Oxford University Press's Blog, page 333

August 22, 2017

Keeping secrets in sixteenth-century Istanbul

In April 1576, David Ungnad was worried. The Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II had dispatched him to Istanbul in 1573 as his ambassador. Being obedient servants, Ungnad and his colleagues regularly sent detailed dispatches home. At the beginning of April, one such bundle of letters was intercepted and handed to Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha for inspection. Not only was there serious danger that the Ottomans would obtain knowledge of Ungnad’s secrets, in the process, they would also become aware of just how much the ambassador knew about matters which the Ottomans hoped to keep secret from him. For, Ungnad, as part of his job, coordinated a substantial network of spies and informants.

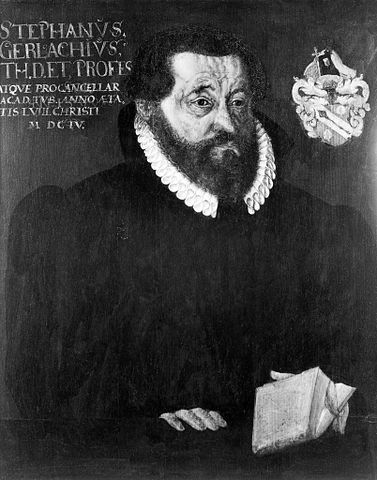

This episode is one of the many fascinating anecdotes recorded in the journal of Stephan Gerlach who served as the Imperial embassy’s chaplain. Educated in Tübingen where he later became professor of theology, Gerlach spent most of the 1570s in Istanbul.

After the Ottomans had obtained the letters written by the Imperial ambassador, discovering their contents was not a simple matter of opening and reading them. As Gerlach emphasizes, Ungnad made heavy use of ciphers and codes to protect his correspondence. Moreover, judging from the letters preserved in Vienna, this particular ambassador was unique in employing invisible ink. After development, the distinctive colour of such writing makes it clearly distinguishable from texts written in regular inks.

While Gerlach’s description of these measures, some exaggeration notwithstanding, is reasonably accurate, his claim that the ciphers were virtually unbreakable is not. The simple alphabetic substitution cipher–in which each letter is replaced by a corresponding symbol–can be broken with sufficient patience and linguistic expertise. In fact, the ciphertexts are sometimes easier to read than the corresponding cleartexts penned by the clerks in Vienna.

Sixteenth-century cryptographical literature–e.g. Johannes Trithemius’s (1518) and Giambattista della Porta’s De furtivis Literarum Notis (1563)–discussed more complex ways of making a text unintelligible to unintended audiences. Since early modern European states were notoriously short of the skilled staff necessary to ensure the speedy encryption and decryption of large volumes of official correspondence, the methods they relied on generally remained much simpler. Nevertheless, the ciphers actually used by Venetian diplomats undoubtedly provided greater security than those of the Austrian Habsburgs. As far as invisible inks are concerned, Ungnad relied on lemon juice, which, as Giambattista della Porta’s Magia Naturalis (1568, English translation 1658) makes clear, was one of the simplest methods known at the time. Nevertheless, some of Ungnad’s practices–such as hiding information in otherwise innocent letters–mirrored those employed by Venetian spies in the same period.

Image credit: Stephan Gerlach. Painting attributed to Hans Ulrich Alt. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Stephan Gerlach. Painting attributed to Hans Ulrich Alt. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Regardless of the question of how sophisticated or simple Habsburg ciphers, codes, and steganographic techniques were, the Ottomans’ apparent failure to exploit Ungnad’s letters in April 1576 had little to do with a lack of ability or even linguistic barriers. For the task of decrypting the letters was given to native speakers of German and Hungarian, all of whom were what contemporaries called “renegades,” men who had converted to Islam and joined the service of the Ottoman sultan.

The most prominent person entrusted with the task was Adam Neuser. Neuser had originally been a preacher in Heidelberg but had sought refuge in the Ottoman Empire when his Unitarian theology and a draft letter to Selim II led to his prosecution for heresy and treason. In Istanbul, he converted to Islam and undertook translation work for the grand vizier. University educated, the man certainly had the intellectual tools to tackle Ungnad’s cipher and he demonstrably possessed cryptological expertise.

However, Neuser worked for the Austrian Habsburgs. When he was given Ungnad’s letters, he falsified translations, secretly allowed incriminating documents to be exchanged, and persuaded his colleagues to abandon their decryption attempts. This time, at least, Ottoman efforts were thwarted because the Austrian Habsburgs had successfully penetrated their ranks.

It is tantalizing that David Ungnad himself nowhere discusses this episode. Perhaps the ambassador preferred to keep it under wraps rather than drawing attention to the value of the Ottomans’ find. The question of the anecdote’s authenticity cannot be resolved from the Viennese records, therefore. It seems clear enough, though, that if the episode had indeed occurred, it caused no noticeable disruption in the information flow between Istanbul and Vienna. Given the pace of the mail as well as the obstacles and dangers which couriers faced during their journeys, a delay of less than two weeks in the arrival of a letter was hardly a cause for concern.

Beyond the question of espionage, counter-espionage, ciphers, and code-breaking, this little story illustrates the ambiguity which Christian Europeans displayed towards those who “reneged.” Ungnad referred to Neuser as the “apostate from Heidelberg,” thereby emphasizing what, in his eyes, was a betrayal of Christianity as much as Christendom. Indeed, conversion to Islam was commonly read as a declaration of loyalty to the sultan. Nonetheless, the diplomat freely admitted to Emperor Maximilian II that Neuser was among his best agents.

From an Ottoman point of view, one might easily infer the lesson that admitting foreigners presents a serious security liability. But for every seemingly disloyal new Muslim there were numerous converts–such as the hero of Lepanto Kılıç Ali Paşa (born Giovanni Dionigi Galeni), the interpreter Mahmud Bey (Sebold von Pibrach), or the “intelligence officer” İbrahim Bey (Pál Márkházy)–whose talents, skills, and knowledge were valuable and whose commitment to the Ottoman Empire was beyond reproach. Most of the time, the benefits outweighed the risks.

In this particular instance, the danger was limited. Yes, the ongoing contest for the throne in Poland-Lithuania had the potential to spark a war which would mobilize the Ottoman army in support of their Transylvanian vassal Stephen Báthory against the rival Habsburg candidate. But then again, the two powerful empires had only just renewed the peace between them and neither party had a particular interest in reviving large-scale military confrontation. Accordingly, the whole affair was swept under the carpet. Doing so was made easier by the fact that, to all appearances, Ungnad’s secrets remained safe.

Featured image credit: Topkapı Palace, Istanbul. Photo by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Keeping secrets in sixteenth-century Istanbul appeared first on OUPblog.

Combatting the spread of anti-vaccination sentiment

Vaccines are one of humanity’s greatest achievements. Credited with saving millions of lives each year from diseases like smallpox, measles, diphtheria, and polio, one would expect vaccines to be enthusiastically celebrated or, at the very least, widely embraced. Why is it, then, that we are witnessing the widespread proliferation of anti-vaccination sentiment? Why is it that some communities in North America, including, for example, areas of Vancouver, are now turning their backs on vaccines in numbers large enough to threaten herd immunity? Current research has shown that over 25% of Canadian parents are concerned or uncertain about the association between vaccines and autism. A similar percentage of parents worry that vaccines could cause serious harm to their children. What are the social forces contributing to this rise in vaccine hesitancy?

There are multiple interrelated reasons for the existence and spread of both aggressive anti-vaccination and subtle vaccine-hesitant perspectives, but they often stem from issues surrounding trust, personal choice, and fear. Vaccination myths are being circulated in communities and wide social networks, and these myths create scientifically unwarranted concerns about the risks and safety of vaccines. While many parties contribute to the proliferation of these myths, there is little doubt that complimentary and alternative (CAM) practitioners are playing a role.

Numerous studies have demonstrated links between CAM and anti-vaccination attitudes; CAM use is associated with not vaccinating children, and CAM training is associated with anti-vaccination attitudes. In our recent investigation of 330 naturopath websites in the Canadian western provinces of British Columbia and Alberta, we found 53 websites containing vaccine-hesitant discourse. That is to say, these websites explicitly denounced vaccinations, raised issues with the harms and risks of vaccines, and/or offered alternative vaccination services such as homeopathic prophylaxes. This easily accessible discourse can contribute to confirmation bias for those already critical of vaccines, and can also heighten skepticism among those with doubts. With increasing numbers of the population going online for health information, it is reasonable to be concerned that discourse of this kind might plant unwarranted seeds of doubt in the minds of some individuals previously comfortable with vaccines. These messages could also spread: if you’ve ever seen someone share fake news on Facebook, you know what we are talking about.

Why is it that some communities in North America […] are now turning their backs on vaccines in numbers large enough to threaten herd immunity?

Notably, it is incorrect and unfair to arrive at the conclusion that CAM = antivaxx. It is, however, important to recognize the presence of significant anti-vaccination sentiment in these communities. We must begin to think of ways to tackle myths and behaviours that put both individuals and communities in harm’s way.

The solutions, of course, will vary by jurisdiction. As outlined in our paper, in Canada the Competition Bureau and Health Canada could modify advertising standards to curb treatment and performance claims online, and the latter institution could even act to entirely prevent the sale of demonstrably ineffective natural health products like homeopathic remedies. In addition, the right of CAM practitioners like naturopaths to self-regulate their profession could be reconsidered, as there is little indication that evidence-based standards are enforced. Alternatively, third party oversight could force the adoption of such standards. Lastly, better application and enforcement of existing law could help. As more naturopaths and other CAM practitioners position themselves as primary care providers, they become legally responsible to uphold existing common law standards of informed consent. Failing to disclose the overwhelming scientific evidence supporting vaccines when recommending not to vaccinate or to use an ineffective vaccine alternative likely constitutes negligence.

Vaccines are a matter of life and death. We live in a society privileged to have access to incredible medical developments that empower us to make decisions that improve life for ourselves and others. We owe it to ourselves and others to ensure the science of vaccines is not obscured by those attempting to inject doubt and fear into the conversation.

Featured image credit: Virus by qimono. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Combatting the spread of anti-vaccination sentiment appeared first on OUPblog.

Andy Warhol’s comfort food for the apocalypse

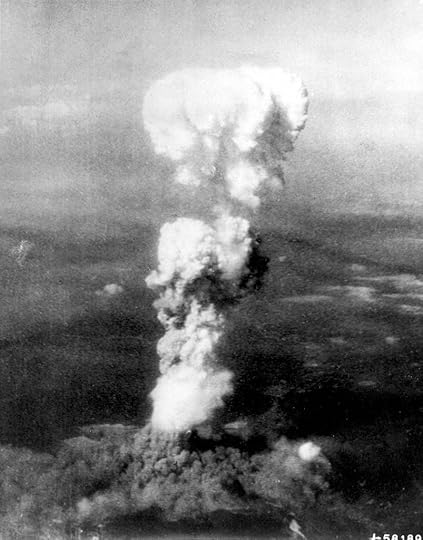

Birthdays are complicated. They are cause for celebration but also remind us that we are closer to death. Such duality would not have been lost on Andy Warhol (1928-1987), an artist who strove throughout his career to find images that could house such contradictory notions. These mutual feelings of jubilation and morbidity would have become especially apparent on Andy Warhol’s seventeenth birthday on 6 August 1945, when the United States dropped a nuclear bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. For the rest of his life, Warhol shared his own birthday with the birth of the nuclear age and the recognition of the potential for a human-engineered global apocalypse. As the Cold War battle between the United States and the Soviet Union heated up in the 1950s and early 1960s, fears of nuclear apocalypse became especially acute.

While Warhol directly referenced nuclear weapons in a number of works throughout his career–most memorably in Red Explosion from 1963, with over thirty silkscreen images of an atomic test blast–his most interesting explorations of the subject are those that tackle the subject obliquely, even covertly. With its deadpan, repeated depictions of one of the most basic American consumer goods, 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans from 1962 is just such a work. The work harbors a sense of existential dread just beneath its banal surface, simultaneously blocking and calling to mind disaster, specifically Cold War apocalypse.

To understand how a can of soup is able to convey terror, we must consider Warhol’s early commercial art experience. After graduating from Carnegie Tech in 1948 with a degree in Pictorial Design, he moved to New York. Warhol soon became a highly successful illustrator, valued for his drawings for record covers, magazine articles, and, most of all, advertisements. For instance, in 1955 he was hired to reinvigorate the image of I. Miller, an upscale woman’s footwear company. Warhol’s drawn advertisements appeared regularly in the New York Times until 1957, each one thus visible to millions of readers. On the whole, these ads appeared in the Sunday edition of the paper, beneath the announcements of high society engagements and weddings. With the wealthy brides helping to elevate the status of his drawn shoes, the surrounding context for these drawings was thus fundamental for their meaning and commercial impact. With these repeated appearances in the same section of the newspaper, Warhol would come to understand the interdependence of advertising and editorial content–how they work in tandem. And such lessons from commercial art would continue to inform Warhol’s work once he decided to become a fine artist around 1960.

“Atomic cloud over Hiroshima” by Enola Gay Tail Gunner S/Sgt. George R. (Bob) Caron, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Atomic cloud over Hiroshima” by Enola Gay Tail Gunner S/Sgt. George R. (Bob) Caron, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Returning to 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans, the work does not seem to harbor any feelings of atomic dread; on the contrary, some critics have viewed the work as celebrating an iconic American brand. And it does not look like traditional art. Around this time, Warhol said, “I want to be a machine,” and this work attempts to deliver on that promise. Despite being hand-painted, the canvases are nearly identical, save for the variety of the flavor of soup (all thirty-two varieties available in 1962). After a decade of the macho, emotionally-laden paintings of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and others, Warhol wanted to make art that avoided explicit displays of feeling. And seemingly straightforward depictions of Campbell’s Soup cans fit the bill.

But the cans nevertheless were deeply integrated into the dramas of contemporary events. At least this is the impression we get when flipping through the widely read and highly influential Life magazine from the late 1950s and early 1960s. The magazine was certainly the place where Warhol, a longtime subscriber, gained familiarity with the Campbell’s brand. If he came to understand, through his work for I. Miller, how advertisements could work with editorial content (fancy shoes among fancy brides), then perhaps Life taught him the ways that ads also worked in marked contrast with their surroundings. As media theorist Marshall McLuhan argued in 1964: “Ads are news. What is wrong with them is that they are always good news. In order to balance the effect and to sell good news, it is necessary to have a lot of bad news.” Put simply, stories about disasters, accidents, or violent wars help the effectiveness of advertising products like Campbell’s.

As such, during this period, Campbell’s advertising strategy in Life depended on purchasing the page after that week’s lead story or opposite the all-text editorial. Campbell’s soup cans were thus silent media witnesses to some of the period’s biggest events, many of which concerned Cold War tensions: there’s a Campbell’s ad marking the end of a long article on the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957; another one is next to an editorial from 1961 entitled “We Must Win the Cold War.” And there are scores of other similar examples. With the advertisements’ bright colors and bold graphics, readers would have been hard-pressed to maintain their focus on the adjacent news, reported in serious black-and-white. In such layouts, Campbell’s became the comfort food of the Cold War–a warm, comforting distraction in the face of stories about death and anxiety. And the repetition of these constructions in Life, week after week, certainly would have transformed a can of Campbell’s soup into a highly charged object when Warhol chose to paint it in 1962. Perceptive early viewers of the work picked up on just these associative qualities of Warhol; an important critic from Art News even noted that seeing Warhol’s work inspired thoughts of “the soup ad in Life magazine.”

Campbell’s connections to Cold War destruction during this period was only solidified by its appearance on shelves in photos of fallout shelters in Life and elsewhere. Even in Kurt Vonnegut’s darkly comic novel Cat’s Cradle from 1963, the protagonist, when faced with the end of the world, opens a can of soup from a fallout shelter. Campbell’s Soup was a staple of the apocalypse. Other consumer objects during the Cold War also harbored such duality. For instance, during the famous “Kitchen Debate” in 1959 the American Vice President Nixon and Soviet leader Khrushchev argued over the force of rockets and the merits of washing machines, all the while standing in a model American kitchen. In 1945, Warhol’s birthday was suddenly and permanently overshadowed by a mushroom cloud, and 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans some seventeen years later demonstrates how everyday objects also could not escape the bomb.

Featured Image credit: Warhol’s 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Maurizio Pesce, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Andy Warhol’s comfort food for the apocalypse appeared first on OUPblog.

August 21, 2017

Revisiting the My Lai Massacre almost 50 years later

On 17 March 1968, American soldiers entered a group of hamlets located in the Son Tinh district of South Vietnam. Three hours after the GIs entered the hamlets, more than five hundred unarmed villagers lay dead, killed in cold blood.

The My Lai massacre remains one of the most devastating events in American military history. Initially covered up by military authorities, the events of that day slowly came to light and caused international outrage, eventually leading to the prosecution of nearly thirty United States Army Officers.

In the following excerpt from My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness, historian Howard Jones examines the aftermath of one of the darkest days in military history.

How should we look at My Lai now, nearly fifty years after the events? For most Americans, it was a rude awakening to learn that “one of our own” could commit the kind of atrocities mostly associated with the nation’s enemies in war. Even to those who defended the American soldier, his image changed from citizen-soldier to baby killer—from poster boy hero and virtuous protector of the defenseless to cowardly murderer and rapist. It seemed impossible to reconcile My Lai with the concept of the United States as a chosen nation—an exceptional nation—built on republican principles and predestined by God to spread freedom throughout the world. In his memoirs after he had left the presidency, Nixon expressed the opinion of many Americans when he called it an aberration, unrepresentative of our country.

From one perspective, the story of My Lai came full circle on 10 March 2008, when Pham Thanh Cong, director of the Son My War Remnant Site and a survivor of the massacre, met at My Lai with former corporal Kenneth Schiel, a participant in the killings and the first member of Charlie Company to return to the scene. Cong had lost his mother and four siblings that day in My Lai and was surprised at Schiel’s appearance. Less than a week before the proceedings commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the massacre, they spent three hours discussing the events of 16 March 1968. Cong described the meeting as tense, though he appreciated Schiel’s effort to atone for what had happened. At first he did not admit to killing Vietnamese civilians. In the end, however, Schiel apologized even though continuing to maintain that he had been following orders. In August 2009, Cong would learn that in the United States William Calley had spoken publicly for the first time about his role in the killings.

Unlike Schiel, Calley refused to return to My Lai. Like Schiel, he claimed to have been following orders and felt no personal responsibility. To his friend Al Fleming, Calley still maintained, “I did what I had to do.”

How exceptional was My Lai? In The Guns at Last Light, Rick Atkinson shows that in the closing months of World War II American troops committed a number of horrific crimes against the French populace after landing in Normandy in 1944. Atrocities also took place in America’s other wars, including the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, the Korean War, and, most recently, in Iraq and Afghanistan. To many Americans, however, Vietnam seemed to offer more examples, perhaps in part due to the war’s longevity. In Tiger Force, Michael Sellah and Mitch Weiss uncovered a series of atrocities and mass killings of Vietnamese civilians just below Da Nang, committed by an elite army contingent over the course of seven months beginning in May 1967. Nick Turse, in Kill Anything That Moves, argues that US soldiers killed civilians throughout the Vietnam War as a result of government policies that made atrocities acceptable. My Lai was thus one of many.

The mass killings of civilians, Turse argues, were “the inevitable outcome of deliberate policies, dictated at the highest levels of the military,” and resulting in a “veritable system of suffering.” These policies established the conditions conducive to atrocities—a war of attrition based on body counts, search-and-destroy missions, free-fire zones, and soldiers trained to see the enemy as subhuman.

Image credit: My Lai massacre memorial site, in Quảng Ngãi, Vietnam by Adam Jones. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: My Lai massacre memorial site, in Quảng Ngãi, Vietnam by Adam Jones. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Turse draws heavily on thousands of pages of documents collected by the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group, a secret task force working out of the army chief of staff ’s office created by the Pentagon in 1970. The documents gathered by this wartime investigation, declassified in 1994, recorded hundreds of atrocities committed by US forces in Vietnam. Eight boxes of these materials, all extracts from the now-open CID and Peers Inquiry files, focused on My Lai, however, making it stand out from the others. General Westmoreland emphasized this point in his report. “The Army investigated every case, no matter who made the allegation,” but “none of the crimes even remotely approached the magnitude and horror of My Lai.” Whereas many of these atrocities in other parts of Vietnam came by air and at night, every victim at My Lai was killed during the day, many of them less than five feet away while facing their killers.

My Lai simply stands out, in part because of the numbers. 504 victims are listed on the marble plaque located near the entrance to the museum at the Son My War Remnant Site in My Lai. The victims broke down into 231 males and 273 females—seventeen of them pregnant. More than half of those killed—259—were under twenty years of age: forty-nine teenagers, 160 aged four to twelve years, and fifty who were three years old or younger. Of the remainder, eighty-four were in their twenties and thirties, and the rest ranged from their forties to the oldest at eighty. The numbers do not tell the whole story, but they say a great deal.

More than forty soldiers apparently took part in killing civilians. Of all the facts that emerged from the many investigations and reports, perhaps the most chilling is that not a single soldier on the ground tried to stop the killing.

My Lai made it imperative that the army institute major changes in training aimed at developing what Eckhardt called “professional battlefield behavior.” To understand the importance of restraint in combat, soldiers and officers must learn to disobey illegal orders. The only way to bring this about, Eckhardt insisted, was “to plainly state that the intentional killing without justification of noncombatants—old men, women, children, and babies—is murder and is illegal.” No one prior to My Lai had considered it necessary to teach US soldiers something so “obvious”; My Lai had made the obvious necessary.

Nothing today could ease the pain of what happened at My Lai, but it is crucial that we do not allow this tragedy to slip from memory.

Featured image credit: Co Luy – My Lai Massacre Village by Adam Jones. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Revisiting the My Lai Massacre almost 50 years later appeared first on OUPblog.

The man who made Big Ben

Big Ben, the great hour bell of the Palace of Westminster in London (a building better known as the Houses of Parliament), will controversially fall silent at noon on 21st August. Major conservation work to the clock, tower, and bells means that it won’t chime again until 2021. But despite the bongs of Big Ben being the national soundtrack of the UK from New Year’s Eve through to Remembrance Sunday, and housed in one of the most recognisable buildings in the world, very few people can name the man who was its creator. So, step into the limelight, Edmund Beckett Denison, first baron Grimthorpe (1816-1905).

He was, by all accounts, an appalling character, and no stranger to controversy himself. An ecclesiastical lawyer, much exercised by the law banning marriage to a deceased wife’s sister, Beckett was also an amateur architect, and talented horologist. Born in Newark in Lincolnshire, his father had been MP for the West Riding and Chairman of the Great Northern Railway. His favoured method of attacking his enemies was to fire fusillades of bilious correspondence at the letters pages of The Times (Charles Barry, the architect of the Houses of Parliament sued him for libel), and he was so notoriously aggressive and unpleasant that a condition of his repeated election as President of the Horological Institute was that he would never to attend its dinners. On building himself a house at Batch Wood, near St Albans in Hertfordshire, he proudly declared himself to be, ‘the only architect with whom I have never quarrelled’. And his gross over-restoration of St Albans Abbey brought a new verb into the English language – ‘to Grimthorpe’, that is, to trash a historic building.

Statesmen No. 559: Caricature of Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe by Leslie Ward. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Statesmen No. 559: Caricature of Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe by Leslie Ward. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Grimthorpe was arrogant, bombastic, and spiteful, but perhaps only a man of his steam-rollerish tendencies would have been able to succeed in creating the greatest clock in the world, particularly when up against the combined force of nearly a thousand opinionated and fractious politicians. Work on rebuilding the Houses of Parliament began in 1836. It soon became horribly delayed, and by 1849 there had already been five years of squabbles between competing clockmakers. At this point, the man who ended up with his name on both clock and the bells arrived on stage, and the others retreated.

In clarifying how the Great Clock should incorporate a telegraphic signal to Greenwich to assure its accuracy, Beckett produced a completely new design, and the clockmaker Edward Dent agreed to make it for him. It was finally completed in 1854, but it was to be another five years before the mechanism was installed, which would drive the dials and thus sound the chimes.

Warner’s of Cripplegate were duly chosen to cast the bells, but their London foundry was too small to cast the 18-ton bell required for the Palace’s timekeeper. Instead, the work was done at the firm’s new foundry in the village of Norton, near Stockton on Tees. On the morning of 6 August 1856 eighteen tons of metal in a mix of twenty-two parts copper to seven of tin was loaded into two furnaces, and three hours later released in a molten stream around the mould of the Great Bell to the cheers and applause of invited visitors. On 21 October, it arrived at the site of the Palace of Westminster to be tested. Beckett led the first trial of the bell using a 1485½-pound hammer, and ringings of the bell continued over the next year for public amusement.

Then disaster struck. At the end of October 1857, Big Ben cracked. Beckett explained to the Office of Works that ‘through some mistake or accident, which the founders say they cannot account for, the waist (the thin part of the bell) was made one-eighth inch thicker than I designed it’. It was typical of Beckett to blame someone else. What he failed to reveal was that his prescribed alloy formula, which he had insisted on in spite of Warner’s protests, had produced a metal casting more brittle than usual, and the hammer had been excessivly heavy when he showed off the bell’s sound to the public. The shattered pieces were then transported to George Mears’ Whitechapel Bell Foundry in east London. It was back to the drawing-board.

On 28 May 1858, the new bell crossed Westminster Bridge to cheering crowds. Problems did not stop there, however. The second Big Ben was found to be too big to be wheeled into the entrance of the Clock Tower for installation, even though it was smaller and lighter than its predecessor. As a result of Grimthorpe’s incompetence (though of course he blamed Barry), Big Ben had to be slowly pulled up the Clock Tower sideways and by hand to the belfry 200 feet above for over a day and a night. Finally righted at the top, it began ringing out in 1859, but cracked again soon after, again because of Grimthorpe’s faulty recipe. Yet turned by forty-five degrees, Big Ben has sounded out across London and the world ever since, with the crack still visible.

Featured image: Big Ben and Palace of Westminster in London by TravelAdvisor. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post The man who made Big Ben appeared first on OUPblog.

M. R. James and Collected Ghost Stories [excerpt]

In the following excerpt from Collected Ghost Stories by M. R. James, Darryl Jones discusses how the limitations of James’s personal, social, and intellectual horizons account for the brilliance of his ghost stories.

“The potential that ideas have for opening up new worlds of possibility caused James lifelong anxiety. Thus, his research, phenomenal as it was, tended habitually towards apocrypha, ephemera, marginalia —towards forgotten and perhaps deliberately irrelevant subjects. James was happy to acknowledge this himself. As a schoolboy, his autobiography records, he became fascinated by ‘blobs of misplaced erudition. . . . Nothing could be more inspiriting than to discover that St Livinus had his tongue cut out and was beheaded, or that David’s mother was called Nitzeneth.’ In 1883, the first paper James delivered to the Chitchat Society in Cambridge (to whom he first read a number of his important early stories) was entitled ‘Useless Knowledge’. Amongst the very greatest of his scholarly achievements is his 1924 Oxford edition of The Apocryphal New Testament, a collection of marginal or excluded scriptural texts whose intrinsic worth, James admitted, was highly dubious. The irresistible pull of the irrelevant for James was frequently remarked upon by his colleagues and contemporaries. His revered tutor at Eton, H. E. Luxmoore, noted the way in which James ‘dredges up literature for refuse’; Edmund Gosse, the great Edwardian man of letters, and lecturer in English at Trinity College Cambridge, remarked on ‘those poor old doggrell-mongers of the third century on whom you expend (notice! I don’t say waste) what was meant for mankind’; A. C. Benson believed that ‘no one alive knows so much or so little worth knowing’.

But it is the very limitations of James’s personal, social, and intellectual horizons that account for the brilliance of his ghost stories. The great effect and power of James’s stories lies in their acts of exclusion, the ways in which they use scholarship, knowledge, institutions, the past, as a rearguard action to keep at bay progress, modernity, the Shock of the New. They are straitened, narrow, austere, limited. And it is precisely this lack of expansiveness that makes him a great short story writer, and the very greatest ghost story writer, as these limitations become narrative preoccupations, simultaneously obsessions and games. The ghost story tends to be a highly conventional, formalized, conservative form, governed by strict generic codes, which often themselves, as with James, reflect and articulate an ingrained social conservatism, an attempt to repulse the contemporary world, or to show the dire consequences of a lack of understanding of, and due reverence for, the past, its knowledge and traditions. These traditions, when violated or subjected to the materialist gaze of modernity, can wreak terrifying retribution.

The nearest James ever came to a statement of theoretical principle about his chosen form—albeit one couched in a characteristic reluctance towards abstraction—was in the introduction he wrote to V. H. Collins’s anthology Ghosts and Marvels, published in 1924:

Often have I been asked to formulate my views about ghost stories and tales of the marvellous, the mysterious, the supernatural. Never have I been able to find out whether I had any views that could be formulated. The truth is, I suspect, that the genre is too small to bear the imposition of far-reaching principles. Widen the question, and ask what governs the construction of short stories in general, and a great deal might be said, and has been said. . . . The ghost story is, at its best, only a particular sort of short story, and is subject to the same broad rules as the whole mass of them. These rules, I imagine, no writer ever consciously follows. In fact, it is absurd to talk of them as rules; they are qualities which have been observed to accompany success. . . . Well then: two ingredients most valuable in the concocting of a ghost story are, to me, the atmosphere and the nicely-managed crescendo. (Appendix, p. 407)

It is a very revealing essay, not least because of its typically self-denying nature: can the ghost story be theorized, or not? The short story has ‘broad rules’, but ‘no writer ever consciously follows’ them. The ghost story also properly belongs in the past—not necessarily the distant past; but it is important that its setting and concerns be at least a generation out of date, in a world which pre-dates technological modernity:

The detective story cannot be too much up-to-date: the motor, the telephone, the aeroplane, the newest slang, are all in place there. For the ghost story a slight haze of distance is desirable. ‘Thirty years ago,’ ‘Not long before the war,’ are very proper openings. (pp. 407–8)” (xvi-xviii).

Featured image credit: “Foggy mist” by werner22brigitte. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post M. R. James and Collected Ghost Stories [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

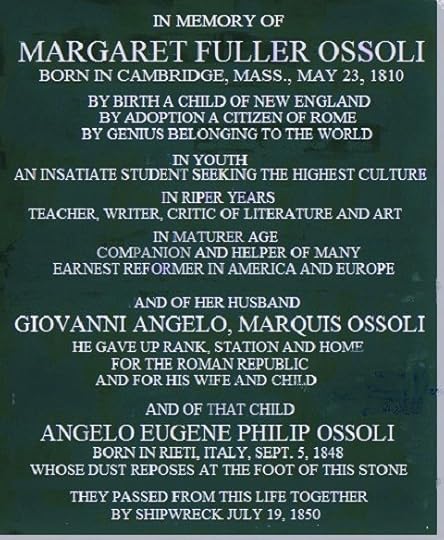

Margaret Fuller and the coming democracy

“Since the 30th April, I go almost daily to the hospitals,” Margaret Fuller told her friend Ralph Waldo Emerson in a letter on 10 June 1849. “Though I have suffered,–for I had no idea before how terrible gun-shot wounds and wound-fever are, I have taken pleasure, and great pleasure, in being with the men; there is scarcely one who is not moved by a noble spirit.” The noble men whom Fuller was attending were the Italians who had risen up in 1848 to declare an independent and democratic Rome. Under attack by French troops, they would soon see the fall of their new republic, as Giuseppe Garibaldi escaped Rome with his remaining troops and Giuseppe Mazzini fled into exile. Fuller also escaped Rome with her husband Giovanni Angelo Ossoli and their infant son Angelino, only to die with her young family in a shipwreck on her return to America in 1850. Fuller never returned home, but she had nevertheless embraced Rome, and thus had found her true home, the city that seemed always to have been waiting for her.

Fuller had met Italy’s great voice for independence, Mazzini, in London where she began a friendship and correspondence with him, regarding him the most compelling among the many thinkers and artists she met in her long-awaited tour of Europe. Mazzini was “not only one of the heroic, the courageous, and the faithful,” she wrote, “but also one of the wise.” The Italy that Fuller encountered when she arrived in 1847 was a society in turmoil, reaching desperately for the egalitarian values that Mazzini espoused. These same values, Fuller believed, were under threat in her own country. Looking at America from the vantage of Italy, she saw a nation cursed with the “horrible cancer of Slavery” and a “wicked War” with Mexico. “I listen to the same arguments against the emancipation of Italy, that are used against our blacks; the same arguments in favor of the spoliation of Poland as for the conquest of Mexico.” She urged her American readers to see Italy as a budding democracy, attempting to reconstruct itself on the principles that framed the American republic.

Inscription of Margaret Fuller Memorial at Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA by Foersterin via Wikimedia Commons.

Inscription of Margaret Fuller Memorial at Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA by Foersterin via Wikimedia Commons.Fuller is not often regarded as a democratic theorist, but her best-known work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, is a profound application of democratic principles to the rights of women. She urged women and men to hasten the day “when inward and outward freedom for woman, as much as for man, shall be acknowledged as a right, not yielded as a concession.” Her case arose not only from her personal encounters with exclusion and discrimination, but also from her yearly series of public “Conversations” for women in Boston, one of the most innovative projects in the reform-minded transcendentalist movement. Fuller used her rising prominence as a literary prodigy—the leading American authority on Goethe—to establish a forum through which women could speak openly among a supportive community.

To exchange ideas and impressions on history, literature, and mythology would stimulate, she believed, deeper self-awareness. Women would then ask, “What were we born to do? How shall we do it?” Those questions inevitably lead to discussions of equality. Taking these concerns to a new position as columnist for the New York Tribune in 1844, Fuller found a new America that both exhilarated and troubled her. She wrote on art and culture, but also tackled public issues that exposed the raw injustices and cruelties of the city. She condemned the New York’s shameful prisons, and insisted on the need for asylum reform and enlightened treatment of the mentally ill.

Fuller thrived intellectually as a New York journalist, but the politically charged atmosphere of Italy’s revolutionary struggle to better itself brought out her deepest, and most radical, instincts. The nobility that she found among the wounded soldiers claimed her completely. These heroes were the true signs of the just and egalitarian world that she trusted would eventually arrive. “The next revolution, here and elsewhere, will be radical,” she declared in 1850. “The New Era is no longer an embryo; it is born; it begins to walk—this very year sees its first giant steps, and can no longer mistake its features.”

Featured image credit: Margaret Fuller Portrait from the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Margaret Fuller and the coming democracy appeared first on OUPblog.

The ultimate quiz on environmental law and climate change

Climate change is one of the most controversial issues facing society today. The withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement on Climate Change marked a pivotal point for the fight against environmental destruction.

Barack Obama, 44th President of the United States, stated, “There’s one issue that will define the contours of this century more dramatically than any other, and that is the urgent threat of a changing climate.” With the threat level at an all-time high, humanity must keep informed and educated on all the aspects of environmental law and climate change.

Have you ever wondered what is the most widely discussed impact of climate change is? Take our Ultimate Quiz on International Environmental Law and Climate Change to find out this and much more.

Featured imagine Credit: “Climate Change” by HypnoArt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The ultimate quiz on environmental law and climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

August 20, 2017

Scientific progress stumbles without a valid case definition

Current estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the number of people in the United States with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) increased from about 20,000 to as many as four million within a ten-year period. If this were true, we would be amidst an epidemic of unprecedented proportions. I believe that these increases in prevalence rates can be explained by unreliable case definitions. For example, in 1994, the CDC’s case definition did not require patients to have core symptoms of the CFS. Making matters worse, in 2005, in an effort to operationalize their inadequate case definition, the CDC broadened the case definition so that ten times as many patients would be identified. Even though these estimates were challenged as bringing into the CFS case definition many who did not have this illness such as Major Depressive Disorder, as late as 2016, the CDC re-affirmed the merit in this broader case definition.

Another misguided effort occurred in 2015, when the Institute of Medicine (IOM) developed a revised clinical case definition that at least did specify core symptoms, but unfortunately also eliminated almost all exclusionary conditions, so those who had had previously been diagnosed with other illnesses such as Melancholic Depressive Disorders, could now be classified as meeting the new IOM criteria. This case definition has the unfortunate consequence of again broadening the types of patients that will now be identified, thus their effort also will inappropriately select many patients with other diseases as meeting the new IOM criteria. Making matters even worse, the clinical case definition was not designed to be used for research purposes, but it is clearly being used in this way, and one group of researchers has already inaccurately reported that the new clinical case definition is as effective at selecting patients as research case definitions.

Increases in prevalence rates [of CFS] can be explained by unreliable case definitions.

This comedy of errors becomes even more tragic with the recent development of a new pediatric case definition. As with past efforts, data were not collected to field test this new set of criteria. Even worse, medical personnel are asked to make decisions regarding symptoms without being providing any validated questionnaires, and this has the effect of introducing unacceptable levels of diagnostic unreliability. Scoring rules are so poorly developed that guidelines indicate that a child needs to have most symptoms at a moderate or severe level, but in reality, according to the flawed scoring rules of this case definition, youth can be classified as having the illness even if they report all symptoms as mild. These criteria further suggest that “personality disorders” should be assessed in children, as these disorders are listed as psychiatric exclusionary conditions; however, personality disorders cannot be diagnosed (or reliably assessed) prior to the age of 18, as personality characteristics are not fully developed until adulthood. Finally, these authors also require the youth to have at least six months of illness duration, whereas the Canadian criteria and others suggest that children with three months duration can be diagnosed with the illness. Other significant limitation of this primer have been mentioned by others. In summary, these authors failed to incorporate standard psychometric procedures that include first specifying symptoms and logical scoring rules, developing consistent ways to reliably assess these symptoms, and then collecting data to ensure that the proposed criteria are reliable and valid.

When a field of inquiry is either unable or unwilling to develop a valid case definition, as has occurred with CFS, the repercussions are catastrophic for the research and patient community. In a sense like a house of cards, if the bottom level is not established with a sturdy foundation, all upper levels of cards are vulnerable to collapse. Science is based on having sound case definitions that allow investigators to determine who has and does not have an illness. Having porous and invalid case definitions, whether clinical or research, affects not only prevalence estimates of CFS, but also has dire consequences for treatment approaches, as when individuals who have solely affective disorders are misclassified as having CFS, and when they improve from psychological interventions, it is easy to erroneously conclude that CFS is a psychiatric illness, which further stigmatizes patients.

Featured image credit: Guy by marusya21111999. CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post Scientific progress stumbles without a valid case definition appeared first on OUPblog.

George Berkeley and the power of words

According to a picture of language that has enjoyed wide popularity throughout the history of Western philosophy, language is a tool for making our thoughts known to others: the speaker translates private thoughts into public words, and the hearer translates the words back into thoughts. It follows from such a picture that before we can use words properly we must have thoughts corresponding to them. In 17th and 18th century European philosophy, the thoughts that correspond to most words were called ideas. Thus most philosophers from this period—including, for instance, John Locke (1632–1704)—held that if I am using a word like ‘apple’ properly, I have an idea of an apple when I say it and my saying it results in the hearer having an idea of an apple. This account may seem rather bland and commonsensical, but at the end of the 17th century it resulted in the burning of a book and the endangering of its author’s life.

This account may seem rather bland and commonsensical, but at the end of the 17th century it resulted in the burning of a book and the endangering of its author’s life. The book was Christianity Not Mysterious (1696). The author was the Irish philosopher John Toland (1670–1722).

Locke had argued that all of our ideas must be somehow derived from experience. According to Toland, traditional Christian theology contains numerous words that do not correspond to ideas derived from experience. Toland specifically argues that the positions of the various Christian churches on the Trinity and the Eucharist cannot be formulated without such words. Since meaningful words must correspond to ideas, it follows (according to Toland) that these religious ‘mysteries’ are literally nonsense. Toland therefore advocates an ‘unmysterious’ form of Christianity shorn of these traditional doctrines.

In the ensuing uproar, Toland fled the country. His book was burned by the public hangman in Dublin. Historians often treat this as the beginning of the Deist controversy in Britan and Ireland.

Bishop George Berkeley (1685–1753), generally regarded as Ireland’s greatest philosopher, was only eleven years old when these events took place, but a growing body of scholarship suggests that they had a profound impact on his thought. Berkeley believed that Toland was correct that we have no ideas corresponding to words like ‘substance’ and ‘Trinity’. In fact, Berkeley went further than Toland: Berkeley argued that we do not even have ideas corresponding to far less abstruse religious words like ‘God’ and ‘grace’. Yet, curiously enough, the use of these words makes a profound difference in the life of the believer.

Further, according to Berkeley, it is not only religious words that somehow make a practical difference without standing for ideas. Newtonian physics, for instance, is all about forces, like gravity, but what kind of experience could give us an idea of force? We experience the motion of falling bodies, but force is not the same thing as motion. We experience a certain sensation of effort when we support a heavy body, but force is not a sensation. Force is not, in fact, any of the things we experience. Hence, if all ideas derive from experience, there is no idea corresponding to the word ‘force’. Yet the employment of the word ‘force’ in Newtonian physics makes a profound difference. We simply couldn’t do without it.

Image credit: John Smybert, Portrait of George Berkeley, 1727. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: John Smybert, Portrait of George Berkeley, 1727. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.Still, as the title character of Berkeley’s 1732 work Alciphron puts it, “this is the opinion of all thinking men who are agreed, the only use of words is to suggest ideas. And indeed what other use can we assign them?” (§7.7, 1st edition). Berkeley is convinced that words must have some other use, for we do not have any grasp of what ‘grace’ or ‘Trinity’ or ‘force’ might be before we use the names, and yet it matters how we use (or don’t use) these words.

These reflections ultimately lead Berkeley to a radical conclusion:

The true end of speech, reason, science, faith, assent, in all its different degrees, is not merely, or principally, or always, the imparting or acquiring of ideas, but rather something of an active operative nature, tending to a conceived good (Alciphron, §7.17).

Berkeley’s fundamental philosophical insight is that we do not simply use words to represent the world and our thoughts about it, we use words to shape our world and our thoughts. In this way, religious and scientific language are just alike: both aim to assist us in the practical work of making the world a better place for ourselves and those around us. In fact, in the quotation above, Berkeley affirms without restriction or qualification that all speech, thought, and belief is like this. Thus Toland has not identified a problem for religious language, nor even a peculiarity about religious language. Religious language, like all language, has primarily practical significance and must be judged on the basis of the effects it produces, not the ideas it stands for.

Featured image credit: print by Marco Dente, ca. 1500. Public domain. Via The Rijksmuseum .

The post George Berkeley and the power of words appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers