Oxford University Press's Blog, page 316

October 5, 2017

The 5 best and worst things about gigging in a blues band (when you’re an academician)

For the last 16 years, I have been “supplementing” my day job as a professor by gigging in blues bands. There are advantages–that are also disadvantages–to the double life.

1. The Hours: Gigs are usually booked on weekends and evenings and don’t interfere with classes or meetings, but sometimes they run late into the night. In many college towns, the most popular drinking night is Thursday. In fact, I never saw as many students out and about in town as when I was packing up for a regular 10 p.m. to 1 a.m. gig in State College, PA. Students were everywhere, drinking, partying, falling down, and reveling, even in the snow. The down side to late night gigs is obvious: waking up early on Friday mornings when you get to bed at 2:30 or 3:00 can be tough, but there are unusual advantages to staying up late. First, you understand why your students have hacking coughs or fall asleep in class on Fridays and, therefore, are far less gullible about excuses. But oddly enough, Friday morning becomes the ideal time to schedule contentious meetings. Bleary and tired from playing until 1 and getting to bed late, Friday mornings I was often calm and patient, if slow to respond. I even deliberately scheduled a regular meeting of a senate committee I chaired on a sensitive, hot button issue at 8 a.m. Fridays because I knew that I would react slowly and keep my cool. As counterintuitive as it may seem, late night hours gigging can help productivity.

2. The People: Academics travel in restricted circles and don’t always have a chance to meet people outside of their regular orbits. Gigging forces you into unfamiliar circumstances that can be both beneficial and downright terrifying. On the positive side, you become aware of businesses (bars, restaurants, tap rooms) and how they function and connect with social networks in your community that you would otherwise never know about. You play county fairs, sleazy bars, fundraisers for bikers, as well as restaurants, tasting rooms, and popular drinking establishments. How else would I have ever learned that Alcoholics-Anonymous-style biker groups raise money for childhood burn victims (“send the burnt kids to camp”) or that winemaking is often a sideline for folks, like gigging is for me? The human connections include bandmates found on Craig’s List. Band members (and departmental colleagues) are like family members — you love them and you hate them. Problems with alcohol, pornography, anger, or a belief that you were abducted and probed by extraterrestrials all eventually surface. Meeting and interacting with a wider circle of people grounds me and, I believe, makes me a better teacher and colleague. At the very least, a little hardened by the road, certain looks of surprise and astonishment definitely cross my face less frequently in faculty meetings.

3. The Places: Gigs take me to areas that I didn’t know existed: small towns, remote areas, and sketchy sections of local cities. Traveling to new places can be rewarding: you learn about local festivals and traditions by being welcomed to entertain at events. Traveling can also be frightening. Scoping out a venue surrounded by strip clubs, with signs posted with warnings about carrying knives and guns, with a dance floor surrounded by chain-link fence, and giant subwoofers in the stage is intimidating. And sometimes you make the mistake of booking a gig sight unseen. I’ll never forget a western bar we played with a special room off the main bar. At the doorway to this room that was separated off by a curtain stood an ATM. Inside, there was a pole in the center with Naugahyde Barcaloungers arranged in a circle around it. At least it was empty.

4. Being treated like the help: Academics benefit from certain privileges. We may not earn as much money as those with advanced degrees and professional training employed in the private sector, but we are comfortable and mostly don’t engage in hard labor. Gigging means you’re the hired help and this can be infuriating, but also serves as a healthy reality check. Hauling equipment — speakers, amps, instruments — is tough work. Some venues require the band to clear a space to set up. I remember restaurant owners who made us move heavy tables before every show. Sore muscles and aching backs are a good reminder that most academic work is far from the drudgery of manual labor. Sometimes gigs provide bittersweet reminders about social class. I will never forget an insurance office Christmas party we played. The boss had killed an elk hunting and was proudly serving it to his coworkers. When they sat down to the meal, the band (3 professors and an attorney) took a break and were invited to eat the leftover hors d’oeuvres outside (in December) on the patio. At least I didn’t have to eat elk.

5. Students think you’re cool: Some of my favorite moments playing occur when young people in the audience do a double take or crane their necks to check me out in the band. This is sometimes followed on the set break by a conversation that begins, “I think I had you for a class.” In the best of times, this leads to comments like “you’re bad ass” or “you’re f***ing awesome,” high praise indeed for a professor. The downside to being cool involves receiving emails that begin “hey Julia” (sic.) or being addressed in class as “hey dude.” I try to refrain from launching into an etiquette lesson (but I don’t always succeed) and attempt to convince myself that being perceived as cool might just provide sugarcoating for the bitter pill of higher education.

Of course, the best thing hands down about moonlighting as a musician is the inspiration and insight it has provided for my research in the blues.

Featured image credit: by Julia Simon.

The post The 5 best and worst things about gigging in a blues band (when you’re an academician) appeared first on OUPblog.

October 4, 2017

Sheep and lambs on an etymological gallows

Animal names are so many and so various that thick books have been written about their origins, and yet some of the main riddles have never been solved. Today I’ll hang for a sheep. I am not sure why sheepish so often goes with smile and grin: sheep are excitable and skittish, they have “an intensely gregarious social instinct,” but they certainly never smile. “I feel sheepish,” an acquaintance of mine wrote me after missing an appointment, which I interpreted as “embarrassed.” When it comes to the etymology of sheep, we do suffer from an embarrassment of riches. Yet in this post I‘ll skip the so-called history of the question.

The oldest Indo-European name of the female sheep is related to Engl. ewe. Although its cognates turn up all over the place, as the main name of the species it has been supplanted in Germanic. Even the Goths called sheep lamb. It is instructive to see what happens elsewhere in the Germanic-speaking world. In Scandinavian, we find Old Icelandic sauðr (ð has the value of Engl. th in this). The word is related to a verb meaning “to cook; to boil.” One can guess its main ancient sense from Engl. seethe and sodden, the historical past participle of seethe. Sheep got this name because they were used for “boiling.” The situation is made clear by Gothic.

For a change, a lamb is neither prospective meat nor an animal to be shorn, nor a sacrificial animal.

For a change, a lamb is neither prospective meat nor an animal to be shorn, nor a sacrificial animal.The Goths, a Germanic-speaking tribe, were converted to Christianity in the fourth century, but coining an entirely new religious vocabulary is hard, and no tribe succeeded in accomplishing this task. The Goths needed a word for “sacrifice” and used sauþs (þ, as th in Engl. south), which had obviously been used for the pagan ritual. So that is why sauðr means “sheep”! It was a sacrificial animal, a sacrificial lamb. The old cognates of sauþs ~ sauðr are also instructive. They mean “spring” (as in spring water) and “well,” among a few other things, perhaps including “to burn slowly, while giving off smoke.” In this light, Engl. sodden “soaked through” does not come as a surprise (German gesotten still means “boiled”). A curious thing about Old Icelandic is that it had the compound ásauðr, with á, being a cognate of ewe (it is the accusative of ær), thus “sheep-sheep,” one of many tautological compounds in Indo-European (in such words, both elements mean the same: see the post for 11 February 2009).

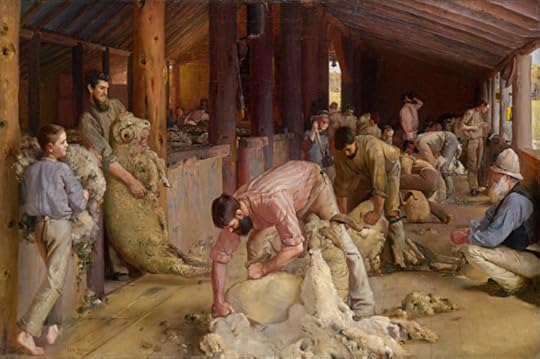

Sheep may exist to be shorn, but wool shearing, unlike wool gathering, is very hard work.

Sheep may exist to be shorn, but wool shearing, unlike wool gathering, is very hard work.But of course, sheep were also shorn. Hence Old Icelandic fær, which, like its rhyme-word ær, meant “sheep” (æ designated a long vowel and had the value of a in Engl. fat). The form fær goes back to fahaz. Its h was lost between two a’s; hence long æ. Among the cognates of the Old Icelandic word we find Od Engl. feht “sheepskin,” Middle Dutch vacht “fleece,” and Latin pecto “I comb.” (Fleece, another ancient word, has nothing to do with fær.) The fær received its name because it was a “wool animal.” English lacks cognates of fær (similar forms, borrowed from Scandinavian, have been recorded only in dialects), but one can recognize it in the name of Faroe Islands, literally “Sheep Islands.”

Faroe, or Sheep, Islands. They speak Faroese there.

Faroe, or Sheep, Islands. They speak Faroese there.We can now approach sheep. The most natural question is why so many Germanic words for this animal exist. Thus, fær is only Scandinavian, while sheep has cognates only in West Germanic. German Schaf and Dutch schaap, to mention two items on the list, are its exact congeners. Our surprise is increased by the fact that ewe and its kin did not disappear from the Germanic languages. Thus, Aue occurs in German dialects, and ooi is well-known in Dutch. The Goths had aweþi “herd of sheep” and awistr “sheepfold,” both of which were compounds, with the first element akin to Engl. ewe, but Gothic speakers still preferred to call the animal lamb.

We know that such general names as sheep, horse, and ox tend to coexist with specific ones. In a way, this is what we have already observed: sauðr is a sheep meant for sacrificial purposes or meat consumption, while fær refers to wool. Very common are the cattle names reflecting their age. For instance, twinter, a widespread word in British dialects, means an animal of two years, that is, winters, old (Germanic people measured time by winters: compare the opening of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 2: “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow….”). Old Icelandic gymbr “a one-year old ewe,” extant in the form gimmer in English dialects, contains the root related to Latin hibernus “wintry” (compare Engl. hibernate). The same root can be seen in Old Icelandic gemla “a one-year old sheep” and a few other words. As for heifer “a cow that has not calved,” I have written a thriller about its origin.

Even against this rich background, the etymology of sheep remains disputable. The situation with ewe is even worse: we have a common Indo-European word meaning “female sheep” but cannot explain how the sound group owi– (Proto-Germanic awi-) acquired its meaning. Did owi ~ awi describe the sheep’s bleating? After all, aw(i)-aw(i) would not be much worse than baa-baa, moo-moo, oink-oink, and bow-wow. Little Pig Robinson, the hero of Beatrix Potter’s long story, squealed wee-wee like a little Frenchman. Indo-European sheep have not changed since the beginning of creation. However, sheep is not an onomatopoeia! The Old English form of sheep was scēp (among a few others), a neuter noun, whose historical plural ended in u. After the loss of this ending, the singular and the plural merged; hence one sheep ~ many sheep today. The suggestions about why sheep ousted ewe as the main name of this animal do not go far and are too vague.

We are told that because of changes in habitat and climate there may have been no continuity in sheep breeding, with resulting new terms like sauðr, fær, and skæpa (the progenitor of sheep; this æ was also long). The coining of skæpa allegedly marked the progress the West Germanic tribes made in cattle breeding. Perhaps so. The emergence of a new term for a domestic animal might have been connected with a new specialized function. Not a bad guess. Inspired by the etymology of fær, we may follow the conjecture that skæpa has the same root as shave (Gothic skaban “to shear”). Quite puzzling is the substitution of lamb for the old word in Gothic. In that language, lamb came to mean both “lamb” and “sheep,” a loss of a serious distinction. Did the Goths prefer lamb to mutton and therefore allow the awi– word to disappear? In any case, they were certainly not inspired by linguistic considerations, for lamb is an even more obscure word than the cognates of ewe.

Every time we encounter a word that has an almost unrecoverable origin, someone suggests that this word was borrowed from a substrate language. Germanic speakers settled in the lands inhabited by the tribes that spoke non-Indo-European dialects. Plant names and the names of the animals that were new to the invaders were easy to borrow, but the sheep must have been familiar to the cattle breeders of old, and a corresponding Indo-European noun existed. Why should the speakers of West Germanic have borrowed the noun sheep, unless the natives had an entirely new breed of that animal? Be that as it may, in etymology, the influence of an unidentified substrate should be the port of last resort. I am saying this with a sheepish grin because so many scholars think differently.

The Oxford Etymologist with his habitual sheepish grin.

The Oxford Etymologist with his habitual sheepish grin.Image credits: Featured and (2): “Shearing the rams” by Tom Roberts, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (1) “Mary had a little lamb” by William Wallace Denslow, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (3) “Faroe islands map with island names” by Arne List, CC BY-SA 3.0 via . (4) “Man, portrait” by Mario, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Sheep and lambs on an etymological gallows appeared first on OUPblog.

World Space Week: a reading list

Space exploration has dominated human imagination for the most of the last 125-odd years. Every year we learn more about what lies beyond the limits of Earth’s atmosphere. We learn about extraterrestrial resources, such as metals on asteroids or water on the Moon; we discover new exoplanets that may be able to support life; we research new technologies that will get us onto planets a little closer to home, such as Mars.

In 2017, the UN is celebrating World Space Week by highlighting these discoveries and others under the theme “Exploring New Worlds in Space”. As governmental organizations and private enterprises are recognized for pushing the boundaries of exploration, we’ve brought together a selection of books and articles that describe some of the biggest breakthroughs of the last decade.

Planets: A Very Short Introduction by David A. Rothery

Our own Solar System is the place to start when learning about space. There are four ‘rocky’ planets in the system, but so far we’ve only discovered life on one (Earth, that is). What is it in the make-up of these terrestrial planets that suggests life, but doesn’t contain it? A short introduction to the topic might provide the answers.

Exploring the Planets: A Memoir by Fred Taylor

Exploring the Planets: A Memoir by Fred TaylorExploring the Planets: A Memoir by Fred Taylor

Comparing the meteorology of Mars and Earth has long been an aim of international space programmes in order to prove the viability of life on the Red Planet. With the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, NASA was able to gather data that will help to understand the climate on Mars and why it changed from one that could theoretically support life, to the frozen desert we know it as today.

“ Is it time for a manned mission to Mars? ” by Toby Samuels and Natasha Nicholson in Astronomy & Geophysics

Mars has long been next on the list of planets to which a manned mission should be sent. Has the time finally arrived to begin planning this tremendous endeavour? The “for” argument would have it that a timeline needs to be set in order to push the competition that will lead to this incredible feat of space exploration.

Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer of Planetary Atmospheres by Kelly Chance and Randall V. Martin

Looking at what makes up planetary atmospheres can help us learn about Earth’s atmosphere as well as learn about possibility of life in other systems. But how is this data even collected? Spectroscopic field measurements taken by remote sensors on satellites allows scientists to gather this data and how atmospheric constituents affect climate, biogeochemical cycles, and weather.

“ Planning our first interstellar journey ” by Ben Fernando in Astronomy & Geophysics

Breakthrough Initiatives, a programme set up by Pete Worden, Stephen Hawking, and Russian tycoon Yuri Milner, is funding private research into space exploration, including a trip to the star system nearest to ours. Breakthrough Starshot aims to develop a spacecraft that will make the journey to Alpha Centauri with a travel time of 20 years. Let’s see if in 40 years’ time this becomes reality!

Astronomy & Geophysics

Astronomy & GeophysicsLiving with the Stars: How the Human Body is Connected to the Life Cycles of the Earth, the Planets, and the Stars by Karel Schrijver and Iris Schrijver

While looking to outer space for conditions that might sustain life, what is it on Earth that made it possible for intelligent life (i.e. humans) to evolve? In large part it was the process of “terraforming” that occurred over a period of some 3.9 billion years through the twin chemical cycles of the water cycle and the carbon cycle.

A history of the International Space Station

The yearn for space exploration has resulted in building the International Space Station. But what exactly led to its construction? The history of this incredible feat in human engineering, politics, international collaboration, and bravery stretches from the first earth-orbiting satellite launch (Sputnik) in 1957, to astronauts from across the world continuing to live and work on the ISS in the present day.

“ Titan: the moon that thinks it’s a planet ” by John Zarnecki in Astronomy & Geophysics

Space exploration occurs mission by mission, with each on providing more and more data on the vast expanse beyond the Earth. As the Cassini mission draws to a close, the conclusion can only be that an enormous amount of data has been collected in its twenty years. One of the many discoveries is the existence of seven more moons around Saturn than previously thought.

Featured image: Sunrise by qimono. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post World Space Week: a reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Sanders-scare

Republican efforts to repeal and replace America’s Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) have featured one political miscalculation after another. After six-plus years of basing much of their electoral strategy on repealing Obamacare, the Republicans finally find themselves in control of both houses of Congress and the White House. After more than fifty Republican-led votes to repeal Obamacare—harmless while they were in the opposition—the consequences of repealing Obamacare (e.g., the loss of health insurance for millions of Americans and loss of coverage for preexisting conditions) have become clear to the American public. And the American public decided it does not like what the Republicans are offering, which is essentially “repeal” without “replace.”

Overpromising was a central feature of Donald Trump’s campaign for the presidency. He was going to build a big, beautiful wall and make the Mexicans pay for it. He was going to unleash a secret plan to defeat ISIS. He was going to cut taxes and balance the budget. He was going to bring manufacturing jobs back to the US. He was going to impose tariffs on China and Mexico. And he was going to repeal Obamacare and replace it with something really terrific. We know what has happened to these promises so far: absolutely nothing.

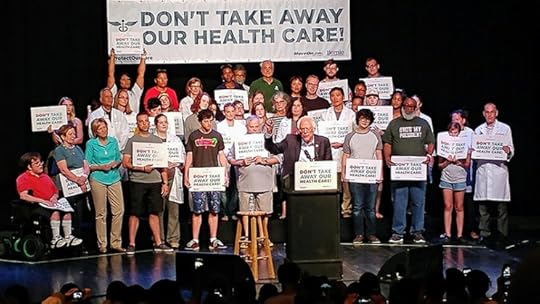

Unfortunately, Donald Trump and the Republicans aren’t the only ones making unrealistic promises. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) has now decided to get into the act—and, sadly, he seems to have developed a following among Democratic heavyweights.

Several weeks ago, Sanders introduced his “Medicare for All” bill (a.k.a. Sanderscare). According to his web site,

Bernie’s plan would create a federally administered single-payer health care program. Universal single-payer health care means comprehensive coverage for all Americans. Bernie’s plan will cover the entire continuum of health care, from inpatient to outpatient care; preventive to emergency care; primary care to specialty care, including long-term and palliative care; vision, hearing and oral health care; mental health and substance abuse services; as well as prescription medications, medical equipment, supplies, diagnostics and treatments. Patients will be able to choose a health care provider without worrying about whether that provider is in-network and will be able to get the care they need without having to read any fine print or trying to figure out how they can afford the out-of-pocket costs.

Although this may sound wonderful, there are more than a few holes in the proposal.

Don’t Take Our Health Care Rally with Senator Bernie Sanders at Live Express in Columbus, Ohio, on June 25, 2017 by Becker1999. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Don’t Take Our Health Care Rally with Senator Bernie Sanders at Live Express in Columbus, Ohio, on June 25, 2017 by Becker1999. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.The bill itself does not specify the sources of the money to pay for this program, leaving the financing to future legislation, although the Sanders website says it will be paid for by a combination of increased taxes and cost savings. Given that voting for a tax increase is often the quickest way for a Congressman to be unseated at the next election, this may not be a winning strategy.

An even bigger problem, according to observers like Catherine Rampell of the Washington Post and Jonathan Chait of New York magazine, neither of whom qualifies as a Republican or a conservative, is that more than 150 million Americans already have employer-based health insurance and many are largely satisfied with it. So moving them to a new system will be both costly and, quite possibly, unwelcome. According to Chait:

That is not a detail to be worked out. It is the entire problem. The impossibility of this barrier is why Lyndon Johnson gave up on trying to pass a universal health-care bill and instead confined his legislation to the elderly (who mostly did not get insurance through employers), and why Barack Obama left the employer-based system intact and created alternate coverage for non-elderly people outside it.

Like much of Sanders’ presidential platform, Sanderscare is long on promises and high-sounding rhetoric, but light on details.

A reader might wonder about the value of spending any time at all bad-mouthing a proposal that has no chance of becoming law, given that the Democrats are in the minority in Congress? The problem is that the Sanders proposal—unlike a similar effort he made in 2013–immediately gained 16 co-sponsors among the Democratic minority in the Senate, including potential presidential candidates Kirsten Gillibrand (NY), Kamala Harris (CA), Elizabeth Warren (MA), and Cory Booker (NJ). This is a troubling development, suggesting that these Democratic heavyweights have learned very little from the bad behavior of Donald Trump and his Republican colleagues in Congress.

Rather than jump on the bandwagon with a deeply flawed and gimmicky proposal, Democrats should get behind the sort of serious bipartisan effort championed by Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) in what he termed “a return to regular order” of hearings and bi-partisan negotiations. Such negotiations were going on between Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee chair Lamar Alexander (R-TN) and ranking member Patty Murray (D-WA) before Senate Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) put an end to them.

There are many bipartisan, incremental steps that can be taken to improve and strengthen Obamacare. Serious legislators, like Alexander and Murray, are on the right track. Democrats who aspire to be president should get behind these efforts, rather than mimic the over-promising, under-developed, all-or-nothing models of the Republican proposals or utopian, impractical solutions offered by Sanderscare. Voters should require nothing less from their leaders.

Featured image credit: Rally to Save the ACA by Molly Adams. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Sanders-scare appeared first on OUPblog.

More than just sanctuary, migrants need social citizenship

In 1975, the English author John Berger wrote about the political implications of immigration, at a time when one in seven workers in the factories of Germany and Britain was a male migrant – what Berger called the ‘seventh man’. Today, every seventh person in the world is a migrant.

Migrants are likely to settle in cities. In the United States, 20 cities (accounting for 36 per cent of the total US population in 2014) were home to 65 per cent of the nation’s authorised immigrants and 61 per cent of unauthorised immigrants. In Singapore, migrant workers account for 20 per cent of the city-state’s population. (Migrants continue to be a significant rural population. In the US, three-quarters of farm workers are foreign-born.)

Scholarship on migration tends to focus normative arguments on the national level, where policy concerning borders and immigration is made. Some prominent political philosophers – including David Miller at Nuffield College, Oxford, and Joseph Carens at the University of Toronto – also outline an account of ‘social membership’ in receiving societies. This process unfolds over five to 10 years of work, everyday life and the development of attachments. As Carens writes in ‘Who Should Get In?’ (2003), after a period of years, any migrant crosses a ‘threshold’ and is no longer a stranger. This human experience of socialisation holds true for low-wage and unauthorised migrants, so a receiving society should acknowledge that migrants themselves, not only their economic contributions, are part of that society.

Carens and Miller apply this argument to the moral claims of settled migrants at risk of deportation because they are unauthorised or because the terms of their presence are tightly limited by work contracts. In the US, for example, most of the estimated 11.3 million people who crossed a border without authorisation or are living outside the terms of their original visas have constituted a settled population for the past decade, with families that include an estimated 4 million children who are US citizens by birthright. In The Ethics of Immigration (2013), Carens writes that the prospect of deporting young immigrants from the place where they had lived most of their lives was especially troubling: it is ‘morally wrong to force someone to leave the place where she was raised, where she received her social formation, and where she has her most important human connections’. Miller and Carens concur with the Princeton political theorist Michael Walzer’s view of open-ended guest-worker programmes as ethically problematic. The fiction that such work is temporary and such workers remain foreign obscures the reality that these migrants are also part of the societies in which they live and work, often for many years, and where they deserve protection and opportunities for advancement.

Not all migrants will have access to a process leading to national citizenship or permanent legal residence status, whether this is because they are unauthorised, or their immigration status is unclear, or they are living in a nation that limits or discourages immigration while allowing foreign workers on renewable work permits. If we agree that migration is part of the identity of a society in which low-wage migrants live and work, whether or not this is acknowledged by non-migrants or by higher-status migrants, what would it mean to build on the idea of social membership and consider migrants as social citizens of the place in which they have settled? And what realistic work can the idea of social citizenship do in terms of improving conditions for migrants and supporting policy development?

Social citizenship is both a feeling of belonging and a definable set of commitments and obligations associated with living in a place; it is not second-class national citizenship. The place where one’s life is lived might have been chosen in a way that the nation of one’s birth was not; for a Londoner or a New Yorker, local citizenship can be a stronger identity than national citizenship. Migrants live in cities with a history of welcoming immigrants, in cities that lack this history, and also in cities where national policy discourages immigration. Considering how to ensure that social citizenship extends to migrants so that they get to belong, to contribute, and to be protected is a way to frame ethical and practical questions facing urban policymakers.

“The Statue of Liberty” by Free-Photos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“The Statue of Liberty” by Free-Photos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Considering migrants as social citizens of the cities in which they settle is related to but not the same as the idea of the city as a ‘sanctuary’ for migrants. Throughout the US, local officials have designated ‘sanctuary cities’ for undocumented immigrants subject to deportation under policies announced by the federal government in February 2017. This contemporary interpretation of an ancient concept refers to a policy of limited local cooperation with federal immigration officials, often associated with other policies supporting a city’s migrant population. Canadian officials use the term ‘sanctuary city’ similarly, to refer to local protections and potentially also to limited cooperation with border-control authorities. In Europe, the term ‘city of sanctuary’ tends to refer to efforts supporting local refugees and coordinated advocacy for refugee admission and rights. These local actions protecting migrants are consistent with a practical concept of social citizenship in which civic history and values, and interests such as being a welcoming, diverse or growing city, correspond to the interests of migrants. However, the idea of ‘sanctuary’ suggests crisis: an urgent need for a safe place to hide. To become social citizens, migrants need more from cities than sanctuary.

Local policies that frame social citizenship in terms that apply to settled migrants should go beyond affirming migrants’ legal rights and helping them to use these rights, although this is certainly part of a practical framework. Social citizenship, as a concept that should apply to migrants and non-migrants alike, on the basis of being settled into a society, can build on international human rights law, but can be useful in jurisdictions where human rights is not the usual reference point for considering how migrants belong to, contribute to, and are protected by a society.

What can a city expect or demand of migrants as social citizens? Mindful that the process of social integration usually takes more than one generation, it would not be fair to expect or demand that migrants integrate into a new society on an unrealistic timetable. Most migrants are adults, and opportunities to belong, to contribute, and to be protected should be available to them, as well as to the next generation. Migrants cannot be expected to take actions that could imperil them or their families. For example, while constitutionally protected civil rights in the US extend to undocumented immigrants, using these rights (by identifying themselves publicly, for example) can bring immigrants to the attention of federal authorities, a reality or fear that might constrain their ability to participate in civic life.

In his novel Exit West (2017), Mohsin Hamid offers a near-future fictional version of a political philosopher’s ‘earned amnesty’ proposal. Under the ‘time tax’, newer migrants to London pay a decreasing ‘portion of income and toil’ toward social welfare programmes for longstanding residents, and have sweat-equity opportunities to achieve home ownership by working on infrastructure construction projects (the ‘London Halo’). Today, the nonfictional citizens of Berlin are debating how to curb escalating rents so that the city remains open to lower-wage residents, including internal and transnational migrants. A robust concept of social citizenship that includes migrants who have begun the process of belonging to a city, and those who should be acknowledged as already belonging, will provide a necessary framework for understanding contemporary urban life in destination cities.

A version of this post was originally published on Aeon .

Featured Image: “New York City” by skeeze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post More than just sanctuary, migrants need social citizenship appeared first on OUPblog.

Buddhist nationalists and ethnic cleansing in Myanmar part 1: an introduction to the current crisis

Since August over 420,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar, citing human rights abuses and seeking refuge in Bangladesh. Sarah Seniuk and Abby Kulisz interview Michael Jerryson, a scholar who works on Buddhist-Muslim relations in Southeast Asia, in order to learn more about the background to this current crisis.

Abby: Michael, who are the Rohingya and what is exactly happening to them right now?

Michael: The Rohingya are a self-identified ethnic Muslim population that has lived in Myanmar for over 150 years. There are over 1 million Rohingya who have lived in Myanmar, a country in Southeast Asia. To understand the current crisis with them, it’s important to begin with their legal history. In 1982, the country enacted the Myanmar Citizenship law in which the Rohingya were omitted from the list of official ethnic groups and denied citizenship. During the junta reign from 1962 until 2011, there were conflicts between different ethnic and religious groups, but this was largely between the Buddhist state and the Karens, which were Christian-based. Starting at the end of 2011, the Burmese government transitioned to a more democratic rule of governance and the military stepped back.

Shortly after this democratic transition, there was a spike in violence in the far western province called Rakhine. The Rakhine Buddhists led attacks against a community that calls itself Rohingya. The reason I say “calls itself” Rohingya, is because the Burmese government refuses to acknowledge the legitimacy of the term, but the Rohingya self-identify as Rohingya.

Throughout the last couple decades the Rakhine Buddhist population has declined in percentage while the Rohingya population has increased and thus threatens a potential majority population. The tensions within the Rakhine Buddhist population soon manifested in violence. It began with allegations in June 2012 that Rohingyas raped a Rakhine Buddhist woman. There was no legal follow-through to verify this. Instead, the Rakhine Buddhist response was a massive attack on the Rohingya with the burning of villages. Over 100,000 Rohingya became refugees by the end of 2012. These refugees were placed into special camps. For the last five years, these Rohingya have been living in the camps. According to the journalist such as New York Times reporter Nicholas Kristof, the conditions within these camps are comparable to concentration camps.

Abby: Can you provide us with a general overview of the situation in Myanmar?

Michael: The attacks against Muslims spread from the Rakhine province to other areas in Myanmar, such as Meiktila in March 2013. As democracy unfolded in Myanmar and more voices were heard there was a marked increase of activity from the Buddhist nationalist groups on the need for Myanmar to become more Buddhist. One example of this comes in 2015 when the organization called the Ma Ba Tha, loosely translated as the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, pushed forward four new laws for Myanmar that were supposedly meant to protect Myanmar as a whole. The first of these laws was the monogamy law, which limited marriages to only one spouse. The second was the religious conversion law, which required the state to oversee any person’s religious conversion. The interfaith marriage law required state oversight over marriages between different religions, specifically Muslims and Buddhists. And lastly, the population control law, which required that mothers had to space their pregnancies so that they were at least 36 months apart from one another. All four of these laws, collectively, have been deemed by Human Rights Watch and other NGOs as discriminatory toward Muslims and the Rohingya.

Throughout the continued atrocities in these concentration camps, the Rohingya made attempts to escape. But they had no place to go. On 24 August, 2017, the Burmese government reported that the Rohingya insurgents attacked police in Rakhine province. These attacks sparked another wave of violence against the Rohingya. This violence was mounted by Burmese military and civilian personnel, and led to the fleeing of Rohingya from their homes. Over 170 villages were vacated, 80 villages burned to the ground. Over 400,000 Rohingya have fled across the Burmese borders to Bangladesh.

Sarah: How is this current violence different from what we have seen in the past?

Michael: Perhaps one of the most explicit differences is the intensity with the amount of lives displaced and lost. But another is the point of no return for the Burmese democratic government. In 2010, after two decades under house arrest the Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi was released. Two years later Myanmar emerged with a nascent, fragile democracy. It seemed premature for the international community to exert political pressure on her. And when Aung San Suu Kyi’s political party the National League for Democracy campaigned during the 2015 elections, international policy makers and rights activists thought that pushing her to make a strong stance against the violence might not be productive, because she was in a fragile position. The thought was that she wasn’t able to speak out too much without hurting the political capital of her party. But once Aung San Suu Kyi took office in April 2016 the situation became very different. She was able to solidify her base and the government. The question then became: how will Aung San Suu Kyi’s administration respond to this violence?

Unfortunately, from what we have seen from her party and from Aung San Suu Kyi herself have directly supported the alienation of the Rohingya and the official dismissal of violence against them. She has rejected inquiries by the United Nations into attacks and rape, she has refused to use the term Rohingya, and she has refused to acknowledge the human rights violations, claiming these violations stem from fake news. Now Myanmar doesn’t have a junta, but rather a democratic government supporting and taking part in the human rights violations and attacks. And there is now more violence and migration of refugees out of Myanmar than ever before.

The situation is similar to the current predicament with North Korea. US ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley argues that previous US presidents and Western governments have “kicked the can,” by not acting on North Korea in the hopes that things will get better. But this hasn’t happened and the international community is now at a point of “no return” when it comes to nuclear weapons in North Korea.

I believe the same situation has arisen in Myanmar. The international community has “kicked the can” until we have past the boiling point.

Featured Image credit: ROHINGYA: Hashimiah Orphans Madrasah at Pasar borong Selayang by Firdaus Latif. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Buddhist nationalists and ethnic cleansing in Myanmar part 1: an introduction to the current crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

October 3, 2017

World literature: what’s in a name?

What is world literature, and why are (some) people saying such bad things about it?

You might think world literature would be easy to define. You might think it should refer to all the literature in the world, past and present. And you might think that the study of world literature — which goes back to the 19th century but has really taken off only in the 21st, with a rapidly growing and impressive body of work — should simply be the analysis of all the literature in the world, past and present.

Yet many specialists in the area are uncomfortable with this approach. After all, we already have a name for all the literature in the world, past and present. That name is: literature. Why coin a new term? One answer is that we’re all, or nearly all, myopic. When we think of literature, we imagine something as circumscribed as our favorite subset of contemporary fiction, written in our own language and often in our own country. Even scholars with broad historical sweep routinely concentrate on a single language or, at most, on literatures in adjacent languages. So there’s something to be said for finding a designation suitable to a broader inquiry.

Still, there’s world literature, and then there’s world literature. This distinction may be understood both structurally and historically. Structurally, we can contrast soft with hard definitions — all the literature in the world versus only that literature involved in global connections. Historically, it’s possible to track a not-quite-linear increase in such planet-wide interactions up to the contemporary connected scene. Hence, where some scholars adopt a then-to-now perspective on the topic, others limit world literature to the period beginning with Columbus, or the Industrial Revolution, or even the post-World War Two era. One might argue, however, that this disagreement doesn’t much matter, as long as we recognize cross-cultural ties of great antiquity as well as the qualitative expansion of such linkages in recent centuries and, above all, in recent decades.

These debates concern definitional precision. But there’s also an objection to the very project of world literature. It has to do with what critics see as the parallels between world literature and globalization. The worry driving these objections is that attention to world literature amounts to de facto acceptance of globalization, together with all its injustices. The major intellectual predecessor to the field of world literature is colonial and post-colonial studies. Still thriving today, that line of inquiry turns on the continuing mistreatment of the poor nations by the rich. Attention to world literature might seem to repudiate this concern, instead positing a level playing field on which all peoples freely interact. Yet the world has changed. Along with increased hierarchy within countries, we find reduced — if still profound — inequality between rich and poor countries, together with a dramatic reduction in extreme poverty across the globe. There ought, then, to be no incompatibility between the two emphases indicated by post-colonialism and world literature. Both are important elements of the contemporary scene.

So much for “world.” What about “literature”? Two points are worth noting here. Discussions of world literature are centered in the English-speaking world, and especially the United States. College and university literature departments there have increasingly broadened their disciplinary purview, with the result that many are now effectively programs in cultural studies. Ironically, then, the opening out implied by world literature coincides with an older emphasis on literature as traditionally understood.

Second, that same US location of world literature means that it is situated in a country with an unusually high indifference to the literature of other nations and, even more, an ignorance of other languages. In this sense, the turn to world literature represents a salutary antidote to monoculturalism and monolingualism. No moral or political guarantees come with a literary curiosity about the experiences of people who display a striking combination of differences from, and similarities to, oneself. But it certainly beats the alternative.

Finally, a good place to start, to get a sense of the remarkable possibilities, is Words without Borders, which since 2003 has, in its own words, promoted “cultural understanding through the translation, publication, and promotion of the finest contemporary international literature.”

The post World literature: what’s in a name? appeared first on OUPblog.

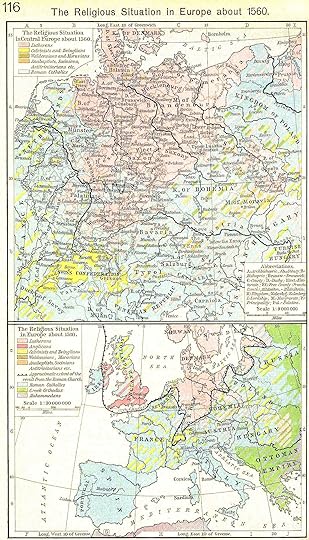

Mapping Reformation Europe

Maps convey simple historical narratives very clearly–but how useful are simple stories about the past? Many history textbooks and studies of the Reformation include some sort of map that claims to depict Europe’s religious divisions in the sixteenth century. Some of these maps show Catholic as opposed to Protestant states marked out in distinct colours. Other maps distinguish between varieties of Protestantism and show rival colours for Lutheran and Calvinist (and sometimes also Anglican) territories. Other maps attempt to present a more complex image of Europe’s religious demography with blobs of different colours showing the presence of minority groups within states. Some maps also provide a range of different colours to depict where Anabaptist, Antitrinitarian, Orthodox, Greek Catholic, Hussite, Muslim and Jewish Europeans lived. Some maps show states that offered legal rights to more than one religion and regions with a mixed religious demography using multi-coloured stripes or overlapping blotches of different colours. The viewer might well be drawn to worry that such places would be unlikely to enjoy peace and stability until they could match the comforting monochrome of their neighbours.

How helpful are these maps in depicting the reality of lived religion after the Reformation? Comparing maps in different books quickly reveals startling inconsistences and inaccuracies. Placing these maps alongside one another only leads to confusion as religious communities appear in different locations for no apparent reason. Even the more accurate maps struggle to represent in any meaningful way the dynamic and fluid character of religious life in Reformation Europe. How could any map precisely chart the place of different religious communities in France or the Netherlands across the middle decades of the sixteenth century? Or what colour scheme could be deployed to show exactly where Utraquists, Bohemian Brethren, Lutherans and Catholics lived in the Czech lands?

The religious situation in Europe about 1560, The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1923. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The religious situation in Europe about 1560, The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1923. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.These maps also tend to present a number of entirely misleading impressions to viewers. For example, maps convey the notion that all Protestants (or Lutherans or Calvinists) belonged to a single European community marked in the same colour while ignoring divisions both between and within these traditions. Maps can also bolster the notion that the religious frontiers of Europe were determined by state borders and the legal powers of monarchs. The Reformation was never a process determined only by those who held political power. The presence of minority communities is often overlooked or under-represented. Many people worshipped in churches or in homes despite the lack of any legal right to do so. Even where communities outwardly conformed to a state church, turning “Catholics” into “Lutherans” was for example a very slow and individualised process of spiritual and cultural persuasion.

Religious balance of Europe at the end of the 16th century. CortoFrancese, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Religious balance of Europe at the end of the 16th century. CortoFrancese, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.State borders also offer entirely unreliable markers in many contexts of where a Protestant world ended and a Catholic world began. Local people in borderlands proved adept at turning circumstances to their advantage- travelling across borders to attend their church of choice, or using liminal spaces to ignore the demands of all priests and ministers. Religious identities were framed by royal decrees and state borders, by linguistic communities, and also by individual decisions taken within neighbourhoods and families. Over time, the combined and consistent efforts of state authorities and clergy hierarchies could enforce uniform religious practice and instil a clear sense of collective religious identity in communities living within stable boundaries. However, the notion that people of different religions mostly lived apart from one another simply never came into existence in many areas across Europe. We should not be fooled by maps into underestimating the degree to which Protestant and Catholic societies remained intertwined sometimes in relative peace and sometimes leading to outbreaks of communal violence.

As we approach the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, we might do well to doubt the capacity of maps to offer any sort of reliable depiction of Europe’s religious life. Or, at least, viewers might be drawn by such maps into thinking about the porosity and rigidity of borders, the particular nature of borderlands, about shared spaces and contested spaces, about overlapping identities and rival identities, and about the complex ways in which individuals, families and communities related to churches and states, and about the role of ordinary European women and men as well as kings, princes, bishops and reformers in shaping the character of being a “Catholic” or a “Lutheran” or a “Calvinist” or a “Protestant” after the Reformation.

Featured Image credit: Europe around 1560, The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1923. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Mapping Reformation Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

A national legacy of bullying

In the 1990s a rash of school shootings changed the landscape of American childhood. Research eventually revealed that they all had one characteristic in common: the shooters had all been victims of bullying. Suddenly, bullying, an activity that had been more or less ignored for centuries, or praised as a way of toughening up the next generation, took the spotlight as a source of personal misery and potential public menace. These researchers fell in line behind the grandfather of bullying research, the Swedish psychologist Dan Olweus, who, decades earlier discovered that school bullying victims suffered from crippling psychological sequelae including lifelong depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem.

I have devoted most of my academic career to studying and writing about bullying and shame. I strongly believe that the aggression that goes on between bullying populations and vulnerable minorities (homophobia, racism, misogyny) resembles child bullying in its shame-centered motivation and toxic results. The shame comes from the universal desire to belong to a group, either explicit (church congregations, country clubs, the Boy Scouts,) or implicit (children who are good students, adults in midlife transition) and the membership being denied to them. A middle school bully might call his victim a baby, suggesting that he is not mature enough to belong to a cohort of 6th graders. A real estate broker might steer a black couple away from a white neighborhood, suggesting that they wouldn’t feel comfortable there. In either case the victim or victims have been shamed through exclusion from a group.

The most important group for which belonging and exclusion are most primally felt is, to paraphrase Bertrand Russel, the group of all groups, the “uberkultur,” or the “dominant culture.” Most people yearn to be successful within the uberkultur, the exceptions being the nonconformists—the beatniks, hippies, creators of deviant art, hermits. One’s relationship to the uberkultur, however, inevitably informs many types of behavior both individually and collectively.

My grandfather emigrated from a shtetl in Lithuania at the age of 15, and by the time I was born, he had achieved the American Dream. He was president of a profitable newspaper distribution company, owned a Lincoln Continental and had a black chauffeur—a schwartze, as he called him—on his payroll to drive him back and forth to work. I recall during the late 1950s and early ‘60s, hearing my grandparents discussing the predicament of the schwartzes with my parents and uncles and aunts. Despite their sympathies for the Civil Rights movement, a tone of self-congratulation might creep into the discussion, pride in all that my grandparents and their children had achieved in a relatively short time, as opposed to the meager gains of the schwartzes, who had come to America long before them.

If the United States is truly sorry about these centuries of the bullying of blacks, and allowing or encouraging the bullying to take place, several acts are in order.

I knew there was something wrong with this comparison of immigrant Jews and African-Americans but as a seven-year old child, I could never quite put my finger on it.

Fifty years later, I came across the work of John Ogbu, an African-born educator who taught for many years at UC Berkeley. Ogbu had encountered the kind of negative comparisons that my grandparents sometimes made. He wrote that it was not so much the people themselves, their biology or their intellect, that was responsible for the success they had achieved—or failed to achieve—when transplanted, but the role in which history had cast them. Immigrant minorities who came voluntarily, seeking political or religious asylum, or better economic prospects, came with an idealistic vision of their future. They had a goal to work towards that spanned generations. Caste-like minorities, on the other hand, “grow up firmly convinced that one’s life will eventually be restricted to a small and poorly-rewarded set of social roles,” in the words of the well-known German Jewish psychologist Ulric Neisser. Such a future inspires neither ambition among adults nor academic commitment among children. Ogbu hypothesized that the situation could lead to a kind of “cultural inversion,” which would involve rejecting behaviors that represent the culture of the dominant group, or “acting white.”

So many of the blacks embedded in American culture might constitute a group that has no wish to belong to the uberkultur, because the uberkultur had bullied them and their ancestors for generations denying them educational opportunities, hiring them less frequently than light skinned competitors, paying them poorer wages, forcing them to live in ghettoes because of racist real estate practices, incarcerating them at rates vastly out of proportion to their lighter skinned counterparts, and so forth.

If the United States is truly sorry about these centuries of the bullying of blacks, and allowing or encouraging the bullying to take place, several acts are in order. An official apology, a promise that it will never happen again, a closer watch and a stronger hand toward those who would violate the civil rights of people of color, and finally and most importantly, reparations, whether in the form of tax abatements, affirmative action, or even direct payment.

I’m sorry I never had an opportunity to explain this to my grandfather. I would have pointed out that blacks in America probably feel the way he would had he been unable to emigrate from Lithuania and been forced to live under the rabid antisemitism of the Russian Czars.

It’s not the perfect analogy but I think he would have understood.

Featured image credit: graffiti art street by HypnoArt. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post A national legacy of bullying appeared first on OUPblog.

Bracing for the worst flu season on record

This year, 2017, is braced to historically be the worst flu season ever recorded, according to the Nation Health Service (NHS). Doctors and hospitals may struggle to cope with the increase in demand, following the spike of influenza cases from Australia and New Zealand, who have recently come out of their winter season.

With three classified types of influenza, A, B, and C, it is A and B viruses which cause the large outbreaks. In Europe, nearly all seasonal flu is attributed to influenza A. This year there have been over 170,000 influenza cases, nearly three times the amount compared to last year. Vaccination is an important part of protecting against the flu, especially with the record high amount of cases already reported this season. Research is also now suggesting that being in a positive mood, as well as genetics, can increase the effectiveness of the flu vaccination.

Hover over each icon below to learn more about influenza.

Featured image credit: Sneeze by Mojpe. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Bracing for the worst flu season on record appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers