Oxford University Press's Blog, page 822

April 16, 2014

Breastfeeding and infant sleep

A woman who gives birth to six children each with a 75% chance of survival has the same expected number of surviving offspring as a woman who gives birth to five children each with a 90% chance of survival. In both cases, 4.5 offspring are expected to survive. Because the large fitness gain from an additional child can compensate for a substantially increased risk of childhood mortality, women’s bodies will have evolved to produce children closer together than is best for child fitness.

Sleeping baby by Minoru Nitta. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Offspring will benefit from greater birth-spacing than maximizes maternal fitness. Therefore, infants would benefit from adaptations for delaying the birth of a younger sib. The increased risk of mortality from close spacing of births is experienced by both the older and younger child whose births bracket the interbirth interval. Although a younger sib can do nothing to cause the earlier birth of an older sib, an older sib could potentially enhance its own survival by delaying the birth of a younger brother or sister.

The major determinant of birth-spacing, in the absence of contraception, is the duration of post-partum infertility (i.e., how long after a birth before a woman resumes ovulation). A woman’s return to fertility appears to be determined by her energy status. Lactation is energetically demanding and more intense suckling by an infant is one way that an infant could potentially influence the timing of its mother’s return to fertility. In 1987, Blurton Jones and da Costa proposed that night-waking by infants enhanced child survival not only because of the nutritional benefits of suckling but also because of suckling’s contraceptive effects of delaying the birth of a younger sib.

Blurton Jones and da Costa’s hypothesis receives unanticipated support from the behavior of infants with deletions of a cluster of imprinted genes on human chromosome 15. The deletion occurs on the paternally-derived chromosome in Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS). Infants with PWS have weak cries, a weak or absent suckling reflex, and sleep a lot. The deletion occurs on the maternally-derived chromosome in Angelman syndrome (AS). Infants with AS wake frequently during the night.

The contrasting behaviors of infants with PWS and AS suggest that maternal and paternal genes from this chromosome region have antagonistic effects on infant sleep with genes of paternal origin (absent in PWS) promoting suckling and night waking whereas genes of maternal origin (absent in AS) promote infant sleep. Antagonistic effects of imprinted genes are expected when a behavior benefits the infant’s fitness at a cost to its mother’s fitness with genes of paternal origin favoring greater benefits to infants than genes of maternal origin. Thus, the phenotypes of PWS and AS suggest that night waking enhances infant fitness at a cost to maternal fitness. The most plausible interpretation is that these costs and benefits are mediated by effects on the interbirth interval.

Postnatal conflict between mothers and offspring has been traditionally assumed to involve behavioral interactions such as weaning conflicts. However, we now know that a mother’s body is colonized by fetal cells during pregnancy and that these cells can persist for the remainder of the mother’s life. These cells could potentially influence interbirth intervals in more direct ways. Two possibilities suggest themselves. First, offspring cells could directly influence the supply of milk to their child, perhaps by promoting greater differentiation of milk-producing cells (mammary epithelium). Second, offspring cells could interfere with the implantation of subsequent embryos. Both of these possibilities remain hypothetical but cells containing Y chromosomes (presumably derived from male fetuses) have been found in breast tissue and in the uterine lining of non-pregnant women.

David Haig is Professor of Biology at Harvard University. he is the author of “Troubled sleep: Night waking, breastfeeding and parent–offspring conflict” (available to read for free for a limited time) in Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health. The arguments summarized above are presented in greater detail in two papers that recently appeared in Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health.

Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health is an open access journal, published by Oxford University Press, which publishes original, rigorous applications of evolutionary thought to issues in medicine and public health. It aims to connect evolutionary biology with the health sciences to produce insights that may reduce suffering and save lives. Because evolutionary biology is a basic science that reaches across many disciplines, this journal is open to contributions on a broad range of topics, including relevant work on non-model organisms and insights that arise from both research and practice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Breastfeeding and infant sleep appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAre you a tax expert?BICEP2 finds gravitational waves from near the dawn of timeVoluntary movement shown in complete paralysis

Related StoriesAre you a tax expert?BICEP2 finds gravitational waves from near the dawn of timeVoluntary movement shown in complete paralysis

Money matters

By Valerie Minogue

Money is a tricky subject for a novel, as Zola in 1890 acknowledged: “It’s difficult to write a novel about money. It’s cold, icy, lacking in interest…” But his Rougon-Macquart novels, the “natural and social history” of a family in the Second Empire, were meant to cover every significant aspect of the age, from railways and coal-mines to the first department stores. Money and the Stock Exchange (the Paris Bourse) had to have a place in that picture, hence Money, the eighteenth of Zola’s twenty-novel cycle.

The subject is indeed challenging, but it makes an action-packed novel, with a huge cast, led by a smaller group of well-defined and contrasting characters, who inhabit a great variety of settings, from the busy, crowded streets of Paris to the inside of the Bourse, to a palatial bank, modest domestic interiors, houses of opulent splendour — and a horrific slum of filthy hovels that makes a telling comment on the social inequalities of the day.

Dominating the scene from the beginning is the central, brooding figure of Saccard. Born Aristide Rougon, Saccard already appears in earlier novels of the Rougon-Macquart, notably in The Kill, which relates how Saccard, profiting from the opportunities provided by Haussman’s reconstruction of Paris, made – and lost – a huge fortune in property deals. Money relates Saccard’s second rise and fall, but Saccard here is a more complex and riveting figure than in The Kill.

Émile Zola painted by Edouard Manet

It is Saccard who drives all the action, carrying us through the widely divergent social strata of a time that Zola termed “an era of folly and shame”, and into all levels of the financial world. We meet gamblers and jobbers, bankers, stockbrokers and their clerks; we get into the floor of the Bourse, where prices are shouted and exchanged at break-neck speed, deals are made and unmade, and investors suddenly enriched or impoverished. This is a world of insider-trading, of manipulation of share-prices and political chicanery, with directors lining their pockets with fat bonuses and walking off wealthy when the bank goes to the wall — scandals, alas, so familiar that it is hard to believe this book was written back in 1890! Saccard, with his enormous talent for inspiring confidence and manipulating people, would feel quite at home among the financial operators of today.Saccard is surrounded by other vivid characters – the rapacious Busch, the sinister La Méchain, waiting vulture-like for disaster and profit, in what is, for the most part, a morally ugly world. Apart from the Jordan couple, and Hamelin and his sister Madame Caroline, precious few are on the side of the angels. But there are contrasts not only between, but also within, the characters. Nothing and no-one here is purely wicked, nor purely good. The terrible Busch is a devoted and loving carer of his brother Sigismond. Hamelin, whose wide-ranging schemes Saccard embraces and finances, combines brilliance as an engineer with a childlike piety. Madame Caroline, for all her robust good sense, falls in love with Saccard, seduced by his dynamic vitality and energy, and goes on loving him even when in his recklessness he has lost her esteem. Saccard himself, with all his lusts and vanity and greed, works devotedly for a charitable Foundation, delighting in the power to do good.

Money itself has many faces: it’s a living thing, glittering and tinkling with “the music of gold”, it’s a pernicious germ that ruins everything it touches, and it’s a magic wand, an instrument of progress, which, combined with science, will transform the world, opening new highways by rail and sea, and making deserts bloom. Money may be corrupting but is also productive, and Saccard, similarly – “is he a hero? is he a villain?” asks Madame Caroline; he does enormous damage, but also achieves much of real value.

Fundamental questions about money are posed in the encounter between Saccard and the philosopher Sigismond, a disciple of Karl Marx, whose Das Kapital had recently appeared — an encounter in which individualistic capitalism meets Marxist collectivism head to head. Both men are idealists in very different ways, Sigismond wanting to ban money altogether to reach a new world of equality and happiness for all, a world in which all will engage in manual labour (shades of the Cultural Revolution!), and be rewarded not with evil money but work-vouchers. Saccard, seeing money as the instrument of progress, recoils in horror. For him, without money, there is nothing.

If Zola vividly presents the corrupting power of money, he also shows its expansive force as an active agent of both creation and destruction, like an organic part of the stuff of life. And it is “life, just as it is” with so much bad and so much good in it, that the whole novel finally reaffirms.

Valerie Minogue has taught at the universities of Cardiff, Queen Mary University of London, and Swansea. She is co-founder of the journal Romance Studies and has been President of the Émile Zola Society, London, since 2005. She is the translator of the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of Money by Émile Zola.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Émile Zola by Edouard Manet [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Money matters appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBook vs movie: Thérèse Raquin and In SecretAn Irish literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsSherlock Holmes’ beginnings

Related StoriesBook vs movie: Thérèse Raquin and In SecretAn Irish literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsSherlock Holmes’ beginnings

April 15, 2014

A conversation with Alodie Larson, Editor of Grove Art Online

We are delighted to present a Q&A with the Editor of Grove Art Online, Alodie Larson. She began at Oxford last June, coming from JSTOR, where she spent four years as part of their editorial team, acquiring new journals for the archive. In the below interview, you’ll get to know Alodie as Editor, and also learn her thoughts on art history research and publishing. You can also find her Letter from the Editor on Oxford Art Online.

Can you tell us a little about your background?

When I was young, I would draw house plans (with elevations in the shape of animals) and make artwork with whatever I could find. In college, I studied architecture and the history of art; I completed my MA at the Courtauld Institute of Art, focusing on the architecture of Georgian England. Afterward, I moved to New York and lived in a comically small apartment with my brilliant friend who studied with me in London. She worked at Christie’s, and she kept me from straying too far from the art world while I worked at Random House. I began in the audio/digital department and later moved to the children’s division; I was lucky to learn from talented editors who were generous with their time. I became intimately familiar with Louis L’Amour novels, and I read Twilight when it was a stack of 8 ½ x 11 copy paper. I joined JSTOR in 2009, where I managed their list of journals in art and architecture. I contributed to a project to digitize a group of rare art journals like 291 and The Crayon, as well as to an effort to build a database of historical auction catalogs, all of which JSTOR made freely available along with their other content in the public domain. I also worked on business and sociology, which helped me to appreciate how research methods differ between disciplines. I am delighted to be here at Oxford as the steward of the Grove Dictionary of Art. In my free time I like to travel, visit museums, go to the opera, and refinish furniture. I am still somewhat disappointed that my current house plan is not shaped like a giraffe.

What is your favorite piece of art, of all time, and why?

I love Bernini’s David – the artist’s skill and inventiveness make this sculpture a singularly perfect object. In Bernini’s hands, marble seems to melt, as if it could be smoothed and stretched to his design. Grove’s biography explains this gift: “He felt that one of his greatest achievements was to have made marble appear as malleable as wax and so, in a certain sense, to have combined painting and sculpture into a new medium, one in which the sculptor handles marble as freely as a painter handles oils or fresco.” Unlike Michelangelo’s calm, anticipatory David, Bernini’s figure projects determination and energy. His body twists in motion, and as you circle him, you feel you are both being wound up together. I leave this sculpture feeling as if I have been flung out of the gallery, propelled by his purposeful strength.

David stands in my favorite museum, the Galleria Borghese, which adds to its grandeur as it is the original location intended for the sculpture. In the early 17th< century, Cardinal Scipione Borghese oversaw construction of the building—then the Villa Borghese—and commissioned David as well as a number of other stellar works from Bernini including Apollo and Daphne and Pluto and Proserpina. I relish seeing these sculptures in the magnificent home of Scipione’s original collection.

Galleria Borghese, Rome. Photo courtesy of the Alodie Larson.

Since it’s impossible to get someone with an art background to answer this question briefly, I must add that I also particularly admire the work of Eduard Vuillard, Mark Rothko, Grant Wood, James Turrell, William Morris, Daniel Burnham, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Franz Kline, Xu Bing, and McKim, Mead & White. Closer to home, I have two favorite works of art that belong to me. The first is a watercolor sketch of Piccadilly Circus that I bought at a market in the courtyard of the Basilica of Sant’Ambrogio in Milan. With minimal strokes it evokes the London crossroads on a rainy night in the late 50s (back when Gordon’s Gin and Wrigley’s Chewing Gum took up prime real estate in the neon collage).

Piccadilly Circus in London, 1962. Photo by Andrew Eick. Creative Commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The second is a watercolor illustration of “Dradpot the Inverted Drool” drawn by my grandfather, Max V. Exner. He devoted his life to music but was a terrific artist as well, and our family lore has it that he was offered a job with Walt Disney Studios in the 1930s when a member of the company saw him doodling in a restaurant.

Also, in a beautiful, financially responsible future, I will have enough disposable income to buy an original work by David Shrigley. I urge him to try to become less famous so that I can afford this.

What is your favorite article in Grove Art Online?

I’m grateful that this role allows me to learn about artists I’ve never studied, and my favorite articles to read are those on subjects with which I’m not particularly familiar. Our forthcoming update includes new biographies on an outstanding group of contemporary artists from Nigeria, Kenya, Sudan, Ghana, Senegal, and South Africa, which I have enjoyed.

I am partial to the articles written by some of my favorite architectural historians, particularly Leland M. Roth, whose Understanding Architecture (1993) is, I think, one of the most engaging introductory texts. His Grove article on the urban development of Boston gives a great overview of the subject. I also like David Watkin’s article on Sir John Soane. An excellent summary of Soane’s life and work, it is an absorbing narrative with entertaining flourishes. (“Despite Soane’s high professional standing, his idiosyncratic style was often ridiculed by contemporaries in such phrases as ‘ribbed like loins of pork’.”) I have always admired Soane’s work and his unconventional museum.

The breakfast parlour at Sir John Soane’s Museum as pictured in the Illustrated London News in 1864. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

What are some of the challenges of transitioning art history resources to an online environment?

Together, Grove and Benezit contain over 200,000 entries and images, and it is a challenge to organize that much information online in a clear, intuitive way that ensures researchers will find the articles they need. Many Grove entries first appeared in the print publication, The Dictionary of Art, and the article titles weren’t designed to fit well with modern keyword searches. Important essays can be buried within several layers of subheadings in long articles, sometimes with only date ranges as section titles. For a print work, it makes sense; you’d want all of the articles on a topic or region to be gathered together and located within the same physical volume. However, in an online environment, ideal heading structure would aid successful keyword matches and avoid cumbersomely long entries.

Despite the challenges, an online environment offers more powerful research options. Both Grove and Benezit are organized under a robust taxonomy, and this information allows users to narrow content by categories such as art form, location, or period. Rich search functionality and linking helps users to move between topics more swiftly than print research would permit. An online environment also allows our resource to respond quickly to new developments. We constantly update and expand the body of articles in our encyclopedia (though updates are not instantaneous, as our content is peer-reviewed, supervised by our distinguished Editorial Board and Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Nicola Courtright).

Oxford Art Online hosts thousands of images. Are there any challenges in hosting these on the site?

Yes, as with our articles, the volume of objects presents a challenge. Grove Art contains over 7,000 images, including many well-known artworks that would be discussed as part of an introductory survey course. Keyword searches usually connect researchers with the images relevant to their work, but we’re working to develop more powerful tools with which to both search and view images.

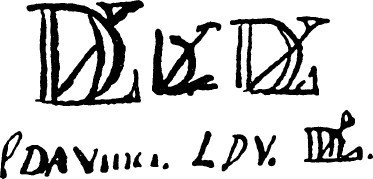

Obtaining image permissions can also be a challenge, but we are grateful for our partnerships with organizations like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Resource, Bridgeman Art Library, and the National Gallery of Art, which have brought a rich group of images to Grove. Benezit, too, benefits from important partnerships with the Frick Art Reference Library and ArtistSignatures.com, which provide thousands of artists’ portraits and signatures on Oxford Art Online.

How do you envision art history research being done in 20 years?

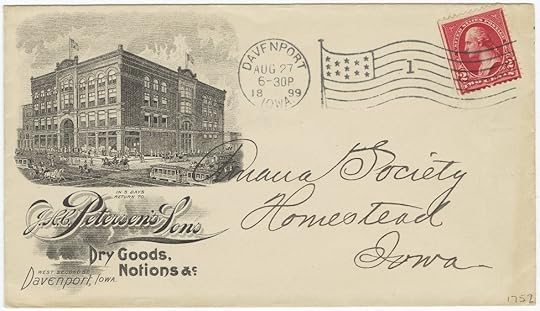

I believe research in art history will become more collaborative, interdisciplinary, and international. Art libraries have undertaken enormously useful digitization projects, making objects in their collections available to scholars in far flung locations. I’m impressed with primary source projects like the collaboration between the Met and the Frick libraries to digitize the exhibition materials of the Macbeth Gallery, and Yale’s Blue Mountain Project, which digitized a collection of avant-garde art, music, and literary periodicals from 1848-1923. A number of other university libraries have excellent digital collections for art research, including the University of Washington, the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin, Harvard University, University of Wisconsin, and Columbia University, which hosts the addictively interesting Robert Biggert Collection of Architectural Vignettes on Commercial Stationery.

Courtesy of The Biggert Collection of Architectural Vignettes on Commercial Stationery, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

Whether through local collections or collaborative projects like the HathiTrust, JSTOR, and the DPLA, libraries and publishers are bringing a terrific breadth of important materials online. As content becomes more accessible, I think researchers will select online resources based on the caliber of their material and on the functionality provided the platform. Even as publishers’ brands may fall further behind the façade of library discovery services, I believe scholars will continue to value sources they can trust to maintain high standards of quality.

Art has always been an interdisciplinary field, involving history, politics, economics, and cultural exchange. In the coming years, I think it will be important to emphasize how art connects with these other fields. With the current national focus on careers in science and technology, art is sometimes cast as an academic luxury, but it is not. Its study involves issues fundamentally relevant to all of us. In the words of Albert Einstein: “All religions, arts and sciences are branches of the same tree. All these aspirations are directed toward ennobling man’s life, lifting it from the sphere of mere physical existence and leading the individual toward freedom.”

Alodie Larson is the Editor of Grove Art and Oxford Art Online. Before joining Oxford, she studied the architecture of Georgian England at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London and worked for Random House and JSTOR.

Libraries are a vital part of our communities. They feed our curiosity, bolster our professional knowledge, and provide a launchpad for intellectual discovery. In celebration of these cornerstone institutions, we are offering unprecedented free access to our Online Resources, including Oxford Art Online, in the United States and Canada to support our shared mission of education.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A conversation with Alodie Larson, Editor of Grove Art Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLudovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from Grove Art OnlineStreet Photography from Grove Art OnlineWorld Art Day photography contest

Related StoriesLudovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from Grove Art OnlineStreet Photography from Grove Art OnlineWorld Art Day photography contest

Leonardo da Vinci myths, explained

Leonardo da Vinci was born 562 years ago today, and we’re still fascinated with his life and work. It’s no real mystery why – he was an extraordinary person, a genius and a celebrity in his own lifetime. He left behind some remarkable artifacts in the form of paintings and writings and drawings on all manner of subjects. But there’s much about Leonardo we don’t know, making him susceptible to a number myths, theories, and entertaining but inaccurate representations in popular culture. The following are some of my favorites.

Leonardo da Vinci, Presumed Self Portrait, circa 1512. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #1 – Leonardo was gay.

Leonardo’s possible homosexuality is one of the more prevalent – and more plausible – myths circulating about the artist, and has the backing of none other than Sigmund Freud. There’s no way of knowing Leonardo’s sexual orientation for sure, but he isn’t known to have had romantic relationships with any women, never married, and in 1476 was accused (but later cleared) of charges of sodomy – then a capital crime in Florence. Scholars’ opinions on the issue fall along a spectrum between “maybe” and “very probably”.

Conclusion: Maybe true.

Myth #2 – Leonardo wrote backward to keep his ideas secret, and his notebooks weren’t “decoded” until long after his death.

For all his skill, Leonardo was not a prolific painter – the major part of his surviving output is in the form of his notebooks filled with theoretical and scientific writings, notes, and drawings. His strange habit of writing backward in these notebooks has been used to perpetuate the image of the artist as a mysterious, secretive person. But in fact it’s much more likely that Leonardo wrote this way simply because he was left-handed, and found it easier to write across the page from right to left and in reverse. No decoding is necessary – just a mirror. Leonardo’s theoretical writings and other notes were preserved by his follower and heir Francesco Melzi, and were widely known, at least in artistic circles, during the 16th and 17th centuries. Published extracts began appearing in 1651.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #3 – Leonardo put “secret” codes and symbols in his works.

I’d rather not get into all the problems with The Da Vinci Code too much, but I have to credit this 2003 book, by renowned author Dan Brown, for a lot of these theories. Aside from the fact that the book is full of factual errors (example: Leonardo’s “hundreds of Vatican commissions,” which actually number in the vicinity of zero) and twists the historical record, its readings of Leonardo’s artworks are based on some fundamentally flawed conceptions about the making, meaning, and purpose of art in the Italian Renaissance. In Leonardo’s world, paintings like the Last Supper in Milan were made according to patrons’ requirements, with very specific Christian meanings to be conveyed. Despite Leonardo’s artistic innovations, the content of his religious paintings and portrayal of religious figures (with the exception of some details in an altarpiece from the 1480s) were not untraditional.

Conclusion: False.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa, between 1503-1505. Louvre. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #4 – The Mona Lisa is a self-portrait/male lover in disguise/woman with high cholesterol.

Martin Kemp has observed, “The silly season for the Mona Lisa never closes.” The ridiculous theories about this painting abound. Here’s what we can say with reasonable certainty: Leonardo started the painting, probably a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, a merchant’s wife, while in Florence around 1503. For unknown reasons, he didn’t deliver it to the patron, however, and it ended up in the possession of his workshop assistant Salai (who some think was Leonardo’s lover – again, without evidence). There’s no reason to think that Leonardo recorded in this painting his own features or those of Salai, even if, as many art historians believe, he continued to work on the painting after he left Florence for Milan and then France. In a theory that deviates from the usual speculation about the identity of the sitter, an Italian scientist thinks that the way Leonardo portrayed the sitter shows she had high cholesterol. Right, because Renaissance paintings are straightforward, scientific images, pretty much just like MRIs and X-rays.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #5 – Leonardo made the image of Christ on the Shroud of Turin.

The Shroud of Turin is a relic purported to be the shroud that Christ’s body was buried in after the Crucifixion. According to its legend, the image of his body was miraculously transferred to the cloth when he was resurrected. The idea that Leonardo forged it depends on claims that the proportions of Christ’s face as depicted on the shroud match those in a drawing that is thought to be a self-portrait by the artist, and that Leonardo devised a photographic process that transferred the image of his face to the shroud. The fact that the shroud dates to at least the mid-14th century, a hundred years before Leonardo’s birth, just makes this already kooky theory even harder to buy. I’ll admit, though, that I haven’t read the whole book explaining it … and I’m not going to.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #6 – Leonardo was a vegetarian.

Vegetarianism would have been pretty unthinkable in Renaissance Italy (and veganism just plain absurd); people probably ate about as much meat as they could afford. The most commonly cited quote used to back up this claim is taken from a novel (see p. 227) and often misattributed to Leonardo himself. None of Leonardo’s own writings or early biographies mentions any unconventional eating habits. There’s really only one documentary source that might be relevant, a letter written by a possible acquaintance of the artist, who compares Leonardo to people in India who don’t eat meat or allow others to harm living things. Pretty tenuous, but vegetarians love to claim him.

Conclusion: Probably false.

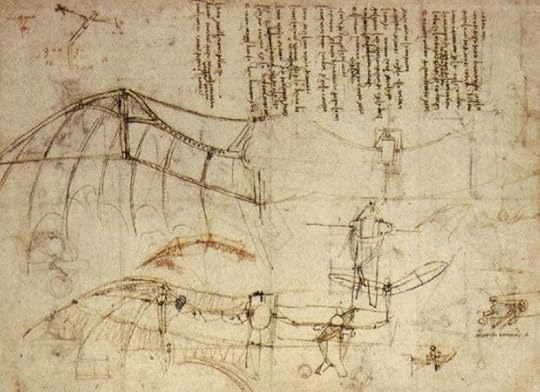

Myth #7 – Leonardo invented bicycles, helicopters, submarines, and parachutes.

It’s true that Leonardo was fascinated with mechanics, aerodynamics, hydrodynamics, flight, and military engineering, which he touted in his famous letter to Ludovico Sforza seeking a position at the court of Milan. Leonardo’s notebooks contain many designs for machines and devices related to these explorations. But these were, for the most part, probably not ideas that Leonardo considered thoroughly enough to actually build and demonstrate. In the case of the bicycle, the drawing was likely made by someone else, and might even be a modern forgery.

Conclusion: Not so much.

Leonardo da Vinci, Design for a Flying Machine, 1488. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #8 – Leonardo built robots.

While it sounds nutty, this one’s not so far off the mark, if you consider automatons – mechanical devices that seem to move on their own – to be robots. In a plot line of the cable fantasy drama Da Vinci’s Demons, Leonardo constructs a flying mechanical bird to dazzle the crowds gathered in the Cathedral piazza for Easter. A reliable historical record instead points to a lion that Leonardo made for the King of France’s triumphal entry into Milan in 1509. One observer’s description reads:

When the King entered Milan, besides the other entertainments, Lionardo da Vinci, the famous painter and our Florentine, devised the following intervention: he represented a lion above the gate, which, lying down, got onto its feet when the King came in, and with its paw opened up its chest and pulled out blue balls full of gold lilies, which he threw and strewed about on the ground. Afterwards he pulled out his heart and, pressing it, more gold lilies came out … Stopping beside this spectacle, [the King] liked it and took much pleasure in it.

Wow.

Conclusion: True.

If you’re interested in learning more about Leonardo, including the current locations of his works, read his biography from the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, or, for a longer treatment, pick up the accessible but smart book by leading expert Martin Kemp.

Kandice Rawlings is Associate Editor of Oxford Art Online and the Benezit Dictionary of Artists. She holds a PhD in art history from Rutgers University.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Leonardo da Vinci myths, explained appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLeonardo da Vinci from the Benezit Dictionary of ArtistsLudovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from Grove Art OnlineWorld Art Day photography contest

Related StoriesLeonardo da Vinci from the Benezit Dictionary of ArtistsLudovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from Grove Art OnlineWorld Art Day photography contest

Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from Grove Art Online

In celebration of World Art Day, we invite you to read the biography of Ludovico Sforza, patron of Leonardo Da Vinci among other artists, as it is presented in Grove Art Online.

(b Abbiategrasso, 3 Aug 1452; reg 1494–99; d Loches, Touraine, 27 May 1508).

Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. Sforza Altarpiece, 1495

Son of (1) Francesco I Sforza and (3) Bianca Maria Sforza. In 1480, several years after the death of his brother (4) Galeazzo Maria Sforza in 1476, he succeeded in gaining control of the regency but did not become duke in name until his nephew Gian Galeazzo Sforza died in 1494. His commissions, both public and private, were divided between Lombard and Tuscan masters. Milanese architects were responsible for many of his most important projects, including the construction of the Lazzaretto (1488–1513) and S Maria presso S Celso (begun 1491 by Giovanni Giacomo Dolcebuono) in Milan, and a farm complex, known as the Sforzesca, outside Vigevano. Several prominent Lombard sculptors, in particular Giovanni Antonio Amadeo, were commissioned to work on the façade of the Certosa di Pavia. Of the artists Ludovico encouraged to come to Lombardy, an undated letter reveals that he was considering Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, Perugino and Ghirlandaio as court artists. About 1482 Leonardo da Vinci arrived in Milan, where he remained as an intimate member of Ludovico’s household for 18 years. As court painter, Leonardo is documented as having portrayed two of Ludovico’s mistresses, Lucrezia Crivelli and Cecilia Gallerani. The latter may be identified with the painting Portrait of a Lady with an Ermine (c. 1490–91; Kraków, Czartoryski Col.). Much of his work was for such courtly ephemera as the designs for the spectacle Festa del Paradiso, composed in 1490. Another commission of which nothing survives was for a bronze equestrian statue honouring Ludovico’s father, which Leonardo worked on in the 1490s. A surviving work by Leonardo for the Duke is the Sala delle Asse (1498) in the Castello Sforzesco, Milan, where motifs of golden knots are interspersed among vegetation and heraldic shields.

Other Tuscans at work in Milan during the 1490s included Donato Bramante. As a painter, Bramante produced an allegorical figure of Argus (1490–93) in the Castello Sforzesco (in situ). The development of the piazza, tower and castle at Vigebano in the 1490s, one of the most important campaigns of urban planning in the Renaissance, was the work of Bramante, working perhaps with Leonardo, under Ludovico’s supervision. Ludovico also took day-to-day responsiblity for projects financed by his brother (6) Cardinal Ascanio Maria Sforza, for example Bramante’s work on the new cathedral in Pavia and the monastic quarters (commissioned 1497) at S Ambrogio, Milan. The illuminator Giovanni Pietro Birago was also active in Ludovico’s court, producing, among others, several copies (e.g. London, BL. Grenville MS. 7251) of Giovanni Simonetta’s life of Francesco Sforza I, the Sforziada.

Ludovico’s plans were destroyed by the invasion of Louis XII, King of France, in August 1499. Ludovico escaped, to return in February 1500, but following his final defeat and capture in April that year, he was confined to a prison in France for the remainder of his life.

Bibliography

E. Salmi: ‘La Festa del Paradiso di Leonardo da Vinci e Bernardo Bellincioni’, Archv Stor. Lombardo, xxxi/1 (1904), pp. 75–89

F. Malaguzzi Valeri: La corte di Ludovico il Moro: La vita privata e l’arte a Milano nella secunda metà del quattrocento, 4 vols (Milan, 1913–23)

S. Lang: ‘Leonardo’s Architectural Designs and the Sforza Mausoleum’, J. Warb. & Court. Inst., xxxi (1968), pp. 218–33

A. M. Brivio: ‘ Bramante e Leonardo alla corte di Ludovico il Moro’, Studi Bramanteschi. Atti del congresso internazionale: Roma, 1970, pp. 1–24

C. Pedretti: ‘The Sforza Sepulchre’, Gaz. B.-A., lxxxix (1977), pp. 121–31

R. Schofield: ‘Ludovico il Moro and Vigevano’, A. Lombarda, n. s., lxii/2 (1981), pp. 93–140

M. Garberi: Leonardo e il Castello Sforzesco di Milano (Florence, 1982)

Ludovico il Moro: La sua città e la sua corte (1480–1499) (exh. cat., Milan, Archv Stato, 1983)

Milano e gli Sforza: Gian Galeazzo Maria e Ludovico il Moro (1476–1499) (exh. cat., ed. G. Bologna; Milano, Castello Sforzesco, 1983)

Milano nell’età di Ludovico il Moro. Atti del convegno internazionale: Milano, 1983

C. J. Moffat: Urbanism and Political Discourse: Ludovico Sforza’s Architectural Plans and Emblematic Imagery at Vigevano (diss., Los Angeles, UCLA, 1992)

R. Schofield: ‘Ludovico il Moro’s Piazzas: New Sources and Observations’, Annali di architettura, iv–v (1992–3), pp.157–67

L. Giordano: ‘L’autolegittimazione di una dinastia: Gli Sforza e la politica dell’ immagine’, Artes [Pavia], i (1993), pp. 7–33

P. L. Mulas: ‘”Cum apparatu ac triumpho quo pagina in hoc licet aspicere”: I’investitura ducale di Ludovico Sforza, il messale Arcimboldi e alcuni problemi di miniatura Lombarda’, Artes [Pavia], ii (1994), pp. 5–38

V. L. Bush: ‘The Political Contexts of the Sforza Horse’, Leonardo da Vinci’s Sforza Monoument Horse: The Art and the Engineering, ed. D. C. Ahl (London, 1995), pp. 79–86

A. Cole: Virtue and Magnificence: Art of the Italian Renaissance Courts (New York, 1995)

L. Giordano, ed.: Lucovicus dux (Vigevano, 1995)

G. Lopez: ‘Un cavallo di Troia per Milano’, Achad. Leonardo Vinci: J. Leonardo Stud. & Bibliog. Vinciana, viii (1995), pp. 194–6

E. S. Welch: Art and Authority in Renaissance Milan (New Haven, 1995)

L. Giordano: ‘Ludovico Sforza, Bramante e il nuovo corso del Po 1492–1493′, Artes (Pavia), v (1997), pp. 198–205

G. Cislaghi: ‘Leonardo da Vinci: La misura del borgo di Porta Vercellina a Milano’, Dis. Archit., xxv–xxvi (2002), pp. 11–17

E. McGrath: ‘Ludovico il Moro and his Moors’, J. Warb. & Court. Inst., lxv (2002), pp. 67–94

L. Syson: ‘ Leonardo and Leonardism in Sforza Milan’, Artists at Court: Image-making and Identity: 1300–1550, ed. S. J. Campbell (Chicago, 2004), pp. 106–23

L. Giordano: ‘ In capella maiori: Il progetto di Ludovico Sforza per Santa Maria delle Grazie’, Demeures d’éternité: églises et chapelles funéraires aux XVe et XVIe siècles, ed. J. Guillaume (Paris, 2005), pp. 99–114

E. S. Welch

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from Grove Art Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLeonardo da Vinci from the Benezit Dictionary of ArtistsStreet Photography from Grove Art OnlineWorld Art Day photography contest

Related StoriesLeonardo da Vinci from the Benezit Dictionary of ArtistsStreet Photography from Grove Art OnlineWorld Art Day photography contest

Are you a tax expert?

Today is 15 April or Tax Day in the United States. In recognition of this day we compiled a free virtual issue on taxation bringing together content from books, online products, and journals. The material covers a wide range of specific tax-related topics including income tax, austerity, tax structure, tax reform, and more. The collection is not US-centered, but includes information on economies across the globe. Be sure to take a moment to view this useful online resource today.

Today is 15 April or Tax Day in the United States. In recognition of this day we compiled a free virtual issue on taxation bringing together content from books, online products, and journals. The material covers a wide range of specific tax-related topics including income tax, austerity, tax structure, tax reform, and more. The collection is not US-centered, but includes information on economies across the globe. Be sure to take a moment to view this useful online resource today.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Oxford University Press has compiled a new virtual issue on taxation that brings together content from books, online products, and journals. Start browsing this timely and useful resource today!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Tax calculator and pen. © Elenathewise via iStockphoto.

The post Are you a tax expert? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe political economy of skills and inequalityShakespeare’s 450th birthday quizThe quest for ‘real’ protection for indigenous intangible property rights

Related StoriesThe political economy of skills and inequalityShakespeare’s 450th birthday quizThe quest for ‘real’ protection for indigenous intangible property rights

Leonardo da Vinci from the Benezit Dictionary of Artists

In celebration of World Art Day and Leonardo da Vinci’s birthday, we invite you to read the biography of da Vinci as it is presented in the Benezit Dictionary of Artists.

Italian, 15th – 16th century, male.

Active from 1515 in France.

Born 15 April 1452, in Anchiano, near Vinci; died 2 May 1519, in Clos-Lucé, near Amboise, France.

Painter, sculptor, draughtsman, architect, engineer. Religious subjects, mythological subjects, portraits, topographic subjects, anatomical studies.

Leonardo da Vinci was the illegitimate son of the Florentine notary Ser Piero da Vinci, who married Albiera di Giovanni Amadori, the daughter of a patrician family, in the year Leonardo was born. Little is known about the artist’s natural mother, Caterina, other than that five years after Leonardo’s birth she married an artisan from Vinci named Chartabriga di Piero del Veccha. Leonardo was raised in his father’s home in Vinci by his paternal grandfather, Ser Antonio. Giorgio Vasari discusses Leonardo’s childhood at length, noting his aptitude for drawing and his taste for natural history and mathematics. Probably around 1470, Leonardo’s father apprenticed him to Andrea del Verrocchio; two years later,Leonardo’s name appears in the register of Florentine painters. Although officially a painter in his own right, Leonardo remained for a further five years or so in Verrocchio’s workshop, where Lorenzo di Credi and Pietro Perugino numbered among his fellow students.

In 1482, Leonardo went to Milan to work in the court of Duke Ludovico Sforza and remained there until 1499, returning to Florence after brief visits to Venice and Mantua. During his second Florentine period, Leonardo gained notoriety, primarily as the result of two cartoons he worked up and put on public display. In 1508, Leonardo returned to Milan to work for the French rulers there and complete an altarpiece commission he had begun during an earlier stay. The artist made his first trip to Rome in 1513 and was involved there with military projects for Giuliano de’ Medici (the duke of Nemours and brother of Pope Leo X). Through the pope, Leonardo may have met the French king Francis I, who was Leonardo’s patron in the last few years of his life. The artist died near Amboise and was buried there, in the church of St Florentin. Because of these circumstances, several of Leonardo’s most treasured works, including the Mona Lisa, ended up in the French royal collection and are now preserved in the Louvre.

A few works can be attributed to the period of Leonardo’s training with Verrocchio: a landscape drawing dated 1473 and part of Verrocchio’s Baptism of Christ (both Uffizi Gallery), namely the angel at the far left of the composition. In January 1478, now an independent painter, he was commissioned by the city of Florence to paint an altarpiece for the S Bernardo Chapel in the Palazzo Vecchio, which he did not complete. The following year, Leonardo made a drawing of the hanged body of an assassin involved in the Pazzi Conspiracy to overthrow the Medici government, which may have been connected with another state commission. In March 1480, he was retained to paint an altarpiece for the main altar in the monastery of S Donato a Scopeto, most likely the unfinished Adoration of the Magi, a dynamic reimagining of the subject. It appears that around this time he also produced numerous Madonna studies and his Portrait of Ginevra dei Benci, the first of his many captivating portraits of women.

In 1481, Leonardo wrote a letter to the new ruler of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, asking for a position at court. It is almost entirely devoted to his knowledge of military engineering and ideas for new weapons; the last paragraph briefly mentions that he is an able painter and can also assist in the completion of an equestrian monument of Ludovico’s father, Francesco, which had been planned but not begun. Leonardo arrived in Milan by 1483, perhaps with Medici assistance, and was contracted to paint an image of the Virgin for an altarpiece for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception’s chapel in S Francesco Grande. This commission resulted in a protracted legal battle and two versions of the painting, the so-called Virgin of the Rocks; the first version, painted between 1483 and 1486, is in the Louvre, and the second, painted primarily in the 1490s, is in the National Gallery, London. The history of the two paintings and the authorship of the later version are much disputed.

During this period, Leonardo received commissions across a wide spectrum. He built stage equipment and devices used for the marriage ceremony of Gian Galeazzo Sforza; he travelled to Padua to supervise construction of the cathedral; he designed costumes for the festivities arranged to celebrate the marriage of Ludovico Sforza to Beatrice d’Este; and he drew a design for the crossing tower of the Milan Cathedral (1487). He made two portraits of women supposed to be Ludovico’s mistresses, Cecilia Gallerani (or Lady with an Ermine) and Lucrezia Crivelli (or La Belle Ferronnière).

Around 1495, Leonardo set to work planning decorations for the Castello Sforzesco. At the start of 1496, Leonardo and Ludovico, by that time the duke of Milan, quarrelled, and the duke repeatedly tried to entice Pietro Perugino as a replacement for Leonardo. Some two years later, the duke andLeonardo reconciled, and Leonardo started working again on the ducal palace and supervising fresco decorations for the Sala delle Asse. While out of favour with the duke, Leonardo had occupied himself with painting a monumental fresco of the Last Supper for the refectory of the Milan monastery of S Maria delle Grazie. In his life of Leonardo, Vasari asserts that execution of this fresco was fraught with difficulty. Leonardo’s use of an experimental medium in order to achieve the naturalistic effects of oil painting caused the fresco to deteriorate rapidly, with much of the original composition quickly being lost. By 1545, it was reported to have already been partially destroyed; three centuries later it was evident that years of neglect, humidity, and inept restorations (attempts at complete restoration were recorded in 1726 and 1770) had only served to make matters worse. A further and more successful attempt at restoration was undertaken in the early years of the 20th century, and the spirit of the original was recaptured, at least partially. The most recent restoration, begun in 1979, was completed in 1999. Fortunately, the original appearance of the Last Supper survives in the form of excellent copies made by students of Leonardo, possibly under his supervision. Among these is a copy reproducing the dimensions of the original (15 by 28 feet [4.5 by 8.60 metres]), painted around 1510 by Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli for the Carthusian church in Pavia and now in London’s Royal Academy. Another detailed reproduction was made by Marco d’Oggiono, commissioned by Connétable de Montmorency for the chapel at the castle of Écouen and now in the Louvre. Despite the fresco’s condition problems, it is one of Leonardo’s best-known and most influential works. The painting is admired for the variety of expressions and poses, the mastery with which Leonardocaptured the most dramatic moment of the biblical story, and the mathematical clarity and regularity of the space, which is conceived as an extension of the refectory (dining hall) it decorates.

Although in 1483 Leonardo had made a clay model of an equestrian sculpture of Francesco Sforza that was erected for the wedding celebrations of Bianca Maria Sforza and Emperor Maximilian, he did not begin work in earnest on the bronze Sforza monument until the 1490s. In fact, Ludovico wrote in a 1489 letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici that he feared Leonardo would not be able to cast the sculpture and requested Lorenzo to provide him with expert bronze sculptors as replacements. Although no finished sculptures by Leonardo have been identified, his training in Verrocchio’s workshop meant he would have received some degree of instruction on techniques of bronze casting; during the 1470s and 1480s, Verrocchio was occupied with various projects in bronze, including an equestrian monument in Venice. Later, during a stay in Florence in 1506–1507, Leonardo may have been involved the design of Giovanni Francesco Rustici’s bronze group St John the Baptist Preaching for the exterior of the Florence Baptistery. In any case, the Sforza monument was never cast, and the largest clay model that Leonardo completed suffered serious damage when French troops entered Milan in September 1499 and archers elected to use it for target practice. However, many drawings, both studies for the composition and technical designs for the casting, survive. The monument, if completed, would no doubt have been a major achievement, both artistically and technically.Leonardo planned a dynamic and highly innovative composition with a rearing horse and a fallen enemy beneath its forelegs, and the statue was to be colossal in scale. The project was abandoned when Leonardo fled the French invasion.

In December 1499, Leonardo went to Mantua with the mathematician Fra Luca Pacioli. There,Leonardo produced a highly finished drawing for a portrait of Isabella d’Este that was either never executed or has been lost. He then spent a short time in Venice before returning to Florence in April 1500. That same month, he finished a cartoon for a major work entitled Virgin and Child with St Anneand displayed it to adoring crowds at SS Annunziata. The cartoon is untraced but is thought the have been related to a drawing now in the National Gallery, London, and a painting of the same subject now in the Louvre. It was around this period (1500-1503) that Leonardo also began painting the portrait of Mona Lisa (or La Gioconda), generally believed to have been the wife of the Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo. According to Vasari, Leonardo worked on the Mona Lisa for the better part of four years, but he never delivered it to its patron, bringing it with him to France and perhaps working on it intermittently into his late years. He also made studies for Leda and the Swanthat were copied by his students and Raphael; the final painting is untraced and may have been finished much later, during Leonardo’s sojourn in Rome.

The end of 1502 saw Leonardo inspecting fortifications in the Romagna in his new capacity as senior military architect and general engineer in the service of Cesare Borgia. He was abruptly removed from this post in October of the same year when a rebellion broke out in the duchy. April 1503 foundLeonardo back in Florence and, in July of that year, the Republic of Florence dispatched him to an encampment near Pisa to conduct a survey on how the Arno River could be diverted behind Pisa (so that the city, then under siege by Florence, could be deprived of access to the sea). Later that year, in October, he embarked on a major decorative composition for the new Salone dei Cinquecento (Hall of the Five Hundred) in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The chosen theme was the victory of Florence over Milan at the Battle of Anghiari in 1440. This monumental work, like its intended complementary painting by Michelangelo of the Battle of Cascina, remained unfinished. Leonardowas commissioned to paint the mural in 1502 and was working on the fresco by 1504. Once again, technical problems frustrated him, notably the poor state of the wall surface he painted and again another experimental technique using oils, and he abandoned the project in 1506. Both the cartoon and the mural were avidly studied by younger artists and some of its appearance can be surmised from drawn and engraved studies. In 1563, Vasari covered the ruinous painting with a new fresco. A project to discover Leonardo’s painting beneath the later fresco using infrared and laser technology was launched in 2005, in the hopes that Vasari preserved it by leaving a gap between the Battle of Anghiari and the plaster for his own fresco.

Leonardo then spent a short time in Milan, perhaps to settle his long-standing commission for theVirgin of the Rocks, before returning to Florence, where he painted a Virgin and Child commissioned by a secretary of the French king Louis XII. At the insistence of Chaumont, the French governor of Milan, Leonardo returned to the Lombard capital and remained there until 1507, when he was obliged to return to Florence to assert his rights of inheritance under the terms of an uncle’s will. During this time, he painted two Madonnas that he took with him on his return to Milan. Leonardo was still in Milan when Louis XII arrived in that city after his victory at Agnadello. Based on a manuscript sketch, he probably also painted around this time the St John the Baptist now in the Louvre. Not least, he is believed to have painted around this date (and possibly in collaboration with one of his pupils) theVirgin and Child with St Anne, also in the Louvre. His preparatory sketches for the work strongly suggest that his initial intention was to paint an intimate ‘family portrait’, but that he subsequently elected for a composition that became widely acclaimed for the innovative contrapposto technique whereby Leonardo twisted a figure on its own axis, with a movement to the left counterbalanced by an equal and opposite movement to the right. The result is a pleasing dynamic symmetry.

During this period, Leonardo also began designing another equestrian monument, this one to commemorate Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, the governor of Milan under the French. When the Sforza returned to power, the project was abandoned. Leonardo remained in Milan after the withdrawal of the French in 1512 and it has often been speculated that Massimiliano Sforza may have been displeased and bitter at Leonardo’s decision to work there for the French occupiers. Whether that was the case,Leonardo recorded in his journal on 24 September 1513 that he was about to leave for Rome in the company of his pupils Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Francesco Melzi, Lorenzo, and Il Fanoia. In Rome, he was made very welcome by Pope Leo X and duly housed in the Belvedere. Demand for his services proved slight, however, and his output during this period seems inconsiderable. He may have worked there on his Leda and the Swan, together with a Madonna and Child and a Portrait of a Young Boy. There was also a rumour that his preoccupation with scientific studies, notably anatomy, did not endear him to the pontiff.

July 1515 saw Leonardo in the train of the papal army commanded by Giulio de’ Medici, and there are indications that he travelled with the army as far as Piacenza and that he was in Bologna in December 1515 for the signing of the concordat between the pope and Francis I of France. Shortly afterwards, Leonardo’s services as ‘first painter, architect and mechanic of the King’ were retained by Francis I in exchange for a pension amounting to 700 gold crowns and a private residence at Clos-Lucé (Cloux) near Amboise. After settling in Clos-Lucé, Leonardo’s artistic output came to a virtual standstill. He drew up plans for the canal and gardens at the palace of Romorantin and for the construction of a palace near Amboise; he was also credited with having had a major hand in the plans for the Château of Chambord. Much of Leonardo’s time in France seemed to have been devoted to scientific studies and writings in his notebooks.

Leonardo was an avid and highly skilled draughtsman, and the large quantity of his surviving drawings (approximately 4,000 sheets) and notebooks far outweigh his finished paintings and sculptures. These drawings reveal the breadth of Leonardo’s intellect, his innovative mind, and his artistic process. In addition to many technical drawings for machines; anatomical, zoological, and botanical studies; sketches; and figural studies, Leonardo also made architectural drawings of centrally planned churches, many of them contemporary with Donato Bramante’s remodeling of S Maria delle Grazie and Leonardo’s execution of the Last Supper at the same complex. The notebooks also include fragments of a planned treatise on painting, which were compiled by Leonardo’s student Francesco Melzi after his death (Codex Urbinas) and first printed in 1651. Leonardo’s practice of writing backwards has been proposed as either motivated by secrecy or, perhaps more plausibly, a practical solution to the difficulty of writing left-handed.

Leonardo da Vinci’s genius extended across many fields: painting, sculpture, architecture, and various complex scientific research disciplines, including not only anatomy and physics but also highly specialised areas such as military technology and civil engineering. One might have expected that such a technically oriented mind would have been reflected in an artistic style that was precise, not to say meticulous. In effect, quite the contrary is true. Leonardo preferred to render the subtleties and vagaries of light and shade and the mysterious sfumato that is the basis of his style. He strove to create the effect of light not in terms of colour but rather as form so there is no sharp contrast between light and shade but, instead, a long and sustained transition from light towards shade. His figures are bathed in an ‘atmosphere’ that has a presence of its own; they emerge and merge back into the whole without sacrificing the constructive value of their form. In addition to his rendering of spontaneous movement and his ability to capture the serenity of facial expression, Leonardo achieves monumentality by often eliminating detailed settings. Leonardo’s commitment to naturalism in his painting goes hand in hand with his intense scientific study of all aspects of the natural world. Although he is considered the first of the ‘high’ Renaissance artists, in his scientific approach to painting he is quite distinct from his contemporaries, whose naturalism was so often tied to antique precedents.

Group Exhibitions

1979, From Leonardo to Titian: Italian Renaissance Paintings from the Hermitage, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and Knoedler Gallery, New York

2001, Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

2004, Painters of Reality: The Legacy of Leonardo and Caravaggio in Lombardy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Solo Exhibitions

1989, Leonardo da Vinci, Hayward Gallery, London

1989, Leonardo da Vinci: Studies of Drapery, Louvre, Paris

1996–1997, Leonardo’s Codex Leicester: A Masterpiece of Science, American Museum of Natural History, New York

1997, Leonardo da Vinci: Scientist, Inventor, Artist, Institut für Kulturaustausch, Tübingen, Museum of Science, Boston

2000, Leonardo da Vinci: The Codex Leicester, Notebook of a Genius, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

2002, Leonardo da Vinci: Inventor (Léonard de Vinci: l’inventeur), Pierre Gianadda Foundation, Martigny, Switzerland

2003, Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

2003, Leonardo da Vinci: Drawings and Notebooks (Léonard de Vinci. Dessins et Manuscrits) Louvre, Paris

2006, The Treatise on Painting: Manuscripts and Editions between the 16th and 19th Century, Castello Sforzesco, Milan

2006–2007, Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment, and Design, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

2007, The Mind of Leonardo: The Universal Genius at Work, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

2011, Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan, National Gallery, London

Museum and Gallery Holdings

Cambridge (Fitzwilliam Mus.): A Rider on a Rearing Horse (c. 1481, metalpoint reinforced with pen and brown ink/pinkish prepared surface)

Edinburgh (Nat. Gal. of Scotland): Studies of Paws of a Dog or Wolf (c. 1400-1495, silverpoint drawing)

Florence (Gal. dell’Accademia): Vitruvian Man(c. 1487, pen and ink with metalpoint on paper)

Florence (Uffizi): Adoration of the Magi (c. 1480, oil/wood); Annunciation (1470s, oil/wood)

Krakow (Czartoryski Mus.): Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (or Lady with an Ermine)

London (British Library): Arundel Codex

London (NG): Virgin of the Rocks (or Virgin with the Infant Saint John Adoring the Infant Christ Accompanied by an Angel) (c. 1491-1508, oil/wood);Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist (c. 1499-1500, black and white chalk/brownish paper/canvas)

London (Victoria and Albert Mus): Forster Codex

Madrid (Biblioteca Nacional): two codices

Milan (Ambrosiana): Portrait of a Musician (c. 1485, oil/wood); Codex Atlantico

Milan (Biblioteca Trivulziano): Trivulziano Codex

Milan (S Maria delle Grazie): Last Supper

Holy Family

Munich (Alte Pinakothek): Madonna with the Carnation (1470s, oil/wood)

New York (Metropolitan MA): several drawings

Oxford (Christ Church College): seven drawings

Paris (Institut de France): Codices A through M; Ashburnham Codex

Paris (Louvre): La Gioconda (or Mona Lisa);St John the Baptist;Virgin and Child with St Anne; Virgin of the Rocks; La Belle Ferronnière (Lucrezia Crivelli?); Virgin Offering a Bowl of Fruit to the Infant Jesus (drawing); Isabella d’Este(drawing)

Parma (NG): Female Head

St Petersburg (Hermitage): Virgin and Child (Litta Madonna); Benois Madonna

Turin (Royal Library): Study for the Angel for ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’ (drawing)

Vatican (Pinacoteca Vaticana): St Jerome(1480s, tempera and oil/wood); Urbanis Codex

Washington, DC (NGA): Ginevra de’ Benci (c. 1474-1478, oil/panel, two-sided portrait)

Windsor (Windsor Castle, Royal Collection): Study for St James the Elder; notebooks

Auction Records

Paris, 1742: St Jerome, FRF 1,900

London, 1773: Christ and the Virgin with St Joseph, FRF 7,075

London, 1801: Laughing Infant, FRF 34,120

London, 1811: Female Portrait, FRF 78,700

Paris, June 1825: Leda and the Twins Castor and Helen, Pollux and Clytemnestra, FRF 175,000

Paris, 1850: La Colombine (Mistress of Francis I), FRF 81,200; Various Saints: Study for ‘The Last Supper’ (red and black chalk) FRF 16,600

Paris, 1865: Virgin Stooping towards Her Son, FRF 83,500

Paris, 1875: Initial Study for ‘The Adoration of the Magi’ (pen drawing) FRF 12,900; Study for ‘st Anne’ (black chalk, Indian ink, and wash) FRF 13,000

London, 1881: Virgin of the Rocks, FRF 225,000

London, 1888: Virgin in Low Relief, FRF 63,000

Paris, 1900: Draperies (study), FRF 12,500

Paris, 26-27 May 1919: Head of Old Man (silverpoint drawing heightened with white) FRF 6,000

London, 22 May 1925: Infant Jesus and Saint with a Lamb, GBP 1,890

London, 29 June 1926: Hermina: Emblem of Purety (pen) GBP 800; Study Folio (pen) GBP 760

London, 15 July 1927: Virgin with Flowers, GBP 2,100; Head of Leda, GBP 1,785

Paris, 25 Feb 1929: Profile Study of Old Man (pen) FRF 15,400

London, 10-14 July 1936: Wild Horse (pen) GBP 4,305

London, 23 May 1951: Head of the Virgin (charcoal, heightened with colour, study for the painting in the Louvre of The Virgin and St Anne) GBP 8,000

London, 26 March 1963: Head of an Old Man (caricature) (ink drawing with bistre wash) GNS 44,000

London, 21 May 1963: Virgin and Child with a Dog (pen drawing and wash) GBP 19,000

Paris, 12 June 1973: Horse (patinated bronze) FRF 160,000

New York, 17 Nov 1986: Three Child Studies and (recto) Three Lines of Text; Studies: Child, Head of Old Man, and Machine with (verso) Several Lines of Text (black chalk, pen, and brown ink, 8 × 5½ ins/20.3 × 13.8 cm) USD 3,300,000

Monaco, 1 Dec 1989: Draperies with Kneeling Figure Facing Left (brush and brown-grey wash, heightened with white gouache, 11¼ × 7¼ ins/28.8 × 18.1 cm) FRF 35,520,000; Draperies: Study with Figure Standing and Facing Right(brush and brown-grey wash, heightened with white gouache on canvas prepared with grey gouache, 11 × 7¼ ins/28.2 × 18.1 cm) FRF 31,080,000

London, 10 July 2001: Horse and Rider (silverpoint, 5 × 3 ins/12 × 8 cm) GBP 7,400,000

Bibliography

Bode, Wilhem von: Studien über Leonardo da Vinci, G. Grote, Berlin, 1921.

Sirén, Osvald: Leonardo da Vinci, G. Van Oest, Paris, 1928.

Suida, Wilhem: Leonardo und sein Kreis, F. Bruckmann, Munich, 1929.

Verga, Ettore: Bibliografia Vinciana 1493-1930, Zanichelli, Bologna, 1930.

Richter, Jean Paul: The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, Oxford University Press, London and New York, 1939.

Goldschieder, Ludwig: Leonardo da Vinci, Phaidon, London: Oxford University Press, New York, 1943.

Popham, Arthur Ewart: The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, Reynal and Hitchcock, New York, 1945 (2nd ed., Jonathan Cape, London, 1946).

Heydenreich, Heinrich Ludwig: Leonardo da Vinci, 2 vols., Holbein-Verlag, Basel, 1954.

Freud, Sigmund: Leonardo da Vinci: A Memory of His Childhood, Routledge, London, 1957 (reprinted2006).

Chastel, André (ed.)/Callmann, Ellen (trans.): The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci: Leonardo da Vinci on Art and the Artist, Orion Press, New York, 1961.

Huard, Pierre/Grmek, Mirko Dražen: Léonard de Vinci. Dessins scientifiques et techniques, R. Dacosta, Paris, 1962.

Pedretti, Carlo: A Chronology of Leonardo da Vinci’s Architectural Studies after 1500, E. Droz, Geneva,1962.

Gombrich, Ernst Hans: ‘Leonardo’s Methods of Working Out Compositions’, in Norm and Form: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance, Phaidon, London, 1966.

Clark, Kenneth: The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, Phaidon, London, 1968–1969.

Panofsky, Erwin: The Codex Huygens and Leonardo da Vinci’s Art Theory, Greenwood, Westport (CT),1971.

Pedretti, Carlo: Leonardo da Vinci: A Study in Chronology and Style, Thames and Hudson, London, 1973.

Kemp, Martin: Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man, Dent, London, 1981 (2nd rev. ed. 1988).

Calvi, Gerolamo: I Manoscritti di Leonardo da Vinci: dal punto di vista cronologica, storico e biografico,Bramante Editrice, Busto Arsizio, 1982.

Clark, Kenneth/Kemp, Martin: Leonardo da Vinci: An Account of His Development as an Artist,Harmondsworth, Middlesex; Viking, New York, 1988 (new rev. ed.).

Batkin, Leonid M.: Leonardo da Vinci, Laterza, Rome, 1988.

Viatte, Françoisee/Pedretti, Carlo/Chastel, André: Leonardo da Vinci: les études de draperies, exhibition catalogue, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 1989.

Maiorino, Giancarlo: Leonardo da Vinci: The Daedalian Mythmaker, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, 1992.

Turner, Richard: Inventing Leonardo, Alfred A. Kopf, New York, 1993.

Frère, Jean Claude: Léonard de Vinci, Du Terrail, Paris, 1994.

Cole Ahl, Diane (ed.): Leonardo da Vinci’s Sforza Monument Horse: The Art and the Engineering, Lehigh University Press, Bethlehem (PA), Associated University Presses, Cranbury (NJ) and London, 1995.

Letze, Otto/Buchsteiner, Thomas/Guttmann, Nathalie: Leonardo da Vinci: Scientist, Inventor, Artist, exhibition catalogue, Institut für Kulturaustausch, Tübingen; G. Hatje, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1997.

Arasse, Daniel: Leonardo da Vinci: The Rhythm of the World, Konecky and Konecky, New York, 1998(French ed., Hazan, Paris, 1997).

Zöllner, Frank: La ‘Battaglia di Anghiari’ di Leonardo da Vinci fra mitologia e politica, Giunti, Florence,1998.

Zwijnenberg, Ribert: The Writings and Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci: Order and Chaos in Early Modern Thought, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1999.

Chastel, André: Leonardo da Vinci. Studi e ricerche 1952-1990, Phaidon, London, 1999.

Villata, Edoardo/Marani, Pietro C.: Leonardo da Vinci: i documenti e le testimonianze contemporanee,Castallo Sforzesco, Milan, 1999.

Farago, Claire: Leonardo da Vinci: Selected Scholarship, 5 vols, Garland, New York, 1999.

Brown, David Alan: Leonardo da Vinci: Origins of a Genius, Yale University Press, New Haven (CT), 1998.

Desmond, Michael/Pedretti, Carlo: Leonardo da Vinci: The Codex Leicester, Notebook of a Genius, exhibition catalogue, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney; Powerhouse Publishing, Haymarket (Australia),2000.

Nuland, Sherwin: Leonardo da Vinci, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 2000.

Léonard de Vinci: l’inventeur, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny, 2002.

Goffen, Rona: Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian, Yale University Press, New Haven (CT), 2002.

Bambach, Carmen C. (ed.), and others: Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, exhibition catalogue,Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2003.

Zöllner, Frank/Nathan, Johannes: Leonardo da Vinci, 1452–1519: The Complete Paintings and Drawings, catalogue raisonné, Taschen, Cologne and London, 2003.

Kemp, Martin: Leonardo, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004.

Kemp, Martin: Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment and Design, exhibition catalogue, Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ), 2006.

Bernardoni, Andrea: Leonardo e il monumento equestre a Francesco Sforza: Storia di un’opera mai realizzata, Giunti, Florence, 2007.

Farago, Claire (ed.): Re-reading Leonardo: The Treatise on Painting across Europe, 1550–1900, Ashgate, Burlington (VT) and Farnham (England), 2009.

Syson, Luke, and others: Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery, London, 2011.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Leonardo da Vinci from the Benezit Dictionary of Artists appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorld Art Day photography contestMonuments Men and the FrickStreet Photography from Grove Art Online

Related StoriesWorld Art Day photography contestMonuments Men and the FrickStreet Photography from Grove Art Online

April 14, 2014

25 recent jazz albums you really ought to hear

Jazz Appreciation Month gives us an opportunity to celebrate musical milestones of the past. But it also ought to serve as a reminder that jazz is a vibrant art form in the current day. Here are 25 recordings released during the last few months that are well worth hearing.

1. Ambrose Akinmusire – The Imagined Savior Is Far Easier To Paint

1. Ambrose Akinmusire – The Imagined Savior Is Far Easier To Paint

Akinmusire is one of the most talented young trumpeters on the jazz scene. This release also represents a ‘return to its roots’ for the Blue Note label, which has increasingly strayed from mainstream jazz in recent years, but shows here that it hasn’t forgotten its heritage.

2. Greg Amirault – East of the Sun

Many of the most interesting new jazz albums are self-produced or issued by small indie labels. Montreal guitarist Amirault’s new CD is a case in point. He is hardly a household name in the jazz world, but this is one of the best guitar albums released in recent months.

3. The Bad Plus – The Rite of Spring

Stravinsky has been inspiring jazz artists for decades, but this ranks among the most creative reinterpretations of his work that I’ve heard.

4. Jeff Ballard – Time’s Tales

Check out the funky 9/4 groove that opens this leader date for drummer Jeff Ballard—joined byguitarist Lionel Loueke and saxophonist Miguel Zenon.

5. Joe Beck – Get Me

5. Joe Beck – Get Me

Guitarist Joe Beck died in 2008, but this posthumous release (coming out in a few days) is likely to reignite interest in a very talented and underrated artist.

6. George Cables – Icons and Influences

I’ve been a fan of Cables’ piano work since I was a teenager. He has been in poor health in recent years, but this new albums finds him playing at top form.

7. Regina Carter – Southern Comfort

Carter combines jazz with traditional Southern music on her latest release. Even listeners who don’t think they like jazz might find themselves enjoying this appealing album.

8. Matt Criscuolo – Blippity Blat

This is another self-produced album that merits close listening. Criscuolo is formidable saxophonist with a sweet tone and supple phrasing.

9. Karl Denson’s Tiny Universe – New Ammo

9. Karl Denson’s Tiny Universe – New Ammo

With this high-octane funk-oriented release, Denson proves that jazz can still work as dance music. This album might make a good entry point into jazz for rock fans who want to broaden their tastes and expand their ears.

10. Nir Felder – Golden Age

The recently revived OKeh label is releasing a number of outstanding jazz albums, but this CD from up-and-coming guitarist Nir Felder may be its most ambitious project of 2014, pushing beyond conventional boundaries of jazz and popular music.

11. Craig Handy – Craig Handy & 2nd Line Smith

Handy mixes elements of New Orleans party music and Hammond organ soul jazz in a very exciting hybrid. In a fair and hip world, this album (and the Denson release mentioned above) would be generating lots of radio airplay.

12. Vijay Iyer – Mutations

Iyer’s debut album with the ECM label is one of his best to date, revealing his maturity not just as a jazz player but also as a composer of jazz-oriented chamber music.

13. Christian Jacob – Beautiful Jazz

13. Christian Jacob – Beautiful Jazz

Here’s another smart self-produced jazz album that you could easily miss. Pianist Jacob is a master at updating and reharmonizing the traditional jazz repertoire.

14. Erik Jekabson – Live at the Hillside Club

Jekabson is one of the most promising young trumpeters on the West Coast, and continues to impress with this new album.

15. John Lurie – The Invention of Animals

John Lurie has never gotten the respect he deserves for his jazz work with the Lounge Lizards. He subsequently abandoned music to focus on painting, but these rediscovered tracks testify to his brilliance as a jazz improviser.

16. Pete McGuinness Jazz Orchestra – Strength in Numbers

I have heard several outstanding jazz big band albums this year, but this one is the best of breed.

17. The North – Slow Down (This Isn’t the Mainland)

17. The North – Slow Down (This Isn’t the Mainland)

Fans of mid-period Keith Jarrett and E.S.T. will enjoy this trio album. This band is still a well-kept secret in the jazz world, but their music has clear crossover potential.

18. Danilo Pérez – Panama 500

Pérez has long ranked among the leading Latin jazz artists. Here he draws on the Panamanian music tradition for a theme album commemorating the 500th anniversary of Balboa crossing the Isthmus of Panama.

19. Matthew Shipp – Root of Things

Pianist Shipp possesses an expansive vision of jazz that, over the years, has encompassed everything from hip-hop to electronica. In his latest album, he returns to the acoustic trio format, where he is joined by bassist Michael Bisio and drummer Whit Dickey.

20. Revolutionary Snake Ensemble – Live Snakes