holiday was selected to commemorate severance and not consolidation, (at least half of) America remains frozen in the euphoric tide of the 1770s rather than the more pragmatic, nation-building impulse of the 1780s.

The Fourth of July was only Act One of the creation of the American republic. In the interim years before the nation’s elders (the imprecise but popular nomenclature is “founders”) came together again—this time not to address the curse of the royal yolk, but to discuss the more mundane post-revolutionary crises of interstate conflict especially in matters of trade and debt repayment—the states came to realize that the threat to liberty comes not always from on high by way of royal governors, but also sideways courtesy of newfound friends. In the mid-1780s, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and their compatriots came together to design a more perfect union: a union with the power to lay and collect taxes, to raise and support armies, and an executive to wage war. This was Act Two, or the Second American Founding.

Custom and the convenience of having a bank holiday during the summer when the kids are out of school has hidden the reality of the Two Foundings. We now refer to a single founding, and a set of founders, but this does great injustice to the rich experiential tapestry that helped forge the United States. It denies the very substantive philosophic reasons for why one half of America is so convinced that liberty consists in rejecting government, but one half also thinks that flogging that dead horse with the King long slain seems needlessly self-defeating. As Turgot, the Abbé de Mably, put it in a letter to Dr. Richard Price in 1778, “by striving to prevent imaginary dangers, they have created real ones.” To many Europeans, that the citizens of United States have devoted so much energy—waging even a Civil War—against its own central government and fortifying themselves against it indicates a revolutionary nation in arrested development; a self-contradictory denial that the government of We the People is of, by, and for us.

The United States is thoroughly and still vividly ensconced in the original dilemma of civil society today, whether liberty is best achieved with government or without it. Conservatives and liberals are each so sure that they are the true inheritors of the “founding” because they can point to, respectively, the principles of the First and the Second Foundings to corroborate their account of history. And they will continue to do so for as long as the sacred texts of each of the Two Foundings, the Declaration and the Constitution, stand side by side, seemingly at peace with the other, but in effect in mutual tension.

This Fourth of July, Americans should not despair that the country seems so fundamentally divided on issues from healthcare to Iraq. For if to love is divine, to quarrel is American; and we have been having at it for over two centuries.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and is the author of The Lovers’ Quarrel: The Two Foundings and American Political Development and The Anti-Intellectual Presidency. He blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 1776, the First Founding, and America’s past in the present appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

Calvin Coolidge, unlikely US President

The Fourth of July is a special day for Americans, even for our presidents. Three presidents — John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe — died on the Fourth of July, but only one — Calvin Coolidge — was born on that day (in 1872). Interestingly, Coolidge was perhaps the least likely of any of these to have attained the nation’s highest elective office. He was painfully shy, and he preferred books to people. Nonetheless, he successfully pursued a life in politics, becoming Governor of Massachusetts followed by two years as Warren Harding’s Vice-President. When Harding died of a heart attack, Coolidge became an unlikely president. Perhaps even more unlikely, he became not only an enormously popular one, but also the one whom Ronald Reagan claimed as a model.

Helen Keller with Calvin Coolidge, 1926. National Photo Company Collection. Public domain via Library of Congress.

Coolidge faced more than the usual challenge vice-presidents face when they have ascended to the presidency upon the death of an incumbent. They have not been elected to the presidency in their own right and must somehow secure the support of the American people and other national leaders on a basis other than their own election. Coolidge surprisingly handled this challenge well through his humility, quirky sense of humor, and, perhaps most importantly, integrity. Upon becoming president, Coolidge inherited one of the worst scandals ever to face a chief executive. He quickly agreed to the appointment of two special counsel charged with investigating the corruption with his administration and vowed to support their investigation, regardless of where it lead. Coolidge kept his word, clearing out of the administration any and all of the corruption uncovered within the administration, including removing Harding’s Attorney General. He went further to become the first president to hold as well as to broadcast regular press conferences. His actions won widespread acclaim and eased the way to Coolidge’s easy victory in the 1924 presidential election.Over the course of his presidency, Coolidge either took or approved several initiatives, which have endured and changed the nature of the federal government. He was the first president to authorize federal regulation of aviation and broadcasting. He also signed into law the largest disaster relief authorized by the federal government until Hurricane Katrina. Moreover, he supported the creation of both the World Court and a pact, which sought (ultimately in vain) to outlaw war. Along the way, he became infamous for a razor-sharp sense of humor and peculiar commitment to saying as little as possible (in spite of his constant interaction with the press) and advocating as little regulation of business as possible. His administration became synonymous with the notion that the government that governs best governs least.

Coolidge, nonetheless, has become largely forgotten, partly because of his own choices and partly because of circumstances beyond his control. Just before his reelection, his beloved son died from blood poisoning originating from a blister on his foot. Coolidge never recovered and the presidency lost its luster. By 1928, he had no interest in running again for the presidency or in helping his Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover succeed him in office.

Despite the successes he had in office, including his popularity, Coolidge paid little attention to racial problems and growing poverty during era. When the Great Depression hit, the nation and particularly the next president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, construed it as a reflection of the failed policies and foresight of both Hoover and his predecessor. Despondent over his son’s death, Coolidge did little to protect his legacy and respond to critics throughout the remainder of Hoover’s term. When he died shortly before Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration, he was largely dismissed or forgotten as a president whose time had come and gone. Nevertheless, on this Fourth of July, do not forget that when conservative leaders deride the growth of the federal government and proclaim the need for less regulation, they harken back not only to President Reagan but also to the man whom Reagan regarded as the model of a conservative leader. Calvin Coolidge’s birthday is as good a time as any to remember that his ideals are alive and well in America.

Michael Gerhardt is Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published five books, including The Forgotten Presidents and The Power of Precedent. Read his previous blog posts on the American presidents.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Calvin Coolidge, unlikely US President appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyWhat can poetry teach us about war?Mapping the American Revolution

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyWhat can poetry teach us about war?Mapping the American Revolution

What if the Fourth of July were dry?

In 1855, the good citizens of the state of New York faced this very prospect. Since the birth of the republic, alcohol and Independence Day have gone hand in hand, and in the early nineteenth century alcohol went hand in hand with every day. Americans living then downed an average seven gallons of alcohol per year, more than twice what Americans drink now. In homes and workshops, churches and taverns; at barn-raisings, funerals, the ballot box; and even while giving birth — they lubricated their lives with ardent spirits morning, noon, and night. If there was an annual apex in this prolonged cultural bender, it was the Fourth of July, when many commemorated the glories of independence with drunken revelry.

Beginning in the 1820s, things began to change. A rising lot of middle-class evangelical Protestants hoped to banish the bottle not only from the nation’s birthday but from the nation itself. With the evidence of alcohol’s immense personal and social costs before them, millions of men and women joined the temperance crusade and made it one of America’s first grass-roots social movements. Reformers demonized booze and made “teetotalism” (what we call abstinence) a marker of moral respectability. As consumption levels began to fall by mid-century, activists sought to seal their reformation with powerful state laws prohibiting the sale of alcohol. They insisted — in true democratic fashion — that an overwhelming majority of citizens were ready for a dry America.

State legislators played along, initiating America’s first experiment with prohibition not in the well-remembered 1920s but rather in the 1850s. It was a time when another moral question — slavery — divided the nation, but it was also a time when hard-drinking Irish and German immigrants — millions of them Catholics — threatened to overwhelm Protestant America. With nativism in the air, 13 states enacted prohibition laws. Predicting the death of alcohol and the salvation of the nation, temperance reformers set out to see these laws enforced.

New York’s moment came in 1855. The state legislature passed a prohibition statute in the spring and chose the Fourth of July for the measure to take effect. If prohibition was going to work, it had to work on the wettest day of the year. The bold timing was not lost on contemporaries who imagined the “sensation” that would undoubtedly accompany a dry Independence Day. “Cannon will have a novel sound in the ears of some people” and “flags will have a curious look to some eyes,” the prohibitionist New York Times jibbed. American eyes and ears, of course, had long been impaired by “brandy smashes” and “gin slings.” But now a proper, sober celebration of the nation’s birth could proceed without alcohol’s irreverent influence.

Laborers dispose of liquor during Prohibition. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A stiff cocktail of workingmen and entrepreneurs, immigrants, and native-born Americans, however, burst on to the scene to keep the Fourth of July, and every day thereafter, wet. These anti-prohibitionists condemned prohibition as an affront to their cultural traditions and livelihoods. To them, prohibition exposed the grave threat that organized moral reform and invasive state governments posed to personal liberty and property rights. It revealed American democracy’s despotic tendencies — what anti-prohibitionists repeatedly called the “tyranny of the majority.” Considering themselves an oppressed minority, liquor dealers, hotel keepers, brewers, distillers, and other alcohol-purveying businessmen led America’s first wet crusade. In the process, they became critical pioneers in America’s lasting tradition of popular minority-rights politics. As the Fourth of July approached, they initiated opinion campaigns, using mass meetings and the press to bombard the public with anti-prohibitionist propaganda that placed minority rights and constitutional freedom at the heart of America’s democratic experiment. They formed special “liquor dealer associations” and used them to raise funds, lobby politicos, hire attorneys, and determine a course of resistance once prohibition took effect.

In some locales their public-opinion campaigns worked as skittish officials refused to enforce the law. As the New York Times grudgingly observed of the Fourth of July in Manhattan, “The law was in no respect observed.” But elsewhere, officials threatened enforcement and reports of a dry Fourth circulated. In Yonkers, for example, there wasn’t “a drop of liquor to be had.” With prohibition enforced in Brooklyn, Buffalo, and elsewhere, anti-prohibitionists implemented their plan of civil disobedience — intentionally and peacefully resisting a law that they deemed unjust and morally reprehensible. They defiantly sold booze and hoped to be arrested so they could “test” prohibition’s constitutionality in court. Liquor dealer associations organized these efforts and guaranteed members access to their legal defense funds to cover the costs of fines and litigation. The battle had fully commenced.

In New York, as in other states, anti-prohibitionists’ activism paid off. Their efforts soon turned prohibition into a dead letter throughout the state, and they convinced New York’s Court of Appeals to declare prohibition unconstitutional. The Fourth of July had been a dry affair in many New York towns in 1855, but anti-prohibitionists ensured that the national birthday in 1856 was a wet one. Their temperance adversaries, of course, would persist and emerge victorious when national Prohibition in the form of the 18th Amendment took full effect in 1920. But anti-prohibitionists continued to counter with tactics intended to protect civil liberties and minority rights in America’s democracy. That Independence Day today remains a wet affair owes much to their resistance and to the brand of minority-rights politics they popularized in the mid-nineteenth century.

Kyle G. Volk is Associate Professor of History at the University of Montana. He is author of Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy, recently published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What if the Fourth of July were dry? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

The July effect

“Don’t get sick in July.”

So the old adage goes. For generations medical educators have uttered this exhortation, based on a perceived increase in the incidence of medical and surgical errors and complications occurring at this time of year, owing to the influx of new medical graduates (interns) into residency programs at teaching hospitals. This phenomenon is known as the “July effect.”

So the old adage goes. For generations medical educators have uttered this exhortation, based on a perceived increase in the incidence of medical and surgical errors and complications occurring at this time of year, owing to the influx of new medical graduates (interns) into residency programs at teaching hospitals. This phenomenon is known as the “July effect.”

The existence of a July effect is highly plausible. In late June and early July of each year, all interns and residents (physicians in training beyond the internship) are at their most inexperienced. Interns—newly minted MDs fresh out of medical school—have nascent clinical skills. Most interns also have to learn how a new hospital system operates since most of them enter residency programs at hospitals other than the ones they trained at as medical students. At the same time the previous year’s interns and residents take a step up on the training ladder, assuming new duties and responsibilities. Every trainee is in a position of new and increased responsibilities. The widespread concern that these circumstances lead to mistakes is understandable.

Yet, despite considerable consternation, evidence that there is a July effect is surprisingly hard to come by. Numerous studies of medical and surgical trainees have demonstrated no increase in errors or complications in July compared with other times of the year. Many commentators have declared the July effect a myth, or at least highly exaggerated. A few studies have shown the existence of a July effect, but only a slight one—for instance, on the sickest group of heart patients, where even a slight, seemingly inconsequential mistake can have grave consequences. Even here, however, the magnitude of the effect does not appear large, and the studies are highly flawed. Certainly, there is no reason for individuals to avoid seeking medical care in July should they become ill.

That the July effect is so difficult to demonstrate is a tribute to our country’s system of graduate medical education. Every house officer (the generic term for intern and resident) is supervised in his or her work by someone more experienced, even if only a year or two farther along. Faculty members commonly provide more intense supervision in July than at other times of the year. Recent changes in residency training, such as shortening the work hours of house officers and providing them more help with chores, may also help make residency training safer for patients—in July, and throughout the year.

Uncertainty is intrinsic to medical practice. Medical and surgical care, no matter how skillfully executed, inevitably involves risks. It would not be surprising if a small July effect at teaching hospitals does occur, particularly in certain subgroups of critically ill or vulnerable patients, given that house officers are the least experienced. However, the fact that this effect, if present, is small and difficult to measure provides testimony to the strength of graduate medical education in the United States. Indeed, the quality of care at teaching hospitals has consistently been shown to be better than at hospitals without interns and residents. Patients may be assured that their interests will be served at teaching hospitals—in July, and throughout the year.

Kenneth M. Ludmerer is Professor of Medicine and the Mabel Dorn Reeder Distinguished Professor of the History of Medicine at the Washington University School of Medicine. He is the author of Let Me Heal: The Opportunity to Preserve Excellence in American Medicine, Time to Heal: American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care, and Learning to Heal: The Development of American Medical Education.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Multiracial medical students wearing lab coats studying in classroom. Photo by goldenKB, iStockphoto.

The post The July effect appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImprove organizational well-being and prevent workplace abuseUnravelling the enigma of chronic pain and its treatmentHow to prevent workplace cancer

Related StoriesImprove organizational well-being and prevent workplace abuseUnravelling the enigma of chronic pain and its treatmentHow to prevent workplace cancer

Killing me softly: rethinking lethal injection

By Aidan O’Donnell

How hard is it to execute someone humanely? Much harder than you might think. In the United States, lethal injection is the commonest method. It is considered humane because it is painless, and the obvious violence and brutality inherent in alternative methods (electrocution, hanging, firing squad) is absent. But when convicted murderer Clayton Lockett was put to death by lethal injection in the evening of 29 April 2014 by the Oklahoma Department of Corrections, just about everything went wrong.

Executing someone humanely requires considerable skill and training. First, there needs to be skill in securing venous access. Some condemned prisoners have a history of intravenous drug use, which obliterates the superficial, easy-to-reach veins, necessitating the use of a deeper one such as the femoral or jugular. Lockett was examined by a phlebotomist—almost certainly not a doctor—who searched for a vein in his arms and legs, but without success. The phlebotomist considered Lockett’s neck, before resorting to the femoral vein in his groin.

Second, there needs to be skill in administration of lethal drugs. The traditional triad of drugs chosen for lethal injection incorporates several “safeguards”. The first drug, thiopental, is a general anaesthetic, intended to produce profound unconsciousness, rendering the victim unaware of any suffering. The second drug, pancuronium, paralyses the victim’s muscles, so that he would die of asphyxia in the absence of any further intervention. However, the third drug, potassium chloride, effectively stops the heart before this happens. All three drugs are given in substantial overdose, so that there is no likelihood of survival, and the dose of any single one would likely be lethal. When used as intended, the victim enters deep general anaesthesia before his life is extinguished, and the whole process takes about five minutes.

Thiopental and pancuronium are older drugs, no longer available in the United States. US manufacturers have refused to produce them for use in lethal injection, and European manufacturers have refused to supply them. This has forced authorities to use other drugs with similar properties in untested doses and combinations.

Lockett was given 100mg of the sedative midazolam, intended to render him unconscious. Witnesses were warned that this execution might take longer than expected because midazolam acts more slowly than thiopental. Lockett appeared to be still conscious seven minutes later; nonetheless, three minutes after this, he was declared unconscious by a prison doctor. Vecuronium (a similar drug to pancuronium) was then administered to paralyse him, followed by potassium to stop his heart.

Journalist Katie Fretland, who was present at the execution, wrote that Lockett “lurched forward against his restraints, writhing and attempting to speak. He strained and struggled violently, his body twisting, and his head reaching up from the gurney” and uttered the word “Man”.

How can you tell if someone is unconscious? Though it is not clear what criteria the prison used to determine Lockett’s level of consciousness, the tool most widely used is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Developed in 1974 by Teasdale and Jennett, the GCS recognises something fundamental: consciousness is not a binary state, on or off. Instead, it is more like a dimmer switch, on a continuum from fully alert to profoundly unresponsive.

The GCS uses three simple observations: the subject’s best movement response, his best eye-opening response, and his best vocal response. A fully-conscious subject scores 15. Someone under general anaesthesia scores the minimum score of 3– one cannot score zero—and this is the score which I would expect Lockett to have after 100mg of midazolam. From the reports, we can infer that Lockett’s score was much higher; it was at least 8. It should never have been above 3.

The prison doctor determined that the intravenous line was not correctly located in Lockett’s vein, and that the injected drugs were not being delivered into his bloodstream, but instead into the tissues of his groin, where they would be absorbed into his system much more slowly.

Despite a decision to halt the execution attempt, Lockett was pronounced dead 43 minutes after the first administration of midazolam. It was widely reported that he died of a “heart attack”, but this is a very imprecise term. I surmise Lockett suffered a cardiac arrest, brought on by the gradual action of the lethal drugs. During those 43 minutes, Lockett was likely to be partly conscious, slowly suffocating as his muscles became too weak to breathe, and his heart was slowly poisoned by the potassium. How much of this he was aware of is impossible to estimate.

As an anaesthetic specialist, I am trained and skilful at establishing venous access in the most difficult patients. I am intimately familiar with all of the drugs which might reasonably be used, and I spend my professional life judging the level of consciousness of other people. I would seem to be an ideal person to perform judicial execution.

However, I never will. First, I consider judicial execution morally unacceptable. Second, it is profoundly unpalatable to me that the drugs I use for the relief of pain and suffering can be misused for execution. Third, I live in a country where execution is illegal. However, even if I lived in the United States, the American Medical Association explicitly and in detail forbids doctors to be involved (however tangentially) in judicial execution, leading me to question the involvement of doctors in Lockett’s execution.

Different authorities in the United States are executing prisoners using a variety of drugs in combinations and doses which are untested, and not subject to official approval. Of course, as soon as official approval for a particular regime is granted, suppliers will move to restrict the supply of those drugs for execution, and this cycle will begin again. Drain cleaner would work fine; will they go that far?

Lockett’s bungled execution should prompt us to consider some fundamental questions about lethal injection: Who should be involved? What training should they have? What drugs should they use? Where should they come from? And the most important question of all: isn’t it time the United States stopped this expensive and unreliable practice?

Aidan O’Donnell is a consultant anaesthetist and medical writer with a special interest in anaesthesia for childbirth. He graduated from Edinburgh in 1996 and trained in Scotland and New Zealand. He now lives and works in New Zealand. He was admitted as a Fellow of the Royal College of Anaesthetists in 2002 and a Fellow of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists in 2011. Anaesthesia: A Very Short Introduction is his first book.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Lethal injection room, by the Californian State of Corrections and Rehabilitation. CC-PD-MARK by Wikimedia Commons.

The post Killing me softly: rethinking lethal injection appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesApples and carrots count as wellMorality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia lawImprove organizational well-being and prevent workplace abuse

Related StoriesApples and carrots count as wellMorality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia lawImprove organizational well-being and prevent workplace abuse

July 3, 2014

Gods and men in The Iliad and The Odyssey

The Ancient Greek gods are all the things that humans are — full of emotions, constantly making mistakes — with the exception of their immortality. It makes their lives and actions often comical or superficial — a sharp contrast to the humans that are often at their mercy. The gods can show their favor, or displeasure; men and women are puppets in their world. Barry B. Powell, author of a new free verse translation of Homer’s The Odyssey, examines the gods, fate, divine interventions, and what it means in the classic epic poem.

Fate and free in The Iliad and The Odyssey

Click here to view the embedded video.

What role do the Gods play in The Iliad and The Odyssey?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Who is Hercules and how does he play a role in The Odyssey?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Greek Gods versus modern omnibenevolent God

Click here to view the embedded video.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His new free verse translation of The Odyssey was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. His translation of The Iliad was published by Oxford University Press in 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Gods and men in The Iliad and The Odyssey appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA map of Odysseus’s journeyTelemachos in IthacaA Canada Day reading list

Related StoriesA map of Odysseus’s journeyTelemachos in IthacaA Canada Day reading list

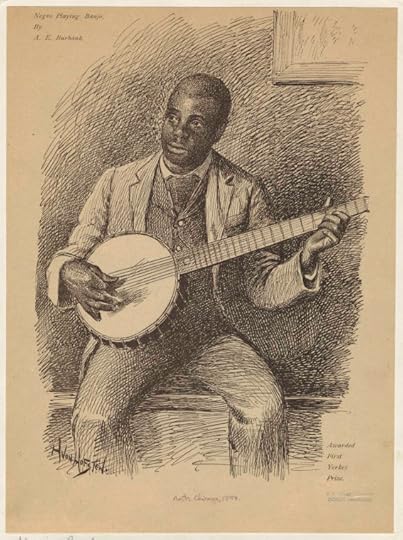

10 fun facts about the banjo

The four-, five-, six- stringed instrument that we call a “banjo” today has a fascinating history tracing back to as early as the 1600s, while precursors to the banjo appeared in West Africa long before it was in use in America. Explore these fun facts about the banjo through a journey back in time.

The banjo was in use among West African slaves since as early as the 17th century.

Recent research in West African music shows more than 60 plucked lute instruments, all of which, to a degree, show some resemblance to the banjo, and so are likely precursors to the banjo.

The earliest evidence of plucked lutes comes from Mesopotamia around 6000 years ago.

The first definitive description of an early banjo is from a 1687 journal entry by Sir Hans Sloane, an English physician visiting Jamaica, who called this Afro-Caribbean instrument a “strum strump”.

The banjo had been referred to in 19 different spellings, from “banza” to “bonjoe” by the early 19th century.

Banjo player, 1894. NYPL Digital Collection. Image ID: 832330

The earliest reference to the banjo in North America appeared in John Peter Zenger’s The New-York Weekly Journal in 1736.

William Boucher (1822-1899) was the earliest commercial manufacturer of banjos. The Smithsonian Institution has three of his banjos from the years 1845-7. Boucher won several medals for his violins, drums, and banjos in the 1850s.

Joel Walker Sweeney (1810-1860) was the first professional banjoist to learn directly from African Americans, and the first clearly documented white banjo player.

After the 1850s, the banjo was increasingly used in the United States and England as a genteel parlor instrument for popular music performances.

The “Jazz Age” created a new society craze for the four-string version of the banjo. Around the 1940s, the four-string banjo was being replaced by the guitar.

Sarah Rahman is a digital product marketing intern at Oxford University Press. She is currently a rising junior pursuing a degree in English literature at Hamilton College.

Oxford Reference is the home of reference publishing at Oxford. With over 16,000 photographs, maps, tables, diagrams and a quick and speedy search, Oxford Reference saves you time while enhancing and complementing your work.

Subscribe to OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 10 fun facts about the banjo appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGetting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann WilhoiteScoring independent film musicSongs of the Alaskan Inuit

Related StoriesGetting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann WilhoiteScoring independent film musicSongs of the Alaskan Inuit

July 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertainty

There’s not much history in our holidays these days. For most Americans, they’re vehicles of leisure more than remembrance. Labor Day means barbecues; Washington’s Birthday (lumped together with Lincoln’s) is observed as a presidential Day of Shopping. The origins of Memorial Day in Confederate grave decoration or Veterans Day in the First World War are far less relevant than the prospect of a day off from work or school.

Independence Day fares a little better. Most Americans understand it marks the birth of their national identity, and it’s significant enough not to be moved around to the first weekend of July (though we’re happy enough, as is the case this year, when it conveniently forms the basis of a three-day weekend). There are flags and fireworks abundantly in evidence. That said, the American Revolution is relatively remote to 21st century citizens, few of whom share ancestral ties, much less sympathy, for the views of the partisans of 1776, some of whom were avowedly pro-slavery and all of them what we would regard as woefully patriarchal.

The Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The main reason why Independence Day matters to us is that it commemorates the debut of the Declaration of Independence in American life (the document was actually approved by Congress on July 2nd; it was announced to the public two days later). Far more than any other document in American history, including the Constitution, the Declaration resonates in everyday American life. We can all cite its famous affirmation of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” because in it we sense our true birthright, the DNA to which we all relate. The Declaration gave birth to the American Dream — or perhaps I should say an American Dream. Dreams have never been the exclusive property of any individual or group of people. But never had a place been explicitly constituted to legitimate human aspiration in a new and living way. Dreams did not necessarily come true in the United States, and there were all kinds of politically imposed barriers to their realization alongside those that defied human prediction or understanding. But such has been the force of the idea that US history has been widely understood — in my experience as a high school teacher working with adolescents, instinctively so — as a progressive evolution in which barriers are removed for ever-widening concentric circles that bring new classes of citizens — slaves, women, immigrants, gays — into the fold.

This is, in 2014, our mythic history. (I use the word “myth” in the anthropological sense, as a widely held belief whose empirical reality cannot be definitively proved or denied.) But myths are not static things; they wax and wane and morph over the course of their finite lives. As with religious faith, the paradox of myths is that they’re only fully alive in the face of doubt: there’s no need to honor the prosaic fact or challenge the evident falsity. Ambiguity is the source of a myth’s power.

Here in the early 21st century, the American Dream is in a season of uncertainty. The myth does not assert that all dreams do come true, only that all dreams can come true, and for most of us the essence of can resides in a notion of equality of opportunity. We’ve never insisted on equality of condition (indeed, relatively few Americans ever had much desire for it, in stark contrast to other peoples in the age of Marx). Differential outcomes are more than fine as long as we believe it’s possible anyone can end up on top. But the conventional wisdom of our moment, from the columns of Paul Krugman to the pages of Thomas Piketty, suggests that the game is hopelessly rigged. In particular, race and class privilege seem to give insuperable advantage over those seeking to achieve upward mobility. The history of the world is full of Ciceros and Genghis Khans and Joans of Arc who improbably overcame great odds. But in the United States, such people aren’t supposed to be exceptional. They’re supposed to be almost typical.

One of the more curious aspects of our current crisis in equality of opportunity is that it isn’t unique in American history. As those pressing the point frequently observe, inequality is greater now than any time since the 1920s, and before that the late nineteenth century. Or, before that, the antebellum era: for slaves, the difference between freedom and any form of equality — now so seemingly cavernous, even antithetical — were understandably hard to discern. And yet the doubts about the legitimacy of the American Dream, always present, did not seem quite as prominent in those earlier periods as they do now. Frederick Douglass, Horatio Alger, Emma Lazarus: these were soaring voices of hope during earlier eras of inequality. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby was a cautionary tale, for sure, but the greatness of his finite accomplishments was not denied even by normally skeptical Nick Carraway. What’s different now may not be our conditions so much as our expectations. Like everything else, they have a price.

I don’t want to brush away serious concerns: it may well be that on 4 July 2014 an American Dream is dying, that we’re on a downward arc different than that of a rising power. But it is perhaps symptomatic of our condition — a condition in which economic realities are considered the only ones that matter — whereby the Dream is so closely associated with notions of wealth. We all know about the Dreams of Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg. But the American Dream was never solely, or even primarily, about money — even for Benjamin Franklin, whose cheeky subversive spirit lurks beneath his adoption as the patron saint of American capitalism. Anne Bradstreet, Thomas Jefferson, Martin Luther King: some of these people were richer than others, and all had their flaws. But none of them thought of their aspirations primarily in terms of how wealthy they became, or measured success in terms of personal gain. Their American Dreams were about their hopes for their country as a better place. If we can reconnect our aspirations to their faith, perhaps our holidays can become more active vessels of thanksgiving.

Jim Cullen is chair of the History Department of the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York. He is the author of The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation and Sensing the Past: Hollywood Stars and Historical Visions, among other books. He is currently writing a cultural history of the United States since 1945.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post July 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertainty appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMapping the American RevolutionWhat is the American Dream?Cultural memory and Canada Day: remembering and forgetting

Related StoriesMapping the American RevolutionWhat is the American Dream?Cultural memory and Canada Day: remembering and forgetting

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 237 followers