Oxford University Press's Blog, page 335

August 15, 2017

A prison without walls? The Mettray reformatory

The Mettray reformatory was founded in 1839, some ten kilometres from Tours in the quiet countryside of the Loire Valley. Over almost a hundred years the reformatory imprisoned juvenile delinquent boys aged 7 to 21, particularly from Paris. It quickly became a model imitated by dozens of institutions across the Continent, in Britain and beyond. Mettray’s most celebrated inmate, gay thief Jean Genet depicts it in his influential novel Miracle of the Rose [1946] and it also features at the climax of philosopher Michel Foucault’s history of modern imprisonment, Discipline and Punish [1975]. The boys worked nine-hour days in the institution’s workshops – making brushes and other basic household implements; they dug its fields and broke stones in its quarries. Such labour was thought conducive to moral reform but it also enabled the institution – which was run by a profit-making private company – to balance its books. In his seventies, Jean Genet suspected that the reformatory was doing rather more than this: making then concealing huge profits from its forced labour. He set about, with a small team of helpers, trying to prove this by plundering the institution’s archives as well as reading widely in the historical sources. The result, The Language of the Wall, was a script for a three-part historical documentary drama for television which retells the story of Mettray from its foundation to its closure as a prison in 1937. Genet could find no hard evidence of profiteering but he dramatizes his own search for it in the script and retells the life of the institution over the hundred years by intertwining often violent incidents from the daily lives of prisoners with scenes from the corridors of power to show how closely the private institution worked alongside the state and how it survived successive changes of regime.

My return to Mettray’s archives in Tours was guided by Genet’s still unpublished script, versions of which are held at the regional archives in Tours and at IMEC. Although Genet rightly ridicules him for his reactionary politics, it is difficult not to admire the technical accomplishment of Mettray’s principal founder, the devout Frédéric-Auguste Demetz. Demetz had been sent to the United States by the French government with prison architect Abel Blouet in 1836 to follow up Alexis de Tocqueville’s earlier visit, the official purpose of which had been to investigate American prisons. Demetz and Blouet were to obtain more precise technical information about them, including detailed drawings.

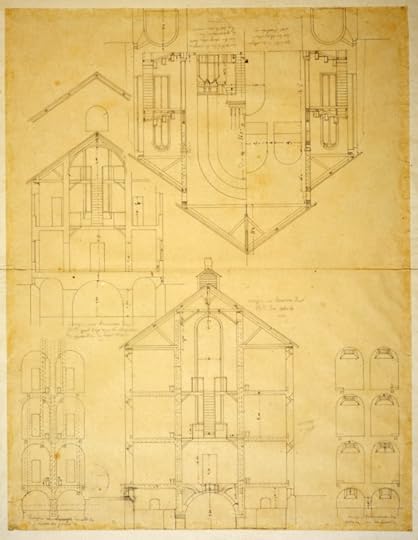

Abel Blouet, Maison Paternelle et Chapelle de la Colonie plan élévation, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J173

Abel Blouet, Maison Paternelle et Chapelle de la Colonie plan élévation, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J173Blouet subsequently produced drawings for Mettray’s chapel building which show cells in the crypt, as well as in the building behind, a unit which the institution ran as a money-making enterprise by encouraging middle-class families to send wayward sons for a short spell of ‘paternal correction’, during which they experienced individual tuition and could also hear Mass in the adjacent chapel from the privacy of their cells without having to mix with the working-class delinquents in the chapel. Demetz was a brilliant publicist for his institution, marketing it and carefully managing its visibility to the outside world. He boasted that Mettray was ‘sans grilles ni murailles’ (without bars or walls) and in one sense this was true: there was no perimeter wall, yet in addition to the punishment cells concealed in the chapel and elsewhere there were frequent roll-calls and escapees were rounded up by the local peasantry, alerted by the ringing of the chapel bell, and incentivized by the payment of a reward. Sometimes they killed escapees. Demetz welcomed philanthropic tourists but only on Sundays, when they witnessed the institution’s weekly military parade, La Revue du Dimanche.

The institution provided a hotel and even postcards for visitors to spread the news of its success in taking wayward criminal children and remoulding them into disciplined servants of the established order: inmates could leave Mettray a few years early if they joined the armed forces so many did, becoming troops in the colonial armies. Genet’s script is accurate in showing the presence of soldiers from Mettray at key moments in the colonisation of Algeria, as well as in Mexico and Indochina. Demetz was an expert carceral entrepreneur who not only governed the prison but also the surrounding local population, enlisting them as – in effect – auxiliary prison guards to substitute for the absent perimenter wall. In Paris he garnered financial support from the governing classes in a similar way. By capitalising on the fear of crime to further his own institutional agenda, Demetz’s approach points forward to the ubiquitous work of today’s ‘(in)security professionals’, to use Didier Bigo’s suggestive formulation.

The post A prison without walls? The Mettray reformatory appeared first on OUPblog.

Cosmic ripples

Michael Faraday transformed our understanding of the physical world when he realised that electromagnetic forces are carried by a field permeating the whole of space. This idea was formalized by James Clerk-Maxwell who constructed a unified theory of electromagnetism in which beams of light are undulations in the electromagnetic field. Maxwell’s theory implies that visible light is just one part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Heinrich Hertz confirmed this experimentally in 1887 by generating and detecting radio waves. The invention of radio followed, along with television, radar, mobile phones, and many other applications. Electromagnetic waves are emitted whenever electrically charged objects, such as electrons, are shaken.

The gravitational field

When Einstein formulated his new theory of gravity – general relativity – he aimed to explain gravity as a theory of fields. In this he was successful. Remarkably, it turned out the appropriate field is spacetime itself.

In general relativity, spacetime is analogous to the electromagnetic field and mass is analogous to electric charge. One implication of the theory is that vigorously whirling large masses around will generate gravitational waves, and as gravity is described as the warping and curvature of spacetime, these gravitational waves are simply ripples in the fabric of space.

Schematic illustration of a binary black hole system generating gravitational waves. Copyright: Nicholas Mee. Used with permission.

Schematic illustration of a binary black hole system generating gravitational waves. Copyright: Nicholas Mee. Used with permission.Detecting electromagnetic waves is easy. We do it whenever we open our eyes, turn on the television, use Wifi, or heat a cup of tea in a microwave oven. Detecting gravitational waves is rather more difficult, because gravity is incredibly weak compared to the electromagnetic force.

We live in an environment where gravity is very important and this gives a false impression of its strength. But it takes a planet-sized amount of matter pulling together for gravity to have a significant effect, and even then it is easy to pick up metal objects with a small magnet, defying the gravitational attraction of the entire Earth.

Gravity is so weak that even shaking huge masses generates barely the tiniest gravitational ripple. Only the most violent cosmic events produce waves that could conceivably be detected, these include supernova explosions, neutron star collisions and black hole mergers. Any instrument sensitive enough to detect them must measure changes in distance between two points several kilometres apart by less than one thousandth of the diameter of a proton. Incredibly, such instruments now exist.

Detecting the ripples

In the centenary year of Einstein’s general relativity, researchers achieved their first success. It had taken decades to develop the technology to build LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) consisting of two facilities 3000 km apart in the United States, at Hanford, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana. (Two well-separated detectors are required to distinguish true gravitational wave events from the inevitable local background disturbances.)

The facilities are L-shaped with two perpendicular 4 km arms housed within an ultrahigh vacuum. A laser is directed at a beam-splitter sending half the beam down each arm. The light travels 1,600 km, bouncing back and forth 400 times between two mirrors in each arm, before the two half-beams are recombined. The apparatus is designed so that the recombined half-beams completely cancel, with the peaks in the light waves of one beam meeting the troughs in the other, and no light passes to the photodetector. Whenever a passing gravitational wave ripples through the apparatus, however, the lengths of the arms alter very slightly, so the distances travelled by the half-beams changes and their phases shift (by much less than a single wavelength). There is no longer perfect cancellation and some light arrives at the photodetector. The sensitivity of LIGO is extraordinary, as it must be if there is any chance of detecting gravitational waves.

Extreme violence in the depths of space

The upgraded LIGO programme was scheduled to begin on 18 September 2015. Four days before the official start something wonderful happened. An unmistakable and identical signal was measured by the detectors in Hanford and Livingston within a few milliseconds of each other.

The first ever gravitational wave signal detected by the LIGO observatories. Still taken from a video recording the sound of two black holes colliding. Public domain via Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab.

The first ever gravitational wave signal detected by the LIGO observatories. Still taken from a video recording the sound of two black holes colliding. Public domain via Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab.Researchers have studied computer models of black hole mergers and other violent cosmic processes so they can recognise the signatures of events detected by LIGO. According to the models, binary black holes produce a continuous stream of gravitational waves that drains energy from the binary system and the black holes gradually spiral together. In the final moments of inspiral the amplitude of the waves increases dramatically. Initially, the newly merged black hole is rather asymmetrical, but it rapidly settles down with a final blast of gravitational waves known as the ring-down.

Much information has been extracted from the brief signal detected by LIGO. It came from an event 1.3 billion light years away that was detonated by two merging black holes during their final inspiral and ring-down. The masses of the black holes are deduced to be 29 and 36 solar masses, and they coalesced into a rapidly spinning black hole of 62 solar masses. What is truly staggering is that during the merger process three times the mass of the sun was converted into pure energy in the form of gravitational waves.

This was the first ever detection of a binary black hole system and the most direct observation of black holes ever made. It also confirmed that gravitational waves travel at the speed of light, as expected.

The difference in arrival time at the two observatories indicates the direction towards the event, at least roughly. When further gravitational wave observatories come on line around the world, this will allow more precise determinations of the sources of gravitational waves.

GOTO Observatory

Earlier this month a new wide-field telescope was inaugurated on the Roque de Los Muchachos high above La Palma in the Canary Islands. It is known as the Gravitational-wave Optical Transient Observer (GOTO) and will seek the source of any gravitational waves detected by LIGO, providing further valuable insights into their origin.

Since 2015, two more signals have been detected by LIGO. Both are due to black hole mergers. The era of gravitational wave astronomy has begun.

A version of this post originally appeared on Quantum Waves Publishing.

Featured image credit: Binary Star, artist’s conception by NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Cosmic ripples appeared first on OUPblog.

10 facts about the Indian economy

15 August 2017 marks the 70th year anniversary since the British withdrew their colonial rule over India, leaving it to be one of the first countries to gain independence. Since then it has become the sixth largest economy in the world and is categorised as one of the major G20 economies. India is seen as a newly industrialised country and was the world’s fastest growing major economy in 2014. With a population of 1.2 billion and the second largest in the world, its economy has a lot to offer and has evolved over the years.

To mark the occasion we have compiled a wide array of facts around the Indian economy pre and post-independence.

1. India’s economy can be considered a paradoxical one. Despite being one of the fastest growing economies in the world, around one-third of the population live below the poverty line.

2. Before the age of European colonization, India accounted for about 25% of the world’s manufactured goods. In the 13th century, India emerged with a great trading capacity and was able to achieve a state of economic dominance within the wider Indian Ocean world. The main manufacture was cotton textiles which were being produced in all parts of the country for both domestic and export trade.

3. The East India Company was formed in Britain to pursue trade within the East Indies and Southeast Asia. Instead, it mainly did most of its trade within the Indian subcontinent and China. Some of the most popular items of trade were tea, silk, cotton, and opium.

4. India is one of the BRIC countries as its economy experienced fast growth in the 2000s and is predicted to surpass many of the world’s largest economies by 2050. It shares this place along with Brazil, Russia, and China.

5. India is well-known as the home of spices and is the world’s largest producer and exporter of spices. It also accounts for half of the trading in spices globally.

Curry spices Indian cinnamon by PDPics. Public domain via Pixabay.

Curry spices Indian cinnamon by PDPics. Public domain via Pixabay.6. The rupee is the currency of India and it has its amount written in 17 of the Indian languages. It is also the currency of the Maldives, Mauritius, Nepal, Pakistan, Seychelles, and Sri Lanka.

7. The agricultural economy in India during the 1930s was greatly impacted by the Great Depression. It affected some of the most popular export staples ranging from jute, tea, and cotton.

8. In November 2016, Narendara Modi, the current Prime Minster of India announced that all 500 and, 1,00 rupee notes will be demonetised in order to tackle illicit cash handling and illegal activity.

9. India is a major exporter of IT and software services and this sector is considered to be one of the fastest growing within the economy. Its net IT exports grew from virtually nothing in 1990 to around $70 billion two decades later.

10. 58% of the rural households in India depend on agriculture as their main source of income and is one of the largest contributors to India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Featured image credit: ancient antique army art by Pexels. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post 10 facts about the Indian economy appeared first on OUPblog.

Do your job, part 1

In The Beat Stops Here, there is a chapter devoted to expectations, from and of both the ensemble and the conductor, of each other and of themselves. Built around a worksheet entitled “Orchestral Bill of Rights and Responsibilities,” I attempt therein to design a framework for a long overdue discussion to occur, about what our actual jobs are, how we perceive them and how our neighbors in the orchestral community perceive them, divisions of labor, and what we have the “right to expect” from each other. That noted, it is time to take the next step, a step prompted, for me at least, by a situation in which every assumption I have made about orchestral playing has been challenged.

I am working presently with an orchestra in China, a group of fine players individually, whose expectation of me is totally different from anything I have experienced up to now, even after some 35 years on the podium. In this situation, the orchestra is performing a work they have never done from a set of new, unmarked, unbowed parts. The tradition of the orchestra is that they do not prepare in any form for the first reading; they do not listen to the work, they literally sightread their parts at the first rehearsal. Their basic concept of rehearsal differs from mine; for this ensemble, “rehearsal” is repeating a passage over and over again, slowly, then more quickly, until it is “learned.”

Expressing surprise and some dismay over the state of the parts and the bowings (or lack thereof), I dove in to the first reading following my usual method, go through the work and then start rehearsing. It soon became obvious that the orchestra had no idea how the piece went (Falla’s Three-Cornered Hat ballet, complete), and they expected me to stop every time a tempo or meter changed and explain what I was going to beat in and what the tempo would be. I suggested, gently at first, then more forcefully, that I wasn’t going to work that way; that the language of my conducting, assuming people were looking at all, would readily be apparent if they just looked up. This assumption was faulty, as it did not take into account the 2nd of one of TBSH’s immutable 3-part truths: “If the orchestra doesn’t know the piece, it doesn’t make any difference where you put your hands.”

Furthermore, this orchestra was unusually vocal about what they expected of me. The question, “How can we play if we don’t know what you are beating in?,” came up, from a principal wind player. And it was not posed politely, I might add. I demonstrated (a bit snarkily, I confess) what 1, 2, and 3 patterns looked like, and said, “This is what conducting IS. Just look at it.”

That didn’t go over well. The response was, “Well, we are just sight reading it for the first time!” Worse. My response, “Why? What would you think of me if I came into the first rehearsal sight-reading the score?” And worse. The remainder of the first rehearsal was, well, chilly. My assistant urged me to reconsider my choice not to tell the orchestra what I was going to “beat” in, and I said no. To have done so would have violated my core beliefs about what my job is, what the orchestra’s job is, and what conducting is.

Later on, in a relatively simple passage, the strings were not together at all. I said “Let’s play together, please.” The concertmaster responded, “Maestro, this is our first time seeing the piece,” and I said, testily (by this point, I was frankly ticked), “I don’t see how that is my problem.” The rules of orchestra playing don’t change – looking, listening to the person next to you, communicating with the principal stands, keeping in touch with the conductor. UNLESS. Unless the “rules” are broken from the outset; unless the “rules” never existed in the first place, which clearly they didn’t here.

Ah. They weren’t breaking any rules; the rules with which I am familiar, under which I function, literally never existed here.

What to do? How can we move forward with mutual respect and purpose? How will we resolve the impasse?

The saga is not over, it is playing out day to day. I am happy to report that yesterday went much better; we will see what today holds. But I leave it to the reader to consider the scenario offered above; it is neither hypothetical nor theoretical, it is part of the here and now. It is a situation that every conductor may face (or have faced). How will you respond? How have you dealt with it?

Part 2 of “DO YOUR JOB” is shortly forthcoming, as soon as I figure out how “art” emerges from our process this week. In the meantime, consider the scenario and ask yourself, “What would I do? What is my job under these circumstances? How and where do we find “art” under these conditions.”

Back to work.

The post Do your job, part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

The power of vision in the age of climate change

Helen Keller once said, “The only thing worse than being blind is having sight but no vision.” The sustainability revolution is unstoppable. Signs are everywhere; policy makers and the private sector are veering towards a decarbonized development model. The adoption of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change on December 2015 marked the political turning point. This moment was only possible, however, due to the previous surge in momentum from non-state and sub-national actors.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of the Paris Agreement is that all 197 Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) agreed to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit this increase to 1.5°C. As a long-term goal, Parties also agreed to reach global peaking of greenhouse gases (GHG) as soon as possible, and to undertake rapid reductions afterwards so as to achieve a balance between the level of emissions and of removals by sinks (zero net emissions) by the second half of this century. The biggest change brought by the Agreement to the UNFCCC regime, is that all Parties must pursue mitigation efforts – not only developed countries.

Parties were also aware of the fact that some climate change impacts are already inevitable. With this in mind they agreed to increase the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change, and foster resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development. Importantly, they agreed to make finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development. The Paris Agreement also mandates Parties to strengthen capacities and transfer technology of those Parties in need, so that they, in turn, can also lower GHG emissions and adapt to climate change.

The provisions of the Paris Agreement are however not enough to achieve the desired goal of 1.5°C temperature increase by the end of this century. This is so because the pledges presented by the Parties to the UNFCCC in their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) for the years 2020 to 2025/2030 are not ambitious enough to reach the goal (under the Agreement, Parties are free to determine the nature and extent of their pledge).

“U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry participates in the event on the UN Paris Agreement Entry into Force at the United Nations” by U.S. Department of State. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry participates in the event on the UN Paris Agreement Entry into Force at the United Nations” by U.S. Department of State. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Paris Agreement also follows a more managerial and procedural approach. This is, it sets strong transparency obligations on Parties to present their national inventories of GHG and the information needed to track progress in the implementation of their pledges under a transparency mechanism. This transparency mechanism is accompanied by two additional mechanisms: a mechanism to facilitate and promote compliance, and a global stocktake. The global stocktake mechanism is a review and ratchet process where Parties review all pledges every five years, assess the progress towards achieving the purpose and long-term goals of the Agreement, and then set more ambitious ones. Unfortunately, waiting for this procedural machinery to start working and for the results of the next global stocktake in 2023 before increasing ambition would be too late.

According to the latest scientific research, in order to achieve the objective of maintaining the increase in average global temperature at below 2°C by the end of the century (least to say 1.5°C), GHG emissions should peak by 2020. According to Mission2020, convened by the former UNFCCC Secretary, Christiana Figueres, several additional milestones should be achieved by 2030 if the long-term goal of decarbonization by the end of the century is to become a reality:

Renewables should make up at least 30% of the world’s electric supply;

cities and states should be running and sufficiently funding programs to achieve the decarbonization of buildings and infrastructure;

at least 15% of all new cars sold globally should be electric, accompanied by an increase in decarbonized public transportation in cities, as well as by more fuel efficiency and less GHG emissions from aviation;

deforestation should stop, and afforestation and reforestation should increase in such a degree so as to create the necessary carbon sinks to reach net zero emissions;

heavy industry should be developing plans for halving emissions before 2050; and

the finance sector (private and public sources) should be mobilizing at least 1 trillion US dollars a year for climate action.

Surely, these milestones are challenging but also possible and desirable.

Several countries and regions are already on the vanguard, pushing for a successful transition towards a decarbonized economy. Iceland, Norway, and Costa Rica have announced their desire to become climate neutral. Bhutan goes a step further and is the only carbon negative country in the world (absorbing more greenhouse gases than it produces), with the intent of remaining so. The Gambia and Morocco’s pledges are also very ambitious.

“Windmills Renewable Energy” by epicantus. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Windmills Renewable Energy” by epicantus. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.A second group of countries has presented pledges that are acceptable, but do not contribute enough to the common effort. Their pledges have been rated as “medium” by Climate Action Tracker (which rates countries’ pledges and policies against whether they are consistent with a country’s fair share effort to holding warming to below 2°C). The most important of these (in light of their share in global emissions) are the European Union, China, Brazil, India, and Mexico. These countries and region should step up in their efforts and policies, as by doing so they have much to win.

A last group of countries has announced mitigation goals that are clearly insufficient. Among these are other big emitters such as Canada, Australia, Russia, Japan, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Ukraine, South Korea, and the United Arab Emirates. The greatest disappointment and laggard in this third group is the United States, whose current federal government has sadly chosen to follow a path in the wrong direction.

It is clear – even for those with limited vision – that the countries and private companies now betting on decarbonization will be the great winners of the future. First of all, they will provide the knowledge and technology necessary for the transformation. Secondly, they will substantially improve the living conditions of their inhabitants. And thirdly, the economically stronger of them will be the leaders of tomorrow’s global economy.

The race towards decarbonization is picking up speed. Hopefully we will be able to agree with Rudi Dornbusch who said that “things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you ever thought they could”. We must transform our economy, but most importantly, we must transform our minds. We see the world through “carbon eyeglasses” and measure all our activities according to their carbon imprint on the world. The recipe for success is simple to remember: all of us – states, regions, cities, companies, and individuals – should cut our carbon footprint in half by the end of each of the coming three decades. We can do it and the vision of a better, cleaner future will become our reality.

Featured image credit: “Climate Protest” by niekverlaan. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The power of vision in the age of climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

August 14, 2017

Last minute guide to the total solar eclipse

In exactly a week, a total eclipse will be visible, spanning along a narrow path through the United States. In readiness for the event on 21 August 2017, we asked physicist and eclipse-chaser professor Frank Close eight questions about eclipses, and how to watch them.

What is a solar eclipse?

The moon is 400 times smaller than the sun, but it’s also 400 times closer to earth, which means that remarkably, the two bodies appear to us as exactly the same size. For 14 days a month, the orbiting moon is on the ‘sunny’ side of the spinning earth, and the sunlight casts a shadow.

Almost all the time, that shadow is projected way off into space; but on very particular occasions, the shadow falls onto the earth – the moon is obscuring our view of the sun.

From the human observer’s point of view, your attention is of course on the sun, as you watch the moon slowly move in front of it.

Relative to the earth, the moon and sun are moving at slightly different speeds, which means the shadow sweeps across the earth’s surface; it passes from West to East at about 2,000 miles an hour.

Are all eclipses the same size?

No. Because the moon’s orbit around the earth is elliptical, sometimes it’s closer, sometimes it’s further away. So for each eclipse, the size of the shadow will be different.

On an occasion when the moon is very far from the earth, it will appear fractionally smaller than the sun. Rather than total, the eclipse is ‘annular’ – with a thin ring of sun visible around the moon.

How wide is the path of the eclipse?

Typically, the whole shadow will be several thousand miles across; the central area which gives ‘totality’ will usually be between ten and 100 miles across.

Watching the Solar Eclipse by Karel Fort. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Watching the Solar Eclipse by Karel Fort. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.How long does totality last?

That depends on the size of the shadow. The longest totality has been around seven minutes; most are around three, and some are shorter than that.

It also depends very much on where you are standing. The closer you are to the centre-line of the shadow’s path, the longer you will experience totality. If you are say 30 miles off-centre, you will only get a few seconds.

How often does totality occur?

Twice a year (or, in fact, twice in 355 days) some sort of solar eclipse happens somewhere on the earth’s surface. But the spectacular total eclipses happen about six times a decade – and most often in locations not easily accessible to most of us.

How long will I have to wait to see the next eclipse?

It depends how far you want to travel! Since 1999 I have seen six: Cornwall in 1999, Zambia in 2001, Sahara Desert in 2006, two in the South Pacific, and one off the Cape Verde Islands. The August 2017 in Wyoming will be my seventh.

Which cities will experience totality in 2017?

The shadow makes landfall south of Portland, Oregon, and it leaves the continent in South Carolina. Cities on the path include: Corvallis, Albany; Lebanon, Oregon; Idaho Falls, Idaho; Casper, Wyoming; Lincoln, Nebraska; St Joseph, Missouri; Kansas City, Kansas; St Louis, Missouri; Nashville, Tennessee; Greenville, South Carolina.

What safety tips would you recommend?

First, don’t walk about. It’s surprisingly easy to trip over in the strange darkness, especially when there are lots of other people around you.

Second, be absolutely certain to look away as totality finishes. During totality, you will be looking at the blackened disk that is (or is not) the sun. The sunlight returns literally in a flash, and your pupils will be wide open.

Third, watch out for wild animals! When totality falls, birds and animals behave as if it’s night-time. Birds roost, crickets chirp, night-time predators set about their business. In 2001, I was watching from the banks of the Zambezi river; fortunately, our guards were ready for the hippopotami.

Fourth, save up. Experiencing a total eclipse is the most extraordinary and wonderful sensation. You are sure to want to finance the journey to another one, another year.

Featured image credit: annular solar eclipse by Takeshi Kuboki. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Last minute guide to the total solar eclipse appeared first on OUPblog.

The Iliad and The Trojan War [excerpt]

The Iliad tells the story of Achilles’ anger, but also encompasses, within its narrow focus, the whole of the Trojan War. The title promises “a poem about Ilium” (i.e. Troy), and the poem lives up to that description. The first books recapitulate the origins and early stages of the Trojan War. The quarrel over Briseïs mirrors the original cause of the war, for it too is a fight between two men over one woman. The Catalogue of Ships in book 2 acts as a reminder of the expedition; book 3 introduces Helen and her two husbands; book 4 dramatizes how a private quarrel over a woman can become a war; in book 5 the fighting escalates; and book 6 takes us into the city of Troy. The narrative now looks forward to the time when the Achaeans will capture the city: it anticipates the end of the poem, and of the war itself. The bulk of the Iliad is devoted to the fighting on the battlefield. It describes only a few days of war, but the sheer scale of the narrative, and its relentless succession of deaths, come to represent the whole war.

The poet is specific about the horrors of the battlefield: wounds, for example, are described in precise and painful detail. At 13.567–9 Meriones pursues Adamas and stabs him “between the genitals and navel, in the place where battle-death comes most painfully to wretched mortals.” At 15.489–500 Peneleos thrusts his spear through Ilioneus’ eye-socket, then cuts off his head and brandishes it aloft. At 20.469–1 Tros tries to touch Achilles’ knees in supplication, but Achilles stabs him

. . . in the liver with his sword,

and the liver slid out of his body, and the dark blood from it

filled his lap . . .

No Hollywood version of the Iliad is as graphic as the poem itself. Descriptions of the physical impact of war are matched by an unflinching psychological account of those who fight in it. Homer shows exactly what it takes to step forward in the first line of battle, towards the spear of the enemy. He describes the adrenaline, the social conditioning, the self-delusion required. And the shame of failure, which is worse than death.

The truth and vividness of the Iliad have struck many readers. In her towering exploration of violence, Simone Weil, for example, calls the Iliad “the most flawless of mirrors,” because it shows how war “makes the human being a thing quite literally, that is, a dead body. The Iliad never tires of showing that tableau.” Weil was writing in 1939: her L’Iliade ou le poème de la force did not just describe the Trojan War; it anticipated the Second World War, and prophesied how it would again turn people into things. Just like Weil, women inside the Iliad make powerful statements against violence—and even against the courage of their own men. Hector’s wife Andromache, for example, tells him that his own prowess will kill him, and that he will make her a widow (6.431–2). When confronted with his wife’s words, Hector claims he would rather die on the battlefield than witness her suffering (6.464–5). He then tries to console her in the only way he knows: by imagining more wars. He picks up his baby son and prays that he may be stronger than him and, one day, bring home the spoils of the enemy, so that his mother may rejoice (6.476–81). This is how the poet Michael Longley, in the context of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, paraphrases Hector’s prayer: he “kissed the babbie and dandled him in his arms and | prayed that his son might grow up bloodier than him.”

The Trojan War, the Second World War, the Troubles: the Iliad is intertwined with all stories about all wars. Already in antiquity it was part of a wider tradition of poetry, which found its inspiration in the ruins of a Bronze Age city, well visible on the coast of Asia Minor. The Iliad often refers to that wider tradition. For example, when Hector picks up his baby and dandles him in his arms, his gesture recalls that of an enemy soldier who will soon pick up the little boy—and throw him off the walls of Troy. Other early poems described the death of Astyanax in a manner that clearly recalled his last meeting with his father. Some stories about the fall of Troy were known to the poet of the Iliad and his earliest audiences; others were inspired by it. As a result, the Iliad became more allusive and complex in the course of time. This is how Zachary Mason describes the situation in a recent novel inspired by Homer:

It is not widely understood that the epics attributed to Homer were in fact written by the gods before the Trojan war—these divine books are the archetypes of that war rather than its history. In fact, there have been innumerable Trojan wars, each played out according to an evolving aesthetic, each representing a fresh attempt at bringing the terror of battle into line with the lucidity of the authorial intent. Inevitably, each particular war is a distortion of its antecedent, an image in a warped hall of mirrors.

Mirrors and distorted mirrors: what readers ask of the Iliad is whether things can be different. Whether we must imagine wars and more wars, like Hector when he prays for his son, or whether there can perhaps be peace—and even a poetics of peace. This is, for example, the insistent question of the poet Peter Handke in his explorations of the cold war, clear answer, only fleeting im ages of peace in the form of distant memories, startling comparisons, and doomed aspirations. Hector runs past the place where the Trojan women used to wash their clothes before the war (22.153–9). Andromache wishes Hector had died in his own bed (24.743–5). Athena deflects an arrow like a mother brushing away a fly from her sleeping baby (4.129–33). On the shield of Achilles—which is a representation of the whole world—there is a city at war, but there is also a city at peace. There is a wedding, and the vintage, and a row of boys and girls dancing to music (18.478–608). These images are precious, because they are so very rare.

Featured image credit: “Greece” by GregMontani. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The Iliad and The Trojan War [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Barth, the Menardian

For the better part of half a century, John Barth was synonymous with what was the last self-conscious attempt at constructing a universal aesthetic movement speaking for all of humanity but recognizing only its bourgeois, white constituent. Much like Virginia Woolf once could claim that “on or about December, 1910, human character changed,” Barth would argue (with about the same dose of provincialism) that literary modernism was over.

If Woolf’s epochal declaration of modernism was a program for an exploration of human consciousness beyond European realism, the modernism of the day was something else. Now, in the late sixties, things had to change.

Barth’s exemplar of the devolution of modernism was Samuel Becket, who, Barth claimed, had “progressed from marvelously constructed English sentences through terser and terser French ones to the unsyntactical, unpunctuated prose of Comment C’est and ‘ultimately’ to wordless mimes.” Becket’s modernist ultimacy engendered only silence and exhaustion, Barth claimed. Barth’s project would therefore be one of sound … and lots of it. Instead of removing character and plot from literature, the new novelist needed to approach the question of originality in a different way. The novel ought to embrace its condition of belatedness, Barth argued, take all its “felt ultimacies” and turn them into a new criterion.

Here Jorge Luis Borges serves as Barth’s exemplar. In the story, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” Borges’ invention turns around “a Symbolist from Nîmes,” who by following a “philological fragment by Novalis—which outlines the theme of a total identification with a given author” as a preparation for translation, ends up composing several chapters of Cervantes’s novel. The result of this re-composition, Borges’ narrator tells us, is “astounding”: what “is a mere rhetorical praise of history” when coming from the seventeenth century “lay genius” Cervantes, is an argument about history as the origin of reality when coming from Menard. The quixotic has become ontological, Barth suggests, in a literary universe replete with dizzying mirrors and labyrinths, self-proclaimed precursors, and unacknowledged antecedents.

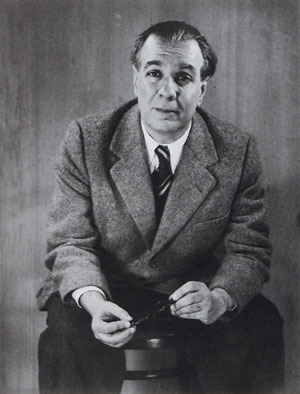

Jorge Luis Borges by Grete Stern, 1951. Public Domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.

Jorge Luis Borges by Grete Stern, 1951. Public Domain via

Wikimedia Commons

. Just as the concept of modernism wasn’t quite available to Woolf when she published Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown in 1924, postmodernism hadn’t quite established itself at the time of Barth’s reflections on The Literature of Exhaustion in 1967. But once it did, Barth became one of its poster boys, along with Joseph Heller, Donald Barthelme, Thomas Berger, Thomas Pynchon, John Hawkes, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., William Gass and Robert Coover—all male, white and provincially middle-class—just like, presumably, Borges’ Symbolist from Nîmes.

In what remained of the 60s, throughout 70s, 80s, 90s, and the first decade of the new century, Barth continued to publish novels and short-stories in this Borgesian-Menardian vein. The satirical re-invention of the eighteenth-century novel that had earned him a name in the early 60s, now gave way to more deeply philosophical explorations. At the heart of Barth’s narratives would always be a writer, who in writing in a semi-autobiographical, realistic style, would find himself literally swept away by the fictions of the past, Homer’s Odysseus, Poe’s Pym, but above all, Scheherazade’s One Thousand and One Nights. Barth’s string of Mr. Bennetts—Fenwick Turner from Sabbatical (1982), Peter Sagamore from The Tidewater Tales (1987), and Simon William Behler, of The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor (1991)—are in this sense antithetical to Woolf’s Mrs. Brown, but in a different way as her Mr. Bennett.

Whereas Woolf argues that conventional realism isn’t able to penetrate deeply enough into human sense making, and thus leaving vast parts of reality unaccounted for, Barth’s narrators, although committed to novelistic realism, lose themselves in the mirror worlds and labyrinths of the previously written and told, whether they be the mythic fictions of culture or the alternative facts and realities of the CIA.

If the novel, as it has been argued time and again, is a genre of fiction that depends on philosophical realism and what Ian Watt has called “the individual apprehension of reality,” then Barth’s novels might perhaps best be read as tours-de-force of storytelling and world building, which to boot, are philosophical arguments about how words, works, and worlds interlink and interact in the construction of our, by now, manifold and thoroughly provincialized realities. In this way, Barth’s art goes a long way in acknowledging that human consciousness doesn’t begin in the sensorium of a perceiving subject, and that it therefore cannot be the Archimedean point from which a sense of the real develops. Barth’s novels seem to suggest that fiction and fact are as related as their etymologies, and that our capacity for storytelling, therefore, cannot be exhausted or grow old. On the contrary, the ability to narrativize, this mythic capacity to imagine a center of consciousness (a hero, a subject) in the process of traversing a plot space, might be where both consciousness and history begin. Barth knows this, just as Pierre Menard knew it and maybe Borges too. Cervantes certainly did.

Barth should be celebrated as a master storyteller, passionate virtuoso, teacher, and sage, and perhaps also—hopefully—prophet and truth-teller.

Featured image credit: Cervantes Don Quixote Statue Madrid by Anher. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Barth, the Menardian appeared first on OUPblog.

Ecosystem-based mitigation and adaptation

Payments for ecosystem services (PES), also known as payments for environmental services (or benefits), are incentives offered to farmers or landowners in compensation for proper land-management that provides ecological services. Among these benefits we can mention conserving animal and plant species, protecting hydric resources, conserving natural scenery, and storing carbon.

Costa Rica is a pioneer in PES schemes. Since 1997 approximately one million hectares of forest have been part of these ‘payments for ecosystem services’ (PES) schemes at one time or another. Forest cover has returned to more than 50% of the country’s total land area (51,000 square kilometres) – a huge increase from an all-time low of 21% in 1987. This small Central American country was not only able to stop one of the highest deforestation rates world-wide, but also to reverse it and in this way preserve its fantastic biodiversity. According to a recent study by the Forest and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in 2016 forest cover amounted to 54% of the total territory.

This tremendous success was possible with the help of an innovative scheme elaborated, financed, and implemented by the Costa Rican government with the support of the Fundación para el Desarrollo de la Cordillera Volcánica Central (Fundecor). The foundation still offers today a series of services related to forest conservation, such as capacity building for forest ecosystem management, advice on sustainable forest management (both of natural forest and forest plantations), and advice on mitigation and adaptation to climate change in the forest sector.

Brazil, Ecuador, and Guatemala have also created PES schemes, financed by the government. In Brazil, 2,700 indigenous families have benefited from the Bolsa Floresta project, which pays in exchange for the preservation of primary forest. In Ecuador, the Socio-Bosque project has been able to conserve more than half a million hectares of forest, with more than 60,000 beneficiaries. Guatemala has reforested more than 95,000 hectares of land, in addition to the conservation of 155,000 hectares of natural forest.

Save Global Green by Raw Pixels. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

Save Global Green by Raw Pixels. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.More recently, PES schemes have been implemented for the conservation of agricultural and livestock landscapes. A pilot program, again in Costa Rica, has achieved a significant reduction in degraded pasture land (more than 40% recovery), an increase of more than 75% in the number pastures with tree coverage, an increase in 3.5 times the length of living fences, 22% more carbon storage, habitat creation, improved water security, and a reduction in water surface runoff. In addition to this, a program financed by the Global Environmental Fund (GEF) and carried out in Colombia, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica achieved a 60% reduction in degraded pastureland in all three countries, with a significant increase in forest coverage mixed with pastureland. The project has also contributed to a 71% increase in carbon storage, a higher milk production, and a 115% income increase of the farm owners. A well-planned and executed PES scheme provides a holistic solution to many interrelated problems. First of all, it preserves existing forests and rebuilds formerly deforested areas. This has several positive co-benefits: the forests store carbon and thus mitigate climate change, water resources are secured, beautiful countryside scenery is restored, air quality is improved, and plant and animal species are better protected. Second, it provides additional resources to land-owners in rural areas, potentially relieving social and economic problems in those regions. Thirdly, PES can also be used as a strategy for adaptation to the impacts of climate change.

Ecosystem-based adaptation (EBA) is the usage of biodiversity and ecosystemic services as part of an adaptation strategy. Some additional benefits to those mentioned above are that EBA improves risk reduction by restoring coastal habitats, establishes agricultural systems, and helps in the prevention of fires. A good EBA project should follow several basic principles: a) involve local communities, taking into consideration their way of life and specific needs; b) focus on the reduction of pressures that have degraded the ecosystem; c) develop alliances and strategies with different partners, public and private; d) take advantage of existing good practices in the management of natural resources; e) follow an adaptive approach; f) integrate the project into greater adaptation strategies; and g) communicate and educate.

Climate Change Global Warming by HypnoArt. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

Climate Change Global Warming by HypnoArt. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.One example of a EBA project is the Parque Andino de la Papa (Andean Potato Park) in Cusco, Perú. The people in the region have been able to increase the number of potato varieties (from 200 to 650). This reduces the risk of crop destruction, by using different varieties of potatoes in different microclimates. As a co-benefit, the project improves and secures genetic biodiversity. Women and local communities have also been empowered in the process.

Another interesting example is the CASCADA project, which takes place in Guatemala, Honduras, and Costa Rica. Some of its objectives are to contribute to the adaptation of small coffee producers, increase the capacities in the communities, and involve civil society in decision-makin g. CASCADA also reduces greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, such as methane and nitrous oxide set off during the coffee production process. This is done by planting trees for shade and as green barriers, as well as reducing chemical fertilisers and organic waste. The project also aims to empower the local communities and other relevant actors, forming a virtuous cycle.

The successful experiences with ecosystem-based mitigation and adaptation schemes in Latin America show that these are helpful tools in the fight against climate change. If well implemented, ecosystem-based programs can have many other additional environmental, social and economic co-benefits. They offer holistic solutions to interconnected problems and have the potential to become virtuous cycles, enabling countries and regions to achieve much with a good cost-benefit ratio. Also, by sharing their knowledge gained from these pioneer schemes, Latin American countries could also become a leading force in the fight against climate change. By providing advisory services to other countries, Latin American countries could also receive additional sources of income and in this manner, further enrich a win-win process.

Featured image credit: Rain Forest Clouds by tropa66. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Ecosystem-based mitigation and adaptation appeared first on OUPblog.

August 13, 2017

George Romero, Game of Thrones, and the zombie apocalypse

When George Romero, director of Night of the Living Dead, died on 16 July, the world was gearing up for the season opener of Game of Thrones. Game of Thrones owes its central storyline—the conflict between the Night’s Watch and the White Walkers—and a great measure of its success to Romero, as do other popular and critically-acclaimed versions of the story, whether television (The Walking Dead, iZombie), film (28 Days Later, Sean of the Dead, and Zombieland), fiction (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, The Making of Zombie Wars), comics (Marvel Zombies, Afterlife with Archie, Blackest Night), or any of the other media or products shaped by the zombie narrative. When we consider how important the Zombie Apocalypse story has become in our culture, it is hard to know whether to call George Romero a popular filmmaker, a social critic, or a prophet. Maybe he’s all three.

When Romero directed Night of the Living Dead in 1968 on a shoestring budget and with no-name actors, he and co-writer Joe Russo were simply trying to make a cheap, stylish, and entertaining horror film. In the process, they also shaped a myth appropriate for an age full of tensions and troubles. While the word “zombie” is never used in the film, Night of the Living Dead represents the Ground Zero of the modern zombie story. 1968, of course, was a year marked by assassinations, political unrest, the Vietnam War, changes in social and sexual mores, racial violence, and other unsettling changes. Night of the Living Dead took on those fears and worries metaphorically by transmuting them into ghouls outside a farmhouse, trying to break in and attack the living.

Did Romero and Russo consciously set out to offer cultural critique in their story? Yes and no. Romero talked in interviews about how the model of Richard Matheson’s science-fiction novel I Am Legend offered him a narrative of revolution, of the world being turned upside down, that he very much liked and wanted to explore. But the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to which some viewers think the film’s ending refers to, took place after the completion of principal photography, and the film’s topicality is largely a result of the shape of the narrative itself. The Zombie Apocalypse has proven to be a particularly appropriate tale for an unsettled world, as Night of the Living Dead (and the reaction to it) amply demonstrate.

As with many artists, in this film Romero was anticipating as much as he was responding. A story about zombies who attack in waves, about humans who resist and quarrel about how to resist, and about the fear that we will lose our identity turned out to be the right story at the right time. A similar congruence comes just after 9/11, when the British horror film 28 Days Later set off the zombie craze in which we still reside.

White Walker fight from the HBO series’ Game of Thrones. (c) HBO via Game of Thrones Wiki.

White Walker fight from the HBO series’ Game of Thrones. (c) HBO via Game of Thrones Wiki.In reshaping the zombie story from its origins as a narrative about slavery and dominance in the Caribbean, to a story about supernatural ghouls who threaten all human life, Night of the Living Dead offered a contemporary example of a trope familiar in the West for at least 600 years in which Death or the dead confront the living in art and literature in times of crisis. Romero’s modern zombie story is an updated version of the Danse Macabre in which embodied Death reaches out to every member of the society and yanks them into the next life. It is also a cathartic tale of ultimate horror that feels much like our current experience, but which we can turn off or put down, grateful that however bad the terrors of the present moment might be, at least the dead are not trying to knock down our doors.

Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead are two of our culture’s most-widely consumed versions of the Zombie Apocalypse story Romero inaugurated. In Game of Thrones, the often-foregrounded storylines of characters vying to sit on the Iron Throne are finally beginning to be overshadowed by the conflict between members of the Night’s Watch and the White Walkers (“The Others”) who command the walking dead. While the plots concerning royal succession are filled with human interest, intrigue, sexuality, and violence, some characters (and many critics) have suggested that all these are no more than the arguing of attractive children over toys. When you see the dead walk, as Melisandre (Carice van Houten) and Jon Snow (Kit Harrington) have, it becomes clear that nothing else matters. In this way, the Zombie Apocalypse will determine Game of Thrones’ final outcome.

Like Night of the Living Dead in 1968, Game of Thrones uses the Zombie Apocalypse to wrestle with the threats of our own age, not just the obvious ones, but also perhaps the ones to which we’re simply not paying enough attention. So, as in Romero’s films, Game of Thrones helps its viewers to grapple with such menaces as international terrorism, economic unrest, refugees, pandemics, and natural disasters. But by showing how easily we can be distracted from greater menaces and how often people prefer not to believe that “Winter Is Coming,” it also encourages us to pay attention to undervalued or often-dismissed threats. In what ways, for example, might human beings be contributing to climate change, the decline of bees, the extinction of animal species, or any number of potentially apocalyptic crises that we ignore?

Romero’s films were recognized in his lifetime as entertaining,important, and culturally relevant. His great final achievement may be that he bequeathed to us a master narrative with which we can confront our fears. In the Zombie Apocalypse, the people of 2017 too can find meaning, comfort, and insight into our own lives, and for that, we can thank George Romero.

Featured image credit: The Toronto Zombie Walk “Special Director’s Cut Edition” at the Toronto International Film Festival, 2009 by Josh Jensen. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post George Romero, Game of Thrones, and the zombie apocalypse appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers