Oxford University Press's Blog, page 334

August 19, 2017

Is there a right to report a disease outbreak?

Recently the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Health Systems and Innovation Cluster released its WHO Guidelines on Ethical Issues in Public Health Surveillance. This report was the first attempt to develop a framework to guide public health surveillance systems on the conduct of surveillance and reporting in public health emergencies.

The guidelines are described as a ‘starting point for the searching, sustained discussions that public health surveillance demands’. In the public health context, surveillance – monitoring for disease outbreaks – must be done in a manner that assures the privacy and safety of the individuals concerned. Data collected on individuals must be secure and de-identified unless, as Guideline 11 indicates above, specific individual information is required to protect populations from infection. Safety is also a priority to ensure that those who are infected are not vulnerable to attack or discrimination based on their illness. Privacy and safety, however, depend upon more than just the ethical practice of surveillance; it relies upon the social and political environments in which surveillance occurs—in particular, upon good governance and respect for human rights. As the Guidelines state, one of the ‘backbones’ of an ethical surveillance framework is ‘good governance’.

In many countries these conditions of good governance are not met either because individual rights cannot be protected or because government is not open to public scrutiny, or – as is often the case – both.

When good governance is missing, individuals and health practitioners who identify and want to report disease outbreaks can be put at risk by their government’s attempts to keep the extent of the outbreak concealed. This, in turn, only heightens the dangers confronting the wider population. Recently, I examined the extent to which international law on infectious disease control and response, the WHO International Health Regulations (2005); and the organization responsible for this instrument, the World Health Organization; establish a right to report disease outbreak events.

Since 2007, the year the International Health Regulations (IHR) came into force, states have been expected to meet eight IHR core capacity requirements to contain public health threats (broadly defined) under the new framework. These core capacity requirements include: 1) national legislation, 2) policy and financing, 3) coordination and National Focal Point (NFP) communications, 4) surveillance and response, 5) preparedness, 6) risk communication, 7) human resources and 8) laboratories. One significant inclusion in the adopted IHR was that states agreed to develop detection and response capacities, including the post of an IHR National Focal Point, who would be available 24/7 in every country to communicate outbreak events with WHO. In the revised IHR, the WHO was also given the right to receive reports of disease outbreak events from sources other than the affected state. The Article concluded: ‘only where it is duly justified may WHO maintain the confidentiality of the source’.

The WHO struggles to balance supporting a state in its conduct of public health surveillance and risk communication against supporting non-state actors’ right to report relevant and necessary outbreak information.

During my research I examined two situations: the outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in Saudi Arabia in 2012, and the outbreak of Ebola in Guinea in late 2013. These cases illustrate the mistrust that accompanies public health surveillance when states have a record of civil rights abuses. I found that there are many harms that come to individuals who report against the wishes of the state (including loss of employment, deportation, threat of imprisonment, and imprisonment) and the populations who often mistrust the information they are receiving from the government due to past oppressions and abuses. The WHO struggles to balance supporting a state in its conduct of public health surveillance and risk communication against supporting non-state actors’ right to report relevant and necessary outbreak information.

One way of addressing this impasse is by focusing more on the human rights implications of outbreak surveillance, response, and reporting. Advocating the right to report, as conceptualised under the revised IHR, requires a corresponding right for non-state actors to issue reports directly to the WHO. Under Article 9, the WHO has the right to receive reports from non-state actors, and the IHR instrument itself is grounded in an understanding of protecting human rights of individuals (Article 3). In cooperation with global disease surveillance platforms and the Group of Eight Global Health Security Initiative, more attention should be devoted to the accountability, transparency, and human rights provisions embedded within the IHR. Specifically, a framework that supports the rights and responsibilities of individuals and non-government actors to report outbreak events should be mooted. This has the potential to remedy not only the protection gap for those who feel professionally compelled to notify WHO under Article 9, but it may serve to allay the public mistrust and in turn, enhance the capability of public health surveillance.

Featured image credit: Photo by Tookapic. CC0 public domain via Pexels.

The post Is there a right to report a disease outbreak? appeared first on OUPblog.

Are you a philosophical parent? [quiz]

Some people are both parents and philosophers, but aren’t philosophical parents. Conversely, some people aren’t philosophers, or at least aren’t academic philosophers, but are nevertheless philosophical parents. So who are the philosophical parents? Are you one? Take the quiz below and find out!

(Pretend, for purposes of the quiz, that you’ve experienced every stage of parenthood and that you’ve had both a boy and a girl.)

Now that you know whether you’re a philosophical parent or not, you might be wondering whether it’s good or bad if you are. It’s good, I think—both beneficial and enjoyable—so long as being philosophical doesn’t crowd out other beneficial and satisfying stances. I’ll leave it to others to construct quizzes that determine whether you’re a loving parent, a fun parent, a well-informed parent. It takes all these things and more to be a good parent and to make parenthood meaningful and satisfying.

For more, read the illustrated discussion guide to The Philosophical Parent.

Quiz image: parent and child holding hands. CC0 via Pexels.

Featured image: person standing on dock. CC0 via Pexels.

The post Are you a philosophical parent? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 18, 2017

Is memory-decoding technology coming to the courtroom?

“What happened?” This is the first question a police officer will ask upon arriving at a crime scene. The answer to this simple question—What happened?—will determine the course of the criminal investigation. This same question will be asked by attorneys to witnesses on the stand if the case goes to trial. How those witnesses answer could mean the difference between guilt and innocence.

To answer these questions, of course, requires people to use their memory—their very human, very limited memory.

What if neuroscience could help the system reliably decode memories encoded in human brains so that recounted narratives of “what happened” would be as accurate as possible?

A recent study suggests that new brain-based memory recognition technology may be one step closer to admissibility in the courtroom. The results find that American jurors can appropriately integrate brain-based memory reading evidence in their evaluations of criminal defendants.

The finding is important because previous research on neuroscientific evidence in the courtroom has produced mixed findings. To be admissible, neuroscience expert testimony and exhibits must be relevant and must meet the jurisdiction’s requirements for scientific evidence (such as Daubert or Frye). But even if deemed relevant and of sufficient scientific merit, the evidence may still be excluded under Federal Rule of Evidence 403 (or its state equivalent) if the evidence’s probative value “is substantially outweighed by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.”

Scholars have suggested that in the context of neuroscientific evidence generally, and brain evidence related to deception in particular, Rule 403 concerns may be particularly salient. Yet despite concerns under Rule 403 about the prejudicial effects of neuroscientific evidence, the scholarly empirical literature on the effects of such evidence is decidedly mixed. As one review described it, “empirical research into the neuroimage bias has produced what might appear to be a tangled mess of contradictory findings … [and a] research quagmire.”

What if neuroscience could help the system reliably decode memories encoded in human brains so that recounted narratives of “what happened” would be as accurate as possible?

Amidst this quagmire of conflicting results, there is a growing appreciation that context matters. That is, research going forward is likely not to address “Does neuroscientific evidence affect outcomes?” (inviting a binary Yes/No answer), but rather “How much and under what circumstances does neuroscientific evidence affect outcomes?”

Shen’s new study extends this literature by showing how neuroscientific evidence may not always be more persuasive than traditional types of circumstantial evidence such as motive and alibi.

The study includes new results from multiple experiments examining the effect of neuroscientific evidence on subjects’ evaluation of a fictional criminal fact pattern, while manipulating the strength of the non-neuroscientific evidence. By manipulating the strength of the case, the study estimates the effect of introducing brain-based memory recognition with electroencephalography (EEG) evidence.

In two experiments, one using 868 online subjects and one using 611 in-person subjects, researchers asked subjects to read two short, fictional vignettes describing a protagonist accused of a crime. In one crime scenario, the defendant was accused of seeing an insider trading memo—but the defendant said he didn’t remember ever seeing such a memo. In the other crime scenario, the defendant was accused of stealing a unique blue diamond—but the defendant denied ever seeing it. In both cases, the defendant’s memory was central to evaluating his guilt.

Subjects were given several pieces of information about the defendant. The experiment manipulated two factors: (i) the expert evidence (none, incriminating brain evidence, exculpating brain evidence, incriminating polygraph evidence, and exculpating polygraph evidence), and (ii) the strength of the non-neuroscientific facts against the defendant (weak facts with an alibi, medium facts, and strong facts with a motive). Thus, in some scenarios there was alignment of neuroscientific evidence and circumstantial evidence, such as when John’s brain evidence suggested he was guilty and he also had a motive. Similarly, the evidence aligned when John’s brain evidence suggested he was innocent and he also had an alibi. It was the mixed conditions—where the brain evidence suggested a result that differed from the circumstantial evidence—that provided the most interesting test cases. In these cases, the study could see whether the neuroscience would seduce subjects and blind them to the rest of the evidentiary record.

It turns out that the neuroscientific evidence was not as powerful a predictor as the overall strength of the case in determining outcomes. The study concludes that subjects are cognizant of, but not seduced by, brain-based memory recognition evidence. In short: this brain-based evidence is not overly confusing, and likely would not be barred by Federal Rule of Evidence 403 (which prohibits overly confusing and prejudicial evidence from being admitted.)

Although brain-based memory recognition technology isn’t ready for courtroom use quite yet, such a day may not be too far away. What’s needed is more translational work to test the technology in real-world settings outside the lab.

Featured image credit: Skull by Free-Photos. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Is memory-decoding technology coming to the courtroom? appeared first on OUPblog.

Counting down to OHA2017

It’s no secret that we here at the Oral History Review are big fans of the OHA Annual Meeting. It’s our annual dose of sanity, a thoroughly enriching experience, a place to make connections, a great opportunity for young scholars, and the origin of some lively online debates. With nearly two months still to go before #OHA2017, we want to share a couple of reviews recently published in the OHR that we hope can help carry us all through until we are reunited in Minneapolis this October.

First, our very own Troy Reeves wrote an essay in which he reviewed two books about Joe Gould, including one by this year’s OHA Keynote Speaker, Jill Lepore. In it, Reeves traces his process of discovery and disillusionment with Joe Gould and his mythical book, An Oral History of Our Time. He asks how one can love an idea, and the possibilities it opens up, while acknowledging the complicated and problematic history of the man behind the idea.

Reeves’ review is a continuation of a line of thought Daniel Kerr raised in his 2016 article, “Allan Nevins Is Not My Grandfather: The Roots of Radical Oral History Practice in the United States.” Kerr’s piece asked what oral history family trees exist aside from the canonical version that imagines Allan Nevins as the progenitor of our discipline. This article has been a jumping off point for multiple recent posts on the OHR blog, including Allison Corbett’s oral history origin story, and Benji de la Piedra’s suggestion that the architects of the WPA’s Federal Writers’ Project can provide a scholarly ancestry that prioritized shared authority and meaningful encounters between researchers and the public.

We will bring you an insider’s take on Minneapolis in a few weeks, but for now we’ll point you to a piece that touches on a bit of local history. Barbara W. Sommer reviewed Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines by Jack El-Hai, asking what role oral history played in creating the book. El-Hai traces the rise and fall of the airline, which was headquartered near Minneapolis, and provides a visually interesting introduction to the company and the region.

Both of these reviews are now up on Advance Access for OHR subscribers, as are the rest of the articles that will appear in the print issue. Check them out now, and make sure to keep an eye on the blog in the coming weeks for interviews with OHR 44.2 authors, a sneak peak of #OHA2017, and more!

What do you love about the OHA Annual Meeting? Let us know in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image credit: “Downtown Minneapolis” by m01229, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Counting down to OHA2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

Eubulides and his paradoxes

Who was the greatest paradoxer in Ancient Western Philosophy? If one were to ask this question of a person who knows something of the history of logic and philosophy, they would probably say Zeno of Elea (c. 490-460 BCE). (If one were to ask the same question about Ancient Eastern Philosophy, the person might well say Hui Shi (c. 370-310 BCE). However, my story here is about the Western side of the Euphrates.)

According to Plato in the Parmenides, Zeno wrote a book in defence of Parmenides, containing many paradoxical arguments. Sadly, most of these paradoxes have not survived, with one notable exception: the famous paradoxes of motion, reported to us by Aristotle. With arguments such as Achilles and the Tortoise, and the Arrow, Zeno argued that motion was impossible. Zeno’s arguments have been much discussed through the history of Western philosophy, and — arguably — were finally laid to rest thanks to developments in mathematics in the 19th Century.

However, for my money, the answer would be wrong. The greatest paradoxer is not Zeno, but the Megarian philosopher Eubulides of Miletus (fl. 4c BCE). Again, nothing he may have written has survived; but fortunately we have commentators such as Diogenes Laertius who report his arguments. Eubulides is reputed to have invented seven paradoxes. Some of these seem to be variations of others, so that what we have is essentially four different paradoxes.

One of these is the Horns Paradox: if you have not lost something, you still have it. You have not lost horns. So you still have horns.

Most philosophers would now regard this as a simple sophism. Indeed, it is a standard fallacy, often called the ‘fallacy of many questions.’ To say that you have or have not lost something would normally presuppose that you had it to lose in the first place. So if you never had horns, the two premises both have false presuppositions. Whether that makes the premises themselves simply false, or neither true nor false, one might still argue about; but at least they are not true.

This one of Eubulides’ paradoxes is not, then, profound. However, the other three are a quite different matter.

The most famous of the paradoxes is the Liar Paradox: someone says ‘what I am now saying is false.’ Is this true or false? If it is true, it is false; and if it is false, it is true. So it is both true and false.

The paradox and its variations were discussed by Ancient philosophers, and have been subject to much discussion in both Medieval and modern logic. Indeed, those who have engaged with them in the 20th Century reads rather like a roll call of famous logicians of that period. But despite this attention, there is still no consensus as to how to solve such paradoxes. Solutions are legion; but the only thing that is generally agreed upon, is that all of them are problematic.

Another of Eubulides’ paradoxes is the Hooded Man Paradox: a man enters the room, wearing a hood. You do not know who the hooded man is. But the hooded man is your brother. So you do not know who your brother is.

This is a paradox of intentionality. Intentionality is a property of mental states that are directed towards some object or other — such as the hooded man. The topic of intentionality and its paradoxes was also discussed by Ancient and Medieval philosophers. However, in the 20th century, some influential logicians (such as W. V. O. Quine) dismissed intentional notions entirely as incoherent, largely because of this sort of problem. This is no longer the case, and various theories of intentionality have now been proposed. However, I think it is fair to say that there is still no general consensus as to how, exactly, to solve this sort of paradox.

Eubulides himself may have gone, but his paradoxes remain to haunt us.

The last paradox is — at least for me — the hardest of all, the Heap Paradox: if you have one grain of sand it does not make a heap. If you add one grain of sand to grains that do not make a heap, they still do not make a heap. So, starting with one grain, and adding grain after grain, you will never have a heap, even when the sand is piled up to the height of a mountain.

The Greek for heap is soros. Hence, paradoxes of this kind are called Sorites paradoxes. Such paradoxes concern predicates that are vague in a certain sense, like ‘heap’, ‘drunk’, ‘child’, where very small changes do not affect their applicability. Indeed, virtually all of the predicates one commonly uses are like this. These paradoxes, too, have an interesting history. There was some discussion in Ancient philosophy; none whatsoever in Medieval logic (that I am aware of, anyway); and virtually none in modern logic until the 1960s, when the topic took off spectacularly. (Why this should have happened so suddenly after 2,000 years, I have no idea.) Since then, a very large number of solutions have been proposed. But, again, there is no consensus as to how to solve paradoxes of this kind. All proposed solutions face very obvious problems. Crucially, they all seem to impute more precision to matters than there really is.

What my story tells, then, is that Eubulides invented three profound logical puzzles. The puzzles problematise three very different, but very important, philosophical notions: truth, intentionality, and predication. And despite an enormous amount of effort by logicians over the last two and a half thousand years, there is still no agreed-upon solution to any of them. This is why I say, that of Zeno and Eubulides, it is Eubulides who is the greater paradoxer.

This may well not have been how Eubulides was seen in his own day, however. Diogenes Laertius reports that one of the comic poets of the time wrote: ‘Eubulides the Eristic, who propounded his quibbles about horns and confounded the orators with falsely pretentious arguments, is gone with all the braggadocio of a Demosthenes.’ Well, Eubulides himself may have gone, but his paradoxes remain to haunt us.

Featured image credit: Plato’s Symposium by Anselm Feuerbach from Google Cultural Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Eubulides and his paradoxes appeared first on OUPblog.

August 17, 2017

Is there a place for the arts in health?

In a utopian world of abundant health budgets and minimal health challenges, it is probably fair to say that few would object to including the arts within hospitals or promoting them as a part of healthy lifestyles. Certainly, we have a long history of incorporating the arts into health (stretching back around 40,000 years), so it’s a concept many people are familiar with. But in an era of austerity, the value that the arts can bring comes under much closer scrutiny: do they really bring value or could they even be a distraction or a drain on limited funds? In fact, research is suggesting the opposite. In times of austerity, it is more important than ever that we look for creative ways to improve health.

The arts in medicine

The research evidence around the effects of the arts in healthcare settings is much larger than many realise. Not just ‘nice to have’, studies have shown how a range of art forms can have tangible health benefits. For example, music has been helping patients with Parkinson’s disease to walk, practising magic tricks has been found to improve hand function in children with cerebral palsy, the design of emergency departments has been shown to reduce violence towards staff , background music prior to surgery has been found to reduce the quantity of morphine needed post-surgery, video games have been shown to increase medication adherence in children with cancer, and songs have been found to improve cognitive function in people with dementia. Some of the most effective programmes are involving ‘problem-based solution’ models, whereby clinicians and health professionals are highlighting key challenges in their daily work and artists are devising creative solutions to these problems. Such work is showing that the arts are not just means of entertainment – they play functional roles within hospitals, hospices, and care homes.

The arts in public health

We find a similar, growing evidence base for the impact of the arts in preventing ill health. An article in the BMJ in 1996 showed that people who only engage with the arts and culture occasionally are more likely to die prematurely than people who engage regularly, even when accounting for factors such as socio-economic status. This finding has since been replicated eight further times in different population databases, not just for all-cause mortality but also for cancer mortality and cardiovascular mortality. But why do we find such an effect? There are a range of mechanisms at play here: psychological, physiological, social, and behavioural. For example, engaging with the arts supports mental health, reducing negative symptoms of mental illness such as anxiety and depression, and increasing positive aspects such as enhancing wellbeing. The arts also affect cognition, supporting temporal and spatial abilities, language, and memory, reducing our risk of dementia. The arts also support social identities and cohesion within society. And they can increase our agency and self-esteem, which in turn increase our ability to change behaviours in other aspects of our lives. As the emphasis on preventative health increases, there is a growing opportunity to harness these effects to help people live happier, healthier lives.

The arts in health communication

However, even if we acknowledge the role of the arts in public health and medicine, it can seem a stretch to suggest they have a role in extreme situations. Is there really a place for the arts in the context of global emergencies, such as epidemics? The Ebola outbreak of 2013-2016 demonstrated precisely how important the arts are in such situations. During the epidemic, there were abundant rumours and misunderstandings about the disease amongst locals, instances of people who were affected hiding from medical staff, Ebola survivors being outcast from their societies, and even healthcare workers being murdered. To combat this misinformation and raise public understanding, short films based on oral traditions of storytelling, radio serial dramas, and even electro-dance rap songs were created and went viral. Sensitive to local dialects and cultural traditions, these art forms became a route to communicate critical information in a way that people could trust, combatting the misinformation and helping health workers to carry out their work. Across the world there are programmes harnessing this power of the arts in health communication, from theatre productions to educate about diabetes, to schools crafts workshops to explain the risk factors for cancer. The arts can be direct and accessible ways of communicating crucial messages in ways that people from a wide range of backgrounds can relate.

In times of austerity, it is more important than ever that we look for creative ways to improve health.

The health economics of the arts

The examples given here are by no means the only ways that the arts can play a role in health: work in medical humanities, healthcare design, arts therapies, and arts-based training for staff provide further arguments for their importance. Yet despite the evidence, there can still be caution about the cost of engaging the arts in health. Should we be spending money on arts when such tight budgets mean there are staffing shortages or a lack of beds? Surprisingly, much of the spend on the arts in healthcare does not come from healthcare budgets; arts organisations, charities, and philanthropists fund a plethora of work around the UK and internationally. Further, many arts in health programmes have been shown to save money in health budgets. People who engage with the arts and culture in their communities are 65% more likely to report poor health, even when statistically controlling for socio-demographic and health-related factors. These people also make less use of health services. In fact, data from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport in the UK from 2015 shows that the estimated cost savings to the NHS for GP visits and psychotherapy alone as a result of people engaging with the arts and therefore using health services less is £695 million per year. In light of data such as this, Clinical Commissioning Groups in England have been trialling social prescribing and cultural commissioning programmes involving arts projects. Gloucester Clinical Commissioning Group runs a programme called Artlift whereby for certain health conditions such as chronic pain and low-lying mental health conditions, GPs have been referring people not for medication or psychotherapy, but to participatory arts workshops. The evaluation of the programme has found that, for people who took part, not only did they report improvements in their health, but over the following year the number of GP consultations and the number of hospital admissions dropped. This equated to a saving of £576 per patient, compared to a cost of just £360. The savings from 90 patients alone in the 12 months following involvement were over £42,000. These are just two examples. There are growing numbers of health economic evaluations that are providing more insight into how and where the arts can play a role in supporting health budgets, suggesting that far from being a drain on resources, the arts could be an additional means of support to healthcare.

The World Health Organisation defined health as a ‘state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. In times of austerity, it can be easy for us to forget everything that seems peripheral to the core mission of avoiding disease or infirmity. But keeping sight of the importance of creativity, arts, culture, and community engagement is critical. The arts are a powerful tool we should be harnessing.

Featured image credit: Flowers by ractapopulous. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Is there a place for the arts in health? appeared first on OUPblog.

The world of Jane Austen [timeline]

Jane Austen was a British author whose six novels quietly revolutionized world literature. She is now considered one of the greatest writers of all time (with frequent comparisons to Shakespeare) and hailed as the first woman to earn inclusion in the established canon of English literature. Despite Austen’s current fame, her life is notable for its lack of traditional ‘major’ events. She did not marry, although she had several suitors, and any references to private intimacies or griefs were excised from Jane’s letters by her sister Cassandra after the author’s death. Austen struggled to get many of her novels published, and some of her best-loved writings (including Northanger Abbey and Persuasion) were published posthumously.

Despite this, recent biographers have tended to see Austen’s life through the prism of significant and shaping emotional events — personal distresses and disappointments as well as literary accomplishments. With this in mind, we have taken a look at some of the key events in Austen’s life; her unhappy move to Bath, the influence of family ties and the French Revolution, publishing deals, and subsequent critical responses. Discover Austen’s world, and its impact on her writing….

Featured image credit: Three young woman are sitting at table in a garden having afternoon tea by Kate Greenaway, from Wellcome Images. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post The world of Jane Austen [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

We’re not singing a hillbilly elegy: challenging stereotypes in contemporary Appalachian song

In the run-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Appalachia took center stage as a potent symbol of the many ways that decades of economic globalization have marginalized the country’s white working-class voters. Liberal and conservative commentators alike were quick to point to the decline of places like McDowell County, West Virginia–where unemployment and opioid addiction rates have skyrocketed in recent years–as evidence that their preferred policy interventions were desperately needed. Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump visited Appalachian communities during their respective presidential campaigns; Trump even famously posed before the media donning a miner’s safety helmet during a May 2016 rally in Charleston, West Virginia.

Aside from the current resident of the White House, perhaps no one has profited more from the politicization of Appalachia than author J.D. Vance, whose Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis (Harper, 2016) rocketed to the top of the New York Times bestseller list in the months leading up to the election. Recounting his own troubled family life in Ohio’s Miami Valley and his struggles to find stability in a household marred by drug abuse, precarious employment, and abuse, Vance was quick to point to what he sees as a decline in “hillbilly” values—including adherence to a Protestant Christian faith, an unrestrained and violent hypermasculinity, and a powerful work ethic–as the primary cause of the challenges he faced. Appalachia, he argued, is a place in decline that can only be saved by reinvigorating “traditional” values.

Hillbilly Elegy was quickly picked up by a host of media outlets seeking insights into the minds of Trump voters, and several of them conducted their own reporting to add depth and color to Vance’s narrative of decline. Reviews in the New York Times and The Atlantic were generally positive (but with caveats), and Vance was interviewed by numerous publications to help explain the widespread appeal of Donald Trump among Appalachian voters. Several universities—including those that attract significant segments of their student bodies from Appalachia—have adopted the book for their campus reading programs and have invited Vance to speak on their campuses. Director Ron Howard—who famously portrayed one of Appalachia’s most beloved television characters, Opie Taylor, on The Andy Griffith Show during the 1960s–has also announced his intentions to develop the book into a major motion picture.

Yet, as many Appalachian studies scholars, commentators, and community activists have pointed out, Vance’s book might be a rather uninspiring account of his own difficult circumstances, but it is far from an accurate representation of daily life in Appalachia, and its efforts to blame poor and working-class whites for their economic and health struggles ignores the widespread structural challenges that have been detrimental to their well-being. Rather, Hillbilly Elegy traffics in familiar stereotypes of Appalachian laziness, inebriation, and fecundity that have been circulating since the late nineteenth century. But just as troubling is Vance’s seeming obliviousness to the many local and regional efforts that are being undertaken by Appalachian residents to sustain various cultural traditions—including foodways, storytelling, and arts and crafts–and to develop a vibrant and diverse economy throughout the region that seeks to replace the dwindling resource extraction and manufacturing bases that sustained the region for several generations.

Not surprisingly, music plays a key role in the ongoing cultural and economic vibrancy of many Appalachian communities. From old-time jam sessions held at restaurants that attract tourists to nationally and internationally syndicated programs like West Virginia Public Radio’s Mountain Stage and Kentucky’s WoodSongs Old-Time Radio Hour, musical activities throughout the region often seek to challenge stereotypes and to push against the narrative of Appalachian decline that has been circulating for more than a century.

Some of the most exciting contributions to these broad musical efforts have come from young musicians who have immersed themselves in the various traditional musics of Appalachia — the blues, Anglo-American balladry, fiddle and banjo tunes, and bluegrass—and used them as a jumping-off point for their own original creations. Many, but not all, of these musicians also identify as activists who work to challenge received narratives such as those offered by Vance and to build a more inclusive Appalachia.

One of the leaders of this movement is Saro Lynch-Thomason, a ballad singer, songwriter, visual artist, storyteller, and activist who lives in Asheville, North Carolina. A native of Nashville, Tennessee, Lynch-Thomason gained national attention in 2012 with an adventurous album, website, and lecture series called Blair Pathways: A Musical Exploration of America’s Largest Labor Uprising. Growing out of her work as an environmental activist who was fighting against the widespread use of mountaintop removal mining techniques in the Appalachian coalfields, Blair Pathways is a detailed musical exploration of Blair Mountain, West Virginia’s place in the long history of coal mining in Appalachia, from the early twentieth-century efforts to unionize the coalfields (a period in West Virginia history known as “the Mine Wars”) to recent efforts to protect the mountain from mountaintop removal, featuring Lynch-Thomason’s powerful singing voice along with those of former Carolina Chocolate Drops member Dom Flemons, labor singer Elaine Purkey, and ballad singer Elizabeth LaPrelle. Lynch-Thomason followed the release of this extensive album with a series of lecture-performances that took her to universities, community centers, and churches around the United States to tell about the intersections of environmental and labor struggles in the region. More recently, her song “More Waters Rising” has garnered national attention as a powerful song of solidarity in the face of contemporary political challenges.

Similarly, Wytheville, Virginia old-time banjoist and songwriter Sam Gleaves has drawn significant national attention not only for his exceptional takes on traditional string band music, but for his willingness to highlight the stories of LGBT people in Appalachia. His 2015 song “Ain’t We Brothers” recounts the story of Sam Williams, a gay West Virginia coal miner who faced extensive backlash in his community. Gleaves, who is also openly gay, told NPR Music’s Jewly Hight that “traditional music and traditional art really appeals to queer people, because in a lot of ways[,] it’s the music of a struggle; it’s the music of people who have fought against oppression.”

Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy offers few solutions to overcome the rather significant economic, public health, and environmental challenges that have emerged following the decline of coal. Rather, he offers a critique of modern Appalachian life that is grounded in romantic visions of an idyllic Appalachian past. But modern Appalachia requires modern interventions to solve its problems, and the region’s musicians are making significant inroads toward building a more inclusive and compassionate Appalachia, an Appalachia that can be transformed by creative problem-solving and a willingness to join together in community.

Featured image credit: “Appalachia” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 public domain via Pixabay

The post We’re not singing a hillbilly elegy: challenging stereotypes in contemporary Appalachian song appeared first on OUPblog.

August 16, 2017

On nuts and nerds

For decades the English-speaking world has been wondering where the word nerd came from. The Internet is full of excellent essays: the documentation is complete, and all the known hypotheses have been considered, refuted, or cautiously endorsed. I believe one of the proposed etymologies to be convincing (go on reading!), but first let me say something about nut. Although its etymology and history are puzzling, even mysterious, no one seems to care. Slang is a flower growing on a huge dunghill. Not unexpectedly, people tend to pay attention to the flower and disregard the dung.

Nut is an old word with excellent connections, and yet its etymology is obscure. The Old English for nut was hnutu. Many modern words beginning with n and l once had an h before those resonants. German Nuss and Dutch noot are obvious congeners of nut. Yet trouble begins early enough. German Nuss also means “a slap,” most often as an element in the compound Kopfnuss “a (light) slap on the back of the head” (Kopf means “head”). Opinions are divided on whether Nuss1 and Nuss2 are related. They may well be. But how are nuts connected with beating? There was indeed an Old English verb hnītan “to thrust, knock, come into collision,” with the uncertain by-form hnēotan. Did nuts regularly fall on people’s heads? More likely, nuts have always been associated with cracking (compare a hard nut to crack); hence the idea of beating and striking. If hnītan and nut are related, both must go back to some vague sound-imitating (onomatopoeic) base hVn, in which V stands for any vowel. (Direct ties between hnītan and hnutu cannot be established, because hnēotan may be a ghost word, while ī and short u belong to differed series of ablaut).

The Oxford Etymologist in disguise.

The Oxford Etymologist in disguise.The plot thickens once we remember that the Latin for “nut” is nux, properly, nuk-s, whose root is only too familiar to us from nucleus and nuclear (nut “kernel”). Both the beginning and the end of the Latin word are “wrong” from the Germanic point of view. Since Old Engl. hnutu and its cognate began with an h, we should expect kn– in Latin (by the well-known law of the First Consonant Shift: Germanic f, th, and h correspond to non-Germanic p, t, and k), but find no k. Also, the root of hnut-u ends in t, while the last radical consonant of nuk-s is k. Therefore, strict etymologists deny the affinity between nut and nux. But special pleading is a tempting procedure, and the closeness of nut and nux is so great that all kinds of rules have been proposed to keep the two words in the same family. It would be nicer if the Latin noun began with a k (knux), but, of course, if words for knocking came from saying kn-kn-kn and if hnutu-nux are offspring of this root, regularity in this area can hardly be expected (for a similar problem search for kl-words in this blog).

It won’t surprise anyone that nut acquired various metaphorical meanings. Not unexpectedly, at one time, all kinds of round, especially small round, objects began to be called nuts (as seen, among others, in nuts and bolts). Nuts “testicles,” nut “head,” and even nut “a trifling object” need no additional explanation. The baffling move is from nut “head” to nut “blockhead, numskull” and other non-trivial metaphorical senses. Those senses were recorded extremely late, as the evidence in the OED shows. First, we find nuts “a source of pleasure or delight” and for nuts “for amusement, for fun” (1625), an isolated example (apparently, this slang existed underground for centuries). In 1895, not to be able to do a thing for nuts “to be incompetent” was attested (bean shared a similar fate). In 1917, the nuts “an excellent or first-rate person or thing” surfaced in a printed text. I have a suspicion that nuts “testicles” prompted all such uses and that they were current long before they appeared in books. Jocular (crude or simply humorous) references to the male genitals as a source of strength or joy are ubiquitous in uncensored speech. My suspicion is borne out by the existence of the adjective nutty “amorous (!); fond, enthusiastic.”

From nutty we may perhaps move to nut “fop, masher” (on masher see this blog for 12 January 2011). In England, the word enjoyed great popularity in the decades (or at least in the last decade) before the First World War. Most aptly, one of those who contributed to the discussion of nut “fop” in Notes and Queries quoted Lafeu’s (or Lafew’s) remark on Parolles in All’s Well that Ends Well: “There can be no kernel in this light nut; the soul of this man is his clothes” (II: 5, 44). Besides, let us not forget the semantic and phonetic surroundings of this nut, namely, natty “neatly smart” and neat (the latter is a possible source of natty). Not only birds but also words of a feather stick together and influence one another. A nut of that epoch was someone who made a fool of himself in the eyes of non-nuts but who was also an analog of today’s cool dude. Since the nut of a century ago, like his sibling masher, was keen on impressing women, he obviously needed “nuts.” Already then some wits (wags, cards) spelled nuts as knuts, pronounced the first consonant, and joked that King Cnut (Canute, Knútr) was the first nut. One of the indefensible etymologies of nerd traces this word to knurd (drunk, if read backwards).

Supposedly, the kernels of this squirrel’s nuts are pure gold.

Supposedly, the kernels of this squirrel’s nuts are pure gold.It is the sense of nut “nitwit, madman, etc.,”which also became common only in the nineteenth century, that is the hardest to explain. Should we again return to Parolles’s “the light nut”? Was this the forgotten path to the metaphor: from “nut” to “light nut” and ultimately to “a dim-witted, dotty character”? Nut “the amount of money required for a venture; any amount of money” was coined in the US. Was it a product of the gold rush? Nuggets of gold must have been called nuts more than once. (Nug “lump,” the putative etymon of nugget, is another word of unknown origin.) I am slightly familiar with the old slang of Russian gold mining and find my guess not improbable.

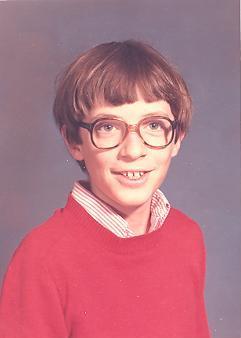

A nerd. Isn’t he a dear?

A nerd. Isn’t he a dear?There can be little doubt that nut has been an expressive word for centuries, and, as such, it could and did have expressive forms. There seems to be a consensus that the American coinage nertz ~ nerts “nonsense,” recorded only in 1929, is indeed an expressive variant of nuts. In this function, the syllable er is not uncommon (at least so in American English). Dr. Ari Hoptman called my attention to the pronunciation lurve for love in one of Woody Allen’s old movies. If nuts can be the etymon of nerts, I see no reason why nerd could not have the same source. To be sure, this idea has occurred to many people before me, but I wonder why it has not been accepted, why people keep pounding on an open door and say “etymology dubious, disputed, uncertain, unknown.” The etymology of such a word can never be “known,” but a sound hypothesis need not be listed for the sake of good manners along with all kinds of fanciful suggestions. Also, Dr. Seuss, who by chance coined his own nerd, should be left in peace amid his zoo. Nerd, like geek, wimp, and square, was launched as a derogatory term. With time, it acquired some endearing overtones. After all, not every intellectual is an old fogey or a social moron. But it is the origin, rather than the word’s later development, that interested us in this post.

Mixed nuts, like mixed nerds, are a delight.

Mixed nuts, like mixed nerds, are a delight.Such is today’s story of mixed nuts.

Image credits: (1) Squirrel by Oldiefan, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) Nutcracker by GraphicsUnited, Public Domain via Pixabay. (3) “Study of a portrait of a young nerd” by Ned Raggett, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr. (4) and Featured image credit: Mixed Nuts by cfinsbury, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post On nuts and nerds appeared first on OUPblog.

Travelling with Shakespeare

William Shakespeare is celebrated as one of the greatest Englishmen who has ever lived and his presence in modern Britain is immense. His contributions to the English language are extraordinary, helping not only to standardize the language as a whole but also inspiring terms still used today (a prime example being “swag” derived from “swagger” first seen in the plays Henry V and A Midsummer Night’s Dream). Shakespeare’s image even graced the British £20 note from 1970 to 1993, and people from all over the world to come visit the playwright’s birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon and the famous Globe Theatre in London.

However, it is not only in England that Shakespeare has left his literary mark: “All the world’s a stage” begins a monologue from As You Like It, and Shakespeare sets up his fictional stages all over the early modern world, most frequently in Europe and the Mediterranean shores. From Macbeth’s dreary Scotland to the “Kronborg” of Hamlet’s Denmark or the sunnier climes of “fair Verona”, there is a celebrated internationality in Shakespeare’s work. Often based on historic events or legends deeply embedded in Europe’s continental and regional histories, Shakespearean settings influenced viewers and readers not only in Shakespeare’s time, but right up to the present day.

Delve deeper into Shakespeare’s Europe with the interactive map below, looking at some of his most famous plays and their settings. Where will the bard take you?

Featured image credit: “Carte d’Europe” by Jean-Claude Dezauche, 1789. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Travelling with Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers