Oxford University Press's Blog, page 328

September 8, 2017

How long should children fast for clear fluids before general anaesthesia?

Anyone who has had a general anaesthetic will be well aware of the need to fast beforehand. ‘Nil by mouth’ (NBM) or ‘NPO’ (nil per os, os being the Latin for mouth) instructions are part of everyday life on pre-operative wards.

This withholding of food and liquids before a general anaesthetic is necessary is because of the risk of the full stomach emptying all or parts of its contents into the patient’s lungs. Once general anaesthesia is induced, the protective reflexes that would normally cause us to cough and splutter in the event of the stomach emptying in the wrong direction are lost along with most other reflexes.

Solid material poses the biggest threat since it can mechanically obstruct the airway. Indeed, this was recognised as early as 1946 by Curtis Mendelson when he described an aspiration syndrome and several fatalities in pregnant patients under general anaesthesia.

However, what is often forgotten about this ground-breaking work is that whilst solid aspiration was indeed a significant issue, aspiration of liquid contents did not result in any long term issues or fatalities even in an era of very different levels of postoperative care that we enjoy today. This led to historical fasting guidelines which have remained fairly universally followed ever since, in that solids should be avoided for at least six hours before general anaesthesia and liquids for two hours.

In practice, however, these rules translate into much longer fasting times due to the unpredictability of the operation day and patients’ understandable anxiety not to fall foul of any rules that may lead to delay or cancellation. Most studies in paediatrics adhering to a two hour clear fluid fasting policy result in an average fasting time of more than six hours.

This is an unnecessarily long time on an already stressful day for parents and patients alike. This is particularly true for young patients who do not understand why they cannot have a drink. Parents, who themselves may well be anxious about the impending procedure, have the added stress of keeping their child fasted beyond what they are used to and having to deny their repeated pleas for a drink.

Doctor and patient in children’s hospital. CCO public domain via Pixabay.

Doctor and patient in children’s hospital. CCO public domain via Pixabay.Recently these rules have been challenged, demonstrating that a more liberal policy of allowing drink up to the time of being called to the operating theatre does not result in any greater incidence of aspiration than more conservative rules in more than 10,000 patients.

Several UK paediatric centres are now recognising the suffering and adverse physiological effects (such as greater drops in blood pressure at the start of anaesthesia) that prolonged fasting can cause. Many have moved to a one hour clear fluid fasting policy that allows for a drink on arrival at the admission unit in most cases. There is, naturally enough, anxiety amongst many anaesthetists that a more liberal regime may result in a higher rate of aspirations that may in turn lead to respiratory complications but the available literature does not support this view.

Of course aspiration rates continue to be monitored and dealt with promptly and effectively if and when they occur, as they always have been. Anaesthetists are risk-averse by nature and are understandably conservative about challenging dogma but we all recognise that, especially in young children, we need to be more patient-focussed in this regard.

Featured image credit: Rubber duck by Photographer2015. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post How long should children fast for clear fluids before general anaesthesia? appeared first on OUPblog.

Top tips for a healthy heart

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the most common cause of death in the United Kingdom, and is also a major killer worldwide. CHD is caused by fatty deposits building up in a person’s coronary arteries and can lead to symptoms including heart attacks, angina, and heart failure. The chances are that you’re already aware of many of the key contributing lifestyle factors which cause people to develop CHD, such as smoking, high salt intake, and consuming foods high in saturated fats.

At this year’s European Society of Cardiology Congress in Barcelona we took the opportunity to ask cardiologists for other top tips they recommend for a healthy heart. The results were much more holistic than we anticipated and we have compiled some of our favourites below:

“Get lots of sleep!”

“Sleep well, eat well, exercise regularly, spend more time with the family and enjoy life. We have only one life, don’t waste it with [the] little things.”

“Education to children [is] the most important [thing] to be healthy in adulthood”

“A heart with training is a heart with living”

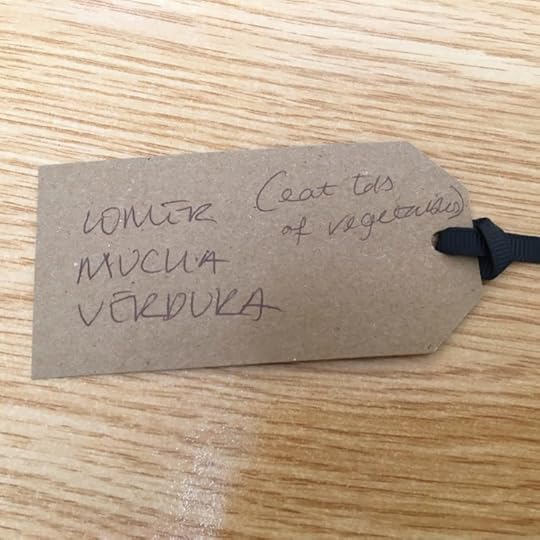

“Eat lots of vegetables”

Other entries also spoke of the benefits of de-stressing, and offered advice on how to help with this such as including undertaking low intensity exercise such as yoga, and getting regular exercise and fresh air.

Featured image credit: Human Body Organs (Heart).3D by Life science. © via Shutterstock.

The post Top tips for a healthy heart appeared first on OUPblog.

September 7, 2017

How well do you know the history of physics?

Less than four centuries separate the end of the Renaissance and the theories of Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton from the development of quantum physics at the turn of the 20th century. During this transformative time, royal academies of science, instrument-making workshops, and live science demonstrations exploded across the continent as learned and lay people alike absorbed the spectacles of newfound technologies, devices, and innovations. Energy consumption, medicine, transportation, engineering, the study of the universe, and the ways in which countries conducted war all drastically changed as the field of physics grew over the years.

From Copernicus to Einstein, how well do you know the history of physics? We’ve created this quiz to test your knowledge of physics since the height of the Scientific Revolution.

Featured Image credit: 1927 Solvay Conference, Benjamin Couprie, Institut International de Physique Solvay, Brussels, Belgium. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

Quiz background image: statue at Eureka! Zientzia Museoa, San Sebastián. Zarateman. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post How well do you know the history of physics? appeared first on OUPblog.

A photographer at work: Martin Parr behind the scenes

Martin Parr is one of Britain’s best-known contemporary photographers, with a broad international following, and is the President of Magnum, the world-famous photo agency. His social documentary style of photography turns a wry and sometimes satirical lens on British life and social rituals, lightened by humour and affection. Between 2013 and 2016, Parr turned his lens to the University of Oxford, capturing the day-to-day life of students and staff at work and play throughout the academic year.

Nasir Hamid followed Parr around Oxford over the course of the project and photographed him at work. The slideshow below shows some of those behind-the-scenes moments.

About his experience Nasir said:

“Oxford is my home town and I am passionate about photography and documenting life in this wonderful place — whether that’s town or gown or anything in between. When I first heard that Martin Parr had been commissioned to work on a photography book about Oxford I wondered if I would bump into him on the streets as I went on my usual lunch break photo walks. Would he be living in Oxford to immerse himself in the project, documenting daily life? I later realised that the project would be less town, more gown and would be carefully managed with only specific events and places photographed but our paths did cross more than a few times and it was on those occasions that I decided to document a photographer at work.

Trashing

They’re behind you! Martin Parr turns his back on the action to browse images on his digital camera during Trashing. After their final exam, students are trashed by friends and colleagues as they leave the back of the examination hall. This involved much foam spraying, drinking, an exploding bottles of champagne or fizz. Photo courtesy of Nasir Hamid.

Bake sale at Oxford University Press

Martin Parr browsing images on his digital camera after photographing items in a home baking cake sale at Oxford University Press. Photo courtesy of Nasir Hamid.

May Day buttie

Martin Parr chased after this man carrying a sign for free bacon butties on May Day in Oxford. On May Day at 6 am the choir of Magdalen College sing the Eucharist. Huge crowds gather underneath the tower to watch and listen.

Photo courtesy of Nasir Hamid.

May Day walking tree

The walking tree is a regular feature on May Day in Oxford. These May Day revellers jumped in the way as Martin was about to photograph the walking tree. They were not photographed. Photo courtesy of Nasir Hamid.

Meeting space at Oxford University Press

Meetings in progress. Informal meetings taking place in an open plan setting at Oxford University Press. Photo courtesy of Nasir Hamid.

May Day

Martin Parr among the crowd on May Morning in Oxford. Photo courtesy of Nasir Hamid.

Summer Eights

Amongst the crowd of spectators, Martin Parr captures The Syndicate’s dance routine at Summer Eights, four-day rowing regatta of bumps races. Photo courtesy of Nasir Hamid.

Knitting at Oxford University Press

Martin Parr snaps the Oxford University Press knitting group. Photo courtesy of Nasir Hamid.

Featured image credit: 54 St Aldates by London Road. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post A photographer at work: Martin Parr behind the scenes appeared first on OUPblog.

National Beer Lover’s Day playlist

7 September is National Beer Lover’s Day, a day to celebrate a shared passion for a drink that has been brewed for over 5000 years. Why not enjoy your favourite lager or ale with some beer-related music to get you into the spirit of things.

Our beer-infused song selection takes you from the cheery delights of The Housemartins’ “Happy Hour” to Julian Cope’s salute to the dead “As the Beer Flows Over Me”, from Psychostick’s eloquent praise of the amber liquid to the Oktoberfest staple “Ein Prosit.” Chris Young advises us how to behave in case of drought in “Save Water, Drink Beer”, as well as plenty of other ballads, anthems, and plain old drinking songs to provide the soundtrack to your Beer Lover’s Day celebrations.

Featured image credit: snow restaurant mountains sky by Tookapic. Public domain via pexels .

The post National Beer Lover’s Day playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

10 facts about the bassoon

Rising to popularity in the 16th century, the bassoon is a large woodwind instrument that belongs to the oboe family for its use of a double reed. Historically, the bassoon enabled expansion of the range of woodwind instruments into lower registers. The modern bassoon plays an important role in the orchestra due to its versatility and wide range.

The bassoon plays the role of tenor and bass in the orchestral double reed section (the oboe and English horn play soprano and alto, respectively).

Bassoons come in two sizes: the bassoon, and the double bassoon or contrabassoon, which sounds an octave lower than the bassoon.

Early bassoons were made out of harder woods, but the modern instrument is typically made of maple.

One of the precursors to the bassoon, the dulcian, was made out of a single piece of wood.

A double reed is used to play the bassoon, which is made out of a cane called an arundo donax. The finishing of a reed varies between French and German bassoons: French reeds are beveled, whereas German reeds have a thicker spine down the center.

Bassoons are made up of several parts including tenor or wing joint, the double or butt joint, the long or bass joint, the bell joint, and the crook or bocal.

Image credit: “IMG_1180.jpg” by Tom Page, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: “IMG_1180.jpg” by Tom Page, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.The “compact” version of the double bassoon stands at 122cm tall with a bore length of 5.5m.

The modern contrabassoon is folded several times to make its great length more manageable. Although the fingering is largely similar to that of the bassoon, the toneholes are covered by keys acting on rod-axle mechanisms, which transmit the player’s finger motions efficiently over long spans.

A mute is sometimes used in order to help play the instrument softly. The effect is made either by stuffing a piece of cloth into the bell of the instrument or using a sleeve-like metal cylinder.

In the 20th century the use of the German bassoon gradually became more universal. The global standardization of the bassoon types in the 21st century has been brought on by the ever-increasing demands of conductors and recording producers for the power of sound, homogeneity and balance.

Featured image: “Ensemble Deva – Carnival of the Animals (14th Jun 2016)”. Photo by Mark Carline. via Flickr .

Information for this post was sourced from the “Bassoon” entry by William Waterhouse and James B. Kopp in The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, 2nd ed. on Oxford Reference.

The post 10 facts about the bassoon appeared first on OUPblog.

“O dearest Haemon”: the passionate silence of Sophocles’ Antigone

Anyone reading Sophocles’ Antigone in the Oxford Classical Text of 1924, edited by A. C. Pearson, will sooner or later come across the following passage:

This translates as:

Ismene: But will you kill your own son’s bride?

Creon: Others too have fields that can be ploughed.

Ismene: But these other marriages would not be as suitable as this is for him and for her.

Creon: I hate the idea of evil wives for my sons!

Antigone: O dearest Haemon, how your father dishonours you!

Creon: You are paining me too much, you and your marriage!

Ismene: Will you really deprive your son of this woman?

Creon: It is Hades who will put a stop to this marriage.

Antigone has defied Creon’s decree that the body of her brother Polynices, who had recently fallen in battle when waging war against his homeland of Thebes, should be left unburied; discovered, she has been brought before the new ruler, whom she defies to his face, asserting the primacy of the gods’ laws over human ordinances and tauntingly urging him to exact his punishment. Her sister Ismene now intervenes, claiming (wrongly) that she too was guilty of the burial and asking to share the penalty; in the passage above, she begs for Antigone to be forgiven, reminding Creon that Antigone is betrothed to his own son Haemon.

Image Credit: From ‘Edipo re, Edipo a Colono, Antigone’, Adolfo de Carolis (1929). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: From ‘Edipo re, Edipo a Colono, Antigone’, Adolfo de Carolis (1929). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Line 572 has troubled editors of the play for over half a millennium. In the mediaeval manuscripts it is attributed to Ismene–but manuscripts have no authority in such matters, since line attributions were added long after Sophocles’ death by people with no better knowledge of his intentions than we have. The first printed edition of Sophocles, the Aldine published in Venice in 1502, gave the line to Antigone, turning it into a sudden revelation of Antigone’s otherwise unmentioned love for her fiancé. This attribution proved long-lasting and popular; as well as in Pearson’s edition, it appears in the great commentary of Sir Richard Jebb (1900), in whose opinion “it seems certain that the verse is Antigone’s, and that one of the finest touches in the play is effaced by giving it to Ismene…This solitary reference to her love heightens in a wonderful degree our sense of her unselfish devotion to a sacred duty.” A memorable production of the play at New College, Oxford in 2016, directed by David Raeburn, gave the line to Antigone; its passionate delivery was a high point in the performance.

Yet on a formal level, it would be extraordinary for the line-by-line exchange between two characters (“stichoymythia”) to be briefly interrupted in this way by a third party: that doesn’t really happen elsewhere in Greek tragedy. Just as importantly, giving the line to Antigone involves a misreading of her character. In the words of the most recent commentator on the play, Mark Griffith, “it is…much more characteristic of the warm-hearted Ismene to express such concern, than of Antigone, who is already devoted to death and never utters a word about Haimon or her feelings for him.” Sophocles’ Antigone is focused on her brother alone and on the burial of his body. Giving the line to Ismene not only preserves the regular stichomythia–it presents us with an Antigone, usually the most eloquent of tragic characters, who remains purposefully silent, leaving to others the discussion of her marital prospects. As often, the highly formalised conventions of Greek tragedy do not constrain Sophocles’ artistry; rather, his artistry lies in putting those conventions to use.

The newer Oxford Classical Text edited by Sir Hugh Lloyd-Jones and Nigel Wilson and first published in 1990 gives the line back to Ismene. But the Aldine’s attribution to Antigone has not disappeared altogether. It remains there in a note in the apparatus criticus, reminding readers of a dispute between scholars which has lasted centuries, and which all readers must attempt to decide afresh for themselves, without simply relying on the authority of any edition – or blogpost.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Antigone in front of the dead Polynices’ by Nikiforos Lytras (1865). National Gallery of Greece. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post “O dearest Haemon”: the passionate silence of Sophocles’ Antigone appeared first on OUPblog.

September 6, 2017

A few bogus etymologies: ‘’tantrum,” “dander,” “dandruff,” and “dunderhead,” along with “getting one’s goat”

Bogus, tantrum, and dander are fairly recent additions to the vocabulary of English. Like so many newcomers, they are words of unknown etymology. My greatest ambition is to promote their status from “unknown” to “uncertain.”

It is tantrum that will first engage our attention. Those who risked saying anything on the source of this word suggested the Celtic origin as a remote possibility. Most unfortunately, a search for the origin of tantrum on the Internet returns us again and again to Charles Mackay’s book on the Scots Gaelic etymology of the languages of Europe. Mackay, a poet and songwriter, who knew a good deal about English and whose other books are still useful, entertained the bizarre notion that thousands of English words go back to Gaelic. The very idea that tantrum is a sum of two similar-sounding Gaelic words, even though such a sum does not occur with the meaning “an outburst of anger” in any Celtic language, is implausible, to say the least. And in general, dissecting a hard word into segments and producing a spurious compound should be dismissed as adventurism. E. Cobham Brewer, the author of the once immensely popular Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, explained dander as d(amned) anger. Gullible people have repeated this etymology more than once.

Tantrums: a devilish trick.

Tantrums: a devilish trick.The Latinized ending of tantrum should not trouble anyone. Even if some wag of the past added –um to tantra, the word owes nothing to Latin. I believe the safest clue to the origin of tantrum is the name of the devil Tantrabobus (Tantrumbobus, Tantarabobs, Tantraboobs, and other variants). Bobus has as little to do with Latin as bogus (about which more will be said later), tantrum, conundrum, panjandrum, and cockalorum (on conundrum and panjandrum see my post for 3 December 2008). Tantrumbobus is a relative of Flibbertigibbet, Hoberdidance, and Obidicut (also known as Haberdicut), the fiends mentioned in King Lear. I wonder whether English dander “to walk around; to talk inherently” and especially Old High German tantaron “to be out of one’s mind” are kin of the British devils, and, if so, whether those devils were also known on the continent. Tantrabobus and the rest were applied in some British dialects to a noisy child (likewise, in the US the word has been attested as a jocular term of endearment) and to a great noise made by children, that is, they designated ruckus, rumpus, or fracas. (If you want to increase your etymological despair, look up the origin of those three words: you will come away none the wiser but a good deal sadder.)

This is the most authentic image of our Tantrabobus.

This is the most authentic image of our Tantrabobus.In Joseph Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary, the mysterious triad antrims ~ antruns ~ antherun, a close synonym of tantrum, occurs. Webster’s International 1, 2 mentions it in a noncommittal way, but there is no way of knowing what to do with it, and in the third edition the reference disappeared. More importantly, in dialects, tantrum has the variant dandrum, defined by Joseph Wright as “a whim, a freak; ill-temper.” We recognize it in the form dander, because it occurs in the phrase to get one’s dander up. Dander is “ferment in working molasses,” a putative variant of dunder “lees of cane juice”; the latter has been traced back to Spanish. Dander in the idiom and dander “ferment” may be related, but it is more likely that they are not: dander in to get one’s dander up looks more like dandrum without its pseudo-Latin ending. Dander is also a piece of the vitrified refuse of a smith’s fire or a furnace, and there have been attempts to connect it with tinder.

The names of fiends, like those mentioned above, are more or less fanciful coinages and their origin is hard to trace, but, if dandrum historically preceded tantrum, then it resembles thunder, possibly a sound-imitative word like ding-dong, thud, and thump. My main suggestion can therefore be summarized as follows: there was an onomatopoeic word for “noise,” something like dunder ~ dander ~ tanter. Dunder too might have been used as the first element in the name of a noisy devil, assuming that dunder is related to din, more or less as does the word dunderhead (British dialects have the variants with –knoll, –noddle, and –prate in this compound, and John Fletcher knew the noun dunderwhelp). As to dunder, in the north it may mean “to rumble; to strike with a loud noise.” Who is a dunderhead? A person making lots of noise but saying nothing of consequence or someone who was knocked on the head and lost his wits? Tantrums are usually associated with an outburst of bad temper in children, so that the imp responsible for such hissy fits must have been some sort of bogey, a Eurasian bogyman, a relative of the Russian buka. Children believed that, unless they behaved, the bogey ~ buka would come and fetch them.

The bogey’s next of kin was, apparently, the bogus ~ bobus. Late in the eighteenth century, tantrabobus ~ tantrabogus, a Vermont colloquialism for an odd-looking object, was recorded, while bogus surfaced as an American name for an apparatus that produced counterfeit money. Most certainly, all those Americanisms (dander also surfaced first in the US) were at one time taken overseas by colonists as so-called British provincialisms. Bogus has the reputation of a word of unknown etymology. I think we encounter a familiar devil, now minting false currency. Later, this creature was made responsible for all kinds of false things. The origin of the variation in bogus ~ bobus is again familiar: in such words, both vowels and consonants play the familiar games allowed in expressive formations.

Goosey goosey gander plotting its next move.

Goosey goosey gander plotting its next move.Although condemned by all, the phrase to get one’s gander up occurs with great regularity. This variant is hardly the result of folk etymology (in this case, gander substituted for the unfamiliar or incomprehensible dander). Since old days, gander might have been a euphemism for “penis” or “amorous man” (in our unbuttoned age, we call such males horny), as follows from the narrator’s peregrinations in the nursey rhyme about the innocently-sounding goosey-goosey gander. But perhaps to get one’s dander up gave rise to the facetious model “to raise an angry beast in one.” Consider to get one’s goat, which also has the variant with up at the end. Those idioms were coined in America. The familiar idea that to get one’ goat owes its origin to horse racing looks like a poor joke.

Thor certainly got his goat(s).

Thor certainly got his goat(s).Dandruff is the hardest word of all beginning with dandr-. If dander “ferment” is a variant of dunder “lees,” I have nothing to say. But if it is a different word and if at one time it had some vague sense of “dregs, refuse,” it may perhaps be the root of dandruff, while –ruff has been referred to the Germanic word for “scab” and the Roman words borrowed from Germanic (those are usually discussed at ruffian). Later it might have been associated with rough. Consider also riff raff, which is usually traced to French, but its place of origin is Germanic. Finally, I may mention the shrub woodruff; the origin of its second element is “unknown.” In any case, the Celtic sources of dandruff (suggested more than once) should be rejected for want of evidence. Be that as it may, dandruff, however irritating, has probably nothing to do with dander “anger” or any of the devils that have boggled our collective mind us today.

Image credits: (1) “Tantrum” by Jonty, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. Featured image and (2) “Doolagahl (Aboriginal equivalent of Bogeyman) by Steaphan Paton” photo by Nagarjun Kandukuru, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (3) Goose by Domenic Hoffmann, Public Domain via Pixabay. (4) “Christmas throughout Christendom – Thor” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A few bogus etymologies: ‘’tantrum,” “dander,” “dandruff,” and “dunderhead,” along with “getting one’s goat” appeared first on OUPblog.

Don’t play politics with the debt ceiling

It must be frustrating to be a Congressional Democrat these days. The minority party in both the House and Senate and having lost the White House, the only thing keeping the Democrats relevant is a dysfunctional White House and a disunited Republican majority in Congress. Watching the Republicans run out the clock on President Obama’s last Supreme Court nomination and then whisk through President Trump’s first SCOTUS nominee by paring back the filibuster must have been painful.

Democrats have taken any and all available measures to stymie the Republican’s attempts at passing unilateral measures, such as health care. They are perfectly justified in doing so. There is, however, one area in which they should drop any obstructionism and play ball with the Republicans—raising the debt ceiling.

Although the debt ceiling has been in the news repeatedly during the past two decades or so, it is still a somewhat obscure concept. It can be easily explained with the following analogy.

Imagine that you and your spouse have just finished a meal at an expensive restaurant only to discover that, not only do neither of you have any cash, but that you have maxed out your joint credit card. The restaurant staff seem to be calm, but the maître d’ looks like he is about to call the police.

What should you do?

Well, if your credit is decent, you might want to try calling the credit card company and asking them to increase your limit. After all, your credit is pretty good. The problem is that your spouse, a joint signatory on the card, will not agree to make the request unless you accept certain conditions: you will agree to work additional overtime hours to bring in more money and cut back on some of your cherished spending priorities, like that new car you have in mind. If you don’t acquiesce, you’ll have to face the consequences with the angry maître d’.

The US government will find itself in a similar situation this coming fall when it runs out of both cash and credit. Unless Congress and the Administration can agree to allow the US government to borrow more money, the government will default on its debt. The consequences of a default would be catastrophic, roiling financial markets and making it much more expensive for the US government to borrow. Even the threat of a default would be costly for the government and the country.

US Public Debt Ceiling 1981-2010 by Unforgettable fan. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

US Public Debt Ceiling 1981-2010 by Unforgettable fan. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The debt ceiling originated one hundred years ago, in the midst of World War I. At that time, Congress decided that it could no longer micromanage the government’s finances, issuing specific bonds to pay for each and every substantial government project. Instead, it authorized the Treasury to borrow up to a certain amount to finance all government spending. That limit currently stands at just over $19.8 trillion.

The debt ceiling was not controversial for most of its existence. Whenever the government’s debt approached the legal limit, Congress and the Administration agreed to increase the ceiling without much fuss or fanfare. In this way, the debt ceiling has been raised 78 times since 1960, under both Democratic and Republican congresses and administrations.

The debt ceiling became much more politicized after Newt Gingrich and the Republican Party swept into power following the 1994 congressional elections. Gingrich’s “contract with America” called for reducing the size of the federal government, and when then-President Bill Clinton did not cave in to Republican demands for certain spending cuts, Gingrich threatened to refuse to hold a vote on a debt ceiling increase, saying: “I don’t care what the price is.” He eventually relented. The government again came close to defaults in 2011 and 2013 when Republican majorities in Congress threatened not to raise the debt ceiling if then-President Barack Obama did not accede to their demand to impose spending cuts, particularly those meant to eviscerate the Affordable Care Act pressed by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX). In both cases, after nail-biting negotiations, the debt ceiling was raised—but not before the uncertainty caused by the impasses increased the interest rate that the government had to pay on its debt, imposing millions of dollars in higher borrowing costs on American taxpayers.

Because all the levers of power in Washington are in the hands of the Republican Party, it would be reasonable to conclude that raising the debt ceiling will not pose a political challenge this fall. Such a conclusion would be premature.

During the past months, Donald Trump has threatened to shut down the government if Congress does not accede to his demands to fund a border wall and to force creditors to take less than the amount that they are owed on US government debt. Hence, it is possible that the loose cannon president could take some impulsive action that would lead to a default. Even if Trump is talked out of such a strategy by the more sensible members of his administration, Republican Congressional hardliners like Ted Cruz have demonstrated their willingness to push the government into default.

Because of these uncertainties, Democrats in Congress should announce that they will not block, delay, or try to attach any amendments to legislation that would raise the debt ceiling. Combined with the majority of sensible Republicans who would also support such a move, the Democrats could effectively defuse threats from both Republican hardliners and an increasingly unstable president. No matter how bitter they are about their recent losses and no matter how many times they have been the victims of nasty fiscal tactics from the other side, the Democrats must not play politics with the debt ceiling.

Featured image credit: US Capitol at dusk as seen from the eastern side by Martin Falbisoner. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Don’t play politics with the debt ceiling appeared first on OUPblog.

Can burlesque be described as “feminist”?

Is burlesque an expression of sex-positive feminism, or is it inherently sexist? In the following excerpt from The League of Exotic Dancers: Legends from American Burlesque, documentarian Kaitlyn Regehr and photographer Matilda Temperley share narratives by burlesque dancers who embraced this form of art as an early expression of women’s rights.

We also recently sat down with Kaitlyn and Matilda to discuss the history of burlesque in America. Watch the video below to hear Dr. Regehr’s perspective on the complicated relationship between burlesque and feminism.

On discovering Exotic World in Helendale, California, and thence the Exotic Dancers League, the neo-burlesque community embraced these women as their alternative feminist foremothers. The newcomers considered the EDL members the embodiment of their beliefs about body acceptance and identity. They saw legends and their lifestyles as subversive in the way these women physically displayed alternative outlooks on aging and sexuality. However, for many of the legends, particularly some of the older ones, these ideas seemed alien to their experience of burlesque. Their original performances were based on mainstream ideals of sex, consistent with the time period in which they were dancing, with their main focus being the sexual arousal of men. Further, some dancers, particularly those who had begun performing in the 1950s, felt the women’s movement was a negative impact on their careers and thus rejected it. This sentiment was touched on by [burlesque legend] Marinka when she recounted a protest outside of her theater in Iowa.

I was in a town called Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and the women’s movement was protesting outside. I was not very well received by those people doing the demonstration, some of these college girls outside the club every day, saying all what they used to say, “burn the bra, equality and this and that and the other.” I will say that had a lot to do [with the end of burlesque]. Some college girls were picketing in front of the club where burlesque dancers were performing. I never wanted after that to go back to that town. I didn’t like that town at all. But things like that were happening in the ’60s.

This sentiment, expressed by Marinka, suggests that not only did she not include herself in the feminist movement—let alone a college-based, anti-sex-work feminist group in Iowa—but also that she saw groups involved in the movement as actually protesting against and threatening both her and her way of life. In addition, she attributes the feminist movement with the end of the burlesque theaters and the further marginalization of burlesque. As [burlesque legend] Tempest Storm noted, women’s patronage is often thought to gentrify and legitimize an entertainment form. Conversely, either the lack of women or the absence of support for women can push entertainment further underground.

I entered this community of exotic dancers with a similar hope of interpreting these legends as the unsung feminists of the twentieth century, perhaps believing they might be depicted as an untold women’s movement. Many, however, were uninterested in carrying such a label. Below is an excerpt from my interview with Jo “Boobs” Weldon, the first interview I conducted early in my time with the community. Weldon exposes my preconceived notions and calls for a wider lens for viewing the experiences of these dancers, one that would take into account the hardship in many of these women’s lives and the choices available to them.

The thing that you were saying about feminist icons, when I was young and I saw these women that did burlesque and I could tell that they weren’t necessarily having an easy life. But they looked self-invented; they looked like—the phrase I use is that they made glamour out of adversity. Some of them have had seventeen abortions, but they were still proud of carving out their own lives. So they had these really difficult lives … they started when they were teenagers and most of them didn’t have ballet training or whatever, and what I find feminist about them is that they own it [their lives] and they are not ashamed of it. They are, at least financially, empowering themselves, their families, and their communities. I don’t necessarily think that stripping is feminist per se, but I think that you can be a stripper and be a feminist. I don’t necessarily think that burlesque is feminist per se, or vintage burlesque was feminist per se. But any time I see women making a decision, even if they are forced to it and they having a hard time, to take things into their own hands and [think], I’m going to control at least this much, that is empowering to see.

Weldon’s term “glamour out of adversity” links to a concept expressed by Burlesque Hall of Fame director Dustin Wax. He proposed that many of the new burlesque performers “filtered flamour out of burlesque” when noting that neo-burlesque performers don’t say, “I’m going to go into this so that I can do this shameful horrible thing, and constantly be subject to physical intimidation and manhandling. It’s a personal choice that [these] people have made in sort of reviving this art form … They [the resurgence] transformed burlesque into primarily a theatrical art, rather than a sort of strictly erotic entertainment in the back room of a seedy bar.

However, Weldon’s comment suggests that what some new burlesque performers often choose to filter out is arguably the very thing that might make these women feminist or empowered. The resurgence often separates twentieth-century burlesque from “stripping” and a variety of social issues associated with the sex industries (e.g., abuse, objectification) in order to enjoy burlesque as an empowering, feminist “art form”; however, Weldon states that it is the ability to survive in spite of these issues that is perhaps even more “glamorous.”

Featured image credit: Courtesy of Matilda Temperley. Please do not re-use without permission.

The post Can burlesque be described as “feminist”? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers