Oxford University Press's Blog, page 319

September 28, 2017

The soldier and the statesman: A Vietnam War story

“He’s had it. Look, he’s fat and he’s not able to do the job.” “He’s shown no imagination. He’s drinking too much.” We need to “send someone over there as a cop to watch over that son-of-a-bitch.” “I have no confidence” in him. “I think he’s run his course.”

These remarks—excerpts from conversations between President Richard M. Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger—left little doubt about how the White House’s inner circle viewed the top U.S. general in Vietnam, General Creighton Abrams. The dialogue, while coarse, nonetheless paints a crucial aspect of the Nixon administration’s attempts to withdraw from Vietnam in a way that achieved what it hoped would be “peace with honor.” In short, a dysfunctional relationship between the White House and the U.S. military headquarters in Saigon undermined the coordination and advancement of U.S. military strategy during the years of American withdrawal from South Vietnam.

Nixon’s aims of maintaining pressure on Hanoi while reducing the U.S. presence in South Vietnam surely required subtlety. The implementation of this delicate military strategy, however, foundered in an atmosphere of distrust, cynicism, and outright hostility between soldier and statesman. By 1972, Richard Nixon’s relations with Creighton Abrams had reached the nadir of Vietnam era civil-military affairs. But that wasn’t how it was supposed to be.

Abrams’s replacement of William Westmoreland in June 1968 promised improved relations between Washington and Saigon. The following year, journalists trumpeted that the new military chief was displaying “considerable brilliance in conducting the war.” The general surely appeared aggressive enough. Abrams’s guidance spoke of expanding “spoiling and pre-emptive operations” against the enemy and of striking “crushing blow[s]” to “defeat him decisively.”

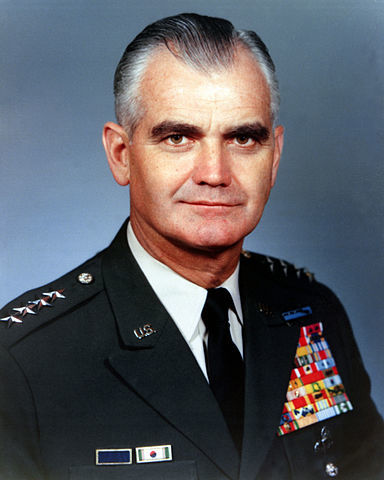

Image credit: “General William Westmoreland, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army.” from from the United States Defense Visual Information Center, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “General William Westmoreland, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army.” from from the United States Defense Visual Information Center, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Abrams may have improved American tactics by profiting from his predecessor’s own mixed experiences, but he was unable to link any military successes to the more important goal of political stability inside South Vietnam. As Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker admitted in January 1969, “very little progress has been made toward the development of a strong and united nationalist political organization….While popular support for the government has improved, it is still not strong enough.”

This lack of political progress weighed heavily on Nixon. Even before assuming the presidency, he recalled, Nixon believed in a fundamental premise that “total military victory was no longer possible.” Thus, the White House sought a broad strategic approach that rested on several key components: Vietnamization, which aimed at the South Vietnamese governing and defending themselves; pacification, with a focus on local village security; diplomatic isolation of North Vietnam; peace negotiations in Paris; and a gradual withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam. As Nixon acknowledged, “all five elements of our strategy needed time to take hold.”

Certainly, balancing all these tasks—many at odds with one another—was no easy task. Abrams had to consider troop reductions in relation to the enemy threat, the status of negotiations, the improvement of the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN), and the Saigon government’s confidence in “going it alone.”

Yet perhaps most importantly, Nixon’s withdrawal plans hinted at deep civil-military divisions inside the U.S. policymaking apparatus. Abrams balked at further troop withdrawals on the eve of the 1970 Cambodian campaign, arguing that military progress was critical to maintaining Vietnamese confidence and political stability, key prerequisites for an American departure.

One year later, after the botched incursion into Laos, a frustrated Abrams told the press that the “obtuse messages he was receiving from Washington were no less nonsensical than some of the messages correspondents in Vietnam were receiving from their home offices.” The trust between military and civilian leaders was quickly breaking down. So displeased was Nixon with Abrams’s performance that he considered relieving him of command.

In the spring of 1972, the North Vietnamese launched their Easter Offensive aimed at crippling the southern regime. Once more, Abrams’s performance provoked frustration at the White House. Once more, Nixon considered relieving the general.

Arguably, American civil-military relations between 1969 and 1972 reached their lowest point of the entire Vietnam War. Even compared to the dysfunctional relationship between Lyndon Johnson and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the animosity that Nixon held for his principal field commander was unmatched in intensity and in injury to the overall war effort.

In the eyes of the president and his national security advisor, Abrams had failed to balance the oft competing requirements of military operations, Vietnamization, pacification, and U.S. troop reductions.

More importantly, though, America’s final years in Vietnam suggest that civil-military relations are apt to be more contentious during strategic withdrawals from wars with no clear-cut endings. As one U.S. Army colonel quipped in early 1971, “It’s hard to look good when you’re walking out of a war backwards.”

Featured image credit: Sunset on Thu Bon river, Hoi An, Vietnam by Loi Nguyen Duc. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr .

The post The soldier and the statesman: A Vietnam War story appeared first on OUPblog.

September 27, 2017

Five things you didn’t know about “Over the Rainbow”

“Over the Rainbow,” with music by Harold Arlen and E. Y. “Yip” Harburg, is one of the most beloved songs of all time, especially as sung by Judy Garland in her role as Dorothy Gale in the 1939 MGM film The Wizard of Oz. The song itself is familiar all over the world. But some things you probably didn’t know:

1. Before Arlen and Harburg wrote this ballad in June 1938, another composer on MGMS’s staff named Roger Edens had drafted a totally different song for this place in the screenplay, a jaunty tune in which Dorothy celebrates the values of her home in Kansas rather than a magical land somewhere else. Its refrain went:

Mid Pleasures and palaces

In London, Paris, and Rome,

There is no place quite like Kansas

And my little Kansas home-sweet-home.

2. “Over the Rainbow” was cut during previews of The Wizard of Oz in June 1939 because Louis B. Mayer, the studio chief, felt it slowed up the film and that no one would want to hear a girl sing a slow ballad in a farm yard. The associate producer, Arthur Freed, a key figure on the film’s staff, told Mayer, “’Rainbow’ stays—or I go!” “Rainbow” stayed and went on to become the film’s most popular song.

image credit: “Judy Garland Over the Rainbow 2” Trailer Screenshot, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

image credit: “Judy Garland Over the Rainbow 2” Trailer Screenshot, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.3. Less than a year after The Wizard of Oz premiered, MGM used the song again in another film, the social comedy The Philadelphia Story. Katherine Hepburn, playing a wealthy socialite on the eve of her wedding, and James Stewart, a tabloid reporter sent to get a scoop on the event, share a drunken midnight swim at her family estate. As he carries her back to the house, Stewart sings a garbled version of the song:“Some day over the rainbow,” he croons, much to the delight of a groggy Hepburn.

4. “Over the Rainbow,” though a very serious number, has been subjected to numerous parodies, including by Judy Garland herself. On October 8, 1944, at a dinner for the Hollywood Democratic Committee, accompanied by Johnny Green at the piano, she sang a version in which the opening melody had the ill-fitting lyrics:

The Democratic Committee

Loves you so.

You’re cute, you’re smart, and you’re pretty,

Also we need your dough.

In the decades since, “Over the Rainbow” has been subject to many more parodies. In one YouTube video, a man plays the tune on an “organ” comprised of differently pitched stuffed cats. In a different video, Judy Garland’s original scene from The Wizard of Oz is given a death metal voice over.

5. “Over the Rainbow” has also been a source of solace and reassurance at times of trouble. In January 2013 the singer-songwriter Ingrid Michaelson assembled a group of children from Newtown, Connecticut, to sing “Over the Rainbow,” just weeks after the killings at Sandy Hook Elementary School. The message was one of rootedness, of determination that they would not allow their community to be disrupted by the act of a crazed shooter. In a similar spirit, on June 4, 2017, the pop star Ariana Grande sang “Over the Rainbow” as the encore at her One Love Manchester concert in England. A benefit for victims of the recent suicide bombing at that city’s arena, the event was attended by 50,000, and broadcast and live-streamed to millions more worldwide. Members of the mostly young audience wept during the number, and Grande herself almost broke down in the coda.

Featured image: “Streamers” by Nicholas A. Tonelli. CC by 2.0 via Flickr .

The post Five things you didn’t know about “Over the Rainbow” appeared first on OUPblog.

Etymology gleanings for September 2017

It has been known for a long time that the only difference between borrowing and genetic relation is one of chronology. Engl. town once meant “enclosure,” as German Zaun still does. Russian tyn also means “fence.” There is a consensus that the Russian word is a borrowing from Germanic because t in Germanic corresponds to d outside this language group (by the so-called First Consonant Shift). The native Russian word would have been dyn. Let us go one step farther. We also have Old Irish dūn “fort” (another enclosed area). Germanic dūn (the form that must have existed before its d changed to t) was probably borrowed from Celtic before the Shift. Yet there is no certainty, since a cognate would have sounded the same (no shift separates Celtic from Slavic).

A correspondent asks why English cnāwan “to know” could not be borrowed from a Greek word having the root of gnósis and undergo the shift in Germanic. Of course it could. But in the process of reconstruction, borrowing, like any other event, should be supported by evidence. We have no prehistoric Germanic words taken over from Classical Greek. Such an abstract notion as “knowledge” would have been borrowed only by “thinkers.” However, the earliest loanwords invariably pertain to the sphere of material objects. Every time we suggest borrowing we have to trace the route of the word from one community to another and explain what caused the interaction of two cultures. In this case, nothing testifies to the existence of Greek-Germanic contacts. It follows that cnāwan is related to, rather than being a borrowing of, the Greek word and is part of the Indo-European stock.

Knowledge can be transferred and borrowed, but the English word knowledge is native.

Knowledge can be transferred and borrowed, but the English word knowledge is native.Fake: etymology

See the post for 23 August 2017. It has been pointed out to me that the origin of fake is no mystery because we have fake “…the arts of coiling ropes and the hair dresser are kinds of skillful arrangement. In music that’s improvisation. From these contexts the word is extended to contexts where the implication is that the faker intends deception.” I am fully aware of the fact that as early as 1627 the noun fake turned up with the sense “a loop of a coil (as of ship’s rope or a fire hose) coiled free for running.” The path from that sense to “deception” is not clear to me: there is nothing fake in that coil. Also, “our” fake emerged two centuries later. In my opinion, it is a homonym of fake “coil.” In any case, the origin of fake “coil” should also be explained. If my idea that most f-k verbs in Germanic (including our F-word) refer to moving up and down or back and forth, fake “coil” receives a natural explanation. Fake “pilfer” also refers to the sleight of hands. The details are lost, but the general outline is not beyond reconstruction. Conversely, all attempts to derive fake and the F-word directly from Latin should be discarded. I should especially warn everybody against such words and phrases as “certainly, undoubtedly, I have no doubt,” and their likes. In etymology, we are on slippery ground, and caution (doubt) is recommended.

Nothing is fake about this coil except for its name.

Nothing is fake about this coil except for its name.Sound imitation: tantrum and thunder

If my suggestion that tantrum is an onomatopoeic word (see the post for 6 September 2017) is worth anything, tantara, tarantara, etc. are next of kin. Engl. thunder, is naturally, related to Latin tonāre, which too may be sound-imitating. The same holds for drum. It is not entirely clear whether the word came from French. Trumpet, a Romance word, is drum’s next door neighbor.

This is a tam-tam, an etymological relative of drum, and possibly of tantrum.

This is a tam-tam, an etymological relative of drum, and possibly of tantrum.Spelling Reform

I fully agree with Masha Bell that, if one country institutes the Reform, other countries may follow suit. This did not happen when the US introduced a few sensible changes, for every other country remained true to its conservative norm. But the example Masha Bell cites (Portugal learning from Brazil) inspires confidence. The Swiss reformed the spelling of some words long ago, and now Germany partly adopted the Swiss model. Let us hope that the reformers in the English-speaking world will stop talking about organizational matters and finally organize something.

Intonation

It is true that Engl. there you go (in any sense) and Danish vær så god “please” are intoned alike. This “music” probably characterizes many three-word phrases (not at all, if you please, and the like). The British and the Danish “parting formulas” also share the element of formal politeness. This factor may contribute to the way they are pronounced.

Old Business

I have received questions about the origin of the words bug and sure. Both have been discussed in this blog. For bug see the post for 3 June 2015, and for sure and sugar see the post for 16 November 2011.

The way we write

♦A bit of a cold shower, or the last frontier of brainlessness. Here is the definition of douche in Urban Dictionary: “A word to describe an individual who has shown themself to be very brainless in one way or another.” A rum customer indeed. ♦From a student newspaper: “It’s easy to sleep on what feel like lost relationships, but it’s perfect time to take actions.” The writer was seduced by the plural relationships (hence what feel; actions for action also sounds strange, or weird, as students usually say), but many English speakers experience at least some inconvenience when asked whether they prefer our only guide was the stars, my only joy was books or our only guide were the stars, my only joy were books. Grammar books recommend the singular (in German, the plural would be the norm in such cases). Be that as it may, but what feel is questionable grammar, to say the least.

Twinkle, twinkle, little stars (and be our guide).

Twinkle, twinkle, little stars (and be our guide).♦On both sides of the Atlantic. The magazine sent to the alumni of Cambridge University is always full of interesting articles, but it can also be mined for grammar. Although the following excerpt is from a statement by an American professor, it does not seem to have inconvenienced the British editor (Easter, 2017, p. 35): “Globalisation—for example, rising imports from Chana—bring a lot of benefits.…” The speaker (or writer) thought of the plural imports, though the subject is globalization (spelled the British way). The sentence partly follows my favorite model (not cognate with but borrowed from a student’s paper): “The mood of the stories are gloomy.” The next statement will probably find favor with most: “Or when there’s only one wage-earner, and they lose their job….” Very gender-neutral and proper. However, when one wage-earner lose their job, I feel slightly confused. By contrast, I was delighted to read on p. 3: “While it [a certain composition] shares with the fugue the principal of ‘contrapuntal imitation’….” If they can spell so at Cambridge, don’t we need at least some version of spelling reform? What about introducing the word principl or even prinsipl for both situations? Finland is celebrating the hundredth anniversary of its independence. That is the land in which spelling is a dream! But then the Finnish language has fifteen cases, while English has none. Nothing in the world is perfect.

A land of saunas ans sisu? Yes, of course, but also the land of perfect spelling and fifteen cases.

A land of saunas ans sisu? Yes, of course, but also the land of perfect spelling and fifteen cases.The post Etymology gleanings for September 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

Race in America: parallels between the 1860s, 1960s, and today [extract]

The American Civil War remains deeply embedded in our national identity. Its legacy can be observed through modern politics—from the Civil Rights Movement to #TakeAKnee. In the following extract from The War That Forged a Nation, acclaimed historian James M. McPherson discusses the relationship between the Civil War and race relations in American history.

The civil rights movement eclipsed the centennial observations during the first half of the 1960s. Those were the years of sit-ins and freedom rides in the South, of Southern political leaders vowing what they called “massive resistance” to national laws and court decisions, of federal marshals and troops trying to protect civil rights demonstrators, of conflict and violence, of the March on Washington in August 1963, when Martin Luther King Jr. stood before the Lincoln Memorial and began his “I have a dream” speech with the words “Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been scarred in the flame of withering injustice.” These were also the years of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which derived their constitutional bases from the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments adopted a century earlier. The creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau by the federal government in 1865, to aid the transition of four million former slaves to freedom, was the first large-scale intervention by the government in the field of social welfare.

These parallels between the 1960s and 1860s, and the roots of events in my own time in events of exactly a century earlier, propelled me to become a historian of the Civil War and Reconstruction. I became convinced that I could not fully understand the issues of my own time unless I learned about their roots in the era of the Civil War: slavery and its abolition; the conflict between North and South; the struggle between state sovereignty and the federal government; the role of government in social change and resistance to both government and social change. Those issues are as salient and controversial today as they were in the 1960s, not to mention the 1860s.

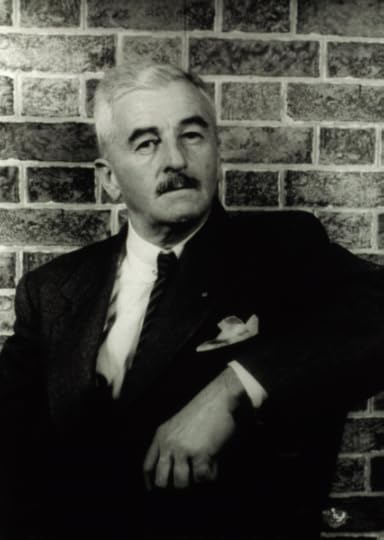

Southern novelist William Faulkner once said: “The past is not dead; it is not even past.” Image credit: Author William Faulkner by Carl Van Vechten via US Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Southern novelist William Faulkner once said: “The past is not dead; it is not even past.” Image credit: Author William Faulkner by Carl Van Vechten via US Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In 2015 we [had] an African American president of the United States, which would not have been possible without the civil rights movement of a half century ago, which in turn would not have been possible without the events of the Civil War and Reconstruction era. Many of the issues over which the Civil War was fought still resonate today: matters of race and citizenship; regional rivalries; the relative powers and responsibilities of federal, state, and local governments. The first section of the Fourteenth Amendment, which among other things conferred American citizenship on anyone born in the United States, has become controversial today because of concern about illegal immigration. As the Southern novelist William Faulkner once said: “The past is not dead; it is not even past.”

Let us take a closer look at some of those aspects of the Civil War that are neither dead nor past. At first glance, it appeared that Northern victory in the war resolved two fundamental, festering issues that had been left unresolved by the Revolution of 1776 that had given birth to the nation: first, whether this fragile republican experiment called the United States would survive as one nation, indivisible; and second, whether that nation would continue to endure half slave and half free. Both of these issues had remained open questions until 1865. Many Americans in the early decades of the country’s history feared that the nation might break apart; many European conservatives predicted its demise; some Americans had advocated the right of secession and periodically threatened to invoke it; eleven states did invoke it in 1861. But since 1865 no state or region has seriously threatened secession. To be sure, some fringe groups assert the theoretical right of secession, but none has really tried to carry it out. That question seems settled.

By the 1850s the United States, which had been founded on a charter that declared all men created equal with an equal title to liberty, had become the largest slaveholding country in the world, making a mockery of this country’s professions of freedom and equal rights. Lincoln and many other antislavery leaders pulled no punches in their denunciations of both the “injustice” and “hypocrisy” of these professions. With the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865, that particular “monstrous injustice” and “hypocrisy” has existed no more. Yet the legacy of slavery in the form of racial discrimination and prejudice long plagued the United States, and has not entirely disappeared a century and a half later.

In the process of preserving the Union of 1776 while purging it of slavery, the Civil War also transformed it. Before 1861 “United States” was a plural noun: The United States have a republican form of government. Since 1865 “United States” is a singular noun: The United States is a world power. The North went to war to preserve the Union; it ended by creating a nation. This transformation can be traced in Lincoln’s most important wartime addresses. His first inaugural address, in 1861, contained the word “Union” twenty times and the word “nation” not once. In Lincoln’s first message to Congress, on 4 July 1861, he used the word “Union” thirty-two times and “nation” only three times. In his famous public letter to Horace Greeley of 22 August 1862, concerning slavery and the war, Lincoln spoke of the Union eight times and the nation not at all. But in the brief Gettysburg Address fifteen months later, he did not refer to the Union at all but used the word “nation” five times. And in the second inaugural address, looking back over the trauma of the past four years, Lincoln spoke of one side seeking to dissolve the Union in 1861 and the other side accepting the challenge of war to preserve the “nation.”

Featured image credit: “Battle of Antietam” color lithograph, circa 1888. Published by Kurz & Allison, Art Publishers. Restored by Michel Vuijlsteke. Courtesy of the US Library of Congress. Public domain via

Wikimedia Commons.

The post Race in America: parallels between the 1860s, 1960s, and today [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

Mahbub ul Haq: pioneering a development philosophy for people

Mahbub ul Haq was the pioneer in developing the concept of human development. He not only articulated the human development philosophy for making economic development plans but he also provided the world with a statistical measure to quantify the indicators of economic growth with human development.

In the field of development economics, Haq was regarded as an original thinker and a major innovator of fresh ideas. He was listed in a book as one of the fifty key thinkers on development, along with such greats as Karl Marx, Thomas Malthus, and Mahatma Gandhi. (David Simon, Fifty Key Thinkers on Development, London, Routledge, 2006)

Haq shaped the development philosophy and practice in the four decades from the 1960s to 1990s, shifting the focus of development discourse from national income growth to people and their well-being, monitoring its progress through the Human Development Index (HDI). He initiated a global movement involving policymakers, scholars, and activists to adopt Haq’s innovative ideas for people-centred development.

The force of Haq’s ideas and passion, compelled his audience, particularly the South Asian policymakers, to look deeply into the reasons behind the disconnect between economic growth and people’s well-being. Despite holding high-level offices in national and international organizations, Haq never shied away from telling the truth and raising concerns about taboo subjects such as the rising costs of military expenditure, wasting resources of poor countries on the nuclear race, and the lack of development cooperation within South Asia. Haq firmly believed that South Asia could become the next economic frontier of Asia if acute differences were settled and a free flow of rich customs, commerce, and ideas encouraged. He defined a vision and a plan of action for creating greater unity among the South Asians. He tirelessly advocated for peace between India and Pakistan; investments for education and health for all people without any discrimination based on gender, income, location, and other factors; empowering South Asian civil societies with training and resources; and work toward an integrated economy in South Asia.

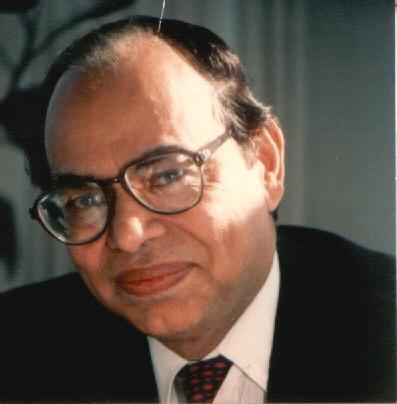

Mahbub-ul-Haq by Snaim (30 January 2008). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Mahbub-ul-Haq by Snaim (30 January 2008). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Globally Mahbub ul Haq’s legacy of humanizing economics by giving a human face to economic development, and bringing poverty concerns to the centre stage of the development agenda will long endure. So will his concerns for income and capability gaps between the rich and poor within and among nations. Haq untiringly advocated for better development cooperation for the 21st century, a less brutal process of globalization, a system of global institutions that will protect the vulnerable people and nations, a cut in military spending to free resources for social development, a more transparent and ethical national and international system of governance, and a compassionate society. His legacy is also that he seldom talked about issues without providing a concrete point by point blueprint for action.

But Mahbub ul Haq’s finest legacy is his intellectual courage. Wherever he worked, whatever job he held, he never shied away from telling the truth. He was always fighting for the voiceless, the marginalized, oppressed millions against a system that is unjust, unethical, corrupt and anti-people.

I would like to end this of by quoting a few lines from Prof Amartya Sen, who was a close friend, talking about Mahbub ul Haq.

“Mahbub ul Haq as a person was much larger than all the parts that combined to make him the person he was. He was, of course, an outstanding economist, a visionary social thinker, a global intellectual, a major innovator of ideas who bridged theory and practice, and the leading architect in the contemporary world of the assessment of the process of human development. These achievements are justly celebrated, but, going beyond the boundaries of each, this was a human being whose combination of curiosity, lucidity, open-mindedness, dedication, courage, and creativity made all these diverse achievements possible.”

Featured image credit: Punjab University by Hafizabadi. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia commons.

The post Mahbub ul Haq: pioneering a development philosophy for people appeared first on OUPblog.

The death of secularism

Secularism is under threat.

From Turkey to the US, India to Russia, parts of Europe and the Middle East, secularism is being attacked from all sides: from the left, from the right, by liberal multiculturalists and illiberal totalitarians, abused by racists and xenophobes as a stick with which to beat minorities in diverse societies, subverted by religious fundamentalists planning its destruction.

But perhaps the biggest enemy of secularism today is ignorance. Although secularism has been of fundamental importance in shaping the modern world, it is not as well-known a concept as capitalism or social welfare or democracy. You won’t find it commonly studied in schools or even at universities. In these days, when all the implicit assumptions of modernity are under strain, this is a dangerous situation. Reasonable debates about secularism on the basis of a shared understanding of it, what it means, and where it came from, are in short supply.

Secularism is the idea that state institutions should be separate from religious ones, that freedom of belief and thought and practice should be an automatic right for all (unless it interferes with the rights of others), and that the state should not discriminate against people on grounds of their religious or nonreligious worldview. Although it is often seen as a modern and western idea, it is a global phenomenon with roots in the past. Secularism was first brought into law in eighteenth century France and America. In the West it has intellectual origins from varying sources; in pre-Christian European examples of government separated from religion in practice, in Christian political philosophy, and in post-Christian ideas about deriving government from the consent of the governed rather than from gods. Secularism also has roots in Asia, where Hindu, Buddhist, and Muslim thought all produced justifications for governments to treat the governed fairly regardless of religion. Classical Indian philosophy produced ideas of statecraft that owed nothing to religion at all, and colonial encounters produced new versions of secularism.

Today secularism is a feature on paper, at least for countries like India, the US, France, and Turkey. All the states that have adopted a secular system have done it in their own way, according to the nature of their own particular society and their religious, cultural, and political history. Even so, the arguments made for secularism in almost all times and places have been similar. It has advanced as the system best able to secure freedom and justice and fairness. It is promoted as the best system to avoid sectarian conflict and strengthen peace. It is cast as a pathway to modernity. Even in societies which are not secular on paper, these assumptions have often prevailed in practice, with government in liberal democracies increasingly relying on a de facto secularism in the conduct of government, which makes no laws on religious arguments alone and expects fair treatment of citizens regardless of their creed. This is even sometimes true of countries with very strongly established churches, like England and Denmark.

Although secularism has been of fundamental importance in shaping the modern world, it is not as well-known a concept as capitalism or social welfare or democracy.

But just like secularism itself, the attacks on it are a global phenomenon and they also have deep historical roots.

The oldest and most obvious alternative to secularism is government based on divine laws. If you believe your religion is true and your religion is one of the monotheistic ones that make exclusive truth claims, you can easily think that your state should be entirely based on your religion alone. Such ‘nations under God’ are at odds with all three aspects of secularism. Firstly, there is no question of the separation of religious institutions from state institutions: they are one and the same. Secondly, freedom of conscience for non-adherents of the state’s religion, if it is provided at all, is provided only insofar as the religion of the state concedes it. Thirdly, in place of equal treatment, the state favours its own religion in its dealings with society. Full on theocracy is long dead in the West and in the mid-twentieth century it seemed to be dying out everywhere, as even the most religious societies on earth began paying at least lip-service to secularism. It seemed then that the politics of the future would be secular across the globe. The big shock to this assumption was the Islamist revolution in Iran in 1979, which overturned what had been seen as an emerging exemplar of secularism.

Optimistic secularists in the late twentieth century viewed Iran as no more than a blip. Yet the strain that the secularism of states in Asia, such as Bangladesh, has come under more recently offer a mounting challenge to the idea that it can provide a successful political order everywhere. In Turkey, the religious political party of President Erdogan is rolling back the frayed remains of laiklik (Turkish for secularism) as fast as it can. In India, the Hindu nationalist movement of Prime Minister Modi alienates non-Hindu citizens and tacitly condones persecution of them. In the US, the ethnic nationalists that froth around the Trump administration seek to reinvent the US as a ‘Judeo-Christian’ state. In Russia and many countries of Eastern Europe, illiberal governments are breathing new life into the old alliance of autocracy and the Orthodox Church as they laud priests and patriarchs with honours and ply them with public funds. In the Arab world, the people’s desirable alternative to dictatorship is too often now seen as an Islamic state rather than a secular democracy.

Perhaps the most beguiling critics of secularism are the relativistic Westerners who now suggest that it might all along have been a parochial Christian and European imposition on the world, destined to fail. It wasn’t, and it probably won’t, but it does face enormous challenges. We will only be able to understand the shape and nature of these challenges if we learn again to see secularism not just as some implicit fact of modernity, but as a concept worthy of study in its own right and on university syllabuses and post graduate research topics.

After all, the foundations of freedom in the world today — freedom of speech, freedom of thought — are built upon secularist principles.

Featured image credit Equality Demonstration Paris by Vassil. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The death of secularism appeared first on OUPblog.

Following the trail of a mystery

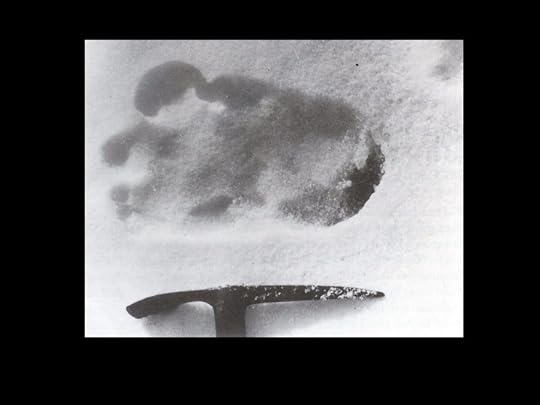

What would you think, when crossing a Himalayan glacier, if you found this footprint? Clearly some animal made the mark.

SHIPTON 1951 PHOTO (By Permission: Royal Geographical Society, Eric Shipton Photographer)

SHIPTON 1951 PHOTO (By Permission: Royal Geographical Society, Eric Shipton Photographer)This print is in a longer line of tracks, and shows not just one animal. The print looks like a person’s … but that gigantic toe on what is a left foot has the arch on the outside of the foot. Big toe on one side, the arch on the other, three tiny toes? And the longer line of footprints suggests that a family of mysteries walked the route.

Moreover, the ice-axe shows the footprint is 13 inches long. Did a family of giants walk this way? Sharp footprints on a glacier where no village or caravan route is within days of walking, found by a reputable explorer (Eric Shipton). In 1951, when these footprints were found, they gave proof to the long-standing puzzle of the Yeti or Abominable Snowman.

Yak Caravan by Daniel C. Taylor, used with permission by author.

Yak Caravan by Daniel C. Taylor, used with permission by author.As an eleven-year old, I also found these photographs. Our home was in the Himalaya, and I began searching the mountains. For three decades, I, along with others, kept discovering footprints. Frequently, discoveries were in the region around Mount Everest. We repeatedly found prints in differing sizes over what came to span a century. From this grew a body of evidence that has been subjected to scientific scrutiny, time and again. These prints are not a hoax, but trails left by real animals.

Is the animal a primate like a gorilla yet to be discovered? Or, some relative of the giant panda? With the astonishing human-like feet, is the animal a relic of some prehistoric human population? Does a known animal make such footprints when in the snow? The footprints are being found at high-altitudes, where the oxygen is one-third that of sea level.

The challenge for me (and all of us who were searching) was that the trails always disappeared onto rock at the edge of glaciers. Our discoveries were always at best several hours behind the print making. We never found an animal making these trails. The mystery marched on across decades.

Then in the densest jungle in the Himalaya—the Barun Valley east of Mount Everest—when searching in the winter when snow was on the ground, we found footprints, and these footprints could be followed. They led not onto rocks, but up trees. Up in the trees we found huge nests where the animal slept. In the nests we found stiff black hairs, and the hairs could be identified: bear.

Villagers living on the periphery of these jungles said, “Yes, we have bears living in trees; they are smaller. We also have big bears; they live on the ground.” The mystery of trails in the snow became a mystery of what lived in the trees—and this was a mystery because science said all Himalayan bears lived on the ground. The particular bear that lived in the Barun Valley was supposed to be Ursus actos thibetanus, a black bear with a white V on its chest. (Other parts of the Himalaya have a brown bear that is an Asian cousin of the North American grizzly, also a sloth bear at lower elevations.)

We acquired skulls of this bear, and it was indeed Ursus actos thibetanus. Museum study then revealed that in the 1800s there were reports of tree-living bears in the Himalaya. Might a remnant population of these never further reported bears survive in the remote Barun Valley?

Bear foot by Daniel C. Taylor, used with permission by author.

Bear foot by Daniel C. Taylor, used with permission by author.Figuring out this bear quest, however, led to a larger, more important trail: the creation of national parks to protect the jungle and mountains habitats the bears resided in. We first established Makalu-Barun National Park in Nepal, then came Qomolangma (Mt Everest) National Nature Preserve in Tibet/China. Then in the 1980s, still pristine were the valleys around Mount Everest. What followed then across Tibet was a series of huge national parks and setting aside what has now grown to over one hundred million acres of protected land.

This conservation effort was also distinctive because it evolved a new mode of nature protection, one that enabled people to live inside the parks, where community-based governance (not park wardens and police) protected the land. All this started from the Yeti search.

Perhaps most interesting about discovering the Yeti is that after a century of scientific work explaining the footprints, there’s still something missing. Yes, now we know what animal makes the footprints—the bear goes over the mountain to see what it can see or to mate—but there is another mystery.

A core search seems to lie in our human connection, affiliation, to understand the wild. We seek a missing link to where our species evolved from. With so few jungles left, is the wild gone now? Inside ourselves we want the wilderness to remain. A wild “man” of the jungle, the Yeti, remarkably can lead us to discovering a new type of wild that each of us can live in today.

Featured image credit: Expedition in high snows by Daniel C. Taylor, used with author permission.

The post Following the trail of a mystery appeared first on OUPblog.

Stoicism, Platonism, and the Jewishness of Early Christianity

The last few decades have taught us that speaking of Stoicism, Platonism, and Judaism as constituting a single context for understanding Early Christianity is not a contradiction (Stoicism and Platonism here; Judaism there), but rather entirely correct. The roots of Christianity are obviously Jewish, but in the Hellenistic and Roman periods Judaism itself was part of Greco-Roman culture, even though it, too, had its roots way back in history before the arrival of the Greeks. Thus the borderline between Judaism and the Greco-Roman world that has been assiduously policed by theologians speaking of Early Christianity has been erased. Similarly, the borderline between Greco-Roman ‘philosophy’ and Jewish and early Christian ‘religion’ has been transgressed. Hellenistic Jewish writers like the author of the Wisdom of Solomon (around 30 BCE) and Philo of Alexandria (ca. 30 BCE-45 CE) unmistakably drew quite heavily on both Platonism and Stoicism to express their Jewish message. The same has been argued––with special emphasis on Stoicism––by the present writer for the Apostle Paul and (most recently) the Gospel of John. And the Platonic colouring of another New Testament text, the Letter to the Hebrews, has been known for a long time. Thus Early Christianity no longer stands in opposition to Greco-Roman ‘philosophy.’ On the contrary, they belong in the same pool, at the same time as Early Christianity also retains its Jewish roots.

This new understanding raises a question that may be worth pondering: is Stoicism better suited than Platonism to capture, express, and articulate the Jewishness of Early Christianity? That is, can one understand why early Christian writers, like Paul and John, may have felt that Stoic ideas were more congenial than Platonic ones for bringing out their own understanding of God, Jesus Christ, the ‘Spirit’ and the meaning of these three entities for human beings?

Against this idea stand a number of considerations. First, it is far from settled that Paul and John are in fact best understood in Stoic terms. For instance, I have myself argued that Paul’s idea of the “resurrection body” as a “spiritual body” (a sôma pneumatikon) is best understood in terms of the specifically Stoic understanding of the “spirit” (pneuma) as a bodily phenomenon. This reading extends also to explaining Paul’s views of how human beings should live in the present, as prematurely informed by the pneuma (only to be fully present in them at their resurrection). Here I find a basically monistic understanding pervading all of Paul’s cosmology and anthropology. Others, however, have argued for some extent of Stoic colouring in Paul’s cosmology and ontology, but a much more Platonic colouring in his anthropology, e.g. when Paul (“dualistically”?) contrasts “our inner (human) being” with “our mortal flesh.” This is argued, for example, by Stanley Stowers in From Stoicism to Platonism.

Is Stoicism better suited than Platonism to capture, express, and articulate the Jewishness of Early Christianity?

As for John, I have myself argued, that the conjunction of logos (“rationality”, “plan”) and pneuma in John 1 is best elucidated in Stoic terms, where these constitute two sides of the same coin, one cognitive and one material––once again with wide implications for the rest of the Gospel. Others, however, have argued for a much stronger Platonic colouring of John: C. H. Dodd back in 1953 (The Interpretation of the Fourth Gospel), but also quite recently––and in a very different manner––Harold Attridge ( in From Stoicism to Platonism), who read John along a trajectory, going from the fundamentally “Platonizing” Philo of Alexandria via John to the so-called “Valentinian” (and “Gnostic”) writings from the 2nd century. So, perhaps these scholars are right?

Secondly, there is an issue of how to understand the situation within Greco-Roman philosophy in the period itself, just before and during the writing of the New Testament texts. Is it correct to see Stoicism as the leading dogmatic philosophy (at least as relevant to the Jewish and early Christian writers) and thus the type of philosophy with which writers like Paul and John might most “naturally” interact––with Platonism only gradually coming into taking that position, as it clearly did from the 2nd century onwards?

It is clear that the implications of these issues are momentous. For if a “Stoicizing” reading of Paul and John is better than a “Platonizing” one, then we must basically situate the Platonic understanding of Christianity later than the two mentioned central New Testament writers themselves. And then, apparently, there was a type of Christianity before that which was not informed by “dualistic” Platonism.

Here, however, the question to be raised is whether a “Stoicizing” reading of Paul and John is not in fact better suited than a Platonic one to capture specifically the evident Jewishness of their message? Dodd’s contemporary, the German master Rudolf Bultmann, contrasted both Paul and John with a Platonically inspired, dualistic “Gnosticism” by referring back to the Jewish roots of Early Christianity. An example is Bultmann’s reading of Paul’s use of the term “body” (sôma) as standing for “the whole person”, which Bultmann took to be a specifically Jewish idea. But it is also Stoic. So, perhaps––that is the challenge here––Stoicism is in fact better suited than Platonism to capture the very Jewishness of Early Christianity. And perhaps there in fact was a pre-Platonizing Christianity.

Featured image credit: Christ Jesus religion mosaic by Didgeman. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Stoicism, Platonism, and the Jewishness of Early Christianity appeared first on OUPblog.

September 26, 2017

Leipzig’s Marx monument and the dustbin of history

What could Karl Marx have to do with Charlottesville? At an historic moment when debates rage about the fate of memorials across much of the United States, it is instructive to explore how the politics of memory have evolved for contentious monuments on another continent. In communist East Germany, oxidized brass and copper semblances of long-deceased personages were also elevated and then, after 1989, eliminated due to connotations rooted in public traumas that transcended the man (occasionally woman) represented and honored. Perhaps one of the most controversial instances in the political lives of dead men’s monuments took place in Leipzig, East Germany’s second-largest city, on a central site which throughout the Cold War was named Karl Marx Square. Here the 33-ton bronze relief Aufbruch (its full name: Karl Marx and the Revolutionary, World-Shattering Essence of his Teachings) had been hoisted up over the main entrance of the Karl Marx University for the East German state’s twenty-fifth anniversary in 1974. After the fall of communism in 1989, some proposed smashing the Marx relief or melting it down, but in the end it was simply exiled to a remote piece of university property. Today any who seek it out can take in its historically distinctive artisanship alongside an inscription that speaks to the fraught context in which it first came into existence.

“Augusteum and University Church shortly before the demolition in 1968,” Leipzig University Archive DF 2198

“Augusteum and University Church shortly before the demolition in 1968,” Leipzig University Archive DF 2198

“Augustus Square, View to Gewandhaus, Tower, and Main Building around 1987,” Leipzig University Archive FS N4945

“Augustus Square, View to Gewandhaus, Tower, and Main Building around 1987,” Leipzig University Archive FS N4945The decision to put a gargantuan memorial to Marx on the square that bore his name took place after one of the largest instances of public protest in East German history. Despite eight years of letter-writing that peaked with crowds of dissenters on Karl Marx Square, Leipzig’s fully intact medieval University Church was dynamited on May 30, 1968 to almost unanimous applause from communist bureaucrats, modern architects, and university authorities. Although the dust settled quickly, this flagrant outrage decried as “cultural barbarism” sustained an aura of discontent up through 1989 that undermined a sense that one could ever “work with” the authorities again.

Private resentment at the loss of this local landmark only worsened as communist leaders chose to finally erect a monument to Marx as the defining symbol for the square and the city. Earlier discussion about iconography on Karl Marx Square had resulted in a short-lived monumental figure to Stalin and drafts for a monument to Walter Ulbricht (a notion that vanished as the East German dictator drifted toward retirement). Marx had already failed as a usable symbol during the university’s celebration of the great philosopher’s 150th birthday in early May 1968. So hostile was the overall atmosphere that talks had to be delivered back-to-back to deter any discussion afterward, and most students chose to ignore the festivities altogether; turnout was often so dismal that events were simply cancelled. Disconnect thus could not have been greater when at the end of festivities the city council reiterated that the new university campus was to symbolically embody “the revolutionary and world-shattering character of Marxist teachings.” As the vice-president for student affairs declared three months after the demolition, completion of a modern architectural ensemble would finally make Leipzig’s “Karl Marx University” worthy of the name of Marx. In this spirit, the bronze Marx relief was tacked over the freshly completed entrance to the university’s new main building in 1974—right where the façade of the University Church had once stood. The Marx relief signified that Marxist ideology was to form the basis of Karl Marx University for the rest of history.

“Augustus Square, View to Gewandhaus, Tower, and Main Building around 1987,” Leipzig University Archive FS N4945

“Augustus Square, View to Gewandhaus, Tower, and Main Building around 1987,” Leipzig University Archive FS N4945The verdict of history shifted radically, however, when Leipzigers marched on Karl Marx Square in 1989 and helped to trigger the fall of communist power. With Karl Marx expunged from its name, in 1993 the university posted a damning inscription on its main building commemorating the “arbitrary” destruction of the University Church and condemning the city and university for failing to “withstand the pressure of a dictatorial system.” This radically altered official reading of history was visually manifested in 1998 by a skeletal “installation” meant to recall the vanished University Church façade, superimposed over the Marx relief on the main building. When the slipshod box of the main building finally met the wrecking ball in 2007, it was a given that the Marx relief had no place on the reconfigured and renamed Augustus Square, which featured a postmodern citation of the University Church, its Gothic features suspended as if in an ether of glass and light at the very moment of their destruction.

However, this commemorative victory for the University Church ultimately did not mean destruction for Marx. In 2008 his likeness was safely banished to a remote courtyard on the university’s sport campus. And in contrast to fears that Marx might become a target for vandalism or communist nostalgia, the 1974 monument has enjoyed peaceful obscurity. The few who manage to find it benefit from a commemorative plaque whose images and stories explain just why this memorial to a monumental German philosopher was driven from the square that had once borne his name: an ignominy that had little to do with the teachings of Marx himself.

Headline image credit: Neues Rathaus in Leipzig seen from the MDR tower by Concord. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Leipzig’s Marx monument and the dustbin of history appeared first on OUPblog.

Let the world see

When Emmett Till’s body arrived at the Illinois Central train station in Chicago on 2 September 1955, the instructions from the authorities in Mississippi were clear: the casket containing the young boy must be buried unopened, intact and with the seal unbroken. Later that morning, Till’s mother, Mamie Till Bradley, instructed funeral home director Ahmed Rayner to defy this command. He objected, citing the promises he made to the state of Mississippi and the professional obligations they entailed. But again she insisted and, finally, against his better judgment, he agreed.

What Mamie Till Bradley saw next horrified her, but it also steeled her resolve and inspired one of the defining moments of the modern civil rights movement. When she told Rayner she wanted to hold an open-casket funeral for her son, he asked her to reconsider, but when she again insisted, he relented, offering to retouch the corpse to make it more presentable. “No,” she told him. “Let the world see what I’ve seen.”

Mamie Till Bradley’s decision that day—coupled with the photos of her son’s corpse that she allowed Jet magazine and the Chicago Defender to circulate throughout the black press—galvanized a generation of civil rights activists. In calling for the world “to see what I’ve seen” (or as she said in another context, “to let the people see what they did to my boy”), Mamie Till Bradley was not the first to challenge white supremacy by demanding that the nation bear witness to this ideology’s strange and necessary fruit: the wounded black body. Others before her, like the editors of Crisis during the early part of the twentieth century, understood that this witness exposed white supremacy for what it truly was: a hatred not simply dependent upon violence as an occasional tool, but one founded on violence and requiring violence for its very existence. In addition, such witness combatted the willful blindness of a nation that, because it did not want to confront the true nature of its own history, enabled this violence to flourish. What Mamie Till Bradley added to this protest tradition, and what in large part accounts for the unique place that Emmett Till’s lynching holds in our collective racial memory, is that she demanded the nation behold not just any wounded body, but a son’s body, and that it reckon with not just any pain, but a mother’s pain.

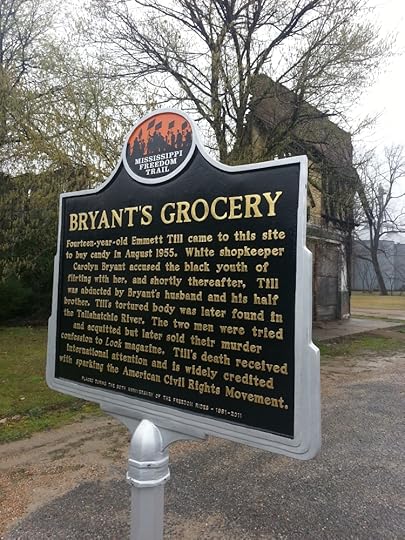

Sign outside of Bryant’s Grocery in Money, Mississippi. Richard apple, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Sign outside of Bryant’s Grocery in Money, Mississippi. Richard apple, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.It must be remembered, though, that in the immediate aftermath of her son’s death the direct visual witness Mamie Till Bradley called for was limited largely to the African American community. Emmett Till’s open-casket funeral was attended mostly by African Americans, and photos of his battered and disfigured face were rarely seen by whites, and never in the white press, during the civil rights movement. Eventually, however, the larger nation did begin to see what Mamie Till Bradley saw on that horrific day in 1955. Starting with the 1987 documentary Eyes on the Prize (whose role in shaping Emmett Till’s legacy cannot be overestimated), images of her son’s corpse started to circulate more widely, both to a new generation of African Americans and, for the first time, to whites. Since then, a steady stream of scholarly studies and documentary films, as well as works of art and websites, have enabled these images to reach a larger and more diverse audience, and this belated and repeated witnessing, coupled with the courage that Mamie Till Bradley showed in 1955, has profoundly influenced the way much of our nation responds to racial violence. Because of what we’ve seen, we cannot ignore Emmett Till. Nor should we want to.

Whether it’s Trayvon Martin or Tamir Rice, Michael Brown or Philando Castile, Eric Garner or Alton Sterling, Mamie Till Bradley’s son haunts our understanding, and he does so largely because of what his mother demanded of us more than sixty years ago: that we bear witness. In a 2016 New Yorker essay on “The Power of Looking, from Emmett Till to Philando Castile,” Allyson Hobbes makes this connection directly and forcefully, in words worth quoting in full: “Mamie Till Bradley and Diamond Reynolds both shared their sorrow with the world. They asked onlookers to view the bodies of two black men and see a son, a brother, a boyfriend, a loved one. Looking is hard. It shakes us and haunts us, and it comes with responsibilities and risks. But, by allowing us all to look, Bradley and Reynolds offered us real opportunities for empathy. Bradley’s moral courage galvanized a generation of civil-rights activists. We have yet to see how far Reynolds’s bravery will take us.”

We hope one day such bravery will be unnecessary, but as we hope we must also see, and recently in Charlottesville another mother buried a child whose life was taken by a white supremacist, with a dozen more injured and a nation shaken. Although we wish we didn’t have to, we know what we must do. We must bear witness to this wound, and the wounds still to come. And we must do so with a faith as strong as Mamie Till Bradley’s, believing that this witness is worth the risk, that in seeing we will learn to see. This is Emmett Till’s legacy, a mother’s gift to her son and, eventually, to us all.

Featured Image credit: Protest outside of Minnesota Governor’s residence in October 2016. Fibonacci Blue, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Let the world see appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers