Oxford University Press's Blog, page 338

August 7, 2017

What Norway might tell us about Venezuela’s economic crisis

It is common to blame Venezuela’s current crisis on the price of oil. Despite sitting atop the world’s largest proven oil reserves, the Venezuelan economy is in a shambles and the country is gripped by chaos. When the price of oil fell precipitously in 2014, so too did Venezuela’s access to foreign exchange. Without this money, Venezuela has been unable to buoy the country’s national oil company and the social programs and food subsidies that support the sitting government.

While oil plays an important part in Venezuela’s tragedy, and most agree that President Nicolás Maduro’s policies have exacerbated the situation, much of the world’s critical attention is misplaced. The roots of Venezuela’s problems run much deeper than the current administration. The experience of another petroleum-rich state, Norway, suggests that Venezuela’s problems are not so much oil, a national oil company, or social support policies; Venezuela suffers from poor management practices, and this cursed mismanagement is long-standing.

Beware of volatile prices

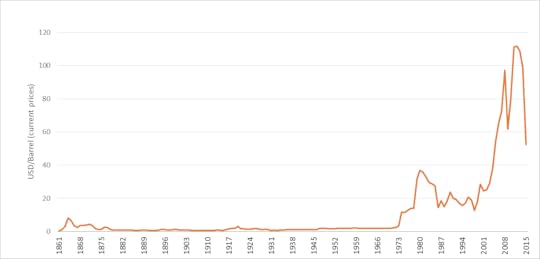

While the recent fall in oil prices was dramatic, it was not unprecedented. Like other natural resources, the price of oil is cyclical in nature: periods of rising prices are frequently followed by periods of falling prices, as illustrated in Figure 1. Consumers have experienced significant oil price shocks before (e.g. in the 1980s and around 2008), and will do so again in the future. Prudent management of a petroleum economy requires policymakers to prepare for the next change in prices.

Figure 1. The Price of oil from 1861-2015. Data from BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2016.

Figure 1. The Price of oil from 1861-2015. Data from BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2016.For countries that rely heavily on petroleum production, a radical price drop threatens a reduction in economic growth, an expanding government budget and national trade deficits, and an increase in the risks of financial and macroeconomic instability. To protect against these threats, policymakers must ensure that the domestic economy is not overly dependent on that resource, and build up financial reserves that can be marshalled when prices drop. In short, a robust economy needs more than one leg to stand. There are several ways to do this but each requires the capacity for strategic long-term planning. The Resource Curse stands as proof of the difficulty many states have in achieving these strategic objectives.

Norwegian Experience

Recently, Bjørn Letnes and I examined Norway’s response to the recent oil price shock. Our intent was to demonstrate that oil need not always be a curse and that states can avoid the Paradox of Plenty. Norway wielded a variety of tools in response to the new price environment, and many of these tools are not immediately available to other countries (e.g. a flexible exchange rate and a corporatist wage bargaining framework). But the foundation upon which these policies rest is available to all petroleum-producing states and consists of two main components: a) the need to maintain viable economic (export) alternatives to petroleum and b) the capacity to secure responsible fiscal policies that anticipate the volatility of petroleum prices.

Key to the Norwegian response was a dramatic fall in the value of the Norwegian krone (which shadowed the fall in global oil prices). This had an immediate effect on the Norwegian export sector, whose prices suddenly became more competitive on international markets. Idle factors (capital and labor) from the petroleum sector flowed into these growing export markets. While moving jobs and investments takes time, and some local markets were harder hit than others, a depreciation of the krone provided existing exporters with the sort of kick-start needed to turn over the Norwegian economy. It is important to emphasize that a non-oil export sector has been nurtured from the very start of Norway’s oil adventure and hence was ready to pounce when the exchange rate improved. This is the core economic challenge of resource dependence, as the most valuable export sectors in a country tend to be hurt by the currency appreciation accompanying oil wealth (when times are better).

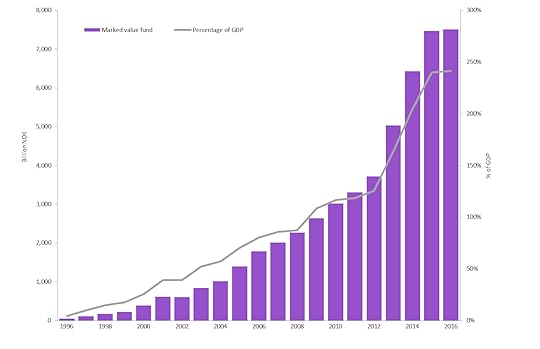

Figure 2. Data from Norwegian Petroleum (2017).

Figure 2. Data from Norwegian Petroleum (2017).At the same time, Norway has amassed a fortune in the world’s largest sovereign investment fund: its Government Pension Fund, Global (GPFG). More importantly, Norwegian politicians have agreed to a rule that isolates the government’s budget from the volatility of oil prices and limits the amount of oil money filling the government’s coffers (to inoculate against Dutch Disease). Hence, when oil revenues dry up, the government can turn to the GPFG to keep funding its ambitious social policies and to encourage developments in the mainland (non-oil) economy.

In light of Norway’s response, we might think again about the nature of the economic crisis in Venezuela. Venezuela’s problem should not be linked to the existence of a national oil company, extensive social programs, or even food subsidies; after all, Norway enjoys all these economic artifacts, and successfully avoids the Resource Curse. Venezuela’s current problems can be traced back to its over-reliance on oil and short-sighted fiscal policies—and these problems can be traced farther back in Venezuela’s history. In particular, Venezuela lacks an (alternative) export strategy and the savings (and economic breathing room) it needs to respond to the crisis. This is not to excuse Maduro for his misplaced policies, as many believe they have worsened the situation. Rather, it is a call for better long-term management strategies for the future, and a recognition that these can be done in a socially-responsible manner.

Featured image credit: Oil Rig by Catmoz. CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post What Norway might tell us about Venezuela’s economic crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Unsilencing the library

“Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.” So wrote Virginia Woolf in her famous 1929 essay on reading and freedom, A Room of One’s Own. Earlier this year, a team of academics at Oxford University were invited through the locked gates of HMP Bullingdon, to attend one of the reading groups facilitated by the charity, Prison Reading Groups, held in the prison’s small library.

The visit formed part of our project, Unsilencing the Library: an exploration of how reading has mattered to people at different moments in their lives, and at different points in time. It began some miles away, in a Warwickshire art gallery and museum. Compton Verney, the former seat of the Verney family, was virtually a ruin by 1993. One room, however, retained its historic fittings, and a key decorative feature remained intact—a set of imitation books framing the room’s doorway.

This feature is remarkable not just for its survival, but for the story it tells us today. It was probably commissioned by Georgiana Verney, wife of the 17th Lord Willoughby de Broke, in around 1860. An accidental aristocrat, Georgiana never expected to be a Baroness. After her husband, Robert, died in 1862, she spent her remaining years founding schools, campaigning for the temperance movement, and promoting literacy in the community. She was also involved in the fight for women’s rights. Curiously; uniquely, the imitation books she commissioned are testament to this—for all of the authors on the book spines are women. And so, Georgiana’s visionary doorway continues to send out a very real message about equality of mind.

I learnt myself 2 read and write—this was my first book that I understood

Funding from Oxford University allowed us to research the history behind the imitation bookshelves, and support from UK publishers allowed us to curate and fill the rest of the empty shelves in the room. Inspired by Georgiana’s ‘shelfie,’ we set out to ask different people, and organisations, to suggest what to put on them. Actress and campaigner Emma Watson, broadcaster and gardener Alys Fowler, and writer Margo Jefferson all sent us lists of their favourite books. So did teenagers from a Warwickshire comprehensive, Kineton High School. And so did dozens of members of Prison Reading Groups.

Readers in prisons nationwide have shared some extraordinary choices, from tales of shipwrecks and smuggling to transformational self-help books, comic novels and cartoons. When we collated the nominations, we were struck by the popularity of one particular book: Alexander Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, which was nominated by a number of individual members of Prison Reading Groups. Serialised between 1844 and 1846, Dumas’s tale of wrongful imprisonment, courage, revenge and redemption has always been one of those books which seems capture readers. Like Sherlock Holmes, or Mr Pickwick, the Count is one of those characters who take a place in what W. H. Auden called our ‘mythopoeic imagination.’ It’s as if such characters have a life beyond the book—a virtual reality of their own. Prison librarians confirm that Dumas is among the most borrowed books in UK prisons. For former prisoner, Kerri Bloginder there’s ‘no explanation needed’ as to why this might be so. But the explanations that lie behind our reading choices have their own kind of interest. In nominating Dumas, our contributors at Thameside and Wandsworth wrote as follows:

“I learnt myself 2 read and write—this was my first book that I understood—since then I’ve liked to read period books, especially Tudor and Regency times.”

“For: the romance that was lost, the heart that was broken, the friendship that was betrayed and the endless courage and passion for life, truth, loyalty and love! That’s why! One of the greatest classics!!”

One of the greatest classics!!

“I am learn for to be a good man.”

Alexander Dumas now sits on the library shelf at Compton Verney, alongside the other choices by men and women in HMP Send, HMP Wormwood Scrubs and HMP Wandsworth. The English translation of Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal is found to its right, and The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy to its left. On the shelf below, Adam, at HMP Grendon, has chosen Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, for its “provocative transgressiveness.” Woolf, he writes, offers us an “enlightened attitude to gender and sexuality decades ahead of its time. The attempts to capture the fleeting experience of the moment are so beautiful and ambitious. A quality read.”

We like to think that Georgiana would have approved.

You can visit the restored room and exhibition at Compton Verney Art Gallery and Museum from this June, and browse it on the supporting website.

Featured image credit: “Books” by AhmadArdity. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Unsilencing the library appeared first on OUPblog.

Louis Leakey’s quest to discover human origins

Louis Leakey remains one of the most recognized names in paleoanthropology and of twentieth century science. Leakey was a prolific writer, a popular lecturer, and a skillful organizer who did a great deal to bring the latest discoveries about human evolution to a broader public and whose legacy continues to shape research into the origins of mankind. Many people have found important fossils relating to human evolution, yet Louis and Mary Leakey’s excavations at Olduvai Gorge have attained an iconic status in the public imagination. It is worth exploring some of the reasons why. Louis was born in Kenya, the son of British missionaries. Some of the mystique surrounding his life stems from his vivid descriptions of growing up with Kikuyu friends surrounded by the spectacular wildlife of the area. Louis lived through the turbulent years of the Mau Mau rebellion against British colonial rule in Kenya (he served as a translator during the trial of Jomo Kenyata) and Kenyan independence in 1963. He is best known for the discoveries at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, but a significant aspect of that research was the important collaboration that Louis had with his wife Mary, who had trained as an archaeologist before their marriage.

Louis and Mary’s work garnered wide public attention for several reasons. The idea of human evolution had become an increasingly exciting and contentious subject during the early twentieth century as newspapers covered the discovery of Peking Man in China, Australopithecus in South Africa, and Neanderthals in Europe. But the rise of creationism and events such as the Scopes Trial, which sprang from the Tennessee law banning the teaching of evolution in public schools, elevated the public interest in human evolution and its implications for how we see ourselves.

When Louis discovered crude stone tools (called Oldowan tools) at Olduvai in the 1930s they were the oldest artifacts that had ever been found. In 1959 Louis and Mary made the exciting announcement that they had discovered the skull of a creature that walked upright and had a mixture of human and apelike features. With a good deal of media fanfare Louis presented the fossil to the world, and while giving it the formal zoological name of Zinjanthropus boisei, he also deftly gave it the nickname of Nutcracker Man because of the specimen’s massive jaw and teeth. Scientists and the public greeted the fossil enthusiastically but there were more surprises ahead. Determining the age of fossils had always involved considerable uncertainty, but a team of scientists from the University of California at Berkeley had recently developed a technique called the potassium/argon dating method that could date volcanic rocks. Louis arranged to have rocks from Olduvai dated by this method with the amazing result that Zinjanthropus had lived 1.75 million years ago. The use of this dating method soon became standard practice and has since been used to give dates for many fossils found in Africa and elsewhere.

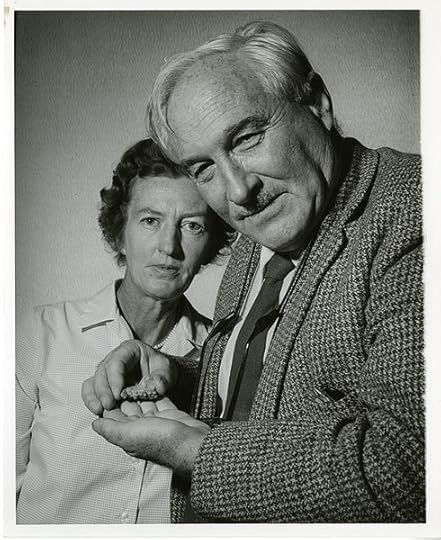

British archeologist and anthropologist Mary Douglas Nicol Leakey (1913-1996) and her husband Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (1903-1972), 1962 by Smithsonian Institution Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British archeologist and anthropologist Mary Douglas Nicol Leakey (1913-1996) and her husband Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (1903-1972), 1962 by Smithsonian Institution Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Louis went on to unearth new fossils during the 1960s from a more humanlike creature that was eventually named Homo habilis (Handy Man), but paleoanthropologists continued to debate the classification of these fossils and the very nature of this species. When Louis began his work most anthropologists thought humans had evolved in Asia, but his discoveries played an important role in shifting attention to Africa as the cradle of human evolution.

Funding paleontological excavations was always a challenge and Louis skillfully used the public attention generated by his discoveries to establish a relationship with the National Geographic Society. The Society agreed to fund the Leakeys’ research and in exchange National Geographic magazine published dramatic accounts of the Leakeys’ new discoveries. The Society even produced a documentary in 1966 titled Dr Leakey and the Dawn of Man. This was a major innovation and opened the way for numerous articles and documentary films produced by the Society over the last fifty years that have been an important way of introducing people to the significant advances being made in human origins research.

Louis also believed that in order to reconstruct the behavior of our early apelike ancestors we needed to know more about the habits and behavior of modern apes. Unable to pursue this research himself, Louis was instrumental in laying the groundwork in the 1960s for Jane Goodall’s momentous research of chimpanzees living in the Gombe National Reserve, as well as Dian Fossey’s studies of mountain gorillas in Rwanda and Biruté Galdikas’ investigation of orangutans in Borneo. These groundbreaking studies of apes in the wild fundamentally changed the course of primate research.

Louis has also left a legacy of influential institutions that continue to promote and fund research relating to human evolution. In an effort to encourage research and to bring together scientists from different disciplines relating to human origins research, Louis created the Pan-African Congress on Prehistory. The first of these meetings was held in Nairobi in 1947, and the Congresses have continued to meet at irregular intervals ever since. Louis also served as curator of the Coryndon Museum, in Nairobi, which after Kenyan independence was incorporated into the newly created National Museums of Kenya. Under the leadership of Louis, and later of his son Richard, the Museum has remained a leading center of human evolution research. Today the Leakey Foundation, headquartered in San Francisco, California, as well as the International Louis Leakey Memorial Institute for African Prehistory, located in Nairobi, Kenya, continue the important research of Louis and Mary Leakey and stand as a testament to their accomplishments.

Featured image credit: “Mary Douglas Nicol Leakey (1913-1996) and her husband Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (1903-1972)”, from the National Geographic Society. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Louis Leakey’s quest to discover human origins appeared first on OUPblog.

Historical narratives and international tribunals

Collective memories are significant for individuals and societies, and they play an important role in the formation of collective identities. This post focuses on the role of non-criminal international tribunals in the development of collective memories: is it desirable for such tribunals to be involved in the construction of collective memories? International tribunals have not adopted a consistent approach concerning the presentation of the historical narrative in the background of the judgment. In some cases, for example, international tribunals presented a detailed account of the historical background, while in others they provided only a very brief account of the historical event, and sometimes made no mention of it at all.

International tribunals’ involvement in the development of collective memories may take several forms (such as keeping historical evidence in tribunals’ archives or ordering a party to commemorate a particular event) but this post focuses on the question concerning these tribunals’ role in presenting historical narratives in their judgments. Such judicial-historical pronouncements are often of profound importance for the litigating parties, frequently more important than the final legal ruling or pecuniary compensations. Often the answer provided to the question regarding the desirable role of non-criminal tribunals in this sphere is not dichotomous. In certain cases, tribunals are bound to establish some historical facts in order to resolve a particular legal dispute. But even in such cases, tribunals have significant discretion and they may, for example, adopt either an expansive approach (and elaborate on the particular historical narrative), or a restrictive approach (and succinctly present the most essential facts needed to resolve the legal question).

“International Criminal Court building in The Hague (2016)” by OSeveno. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“International Criminal Court building in The Hague (2016)” by OSeveno. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The desirable role of non-criminal tribunals in this field has been analysed from three major sociological perspectives: the structural-functional approach, the symbolic-interactionist perspective, and the social conflict approach. Each sociological approach offers a different conception of collective memories, emphasizes different audiences, and differently conceives the role of tribunals in the international society. The following conclusions integrate certain elements from each sociological approach but primarily draw on recommendations associated with the symbolic-interactionist perspective and, to a lesser extent, on some recommendations associated with the social-conflict approach. These conclusions emphasize that international adjudicators are embedded in socio-historical environments and are influenced (whether or not they present an historical narrative) by historical narratives prevailing within their respective groups. The interactionist character of the field suggests that researchers should broaden their investigatory lenses, and take into account that if tribunals do not assume an active role in this sphere, other agents of memory (such as governmental bodies, the mass media or historians) are likely to construct historical narratives without the involvement of international tribunals.

The International Criminal Court in The Hague (ICC/CPI), Netherlands by Loranchet. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The International Criminal Court in The Hague (ICC/CPI), Netherlands by Loranchet. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.International tribunals interact with additional agents of memory, and though they are more constrained than are other agents of memory (for example, regarding evident-iary rules or the elements of legal concepts), they have some significant advantages in this sphere (for example, they are often less biased and more transparent than other agents of memory). Each agent of memory possesses some advantages and limits and they often cross-fertilize—and constrain—each other. In certain circumstances, the role of non-criminal tribunals in this field is particularly vital, such as when domestic bodies deliberately conceal or ignore a significant historical event which has generated extensive harm to a disadvantaged group. In such cases, it is desirable that international tribunals (while acknowledging possible bias of each actor) undertake an inclusive approach and make reasonable efforts to take into account historical findings produced by other agents of memory (such as historians and experts). Following the symbolic-interactionist approach, judicial-historical narratives are significant primarily as a meaningful remedy for individuals and smaller communities whose rights have been violated. In light of the valuable socio-cultural qualities of local institutions in this sphere, it is generally legitimate for regional tribunals like the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (rather than global ones) to assume an active role in developing the regional historical heritage.

Few truly global historical narratives are likely to emerge from the extremely diversified global society, and such wide-scale memories should emerge from bottom-up interactions between national and regional bodies (rather than externally imposed by global tribunals). The benefits of constructing collective memories in a bottom-up process indicate that where national tribunals (or local quasi-judicial bodies) function effectively and reliably, international tribunals (either global or regional) should refrain from interfering in the development of local historical narratives. Where international tribunals encounter considerably asymmetric settings (e.g., powerful government v. indigenous group), it is desirable that they apply adequate rules of evidence to somewhat mitigate the parties’ unbalanced capacities in proving historical events.

Featured image credit: “Earth, Lights” by Free-Photos. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Historical narratives and international tribunals appeared first on OUPblog.

August 6, 2017

A very British realignment

Over the first two years of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party, several commentators noted fascinating parallels with an iconic fictional account of a Labour leadership. First written as a novel by journalist and future Labour MP Chris Mullin in 1982, A Very British Coup depicts the surprise election of a radical left-wing Labour Party led by staunch socialist Harry Perkins in an imagined near future. As the story unfolds, Perkins struggles against a conspiracy to engineer his downfall by vehement opponents of his agenda, including figures from intelligence agencies, the media, the civil service, and the US government. Six years later a television adaptation brought the story to a larger audience, cementing its place as a cultural touchstone of the 1980s.

Many of the controversies surrounding Corbyn’s leadership eerily resembled aspects of Mullin’s story. This included a warning from an anonymous general of a potential “mutiny” in the army, allegations of “dark practices” conducted against Corbyn by MI5, and the declaration by a former head of MI6 that a Corbyn victory in the 2017 election would be “profoundly dangerous for the nation”. The novel’s satirical depiction of Perkins’ press coverage particularly foreshadowed that which greeted Corbyn. In Mullin’s vision, the right-wing press responds to Perkins’ initial party leadership by gloating “Labour votes for suicide”. Yet in case readers are tempted to believe otherwise, they provide tenuous allegations of Trotskyite infiltration and support for terrorists, hyperbolic comparisons with the Third Reich, and apocalyptic forecasts of chaos and violence in the event of a Labour election victory.

Chris Mullin MP in 2009. Photo by Maggie Hannan. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Chris Mullin MP in 2009. Photo by Maggie Hannan. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Throughout these first two years, however, it was difficult to imagine Corbyn going as far as Perkins to become Prime Minister, with poor poll ratings, an inability to unite the party around his agenda, and widespread perceptions of him as a weak leader. Even Mullin, having served 23 years as MP for Sunderland South (1987-2010), had little faith in his imagined scenario becoming reality. Whilst consistently describing Corbyn as “a thoroughly decent man, who has lived all his life according to his principles”, he warned that selecting a leader with little backing from the Parliamentary Labour Party was a “high risk strategy”. Initially he argued that “Corbyn should be given a chance”, but in the aftermath of the EU referendum he added his voice to a chorus demanding that “Corbyn must go”, writing that “it was an interesting experiment, but it was always destined to end badly.”

Indeed, despite exploring the means through which the Establishment works to topple Perkins in some detail, Mullin’s book is much vaguer on how his fictional Labour leader surmounted those forces to become Prime Minister in the first place. The fascination of its high-concept ‘what if?’ premise is arguably rooted in the very unlikeliness of the scenario in the 1980s rather than it being a plausibly projected future. The novel attempts some explanation; anticipating the dominance of free-market Conservatism through the 1980s, it shows the radical Labour government obtaining power following severe economic collapse at the end of the decade, yet even so offers little sense of how fierce press opposition was overcome. Concurrently in the real-world, an orthodoxy was developing that Labour could no longer win an election without conciliatory appeals to the right-wing press, and later Tony Blair’s three election victories were widely attributed in part to his willingness to court the Murdoch empire.

Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Leader, speaking at a political rally during the Labour leadership election, in Matlock, Derbyshire, 16th August 2016. Photo by Sophie J. Brown. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Leader, speaking at a political rally during the Labour leadership election, in Matlock, Derbyshire, 16th August 2016. Photo by Sophie J. Brown. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In the 2017 election, however, Corbyn achieved an unexpected triumph (if not full victory), leading Labour from a 20-point lag in the polls to full resurgence, destroying the Conservative Party’s majority and defying widespread belief that his leadership could only conceivably lead to ruinous defeat. A more dynamic campaigner than anticipated, Corbyn benefitted from broadcasters’ obligation to give major parties equal coverage in an election period, gaining more opportunity to put his case forward whilst cutting through his systematic misrepresentation in the press (as found by numerous studies). This echoes the climax of the televised A Very British Coup, in which Perkins audaciously uses a Prime Ministerial broadcast to expose the forces subjecting him to blackmail.

Yet other features of the Corbyn campaign were not anticipated in Mullin’s story. Overall A Very British Coup presents “the people” (credited as such in the adaptation) in a largely passive capacity, their role amounting to little more than contributing to opinion polls, casting votes and sitting fearfully in front of television screens as various crises unfold. Despite Perkins’ own background as a campaigner, the story gives little sense of a continuing role for political activism or the presence of a broader social movement. By contrast, Corbyn was propelled to the Labour leadership and sustained through difficult times by a groundswell of activism. In the election campaign, this movement developed to spread Corbyn’s political ideas through alternative means of public engagement ranging from the premodern (rallies) to the postmodern (social media).

Heard from very good source who was there that Rupert Murdoch stormed out of The Times Election Party after seeing the Exit Poll

Building a consensus on climate change

As the world shudders in the face of the Trump Administration rejection of the Paris Climate Accords, other forms of expertise and professional engagement are, again, taking on increased relevance. Buildings have long been important mediators in the relationship between energy, politics, and culture. Today, in the face of policies of retreat, the architecture, engineering, and construction professions are increasingly compelled to take on energy efficiency, and the burden and opportunity of managing carbon emissions.

On the one hand, this is a very challenging prospect—a recent report from the World Green Building Council concludes that, in order to maintain the Paris-mandated target of holding to a 2° Celsius global temperature increase, every building in the world needs to be carbon-neutral by 2050. A daunting task, to be sure, and one that far exceeds, in its policy and social implications, the purview of architectural designers.

On the other hand, there is a long history of architectural innovations that bring together concerns over energy efficiency, government policy, and new cultural opportunities. In the years just after World War II, policy makers, scientists, and architects were interested in understanding the role of energy in the more intensely globalized economic and political world. One of the first projects of UNESCO was the convening of the 1949 UN Scientific Conference on the Conservation and Utilization of Resources (UNCCUR) in Lake Success, New York, a three-week conference that looked at a range of materials and technologies. Solar energy was already playing an important, if largely symbolic role: then-Secretary of the Interior Julius Krug opened the conference, as the New York Times reported, by insisting that solar energy should be “high on the list of possibilities that might have a tremendous bearing on the resources of the country.” This was just one of many episodes and discussions that cultivated a culture of interest in alternative energy technologies—a 1953 article in Fortune decried the “strange socio-industrial lethargy” that prevented more focused research on alternative technologies.

solar panel array roof building by skeeze. Public domain via Pixabay.

solar panel array roof building by skeeze. Public domain via Pixabay.Buildings and architects were at the center of these debates. A number of architects presented solar houses at UNSCCUR, including Maria Telkes’ innovative system of using chemical compounds for solar heat storage (now known as Phase-Change Materials); the Fortune article also included a solar ranch house that grew algae as a food source on its roof. Architecture—especially the design of houses—was seen as one of the most immediately applicable ways of taking advantage of energy from the sun: because of the synergy between solar design strategies and the received tenets of architectural modernism; the expansion into the open lots of the suburbs allowed for optimal solar orientation; and because new styles in architecture were seen to be symbolic of the “good life”—a brighter, more liberated social and economic future.

These histories suggest that cultural innovations can project us towards a workable future, even what that future is not yet attainable technologically. The difference today is that we have the technology we need but lack, to some extent, the cultural desire and, at least at the federal level, the cultural will.

This is not to say that we should expect too much from architects—if anything, the political rise of the developer class further challenges the ethical and political commitments of the field. Architects tend to follow the trajectories of capital. But the profession can aspire to (and citizens can encourage) offer new ideas about the built environment, its form and its systems, that bring us closer to a carbon-neutral future. And of course, after Trump’s withdrawal, there has been a surge of cities, states, and corporations anxious to renew and increase their own commitments to collaborative solutions for climate change mitigation. If there are lots of trajectories for architects to follow, there is also an opportunity for architects to lead – to insist on zero-carbon buildings even without policy incentives or regulatory support.

Or even better, to use the dynamic aesthetic and material skills of the field to imagine and build a post-carbon future. Many architects and many architecture schools are still caught up in debates about form-making, a sort of long postmodern hangover, rather than focused on new spatial and technological conditions of a climate threatened future. Perhaps this latest threat to global climate stability, and the dramatic economic and social changes it implies, will bring to light the cultural opportunity now available amongst designers and their potential clients. An opportunity to direct architectural thinking more resolutely towards facilitating a culture of environmental transformation, towards building a consensus around the necessity of directly addressing climate change.

Headline image credit: skyline by Adam Detrick. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr .

The post Building a consensus on climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

Secrets of the comma

When it comes to punctuation, I’m a lumper rather than a splitter. Some nights I lie awake, pondering to secrets of commas, dashes, parentheses, and more, looking for grand patterns.

“Is something bothering you?” my wife asks.

“Yes,” I reply. “Commas.”

Style guides give a baker’s dozen of comma rules, which seem like a lot to remember. Some writers even distinguish commas by name: adverbial commas, appositive commas, clausal commas, phrasal commas, quotational commas, salutational commas, vocative commas, conjunctional commas, elliptical commas, list commas, and Oxford commas. Whew.

Others adhere to the “put a comma anywhere you’d pause” idea. The pause approach really doesn’t work (especially if you are prone to dramatic speech). Commas may have once been used to indicate pauses, but today they are keyed to the grammar of sentences.

In my most optimistic moments, I like to think that comma use can be organized according to just two broad themes.

Commas combine. Commas coordinate lists of three or more things in a series, with the last joined by and or a similar conjunction: eggs, cheese, milk, and coffee. They also coordinate sentences when they are joined by a conjunction like for, and, nor, boy, or, yet or so (the famous FANBOYS). They can coordinate a pair of adjectives that could be joined by the word and (the long, boring lecture). They can even signal a coordination of a sentence with a fragment (Everyone loves commas, don’t they? Children love the birthday parties, adults not so much.) If you use a shoehorn and a bit of imagination you can even see commas as combining quoted material with quote tags (Sheila said, “Watch for that car!”)

Commas separate material from a main clause. Within a clause commas set off insertions of material which fall outside of the core subject and predicate. Within a sentence you find commas around parentheticals (like I believe or so it would seem), non-restrictive relative clauses (like Ted, whom I admire very much, is speaking at noon.) and appositives (The avocado, a creamy green fruit, is great in a salad). Commas are also used when an adverb like however or nevertheless, intervenes between the subject and predicate. Such words comment on the clause as a whole rather than on the predicate, so they are set apart.

We can extend the idea to the commas that separate phrases, clauses, names, and interjections at the front of a clause. Such elements are also grammatically or semantically outside of the clause that follows them:

In a few days, someone will be by to fix the problem.

Because I’m obsessed with grammar, I worry about commas.

Alice, I really enjoyed your book.

Well, that’s a surprise.

When adverbs and adverbial clauses and phrases come after the predicate, they often lack commas because they are understood as part of the predicate—as closely connected to the verb. But when a semantic or grammatical contrast is intended, commas are used to signal the distance from the main clause. So we are likely to find a contrast like this:

I worry about commas because I’m obsessed with grammar.

I worry about commas, although I never seem to fully understand them.

In the first, the reason is connected to the worrying; in the second whole clauses are being contrasted. The distinction between connection to the predicate and disconnection can help us to make sense of contrasts like these as well:

I like French food too. (French food as well as Italian food)

I like French food, too. (I as well as other people)

I smelled the roses as I was taking a walk. (while walking)

I smelled the roses, as it had been a hard day. (on account of)

That’s the idea. Commas combine and commas separate. Now maybe I can get some sleep.

Featured image: “Roses” by slgckgc. CC by 2.0 via Flickr .

The post Secrets of the comma appeared first on OUPblog.

Which Celtic goddess are you?

Although most people have heard of the Celts, very little is known about their customs and beliefs. Unlike the Ancient Greeks and Romans, few records of their stories exist. However, the surviving stories have played an important role in literary history—influencing writers like J.R.R. Tolkein and C.S. Lewis.

New to Celtic mythology? Jump in by taking the quiz below to find out which Celtic goddess you are.

Featured image credit: “Epona Salonica601” provided by QuartierLatin1968 CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Which Celtic goddess are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

August 5, 2017

Valuing our ecological futures

Most people care about their potential futures. But there’s a threat to some of these possible futures. In 2016, globally we experienced the hottest consecutive year on record since 2000, with 2017 looking to break the record again. At the current rate of warming climates, along with other environmental concerns, living on the Earth will become more difficult, if not impossible, by the end of the century. Scientists have predicted humans only have 60 more harvests, or years of growing enough food to sustain people on the planet, if soil continues to erode. It’s undeniable that climate change remains one of the greatest hazards to human and nonhuman existence. But it’s only one of the many effects of ecological degradation – with others including deforestation, ocean acidification, species extinction, and air pollution – over the past 250 years during the age of industrialization. This period is increasingly referred to as the Anthropocene – or the age of humans.

The question remains: how do we alter this seemingly apocalyptic direction forward? Perhaps it’s more productive to ask: how can we imagine and create sustainable ecological futures? As the cognitive linguist and political strategist George Lakoff maintains, change comes from reframing the debate from one of reason and logic to one based upon values. How, then, might we influence the values of societies to prioritize sustainable ways of living? How would climate deniers overcome entrenched belief systems to accept the necessity of taking climate action? More specifically to this blog post, how can literary culture – which builds upon human values and perception – help imagine those futures, and be part of this change?

Literary culture and critical theories have a long history of responding to political and social issues. Ecocriticism emerged in the 1970s as a reaction to the larger environmental crisis. It originated as an idea called “literary ecology” by Joseph Meeker in 1972, and was later labelled “ecocriticism” by William Rueckert in 1978. The aim was to establish a critical way of examining ecological issues connected to representations of them in literature and culture.

By the early 1990s, ecocriticism had developed as a popular literary and cultural theory with the formation of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) at the Western Literary Association in 1992, followed by the launch in 1993 of the flagship journal ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment and the edited volume The Ecocriticism Reader in 1996. Ecocriticism has since become one of the most widely recognized and applied literary and critical theories, largely because of the existential environmental crises increasing by the day that it seeks to examine and confront.

Engraving by Gustave Doré from 1876 edition of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Sourced from University of Adelaide. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Engraving by Gustave Doré from 1876 edition of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Sourced from University of Adelaide. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Much like other socially relevant literary and critical approaches, such as postcolonial, gender, or Marxist studies, ecocriticism continues to grow and be shaped by current events. It unfolds in the present as much as it can be applied historically in scope and scale. For example, the understanding of the nonhuman (i.e., albatross, weather, and the ocean) in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s long poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) is as important as the links among patriarchy, class, and ecology in Margaret Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) and the contemporary television series adapted to it. At its core, the focus of ecocriticism has remained consistent: to recognize and confront ecological concerns through literature and culture.

Over the last decade, environmental thinking has expanded vastly, paralleling the social and biophysical ruptures across the Earth. In response to these rapid changes, ecocritics have developed new ways of understanding and responding to literature and culture that draw on both imaginative and real circumstances of the Earth’s ecologies. Reframing how we think about the environment or “nature” is not a simple process; new systems of thought, definition, and practice must be established in order to change how people value them. Dismantling anthropocentric (human-centered) ways of viewing and being in the world is a fundamental part of this shift. Biocentric (Earth-centered) ways of viewing the world, for instance, consider humans as a part of the Earth, interconnected organisms as part of the whole, rather than being in control.

Literature and culture provide language and narrative to express how ecological damage effects humans and nonhumans (e.g., animals, flora, other organisms), as well as the biophysical structures of the Earth. Ecocriticism ultimately affords critics, students, activists, writers, and global citizens a way to express these concerns both inside and outside of the academy and throughout our everyday lives.

There are many novels, short stories, plays, poems, or memoirs that have affected how people might perceive and value the environment. For me, the initial switch happened years ago in high school when a friend gave me a copy of John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row (1945). The novel has a protagonist named Doc, who is a marine biologist; it showcases the ecologies of coastal marine life in Monterey Bay, California, off of the Pacific Ocean. After reading Cannery Row, I could no longer perceive of life on Earth as anything but interconnected. My takeaway from the novel, and other literary works like it such as Alice Oswald’s contemporary long poem Dart (2002) or George Eliot’s Victorian novel The Mill on the Floss (1860), is always the same. Organisms, including but not exclusive to humans, depend upon each other for survival. This understanding of our interconnected ecological futures (involving the past) is now part of my value system because of literature and culture.

What literature has changed your values about our environmental futures?

Featured image credit: Smoke Coming Out of Pipe. Public Domain via Pexels .

The post Valuing our ecological futures appeared first on OUPblog.

The political legacy of Andrew Jackson

In response to the elitism of the Founding Fathers, Andrew Jackson shaped his legacy as a political rebel and devoted representative of the common man. Today, that legacy has become a source of controversy. His advocates view him as a hero who promised to maintain democratic tradition and protect American values. But new evidence has revealed the immorality behind his policies and legal regimes.

In the following excerpt from Avenging the People, historian J.M. Opal discusses these interpretations of Jackson’s presidency, and disputes the enduring image that Jackson painted of himself.

Sometime after rising to international fame in 1815, Andrew Jackson lamented that his critics had him all wrong. Whether from ignorance or malice, they spread rumors and lies about his actions and motives. They also smeared his wife, Rachel, with whom he often shared his sense of persecution.

Although most Americans seemed to worship him, these attacks were still painful, for they hit core parts of the general’s self-image. His “settled course” in life, he told a trusted friend, was to honor the rigid code of behavior with which his mother had once entrusted him. He was, he believed, completely devoted to just dealings and always careful to avoid insults. He was, he insisted, especially loyal to the US Constitution. Yet his enemies said that he was “a most ferocious animal, insensible to moral duty, and regardless of the laws both of God and man.”

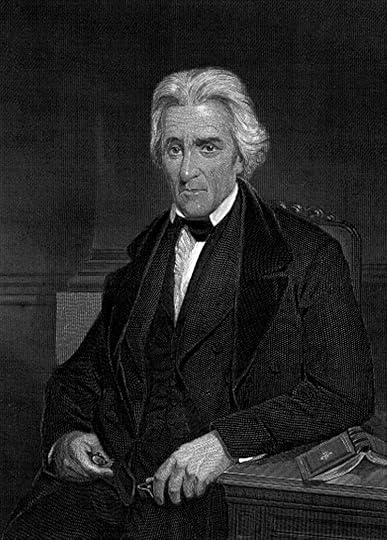

Image credit: “Portrait d’Andrew Jackson” courtesy of The General Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “Portrait d’Andrew Jackson” courtesy of The General Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I take issue with many things that Jackson wanted people to think about him. In particular, I question his place in America’s democratic tradition, drawing attention to the popular efforts and egalitarian ideas that he and his allies helped to bury. I try to avoid the strong pull of his personal legend and the historical narratives that bear his name, often moving him off the center of analysis to better see the people, places, conflicts, and choices that made him. I do not doubt the sincerity of Jackson’s belief in his own lawfulness, nor even the accuracy of that belief. He really did believe in the law. He certainly wanted justice. And his efforts to inflict his versions of both defined his life and career in ways that his other roles and identities— an Irishman, a southerner, a westerner, a soldier, a slave owner, a Democrat— cannot explain. His life was a mission, the mission was just, and its enemies would be judged.

Jackson was sure that his duties were authorized at the highest levels, and for good reason. His views on civil order and property rights often aligned with those of America’s first national leaders, who were also keen to draw the new republic into a larger society of “civilized” states. In this sense he was a proper nationalist. On the other hand, Jackson took an oath to a European monarch, was implicated in two secessionist plots, accused the federal government of suicidal cowardice, and threatened to incinerate a US government building and official. He chafed at the national terms of the rule of law and had little use for competing forms of American fellowship and sovereignty. A long series of regional traumas and global crises made him a particular kind of hero in 1814–15 and again in 1818–19, a larger-than-life “avenger” with a passionate bond to the American “nation.” His very name evoked a set of feelings and stories that marked Americans in some essential way— in their very blood, as the saying quite appropriately goes.

When America set about claiming its independence, Americans had little choice but to think critically about the rule of law and its relation to natural rights. The king and his minions were waging a “most cruel and unjust war,” the first constitutions of Vermont and Pennsylvania declared. They were pursuing the good people with “unabated vengeance.” South Carolina’s new charter accused the British of conduct that would “disgrace even savage nations,” while New Jersey’s deplored a “cruel and unnatural” hostility that left the people exposed to “the fury of a cruel and relentless enemy.” The king had not just withdrawn his protection, North Carolina reported, but had also declared open season on American persons and property, risking “anarchy and confusion.” Seeking allies in Europe, Benjamin Franklin stunned his British counterparts by accusing the empire of “Barbarities” once associated with frontier scalp hunters.

Stories of imperial savagery lent narrative form and moral purpose to eight years of war, during which some 40% of the free male population over 16 served in either a Patriot militia or the Continental Army. The larger theme of existential peril reappeared for the next 50 years, framing the life of Andrew Jackson, among many others, and shaping almost everything they said about virtue and republics, society and sovereignty, nation and allegiance. Unsure if the British Empire would let them live, they wondered if the rule of law would ever replace the state of nature. Unsure if the law of nations constrained any of the “civilized nations,” especially after the French and Haitian Revolutions set the world aflame, they argued over how and if they should respect the same standard. In so doing, they also debated how and if they were a “nation,” as well as a republic or union.

When and where was vengeance just and lawful, and when and where was it cruel and criminal? Who had the right to take it on behalf of the reinvented people? For Jackson they evoked memories so awful that the usual terms of law and politics did not apply, demanding new bonds of holy wrath and redeeming blood. His arguments thrilled many Americans and disgusted others.

Jackson’s beliefs were often more vehement than popular, and though he never hid them he also learned how to change the conversation. Ultimately, the sort of nationhood Jackson came to embody left Americans with a diminished sense of the law and their right to make it, indeed with less power, to be the nation they wanted to be.

Featured image credit: “The Brave Boy of the Waxhaws” by Currier & Ives, circa 1876. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The political legacy of Andrew Jackson appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers