Telemachos in Ithaca

How do you hear the call of the poet to the Muse that opens every epic poem? The following is extract from Barry B. Powell’s new free verse translation of The Odyssey by Homer. It is accompanied by two recordings: one of the first 105 lines in Ancient Greek, the other of the first 155 lines in the new translation. How does your understanding change in each of the different versions?

Sing to me of the resourceful man, O Muse, who wandered

far after he had sacked the sacred city of Troy. He saw

the cities of many men and he learned their minds.

He suffered many pains on the sea in his spirit, seeking

to save his life and the homecoming of his companions.

But even so he could not save his companions, though he wanted to,

for they perished of their own folly—the fools! They ate

the cattle of Helios Hyperion, who took from them the day

of their return. Of these matters, beginning where you want,

O daughter of Zeus, tell to us.

Now all the rest

were at home, as many as had escaped dread destruction,

fleeing from the war and the sea. Odysseus alone

a queenly nymph, Kalypso, a shining one among the goddesses,

held back in her hollow caves, desiring that he become

her husband. But when, as the seasons rolled by, the year came

in which the gods had spun the threads of destiny

that Odysseus return home to Ithaca, not even then

was he free of his trials, even among his own friends.

All the gods pitied him, except for Poseidon.

Poseidon stayed in an unending rage at godlike Odysseus

until he reached his own land. But Poseidon had gone off

to the Aethiopians who live faraway—the Aethiopians

who live split into two groups, the most remote of men—

some where Hyperion sets, and some where he rises.

There Poseidon received a sacrifice of bulls and rams,

sitting there and rejoicing in the feast.

The other gods

were seated in the halls of Zeus on Olympos. Among them

the father of men and gods began to speak, for in his heart

he was thinking of bold Aigisthos, whom far-famed Orestes,

the son of Agamemnon, had killed. Thinking of him,

he spoke these words to the deathless ones: “Only consider,

how mortals blame the gods! They say that from us

comes all evil, but men suffer pains beyond what is fated

through their own folly! See how Aigisthos pursued

the wedded wife of the son of Atreus, and then he killed

Agamemnon when he came home, though he well knew

the end. For we spoke to him beforehand, sending Hermes,

the keen-sighted Argeïphontes, to say that he should not kill

Agamemnon and he should not pursue Agamemnon’s wife.

For vengeance would come from Orestes to the son of Atreus,

once Orestes came of age and wanted to reclaim his family land.

So spoke Hermes, but for all his good intent he did not persuade

Aigisthos’ mind. And now he has paid the price in full.”

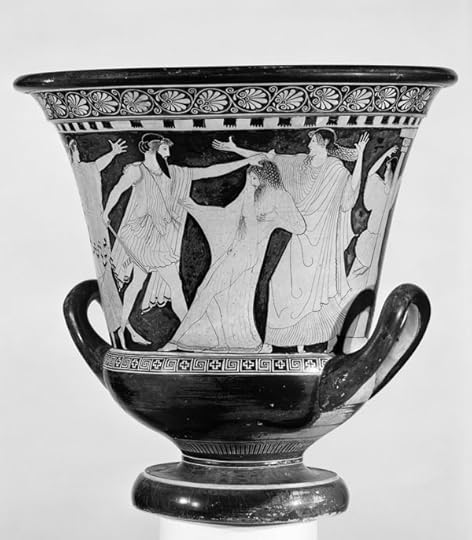

Aigisthos holds Agamemnon, covered by a diaphanous robe, by the hair while he stabs him with a sword. Apparently this illustration is inspired by the tradition followed in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, where the king is caught in a web before being killed. Klytaimnestra stands behind Aigisthos, urging him on, while Agamemnon’s daughter attempts to stop the murder (she is called Elektra in Aeschylus’ play). A handmaid flees to the far right. Athenian red-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 500–450 BC. W. F. Warden Fund © Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 63.1246.

Then the goddess, flashing-eyed Athena, answered him:

“O father of us all, son of Kronos, highest of all the lords,

surely that man has fittingly been destroyed. May whoever

else does such things perish as well! But my heart

is torn for the wise Odysseus, that unfortunate man,

who far from his friends suffers pain on an island surrounded

by water, where is the very navel of the sea. It is a wooded

island, and a goddess lives there, the daughter of evil-minded

Atlas, who knows the depths of every sea, and himself

holds the pillars that keep the earth and the sky apart.

Kalypso holds back that wretched, sorrowful man.

Ever with soft and wheedling words she enchants him,

so that he forgets about Ithaca. Odysseus, wishing to see

the smoke leaping up from his own land, longs to die. But your

heart pays no attention to it, Olympian! Did not Odysseus

offer you abundant sacrifice beside the ships in broad Troy?

Why do you hate him so, O Zeus?”

Zeus who gathers the clouds

then answered her: “My child, what a word has escaped the barrier

of your teeth! How could I forget about godlike Odysseus,

who is superior to all mortals in wisdom, who more than any other

has sacrificed to the deathless goes who hold the broad heaven?

But Poseidon who holds the earth is perpetually angry with him

because of the Cyclops, whose eye he blinded—godlike

Polyphemos, whose strength is greatest among all the Cyclopes.

The nymph Thoösa bore him, the daughter of Phorkys

who rules over the restless sea, having mingled with Poseidon

in the hollow caves. From that time Poseidon, the earth-shaker,

does not kill Odysseus, but he leads him to wander from

his native land. But come, let us all take thought of his homecoming,

how he will get there. Poseidon will abandon his anger!

He will not be able to go against all the deathless ones alone,

against their will.”

Then flashing-eyed Athena, the goddess,

answered him: “O our father, the son of Kronos, highest

of all the lords, if it be the pleasure of all the blessed gods

that wise Odysseus return to his home, then let us send Hermes

Argeïphontes, the messenger, to the island of Ogygia, so that

he may present our sure counsel to Kalypso with the lovely tresses,

that Odysseus, the steady at heart, need now return home.

And I will journey to Ithaca in order that I may the more

arouse his son and stir strength in his heart to call the Achaeans

with their long hair into an assembly, and give notice to all the suitors,

who devour his flocks of sheep and his cattle with twisted horns,

that walk with shambling gait. I will send him to Sparta and to sandy

Pylos to learn about the homecoming of his father, if perhaps

he might hear something, and so that might earn a noble fame

among men.”

So she spoke, and she bound beneath her feet

her beautiful sandals—immortal, golden!—that bore her

over the water and the limitless land together with the breath

of the wind. She took up her powerful spear, whose point

was of sharp bronze, heavy and huge and strong,

with which she overcomes the ranks of warriors when she is angry

with them, the daughter of a mighty father. She descended

in a rush from the peaks of Olympos and took her stand

in the land of Ithaca in the forecourt of Odysseus, on the threshold

of the court. She held the bronze spear in her hand, taking on

the appearance of a stranger, Mentes, leader of the Taphians.

There she found the proud suitors. They were taking their pleasure,

playing board games in front of the doors, sitting on the skins

of cattle that they themselves had slaughtered. Heralds

and busy assistants mixed wine with water for them

in large bowls, and others wiped the tables with porous sponges

and set them up, while others set out meats to eat in abundance.

Godlike Telemachos was by far the first to notice

her as he sat among the suitors, sad at heart, his noble

father in his mind, wondering if perhaps he might come

and scatter the suitors through the house and win honor

and rule over his own household. Thinking such things,

sitting among the suitors, he saw Athena. He went straight

to the outer door, thinking in his spirit that it was a shameful thing

that a stranger be allowed to remain for long before the doors.

Standing near, he clasped her right hand and took the bronze

spear from her. Addressing her, he spoke words that went

like arrows: “Greetings, stranger! You will be treated kindly

in our house, and once you have tasted food, you will tell us

what you need!”

So speaking he led the way, and Pallas Athena

followed. When they came inside the high-roofed house,

Telemachos carried the spear and placed it against a high column

in a well-polished spear rack where were many other spears

belonging to the steadfast Odysseus. He led her in and sat her

on a chair, spreading a linen cloth beneath—beautiful,

elaborately-decorated—and below was a footstool for her feet.

Beside it he placed an inlaid chair, apart from the others,

so that the stranger might not be put-off by the racket and fail

to enjoy his meal, despite the company of insolent men.

Also, he wished to ask him about his absent father.

A slave girl brought water for their hands in a beautiful golden

vessel, and she set up a polished table beside them.

The modest attendant brought out bread and placed it before them,

and many delicacies, giving freely from her store. A carver

lifted up and set down beside them platters with all kinds

of meats, and set before them golden cups, while a herald

went back and forth pouring out wine for them.

In came the proud suitors, and they sat down in a row

on the seats and chairs, and the heralds poured out water for

their hands, and women slaves heaped bread by them in baskets,

and young men filled the wine-mixing bowls with drink.

The suitors put forth their hands to the good cheer lying before them,

and when they had exhausted their desire for drink and food,

their hearts turned toward other things, to song and dance.

For such things are the proper accompaniment of the feast.

A herald placed the very beautiful lyre in the hands of Phemios,

who was required to sing to the suitors. And he thrummed the strings

as a prelude to song.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His new free verse translation of The Odyssey was published by Oxford University Press in 2014.His translation of The Iliad was published by Oxford University Press in 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Telemachos in Ithaca appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFaith and science in the natural worldA 2014 summer songs playlistPutting an end to war

Related StoriesFaith and science in the natural worldA 2014 summer songs playlistPutting an end to war

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers