Oxford University Press's Blog, page 330

August 31, 2017

Fifth Rhythm Changes Conference 2017

On Thursday, 31 August, the Fifth Rhythm Changes Conference, themed “Re/Sounding Jazz” will kick off at the Conservatory of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Rhythm Changes conferences are the largest jazz research conferences in the field, bringing together some 150 researchers from all over the globe. This year’s edition is produced in collaboration with the Conservatory of Amsterdam, the University of Amsterdam, Birmingham City University, the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz, and CHIME.

Rhythm Changes started out as an interdisciplinary research project, funded by HERA (Humanities in the European Research Area), under its theme “Cultural Dynamics: Inheritance and Identity” (2010-2013). Rhythm Changes examined the inherited traditions and practices of European jazz cultures. Among the many outputs of the project were two conferences (Jazz and National Identities September 2011, and Rethinking Jazz Cultures, April 2013), which were so successful that once the funding stopped the Rhythm Changes team managed to continue them, on an 18-month schedule. The third Conference, Jazz Beyond Borders, was in Amsterdam again (September 2014), while conference four, Jazz Utopia was hosted by Birmingham City University (April 2016). Now we are back in Amsterdam for our first lustrum, with Re/Sounding Jazz. Rhythm Changes Six will take us to the oldest Jazz Research Institute in Europe, at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Graz, Austria, 11-14 April, 2019, 18 months from now.

There are many things to look forward to, such as excellent keynotes from Sherrie Tucker and Wolfram Knauer, a concert by vocalist and loop station specialist Sanne Huijbregts, the viewing of the documentary Sicily Jazz, a tribute to the complex history of New Orleans musician Nick LaRocca and the centennial of the 1917 recording by his Original Dixieland Jazz Band. There is also a workshop by Jazz and Everyday Aesthetics, and close to one hundred papers by leading jazz scholars, as well as by budding talent. The topics run from sonic histories in various regions to recording technique, from jazz festivals to reissues, from jazz and other genres to critical assessments of individual musicians, and many more. In addition, there is a pre-conference program with a presentation by the Europeana Collections project followed by a jazz archives round table. The best part of these conferences is that our delegates keep returning, and many have become friends. More often than not we left our day time venue with half of the attendants to continue our conversations in a restaurant or bar.

It was through our conferences that I realized that there is no single comprehensive scholarly overview of the fascinating history of a century of jazz reception in Europe The majority of the over seventy contributing authors of The Oxford History of Jazz in Europe I met in person at the Rhythm Changes conferences, and I look forward to meeting them again in the coming days.

Featured image credit: DSCF3009 by Claudio Pregnolato. Public Domain via Flickr .

The post Fifth Rhythm Changes Conference 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

August 30, 2017

Etymology gleanings for August 2017: “Getting on one’s wick” and other “nu-kelar” problems of etymology

Dark. I am sorry for the unavoidable pun, but the origin of most adjectives for “dark” is obscure. This is what etymological dictionaries of German tell us about dunkel and finster. Even when such an adjective has a known source and solid cognates outside Germanic, for instance, dim, the picture does not become clearer, for a list of related forms, all of which mean the same, fails “to illuminate the gloom, and convert into a dazzling brilliance that obscurity in which the earlier history” of such words appears to be involved, to quote the opening of the Pickwick Papers. In any case, the Old English form of dark was deorc. Its rather close synonym was dierne “hidden.” Assuming that both words ended in suffixes (deor-c and dier-n-e), they might belong together, and perhaps dark also originally meant “hidden,” “concealed,” or “invisible.” This dierne seems to hide in the modern verb darn, that is, “to stop holes” (and make them invisible) and tarnish. The latter is of French origin, but the Romance word, I assume, goes back to German tarnen “to hide,” known to some from the compound Tarnkappe “coat of invisibility.” Such a coat was used by Siegfried, the hero of The Lay of the Nibelungen (Das Nibelungenlied), and it often occurs in later folklore.

Numerals

I am always grateful for references to the sources I may not know, so thanks to John Cowan! Fortunately, I was aware of the hypothesis he referred to. And I agree that numerals tend to sound similar in many languages all over the world. Whether they indeed go back to the same proto-root is exactly what Nostratic linguistics tries to discover.

Spelling reform

Not long ago, Mr. Gogate sent letters on the Reform to many interested parties. I was one of them. First, he pointed out that in India millions of people speak English and that they might not or even would not agree to change the spelling of English words. Moreover, he pointed out, millions of websites will refuse to be respelled. Next he modified his view somewhat and cited a few words that people in India might perhaps not mind reforming. The third letter was the most combative. He said in it that the United States does not rule the world and cannot make the rest of English speakers change the spelling of the words they use. I hasten to pour oil on troubled waters. In about 150 years, the Reform has not achieved any results. In the unlikely event that the reformers will finally change the situation, they will have no power to coerce any country into accepting the new rules. Great Britain, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and of course India will adopt or not adopt the spelling that will “find favor” with one of the countries. I see nothing less attractive than politicizing the cause. But if politics must become a factor, let me say that many, indeed very many, people will bless their stars if someone musters up enough courage to do away with the glaring inconsistencies of English spelling.

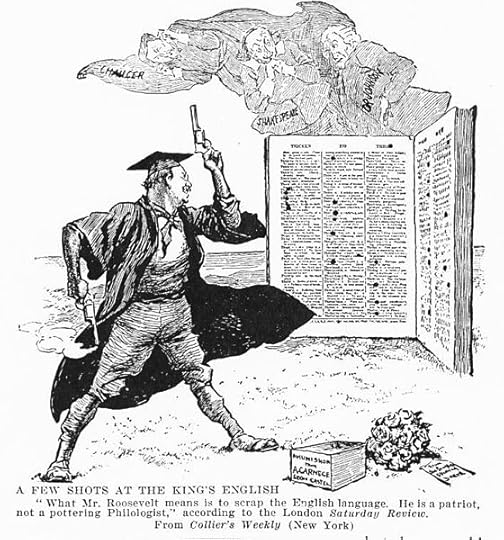

Theodore Roosevelt supporting simplified spelling.

Theodore Roosevelt supporting simplified spelling.Related forms and borrowings

I am returning to the relation of Engl. know to Greek gignóskein. If the modern view of language history is realistic, we should agree that the languages of the world form families. The largest language family is Indo-European. Both English (a language of the Germanic branch) and Greek (of course, not Germanic) belong to this family. Once again: if this picture is realistic, Greek and English are siblings. The nature of their parent has been the subject of speculation for centuries and need not bother us here. What matters is the fact that English and Greek are like two brothers or two sisters. Engl. know, from cnāwan, is akin to Greek (gi)gnóskein but not derived from it (they are siblings), while an English word like gnosis was borrowed from Greek wholesale, and that is why it has gn– at the beginning. A cognate, or congener, of Greek gnósis would have undergone the consonant shift and begun with kn-.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were brothers. Neither could be derived from the other. The same holds for English and Greek.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were brothers. Neither could be derived from the other. The same holds for English and Greek.The pronunciation of nuclear

This “issue” has been discussed ad nauseam. The variant nu-ke-lar has been adopted by millions, from the presidents of the United States to your next-door neighbor. In my opinion, the explanation given of this phenomenon is correct. There are many words like secular, particular, and muscular, and they influenced nuclear. Whether some prominent people mangle the word to sound folksy we will never know, but I doubt it. More important is the fact I keep rubbing in every time I deal with usage. In language, that is correct which is believed to be such by most speakers. Teachers, editors, and the cultured class may rage as much as they want. They are sure to lose the battle. Just as lay has ousted lie, so will nu-ke-lar eventually gain the day. Sorry for repeating my favorite aphorism (I love it because I coined it myself): it is most interesting to study the history of language but disgusting to be part of it.

Gleaning on my own field: to get on one’s wick

To get on one’s wick “to annoy, irritate” is slightly dated British slang. Urban Dictionary includes it, but I don’t know whether anyone uses the phrase in the New World. The origin of this idiom has been explained many times. Allegedly, wick means “penis” in slang because it rhymes with dick and prick. The other wick is an old word for “dwelling, hamlet, town,” as in Sedg(e)wick; –wich, as in Norwich, is its phonetic variant. For some reason, wick “penis” ruined the reputation only of Hampton Wick, now part of London, though Hampton is not the place famous for its Cockney population and humor. The baleful association resulted in Hampton also acquiring the same meaning.

Hampton Wick: a a model of respectability.

Hampton Wick: a a model of respectability.However, there is another way to approach the origin of the idiom. For years I have known not only the phrase it gets on my wick but also its German analog es geht mir auf den Wecker (literally, “it goes on my Wecker”). Wecker means “alarm clock,” something that wakes you up (wecken “to wake”). Obviously, in this form the idiom makes no sense. I assume that the near-identity of the English and the German phrases, with regard to both form and meaning, cannot be coincidental. In addition to Wecker, German has the noun Wecken (or simply Weck ~ Wecke), glossed as “loaf.” Pastries and loafs are often called for their form: compare Engl. roll. Weck must have designated a wedge-shaped loaf, for Weck is a cognate of Engl. wedge and Old Icelandic veggr. Here then comes my suggestion.

Perhaps Weck, which never had much currency outside some dialects, did indeed mean “penis.” Those curious for details are invited to look up penis wedge in Urban Dictionary, though the situation is different. It goes/ steps on my penis is not a very elegant but a sufficiently clear phrase for “annoy, irritate” (compare the modern genteel and disarming request don’t step on my tits). I believe that the German phrase was borrowed into English and that the English took German geht “goes” for get and changed Weck, which made no sense to them, to wick. The meaning and the reference to the endangered organ remained the same. From this phrase wick spread with the sense “penis.” All the rest is folk etymology and language game. Wick “penis” coincided with wick “town,” and Hampton Wick was chosen as the innocent victim of the homonymy. If I am right, rhyming slang has nothing to do with the story. After all, wick has always rhymed with dick and prick, so why did someone suddenly discover this fact? Most German speakers were also confused, because they did not understand what dialectal Weck meant and changed it to Wecker “alarm clock.” The result was incomprehensible gibberish, but who cares? Don’t English speakers pay through the nose (about which see the post for 13 October 2010) and do other odd things without stirring an eyebrow?

The post Etymology gleanings for August 2017: “Getting on one’s wick” and other “nu-kelar” problems of etymology appeared first on OUPblog.

Richardson / Laclos: A Mash-up of the Eighteenth-Century Novel

What if the two most notorious libertines of the eighteenth-century novel, Samuel Richardson’s Lovelace and Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Marquise de Merteuil, had met each other? Can their joint manipulations bring about victory for libertinism in the bourgeois novel? A mash-up of the eighteenth-century novel attempts an answer.

The novel Le Bâtard de Lovelace et la Fille Naturelle de la Marquise de Merteuil, published by Jean-Pierre Cuisin in 1806, proposes a thought experiment. Readers trace the intrigues and amorous adventures of the libertines through a series of letters in which they disclose their scandalous exploits to each other. The epistolary format is the same as in the two novels that have inspired Cuisin: Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa (1747-1748), in which the libertine aristocrat Lovelace challenges himself to seduce the virtuous bourgeoise Clarissa, and Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Dangerous Liaisons (1782), in which the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont engage in games of seduction that eventually lead Valmont to discover his own sentiment. Things go poorly for the libertines in Richardson and Laclos; both Lovelace and Valmont die in a duel, and the Marquise de Merteuil is socially disgraced.

Cuisin picks up on the structural similarities between Richardson’s and Laclos’ novels, in which Lovelace and Valmont discover the emotional intensity of sentimental love and their libertinism falters. Cuisin’s protagonist “Falselace”, however, shows no such weakness. He joins forces with the “Marquise de la Dolérie” in an attempt to lead libertinism to triumph. Can these libertines change the situational logic established by the novel in the eighteenth century?

The novel develops an intriguingly metafictional mash-up. “Falselace”, introduced as the bastard child of Lovelace, reveals that he has read Richardson’s novel and that he styles his own identity after this literary forebear. His status as the illegitimate offspring Richardson’s protagonist shifts between the literal and the figurative; Lovelace both does and does not exist in the letters of “Falselace”. Since “Falselace” has read the novels by Richardson and Laclos, he knows what fate awaits the libertine and sets out to profit from this literary knowledge in his own intrigues. His “ardent calling is to be the real and non-imaginary hero of Richardson, to acquire his celebrity and to usurp in one way or another his literary immortality” (II, 115; my translation).

“Falselace” survives the duel that is the consequence of his libertine exploits. Yet he cannot escape the situational logic of the eighteenth-century novel with its structures of poetic justice that have been integrated into the novel from the dramatic theory of neoclassical criticism. Richardson’s novels Pamela (1740) and Clarissa experimented with the basic principles of poetic justice in a number of ways, and it seems that Cuisin’s novel makes a new attempt in negotiating the role which this principle should play in the novel by giving his protagonist the knowledge to (potentially) defeat it.

In the end, as Cuisin’s choice of subtitle with Les Moeurs Vengées (“Morality Vindicated”) already gives away, the efforts of “Falselace” are doomed to fail. Tom Keymer suggests that it might be the shadow of the French Revolution that falls on “Falselace’s” aristocratic project here (2004, 213). Cuisin’s mash-up of two key eighteenth-century texts certainly underlines the degree to which poetic justice has been inscribed in the novel, and its reflection on this principle might be considered to point forward to later developments in the novel, as we find them for example in Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le Noir (1830).

Featured Image credit: Read anything good lately? by wackystuff. Some rights reserved via Flickr.

The post Richardson / Laclos: A Mash-up of the Eighteenth-Century Novel appeared first on OUPblog.

Microbiology in the city of arts and sciences

This year saw the biggest Federation of European Microbiological Societies (FEMS) Congress to date, with almost 2,700 delegates from 85 countries, including Australia, North America, and South Korea gathering in Valencia, Spain. Not only was it the biggest, it was also the most engaged; over 3,000 abstracts were submitted, over 220 delegates received FEMS Congress Grants to be able to attend, and nearly 250 speakers were invited to share their research and their passion for microbiology. Throughout the five days, 75 inspiring sessions and workshops took place, ranging from antimicrobial resistance to fermentation microbiology, from science education and communication to climate change…

FEMS Lwoff Award lecture

Every two years, FEMS awards either an individual or a group the FEMS-Lwoff Award. Named in honour of the first FEMS president, Professor André M. Lwoff, it represents an outstanding service to microbiology in Europe, and candidates are nominated by their peers. This year’s winner was Professor Jeff Errington, Director of the Centre for Bacterial Cell Biology at Newcastle University. His award-lecture took place as part of the Congress’ opening ceremony, focusing on cell wall deficient bacteria and their potential role in infectious diseases and in the environment.

Scientific publication explained

Another regular slot in the FEMS Congress programme is the scientific publishing workshop, chaired by Professor Jim Prosser, Board Member (Publications Manager) for the FEMS Journals. This year he was joined by Pathogens and Disease Editor-in-Chief Patrik Bavoil, and senior publisher from OUP, Matthew Pacey. Specifically aimed at early career microbiologists, the talk covered the publishing process from submission to online publication, top tips, and what not to do. Some that particularly resonated with the audience included:

“The science we do is only as good as the words we use to report it.”

“There is a reason why there is a ‘re’ in research: repeat, reproduce, reconsider, restart…”

“When rejected or asked to revise your manuscript, be humble, polite, and objective. Do not assume the reviewers or editors are: stupid, wrong, biased, competitors, or your enemies.”

“Speed is everything at the proofing stage. You will usually have about three days to respond to proofs!”

“Increasingly, the most successful researchers are those that self-promote.”

Key point from #FEMS2017: “The science we do is only as good as the words we use to report it.” I see examples of this every day. #scicomm https://t.co/ZP2qmGqhDI

— Kristina Campbell (@bykriscampbell) July 11, 2017

Antimicrobial resistance

With several symposia based on the topic of AMR, it was a key theme of the Congress. Elta Smith, research leader at RAND Europe, made a particular impression with her statistics in the workshop on ‘AMR Strategy – Future Challenges for Policymaking’: we’re facing the possibility of one death every three seconds by 2050 due to Antimicrobial Resistance. Roy Kishony’s talk was also provocative, as he used video to demonstrate how bacteria can adapt to survive and thrive when encountering increasingly strong antimicrobial agents.

Education – Engage your public

One of the more unique areas of the FEMS Congress was their stream of education-based symposia, workshops, and poster exhibitions, supported by the Professional Development section of FEMS Microbiology Letters. These focused on how best to communicate research to others, whether they are academic peers, students, or the general public, and focused not only on presentation and communication techniques, but also on the effect this could have on the future of microbiology in schools, universities, and in policy decisions. Brainchild of Joanna Verran, Education representative on the FEMS Board of Directors, the ‘Engage your public’ workshop covered a range of topics, ending with a guest presentation competition between eight early career scientists. FEMS Letters editor, Laura Bowater, gave guidelines on how to present research in an engaging, thought-provoking way, by asking a series of key questions:

Why does what you’re saying matter to the audience?

If you’re talking about a particular problem, what are the benefits of solving that problem?

How can you provide a simple message about a complex topic, without losing important information along the way?

James Redfern’s talk on how to introduce microbiology into various stages of education also asked questions of the audience, his innovative use of the interactive survey tool ‘Kahoot’ demonstrating how small changes can make a big difference in encouraging children, teenagers, and even adults, to engage more with science. This is particularly relevant for James’ work as a Guest Editor on an upcoming thematic series on ‘Mapping the Microbiology Community’ – soon to be published in FEMS Microbiology Letters.

40 years of microbiological milestones

My microbiology milestone was my first day in a research lab as an undergrad @umncbs in the lab of @bacteriality !!!! #FEMS2017 #LETTERS40 pic.twitter.com/i6ss5hPiw4

— Chelsey VanDrisse (@DearBacteria) July 11, 2017

The Letters lounge was one of the key areas in which to socialise and network at the Congress. Consistently full, lounge visitors could be seen discussing their science at tables, on sofas, or relaxing on beanbags. It was the perfect location for FEMS to highlight their community-based approach to publishing. Over the course of the five days, delegates added their own milestones to the 40-year timeline of highlights and facts. Contributions ranged from the date of first published papers and fun facts about past Editors-in-Chief, to when delegates first decided microbiology was the field for them.

This year’s FEMS Congress was an outstanding success, bringing together microbiologists from across a multitude of fields, encouraging discussion, learning, and co-operation. Already, we can look ahead to the 2019 Congress in Glasgow, and know that it promises to be even bigger and better!

Featured image credit: Feria Valencia. Used with Permission of Author.

The post Microbiology in the city of arts and sciences appeared first on OUPblog.

PTL and the history of American evangelicalism

Over the course of fourteen years, Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker built their local TV broadcast into an empire, making them two of the most recognizable televangelists in the United States. But their empire quickly fell when revelations of a sex scandal and massive financial mismanagement came to light.

In the following excerpt from PTL: The Rise and Fall of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Evangelical Empire author John Wigger demonstrates the relationship between the power of religion and American culture by tracing the rise and fall of the PTL.

On a crisp Carolina morning in January 1987, Jim Bakker stood before a crowd of supporters and prepared to break ground on the Crystal Palace Ministry Center. It was his biggest project to date as head of PTL, the television and theme park empire that he and his wife, Tammy Faye, had launched in 1974 in Charlotte, North Carolina. PTL was an acronym for Praise the Lord or People That Love. Critics rendered it Pass the Loot or Pay the Lady, an allusion to Tammy Faye, famous for her outrageous makeup. The date, 2 January, was no accident. It was Bakker’s birthday and the day he usually chose to launch major projects. Intended as a replica of London’s famed nineteenth- century Crystal Palace, Bakker’s version called for a glass structure 916 feet long and 420 feet wide. The complex would enclose 1.25 million square feet, including a 30,000- seat auditorium and a 5,000- seat television studio, at a cost of $100 million. It would be the largest church in the world.

At the time Bakker’s confidence did not strike many observers as entirely unwarranted. He had started PTL thirteen years earlier with half a dozen employees and some makeshift television equipment in a former furniture store. By 1986 PTL had grown into a worldwide ministry with 2,500 employees, revenues of $129 million a year, and a 2,300- acre theme park and ministry center called Heritage USA. During 1986 six million people visited Heritage USA, making it the third- most visited attraction in the United States, after Disneyland and Disney World. PTL’s satellite network included more than 1,300 cable systems and reached into fourteen million homes in the United States. The ministry’s programs were seen in as many as forty nations around the world, making Bakker an international celebrity and opening up enormous fundraising potential.

When Bakker broke ground on the Crystal Palace center, Heritage USA already had a five- hundred- room hotel, the Heritage Grand Hotel, with another five- hundred- room hotel, the Heritage Grand Towers, nearing completion alongside it. The complex had one of the largest waterparks in America, a state-of-the-art television studio, half a dozen restaurants, a miniature railroad to shuttle visitors around the park, an enclosed shopping mall attached to the Heritage Grand, a petting zoo, horseback riding trails, paddleboats, tennis courts, miniature golf, a home for unwed mothers, a home for disabled children known as Kevin’s House, and several condominium and housing developments. Plans called for adding a thirty-one story glass condominium tower to the Crystal Palace complex, an eighteen- hole golf course lined by $1 billion in condominiums, a village called Old Jerusalem with its own two- hundred- room hotel, and a variety of other lodging, including bunkhouses, country mansions, and campgrounds. Heritage USA was as much an all-inclusive community as it was a theme park. Bakker hoped that it would eventually have thirty thousand full-time residents. He assured his audience that the best was yet to come.

PTL and the Bakkers became a national symbol of the excesses of the 1980s and the greed of televangelists in particular.

Two and a half months later, on 19 March 1987, Jim Bakker resigned in disgrace from PTL after his December 1980 sexual encounter with Jessica Hahn in a Florida hotel room became public. Hahn described Bakker forcing himself on her in an article in Playboy, while he claimed that she was a professional who knew “all the tricks of the trade.” In the wake of the Hahn revelation, stories appeared about Bakker’s involvement in gay relationships and visits to prostitutes, sometimes wearing a blond wig as a disguise. A decade later, in 1996, Bakker revealed that he had been sexually abused from age eleven until he was in high school by an adult man from his church, leaving him with a confused sexual identity and a deep sense of guilt and inferiority. The memories became “ghosts” that “swarmed through my thoughts” at vulnerable moments.

The 1987 scandal was initially about sex, but it soon turned to money after it was discovered that PTL had paid Hahn and her representatives $265,000 in hush money. When he resigned, Bakker turned the ministry over to fundamentalist preacher Jerry Falwell. He and his team quickly discovered that PTL was $65 million in debt and bleeding money at a rate of $2 million a month. That summer workers boarded up the unfinished Towers Hotel, which never opened. Falwell and his entire staff left PTL in October 1987, less than seven months after he took charge of the ministry. When he took over, Falwell praised PTL as “one of the major miracle ministries of this century. I doubt there’s ever been anything like it in the 2,000 year history of the church.” When he left he declared that Bakker had turned PTL into a “scab and cancer on the face of Christianity,” a disaster unparalleled in the last 2,000 years.

Two years later, in 1989, Bakker went on trial for wire and mail fraud, accused of overselling “lifetime partnerships” to Heritage USA and misusing the money donated for its construction. The trial unfolded in a circus- like atmosphere before US District Judge Robert “Maximum Bob” Potter. A witness collapsed on the stand and Bakker himself had a psychological breakdown, crawling under his lawyer’s couch as federal marshals came to get him. He was convicted and initially sentenced to forty-five years in prison, serving nearly five years before his release. For millions who watched the scandal unfold in the press and on television, PTL and the Bakkers became a national symbol of the excesses of the 1980s and the greed of televangelists in particular.

In both its rise and fall, PTL demonstrates the power of religion to connect with American culture. The creation of PTL and Heritage USA followed a well-established trajectory in American evangelicalism as it evolved from field preaching, to camp meetings, to big tent revivals, to radio and television.

Featured image credit: sky christ blue jesus by AleBricio. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post PTL and the history of American evangelicalism appeared first on OUPblog.

August 29, 2017

America’s forgotten war

You probably don’t know it, but we are now in the centennial year of United States entry into World War One. On 2 April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress to ask for a declaration of war against Germany. Wilson had narrowly won re-election the year before by campaigning under the slogan “he kept us out of the war.” But by the following spring, and following the resumption of Germany’s unrestricted submarine campaign against North Atlantic shipping, Wilson felt he had little choice but to join the conflict that had, for two and a half years, wrought unprecedented carnage to Europe. In announcing his intent to take the US into the war with “no selfish ends to serve,” and “no feeling towards [the German people] but one of sympathy and friendship,” he framed the basic U.S. war aim as simple and magnanimous: “the world must be made safe for democracy.” With this, Wilson set a course for a U.S. foreign policy of liberal interventionism with a global range that continues to this day. Washington was transformed from a sleepy administrative town to being the center of a complex and immensely powerful corporate and federal collaboration, the precursor to what Eisenhower would call the Cold War “military-industrial complex.” As the U.S. government drafted four million men, curtailed civil liberties and rigorously suppressed dissent, nationalized the railways, and ran a huge propaganda bureau, the relationship between ordinary Americans and their federal government was drastically changed, in many ways for good. 53,000 Americans died in battle, another 63,000 died of non-combat injuries or disease, and over 200,000 servicemen returned with a permanent disability. The racist and xenophobic energies unleashed by the war fed directly into the drastic immigration restrictions of the 1920s; the federal state it bequeathed served, in many ways, as the blueprint for the New Deal and the modern American welfare state. Yet there is a curious indifference to the legacy of this war in the U.S.

Even the website of the United States World War One Centennial Commission calls it “America’s forgotten war.” There is no national memorial to World War One on the national mall. The highest-ranking government official to attend the official commemoration of U.S. entry to WWI at the National World War One Memorial in Kansas City was not Donald Trump, or even James Mattis, but Secretary of the Army Robert M. Speer. Things are very different in the rest of the Anglophone world; in the United Kingdom, schoolchildren find it hard to avoid studying the so-called “trench poets” of WWI, who also happen to be the favorite verse of prime ministers. The installation “Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red,” which transformed the Tower of London with nearly 900,000 ceramic poppies planted in the moat, was visited by an estimated five million people. In Canada and Australia, the battle of Vimy Ridge and the Gallipoli campaign, respectively, continue to be widely-memorialized events with central places in their stories of national formation.

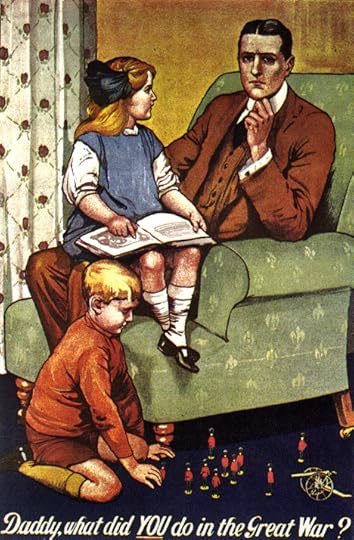

“Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?”, by Savile Lumley. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?”, by Savile Lumley. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.So, why is there this gap between the war’s significance to U.S. history and the place it has in the national memory and commemorative landscape? Scholars in the past ten years have thought extensively about that question. For some, the mixed legacy of the war—the problem Americans had in settling on one consensus narrative of its effects and significance—caused it to fade from memory. For others, it was because America’s memorial construction—of extensive military cemeteries and monuments—often happened in France, far from the eyes of successive generations of Americans. And this despite WWI-era America instigating memorial practices such as the repatriation of bodies, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and the Gold Star Mothers that remain significant today. For Historian Michael Kazin, in contrast to other national literatures, American war literature was simply not good enough to help sustain the war in American memory; most of the poetry produced about it was ‘doggerel,’ and only one war novel—Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms—is still widely read.

Yet perhaps one way to reconnect with the war’s legacy to the U.S. is just to look closer at the American literature we do still read from the period. War veterans populate novels such as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930), Willa Cather’s The Professor’s House (1925), and Nella Larsen’s Passing (1929). Some of e.e. cummings’ most brutally satirical political poems are about WWI. Many of the preoccupations of 1920s literature—from heartbreaking flappers to horrendous car crashes, or the urbane confidence of the Harlem Renaissance—have deep roots in trench combat and in the social and technological transformations of American war mobilization. Scratch the surface, then, and the literature of one of the great decades of American literary production—the 1920s—is saturated with reflections on the war. And perhaps a bit of such digging would be no bad thing, as the questions these authors and others considered—How does one write the truth about war, or register its horrific violence in ways noncombatants can understand? What is the value of military service to civil society? At what point do the necessary disciplines of fighting a war fatally damage the liberties one is fighting for in the first place? And how do we craft ways of remembering that are capable of including all the people who sacrificed and served?—have an undiminished relevance. Sometimes the U.S. authors who wrote about WWI had answers to these questions; sometimes not, but their struggles to address them remain, in many ways, our own.

Featured image credit: ww1-trench-warfare-one-war-world by bmewett. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post America’s forgotten war appeared first on OUPblog.

What causes psychogenic amnesia?

The media love it. Films and novels fictionalise it. TV and newspapers want to follow a real patient around. They virtually always get it wrong (and the worst thing you can do for such a patient is put him/her on television). Psychogenic amnesia (also known as dissociative or functional amnesia) still intrigues and fascinates.

In 1926, Agatha Christie, the acclaimed novelist, disappeared for 11 days. Her home was in Berkshire; her car was found in Surrey; and she was discovered 11 days later in a hotel in Harrogate. She claimed amnesia for what had happened. The authenticity of her amnesia has been disputed, but the circumstances were typical of those that characterise a ‘fugue state’.

Many cases of psychogenic amnesia appear to migrate to central London, where they are often picked up by the police in central London parks or railway termini, and taken to St Thomas’s Hospital in its location opposite the Houses of Parliament. Harrison et al. (2017) have now reported 53 cases seen by Prof Kopelman and his team over the course of 20 years on a psychiatric receiving ward. This is by far the largest series of such patients to be described in recent times.

We found that there were four sub-groups of such patients. The first sub-group consisted of patients who, following a precipitating crisis, disappeared (rather like Agatha Christie) with loss of their sense of identity and memory, and travelled what were sometimes long distances. These patients are described as having a ‘fugue episode’, an expression derived from the Latin word ‘fuga’, meaning ‘flight’. These patients characteristically get better, either spontaneously or with therapeutic help – often within a few hours or days (we drew a cut-off point at four weeks).

Newspaper article about Archibald Christie and his wife Agatha Christie at Harrogate by Daily Herald (London) 15 December 1926, p. 1. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Newspaper article about Archibald Christie and his wife Agatha Christie at Harrogate by Daily Herald (London) 15 December 1926, p. 1. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.A second group started out like the Fugue group (forgetting who they were, and sometimes travelling distances); although these patients rapidly ‘re-learned’ who they were, their amnesia persisted, much longer than four weeks. We have labelled this sub-group Fugue-to-Focal Retrograde Amnesia (F_FRA).

A third sub-group did not begin with a fugue-like episode, but had often suffered a very mild head trauma or neurological event just before their memory loss, which could not possibly account for their onset of Focal Retrograde Amnesia (FRA).

A final subgroup simply reported ‘gaps’ in their memories, which related, directly or indirectly, to stressful life events.

With regard to features of the amnesia, a person’s knowledge of who he/she was (personal identity) was lost only in the psychogenic cases, particularly the Fugue cases. The failure to recognise the family was most common in the psychogenic cases, particularly the two FRA subgroups, but occasionally happened in neurological cases. Interestingly, a history of past or precipitating head injury was actually more common in the psychogenic cases (just over 40%) than the neurological cases (10%). Factors like past or precipitating depression, relationship or family problems, financial or employment problems, occurred in all the groups, but were much more common in the psychogenic than the neurological cases or healthy participants.

With regard to performance on neuropsychological tests, we found that, during their amnesia, the psychogenic patients were mildly impaired on tests of new learning, particularly on word recall tests, compared with their scores three to six months later. However, their most devastating deficit was in remembering past facts about their lives or in recalling events they had experienced. The Fugue group performed particularly badly in trying to recall facts or events from any time period in their lives. The two FRA groups did badly on facts or events from childhood or their young adult life, but somewhat better for more recent events – this is the opposite pattern to neurological patients, who characteristically show relative sparing in remembering early memories, but do very badly on recent memories. However, after three to six months, the Fugue group had improved to normal in remembering facts about their past, and near-normal in remembering events from their past. The two FRA groups had also improved, but not so much as the Fugue group; and they still did better on recent memories, compared with earlier ones.

Taking all this together, it shows that the outcome in such cases is much better than generally assumed – at least if the cases are caught at an early stage in their disorder. The Fugue cases often recovered ‘spontaneously’ with very little or no specific treatment. The FRA cases had had a variety of treatments, including antidepressant medication. The pattern of results suggests that memory retrieval had been inhibited during the amnesia, perhaps because the patients had somehow been avoiding (consciously or subconsciously) thinking about stressful or traumatic events, and this in turn can induce forgetting, as recent experimental work has shown. The findings are also consistent with a ‘model’ in which a stressful life event or events at a time when a person is depressed (and sometimes suicidal) can trigger psychogenic amnesia, even if the person cannot then pinpoint what these stressors were. This psychogenic memory loss seems to happen more commonly in people who, for whatever reason, have had a past, brief episode of transient memory loss for a neurological reason, such as a very minor head injury. This latter factor may be the reason why these patients developed amnesia at a time of severe stress as opposed to some other psychogenic/functional disorder, such as non-epileptic seizures, psychogenic blindness, or various motor or sensory symptoms.

This remains a fascinating topic, but not necessarily in the way that the media envisage.

Featured image credit: ‘Memory’ by jarmoluk. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What causes psychogenic amnesia? appeared first on OUPblog.

States of affairs: the prominence of the 50 state governments during the Trump presidency

Now that we have passed the 200-day mark of Donald Trump’s presidency and can take stock of elements of change and continuity in US policy-making in the new administration, it is important not to lose sight of the continued importance of state governments. Although developments in Washington, DC naturally attract significant attention, the fifty states continue to play a prominent and under-appreciated role in various policy areas. At the least, as scholars have shown, a full account of policy-making during the Trump administration, no less than in prior administrations, has to take account of the actions of state officials in adopting policies, challenging federal policies, and negotiating with federal officials about implementing policies.

State governments have long been policy pioneers in the US federal system, taking the lead in adopting measures that are in many cases later enacted at the national level. But state policy activism has accelerated in the 21st century in response to partisan polarization and gridlock at the national level. Democrats and Republicans are at relatively even strength in Washington. Even when one party holds the presidency and both houses of Congress, as Republicans currently do, the margins are generally narrow, with the minority party almost always holding enough seats in the senate (at least 41 out of 100) to mount a filibuster, thereby making it extraordinarily difficult to enact major legislation.

In most states, though, the executive and legislature are controlled by the same party, which in a number of cases holds a super-majority of legislative seats. Thirty-one states are currently characterized by unified party control of the executive and legislature — 25 are Republican dominated states and 6 are Democratic-dominated states. On issues where Congress fails to act, states often fill the policy vacuum whether boosting the minimum wage, legalizing marijuana, scaling back protection for labor unions, tightening restrictions on (or facilitating access to) guns, or adding (or relaxing) restrictions on abortion. Even when these and other policies are blocked in state legislatures, the availability of direct democratic institutions in half of the states makes it possible to achieve policy changes by putting them to a popular vote. Additionally, local governments have been active in enacting policies blocked at the federal and state level, such as increasing the minimum wage, even if state governments are increasingly pushing back by passing laws preempting local policy innovation.

State officials also continue to challenge federal policies, especially policies promulgated via executive orders or agency regulations, often by going to court. During the Obama presidency, Republican state attorney generals, most notably in Texas but also in other states, filed lawsuits challenging executive actions regarding immigration, environmental protection, and LGBT rights. In several high-profile cases, federal courts sided with state officials and issued rulings blocking enforcement of Obama administration policies, including the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan and the president’s Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA).

It is important not to lose sight of the continued importance of state governments.

State lawsuits have continued into the Trump presidency, albeit with Democratic attorney generals now taking the lead in challenging federal executive and regulatory actions regarding education, environmental protection and immigration. This was on prominent display in the aftermath of the president’s executive order suspending admission of refugees and banning entry to the country from residents of various Middle Eastern countries. Although the US Supreme Court in June 2017 allowed a modified version of the president’s executive order to take effect, lower federal courts enjoined enforcement of the order for several months in response to lawsuits filed by the attorneys general of Washington, Minnesota and Hawaii.

State officials’ negotiations with federal officials about implementing federal policies attract less attention than state-filed lawsuits; but sometimes they are just as important in enabling states to chart their own path. Consider the role of states in implementing the Obama administration’s signature domestic policy, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which among other things calls for states to expand the range of low-income persons receiving health coverage through the joint federal-state Medicaid program. Nineteen states have chosen not to participate in the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. Meanwhile, twenty-five states opted to expand Medicaid in the way set out in the ACA. But another half-dozen states engaged in extensive negotiations with Obama administration officials and secured waivers allowing them to expand Medicaid on their own terms, occasionally relying on innovative approaches not envisioned in federal law. These state-federal negotiations have continued during the Trump presidency, as state officials have sought and occasionally gained additional leeway in operating Medicaid programs and implementing other ACA requirements.

One lesson to be drawn from policymaking during the early part of the Trump presidency is that for all the attention understandably paid to actions taken by the president, Congress, and Supreme Court, and the ways Trump administration policies differ from Obama administration policies, state governments continue to play a prominent role, in the current administration no less than in prior years, in crafting, challenging, and shaping implementation of key policies.

Featured image credit: capitol building California by sarangib. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post States of affairs: the prominence of the 50 state governments during the Trump presidency appeared first on OUPblog.

Mahler our contemporary

With various commemorations of the birthday of Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) in July, the attention to this composer reinforces his continuing significance for modern audiences. Literary scholars have made cases for the ways in which Shakespeare’s works retain their relevance for modern audiences in such different works as Jan Kott’s Shakespeare Our Contemporary (1960) and Marjorie Garber’s Shakespeare and Modern Culture (2009). Without going into the details involved with Shakespeare, a similar case can be made for Mahler’s music not only retaining its status for modern audiences but also having the potential to continue its appeal. With a composer like Mahler, the attraction to his music is no accident.

Research on Mahler offers some points of reference that reflect his continuing appeal. A recurring theme in Mahler studies is the idea of autobiographical implications in the extramusical ideas that Mahler explored. The lovelorn narrative of the song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (1885) draws on poems from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, and as much as Mahler’s selections from those poems reflect personal choices, the fact that he wrote some of the verses brings the text closer to him. The anguish of spurned love and the desperation the lover feels comes through immediately in these vivid songs. When it comes to the anonymous narrator, is it Mahler himself or some version of himself that Mahler embodied in the music?

The fact that such questions are impossible to answer in any absolute sense contributes to the appeal of the music, which sometimes allows the narrator to merge with the listener. This is hardly unique to Mahler, but the appeal of this particular work intensifies when audiences hear it quoted in the opening and penultimate movements of his First Symphony (1888). The main theme of the first movement suggests a sense of energy through the intervals and rhythms, but the idea takes on additional meanings when listeners connect it to the second song of Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, “Ging heut’ morgen über’s Feld” (This morning I went into the field”) The self-quotation is part of other intertextual elements that add to the experience of the music. As much as listeners can focus on the development of the ideas within the Symphony itself, the connotations from the text of the song cycle contribute additional levels of meaning that suggest some programmatic ideas, and it is not difficult to read into the reference as the work shifts from struggle to triumph as the music progresses to the exuberant Finale of the First Symphony.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony no. 4, preliminary sketch page “6” for movement 1, Chicago, IL: The Newberry Library. Case MS VM 1001 M21 S4 pg.2. Used with permission.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony no. 4, preliminary sketch page “6” for movement 1, Chicago, IL: The Newberry Library. Case MS VM 1001 M21 S4 pg.2. Used with permission.That stated, the shifting roles of programs with Mahler’s music also have an appeal for audiences. The work that modern audiences know as his Symphony no. 1 was known in some of its early performances as “Tone Poem,” a title that implicitly suggests a program connected to the musical structure. While Mahler once sanctioned written program to accompany performances of the First Symphony, he eventually withdrew it, along with the programs for other works, including the Second Symphony. Mahler famously disavowed programs for his music: “Let every program perish.” Despite Mahler’s wishes, modern audiences often encounter some version of the narrative he once gave the First Symphony in program notes. In some ways this suggests a level of intellectual involvement on the part of the listeners who remind those unfamiliar with the work that those levels of meaning were part of the experience.

With or without a program, the music does not change and, in this sense, it does not lose its appeal. It is similar with his later works, which often did not have programs at their original performances and which can still suggest something more than the innovative structure he gave his works. His strategies are at times ingenious.

The Fourth Symphony (1901) culminates in a Song-Finale “Das himmlische Leben” (“Heavenly Life,” 1892) that quotes in part the choral movement of the Third Symphony (1896), the song “Es sungen drei Engel” (“Three angels were singing,” 1895), a piece that Mahler actually composed several years after he finished the other one. Beyond the interplay with the Third Symphony, Mahler used thematic ideas from “Das himmlische Leben” in all three of the movements that precede it in the Fourth Symphony. Here the fragments are sometimes so brief that they suggest the kind of motivic exploration found with Beethoven and the atomization sometimes associated with serial composers.

While modern audiences are sufficiently familiar with Mahler’s music to hear thematic ideas from the song in the first, second, and third movements, the audiences of Mahler’s day might not have benefited from such knowledge of his music. Yet that did not make the quotations unintelligible. Rather, they point to the ways in which such thematic fragments make the music seem familiar. Just as in literature, the idea of defamiliarization is a means to impart ideas organically in a work, Mahler’s musical deployment of this technique makes it possible to grasp the ideas. The short ideas eventually emerge in more extended ones, and he supports his strategy with a remarkably shifting orchestration that adds yet another level of appeal to the music.

Such appeal is hard to dismiss, with scorings that make use of chamber-music textures and sonorities that stand in stark contrast to the large forces on stage for his works. The timbres involve as rich a palette as the colorful scorings Schoenberg would explore in his Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 16 (1909) or some of Alban Berg’s early works. Anton Webern’s early tone poem Im Sommerwind is redolent of timbres that anticipate the innovations other twentieth-century composers would exploit in the decades after Mahler’s death. Yet Mahler stands at the center of these innovations, a composer who found ways to create very personal works that have an aural appeal through their connections with other music and also the craft the composer used in shaping them. At the anniversary of his birth, it’s useful not just to acknowledge his place in history but also to explore the ways his music makes Mahler our contemporary.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Classical Music, Concert’ by Pexels, CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay.

The post Mahler our contemporary appeared first on OUPblog.

Supreme Court of Canada challenges the idea of state sovereignty

It has been a busy time for the Supreme Court of Canada. In a judgment on 23 June 2017, it ruled that Facebook Inc’s forum selection clause was unenforceable in a case involving the application of British Columbia’s Privacy Act. The long-term value of that judgment is, however, questionable given that the Court was split 4-3, with one of the judges (Abella J.) deciding against Facebook, doing so on a different basis to the other three who ruled against Facebook.

The more important decision was handed down on 28 June 2017 in the long-running dispute between Google Inc. and Equustek Solutions Inc., and it is not good news for anyone apart from for Equustek Solutions Inc.

The case has gained a considerable degree of international attention and the background to the dispute is generally well-known. The issue in the appeal was whether Google could be ordered (via an interlocutory injunction) to de-index (with global effect!) the websites of a company (Datalink Technology Gateways Inc., and Datalink Technologies Gateways LLC) which, in breach of several court orders, sell the intellectual property of another company (Equustek Solutions Inc.) via those websites.

“Officer Freelancer” by FirmBee. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Officer Freelancer” by FirmBee. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.The majority of the Court ruled in favour of Equustek concluding that:

[S]ince the interlocutory injunction is the only effective way to mitigate the harm to Equustek pending the resolution of the underlying litigation, the only way, in fact, to preserve Equustek itself pending the resolution of the underlying litigation, and since any countervailing harm to Google is minimal to non-existent, the interlocutory injunction should be upheld. (para. 53)

This conclusion was reached via a belaboured journey through the quagmire of both legal and technical misunderstandings and half-truths. Most of those misunderstandings and half-truths are highlighted with commendable clarity in the dissenting judgment by Côté and Rowe JJ. who also stressed that:

In our view, granting the Google Order requires changes to settled practice that are not warranted in this case: neither the test for an interlocutory nor a permanent injunction has been met; court supervision is required; the order has not been shown to be effective; and alternative remedies are available. (para. 60)

The majority judgment represents a missed opportunity to take the law in a direction recognising the special features of the Internet, to take a step away from the present ‘hyper-regulation’ of Internet content, to recognise the role of geo-location technologies and to properly address ‘scope of jurisdiction’ issues.

However, what is worse, it sets a dangerous precedent that a court of any state may order Google to de-index with global effect, without any real effort to consider the effects this has in other countries or for the development of law in relation to the online environment. I would be most surprised if the hazardous step now taken by the Supreme Court of Canada does not result in a sharp increase in speculative actions directed at Internet intermediaries such as Google.

“Earth and Internet” by HypnoArt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Earth and Internet” by HypnoArt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Moreover, questions must be raised regarding how the majority approached the sovereignty of affected foreign states:

Google’s argument that a global injunction violates international comity because it is possible that the order could not have been obtained in a foreign jurisdiction, or that to comply with it would result in Google violating the laws of that jurisdiction is, with respect, theoretical. […] And while it is always important to pay respectful attention to freedom of expression concerns, particularly when dealing with the core values of another country, I do not see freedom of expression issues being engaged in any way that tips the balance of convenience towards Google in this case. (paras 44-45)

It is interesting to compare this nonchalant attitude to the ongoing discussion of when law enforcement agencies in one state may seek access to data held in another state. In the latter setting one often hears objections raised that such an access to data amounts to an unlawful interference with the sovereignty of the state where the data happens to be located. However, in the Equustek case, the Supreme Court of Canada made an order requiring an alteration to the data held in another country. It seems beyond intelligent dispute that this is much more invasive than is mere access to data.

I am not here seeking to advocate what approach to sovereignty is more appropriate, but one thing is sure; we cannot have it both ways.

Featured image credit : “Canadian Flag” by ElasticComputeFarm. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Supreme Court of Canada challenges the idea of state sovereignty appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers