Oxford University Press's Blog, page 341

July 29, 2017

Optimism in economic development

There is much discussion about global poverty and the billions of people living with almost nothing. Why is it that governments, development banks, think-tanks, academics, NGOs, and many others can’t just fix the problem? Why is it that seemingly obvious reforms never happen? Why are prosperity and equity so elusive?

Economic development is not easy. Good ideas and good intentions have usually crashed against a wall of vested interests, incapable institutions, and chronic corruption. And the recent backlash against globalization will only make matters worse—if rich countries shut their doors to the movement of goods, capital, people, and ideas, the world’s poor will suffer disproportionately.

Yet, behind and beyond the headlines, politics and technology are coming together to make economic development more likely for more countries than ever before. How come?

First, the way governments function, and for whom they function, is changing fast. It is in fact probable that, one day, governments will work for us. Why the hope? Think of four “Ds”: democracy, decentralization, devices, and debt. The more our leaders feel that others are vying for the top job—that is, leadership becomes “contestable”—the more they will care for what voters want. This is true for presidents and prime ministers, but it is even truer for governors and mayors. As the responsibility for public schools, hospitals, and roads is further “decentralized” towards local authorities, it gets easier to demand accountability—closer physical proximity between policy-makers and policy-takers is “welfare-enhancing.” Moreover, we now have “devices” that let us name and shame public officials in real time. With your smart phone, you can set off and organize a massive protest from the comfort of your Twitter feed or Facebook account. For us citizens, the marginal cost of “collective action” is approaching zero. And then, there are bondholders, those investors who buy national debt and expect to be repaid. They trade their bonds 24/7, and sell them off in a blink if our government messes with the economy. This instantaneously raises the country’s “spread”—the difference in interest rates it has to pay to borrow, compared to the US government. Everyone sees this information, both at home and abroad, and soon enough political pressure mounts to correct course. Call it “accountability by spreads.”

“It is in fact probable that, one day, governments will work for us.”

Politics and technology are also changing our understanding of economic management. It starts with the industrial process, which has become a cobweb of “global value chains”. This is the idea that most of the products that consumers buy—say, cars—are made up of parts and designs produced in different countries and shipped across borders to a final assembly site. The “well-paying jobs” that politicians talk so much about are now inside those value chains. But you can’t be part of a chain, let alone climb it, if you can’t keep up with it. Imagine if your country manufactures car tires but, because of weak quality controls, changes in tax rules, or poor port maintenance, you can’t be trusted to deliver the tires according to specifications, at the cheapest possible price, and on time. Everyone else’s effort along the chain would be wasted. How long before they cut you off? Why would you be invited in the first place? You see, value chains force countries to rise up to a more-or-less common standard of economic management: fiscal prudence, independent central banks, low public debt, open trade, smart regulation, adequate infrastructure, capable workers, and fair treatment of investors. Without these, you cannot offer the predictability that modern, globalized industry needs, and the jobs that people want.

Finally, we have new weapons in the war on poverty. Technology has made it possible for policy-makers to know the poor by name, individually, one by one. As India has shown, you can biometrically identify almost a billion people in about seven years, at a cost of less than four dollars per head. Once you ID the person, it is almost costless to transfer cash directly to her or his debit card or cellphone. So more than seventy developing countries do just that. Some attach conditions to the transfer—like keeping your kids in school—and others don’t. This individualized approach to social policy is not just politically popular, it is also incredibly effective. It allows you to react faster, and send more cash to those in need, when an economic crisis breaks out. It helps you promote desirable social behaviors—from breast-feeding to vaccination. It sheds light on the aberration of subsidizing the rich—as many governments do when they sell things like gasoline or electricity at below-cost prices. And, one day, it may be used to turn citizens into shareholders who directly receive dividends from the oil, gas, or minerals that their countries export. Picture that for Africa.

All this optimism about economic development is not without risks. In the short-term, one worries about protectionism in the United States, stability in the European Union, and slower growth in China—just to name a few. Even more difficult problems loom in the horizon, like climate change, cyber-security, and chronic conflict. These global challenges call for international coordination, something at which the world is not very good.

But, overall, never before did the profession of economic development have the alignment of technical tools and political incentives that it has today. Yes, we will still see countries zig-zagging along the path of common-sense policy, and a few stubbornly going backwards. For most, however, the chance at a better life has never be greater.

Featured image credit: “dollar” by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Optimism in economic development appeared first on OUPblog.

Children, obesity, and the future

The problem of obesity: it has persisted despite global efforts to reverse it. We all hear regular news reports about it, about how prevalence rates globally remain stubbornly high, about how this factor and that factor cause it, and about government strategies to address it. And still, it proves a puzzle yet to be solved. Ten years ago in the United Kingdom, the Foresight Obesity System Map report described factors evidenced to cause obesity and their interrelationships, in what is one of the most detailed mapping of such a complex health issue. It identified factors across society, from individual biological and psychological factors to distal social and infrastructural influences, and included a thirteen component stress subsystem.

Recent research reflects some of this range of aetiological factors that influence childhood obesity. Global perspectives from countries of study including Brazil, Australia, England, South Africa, China, and a review of the international literature cover topics frequently reported by the media, like the food environment, unhealthy food advertising policy, weight management interventions, and associations with gender and sleep. Lesser known research areas include the developmental origins of obesity, which examines how foetal conditions in utero can influence the amount of fat deposited on the body in childhood and adulthood. This field of research provides the kind of evidence used to justify a public health approach to obesity, with a focus on prevention in early life. Another important area of public health research, but again perhaps lesser known, is the roles of schools and parents, given the tendency for policy approaches to involve schools and communities in prevention.

While the Foresight Obesity System Map helped to shift thinking about obesity as an energy imbalance, to an issue that is complex and underpinned by inequalities, there has not been the expected depth of research on the ‘whole system’ of obesity. Systems thinking takes into account the context of public health problems; considers the various levels on which public health can be addressed (local, regional, national and international); and seeks to engage a range of sectors that can play a vital role in transforming the whole of society (health, education, housing, leisure, and so on).The tendency in many national policies is to ‘drift’ back to changing lifestyles by continuing to approach obesity with downstream, micro-level behaviour change initiatives. In general, these approaches are not effective at preventing non-communicable diseases including obesity at a population level and might generate weight stigma, thereby possibly perpetuating further weight gain.

“Given the incredible resistance of obesity to current approaches, more out-of-the-box thinking is required.”

Given the incredible resistance of obesity to current approaches, more out-of-the-box thinking is required. New approaches to public health are required and have been discussed in the literature as part of the shift to the third era of population health, which focuses on optimising health and wellbeing. For example, a recent study highlighted the most pressing issues facing many African American communities, including inadequate housing, unemployment, familial stress and violence. The authors argue that placing too much emphasis on obesity as a priority area can ‘get in the way’ of solutions that could actually make a difference to people’s health and communities, given the wider forces known to cause it, with obesity being affected as a collateral benefit.

To say the future of our children and young people is uncertain would be an understatement. The global health and political landscapes of the early 21st century present many challenges. Widening inequalities, global economic recession, global warming, insecure employment, rising debt and housing prices, and cuts to social benefits threaten the future prospects of children and young people and will undoubtedly shape their future health needs. We are already seeing rises in mental health issues amongst children and young people, such as self-harm and suicide, which is thought to be associated with stress resulting from such uncertainties, bullying and increasing exam pressures. We also know those with severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, are more likely to be obese. The wide-ranging global challenges we face also threaten the health systems that seek to support children and young people’s health holistically. Given the increasing complexity of health issues, as observed in the case of childhood obesity, systems thinking is needed to ensure that in such times of uncertainty an integrated health and social care systems can be developed, afforded, and sustained.

Featured image credit: Donut by BootstrapGiver. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Children, obesity, and the future appeared first on OUPblog.

Breaking the rules of grammar

Can grammar be glamorous? Due to its meticulous nature, the study of grammar has been saddled with an undeserved intimidating reputation.

Esteemed linguist David explains how grammar is an essential tool for communication. Demystifying the rules behind the English language can allow us to communicate effectively both professionally and casually.

In the following excerpt from Making Sense: The Glamorous Story of English Grammar, Crystal demonstrates how to break the rules by analyzing the grammatical risks taken in commercial advertising and journalism.

In occupational varieties such as religion, law, and sports commentary, the situational constraints of grammar are tight and well respected by practitioners. It would be virtually impossible for the professionals involved to use a kind of language that didn’t conform to the expected norms.

Indeed, in some circumstances, if the wrong kind of language was used, there might be social sanctions, such as (in law) a charge of contempt of court or (in religion) an accusation of blasphemy or heresy. However, not all occupations have their language so tightly constrained.

In commercial advertising and journalism, there are grammatical rules that are generally followed, but the bending and breaking of those rules is commonplace and privileged.

Take the most basic rule of all: that writing intended for national public consumption should display present-day standard English grammar. This means an avoidance of nonstandard items such as “ain’t,” regional dialect constructions such as “we was” or “I were” sat, and obsolete forms such as “ye” and “goeth”. But it doesn’t take long before we see all these usages in print and online, often as eye-catching headlines for articles on web pages.

“We wuz robbed, viewers” – an article in Daily Mail Online

“There’s gold in them there hills” – report in The Telegraph of a Scottish estate which contains untapped gold reserves

“The corporate taxman cometh” – article in The Economist on taxation

“Abandon sleep all ye that enter here” – report in Trip Advisor

“Nigeria ain’t broke, it just needs to fix its tax system” –article in The Guardian

Community memory holds a large store of archaic or regional forms upon which headline writers and journalists frequently rely, usually to produce a catchy headline or to add an element of humor or parody to an article. And it doesn’t take long before clever writers begin to play with the forms, taking them to new rhetorical heights. The idiomatic expression underlying the last example above — “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” —has generated many variants:

“If it ain’t broke, break it” – an article about writing new kinds of crime novels

“Hey, Twitter: if it ain’t broke, don’t add 9.8K characters to it” – a post about a Twitter proposal to allow longer tweets

“If it ain’t broke, don’t upgrade it” – a post on a new release of Photoshop

“If we can’t fix it, it ain’t broke” – a sign outside a car repair shop in the USA

An Internet search will bring to light many more.

Any grammatical rule can be bent or broken in the advertising world. For example, there’s no theoretical upper limit to the number of adjectives we can have before a noun, but it’s unusual to encounter more than two or three. Certainly not 12, as in this ad from a few years ago: “Why do you think we make Nuttall’s Mintoes such a devilishly smooth cool creamy minty chewy round slow velvety fresh clean solid buttery taste?”

Or again, we all have a free hand to make compound adjectives in a noun phrase, such as best-selling and far-reaching.

But none of us outside advertising would go in for such coinages as farmhouse-fresh (taste), rain-and-stain-resisting (cloth), and all-round-the-garden (fertilizer). A single instance might not be very noteworthy; but the repeated use of a grammatical feature becomes very noticeable in a longer ad.

Note the number of pre-noun sequences in this example from Geoffrey Leech’s classic English in Advertising (1966):

Fantastic acceleration from the 95 bhp Coventry Climax OHC engine, more stopping power from the new 4-wheel servo-assisted disc brakes and greater flexibility from the all synchromesh close ratio gearbox. These and many other new refinements combine to present the finest and fastest light GT car in the world.

There aren’t many words left!

When we see written ads, our eyes are inevitably drawn to the visual features—the product image, the graphic design, the colors, the dramatic vocabulary. With spoken ads, our ears immediately pick up the rhythm and melody of the words (the “jingles”), the repeated use of sounds (“Built better by Bloggs!”), and any melodramatic tones of voice. In neither case do we notice the role of grammar in making the words cohere, and yet it is critical. If we want to explain the effect of an ad, a newspaper article, a prayer—any distinctive use of language—then we have to pay careful attention to the grammatical features that give these styles their structure and coherence.

Explanations are what matter. It’s never enough to simply describe the features of a style. We also need to ask why these features have developed in the way they have. In the case of law and religion, we have to go back into history to see the reasons—to do with case-law precedents and biblical sources. In the case of sports commentary we look to the ongoing action to explain the style. With ads, we have to enter the minds of the sales and marketing teams, whose aims are fourfold:

To get us to notice the ad

To maintain our interest so that we want to read it or listen to it

To remember the name of the product

And then, of course, to buy it

Accordingly, a more judicious grammatical approach can be of benefit, in that it can help us think critically about the subtly persuasive ways in which advertising language operates.

Something works “better”? That’s an unspecified comparative.

Better than what? When? Where? This is economic linguistics.

Grammar can save us money.

Featured image credit: “grammar-abc-dictionary-words” by PDPics. Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Breaking the rules of grammar appeared first on OUPblog.

The Red Cross in Nazi Germany

Built on the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was founded to protect the lives and dignity of victims of armed conflict and violence and to provide them with assistance. But despite being one of the world’s most revered aid organizations, the ICRC has a complicated and unsettling history.

The following excerpt from Humanitarians at War examines the disconnect between the ICRC and German Red Cross during the Holocaust.

Cries for help for concentration camp inmates came soon after Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor. A Jewish refugee in April 1933 wrote to the ICRC in a dramatic letter about the brutality in such camps: ‘I beg you again in the name of the prisoners – Help! Help!’ The writer referred to Dachau near Munich, the first regular concentration camp set up by the Nazis. A major obstacle for the ICRC was legal in nature. As pointed out earlier, the 1929 Geneva Convention protected soldiers, not civilians. As a result, and according to international law, the treatment and welfare of German Jews detained in camps in Germany in the Nazi era were considered to be the internal affairs of that country. Moreover, the ICRC continued to understand its main mission as caring for wounded or imprisoned soldiers. It thus had few legal tools with which to help Jews and other victims of persecution in concentration camps.

“Burckhardt said to his ICRC colleagues that it is ‘dangerous to occupy oneself ’ with the concentration camps and therefore extremely important to act with discretion. The ICRC visit would certainly be used by the Nazis to show how marvellous everything was…”

Soon after the Nazis came to power in Germany, Huber, the long-time president of the ICRC and an experienced lawyer and devoted Christian, decided that his organization should provide aid to detention and concentration camp inmates in Germany. But what could be done and how could it be done? Huber agreed as early as September 1933 that ‘the intervention of the ICRC in Germany in favour of political prisoners is a very delicate question’. At the same time, he was happy that Burckhardt showed an interest in this problem and was willing to take steps. A case should be prepared and discussed with the German Red Cross. The president of the Swedish Red Cross also addressed the issue of Nazi concentration camps with the ICRC and the German Red Cross president. Prince Carl of Sweden pointed to the decision made by the Red Cross family that they had an obligation to care for political prisoners. After stressing the deep friendship between Sweden and Germany he stated that he was acting in ‘the interest of Germany and the humanitarian cause’.

The German Red Cross responded that it took an interest in concentration camp inmates and could visit the camps anytime. The situation there was good, housing and food was satisfactory, sports activities and wellequipped hospitals were provided. The German Red Cross official then even went so far as to write that the living standard in the camps were higher than most of the inmates were generally used too. The Germans then invited the Swedish Red Cross president to visit German concentration camps and to convince himself about the good conditions there. Huber was forwarded this letter by his Swedish colleague. It must have aroused his suspicion since the parallels with Mussolini’s invitation were obvious. He certainly considered a possible Nazi propaganda coup, but he had to save face. If Sweden was about to inspect Nazi camps, the ICRC should do so too. The visit of an ICRC delegation to a number of concentration camps was now seriously considered. The German Red Cross president let Huber know that they had already asked for permission from the German government and had ‘found willing agreement’. Max Huber was probably more concerned than delighted to receive the news. The Nazis were obviously eager to get the ICRC ‘inspecting’ their camps. The German Red Cross made no secret of the fact that Burckhardt was their man of choice: ‘It can certainly be expected that Professor Burckhardt will lead the [ICRC] delegation’.

“German Red Cross official Walther Georg Hartmann, the most important contact between Geneva and Berlin, was often praised as being one of the few remaining humanitarians in the leadership of his organization. Yet even he had been a member of the Nazi Party since 1933.”

Caution was the order of the day during a September 1935 meeting discussing the next steps. Based on his recent experiences with German officials, Burckhardt said to his ICRC colleagues that it is ‘dangerous to occupy oneself ’ with the concentration camps and therefore extremely important to act with discretion. The ICRC visit would certainly be used by the Nazis to show how marvellous everything was, Burckhardt explained to his ICRC colleagues. Of course, he knew what was really going on there and said that he had just recently been made aware of murders in camps. Burckhardt showed himself concerned about the dangers of abuse of the planned inspections—and the potential propaganda value for the Nazis. But the ICRC intervention might also help to improve the situation of the inmates. In contrast to wartime, the argument of reciprocity would not work in the case of concentration camps. Burckhardt asked his ICRC colleagues to carefully balance these pros and cons. Other speakers at the meeting stressed that the visit would probably not change the situation, even though the Nazis cared very much about world opinion, in particular in the views of the United States and Great Britain. The two women in the meeting, Suzanne Ferrière and Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, stated that the ICRC should at least do everything to give news to the families of the inmates. As we saw earlier, Burckhardt’s visit took place and his report contained only a mild critique. His main criticism was that political prisoners and criminals were not separated. SS officer Reinhard Heydrich, soon to be one of the main organizers of the Holocaust, reacted to Burckhardt’s critique in a short letter, where he showed himself listening, but not greatly impressed: ‘From a national socialist point of view political criminals are on the same level as professional criminals; this is also evident from the new penal code.’ ‘Heil Hitler!’

The ICRC quickly realized that very little could be done for political prisoners in Nazi hands, particularly since the national Red Cross Society in Germany had opted to fall in line with the regime—a process known as Gleichschaltung—rather than face being shut down. In many ways the ICRC depended on the cooperation of the German Red Cross to achieve its mission there. The German Red Cross was deeply Nazified and obstructed many attempts of the ICRC to help concentration camp inmates. German Red Cross official Walther Georg Hartmann, the most important contact between Geneva and Berlin, was often praised as being one of the few remaining humanitarians in the leadership of his organization. Yet even he had been a member of the Nazi Party since 1933. Nazi Party files describe him as a ‘political leader’ of the Nazi-aligned association of the German Red Cross and a member in various sub-organizations of the party. These affiliations, interestingly, did not hinder his postwar career for long. In 1950 Hartmann became the secretary general of the refounded Red Cross in democratic West Germany. This may have been due to his relatively moderate position; Hartmann does not appear to have been a fanatical Party man, nor was he directly responsible for war crimes. His superior however certainly was. In 1937 SS-General Dr Ernst Robert Grawitz was appointed leader of the German Red Cross. Grawitz, a fanatical Nazi and close follower of SS leader Heinrich Himmler, was himself deeply implicated in the euthanasia murders of handicapped people and medical ‘experiments’ in concentration camps. Men such as Grawitz in the German organization’s leadership made sure that the actions of his Red Cross colleagues were in line with the policies of the Nazi leadership. The German Red Cross had for all practical purposes lost its independence and neutrality and turned into a National Socialist medical service unit supporting Hitler’s Wehrmacht.

Featured image credit: “Anschluss sudetendeutscher Gebiete” provided by the German Federal Archives. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Red Cross in Nazi Germany appeared first on OUPblog.

I Don’t Recommend Parenthood

Recently a friend of mine expressed an aversion to the screaming kids who were attending a summer camp in classrooms close to her campus office. With a laugh, she said she was happy to have further support for her choice not to have children.

The implication was that if she had children, they would seem like the summer camp kids: noisy, bratty, and not even particularly cute. But I’m ready to bet any amount of money that that’s not true. Her own children would seem vastly more charming and precious—even, dare I say, gorgeous and talented.

More important than seeming extra good-looking and gifted, there’s the fact that your own children simply matter to you more. Aristotle described this well when he said children are, to their parents, like selves, but separate. The sheer fact that I am me makes my affairs important to me in a distinctive way, and children have an importance to their parents that’s comparable to that.

Your own children seem terrific, they’re self-like to you, and there’s one more thing: you’re going to love them in an extraordinary way. Not only is there a special intensity to parental love, but there’s also a constancy to it. There’s always a possibility that romantic love will diminish or disappear, but parental love keeps going and going.

In light of all of all that, either my friend was wrong when she said the unpleasantness of the summer camp kids supported her choice not to have kids, or she was joking. I’m pretty sure she was joking, but if I’m right about what it’s like to have your own kids, should I speak up and recommend parenthood? I wouldn’t hesitate to tell her she’s got to go to Iceland, because I love Iceland and I know she’d love it. If I’m just as sure she’d be delighted with her own child, what’s the problem with also recommending parenthood? “You must go to Iceland! And you must have kids!”

But no, such advice would be misguided. For one, Iceland is going to exist whether my friend visits or not. But the decision she makes about having children, together with her husband, is going to cause a child to exist, or not. So she won’t just have an extraordinary set of feelings about the child she creates, she’ll have responsibility for that child. I can tell my friend she’ll adore her own child, but can’t be so confident that it makes sense for her to assume responsibility for a new person’s life.

And then, to be honest, the extraordinary nature of parental feelings brings both joy and pain. Even if you never personally experience tragedy, the possibility of loss hangs over parents. Anne Lamott expresses this perfectly in her book Operating Instructions: A Journal of My Son’s First Year. She describes her newborn son as sheer “moonlight”, but also has another reaction: he’s ruined her life, because now things could happen that would destroy her. Is parental vulnerability worth it? It’s hard to make the judgment for another person.

The unique character of parental feelings can also have other costs. We love our children in such a way that they seem self-like, and that can make it all too easy to shift our energies in the direction of our children. It doesn’t even necessarily feel like a sacrifice to exchange successes on the work front for more time with children; or to spend more time with children and less with a partner. But these shifts are probably part of the reason why, despite the delights of parental love, people tend to become less happy after having children, not more happy—a phenomenon explored by Jennifer Senior in her book All Joy and No Fun: The Paradox of Modern Parenthood. The parent-child relationship starts to crowd out other sources of satisfaction, without that dynamic ever being obvious. I can speak to what I think my friend would feel for her own child, but not so much to the way parenthood would alter the whole ecosystem of her life.

Finally, there’s a mutually understood lightness to travel recommendations. You won’t have a worse life if you never go to Iceland. We all know that. In contrast, there is a heavy, normative undercurrent to discussions about whether people have children. The dominant assumption is still that you should—that childbearing is a crucial life stage for everyone. And so there’s no saying, lightly, that you must have a couple of kids, like you must visit Iceland. To recommend parenthood at all is to risk being taken as seriously critical of any other choice.

And so I will stick to travel advice. Though being a parent is more important to me than all the great trips put together, it’s not something I or anyone else can recommend.

The post I Don’t Recommend Parenthood appeared first on OUPblog.

July 28, 2017

How well do you know film noir?

In Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema, film studies professor Todd Berliner explains how Hollywood delivers aesthetic pleasure to mass audiences. The following quiz is based on information found in chapter 8, “Crime Films during the Period of the Production Code Administration.” The chapter shows how the ideological constraints of the Motion Picture Production Code shaped the aesthetic properties of an entire body of crime films of the studio-era in Hollywood, a set of films now commonly known as film noir.

Quiz image: Bogart and Bacall in The Big Sleep. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Jane Greer and Robert Mitchum in Out of the Past. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know film noir? appeared first on OUPblog.

The challenge of Twitter in medical research

Recent years have seen an unprecedented surge in the use of social media. I still fondly recall how as a newly qualified doctor in 2001, I could afford to buy my first mobile phone. It lacked functionality beyond making phone calls and telling the time. It was also slightly too large for any reasonable sized pocket. Contrast this to today, when my mobile phone has become an essential part of my life, providing not only telephone communication, but also access to emails, medical reference applications, and soon I expect to be able to access my hospital’s electronic record via my phone as well.

One advantage to the clinician of the technological revolution is the rapid access to medical information. Every morning I spend ten minutes over coffee looking through the latest Twitter feeds from the major medical journals, to skim through what research might be emerging in fields other than my own niche (I still enjoy reading the paper editions of journals to cover my specialist area).

One morning, as I was browsing the conveniently short summaries from reputable sources such as the @NEJM or @TheLancet, I spotted a comment about an article I had already read in full, and it struck me that the 140 character-summary that I was provided with was very misleading. The original article was a trial of methotrexate in juvenile arthritis, and the study failed to meet the pre-specified primary endpoint. However, reading the full paper reveals some important nuance, and in reality the research provided strong evidence for a benefit of methotrexate.

The great challenge of Twitter is sharing something eye-catching and relevant. The eye-catching aspect might be achieved by an image (for example the pigeon displayed with this blog, which if anyone is curious can be found at the top of a car park in Frank’s Café in Peckham). However, the ‘relevance’ of a tweet is harder to understand. Sometimes journals simply tweet a statement that research has been published on a topic, but not alluding to what the conclusions might be – forcing the reader to go to the original article. However, oftentimes, the twitterer (is that a word?) will add their own judgement about what the research has shown. And if the twitterer uses the handle of a respected journal, who am I to dispute their opinion?

Cellphone by Free-Photos. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Cellphone by Free-Photos. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Of course, this opens a can of worms… as upon closer inspection it becomes apparent that Twitter authors are frequently anonymous, and the ‘editorial control’ of Twitter is equally opaque. Worse still, the twitterer may ‘retweet’ someone else’s opinion, leading to a sometimes amusing re-enactment of the childhood ‘whispering game’. Adding to this, the reality is that 140 characters are usually not sufficient to provide enough insight to form a judgement upon a piece of research, and it starts to make me doubt the value of Twitter in keeping up to date.

That said, I am aware that Twitter is starting to be viewed as a means of dissemination for research, and watch with excitement when articles I have been published get mentioned. If you haven’t heard of Altmetric, you might be interested to look it up; Altmetric is a relatively recent addition to the measures of academic dissemination that captures the reach of research outside of the medical literature (e.g. news channels, newspapers, Twitter, Facebook etc.). One catch is, you must always remember that the amount of attention research receives in the public domain does not distinguish between fame or infamy. Indeed, Altmetric reflects what the public talk about. A source on the inside of the academic publishing world recently advised me that if I wanted to maximise my Altmetric rankings, I would need to publish on Sex or Dinosaurs, or ideally, both.

As more of our profession move to using social media to review research output, we need to learn to both the strengths and weaknesses of the resource. Much in the same way that the public has been alerted to #alternativefacts and FAKENEWS by our world leaders over the last 12 months, the medical profession needs to equally pay attention to how we digest research through the likes of Twitter and Facebook. Good luck.

Featured image credit provided by Dr James Galloway. Used with permission.

The post The challenge of Twitter in medical research appeared first on OUPblog.

July 27, 2017

The price of travel: is it worth it?

Travel continues to be one of the most sought-after experiences in life. But is it really worth the financial investment and time commitment? In the following excerpt from The Happy Traveler, psychologist Jaime Kurtz considers the cultural allure and transformative power of travel.

As I set out to unpack the challenges of happy travel, I first had to confront my assumption that travel truly is a worthwhile investment of time and money. We certainly seem to think it is. When people sit down to construct a bucket list, travel goals shoot right to the top. A quick browse through the website bucketlist.org reveals a deep longing for far-flung adventures: taking a hot air balloon ride, seeing Niagara Falls, swimming with dolphins, visiting all seven continents, and even throwing a dart at the map and going wherever it lands.

Why? For one, travel is a life-in-miniature, a bookended period of time in which we experience a wealth of highs and lows. As the Danish writer Peter Høeg said, “Traveling tends to magnify all human emotions.”

From crippling fatigue to exuberance, from a search for solitude to shared belly laughs and deep connections, from cultural bumblings to heightened understanding of the world outside of ourselves: it’s all there, and many of us consider that full range of inner experiences to be essential for a well-lived life.

Poster for Wild (2014), based on Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail by Cheryl Strayed. Credit: Fox Searchlight Pictures. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.

Poster for Wild (2014), based on Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail by Cheryl Strayed. Credit: Fox Searchlight Pictures. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.Our reverence for travel is also woven deeply into our cultural ethos. America’s short history can be summed up as one of movement and expansion. From the early explorers venturing to the New World to nineteenth century author Horace Greeley’s advice to “go West, young man,” from Kerouac’s iconic On the Road to Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods, we are captivated by travel and believe in its restorative and transformative powers.

Elizabeth Gilbert’s 2006 runaway hit Eat Pray Love, in which the author spends a year discovering herself in Italy, India, and Indonesia, propelled countless women onto the path to self-awareness, healing, and empowerment. Tourism to the areas Gilbert visited skyrocketed on the heels of her book’s success. Ten years after its release it even inspired the essay collection Eat Pray Love Made Me Do It: Life Journeys Inspired by the Bestselling Memoir. More recently, Cheryl Strayed’s best- seller Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail chronicled her arduous and transformative three-month hike through rough California and Oregon terrain. Because of the number of women seeking a glimmer of this redemption for themselves, the trail has seen a spike in foot traffic since the book and subsequent Reese Witherspoon film were released. One hiker said, “It makes your own personal struggles and problems seem so small. Starting a new life for her was finding herself on this trail and I kind of was in that same point in my life. It’s such an empowering story for women. It will encourage a lot of people to find themselves on a trail.”

Indeed, so many of us are seeking to better ourselves and to come into deeper acquaintanceship with ourselves. We desire that elusive something that will serve as a catalyst for clarity, inspiration, personal growth, or a renewed sense of wonder. And with these narratives as evidence, we have come to the collective conclusion that this something lies elsewhere. To find it, we must take a break from our lives of routine and set off in search of something wholly different, a place where we can test out slightly altered versions of ourselves, free from the constraints of daily life. Through this process of exploration we might just be transformed or revived by the trail, the beach, the foreign city, or the open road.

And even if we can’t jet off to our dream destination, the spark of travel’s life-changing promise can live in us. Frances Mayes’s 1996 memoir Under the Tuscan Sun chronicled her restoration of a neglected Italian farmhouse and inadvertently ignited an obsession for all things Tuscan, from Subway’s Tuscan Chicken Melt to rustic bathroom tiles and hardware to Beneful’s Tuscan Style Medley dog food. Lacking the wherewithal to buy and restore a crumbling Italian villa a la Mayes, we can still live out a small bit of the fantasy through our food, furniture, and housing fixtures.

Featured image credit: “holidays-car-travel-adventure” by Alex Mihis. CC0 public domain via Pexels.

The post The price of travel: is it worth it? appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering the life and music of Antonio Vivaldi

For many who at least known his name, Antonio Vivaldi is the composer of a handful of works heard on the radio or a drive-time playlist of 100 Famous Classical Pieces, featured in TV (and internet) commercials, movies and concerts by students, amateurs, and professionals. Pieces such as The Four Seasons (featured prominently in Alan Alda’s 1981 film, The Four Seasons), the Gloria in D RV 589 and the Violin Concerto in A Minor Op. 3 No. 6 (familiar to most students of the Suzuki Violin Method) are staples of the repertoire and frequently rank high on lists of popular classical music. As for the composer, the most widely known aspects of his biography have been that he had red hair, was a priest (nicknamed “The Red Priest” in his own lifetime), and that he taught at and wrote music (a lot of music) for an all-girl orphanage in Venice and directed the girls during their concerts.

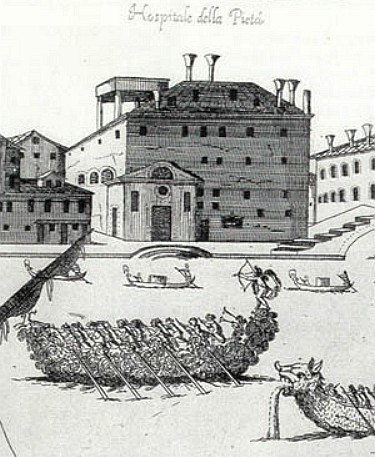

To Vivaldi scholars, this image is partly misconstrued and too limited to do justice to his historical importance and artistic legacy. For one thing, the popular perception of Vivaldi’s employment history is hampered by insufficient awareness of the details of the function and operations of the major Venetian welfare centers (ospedali grandi). It is true that Vivaldi was, at various times in his career, contracted by the governors of the Ospedale della Pietà as needed for musical services ranging from teaching violin and viol to providing new musical compositions and leading rehearsals when possible (in addition to performing other, non-contract duties for which he occasionally received a gratuity, such as when he acted as unofficial supervisor of choral music, the maestro di coro). However, as the Venetian-based scholar Micky White pointed out when investigating the surviving records of the wards of the Pietà (which cared for foundlings), the institution accepted boys and girls who were often raised by foster families until they were of suitable age to be apprenticed (boys) or returned – usually permanently – to the institution (girls). Records indicate that the female musicians who were performing Vivaldi’s music were mostly adult women and the music ensemble was generally directed by skilled members of the ensemble. Thus, the image of Vivaldi as the equivalent of an orchestra and choir teacher at a young girls’ boarding school is factually inaccurate and historically anachronistic.

The popular image of Vivaldi’s career also tends not to accommodate his extensive experience as an operatic impresario (hiring, amongst others, Canaletto’s father to design and paint stage sets), his employment as director of secular music for Prince Philip of Hesse-Darmstadt (in residence in Mantua), as a violin instructor for traveling nobles and aspiring professional violinists, as a composer accepting commissions for vocal and instrumental works on a free-lance basis, as a violinist who often performed with his father, or as a tutor and champion to the singer Anna Girò. These activities had an equal or even greater impact on musical life in European orbits than his work at the Pietà.

Drawing of the Pio Ospedale della Pietà in Venice where Vivaldi taught. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Drawing of the Pio Ospedale della Pietà in Venice where Vivaldi taught. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.More importantly, Vivaldi enthusiasts know that Vivaldi’s large corpus of works yields many delights and surprises for the inquisitive explorer. For one thing, the recent explosion of interest in Vivaldi’s operas has unveiled a world of great emotional vitality, instrumental colors, and fertile musical imagination, with moods spanning from the utmost delicacy to impassioned rage, and settings as far apart as China (Il Teuzzone, 1719) and the Aztec empire (Motezuma, 1733). Fans of the film Shine (1996, dir. Scott Hicks) may be familiar with the serene opening movement of the motet Nulla in mundo pax sincera RV 630, but there are also the sharply-etched contrasts in the second movement of the recently discovered Dixit Dominus RV 807, and the charming earnestness of the first movement of the Salve Regina RV 617. Vivaldi is also the composer of numerous chamber cantatas and serenatas (allegorical works for voices and instruments, often performed outdoors to commemorate special events), including one serenata – La Senna Festeggiante RV 693 – where the personified river Seine sings.

Surprises also exist in the instrumental works. Take, for example, the Violin Concerto in D RV 210 (Op. 8 No. 11), which is one of nearly 100 pieces where Vivaldi uses the concept of fugal imitation (more often associated, in music history books, with Bach and Handel rather than their Italian contemporaries). Other works include theme and variation form, traces of French stylistic elements, special effects (such as re-tuning the strings of the violin), written-out cadenzas, and surprising harmonic twists. In writing for larger ensembles, Vivaldi often treated each instrumental part as a flexible resource, changing the relationship between parts (and the number of independent parts) from one musical phrase to another, thereby making smaller scale formal units more sharply distinguished and more readily intelligible (see, for instance, the finale of the Violin Concerto in G RV 314).

The popular image of Vivaldi formed in the mid-20th century has proven remarkably tenacious, despite significant research that has corrected or re-framed important aspects of his story. Perhaps the sheer quantity of his output has impeded greater familiarity with his artistic breadth. Does the model of a music educator for younger girls resonate more strongly for many of today’s audiences than the actual historical relationship between Vivaldi and the musicians at the Pietà? Is it easier to remember (and market) a simplistic, constructed image of Vivaldi rather than the messy, incomplete picture transmitted in the historical record?

Featured Image credit: anonymous portrait assumed to be of Vivaldi. International Museum and Library of Music of Bologna, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Remembering the life and music of Antonio Vivaldi appeared first on OUPblog.

More than an Amazon: Wonder Woman

Please note that this blog post contains spoilers.

This summer’s epic blockbuster, Wonder Woman, is a feast of visual delights, epic battles, and Amazons. The young Diana, “Wonder Woman,” is, we quickly learn, no ordinary Amazon. In fact, though she is raised by the Amazon queen Hippolyta and trained to be a formidable warrior by her aunt Antiope, both of whom are regularly featured Amazons in Greek myth, she turns out to be not an Amazon at all but a god, whom Zeus has given to the Amazons to raise. (In true 21st century feminist fashion, she is called a god instead of a goddess.) As Diana is a god, her superhero feats are not surprising, but even the rank and file Amazons of Wonder Woman’s Themiscyra live up to their ancient reputation of being ‘faster, smarter, and better than men.’ In the scene that is most reminiscent of Greek legend, an Amazonomachy, or battle between Amazons and men, the Amazons soar off of the cliffs of their island to defeat their enemies. With a combination of spears, swords, bows, arrows, and magical ropes, they defeat the Germans, whose World War I era technology is no match for the Amazons’ panoply. The thrill of victory is short-lived, however, as Antiope, the greatest warrior of the Amazons, is slain by a German bullet in the last scene of the Amazonomachy.

Unlike Diana, the Amazons are mortals, as Antiope’s death painfully illustrates. In ancient Greek lore, Amazons fought like other mortals, even though they were called the “daughters of Ares,” the god of war. This epithet is probably metaphorical, telling us of the bellicose nature of the Amazons. The Amazons of ancient Greek lore seemingly existed to make war, whereas their counterparts in Wonder Woman, though they train for warfare daily, have been put on earth by Zeus for a different purpose: to bring peace by defending all that is good in the world. In fact, rather than being the “daughters of Ares,” they are his sworn enemies. Perhaps this twist should not come as a surprise; war was a way of life for the ancient Greeks, but in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the potential for mass destruction should make a pacifist of us all.

Wonder Woman (2017 film).jpg by Warner Bros. Pictures. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.

Wonder Woman (2017 film).jpg by Warner Bros. Pictures. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.Given the mission of her Amazon tribe, it is not surprising that when Diana leaves her Amazon homeland to enter the world of men that she and her multicultural posse carry out a postmodern agenda of ending war and squelching oppression, even though Diana and her new male comrades have differing ideas about how to carry out such tasks. Postmodernism quickly turns to postcolonialism as we meet one of Diana’s new comrades-in-arms, a Native American generically called “Chief,” who tells Diana of the woes his people have suffered at the hands of Europeans. Diana is moved by his story as to why he has left his homeland, and the epic takes on global proportions.

Indeed, the film moves quickly from the local to the global: from the all-woman paradise of Themiscyra to the male-dominated, oppressive battlefields of World War I. But the best is not saved for last. As the film begins to unfold, Themiscyra, the fabled city of the Amazons, stuns the viewer with its breathtaking beauty. Themiscyra is depicted as the chief settlement of “Paradise Island,” replete with lush landscapes, waterfalls, and battle-training for women only. Such an Amazon island was mentioned in Callimachus’ Argonautica as a place, somewhere in the Black Sea, where the Amazons went to worship none other than the god Ares at a sacred black rock (though it was never the site of Themiscyra, which lay in the heartland of Amazon country on the river Thermodon in modern Turkey).

Though the film certainly starts in a “queer” locale — that of Amazon women who shun men, it drifts quickly into heteronormativity as Diana falls in love with Steve Trevor. In this sense it is a modern version of the tale of Antiope, the ancient Amazon who falls in love with the beguiling Greek Theseus, but with a very different ending. Whereas Antiope marries Theseus and bears his child, Diana ultimately remains single to fight for justice. If patriarchy prevails in the Greek myth, in Wonder Woman it takes a not-so-subtle blow. For instance, Diana tells Steve that she has read all twelve volumes of Clio’s treatise on eroticism, which dictate in true Amazon fashion that men are vital for reproduction but unnecessary for bodily pleasures. Of course, the ideas expressed in these alleged tomes echo the legends of the Amazons, who, in Greek lore, only used men to procreate once a year, or, if they did find them a bit more necessary on a day-to-day basis, kept them as domestic slaves. And while Clio was the Ancient Greek muse of history, not eros, ancient Greek sex manuals did once exist. A manual attributed to a woman author named Philaenis may have discussed women pleasuring other women, as may have other such volumes, all now lost to us. In any event, such knowledge does not prevent Diana from falling for Steve Trevor, even though circumstances, in the end, keep them apart.

Wonder Woman takes a feminist turn whenever possible, rethinking stereotypical male and female gender roles. Although Diana doesn’t quite become the de facto leader of the otherwise male cadre she joins to fight the Germans, she is accepted on her own terms as a warrior. Having left Paradise Island naively hoping just not to combat evil but to end it altogether, Diana learns all too quickly that the purpose of her Amazons, to bring peace to earth, is futile: although she and her new male friends manage to bring an end to World War I, ultimately Diana learns that free will reigns supreme. The young Diana’s assertion that only love can save the world keeps her fighting for justice nevertheless. As a prequel to the once-popular TV series, the movie does not fail to deliver when it comes to women in action, and, even if the ending is not as uplifting as one might hope, flying, fighting Amazons do make for great fun. Like the Amazons of Greek lore, Diana’s Amazons demonstrate that women can be formidable foes. While Wonder Woman may be fanciful in its representations of the Amazons, the questions that it raises are real, like those raised by authors of old. Can and should women be trained for combat? The ancient Roman author Musonius asserted, long ago, that the Amazons were proof that women could be trained to make war, and, perhaps most importantly, to defend themselves. While Diana is no ordinary Amazon, she is an Amazon at heart, and the message that she delivers is powerful: women can fight back.

Featured image credit: Villa Cimbrone a Ravello. Photo by Mentnafunangann. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post More than an Amazon: Wonder Woman appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers