Oxford University Press's Blog, page 322

September 21, 2017

America’s darkest hour: a timeline of the My Lai Massacre

On the morning of 16 March 1968, soldiers from three platoons of Charlie Company entered a group of hamlets located in the Son Tinh district of South Vietnam on a search-and-destroy mission. Although no Viet Cong were present, the GIs proceeded to murder more than five hundred unarmed villagers. Referencing My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness, we’ve put together a timeline that marks the events following the mass killing now known as the My Lai Massacre.

Featured image credit: “Monument of the My Lai Massacre” by -JvL-. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post America’s darkest hour: a timeline of the My Lai Massacre appeared first on OUPblog.

Seven reasons to get your memory evaluated

A question that I am often asked by family members, friends, and even by other physicians and nurses that I work with, is “Should I get my memory evaluated?” Partly, the question is asked because they have noticed memory problems, and are struggling to sort out whether theses lapses are an inevitable part of normal aging versus the start of something more ominous, such as Alzheimer’s disease. But another part of the question—particularly when asked by healthcare professionals—goes unspoken: “We can’t really do anything about memory problems, anyways, right? So why should we bother getting our memory evaluated?”

This latter sentiment was most recently voiced by a physician who criticized me for diagnosing and treating her patient. “Wouldn’t it be better to not tell him?” she said. “Wouldn’t it be better not to make him worried and depressed about having Alzheimer’s disease?”

One in ten people (5.5 million) over the age of 65 have Alzheimer’s dementia and about 200,000 people younger than 65 have early onset Alzheimer’s. I’ve been thinking about this statistic and the conversation with my colleague for the last month, and here is my answer. Or, to be more precise, here are seven reasons as to why anyone should bother with a memory evaluation.

Jeffrey Burns, M.D., director of the University of Kansas Heartland Institute for Clinical and Translational Research’s Participant and Clinical Interactions Resources Program, and its Clinical and Translational Science Unit, and director of the Alzheimer’s and Memory Program, monitors Howard Kemper, a participant in the Brain Aging Project. Image by Donna Peck for the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Jeffrey Burns, M.D., director of the University of Kansas Heartland Institute for Clinical and Translational Research’s Participant and Clinical Interactions Resources Program, and its Clinical and Translational Science Unit, and director of the Alzheimer’s and Memory Program, monitors Howard Kemper, a participant in the Brain Aging Project. Image by Donna Peck for the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Knowledge is power. It is a fact of life that changes to memory will occur with age. Those that occur with healthy aging are different from those due to Alzheimer’s and other dementias. Rather than worrying about memory loss, it is much better to sort out what is the cause of your memory problems. I can honestly say that almost every patient I see comes away content to know where their memory problems are coming from—even if Alzheimer’s disease is the answer.

Current treatments for memory loss do actually work. The current treatments for Alzheimer’s disease have been shown to turn the clock back on the memory loss by about six to twelve months. This means that you generally see an improvement in your thinking and memory. And they don’t stop working—even as the Alzheimer’s disease progress and thinking and memory deteriorate over time, your memory is almost always better using currently available medications than it would be without them.

Future treatments may significantly slow down Alzheimer’s disease. Over the past ten years, our improved understanding of Alzheimer’s disease has generated new potential treatments that may further improve memory, stop the formation of the amyloid plaques that damage brain cells, or even remove those plaques altogether. These new medications are available now in clinical trials.

Treatments work best when started early. Many studies have shown that the magnitude of improvement is larger when the medications are started early, in the mild stage of disease, rather than waiting until the moderate or severe stages. Additionally, most clinical trials of new medications are only open to those with mild disease.

Physical exercise and proper diet can help. Everyone knows that exercise is good for you, but few people realize how important it is for their memory and brain health. In addition to reducing the risk of strokes, aerobic exercise improves sleep, mood, and memory—it can even promote the growth of new cells in the hippocampus, the part of the brain that forms new memories. In addition, many studies have found that the Mediterranean diet can reduce memory loss.

Strategies and memory aids can help everyone. Whether memory loss is due to normal aging or the start of a brain disease such as Alzheimer’s, everyone can improve their memory using strategies and external memory aids, such as mnemonics, notebooks, calendars, pillboxes, and smartphones.

Participating in memory research or advocacy work can help future generations. Be proactive. Confront your memory problems and find out what is causing them.

Empowered with this knowledge, you will be ready to participate in research, advocacy work, or another endeavor that can help those around you and the next generation.

Featured Image Credit: Walk to End Alzheimer’s in Bourbonnais Saturday, September 29, 2012 by Alzheimer’s Association Illinois Chapter. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Seven reasons to get your memory evaluated appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q&A with oncologist Pamela Goodwin

Like many oncologists, Dr. Pamela Goodwin first developed an interest in oncology following seeing a family member affected by cancer. Today, she leads JNCI Cancer Spectrum as Editor-in-Chief, publishing cancer research in an array of topics. Recently, we interviewed Dr. Goodwin, who shared her thoughts about the journal, the field of oncology, and her visions for the future.

How did you get involved in the launch of the new open access journal, JNCI Cancer Spectrum ?

The JNCI Publisher and Editorial group reached out to me during the summer of 2016 about this new journal – I had been an Associate Editor at Journal of Clinical Oncology for almost ten years and was looking for new challenges. The opportunity to launch a new journal was exciting, and the close association with the well-established, respected, and impactful JNCI was a major draw. We launched in late spring of this year and will be publishing our first issue in September – it has been a whirlwind experience that I have enjoyed enormously.

What makes JNCI CS unique?

We will use an Online, Open Access publication model, allowing the scientific community immediate and unrestricted access to our manuscripts. Although we will publish papers that cover a range of research similar to that published in JNCI, we are encouraging submission of hypothesis generating and hypothesis confirming papers, as well as expert opinion reviews, meta-analyses, and critical appraisals. We will publish scholarly discussions of research hypotheses and research direction, and hope to become a home for commentaries of this type. Over time I anticipate we will develop our own “brand” that is complementary to JNCI.

How do you decide which articles should be published in JNCI Cancer Spectrum ?

The major criteria will be quality and potential for scientific impact. We see JNCI CS as evolving into a high impact journal that will complement JNCI, our sister journal that currently receives more high quality manuscripts than it can publish. Our team of Associate and Consulting Editors, along with JNCI/JNCI CS staff, will carefully evaluate submitted manuscripts for scientific rigor and interest; we will engage peer reviewers (many of whom will be members of the Editorial Board we share with JNCI) to evaluate manuscripts that pass initial editorial screening to ensure that the manuscripts we publish are of high quality and are of interest to the cancer community.

Dr. Pamela Goodwin. Used with permission.

Dr. Pamela Goodwin. Used with permission.How did you become involved in the field of journal editing?

I have been a medical oncologist and clinical cancer researcher for almost 30 years, trained in clinical epidemiology with a focus on the role of lifestyle, notably obesity, in breast cancer. After publishing dozens of papers, and reviewing many more, I had developed a great appreciation of the peer review process, but felt I could make an important contribution to enhance methodologic rigor in the area of clinical cancer research by becoming involved in editing. Clinical trials methodology was already strong, but improvements were needed in other areas. I also wanted to elevate the status of lifestyle, survivorship, and quality of life research in the cancer publishing world. To that end, I joined JCO as an Associate Editor and led several Special Issues of JCO and published multiple editorials focusing on research direction and quality. With my team of Associate Editors, I intend to continue these initiatives at JNCI CS.

How can I get involved in JNCI Cancer Spectrum and in journal editing in general?

I believe that good editors have a broad understanding of cancer research in their field, a strong track record of conducting impactful research, and considerable experience in peer-review, particularly peer review of scientific manuscripts. Thus, a successful independent research career and a demonstrated willingness to review papers in a thorough, balanced, and timely fashion would be key to greater involvement in JNCI CS. We regularly update our reviewer database to include researchers who express interest in reviewing for us, and will invite outstanding reviewers to join our Editorial Board to become more involved in the Editorial process. Individuals who are interested in becoming involved at JNCI CS should contact me.

What led you to the field of oncology? Why did you choose to focus on breast cancer?

Like many oncologists, my initial interest in oncology arose from seeing cancer affect a family member. Once I began my training I was struck by the adverse impact that cancer, especially breast cancer, had on my patients and their families. Before organized screening began in the 1990s, most breast cancer patients presented with node positive disease and available adjuvant therapies had limited effectiveness – as a result, many of my patients died of their breast cancer. It has been wonderful to see the tremendous improvements in outcomes over the past 25 years – in Canada, where I practice, population based deaths from breast cancer are at their lowest levels since data began to be collected 60-70 years ago. My own research has focused on the relationship between a woman and her breast cancer – studying factors such as obesity and vitamin D, examining their associations with breast cancer outcomes as well as delving into the underlying biology of host effects in breast cancer. This field has “come of age” during the past decade, with ongoing randomized trials targeting lifestyle and biologic intermediaries of the breast cancer-host factor relationship.

What developments would you like to see in your field of study?

We have made great strides in cancer research, but there is much more to do. Because cancer is not a single disease there will be no single solution. We need to continue to work on multiple agendas to understand cancer causes, biology, prevention, and treatment. We need to embrace advances in understanding the biologic basis of cancer, and to continue to translate that understanding into effective treatment. Much of the clinical research will involve large scale trials that will be conducted by co-operative groups and pharmaceutical companies – but we also need to be open to novel ideas and approaches, some of which will come from unexpected sources. Prevention should continue to be a major focus; it will require rigorous and often costly research. One major challenge in some cancers, including breast, is de-escalation of current treatment so that treatment is given only to those who will benefit from it. Another is the need to match targeted treatments to biologically defined subsets of cancers, leading to challenges in clinic trial accrual when these subsets are small, and to economic challenges when effective, but expensive, treatments are identified. Finally, for many patients who live with cancer, and the sequelae of cancer treatment, optimization of quality of life will be needed to reduce overall disease burden.

Featured image credit: Workspace by Sabri Tuzcu. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post A Q&A with oncologist Pamela Goodwin appeared first on OUPblog.

September 20, 2017

Trashing Thurse, an international giant

While working on my previous post (“What do we call our children?”), which, among several other words, featured imp, I realized how often I had discussed various unclean spirits in this blog. There was once an entire series titled “Etymological Devilry.” Over the years, I have dealt with Old Nick, grimalkin, gremlin, bogey, goblin, and ragamuffin, and in my recent book In Prayer and Laughter… there is a whole chapter on the creatures whose names begin with rag-, but the plate is still full.

In 1895, Charles P. G. Scott brought out an article on the Devil and his imps (Transactions of the American Philological Association [TAPA] 26, 79-146). It is a most interesting work; the whole of it is now available online. The regular readers of this blog will remember that I have a soft spot for two woefully underappreciated etymologists: Frank Chance and Charles P. G. Scott. The obscurity in which they remain is particularly annoying because the English-speaking world has produced very (and I repeat: very) few truly great students of word origins. Two names shine bright: Walter W. Skeat and James A. H. Murray of OED fame. In the second tier, we find Earnest Weekley, who was resourceful but not great. Some recognition is due Hensleigh Wedgwood, and out of respect for our distant predecessors we should mention John Minsheu, Stephen Skinner, and Franciscus Junius, the younger. In the polite jargon of academia, today their contributions are only of historical interest.

Plodding through this semidry desert, we can hardly afford to ignore real talent. And yet this is exactly what has happened. References to Frank Chance, the tireless contributor to Notes and Queries, are rare (this is an understatement), and the name of Charles P. G. Scott, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary, means nothing to 99% of modern philologists (though Skeat knew and appreciated the opinions of both). We often hear that history will give all people their due. This is wishful thinking: history is too busy to take notice of all of us, and it seldom rejects bribes.

What follows has been inspired by Scott’s article. I should add that Scott was an ardent supporter of Spelling Reform, and his articles in TAPA reflected his ideas of how words should be spelled. I’d like to reproduce one of his statements, but will re-spell everything according to the still existing conservative norm and only italicize the words I “corrected”: “I might have been appalled by the troop of dark and yelling demons and bogles, or by the task of explaining their denomination; but it is well known that in the still air of etymology no passions, either of fear or hate or joy, can exist, and that etymologists, indeed, consider it their duty to feel no emotions, unless it be gratification at finding their work improved and their errors rectified, by another [spelled as two words] and a better etymologist. This sometimes happens.”

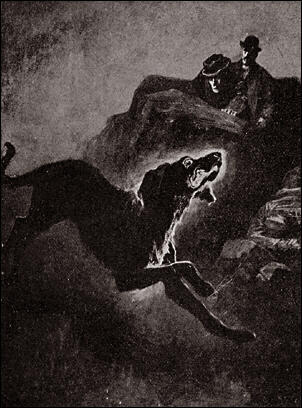

Here is a dog (a famous hound) with pretercanine eyes.

Here is a dog (a famous hound) with pretercanine eyes.Many pages of Scott’s article are devoted to thurse. The OED features this word, even though today it is either regional or “antiquarian.” It was very well-known in Old English (þyrs; so in Beowulf) and Old High German (duris ~ thuris). Its reflexes (continuations) can be found all over the Scandinavian world and mean “giant; fool, etc.”: Old Icelandic þurs (or þuss); elsewhere, tuss, tusse, tosse, and so forth. In English dialects, thurse, in the form trash, among others, has been retained as the second elements of many compounds. One of them is guytrash “goblin; specter.” The word occurs in Jane Eyre. The idea that trash here is a variant of thurse is Scott’s, and it looks convincing. In Chapter 12 of Charlotte Brontë’s novel, the goblin is described so: “…a great dog, whose black and white color made him a distinct object against the trees. It was exactly one mask of Bessie’s Gytrash (sic)—a lion-like creature with long hair and a huge head; it passed me however, quietly enough, not staying to look up, with strange pretercanine eyes, in the face, as I half expected it would. The horse followed—a tall steed and on its back a rider….” After all, the figure turned out not to be G(u)ytrash, and the most frightening part of the description is the word pretercanine, most likely Bronte’s coinage on the analogy of preternatural (so “beyond what one could expect from a dog’s eyes”).

Caravaggio, ‘David with the head of Goliath’. Who’s afraid of a big bad thurse?

Caravaggio, ‘David with the head of Goliath’. Who’s afraid of a big bad thurse?The spirit (“spreit”) of Guy was well-known in the sixteenth century, and this guy is probably our familiar guy. Thus, the goblin was a guy-thurse, with both elements meaning approximately the same (a kind of tautological compound: see the post from 11 February 2009). Scott concludes: “The word guy, meaning ‘any strange looking individual’, an awkwardly dressed person, ‘a fright’, is regarded as an allusion to the effigy of Guy Fawkes, formerly carried about by boys on the fifth of November. I suppose this is true; but it may be that the fading ‘spreit of Gy’, the Gytrash, is also present in this use of guy.”

Guy Fawkes, the most famous guy of all.

Guy Fawkes, the most famous guy of all.Guytrash has relatives: Malkintrash “Moll goblin” (malkin is immediately recognizable from grimalkin); Hob Thurst, a hobgoblin, whose second element is identical with thurse, and a host of demons, specters, and goblins known under the names of thurse, thurst, thrust, thrush, thruss, and trash. Scott wrote his article before the appearance of Joseph Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary. There one can find many variants and examples of the names mentioned above.

The bird name thrush and the disease thrush (on the latter see the post from have nothing to do with that devilish cohort. Trash “junk” is harder to pinpoint. This word’s etymology is far from clear. Most likely, dialectal trash “hobgoblin” did not affect the meaning of trash “junk,” but one never knows, because that trash also seems to have reached the Standard from rural speech and has no obvious cognates. By contrast, thurse conquered many languages. Outside the Germanic group, we find its relatives in Celtic, as well as in Finnish and its neighbors, perhaps borrowed From Germanic. Its root has been sought in a verb meaning to “move with a lot of noise” (and indeed, words for giants often mean “noisy”) and in the root signifying “strong.”

In the remote past, words for “giant” were occasionally borrowed from people’s powerful and dangerous neighbors. In the Etruscan language, we find the ethnic name Turs. Were the people called Tursānoi by the Greeks the original “giants” of the Germanic-speaking people? Superstitions are local, but the words for feared creatures are often borrowed. Both Engl. giant and titan are of course Greek. Boogey ~ bogey and its nearest kin, as I have pointed out more than once, are “Eurasian”: they occur in the West and in the East. The most common word for “giant” in Old Icelandic was jötunn (related to Old Engl. eoten), and it too has been compared with an ethnic name (Etiones). On the other hand, Dutch droes “devil,” first recorded with the sense “giant, warrior,” resembles Old Icelandic draugr “specter; revenant,” and those nouns have been connected with the word for “deception (German Betrug, etc.)

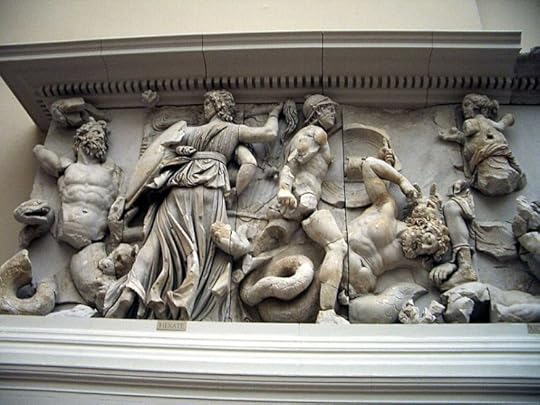

Titans are great, but they exist to be vanquished, in order to ward off chaos.

Titans are great, but they exist to be vanquished, in order to ward off chaos.Perhaps all those comparisons and conjectures are unprofitable guesswork, but, on the other hand, there may be some truth in them. Be that as it may, the part of the present essay’s title containing the adjective international is not unjustified. Despite my admiration for Charles Scott’s work, I respectfully disagree with his statement that in the still air of etymology no passions, either of fear or hate or joy can exist. When it comes to some offensive words, the hot air of etymological research begins to resemble what one can observe above a boiling cauldron. Opinions clash, reputations are created and ruined, and many a bubble bursts before our eyes with a deafening noise. Hot air indeed.

The post Trashing Thurse, an international giant appeared first on OUPblog.

Invasion: Edwardian Britain’s nightmare

Images of future war were a prominent feature of British popular culture in the half century before the First World War. Writers like H.G. Wells thrilled their readers with tales of an extra-terrestrial attack in his 1897 The War of the Worlds, and numerous others wrote of French, German, or Russian invasions of Britain. The genre was so pervasive that it moved a young P.G. Woodhouse to satirise it in his 1909 story The Swoop! Or, How Clarence Saved England. “England was not merely beneath the heel of the invader. It was beneath the heels of nine invaders,” he wrote, laconically observing, “there was barely standing-room.”

Historians have long been aware of the prevalence of British fears of invasion during this period. They have been interpreted widely: as a manifestation of concerns at the health and “efficiency” of the British race and Empire, an echo of the “Weary Titans” faltering steps into the twentieth century, and a means of stirring the British people to meet the rising threat of Germany, amongst others. What is far less clear is the relationship between these fears and official policy. Were they, as Niall Ferguson has observed, “completely divorced from strategic reality”?

The answer depends on what one considers strategic reality to be. We now know that neither the Germans nor the French formed any serious plans for the invasion of Britain between 1900 and 1914. However, this was not the impression held by many British strategists at the time. Indeed, by degrees, the decade before the outbreak of the First World War witnessed a collapse in the Royal Navy’s confidence in its ability to prevent an invasion of the British Isles. For a series of operational and infrastructural reasons, Britain’s naval leadership devoted more and more time, attention, and resources, to the increasingly urgent task of defending her eastern seaboard. Even as Admiral Sir John “Jacky” Fisher was encouraging an audience in London to “sleep quiet in your beds, and not to be disturbed by these bogeys — invasion and otherwise” in 1907, he was presiding over top-secret plans to use the Navy’s newest warships — including HMS Dreadnought — in an ambitious and risky plan to forestall a German landing. By the outbreak of War in 1914, one officer in the Admiralty planning section complained at the extent to which the need to safeguard the east coast was obliging the Navy to run risks with the British Fleet, lamenting “the very powerful and insidious reaction on our naval strategy” which the situation had produced.

This crisis in naval confidence was the product of the shifting balance of power and operational conditions in the North Sea, which made observing German movements extremely difficult. In an age before radar or effective aerial spotting, the “castles of steel” of the British Fleet were blind over the horizon — a fact which, it was felt, gave the Germans a chance at slipping out of port and across the North Sea undetected. Yet it was also the product of failings at the highest level of government.

Image credit: HMS Dreadnought, circa 1906-1907. Photo by U.S. Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: HMS Dreadnought, circa 1906-1907. Photo by U.S. Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Navy’s concerns were rendered acute by the government’s tacit support for the principle of dispatching all six divisions of the British regular army to Europe in the event of a German attack upon France. No decision was ever reached on this point before 1914 — a fact attested to by the confusion and debate on this issue which occurred after the outbreak of War. However, the Admiralty was well aware of the General Staff’s ambition to enlarge the expeditionary force, and to rely on second-line troops of the Territorial Force to repel any invaders who did make it past the Fleet at sea. The widespread lack of faith in the efficiency of these troops — “a mass of cotton wool instead of a quarter-inch plate” according to Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, — left the Navy feeling under the utmost pressure to adopt a defensive stance and to prevent any landing — no matter how small — at the expense of plans to use the Fleet in a more aggressive manner. As one official minuted with a sense of urgency in late-1913, “the Government … must be convinced by all arguments we can bring to bear on the subject that the main force of the Navy must be relieved from minor defensive operations on the coast.”

Yet the government was ill-prepared and disinclined to fulfill its role as a coordinator of British grand strategy. Between 1906 and 1914 it had let the activities of the two services drift apart and their plans conflict, forcing the Navy to adopt an overtly defensive stance and failing to strengthen the Army enough to allow it to play a meaningful role on the Continent. British strategy thus consisted of quasi-independent military and naval policies, and the government’s Committee of Imperial Defence was given insufficient authority to enforce a degree of coherence. The deep-seated inconsistencies this caused foreshadowed the inefficient and haphazard decision making process which characterised British strategy during the opening years of the War.

No foreign army set sail for British shores in 1914, but preparing to meet one exercised a crucial role in shaping how the nation prepared itself for War.

Featured image credit: The Lords of the Admiralty attending 1907 Naval Review. Foreground left is Admiral Sir John ‘Jacky’ Fisher. Photo from Queen Alexandra’s Christmas Gift Book, 1908. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Invasion: Edwardian Britain’s nightmare appeared first on OUPblog.

Tolkien trivia: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit”

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit” – the opening line of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit is among the most famous first lines in literature, and introduces readers to the most homely fantasy creatures ever invented: the Hobbits. Hobbits are a race of half-sized people, very similar to humans except for their hairy feet. They live in the lush countryside of The Shire, part of Tolkien’s imaginary Middle-Earth, also home to his famous works The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion.

In a letter, Tolkien once wrote “I am in fact a Hobbit” and he did indeed share many of their traits. Like a Hobbit, he loved gardening, good food, the comfort of familiar home terrain, and smoking a pipe. Both the Hobbit and his creator are beloved by many, and once a year, they are celebrated. Twenty-two September marks the shared birthday of the Hobbits Bilbo Baggins and his nephew Frodo, and has therefore been declared Hobbit Day. To extend the festivities, and because we all know Hobbits love a good party, a full week surrounding this date is feted as Tolkien Week. Celebrate yourself, by taking a look at some interesting facts on Tolkien and his works.

Tolkien had a very prominent circle of friends. The Inklings (as they called themselves) where a group of writers and scholars, who regularly met to discuss literature and critique each other’s work in the facilities of Magdalen College or The Eagle and Child, a local Oxford pub. Other prominent members were C. S. Lewis, creator of the Chronicles of Narnia and Charles Williams, writer and editor at Oxford University Press. The name was a clever pun, as Tolkien explained: “suggesting people with vague or half-informed intimations and ideas plus those who dabble in ink”.

As scholar and professor, Tolkien’s most influential work was his essay “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” (1936). His argument for the monsters as central defining features for the hero’s personal development and structure of the Old English epic poem has changed the way it is approached by scholars ever since.

Scholars argue these monsters have found their way into Tolkien’s own writing. The man-shaped Grendel and the greedy dragon resemble Bilbo Baggins’s adversaries in The Hobbit. We know them as Gollum and Smaug the dragon.

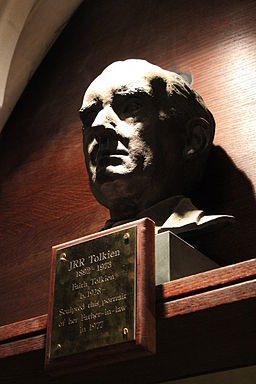

Image credit: “Bust of J.R.R. Tolkien in Exeter College, Oxford”. Picture by Julian Nitzsche. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “Bust of J.R.R. Tolkien in Exeter College, Oxford”. Picture by Julian Nitzsche. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Apart from Beowulf and other Anglo-Saxon and Norse stories, another source of inspiration surely came from Tolkien’s contemporary England. Tolkien compares the English (himself included) to the Hobbits, and the luscious countryside of the Shire is often seen to be inspired by rural England. Critics often compare Hobbiton with Sarehole near Birmingham, Tolkien’s childhood home.

Religious scholarship debates the extent to which Tolkien’s work can be read in a Christian context. Some argue against, citing the heavy influence of Norse and Germanic mythology. Others argue for it, citing parallels between Tolkien’s and biblical characters. The fight between the two Hobbits Sméagol and Déagol results from the former not being able to endure his friend finding the one ring. The fight ends fatally for Déagol and starts Sméagol’s transformation into the creature Gollum. It is understood to be a recasting of Cain and Abel in the Old Testament.

In Tolkien’s universe, the struggle between good and evil also is one between nature and technology. The dark lands of Mordor contain fortresses of steel and technology whereas the forces of good are generally living in accordance with nature. Forests in particular are the central force of nature and important locations for the narrative. The story’s impact on environmental issues became apparent when it developed a cult following among the Hippie community in the United States in the 1960s, who took Fangorn (Treebeard) as a symbol of their biocentrism. It even inspired late activist David McTaggart to found Greenpeace.

The film adaptations of The Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit were filmed in New Zealand. The immense success of the franchise, paired with clever marketing brought a surge in tourism to the country. Tolkien’s legacy not only impacts the country’s tourist industry but also its employment law. The Hobbit/Actors Equity dispute between the film makers of The Hobbit and the State led to an adjustment of employment law in favour of the industry to ensure filming of The Hobbit would be continued in the country.

Featured image credit: “House, Home” by StockSnap. Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Tolkien trivia: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit” appeared first on OUPblog.

Cultural shifts in protest groups

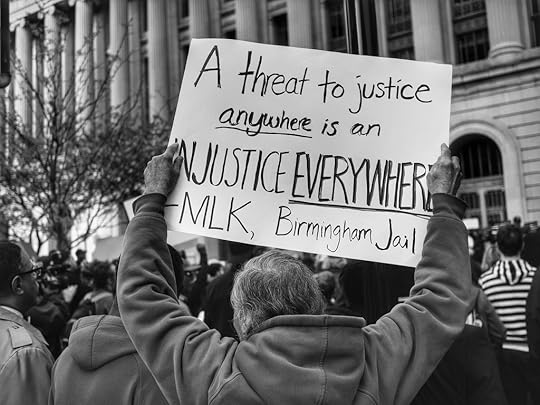

Protest and counterculture in America have evolved over time. From the era of civil rights to Black Lives Matter, gatherings of initially small groups growing to become powerful voices of revolution have changed the way we define contemporary cultural movements. In this excerpt from Assembly, authors Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri examine how some minority protest groups have adapted over time to be more inclusive in their organizational models without having a sole defined leader.

Those who lament the decline of leadership structures today often point, especially in the US context, to the history of black politics as counterexample. The successes of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s are credited to the wisdom and effectiveness of its leaders: most often a group of black, male preachers with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and with Martin Luther King Jr. at the head of the list. The same is true for the Black Power movement, with references to Malcolm X, Huey Newton, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), and others. But there is also a minor line in African American politics, most clearly developed in black feminist discourses, that runs counter to the traditional glorification of leaders. The “default deployment of charismatic leadership,” Erica Edwards writes, “as a political wish (that is, the lament that ‘we have no leaders’) and as narrative-explanatory mechanism (that is, the telling of the story of black politics as the story of black leadership) is as politically dangerous . . . as it is historically inaccurate.” She analyzes three primary modes of “violence of charismatic leadership”: its falsification of the past (silencing or eclipsing the effectiveness of other historical actors); its distortion of the movements themselves (creating authority structures that make democracy impossible); and its heteronormative masculinity, that is, the regulative ideal of gender and sexuality implicit in charismatic leadership. “The most damaging impact of the sanitized and oversimplified version of the civil rights story,” argues Marcia Chatelain, “is that it has convinced many people that single, charismatic male leaders are a prerequisite for social movements. This is simply untrue.” Once we look beyond the dominant histories we can see that forms of democratic participation have been proposed and tested throughout the modern movements of liberation, including in black America, and have today become the norm.

“Black Lives Matter” by 5chw4r7z. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Black Lives Matter” by 5chw4r7z. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Black Lives Matter (BLM), the coalition of powerful protest movements that has exploded across the United States since 2014 in response to repeated police violence, is a clear manifestation of how developed the immune system of the movements against leadership has become. BLM is often criticized for its failure to emulate the leadership structures and discipline of traditional black political institutions, but, as Frederick C. Harris explains, activists have made a conscious and cogent decision: “They are rejecting the charismatic leadership model that has dominated black politics for the past half century, and for good reason.” The centralized leadership preached by previous generations, they believe, is not only undemocratic but also ineffective. There are thus no charismatic leaders of BLM protests and no one who speaks for the movement. Instead a wide network of relatively anonymous facilitators, like DeRay Mckesson and Patrisse Cullors, make connections in the streets and on social media, and sometimes “choreograph” (to use Paolo Gerbaudo’s term) collective action. There are, of course, differences within the network. Some activists reject not only orderly centralized leadership but also explicit policy goals and the practices of “black respectability,” as Juliet Hooker says, opting instead for expressions of defiance and outrage. Others strive to combine horizontal organizational structures with policy demands, illustrated, for example, by the 2016 platform of the Movement for Black Lives. Activists in and around BLM, in other words, are testing new ways to combine democratic organization with political effectiveness.

The critique of traditional leadership structures among BLM activists overlaps strongly with their rejection of gender and sexuality hierarchies. The dominant organizational models of the past, Alicia Garza claims, keep “straight [cisgender] Black men in the front of the movement while our sisters, queer and trans, and disabled folk take up roles in the background or not at all.” In BLM, in contrast, women are recognized, especially by activists, to play central organizational roles. (The creation of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter by three women—Garza, Cullors, and Opal Tometi—is often cited as indicative.) The traditional assumptions regarding gender and sexuality qualifications for leadership, then, tend to obscure the forms of organization developed in the movement. “It isn’t a coincidence,” Marcia Chatelain maintains, “that a movement that brings together the talents of black women—many of them queer— for the purpose of liberation is considered leaderless, since black women have so often been rendered invisible.” The BLM movement is a field of experimentation of new organizational forms that gathers together (sometimes subterranean) democratic tendencies from the past. And like many contemporary movements it presents not so much a new organizational model as a symptom of a historical shift.

Featured Image: “It’s A Revolution” by Alan Levine. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post Cultural shifts in protest groups appeared first on OUPblog.

To be a great student, you need to be a great student of time management

You might be brilliant. An exceptional student. But if you can’t get your paper in on-time, revise ahead of the exam, or juggle a busy student & home life, then no-one will ever know how you brilliant you are. Time management is the skill that unlocks everything else. If you want to get more done you need to be a great student of time management because this is the key that can open every door.

Why Time Management Courses Don’t Work is a great book by Fergus O’Connell. Fergus shares with us that time is constant. 365.2 days and 52 weeks in a year, and seconds that just tick by. We cannot ‘manage time.’ The only thing we can do is to make better choices. And to make better choices we need a time management system. Be it a great or a poor system, you managed to get up, get dressed, get to a lecture, and juggle a million things in your life. You just don’t achieve all that you want to. Luckily there’s help….

‘I was writing that essay until 2 o’clock this morning’

Everyone procrastinates. Puts things off. It’s human to do so. If you want to get more done and more done fast, then recognising that you do put things off is an essential first step that you need to recognise and tackle. You can procrastinate on the former, not on the latter.

Procrastinating is a good thing. I’ll say again, ‘Procrastinating is a good thing.’ Sighs of relief all round. Here’s the rub – As long as you do it on the right things. Not organising a social with old friends at home isn’t essential (Though some will disagree). Not handing in a paper on time is essential.

One of the main reasons we procrastinate is because we don’t trust ourselves. Imagine you have a deadline of 2 weeks Tuesday to hand in an assignment. Your brain says that if you start it now you’ll get it done and then spend forever titivating. Spending time changing paragraphs, researching a bit more, finding new arguments, and so on. So, instead the genius of your brain subconsciously plans, schemes, and calculates that if you start it at 11am on Monday, you’ll have just enough time if you work at breakneck speed and half of the night to hand it at 9.01am on Tuesday. The brain is exceptional at doing this!

Book calendar page by Eric Rothermel. Public domain via Unsplash.

Book calendar page by Eric Rothermel. Public domain via Unsplash.The challenge is to recognise the schemer in you. Accept it, and set a deadline. If the assignment should take you around 11 hours, track your time and spend about 11 hours on the assignment. Beware that we always think we can get things done much quicker than we actually can, so add 50% to the time. Maybe 16.5 hours to get it done. Then allow 3 hours work per day, track it, and commit to finishing the assignment after the agreed number of hours. And no titivating afterwards. You will begin to trust your brain and it you. Next time an assignment comes around you can build on that trust until you and your brain trust each other enough to work in this more effective way.

‘The most successful people are the ones with the emptiest heads’

Most students carry their to do list in their heads. Everything they need to do is there. Not in a system. Imagine the weight of carrying all those tasks around every day. Like the RAM of a computer, ours is limited, and if there’s too much in it, tasks will either be lost, or slow us down, or worse still, make us sick. Using your RAM for solving problems is a much better use of its power than to just remember stuff. Especially when there is so much technology around to help us, to remind us, and to help keep us on track.

One of the key principles of an effective time management system is to use it to get stuff out of your head and into a system that you trust. It doesn’t have to be fancy. For many successful entrepreneurs, a pen and a pad is all they need. The time management guru’s call these capture points. Having the right amount of capture points that wherever you are, whenever you are, you can get stuff out of your head and into a system. You might be walking across campus and something pops into your head – You might use Siri to put it into notes, or you are in a lecture and you use OneNote to capture the notes. The next step is to ensure that you empty your capture points frequently. This 1-minute video will help you, or you can take ‘The 7-week Time Management Challenge.’

Featured image credit: Hourglass clock time by stevepb via Pixabay.

The post To be a great student, you need to be a great student of time management appeared first on OUPblog.

Nikolai Trubetzkoy’s road to history

A century ago, the Russian Revolution broke out in November of 1917, followed by a bloody civil war lasting until the early 1920s. Millions of families were displaced, fleeing to Europe and Asia. One of the many emigrant stories was that of Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy.

Trubetzkoy was from a well-known aristocratic family in tsarist Russia, and both his father and uncle had taught Moscow University. Boris Pasternak, who was a fellow student of Nikolai’s and a family friend, described them as “two elephants [who] … in aristocratic burring imploring voices, delivered their brilliant courses.” Vladimir Lenin was less charitable to Trubetzkoy’s father, who been part of a 1905 delegation proposing reforms to Nicholas II. When Trubetzkoy’s father died, Lenin’s obituary refer to him as “the tsar’s bourgeois flunkey.”

Young Nikolai Trubetzkoy was something of a prodigy, publishing work on Finno-Ugric folklore at the age of just fifteen. At Moscow University, he studied Indo-European comparative linguistics, completed a master’s degree and joined the faculty as privatdozent, or private lecturer, offering courses in Sanskrit.

Throughout his life, Trubetzkoy suffered from health problems, and he was taking a break from teaching to recuperate in Kislovodsk, in the North Caucasus, when the Soviet Revolution broke out. He never returned to Moscow. He and his family made their way to Baku in Azerbaijan, then northwest to the port city of Rostov-on-Don, later to Sofia, Bulgaria, and finally to Vienna in December of 1922.

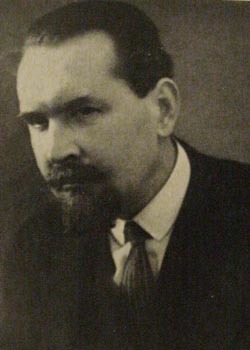

Nikolai Trubetzkoy in the 1920s. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Nikolai Trubetzkoy in the 1920s. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In 1923, he became Chair of Slavic Philology at the University of Vienna and began an intense period of scholarly work and teaching, giving five lectures weekly on topic in Slavic languages, literature, and later linguistics. Trubetzkoy also kept up a lively correspondence with his friend Roman Jakobson and in the 196 letters Jakobson preserved we see insights into Trubetzkoy as a person. His financial situation and health concerns were ever-present, as were worries about the reception of his and Jakobson’s linguistic theories.

As an emigre, his interests had evolved. Folklore research in the Caucasus was no longer possible. His teaching assignments in Vienna broadened his interests to modern literature. Jakobson invited him to join the newly formed Prague Linguistics Circle and Trubetzkoy periodically made the long trek from Vienna to attend their meetings and present his work.

The connection with Prague would also shape his research. Since 1915, Trubetzkoy had planned to write a pre-history of the Slavic language, but that work would only be published long after his death. Trubetzkoy first took on the more fundamental task of developing a methodology to study the sound pattern of language. His synthesis and insights from nearly two hundred languages formed the basis of his most famous work, the Grundzüge der Phonologie (Principles of Phonology).

But Trubetzkoy’s interests went beyond linguistics. He saw history as shaped by oppositions between historical forces, not unlike the oppositions that defined sounds. During his period in Sofia, Trubetzkoy wrote a political book called Europe and Mankind, part of a planned trilogy on problems of nationalism. Trubetzkoy called for a “revolution of consciousness” and warned against nationalism. He became one of the leaders of the movement known as Eurasianism arguing that similarities of language, art, religion and temperament would result in cultural unions resistant to colonization.

Trubetzkoy kept up his political writing in the 1920s and 1930s, following Europe and Mankind with a sarcastic preface to a translation of H. G. Wells’s Russia in the Shadows. His 1923 essay “At the Door: Reaction? Revolution?” argued that political progress always becomes a new status quo. In all, he would publish nearly a dozen essays on politics including critiques of the Soviet and Nazi regimes in such essays as “On the Idea Governing the Ideocratic State,” “The Decline on Creativity” published in the mid-1930s. Trubetzkoy became a public opponent of Nazism, and his 1935 article titled “On Racism” warned that the historical anti-Semitism of the Russian intelligentsia would allow it to be manipulated by the Nazi agenda.

Roman Jakobson. Philweb Bibliographical Archive, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Roman Jakobson. Philweb Bibliographical Archive, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.His political writings would also contribute to his death. In March of 1938, after the Nazis annexed Austria, Trubetzkoy’s Vienna home was searched by the Gestapo, his papers were confiscated, and he was subject to a lengthy interrogation at Gestapo headquarters. The strain was too much for Trubetzkoy’s already existing heart condition. Trubetzkoy collapse and was hospitalized. He died in a hospital in Vienna on 25 June 1938.

Trubetzkoy’s legacy lives on today, preserved by others. Roman Jakobson ensured that the German edition of Principles of Phonology was quickly published in 1939, and Trubetzkoy’s ideas about distinctive feature theory and markedness made their way into modern phonological theory by way of Noam Chomsky and Morris Halles’s Sound Pattern of English. Vera Petrovna Trubetzkoy, who had been an intellectual partner to her husband, saw to the publication of Trubetzkoy’s literary studies in the 1950s, and in 1991, Anatoly Liberman guided the translation and provided critical commentary on much of Trubetkoy’s political writing in The Legacy of Genghis Khan and Other Essays on Russia’s Identity. And today, nearly a century after his exodus from Russia, Trubetzkoy’s intellectual courage and commitment remain important.

Featured Image credit: bas-relief of Nikolai Trubetzkoy in the Arkadenhof of the University of Vienna by Vanja Radauš, 1974. Hubertl, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Nikolai Trubetzkoy’s road to history appeared first on OUPblog.

Q&A with editors Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler

Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler are the editors of the new second edition of The Jewish Annotated New Testament. We caught up with them to discuss and ask questions related to the editing process, biblical studies, and the status and importance of Jewish-Christian relations.

In what areas, in your opinion, have Jewish-Christian relations improved the most, and where is there still more work to be done?

The greatest benefit is our recognition of our common histories: Jews are becoming increasingly familiar with the New Testament as a source of Jewish history, and of how selective interpretations of those texts create hatred of Jews and Judaism. Christians are more aware of the Jewish contexts of Jesus and Paul, and of how knowledge of those contexts can deepen their faith.

You mention the concept of “holy envy” in the Editor’s Preface of the first edition and discuss 1 Corinthians 13:4-7. Could you speak a little bit more about what “holy envy” is and perhaps give another example or two of times you experienced it while working on this project?

“Holy envy” refers to the idea that one’s religious tradition does not contain all of the wisdom in the world, and that as we study other traditions, we find ourselves deeply appreciating those texts, practices, and ideas. We find in studying Jesus and Paul, comments that deeply resonate with us. Paul’s description of love in 1 Corinthians 13 resonates across the centuries; Jesus’ parables provide brilliant examples of Jewish wisdom.

What is the most valuable thing you’ve gained through the process of working on this project, be it professional, spiritual, or personal?

Levine: Working with a co-editor who knows his material, who asks the right questions, and who makes all contributions better by his gentle but firm nudging.

Brettler: All the same things as Amy, plus for me, as a scholar of the Hebrew Bible and Judaism, this was my first serious extended engagement with early Christianity, which I now understand and appreciate much better than before.

What trends do you see in biblical studies and scholarship today?

We are moving increasingly toward readings based on our own subject positions: Korean theological readings, Womanist readings, Post-colonial readings, readings from the perspective of disability studies, and so on. These are all to the good. Yet if we lose the history, or we simply make historical approaches one of many equally valid approaches, we wind up erasing the very subject positions, the very cultural contexts, in which the figures and writers of the New Testament lived.

What do you think should be the biggest focus in biblical studies today?

We would not reduce biblical studies to one focus. All textual studies can begin with the question, ‘what does this text mean to you?’ Biblical studies then needs a few more questions: ‘What has this text meant over time?’ ‘What might it have meant in its original context?’ People who hold the text to be sacred will have even more questions: ‘what is the ‘‘Good News’ in this verse?’ ‘How would God want me to act?’ In the context of the Jewish Annotated New Testament, we would emphasize: ‘What do we learn when we hear Jesus as a Jew speaking to other Jews?’ ‘What do we learn when we recognize that Paul is a Jew speaking not to Jews but to gentiles?’

We care deeply about both the problems and the opportunities that biblical texts present, and we believe that it is always important to explore two opposing questions. First we ask how select interpretations have harmed others, whether women, people enslaved, Jews and other religious and ethnic groups, people with physical disabilities, people who choose life partners outside select biblical norms, and so on. Second, we ask how the Bible has lead and might lead to flourishing and liberation?

Featured Image credit: Jerusalem Old City from Mount of Olives by Wayne McLean (Jgritz). CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Q&A with editors Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers