Oxford University Press's Blog, page 325

September 16, 2017

Boredom’s push

“I painted because I was bored.” G.W. Bush

There are crimes of passion, those of rage and of love. And then, there are crimes of boredom. Arson, animal abuse, and murder have all been committed in the name of boredom. “It is very curious,” the nineteenth century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard once noted, “that boredom, which itself has such a calm and sedate nature, can have such a capacity to initiate motion.” Kierkegaard’s observation was remarkably prescient.

In a much-discussed series of studies, University of Virginia psychology professor Timothy D. Wilson and colleagues touched upon boredom’s power to initiate motion indirectly when they set out to investigate whether or not distraction-free and deliberative thinking is enjoyable. In six of their studies, they gathered a total of four hundred and nine college students and instructed them to entertain themselves only with their thoughts for six to fifteen minutes in a “sparsely-furnished room in a psychology building.” Once the thinking period was over, participants were asked to rate their levels of enjoyment, entertainment, and boredom. On average, participants found thinking somewhat enjoyable, somewhat entertaining, and somewhat boring. Participants didn’t love their thinking period. But they didn’t hate it either.

Still, Wilson and colleagues concluded that “just thinking” is something that most people don’t enjoy. Even though first-person reports don’t establish their conclusion, the results of an additional study (study 10) are more supportive of their outlook on thinking. For this study, they asked again participants to entertain themselves alone with their thoughts. However, in this variation of the experiment, participants were allowed, if they were so inclined, to self-administer a mildly unpleasant electric shock, one to which they were exposed prior to the thinking period. Focusing only on participants who before the thinking period stated that they would pay not to receive the shock again, they found that twelve out of eighteen men and six out of twenty four women chose to shock themselves at least once. Wilson and colleagues concluded: “what is striking is that simply being alone with their own thoughts for 15 min was apparently so aversive that it drove many participants to self-administer an electric shock.”

Although widely publicized, the conclusion of Wilson et al.’s shock study has been contested (see here but also here). Whatever one makes of Wilson et al.’s findings, it is instructive to consider what the subjects themselves said about the shocks. Four subjects cited boredom as the reason for shocking themselves, one of whom had this to say: “I chose to willingly shock myself because I was so bored during the thinking period that I chose to experience the mild unpleasant shock over the oppressive boredom.” Perhaps what Wilson et al.’s shock study demonstrated isn’t the aversive character of thinking but the motivational power of boredom. But would one really shock oneself just to escape boredom?

Two recent studies suggest so. In the first one, Remco C. Havermans and his colleagues at the University of Maastricht tested whether the induction of boredom was capable of motivating participants to seek a change in stimulation. They found that individuals in a monotonous, boring condition ate more chocolate (M&Ms) and shocked themselves both more often and with higher intensity than individuals in a neutral condition. Havermans and colleagues concluded that boredom is such an aversive experience that some individuals would choose to subject themselves to negative stimuli in order to make it go away.

Is there something unique about boredom that motivates one to seek ways (even unpleasant ones) to escape from it, or is this a feature that boredom shares with other negative emotions? In a 2016 study, Chantal Nederkoorn and colleagues (one of whom was Havermans) set out to answer this question. Sixty-nine participants were randomly divided into three conditions: a boredom condition, a sadness condition, and a neutral condition. In each condition, participants viewed a 60-minute segment of a film that was supposed to induce, respectively, boredom, sadness, and no specific mood. While watching the film, participants had the option to self-administer electric shocks. What the researchers observed was that compared to the neutral and sadness condition, the onset of boredom gave rise to an increase in the total number of self-administered electric shocks. Their study not only confirmed Havermans et al.’s previous findings but also showed that the reason why individuals chose to self-administer shocks is not to avoid emotional experiences in general but rather to escape boredom specifically.

Drawing of Søren Kierkegaard based on an 1840 drawing by N.C. Kierkegaard. J. Borchert, The Royal Library, Denmark, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Drawing of Søren Kierkegaard based on an 1840 drawing by N.C. Kierkegaard. J. Borchert, The Royal Library, Denmark, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.What do such findings show? At first sight, they seem to demonstrate boredom’s toxic nature. After all, they are consistent with previous studies that reported a relationship between boredom and a tendency to engage in risk-taking activities. But such a grim picture of boredom is both partial and inaccurate. Boredom is neither essentially nor irredeemably problematic. It is a powerful affective state that can at once disengage us from uninteresting or meaningless situations and move us away from them but not necessarily toward negative, self-destructive actions, as the studies would have us believe. Boredom informs us of the fact that what we are currently doing is not what we want to be doing and propels us to do something else. What that something else is, however, is never spelt out by boredom. Boredom carries us only part of the way. For the rest, we are on our own.

In the presence of boredom, we are called to cope with its silent force. As such, boredom needs direction. Its motivational capacity could be put to use only if we know both how to read its presence and how to respond to it. Listening to what boredom tells us when it arises and being able to use its motivational power can help not only to reduce the duration of our a boring experience but also to increase the chances of later finding ourselves in situations that are in line with our interests. Boredom occupies an important role in our lives. We should neither underestimate it nor ignore it. Its power may shock us.

Featured Image credit: Photo by Mihai Surdu, CC0 via Unsplash .

The post Boredom’s push appeared first on OUPblog.

September 15, 2017

Who is the expert on your well-being?

Consider a syllogism:

There is now a science of well-being.

Scientists are experts in their field.

Therefore there are now experts on well-being.

I submit this argument is sound–which is to say the premises are true and the conclusion follows validly. But it does not imply that there is a scientific way to live your life and does not imply that science should supersede your own judgment or the judgment of your therapist, rabbi, or wise friend. There are different ways of knowing well-being and none is superior to another in every way.

The “science of well-being” (aka positive psychology, quality of life or happiness studies) applies scientific method to what was previously personal, inscrutable, philosophical–happiness and good life. These scientists say that today measures and methods are so much improved, that happiness and good life are no longer hidden, no longer elusive. They also tout great practical payoffs–typically evidence-based therapies and truly scientific self-help. Increasingly the discoveries of this field are picked up by businesses, human resources managers, life coaches, and indeed governments.

As citizens, employees, and clients we would be wise keep our eye on this new development–knowledge is power and power over happiness is far from innocent. But here I pose the question purely from an individual’s point of view – is it wise to arrange your life in accordance with the findings of this science?

Consider some things scientists of well-being claim to know:

“Unemployment and loss of mate are the hardest to adapt to.”

“Rise in income only predicts rise in well-being in the presence of other factors.”

“Pro-social behavior increases the givers’ subjective well-being.”

If you want to know whether to avoid unemployment and loneliness, pursue better income, volunteer, or do whatever else the science recommends, you need to notice two things. First, these claims are value-laden. Second, they are about kinds of people, not individuals. These two features imply two ways in which this knowledge might fail to fit you – first, because you reasonably disagree with the value judgments these scientists make and, second, because their claims are not about you. Let me take each in turn.

When I say that the claims of this science are value-laden, I mean simply that a value-judgment about good life is needed to identify a questionnaire as valid, or a given data point as relevant. ‘Answers to a life satisfaction questionnaire are valid indicators of well-being’ is a value judgment because it presupposes that it is good for a person to judge her life as living up to some ideal she has adopted.

The process of arriving at a good measure of well-being is the process of making such judgments at many stages: what questions to include, to whom to pose them, which other questionnaires are related, and so on. Following much statistical testing, questionnaires that emerge are complex amalgamations of the factual and the evaluative. This is totally normal and legitimate – there would be no science as we know it if scientists did not use metaphors, analogies, judgments – all seats of commitments about morality, politics, beauty, and culture.

But scientists are not the only authority on values. Judgments about good life are familiar to all of us. My nine year old wants to make YouTube videos and wants help to record his gaming sessions and upload them online. I want to encourage his creativity, but worry about exposing him to the world of ‘likes’ and anonymous comments earlier than need be. Many of my everyday decisions are decisions about well-being: mine, my family’s, my students’. Sometimes I make a mess of things but I still have some expertise about living my life. Classic liberals, such as John Stuart Mill, held the extreme view that only the individual is an authority on their own well-being. This flies in the face of facts – we can be blind to things that people who know and care about us can plainly see. Equally scientists who validate questionnaires of well-being can also make decent value judgments on this matter – clinical researchers usually go to great lengths to ensure that when they measure, say, frailty they define this value-laden concept properly and comprehensively. Most likely there is more than one authority on values, including on well-being.

It follows that claims about validity of a given well-being measure can be challenged by challenging the value judgments on which they depend. ‘You used life satisfaction data in your study, Dr. Scientist, but I have reasons to believe that life satisfaction is not well-being’. No special expertise is necessary to raise such challenges. They need to be made in good faith, with attention to why scientists choose a given measure, and with due reflection, but they can be made. And this is one way in which the claims of well-being science can fail to be relevant you.

The second way stems from the inevitable and justifiable focus on kinds rather than on individuals. My point is not just the familiar idea that scientific hypotheses are about averages and any individual may deviate from average (of course most of us often wrongly believe we are well above it). This is true but unsurprising and can only justify ignoring science if you have strong evidence regarding which side of the distribution you are on. Rather when checking that a given claim of science is properly about us, we should check whether ‘the kind’, that is the class of people, about whom this claim is made, is the kind to which we belong.

Positive psychologists who write books with happiness formulae sidestep this issue and advertise their findings as applying to humans in general – pick a job you love, maintain positive relationships, do your gratefulness exercises, volunteer, find meaning in life. But such vague generalities only take you that far in life. Better grounded is research that zeros in on people in specific circumstances – caretakers of the chronically ill, single mothers on welfare, refugees, adopted children, psychosis patients, and so on. People in these similar circumstances people tend to face similar challenges, or at least more similar than when you consider humanity as a whole. As a result they yield more informative evidence. Clinical research and social work is a treasure trove of knowledge about how to live well with a particular illness, particular disability, or particular challenge. In contrast with positive psychology, these are more modest and more local findings.

To make the same point with pictures, science that promises this:

Five Ways to Wellbeing postcard. Image used with permission from the Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand.

Five Ways to Wellbeing postcard. Image used with permission from the Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand.Is far less reliable for individuals than science that promises this:

Image courtesy of the author.

Image courtesy of the author.If there are findings on well-being relevant to the kind to which you belong, good, use them. Nevertheless, because each of us is a member of many different kinds, the authority of these findings will again quickly run. What do you do when you have psychosis and you are a single parent, and when studies exist about well-being of each, but not at the same time? You think for yourself and you ask for advice (of which science is but one source).

Mine is not a criticism, just an observation that well-being as an object of science is not well-being as an object of personal reflection. Living well is as big of a riddle as ever, even in the age of positive psychology.

Featured image: balanced stones. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Who is the expert on your well-being? appeared first on OUPblog.

How to fight climate change (and save the world)

The ice caps are melting. Within a few years the North Pole will likely be ice-free for the first time in 10,000 years, causing what some call the “Arctic death spiral.” In the following excerpt from A Farewell to Ice, Peter Wadhams explains what we can do today to fight climate change.

What can we do, both individually and collectively, to try to save the world? There is a massive list, of course, but I will pick out a few actions that might make a real difference.

First, counter with all the power at your disposal the sewage-flow of lies and deceit emitted by climate change deniers and others who wish us to do nothing and hope that it all goes away. It will not go away. Be especially vigilant of the sinuous misrepresentations of politicians, from prime ministers downwards, and look out for glaring anomalies between what they say and what they do. When they sign up to a solemn international agreement in Paris to radically curb carbon emissions, then withdraw the feed‑in tariff on solar power, fail to support renewable energy research and development, and seek to expand fossil fuel use through fracking, you know they are hypocrites and you can point out to your elected representatives that they will lose your vote unless they shape up. Scientists who study climate change should be among the first to speak up, and should be prepared to risk the blighting of their careers and the absence of establishment honours. At least they will no longer be burned at the stake, and, as the reality of climate change begins to bite, scientists who have had the courage to speak out will be respected rather than being abused and threatened.

Second, in your own life adopt every possible measure that will reduce unnecessary energy use, especially of fossil fuels. Why are more homes not insulated? This is the most energy-effective thing that you can do to your house, and from time to time a reluctant government even offers grants to assist you. Drive an economical car or ride a bike – many commutes and other types of journey in a town or city can be managed very effectively by electric bicycle. Install solar panels on your roof, even if you don’t receive a feed‑in subsidy.

“…as the reality of climate change begins to bite, scientists who have had the courage to speak out will be respected rather than being abused and threatened.”

Third, on a national scale, insist that the government changes the basis of power generation. Britain is particularly remiss in this respect. In 2015, 82 per cent of our energy still came from fossil fuels. We are world leaders in the inventive development of wave power and current turbines, and have the marine environment to exploit these new ideas, whether it be our wave-lashed west coast, the fast-flowing currents between the Orkneys, or the Severn bore. Yet only pitiful amounts of funding support come from the government for the pioneers of these new energy systems. Only recently, innovative and deserving wave power companies have closed down for lack of support. The UK has huge wind resources, but has never even tried to manufacture wind turbines, leaving this to Denmark. Solar photovoltaic power is becoming cheaper all the time, and is suitable not only for home use but for larger solar farms, even in the grey UK. The problem of energy storage, which is a real one (the sun doesn’t shine at night), is near solution, both from bigger batteries and from flow conversion systems, which store energy in chemical fluids contained in external tanks, which work something like fuel cells and which can store massive quantities of energy limited only by tank size. A Harvard laboratory led by Professor Michael Aziz came up with a successful flow conversion system in 2014 using quinones (organic compounds) as fluids. All that is needed to put such schemes into practical operation is whole-hearted support from governments. Any plea (as in the UK) that there is no money because of austerity is bogus, because renewable energy is – in fact, has to be – the energy source of the future, so we have to adapt to it and should lead the change so that our own industry can build the new technology.

On an international scale, as I have said, the overwhelmingly important need is to undertake a colossal scientific and technical research programme on geoengineering and on carbon dioxide removal. Geoengineering is necessary to hold warming back, because we are unlikely to reduce our carbon emissions fast enough, but there are huge questions of science, engineering, and governance which need to be solved before we can proceed safely. We could, of course, simply build some cloud brightening systems and/or some aerosol distribution networks and try them out. Stephen Salter, for instance, has devised a sensitive test to see whether a vapour injection system is actually having a detectable effect or not. But if we want to be safer we have to develop a research programme on modelling the impact of geoengineering techniques before we start to deploy them on a large scale.

Most important of all is the need to find a way to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This is the only thing that we can really do to save the world, so we had better do it while we still have the technical capacity and the civilization to sustain it. I have shown all the drawbacks to the various indirect techniques of CO2 removal that have been suggested, from crushed rocks to biochar to afforestation and BECCS. The only one that can really save us is the direct removal of CO2 from the atmosphere through some device which sucks ordinary air in at one end and emits it again at the other minus its CO2 content, and does so at a less than impossible price. It is a problem in chemistry, physics, and technology, a giant problem, but not one that is greater than that of building a huge bomb out of a reaction which previously was only observed among single atoms in a laboratory. It is the most important problem that the world faces. If we solve it, our human civilization can continue, and we can devote our energies to all our other myriad challenges, from overpopulation to water and food shortages, disease and war. If we don’t solve it, we are finished. Along the way we will have said a farewell to ice, but if we stabilize our atmosphere and climate the ice may return for our descendants to wonder at and enjoy.

Featured image credit: “cold-glacier-iceland-melting” by Jaymantri. CC0 via Pexels.

The post How to fight climate change (and save the world) appeared first on OUPblog.

Discussing family medicine: Q&A with Jeffrey Scherrer

Family medicine plays a large role in day-to-day healthcare. To further our knowledge of the primary care landscape, we’re thrilled to welcome Jeffrey Scherrer, PhD, as the new Editor-in-Chief of Family Practice, a journal that takes an international approach of the problems and preoccupations in the field. Jeffrey sat down with us recently to discuss his vision for the journal’s future and his work in research and mentorship.

How did you get involved with Family Practice?

My Department Chair advised me to attend NAPCRG. While attending my first NAPCRG meeting in 2013, I made a visit to the Family Practice booth and asked if they were looking for reviewers. I was then invited to join the editorial board.

What led you to the field of family medicine?

I started my career in 1990 as a research assistant in animal models of memory. After developing really bad allergies to rodents, I sought out a research coordinator position in epidemiology during which time I also completed my doctoral degree in Health Services Research. In 2004 I received an appointment to Washington University Department of Psychiatry as an assistant professor. My research was in psychiatric epidemiology and I enjoyed the field but also realized that my interests were much broader than psychiatry. I thus sought out a new academic appointment in 2013 and joined the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Family medicine turned out to be a perfect home to pursue my over-arching research interest in the interplay of mental and physical health. I enjoy methods almost as much as the research question. Here, I can pursue my interests ranging from diabetes quality indicators to military veteran issues, to metformin and its association with dementia, while maintaining my funded research focus on risk factors for, and consequences of, mood disorders. Family medicine is a perfect home for me because I can pursue my eclectic interests while still focusing on mind-body relationships.

How do you see the journal developing in the future?

Without being too political, we need to educate our elected representatives so they understand the individual and societal costs of being uninsured. We have long ago accepted clean water as a standard, when will we see healthcare of equal importance?

First, I commend Dr. Neale’s successful term as Editor-in-Chief during which the journal’s impact factor continuously increased. To continue to grow our impact, we must increase reach into the United States. Many of my family medicine colleagues are unaware of Family Practice. I hope engaging family medicine and primary care professional organizations will encourage submissions and serve to disseminate the high quality research we publish. To encourage scientific discourse I would like to see the journal establish a stable volume of high quality editorials on published manuscripts. A recurring educational section on statistics and or methods would make the journal a unique resource for primary care researchers. I will also encourage authors to work with their institutions and the journal in developing press releases for their accepted papers. This can greatly increase our name recognition. I have several theme issues in mind that are related to many of the challenges faced by family medicine and general practice and I look forward to engaging the AEs in selecting these themes.

What do you think are the biggest challenges facing family medicine, general practice, and primary care today?

It might be easier to list the topics that are not big challenges! While I expect my opinions are biased by being a research professor in the United States, many of the major challenges in the US are also key problems in other countries. The prescription opioid epidemic, obesity, and diabetes rank in the top.

Although opioid prescriptions have levelled off in the United States, we are still witnessing an epidemic of overdose, misuse, and chronic prescription opioid use that no longer provides pain relief. We must find ways to manage pain with safer medications and therapies and provide patients realistic goals for analgesia and functioning.

Obesity is now a world-wide problem for adults and children. We know eating less, eating healthy, and exercise leads to weight loss but motivating patients to make lifestyle changes is a major challenge. I think primary care should be a leader in developing new interventions that increase patient engagement with weight loss and most importantly develop interventions that maintain weight loss efforts. Clever diets are not the answer. This is an area where integrated behavioural health professionals can have a significant impact. The increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes is one of many consequences of obesity. Early detection and novel interventions for lifestyle change in patients with pre-diabetes could mitigate this problem.

Using the full potential of electronic health records (EHRs) is also a challenge for many private practices. Without strong technical support, this tool becomes an electronic version of paper records. I would hope to see increasing integration of EHRs across regions and then across countries. One day the World Health Organization may have access to multi-national historical medical records to inform disease prevention and best clinical practices for unique subgroups of the patient population. Thus how to deliver precision medicine in primary care is among our research priorities. Patient portals linked to EHRs can help reach rural locations and coupled with telemedicine, rural health disparities could be reduced.

Even when guideline concordant care is provided and patients have insurance and no access barriers, there are many social determinants of health that may prevent some persons from regaining or maintaining health. If a patient intends to eat healthy and exercise but they have no access to safe neighborhoods and healthy foods, they are less likely to succeed. I would like to see more research on environmental factors that contribute to health services utilization, adherence, risk of disease, response to treatment, and disease. This field is advancing with the ability to merge geo-spatial data with EHRs and wearable health monitoring devices. I think this area is a good intersection for primary care and public health collaboration.

Professor Jeffrey F. Scherrer. Image used with permission.

Professor Jeffrey F. Scherrer. Image used with permission.Health insurance is a key challenge in the United States. At this time we are looking at efforts by Congress to repeal the Affordable Healthcare Act. All nations must recognize that healthcare is a means of maintaining a robust and productive society. Unfortunately, the right to healthcare is under threat in the United States. Without being too political, we need to educate our elected representatives so they understand the individual and societal costs of being uninsured. We have long ago accepted clean water as a standard, when will we see healthcare of equal importance?

Last, recruiting more medical students to family medicine and general practice is a priority, as is preventing physician burnout and promoting physician wellness.

Tell us about your work outside the journal.

I am currently the Principal Investigator on two NIH grants. One is focused on determining if treatment of PTSD and reduction in symptoms leads to better health behaviors, such as weight loss, and subsequently reduced risk of cardiometabolic disease. The other is designed to determine if metformin is associated with reduced risk of dementia. In addition to developing my own research, I mentor many junior faculty and clinicians to increase our peer reviewed, original research publications. I serve on several dissertation committees, conduct ad hoc grant reviews for NIH and the Veterans Administration, and participate in university committees to grow our research infrastructure. I love mentoring relationships because I often learn about a new topic and mentees bring new ideas and greatly appreciate the support I can offer them. Everyone needs mentors in research and as your career advances, we should all be mentoring junior faculty. The process of developing a research career is not taught in graduate school and is learned over many years by working with an array of more experienced investigators.

What are you most looking forward to about being editor?

I am excited about expanding the journal’s reach. There is no reason the journal should not be among the top two journals in Family Medicine. I am confident that increasing our impact is possible by engaging investigators who have yet to submit their work to Family Practice. I look forward to regular communications with our AEs to solicit ideas for improvement, selecting theme issues, increasing editorials and discourse about research priorities for primary care. Given the generous nature of family medicine investigators, I believe we can rapidly increase our reviewer pool which will be critical to providing the rapid peer review promised to authors. Last, I know this will be a valuable learning and professional development experience. This rare opportunity should help me stay current in this broad research field and make me a better investigator, mentor, and colleague.

Featured image created by Freepik .

The post Discussing family medicine: Q&A with Jeffrey Scherrer appeared first on OUPblog.

Diving into the OHR Archive

One of my favorite tasks as the OHR’s Social Media Coordinator is interviewing people for the blog. I get to talk to authors of recent articles from the OHR, oral historians using the power of conversation to create change, and a whole lot more. As a narcissistic millennial, however, I am now turning the spotlight inward, interviewing myself about the OHR’s latest virtual issue, released this week, on Oral History and Public History.

What can readers expect to find in this virtual issue?

This issue has everything: short articles about the professionalization of oral history; longer articles about memory in Saskatoon and public attention to Mashapaug; representations of the past in museums and public space; and journeys of communal discovery through Spanish-language music and intergenerational housing activism. The introduction is pretty neat, too. The threads that connect these articles together explore the interactions between oral historians, oral histories, and the public – whether that public be the residents of an ethnic enclave, visitors to a museum, or the people whose lives are recorded through a particular project.

Why should people look through a virtual issue, when a brand new issue of the OHR just came out?

In one of the first email interviews I conducted for the OHR blog, Linda Shopes encouraged oral historians to “slow down a bit and consider the urge to collect.” She was making a case about the direction of the field, but her concern about work simply gathering dust on archival shelves has stuck with me. In a world where new scholarship is continually being produced, older work can easily be ignored and fall by the wayside. But these articles are often immensely valuable in prompting questions for current research, and for thinking through the ways the field has changed or shifted. These virtual issues are a chance to slow down a bit, to dive deeply into the journal’s archive, and to see what conversations emerge over time.

You did this all by yourself, right?

Wow, such astute questions! As much as I would like to claim I did this all single-handedly, much of the credit (and none of the blame) goes to the OHR’s Editor in Chief Kathy Nasstrom and Managing Editor Troy Reeves. Troy and I worked through decades of scholarship to select a handful articles that could reflect, as accurately as possible, the major themes and concerns raised in the journal around the interactions between oral history and public history. We both fell in love with articles that didn’t make the final cut, and together we killed each other’s darlings. Kathy’s keen editing eye guided our selection process throughout and turned a rambling introduction into a polished piece of writing that makes it much clearer how each article adds to the issue. Troy and Kathy have graciously allowed me to take credit for the virtual issue (and I agreed, see: narcissism, above), but their fingerprints are all over it. The issue’s copyeditor, Elinor Maze, and our friends at Oxford University Press – especially marketing whiz Alex Fulton – helped to turn this virtual issue into a reality.

Do you have plans to do similar projects in the future?

I don’t, but the OHR does! Virtual issues are a great way to highlight older content, and the journal is eager to hear what other ideas for themes you, the readers, have. If you’d like to pitch a virtual issue, reach out at ohreview[at]gmail[dot]com.

You can explore the virtual issue here, and let us know what you think in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

The post Diving into the OHR Archive appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q&A with composer Malcolm Archer

Malcolm Archer’s career as a church musician has taken him to posts at Norwich, Bristol, Wells Cathedrals, and St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. He is the current Director of Chapel Music at Winchester College, where he is responsible for conducting the Chapel Choir and teaching the organ. As a composer, Malcolm has published many works; his pieces are widely performed, recorded, and broadcasted, and are greatly enjoyed for their approachable nature and singability. We spoke with Malcolm about his writing, his inspiration, and his career ambitions besides being a composer.

What does a typical day in your life look like?

There is no such thing as a typical day, as every day is a bit different with different things to achieve, but during term time my days will consist of teaching composition and organ at Winchester College and taking rehearsals with the Winchester College Quiristers and Chapel Choir. The choir sings four services in the College Chapel each week, plus a wide range of concerts, recordings, broadcasts and tours, so the work is pretty full on. I compose when I can squeeze it in, but of course the holidays free up a lot more time for composition.

What is the most difficult piece you’ve ever written and why?

A one act opera called George and the Dragon. It was commissioned by Brockham Choral Society, and is one hour in length and features SATB choir, childrens’ choir, five soloists and chamber orchestra. It was challenging to compose because I needed to keep the children’s music and choral sections relatively straight forward, whilst providing more challenging music for the soloists and orchestra. Working with a librettist has its challenges, since there has to be flexibility in both directions about what will work musically and vice versa. It was a very successful venture and the work has received several performances since its premiere. Its nearest neighbour is probably Britten’s Noyes Fludde.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments.

Here are three: when my choir sang Bach’s motet ‘Komm, Jesu, komm’ by Bach’s grave in St. Thomas, Leipzig, and the Leipzig musicians present were full of admiration for our performance; when my daughter sang her first solo in the choir at Salisbury Cathedral; and when one of my Quiristers won the BBC Chorister of the Year competition in 2015.

Michael Archer in action. Used with permission.

Michael Archer in action. Used with permission.What is your inspiration/what motivates you to compose?

Often sheer panic because there is a deadline looming! I guess I have always enjoyed composing, and much of what I do stems from improvisation, either at the piano or organ, depending on the medium. A really good text is often the spark I need for choral music. I used to get hang ups about writing in an accessible and fairly traditional way, instead of being more ‘avant garde’, but that is the case no longer. Accessibility is the key to regular performance. I try to keep my music harmonically and melodically interesting and I want people to perform it, but if they don’t like it, that is up to them. Luckily, many people seem to quite like my music.

Which of your pieces holds the most significance to you?

Probably my ‘Requiem Mass’, composed in 1993. It was heard at the funerals of both of my parents. I am also very fond of my ‘Vespers’, a new work, 30 minutes in duration, which was performed by the Farrant Singers in 2017.

What or who has influenced you the most in your life as a composer?

This is a difficult one. I have had so many influences, but I will always be indebted to my composition teachers: Herbert Sumsion, Bernard Stevens, and Alan Ridout. I also think that Finzi and Britten have been huge influences on my style; Britten is a composer I would have been interested to meet and talk to about music. I think his operas were a driving force in the development of opera during the 20th century.

What might you have been if you weren’t a composer?

I would always have done something to do with music. I have been lucky in that my career has allowed me to not only compose, but also to conduct choirs and orchestras, and to give organ recitals. I can’t imagine a career in anything other than music, though I have always loved classic cars, so perhaps I would have bought and sold those!

Is there an instrument you wish you had learnt to play?

Actually, I have always wanted to learn the cello, and have recently started taking some lessons and bought an instrument. I think that the cello is wonderful and probably the closest instrument to the human voice. I also think it is very good to learn a new instrument at my stage in my career, since it reminds me of the struggles that youngsters can experience in learning, and so it helps me to be more patient and understanding when teaching.

How has your music changed throughout your career?

I think my music has become much more harmonically interesting, and I think I have become gradually more adept at setting words to music in a convincing way. I have always admired Britten, Finzi, and Vaughan Williams for their ability to set words. One has to get right to the heart of the text and into the mind of the poet, and then convey that you’ve done that in the music by showing an understanding of the natural rhythm of words, and how they will work in a musical setting by getting stresses in the right places, and so on. I have learnt that all of that is vital if it is to be a successful piece.

Which composer, dead or alive, would you most like to meet?

Mozart. His music is so perfectly conceived, yet that seems to have been at odds with his personality. I find that juxtaposition absolutely fascinating.

Featured image credit: St Martin in the Bullring, Birmingham, United Kingdom by Michael D Beckwith. Public domain via unsplash .

The post A Q&A with composer Malcolm Archer appeared first on OUPblog.

September 14, 2017

Philosopher of the month: Mary Wollstonecraft [infographic]

This September, the OUP Philosophy team honors Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) as their Philosopher of the Month. Wollstonecraft was a novelist, a moral and political philosopher, an Enlightenment thinker and a key figure in the British republican milieu. She is often considered the foremother of western feminism, best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), which was written during the period of great social and political upheavals towards the end of the eighteenth century. This seminal work contains her reflections on the conditions of women and expounds powerful arguments for gender equality.

Wollstonecraft was born in London, Spitalfields, to a large family, the second eldest of the seven children. Although she did not receive a proper education, she was a prolific writer whose work included fiction, translating and reviewing a range of genres including essays, poetry, fiction, travel narratives, educational treatises and sermons. She engaged with the works of her contemporaries such as Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, Catherine McCauley, David Hume and Adam Smith, Madam de Stael, Emmanuel Swedenborg, Rousseau, Leibniz, Kant and their circles, and so became acquainted with British, French and German Enlightenment, which informed her political writings. She participated in political debates, and went to Paris during the Terrors to witness the trial and execution of the French king, documenting the effects of the Revolution.

Wollstonecraft‘s first publication was a conduct book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters: With Reflections on Female Conduct in the More Important Duties of Life (1787), dealing with the education of young girls. The book revealed strong influence from John Locke’s writing on the concept of morality and the need to instill it in children at an early age. Her anthology compilation The Female Reader (1789) is similarly moralistic in nature and contained excerpts from the Bible, Shakespeare and other eighteenth-century writers.

In her extraordinarily powerful work, A Vindication of The Rights of Woman (1792), Wollstonecraft found faults with the present state of female education. She upbraided writers such as Rousseau, Dr. Gregory, Lord Chesterfield, legislators and educators of her day for their roles in promulgating false and weak ideals of femininity, to which women have conformed. She was critical of the culture of luxury and materialism and the aristocracy who have reinforced these, and of Rousseau for his character of Sophie in Emile. Wollstonecraft argues that it is only through cultivating understanding and developing reason that women can become rational and independent beings.

For more on Wollstonecraft‘s life and work, read our infographic below:

Featured image: London Bridge. Public domain via

Pixabay.

Featured image: London Bridge. Public domain via

Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of the month: Mary Wollstonecraft [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

The three principles of democracy [excerpt]

Whether or not true democracy can ever be achieved remains uncertain. Historian James T. Kloppenberg argues that while democracy can be defined as an ethical ideal, the practical definition of democracy is too contentious to be adopted as a political system. The following shortened excerpt from Toward Democracy analyzes three contested principles of democracy: popular sovereignty, autonomy, and equality.

At the heart of debates about democracy are three contested principles, popular sovereignty, autonomy, and equality; and three related, but less visible, underlying premises, deliberation, pluralism, and reciprocity. The persistent struggles over these principles and premises help explain the tangled history of democracy in practice as well as theory.

To start with the first of the three principles, popular sovereignty holds that the will of the people is the sole source of legitimate authority. Although apparently unambiguous, its precise meaning has always been the central issue in debates about democracy. Champions of monarchical or aristocratic rather than strictly popular government have insisted that the people can legitimately choose to—and should—place themselves under the authority of a single person or a group of qualified individuals. Even partisans of democracy have expressed misgivings about the people’s capacity to exercise judgment. Thomas Jefferson, by popular reckoning among the most passionately democratic of eighteenth-century thinkers, became increasingly ambivalent about those who considered him their champion. In a letter written in 1820, the seventy-seven-year-old Jefferson identified this perennial problem: “I know of no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves,” he wrote in an apparently unqualified endorsement of popular rule. “If we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to enlighten their discretion.” Despite his genuine preference for democracy over monarchy or aristocracy, Jefferson did not identify the “we” charged with enlightening the people’s discretion or explain what justification “we” have for presuming to instruct them. That problem has dogged even the most ardent champions of democracy, who have been forced by abundant evidence to admit, as Jefferson himself did in the wake of the French Revolution, that the people are capable of horrible excesses. Ever since Plato’s Socrates likened statesmen to doctors and politicians to chefs—the former prescribe what is good for you even if it tastes terrible, the latter merely ask what tastes good—political thinkers have acknowledged the need to “enlighten” the people or to train (or restrain) their appetites. The principle of popular sovereignty itself, which assumes that the people are the source of authority and possess the potential to exercise good judgment, has been understood to be consistent with multiple forms of government.

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Charles Wilson Peale, circa 1791. Courtesy of the Independence National Historical Park. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Charles Wilson Peale, circa 1791. Courtesy of the Independence National Historical Park. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Autonomy is the second principle of democracy. One of the principal arguments of this study is the centrality of the idea of autonomy in contrast to the impoverished conceptions of freedom that dominate contemporary scholarly and popular debate. The etymological roots of “autonomy” stretch back to the Greek words for “self” and “rule” or “law.” “Autonomy” thus means self-rule. An autonomous individual exercises control over his or her own life by developing a self that is sufficiently mature to make decisions according to rules or laws chosen for good reasons. Autonomous individuals are in control of themselves, which means first that they are sovereign masters of their wills and second that they are not dependent on the wills (or whims) of others. Recent political theorists who have distinguished between “positive” and “negative” freedom, between the freedom to do something and the freedom from constraint, depart from the discourse of earlier democratic theorists, who understood that autonomy means self-rule in both the positive and negative senses: it requires a self both psychologically and ethically, as well as economically and socially, capable of deliberate action; and it requires the absence of control over individuals by other individuals and by the state. Autonomy has meaning only if individuals are understood as beings who act on the basis of consciously chosen goals developed in the framework of community standards and traditions. Thus in democratic discourse the idea of autonomy, like that of popular sovereignty, must be balanced against other ideas, in this case the dual awareness that constraints circumscribe individual choices and that the choices of the mature self must be weighed against the demands of the community.

Equality is the third contested principle of democracy. The conflict arises not only from the familiar opposition between the values of equality and individual autonomy but also from the inescapable tensions within the concept of equality itself. The familiar distinction between equality of opportunity and equality of result again obscures the deeper problem, because equal opportunity is not possible in conditions of extreme inequality. There is nevertheless an inevitable contradiction between the principle of equality and the democratic commitment to majority rule. Imagine a simple community with three voters. Two of them decide that the third should become their slave, and they justify their decision by the principle of majority rule. When the third invokes the principles of autonomy and equality in self-defense—as oppressed minorities have often done, sometimes successfully—that strategy counter-poses principles equally central to democracy to the principle of majority rule.

The discourse of democracy, like the institutional frameworks of different democratic cultures, is complex and multilayered. It requires the careful weighing of different values rather than the passionate defense of one alone. As its emergence over the centuries shows, democracy is best understood as a way of life, not simply a set of political institutions. The internal tensions between the principle of popular sovereignty and the principles of autonomy and equality make the notion of a smooth-running, conflict-free democracy a contradiction in terms; history provides no examples of a placid democracy. Inherent in democracy, even when conceived of as an ethical ideal and a way of life, are the inevitable disagreements, and the victories, defeats, and compromises, that are inseparable from the commitment to allowing people to pursue their own ideals and refusing to specify in advance which of their different, and perhaps even incompatible, conceptions will triumph.

Featured image credit: “vote-word-letters-scrabble” by Wokandapix. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The three principles of democracy [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Can narcolepsy research help solve one of the greatest medical mysteries of the 20th century?

In late 1916, while the world was entrenched in the Great War, two physicians on opposing sides of the conflict started to encounter patients who presented with bizarre neurological signs. Most notably, the patients experienced profound lethargy, and would sleep for abnormally long periods of time. One of the physicians, Constantin von Economo, was at the Psychiatric-Neurological Clinic at the University of Vienna. The other, René Cruchet, was a French physician in a military hospital for neuropsychiatric disorders. Both physicians were perplexed by the strange constellation of neurological signs and symptoms they observed in their patients, but because of their positions on opposing sides of the war, there was no way either of them could have known that these were not isolated cases, but the beginning of a worldwide epidemic that would claim over a million lives over the next decade, and leave many survivors permanently disabled.

Over 100 years later, the cause of encephalitis is still unknown. A recent article by Hoffman and Vilensky reviewed the previous and current hypotheses regarding the aetiology of encephalitis lethargica. Some of the most promising research into the possible cause of this bizarre disease comes from studies of narcolepsy. Like encephalitis lethargica, narcolepsy causes excessive sleepiness, often accompanied by paralysis or cataplexy. Narcolepsy was a recognized condition in 1916, and when von Economo encountered his first encephalitis lethargica patients, he immediately recognized the similarities between the two disorders. By examining the brains of encephalitis lethargica victims, von Economo was the first to correctly associate the hypothalamus with sleep regulation. Brains from patients who experienced pathological sleepiness consistently exhibited lesions in the posterior hypothalamus. Conversely, patients who experienced insomnia had brain lesions in the preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus, an area now known as the “sleep center.”

So how can narcolepsy research help to answer the question that has been plaguing scientists for a century? It turns out that encephalitis lethargica and narcolepsy have more in common than just sleepiness. Both have a complex, yet undeniable relationship with the flu. Encephalitis lethargica appeared around the same time as the Spanish flu epidemic, and most encephalitis lethargica patients initially presented with influenza-like symptoms, including fever, fatigue, and pharyngitis. Although a causative relationship has never been proven, there appears to be an epidemiological connection between influenza and encephalitis lethargica. Similarly, many European countries reported an increase in narcolepsy cases following influenza vaccination or infection with influenza during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

It turns out that encephalitis lethargica and narcolepsy have more in common than just sleepiness.

The exact cause of narcolepsy is unclear, but it is associated with lower levels of hypocretin in the cerebrospinal fluid. Hypocretin (also known as orexin) is a neuropeptide produced in the hypothalamus that regulates wakefulness and appetite. Most narcoleptics have a reduced number of hypocretin-producing neurons in the hypothalamus. While the cause of neuronal loss is not entirely clear, it has been hypothesized that an autoimmune mechanism may be to blame. Vaccine-associated narcolepsy, appears to be the result of a cross-reaction between hypocretin receptor 2 antibodies and a fragment of influenza protein used to create the vaccine. Individuals who develop narcolepsy following flu vaccination may already have a genetic predisposition for narcolepsy, coupled with an overactive immune system that is triggered by the vaccine, leading to the development of narcolepsy.

Von Economo hypothesized that infection with influenza might predispose a person to infection with encephalitis lethargica by increasing the permeability of the mucous membranes. The concept of autoimmunity was not discovered until the 1950s. Since then, a few hypotheses have pointed to an autoimmune mechanism as the cause of encephalitis lethargica. A 2004 study by Dale and colleagues suggested that encephalitis lethargica was a paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiaric disorder associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) disease. The same investigators later proposed that it was caused by autoimmunity against NMDA receptors.

Current research on the aetiology of encephalitis lethargica is severely limited by the scarcity and poor quality of existing specimens from the epidemic period, and the rarity of new cases. Barring another epidemic, we might never learn the cause of this mysterious illness, and why it essentially disappeared by the late 1920s. However, given the similarities between the two illnesses, ongoing research on narcolepsy could provide clues to help unravel what has been called the greatest medical mystery of the 20th century.

Featured image credit: Neurons by geralt. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Can narcolepsy research help solve one of the greatest medical mysteries of the 20th century? appeared first on OUPblog.

A mission to Saturn and its discoveries

With its beautiful rings (280,000 km across), impressive size (120,000 km diameter at the equator), and extensive number of moons (more than 60), Saturn has always been fascinating. But, because it’s so far away (ten times farther from the Sun than we are) it wasn’t always a realistic target for observation and experimentation. The first attempt to reach Saturn was in 1973, when NASA sent Pioneer 11 on its way. It arrived six years later, having navigated the dangerous asteroid-belt that lies between us and Saturn, but with only basic instrumentation on board it wasn’t able to gather much scientific data.

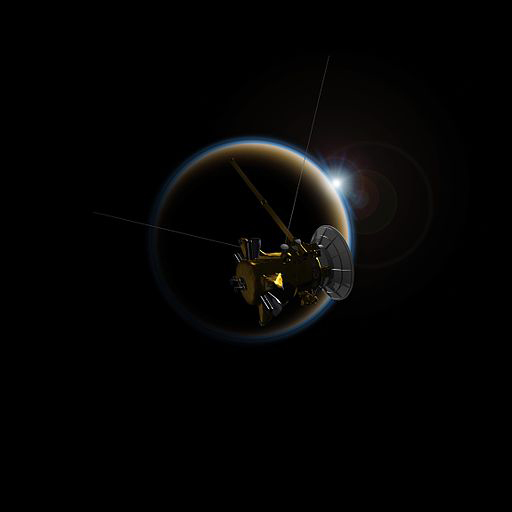

A larger spacecraft with better instruments was then sent on the same journey: Voyager. This did a fast fly-by in November 1980, so only gave us a glimpse of Saturn, its rings, and its moons. Then, 17 years later, in October 1997, a much more powerful mission was launched: Cassini–Huygens. Cassini was the NASA-developed Saturn orbiter, and Huygens was the European-built probe that sat on-board, which would eventually descend on to the surface of Saturn’s biggest moon, Titan.

Cassini will come to an end on 15th September 2017, when it makes its final approach to Saturn, diving in to the atmosphere (sending data as it goes), and finally burning up and disintegrating like a meteor. To mark this occasion we have brought together a selection of the discoveries the mission has made over the years, in a reading list below.

‘Cassini Observes Sunsets on Titan (Artist’s Rendering)’ by NASA/JPL-Caltech. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Cassini Observes Sunsets on Titan (Artist’s Rendering)’ by NASA/JPL-Caltech. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.An overview of the mission

“Operation Saturn” in Exploring the Planets: A Memoir by Fred Taylor

From the early attempts to explore Saturn and its moons to the Cassini–Huygens mission, there have been trials and tribulations along the way. The Cassini–Huygens mission was not only challenging, but expensive, so it was clear international collaboration (and sharing of costs) was essential, as was maintaining political support for the project.

Saturn’s magnetosphere

“Big Planets, Dwarf Planets, and Small Bodies” in Mankind Beyond Earth: The History, Science, and Future of Human Space Exploration by Claude Piantadosi

The magnetosphere of a planet is the volume of space that surrounds it, within which there are dominating magnetic fields and radiation belts. The first space missions that went to Saturn (Pioneer 11 and Voyager) helped scientists begin to understand Saturn’s magnetosphere, but the Cassini mission has dramatically enriched our understanding of these. For example it discovered that Saturn has two belts (the main and the new), which are interrupted by its rings.

Titan’s atmosphere

“Planetary Evolution and Comparative Climatology” in Radiation and Climate by Ilias Vardavas and Frederic Taylor

Titan has a number of Earth-like qualities and is the only (natural) satellite in our solar system that has a dense atmosphere. The Cassini mission has given us answers to a lot of the outstanding questions that we had about this atmosphere – showing it to be similar to our own, with temperatures and pressures at Titan’s surface meaning that methane can condense to a point where it creates clouds, and falls as rain.

‘Successful Flight Through Enceladus Plume’ by NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Successful Flight Through Enceladus Plume’ by NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Enceladus’s jets of water

“Genesis 2.0? SETI and Biology” in Science, Religion, and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence by David Wilkinson

Are we alone? Are there other life forms out there, in the Solar System? A case for possible (primitive) life was discovered by the Cassini mission, when it did a fly-by of Enceladus (another moon of Saturn) and discovered jets of water vapour shooting out into space. This means that there are reservoirs of water under the moon’s icy surface, with further analysis showing simple organic molecules within a salty ocean.

Striking visuals

“Epilogue, 2001–2004” in Into the Black: JPL and the American Space Program, 1976-2004 by Peter J. Westwick

The Cassini mission has provided some incredibly close-up and striking images of Saturn and its moons, with a camera that was five times the resolution of the one on Voyager (plus a radar to see through Titan’s atmosphere). There are fascinating images of geysers shooting from Enceladus’s south pole, beautiful images of Saturn’s rings (including one with Saturn’s shadow falling on them), and a zoomed-in view of Epimetheus (another of Saturn’s moons).

Featured image credit: ‘The Day the Earth Smiled’ by NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post A mission to Saturn and its discoveries appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers