Oxford University Press's Blog, page 339

August 5, 2017

Philosopher of the month: Sir Karl Raimund Popper [timeline]

This August, the OUP Philosophy team honours Sir Karl Raimund Popper (1902–1994) as their Philosopher of the Month. A British (Austrian-born) philosopher, Popper’s considerable reputation comes from his work on the philosophy of science and his political philosophy. Popper is widely regarded as one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century.

Born to a middle-class Jewish family in Vienna, Popper studied mathematics, physics, and psychology at the University of Vienna, graduating with a doctorate in psychology in 1928. His first book The Two Fundamental Problems of the Theory of Knowledge was shorted down to become arguably his most famous work and also the first to be published by the philosopher, Logik der Forschung (1934). The Vienna Circle became interested in Popper’s work after this despite it contesting some of their basic concepts. Popper shared their interest in distinguishing between science and other activities, but in contrast to them never supported the idea that non-scientific activities were meaningless. He instead disapproved of pseudo-science, believing that the fundamental feature of a scientific theory is that it should be falsifiable. An example of this pseudo-science which could not be falsified was Freud’s psychoanalytic theory which Popper contrasted with true science from the likes of Einstein.

Aware of the Nazi threat to Jews, Popper emigrated to New Zealand in 1937 to take up a lectureship at Canterbury University. Popper stayed in New Zealand until after the war and went on to publish Open Society and Its Enemies in 1945. This attacked historicism in political philosophy, blaming the works of Plato, Marx, and Hegel for the events of World War II. With the help of his friend Friedrich August von Hayek, Popper obtained a readership at the London School of Economics in 1946. Popper spent the rest of his life in Britain and during this time was made a fellow of both the Royal Society and the British Academy, a Membre de I’Institute de France, and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1965. He spent the latter half of his life placing his theory of error-seeking in both science and politics within a generalized theory of evolution and also went on to translate Logik der Forschung to English himself, publishing it as The Logic of Scientific Discovery in 1959. Popper retired from the London School of Economics in 1969, but continued publishing work up until his death in 1994.

For more on Popper’s life and work, browse our interactive timeline below:

Featured image credit: Panorama Vienna, Austria. Photo by Michal Jarmoluk. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of the month: Sir Karl Raimund Popper [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 4, 2017

Diet and age-related memory loss [excerpt]

Age-related memory loss is to be expected. But can it be mitigated?

There are many different steps we can take to help maintain and even improve our memories as we age. One of these steps is to make a few simple dietary changes. The following shortened excerpt from The Seven Steps to Managing Your Memory lists dietary basics that can benefit memory.

Omega- 3 fatty acids

Omega- 3 fatty acids (often shortened to “omega- 3s”) are important for a number of functions in the body, including the proper function of our brain cells and reduction of inflammation. Although our bodies make many of the fats we need, we cannot make omega- 3s, and so we need to get them from food. There are three main types of omega- 3s and, because you may have heard claims about each of them, we’ll mention them briefly (despite their long names). Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) has been associated with brain health and cognitive function, control of inflammation, as well as heart health. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) has been associated with heart health and control of inflammation. Alpha- linoleic acid (ALA) is a source of energy and also a building block for both DHA and EPA. Scientific studies examining the benefits of omega- 3s have been mixed, but some research suggests that they may benefit brain health.

Our recommendation is to make sure your balanced diet does include some omega- 3 fatty acids. The most common sources of omega- 3s include fish (particularly fatty fishes such as salmon and tuna), walnuts, green leafy vegetables (such as kale), flaxseeds, and flaxseed oil. Other foods are now being fortified with omega- 3s. You may find eggs, milk, juice, and yogurt fortified with omega- 3s in your local grocery store.

The Mediterranean diet is low in saturated fats (the “bad” fats) but encourages the intake of monounsaturated “good” fats that lower the “bad” cholesterol. Credit: “olive-oil-salad-dressing-cooking” by stevepb. CC0 publi domain via Pixabay.

The Mediterranean diet is low in saturated fats (the “bad” fats) but encourages the intake of monounsaturated “good” fats that lower the “bad” cholesterol. Credit: “olive-oil-salad-dressing-cooking” by stevepb. CC0 publi domain via Pixabay.Vitamin D

Vitamin D is essential for brain health. In one study, individuals with low levels of vitamin D were about twice as likely to develop dementia and Alzheimer’s disease compared to those whose levels were normal. Most older adults don’t have enough vitamin D. Although you can make vitamin D through your skin, to do so you would need to spend a lot of time outside without sunblock, which you shouldn’t do. We recommend a daily intake of 2,000 IU of vitamin D3, usually from supplement pills. You can also get vitamin D from fatty fish (such as tuna and salmon), portobello mushrooms grown under an ultraviolet light, and foods fortified with vitamin D including milk, cereal, and orange juice. Be sure to read the label to see if the product you buy is fortified or not. Lastly, there are some important interactions between vitamin D and some prescription medications, so you should speak with your doctor prior to taking vitamin D supplements.

Antioxidants

Antioxidants can defend the body against the harmful effects of free radicals— chemicals that can damage cells, including brain cells. Some of the most common antioxidants are vitamins A, C, and E, along with flavonoids and beta- carotene. Most studies looking at the impact of antioxidant supplementation through pills have offered little support that taking these antioxidant pills improves thinking and memory. In fact, taking high doses of antioxidants in pill form can be problematic, with some studies showing that high intake of antioxidants is associated with an increased risk of cancer and death and can negatively interact with certain medications. Thus, although some clinicians would recommend taking antioxidant supplements, such as vitamin E, we do not.

The evidence suggests that eating antioxidant- rich foods, such as fruits and vegetables, can reduce the risk of chronic health conditions such as heart disease and stroke, which, in turn, can improve the health of the brain. Many researchers now believe that it is the types and variety of antioxidant foods that people are consuming that matters most, rather than simply the total amount of antioxidants consumed. We therefore recommend eating fruits and vegetables as part of a balanced diet.

Mediterranean diet

One of the most important ideas that has emerged from the scientific literature is that it may not be any one dietary item that makes a difference in the health of our brains. Instead, it is likely that the complex combination of nutrients obtained through a balanced diet is best. The Mediterranean diet is one such balanced diet that has shown promise for brain health. This diet calls for high consumptions of fruit, whole grains (like bulgur, barley, and brown rice), beans, and vegetables at every meal. The diet is low in saturated fats (the “bad” fats) but encourages the intake of monounsaturated “good” fats that lower the “bad” cholesterol. These healthy fats, found in olive oil, avocados, and nuts, should be eaten frequently. Fish is recommended at least twice a week. Low to moderate amounts of dairy products such as yogurt and cheese can be consumed daily or weekly. Red wine is also a staple of the Mediterranean diet. Red meat and sweets (such as candy, cookies, cake, and ice cream) should be consumed sparingly.

One way the Mediterranean diet helps the brain is by reducing risk factors for stroke such as high cholesterol and diabetes. One study showed that brain volumes were larger for those who followed the Mediterranean diet, equivalent to being five years younger! Other studies have shown that people who eat a Mediterranean diet have a lower risk of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease dementia compared to those who ate a more typical diet. Not all studies support the idea that the Mediterranean diet is good for cognition and reduced risk of memory loss, but many studies do, and none of the studies reported any side effects that would caution against adopting such a diet in an effort to keep the brain healthy. We therefore recommend a Mediterranean- type diet to everyone looking to modify their lifestyle in a way that benefits brain health.

Featured image credit: “food-avocado-healthy-fresh” by gutolordello. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Diet and age-related memory loss [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

That someone else: finding a new oral history ancestor

In April Allison Corbett shared her reaction to Dan Kerr’s article “Allen Nevins Is Not My Grandfather: The Roots of Radical Oral History Practice in the United States,” explaining the roots of her own radical oral history practice. Today we hear from Benji de la Piedra, as he shares another oral history origin story from his research on the Federal Writers’ Project. Enjoy his insights, and check out our call for submissions here, if you’d like to contribute your own reflections.

“Ever since the Federal Writers’ Project interviews with former slaves in the 1930s, oral history has been about the fact that there’s more to history than presidents and generals.” –Alessandro Portelli

Dan Kerr acknowledges in his article, “Allan Nevins Is Not My Grandfather,” that most historians of oral history tend to dismiss the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) as a mere “prehistory” of the field, because the vast majority of FWP interviews were recorded with pen and paper rather than with machine. However, in the research that I conducted towards my M.A. thesis in oral history, I discovered for myself the untapped potency that the FWP holds for oral historians who seek an origin story more closely aligned with the field’s impulse towards effecting social change.

Started in 1935 as part of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, the Federal Writers’ Project put thousands of unemployed writers to work on assignments that served the FWP’s ambitious cultural agenda: to foster a badly needed renewal of the United States’ self-image, and to forge a new American unity through celebration of unrecognized American diversity. As Jerrold Hirsch writes, the cohort of public intellectuals directing the Project—Henry Alsberg (national director), Sterling A. Brown (editor of Negro affairs), Morton Royse (social-ethnic studies editor) and Benjamin A. Botkin (folklore editor)—sought to imbue the nation’s public life with “a cosmopolitanism that encouraged Americans to value their own provincial traditions and to show an interest in the traditions of their fellow citizens.”

FWP writers pursued this pluralistic aim through a practice that I think of as proto-oral-history fieldwork. All across the country, the writers spent much of their workdays conducting interviews with people traditionally excluded from the process of history-writing: the working poor, immigrants, women, and people of color (including those who had been born slaves). The Project intended to use the testimony furnished by the interviews as fodder for both an American Guide Series—a set of guidebooks, one for each of the state in the Union—and Composite America, a series of cultural anthologies that would reveal overlooked strands and narratives of American culture to the wider public.

If you are an oral historian seeking a new grandfather—one with greater aesthetic concerns, democratic objectives, and community-based ethics than Allan Nevins—I recommend you check out the leading soul and intellect of the FWP’s interviewing program: B. A. Botkin (1901 – 1975). I first encountered Botkin in the introduction to Ann Banks’ First Person America, a book that curates about eighty extracts from the almost 10,000 interviews produced by FWP fieldworkers, and was the result of Banks’ own pioneering effort to survey and catalogue the entire collection of interviews, which had sat unexamined in a set of file cabinets at the Library of Congress for more than thirty years after the Project was disbanded.

In the introduction to her book, Banks celebrates Botkin’s “unconventional approach to the subject of folklore” as a crucial influence on the Federal Writers’ interview methodology. Botkin “wanted to explore the rough texture of everyday life,” Banks writes, “to collect what he called ‘living lore’…Again and again, he stressed the importance of the process of collecting narratives. The best results, he wrote, were obtained ‘when a good informant and a good interviewer got together and the narrative is the process of the conscious or unconscious collaboration of the two.’”

Banks goes on, “Benjamin Botkin called for an emphasis on ‘history from the bottom up,’ in which the people become their own historians. He believed that ‘history must study the inarticulate many as well as the articulate few.’ The advent of tape recorders in the years following the 1930s has refined the practice of what has come to be called oral history and made it possible for Botkin’s goals to be pursued more easily.”

In other words, Botkin instructed the Federal Writers to approach their interviews dialogically, as intersubjective exchanges built upon a shared authority, decades before these central concepts were so named in the field of oral history. Botkin saw the potential for this interview technique to drive a radically inclusive rehabilitation of American life, decades before the popular education and people’s history movements that Kerr recovers in his article.

Botkin instructed the Federal Writers to approach their interviews dialogically, as intersubjective exchanges built upon a shared authority, decades before these central concepts were so named in the field of oral history.

Botkin deeply appreciated the pedagogical and integrative function of the work that we now call oral history. His desire to make the archive produced by FWP fieldworkers accessible to an “ever-widening public,” to “give back to the people what we have taken from them and what rightfully belongs to them in a form that they can understand and use,” led him to declare the FWP’s interview program “the greatest educational as well as social experiment of our time.” While the outcomes of this experiment varied in quality, social justice-oriented oral historians will continue to find Botkin’s impressive body of thought a particularly germane touchstone for their work. Why? Because Botkin’s method and theory of interviewing took relationships seriously. Botkin prized the meaningful encounter—the “mutual sighting,” to use Portelli’s phrase—as the foundation for not only a successful interview, but also a healthy democracy.

Botkin refined this ideology in the years following his tenure with the FWP, when he elaborated a public-facing research practice that he called “applied folklore.” Botkin used this term broadly, “to designate the use of folklore to some end beyond itself…into social or literary history, education, recreation, or the arts.” He identified the basic impulse of applied folklore as “the celebration of our ‘commonness’—the ‘each’ in all of us and the ‘all’ in each of us…an interchange between cultural groups or levels, between the folk and the student of folklore.” And anticipating the highest aims of contemporary historical dialogue work, Botkin writes, “The ultimate aim of applied folklore is the restoration to American life of the sense of community—a sense of thinking, feeling, and acting along similar, though not the same, lines—that is in danger of being lost today. Thus applied folklore goes beyond cultural history to cultural strategy.”

In my recent work as Project Trainer for the DC Oral History Collaborative, I have constantly recalled Botkin as a personal guide. I have encouraged my interviewers to be themselves in the encounter; to relax their impulse to control the dialogue and instead follow, as Botkin instructed his Federal Writers, “the natural association of ideas and memories”; and to practice framing their narrators as valuable witnesses of their neighborhood, school, and migration histories. I have done this in the spirit of fostering what the Federal Writers’ Project aimed for nationally—“an inter-regional synthesis”—within the densely diverse and still too segregated scope of our nation’s capital.

Featured image credit: “Federal Writers’ Project presentation of Who’s who at the zoo” by unknown, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post That someone else: finding a new oral history ancestor appeared first on OUPblog.

10 facts about fungi

Fungi play an important role for a balanced life of flora, fauna, and humans alike. But are they important for us humans, and how are fungi related to animals? Nicholas P. Money, author of Fungi: A Very Short Introduction, tells us 10 things everyone should know about fungi, and the role they play in the world.

Mushrooms and other fungi release an incredible amount of spores into the atmosphere every year, and contributing up to 50 million tonnes of particulates.

Fungi are more closely related to animals than they are to plants as they both belong to the Opisthokonta taxonomic supergroup.

In contrast to plants, fungi do not have chlorophyll, lack leaves and roots, and never form flowers, fruits, or seeds.

Fungi engage in all manner of close biological associations with other organisms, also called symbiosis. They include relationships that benefit either the contributor (mutualism) or in which one participant benefits at the expense of the other (parasitism).

Fungi are the most important cause of plant disease. Sometimes, the fungus feeds on living tissues without killing the plant. Other fungi begin by killing plant cells and feed on their dead contents. And still others employ both strategies back to back.

Most fungi are omnivores and are very effective at breaking down animal proteins. They are also capable of infecting the tissues of animals with weakened immune systems.

Human interactions with fungi can be harmful in many ways including poisonings, exposure to ‘mycotoxins’ produced by fungi that cause food spoilage, and allergies stimulated by inhalation of airborne spores.

There are more than 70,000 species of fungi described by mycologists.

Over 90% of the described fungi are classified either as basidiomycetes, which produce mushrooms or smuts that cause plant disease, or as ascomycetes, which includes yeast or truffles.

Some of the oldest biotechnological uses of fungi include the cultivation of edible mushrooms, and brewing and baking with yeast. In modern times, fungi are used to produce antibiotics, cyclosporine, and other medicines.

Featured image credit: close up fungi mushrooms by Pexels. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post 10 facts about fungi appeared first on OUPblog.

August 3, 2017

Deep in the red

Yesterday, the second of August, was Earth Overshoot Day for 2017. This date “marks the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year.” As of today, we carry a planetary-sized debt. We are running in the red. This most horrible of days only started in 1971. Before that, humans did not have the population size nor the technological capacity to ‘out-eat’ our larder.

Each year the shortfall is deeper. This spiraling trend leads to more intensive over-harvesting the next year, like drawing down capital from your savings. We should be living off interest, but as a planetary society, we don’t know how to budget.

We have exhausted the biocapacity of the Earth. Currently, if everyone in the world were to live with the luxuries Australians have, we’d need the resources of 5.5 Earths to provide for them. We fall short every year, but it wasn’t always this way.

Some places in the world are doing far better than others, but it doesn’t make up for those who are in the worst debt. Brazil has such huge natural resources is it still in surplus. South Korea needs 8.8 South Koreas to meet the needs of its population. Japan needs 7.1. You can explore how ‘in the red’ each country is by trawling through openly accessible data.

“We have exhausted the biocapacity of the Earth.”

Earth Overshoot Day has been calculated since 2006, but data go back to 1969. That already magical year is also famed for being the penultimate year of global bounty. Predatory humanity then ate the surplus. The first Earth Overshoot Day occurred on 21 December 1971, an ominous day in the history of civilisation.

Alarms bells should have been ringing from the roof tops, but no one was calculating our risk of ecological bankruptcy. We continued ploughing through our savings. John Lennon died in 1980 and in that year, Earth Overshoot Day was arriving in November. When Princess Diana died in 1997, it was in September. By 2009, the year the world lost Michael Jackson, Earth Overshoot Day was in August.

What if we cared about the loss of Earth’s biocapacity as much as we did about the loss of our most famous faces? The dire question is how deep into the red can we go without global catastrophic consequences?

We will overshoot in July soon, the seventh month of the year. The twentieth of July is a landmark threshold. When Apollo 11 landed that day in 1969, we lived free of ecological debt. If we slip to June, we would need two Earths to sustain the planet’s life-support systems at the same level of functioning. Without serious changes in our consumption and carbon-usage patterns Earth Overshoot Day is expected in June by 2030.

Can we turn back Earth Overshoot Day? Seems as difficult as turning back the hands of time. But what will happen if we don’t?

Many people still think we don’t have the power to change things at a planetary level. Here is solid proof we do.

The decrease in biocapacity has almost levelled off in recent years. Efforts are underway to push back the overshoot five days a year until 2050 to bring it back to ‘normal’. A range of solutions are on the table, such as the education of women, but the biggest positive impact will come from dropping carbon consumption through the 2015 Paris Accord on Climate.

We can all contribute by pledging money or our actions. Adopting helpful practices like more vegetarian meals, social ride sharing, or urging politicians to create good policies could help lead to our biggest societal contribution yet: realising the dangers of our collective actions and working to reverse them for future generations.

Featured image credit: The natural resources of the Earth are finite. “Blue Marble Western Hemisphere” from NASA images by Reto Stöckli, based on data from NASA and NOAA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Deep in the red appeared first on OUPblog.

Academy of Management 2017: a conference and city guide

The 77th annual meeting of the Academy of Management will take place this year from 4 August through 8 August in Atlanta, Georgia. This year, the Academy of Management will convey the theme of “At the Interface”, inviting attendees to reflect on the ways interfaces both separate and connect people and organizations. Hosting more than 10,000 students, academics, scholars, and professionals, the Academy of Management meeting will be sure to inspire, challenge, and bring about passionate dialogue and exploration. With a wide variety of panels, workshops, and sessions to attend, we’ve highlighted some of the events that we’re excited about:

Friday, 4 August

Social Class Inequality: Research Perspectives and Networking, 10:15 AM – 12:45 PM, Hilton Atlanta Galleria 6

Exhibit Hall Opening Reception, 6:00-8:00 PM, Hyatt Regency Grand Hall

Master of Management Development Session, 6:00-7:00 PM, Hyatt Regency Kennesaw

Saturday, 5 August

Digital Technologies: A Game Changer for Entrepreneurship?, 9:45-11:15 AM, Hilton Atlanta Room 202

At the Interface: When Managing Projects Meets International Development, 11:15 AM – 1:15 PM, Hyatt Regency Spring

Sites and Contexts of Plural Leadership Workshop, 1:00-2:30 PM, Atlanta Marriott Lobby

Good People, Bad Managers by Samuel A. Culbert Book Signing, 4:00-5:00 PM, OUP Booth #326

Human Relations Reception, 6:00-8:30 PM, Hilton Atlanta Grand Ballroom D

Sunday, 6 August

Interfaces of Individuals, Organizations & Institutions for Creation of Markets & Industries, 10:30 AM – 1:30 PM, Hyatt Regency Embassy Hall

Multiple Perspectives on Open Science Practices Symposium: Myths, Urban Legends, and Realities, 2:00-3:30 PM, Hyatt Regency Techwood

The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Paradox Book Launch Reception, 4:00-5:30 PM at the Sway Restaurant, Hyatt Regency

Monday, 7 August

A Dialogue on Governance in Professional Service Firms Symposium, 9:45-11:15 AM, Hilton Atlanta Room 305

Advances in Cultural Entrepreneurship: Looking Back and Moving Forward, 1:15-2:45 PM, Atlanta Marriott Marquis M303

Leadership at the Interface: Ideologies, Logics and Paradoxes, 4:45-6:15 PM, Atlanta Marriott Marquis Lobby L401

Tuesday, 8 August

Everyone Is Not the Same: Exploring Differential Roles and Relationships in Teams, 8:00-9:30 AM, Hilton Atlanta Galleria 2

Job Design Characteristics and Well-Being, 1:15-2:45 PM, Hilton Atlanta Room 224

President’s Farewell Gathering, 5:00-7:00 PM, Atlanta Marriott Marquis Imperial Ballroom

Whether you’re visiting Atlanta for the first time or returning to the city, there is plenty that the capital of Georgia has to offer. Close to the Academy of Management venues sits Centennial Olympic Park, the perfect location for a breath of fresh air in between events at the meeting. If you’re spending additional time in Atlanta, surrounding the park are tourist features such as the World of Coca-Cola, the Georgia Aquarium, and the CNN Center. The city also hosts a large assortment of museums and cultural centers, including the Fernbank Museum of Natural History, the High Museum of Art, the Center for Civil and Human Rights, as well as the birth place of Martin Luther King, Jr. Finally, no trip would be complete without a sampling of the local cuisine. For a great night out, Ray’s In the City offers upscale seafood and steak as well as live jazz music. For more casual, local fare, check out Gus’s Fried Chicken or Twin Smokers BBQ. Lastly, for some spectacular views of the skyline, visit Nikolai’s Roof for French-Russian cuisine or SkyLounge to unwind after the day.

Don’t forget to come by the OUP booth, #326, throughout the weekend to check out our titles at a special conference discount, online resources, and journals. Follow us on Twitter at @OUPEconomics to stay up to date on Academy of Management 2017. We hope to see you in Atlanta!

Featured image credit: Atlanta Georgia USA City by tpsdave. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Academy of Management 2017: a conference and city guide appeared first on OUPblog.

August 2, 2017

A few more of our shortest words: “if,” “of,” and “both”

The post of 21 June 2017 on the “dwarfs of our vocabulary” was received so well that I decided to return to them in the hope that the continuation will not disappoint our readers. Those dwarfs have a long history and have been the object of several tall tales.

If

Like most subordinate conjunctions, if conveys a rather abstract meaning. Its bulky, bookish synonyms provided (that) and in case of have little virtue. Sometimes it is possible to do without if by inverting the word order, as in “were I (had I been) there…,” “should you ever meet him…” and so forth, but in most cases, when we want to introduce a conditional clause, we say if. The word has a respectable ancestry. Thus, in Old English, we find gif with the puzzling initial g-, pronounced as Modern Engl. y– in yes. (Although this additional y- was not restricted to the conjunction, its appearance is always a riddle.) All “dwarfs” tended to interact with their likes as regards both meaning and pronunciation. For instance, in gif, the initial g- may have been “borrowed” from gē “yea.” German speakers, unless they are linguists, do not know that -r in oder “or” was added to it under the influence of aber “but” and other similar form words. However, Old Frisian also preserved both ef and jef, so that j– was not a mere freak of Old English phonetics. Indeed, Old Frisian had several other forms that will soon make the plot thicken.

How do people coin a conjunction like if? Why should a combination of short i and f refer to a possibility of something happening? Could if be a relic of some longer and less abstract word? The once famous politician Horne Tooke (1736-1812) was also a self-made philologist. His two-volume book The Diversions of Purley had numerous distinguished admirers (purley “purlieu”; the title must have referred to the joys of hunting, but the work’s Greek title Epea pteroenta means “winged words”). Tooke’s career and the reason for his popularity need not delay us here, though even today some people find virtue in his etymologies. According to one of his bizarre ideas, numerous words go back to the imperative of verbs. He suggested that if is an ossified relic of give! in the assumed sense “grant, suppose.” I am mentioning this derivation only because it has been repeated in so many sources.

The famous Horne Tooke, a great admirer of imperative forms.

The famous Horne Tooke, a great admirer of imperative forms.Alongside Engl. if, we find a group of Old Icelandic nouns: if, ef, ifi, and efi, all of them meaning “doubt.” The corresponding verb ifa meant “to doubt”; it alternated with efa. The Icelandic cognate of Engl. if was ef. Old High German had the noun iba “condition, stipulation, doubt.” It would be almost ideal to trace the conjunction if to the dative or instrumental case of a word referring to hesitation and uncertainty. But despite some excellent suggestions the origin of those nouns remains unclear, and, as always, I resort to the law that one obscure (or, let us say, not fully transparent) word cannot shed light on another word of dubious origin. Also, the derivation of such a conjunction as if from a noun would be a most unusual process. Could all those nouns and verbs go back to the conjunction (in order to designate something iffy), rather than the other way around?

The iffy parts of our life are never behind us.

The iffy parts of our life are never behind us.Finally, it is not improbable that if is a stub of some longer word. And indeed, in Gothic (recorded in the fourth century), the cognate of gif ~ if is ibai “whether.” The Gothic form is suggestive, but it too needs an explanation. Perhaps ibai is ib + ai! In this case, the short form is more important than the long one, and we are left with the enigmatic ai. It was the great Indo-European scholar Karl Brugmann who seems to have offered the best explanation of ibai. He isolated two elements in it: i and bai.

While reading the history of the Indo-European languages, one constantly runs into something called pronominal roots (or stems). Among them, the most often mentioned are *i and *e. The asterisks mean that they have not been attested but only reconstructed. In the remote past, we think, such roots were used as the basis of other words. Did they ever exist as independent units? Apparently, they did (for roots are not the flotsam and jetsam of language waiting to be attached to other words), though it would be hard to give details. Did our very remote ancestors go about and, while pointing to the objects around them, shout “i” or “e” (that is, the short i and e of Engl. in and hen)? Perhaps they did. In any case, i- ~ e is part of several well-known pronouns and conjunctions. Among the pronouns, the most obvious example is Modern German es “it,” from et. The second element of the conjunction ibai (i-bai) is then –bai, either an emphatic particle (in Gothic, ba “even though” occurred) or both. Gothic did have bai “both.”

Strangely, Gothic had an even closer cognate of gif than ibai, namely jabai, a compound made up of ja “yea, indeed” and the same bai. One may assume that two such similar words as ibai and jabai interacted and were even occasionally confused in Gothic. But alas, we have no evidence of everyday Gothic, because only parts of the Bible in that language have come down to us. Colonel Pickering, a colleague of Professor Higgins’s in G. B. Shaw’s Pygmalion, was the author of Conversational Sanskrit. As it happened, that worthy officer’s interests did not extend to Germanic.

German had the noun iba “doubt” (see above), but it also had an unquestionable cognate of English if, namely obe and ubi “whether” (Modern German ob; note that in English, whether and if can also alternate, as in “I don’t know whether/if she will come”). We can see that the vowels of if and obe ~ ubi do not match. The German case is not an aberration. Old Saxon had both ef and of, while the Modern Dutch conjunction is simply of. In Old Frisian, we observe the whole panoply: jef, ef, jof, and of. (Do you remember the caveat about the thickening of the plot?) Those who have read the post, referred to at the beginning of the present essay, will recall that the conjunction and also had several variants with alternating vowels, especially in German: unta and inti. The cause of the alternation was ablaut. The same factor will account for the alternation here. Ablaut was an extremely flexible and widely used means of word formation and inflection. Consider our tick–tock, dickery, dickery dock, chit-chat, fiddle-faddle, fee-fi-fo-fum, and the rest? So why not obe ~ ubi ~ (y)if ~ iba? Does that mean that Engl. of is related to if? And what is the ultimate origin of if?

In doubt about the the etymology of the word if.

In doubt about the the etymology of the word if.Let us pretend that we are characters in 1001 Nights. Although dawn has just broken, the fairy tale is not over. The king postpones the execution of the story teller, in order to hear what happened to the characters. If ifs and buts were candies and nuts, what a beautiful etymological dictionary it would be! You already know the story of but (see again the post of June 21), and in the nearest future I’ll tell you all I know not only about if, of, and both but also about nut. For the moment, suffice it to realize that the shorter the word, the longer its etymology.

A scene from “1001 Nights”.

A scene from “1001 Nights”.Featured image credit: “Children look” by Luisella Planeta Leoni, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A few more of our shortest words: “if,” “of,” and “both” appeared first on OUPblog.

The good tax

No one enjoys paying taxes. Remember receiving your first paycheck and discovering how much of your hard-earned money you would be sharing with the government? Most of us recognize that some taxes are necessary. We are happy to have roads, schools, courts, and a military, but don’t feel great about having to pay the taxes that fund them. Although economics recognizes the need for taxes to fund the government, it is pretty clear-eyed about the downside of taxes:

Corporate taxes are problematic because they involve taxing the same earnings twice. Once a corporation has paid taxes on its income, it distributes some of that income to shareholders as dividends–which are then taxed a second time. It would make more economic sense to forget about corporations and just tax shareholders.

Income taxes, particularly in the United States, have so many loopholes that they distort economic incentives. For example, people who would be better off renting a house may decide to buy because buying is cheaper once they factor in that they can deduct mortgage interest payments from their income tax.

Nonetheless, taxes are sometimes good for us, despite the economic drawbacks. One example is the tax on cigarettes.

Smoking is costly for society. According to the US Centers for Disease Control, smoking-related illness costs the United States more than $300 billion per year, approximately the same amount as Americans spend on all prescription drugs combined. The health costs and lost productivity due to cigarettes are estimated to be $19.16 per pack. If a higher tax on cigarettes reduces smoking, this would be a good outcome.

Historically, states were willing to impose “sin taxes,” that is, taxes on items considered to be socially undesirable or harmful like alcohol and tobacco, because demand for these products was generally robust—hence the taxes provided a dependable revenue stream.

More recently, and particularly in the case of cigarettes, a different motivation has come to the fore. If the tax is high enough, it may discourage consumption, which would be a good thing. So, the question is: do higher taxes on cigarettes reduce sales?

Figure 1 plots the adult smoking rate on the horizontal axis and the level of state cigarette taxes on the vertical axis. The tax data in figure 1 do not include a federal tax of $1.01 per pack of cigarettes, or taxes by cities and counties, such as Chicago ($1.18), Cook County ($3.00), New York City ($1.50), Philadelphia ($2.00), and Juneau, AK ($3.00). Note the high tax rate in the northeast and far west, and the relatively low tax rate in the major tobacco-producing states (NC, KY, VA, SC, TN, and GA, highlighted in red).

Figure 1: Cigarette taxes and smoking rates, by US state by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.

Figure 1: Cigarette taxes and smoking rates, by US state by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.The trend line in Figure 1, which illustrates the relationship between cigarette taxes and smoking, suggests that higher taxes are, in fact, associated with less smoking. However, the data also suggest that high taxes have their limits. New York, for example, has the highest state tax on cigarettes ($4.35 per pack), but its adult smoking rate is still higher than the slightly lower-tax states such of Massachusetts ($3.51), Connecticut ($3.90), New Jersey ($2.70), and California ($2.87). The data also clearly indicates that the state tax rate is not the sole determinant of smoking. For example, Utah which has a relatively low tax rate also has a lower smoking rate, presumably due in part to Mormonism’s prohibition on smoking.

The adult smoking rate may not be the best indicator of the success of cigarette tax policy. Adult smokers are usually long-term smokers who are both more likely to be addicted and have more money, and so may be less discouraged by high cigarette taxes. Young smokers, however, are less likely to be addicted and have the financial means to support a smoking habit, so we would expect their demand for cigarettes to be more sensitive to taxes. Figure 2 plots the youth smoking rate on the horizontal axis and the level of cigarette state taxes on the vertical axis.

Figure 2: cigarette tax and youth smoking, by state by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.

Figure 2: cigarette tax and youth smoking, by state by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.Figure 2 bears out this assertion. The flatter trend line illustrates that higher state taxes lead to a greater decline in smoking among youth than among adults, and suggests that a number of states could lower their youth smoking rate even further by raising the excise tax.

Of course, state policy on cigarette taxes can be subverted by smuggling if the divergence between state taxes are substantial. Buying just one package of cigarettes in Virginia, where the tax is $0.30 per pack, and selling it in New York City, where the city and state tax combined are $6.01, would lead to a profit of $5.71. Since a pack of cigarettes is quite small and weighs only a few ounces, large scale smuggling presents a significant profit opportunity. One way of increasing cigarette taxes without encouraging additional smuggling would be to increase the $1.01 per pack federal tax on cigarettes.

Cigarette tax policy is far more complicated than the simple analysis presented here. There are many additional factors that may affect youth and adult smoking patterns, including race, gender, ethnicity, advertising, and legal age of smoking. And, since smoking is more common among the less affluent, cigarette taxes are likely to be regressive.

Despite these caveats, the evidence is clear that taxing cigarettes can save lives.

Featured image credit: cigarette smoking smoke ash by markusspiske. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The good tax appeared first on OUPblog.

Psychology’s silent crisis

Rarely do esoteric academic debates, especially those concerning methodology, make their way into the popular press. But, for the past two years, a major controversy on the replication of psychological research has spilled into public view and shows few signs of abating. However, the debate is silent about the far more problematic conceptual crisis that challenges the core principles of scientific psychology.

The controversy erupted with the publication of the Open Science Collaboration’s (OSC) findings that a mere 39 out of 100 experimental and correlational studies published in psychology’s most competitive and highly-vetted journals demonstrated consistent results when the same design and procedures were repeated. There are hundreds of journals publishing psychological research, with less stringent review processes, and it is likely that the percentage of replicable studies is actually much lower.

The most common way of interpreting these results is that scientific psychology needs to become more rigorous. Additional checks and balances should be institutionalized in order to insure the quality of published research. Nosek et al. argue that journals should require visibility, posting data, code, and research materials to public access archives as well as pre-registering analysis plans and valorize studies replicating previous findings.

Scientific psychology needs to become more rigorous.

Although these ideas should be embraced, they neglect a larger point. Even if psychologists manage to produce more replicable research, we will continue to misinterpret our data and to avoid the most fundamental and pressing problems of psychology. Indeed, psychology’s conceptual problem is much more profound and entrenched than the current controversy imagines.

Although psychology is fragmented into an eclectic mix of theoretical perspectives, there is a near universal acceptance that it emulates the natural sciences in its ambition to discover the timeless and universal laws about human beings. Psychology is held together by methodological unity based upon the reduction of observations into quantifiable variables that can be submitted to statistical analysis. Psychologists might disagree about the nature of human nature or the explanation for basic psychological phenomena, but there is little disagreement about what the appropriate scientific methods should be. For the majority of psychologists, psychology is not the study of persons or of psychological processes but the study of variables and how these variables relate to one another. This is what makes psychology a science.

Variable-centered research is a poor method for understanding persons or how psychological processes work.

There is nothing inherently problematic about reductive statistical analysis. In fact, such methods might be the most appropriate choice for studying certain questions such as the distribution of attitudes or beliefs in a particular population. But, beyond demographic facts, variable-centered research is a poor method for understanding persons or how psychological processes work. This is the crux of the problem.

It is a strange paradox that the mainstream’s method of choice can tell us nothing about the workings of thought processes, interpretations, or meaning making. Of course, psychologists often use their research findings to speak about how psychological processes function. But, such inferences represent a basic misinterpretation of our analyses. In both experimental and correlational research, observations are made on variables and we determine the statistical relationship between variables in the group. For example, perceptions of national groups as conscientious were correlated with observable demographic variables (such as walking speed and longevity) but not with aggregated self or peer reported scores of personality, a result which was replicated by the OSC. Persons primed with the belief that free will is an illusion were more likely to take advantage of a flawed computer program to answer difficult math questions; a result that was not replicated by the OSC. These are statistical relationships but they tell us nothing about how persons think or how these processes, now variables, relate on the human level. But, researchers talk about them as if they do. Interjecting insights from their life experience, researchers tell a story about what must be happening on the psychological level of analysis.

James Lamiell has called this misinterpretation of the data the “Thorndike maneuver,” in which statistical results observed between persons are used as evidence about what must be happening at the level of the person. We might know that two variables go together, the same person has or expresses them, but we don’t know anything about how or why they work together in the way that they do. We don’t understand the process that puts them into a dynamic relationship because we haven’t studied it. This basic error is endemic to the system and cannot be corrected with more complex models or the inclusion of mediating and moderating variables.

The soundness of our research to produce reliable results is obviously a major concern. However, we should be even more concerned that our methods faithfully direct us to the phenomena themselves and allow us to make trustworthy interpretations about what the data mean. In order to get beyond the replication crisis, psychology needs a deep reflection on how the discipline operates to produce knowledge. From my perspective, this must include welcoming innovative strategies for understanding persons and processes into the canon of psychological science. Psychology needs to recognize that, even if they are replicable, variable-centered methods are ineffective tools for getting to those problems most fundamental to our understanding of psychology.

Featured image credit: Brain, skull, science, anatomy and teaching by Jesse Orrico. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

The post Psychology’s silent crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

The origins of the juggernaut

People deploy the word juggernaut to describe anyone or anything that seems unstoppable, powerful, dominant. The Golden State Warriors, the recent National Basketball Association champions, are a juggernaut. National Economic Council director Gary Cohn is a “policymaking juggernaut.” Online retailer Amazon is also a juggernaut. Tennis player Roger Federer is a juggernaut at Wimbledon. In Marvel Comics there is a supervillain named Juggernaut that possess seemingly infinite strength and invincibility. The word, with its double hard g’s in the middle and the same final syllable as “astronaut,” is fun to say and connotes an individual bigger than our world. This makes sense because the word “juggernaut” is the product of the collision between two forces, an encounter between two worlds: the English-speaking West and India.

“Juggernaut” is the Anglicized name for the Hindu god Jagannath, the “Lord of the Universe.” Jagannath, a form of the god Vishnu, presides over a massive temple in Puri, India alongside his brother Balabhadra and sister Subhadra. The most famous ritual at the Puri temple is the Rath Yatra. During the Rath Yatra the wooden forms of the gods are ceremonially placed on large towering carts, or chariots, and pulled through the streets of Puri by devotees. “Juggernaut” entered the English language in the early nineteenth century as colonial Britons in India encountered Jagannath and his chariot and tried to make sense of what they were seeing.

Rev. Claudius Buchanan was the first British official to popularize “the Juggernaut” in both Britain and the United States in the early 1800s. Buchanan was an Anglican chaplain stationed in India and a staunch supporter of Christian missions to India. As might be expected from a missionary during the period, Buchanan’s took a negative view of Juggernaut. In his letters sent back home from India, Buchanan presented Juggernaut as a dangerous, violent, and bloody religious cult. These letters were reprinted throughout Christian missionary magazines on both sides of the Atlantic. Then, in 1811, Buchanan published Christian Researches in Asia, his broad examination of the religious state of India and its need, as he saw it, for Christian missions. In Christian Researches Buchanan described devotees throwing themselves under the wheels of Juggernaut’s chariots. He used a biblical reference to the Old Testament’s description of the heathen god Moloch (to whom people sacrificed their children) to explain Juggernaut to his Christian audience:

“The idol called Juggernaut has been considered as the Moloch of the present age; and he is justly so named, for the sacrifices offered up to him by self-devotement are not less criminal, perhaps not less numerous, than those recorded of the Moloch of Cannan.”

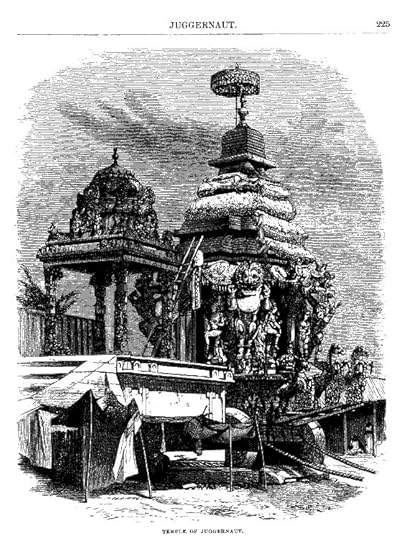

Engraving of Rath Yatra chariot from “Juggernaut,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, July 1878. Courtesy of Cornell University Library, Making of America Digital Collection. Used with permission.

Engraving of Rath Yatra chariot from “Juggernaut,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, July 1878. Courtesy of Cornell University Library, Making of America Digital Collection. Used with permission.Elsewhere in the book he claimed that Juggernaut “is said to smile when the libation of blood is made.” For Buchanan, Juggernaut represented everything that was wrong with religion in India that Christianity could solve. Juggernaut, to him, was a symbol of violence, bloodshed, death, and “idolatry.”

Buchanan’s description of Juggernaut became quite popular. Christian Researches in Asia was reprinted in numerous editions in America and Britain. The descriptions of Juggernaut were also excerpted in nearly every missionary magazine in the country. So, when the first American missionaries were sent to India from New England in 1812, it is no surprise that they sent back their own descriptions of Juggernaut to be published in America missionary magazines that continued to represent the god as violent and idolatrous. This image of Juggernaut was so well-known in Protestant missionary circles that one missionary magazine from 1813 even used Juggernaut as a metaphor for the vice of alcohol. Like Juggernaut, the article argued, alcohol has “shrines on the banks of almost every brook” and “four thousand self-devoted human victims, immolated every year upon its altars.” Thus, “juggernaut” started to become a term for any violent or dangerous force.

Over the next decades, as Americans learned more about India and Hindu religions, the meaning of “Juggernaut” began to split between its general use as a powerful dangerous force and its more specific reference to the Hindu god at Puri. For example, an article in Harper’s in 1878 titled “Juggernaut” quickly informed readers that “Juggernaut” was really named “Jagannath” and then proceeded to give the history of the temple at Puri. The article included a number of engravings depicting the floorplan of the temple, Jagannath’s chariot, and the forms of the god. Unlike the earlier missionary representations, the article in Harper’s sought to inform readers about the history of Jagannath and explain what devotees did and why they did it.

“Juggernaut” continued to be used as a reference to Jagannath, but its meaning was increasingly separated from any reference to the Hindu god. Use of the proper “Juggernaut” peaked in the early nineteenth century, while the use of the lowercase “juggernaut” slowly grew from the end of the nineteenth century to the present. By the 1930s, an anti-communist book labeled communism “the red juggernaut.” In 1963, The Juggernaut made his first appearance as a villain in Marvel’s X-Men comics. Juggernaut no longer had anything to do with the temple in India, but it still represented power, violence, death, and danger.

The two hundred year history of American use of “juggernaut” teaches an important lesson. From the beginning, “Juggernaut” and “Jagannath” were not the same thing. The process of Anglicization and translation that Buchanan and others engaged in meant that “Juggernaut” was a product of the British and American imagination. To say that Christian missionaries “misrepresented” or “misunderstood” Jagannath would be putting it too softly. They imagined Juggernaut as a foil, an Other, against which they could advocate for Christian missions. The missionary image of Juggernaut in the 1800s tells us more about the fears and values of Protestant missionaries than it does anything about people in India. As “Juggernaut” spread beyond missionary magazines and became the lower case “juggernaut,” the Christian missionary image of an “idol” on a chariot rolling through the Indian streets dropped away, but the sense of a giant, powerful, violent unstoppable force moving ahead endured. For two hundred years, juggernauts have rolled on in American imaginations.

Featured image credit: Medieval era abstract iconography of Jagannath on towels and clothing in India by Steve Browne & John Verkleir. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The origins of the juggernaut appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers