Oxford University Press's Blog, page 800

June 19, 2014

Celebrating Trans Bodies, Trans Selves

We kicked-off Pride Month early this year, celebrating the publication of Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource for the Transgender Community in late May. Taking Our Bodies, Our Selves as its model, Trans Bodies, Trans Selves is an all-encompassing resource for the transgender community and any one looking for information. Covering heath, legal, cultural and social questions, history, theory and more, the book weaves in anonymous quotes and testimonials from transgender individuals, adding hundreds of voices to share the diversity of transgender experience. Contributors, allies, friends, family members and community leaders gathered in the lobby of Oxford University Press’ New York office to fête the book. Here are some highlights from the evening.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Laura Erickson-Schroth, the editor of Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, with Dana Bliss, OUP's Senior Editor for Social Work

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Members of the Trans Bodies Board with Dana Bliss

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Copies of Trans Bodies, Trans Selves before they flew off the shelves

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Laura Erickson-Schroth, Trans Bodies Board Member Amanda Rosenblum, OUP USA President Niko Pfund and OUP's Senior Editor for Social Work Dana Bliss

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

OUP USA President Niko Pfund and actress Heather Matarazzo

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Laura Erickson-Schroth talks about the project

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The party crowd listens to speeches

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Laura Erickson-Schroth and Dana Bliss hug it out after speeches

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fiona Dawson and Landon Wilson of TransMilitary

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Party attendees and contributors with copies of the book

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Dr. Kenn Ashley, former President of the Association of Gay and Lesbian psychiatrists, Laura Erickson-Schroth, and Dr. Charles Marmar, chair of psychiatry at NYU share a moment of achievement

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

More esteemed guests..

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

...and more!

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The OUP marketing team behind the book

Laura Erickson-Schroth, MD, MA, is a psychiatry resident at New York University Medical Center. She is a board member of GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBT Equality, as well as the Association of Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists. She is a founding member of the Gender and Family Network of New York City, a group for service providers interested in the health of gender non-conforming children and adolescents. She is the editor of Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource for the Transgender Community.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social work articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Celebrating Trans Bodies, Trans Selves appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFaith and science in the natural worldFelipe VI, Spain’s new king: viva el reyWorld Cup plays to empty seats

Related StoriesFaith and science in the natural worldFelipe VI, Spain’s new king: viva el reyWorld Cup plays to empty seats

Faith and science in the natural world

There is a pressing need to re-establish a cultural narrative for science. At present we lack a public understanding of the purpose of this deeply human endeavour to understand the natural world. In debate around scientific issues, and even in the education and presentation of science itself, we tend to overemphasise the most recent findings, and project a culture of expertise.

The cost is the alienation of many people from experiencing what the older word for science, “natural philosophy” describes: the love of wisdom of natural things. Science has forgotten its story, and we need to start retelling it.

To draw out the long narrative of science, there is no substitute for getting inside practice – science as the recreation of a model of the natural world in our minds. But I have also been impressed by the way scientists resonate with very old accounts nature-writing – such as some of the Biblical ancient wisdom tradition. To take a specific example of a theme that takes very old and very new forms, the approaches to randomness and chaos are being followed today in studies of granular media (such as the deceptively complex sandpiles) and chaotic systems.

These might be thought of as simplified approaches to ‘the earthquake’ and ‘the storm’, which appear in the achingly beautiful nature poetry of the Book of Job, an ancient text also much concerned with the unpredictable side of nature. I have often suggested to scientist-colleagues that they read the catalogue of nature-questions in Job 38-40, to be met with their delight and surprise. Job’s questioning of the chaotic and destructive world becomes, after a strenuous and questioning search in which he is shown the glories of the vast cosmos, a source of hope, and a type of wisdom that builds a mutually respectful relationship with nature.

Reading this old nature-wisdom through the experience of science today indicates a fresh way into other conflicted territory. For, rather than oppose theology and science, a path that follows a continuity of narrative history is driven instead to derive what a theology of science might bring to the cultural problems of science with which we began. In partnership with a science of theology, it recognises that both, to be self-consistent, must talk about the other. Neither in conflict, nor naively complementary, their stories are intimately entangled.

Cloud to ground lightning over Sofia, by Boby Dimitrov. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The strong motif that is the idea of science as the reconciliation of a broken human relationship with nature. Science has the potential to replace ignorance and fear of a world that can harm us and that we also can harm, by a relationship of understanding and care. The foolishness of thoughtless exploitation can be replaced by the wisdom of engagement. This is neither a ‘technical fix’, nor a ‘withdrawal from the wild’, two equally unworkable alternatives criticised recently by Bruno Latour in a discussion of environmentalism in the 21st century.

Latour’s hunch that rediscovered religious material might point the way to a practical alternative begins to look well-founded. Nor is such ‘narrative for science’ confined to the political level; it has personal, cultural and educational consequences too that might just meet Barzun’s missing sphere of contemplation.

Can science be performative? Could it even be therapeutic?

George Steiner once wrote, “Only art can go some way towards making accessible, towards waking into some measure of communicability, the sheer inhuman otherness of matter…”

Perhaps science can do that too.

Tom McLeish is Professor of Physics and Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Research at University of Durham, and a Fellow of the Institute of Physics, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the American Physical Society and the Royal Society. He is the author of Faith and Wisdom in Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Faith and science in the natural world appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTorture: what’s race got to do with it?A thought on poets, death, and Clive James. And heroism.The decline of evangelical politics

Related StoriesTorture: what’s race got to do with it?A thought on poets, death, and Clive James. And heroism.The decline of evangelical politics

June 18, 2014

Felipe VI, Spain’s new king: viva el rey

Spain has a new king, following the abdication of King Juan Carlos earlier this month in favour of his son, Felipe VI. The move comes at a time when Spain is emerging from a long period of recession with an unemployment rate of 26%, a tarnished monarchy, a widely discredited political class, and a pro-independence movement in the region of Catalonia. Like his father almost 40 years ago when he succeeded the dictator General Franco as head of state, Felipe VI faces enormous but very different challenges.

Juan Carlos’s grandfather, King Alfonso XIII, went into exile before Spain’s 1936-39 Civil War. General Franco, who won that war, sidestepped Juan Carlos’s liberal and exiled father, Don Juan, and appointed Juan Carlos instead, believing he would maintain his regime as he had been educated in Spain under Franco’s aegis since the age of 10.

Juan Carlos knew that the only way to secure the monarchy was by piloting the transition to democracy. In 1981, when Francoist diehards tried to turn back the clock and staged a military coup, Juan Carlos faced them down and won the day. As a result, he became a hugely popular figure and many people became juancarlistas as opposed to outright monarchists. Under him, Spain joined NATO in 1982, entered the European Community in 1986, and enjoyed the longest period of stability and prosperity in its modern history.

In recent years, however, Juan Carlos and the monarchy as an institution have lost support. The king’s son-in-law, Iñaki Urdangarin, is currently embroiled in an ongoing investigation into alleged financial irregularities and tax evasion involving the misuse of public funds, which has made him persona non grata in the royal family. Urdangarin, who denies any wrongdoing, is expected to stand trial. The king also did not endear himself to his subjects at a time of national crisis by going on an elephant-hunting trip to Botswana in 2012 (for which he later publicly apologised), after saying he was losing sleep thinking about Spain’s whopping youth unemployment rate (55%). And, as part of the establishment blamed for not anticipating the country’s deep crisis, the king was perceived as part of the problem. On a scale of 0 (no confidence) to 10 (a lot of confidence), the monarchy scored 3.72 in April, down from 7.48 in 1995, according to the CIS barometer. Meanwhile, support for the restoration of a republic (established in 1931 and ended in 1939) has been growing.

Juan Carlos had always implied that he would die as king. But in addition to the scandals, his health has deteriorated over the last few years and he has been in and out of hospital for various operations. At 76, he was visibly tired and finding it an increasing strain to keep up with his duties and travel abroad promoting Spanish business.

Felipe VI, the new King of Spain.

Juan Carlos’s decision to abdicate will also smooth the path for his son, Felipe. The two main parties, the ruling conservative Popular Party (PP) and the Socialists, hold more than 80% of the seats in parliament between them, and so they were able to ensure parliamentary passage of the legislation required for the handover to Felipe.

The abdication appeared to boost support for the monarchy: almost two-thirds of respondents in a poll said they had a good or very good opinion of Juan Carlos, up from his 41% favourability rating in January, and 77% approved of his son.

The next general election is not scheduled until November 2015, and the results could change the political map substantially. The PP and the Socialists, who have dominated the political scene since 1983, gained less than 50% of the votes between them in last month’s European elections, compared to 73% in the 2011 general election. The Socialists did so poorly that their leader, Alfredo Rubalcaba, resigned. The Socialists, who governed Spain during the key modernisation period of 1983-96 and into the recession in 2009, are in a mess and run the risk of veering into populism in order to win votes.

The Izquierda Plural (Plural Left) coalition and Podemos (We can), a new radical party born out of the 2011 grass roots protest movement of Los Indignados (The Indignant Ones), both did well in the European elections. Podemos came from nowhere to win five seats and 1.2 million votes (8% of the total cast), while L’Esquerra and Los Pueblos, in favour of independence for Catalonia and the Basque Country, won three seats between them. All of these parties want a republic, as do some in the more moderate Socialist party. The king’s abdication was greeted by those who support a republic, with demonstrations calling for a referendum on whether to keep the monarchy.

Spain’s choice is not between a monarchy or a republic, but between a poor democracy or higher quality one. Moreover, changing the form of the state will not resolve the burning issues of high unemployment, a defective education system, the lopsided economic model (excessively based on the real estate sector), the potential division of the nation (fuelled by Catalonia’s push for an illegal referendum on independence this November), a politicised judiciary which operates at a snail’s pace, and corruption. Spain was ranked 40th out of 177 countries in the latest corruption perceptions ranking by the Berlin-based Transparency International, down seven places from the year before on “a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean)”. More than 1,500 corruption cases are still under investigation, many of them involving politicians.

When I met Juan Carlos in 1977, he joked about himself. “Why was I crowned in a submarine? Because deep down, I am not so stupid.” Once again, he has shown how true this is by his wise decision to pass on the baton to his son, who has been well educated and is well prepared.

The challenge for Felipe VI is to revitalise the monarchy and show that it still has a role to play in modern Spain. In such a partisan country, the restoration of the republic would be a disaster. Juan Carlos took the first step toward regaining the public’s confidence; now, the entrenched political class needs to clean up its act.

William Chislett is the author of Spain: What Everyone Needs to Know®. He is a journalist who has lived in Madrid since 1986. He covered Spain’s transition to democracy (1975-78) for The Times of London and was later the Mexico correspondent for the Financial Times (1978-84). He writes about Spain for the Elcano Royal Institute, which has published three of his books on the country, and he has a weekly column in the online newspaper, El Imparcial.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: “Felipe, Prince of Asturias” by Michał Koziczyński, CC BY-SA 3.0 PL via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Felipe VI, Spain’s new king: viva el rey appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEight facts about the gun debate in the United StatesFive reasons why Spain has a stubbornly high unemployment rate of 26%World Cup plays to empty seats

Related StoriesEight facts about the gun debate in the United StatesFive reasons why Spain has a stubbornly high unemployment rate of 26%World Cup plays to empty seats

World Cup plays to empty seats

Stunning upsets. Dramatic finishes. Individual brilliance. Goals galore. The 2014 World Cup has started off with a bang. Yet, not as many people as expected are on hand to hear and see the excitement in venues throughout Brazil. Outside of the home country’s matches, there have been thousands of empty seats in stadiums throughout the tournament. Even marquee matchups, such as the Netherlands-Spain game, have failed to fill their venues. The Italian and English football associations each had 2,500 tickets allocated for their recent game. While England sold their entire allotment, Italy was reported to have returned hundreds of tickets back to FIFA.

So why is the world’s most popular sporting event playing to empty seats? Hosting the event in Brazil does create unique structural challenges that likely have and will prevent more sellouts. Because of the billions of dollars of public funds spent on the World Cup by Brazil, FIFA allocated a large number of tickets for exclusive purchase by fans from the host nation that are paying the bill. In a country where a 10-cent price increase in bus fare caused a nation-wide protest last year, paying $135-$188 dollars per match is likely too expensive for many Brazilian soccer fans.

However, the World Cup is not alone in having difficulty filling empty seats for major sporting events. For example, the National Football League (NFL) and the Southeastern Conference (SEC) are two of the most popular sports leagues in the United States. Yet, both organizations have seen declines in attendance over the past years and are spending significant resources in addressing this venue challenge. With ticket prices continually increasing and technology making it easing than ever to watch games on your television, laptop, or phone, how do sports organizations get people to come to venues?

Arena da Amazônia – Amazon Arena (Quando ainda em construçao – When still under construction.) Photo by Gabriel Smith. CC BY 2.0 via gabriel_srsmith Flickr.

The 2014 World Cup in Brazil demonstrates many of these issues. One of the biggest place marketing challenges is the location of the stadiums. Both FIFA and Brazil essentially used the Field of Dreams “if you build it they will come” strategy. Brazil decided to build or renovate 12 stadiums in many different parts of the country, including venues in remote locations throughout the country. For example, the United States’ second game will be held in Manaus in the Amazonian jungle. The city can only be reached by boat or plane as no highways connect the city to the rest of Brazil.

Brazil could have focused on eight venues — the minimum required by FIFA to host a World Cup — in locations closer to metropolitan areas. We have found that many of the most successful venues already take advantage of existing infrastructure rather than depending on new development. It is likely that more people would attend World Cup matches if they did not have to rely on new roads, bridges, and rail lines to get there.

Brazil and FIFA have also suffered from the lack of an integrated place marketing strategy. The most forward thinking sports organizations have extended their footprints beyond their venues. FIFA deserves significant credit for extending the World Cup’s footprint beyond the stadiums. For example, FIFA Fan Fests in Brazil are often held on gorgeous beaches in cities where games take place. They are filled with music, television, food, and drink to celebrate the 32 days of the World Cup. This encourages fans from both inside and outside of Brazil to have a World Cup experience without having to attend the games. Millions of people are expected to attend these Fan Fests as they have done in every World Cup since 2002.

However, these place extensions work best when they also encourage people to actually attend the games. In Brazil, the Fan Fests can provide a better overall experience than going to the stadiums. Because many of the stadiums were completed only days before the World Cup started, they lack many of the amenities that are found at the Fan Fest. For example, Arena Amazonia in Manuas will only feature “restaurants and underground parking.” That hardly compares to the festive experience at a Fan Fest. Attending a Fan Fest also does not require buying a ticket or dealing with the traffic problems that occur when traveling to stadiums, and people can still see the game on large television monitors with thousands of other fans. Why attend a game when you can have a better and cheaper experience at a Fan Fest?

The World Cup in Brazil shows that thrilling competitions alone do not fill empty seats. Creating an integrated strategy requires a complete analysis of all factors that would prevent a fan from coming to a venue. This includes examining transportation, accessibility, and technology issues – and making certain that game attendance is not negatively impacted by efforts to engage fans through place extensions.

Adam Grossman is the Founder and President of Block Six Analytics (B6A). He has worked with a number of sports organizations, including the Minnesota Timberwolves, Washington Capitals, and SMG @ Solider Field, to enhance their corporate sponsorship and enterprise marketing capabilities. Irving Rein is Professor of Communication Studies at Northwestern University. He is the author of many books, including The Elusive Fan, High Visibility, and Marketing Places. He has consulted for Major League Baseball, the United States Olympic Committee, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and numerous corporations. They are the co-authors of The Sports Strategist: Developing Leaders for a High-Performance Industry with Ben Shields. Read previous blog posts on the sports business.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post World Cup plays to empty seats appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBallmer overbids by one billionSam sellsBanning Sterling makes a lot of cents for the NBA

Related StoriesBallmer overbids by one billionSam sellsBanning Sterling makes a lot of cents for the NBA

A globalized history of “baron,” part 2

I will begin with a short summary of the previous post. In English texts, the noun baron surfaced in 1200, which means that it became current not much earlier than the end of the twelfth century. It has been traced to Semitic (a fanciful derivation), Celtic, Latin (a variety of proposals), and Germanic. The Old English words beorn “man; fighter, warrior” and bearn “child; bairn” are unlikely sources of baron. Latin vir “man; husband” would not have become baron for phonetic reasons. The same holds for some other proposed Latin v-words. However, in Latin, baro1 “fool; simpleton” and baro2 “a free man” have been attested. As the putative etymons of baron both pose problems. Baro1 meant “fool” and “a strong, muscular man; a man lacking polish, someone from a province,” while baro1 emerged only in the Frankish law code (Lex Salica) known from early medieval manuscripts. The laws, even though they codified the life of a Germanic tribe, were written in Latin, so that there is no certainty that baro2 is a genuine Latin noun: it could be a Latinized Germanic legal term the scribes preferred to leave untranslated. It is hard to decide whether in dealing with Latin baro1 we have two different words (“fool” and “a strong, unpolished man”) or two meanings of the same word. If the second treatment of baro is to be preferred, then what was the way of development: from “fool” to “a strong man” or from “a strong man” to “fool”? The German linguist Franz Settegast believed that only the second alternative should be considered and derived baron from baro1, but he said nothing definite on the history of its Germanic homonym. In his opinion, baro of Lex Salica might be a different word. This is approximately where I left off last week.

As regards the fortunes of Classical Latin baro, Settegast’s idea is reasonable. He believed that, although thanks to Cicero “fool” is the best-remembered sense of baro, it is not the original one. More probably, he suggested, the word arose with the meaning “a strong man” and later acquired the negative connotations “hillbilly, rough person,” as opposed to someone who learned good manners in the capital, was urbane, and depended on his intellect rather than physical strength. Some analogs Settegast cited missed the point, but for his main argument one can find ample confirmation. Thus, in animal folklore, brawn never goes together with brain. The trickster of animal tales is usually a smart weakling: the cat, the coyote, Brer Rabbit, and the rest. Even the fox, though certainly not a puny creature, is smaller and weaker than the wolf and the bear. The trickster’s dupes are the wolf and the bear.

The Gipsy baron of Johann Strauss

As usual in such cases, Settegast had to depend on one or more missing links. He assumed that baro developed in two ways: in one direction it allegedly went from “a strong man” to “fool” and in the other to “*fighter, *warrior, *man” and further to “baron.” The senses I marked with asterisks have not been recorded. Yet many influential specialists in the history of Latin and the Romance languages accepted Settegast’s reconstruction. Despite the consensus the pendulum soon swung in the opposite direction, and etymologists returned to the idea that baron could not be related to a word meaning “fool; simpleton” and traced it to Old High German baro, as we know it from Lex Salica. To support this derivation, one had to offer a plausible etymology of German baro, and Settegast’s opponents came up with the following. There is an Old Icelandic verb berja “to strike,” a cognate of Latin ferio “to strike; kill”; its reflexive form berja-sk means “to fight” (that is, “to exchange blows”). Old High German baro emerged in this scheme as “fighter,” an ideal semantic etymon of baron. However, Icelandic did not have the noun bero “fighter.” Only Old High German bero is known, but it is related to the verb beran “bear; carry” and means “carrier, porter.” It has nothing to do with Icelandic berja ~ berjask. Baro “fighter” ended up with the single support of the nonexistent noun bero “fighter” and nouns like Icelandic bardagi “battle.”

The derivation of baron from Germanic found the support of practically all later etymologists except, predictably, Settegast, who mounted a spirited defense of his old idea, but this time his voice was not heard. His reconstruction did not illuminate every dark corner (remember the asterisked forms, cited above!), but the Germanic reconstruction fares even worse. Settegast refuted the main objection to his theory (“baron” cannot go back to “fool”; of course, it cannot), so that there is no need to repeat the same seemingly crushing counterargument again and again. If Latin baro yielded not only “fool” but also “fighter,” from “a strong man,” then baro, as it occurs in Lex Salica, is a Latin noun.

In my rejection of the Germanic etymology of baron from berjask I am not quite alone. Pierre Guirot, a French etymologist who supports many untraditional solutions, returned to the idea that baron originated in Latin. Regrettably, he offered his opinion without offering detailed proof. Harri Meyer, a distinguished linguist but another maverick of Romance philology, tended to agree with Guirot. Clearly, the tide has not turned. But it does not follow that we have only two choices: either to derive baron from Latin baro or to trace it to Germanic berjask. There is at least one more possibility.

Etymology is a tale of eternal return. Old conjectures tend to resurface in a new light and make us look at forgotten or discarded ideas with interest and even respect. In the early sixties of the nineteenth century, the question was asked whether baron could be a continuation of some word like German Wehrmann “soldier.” Obviously, -on in baron and -mann in Wehrmann are not related. But what about Wehr “defense”? About seventy years later George G. Nicholson had an idea that returned him to Wehr, though, of course, he had no knowledge of an old exchange in Notes and Queries. He paid special attention to the common use of Old French baron with the genitive (“the baron of…”), for example, in li bon baron de France “the good defender, protector of France.” The English equivalent of the Latin phrase barones quinque portuum (which alternated with custodes quinque portuum) is Wardens of the Cinque Ports. In Old French, the word baron was applied to the king, saints, and even Jesus Christ, so that the sense “protector, defender” cannot be called into question.

Nicholson analyzed Old High German words whose English cognates are aware, beware, warn, ward, and warden (their root is war-), and derived baron from the reconstructed Romance form waronem-. The Romance languages did borrow the Germanic root war-, as testified, among others, by guardian, a doublet of warden. Waronem- “protector” would explain the well-attested sense of baron “man.” As mentioned in the previous post, the alternation w/v- ~ b- poses no insurmountable difficulties. Even the native Latin speakers noticed it, and a doublet of Spanish baron is varón “man, male.” The Portuguese form is similar.

Nicholson’s etymology invites serious consideration. Settegast was probably right in not considering “fool” the original sense of Latin baro, but he had a hard time of tracing the path from “a muscular man” to “fighter,” “man; husband,” and, finally, to “baron.” We may also concur with him that Italian barone “rogue” and barone “baron” continue the same Latin etymon. The association between baron and the cognates of Icelandic berjask does not look promising, and one should treat without much confidence the often-repeated statement that Latin had the word baro before the arrival of the Franks. It probably did not. More likely, baron is a Romance adaptation of Germanic waronem-. And couldn’t this coinage (baron) spread to the Celtic-speaking world? Old Irish bár “wise man, sage; leader; overseer,” especially “overseer,” resembles “protector,” the more so because one of the glosses of barons was Latin custodes (the plural of custos). In Ireland, the word might enjoy a shady existence as a legal foreignism, and, presumably, that is why it never occurred in native literature. If such was the state of affairs, barons emerged as protectors and “custodians.” The way from “protector” to “man; husband; fighter” is short. Thus, baron may be, after all, a Germanic word, but going back to an etymon quite different from the one mentioned in our dictionaries.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Alexander Girardi, austrian actor; seen in Johann Strauss II: The Gypsy Baron. Portrait Collection Friedrich Nicolas Manskopf at the library of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University Frankfurt am Main. ID: S36_F08653. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A globalized history of “baron,” part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA globalized history of “baron,” part 1Fishing in the “roiling” waters of etymologyMonthly etymology gleanings for May 2014

Related StoriesA globalized history of “baron,” part 1Fishing in the “roiling” waters of etymologyMonthly etymology gleanings for May 2014

The long, hard slog out of military occupation

In 2003, former secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld infamously foresaw victory in Afghanistan and Iraq as demanding a “long, hard slog” and listed a multitude of unanswered questions. Over a decade later, as President Obama (slowly) fulfills his promise to pull all US troops from Afghanistan, a different set of questions emerges. Which Afghans can coalition troops trust to replace them? Will withdrawal lead to even more corruption in the Hamid Karzai government or that of his successor? Has the return of sectarian violence in Iraq been inevitable?

One assumes that the difficulties associated with withdrawing an occupation force are less daunting than those accompanying invasion. Yet the history of US occupations in Latin America demonstrates just the opposite: invasion itself raises the standards of political behavior in invaded countries to stratospheric heights, thus guaranteeing failure and disillusion when the time comes for withdrawal.

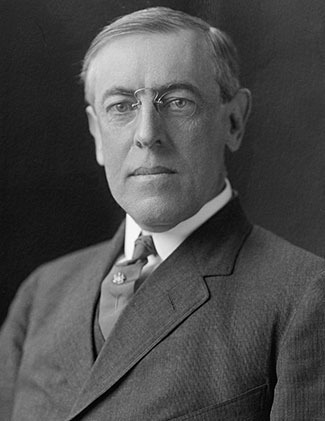

Woodrow Wilson by Harris & Ewing. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A century ago, the Woodrow Wilson administration promised non-intervention in Latin America, but then, in response to World War I, lengthened the already existing US occupation on Nicaragua and started two new occupations, in 1915 in Haiti and in 1916 in the neighboring Dominican Republic.

Publicly, the White House declared that the marines occupied these poor, small republics to protect them from the roaming gunboats of Kaiser Wilhelm.

Much like George W. Bush and his administration did in the Middle East, privately Wilson and his aides shared a vision of a Caribbean area remade in their own image, one where violence as a political tool would be abandoned, political parties would offer programs rather than follow strongmen, and the military would be national and apolitical. Wilson wanted, he said, “orderly processes of just government based upon law.” “The Wilson doctrine is aimed at the professional revolutionists, the corrupting concessionaires, and the corrupt dictators in Latin America,” he added. “It is a bold doctrine and a radical doctrine.”

Too bold and radical, it turned out. At first, failure was not apparent. Marine landings were practically unopposed, as were the overthrows of unfriendly governments. Road building and disarmament moved ahead.

But it was all done without the invaded taking a leadership role, and often against their wishes. There was a great paradox in military occupations teaching democracy. “It is typically American,” one marine later mused, “to believe we can exert a subtle alchemy by our presence among a people for a few years which will eradicate the teaching and training of hundreds of years . . . It is a hopeful theory, but it lacks common sense.” One Haitian advanced that “we have now less knowledge of self-government than we had in 1915 because we have lost the practice of making our own decisions.” A group of Haitians agreed, “there is only one school of self-government, it is the practice of self-government.”

The withdrawal of troops, therefore, became a long, hard slog out. Marines began the process only reluctantly when the invaded became so vocal that they compelled the State Department to eschew plans for reform and just order the troops out. In Nicaragua and Haiti, massacres of or by US troops helped trigger withdrawal. Dominicans rejected all US proposals for withdrawal until they included the return to power of strongmen.

As withdrawal neared, signs were everywhere that the invaded had absorbed no lessons from invaders. Incompetence, discord, and violence plagued elections. New regimes fired competent bureaucrats and appointed friends and family members to office. In Nicaragua, hacks from enemy parties filled the ranks of the constabulary.

Haitians were equally divided between black and mixed-race office-seekers, between north and south, between elites and masses. One US commissioner called Haitian peasants “immeasurably superior to the so-called elite here who affect to despise them and propose to despoil them.” Yet, pressured by public opinion, he cut deals with the worst political elites as marines abandoned plans for creating a responsible middle class in Haiti.

Marines also found themselves in a paradox as they championed nationalism so as to minimize anti-U.S. sentiment. In Nicaragua, occupiers banned any political talk or any flying of partisan flags in the constabulary. They marched guards twice a day with the blue and white Nicaraguan flag and had them sing the national anthem as they raised and lowered it. This was “a ceremony new to a country that for years has known no loyalties except to clan or party.”

US policymakers often threw up their hands as they pulled out troops. Of disoccupying Veracruz, which he also invaded in 1914, Wilson sighed, “If the Mexicans want to raise hell, let them raise hell. We have nothing to do with it. It is their government, it is their hell.”

“It is more difficult to terminate an intervention than to start one,” later observed diplomat Dana Munro, a lesson learned after years of wasted effort in Latin America. US policymakers in the Middle East would do well to take it to heart and avoid leaving the invaded rudderless in their hell.

Alan McPherson is a professor of international and area studies at the University of Oklahoma and the author of The Invaded: How Latin Americans and their Allies Fought and Ended US Occupations.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The long, hard slog out of military occupation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTorture: what’s race got to do with it?This empire of sufferingThe appeal of primitivism in British Georgia

Related StoriesTorture: what’s race got to do with it?This empire of sufferingThe appeal of primitivism in British Georgia

Media bias and the climate issue

“In an irony heaped on an irony, Anthony Watts is lying and exaggerating about a research paper on exaggeration and information manipulation – to stoke the conspiracy theory that climate science is a hoax.” –Sou (HotWhopper) in response to Anthony Watts on WUWT

How do individuals manipulate the information they privately have in strategic interactions? The economics of information is a classic topic, and mass media often features in its analysis. Indeed, the international mass media play an important role in forming people’s perception of the climate problem. However, media coverage on the climate problem is often biased.

Media reporting our paper are vivid examples of the prevalence and variety of media bias in reporting scientific results. While our analysis investigates the media tendency of accentuating or even exaggerating scientific findings of climate damage, the articles misinterpret our results, accentuate and exaggerate one side of our research, and completely omit the other side.

In our research, we analysed why and how a media bias accentuating or even exaggerating climate damage emerges, and how it influences nations’ negotiating an International Environmental Agreement (IEA). We set up a game theoretic model which involves an international mass medium with information advantage, many homogenous countries, and an IEA as players in the game. We then solve for its equilibrium, which, in plain English, means that every player in the game is maximizing her payoff given what others do. The players may update their beliefs in a reasonable way (by Bayes’ rule in our jargon) if they are uncertain about the true state of nature on climate damage. In our model, media bias emerged as an equilibrium outcome, suppressing information the mass media held privately.

The climate problem is important because it involves possibilities of catastrophes and long-lasting systemic effects. The main difficulty of the climate problem is that it is a global public problem and we lack an international government to regulate it. Strong incentives not to contribute and benefit from others’ efforts (free ride) lead to a serious under-participation in an IEA, which further makes the IEA mechanism unlikely to provide enough public goods. The current impasse of climate negotiations showcases this difficulty. The media bias we focused on might have an ex post “instrumental” value as the over-pessimism from the media bias may alleviate the under-participation problem to some extent. However, the media bias could also be detrimental, due to the issue of credibility (as people can update their beliefs). As a result, the welfare implication is ambiguous.

Why certain media have incentives to engage in biased coverage does not mean “justifying lying about climate change.”

Media skeptical of anthropogenic climate changes claimed that our paper advocated lying about climate change, and they used this claim to attack the low carbon movement. Townhall magazine published an article entitled “Academics `Prove’ It’s Okay To Lie About Climate Change” right after our accepted paper was made available online. Further attacks came in; the main tones remained the same. Neglecting the fact that our analysis focuses on media bias, many of the media seemed to tactically avoid discussing media bias (because they knew that they were very biased?), and focused on attacking scientific research on climate change, as if this was the topic of our paper. They often misinterpret the notions “ex ante” and “ex post” (e.g. Motl), believing it to reflect when countries join the IEA in our model, rather than the timing in which we assess the information manipulation. Our conjecture is that most of these media reporting our paper did not actually read through our paper.

As our simple model cannot capture all directions and aspects of media bias on the climate issue, especially those showing up in the coverage of our paper, we call for further scientific research on media bias in reporting scientific results. Furthermore, while the economics profession has the common sense that the global public nature and its associated free-riding incentives are the main difficulty of the climate problem, we find that the media coverage on the climate problem significantly lacks attention to these issues.

Finally, consider the end of in the Economist magazine, in which the author concludes that “In some cases, scientists who work on climate-change issues, and those who put together the IPCC report, must be truly exasperated to have watched the media first exaggerate aspects of their report, and then accuse the IPCC of responsibility for the media’s exaggerations.”

Fuhai Hong is an assistant professor in the Division of Economics, Nanyang Technological University. Xiaojian Zhao is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Together, they are the authors of “Information Manipulation and Climate Agreements” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics.

The American Journal of Agricultural Economics provides a forum for creative and scholarly work on the economics of agriculture and food, natural resources and the environment, and rural and community development throughout the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: climate change headlines background in sepia. © belterz via iStockphoto.

The post Media bias and the climate issue appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesClimate change and our evolutionary weaknessesHow to change behaviourTorture: what’s race got to do with it?

Related StoriesClimate change and our evolutionary weaknessesHow to change behaviourTorture: what’s race got to do with it?

Definitions and dividing lines in the Employment Tribunals Rules of Procedure

The current series of Judicial Pension Scheme claims have raised two interesting points under the most recent Employment Tribunals Rules, introduced in July 2013. Although ultimately neither required determination, the issues highlighted are worth exploring.

The first issue is where the dividing line between preliminary and final hearings should fall. Rule 57 defines a final hearing as one “at which the Tribunal determines the claim or such parts as remain outstanding following the initial consideration (under rule 26) or any preliminary hearing.” The problem is the seemingly very broad definition of “preliminary issue” being one of the things which a tribunal may determine at a preliminary hearing.

A preliminary issue in the context of a complaint means “any substantive issue which may determine liability…” (r. 53(2)). Again, the definition of “substantive” is not entirely clear. It is a word much misused by the drafters of previous iterations of the Rules but is likely to mean something which exists independently of the main issue in the proceedings. So (as per one of the examples in r. 53(2)), in a complaint of unfair dismissal, whether there has been a dismissal or not would be a substantive issue. But then, so it would appear, is a dispute over the reason for the dismissal, an issue historically always dealt with as part of the final hearing. In this context the problem is largely academic except in those very rare cases where a full tribunal will sit for the final hearing. It remains potentially an area of practical difficulty in discrimination claims.

In the current Judicial Pension Scheme cases, three principal issues have fallen for determination at a series of hearings that all parties have agreed to define as preliminary hearings. The first is whether a claimant holding a particular fee-paid judicial office is engaged in the same or broadly similar work as a named comparator who is salaried holder of another, sometimes quite different, judicial office. That looks like a perfectly bona fide preliminary issue as the comparator hurdle must be cleared in order to demonstrate entitlement to bring the proceedings.

The next logical question would then be whether there has been less favourable treatment, e.g. in the payment of fees for attending training. This too seems to have a life independent of the main question, namely whether there has been a breach of the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000.

The third question, whether any less favourable treatment has been objectively justified, seems – instinctively – much less ripe for preliminary determination, although in these cases it has been treated as a preliminary issue without objection. Based on these decisions, my understanding is that the drafting of the definition of “preliminary issue” is deliberately wide.

A second point raised by the recent JPS claims is how the costs rules should be applied to lead cases (r. 36). Rule 74(1) defines costs in terms of those incurred by or on behalf of the receiving party who – in a case to which r. 36 applies – appears to be the lead claimant. But in some cases, many people may have contributed to a fighting fund, while the lead claimant’s contribution to that fund may have been negligible. This difficulty is starkly demonstrated by the question of fees where a multiple has come together as the result of many claimants presenting their own claims without reference to each other over a period of time. In this case, each would incurr a separate issue fee. While the problem over legal costs might be resolved by an agreement between all the claimants – in which the lead claimant agrees to take primary responsibility for the costs subject to an indemnity from the related case claimants – such situations are likely to rare and would not seem to be applicable to the fees incurred by individuals in any event. There is a similar problem where the respondent seeks costs against a lead claimant.

However, r. 36(2) may provide a solution. It seems likely that the costs could and probably should be treated as one of the common or related issues in the case. If so, then the decision made is binding on all the parties in the related cases. Careful wording of the judgement would be required, but there seems little doubt that an order that the respondent pays the lead claimant’s tribunal fees would apply to the fees of all other claimants. Similarly, a judgement that the lead claimant pays the respondent’s costs would be enforceable against all claimants. Whether the judgement should be for a full or proportionate amount should then be a matter for determination on the facts of each case. The obvious problem then becomes one of enforcement.

John Macmillan was formerly a Regional Employment Judge, East Midlands Region, and is now a fee-paid Employment Judge. He is the author of Blackstone’s Guide to the Employment Tribunals Rules 2013 and the Fees Order.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Gavel. By Kuzma, via iStockphoto.

The post Definitions and dividing lines in the Employment Tribunals Rules of Procedure appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTorture: what’s race got to do with it?Puzzling about political leadershipThis empire of suffering

Related StoriesTorture: what’s race got to do with it?Puzzling about political leadershipThis empire of suffering

June 17, 2014

Torture: what’s race got to do with it?

June is Torture Awareness Month, so this seems like a good time to consider some difficult aspects of torture people in the United States might need to be aware of. Sadly, this country has a long history of involvement with torture, both in its military adventures abroad and within its borders. A complete understanding of that history requires recognizing that US torture practices have been forged in the furnace of white supremacy. Indeed the connection between torture and race on this continent began long before the formation of the nation itself.

Every torture regime identifies a group or groups of people whom it is legally and/or morally permissible to torture. To the ancient Romans and Greeks, only slaves were legitimate targets. As Hannah Arendt has observed, the Greeks in particular considered the compulsion to speak under torture a terrible affront to the liberty of a free person.

The activity of identifying a group as an acceptable torture target simultaneously signals and confirms the non-human status of its members. In Pinochet’s Chile, torture targets were called “humanoids” to distinguish them from actual human beings. In other places they are called “cockroaches,” or “worms.” In Brazil’s military dictatorship, people living on city streets suffered fates worse than those of the pickled frogs dissected in high school labs. They were swept up and used to demonstrate torture techniques in classes for police cadets. They were practice dummies.

In the photographs taken at Abu Ghraib, we see naked men cowering like prey before snarling dogs. In one of the most famous, we see a man who has been assigned a dog’s status, on all fours, collared and led on a leash by the US Army Reservist Lynndie England. As theologian William Cavanaugh has observed, it becomes easier to believe that that torture victims are not people when we treat them like dogs. Furthermore, the very vileness of torture reinforces the vileness of the prisoner in the minds of the public. Surely a “good” government such as our own could only be driven to such extremes by a terrible, inhuman enemy.

Witness Against Torture: Detainees, Forward. Photo by Justin Norman. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via shriekingtree Flickr.

So what’s race got to do with it? In this country, the groups whom it is permissible to torture have historically been identified primarily by their race. The history of US torture begins with European settlers’ designation of the native peoples of this continent and of enslaved Africans as subhuman savages. Slaves—almost exclusively persons of African descent—are treated as literally less than human in Article 1 of the US Constitution; for purposes of apportioning representation in the House of Representatives to the various states, a slave was to count as three-fifths of a person. “Indians not taxed” didn’t count as persons at all. Members of both groups fell into categories of persons who might be tortured with impunity.

Institutionalized abuses that were ordinary practice among slaveholders—whipping, shackling, branding and other mutilations—were both common and legal. Nor were such practices incidental to the institution of chattel slavery. Rather, they were central to slavery’s fundamental rationale: the belief that enslaved African beings were not entirely human. As would happen centuries later in the US “war on terror,” the practice of torture actually ratified the prevailing belief in Africans’ inferiority. For surely no true human being would accept such degradation. Equally surely, good Christians would only be moved to such beastly behavior because they were confronted by beasts.

Nor did state-sanctioned torture of African Americans end with emancipation. The institution of lynching continued from the end of the Civil War well into the 20th century, with a resurgence during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. Lynching, in addition to its culminating murder by hanging or burning, often involved whippings, and castration of male victims, prior to death. Lynching served the usual purpose of institutionalized state torture—that is, the establishment and maintenance of the power of white authorities over Black populations. In many places in this country, lynchings were treated as popular entertainment. They were not only permitted but encouraged by local officials, who often participated themselves. The practice even developed a collateral form of popular art: photographs of lynchings decorated many postcards printed in the early part of the 20th century.

US torture in the “war on terror” has displayed its own racial dynamic, although this may not be obvious at first glance. Those tortured in the conduct of this “war” are identified in the public imagination as a particular kind of terrorist. They are Muslims. Some efforts have been made in political rhetoric to distinguish “Islamists” and “Islamofascists” from ordinary “good Muslims,” but a relationship to Islam remains the key identifier. But isn’t “Muslim” a religious, rather than racial, category? Not for most Americans, for whom Islam is a mysterious and foreign force, associated with dark people from dark places. Like “Hindoo,” which was at one time a racial category for US census purposes, in the American mind, the term “Muslim” often conflates religion with race.

There is another important locus of institutionalized state torture in this country, and it, too, is a deeply racialized practice. Abuse and torture—including rape, sexual humiliation, beatings, prolonged exposure to extremes of heat and cold—are routine in US prisons. Many people are beginning to recognize that solitary confinement—presently suffered by at least 80,000 people in US prisons and immigrant detention centers—is also a profound, psychosis-inducing form of torture. Of the more than two million prisoners in the United States today, roughly 60 percent are people of color, while almost three-quarters of prison guards are white.

Fortunately, we can end institutionalized state torture in this country. I encourage readers to donate to, or better yet, get involved with the work of one of these excellent organizations: National Religious Campaign against Torture; Witness against Torture; School of the Americas Watch.

Rebecca Gordon received her B.A. from Reed College and her M.Div. and Ph.D. in Ethics and Social Theory from Graduate Theological Union. She teaches in the Department of Philosophy and for the Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good at the University of San Francisco. She is the author of Letters From Nicaragua, Cruel and Usual: How Welfare “Reform” Punishes Poor People, and Mainstreaming Torture: Ethical Approaches in the Post-9/11 United States.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Torture: what’s race got to do with it? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe appeal of primitivism in British GeorgiaThe decline of evangelical politicsThis empire of suffering

Related StoriesThe appeal of primitivism in British GeorgiaThe decline of evangelical politicsThis empire of suffering

This empire of suffering

On 6 June 2014 at Normandy, President Barack Obama spoke movingly of the day that “blood soaked the water, bombs broke the sky,” and “entire companies’ worth of men fell in minutes.” The 70th anniversary of D-Day was a moment to remember the heroes and commemorate the fallen. The nation’s claim “written in the blood on these beaches” was to liberty, equality, freedom, and human dignity. Honoring both the veterans of D-Day and a new generation of soldiers, Obama emphasized: “people cannot live in freedom unless free people are prepared to die for it.”

Death is seen as the price of liberty in war. But war deaths are more than a trade-off or a price, shaping soldiers, communities, and the state itself. Drew Gilpin Faust wrote that during the Civil War the “work of death” was the nation’s “most fundamental and enduring undertaking.” Proximity to the dead, dying and injured transformed the United States, creating “a veritable ‘republic of suffering’ in the words [of] Frederick Law Olmsted.”

President Lincoln stood on American soil when he remembered the losses at Gettysburg. Does it matter that the site of carnage in World War II commemorated by President Obama was a transcontinental flight away? Americans were deeply affected by that war’s losses, even though the “work of death” would not so deeply permeate the national experience simply because the dying happened far away.

President Barack Obama marks the 65th anniversary of the D-Day invasion with veterans Clyde Combs and Ben Franklin as well as French President Nicolas Sarkozy, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, and Prince Charles on 6 June 2009. Official White House photo by Pete Souza via The White House Flickr.

Since World War II, war’s carnage has become more distant. The Korean War did not generate a republic of suffering in the United States. Instead, as Susan Brewer has shown, Americans had to be persuaded that Korea should matter to them. During the war in Vietnam, division and conflict were central to American culture and politics. A shared experience of death and dying was not.

If war and suffering played a role in constituting American identity during the Civil War, it has moved to the margins of American life in the 21st century. War losses are a defining experience for the families and communities of those deployed. Much effort is placed on minimizing even that direct experience with war deaths through the use of high-tech warfare, like drones piloted far from the battlefield.

Over time, the United States has exported its suffering, enabling the nation to kill with less risk of American casualties. Whatever the benefits of these developments, it is worth reflecting upon the opposite of Faust’s conception of Civil War culture: how American identity is constituted through isolation from the work of war death, through an export of suffering. With a protected “homeland” and exported violence, perhaps what was once a republic has become instead, in war, an empire of suffering.

Mary L. Dudziak is Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law, Emory Law School. Her books include Exporting American Dreams: Thurgood Marshall’s African Journey and Cold War Civil Rights. Her most recent book is War Time: An Idea, Its History, Its Consequences. She will be on the panel “Scholars as Teachers: Authors Discuss Using Their Books in the Classroom” at the SHAFR 2014 Annual Meeting on Saturday, 21 June 2014. Follow her on Twitter @marydudziak.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post This empire of suffering appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe appeal of primitivism in British GeorgiaThe decline of evangelical politicsLife in occupied Paris during World War II

Related StoriesThe appeal of primitivism in British GeorgiaThe decline of evangelical politicsLife in occupied Paris during World War II

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers