Oxford University Press's Blog, page 342

July 26, 2017

Etymology gleanings for July 2017

First of all, I would like to thank our readers for their good wishes in connection with the 600th issue of The Oxford Etymologist, for their comments, and suggestions. In more than ten years, I must have gone a-gleaning about 120 times. I also appreciate references to the sources I either missed or may have missed. As far as the origin of numerals is concerned, I should say that the bibliography of each is a bottomless pit. Just for comparison: in my database, there are 92 items for five, 70 for ten, 45 for eight, and so on. Old periodicals are also countless. I followed Stephen Goranson’s hint, and one of my faithful volunteers has screened The Athenian Oracle. Unlike The British Apollo, it yielded nothing related to words or idioms. The Athenian Mercury is still hanging fire.

In my mid-June etymology gleanings, I wrote that the term schwa had been first used in Indo-European studies by Eduard Sievers and not by Jacob Grimm, as Wikipedia stated, and I was delighted to see that the mistake had been corrected, with the reference to that post. And as long as I am dealing with schwa, I must say (in response to a question) that no, schwa is not directly responsible for the off-putting appearance of some Polish words and names. But yes, in Polish, unstressed vowels were lost in some syllables, and this circumstance resulted in the emergence of heavy consonantal clusters.

Singular or plural?

I had no doubt that the sequence one of the things that evoke my anger will not evoke anyone’s wrath, because I had polled many people about it. Only my spellchecker and I are unhappy about it. To begin with, let me repeat one of the most hackneyed theses of historical linguistics and usage. That is correct which everybody finds acceptable. Take the famous English construction “preposition at end,” for instance, he is the man we talked to. To cannot go with he, because after a preposition we need him, and yet they are certainly linked. To make this case even harder, we note that there is no collocation talk to like the idiomatic give up (compare: this is not a case to give up). Parsing that sentence is a nightmare. Do speakers care? They certainly don’t. As if to mock us, English has the noun talking-to, and it does not mean “conversation,” but rather “a sharp reprimand.”

A crossroads. Singular or plural?

A crossroads. Singular or plural?Such examples are many. Is it correct to say I insist on Bob or on Bob’s answering my question? English speakers, who don’t read grammar books and even those who do, are perfectly happy with both variants, which means that both versions are “correct.” Old Icelandic allowed the doubling of prepositions, and occasionally I hear something like that’s the guy about whom we were talking about. So in Old Icelandic it was “correct,” while in Modern English it probably isn’t. Why? Who and whom, lie and lay are such old chestnuts that I’d rather not say anything about them here. Consequently, if the mood of the tales are gloomy is acceptable to most (moderately) naïve American speakers (as, seemingly, it is), then the norm should bow to this innovation and formulate the rule: “Allow the verb to agree with the word closest to it.” May editors and teachers rage and fight a losing battle, if they choose to do so. I can only repeat my favorite statement: “It is most interesting to study the history of language, but it is disgusting to be part of it.”

To return to one of the things that evoke my anger. Despite the ambiguity, I am sure the antecedent of evoke is one, not things. The sentence John is one of the people who are… poses not difficulties: of course, are refers to people! An acid test of your conviction is the position you will adopt as an instructor of English as a second language. It is easy to be open-minded at home. But if your student (from Germany to China) asks you about that sentence with evoke, what will you say? Both are correct? One is preferable? One is wrong? I’ll be happy to read your comments.

Ablaut

Sneak-snuck is a “famous” example. See my old post for 14 November 2007: “Sneak—snack—snuck” and the comments following it (dig is also mentioned there; I doubt its French origin). Those around me (the American Midwest) seem to favor snuck. But this form says little or nothing about the productivity of ablaut; at best, it testifies to the power of analogy: sneak-snuck as strike-struck. The same holds for crank–crunk cited in the comment (the model is drink-drunk). In all the Germanic languages, strong verbs (that is, such verbs as follow the model of ablaut) tend to become weak; hence dived rather than dove, and compare thrived–throve. Very rarely, weak verbs (of the liked, begged, wanted type) go over to the strong class: snuck is such a pseudo-strong verb. But “productive” presupposes a living model. Suppose that you have never heard the verb wive. It won’t occur to you that its past tense is wove, even though you know drive-drove and perhaps say throve and dove. The same holds for my examples in the previous post: brolly, wodge, and frosh. Those are occasional humorous formations; yet ablaut remains unproductive.

She [or he] put on a pair of new sneakers and snuck away.

She [or he] put on a pair of new sneakers and snuck away.Cognates and borrowings

Engl. know and words like gnosis are related, that is, they are congeners, or cognates. They share the same Indo-European root, but each word has its history in its own language. The Latvian examples cited in the comment on hundred are more complicated. Last week I decided to stay away from the situation in Baltic. Let me return to my examples. Latin centum is akin to Germanic hund-, and, as far as the consonants are concerned, the correspondence is clear: Germanic h corresponds to non-Germanic k. But the Russian for centum is sto. Why sto and not kto? The Proto-Indo-European k’, that is, palatalized k, yielded two reflexes: h in the West (as in Germanic) and s in the East (as in Russian). For this reason, historical grammars distinguish between so-called centum and satem languages. Latvian and Lithuanian are satem languages but occasionally have centum forms. Sometimes it is unclear whether we are dealing with a regular reflex or with a borrowing from a neighboring centum language. (If you decide to consult historical grammars, note that they print schwa where I have e in satem.)

From the history of the Oxford English Dictionary

Skeat wrote in 1867: “What is required in a helper is, still more than ability, the possession of patience, industry, accuracy and leisure.” And in 1890, when work on the dictionary was in full swing, Murray kept discovering gaps in his data. Here are some of his questions, slightly paraphrased. “Did any one use the phrase to show the cold shoulder before Walter Scott?” “Can anyone provide quotations for trailing one’s coat-tails ‘to provoke or challenge to a fight’”? (The phrase was used in “newspaper leaders [and] extra-parliamentary speeches.”) “What men and women are said to be of a certain age?” (This is a fateful question!) Instances of blue devils “melancholy, a fit of spleen” before 1800 are needed. “A man and a brother: Where does this expression, so often quoted in connection with the slavery question, first occur”? I have no doubt that at Oxford all these materials have been stored and studied, but to those unconnected with the OED a glimpse into the progress of the great dictionary may be of some interest.

These people certainly have leisure, but will they work as helpers for the OED?

These people certainly have leisure, but will they work as helpers for the OED?Featured image credit: “Luncheon on the Grass” by Édouard Manet, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for July 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

Ivanka Trump’s sleeves (too long; didn’t read)

Unlike most English professors, I watch a lot of Fox News. Silently, assiduously, three times a week, for exactly thirty minutes. This is, as you may have guessed, courtesy of my gym, which has chosen to stream Fox News on one television screen and CNN on the other. This juxtaposition of the famously fair and balanced network with the notoriously fake news site was, in 2016, still simple viewing: on the left screen, Hillary was a great candidate, while on the right screen, Hillary was a lying deleter of emails. A single political discourse, two different forms of commentary.

Now, however, in 2017, my gym routine has become more difficult. Take last week: on CNN, Russia was scandalously embroiled in U.S. elections; on Fox News, there was a scandal unfolding about Ivanka Trump’s dress. As an educated professional confident in my grasp of contemporary politics, I nearly fell off my elliptical. How had I missed this? Was the dress blue? Would the President be impeached?

The dress in question had bows on the sleeves, which one commentator had criticized as inappropriately girly. I had, just barely, caught the great sleeveless scandal of June 2017, in which Ivanka’s arms violated established White House dress codes: I had not, despite my daily news reading, caught the decorated sleeves scandal of July 2017.

TL;DR: Ivanka Trump wears dresses with a variety of sleeves.

I mention this incident, not only to broadcast my commitment to low impact cardiovascular activities, but to explain how literary studies may need to be reworked for the U.S. in 2017. Our field has generally agreed about the centrality of two things:

1. The ongoing importance of close reading

2. The significance of discourse analysis

Are these, however, still true in 2017?

There is now arguably a U.S. discourse around sleeves, and there is certainly plenty of semantic richness and cultural history. Discussing the dresses of Presidentially proximate women has been, in the States, a well-established pastime. The problem is not that such discussions are trivial distractions – or as we now call it, covfefe – but that close analysis and discourse networks may be irrelevant. Comments on sleeves are simple statements, and thus more suitable for surface reading than for seeking their analytic depths. They gain their significance, not as part of an interlocking network of discursive enunciations: there are no longer two sides to every story, but rather seemingly disconnected, serially delivered anecdotes in at least two different takes on every happening.

TL;DR: Please, no manifestoes for “sleeve reading.”

I could have–and probably should have–spent my sleeve-study time reading more about the Russia investigation. Certainly, in the established genre of legislative testimony, one can still rely upon literary studies skills. We can debate what it means when the President of the United States says to the Director of the FBI, “I hope you can let this go.” Can hope count as a directive, or is it too ephemeral to constitute a criminal action?

But I didn’t finish reading James Comey’s testimony. As the kids say, “TL;DR”: it was too long, so I didn’t read. And, in any case, like most English professors in the United States, I’m already affiliated to one of the nation’s two political teams (“Go Donkeys!”). Keeping up with the latest political developments is now, for better or worse, an amusing, affiliative hobby.

The TL;DR of my response to Comey may be akin to the TL;DR of the student who stops reading Hamlet midway, confident that all major plot details have already been apprehended.

TL;DR: In the end, everyone dies.

In a year when U.S. news has become endlessly, unpredictably entertaining, reading is first a matter of selection, and only then an issue of interpretation.

Like our students, we scholars don’t always finish our reading–but unlike our students, we are professionally cultivated in the crucial tasks of deciding what to read and how to read it. We don’t close read everything (and we distant read even less): sometimes we underline, but often we skim, and more often than we wish to admit, we say we’re going to read something and never get around to it. Our personal lists of things left unread get larger with every day of close and careful reading.

It is only in the classroom, today, that we insist that each text must be read carefully, closely, and completely. Many of us already utilize a tacit ICYMI (“in case you missed it”) mode for class discussions: outlining the plot, noting the major arguments, getting all students on the same page whether or not they finished the reading. We might better equip our students if we openly discussed TL;DR instead, thereby acknowledging not only the great unread but the existence of a wide variety of reading modes, always working in concert with our cherished close reading.

We can bring TL;DR into the classroom as a research method: a means of determining, as we already do, what is worth reading, and how it should be read.

TL;DR: I’m very interested in what you didn’t read.

(Yes, I could have written this without mentioning Ivanka – but I just want you to think about TL;DR, not experience it upon encountering my piece.)

Featured image credit: Ivanka Trump by Marc Levin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ivanka Trump’s sleeves (too long; didn’t read) appeared first on OUPblog.

The misunderstood Irish composer

Composer/pianist John Field’s birthday serves as a reminder of the uncertainty that underpins his reception. On the twenty-sixth of July, we ostensibly celebrate Field’s birthday. Whether he had been born the day before or after makes little difference; I only highlight it here to demonstrate the extent to which numerous oversights have significantly altered our perception of Field. It throws into question then, how much do we really know about the Irish-born musician as he turns 235?

Extant cameos of Field paint the following pictures: a man who composed only when necessary and it tended to be last-minute; someone who rose to the challenge due to talent; a composer, despite this talent, that had compositional weaknesses which he never overcame due to his care-free nature, personal recognition of which came in the guise of continuous revision; a comedian more interested in alcohol and women than his job; a boaster who rested on his laurels; a renowned pianist who visited but stayed in Russia because of a disagreement with his former master Clementi; and a musical figure whose memory has been kept alive because he was fortunate enough to have ‘created’ the nocturne, and even more fortunate that Chopin is considered his successor in this genre. These are the images that emerge, where not unlike gossip, hearsay is misconstrued for evidence, and biographical detail is attractive; it makes the genius and successful seem more human.

That anecdotal material, primarily centred on Field’s life rather than his music, has gained so much currency in Field studies is perhaps in part because he spent most of his life in Russia, notwithstanding that there is little surviving correspondence from the composer, who doesn’t appear to have kept a diary. Substantial reference to Field in newspapers only comes towards the end of his career, when he returned to Western Europe for a tour, and having been absent from the West for so long–despite his works being published widely throughout Europe–he was deemed an enigmatic figure. It is hardly surprising then that reports on Field would have been approached with a certain curiosity and expectation. So what should we remember about Field on his birthday, and why should we remember it?

Field composed seven piano concerti, which was a very healthy number at this time, and it was the concerto genre for which he was initially known. He also wrote four sonatas, a quintet, and various other short pieces. The widely disseminated editions of Field’s nocturnes suggest that he composed 18, yet only 14 of these were specifically labelled nocturnes by Field. He was one of the most popular pianist/composers in the early nineteenth century and was performing and writing during an important time in the piano’s development. Similar to the multi-tasking musician today, Field was expected to cater for various audiences and although sparse, any surviving letters to and from Field shed light on a composer who had foresight, worked diligently, and responded to the musical market. While he did revise works a lot this had less to do with acknowledgement of so-called compositional weakness–he wrote very much in the style of the day–and more to do with nineteenth-century practice: issues of copyright and awareness of posterity were important factors at this time, and scholars believe that revisions may be attributed to them. Field may have remained in Russia to act as a piano salesman for the Clementi pianos rather than arguing with his old master. In terms of last-minute composing, he was undoubtedly talented, and could’ve been eccentric too, but these weren’t the only two ingredients that got him by; he worked hard!

Image credit: “John Field” by Carl Mayer, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “John Field” by Carl Mayer, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.It would be unfair to focus solely on the shadows that have been cast over Field’s reception however; even the positives are not beyond questioning. For example, his accolade ‘inventor of the nocturne’ has long been challenged and could be equally given to one of his contemporaries, Dussek for example, who was writing in this style even before Field. Nevertheless, unlike his contemporaries Field continued to compose nocturnes throughout his career. From this perspective, it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to refer to him as the Father of the Nocturne in the same way that Haydn is considered the Father of the Symphony, i.e. Haydn didn’t create the symphony but he did compose a lot of them and contributed greatly to its form.

Oversights are not unique to Field scholarship but somehow issues that are equally pertinent to other composers seem to be teased out in a reasoned manner. Elsewhere, memoirs of those who met Field are cited uncritically despite being highly romanticised and edited. Although we cannot verify or deny them, looking at Field primarily through these lenses is becoming increasingly difficult to uphold. At the same time, Field has not fared too badly considering that many of Field’s contemporaries have been forgotten. Ironically, it is because of unchallenged misconceptions that Field has secured a position in music history as the creator of the nocturne, which in turn has fortunately provided a route into exploring his compositional output and life.

The point at which one should verify and challenge information, and whether Field would have had a very different position in history as a result, brings to mind Milan Kundera’s Unbearable Lightness of Being: “human life occurs only once and the reason we cannot determine which of our decisions are good and which bad is that in a given situation we can make only one decision; we are not granted a second, third, or fourth life in which to compare various decisions”. And so, on 26 July 2017, I am reminded of John Field, his nocturnes and concerti, and how various readings of his many receptions demonstrate first and foremost how diverse music is, but most importantly what we can learn through music on a societal, cultural, national, historical, philosophical, and personal level. Happy Birthday John Field; thank you for these journeys!

Featured Image credit: plaque on a stone monument commemorating Field’s birth at Golden Lane. Majella Boland, used with permission.

The post The misunderstood Irish composer appeared first on OUPblog.

The legacy of Stanley Kubrick and the Kubrick Archives

Stanley Kubrick would be 89 this year. It’s quite possible were he still alive that he would have made more films. At his death in 1999, he left a legacy of just twelve works of extraordinary cinema, as well as a few interesting early short films. This is a small output by the usual standards of filmmaking, but it reflects the intensity of care that went into each film and his willingness to abandon a project if he could not get funding for it or could not get a working script—as was the case for his Holocaust project, Aryan Papers, and his science fiction film, A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, which was subsequently made by his friend, Steven Spielberg.

The extraordinary thing about the past 18 years since Kubrick’s death is that his reputation has grown, interest in his films is as strong as it has ever been, and critical writing about his films is not only on the increase, but has taken something of a spectacular turn.

During his life–at least since the 1960s–Kubrick gained the reputation as a recluse, living in seclusion in his manor house in the north of London. He was so little seen that, in the 1990s, an impostor appeared in London, convincing people that he was Stanley Kubrick. The fact is that Kubrick simply kept to himself with his family, eschewing publicity, always reading and preparing films, carefully, sometimes obsessively. Little was known about his life. He would allow one carefully vetted interview after the release of a new film with only silence in between. Shortly after his death, the family began talking about the life of the mysterious director and went some distance in humanizing him, despite the nasty memoir by Frederic Raphael, his scriptwriter on his last film, Eyes Wide Shut. His collaborators gave informative interviews and there were moving documentaries appended to the DVD releases of his films. But much more important than these was the donation of his papers, records, and scripts to the University of the Arts in London. Now there are, available to scholars, documents providing insights into the work, the preparations, preproduction, production, and distribution of Kubrick’s films.

One can trace, for example, the scriptwriting process of his last film, Eyes Wide Shut (based on Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle), and discover, among other things, what drove screenwriter Frederic Raphael to write that bitter memoir about working with Kubrick, Eyes Wide Open. The successive scripts are filled with Kubrick’s handwritten notes and post-its: “Follow Schnitzler,” “Keep it as short as Schnitzler,” “I don’t like the imagery,” “No wisecracks.” Even once: “Good line.” Raphael grew impatient. Annoyed faxes were sent. Eventually, Kubrick graciously took the script and wrote it to fit his vision, while giving Raphael full onscreen credit. And this is an important thing to understand about Kubrick’s creative process: he needed a head start from someone, whether a screenwriter or his actors. He needed to see, to understand what he needed, and pushed, sometimes relentlessly, to get it. The archives offer Kubrick scholars a way for them to see how the process of coming-to-be came to be.

The archives are certainly not complete. Kubrick’s favorite modes of communication were faxes, not all of which are preserved, and the phone, those long, late night phone calls that tried the patience of Kubrick’s collaborators. These, of course, were not recorded and therefore are not archived, meaning that a large part of the creative process is still left unknown.

The Kubrick Archives present yet another problem to the critical process itself. What does their existence mean to the interpretation of the canon? There are scholars who believe no serious work on Kubrick can be done without the appropriate archival research, that criticism and analysis must be tethered to the known facts that exist on the archived paper records. But does that mean that textual analysis—readings of the films as self-contained entities—is no longer valid? Not every film scholar will have the opportunity to make it to London.

As the novelty of the Archives wears off a bit, a balance will be reached. The depth of detail that can enable us to understand the minute particulars of the making of a particular film will be balanced, ideally combined with, intelligent readings of the films themselves, along with the background material gleaned from the Archives, that extraordinary collection of the work of an extraordinary cinematic mind.

Featured Image credit: Posters of Stanley Kubrick’s films, LACMA Dec 2012. Jane Rahman, CC BY 2.0 vie flickr .

The post The legacy of Stanley Kubrick and the Kubrick Archives appeared first on OUPblog.

On the value of intellectuals

In times of populism, soundbites, and policy-by-Twitter such as we live in today, the first victims to suffer the slings and arrows of the demagogues are intellectuals. These people have been demonised for prioritising the very thing that defines them: the intellect, or finely reasoned and sound argument. As we celebrate the 161st birthday of Bernard Shaw, one of the most gifted, influential, and well-known intellectuals to have lived, we might use the occasion to reassess the value of intellectuals to a healthy society and why those in power see them as such threats.

Born in Dublin on 26 July 1856 to a father who held heterodox religious opinions and a mother who moved in artistic circles, Shaw was perhaps bound to be unconventional. By age 19 he was convinced that his native Ireland was little more than an uncouth backwater–the national revival had yet to see the light of day–so he established himself in London in order to conquer English letters. He then took his sweet time to do it. In the roughly quarter of a century between his arrival in the metropole and when he finally had a modicum of success, Shaw wrote five novels–most of which remained unpublished until his later years–and eked out a living as a journalist, reviewing music, art, books, and theatre. That eminently readable journalism has been collected in many fine editions, and we see in it an earnest individual not only engaged in assessing the qualities of the material before him–much of which was dreadfully insipid–but eager to raise standards and to cultivate the public. He prodded people to want more and gave them the tools to understand what a better art would look and sound like. And he did so in an inimitable voice that fashioned his renowned alter ego: the great showman and controversialist, GBS.

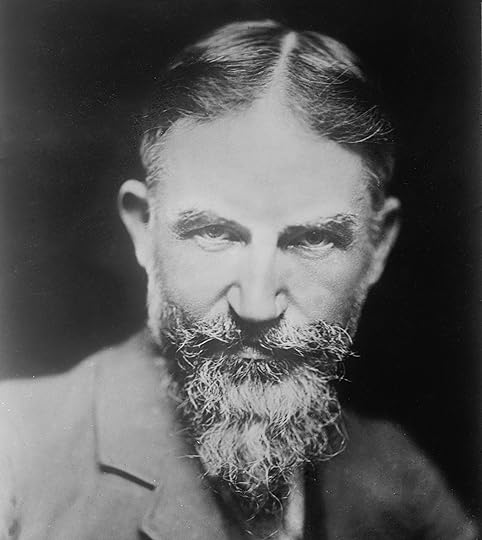

“George Bernard Shaw, circa 1900” from the Library of Congress, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“George Bernard Shaw, circa 1900” from the Library of Congress, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Shaw become more widely known as a playwright in late 1904, when King Edward broke his chair laughing at the Royal Command performance of Shaw’s play John Bull’s Other Island. He was no longer a journalist by trade, now being able to live by his plays, but Shaw continued to write essays, articles, and letters-to-the-editor in leading papers to set the record straight, to denounce abuses of power, and to suggest more humane courses of action. When he published his plays, he wrote polemical prefaces to accompany them that are sometimes longer than the plays themselves. These prefaces, written on an exhausting range of subjects, are equally learned and entertaining. Indeed, it has been said by some wags that the plays are the price that we pay for his prefaces.

In many ways continuing his fine work as the Fabian Society’s main pamphleteer in the 1890s, his prefaces suggest remedies for the great injustices of his time. And, what’s more, the vast majority of his prescriptions are as topical and provocative today. For example, if you’re American, should you opt for Trumpcare or Obamacare? Read The Doctor’s Dilemma and its preface and you’ll have a compelling case for neither, but rather a comprehensive and fully accessible public healthcare system, the sort now common in Canada and most European countries. That’s right, people were feeling the Bern–we might say the original Bern–well before Mr. Sanders was born.

Some of Shaw’s opinions came at a great cost. When he published Common Sense About the War, which was critical of both German and British jingoism at the outset of the Great War, he ran too much against the grain of the hyper-patriotic press and government propaganda, thereby becoming a pariah to many. But his star gradually returned into the ascendant as the body count mounted and a war-weary population came to share his point of view. The run-away international success of Saint Joan brought him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925 and, as Shaw said, gave him the air of sanctity in his later years.

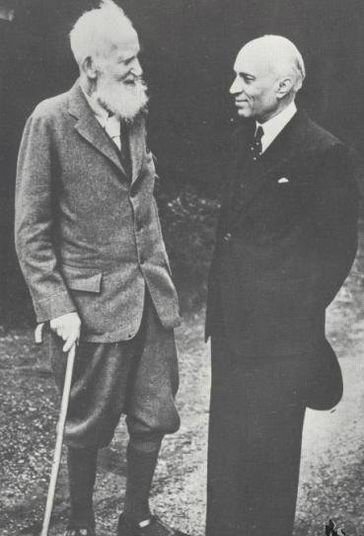

“George Bernard Shaw with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, May 1949”, from Nehru Memorial Museum & Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“George Bernard Shaw with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, May 1949”, from Nehru Memorial Museum & Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.However, Shaw always maintained that he was immoral to the bone. He was immoral in the sense that, as a committed socialist in a liberal capitalist society, he didn’t support contemporary mores. Instead, he sought to change the way that society was structured and to do so he proposed absolutely immoral policies. A good number of these beyond universal healthcare have seen the light of day, such as education that prioritises the child’s development and sense of self-worth, the dismantling of the injustices of colonial rule, and voting rights for women. But those in power continue the old tug-of-war, and the intellectuals of today must be as vigilant, courageous, and energetic as Shaw in the defence of liberal humanist and social democratic values. Witness the return of unaffordable tertiary education in the UK, made possible by both Labour and Conservative policies. We might recall that Shaw co-founded one of these institutions–the renowned London School of Economics–because he believed in their public good.

Whenever Shaw toured the globe in his later decades–he died in 1950 at age 94–he was met by leading politicians, celebrities, and intellectuals who wanted to bask in his wit, wisdom, and benevolence (Jawaharlal Nehru, Charlie Chaplin, and Albert Einstein are a few such people). Time magazine named him amongst the ten most famous people in the world–alongside Hitler and the Pope. Everywhere he went, the press hounded him for a quote. Yet despite the massive fees he could have charged, he never accepted money for his opinions, just as he had declined speaking fees in his poorer days when he travelled Britain to give up to six three-hour lectures a week to praise the benefits of social democracy. He would not be bought–or suffer the appearance of being bought.

On his birthday, then, we would do well to think of Shaw and maybe even read some of his plays, prefaces, or journalism. We might also cherish the service and immorality of intellectuals. And we should always question the motives of those who denigrate their value.

Featured Image Credit: “George Bernard Shaw near St Neots from the Millership collection” from the Birmingham Museums Trust, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post On the value of intellectuals appeared first on OUPblog.

July 25, 2017

Picking a fight in an empty room

This year marks the 137th anniversary of the birth of Seán O’Casey, one of the best-known of all Irish playwrights. His works first enthralled audiences at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre during the 1920s, and in the years since then his dramas have been repeatedly revisited by actors and directors. In particular, O’Casey’s Dublin dramas have repeatedly appeared onstage in some high-profile stagings during the past twelve months.

O’Casey set his best-known play The Plough and the Stars (1926) during the 1916 Easter Rising, and he takes a subversive and irreverent look at all sides in the conflict. This year, Dublin held a series of high-profile commemorative events over the Easter period to mark the one hundredth anniversary of the rebellion, and in the midst of all, O’Casey’s play appeared at the Abbey, which is the National Theatre of Ireland. Simultaneously, at the other end of O’Connell Street, Dublin’s well-known Gate Theatre staged an Easter version of O’Casey’s early work Juno and the Paycock (1924), a drama which is set during the 1922 Civil War. Then, hot on the heels of these shows, the Dublin Theatre Festival featured a four-and-a-half hour play, It’s Not Over, which took its cue from O’Casey’s 1916 script. And during the summer and autumn of 2016, the National Theatre of the UK staged another version of The Plough and the Stars, for which I wrote some programme notes and hosted a day of lectures, where attendees had the chance of hearing from the wonderful O’Casey director Wayne Jordan, the leading theatre-scholar Nicholas Grene, and the acclaimed novelist Mary Morrissy.

What I found so interesting about that day of lectures at the London National Theatre was the way that O’Casey’s work continues to speak to new audiences and to new generations. Mary Morrissy, for example, explained that she had constructed her novel, The Rising of Bella Casey (2013), by deeply immersing herself in O’Casey’s published work, his biography, and his unpublished manuscripts. Director Wayne Jordan described how, in his productions of O’Casey’s drama, he has sought to emphasize the way in which O’Casey casts an clear eye upon the injustices that continue to exist in Irish society. In one of my own lectures, I highlighted the affinities between O’Casey’s subversive political humour and the more recent work of The Rubberbandits and Pat Shortt, whilst Nicholas Grene pointed to the way that O’Casey’s sense of Dublin’s geography might relate to our modern conception of the city.

Some of the onstage appearances of O’Casey’s work during the last year have likewise highlighted a set of contemporary concerns. For example, Sean Holmes’s 2016 version of The Plough and the Stars at the Abbey Theatre made the character of the child, Mollser, central to the drama. Indeed, in this Brechtian rendering of the play, Mollser began the entire drama by standing alone (dressed in red sneakers and a red Manchester-United shirt) in the spotlight onstage and singing the Irish national anthem, which was interrupted by her coughing and hacking blood into a handkerchief. Mollser then remained an almost ever-present figure on the stage throughout the play, only disappearing from view shortly before her death, after which her coffin took her place. So, unlike in O’Casey’s original script–which makes limited use of the character–either Mollser or Mollser’s body was onstage almost from start to finish.

The idea of having Mollser onstage almost throughout the drama helped to heighten and draw attention to one of the most important and still pertinent themes of O’Casey’s drama: the way that certain children suffer from terrible neglect in poor families. For example, in act two of The Plough and the Stars, a character called Mrs. Gogan brings her baby into a pub and feeds it with whiskey, before getting into a fight and leaving without her child, provoking panic among the men who are left with it. Sean Holmes’s version of the play allowed us to see what we do not usually have visualised: the fact that Mollser, Mrs. Gogan’s other child, was being similarly neglected, left alone at home whilst sickening and dying.

Furthermore, in this production, Mollser was not being played at the Abbey by a white actor but by the talented young performer Mahnoor Saad. In act two, Saad was onstage at the same time as version of Rosie Redmond, a prostitute, who, in this version of the play, yelled in Armenian across the bar at one moment of frustration. The casting of these actors, their distinctive use of voice, and the fact that they were clad in modern-day dress rather than the fashions of 1916, helped to make the point about who the new underclass of modern Ireland might be, and about the struggles of women and children from the New Irish communities.

The Abbey production’s insistent focus upon the child who was dying, who was one of the New Irish, and who was part of our modern economic underclass meant that the production kept pointing to the relevance of O’Casey’s work to our world today. And the performers clearly intended that their work should have a practical outcome too: on Easter Monday, the actor playing Bessie Burgess interrupted the applause to say that the cast would be donating their bank holiday pay to a children’s charity and encouraging the audience to make a contribution too.

There is sometimes a danger that we view the great works of literature as pickled in aspic, to be taken down, and admired, and then replaced on the shelf. But O’Casey– that great argumentative writer who sometimes appeared capable of picking a fight in an empty room–produced works that are still capable of provoking and engaging us. As with Shakespeare’s plays, O’Casey’s rich dramas, with their memorable characters and phrases, and that potent blend of tragedy and comedy, continue to speak afresh as the world continues in its ongoing state of “chassis.”

Featured Image credit: Plaque in Saint Patrick’s Park, Dublin. Emkaer, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Picking a fight in an empty room appeared first on OUPblog.

The perils of political polarization

Political polarization in the United States seems to intensify by the day. In June 2016, surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center revealed that majorities in both parties held highly unfavorable opinions of their opponents. Many Democrats and Republicans even admitted to fearing the rival party’s political agenda. Such strong feelings have scarcely dissipated—and likely escalated—since those surveys were completed.

This is hardly the first time in American history when polarization has plagued the nation. Divisions over slavery sparked a civil war in the 1860s. A century later, the war in Vietnam and the civil rights movement generated fierce dissension. Less well known (except to historians), the 1790s witnessed such ferocious discord between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans regarding the French Revolution and domestic policy that some contemporaries feared the United States might not survive into the nineteenth century.

America’s experience with partisanship actually goes back even farther than that, right to the birth of the nation. The Revolution was not only a struggle against Britain; it was also a civil war, dividing colonists who supported independence from those who did not. Then, as now, one of the greatest dangers of extreme partisanship is the way it drives people to question the motives of their adversaries and even to contemplate violence against them. At the time of the Revolution, anyone who advocated compromise or tried to remain neutral was suspected of being a secret ally of one of the rival groups. For one Connecticut farmer who sought to distance himself from both patriots and loyalists, failure in this endeavor to find a middle ground meant death

Newgate Prison was used to house prisoners of war during the American Revolutionary War. Credit: “Old Newgate Prison, Connecticut.” by Paul Gagnon. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Newgate Prison was used to house prisoners of war during the American Revolutionary War. Credit: “Old Newgate Prison, Connecticut.” by Paul Gagnon. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Moses Dunbar made no secret of his allegiance to the king, but that did not mean that he endorsed the Parliamentary taxes and other measures that drove patriots into opposition to Britain. What he rejected, as the imperial crisis escalated in 1774, was the patriots’ eagerness to resort to arms instead of seeking a peaceful resolution to what Dunbar called the “Unhappy Misunderstanding” between Britain and the colonies. Once the war began in April 1775, such calls for moderation had even less chance of being heard.

Fear of British military retaliation drove Connecticut patriots to try to identify suspected loyalists and subdue them by any means possible before they could aid the enemy. Some were confined deep underground in the infamous Newgate prison, an old copper mine. Others—including Moses Dunbar—suffered beatings from patriot gangs. After such an attack and repeated attempts to imprison him, Dunbar beseeched authorities to let him retreat to his farm and avoid the political fray. Neutrality, however, was no longer an option.

Dunbar’s decision to go to British-occupied New York in September 1776 and enlist in a loyalist regiment had far less to do with his allegiance to Britain than with a beleaguered man’s quest for safety for himself and his family. While he was in New York, Connecticut’s legislature declared such an enlistment to be a capital crime. When Dunbar returned home in late December 1776 to fetch his wife and children, a neighbor—likely induced by a desire to deflect patriot concerns about his own political allegiance—alerted authorities to Dunbar’s presence. Dunbar was arrested, convicted of treason, and executed on 19 March 1777.

As it turned out, Moses Dunbar was the only loyalist executed for treason by the state of Connecticut. The authorities clearly wished to make an example of him, but having done so were willing to retreat from using extreme measures against suspected British sympathizers. Perhaps unnerved by the deadly consequences of turning neighbor against neighbor, officials exercised greater restraint in assessing true threats and acknowledged that some people genuinely wished to remain neutral.

Passions inflamed by war typically exceed those generated by peacetime partisanship. Yet the fate of Moses Dunbar in Revolutionary Connecticut offers an unusually vivid example of what can happen when fear and suspicion lead people to translate a far more complex situation into a stark opposition of friends versus foes. At the same time, what happened in the aftermath of Dunbar’s execution demonstrates how a fractured society could begin to heal its wounds.

Once the War for Independence ended, many loyalists fled the United States to live in England or one of its remaining colonial possessions. But many more loyalists—including would-be neutrals mis-characterized by their opponents—stayed in the new nation. Dunbar’s descendants belonged to this group, and some of them continued to reside among the very people who had harassed and betrayed him. Although they never recorded their reasons in doing so, former adversaries exhausted by years of conflict evidently made a decision to cease making enemies of their neighbors. Concentrating on what they had in common rather than what drove them apart promised to be a far more productive way to escape a divisive past and head into the future.

Featured image credit: ” Postcard depicting Old Newgate Prison” by Unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The perils of political polarization appeared first on OUPblog.

Prospection, well-being, and mental health

That we remember the past is obvious. But as well as the ability to recall what has already happened to us, we are also able to imagine what might happen to us in the future. Is this capacity for prospection important? Absolutely. Being able to anticipate what might happen and take relevant steps, prioritise goals, and form plans of action for what we are going to do have been fundamental to our evolutionary success. Prospection underpins most of what we do on a daily basis, enabling us to navigate our way through the complexities of life. But surviving, reproducing, and functioning, fundamental as they are, do not tell the whole story about what most of us would think of as a good life. We also want lives that are happy. How is prospection important for this kind of emotional well-being? This question has been at the heart of what I have spent the last 30 years researching.

Prospection is complicated and difficult to study. It is less definite than memory because we are referring to things that have not yet happened, and might never happen. It is also made up of quite varied mental states. For example, having a general optimistic outlook that the future will be good is very different from having a detailed picture in mind of a scheduled happy event in the future, like one’s wedding day coming up. Both of these are different from having a personal goal that one is working towards or making a prediction that one’s favourite team will win the league.

“But surviving, reproducing, and functioning, fundamental as they are, do not tell the whole story about what most of us would think of as a good life. We also want lives that are happy.”

Memory researchers, such as Dan Schacter at Harvard University, have turned their attention to prospection in recent years, bringing with them some of the useful concepts and methods from memory research. One of the things that Schacter and his colleagues have contributed is a taxonomy of prospection. According to this taxonomy, we make predictions about the future, simulate (imagine) detailed future events, form goals and intentions about things that we want, and make plans of action to take us towards our goals. There are probably other ways we think about the future too, like our underlying assumptions and attitudes about the future, but this taxonomy is a helpful way of organising the varieties of prospection.

During the past 30 years of my research into prospection, I have had some surprises along the way. For example, early on we discovered that people who are depressed, even those who are suicidal, have no more thoughts than others do about negative things in the future, that is, things that they are not looking forward to or dreading. They only show a marked reduction in being able to think of positive things they might look forward to. In contrast, those who are high in anxiety have no problem thinking of positive things in their future; the problem they have is they find it all too easy to bring to mind negative future possibilities. Another approach we have taken is to ask people about their personal future goals. Somewhat to our surprise, even those who are suicidal are able to list their goals without much difficulty. What they struggle with, though, is thinking about the steps they could take to get to their goals, as well as believing that they will get there. This state of painful engagement – knowing clearly what one would like in the future but feeling it is out of reach – is likely to be particularly harmful, especially if someone is unable to detach from these goals and engage with new ones.

Although much has been uncovered about prospection and well-being, there are still many interesting unanswered questions in this undeveloped field. How accurate or inaccurate are people who are depressed or anxious in their predictions about what will occur to them in the future, and how do they imagine they will feel at that time? Does accuracy actually even matter? If accuracy does matter, can people be made to be more accurate through, for example, cognitive behavioural therapy? If people are not good at simulating positive future events, can they be helped by techniques that might improve simulation ability? Similarly, can helping people to tune into important goals and learn planning skills help them to move towards goals that they previously felt were out of reach? The hope is that by understanding more about the ways prospection is implicated in different emotional problems, we might be able to develop more effective means to help people think about the future in ways that help, rather than hinder, them.

Featured image credit: Dorset, by Diego_Torres. Public domain CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Prospection, well-being, and mental health appeared first on OUPblog.

Music and human evolution

After being closed to the public for the past six months, the Natural History Museum’s Hintze Hall reopened on the 13 July 2017, featuring a grand blue whale skeleton as its central display. This event carried particular importance for OUP’s Gabriel Jackson, who was commissioned to write a piece for the Gala opening ceremony.

The piece, This Paradise I give thee, is a short composition for 13 instruments and baritone solo which draws inspiration from the diversity of the natural world alongside the words of Charles Darwin and John Milton. With this piece Gabriel maps processes and theories of evolution onto music. The idea that evolution can be expressed through music poses some interesting questions; what happens when you consider this relationship from an alternative angle? How has music evolved with humans over time? In his chapter “Music and Biocultural Evolution” Ian Cross, Professor of Music and Science at the University of Cambridge, provides some interesting ideas.

Although most modern scholarship on music only stretches back to the 1100s or so, music is truly ancient. The earliest example of sophisticated musical instruments (in the form of pipes made of bone and horns) date to around 40,000 years ago. Whilst this may not sound that far back, this predates all examples of visual art.

These early instruments were found in Germany; however, much like today, musical production was not only centred in this part of the world. In fact, there is evidence of music having existed globally at this time, with music production being found in places as far-flung as the pre-Hispanic Americas and the Aboriginal people of precolonial Australia.

Four skulls in a row, by JuliusKielaitis © via Shutterstock.

Four skulls in a row, by JuliusKielaitis © via Shutterstock.It is generally assumed that the creation of these very early physical instruments occurred significantly after the human capacity for musicality developed. As such, it is likely that other methods of music making that do not involve sound production from instruments, such as singing, date much, much further back than 40,000 years. According to Cross, this assertion provides good grounds for believing that music may have accompanied humans from the earliest signs of modern activity.

Of course, in order for these theories of music as a product of evolution to withstand scrutiny, Cross and other scientists have to rely upon a much more malleable notion of music than that which we often use today. According to the Oxford Dictionaries music is, “Vocal or instrumental sounds (or both) combined in such a way as to produce beauty of form, harmony, and expression of emotion.” This definition is unlikely to fit with notions of pre-modern music, and, indeed, does not fit all music that is produced today. Some people, for example, may find it quite difficult to perceive a sense of form or harmony in a work such as this:

The notion that all music fits within the definition posed in the Oxford English Dictionary could therefore be considered a little Western-classical centric; however, the fact that all music expresses emotion is an inescapable truth. Whilst the emotions felt are often specific to an individual, it is unlikely that one would listen to a piece and feel nothing at all.

In addition to expressing emotion, there are also a number of other persistent similarities to be found when establishing the traits of music across cultures. For example, music nearly always carries some form of complex sound event (such as structured rhythms, or pitch organisation) over an underlying regular pulse. This is true regardless of the genre of music that is being listened to. When considering the importance of time in a musical performance, and the transition of emotions, then, some suggestions begin to emerge regarding the reasons why music may have evolved with us.

Cross outlines that, through allowing people to create something together via a regular pulse or beat, musical sounds may have provided a means through which people could envisage that they were sharing each other’s experiences, thus fostering social bonds.

Similarly, music’s capacity to transmit emotions that are felt by everyone, yet specific to an individual, may suggest that it was created as a way of understanding individual and group feelings, particularly in times of social uncertainty. Indeed, as Cross states, the ability to share emotions and “intentionality” is fundamental to our capacity for culture, the possession of which is assumed be a generic feature of modern humans.

Music’s ability to create and maintain social relationships, alongside its direction and motivation of human attention, is likely to have been incredibly important to the survival of pre-modern humans. When taken outside of its more modern context of entertainment, it is indeed likely that music provided an imperative social tool throughout the history of human evolution, and represents just one of the many ways in which humans are “different” from other species.

Original chapter written by Ian Cross, Professor of Music and Science at Cambridge University. Chapter published in “The Cultural Study of Music: A Critical Introduction”, Routledge, 2003. Extracts used by kind permission of Ian Cross.

Featured image credit: Stone wall with ancient musicians, by Repina Valeriya © via Shutterstock.

The post Music and human evolution appeared first on OUPblog.

July 24, 2017

Travel medicine health tips

The world is becoming more globalised, with the number of people traveling each year on the rise. US residents are taking nearly two billion leisure trips and almost 500 million business trips (2016), with UK residents making 70.8 million visits overseas last year (2016), an 8% increase to the previous year (2015).

With travel visits increasing year on year on a worldwide scale, it is no wonder travel medicine is an area also growing quickly to match activity and demand.

So, what are some of best and useful travel health tips for those traveling?

We asked a number of experts committed to the promotion of healthy and safe travel, from physicians, nurses, and pharmacists, to public health officials at The 15th Conference of the International Society of Travel Medicine (CISTM15) this year, what their top travel health tips were.

Bring a handful of drinking straws

See a travel health professional well in advance of your departure

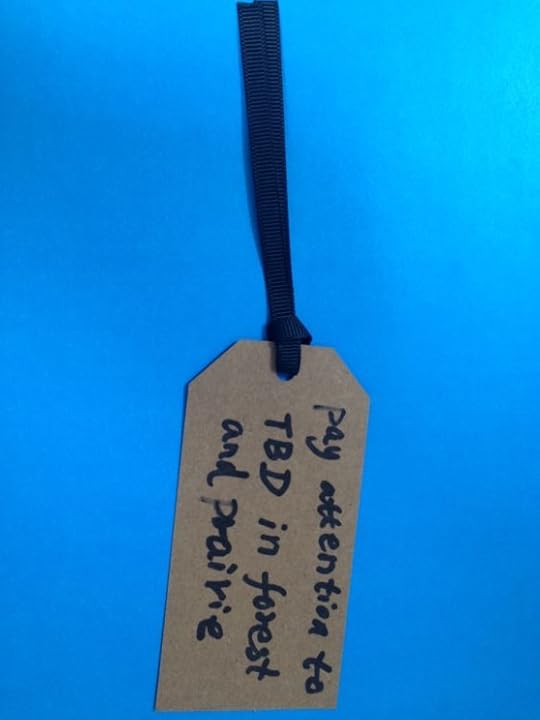

Pay attention to Tick-Borne Diseases (TBD) in forests and prairies

Don’t drink from local water supply in developing countries

Visit your travel clinic early

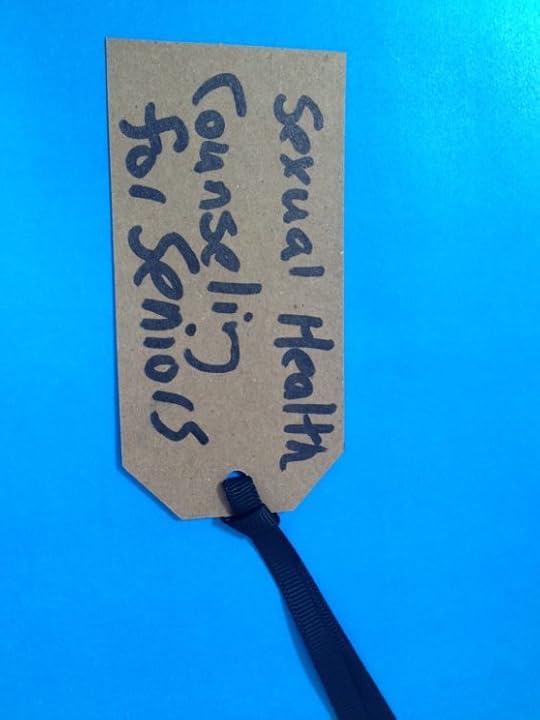

Sexual health counselling for seniors

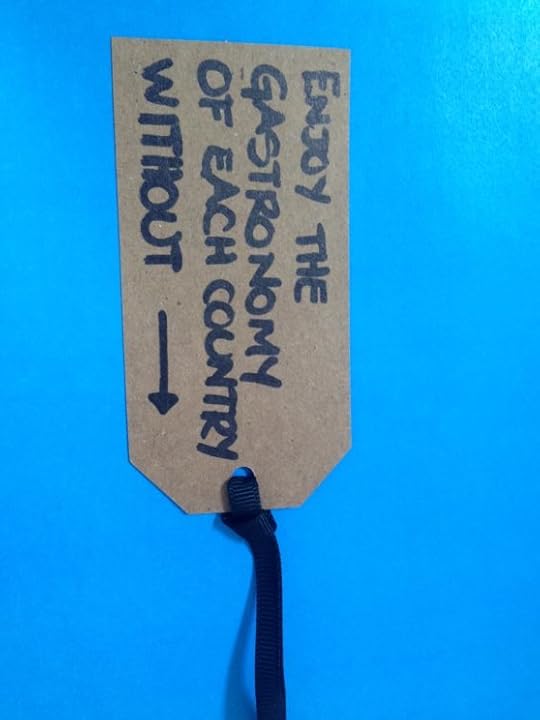

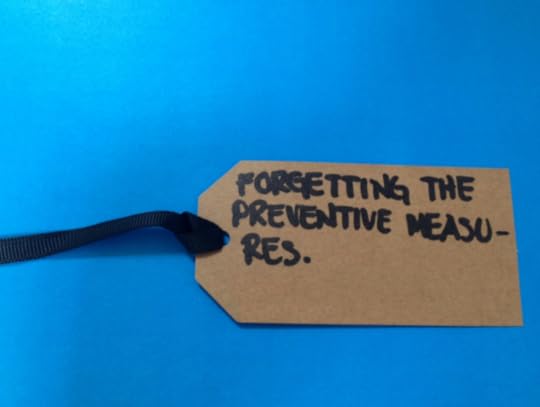

Enjoy the gastronomy of each country, without forgetting the preventative measures (1/2)

Enjoy the gastronomy of each country, without forgetting the preventative measures (1/2)

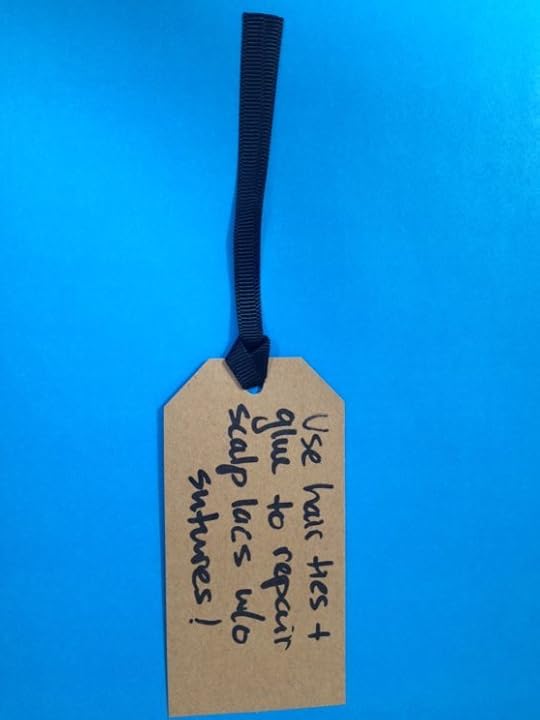

Use hair ties and glue to repair scalp lacs w/o sutures (Advice for the experienced health professionals - don't try this at home)

Featured image credit: Ocean by Clem Onojeghuo. CC0 public domain via UnSplash.

The post Travel medicine health tips appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers