Oxford University Press's Blog, page 340

August 1, 2017

A dangerous mission: loyalty and treason during the American Revolution

In September 1776, Nathan Hale and Moses Dunbar set out to support opposing forces in the American Revolution. Hale, a spy for the Continental Army, had volunteered to gather intelligence against the British. Dunbar had enlisted in the King’s Army and was commissioned to convince other young men to turn against the United States.

Both men were caught and executed before completing their missions—one remembered as a martyr and the other as a traitor to the American cause.

In the following excerpt from The Martyr and the Traitor, Virginia DeJohn Anderson compares the lives of these two men, and explores the differences that led them to a similar fate.

The American Revolution was at once a national, a continental, and an imperial phenomenon. It produced a new American republic, rearranged power relations and territorial claims across North America, and altered Europeans’ global empires. It inspired stirring statements about universal rights and liberties even as it exposed disturbing divisions rooted in distinctions of class, ethnicity, race, and gender. It affected—directly or indirectly, and often adversely—not only American colonists and Britons, but also French, Spanish, and even Russian colonists, Native Americans, and Africans and African Americans. The more we learn about it, the more complicated the Revolution appears.

For people who lived through it, the Revolution was even more confusing. Political upheaval and warfare intruded upon their households and communities, causing unprecedented disruptions and forcing them to take actions with unpredictable consequences. Driven by high-minded principles, self-interest, or a mixture of both, participants reacted to a multitude of factors—many of them local and highly personal—that loomed large for them but barely registered in subsequent grand narratives of the Revolution. This was as true for Indian peoples weighing the relative merits of neutrality versus alliance with one of the contending sides, African slaves pondering British invitations to seek their freedom, and French and Spanish officials along the Gulf Coast tracking developments on distant battlefields as it was for British Americans in the 13 rebellious colonies.

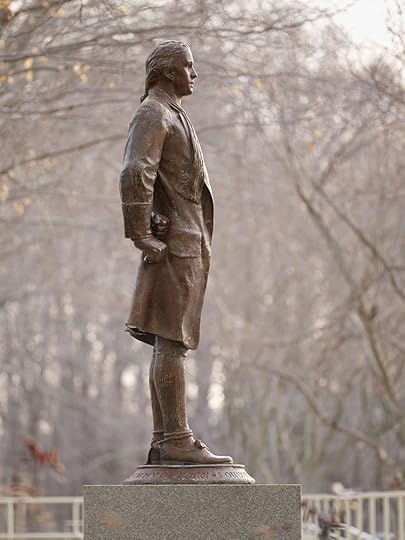

Statue of Nathan Hale, the first American executed for spying for his country. This statue is a copy of the original work created in 1914 for Yale University, Hale’s alma mater. Image credit: image provided by the Central Intelligence Agency. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of Nathan Hale, the first American executed for spying for his country. This statue is a copy of the original work created in 1914 for Yale University, Hale’s alma mater. Image credit: image provided by the Central Intelligence Agency. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.[/pull ]

Anxiety led many of those Americans to look beyond their British adversaries and detect secret enemies closer to home, thereby transforming the War for Independence into a civil as well as an imperial conflict. Internecine strife erupted in such places as the southern backcountry and parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Long Island, fracturing communities and even families. It also broke out in Connecticut, perhaps the least likely setting for such internal discord. Yet even there, neighbors who shared similar backgrounds in terms of religion, race, ethnicity, and economic status found occasion during the revolutionary tumult to fear and hate one another.

The stories of Moses Dunbar and Nathan Hale were deeply rooted in that Connecticut countryside and those unsettled times. Both men started out in life as sons of striving farmers laboring in agrarian villages whose inhabitants took for granted their membership in Britain’s empire. Although Hale and Dunbar never met, Connecticut was a small enough place that they had common acquaintances. Neither man’s choice of allegiance during the Revolution was foreordained; rather, it developed fitfully in the context of preexisting social relationships that initially had nothing to do with politics. Those personal connections became politicized as armed conflict neared, driving Dunbar to oppose American independence and Hale to support it. The challenge of balancing private responsibilities toward friends and family against the public demands of politics and war during such perilous times vexed many—if not most—colonists, no matter which side they were on. For very few of them, however, did engagement with that struggle lead to the gallows, as it did with these two men.

The deaths of Nathan Hale and Moses Dunbar might have been exceptional, but their lives were not. Their tragic stories offer a particularly dramatic demonstration of a common experience, showing how a welter of personal and political factors could confound people’s efforts to exert control over their lives in the midst of the Revolution.

Matters of timing were especially crucial to Hale and Dunbar and their posthumous reputations. Each man undertook the action that led to his death at a moment when nearly everyone believed that Britain stood poised to win the war. Had that happened, their respective roles as martyr and traitor would have been reversed. Posterity often takes America’s victory for granted; neither of these men—nor others in their communities—dared to do so.

The War for Independence is often seen as a “good war” with righteous patriots pitted against misguided, if not evil-minded, Britons and loyalists. Such an oversimplified popular version of events distorts what was a far more tangled history and ignores the participation of a far larger cast of characters, many of them living well beyond the bounds of the 13 original colonies. It does not even apply to the experiences of revolutionaries and loyalists in a small place like Connecticut, where no faction held a monopoly on principle. Each man met his death for acting in accordance with his beliefs. Nathan Hale and Moses Dunbar are both worth remembering because their tragic fates represent two sides of the same coin. They are equally part of America’s Revolutionary story.

Featured image credit: “Birthplace of Nathan Hale Coventry Connecticut,” circa 1800. Image courtesy of the Yale University Manuscripts & Archives Digital Images Database. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post A dangerous mission: loyalty and treason during the American Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Conquering distance: America in the Pacific War

Following a wave of Japanese attacks, the American, British, Canadian, and Dutch forces entered the Pacific War on 8 December 1941. As American forces moved across the Pacific they encountered a determined and desperate enemy and a harsh inhospitable environment. By early 1944, armed with new fast carriers, the Americans stepped up the pace of operations and launched the campaigns that would bring them to the doorstep of the Japanese homeland. But every step closer to Japan was a step farther from the United States.

The Americans confronted a host of obstacles in waging war across the Pacific, but of these, perhaps the most elemental and intractable was distance. The vast expanses of the Pacific mocked American efforts to bring the war to a speedy conclusion. As Hanson Baldwin, the New York Times military analyst noted, “[I]n the Pacific, distance is against us, and the problems of supply are mammoth.” The accompanying map, “Comparative areas of the United States and Southwest Pacific,” vividly illustrates the scope of the problem.

Distance strained American productive capacity and tied up shipping. A round trip voyage from San Francisco to Manila took on average sixteen weeks, three times as long as a circuit from the East Coast to France. That meant that the U.S. needed three ships in the Pacific to do the work of one in the Atlantic.

Hanson Baldwin was the military editor of the New York Times. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his work during WWII. Credit: “Hanson Baldwin” via the US Army Pictoral Center. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Hanson Baldwin was the military editor of the New York Times. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his work during WWII. Credit: “Hanson Baldwin” via the US Army Pictoral Center. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.When the Allies launched the invasion of Normandy, they had the advantage of gathering their forces in England, an industrially advanced nation, roughly fifty miles across the channel from their destination. Luzon, from which American forces would stage in preparation for the invasion of Japan, was approximately 1,400 miles from Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s main islands.

War in the Pacific was a war of bases, air and naval, but the Americans had to build them as they advanced, bringing with them the necessary construction materials, equipment, and manpower as they moved forward. In the Pacific, once the Allies moved beyond Hawaii and Australia, there were no modern ports capable of handling the large quantities of men and materials needed to sustain an advancing army. Often, supplies had to be shuttled in from ships anchored off the coast of an island and then hauled across the beaches on tracked vehicles. Scarcity of shipping and shortages of trained construction and engineer battalions hampered movement and became increasingly serious as American forces closed in on Japan in the final year of the war.

As Americans broke into the inner ring of Japan’s island defenses they prepared to redeploy millions of men and enormous amounts of equipment from Europe to the Pacific. The Army’s head of the Service of Supply succinctly captured the herculean scope of this effort when he compared the transfer of men and equipment from Europe to the Pacific to “moving all of Philadelphia to the Philippines.”

In the summer of 1944, the war entered a new phase with the capture of the Marianas Islands. In September, only a month past the end of organized resistance in the Marianas, the Navy seized a new fleet anchorage, Ulithi, an atoll in the middle of the Philippine Sea large enough and deep enough to hold over 600 ships. Fleet service vessels—oilers, store ships, water tankers, ammunition ships, vessels for spare parts and temporary repairs—now moved forward to Ulithi from Eniwetok, thereby positioning themselves 1,400 miles closer to the enemy. When the fleet kept at sea, re-fueling took place at rendezvous points on the water just out of range of the enemy. Tankers also transferred mail, and escort carriers transferred replacement planes and pilots. Seagoing tugs were added to tow disabled ships to floating dry docks at Seeadler Harbor in the Admiralties or Guam. With an extended and extending supply system, the fleet had extraordinary reach.

So too did the Army Air Forces, although the limitations imposed by the Pacific’s vast expanses continued to tax American resources. In late November, the first B-29 bombers were attacking Japan from the Marianas. The Marianas were 6,000 miles from San Francisco and 1,500 miles from Tokyo. An enormous effort was required to build airfields and satisfy the B-29’s insatiable appetite for bombs, parts, and fuel. Americans also struggled to provide the crews needed to keep the B-29’s flying. A round trip flight to Japan took twelve hours and crews were expected to fly no more than 75 hours per month. Even after that ceiling was raised to about 100 hours, the shortage of trained crews threatened to limit the effectiveness of the Twentieth Air Force.

Hanson Baldwin rightly described some of the numbers mentioned above as “the dry but eloquent statistics of the Pacific war.” The American war in the Pacific was a matter of establishing a functioning fighting system, of taking hold of all the complex and intricate war components and moving thousands of miles across the Pacific to the shores of Japan. It was all put together and transformed, again and again, in the crucible of battle.

Featured image credit: “US Navy officers at Piva Field, Bougainville c1944” by U.S. Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Conquering distance: America in the Pacific War appeared first on OUPblog.

Understanding the origin of the wind from black holes

Contrary to common belief, black holes don’t swallow everything that comes nearby. In fact, they expel a good part of the gas of the centre of galaxies. This happens when a wind of ionized gas is formed in the vicinity of the black hole. In the case of supermassive black holes that occur at the centre of many galaxies, they produce a wind that can interact with the galaxy itself shaping its evolution through time. We may say that this wind could come in two “flavours”: in form of radiation emitted from a disc before falling onto the black hole or a jet of particles launched in opposite directions perpendicular to the same disc. We know, for instance, that they keep the intergalactic gas hot and prevent the galaxy from growing bigger, suppressing star formation in most of them.

The tricky part here is how these winds efficiently couples its energy to the gas around the galactic nucleus: radiative winds basically pass through the gas and jets are too collimated to push the gas away. Since the power of these winds depends on the amount of gas that falls onto the black hole, this is an even more delicate problem when we are talking about nearby galaxies, which have much less fuel to feed the black hole. In short, we are able to explain the transfer of energy from the winds to the surrounding gas only in very specific cases, although we see its effect in a broad range of galaxies. The lack of a consistent link between the winds and the interstellar gas tells us that something is missing.

Therefore, one of the mysteries that has never been fully explained is where, why, and how these winds are formed. Because of this, we sought to answer these questions by exploring the canonical galaxy NGC 1068, the first active nucleus discovered in the sky.

By looking at NGC 1068 using archival data obtained with adaptive optics in the infrared and eight-metre telescopes of the Very Large Telescope (ESO) and Gemini North, we found that the wind is formed in two stages. In the first stage, the strong radiative wind that comes from the disc around the black hole (primary wind) impacts a torus of dust and gas, located three light-years from the black hole. This impact evaporates the torus, accelerating it outwards and ionizing part of the gas it contains.

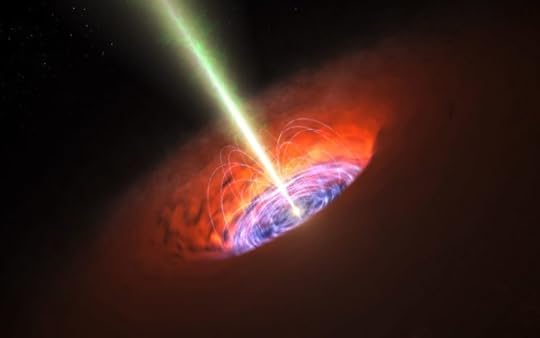

An artist’s impression showing the surroundings of a supermassive black hole, typical of that found at the heart of many galaxies. Image by ESO/L. Calçada. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

An artist’s impression showing the surroundings of a supermassive black hole, typical of that found at the heart of many galaxies. Image by ESO/L. Calçada. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The second stage of the wind formation is more dramatic and occurs when a powerful jet of particles, collimated by a strong central magnetic field, hits a large molecular cloud (made mainly of atoms of hydrogen), located at about a hundred light-years from the black hole. Without a confining surface, the jet would dissipate its energy in an almost useless way out of the galaxy, but with the energy injected in this cloud, it could be spread by means of a thermal wind (called the secondary wind), capable of blowing out the gas to even more distant regions from the nucleus.

We can compare this mechanism to partially covering a high pressure garden hose with a finger: the water would escape with a high velocity jet-like beam. If this beam hits a hard spot in the way, the water will be inevitably spread in all directions. Therefore, this second stage enables the huge amount of kinetic energy concentrated only in a narrow open angle of the jet to be re-distributed in a wider way, coming out from a region far away from the black hole. The heated gas and the thermal radiation would be blown away, accelerating the interstellar material outwards in a way that the radiative wind from the central disc would not be able to, since at these distances it would be very rarefied.

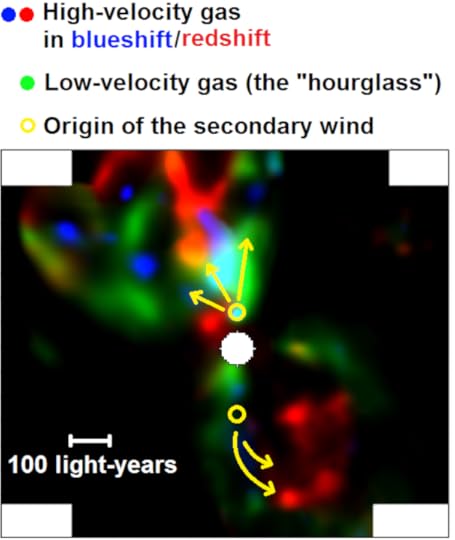

The wind formed with these high velocities is confined to the interior of an hour-glass-like geometry. The walls of this hour-glass, seen through iron emission lines, glow in the radiation emitted by low-velocity gas. However, both structures (distinguished by their velocities) have distinct reasons to present similar orientations: the walls of the hour-glass are excited by the radiation that escapes from the central disc (without accelerating them) and the high-velocity gas comes in the preferred direction from where the jet is bent and spread by the cloud. Although we may not see this specific configuration in other galaxies, the same mechanism could play a similar role in expelling the nuclear gas. This would happen when a jet hits a dense molecular material, known to be very common in the centre of all active galaxies, such as the dusty torus around black holes.

An image showing the location of the secondary wind (RGB of the iron lambda 1.64 microns emission line). Author’s own image, used with permission.

An image showing the location of the secondary wind (RGB of the iron lambda 1.64 microns emission line). Author’s own image, used with permission.The discovery of these new mechanisms fills an important gap in the understanding of galaxy formation because it shows that black holes are capable of blowing out the surrounding gas more efficiently than we knew before. Without this, virtually all the existing matter would be trapped in stars in a kind of “super-galaxy”. The Universe would be darker and colder, since stars have a limited luminous lifetime. Such black holes keep the intergalactic gas hot, which will eventually form new stars, as if we have living-galaxies slowly breathing through the cosmos.

Featured image credit: Hubble Space Telescope image of Messier 77 spiral galaxy by NASA, ESA & A. van der Hoeven. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Understanding the origin of the wind from black holes appeared first on OUPblog.

Tips for addressing stage fright

No student comes to music lessons with a “clean slate.” An argument with a parent or friend, being bullied at school, the loss of a favorite pet, a disappointing grade on a test, an illness, a friend moving out of town, a divorce in the family, and numerous other life events can interfere with the student’s learning and pleasure in making music. Such occurrences compromise a student’s ability to concentrate on work and can lower self- confidence. They also can contribute to anxiety. Often, emotional distress will be evident through a student’s performance, attendance, and attitude, particularly in the guise of chronic, often debilitating, performance anxiety and expressions of self-doubt.

Music teachers, often “first responders” to students’ emotions, are integral to students’ psychological and musical development. They are in a front row position to assist students with strong feelings so that the music student does not become overwhelmed.

There are ways to think about stage fright from multiple perspectives with a goal of both understanding anxiety and managing anxiety. Both are important. While it is not possible to totally eliminate performance anxiety, this anxiety can be transformed and better managed.

Image credit: “Full frame of text on wood” Public Domain via Pexels.

Image credit: “Full frame of text on wood” Public Domain via Pexels.Teachers can include psychological concepts in lessons, studio classes as well as in a variety of life situations. In that regard, teachers add appropriate psychological techniques to their pedagogy tool boxes. There is no perfect formula or model to use for managing the complexities of performance anxiety, but an “A B C model” can be very helpful as a teaching tool.

An A B C Model can help identify anxiety and is one important step toward recognizing feelings, thoughts, behaviors, and body sensations that raise performance anxiety. The focus here, and throughout the book, Managing Stage Fright, will be on “Letter B.”

This recognition can lead to identifying and discussing thoughts, feelings, and ego defenses (all represented by Letter B) that contribute to higher (but also lower) anxiety and stress levels.

Remember, as we discuss Letter B, that it is not the presence or absence any thought or feeling, but how feelings are understood and effectively managed that can lead to lower performance anxiety.

Let’s try an ABC example.

What Does A B C Mean?

A: Performance

B: Your thoughts, feelings, physical reactions

C: Consequences (Quality of performance and level of self-esteem based on what you say to yourself at Letter B.)

ABC Part I

Recognize your anxiety:

Think of a stressful performance.

What did you say, think, feel? (letter B)

Rate your anxiety (from 0-10).

ABC Part II

Rethink your anxiety:

Think of a stressful performance.

What did you say, think, feel? (letter B)

Rate your anxiety (from 0-10).

Challenge “B” (statements, feelings, ego defenses – see examples below)

Re-rate your anxiety

Was your anxiety lower after you challenged your Letter B responses? (You will need to do this quite often and regularly as you become more tuned-in to yourself and your feelings – Letter B.)

After completing Part I, the teacher can help students identify Letter B responses of which they are unaware and how they may have led to a higher level of anxiety.

At first, the teacher points out how the student used unhelpful–not bad (anxiety-raising)–statements at Letter B.

Then the teacher can offer a range of supportive self-statements to substitute at Letter B.

For example, students could be asked to think about anxiety-raising responses and then generate anxiety–lowering statements (Letter B). Consequently (with mental practice as important as instrument practice), students can become tuned-in to how they use their mind regarding their emotional reactions to performance. Gradually, this will lead to an increased sense of personal control over anxiety.

Examples of initial responses for Letter B (which may raise anxiety.)

I am afraid I will have a memory slip and forget my music.

I do not want to look stupid if I mess up.

I do not play as well as my friend plays.

I am ashamed if I make mistakes in a performance

The audience will laugh at me.

I want to play as well as my friends do.

Examples of revised responses for Letter B (which may lower anxiety.)

I have prepared and practiced intelligently.

I have good reasons to believe I will perform well.

It is time to trust myself.

I cannot guarantee everyone will like my playing, even

when I play my best.

I will do my best.

The audience is coming to support me.

The audience is not coming to judge me. I must not judge myself.

I need not compare myself with anybody else.

Everyone plays differently. It is important to be myself.

Letter B and Ego Defenses

While the ABC Model is often used to identify thoughts, feelings, and behaviors on a cognitive (knowing/awareness) level, this Model can also be used to identify and modify ego defenses for a deeper level of the mind.

The ego is part of the psychological organization of the mind, a source of energy, and serves as a mental buffer zone between the conscious (thoughts and feelings of which one is aware) and the unconscious (thoughts and feelings of which one is unaware). The ego is also the mental mediator/ referee between one’s external and internal life. The ego is an important “moderator” of feelings, behavior, and self- concept. The ego is not a part of one’s biological anatomy. The ego’s primary function is to provide emotional adaptation (ego defenses) both to life in the outside world and to cope with thoughts and feelings that live deep inside the mind.

As an example in everyday life, when people know that weighing too much (Letter A) may lead to high blood pressure and other health hazards (Letter C), people typically “defend” (take care of) themselves with diet, exercise, and, at times, with medication (Letter B.) However, some people do not take the steps necessary to ward off potential illness. Some people put risk aside, or think “I’ll get around to this at another time,” (Letter B) or convince themselves, “I’m not going to get sick. I feel fine” (Letter B). When an underlying physical or emotional condition is not acknowledged seriously and dealt with appropriately, it will be repeated, and unfortunate consequences may be experienced.

Some people would prepare carefully (adaptive/helpful ego defense–Letter B.) Others may think that hard work is not necessary because “things usually turn out all right” (maladaptive/unhelpful ego defense–Letter B.) Sometimes things do turn out all right. Luck can be mercurial. To put something “scary” out of one’s mind does not make it go away. This form of denial (an ego defense–Letter B) actually increases the probability that the recital or audition will not turn out all right.

What are some ways performers can use ego defenses?

Projection: The belief that other people are thinking something (usually uncomplimentary) about you. (Example: “If I have a memory slip, the audience will not like me.”)

Rationalization: An attempt to minimize or explain away a thought or feeling, typically using common sense. (Example: “I was late to school because I had to make my lunch.”)

Denial: Believing that something does not exist. (Example: “I bet my teacher won’t choose me to play in the recital.”)

Reaction formation: Saying or feeling the opposite of what one really thinks or feels. (Example: “I don’t know why everyone else freaks out about performing. I am pretty relaxed about it.”)

Isolation of affect: The inability to experience or acknowledge feelings so that one talks about a highly charged topic with little or no emotion. (Example: “I had a memory slip in the last recital but that does not bother me.”)

By now you probably are getting the idea that it helps to become aware of your ego defenses and to use them adaptively. Identifying your ego defenses, or Letter B responses, and challenging unhelpful feelings, can help lower your performance anxiety.

It is not a big leap to realize that for performance anxious musicians, a fragile self is on the firing line every time they appear on stage. For performers who measure self- love primarily from external sources (audiences, teachers, parents, friends), positive self- esteem is predominantly obtained through others’ approval and applause. There is difficulty in believing in your self-worth without the roar of the crowd, which hinges on some performers’ beliefs that they can control the crowd through a brilliant, sensitive, and technically “perfect” performance. That is scary – you cannot manage others. But you can better manage yourself. Such attitudes, or ego defenses and self-statements (Letter B) typically raise anxiety.

So take some time to think about how statements can be friends or foes when you feel stage fright. Teachers are in an ideal position to help students do this. Performance anxiety can be managed much better when feelings as well as your music as better managed. Remember, too, you manage your stage fright over the long haul – you may not realize the progress you are making from day to day. It all adds up if you keep adding.

Good Luck–I’d love to hear from you.

Featured image credit: “Changsha concert hall stage” by kailingpiano, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Tips for addressing stage fright appeared first on OUPblog.

July 31, 2017

Curing (silent) movies of deafness?

Conventional wisdom holds that many of the favorite silent movie actors who failed to survive the transition to sound films—or talkies—in the late-1920s/early-1930s were done in by voices in some way unsuited to the new medium. Talkies are thought to have ruined the career of John Gilbert, for instance, because his “squeaky” voice did not match his on-screen persona as a leading male sex symbol. Audiences reportedly laughed the first time they heard Gilbert’s voice on screen. And in the case of the late silent era’s most popular female performer, the original “It girl” Clara Bow, a voice sometimes described as a “honk,” along with a strong Brooklyn accent and careless diction are often said to have forced her into retirement at the relatively young age of twenty-eight.

The real issue, however, was less the voices than the essence of the art. Despite our early-twenty-first century use of the word “movie” to refer to any cinematic production, silent movies and talkies differed substantially. Where talkies relied upon spoken words to communicate plot, ideas, and emotions, silent movies communicated visually using, as the name suggests, pictures that moved. In short, as seeing differs from hearing, so too movies differed from talkies.

The essence of silent movies was visual. As one observer at the time put it, in silent movies “People are doing something. We see them do it; even if they are only thinking or feeling…, we still see it.” Writing a movie column for a Chicago newspaper in the 1920s, Carl Sandburg marveled especially at actor Charlie Chaplin’s ability to convey complex ideas and emotions “with shrugs, smiles, solemnities, insinuations, blandishments.” Chaplin’s visual “sentences” were so “alive with gesture and intonation,” that Sandburg—one of the great American writers—could not imagine “reproduc[ing] any story Charlie Chaplin tells verbally.”

The visual nature of silent cinema made it particularly interesting to deaf Americans, for whom visual forms of communication were more natural than audible ones. In fact, historian John Schuchman argues that the silent movie era “represents the only time in the cultural history of the United States when deaf persons could participate in one of the performing arts with their hearing peers on a comparatively equal basis.” Alice T. Terry, a leading figure promoting a uniquely Deaf cultural viewpoint in the early-twentieth century, explained why: “[T]he movies [are] pre-eminently the place for pantomime or signs;” they have “no use for speech and lip-reading.”

Lon Chaney and Mary Philbin in the 1925 silent movie The Phantom of the Opera— although the “grisly mask” he wore limited his facial expressiveness, “Chaney’s best acting, with his hands, is to be seen in this picture,” according to reviewer Carl Sandburg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Lon Chaney and Mary Philbin in the 1925 silent movie The Phantom of the Opera— although the “grisly mask” he wore limited his facial expressiveness, “Chaney’s best acting, with his hands, is to be seen in this picture,” according to reviewer Carl Sandburg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.On the other hand, deaf Americans in the late-1920s understood better than anyone the vulnerability of visual, non-verbal and non-audible, forms of communication confronted by the forces of normality. Beginning after the American Civil War, a number of individuals interested in deaf education—people such as telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell—stressed the need to eliminate sign language and other visual/manual forms of communication from the nation’s deaf schools in favor of teaching verbal/audible communication in English. At the risk of over-simplification, their reasons—which included evolutionary theory, eugenics, and assimilation—boil down to an assertion that oralism could effectively cure deafness enabling deaf people to live more effectively in “the normal world.”

By the end of the 1920s—a decade famously proclaimed an era for “normalcy” by then presidential candidate Warren G. Harding—the oralist triumph in deaf education was nearly complete. According to data compiled in 1928, over 90 percent of deaf children received some or all of their education via oral methods and just two exclusively manualist schools remained (both were segregated institutions for the African American deaf). Oralists were much less successful reaching people outside the classroom, however. Sign language stayed alive in the Deaf community until the pendulum swung back in the manualist direction later in the twentieth century.

The normalizing attitudes and beliefs that underpinned oralist efforts in deaf education also afflicted ideas about modes of communication at the cinema. Even before talkies became a reality, the world depicted in silent movies was being described as “a dessicated [sic] and dehumanized world, from which all intrinsic worth has departed.” Similarly, the premiere of The Jazz Singer (1927)—widely considered the key film in the transition to talkies—was hailed at the time as “an upward step in [human] racial development which is dependent, absolutely, on the arts of communication.” The silent productions which continued to be produced during the next few years soon began to be referred to as “dummies” or “dumbies.” This, of course, recalls a common slur directed at deaf people, implying that a lack of oral and audible communication was connected to a lack of intelligence.

As in deaf education, the shift from movies to talkies met resistance. Charlie Chaplin was the most prominent resister, insisting that “I can say far more with a gesture than I can with words” and vowing “never [to] use dialogue in my pictures.” “It stands to reason,” added “It girl” Clara Bow, “that you can’t act as well when you have lines to think about, particularly those of us who have never been trained to talk while we act.” No less a movie authority than inventor Thomas A. Edison concurred, lamenting that because talkies required actors to “concentrate on the voice” they had “forgotten how to act.”

Nevertheless, within three years of The Jazz Singer’s appearance, virtually all new production of silent movies in Hollywood ceased. Eventually even Chaplin relented and began using audible dialogue to tell his filmed stories—though not until 1936. In the years since, only The Artist (2011) stands out as an attempt to make a true movie, where the pictures and actions of the performers, rather than their spoken dialogue, tell the story, but even the success of that Academy Award winning picture has not spawned copycats.

The movies had been cured of their deafness—or at least taught to “talk like living people,” as an advertisement for one theater sound system put it—but at what cost?

Featured image: Joyce Compton and Clara Bow in The Wild Party. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Curing (silent) movies of deafness? appeared first on OUPblog.

Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor: an audio guide

In this Oxford World’s Classics audio guide, listen to Robert Douglas-Fairhurst of Magdalen College, Oxford University–who edited and selected this new edition–introduce Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor.

‘London Labour and the London Poor’ originated in a series of articles for a London newspaper and grew into a massive record of the daily life of Victorian London’s underclass. Mayhew conducted hundreds of interviews with the city’s street traders, entertainers, thieves and beggars which revealed that the ‘two nations’ of rich and poor were much closer than many people thought. By turns alarming, touching, and funny, the pages of ‘London Labour and the London Poor’ exposed a previously hidden world to view.

Listen to this audio guide to learn more about Henry Mayhew and his writing, Victorian society, and the slums of London.

Featured image credit: “London” by dirwiki CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor: an audio guide appeared first on OUPblog.

July 30, 2017

A research journey from jungles to genomes

As the small propeller plane came in towards the airstrip, we could see the flat plains stretching away ahead of us, and the forested slopes of the Andes passing below. This was Villa Garzón, in the province of Putumayo, a remote corner of Colombia with a turbulent history. Until recently the Amazonian fields and forests stretching ahead of us were prime cocaine growing territory, and largely controlled by the FARC guerilla group—definitely not recommended for tourists or biologists alike. However, the recent peace accord signed in Colombia between the government and the FARC offered a new hope for peace across the country, as well as an opportunity for adventurous biologists to visit previously inaccessible parts of the country.

One of the goals of our trip was to search for a butterfly called Heliconius tristero (or Heliconius timareta tristero as it is now more correctly known), which had been described in 1996 from just two specimens collected in this area. Almost anyone who has visited the jungles of tropical America is likely to be familiar with the ‘postman’ or Heliconius butterflies. With their slow flight, brilliantly coloured patterns and long rounded wings, they are a prominent and highly visible member of the jungle community. They are generally well studied, so it was unusual to find a new species, and especially one known from so few individuals. Only one biologist had successfully collected this species since, and we were hoping to confirm its existence.

Image provided by the author. Used with permission.

Image provided by the author. Used with permission.So, after checking into our hotel in the town of Mocoa, we soon headed out into the nearby mountains in search of tristero. And after a short hike into the forest, we were rewarded almost instantly. Our Colombian collaborator Mauricio Linares was the first to get lucky, but soon we had netted several specimens. A few were preserved for genetic analysis, the remainder carefully kept alive in order to establish a population in the laboratory for future studies. It turns out that tristero is not that rare once you can get to the right place. Peace in Colombia, probably the most biologically diverse nation in South America, is a good thing for biologists as well as everyone else in this remarkable country.

What is surprising about tristero is that it is a remarkably close mimic of its close relative, Heliconius melpomene. Indeed, one reason why the species had remained hidden until 1996 was not just its inaccessible home, but also the fact that it was only recognized as a distinct species from its close relative melpomene using DNA evidence. Heliconius are famous for this mimicry – different species evolve similar wing patterns to tell predators that they are poisonous to eat. ‘Stay away from us’ these species are signaling – we are all packed with toxins. Different species benefit from sharing a pattern by sending a common signal of their nastiness to predators. In Heliconius, most mimicry occurs between relatively unrelated species – distant cousins if you like, rather than brothers and sisters. Tristero was the first of a series of populations recently discovered along the eastern edge of the Andes in which there is mimicry between very close relatives. However, although it was the first to have been discovered, tristero remains the least well studied of these populations due to the inaccessibility of the Putumayo region.

Image provided by the author. Used with permission.

Image provided by the author. Used with permission.Despite their recent discovery, these butterflies found in remote Andean valleys have rapidly become evolutionary celebrities. It turns out that they have evolved mimicry by a rather sneaky means. Mostly we think of evolution as occurring through the chance process of mutation generating random changes, followed by exhaustive winnowing of these (mostly harmful) mutants by natural selection. What if a population could bypass this rather tiresome process of sorting through random errors to find adaptive genetic variants? It turns out that these butterflies have done just that, by borrowing genetic material from their close relatives. Occasional mistakes in choosing mates mean that closely related species occasionally produce hybrids, and these rare hybrid individuals can provide a route for genetic exchange between species. This allows genes for wing patterns to move between species, leading to the rapid evolution of mimicry.

These discoveries have relevance to our own species. It turns out that humans, much like the butterflies, have also acquired genetic material from close relatives, in this case our now extinct cousins the Neanderthals. This genetic material has helped people live in extreme environments such as the high mountains of the Himalayas, and may have a role to play in genetic disease. The study of butterflies from remote corners of the world has helped to shed light on our own origins. These unexpected coincidences, the discovery of common processes across the diversity of life, provide an important motivation for biological research driven by pure curiosity. But in an increasingly globalized world, there is also just a thrill in exploring obscure corners of the globe where few biologists have travelled. Right now, we are sequencing the genomes of those tristero specimens collected in Colombia in January, and we will soon be able to confirm whether they acquired their gaudy colours in the same way.

Featured image provided by the author and used with permission.

The post A research journey from jungles to genomes appeared first on OUPblog.

What Mubarak’s acquittal means for Egypt

On 13 March 2017, the legal saga of the trial of Hosni Mubarak ended. The deposed autocrat, who was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for his complicity in the killing of hundreds of demonstrators and embezzlement on a grander scale, was acquitted by Egypt’s Court of Cassation and freed from his detention. “The trial of the century”, as Egyptians have dubbed Mubarak’s prosecution, began soon after millions of Arabs took to the streets all over the Middle East, and it was concluded against the backdrop of the deep frustration of most from the results of the Arab Spring. This legal ordeal is but one prominent manifestation of the decisive role that the legal system played during the struggle over the reign of power following the toppling of Mubarak.

Mubarak’s trial symbolizes the deep divide between the revolutionaries who demand a fundamental change, and those who support the continuation of the regime that the ousted president inherited from his predecessors, Anwar Sadat and Gamal Abd al-Nasser. The latter, who led the Free Officers coup (23 July 1952), strove to establish a democratic system of government that raised the banner of equality and justice. Their social and political achievements notwithstanding, Nasser and his confederates laid the foundations for an authoritarian government that would reign well into the next century.

During the transition stage of the July Revolution, the government made intensive use of decrees, laws, and constitutional declarations. Two special courts, conferred with exceptional powers, prosecuted more than one thousand of the junta’s opponents—the majority of whom were members of the Muslim Brothers, but also liberals and communists. Although the Revolution’s Court and the People’s Court were dissolved at the end of the 1950s, the long-standing Egyptian practice of adjudicating citizens before special tribunals would reach new heights in the decades to come. The widespread use of these tribunals, including the military variety, turned this exception into the rule.

Portrait election 2005 Hosny Moubarak by Papillus. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait election 2005 Hosny Moubarak by Papillus. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.As the popular uprising against Mubarak gained momentum, a riveting public discourse took shape in Egypt that compared the revolution of July 1952 to that of January 2011. In both cases, a strongman’s ouster raised hopes among many Egyptians that a “new beginning” was just around the corner. Additionally, each of the attendant transition phases was undergirded by the following developments: a military council assumed control over the daily running of the state; a national state of emergency was declared; and a fierce political struggle erupted over the contours of the new dispensation. What is more, the acting governments took extraordinary measures, foremost among them suspending the constitution and disbanding parliament. Similar to the July Revolution, the judicial system and the courts have indeed loomed large in the on-going struggle over the new dispensation, including summarily arresting over 30,000 political rivals. Many of the detainees were ultimately prosecuted by military courts, which meted out harsh punishments on them.

Six years after the impressive civil uprising that demanded “the overthrow of the regime,” Egypt under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi allegedly reflects the complete return of the authoritarian regime. However, the 2011 popular uprising and the toppling of Mubarak were just the beginning of a transition phase, the fate of which no one can predict. On the very day of 14 July 1789, when the Bastille was taken, or on 23 July 1952, when King Faruq was ousted, no one could have known that a Great Revolution was born in France, just as a revolution in Egypt.

All told, the January Revolution jolted the political awareness of millions of people from different walks of life, not least Egyptian Millennials. Many of them oppose the restoration of the authoritarian regime and fear that President Sisi is but a contemporary pharaoh. Although the field marshal’s meteoric rise to power constitutes a major milestone, it is doubtful that this was the last tidal wave of the January Revolution.

The current dramatic developments in Egypt show that political trials that take place throughout a transition phase generate rhetoric that plays a crucial role in the denouement of political struggles, nourishes the creation of new historical narratives, and help shape both the regime and opposition’s public image.

Featured image credit: Egypt-8A-090 by Dennis Jarvis. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What Mubarak’s acquittal means for Egypt appeared first on OUPblog.

Friendship in Shakespeare

Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears …

In Shakespeare’s England, the term “friend” could be used to express a wide range of interpersonal relations. A friend could be anything from a neighbour, a lover, or fellow countryman, to a family member or the close personal acquaintance we understand as a “friend” today. Much like power or love, different types of friendship are one of the central themes in Shakespeare’s plays, dealing with the positivity of close and trusting friendships, but also with its fragility and the resultant dangers when trust breaks down.

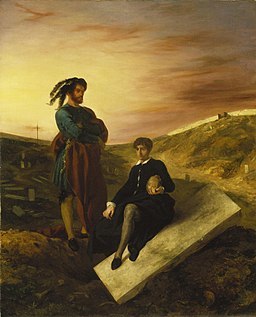

Being a true Shakespearean friend means above all loyalty, unwavering support, and mutual respect– clearly shown in the relationship between Hamlet and Horatio. Horatio is Hamlet’s one true ally and stands by the tragic Prince throughout his troubles, going so far as to offering suicide for him . This tragic conclusion seems to be a pattern for many Shakespearean friends, revealing the darker side of human relationships. Some of the most famous villains are the ones who betray their nearest and dearest friends, indicating that unwavering trust and friendship, like the trust Julius Caesar places in his friend Brutus until the very end, can be easily misplaced.

Image credit: Eugène Delacroix: “Hamlet und Horatio auf dem Friedhof”, 1835 from Städel Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Eugène Delacroix: “Hamlet und Horatio auf dem Friedhof”, 1835 from Städel Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.From the most uplifting displays of platonic affection, to tragic endings, and comic capers, Shakespeare explored the concept of friendship in almost all of his plays. With this in mind, we have collected some of his most memorable quotations on friendship. Which would make your list?

In Act 2, Scene 1 of Much Ado about Nothing, Claudio contemplates friendship, and its relation to matters of the heart:

“Friendship is constant in all other things, save in the office and affairs of love”

Ulysses speaks with Achilles on the transience of human relations in Act 3, Scene 3 of Troilus and Cressida:

“Love, friendship, charity, are subjects all

To envious and calumniating time”

In Act 3, Scene 7 of 1 Henry VI Charles the Dauphin heartily welcomes the “Bastard of Orleans” in a scene reminding us of the strength friendship can give:

Charles the Dauphin: “Welcome, brave Duke! Thy friendship makes us fresh”

Bastard: “And doth beget new courage in our breasts”

Miranda speaks to Ferdinand (to whom she is later betrothed) on the romantic side of companionship, in Act 3, Scene 1 of The Tempest:

“I would not wish

Any companion in the world but you;

Nor can imagination form a shape

Besides yourself to like of”

The Duke of Bolingbroke recalls the power of platonic love amongst friends, after Harry Percy declares his loyalty to him in Act 2, Scene 3 of Richard II:

“I count myself in nothing else so happy

As in a soul remembering my good friends;

And, as my fortune ripens with thy love,

It shall be still thy true love’s recompense”

Timon of Athens speaks to his guests on the concept of “true friendship” at the banquet in Act 1, Scene 2 of the eponymous play:

“Ceremony was but devised at first

To set a gloss on faint deeds, hollow welcomes,

Recanting goodness, sorry ere ’tis shown;

But where there is true friendship, there needs none”

Parson Evans and Doctor Caius (previous antagonists and duellers) bond over a common adversary in Act 3, Scene 1 of Merry Wives of Windsor:

“I desire you in friendship, and I will one way or other make you amends”

Featured Image Credit: “Stamp – inked from Folger Shakespeare Library” uploaded by POP,CC BY 2.0 via Flickr .

The post Friendship in Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

What sorts of things are the things we believe, hope, or predict?

It is part of our everyday life that we ascribe beliefs, desires, hopes, claims, predictions and so on to other people and ourselves, and the ascription of such propositional attitudes, as they are called, generally takes a canonical form, of the sort John believes that Macron is president of France, Mary hopes that Macron is president of France, and Joe predicted that Macron would become president of France.

Painting by Ganna Kryvolap.

Painting by Ganna Kryvolap.Propositional attitudes appear to involve objects. They are the things that that-clauses seem to stand for and that we make reference to when we talk about ’what John believes’, ‘what Mary hopes’ and ‘the thing Joe predicted’.

But what sorts of things are these attitude-related objects? Clearly, they are representational objects that can be true or false or be fulfilled or not. What John believes can be true or false and what Joe predicted can be fulfilled or not.

The things associated with propositional attitudes, moreover, seem to be able to be shared among different agents. John can believe, hope or predict the same thing as Mary, and John and Mary can both have the belief that Macron is president of France or make the prediction that Macron would become president of France.

While philosophers agree on what sorts of properties the things associated with propositional attitudes should have, there is great disagreement about the nature of those things. The dominant view in contemporary philosophy of language is due to the philosopher Gottlob Frege, who around 1900 argued that the things associated with propositional attitudes are abstract, mind-independent objects that come with truth conditions, abstract propositions.

But then how can we when we think, hope, or predict relate to such propositions and mentally grasp them? And how could propositions as abstract objects represent and be true or false? After all mathematical objects cannot do that.

A different approach to propositional content has recent been pursued by a number of contemporary philosophers. According to that approach, propositional contents are intimately related to our mental life. Propositional contents on such an approach are identified with types of mental acts or states, with types of features of mental acts and states or with products produced by mental or linguistic acts. Such an act-based approach to propositional content has become a central topic of discussion in contemporary philosophy of language.

However, the act-based approach is in fact not a new approach to propositional content. It was an equally important view pursued during Frege’s time and before, by philosophers such as Bolzano, Husserl, Reinach, Meinong, and Twardowski. It was pursued in particular in parts of Eastern Europe, for example in the city of Lvov, where Twardowski, one of the main proponents of the approach, lived and taught. It is important and exciting to revisit that approach in view of the contemporary debate, to learn from it and to give it justice and recognition.

The paintings of Lvov and of New York on the cover of the book represent a historical and a contemporary center for the pursuit and discussion of the act-based approach to propositional content.

Painting of by Lvov by Ganna Kryvolap.

Painting of by Lvov by Ganna Kryvolap. Painting of New York by Ganna Kryvolap.

Painting of New York by Ganna Kryvolap.Featured image: painting by Ganna Kryvolap.

The post What sorts of things are the things we believe, hope, or predict? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers