Oxford University Press's Blog, page 806

June 2, 2014

Football arrives in Brazil

Charles Miller claimed to have brought the first footballs to Brazil, stepping off the boat in the port of Santos with a serious expression, his boots, balls and a copy of the FA regulations, ready to change the course of Brazilian history. There are no documents to record the event, only Miller’s own account of a conversation, in which historians have picked numerous holes. There are no images either, which is why to mark the impending Miller-mania surrounding English participation in the World Cup in Brazil, I recreated the scene on the docks at Santos, today South America’s biggest and busiest port. (Thanks to my colleague Gloria Lanci for capturing the solemnity of the occasion).

Opposite the passenger terminal, where the photo was taken, an old building is being converted into the Museu do Pelé, to house the history of Santos Futebol Clube’s most famous player, heralded by many as the greatest footballer of the twentieth century – though it will not be ready to open in time for the World Cup. The stories of Miller and Pelé are often linked to illustrate the development of football in Brazil. Gilberto Freyre, the Brazilian sociologist and historian, was one of the first:

‘[It was] Englishmen who introduced into Brazil the principal sporting and recreational replacements for our colonial jousting tournaments: horse-racing, tennis, cycling and football itself, which here became fully naturalised as a game not for fair-haired European expatriates in the tropics but for local people: […] people increasingly of varying shades of brown; with de-Anglicisation culminating in the admirable Pelé, after shining with Leônidas.

[Football] has become a veritable Afro-Brazilian dance, with footwork never imagined by its inventors. Has it stopped being British? Not in the slightest. Association football cannot be separated from its British origins to be considered a Brazilian or Afro-Brazilian invention. What it is, in its current, triumphant expression, is an Anglo-Afro-Brazilian game’. (Gilberto Freyre, The British in Brazil, London, 2011, first published in Portuguese in 1954, p.13.)

Charles Miller was born in São Paulo to a Scottish father and a Brazilian mother whose surname, Fox, reveals her English origins. During his lifetime the population of São Paulo ballooned from around 100,000 in 1874 to well over 2 million in 1953. Most of those new citizens were migrants and their children. São Paulo and Brazil were remaking themselves. Football and music became central ways for Brazilians to express a new inclusive identity after the abolition of slavery (1888) and the establishment of a new republic to replace monarchy (1889).

The sense of Brazilian football leaving its British origins behind as it headed for global domination on and off the pitch, as suggested by Freyre, is why there is no statue or plaque to Miller in the city, not even in the Praça Charles Miller, the square at the front of the Pacembu stadium which houses the Museu do Futebol. Though he was born and died in Brazil, and lived almost his entire life in Brazil (the exception was his schooling in Hampshire, England) Miller’s legend is that of an immigrant, stepping off the ship in Santos to begin a new life. His ambiguous identity, floating between Scottish, British and Brazilian might explain why his simple grave in the Cemeterio de Protestantes in São Paulo is so modest (a cross marked C.W.M, which the director of the cemetery asked me not to photograph, “out of respect”). The Museu Charles Miller, housed in the exclusive Clube Athletico Sao Paulo, and available to visit on appointment, contains old photographs, trophies and a letter from Pelé.

In Brazilian football historiography, “Charles Miller” has become a cipher for the elite, foreign origins of a game which was were subsequently embraced by the Brazilian povo (the people). Something similar is true of Alexander Watson Hutton for Argentina, a more conventional immigrant figure, a Scot who arrived in Buenos Aires as an adult and set about institutionalising and regulating the game of football through schools, teams and leagues. At the II Simpósio Internacional de Estudos Sobre Futebol that I attended in São Paulo last week, Miller was referenced by many of the researchers as a scene-setter to establish their credentials, his name alone enough to conjure images of moustachioed elite white men in blazers tapping a ball around.

At the Simposio, discussing museums and football with Richard McBrearty, director of the Scottish Football Museum, and Daniela Alfonsi, Diretora de Conteudo do Museu de Futebol, Kevin Moore, director of the [English] National Football Museum, noted that Miller’s story is ‘the very epitome of the multinational, global nature of the origins of football’. But they also pointed out that the origins of football were anything but a one man show. Hundreds of people played football in Brazil at the end of the nineteenth century, and historian José Moraes dos Santos Neto has argued pretty convincingly that football was being played in several places in Brazil before Miller’s much-heralded return from England. The ways in which Brazilians took on the game and made it their own is the subject of many wonderful books, including Alex Bellos’ Futebol: The Brazilian Way of Life and David Goldblatt’s Futebol Nation: A Footballing History of Brazil. The importance of Charles Miller lies not in any individual greatness but in the way that his story has captured something of the essence of being Brazilian, and of the ways in which football was adopted, regulated, internationalised and embraced around the world.

Dr Matthew Brown is a reader in Latin American Studies at the University of Bristol, and specialises in the history of sports in South America. In particular, the history of the very first football teams to be established. He contributed the biographies of Charles Miller and Alexander Hutton to Oxford Dictionary of National Biography’s May update.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day. In addition to 58,800 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 190 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @ODNB on Twitter for people in the news.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Matthew Brown arriving in Brazil, impersonating Charles Miller, © Gloria Lanci. (2) Site of the forthcoming Museu do Pelé, © Matthew Brown.

The post Football arrives in Brazil appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMary Lou Williams, jazz legendTourism and the 2010 World CupPhotography and social change in the Central American civil wars

Related StoriesMary Lou Williams, jazz legendTourism and the 2010 World CupPhotography and social change in the Central American civil wars

June 1, 2014

The in-depth selfie: discussing selfies through an academic lens

Looking at oneself is a timeless concept. We are constantly trying to figure out how to represent ourselves in our own brains . . . confusing certainly. In honor of Oxford Dictionaries’s 2013 word of the year — “selfie” — University of Southern California professors pay homage by discussing selfies through the lens of letters, arts, and sciences. They analyse the selfie trend through the perspectives of sociology, gender studies, religion, anthropology, and more. Watch their video below and learn how profound a camera flash and puckered mouth can be.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Language matters. At Oxford Dictionaries, we are committed to bringing you the benefit of our language expertise to help you connect with your world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The in-depth selfie: discussing selfies through an academic lens appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesKotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of languageFarmily album: the rise of the felfieMonthly etymology gleanings for May 2014

Related StoriesKotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of languageFarmily album: the rise of the felfieMonthly etymology gleanings for May 2014

May 31, 2014

How well do you know short stories?

Short stories populate many childhoods, with the aim to instill morals and virtues in undeveloped and wandering minds. Whether it’s the tale of Rumpelstiltskin or the Boy Who Cried Wolf, these tales make a powerful impression. Take our short stories quiz, based off of Oscar Wilde’s The Complete Short Stories and The Oxford Book of American Short Stories, 2nd ed, edited by Joyce Carol Oates, and see if you really know your short stories.

Scene on the Hudson (Rip Van Winkle) by James Hamilton. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Maggie Belnap is a Social Media Intern at Oxford University Press. She attends Amherst College.

The Complete Short Stories by Oscar Wilde is edited by John Sloan. He is Fellow and Tutor in English, Harris Manchester College, Oxford. The Oxford Book of American Short Stories, 2nd ed, is edited by Joyce Carol Oates. Oates is the National Book Award-winning author of over fifty novels, including bestsellers We Were the Mulvaneys, Blonde, and The Gravedigger’s Daughter. She is the Roger S. Berlind Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at Princeton University.

Oscar Wilde is the author of “The Happy Prince,” “The Fisherman and His Soul,” “The Nightengale and the Rose,” “The Star Child,” and “The Young King.” Washington Irving is the author of “Rip Van Winkle.” James Baldwin is the author of “Sonny’s Blues.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How well do you know short stories? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWomen of 20th century musicA tale of two fables: Aesop vs. La FontaineA Mother’s Day reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Related StoriesWomen of 20th century musicA tale of two fables: Aesop vs. La FontaineA Mother’s Day reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

History strikes back: Ukraine’s past and the current crisis

As Ukrainian voters go to the polls this weekend to elect the new president, their country remains stalled at a historical crossroads. A revolution sparked by the previous government’s turn away from Europe, Russia’s flagrant annexation of the Crimea, and the continuing fighting in eastern Ukraine–all these events of recent months can only be understood in their proper historical context.

A monument to the legendary founders of Kyiv re-imagined as a symbol of the pro-European revolution.

One must begin with Russia’s imperial domination of Ukraine during the age when modern nations developed, from the 18th to the 20th centuries. Much like the Scots in the United Kingdom, Ukrainians could make brilliant careers in the Russian imperial service, but their group identity was reduced to an ethnographic curiosity. Moreover, the tsarist government insisted that Ukrainians were not a separate ethnic group, merely the “Little Russian tribe” of the Russian people. Their language was no more than a peasant dialect, and all educated Ukrainians were expected to accept Russian high culture. To prevent a modern idea of nationhood from reaching the Ukrainian masses, the Russian government banned all educational books in Ukrainian in 1863 and literary publications in 1876.

This denial of Ukraine’s national distinctiveness had major implications for modern Russian and Ukrainian identities. The notion of what it meant to be Russian remained linked to the imperial project, first tsarist, then Soviet, and now Putin’s. In all these incarnations, imperial Russia was not prepared to let Ukraine go its way precisely because Russia’s own identity as a modern democratic nation without imperial complexes failed to develop. This explains the rise in Putin’s popularity after the annexation of Crimea. This act of aggression soothed the injured national pride of Russia’s imperial chauvinists, who still mourn the loss of their country’s great-power status.

[image error]

A fake road sign used by the pro-European protesters in Kyiv: “Changing the country, sorry for the inconvenience.”

The long Russian “fraternal” embrace also had implications for Ukraine’s ambivalent national identity. The Ukrainian national governments of 1917–20 did not stay in power in large part because patriotic intellectuals could not reach out to the peasants in the previous decades. The Bolsheviks first tried to disarm Ukrainian nationalism by promoting education and publishing in Ukrainian, but in the 1930s Stalin decimated the Ukrainian intelligentsia by terror and killed millions of peasants in a man-made famine, the Holodomor. His successors promoted creeping assimilation into the Russian culture. As a result, the population of Ukraine’s southeast, although largely Ukrainian in ethnic compositions, was taught to identify with Russian culture and the Soviet state.

Another thing that the tsars, the commissars, and the Putin administration have in common is an inflated fear of “Ukrainian nationalists.” Its real explanation lies in the fact that the Russian Empire never controlled all Ukrainian ethnolingustic territories. In the 19th century their westernmost part belonged to the Austrian Empire, where the Ukrainians acquired the experience of political participation and communal organization. The tsarist government’s desire to crush the stronghold of “Ukrainian nationalism” in the Austrian province of Galicia was among the international tensions that caused World War I. After the Red Army finally secured this region for the Soviet Union during World War II, the anti-Soviet nationalist insurgency continued for nearly a decade. The spectre of “Ukrainian nationalism” has haunted the Russian political imagination ever since, because it threatened the main tenet of imperial ideology, that of Ukrainians being essentially “uneducated Russians.”

A barricade of tires prepared to be burned on Kyiv’s main boulevard.

In the twenty-three years since the Soviet collapse, the political elites in Russia and Ukraine learned to exploit the ambiguous sense of identity in both countries. The Putin administration discovered imperial chauvinism’s appeal to conservative voters outside of major cities. In Ukraine, President Viktor Yanukovych and his Party of Regions cultivated nostalgia for the Soviet past and identification with Russian culture in their electoral stronghold in the Donbas, the region of Soviet-style smokestack factories propped up by government subsidies. The identity time-bomb was bound to explode at some point, and it went off twice in the past decade.

The Orange Revolution of 2004 began as a mass protest against a rigged election allegedly won by Prime Minister Yanukovych, but grew into a popular civic movement against corruption and political manipulation. Unfortunately, the victors of the revolution did not manage to build a new system, instead descending into political infighting. Yanukovych finally gained the presidency in 2010 and went on to establish an even more corrupt regime. By the end of 2013 Ukrainians were so fed up with their government that the latter’s last-minute withdrawal from the Association Agreement with the European Union sparked another popular revolution.

The protestors on the EuroMaidan were not fighting for Europe and against Russia per se, but against authoritarianism and corruption. However, it is telling that the Putin regime saw their movement as a threat to Russia’s interests. The Russian state-controlled media exploited the presence on the barricades of radical Ukrainian nationalists to paint the entire popular revolution as “fascist.” Without the Russian annexation of the Crimea and barely-concealed support for the separatists in the Donbas, the situation there would also not have reached the brink of a civil war.

In many ways, then, the long-term resolution of the Ukrainian crisis would entail Russians and Ukrainians coming to terms with history–laying the imperial past finally to rest.

Serhy Yekelchyk is Professor of Slavic Studies and History at the University of Victoria (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada) and the author of Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation (OUP, 2007).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images courtesy of Serhy Yekelchyk. Used with permission.

The post History strikes back: Ukraine’s past and the current crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTinderbox drenched in vodka: alcohol and revolution in UkraineThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play byCybersecurity and the cyber-awareness gap

Related StoriesTinderbox drenched in vodka: alcohol and revolution in UkraineThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play byCybersecurity and the cyber-awareness gap

World No Tobacco Day 2014: Raise taxes on tobacco

Since 1994, the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT) has been supporting the science and research community. To celebrate the society’s 20th anniversary and to help mark the World Health Organization’s World No Tobacco Day on 31 May 2014, we invite you to read a free collection of articles published in the society’s journal, Nicotine & Tobacco Research (N&TR), covering both top scholarship and the growth of the society.

By Gary E. Swan

According to the WHO’s fact sheet on tobacco, chronic tobacco use caused 100 million deaths in the 20th century. If current trends continue, it may cause one billion deaths in the 21st century. The global tobacco epidemic kills nearly six million people each year, of which more than 600,000 are non-smokers dying from breathing second-hand smoke. More than 80% of these preventable deaths will be among people living in low-and middle-income countries. Unless there is continued and more rapid dissemination of best tobacco control and cessation practices, the epidemic will kill more than eight million people every year by 2030.

In addition to the global dissemination of tobacco control strategies to the large number of smokers who want to quit, there is a need to continue to inform and motivate health care providers to encourage their patients who smoke to quit. For example, a systematic review of studies from the United States using direct observation of physicians during medical encounters found that smoking was discussed infrequently (21% of all encounters), with only 36% of potentially eligible patients having received advice as recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force on smoking cessation.

Another compelling reason for persistent dissemination of evidence-based findings from the nicotine and tobacco research field is provided by the US Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products (CTP), a new entity empowered to regulate tobacco products by the 2009 The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. In order to effectively regulate tobacco products, the CTP requires scientific evidence to support claims that new products, such as e-cigarettes, reduce exposure and subsequent harm to the smoking public. Evidence, both supportive and non-supportive, from the scientific community is currently being actively sought by the CTP.

Because of the lethality of chronic consumption of tobacco, effective tobacco control and smoking cessation approaches remain among the most cost effective life-saving medical procedures known to man. Methods such as taxation are highly effective and, for World No Tobacco Day 2014, WHO and partners have issued a call to countries to raise taxes on tobacco. N&TR has published many empirical studies on the effects of taxation on tobacco use.

The interval between the conduct of research and implementation of evidence-based prevention and treatment results remains unacceptably long from many perspectives. Hopefully newer electronic Web-based applications and technologies will facilitate interactive information sharing, interoperability, user-centered design, and collaboration. The editors of N&TR believe such applications and technologies will enhance the dissemination of research evidence and, thus, facilitate the translation of scientific evidence for effective programs and services into everyday practice around the world. By so doing, we will be better positioned to reduce the enormous human and economic costs of global tobacco use.

Gary E. Swan, PhD, is the Founding Editor of Nicotine & Tobacco Research, a Past President of SRNT, and a Consulting Professor at Stanford University’s Prevention Research Center.

Nicotine & Tobacco Research is one of the world’s few peer-reviewed journals devoted exclusively to the study of nicotine and tobacco. Its mission is to publish a range of content representing all facets of the evidence-based science of nicotine and tobacco. The journal is published by OUP on behalf of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. Dissemination of the science published by N&TR has long been a priority. The need for a renewed focus on the global dissemination of best practices and science as described in each of the papers from the 20th anniversary collection is as apparent today as it was more than a decade ago.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Anti smoking image. © ansar80 via iStockphoto.

The post World No Tobacco Day 2014: Raise taxes on tobacco appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGene flow between wolves and dogsTourism and the 2010 World CupVirgil in Russia

Related StoriesGene flow between wolves and dogsTourism and the 2010 World CupVirgil in Russia

May 30, 2014

In memoriam: Malcolm MacDonald

With great sadness, Oxford reports the passing of esteemed music author and critic Malcolm MacDonald, who died on 27 May 2014.

MacDonald was until December 2013 Editor of the modern-music journal Tempo, and reviewed regularly for BBC Music Magazine and the International Record Review. He wrote both under his given name and as Calum MacDonald (to avoid confusion with the composer also named Malcolm MacDonald).

MacDonald contributed enormously to the literature and resources on numerous late-nineteenth and twentieth-century composers, and in the community of musicians and scholars, he was a champion of many. The list of figures is long, and includes the likes of Johannes Brahms, John Foulds, Ronald Stevenson, Alan Bush, Erik Bergman, Dmitri Shostakovich, Bernard Stevens, Luigi Dallapiccola, Antal Doráti, and Edgar Varèse. Among MacDonald’s several contributions to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Grove Opera, his article on English composer and music journalist Havergal Brian was of particular importance, and reflects a substantial body of work elsewhere published on Brian.

As part of his impressively varied list of publications, MacDonald is author of two volumes in the venerable Master Musicians series: the distinguished Brahms (Schirmer 1990, reissued in 2001 from OUP) and the indispensable Schoenberg (the first edition published with Dent in 1976, and the second edition in 2008 with OUP). In his Preface to the First Edition of Schoenberg, we find:

The most a writer may do is to place the music in perspective and give it a human context; from which, perhaps, its human content will emerge more clearly. That is what I have tried to do.

And this is what, at the very least and amidst his myriad achievements, Malcolm MacDonald has indeed done. His work will remain valuable, and his legacy vital, for generations.

Suzanne Ryan is Editor in Chief, Humanities and Executive Editor, Music at Oxford University Press in New York.

The post In memoriam: Malcolm MacDonald appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQ&A with James Keller, author of Chamber Music: A Listener’s GuideMary Lou Williams, jazz legendSplash! What kids discover in a puddle

Related StoriesQ&A with James Keller, author of Chamber Music: A Listener’s GuideMary Lou Williams, jazz legendSplash! What kids discover in a puddle

Cybersecurity and the cyber-awareness gap

“‘There’s probably no issue that’s become more crucial, more rapidly, but is less understood, than cybersecurity,’ warns cyber expert P.W. Singer, co-author of Cybersecurity and Cyberwar: What Everyone Needs to Know. Cybersecurity has quickly become one of the most defining challenges of our generation, and yet, as the threat of cyber-terrorism looms, there remains an alarming “cyber-awareness gap” that renders the many of us vulnerable. We interviewed P.W. Singer in order to learn more about why this issue is so crucial to our daily lives and how well-equipped our government is to protect us from the risks that lie ahead.

P.W. Singer discusses the growing importance of cybersecurity today

Click here to view the embedded video.

P.W. Singer talks about the role government plays in regulating the internet

Click here to view the embedded video.

P.W. Singer highlights the cyber-awareness gap in U.S. government

Click here to view the embedded video.

P.W. Singer and Allan Friedman are the authors of Cybersecurity and Cyberwar: What Everyone Needs to Know. P.W. Singer is Director of the Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence at the Brookings Institution. Allan Friedman is a Visiting Scholar at the Cyber Security Policy Research Institute, School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at George Washington University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Cybersecurity and the cyber-awareness gap appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow secure are you?Protecting yourself from the threat of cyberwarfareCybersecurity and cyberwar playlist

Related StoriesHow secure are you?Protecting yourself from the threat of cyberwarfareCybersecurity and cyberwar playlist

The fall of Rome to the rise of the Catholic Church, in pictures

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Western world went through a turbulent and dramatic period during which a succession of kingdoms rose, grew, and crumbled in spans of only a few generations. The wars and personalities of the dark ages are the stuff of legend, and all led toward the eventual reunification of Europe under a different kind of Roman rule — this time, that of the Church. Below, historian Peter Heather selects ten moments from the period upon which the fate of Europe hinged.

March 15, 493 AD: King Odoacer slain by Theoderic

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Theoderic, king of the new Ostrogothic coalition created since the death of Attila the Hun in 453, slices Odoacer in half after dinner in Ravenna to take complete control of Italy and the Adriatic coast of Dalmatia. He subsequently adds to this Sicily, a large part of modern Hungary, southern France and most of Spain to relaunch Empire in the west, consciously styling himself as the head of a fully and legitimately Roman state.

January 1, 519 AD: Eutharic becomes consul

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Theoderic’s chosen heir and son-in-law, Eutharic, receives the Roman consulship with the full blessing of Constantinople, seeming to guarantee that Theoderic’s Empire will last into the next generation. But Eutharic dies before Theoderic, and, on the latter’s death, Constantinople encourages the centrifugal forces which break the Empire up once more into separate Gothic kingdoms in Italy and Spain.

January 18, 532 AD: Massacre at the Nika riots

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The Emperor Justinian turns loose his General Belisarius and his trusted soldiery on a crowd in the Hippodrome, which has been baying for his replacement, after a sequence of military defeats against Persia. At the end of the day, thousands are dead and the ceremonial centre of Constantinople a burnt out ruin, but Justinian has clung onto power. (Pictured: the Hippodrome today.)

September 14, 533 AD: The battle of Ad Decimum

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Desperately seeking renewed legitimacy, Justinian sends Belisarius to North Africa this time to exploit political division in the Vandal kingdom. In the battle, Belisarius wins a stunning victory over the Vandal king Gelimer, and Carthage swiftly falls. This unexpectedly easy victory leads Justinian to adopt a more general policy of conquest in the west which will add Italy, Dalmatia and parts of southern Spain, as well as North Africa, to his Empire by the mid-550s.

June 8, 632: The prophet Muhammad dies

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Muhammad perishes on the eve of the great Islamic conquests which will engulf the Near East, North Africa, and much of Spain within the next hundred years. They utterly destroy the Persian Empire and deprive Constantinople of between two-thirds and three-quarters of its territories and tax revenues. The old East Roman Empire is reduced from world to regional power, and its domination of the western Mediterranean, reasserted under Justinian, destroyed forever.

Christmas Day, 800 AD: Charlemagne is crowned emperor by Pope Leo III in St. Peters

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The Islamic destruction of Constantinople’s capacity to influence western events has combined with transalpine economic and demographic development to allow a restoration of Empire in the west based for the first time on a north European powerbase. Contrary to his own propaganda, Charlemagne has been actively seeking the imperial title for at least a decade, and it is no coincidence that, the day before, he had convened a synod which cleared the Pople of some very embarrassing allegations, with no questions asked.

June 25, 841 AD: The Battle of Fontenoy

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Charlemagne’s grandsons fight a bloody engagement at Fontenoy, kickstarting the process of Carolingian imperial fragmentation. Unlike its Roman predecessor which used large-scale taxation to maintain professional military forces, the capacity of Charlemagne’s state to wage war was based on militarised gentry and aristocratic landowners whose allegiance had to be bought – largely by grants of land - in each generation. This made it extremely difficult to maintain centralised supra-regional power in the long-term, as wealth tended to leech away from monarchs, especially in the context of civil war, where military support was at a premium.

February 12, 1049 AD: Coronation of Pope Leo IX

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Bruno of Egisheim-Dagsburg is crowned Pope Leo IX, marking the moment when the products of the Christian cultural revolution instigated by Charlemagne took possession of the Roman Papacy to further his ideals of Christian reform. Emperors and Kings had previously provided the Church with the necessary resources and enforcement structures to make reform work, but Latin Christendom (increasing in size as conversion continued) was now divided between too many rulers for any one to be the source of the united leadership that the common culture of Latin Churchmen, the product of Charlemagne’s libraries and reforms, desired.

December 28, 1210 AD: Approval of the Compilatio tertia, the oldest official compilation of Papal legal decisions, or decretals

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

When Leo IX became Pope, the Papacy enjoyed great prestige, but little practical authority. This was transformed by a legal revolution – beginning with Gratian’s Concordance of Discordant Canons in c. 1150 – which used the legal principles and techniques of old Roman imperial law systematically to resolve disagreements in Church teaching on the principle that existing Papal rulings carried greatest authority, while simultaneously requiring that any new or currently unresolved issues be addressed by new Papal decrees.

November 11, 1215 AD: Fourth Council of the Lateran

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Seventy-one metropolitans, four hundred and twelve bishops, and nine hundred abbots and priors gather in Rome for the opening of Lateran IV, then the largest Christian council ever held. It defines required standards of Catholic lay and clerical piety which last down to the twentieth century. Equally important, it symbolises the transfer of ecclesiastical authority from emperors to Popes. Four hundred years earlier, it was Charlemagne who had called the ecclesiastical shots, but, in the meantime, the legal structure of one Roman Empire had been used to create a new one.

Peter Heather is Professor of Medieval History at King’s College London. He is the bestselling author of The Restoration of Rome: Barbarian Popes and Imperial Pretenders, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe, and numerous other works on late antiquity and the early Middle Ages.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: 1. Coin with profile of Odoacer. Permission via Creative Commons by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. Via Wikimedia Commons. 2. 16th century statue of Theoderic. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 3. The Hippodrome of Constantinople today. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 4. Mosaic depicting Justinian. Permission via GNU license. Via Wikimedia Commons. 5. 18th century Turkish depiction of Muhammad ascending to Heaven. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 6. “Coronation of Charlemagne” by Jean Fouquet, c. 1460. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 7. “Battle of Fontenoy” by Pierre Lenfant, c. 1747. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 8. Statue of Pope Leo IX in Altorf, France. Permission via GNU license. Via Wikimedia Commons. 9. Pope Innocent III, whose decretals comprised the Compilatio Tertia, depicted in a fresco c. 1219. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 10. “Lateran Palace” by Giuseppe Vasi, c. 1752. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The fall of Rome to the rise of the Catholic Church, in pictures appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Roman conquest of Greece, in picturesThe rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in picturesJohn Calvin’s authority as a prophecy

Related StoriesThe Roman conquest of Greece, in picturesThe rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in picturesJohn Calvin’s authority as a prophecy

Ten landscape designers who changed the world

By Ian Thompson

It comes as a surprise to many people that landscapes can be designed. The assumption is that landscapes just happen; they emerge, by accident almost, from the countless activities and uses that occur on the land. But this ignores innumerable instances where people have intervened in landscape with aesthetic intent, where the landscape isn’t just happenstance, but the outcome of considered planning and design. Frederick Law Olmsted and his partner Calvert Vaux coined a name for this activity in 1857 when they described themselves as ‘landscape architects’ on their winning competition entry for New York’s Central Park; but ‘landscape architecture’ had been going on for centuries under different designations, including master-gardening’, ‘place-making’, and ‘landscape gardening’. To avoid anachronism, I’m going to call the entire field ‘landscape design’. The ‘top ten’ designers that follow are those I think have been the most influential. These people have shaped your everyday world.

André Le Nôtre (1613 –1700). France’s most famous gardener was employed by Louis XIV to create, at the palace of Versailles, the most extensive gardens in the Western world. Le Nôtre brought the Renaissance style, based upon symmetry and order, to its zenith. Versailles was copied, not only by the designers of other princely gardens, such as those at La Granja in Spain, the Peterhof near St. Petersburg or the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, but by city planners who appropriated its geometry of intersecting axes. The most surprising example is the influential plan for Washington D.C. produced in 1791 by the French engineer Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, who had grown up at Versailles.

The palace of Versailles gardens

Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1716 –1783). Lancelot Brown is credited with changing the face of eighteenth century England. From humble origins, he become the most sought-after landscape designer in the country, undertaking over 250 commissions, including Temple Newsam in Yorkshire, Petworth in West Sussex and Compton Verney in Warwickshire. He swept away many formal gardens to create the naturalistic parkland which subsequently become an icon of Englishness. The style has been emulated worldwide: Munich has its Englischer Garten, while Stockholm has the Hagaparken and Paris the Parc Monceau.

Compton Verney gardens, Warwickshire

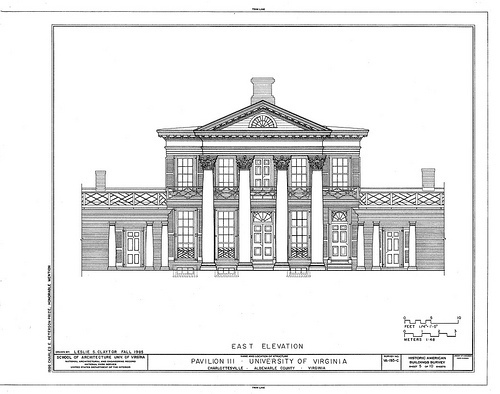

Thomas Jefferson (1743 –1826) Yes, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence and the third President of the United States was also a landscape designer. Not only did he lay out the grounds of his own property at Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia as an ornamental farm, but he also created the influential masterplan for the campus of the University of Virginia. However, his greatest impact upon the American landscape, for better or worse, was his advocacy of the grid for the subdivision of territory and for rational town planning.

Drawing of Pavilion III, The Lawn, University of Virginia campus

William Wordsworth (1770-1850). The poet might seem an unlikely selection, but Wordsworth designed several gardens, not just for his own houses, but also for those of friends. However, my principal reason for including him in this list is that he wrote the Guide to the Lakes, first published in 1810, which was notionally a travel guide, but was just as much a design guide, full of thoughtful advice about how to build – and when not to build – in a sensitive cultural landscape. Wordsworthian values were a significant influence upon the founders of the National Trust and continue to inform thinking about landscape conservation.

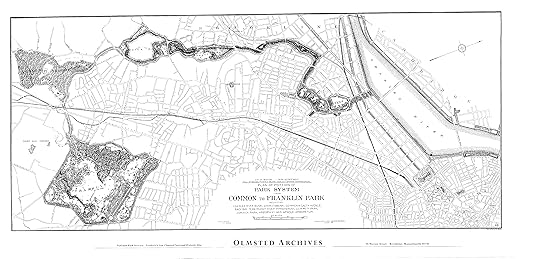

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) Olmsted is often seen as the founding father of the landscape architecture profession. He thought that the creation of pastoral parks within teeming cities could counteract the adverse effects of industrialization and urbanization. In addition to Central Park, New York City, he was the designer of Prospect Park in Brooklyn and the system of linked parks in Boston known as the ‘Emerald Necklace’. His plan for the residential community of Riverside, Illinois, became the template for innumerable suburbs, not all of the same quality. He was also prominent in the campaign to preserve scenic landscapes, such as the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove from development and commercial disfigurement.

The 1894 plan for the Emerald Necklace Park System in Boston, Massachusetts

Thomas Dolliver Church (1902-1978) When a style becomes ubiquitous, we sometimes forget that someone pioneered it. Church was a Californian designer who created elegantly functional ‘outdoor rooms’ for a sybaritic West Coast lifestyle. Those curvaceous, free form swimming pools that appear in American movies and TV shows from the 1950s onwards are Church’s principal contribution to cultural history, but he was an important figure in the rise of Modernist landscape design in the mid twentieth century.

Ian McHarg (1920-2001) Scottish-born McHarg was teaching at the University of Pennsylvania when he wrote Design with Nature, published 1969, the most influential book ever written by a landscape architect. McHarg’s thesis was that we should design our environment in harmony with natural forces, rather than in opposition to them. He pointed out the foolishness of such practices as building houses on floodplains. His advice seems ever more prescient as the world begins to cope with the consequences of climate change.

Peter Latz (1939 -) Landscape designers in many countries have been involved in the reclamation of derelict industrial sites. Latz’s office recognized that reclamation does not need to mean the complete erasure of all history. Instead it can recognise the value of what remains. Most famously, Latz turned a rusting Ruhr valley steelworks into the Landschaftspark Duisburg Nord, where gardens flourish in former ore bunkers, rock-climbers practice on old concrete walls, and scuba-divers plunge into pools created within onetime gasholders. This approach to reclamation, which works with memory and aims to preserve as much of the existing site as possible, is rapidly becoming mainstream.

Landschaftspark Duisburg Nord

James Corner (1961 -) English-born Corner is now Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and principal of the New York based practice, Field Operations. He is perhaps the world’s most celebrated landscape architect, following the extraordinary success of the High Line project on Manhattan, which turned an abandoned railway viaduct into a linear park, visited by around four million people per year. Field Operations are also working on the Freshkills Landfill on Staten Island, transforming it into one of the world’s biggest urban parks.

Kongjian Yu (1963-) Educated at Beijing Forestry University and Harvard Graduate School of Design, Professor Yu now heads the innovative Turenscape practice which has created many remarkable new landscapes in China, including the Zhongshan Shipyard Park, a reclamation project similar in philosophy to Landschaftspark Duisburg Nord. Turenscape makes use of vernacular features of the Chinese agricultural landscape, such as paddy fields and irrigation channels, to create striking new urban parks. Many of Yu’s park designs, such as the Floating Garden at Yongning River Park, demonstrate an ecological approach to flood control.

Ian Thompson is a Chartered Landscape Architect and Reader in Landscape Architecture in the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape at Newcastle University. He worked as a landscape architect from 1979 to 1992, mostly on work related to environmental improvement, derelict land reclamation and urban renewal, before taking up a lecturing post at Newcastle University. He is the author of many books including Landscape Architecture: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: 1) By Michal Osmenda from Brussels, Belgium [CC-BY-2.0] via Wikimedia Commons 2) Graham Taylor [CC-BY-SA-2.0] via Wikimedia Commons 3) By Leslie S. Claytor [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons 4) By Boston Parks Department & Olmsted Architects (National Park Service Olmsted Archives) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons 5) By Martin Falbisoner (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 ] via Wikimedia Commons

The post Ten landscape designers who changed the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in picturesMorality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia law15 facts on African religions

Related StoriesThe rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in picturesMorality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia law15 facts on African religions

May 29, 2014

Ascension and atonement in the New Testament

In the Christian calendar, today is Ascension, the day that marks the translation of Jesus from earth to heaven. While Christmas and Easter are widely celebrated, not just by those actively involved with the church, Ascension will pass unnoticed for most.

This is paralleled both in popular and academic theology or biblical studies: while the significance of the incarnation, and of the death and resurrection of Jesus are discussed at length in relation to salvation, less tends to be said about the Ascension. It is not entirely neglected, but it does not receive the attention that it deserves and its meaning is often limited to the Ascension of Jesus to a position of rule, to the throne of God. This, though, is to neglect some important further threads in the New Testament.

My own recent thinking on the Ascension has been influenced by the work of my colleague, David Moffitt, and by numerous conversations with him as we have taught together. He has highlighted the necessity of a bodily resurrection and Ascension within the logic of the book of Hebrews, precisely because of what Jesus is described as doing in heaven to effect salvation.

Jan Luyken’s Jesus 34. Ascension. Phillip Medhurst Collection. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This epistle represents Jesus as fulfilling the role of a high priest in the heavenly temple on which the earthly one is patterned, enacting a decisive Yom Kippur for his people and performing acts of ritual cleansing for the heavenly sanctuary, using his own blood (see Hebrews 9). Only once he has completed this work does Jesus seat himself (Heb 10:12), prior to which he stands, as all priests do in the work of the temple (Heb 10:11).

For the author of Hebrews, then, the atonement is not completed with the death or even the resurrection of Jesus; it is completed by his work in heaven. Hence, it is important that “we have a great high priest who has gone through the heavens” (Heb 4:14). That underlies his basic and remarkable hope: that we can now draw near to the presence of God, without fear as sinners (Heb 10:19-22).

Hebrews is often seen as an oddity in the New Testament, with its high priestly representation of the atonement, but there are other texts that suggest the same conceptuality is operative, if tacit, more broadly in the New Testament. The description of Jesus as ‘exalted to the right hand of God’ in Acts 2:33, for example, is echoed in Stephen’s vision of heaven in Acts 7:55-56, but there Jesus is twice specified to be ‘standing’ in that position.

Interestingly, a similar emphasis is found in the description of Jesus in Revelation: he is the Lamb “standing” between the throne and heavenly entourage (Rev 5:5). This carries a different set of connotations than does “sitting”; it suggests active service. Once this is taken into account, the priestly imagery of Hebrews begins to appear less eccentric and must instead be taken seriously as an outworking of a common early Christian presentation of atonement, one rooted in Jewish conceptuality.

Alongside this emphasis on the priestly activity of Jesus made possible by the Ascension, another theme emerges in the New Testament: the connection between the Ascension and the gift of the Holy Spirit. The book of Acts, for example, effectively begins with the Ascension of Jesus into heaven (Acts 1:9). This event is linked within the narrative to the subsequent event of Pentecost, the Jewish Feast of Weeks on which the Spirit will be poured out.

Before he ascends, Jesus tells his disciples to wait in Jerusalem for this “promise of the Father” (1:4-5), later understood to be the fulfillment of Joel 2:28ff. This same link between the Ascension of Jesus and the giving of the Spirit is reflected also in Ephesians 4:8, where Psalm 68:18 is quoted and adapted: where, in the original form of the Psalm, God ascends on high in a royal procession and receives gifts from men, here Jesus ascends and gives gifts to men.

Contextually, in Ephesians, this gift (or “grace,” Eph 4:7) comprehensively governs the communal life and mission of the church, associated with the sacramental reality of baptism: “one Lord, one baptism, one Spirit.”

A similar emphasis, though one developed in different terms, is found in John 16:7, where the departure of Jesus is the necessary condition for the coming of the Spirit. In fact, while the Ascension is seldom mentioned in the Fourth Gospel, the bodily absence of Jesus from the community is presented as key to salvation, so that even the joy of the resurrection gives way to an awareness of Jesus’s impending departure.

Thus, in John 19:17, following the resurrection, Jesus tells Mary Magdalene not to cling to him and then directs her specifically to tell the other disciples that he is to ascend. John thereby emphasizes the Ascension and, importantly, he associates it with the coming of the Spirit, by whom God’s presence will be mediated.

This last point is, perhaps, the key to the place that the Ascension has within the theology of the New Testament: access to the presence of God. The priestly work of Jesus is represented in Hebrews as allowing free access to the presence of God in the heavenly temple and is accompanied by the exhortation: “Let us draw near [to God]” (Heb 10:19-22). The gift of the Spirit, meanwhile, is presented as “God’s empowering presence,” to borrow the title of Gordon Fee’s definitive study of the Spirit in Paul’s theology.

Both reflect a powerful theological conviction that the gift of salvation is nothing less than God himself. For those theologians, academic or not, who consider the New Testament to have a normative role in Christian theology, marking Ascension ought to demand reflection on the place that such a doctrine of presence has in their own work.

Grant Macaskill is Senior Lecturer in New Testament Studies at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. His book Union with Christ in the New Testament was published by Oxford University Press (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ascension and atonement in the New Testament appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJohn Calvin’s authority as a prophecyMemorial Day and the 9/11 museum in American civil religionMary Lou Williams, jazz legend

Related StoriesJohn Calvin’s authority as a prophecyMemorial Day and the 9/11 museum in American civil religionMary Lou Williams, jazz legend

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers