Oxford University Press's Blog, page 336

August 13, 2017

DNA testing for immigration and family reunification?

During the past decade, immigrants accounted for 47% of the increase in the US workforce and 70% in Europe. Family reunification is one of the main forms of immigration in many countries. However, in recent times, immigration has become increasingly regulated with many countries encouraging stricter vetting measures. In this climate, countries’ laws and policies applicable to family reunification seek a balance between an individual’s right to a family life and a country’s right to control the influx of immigrants. The use of DNA testing (using blood samples or buccal swabs collected from the sponsor and each of the applicants) has been included in the family reunifications processes to help confirm a biological link between the sponsor and the applicants in at least 21 countries including Austria, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the USA. As numerous jurisdictions use DNA testing in their family reunification processes, can the use of DNA testing help achieve a better balance between promoting family reunification and enabling better control of the immigration demands?

On the one hand, given that the test results are considered very accurate, reliable, and scientifically valid, the use of this test has been deemed to have a number of benefits. It is viewed as helpful for immigrants whose birth or baptismal certificates are unavailable, non-existent, or unreliable. It is deemed to add neutrality to the migratory process, as the decision becomes less discretionary than if it solely depended on the immigration officer’s interpretation of the supportive documentation. It is also considered to make the process more efficient, faster, and cheaper, because the results can be self-explanatory. Therefore, it is not necessary for immigrants to hire lawyers or for the government to train its immigration officers to be able to properly interpret the supporting evidence or to interview the potential immigrants or for either of them to wait long periods of time for all of the above to be concluded. Lastly, it is considered helpful to prevent fraud, human trafficking, and misuse of the process, as potential immigrants who know they do not have a true familial link may be discouraged from initiating the process.

On the other hand, there are criticisms based on legal, social, and ethical concerns raised not by the test itself, but by the way it is implemented. The test is usually “suggested” in cases where documents are unavailable or unreliable (mainly in cases of potential immigrants from a specific list of countries of Africa, Asia, or Latin America), done in accredited laboratories, and paid by the immigrant (although in some cases, the government will directly cover or reimburse the costs of the test). Some countries assign such an enormous evidential weight to the test that a negative result or a refusal to undergo the test would very likely lead to the rejection of the application.

Can the use of DNA testing help achieve a better balance between promoting family reunification and enabling better control of the immigration demands?

Sociologically, the definition of “family” based solely on a biological link (the result of a DNA test), disregards any other physical, psychological, social, intellectual, or spiritual factor or element of a relationship between two family members. In this sense, the requirement of DNA testing in these terms can disrupt immigrants’ family lives and consequently, parents’ care of their children; their emotional well-being; personality; identity; social and affective skills; integration to the host country; and even their work/school performance. The latter could have a negative impact on the host country’s economy, as immigrants constitute an important part of the world’s workforce.

There are various ethical concerns with the use of DNA testing in family reunification processes. Firstly, it is problematic that the majority of the countries using DNA testing in their family reunification processes neglect to provide genetic counseling services prior to or after the immigrants undergo the test. Additionally, signatories to the Prüm Convention store and share the information collected from the migratory process with the other signatories to combat terrorism, cross-border crime, and illegal migration without the immigrants’ consent. Moreover, their state of vulnerability while applying for family reunification diminishes their autonomous consent to undergo the test. Finally, their informed consent can be violated because they lack the power to prevent secondary uses of their genetic information.

Legally, there are concerns about issues of discrimination based on country or origin, religion (some religions do not allow forms of this test), socio-economic class (the cost per applicant is between $230 and $1250), non-traditional models of families (e.g. LGBT, blended, extended, or reproductively assisted families, and those that include orphans), and unwed parents (it is more frequent for unwed parents to be suggested to undergo the test). Furthermore, nationals’ privacy and dignity are better protected and their familial relationships are less scrutinized than those of foreigners.

Countries have a sovereign right to control their immigration regulations and policies, and as discussed, DNA testing can be useful in protecting this right. The consistency in the benefits of families as the optimal foundation for physical and emotional well-being has even resulted in international agencies and instruments upholding a human right to a family. However, families are formed and shaped by many factors, complexities, and dynamics that DNA is incapable of fully capturing. Immigration laws, regulations, policies, and practices have to be reasonable, justifiable, and proportional to principles of equality, inclusiveness, efficiency, human dignity, and respect for more pluralistic concepts of family. Specifically, it would be beneficial if countries truly maintained the use of the DNA testing as a “last resort” for cases where it is appropriate/necessary to suggest it, preserved an inclusive concept of family, and provided immigrants with as much information as possible regarding the test and its potential outcomes.

Featured image credit: Puzzle by qimono. CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post DNA testing for immigration and family reunification? appeared first on OUPblog.

It’s education, stupid: how globalisation has made education the new political cleavage in Europe

The Brexit referendum and the Dutch and French elections have shown that the traditional distinction between right and left is becoming obsolete. Commentators argue that a globalisation cleavage is appearing in western Europe, with the issues of migration and European integration core bones of contention. We argue that at a deeper level it is not just globalisation or the EU that drives this contestation. The new political divide is also rooted in demographic changes, it is a manifestation of the rise of a more structural, educational cleavage. It’s no longer just the economy, it’s education.

Tell us what your highest diploma is, and we will tell you who you are and what you do. If you are a university graduate, you will watch public television, such as the BBC or its equivalent in other European countries (such as Canvas in Belgium) and read ‘quality’ papers, such as The Guardian, Die Zeit, or Libération. You will do your utmost to get your children into public school in the UK, a Gymnasium in Germany and the Netherlands, or one of the Grandes écoles in France. You will live in a university town, a green pre-war suburb, or in the 19th century, gentrified parts of the inner cities, such as Prenslauer Berg in Berlin, De Pijp in Amsterdam, or Notting Hill in London. You will be moderately in favour of the EU, worry about climate change, the state of higher education, xenophobia, and vote for a Green or social liberal party.

On the other hand, if your education ended after junior high school or primary vocational training, the chances are you will watch commercial television, such as SBS, VTM or ITV, and read tabloid papers – if you read any newspaper at all – such as The Sun in England, Bild in Germany, or BT in Denmark. Your children will attend a local state school in the UK, a large “ROC” in the Netherlands, or a “lycée professionnel” in France. You will live in former industrial areas and manufacturing towns, in post-war satellite cities, such as Marzahn in Berlin, Lelystad in the Netherlands, or Slough in England, or in the 20th century outskirts of the major cities. You will be highly sceptical about the EU, worry about crime and immigration, and vote for a nationalist party, or perhaps not at all.

Our research shows how the contours of this new divide have crystallised in western and northern Europe. Using a broad notion of cleavage, we find the rise of an educational cleavage reflected along three lines: a new socio-demographic division, differences in terms of political preferences, and the appearance of a new divide in the political landscape.

The rise of the well-educated as a new social segment

Cleavages are rooted in demography. For a large part of the twentieth century it made little sense to speak of distinct educational groups, because the group of well-educated citizens was so small. This changed as a consequence of rising educational attainment levels. In 2015, according to the OECD, 27% of the EU workforce (using a group of 22 EU countries) were well educated – more than double the 11 per cent who classified as well-educated EU citizens in 1992 and more than twenty-five times higher than the meagre 1 per cent recorded in the 1960s.

This emerging educational segmentation comes with an increased stratification and segregation along educational lines, with unequal access to housing, health, and job opportunities. Moreover, education is an important driver of new patterns of homogamy. The well educated and the less well educated live in different social worlds and do not mingle. They differ in health, in life expectancies, in wealth, and in income.

Cosmopolitans versus nationalists

Traditionally, most voters in western Europe can be positioned along a social-economic, left–right dimension and along a religious–secular dimension. In addition to these traditional conflict dimensions, which reach back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a new cultural conflict dimension has manifested itself in the past three decades. This new division between what could be called ‘cosmopolitans’ and ‘nationalists’ has emerged gradually, fuelled by the waves of non-western immigration and the process of European unification.

This division between cosmopolitan and nationalist attitudes coincides in western European countries with the education divide. Ranged on one side of this new line of conflict are the citizens who accept social and cultural heterogeneity and who favour, or at least condone, multiculturalism. These are the more highly educated. On the other side are citizens who are highly critical of multiculturalism and who prefer a more homogeneous national culture.

In the 2016 Brexit referendum, strong educational differences could be observed. With the exception of Scotland, the Leave vote was much higher in those regions of Britain populated by citizens with low education qualifications, and much lower in those regions with a larger number of university graduates. According to Matthew Goodwin and Oliver Heath: ‘fifteen of the 20 “least educated” areas voted to leave the EU while every single one of the 20 “most educated” areas voted to remain.’

The rise of social-liberal versus nationalist parties

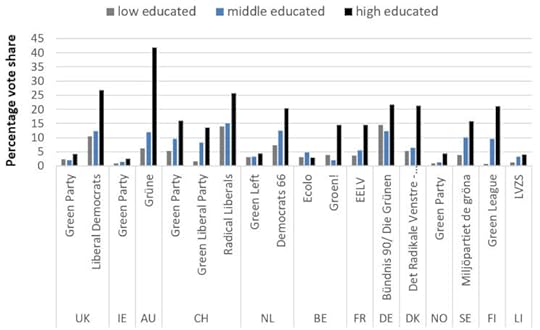

Cleavages manifest themselves also in the support for specific political parties. New parties with new types of preferences have recently entered the political stage across Europe. On the one side of the new cultural dimension of conflict, we see the emergence of Green and social liberal parties, such as Groen! and Ecolo in Belgium, Les Verts in France, The Greens in Germany, D66 and GroenLinks in the Netherlands, and the Liberal Democrats in the United Kingdom, to name but a few. Since the late seventies, they have become established political actors throughout western Europe. In all countries, the Green and social liberal parties predominantly attract voters from the high end of the education spectrum, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Link between education and support for Green and Left-liberal parties (2014) Note: The chart shows the percentage of people who had voted for selected Green and Left-liberal parties in the previous election from different educational groups. Figures are compiled using the 2014 European Social Survey.

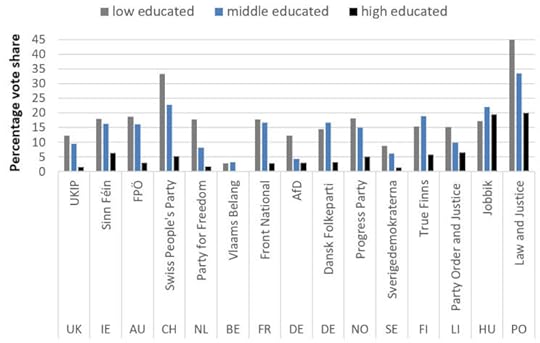

Figure 1: Link between education and support for Green and Left-liberal parties (2014) Note: The chart shows the percentage of people who had voted for selected Green and Left-liberal parties in the previous election from different educational groups. Figures are compiled using the 2014 European Social Survey.On the other side of this cultural conflict, we see the emergence of nationalist populist parties such as the FPÖ in Austria, Vlaams Belang and NV-A in Belgium, the Danish People’s Party, the Finns Party, France’s Front National, the AfD in Germany, Lega Nord in Italy, the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, the Sweden Democrats, and UKIP. These nationalist parties tend to draw large proportions of the low and medium-educated voters, and relatively few well-educated voters as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Link between education and support for nationalist parties (2014). Note: The chart shows the percentage of people who had voted for selected nationalist parties in the previous election from different educational groups. Figures are compiled using the 2014 European Social Survey.

Figure 2: Link between education and support for nationalist parties (2014). Note: The chart shows the percentage of people who had voted for selected nationalist parties in the previous election from different educational groups. Figures are compiled using the 2014 European Social Survey.Political contestation regarding globalisation issues should thus be understood as only part of the puzzle. Underneath it, the contours of an educational cleavage have become visible. Educational differences matter most in societies that are meritocratic – in which access to higher education, the labour market, and social stratification are based on merit instead of class or patronage.

This is particularly the case in western and northern European countries, such as Belgium, Denmark, and to a somewhat lesser extent the Netherlands, the UK, Finland, Austria, and Switzerland. In these countries, the contours of something resembling a full educational cleavage are visible. The nationalist populist parties on the one hand, and the Greens and social-liberals on the other hand, embody the institutionalisation of this new political conflict line. They have gained a lasting place in the political arena because they represent groups of voters who not only share a particular set of issue attitudes, but also specific social characteristics – their educational background.

A version of this article originally appeared on the EUROPP blog by LSE.

Featured Image Credit: Direction road look by aitoff. Public Domain via Pixabay,

The post It’s education, stupid: how globalisation has made education the new political cleavage in Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

Richard Susskind on the future of law

In the latest episode of the Oxford Law Vox podcast Richard Susskind talks to George Miller about the gaining momentum of technology and AI in the law profession. They discuss just how vital it is that lawyers learn to reinvent themselves and work alongside technology.

He also address the importance of the opportunity young lawyers have to bring about and be a major part of social change in the legal profession.

Below are selected excerpts from their extensive conversation, with access to the full episode on the Oxford Law Vox, as well as a bonus episode on his longstanding interest in technological change.

George began by asking about Richard’s motivation for writing the second edition of the book.

“When I read through the book I realised it really wasn’t serving its purpose anymore … I don’t think the tone or the message has changed. The messages are the same – that if we want to improve access to justice in our society then technology provides a great route. I think our law schools are still out of step. I think if you are a conventional lawyer and you’re not prepared to adapt to the [2020’s] you’ll struggle to survive, but if you are entrepreneurial and enthusiastic, forward looking, open minded, then there’s probably never been a more exciting time to be in the law.”

Richard addressed the issue that the people who are most supportive of innovation in the profession often do not yet have the power to implement change.

“If you don’t have a group of leaders within your business that are supportive of technology and you are sitting there as a junior lawyer who has all sorts of ideas for rethinking legal services … you’re probably not in the right business, I’m afraid. It’s very hard to manage upwards and to help fundamentally rejig, reorganise your firm if you’re a very junior partner or not a partner at all … Now is the time to think less about safety and more about legacy. What is it as a business that we’re leaving to the generation that’s coming through? … More often we call a firm innovative by referring to the group of people who happen to be running it at one point in time, who are forward-looking, and there’s not a lot you can do about that if you haven’t got that group of leaders. As I say, you may have to find a firm that actually does support new ideas and innovation and change.”

They discussed if Richard felt that there are new career options opening up for lawyers which are as stimulating and rewarding as conventional roles.

“I do but others don’t, by which I mean I think there’s certainly a whole new range of legal jobs emerging … I go back to this general phenomenon that we are seeing across society that so many different sectors have had to reinvent themselves, people have had to retool and retrain … The question about whether or not there is a viable legal profession out there really is a question of whether or not there will be a sufficiency of new tasks for lawyers that will emerge for lawyers to do …

I say to young students – you are wanting to make the world a better place, you’re studying law, you want to help people understand their entitlements. So one thing is you can go out and learn a lot as a lawyer and you can advise maybe 10,000 clients in your career. How about actually instead developing an online system that can help a few million people, why don’t you use your legal knowledge in different ways?”

George ended by addressing Richard’s optimism that there are positive developments happening in the profession to encourage legal access for all.

“We are expected all of us under the law to know of our rights and obligations and yet it has become a perilous system to which very few of us have ready and reasonable access, and I think that’s tragic and we need to do something about it … A system that can help us avoid having disputes in the first place, whether it be by public access to legal materials, public legal education, online legal services, better advisory services and so forth. It’s important I think that people have ready access to the law that’s applicable to them … We should want our systems and our technologies to help us, alert us, to occasions not just where there is a legal threat or risk, but also where there is a legal opportunity.”

Featured image credit: ‘Background, Circuit, Grey, Digital’ by 3mikey5000. CCO via Pixabay.

The post Richard Susskind on the future of law appeared first on OUPblog.

Are electrons conscious?

For most of the twentieth century a “brain-first” approach dominated the philosophy of consciousness. The idea was that the brain is the thing we really understand, through neuroscience, and the task of the philosopher is try to understand how that thing “gives rise” to subjective experience: to the inner world of colours, smells and sounds that each of us knows in our own case. This philosophical project has not gone all that well–nobody has provided even the beginnings of a satisfying solution to what David Chalmers called “the hard problem” of consciousness. More recently a quiet revolution has been occurring in philosophy of mind which aims to turn the brain-first approach on its head. According to the view that has come to be known as “Russellian monism,” physical science tell us surprisingly little about nature of the brain (more on this below). It is the nature of consciousness that we really understand–through being conscious–and hence the philosophical task is to build our picture of the brain around our understanding of consciousness. We might call this a “consciousness-first” approach to the mind-body problem. The general approach has given birth to a broad family of specific theories outlined in numerous recent publications. Suddenly progress on consciousness looks possible.

The essence of Russellian monism

The conscious mind and the physical brain seem on the face of it to be wildly different things. For one thing, conscious experiences involve a wide variety of what philosophers call “phenomenal qualities.” This is just a technical term for the qualities we find in our experience: the redness of a red experience, the itchiness of an itch, the sensation of spiciness. A neuroscientific description of the brain seems to leave out these qualities. How on earth can quality-rich experience be accommodated within soggy grey brain matter? The Russellian monist solution, inspired by certain writings of Bertrand Russell from the 1920s, is to point out that physical science is in fact silent on the intrinsic nature of matter, restricting itself to telling us what matter does. Neuroscience characterises a region of the brain in terms of (A) its causal relationships with other brain regions/sensory inputs/behavioural outputs and (B) its chemical constituents. Chemistry in turns characterises those chemical constituents in terms of (A) their causal relationships with other chemical entities and (B) their physical constituents. Finally, physics characterises basic physical properties in terms of their causal relationships with other basic physical properties. Throughout the whole hierarchy of the physical sciences we learn only about causal relationships. And yet there must be more to be more to the nature of a physical entity, such as the cerebellum, than its causal relationships. There must be some intrinsic nature to the cerebellum, some way it is in and of itself independently of what it does. About this intrinsic nature physical science remains silent. Accepting this casts the problem of consciousness in a completely different light, and points the way to a solution. Our initial question was, “Where in the physical processes of the brain are the phenomenal qualities?” Our discussion has led to another question, “What is the intrinsic nature of physical brain processes?” The Russellian monist proposes answering both question at once, by identifying phenomenal properties with the intrinsic nature of (at least some) physical brain processes. Whilst neuroscience characterises brain processes extrinsically, in terms of what they do, in their intrinsic nature they are forms of quality-rich consciousness.

Two Arguments for Panpsychism

Russellian monism is a general framework for unifying matter and mind and thereby avoiding dualism: the view of Descartes that mind and body are radically different kinds of thing. But how to fill in the details is much debated. Many have founded it natural to extend Russellian monism into a form of panpsychism, the view that all matter involves experience of some form, bringing a new respectability to this much maligned view. There are essentially two arguments for this extension, one of which I don’t accept and one of which I do. The first is the “intelligible emergence argument,” an ancient argument for panpsychism championed in modern times by Galen Strawson. The idea is that it is only by supposing that there is consciousness “all the way down” to electrons and quarks that we can render the emergence of human and animal consciousness intelligible. Experience can’t possibly emerge from the utterly non-experiential, according to Strawson, so it must be there all along. One difficulty for this argument is that even if we do attribute basic consciousness to the smallest bits of the brain, it’s still not clear how to intelligibly account for the consciousness of the brain as a whole. How do the interactions of trillions of tiny minds produce a big mind? This is the so-called ‘combination problem’ for panpsychism, and until it is solved it’s not obvious that the panpsychist Russellian monist has an advantage over the non-panpsychist Russellian monist when it comes to explaining the emergence of human and animal consciousness. I favour instead what I call ‘the simplicity argument’ for panpsychism. Whilst in the mind-set that physical science is giving us a complete picture of the universe, panpsychism is implausible, as physical science doesn’t seem to be telling us that electrons are conscious. But once we accept the basic tenants of Russellian monism, things look quite different. Physical science tells us nothing about the intrinsic nature of matter; indeed arguably the only thing we know about the intrinsic nature of matter is that some of it, i.e. the brains and humans, have a consciousness-involving nature. From this epistemic starting point, the most simple, parsimonious speculation is that the nature of matter outside of brains is continuous with the nature of matter inside of brains, in also being consciousness-involving. This may seem like an insubstantial consideration, but science is strongly motivated by considerations of simplicity. Special relativity, for example, is empirically equivalent to its Lorenzian rival but favoured as a much simpler interpretation of the data.

Against neuro-fundamentalism

Some philosophers–I call them “neuro-fundamentalists”–think the only way to make progress on consciousness is to do more neuroscience. These philosophers have an exceedingly limited view of how science operates, as though it’s simply a matter of doing the experiments and recording the data. In fact, many significant developments in science have arisen not from experimental findings in the lab but from a radical reconceptualization of our picture of the universe formulated from the comfort of an armchair. Think of the move in the Minkowski interpretation of special relativity from thinking of space and time as distinct things to the postulation of the single unified entity of spacetime, or Galileo’s separation of the primary and the secondary qualities which paved the way for mathematical physics. My hunch is that progress on consciousness, as well of course as involving neuroscience, will involve this kind of radical reconceptualization of the mind, the brain, and the relationship between them. Russellian monism looks to be a promising framework in which to do this.

Featured image credit: Abstract lights. Image by Little Visuals. Public domain via Pexels .

The post Are electrons conscious? appeared first on OUPblog.

August 12, 2017

Is science being taken out of environmental protection?

In 1963, dying of breast cancer and wearing a wig to cover the effects of radiation treatments, Rachel Carson appeared before a congressional committee to defend her indictment of pesticides. She had rattled the chemical industry with Silent Spring, which urged caution at a time when Americans were buying dangerous products that the scientific community had itself made possible. Industry representatives mounted a vigorous campaign to discredit the scientific perspective she offered, some calling her work a hoax.

Attacks on science by industry—including attacks by scientists paid by industry, as was the case with Silent Spring—are common in the world of environmental regulation. Just as Silent Spring ushered in the modern environmental movement, ironically so did it also provoke this tactic. Fortunately, however, our government has until recently recognized the need for strong science as a cornerstone of modern environmental policy and has incorporated scientific perspectives into the heart of its decision-making. In the words of the Executive Order that established the EPA in 1970, one of the key functions of the new agency was “the conduct of research on the adverse effects of pollution and on methods and equipment for controlling it.”

A good example of this recognition is the EPA’s 47-member Scientific Advisory Board (SAB), established in 1978 at the direction of Congress. The SAB reviews the quality and relevance of scientific research and data when the EPA is creating environmental regulations. EPA ethics officials screen its members—mostly leading academics—for conflicts of interest to ensure they are independent and not tied to special interests. EPA’s current SAB website notes that “a key priority for EPA is to base Agency actions on sound scientific data.”

The EPA often requests the SAB to independently peer review major reports that will undergird future regulations. In 2016, for example, the SAB reviewed a major report concerning the impact on the nation’s drinking water of hydraulic fracturing, a lucrative and controversial method of extracting natural gas. The review resulted in changes to the final report that were met with criticism from the oil and gas industry.

The headquarters of the United States Environmental Protection Agency in Washington, D.C. Photographed on en:August 12, en:2006 by user Coolcaesar. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The headquarters of the United States Environmental Protection Agency in Washington, D.C. Photographed on en:August 12, en:2006 by user Coolcaesar. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Things are different today. The President’s current budget proposal would cut SAB funding by 84 percent. The EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt, has dragged his feet in appointing a new SAB Chair to fill a term that ends in September. The selection process, which in the past has been transparent, with public input, and a multi-month effort, has just begun. Will it be a rush job? Will it be transparent? What is the relationship of this foot-dragging to Pruitt’s connection with oil and gas interests in Oklahoma, his home state? And why is Pruitt not encouraging renewed terms for members of the Board of Scientific Counselors (BOSC) who have distinguished themselves by their service? According to Pruitt’s spokesman, the objective is to broaden the Board to include people who understand the impact of environmental regulations on the regulated community. This is not how Ken Kimmel, the President of the Union of Concerned Scientists, sees it. To him, Pruitt’s signal to the BOSC is “part of a multifaceted effort to get science out of the way of the deregulation agenda.”

It appears that congressional House Republicans are proving Kimmel right. They passed the EPA Science Advisory Board Review Act in March 2017 on a straight party line vote: 229 to 193. The bill ensures that industry representatives will have strong voices, strong enough perhaps to drown out the independent scientists currently on the Board. The bill eases conflict of interest rules, blocks academic researchers, and burdens the SAB with requirements that deter scientists lacking industrial financial support. As Eddie Bernice Johnson, ranking member of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, put it, “This bill is a transparent attempt to slow down the regulatory process and stack science review boards with industry representatives. The result would be. . .worse science at EPA and less public health protection for American citizens.” Which brings us back to hydrofracking. How would a SAB reimagined in a new Science Advisory Board Review Act, and reconstituted by industry-friendly Scott Pruitt, have come out in its review of the hydrofracking study?

Voices from industry are important. They are rightly given ample platforms throughout the regulatory process. Indeed, some of the most robust and voluminous comments come from representatives from industries such as the American Petroleum Institute, the Chemical Manufacturers Association, or Exxon Mobil. Such institutions also have outsized lobbying voices, some of which reach into the legislative process and influence the drafting of laws under consideration by government officials.

Science needs voices too. The Science Advisory Board and the Board of Scientific Counselors have been among them for years but now are under attack. Our highest levels of government need to protect the role of strong science as EPA staff labor to protect public health and the natural world.

Featured image credit: “Air Pollution” by Pexels. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Is science being taken out of environmental protection? appeared first on OUPblog.

What makes a good manager? [excerpt]

Is modern work culture is pushing otherwise good people to adopt poor management styles? From creating “growth opportunities” to taking on mentors, managers often find themselves falling into progressive traps that seem like the right thing to do, but ultimately lead employees astray. In the following excerpt from Good People, Bad Managers, Samuel A. Culbert examines the effectiveness of modern management approaches.

When it’s called to their attention, most managers quickly recognize the value of new management approaches and the importance of upgrading their current style. But the work culture has them fearful of taking a new direction and possibly making an image- discrediting mistake. Wading into the waters of change, but risking only one toe at a time, they seldom make sufficient headway to realize the momentum required to continue progressing. In the end, they talk enthusiastically about progressive practices but don’t commit to system change. And do they ever talk. Knowing change is needed, wanting to think themselves avant-garde and progressive, they speak enlightenment words. But it’s old wine in new bottles.

Passing timelines and meeting benchmarks, managers “progress- up.” They no longer make assignments, they provide “growth opportunities” and “challenge a person’s potential.” They don’t ask for help, they “reach out.” Their direct reports are no longer their employees, they are “business partners.” They don’t persuade and convince, they “discuss to get buy- in.” They no longer assign people to project groups, they assign them to “tiger teams” and invite them to “take journeys together.” Instead of working the data, it’s a “deep dive” and “taking analysis to the next level.” Finding someone proposing a course of action they like, they don’t just concur, now they’re “in violent agreement”— which always scares the hell out of me. When a manager wants someone’s focus, they say “let me be honest with you” and “time to open the kimono” without realizing they might be admitting that past declarations lacked truthfulness and, should I say it, a certain degree of “intimacy.” Do these words really change anything? Does anyone work “inside the box” anymore?!

The field of management has gone too many years implementing new and progressive management practices without much fundamental progress made. Employees want managers to perform their mandated other- directed duties. They need managers to help them accomplish what they’re unable to do for themselves. But this entails managers acknowledging past insufficiencies, admitting error, and taking other directed approaches to managing. Is it that managers need different guidance from their higher- level managers and leaders, or is it that they’re too insecure and system suspicious to vary from what they know? Probably it’s both.

The field of management has gone too many years implementing new and progressive management practices without much fundamental progress made.

Unfortunately, when managers find the approach they’re using not working, too often their backup approach is going longer and stronger with the same approach that didn’t work. And when that doesn’t overpower employee resistance, you know what they do. It’s a route we’ve already traveled. They blame their employee for not being responsive. Responsive to what? Responsive to the self- serving, pretentious practices the work culture claims is good managerial behavior.

When asking top- level managers how they got to the top, a large percentage cite someone “big” who, recognizing their potential, took them under their wing, so to speak, and set about opening doors. In today’s lexicon that’s called “being mentored.” But I don’t find mentoring a company plus. A mentor is someone playing favorites, short- circuiting the system, and ensuring preferential treatment at the expense of system- wide fair play.

Needless to say, mentors don’t think what they’re doing is negative. In their minds they’re practicing good management, doing what’s objectively right for the company. They’re cultivating talent, keeping people challenged, and fast- tracking “high performers” to ensure the company doesn’t lose them. It’s as if what they are doing is part of some grand retention strategy. Well, as much as I hate to rain on anyone’s happiness parade, playing favorites by mentoring is not the good management development system companies should be shooting for. Good management is not about mentoring one individual at a time. It’s about fixing the system so that everyone can be their best and help the company, and creating the circumstances for individuals to realize their ambitions and dreams.

Managing in today’s work culture is fraught with too many demands for managers to assume a more other-directed focus and mentality. To do so, managers would have to put self- pursuits on hold, drop the pretense of objectivity, and work collaboratively with cohorts to identify and remove obstacles to employee effectiveness companywide. Other- directed management requires providing employees the assurances needed to feel safe speaking their minds. Give employees a voice and managers will finally have the data they now lack for facing up to their mistakes and revising the erroneous reasoning that led to their making them. The way things are going now, what I’m talking about appears light- years away.

Under what circumstances can employees and cohorts expect to get the type of managerial good behavior they need? It’s obvious; the culture has to change.

Featured image credit: conference room table office by Free-Photos. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What makes a good manager? [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 11, 2017

From singer to choir director: A Q&A with Ben Parry

Ben Parry studied at Cambridge University, where he was a member of The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, before he became the musical director of, and singer with, the Swingle Singers. Today, Ben has a busy career as a conductor, arranger, singer and producer in both classical and light music fields; directing choirs as varied as the National Youth Choirs of Great Britain and the professional choir London Voices, to the King’s College Cambridge mixed choir – King’s voices, and Aldeburgh voices. We caught up with Ben to ask him about his progression from singer to director, his conducting experiences, and his advice for directors wishing to set up their own choirs.

With the amount of conducting work you do, you must have to move around a lot! Could you tell us what a typical week in your life looks like?

Any week can be crazy but very rewarding! A typical week might include a choral evensong in King’s (as director of King’s Voices), a film session at Abbey Road or Air Studios with my professional choir – London Voices, a meeting for National Youth Choirs of Great Britain, a rehearsal at Snape Maltings with Aldeburgh Voices, and, sometimes, composing or arranging choral music at home.

Although you started out as a singer, much of your work now revolves around directing. How did you make the progression from singer to director?

I got really interested in choral conducting just before I moved to Edinburgh with my family in 1995. In Edinburgh, I quickly became Chorus Director of the Scottish Chamber Chorus and I also started my own group, Dunedin Consort, which is now one of Scotland’s leading ensembles.

How did you learn to conduct?

My approach with choirs has been informed by observing the many conductors I have worked for – for example, Andrew Parrott’s natural and empathetic approach to music-making has been particularly influential. I’ve never had a conducting lesson, but have learnt my craft through retaining the good things and jettisoning the bad things from other conductors.

Ben Parry conducting in action. Used with permission.

Ben Parry conducting in action. Used with permission.The groups that you conduct range from amateur to professional choirs. Do your rehearsal and performance expectations differ between these?

One of the most satisfying things about conducting a range of choirs with differing abilities is how each approach informs the other. I expect the same enthusiasm, application, discipline, and attention to detail from whatever choir I’m working with. You’d expect that London Voices would deliver the goods almost without thinking about it, and that the commitment and enthusiasm of a choir like the National Youth Choir would be greater. However, sometimes it’s the other way round! It’s true to say that the more I put into a rehearsal or performance, the more I and the singers get out of it.

What do you look for when you’re recruiting new singers for the choirs you direct?

For younger choirs (National Youth Choir and Eton Choral Courses) you’re always looking for passion and potential, whereas London Voices relies on professional experience and reputation. With King’s Voices and Aldeburgh Voices, a shared love of singing is very important. But all singers should really share all of these qualities. I’d hate it if any of the singers I worked with weren’t happy singing. What I love is that sometimes the learning curve of a young singer on an Eton Choral Course is so much greater than the satisfaction of a job well done by one of the professionals.

What advice would you give to someone preparing for an audition to become a choir director?

It’s important to build up a good reputation through your work so people respect you and are confident in your abilities. I was offered co-direction of London Voices because Terry Edwards (founder and co-director) had heard I was good at running choirs. Stepping into someone else’s shoes can be hard, but it’s important to remain genuine.

Do you have any advice to offer to directors who are trying to set up their own choir?

The choral market is niche and definitely saturated with myriad choirs, so you need to be able to offer something unique and innovative – don’t just set up a choir because you want to. Ask yourself what the need is; it may be that you’d like to explore some undiscovered repertoire, or that the region you’re in doesn’t offer enough opportunities for keen singers. The journey through a music career can throw many challenges along the way, and isn’t always easy. But, if one does a good job, is enthusiastic, efficient, and polite you’ll go far and have a rewarding time!

Featured image credit: music notes sheet music bookeh and folder by David Beale. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post From singer to choir director: A Q&A with Ben Parry appeared first on OUPblog.

August 10, 2017

“My latest brain child”

In his 1954 essay ‘Metapsychological and Clinical Aspects of Regression within the Psycho-Analytical Set’, Donald Winnicott states:

“The idea of psycho-analysis as an art must gradually give way to a study of environmental adaptation relative to patients’ regressions. […] I know from experience that some will say: all this leads to a theory of development which ignores the early stages of the development of the individual, which ascribes early development to environmental factors. This is quite untrue. In the early development of the human being the environment that behaves well enough (that makes good-enough active adaptation) enables personal growth to take place.”

In a 1965 essay written for the British Psychoanalytical Society, ‘The Psychology of Madness: A Contribution from Psycho-Analysis’, he wrote:

“The practice of psycho-analysis for thirty-five years cannot but leave its mark. For me there have come about changes in my theoretical formulation, and these I have tried to state as they consolidated themselves in my mind. Often what I have discovered had been already discovered and even better stated […] This does not deter me from continuing to write down what is my latest brain-child.”

These words convey Winnicott’s most significant legacy to psychoanalysis: the theory of the mind of the Subject in constant evolution in its contact with the Other, along the pathway of life. This intuition has found important confirmations in the elements that have emerged from the research studies on the baby’s early stages of life, as well as from the explorations on the psychoanalytical treatment of borderline states and psychoses, and also regarding the approach to traumatic situations.

“Often what I have discovered had been already discovered and even better stated..”

Winnicott’s view of psychoanalysis aims to individuate the contexts – in terms of environment and treatment – in which the subject’s psychic life recovers and organizes itself according to new ways of functioning. He shows its plasticity, its potential for constant reorganization, and the presence of a way of functioning which is developmentally non-linear but experientially transformative in any stage of life.

Winnicott was aware that the development of psychoanalytic theory would greatly benefit from his clinical insights on the early stages of life of the mother-infant couple, and from the analysis of borderline patients. He was not indifferent to theory; on the contrary, he was curious and constantly researching. This biological and relational foundation of the development of the human being constitutes the fertilizing and founding core of his thought, which was received in Italy particularly by Eugenio and Renata Gaddini, to whom we must acknowledge the extraordinary merit of having grasped it and made it known.

Just because of this intrinsically biological and relational foundation, in relation to the well-known events linked to the Controversial Discussions in the British Psychoanalytical Society, Winnicott tried not to get stuck in a static and abstract ideological position, and he abstained from providing his theoretical-clinical findings with a coherent and complete theoretical structure. This is what others called “Winnicott’s illness,” as he himself remembered, with a certain ironical awareness, in a letter to Melanie Klein in 1952, in which he declines the offer to write a paper which should have been included in a book edited by her.

Winnicott presenting ‘A Psychotherapeutic Interview in Child Psychiatry’ at a Pre-Congress Clinical Seminar of the twenty-third Congress of the International Psychoanalytical Association, held in Stockholm on 24 July 1963.

Winnicott presenting ‘A Psychotherapeutic Interview in Child Psychiatry’ at a Pre-Congress Clinical Seminar of the twenty-third Congress of the International Psychoanalytical Association, held in Stockholm on 24 July 1963.Courtesy of Barbara Young, held in Donald Woods Winnicott Archive, in the care of the Wellcome Library.

However, in 1971, the very year of his demise, Winnicott decided to publish a book, Playing and Reality, which comprises in an organic – albeit not organized – manner, his papers on the theory relative to his most significant psychoanalytical discovery; the individuation of the transitional area in the psychic functioning of the human subject.

The conceptual developments of Winnicott’s thought were not organized by him in a coherent and complete scheme; they were scattered as discrete elements which fertilized several fields and different theories. As is the case with every particularly creative thinker, a later, inevitable reductionist phenomenon took shape. The founding formula: “there is no such thing as a baby, there is a baby and someone”, was impoverished and reduced to a scheme that gave mechanical, excessive importance to the environment, obscuring the primary creativity of the infant.

However, the absence of a coherent and complete framework in Winnicott’s thought may also be read in another way, as the expression of his determined will not to renounce the polarity between biology and narration. A polarity which is intrinsic to Freud’s way of thinking, who had characterized its origin without reaching a unitary resolution; Winnicott confirmed and amplified such polarity, driving this tension forward.

In his Project for a Scientific Psychology, Freud’s intention was to develop psychology as a natural science which might express itself in terms of forces and structures, according to the language of the sciences of his time. But in Studies on Hysteria, written in the same period, the exposition of his clinical cases takes the form of a necessary narration, intrinsic to the theory from which they originated. Such polarity travels through the entire history of psychoanalysis.

Similarly, Winnicott did not intend to disarticulate his theory on psychic functioning from what he indicated as the psyche-soma, the sensory experience from which the mind takes its shape. At the same time, giving theoretical consistency to the area of transitional phenomena, and to the production of that intermediate world to which the analytic process also belongs, Winnicott confers to this third reality the status of a psychic structure that is fundamental for mental functioning.

Psychoanalytical productions, as well as artistic ones, utilize concrete, sensory elements which have a life of their own outside the subject, but which the subject recreates by conferring a personal meaning upon them. They do not belong to the field of hermeneutics, of descriptions and explanations as external captions for the subject’s psychic life.

Therefore, Winnicott maintains the implicit tension of Freudian thought between biological dynamics and narrative construction; he does not resign himself to formulate an organic theory that for the sake of completeness should renounce either experience or dreams as they emerge from the psyche-soma. Winnicott stays with this tension, convinced as he is that research studies, both in the biological field and in the relational field of the analytic situation, will yield further interesting results.

Featured image credit: Child by geralt. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post “My latest brain child” appeared first on OUPblog.

Culture, inequalities, and social inclusion across the globe: a ASA 2017 reading list

This year, the 2017 American Sociological Association Annual Meeting takes place in Montreal, and our Sociology team is gearing up. The 112th Annual Meeting will take place from 12- 15 August, bringing together over 5,000 sociologists nationwide for four days of lectures, sessions, and networking with some of the top figures in the field.

This year’s theme is “Culture, Inequalities, and Social Inclusion across the Globe.” The annual meeting is focusing on improving our understanding of the nexus of culture, inequalities, and group boundaries, in order to promote greater social inclusion and resilience, collective well-being, and solidarity throughout the world.

The conference schedule has a variety of meetings, workshops, and sessions to check out. Ahead of the conference, we have created a reading list of authors attending ASA17 to discuss important topics and issues within the field, and to raise awareness of current inequalities and promote social inclusions across the world.

Citizen Protectors: The Everyday Politics of Guns in an Age of Decline by Jennifer Carlson

A Gallup poll conducted just a month after the Newtown school shootings found that 74% of Americans oppose a ban on hand-guns, and at least 11 million people now have licenses to carry concealed weapons as part of their everyday lives. Why do so many Americans not only own guns but also carry them? In Citizen-Protectors, Jennifer Carlson offers a compelling portrait of gun carriers, shedding light on Americans’ complex relationship with guns.

Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present, and Collective Violence against the Armenians, 1789-2009 by Fatma Muge Gocek

Winner of the 2015 Mary Douglas Prize for Best Book, Sociology of Culture Section, American Sociological Association, and 2016 Barrington Moore Book Award, Honorable Mention, Comparative Historical Sociology Section of the American Sociological Association.

Denial of Violence develops a novel theoretical, historical, and methodological framework to understanding what happened and why the denial of collective violence against Armenians still persists within Turkish state and society.

National Colors: Racial Classification and the State in Latin America  by Mara Loveman

by Mara Loveman

Winner of the 2015 Best Scholarly Book Award from the American Sociological Association Section on Global and Transnational Sociology , and 2015 Oliver Cromwell Cox Book Award from the American Sociological Association Section on Racial and Ethnic Minorities.

Mara Loveman explains why most Latin American states classified their citizens by race on early national censuses, why they stopped the practice of official racial classification around mid-twentieth century, and why they reintroduced ethnoracial classification on national censuses at the dawn of the twenty-first century. The way census officials described populations in official statistics, in turn, shaped how policymakers viewed national populations and informed their prescriptions for national development—with consequences that still reverberate in contemporary political struggles for recognition, rights, and redress for ethnoracially marginalized populations in today’s Latin America.

Despite the Best Intentions: How Racial Inequality Thrives in Good Schools by Amanda E. Lewis and John B. Diamond

Through five years’ worth of interviews and data-gathering at Riverview high school, John Diamond and Amanda Lewis have created a rich and disturbing portrait of the achievement gap that persists more than fifty years after the formal dismantling of segregation. As students progress from elementary school to middle school to high school, their level of academic achievement increasingly tracks along racial lines, with white and Asian students maintaining higher GPAs and standardized testing scores, taking more advanced classes, and attaining better college admission results than their black and Latino counterparts. Most research to date has focused on the role of poverty, family stability, and other external influences in explaining poor performance at school, especially in urban contexts.

The Tumbleweed Society: Working and Caring in an Age of Insecurity by Allison Pugh

Today we live in a society in which relationships, social ties, and jobs seem to change constantly. People roll this way and that, like tumbleweeds blown across an arid plain. How do we raise children, put down roots in our communities, and live up to our promises at a time when flexibility and job insecurity reign? Allison Pugh offers a moving exploration of sacrifice, betrayal, defiance, and resignation, as people adapt to insecurity with their own negotiations of commitment on the job and in intimate life.

Wounded City: Violent Turf Wars in a Chicago Barrio by Robert Vargas

Winner of the 2017 Distinguished Book Award from the Political Sociology Section of the American Sociological Association and 2016 Outstanding Book Award, Section on Peace, War and Social Conflict, American Sociological Association.

Wounded City dispells the popular belief that a lack of community is the primary source of violence, arguing that competition for political power and state resources often undermine efforts to reduce gang violence. Robert Vargas argues that the state, through the way it governs, can contribute to distrust and division among community members, thereby undermining social cohesion.

Soybeans and Power: Genetically Modified Crops, Environmental Politics, and Social Movements in Argentina by Pablo Lapegna

Winner of the 2017 Best Book Award, Sociology of Development Section of the American Sociological Association.

Although Argentina’s use of genetically modified (GM) soybean seeds has spurred a major agricultural boom, it has also had a negative impact on many communities, including deforestation of native forests, prompted the eviction of indigenous and peasant families, and spurred episodes of contamination. Soybeans and Power investigates the ways in which rural populations have coped with GM soybean expansion in Argentina. It also gives voice to the communities most adversely affected by GM technology, as well as the strategies that they have enacted in order to survive.

Have questions for us? We’ll be at booths 915-919 in the exhibit hall with our latest books, journals, and online resources in sociology. The ASA Exhibit Hall will be located in Hall 220C in the Palais des Congrès de Montréal.

Stop by between the following hours:

Saturday, 12 August 2:00 – 6:00 p.m.

Sunday, 13 August 9:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m.

Monday, 14 August 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Tuesday, 15 August 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m.

We hope to see you in Montreal!

Featured image credit: Montreal City night by Free-Photos. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Culture, inequalities, and social inclusion across the globe: a ASA 2017 reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Introducing Hannah, OUP’s Music Hire Librarian

We are delighted to introduce Hannah Boron, who joined OUP’s Music Hire Library team in March 2017 and is based in the Oxford offices. We asked her to tell us what her job involves and chatted more generally about fantasy novels and how she would like to be Lara Croft.

What does a sheet music hire librarian actually do?

Some people are surprised, when I tell them what I do, that music publishers hire music to customers as well as sell it. Not all OUP music is available to buy. For large orchestral works like symphonies and concertos, for example, it often wouldn’t be cost-effective to print sets of parts to sell via music shops–but the music still needs to be available for people to access and perform.

That’s where the Hire Library comes in. We keep sets of orchestral parts (and sometimes vocal scores too) for a huge variety of works from composers as far back as Purcell and Monteverdi to those who are active now, like Bob Chilcott and Zhou Long. When a performing group wants to play an OUP work, they get in touch with us and arrange to borrow the parts they need for however long it will take them to rehearse and perform the piece, in exchange for a hire fee.

Some of the repertoire we hire out is also available for sale, which gives customers options, but if a performing group is only expecting to use the music once, they often feel it is better to hire than buy. Our customers range from small amateur ensembles to some of the UK’s top orchestras!

When did you start working at OUP?

Hannah Boron

Hannah BoronAt the end of March 2017, so very recently in relative terms! Somehow it feels as though it has been both shorter and longer than that, possibly because it’s such a friendly environment.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

I walk to work, which takes about forty minutes, and usually sets me up well for the day. The first thing I do, once I’m settled at my desk, is look in the email inbox and sort out the quote requests from the orders that can be booked immediately–and see if there’s anything urgent!

Then it’s time to assemble the orders that are due to be dispatched. The first batch of the day’s post is collected at 11am, after which I’m usually ready for a cup of tea! Depending on how many emails there are to reply to, it’s always good to spend some time booking returned music back into stock. There are often missing pieces of material to be chased up with customers too.

What are you reading right now?

I am a huge fan of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books, and am currently reading The Shepherd’s Crown. The last thing I read was Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, which is an opulently fantastical book: her use of language is truly virtuosic.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I would want to be either a writer or a singer. I have completed and published one fantasy adventure novel, involving a bounty hunt for thief gangs set in a pseudo-Middle Eastern landscape, and am working on another one.

I have sung in various different choirs over the years but am currently concentrating on my solo repertoire, mainly in the musical theatre genre. My recent performance of “Whatever Happened to my Part?” (from Spamalot) at the Abingdon Music Festival went down so well that I made it into the final concert! I’m quite quiet a lot of the time, so people are often surprised when they hear me sing. Apparently I have an inner diva…

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

I don’t think of myself as a particularly hardy person, so I would like to have the experience of being someone who is physically adventurous. Being Lara Croft would be awesome!

If you were stranded on a desert island, which three items would you take with you?

An endless supply of pens and paper, my keyboard (assuming there was a power source somewhere)–and a complete set of Discworld novels.

Featured image: Hire Library shelves by Elanor Caunt. Copyright Oxford University Press.

The post Introducing Hannah, OUP’s Music Hire Librarian appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers