Oxford University Press's Blog, page 332

August 25, 2017

What can the Zombie Apocalypse teach us about ourselves? [Video]

Stories of the Zombie Apocalypse are more than just entertainment. Zombies embody our fears of illness and death, and the stories that revolve around them force us to confront those fears–working almost as a coping mechanism.

The following excerpt from Living with the Living Dead analyzes the symbolism behind apocalyptic film and television. In the accompanying video, author Greg Garrett answers the question: why have cultures and societies, over the ages, used images of death and the walking dead to create meaning of their times?

Like war stories, like disaster films, like any kind of narrative that revolts and scares yet also delights us, the Zombie Apocalypse offers a laboratory for observing human emotion and experience. Its excess opens up a multitude of responses that don’t get explored in the course of our everyday lives, although these same choices lurk underneath the surface of all our lives.

It would seem, then, that in its headline for a recent discussion of The Walking Dead, the Atlantic has it right: “‘The Walking Dead,’ Like All Zombie Stories: … Not about Zombies at All.” The story of the Zombie Apocalypse instead is a way that we ask questions about what it means to be human. Along with a healthy dose of fear and excitement, we get our daily requirement of ethical and philosophical reflection, all in the guise of stories about the living dead.

Zombies are popular villains because they have affinities to us yet seem alien. As Kim Paffenroth points out in his study of the films of George Romero, zombies are creatures poised between two states, straddling the line between human and nonhuman and the boundary between living and dead, and there is something familiarly monstrous about this. Zombies are, in fact, scientifically demonstrated to be among the most frightening menaces we could watch, read about, or fight. Masahiro Mori, the robotics researcher, discovered in his research in the 1970s that humans feel increasingly comfortable with robots as they become more human in appearance, until they become too humanoid, at which point the identification becomes a painful one. While Mori says in a recent interview that science seems to be able to quantify this effect, it is an emotional proof as well as a physiological one; we know it because we feel it, not just because our brain waves change when exposed to such creatures: “the brain waves act that way because we feel eerie. It still doesn’t explain why we feel eerie to begin with. The uncanny valley relates to various disciplines, including philosophy, psychology, and design, and that is why I think it has generated so much interest.” Echoing Mori’s word “eerie,” Travis Langley notes of this research that creatures that are “eerily human while obviously nonhuman” seem to push all our buttons, and we can see this by noting how zombies reside in what Mori called bukimi no tani (the uncanny valley).

On a chart of the uncanny valley, the deepest dip representing close human likeness yet clear difference is where most zombie scholars would locate the zombie. This graphic evidence simply affirms what many of us already understood intuitively, that as Langley says, of all possible menaces, “a zombie will creep us out the most.”

The opening credits of the film “World War Z” offer a montage of contemporary problems: overpopulation and overcrowding, traffic jams, epidemics, toxic waste, all intercut with scenes of nature becoming ever more menacing, ending with swarms and feeding frenzies. It visually depicts a jarring and genuinely frightening idea: that nature operates by certain rules, and that we are pushing up against the very boundaries of those rules. In addition to (or perhaps because of) being supremely frightening in their depiction of almost-human monsters, zombies act as symbols for all sorts of free-floating twenty-first-century anxieties, from the spread of Ebola and Zika to the breakdown of the financial markets to changes in gender roles to the menace of global terrorism. While this conclusion may perhaps be startling if you are not a consumer of all things zombie, it is nothing new.

As Paffenroth noted in 2005, critics and fans have long known that zombie films can be “serious and thoughtful examinations of ideas,” and his book points out Romero’s powerful social criticism of American racism, consumerism, and individualism through the medium of zombie stories. That serious and thoughtful consideration continues today.

If you are an American or European troubled by the flood of Syrian refugees, their slow steady advance might bear some of the menace of the inexorable approach of the undead. If you are a white male in the United States or United Kingdom, the steady loss of power and control and the rapidity of change you experience might feel like the relentless bad news of the Zombie Apocalypse. Whether you are concerned about the seemingly unstoppable spread of religious extremism, or by the growing incivility in public life, or by the relentless breakdown of our infrastructure, or by the science of global warming, all of these menaces bear a relationship to the inexorable advance of the Zombie Apocalypse.

Even for those of us who toil every day at jobs that never seem to be finished, or that will have to be done and redone for a seeming eternity, the never-ending stream of zombies bears a correspondence to real life. What is the unfinished business in your life? What is the task that keeps coming, no matter what? For me, the Zombie Apocalypse is doing dishes: at my house, a never-ending stream of dirty dishes have to be rinsed, placed in the dishwasher, removed from the dishwasher, and placed in cabinets, and just when I think they are done, down, they get back up and the whole exercise has to be performed all over again. Every day offers a new battle; every day is the same old thing, and it exhausts me. Thus do zombies come to stand in not only for exotic and world-threatening menaces, but for mundane exertion, the attack of everyday life that paradoxically can be best told by stories about the walking dead.

Featured image credit: “tombstone-old-grave-stones-cemetery” by bernswaelz. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post What can the Zombie Apocalypse teach us about ourselves? [Video] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 24, 2017

Hitchcock and Shakespeare

There are two adjectives we commonly use when discussing artists and artistic things that we feel deserve serious attention and appreciation: Shakespearean and Hitchcockian. These two terms actually have quite a bit in common, not only in how and why they are used but also in what they specifically refer to, and closely examining the ways in which Hitchcock is Shakespearean can be very revealing. My aim in adopting this perspective is more analytical than honorific: we could rest easy by simply repeating the frequent description of Hitchcock as “our modern Shakespeare,” but let’s be restless and think more deeply about some of the details that make this more than merely a convenient (and for some, a problematic) statement of high praise.

Starting with the concrete, Hitchcock is more often than we usually recognize literally Shakespearean: he made a substantial number of direct references to Shakespeare and his works. We should bear in mind that in general Hitchcock did not frequently mention the names of artists that he admired and was influenced by, so his few specific references in his interviews and writings to a small group go a long way: Griffith, Murnau, Chaplin, and Pudovkin are part of that select group – and so is Shakespeare, always discussed thoughtfully and strategically, that is, as part of an effort to understand and explain his particular approach to cinema. As we might expect from a strong-minded artist, he is respectful, but not always deferential. In one of his early essays, “Much Ado About Nothing?” (1937), he comments extensively on the subject of Shakespeare and film, and his primary concern is defending the latter, even at the expense of the former, noting that “The cinema has come to Shakespeare’s rescue.” Cinema popularizes and keeps Shakespeare alive, and far from being “radically and fatally opposed,” the “art of cinema” improves “the art of Shakespeare,” surpassing the resources of words by making full use of the resources of “pictures.” He envisions cinema as not only a means to “develop a new regard for Shakespeare” but also as an art form that has new powers, an “unlimited range,” and the potential for a new master artist to cultivate its “enormous” territory. Hitchcock is thus perhaps the ultimate Shakespearean: he defends Shakespeare on film, but perhaps even more significantly, although implicitly, calls for a Shakespeare of the cinema. And my argument here is that he himself answered that call.

Hitchcock regularly includes direct Shakespearean references in his films. (H. Arthur Tausig, one of the few critics to pay attention to this subject [in his book Hitchcock: The Mind of a Master], compiles a short list that could certainly be expanded, and I draw from it in the following.) Hamlet appears repeatedly: for example, in Murder!, which reenacts parts of the play; in North by Northwest, the title of which is close to a direct quotation from Hamlet’s description of his feigned madness; and, perhaps most unexpectedly, in Topaz, as a character broods over betrayal and mortality. And there are references, incidental and otherwise, to a variety of additional plays: for example, the title Rich and Strange is from the The Tempest; Romeo and Juliet is quoted in Foreign Correspondent; Spellbound opens with an epigraph from Julius Caesar; the absent-minded doctor in The Trouble with Harry is reading Shakespeare’s sonnet 116 (“Let me not to the marriage of true minds”); and one of the episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents directed by Hitchcock, “Banquo’s Ghost,” reworks a dramatic moment in Macbeth. Some of this may very well be – in fact, surely is – second-hand Shakespeare: carried on from the original literary text that the screenplay was based on or additions by the screenplay writer. But Hitchcock presumably was the authority on what would stay and what would go, and while leaving something in may not be quite the same as putting something in, the effect is in many ways the same: Hitchcock’s works are loaded with Shakespeare.

This is true in ways that go beyond the direct quotations and allusions. There are analogues and models in Shakespeare of some of the defining elements of Hitchcock’s notion of “pure cinema” and his actual cinematic practice. Suspense perhaps comes first to mind when we think of Hitchcock, and he spent a lifetime insisting and demonstrating that the most effective and artistic kind of suspense is based not on surprise but on foreknowledge: in his classic example, not simply startling us by setting off a bomb unexpectedly, but rather alerting us to an impending explosion, so that the emotion and tension reside in the prolonged anticipation rather than the momentary blow up. This notion of suspense also applies to the structure and dynamics of his mysteries, which typically begin with rather than lead up to the revelation of “whodunit.” There are certainly some pleasures in the former approach, but greater depths in the latter, especially in pursuing mysteries that go far beyond identifying “whodunit.”

The Chandos portrait of Shakespeare, 1610. National Portrait Gallery, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Chandos portrait of Shakespeare, 1610. National Portrait Gallery, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Shakespeare’s tragedies are models of this kind of suspense, especially Hamlet, which is Hitchcock’s recurrent reference point when he has Shakespeare on his mind. He refers to it specifically when he describes what he feels is at the “core of a movie,” and at one point planned to make a film based on it. He never made this film, but there are thematic and structural elements of Hamlet (and other plays by Shakespeare) throughout the many films he did make. For example, he recognized the power of soliloquies, so critical in Shakespeare, and found imaginative ways to not only let his characters dramatize and expose themselves but also to convey interiority, sometimes transparent and other times opaque and hauntingly inexplicable, by cinematic soliloquies. (Psycho is a masterpiece of this technique.) And to say that Hitchcock’s villains are often Shakespearean is true but incomplete: it is particularly his approach to his villains that is deeply Shakespearean. The greater the villain, the greater the story is a Shakespearean lesson learned well by Hitchcock, as is the effort to make villains “attractive” and sympathetic, very often by having them address us directly and by showing things from their perspective.

Finally, Shakespeare is not just a series of texts but a larger than life person for Hitchcock, an essential and extremely useful model in shaping his career, persona, ambitions, and intentions as a filmmaker. Shakespeare is the exemplary artist, one who had an enviable amount of control over his productions, and who demonstrated that it was possible to be a commercial and popular success as well as a maker of acclaimed and innovative works respected and admired by critics and artists. The latter may have been Shakespeare’s legacy more than his lived reality, but Hitchcock was determined to be such a revered and rewarded public figure in his lifetime, instantly recognizable (he had his well-known signature portrait, as did Shakespeare), a master of art and entrepreneurship, an auteur and a brand.

Even one of the most well-known Hitchcockian trademarks, his cameos, has a direct Shakespearean analogue. Shakespeare was an actor as well as a writer, and regularly appeared as a minor character in his own plays, as documented in theatrical records and perpetuated in a widely circulated legend that he played the Ghost of Hamlet’s father. But I think Shakespeare’s spectral role goes far beyond that legendary performance. In many ways worth exploring in far greater detail than I have been able to do here, Shakespeare’s Ghost haunts and inhabits Hitchcock’s films, career goals, and notions and practice of “pure cinema.”

Featured Image credit: Portrait of Alfred Hitchcock. Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte, Public Domain via flickr .

The post Hitchcock and Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

Why a deteriorating doctor-patient relationship should worry us

If there is a single profound thing that has occurred in health care over the past couple of decades, that has neither benefitted patients or the doctors who care for them, nor the health system as a whole, it is the fairly rapid deterioration of the physician-patient relationship as the centerpiece of effective, satisfying, and high quality health care delivery. Instead of building system improvements around strengthening the relational care between our best trained health care professionals and patients, many health care systems around the world have chosen to place their faith in technologies like electronic medical records, which surveys show makes the doctor’s ability to connect with the patient and spend time with them as an individual more challenging and frustrating. In addition, the industry’s growing corporate takeover of health care delivery, driven by large health systems, insurance plans, and hospitals place the health care organization, not the individual doctor, in front of the patient at every turn. As a result, patients become “consumers”, and the role of the doctor in being the patient’s trusted ally shrinks.

That ongoing doctor-patient relationships built on high levels of trust, empathy, mutual respect, active listening, and expert guidance produce positive benefits is indisputable. These types of relationships are dyadic, interpersonal, and best nurtured through ongoing face-to-face contact between physician and patient. They are organically constructed and maintained, through a commitment by both parties to the relationship that each matters to the other, and behavior on both sides that demonstrate that commitment and the personal accountability that comes with it. If one examines the medical literature over decades, it is clear that these features of strong doctor-patient relationships favorably impact various health outcomes, patient satisfaction, patient compliance and commitment to self-management, and physician satisfaction and burnout.

Doctors benefit immensely from experiencing vibrant relationships with their patients. In survey after survey, physicians state that the most important and satisfying aspect of their jobs is the relationships they can have with their patients, and the intellectual and psychological stimulation that comes from knowing who they are, what they want and need, and perhaps how to get it to them. These same surveys show rising levels of job dissatisfaction, career regret, and burnout—and it should be no secret to assume that these negative outcomes are in part due to doctors experiencing less and less of the relational depth with their patients they so desire. Patients also know the personal value of connecting with a particular physician, and establishing a rapport and level of trust with them over time. We need health care often at the most vulnerable times in our lives, when we are filled with uncertainty and fear. The opportunity for us to share our thoughts and emotions with doctors, to have them hear us out and offer guidance based on who we are as unique human beings, and help us make important decisions about our health depends directly on having someone well-trained and accessible to believe in and trust.

Doctors benefit immensely from experiencing vibrant relationships with their patients.

Increasingly, though, the health care delivery system pushes a cheapened version of transactional care at the expense of doing things to strengthen this relational bond between doctor and patient. It commodifies health care services at every turn, creating buying and selling opportunities to push new, often unproven treatments and products onto patients for the sake of profit rather than quality of care; markets the illusory features of “company brand” to gain patient loyalties as if we were in the health care market for automobiles, televisions, or smartphones rather than improved well-being and emotional support; standardizes care delivery in ways that treat all patients as exactly the same in terms of needs and wants; and then seeks to have us believe that things like convenience and ease of access, while important and necessary in their own rights, are really the most important things we want from our health care delivery system.

Doctor by Parentingupstream. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Doctor by Parentingupstream. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Lasting damage is being done to the doctor-patient relationship because of these actions, and the corporate philosophy which sees health care as the next vast retail marketplace from which new types of profits can be squeezed. For example, my own interactions with the health care delivery system now feel impersonal, rushed, fragmented, and devoid of human feel. I am never able to see my “regular” primary care doctor, and every access point into the system is barricaded by a maze of phone systems, complex directions for how to seek out care, and poorly paid and motivated staff. The “convenience” I get is often a superficial and incomplete service or product that is only good for the most basic of my health care needs. In the meantime, I am told repeatedly how much the quality of my “experience” matters to insurance plans, medical offices, and hospitals, even as that experience involves bonding with or even seeing a given doctor less and less.

These experiences are not unique. I have interviewed patients and talked with friends and family members, and such experiences are increasingly typical of the system in which we find ourselves. Certainly, there may have never been a time when all doctors and all patients had deep, personally satisfying therapeutic relationships, the kinds that allowed unseen problems to be discovered and patients to share personal and deeply emotional aspects of their lives with their doctors. But what is being thrust upon us now is a greatly diminished version of the relational depth many doctors and patients experienced in the past.

It should worry us all, because if it is not recognized and meaningfully addressed soon by the industry, our children will grow up never knowing what their health care system and its most highly trained professionals could do for them.

Featured image credit: Hospital. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Why a deteriorating doctor-patient relationship should worry us appeared first on OUPblog.

10 facts about the waterphone

Unless you’re a pioneer for strange methods of sound production or the film director for a horror film, the chances are that you’ve never heard of OUP’s instrument of the month for August; however, that doesn’t mean that you haven’t heard it being played, and in fact, you probably have without realising!

The Waterphone is a unique, handcrafted instrument. It is named after its creator, Richard Waters, and was patented in 1975. Today, it is scored by both classical and film music composers. The instrument falls into the category of un-tuned percussion, and can be drummed, bowed, or even be used as a flotation device. Here are ten fun facts about this niche and diverse invention.

When designing the Waterphone, Richard Waters was inspired by three instruments: the kalimba (an African “thumb piano” that has been exported since the 1950s), the nail violin, and the Tibetan water drum. The resulting instrument combines the characteristics of these three instruments.

The Waterphone consists of a diaphragm which can be filled with water through a connecting aperture. The aperture also acts as a resonator. The diaphragm and aperture/resonator constitute the central section of the instrument, and are surrounded by protruding metal rods, known as “tonal rods.”

The tonal rods surrounding the water drum are tuned to a combination of micro-tonal and diatonic relationships, using even and uneven increments. This gives the Waterphone a very distinctive sound.

The Waterphone is only legitimately made and sold by one company in the United States. Buying the largest one available will cost you around $1700.

Image Credit: The Waterphone by Richard Waters. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: The Waterphone by Richard Waters. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Before playing the instrument, one needs to fill the bottom diaphragm and resonator of the instrument with distilled water. The amount of water in the instrument fine tunes its sound–experimenting with varying levels of water may consequently entirely change the timbre of the instrument.

The instrument can be played in a variety of ways: one can apply rosin to the rods and a bow and then use the bow to create sound, or apply rosin only to the rods and use damp hands as a substitute bow, or drum the Waterphone by covering the aperture and tapping the bottom and top of the instrument simultaneously. Here’s a helpful demonstration of some of the multifarious sounds you can create with the instrument.

By lifting the Waterphone when it is being played, one can swirl the water in the diaphragm, which results in the notes being bent and strange pre-echoes being created.

The strange sounds that can be made through note bending makes the Waterphone a perfect instrument for sound effects in film. In fact, it has been utilised in films such as The Poltergeist, The Matrix, and Let the Right One In.

The Waterphone has also been used by many classical composers too, reportedly to great effect in Howard Goodall’s song ‘Heart of the Woods’ from the musical The Dreaming.

Some have tried to use the Waterphone to make contact with sea animals. Reportedly, bowing the instrument with your hands emulates a whale’s call, and players of the Waterphone have been known to take the instrument into the sea, upturn it, and use it as a buoyancy aid when trying to make contact with these.

Image Credit: Humpback Whale Breaching Ocean by Skeeze. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post 10 facts about the waterphone appeared first on OUPblog.

The Paris Peace Conference and postwar politics [extract]

In 1919, Allied victors met in Versailles to set the peace terms following World War I. Their decisions, largely driven by the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and the United States, generated international political unrest that played a critical role in World War II.

In the following shortened extract from The Treaty of Versailles: A Concise History, historian Michael Neiberg discusses the Paris Peace Conference and its political aftermath.

The process of peacemaking lasted longer than the First World War it endeavored to end. The Paris Peace Conference began on January 18, 1919. Although the senior statesmen stopped working personally on the conference in June 1919, the formal peace process did not really end until July 1923, when the Treaty of Lausanne was signed by France, Britain, Italy, Japan, Greece, and Romania with the new Republic of Turkey. Lausanne was a renegotiation prompted by the failures of the one- sided Treaty of Sèvres, signed in August 1920 but immediately rejected by Turkish forces loyal to the war hero Mustafa Kemal.

The conference also produced the Treaty of St. Germain with Austria in September 1919, the Treaty of Neuilly with Bulgaria in November 1919, and the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary in June 1920. These treaties meted out relatively lenient terms to Austria, especially given the Austrian elite’s central role in starting the war in 1914. Hungary came out much worse than Austria did, largely to punish Hungarians for their postwar flirtation with a communist movement. Thus the conference had as much to do with postwar politics as perceptions of prewar guilt.

Interior of the Galerie des Glaces showing the arrangement of tables for the signing of Peace Terms, Versailles, France. June 27, 1919. Credit: Lt. M.S. Lentz. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Interior of the Galerie des Glaces showing the arrangement of tables for the signing of Peace Terms, Versailles, France. June 27, 1919. Credit: Lt. M.S. Lentz. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.But the centerpiece of the Paris Peace Conference was always the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, five years to the day after a teenaged Serbian nationalist, Gavrilo Princip, had assassinated Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo. The treaty and the conference are thus closely linked but not quite synonymous. None of the other treaties bear such a heavy historical responsibility for the world they created or the conflicts that followed, although perhaps they should. It is the Treaty of Versailles for which the Paris Peace Conference will probably be best remembered, and most often damned.

The dozens of statesmen, diplomats, and advisers who assembled in Paris in 1919 have come in for heavy criticism for writing treaties that failed to give Europe a lasting peace. Even many of the people most deeply involved with the peace process recognized their shortcomings early on, in some cases before the text had even been drafted.

Participants quickly grew disillusioned by the old- fashioned horse trading and back- room dealing that overwhelmed the ideals and principles of those who had hoped to fashion a better world out of the ashes of the war. Few people came out of Paris optimistic about the future.

Points in its defense notwithstanding, it is difficult to contradict the views of contemporaries and later scholars who have seen the treaty as a great missed opportunity and a source of considerable anger and disillusion in Europe and around the world. When in 1945 the leaders of the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain gathered in Potsdam to end the Second World War, they all blamed the failures of the Treaty of Versailles for having made the war of 1939– 45 necessary. The final decisions reached at Potsdam in 1945 were deeply influenced by these memories and the desire on the part of almost everyone at Potsdam to atone for the mistakes of their predecessors a generation earlier.

Of course, we must accept the basic truth that no document, even if thoughtfully written and elegantly implemented, could have closed the Pandora’s box that Europe opened in 1914. No treaty could have explained to the Germans why they had lost or made them accept the basic fact of their defeat. Instead, having been lied to by their senior leaders, millions of Germans accepted the convenient fiction that their armies had not really been defeated on the battlefield but had instead been betrayed at home. The fact that Allied armies never invaded German soil helped to fuel that poisonous myth, which German politicians intentionally spread to serve their own purposes. By June 1919, that version of history was already commonplace in Germany, and not only in right- wing circles.

Nor were the Allies, desperate to reduce defense expenses and the risks of further bloodshed, willing to commit to a long- term occupation or monitoring of Germany to enforce whatever terms the Germans might accept. Indeed, many Allied politicians, especially in Britain, wanted to see Germany quickly recover, both to restore a balance of power on the Continent and for German consumers to once more be in a position to buy British goods. Britain needed a treaty that kept Germany strong enough to serve as the engine of a postwar European economic recovery but not strong enough to pose a threat to the European political system. It is highly unlikely that any treaty could have negotiated that peculiarly deadly Scylla and Charybdis of the postwar years.

From the perspective of the French, the recovery of Alsace and Lorraine might excite nationalist politicians and serve as a patriotic background for numerous postwar celebrations, but it did not justify the deaths of an estimated 1.4 million Frenchmen. Nor did the French feel safe after 1919. In addition to the strategic considerations outlined, the French knew that they still faced a more populous Germany to their east. They also knew that their former allies were either gone (czarist Russia) or unwilling to sign a mutual security agreement to come to France’s help in the future (the United States and the United Kingdom). They also faced the tremendous task of rebuilding their farms, mines, and factories, while those in Germany remained intact. The euphoric mood of November 1918 did not last long.

The Treaty of Versailles is not solely responsible for the hell that Europe and the world did in fact go through just a few years later, but it played a critical role. If we are to understand diplomacy, decolonization, the Second World War, and the twentieth century more generally, there is no better place to begin than with the First World War and the treaty that tried to end it.

Featured image credit: “Dignitaries gathering in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, France, to sign the Treaty of Versailles” by Unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Paris Peace Conference and postwar politics [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 23, 2017

A fake etymology of the word “fake,” with deep thoughts on “Fagin” and other names in Dickens

I do not know the etymology of fake, and no one knows, but, since the phrase fake news is in everybody’s mouth, I am constantly asked where the word fake came from. I’ll now say what I can about this subject, in order to be able to refer to this post in the future and from now on live in peace.

This is a fakir. The word fakir has nothing to do with fake!

This is a fakir. The word fakir has nothing to do with fake!One certain thing about fake, noun and verb, is its extremely late attestation in books. We may disregard fake “one of the circles or windings of a cable or hawser, as it lies disposed in a coil,” for which the OED has no post-1867 citations and which seems to be a mere homonym of the word we are interested in. That nautical term was first recorded in 1627. “Our” fake, it appears, was borrowed from thieves’ language (“cant”), passed from low slang to colloquial English, and finally became fully respectable despite its unattractive meaning. In the OED’s database, no citations of fake “to do, to do for; plunder; kill; tamper with, for the purpose of deception, etc.” predate 1819. The noun (“an act of faking”) surfaced in 1827, but, surprisingly, fake “spurious, counterfeit” turned up in 1775, in Canadian Archives, to lie dormant until 1890.

Forecast: clear skies. Fake news.

Forecast: clear skies. Fake news.Probably fake, noun, verb, and adjective, began to circulate in the London underworld around the middle of the eighteenth century. Thieves became global before the rest of us, and their words are often international. The Low German or Dutch origin of fake has often been proposed. But later etymologists stayed away from fake, and, when they featured it, hastened to inform the users that the sought-after origin is unknown. Even the intrepid Hensleigh Wedgwood ignored it. Curiously, Walter W. Skeat, who wrote about fake several times, did not honor it in his dictionary. He might have felt uneasy about his own hypothesis, though he stated it elsewhere several times and in most forceful terms. Faker, as I understand, was the cant term for a follower of any occupation, nefarious or otherwise. For instance, chimney sweepers were called fakers. The civilized world probably learned the ignominious verb from Oliver Twist, where a pickpocket is called cly-faker. Cly means “pocket.” Skeat traced this word to Dutch kleed “garment,” related to Engl. cloth, and believed that it had originally meant any article of clothing. The Artful Dodger and other Fagan’s “boys” were taught to fake a cly.

I’ll reproduce Skeat’s earliest note on the subject (his abbreviations will be expanded): “Fake, to steal. This is a well-known cant word, to be found in the Slang Dictionary [Francis Grose, A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, 1785]. Like several other such words, it is probably Dutch. It corresponds to Middle Dutch fecken, ‘to catch, or to gripe,’ recorded by Hexham [Henry D. M. Hexham, A Copious English and Netherdutch Dictionary, 1675]. Curiously enough, this verb answers precisely to the Anglo-Saxon [= Old English] facian, to try to acquire, to wish to get, a word employed by King Alfred. The verb originally meant ‘to enclose,’ and is closely connected with Dutch vak, Anglo-Saxon fæc, German Fach, a word of rather widely extended meaning. The German Fach means ‘partition, compartment, department;’ the Old High German fah has the older sense of ‘enclosure, wall;’ the Anglo-Saxon fæc means ‘a space, interval.’’’ (Old Engl. æ had the value of a in the modern word fat.) The Dutch origin of fake is not improbable, but the rest of Skeat’s etymology does not look sufficiently persuasive.

Two things complicate the search for the origin of fake. First, the extremely vague meaning of the verb (just “do”); feikment has been recorded with the sense “thingummy, thingamajig,” so not an exact synonym for fakement “something faked (“done”).” Another complication is the existence of several look-alikes. The closest neighbor of fake is the obsolete verb feague, which meant “to beat, whip” and also “do for; settle the business of”; that is, almost the same as fake. Long before Skeat, Nathan Bailey, once an extremely popular lexicographer, derived feague from German fegen “polish, sweep”; Dutch vegen means the same. Skeat (as was his wont) once railed against an amateur who looked on feague as the etymon of fake, and, indeed, the sound change from g to k is quite unlikely. But we needn’t derive one verb from the other. Ours is a case of interlock, interlace, or (for word lovers) interdigitations.

I once dealt with the etymology of our F-word. All over the Germanic-speaking world, we find fik– ~ fak- ~ fuk- verbs meaning “to move back and forth” and “cheat.” I concluded that the English verb was a borrowing from Low German. Fake and feague are also possible loans (borrowed words, it will be observed, are always on permanent loan) from the same area. They probably meant “go ahead, move; act, do,” with all kinds of specialization, from “darn (a stocking),” to “cheat,” to “copulate.” Once they were appropriated by thieves, “go ahead, do,” naturally, became “deceive; steal, etc.” Since they sounded alike, they might, even must have influenced one another. I will risk suggesting that fake is part of the f-k family. Naturally, in Cockney, it was and is pronounced as fike. Those who adopted the verb knew the rules of the Cockney vowel shift, and, just as we today, when instructed “to chinge trines at foiv o’clock at the nearest stition,” understand our London interlocutor, knew perfectly well that fike meant fake and recorded it accordingly.

Now a few thoughts of mild profundity on Fagin’s name may be in order. (Fagin’s associates, naturally, said Figin.) It is known that in his youth Dickens worked with a Bob Fagin and was on good terms with him. The often-repeated idea that he later bestowed that man’s name on one of his most repulsive characters, to take revenge on a Jew who had dared to patronize him looks strained. Incidentally, Dickens always denied accusations of anti-Semitism. The other conjectures (of which there are not many) do not merit discussion. In my etymological dictionary (at fag), I suggested that, since Oliver was the thieves’ fag (“servant,” the sense universally known from British public schools), his role suggested the name of the fence, which automatically made Fagin Jewish. However, as Dickens noted, London fences were or had often been Jews.

The artful Dodger has just faked a cly.

The artful Dodger has just faked a cly.Perhaps my idea was not hopelessly far-fetched, but I now think that Fagin could also come from another source. Fagin was the teacher of fakers ~ faikers (feagers?), so that his name fit him perfectly. We will never know what made Dickens choose his characters’ names. Some of them are unusual, to put it mildly. Consider Pickwick, Copperfield, Chuzzlewit, and Pecksniff, among others. Peggotty surprised and irritated Miss Betsey Trotwood, who, too, had a rather extraordinary family name. Was it bestowed on her because she took care of a child, and trot, in slang, meant “young animal”? Was that the reason she called him Trot? (The boy grew up in a trot-wood, as it were.)

But to return to fake. It is a possible borrowing by London criminals of a piece of theives’ international argot, originally German or Dutch. Perhaps it once had the vague sense “to go ahead; move.” The amazing thing is not its putative origin but its adoption by the “cultured class.” A low word, a low thing.

Image credits: Featured image and (1) Untitled by ludovic, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. (2) “rain” by 陳 冠宇, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (3) “Mr Brownlow at the bookstall” by George Cruikshank, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A fake etymology of the word “fake,” with deep thoughts on “Fagin” and other names in Dickens appeared first on OUPblog.

What can baker’s yeast tell us about drug response?

Pharmaceutical drugs are an integral part of healthcare, but a treatment regimen that works for one individual may not produce the same benefit for another. Additionally, a given drug dose may be well-tolerated by some, but produce undesired (and sometimes severe) adverse effects in others. In the United States (with similar statistics in other parts of the world), serious drug adverse reactions account for over 6% of hospitalisations, with over 100,000 cases of fatal drug reactions. Understanding why individuals react to drug treatments differently is key for optimizing healthcare and avoiding potentially preventable harms associated with side effects.

Individual differences in diet, activity levels, and other lifestyle factors obviously contribute to this variation in drug response. However, this variation also has a genetic basis. This is evidenced by results of twin studies, and ethnicity-specific differences in response to drugs such as anti-cancer agents. By now, a number of genetic variants have been linked with variations in drug response. These can be classified into several major groups:

Variants that alter the therapeutic target of the drug: These can affect how well a drug can exert its effect on the cell, and hence the patient. For instance, asthma patients with a mutation in the gene ALOX5 (which encodes 5-lipoxygenase, an enzyme needed for manifestation of asthma symptoms) fail to derive a clinical benefit from the anti-asthma drug ABT-761. The mutation in question reduces the expression of ALOX5; it could be that this reduces the effect of ABT-761 by reducing its path to affect the cell.

Variants that affect how a drug is metabolised, either to produce its active form, or for excretion: An example of this is seen with tamoxifen, a drug used to treat estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Tamoxifen itself is inactive and needs to be metabolised by the P450 2D6 enzyme (encoded by the gene CYP2D6) to its active forms. However, a considerable portion of the population (up to 23% of Caucasians) carry a variation in CYP2D6 that reduces the activity of P450 2D6; this prevents the mutation carriers from gaining full therapeutic benefits from tamoxifen.

Variants that affect drug transport: For example, the statins (a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs) are normally transported out of the bloodstream to the liver by a protein called OATP1B1, encoded by the gene SLCO1B1. However, a particular variant in SLCO1B1 leads to reduced function of the transporter, leading to increased levels of drug in the bloodstream. This variant has been linked to an increased risk of simvastatin-induced muscle toxicity, an unfavourable side effect associated with many statins.

The study of how genes affect drug response is known as pharmacogenetics. However, despite the fact that our understanding of why individuals react to drugs differently has greatly expanded since the term was first coined in 1959, more work remains to be done. A small but significant portion of adverse drug reactions are idiosyncratic, meaning they are difficult to predict based on previous knowledge of how a drug works, but can have grave health consequences. Furthermore, programs for developing new drugs are costly, and are typically plagued by high attrition rates, with inadequate efficacy or safety being leading causes. Thus, more study on what controls individual drug response can improve treatment for patients and help to develop new items for the pharmaceutical toolkit.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae SEM by Mogana Das Murtey and Patchamuthu Ramasamy. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae SEM by Mogana Das Murtey and Patchamuthu Ramasamy. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Help in addressing these issues can come from a surprising source—the single-celled baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. While initially yeast and humans may not appear to have much in common, S. cerevisiae has been extensively used in biomedical research, producing findings that can be translated to humans. It has thus been established as a model organism (alongside higher systems, such as nematode worms, fruit flies, and mice, among others) for helping to understand biological processes that are not as easy to investigate in humans. About a third of yeast genes have homologous human disease-related genes and the basic internal structure and function of the cell is conserved between yeast and humans. Furthermore, different strains of yeast have been reported to contain similar levels of genetic variation to human individuals, and can thus be used as a proxy for human individuals in studies of drug response.

What makes yeast particularly attractive as a model organism is how extremely easy it is to work with. It is non-hazardous, does not require highly specialised growth conditions, and produces a new generation approximately every one and a half hours. An experiment that may take months to execute in mice can be performed in yeast in a matter of days. Furthermore, it’s very simple to work with very large yeast populations; studying millions to billions of individual organisms requires no more than a few test tubes and several millilitres of media. Such large populations are key in order to get sufficient power when looking for associations between particular genetic variants and drug response; human studies at only a fraction of the power would require a significant organisational effort, in terms of gathering volunteers, obtaining ethics approval and collecting and testing genetic samples. Finally, the small genome of yeast (only 0.4% the size of the human genome) makes it very cheap and straight-forward to carry out genome-wide sequencing, particularly with the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies.

We are still not at the point where a person can be given a medication that is assured to have a desired outcome and not give unwanted side effects. Genetic analysis can help to identify individuals that might be at risk of severe adverse reactions, or treatment failure, and having a comprehensive knowledge of genetic factors that can affect individual drug response is key for providing better treatment. This knowledge can be difficult to gather through human trials, but model organisms such as yeast are important for guiding this line of research. Findings from yeast can be tested in humans and can form the basis of improving healthcare and producing better and more effective pharmaceuticals for the future.

Featured article credit: Baker’s Yeast by Zappys Technology Solutions. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What can baker’s yeast tell us about drug response? appeared first on OUPblog.

The steeples of Essex and Tyrone: Irish historians and Brexit

One of the glib accusations levelled against Irish history is that it never changes–that its fundamental themes are immutable. Equally, one of the common accusations against Irish historians is that (despite decades of learned endeavour) they have utterly failed to shift popular readings of the island’s past. Yes, the Good Friday Agreement and its St Andrews successor have brought shared institutions and some eye-catching ecumenical gestures; but these (so the argument goes) scarcely conceal recidivist political attitudes and behaviour. The wealth of–especially “revisionist”–historical writing (it is also alleged) has scarcely impacted upon the immutable historical sympathies of the Irish people.

And yet the recent centenary commemorations of Irish Home Rule, the First World War, the 1916 Rising and Irish independence have all encouraged a wider and deeper reflection on the making of modern Ireland which in turn has produced some startling results. Historians, through their writings and other forms of public engagement, have been central to these conversations and their outcomes. The First World War, for most of the 20th century a cultural frontier between unionism and nationalism in Ireland, has become a focus for shared commemoration and reflection — thanks in large part to a huge body of work on the all-Ireland nature of popular recruitment, engagement and sacrifice. In terms of the centenary of Home Rule, the importance of the Irish unionist leader of 1912-14, Sir Edward Carson, is now increasingly recognised throughout Ireland: though his London home was denied an iconic blue plaque by English Heritage, his Dublin birthplace was successfully defended by An Taisce (the Irish National Trust), and has latterly received a “brown plaque” from the city authorities. Absent from the recent political iconography of Britain and Northern Ireland, Carson (and his rival, John Redmond) feature on a 60 cent stamp issued by An Post, the Irish state’s postal service.

Above all, the 1916 Rising has been anatomised with precision by historians, and has been publicly approached in ways which would have been virtually unimaginable in the recent past. In 1966, at the time of the fiftieth anniversary of the rising, commemoration focused upon the survivors of the rising, upon military display, and (in terms of its leaders) upon the role and teachings of Patrick Pearse. By way of contrast the commemoration of 1916 in 2016 has emphasised the contribution of women to the rising, and the role of the great labour leader, James Connolly: it has looked, not just to the martyrs who died for Ireland’s freedom, but to the casualties among the crown forces and those – often children – who were caught in the murderous crossfire of Easter week.

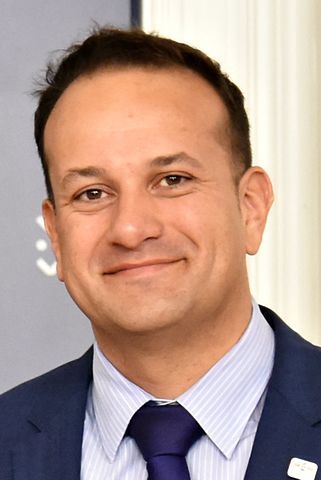

Where does Brexit now leave Ireland in this decade of commemoration? Given the continuing fluidity and opaqueness of debate, this is a tough question to answer – but (again) historians can supply context and illumination. The election as Fine Gael leader and Taoiseach of Leo Varadkar, a gay man whose paternal heritage is Indian, is widely seen as underlining Irish openness and inclusivity in the context of a range of populist and nativist pressures across the rest of Europe and North America. Varadkar’s elevation would have been unimaginable as recently as the 1980s or even 1990s, when the shadow of Ireland’s (generally rather conservative) revolutionary generation remained largely in place. Historic national aspirations remain, however: Varadkar and the Irish department of foreign affairs have flirted with the idea that after Brexit the Irish sea (rather than the meandering and complex land border in Ireland) might come to function as a frontier for some economic and immigration purposes. While unionists have been outraged, there are certainly historic precedents for some denouement of this kind, essayed during and after the Second World War.

Image credit: Leo Varadkar. Photo by EU2016 SK (HANDSHAKE 2016-07-14). CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Leo Varadkar. Photo by EU2016 SK (HANDSHAKE 2016-07-14). CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.Will Brexit ultimately disappoint those unionists who offered support? Brexit will doubtless end CAP payments, and possibly (following the reported thinking within Michael Gove’s circle) spell the end of all forms of agricultural subsidy in the United Kingdom. It may well result in the supersession of Brussels red tape with that spooled out by London and Belfast. But these are outcomes which have evidently not been fully embraced by the many unionist farmers who, angered by heavy bureaucracy and light prices, repudiated Brussels. How, on the other hand, will the significant minority of unionist remainers react to the advent of a hard (or indeed any other form of unpalatable) Brexit? Will these unionists, whose historic arguments have focused not only upon identity, but upon economics and religious faith, now reconsider their relationship with a culturally more open, secularising and (certainly for the moment) prosperous Irish state?

These of course are still heterodox thoughts requiring some leap of imagination and counter-intuition. But the DUP’s effort to strike a deal with Theresa May’s minority Tory and Brexit government, while certainly refocusing attention on immovably illiberal elements within unionism, has also stimulated some serious historical reflection on how far it has travelled since the 1970s, and (despite its rhetoric) is travelling still. The DUP for long refused to sit in the same television studios as representatives from Sinn Féin (while simultaneously collaborating with the latter at local council level): the party has been in office with Sinn Féin since 2007, and in March 2017 Arlene Foster, its current leader, attended the funeral mass of Martin McGuinness, her former ministerial colleague and sometime senior officer of the Provisional IRA in Derry city. The DUP, which once (in 1977) sought to “save Ulster from sodomy,” is now openly divided over Gay Pride, with younger and more secular elements challenging the ebbing influence of an older and religiously more fundamentalist generation.

Churchill said in 1922, in a now well-worn quip, that “the whole map of Europe has been changed … but as the deluge subsides and the waters fall short we see the dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone emerging once again”. In recent years, the whole map of Europe, and of the United Kingdom, has changed again; and historians in both Ireland and Britain have a central part to play in deciphering and illuminating this fresh and continuing design. But the subsiding waters now reveal a very different architectural configuration in Fermanagh, Tyrone and the rest of Ireland than hitherto. And in some ways it is now the “steeples” of Brexit hotspots like Essex and Lincolnshire which are emerging from the deluge of nearly half a century of EU membership, with local apprehensions and aspirations and pride unscathed.

Featured image credit: The shell of the G.P.O. on Sackville Street (later O’Connell Street), Dublin in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. Photo by Keogh Brothers Ltd. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post The steeples of Essex and Tyrone: Irish historians and Brexit appeared first on OUPblog.

Gottschalk: a ninth-century heretic, dissenter, and religious outlaw

“Just as a dog returns to its own vomit, so a fool reverts to his folly” (Proverbs 26:11). Thus did medieval church officials condemn unrepentant heretics and those who recanted, but later allegedly returned to their crimes. The typical punishment — burning at the stake — purged the offenders’ pollution from the church. This familiar image of burning heretics shapes today’s popular and scholarly perspectives of the European Middle Ages. Perhaps surprisingly, this practice was unknown in the early medieval West. In the eighth and ninth centuries, authorities of the Carolingian Empire didn’t hesitate to decapitate, blind, or mutilate political traitors and apostates to the Christian faith. Yet the realm executed no heretics. In fact, the empire produced little heresy whatsoever. Ecclesiastical officials certainly worked to eliminate sin’s polluting and corrupting powers, but they largely saw the problem of heresy as an evil defeated by the ancient church, or one posed by foreign Christians. Carolingian rulers, bishops, and intellectuals took it upon themselves to condemn ancient heresies and to combat foreign ones in their writings and synods. By contrast, native incidents of heresy or heresy accusations were few in number, isolated, and quickly resolved. Instead of battling local heresies, imperial authorities focused their energies on a process of correction and moral improvement for all baptized subjects. Maintaining spiritual purity in this way enabled the empire to retain the heavenly favor that insured prosperity in this world and salvation in the next.

This state of affairs was sorely tested by Gottschalk of Orbais — who was not a figure of lore or a foreigner, but an impenitent, homegrown Carolingian heretic. Born sometime in the later years of Emperor Charlemagne’s reign (768-814 CE), Gottschalk died in the late 860s after the emperor’s grandsons had fought a bloody civil war and carved up the realm. Gottschalk didn’t start out a heretic, but from an early age he had a talent for cultivating enemies. As a young monk, he brought a lawsuit against his abbot, Hrabanus Maurus, claiming the abbot had forced him in his youth to take his vows and violently tonsured him. The case went before a church council in 829, a year when Carolingian bishops were aiming to correct sins among the clergy. Remarkably, Gottschalk won. The ruling suggests that the bishops thought Hrabanus had abused his office by forcing Gottschalk to become a monk, a misuse of power that could endanger the realm’s spiritual health. The trial’s outcome was a public humiliation for Hrabanus, who countered that the monk’s lawsuit amounted to an anti-monastic heresy. Church authorities, however, did not agree and their ruling stood. Gottschalk was released from the cloister and from Hrabanus’s power. The abbot did not forget. He remained Gottschalk’s inveterate enemy.

Monastery of Hautvillers by October Ends. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Monastery of Hautvillers by October Ends. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In the subsequent decades, Gottschalk stirred up additional controversy. After his ordination, he began preaching something startling, even terrifying: “Christ did not die for all baptized Christians.” Flouting episcopal authority and ecclesiastical discipline, he aggressively debated with bishops and demanded they accept his teaching that divine grace separated the elect from the reprobate not only in the afterlife, but also in this world. Gottschalk claimed Christ recognized the members of his “body” on earth — his true servants — while all others belonged to Antichrist.

According to Gottschalk, only reprobate Christians would reject this teaching. His theology was drawn from a long-forgotten doctrine of the church father Augustine, whose ideas about grace had been moderated in Gaul centuries before. Nonetheless, Gottschalk’s version sounded to many bishops like a horrifying novelty of his own. It contravened Carolingian claims to divine favor in an era of rebellion and civil war, drawing believers away from traditional Frankish religious teachings. In other words, it sounded like heresy.

By a strange twist of fate, Hrabanus later became archbishop of Mainz and oversaw Gottschalk’s initial prosecution and conviction for heresy in 848. The condemned man was publicly scourged and soon imprisoned. Yet Gottschalk was not done. He claimed that he stirred up scandal not for vanity’s sake, but for the truth’s. Likewise, he prayed to be allowed to prove his doctrine in a deadly ordeal modeled after an ancient martyr tale: he would climb in and out of barrels of boiling water, oil, lard, and pitch only to emerge miraculously unscathed thanks to divine protection. The bishops would be revealed as reprobate heretics, not him. While ordeals were accepted ways of establishing criminal guilt or innocence in the Carolingian Empire, Gottschalk’s claims that a miraculous event would prove his orthodoxy were unprecedented. Suffice it to say that the ordeal — seen as further evidence of his heretical vanity and madness — was never permitted. Instead, Gottschalk remained incarcerated for the next two decades in a monastic prison.

Though later medieval authorities would likely have executed a heretic as defiant as Gottschalk, their earlier Carolingian counterparts instead disciplined him as a disobedient and insolent subordinate. He was stripped of his status as a priest, excommunicated, sentenced to perpetual silence, and quarantined in a monastery’s stronghouse in order to keep his contagious religious errors from spreading. The goal was to make Gottschalk repent and recant. These coercive reform tactics failed.

Gottschalk quickly scorned his superiors’ efforts, casting himself as a persecuted martyr from his cell. Young monks were soon smuggling his clandestine pamphlets out of prison to a subterranean community of supporters who fomented more religious controversy, while bishops and intellectuals anxiously bickered over a theological response to his teachings. Remaining an unrepentant heretic to the last, Gottschalk — the Carolingian Empire’s greatest religious outlaw — died in prison after years of scandal. Despite his excommunication, his underground supporters afterwards prayed for his soul on the anniversary of his death, 30 October.

Featured image credit: Image courtesy of Stuttgart, Wuerttembergische Landesbibliothek, Cod. bibl. fol. 23, f. 76v (detail). Used with permission.

The post Gottschalk: a ninth-century heretic, dissenter, and religious outlaw appeared first on OUPblog.

August 22, 2017

Is advocating suicide a crime under the First Amendment?

Two different cases raising similar issues about advocating suicide may shape US policy for years to come. In Massachusetts, Michelle Carter was sentenced to two and a half years in prison for urging her friend Conrad Roy not to abandon his plan to kill himself by inhaling carbon monoxide: “Get back in that car!” she texted, and he did. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court has already ruled that prosecuting her for involuntary manslaughter was permissible, even though she was not on the scene. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court was careful to insist that its holding did not criminalize assisting the suicide of a person with a terminal illness:

It is important to articulate what this case is not about. It is not about a person seeking to ameliorate the anguish of someone coping with a terminal illness and questioning the value of life. Nor is it about a person offering support, comfort and even assistance to a mature adult who, confronted with such circumstances, has decided to end his or her life.

And now the case of Final Exit v. Minnesota is before the Supreme Court, with Final Exit asking the Supreme Court to take the case and overturn its conviction for assisting the suicide of Doreen Dunn on First Amendment grounds. Notably, no individual was convicted in that case: the medical director was given use immunity to testify against the organization, which was found guilty of the crime, and was fined $30,000.

Final Exit was convicted under an interpretation of the assisted suicide law first outlined in a different case, Minnesota v. Melchert-Dinkel. In that case, the Minnesota Supreme Court held that “advising” or “encouraging” an individual to commit suicide was protected First Amendment activity, but “assisting” suicide, including “enabling” suicide by instructing a specific person how to do it, could be criminalized. Mr. Melchert-Dinkel struck a deal with prosecutors, and therefore never appealed his conviction.

Both the Carter case and the Final Exit case involve the issue of the limits of criminalizing speech.

Final Exit has asked the Supreme Court whether Minnesota’s criminal prohibition of speech that “enables” a suicide violates the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has not yet decided whether to accept the case.

Both the Carter case and the Final Exit case involve the issue of the limits of criminalizing speech, and in both cases, the defendants foresaw and even intended that the people with whom they were communicating would die. There are several noteworthy distinctions between the two cases. In the first place, Conrad Roy’s competence to make the decision to die was (at least on the face of the court decisions) far more questionable than that of Ms. Dunn in Minnesota. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court put great emphasis on his vulnerability and fragility. Relatedly, and crucially, Conrad Roy was wavering, and Michelle Carter put her thumb—indeed, her entire fist—on the pro-suicide scale. First amendment purists might say this makes no difference, and indeed criminalizing her speech constitutes viewpoint discrimination, the worst kind of First Amendment violation. Criminal lawyers, on the other hand, might argue that Roy’s ambivalence provides support for the contention that Ms. Carter caused his suicide. Final Exit argues that they did not coerce or pressure Ms. Deen; they provided information and comfort and support, but not persuasion.

Promoting the agency of competent individuals is good, even if they make decisions that we would not make.

Whether suicide or assisted suicide, this issue is not only about speech, but also fundamentally about individual agency. Promoting the agency of competent individuals is good, even if they make decisions that we would not make. Overriding a person’s will, whether by keeping him or her tethered to a life-support machine or haranguing him to get back in the car and die, is different from assisting him or her to implement a decision made thoughtfully and carefully.

Given Justice Gorsuch’s interest in and familiarity with the assisted suicide, and his announcement of his perspective through books and articles, it will be interesting to see whether the Court accepts the Final Exit case. Michelle Carter’s lawyers have promised to appeal on the issue of whether her texts and communications with Conrad Roy constituted protected speech, although the 2016 Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decision appears to have largely foreclosed that avenue of appeal. As more states legalize assisted suicide, this issue will continue to recur, and these early rulings have the potential to shape policy around the country.

Featured image credit: Lady Justice by jessica45. CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post Is advocating suicide a crime under the First Amendment? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers