Oxford University Press's Blog, page 320

September 26, 2017

On serendipity, metals, and networks

“What connects archaeology and statistical physics?”, we asked ourselves one evening in The Marquis Cornwallis, a local Bloomsbury pub in London back in 2014, while catching up after more than a decade since our paths crossed last time. While bringing back the memories of that time we first met when we were both 16, it hit us that our enthusiasm for research we did as teenagers had not faded away: Jelena has always been occupied with game theory and networks, while Miljana has never stopped pursuing evidence for the world’s earliest metallurgy in the Balkans. Apart from sharing excitement that things at the end did not turn out too bad for us, two postdocs at the time at UCL and Imperial College London, we didn’t know details about each other’s research. Nevertheless, that winter night in The Marquis Cornwallis we decided to investigate the connection – not only for the sake of science, but for the thrills of reliving the days we spent together as teenagers in the famous Balkan ‘nerd hub’, Serbian Petnica Research Centre.

The first run of metals data through complex networks algorithms happened the night before we were due to deliver our ideas on how networks research can benefit early Balkan metallurgy research at a physics conference. Needless to say, we (over)committed ourselves to delivering a fresh view on this topic without giving it a thorough thought, rather, we hoped that our enthusiasm would do the job. That night, the best and the worst thing happened: our results presented the separation of modules, or most densely connected structures in our networks, as statistically, archaeologically, and spatiotemporally significant. The bad news was that we stumbled upon it in a classic serendipitous manner – we did not know what was it that we pursued, but it looked too good to let go. It subsequently took us three years to get to the bottom of networks analysis we made that night.

In simple terms, what we did here is present ancient societies as a network. A large number of systems can be represented as a network. For example, human society is a network where the nodes are people and the links are social or genetic ties between them. A lot of real-world networks exhibit nontrivial properties that we do not observe in a regular lattice or in the network where we connect the nodes randomly. For example social networks have the property called ‘six degrees of separation’, which means that the distance between any of us to anybody else on the planet is less than six steps of friendships. So any of us knows somebody, who knows somebody etc (six times) who knows Barack Obama or fishermen on a small island in Indonesia. Another property that is common in complex networks is so-called modularity. This means that some parts of the network are more densely connected with each other than with other parts of the network. Successful investigation of modularity or community structure property of networks includes detecting modules in citation networks, or pollination systems – in our case we used this property to shed light on the connections between prehistoric societies that traded copper. It turned out that they did not do it randomly, but within their own network of dense social ties, which are remarkably consistent with the distribution of known archaeological phenomena at the time (c. 6200- 3200 BC), or cultures.

What we managed to capture were properties of highly interconnected systems based on copper supply networks that also reflected organisation of social and economic ties between c. 6200 and c. 3200 BC.

Our example is the first 3,000 years of development of metallurgy in the Balkans. The case study includes more than 400 prehistoric copper artefacts: copper ores, beads made of green copper ores, production debris like slags, and a variety of copper metal artefacts, from trinkets to massive hammer axes weighing around 1kg each. Although our database was filled with detailed archaeological, spatial, and temporal information about each of 400+ artefacts used to design and conduct networks analyses, we only employed chemical analysis, which is the information acquired independently, and can be replicated. Importantly, we operated under the premise that networks of copper supply can reveal information relevant for the specific histories of people behind these movements, and hence reflect human behaviour.

Our initial aim was to see how supply networks of copper artefacts were organised in the past, and as the last step of analysis we planned to utilize geographical location only to facilitate visual representation of our results. Basically, if two artefacts from the same chemical cluster were found in two different sites, we placed a link between them. In the final step, the so-called Louvain algorithm was applied in order to identify structures in our networks, and we used it as a good modularity optimization method. Another advantage is this approach is that we can test its statistical significance and put a probability figure to the obtained modules.

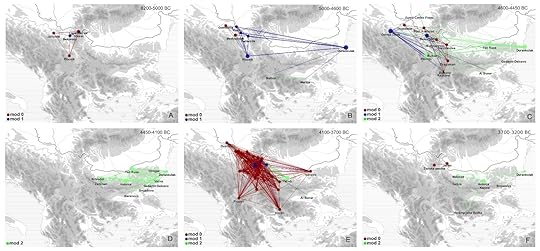

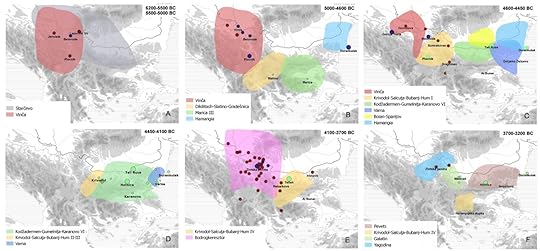

What we managed to capture were properties of highly interconnected systems based on copper supply networks that also reflected organisation of social and economic ties between c. 6200 and c. 3200 BC. The intensity of algorithmically calculated social interaction revealed three main groups of communities (or modules) that are archaeologically, spatiotemporally, and statistically significant across the studied period (and represented in different colours in Figure 1). These communities display substantial correlation with at least three dominant archaeological cultures that represented main economic and social cores of copper industries in the Balkans during these 3,000 years (Figure 2). Basically, such correlation shows that known archaeological phenomena can be mathematically evaluated using modularity approach.

Figure 1. Three community structures (modules 0, 1 and 2) presented throughout c. 6200 – 3200 BC in the Balkans. Provided by the author and used with permission.

Figure 1. Three community structures (modules 0, 1 and 2) presented throughout c. 6200 – 3200 BC in the Balkans. Provided by the author and used with permission. Figure 2. Distribution of archaeological cultures / ‘copper industries’ in the Balkans between c. 6200 and c. 3200 BC (shaded), with the most relevant sites. Note colour-coding and size of nodes consistent with the module colour (Module 0 – red, Module 1 – blue, Module 2 – green). Provided by the author and used with permission.

Figure 2. Distribution of archaeological cultures / ‘copper industries’ in the Balkans between c. 6200 and c. 3200 BC (shaded), with the most relevant sites. Note colour-coding and size of nodes consistent with the module colour (Module 0 – red, Module 1 – blue, Module 2 – green). Provided by the author and used with permission.Although serendipity marked the beginnings of our research, our plan is to take it from here with a detailed research strategy plan, which now includes looking at other aspects of material culture (not only metals), testing the model on datasets across prehistoric Europe, or indeed different chronological periods. We can say that the Balkan example worked out well because metal supply and circulation played a great role in the lives of societies within an observed period, but it may not apply in cases where this economy was not as developed. The most exciting part for us though was changing our perspective on what archaeological culture might represent. Traditional systematics is commonly looking at cultures as depositions of similar associations of materials, dwelling and subsistence forms across distinct space-time, and debates come down to either grouping or splitting distinctive archaeological cultures based on expressions of similarity and reproduction across the defined time and space. But now we have the opportunity to change this perspective and look at the strength of links between similar material culture, rather than their accumulation patterns. This is a game changer for us. And we hope that this research inspires colleagues to pursue this idea of measuring connectedness amongst past societies in order to shed more light on how people in the past cooperated, and why.

Featured image credit: Mountains in Bulgaria by Alex Dimitrov. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post On serendipity, metals, and networks appeared first on OUPblog.

From Saviors to Scandal: Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker [timeline]

The history of American televangelism is incomplete without the Bakker family, hosts of the popular television show the PTL Club. From their humble beginnings to becoming leaders of a ministry empire that included their own satellite network, a theme park, and millions of adoring fans. Then they saw it all come falling down amidst a federal investigation into financial mishandling, charges of fraud, and a sex scandal with a church worker. In the timeline below, created from PTL: The Rise and Fall of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Evangelical Empire by John Wigger, are the chronicles of these fixtures of not only Christian television but American pop culture.

Featured Image: Televangelism by Josh McAllister. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post From Saviors to Scandal: Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Free speech and political stagflation

First Amendment Law is distorting public debate. We need the Supreme Court to do better.

Public political debate in the United States seems to have run off the rails. The gulf between Republicans and Democrats in political opinions, views of the other party, and even factual beliefs keeps growing. Big money dominates the electoral process. Journalists and political dissenters face relentless hostility. In response, public intellectuals lament our political culture’s descent into chaos and yearn for corrective discipline.

From a broader perspective, though, our problem isn’t too much chaos. It’s too much stability.

US political debate circa 2017 is tracking the US economy circa 1974. Before that time, slow growth alternated with high inflation. We learned in the 1970s, though, that economic forces could produce at once the worst of both worlds: slow growth along with high inflation. That economic purgatory spawned a new term: stagflation.

Our political discourse works like that now. Yeats diagnosed our condition a century ago: a state of “[m]ere anarchy” where “[t]he best lack all conviction, while the worst [a]re full of passionate intensity.” Powerful institutions stunt the development of new ideas, even as cheap provocateurs spit bile at each other. Few fresh, useful policy proposals gain any traction. The Republicans obsess over negating Obamacare, while the Democrats implore “Have you seen the other guys?”

“Trump and Obama” by VectorOpenStock. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Trump and Obama” by VectorOpenStock. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Our political stagflation has many causes, but a big chunk of the blame lies with the US Supreme Court. Why? Because the Court has the last word in how First Amendment law structures our political discourse. The First Amendment doesn’t guarantee a robust or productive public debate; it doesn’t provide any content. Even so, First Amendment law largely dictates whose ideas will reach large audiences and which constraints will stifle different speakers and arguments.

The Supreme Court’s First Amendment decisions make a system of canals for the flow of public discussion. The Court under Chief Justice John Roberts has spent the past decade letting big expressive tankers clog up those canals. The Roberts Court’s First Amendment has strengthened powerful institutions’ dominance of public debate while letting the government squelch dissenters who might challenge dominant ideas. We can trace many aspects of political stagflation right to the Court’s marble steps.

Partisan polarization? The Roberts Court has made it harder for insurgent candidates to challenge the power of party machines. This follows older decisions that helped the major parties squelch voters’ options to cross party lines in primaries, limited minor parties’ electoral strategies, and eased constraints on how the major parties can fund their candidates.

Big money in elections? You know Citizens United, but that’s just the beginning. The Roberts Court has also shredded federal limits on the money rich individuals can contribute to campaigns and blocked both federal and state efforts to make more funds available to candidates with deep-pocketed opponents.

“Republican Party debate in Iowa in 2016” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Republican Party debate in Iowa in 2016” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Weakening of serious dissent? The Roberts Court has let the government, in the name of national security, ban peace activists from pushing foreign terrorist groups toward peaceful conflict resolution. This Court also nurses a singular obsession with stopping labor unions from challenging the corporate power that Citizens United promotes.

There’s more. The Roberts Court has entirely ignored the First Amendment problems of the free press, emboldening official attacks on democracy’s watchdogs; has left street protesters (except anti-abortion “counsellors”) to the mercy of aggressive law enforcement and hostile legislators; and has slapped down public employees who try to expose government wrongdoing.

Healthy democratic debate requires both a broad range of ideas and opportunities for everyone to speak. Call that combination dynamic diversity. You might think the Internet would take care of ensuring dynamic diversity. Even online communication, though, operates under the sway of big institutions: Google, the tech powers, Amazon, the social media giants, the big providers of Internet access and content. The Roberts Court hasn’t lifted a finger to promote open communication online. In contrast, the Court has aggressively protected corporate data mining and toughened copyright protections.

We’re experiencing the wrong kind of chaos, sound and fury bound by rigid order: political stagflation. We need the right kind of chaos, a freewheeling discussion of big ideas: dynamic diversity. The Supreme Court, by boosting powerful speakers and weakening dissent, has greased our slide into political stagflation. Just as surely, however, the Court has the power to broaden expressive opportunities, protect dissent, and fuel dynamic diversity. As the Court begins another Term, we can only hope it will shift its First Amendment priorities.

Featured Image Credit: “Supreme Court Building” by Free-Photos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Free speech and political stagflation appeared first on OUPblog.

September 25, 2017

Banned, burned, and now rebuilding: Comics collections in libraries

Comics is both a medium—although some would say it’s an art form—as well as the texts produced in that medium. Publication formats and production modes differ: for instance, comics can be short-form or long-form, serialized or stand-alone, single panel or sequential panels, and released as hardcovers, trade paperbacks, floppies, ‘zines, or in various digital formats. Superheroes as a comics genre may get the most attention, especially given the high profile films and televisions shows such as Wonder Woman (2017 film), Luke Cage (2016 – series), and Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015 film), but comics is more than superheroes. Creators use comics to tell tales of horror (e.g. Harrow County), romance (e.g. Fresh Romance), slice of life (e.g. Aya), and fantasy (e.g. Monstress), as well as share factual information about notable people (e.g. Strange Fruit, Vol. 1: Uncelebrated Narratives from Black History), science and medicine (e.g. Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atom Bomb), social and political conditions (e.g. Zahra’s Paradise), and more. Some comics even reimagine works of literature (e.g. Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred).

Libraries and academic institutions have been slow to embrace comics in their collections and classrooms. Although there are outliers, US libraries only began to get serious about collecting comics in the late-1990s with most of the sustained interest and growth happening in the past decade. At the American Library Association’s 2017 Annual Meeting in Chicago, a full day of programming was held on comics and the exhibition hall even included an artists’ alley, where attendees could meet a couple of dozen cartoonists: this sort of intensive attention to comics in library settings was unimaginable even ten years ago. A quick and dirty search of doctoral dissertations in which the word “comics” appears in the abstract gives evidence to increasing academic attention: since 2000, nearly 1400 dissertations were published, which is roughly equal to the number published between 1930 and 1999 (and most of those were published in the 1980s and 90s).

A chief reason for this delayed interest in comics among US librarians is a long-held prejudice against the medium. For instance, in the early 1900s as newspaper comic strips began to be syndicated and reach wider audiences, many librarians chose to remove the comics pages from newspapers to keep the library more quiet and orderly, as well as to protect young readers their “poor drawings, worse colors and bad morals.” Those sentiments continued and grew, peaking in the 1950s with psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent, which lambasted comics for their purported degradation of young people’s mental hygiene, and the introduction of the Comics Code Authority, an industry content regulation group which came into being because of fears that the US government might regulate comics following 1954 Senate hearings. These actions, among many others, helped encourage long-standing opinions that comics of all kinds were juvenile and immoral texts that did merit collection.

As I noted, librarians and educators are beginning to change their perceptions of comics and embracing them as tools and texts for pleasure reading, student learning, and academic inquiry. Some of my own scholarship and teaching has been in at least a small way instrumental in these changes. For instance, since 2011, I have taught a regular course on reader’s advisory for comics in my role as a faculty member of the iSchool at University of Illinois. Similarly, in 2012, I published research that noted falsifications and discrepancies in Fredric Wertham’s research that calls into question his belief that comics reading is harmful. I have the pleasure of speaking on comics history and the role of comics in libraries throughout the US—including at events like NASIG 2017 and an American Library Association-sponsored talk at New York Comic Con—and helping librarians and educators understand the importance and legitimacy of comics in the lives of readers.

To help you learn more about what’s happening with regard to libraries, academic institutions, and comics, I’ve put together some links to library collections and scholarly groups for you to explore. These sources are only a beginning. Comics are an important part of our US cultural heritage and there are rich traditions of comics and cartooning around the world, from France to Japan to Argentina to India. Comics belongs to all of us and deserves space in our collections and classrooms.

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum (Ohio State University), This collection, which had its genesis in the 1970s, is now the world’s largest collection of comics and related materials. It is especially strong in newspaper comics, both printed pages and original artwork. It also serves as a repository for cartooning-related manuscript collections such as Milton Caniff, Walt Kelly, and Bill Watterson.

Browne Popular Culture Library (Bowling Green University), Although comics are a key focus here (they have one of the largest collections in the US), this library also includes comics-adjacent materials like trading cards and story papers.

Butler Library (Columbia University), In the past decade, librarian Karen Green has built this comics collection from nothing. In addition to more than 10,000 circulating graphic novels and comics in more than a dozen languages, Butler Library holds a growing number of comics-related archival collections including alternative comics publisher Kitchen Sink Press and cartoonist Howard Cruse.

Comic Arts Collection (Michigan State University), Librarian Randall Scott has helped build and maintain the collection here since the 1970s. It is now more than 200,000 items strong, with particularly strong holdings in US comic books and growing collections of international comic books.

Comics Studies Society is a recently founded international scholarly society with more than 500 members. With Ohio State University Press, it publishes the quarterly journal INKS and will hold its first conference in August 2018.

Duke University Libraries is home to the Edwin and Terry Murray Comic Book Collection with more than 60,000 volumes and its corollary Fanzine Collection, which contains more than 1,000 items.

Eaton Collection of Science Fiction and Fantasy (University of California – Riverside Library), The strength of this collection is fanzines, which are not all comics-related but many would be of interest to comics scholars. In addition, there are thousands of issues of pulp magazines and comics.

Government Comics Collection (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), Librarian Richard Graham curates a digital repository of more than 200 comics produced between the early 20th century and today for federal and state governments and similar bodies. Topics include monetary policy, racism, and the fishing industry.

Graphic Medicine explores how comics can engage healthcare. Its website provides reviews and news. Since 2010, there has been an annual Graphic Medicine conference as well.

International Comic Arts Forum (ICAF) is a long-running independent scholarly conference held annually and dedicated to all forms of comics art.

Library of Congress has several comics-related collections including the Small Press Expo (SPX) Collection, the Swann Collection of Caricature and Cartooning that features original art from creators such as Edwina Drumm and Winsor McCay, and the Comic Book Collection that contains more than 120,000 comics, many obtained via copyright deposit.

PS Magazine, the Preventive Maintenance Monthly (Virginia Commonwealth University), Will Eisner, a leading US cartoonist, helmed this magazine—a US Army publication—from 1951 through 1972. Each issue features several pages of a continuity comic titled, “Joe’s Dope Sheet,” that engaged with military history, vehicle maintenance, and other issues. You can view more than 200 complete issues here.

Underground and Independent Comics, Comix, and Graphic Novels (Alexander Street Press), This engaging digital resource combines scans of difficult to find underground and non-mainstream comics with historic contextual materials such as interviews and news clippings. It also includes The Comics Journal, a longtime print journal that provided criticism, history, and more.

Featured image credit: Photo by emiliefarrisphotos. CC via Pixabay.

The post Banned, burned, and now rebuilding: Comics collections in libraries appeared first on OUPblog.

Mathematical reasoning and the human mind [excerpt]

Mathematics is more than the memorization and application of various rules. Although the language of mathematics can be intimidating, the concepts themselves are built into everyday life. In the following excerpt from A Brief History of Mathematical Thought, Luke Heaton examines the concepts behind mathematics and the language we use to describe them.

There is strong empirical evidence that before they learn to speak, and long before they learn mathematics, children start to structure their perceptual world. For example, a child might play with some eggs by putting them in a bowl, and they have some sense that this collection of eggs is in a different spatial region to the things that are outside the bowl. This kind of spatial understanding is a basic cognitive ability, and we do not need symbols to begin to appreciate the sense that we can make of moving something into or out of a container. Furthermore, we can see in an instant the difference between collections containing one, two, three or four eggs. These cognitive capacities enable us to see that when we add an egg to our bowl (moving it from outside to inside), the collection somehow changes, and likewise, taking an egg out of the bowl changes the collection. Even when we have a bowl of sugar, where we cannot see how many grains there might be, small children have some kind of understanding of the process of adding sugar to a bowl, or taking some sugar away. That is to say, we can recognize particular acts of adding sugar to a bowl as being examples of someone ‘adding something to a bowl’, so the word ‘adding’ has some grounding in physical experience.

Of course, adding sugar to my cup of tea is not an example of mathematical addition. My point is that our innate cognitive capabilities provide a foundation for our notions of containers, of collections of things, and of adding or taking away from those collections. Furthermore, when we teach the more sophisticated, abstract concepts of addition and subtraction (which are certainly not innate), we do so by referring to those more basic, physically grounded forms of understanding. When we use pen and paper to do some sums we do not literally add objects to a collection, but it is no coincidence that we use the same words for both mathematical addition and the physical case where we literally move some objects. After all, even the greatest of mathematicians first understood mathematical addition by hearing things like ‘If you have two apples in a basket and you add three more, how many do you have?’

As the cognitive scientists George Lakoff and Rafael Núñez argue in their thought-provoking and controversial book Where Mathematics Comes From, our understanding of mathematical symbols is rooted in our cognitive capabilities. In particular, we have some innate understanding of spatial relations, and we have the ability to construct ‘conceptual metaphors’, where we understand an idea or conceptual domain by employing the language and patterns of thought that were first developed in some other domain. The use of conceptual metaphor is something that is common to all forms of understanding, and as such it is not characteristic of mathematics in particular. That is simply to say, I take it for granted that new ideas do not descend from on high: they must relate to what we already know, as physically embodied human beings, and we explain new concepts by talking about how they are akin to some other, familiar concept.

Conceptual mappings from one thing to another are fundamental to human understanding, not least because they allow us to reason about unfamiliar or abstract things by using the inferential structure of things that are deeply familiar. For example, when we are asked to think about adding the numbers two and three, we know that this operation is like adding three apples to a basket that already contains two apples, and it is also like taking two steps followed by three steps. Of course, whether we are imagining moving apples into a basket or thinking about an abstract form of addition, we don’t actually need to move any objects. Furthermore, we understand that the touch and smell of apples are not part of the facts of addition, as the concepts involved are very general, and can be applied to all manner of situations. Nevertheless, we understand that when we are adding two numbers, the meaning of the symbols entitles us to think in terms of concrete, physical cases, though we are not obliged to do so. Indeed, it may well be true to say that our minds and brains are capable of forming abstract number concepts because we are capable of thinking about particular, concrete cases.

Mathematical reasoning involves rules and definitions, and the fact that computers can add correctly demonstrates that you don’t even need to have a brain to correctly employ a specific, notational system. In other words, in a very limited way we can ‘do mathematics’ without needing to reflect on the significance or meaning of our symbols. However, mathematics isn’t only about the proper, rule-governed use of symbols: it is about ideas that can be expressed by the rule-governed use of symbols, and it seems that many mathematical ideas are deeply rooted in the structure of the world that we perceive.

Featured image credit: “mental-human-experience-mindset” by johnhain. CC0 via

Pixabay.

The post Mathematical reasoning and the human mind [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: an audio guide

Anna Karenina is a beautiful and intelligent woman, whose passionate love for a handsome officer sweeps aside all other ties—to her marriage and to the network of relationships and moral values that bind the society around her. Her love affair with Vronsky is played out alongside the developing romance between Kitty and Levin, and in the character of Levin, closely based on Tolstoy himself, the search for happiness takes on a deeper philosophical significance.

In this audio guide, listen to Rosamund Bartlett, editor and translator of the Oxford World’s Classics edition, introduce Anna Karenina and Leo Tolstoy’s style.

Featured image credit: “St Petersburg” by KiraHundeDog CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: an audio guide appeared first on OUPblog.

1617: commemorating the Reformation [excerpt from 1517]

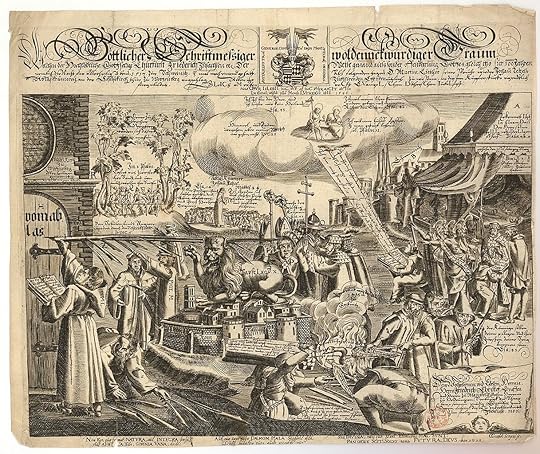

Martin Luther’s posting of the 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg is one of the most famous events in Western history – but did it actually happen on 31 October 1517? In this excerpt Peter Marshall looks at the commemoration of the Reformation’s centenary in 1617 that further cemented the idea that Martin Luther posted his theses on the 31 October 1517 precisely.

We have today become thoroughly accustomed to the notion that the passage of a hundred years after a significant episode or event constitutes an appropriate, almost a natural moment to commemorate it and reflect on its significance. Yet the idea of the centenary is itself a product of history. The decision in 1617 to stage celebrations and commemorations of Luther’s protest a hundred years earlier was the very first large-scale modern centenary. It was a critical moment, not only in how the Reformation was to be understood and remembered, but in how history itself would afterwards play a role in the public life of western Europe.

The growing concern with uniform blocks of years was scarcely a symptom of some ‘modern’, rationalizing way of seeing the world. Rather, an obsession with the measurement and inspection of time reflected the widespread conviction that the world was hastening towards its end, and that distinctive dates might be the markers in a continuing cosmic contest between the forces of Christ and Antichrist—a countdown to the Second Coming and Last Judgement. Luther’s eminence as a prophet of the end times was hailed in his own lifetime, and resurrected in numerous Lutheran New Year’s sermons for 1600: a David confronting and slaying the papal Goliath. Increasingly, 1517 was regarded as the year when this divine mandate was announced to the world.

The anniversary celebrations of 1517 were rooted in an existing culture of commemoration, and in a powerful ordering vision of a divine plan for humanity. But they were nonetheless the product of particular contemporary circumstances, and as they took shape, distinct religious and political agendas could be identified at work in them. The first impetus seems to have come, predictably enough, from the Theological Faculty at the University of Wittenberg. In March 1617, the Wittenberg theologians wrote to the supreme decision-making body for the territorial Church in Saxony, requesting permission to celebrate the last day of October as primus Jubileus Lutheranus, the first Jubilee of Luther.

Broadsheet depicting the early Reformation of the Christian Church as a prophetic dream of Frederick the Wise, the canny Elector of Saxony in 1617 by anonymous. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Broadsheet depicting the early Reformation of the Christian Church as a prophetic dream of Frederick the Wise, the canny Elector of Saxony in 1617 by anonymous. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The word ‘Jubilee’ was a carefully chosen one, and represented both a claim and a provocation. The concept’s origins were biblical. In the book of Leviticus, God instructed Moses that every fiftieth year was to be kept as a holy year of Jubilee, when fields were to be left untilled, debts redeemed, and slaves set at liberty. The idea of a holy year of emancipation and restoration was revived by the medieval papacy. In 1300 Pope Boniface VIII declared a year of grace, when special plenary indulgences were offered to those coming to Rome on pilgrimage. The original intention was for these papal jubilees to occur every hundred years, later reduced to every fifty in accordance with biblical precept. In 1470, Pope Paul II decreed that they should take place every twenty-five years, so that each generation might get to experience at least one. After a crisis of morale in the middle decades of the sixteenth century, the jubilees of 1575 and 1600 were celebrated in Rome with particular splendour—a symptom of the renewed confidence of the Catholic Church after the reforms, and the zealous condemnations of Protestantism, undertaken by the Council of Trent (1545–63).

Papal jubilees were inextricably tied up with indulgences, and with promises of access to the Treasury of Merits. For Lutheran theologians, appropriating the term was a daring act of theological piracy. The intention was that 1617 would be experienced, not just as a moment of historical retrospection, but as a true ‘holy year’ of divine favour and grace, a celebration of the triumph of the Gospel over the false promises of Antichrist. An effect was to underline still further the significance of the indulgence controversy—in itself a relatively minor skirmish in the grand clash of theological arms—as the underlying ‘cause’ of the Reformation in Germany.

As the evangelicals’ plans became clear, Rome reacted with predictable fury. The next holy year was not due until 1625, but on 12 June 1617 Paul V announced that the rest of the current year was to be kept as a period of extraordinary jubilee, a time of penance and atonement, and of prayer for God to protect the Church from its heretical enemies. Some Catholic territories fixed their main ceremonies for 31 October 1617 itself, in an effort to undercut the Protestant ‘pseudo-jubilee’. In places where Catholics and Lutherans lived side by side—such as in the great imperial city of Augsburg—rival celebrations took place at the same time and fuelled simmering sectarian hatreds. Some contemporary chroniclers even dated the beginning of the Thirty Years War, which was to erupt into open conflict in 1618, to the competing jubilees of the preceding year.

Featured image credit: Church Lutherstadt Wittenberg by unknown. Public domain via Max Pixel .

The post 1617: commemorating the Reformation [excerpt from 1517] appeared first on OUPblog.

What do the people want?

It has become commonplace for Government departments at all levels to ask people for their views. It seems as if no new policy or legislative plan can be launched without an extensive period of consultation with all those who may be affected. The UK government’s website page for ‘Consultations’ lists 494 consultations published already this year out of a total of 3,796 since the decade began. Devolved and local government too consult widely on everything from education policy to residents’ parking schemes. In a controversial move recently, health trusts in Northern Ireland have even begun a consultation on how exactly to cut £70 million from their budgets for local hospitals and healthcare services.

Perhaps this is following a trend towards interactivity set in the wider world. Here it seems that every online purchase leads to a request for feedback, and everyone from the local radio station to your favourite supermarket invites you follow it on Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, Pinterest, or Facebook. But maybe Government is slightly different in so far as it is less interested in securing your business and more in trying to meet a demand for greater participation and improved democracy. Certainly new technology, with its increased reach, speed, and interactivity, does seem to hold particular promise for letting governments know what the people want. However this begs a series of questions about whether government bodies actually want to know what the people want, how this is being measured, and whether they are prepared to give it to them.

New Polar Vessel visualisation by Cammell Laird / BAS. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.

New Polar Vessel visualisation by Cammell Laird / BAS. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.Leaving aside fraught issues about Brexit there is the where the National Environment Research Council ran a consultation in 2016 to find the name for a new £200 million polar research ship. Despite gathering 124,109 votes nationwide, the name “Boaty McBoatface” was passed over in favour of fifth placed name “RRS Sir David Attenborough” which had attracted only 10,284 votes – although in a compromise move the name was given to a smaller robot submersible vessel.

Are there more serious instances where people are being asked what they want and perhaps are not getting it? Could it be that government bodies are abusing the processes of consultation to give their decisions a veneer of democratic legitimacy? Are they obtaining the benefits of citizen engagement, stakeholder knowledge, and enhanced legitimacy, but without any commitment to giving the people what they want? Petition sites that allow members of the public to suggest initiatives for government to “consider” are increasingly popular at both European and Westminster level, as well as in Scotland and Wales and many local authorities. However, these may seem to some people to be redolent of medieval rituals where the common people petitioned their masters—and perhaps about as effective.

Hommage du comté de Clermont-en-Beauvaisis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Hommage du comté de Clermont-en-Beauvaisis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.From the citizen side, is online culture bringing the power of crowdsourcing, the participatory dynamic of open-source working, and a sense that free, democratic speech can now be expressed through a mouse click? Is our civic duty really met by simply providing an email contact on a petition webpage or clicking ‘like’ on a website? Or is this rather an instance of “slacktivism” and not a properly new form of democratic engagement for the online age?

The UK courts have been asked to assess the democratic quality of consultation exercises on a number of occasions. A recent case summarised the position, endorsing a series of rules known as the Gunning or Sedley Principles. These (quite reasonably) require that: (i) consultation must take place when the proposal is still at a formative stage; (ii) sufficient reasons must be put forward for the proposal to allow for intelligent consideration and response; (iii) adequate time must be given for consideration and response; and (iv) the product of consultation must be conscientiously taken into account. However in an important, recent decision in the Supreme Court the judges avoided the suggestion that there is any general common law duty to consult or that consultation should follow any particular format. Context is everything; the majority of the Supreme Court took the view that their role here is less concerned with opening up a public space for political participation than with protecting individuals where a right, an interest, or a legitimate expectation engages a more conventional idea of fairness.

This leaves public bodies with lots of discretion about how and who they consult. While there is plenty of guidance on good practice, and a superb handbook detailing 57 imaginative methods of engaging, Government is not always open to following this. Too often consultation involves simply a link to a .pdf document and a general invitation to respond. Indeed the UK Government’s two page document “Consultation Principles 2016” presents remarkably modest proposals. The eleven principles offered therein range from advice to use plain English, to a suggestion that consultees be given enough information to make an informed response, to a recommendation that agreement be sought before publication. This has led some critics to complain of distortions in the process, and even that the potential of consultation to reinvigorate democratic engagement is being wasted.

It is suggested that sometimes government consultation can muzzle views through a sort of participatory disempowerment whereby the existence of an official consultation exercise closes off further, alternative, or subaltern voices who are silenced by an official depiction of “the public” and the views garnered there. These official constructions of “the public” and of “community” and citizenship” can be made up quite arbitrarily, and may well privilege self-selected and more articulate groups of residents or activists. Nevertheless the views produced here come to be seen as neutral, or as valid “local knowledge” that can be given priority. This can operate to deplete the civic imagination rather than facilitate it.

MTR Express på Stockholm Central by Holger.Ellgaard. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

MTR Express på Stockholm Central by Holger.Ellgaard. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Very often, too, government more actively controls the form of the debate, its agenda, and the sources of information. Partisan citizens with vested interests or technical expertise may be excluded. Organizers set the agenda and questions for discussion, keep the records, and select which recommendations to ignore and which to accept. Putting the interaction online does not necessarily improve the interaction. Indeed, there is a view that it makes it worse. The internet is no more value-free, unstructured, or universal than any other space – and often people behave badly online.

All this suggests that we must work harder to make consultation effective and meaningful. The gains to be won by connecting governments with the public who they serve are huge, both in terms of improving service delivery and enhancing legitimacy. Of course, there does remain the problem that the people may not want very sensible things, and the challenge that this lays down to those who have asked them. This is perhaps nowhere better illustrated than in Sweden where the experience of the National Environment Research Council in the UK and its polar vessel inspired the respondents to an online poll initiated by a train operator to successfully propose that a new train be named Trainy McTrainface.

Featured image credit: Vote, Word, Letters, Scrabble by Wokandapix. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post What do the people want? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 24, 2017

Breaking down the Internet’s influence on grammar and punctuation [excerpt]

The Internet has become a key part of modern communication. But how has it influenced language structure? Surprisingly, formal writing remains unchanged. Informal writing, however, has seen an influx of stylistic changes. In the following shortened extract from Making Sense: The Glamorous Story of English Grammar, renowned linguist David Crystal breaks down the grammatical and syntactical evolution of language in the Internet-era.

The most obvious novelties [of the Internet’s influence on English] relate to the use of punctuation to mark constructions, where many of the traditional rules have been adapted as users explore the graphic opportunities offered by the new medium. We see a new minimalism, with marks such as commas and full stops omitted; and a new maximalism, with repeated use of marks as emotional signals (fantastic!!!!!!). We see some marks taking on different semantic values, as when a full stop adds a note of abruptness or confrontation in a previously unpunctuated chat exchange. And we see symbols such as emoticons and emojis replacing whole sentences, or acting as a commentary on sentences.

Although the formal character of grammar has been (so far) unaffected by the arrival of the Internet, there have been important stylistic developments. Short-messaging services, such as text messaging and Twitter, have motivated a style in which short and elliptical sentences predominate, especially in advertisements and announcements:

Talk by @davcr Wednesday 8 pm Holyhead litfest.

Grammar matters – dont miss.

The combination of shortening techniques plus the use of nonstandard punctuation makes it difficult at times to assign a definite syntactic analysis to the utterance. We often encounter a series of sentential fragments:

get a job? no chance still gotta try – prob same old same

old for me its a big issue or maybe Big Issue lol

We get the gist, but only the tweeter would be able to tell us whether, for example, the phrase for me goes with the preceding construction or the following one. On the other hand, the 140 characters of Twitter are sufficient to allow sentences of 25 or 30 words, so we also find messages that are grammatically regular and complex, with standard punctuation:

I’ll see you after the movie, if it doesn’t finish too late.

Will you wait for me at the hotel entrance where we met last time?

Long-messaging services, such as blogging, where there is no limitation on the number of characters, have allowed a style of discourse characterized by loosely constructed sentences that reflect conversational norms. Nonstandard grammatical choices now appear in formal written settings (print on screen) that would never have been permitted in traditional written texts, where editors, copy-editors, and proofreaders would have taken pains to eliminate them.

Blogs display lots of syntactic blends – the conflation of two types of sentence construction. Here are some simple blends I’ve seen online:

For which party will you be voting for in the March 9 election?

From which country does a Lexus come from?

In each case, we have a blend of a formal sentence, where the preposition goes in the middle, and an informal one, where it goes at the end:

For which party will you be voting? / Which party will you be voting for?

From which country does a Lexus come? / Which country does a Lexus come from?

Syntactic blends arise when people are uncertain about which construction to use – so they use them both. They are very common in speech. It’s an unconscious process, which operates at the speed of thought. We rarely see them in writing because copy-editors have got rid of them, but they surface quite often online, where such controls are absent. In this next example, the blend is more difficult to spot, unless you try reading it aloud:

Although MajesticSEO have already entered into the browser extension market with their release of their Google Chrome extension, the news that their release on Monday will open up their services to Mozilla Firefox browser users, giving them even quicker access to the information that they receive while using the tool.

Something goes horribly wrong when we reach users. We need a finite verb to make this sentence grammatical. It has to be gives them or is giving them or will give them, or the like. The problem here is that the writer has used a very long subject (the news … users, seventeen words), so by the time he gets to the verb he’s forgotten how the sentence is going. He evidently thinks that the sentence began at their release on Monday, where a non-finite giving would be acceptable.

the release … gives them even quicker access … their release on Monday will open up their services to Mozilla Firefox browser users, giving them even quicker access …

What is semantically most important in the writer’s mind (the news of the release) has taken priority over the grammatical construction.

It’s the length of constructions that gets in the way, in cases like this. Once a construction goes beyond the easy limits of working memory capacity, problems arise. If we ignore the grammatical words and focus on only the items with lexical content, we see the writer is trying to deal with nine chunks of meaning:

the news – their release – on Monday – will open up – their services – to Mozilla Firefox – browser – users [giving them even quicker access]

This is an awful lot to remember. No wonder the writer loses his way. He can’t recall where he’s been, and he’s anxious to push on to his main point, which is ‘quicker access’. So in his mind he starts the sentence all over again. If he’d read it through after writing it, or said it aloud (always a useful strategy), he might have spotted it. Even better, he might have rewritten the whole thing to make two shorter sentences. As it stands, it’s a 50-word monster.

Internet grammar in unconstrained settings such as blogs displays many features like blends that would pass unnoticed in everyday conversation, but which would attract criticism if they appeared in formal writing. Because most blogs are personal and informal, we pay little attention to them, as long as the writers get their meaning across.

The Internet is the world in which we live in now; but for grammarians it’s not only one that presents them with evolving styles and controversial usages. A major impact of the Internet is educational – the way it offers fresh opportunities and methods for the teaching and learning of grammar. Already, many grammar courses exist, aimed at both first language and foreign-language audiences, of all ages, and the availability of multi-media allows access to all spoken and written varieties of the language.

Featured image credit: “photo/business-communication-computer-connection” by Pixabay. CC0 via

Pexels.

The post Breaking down the Internet’s influence on grammar and punctuation [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Reforming the sovereign debt regime

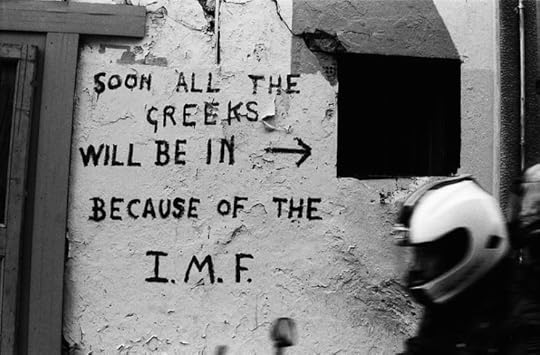

Since the start of its debt crisis in 2010, Greek citizens have suffered through seven years of agonizing austerity to satisfy the conditions of multiple consecutive bailouts from their official sector creditors – the so-called ‘Troika’, composed of the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF or Fund). And for what? The Greek government has a higher debt-to-GDP ratio today than it did in May 2010, when it received its first bailout program from the Troika.

What went wrong? There are many valid answers to this question, but an important one has to do with the politics of sovereign debt restructuring. As countless experts have argued and the IMF now admits, Greece should have undergone a sizeable debt restructuring at the outset of its crisis. And when the country did restructure its debt in the spring of 2012, it proved ‘too little, too late’ and was complicated by opportunistic ‘holdout creditors’. Moreover, Greece hasn’t been given any significant debt relief since 2012.

All of this speaks to the core problem in managing sovereign debt crises: the lack of an effective global framework or set of institutional arrangements for restructuring government debt obligations when they become unsustainable. This situation was described famously in 2001 as a ‘gaping hole’ in global financial governance by Anne Krueger, then deputy director of the IMF. To fill this gap, Krueger called for the creation of a ‘sovereign debt restructuring mechanism’ (SDRM) – essentially a formal bankruptcy process for sovereigns.

Her proposal was ultimately rejected by US Treasury officials who preferred an alternative solution: a ‘contractual approach’ which called upon debtor governments to insert ‘collective action clauses’ (CACs) into their international bond contracts. In the event of a default, CACs allowed a super-majority of bondholders to amend their contract terms and bind minority holdout creditors to the newly agreed deal. Sceptical at first, debtors and their private creditors eventually embraced CACs starting in 2003.

At the same time, the IMF introduced a new set of lending rules that prohibited it from making large loans to countries whose debts were not clearly sustainable. Tying the IMF’s hands in this way was supposed to encourage countries that were basically insolvent to restructure their debts, especially now that CACs could provide an orderly and predictable process for doing so.

However, the Greek crisis highlighted the weaknesses of these reforms. The IMF’s 2003 lending rules were bulldozed in 2010 to allow lending to Greece without an upfront restructuring. This decision benefited France and Germany (and their banking sectors, which at the time were highly exposed to Greek debt and would therefore suffer large financial losses from a restructuring) but did little to help Greece itself. And when Greece did restructure its debt in 2012, CACs were either absent (in its domestic-law bonds) or ineffective (in its foreign-law bonds) due to design flaws that were exploited by holdout creditors.

Just months later, the debt regime was pushed into further disarray by a controversial New York court ruling in favour of the holdout creditors that refused to participate in Argentina’s 2005 and 2010 restructurings. The judgment threatened to make future restructurings virtually impossible under New York law, to the detriment of debtors, the majority of their creditors, and the system as a whole.

Wall writing against IMF in Greece by georgetikis. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Wall writing against IMF in Greece by georgetikis. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.This context generated three new international reform initiatives. To address the controversies generated by the IMF’s 2010 decision to lend to Greece, the IMF’s lending rules were reformed once more in 2016 to make future decisions of that kind more difficult. But the new rules constrain the IMF lending in a less effective manner than the 2003 rules. And the Greek precedent highlighted to all that any rule was likely to be changed when it became inconvenient for powerful states. Taken together, the 2010 and 2016 changes to IMF lending rules have left the institution less likely to encourage debt restructuring than reformers in 2003 had hoped.

A second initiative focused on further strengthening sovereign bond contracts to facilitate smoother and more equitable bond restructurings. The coverage of CACs has been both expanded (to include all Eurozone countries) and improved to bind holdout creditors more effectively. In contrast to the uncertainties associated with IMF lending rules, these reforms promise to improve future debt restructuring in concrete ways.

The third initiative took place within the UN in 2014-15, where the G77 and China called for an ambitious ‘multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt restructuring’ (an idea that harkened back to the SDRM proposal). Ultimately, however, they settled for creating a set of non-binding principles for debt restructuring in 2015. Because of their voluntary content, the new UN principles are unlikely to have much tangible impact on the way sovereign debt restructurings are done.

These three sets of reforms have thus had a mixed impact on the debt restructuring regime compared to the arrangements put in place in the early 2000s. At the same time, they provide some deeper lessons about the politics involved in reforming the sovereign debt restructuring regime.

One lesson is that reforms focused on creating predefined rules to trigger debt restructuring (IMF lending reforms) run up against the interests of powerful states (and their private financial sectors) which prefer to decide on a case-by-case basis when debt restructuring should be triggered (and avoided). By contrast, reforms that seek to improve the process of restructuring once the decision to restructure has been taken (contract reforms) are more likely to succeed because they help facilitate coordination and reduce freeriding among creditors – goals that became particularly important in the wake of the Greek and Argentina episodes.

The UN initiative also reinforced a lesson learned by Krueger and her allies in the early 2000s: efforts to create an SDRM-style multilateral legal framework face enormous political obstacles. Such frameworks raise sensitive sovereignty issues for all states and present particular challenges to the interests of powerful Western states, private creditors, and even the sovereign debtors that are supposed to benefit from them. The post-2008 experience thus provides a stark reminder that the quest to fill the “gaping hole” in global financial governance identified by Krueger remains a very incomplete project.

Featured image credit: Money bank note euro by moerschy. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Reforming the sovereign debt regime appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers