Oxford University Press's Blog, page 321

September 24, 2017

Why we still believe in the state

How do we explain the resilience of the modern state? State power, whether expressed by politicians, parliamentarians, policemen, or judges, seems to be routinely questioned. Yet, the state as an institution remains.

The constitutional state is today the universal expression of power despite its constant questioning and its lack of ability to maintain a minimal order in large parts of the world. This two-century-old invention seems to resist despite the challenges it faces. It remains an attractive idea with a universal reach; all cultures seem to have adopted it one way or another.

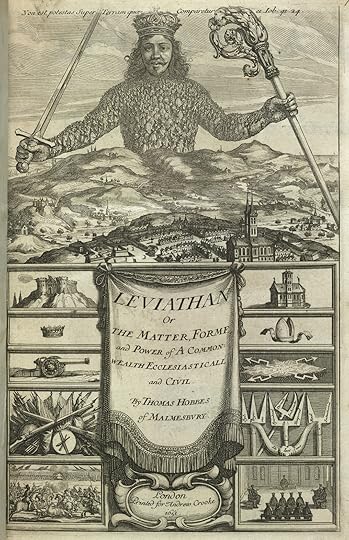

I suggest the perception of the contemporary state has much to do with the issue of legitimacy, in particular as developed by Max Weber. Weber has famously defined the state as the holder of the legitimate monopoly of violence. The monopoly of violence is often what is remembered from this sentence, whereas the most important section is in my view that concerning legitimacy. The need for the people to identify who is entitled to exert coercion in a way which is not arbitrary and responds to clear rules was best expressed by Hobbes in his Leviathan.

Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes (1651). CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes (1651). CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The issue of legitimacy takes a particular meaning in a secular context. In a context where religion is the dominant source of legitimacy, the issue is resolved by turning to the perceived self-evidence of religious power and texts. The secular state finds itself in a different situation where the justification of its legitimacy has lost the self-evidence linked to religion.

Typically the secular state has found in the idea of nation a way to sustain its legitimacy, in the form of the nation-state, and this model has proven successful and resilient despite the cultural and political challenges it has been facing. At the time of decolonization, the nation-state model has been embraced by the newly decolonized nations. Despite all the criticisms about the Western origins of the concepts of state and nation, these have taken roots in most parts of the world – not without conflicts and bloodshed (even though these did not take the dimensions of the wars in Europe, thanks in large part to the freezing effects of the cold war).

Is the model of the nation-state a transitional model or is it a model which will stay with us for the foreseeable future? For all the nice talk around the post-national and other alternative models based on civil society, we are unable to foresee a credible alternative. The nation-state is certainly bound to evolve. Its most solid dimension is based on the “legal-procedural” dimension of what I would call the “constitutional state” essentially evolved from the French/Anglo-Saxon traditions based on rule of law, human rights, and democratic rule. These are now universal standards acknowledged in most of the constitutions – the fact that they may be misapplied in practice or under threat in many countries does not change the fact that they remain valid and relevant standards.

What is more worrying for the nation-state is not so much the institution of the state but rather the idea of nation. The main issue for the state around the world is not so much its institutional basis, but rather its cultural dimension – which in turn affects its legitimacy and explains why state power is being challenged. To come back to my earlier point, the withdrawal of religion as a source of legitimacy is creating a gap that ideas such as the “nation”, the “people” can only fill partially. Terms such as “nationhood” and “sovereignty of the people” evoke a cultural and political unity that did not ever actually exist, but – assuming such unity did exist – such idea of unity does not correspond to contemporary pluralistic societies.

Church Window by Didgeman. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Church Window by Didgeman. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.The issue here is to unify the state in a plural cultural context. How can this be achieved? I would argue that a purely secularist approach, based on the Weberian “legal-rational” form of legitimacy, is not enough. The state cannot found its legitimacy if it is divested of religious or cultural references. At the same time, the issue of the cultural or religious dimension of the state is not easy to solve: in the pluralistic context of contemporary societies, strong cultural references within the state would either alienate part of the population or lead to a cultural fragmentation. The solution lies in the context of a state that should remain secular, for this is the only way one can address competing cultural and religious identities. But instead of removing culture and religion from the state, the state should directly address cultural and religious issues by ensuring that all voices can be heard as long as they are a unifying contribution within the state. Particular cultural and religious views should be welcomed as long as they are based on the “universalization” of their message and aim at reaching beyond the limits of a particular cultural or religious community.

Featured image credit: “European Parliament” by cuongdv. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Why we still believe in the state appeared first on OUPblog.

The mystery behind Frances Coke Villiers [extract]

Frances Coke Villiers was raised in a world which demanded women to be obedient, silent, and chaste. At the age of fifteen, Frances was forced to marry John Villiers, the elder brother of the Duke of Buckingham, as a means to secure her father’s political status.

Defying both social and religious convention, Frances had an affair with Sir Robert Howard, and soon became pregnant with his child. The aftermath of their affair set Frances against some of the most influential people in seventeenth century England.

Insight into Frances’ life has diminished with time, causing her become known as a mysterious and scandalous figure. In the following extract from Love, Madness, and Scandal, Johanna Luthman pieces together the historical life of Frances Coke Villiers to better understand one of history’s notable rebels.

In early June of 1645, the town of Oxford was under siege. The Parliamentarian New Model Army had arrived three weeks prior, rapidly blockading all entrances and exits and trapping the nervous inhabitants inside. Normally a center for learning, Oxford had been transformed into royal headquarters during the English Civil Wars, and King Charles’s courtiers and supporters crowded into the small town until it was bursting at the seams. Lords and ladies, used to the luxury of palaces and large staffs of servants to tend to their every need, now had to suffer meager and plain dishes in cramped quarters. The town streets soon overflowed with trash and filth.

The overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in Oxford made its population vulnerable to infectious diseases. A severe plague epidemic had ravaged the town the previous summer. Outbreaks of smallpox, typhus, and other diseases also kept the gravediggers busy. Before the siege, the sick had sometimes been forced into quarantine in the outskirts of the city, but with an enemy army guarding the gates, that method was not available. One of the many who fell ill during this siege was a noblewoman who had arrived in the city a few months earlier. Her name was Frances Coke Villiers, the Viscountess Purbeck. On 4 June, just one day before General Thomas Fairfax received orders to lift the siege of Oxford and join other Parliamentarian troops poised to engage the king’s forces to the north, Frances died.

Portrait of Frances Coke, Viscountess Purbeck by Michiel Janszoon Miereveldt. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Frances Coke, Viscountess Purbeck by Michiel Janszoon Miereveldt. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.If Frances had the mental energy for contemplation as she lay shivering and sweating during her final disease, she might have looked back on a life filled with countless struggles. As an adolescent and young woman, she had been forced to bow to the authority of her parents, in-laws, and sovereign. She grew into a very strong-willed person, increasingly insistent on being treated according to her noble status. As an adult, her head would tilt for no person, but her own choices also created increasingly difficult challenges. Those who loved and admired her believed she was a beautiful, brave, witty, and romantic, albeit tragic, heroine. Those who disliked her thought she was an annoyingly stubborn, haughty, greedy, and scandalous woman. Either way, most people found her very difficult to ignore.

Young Frances’s marriage to Sir John Villiers in 1617 significantly changed the trajectory of her life. Frances’s parents, Sir Edward Coke and Elizabeth Cecil (known as Lady Hatton) clashed over the issue of her marriage, sending huge waves and ripples through the courtly society of King James I. Frances, like so many other daughters of the seventeenth-century elite, did not choose her own husband, but conceded that her parents would bestow her in marriage. Her marriage to John Villiers, her father’s candidate, initially afforded her many privileges, including membership in the highly favored and influential Villiers family with even closer connections with the royal court.

Frances’s in-laws, the Villiers family, owed their power to the fact that John’s younger brother, George Villiers, was King James’s beloved, the last and greatest of his royal favorites. Like his predecessor Queen Elizabeth, King James I (ruled 1603–25) enjoyed having handsome, flattering men close at hand, who could provide company, adoration, and entertainment. While Elizabeth had been sparing in gifts, wealth, and positions to her favorites, James seemingly could not lavish enough rewards on those he loved. They rose to great positions of political power, collected a variety of influential offices, became enormously wealthy, and also made influential and rich marriages. This was true of George Villiers, who eventually became Duke of Buckingham, arguably the most powerful man in England next to the king. When Frances came of age, Buckingham reigned supreme in the heart of the king, and all attempts to lessen James’s attachment to him had failed.

Despite its apparent benefits, Frances’s marriage turned out to be a disaster. Frances’s own responses to her marital difficulties in turn created endless problems in her life. First, her husband succumbed to an intermittent and debilitating mental illness. Separated from him, Frances then struggled with her resistant in-laws to receive financial support. At this juncture, she took a lover, became pregnant, and gave birth to an illegitimate son. Her actions turned her in-laws even more firmly against her, and their great powers now became a burden instead of a boon, as they had both the political and economic capital to pursue her relentlessly. Frances had to fight the consequences of her illicit love for the rest of her life. As the years passed, she became even more tenacious than her pursuers, and no matter how much they fought her, she never gave up.

The historical Frances has remained rather elusive. She was neither a political person, nor a literary one, and thus no one thought it important to preserve most of the papers an upper-class life necessarily produced. Only a precious few of her letters and petitions have survived, giving us a glimpse of Frances’s own interpretations of her life and actions. Instead, we learn about her mostly because of others’ reactions to her deeds, movements, and decisions. Because her parents, husband, and in-laws were influential people at court, people who cared about court politics and wanted to keep abreast of the news often wrote about Frances’s contentious marriage and the scandals that followed when she had an affair. Other sources include administrative and legal records, like those of the High Commission court, both houses of Parliament, Acts of the Privy Council, and the extensive State Papers, a rich collection of letters, petitions, royal orders, warrants, and investigations. Frances’s life is like a puzzle, where many pieces unfortunately are irretrievably lost. Nevertheless, the picture that emerges of this seventeenth-century woman from the pieces that we do have is both intriguing and compelling, and more than worth the telling.

Featured image credit: “Oxford. State 1.” by Wenceslaus Hollar. Provided by University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The mystery behind Frances Coke Villiers [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Mary Wollstonecraft [quiz]

This September, the OUP Philosophy team honors Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) as their Philosopher of the Month. Wollstonecraft was a novelist, a moral and political philosopher, an Enlightenment thinker and a key figure in the British republican milieu. She is often considered the foremother of western feminism, best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), which was written during the period of great social and political upheavals towards the end of the eighteenth century.

How well do you know Mary Wollstonecraft’s life and work? Test your knowledge with our quiz below.

Quiz image: Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Green Tree on Grass Field. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Philosopher of the month: Mary Wollstonecraft [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

September 23, 2017

A conversation with ALSCW President Ernest Suarez- part 1

We seldom have opportunity to get the inside-scoop on a journal from those who work so hard to make it possible. We caught up with Ernest Suarez, president of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers (ALSCW), the society who publishes Literary Imagination. Find out more about the background and scope of the journal, as well as how Ernest views the past, present, and future of the fields of literature and creative writing.

1. Can you tell us a little bit about the history of the ALSCW and Literary Imagination?

The Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers was founded in 1994 by what an article in the New York Times called a “Who’s Who of literary critics.” We still have a very rich membership, one that consists of critics, poets, playwrights, novelists, translators, musicians, secondary school teachers, literary agents, and even a few scientists—including two NASA astronauts. Our members have received MacArthur Fellowships, Grammy Awards, Carnegie Fellowships, and more. We’re all about literature and the arts–and about providing opportunities for people from many backgrounds to interact. Mentorship is a strong part of our ethos. The ALSCW grew out of the conviction that literary study had become so overly politicized that people were losing sight of why literature, literary study, the arts, and humanities are valuable. Literature and the arts often contain a political dimension, of course, and that’s an important part of the picture, but it’s not the entire picture. We read writers from Homer to Shakespeare to Emily Dickinson to Derek Walcott to Toni Morrison to Philip Levine because their work helps us think about what it means to be human. That’s a large and complex matter. Great literature has been written by people from diverse backgrounds who approach what it means to be human in a variety of ways. That dynamic is what makes literary study rich and textured.

Literary Imagination started in 1999 as a journal that reflects the ALSCW’s values. The journal stresses the synergy between literary history and aesthetics, and focuses on literature from different periods and in different languages. Artists seldom experiment with aesthetic forms just for the sake of it. As perceptions of the world change, greats artist create new techniques in order to engage new ways of conceiving reality. As time progresses and new works of art are created, the significance of previous works shift. For instance, if it were not for Morrison, Charles Johnson, and other writers’ use of slave narratives in their fiction, slave narratives would be considered important historical documents but they wouldn’t have the same literary resonance. If Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman would not have had a wide influence on subsequent writers, they would be viewed as talented anomalies rather than as influential innovators.

LI publishes essays that explore the significance of literary works throughout the ages, as well as original poetry and fiction by writers ranging from Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winners to folks whose careers are just getting underway. The journal’s editor—Archie Burnett—is a world renowned scholar who has edited the verse of Milton, Housman, Larkin, and others. Rosanna Warren and I recently became associate editors. Rosanna is one of our finest living poets and a wonderful scholar.

2. How has the field changed since the founding of the journal in 1999?

I think there’s been a slow and steady shift, especially among younger scholars, back towards studying literature-as-literature and towards an emphasis on the relationship between literature and the other arts, and away from seeing literature primarily as a sociological phenomenon. The ALSCW and Literary Imagination have played a powerful role in this transformation. This doesn’t mean ignoring literature’s political and cultural dimensions. It means engaging those things more fully and accurately. One of our members, Robert Levine, who teaches at the University of Maryland and is the General Editor of the Norton Anthology of American Literature, recently wrote a superb book on Fredrick Douglass. In it he strives to examine Douglass’s autobiographies “as Douglass regarded them,” and stresses that “recovering Douglass as best we can in his own time helps us construct a more vital Douglass for our own—a figure, in other words, that is more than simply a figment of our collective cultural imaginations.” Marjorie Perloff, a former Vice President of the ALSCW, has a marvelous new book, The Edge of Irony, on modernist novelists, poets, and playwrights from Austria. She uses biography and cultural history to situate the artists during a volatile time, and provides nuanced close readings of works that center on their artistic merit and cultural resonance. Marjorie also has a terrific article on T.S. Eliot in the new issue of Literary Imagination. This type of scholarship advances our understanding of literature, literary history, culture, and most importantly, what it means to be human and live in the world. It’s the kind of writing that’s published in Literary Imagination.

3. What do you hope to see in the coming years from both the field and the journal?

The type of writing I described in answering the question above, as well as fine poetry, fiction, and other forms of literature. Personally, I like criticism with a narrative emphasis, scholarship that carefully situates writers and works within their historical moment and that offers close readings of works within those contexts—and I appreciate criticism that goes on to explicitly and implicitly assess how particular writers have impacted subsequent writers and the implications for our thinking today. I would like to see more criticism by practicing artists; it tends to help remind us that literature and art are created by human beings, and contain all the ironies and paradoxes associated with diverse people at different times and in different places. I think there’s excellent work being done by narrative theorists who understand the nuances of literary form and its relationship to human expression. I also think there’s terrific work to be done on “poetic song verse,” forms of song that use voice, instrumentation, and arrangement to foreground richly texture lyrics. We see it as a subgenre of song that’s also a form of literature.

4. Tell us about your work as the President of the ALSCW.

It’s an honor and a pleasure to be involved with the ALSCW. I chaired an English department for seventeen years, and along with my colleagues, put together a program that stressed literary history and aesthetics. The ALSCW has a similar emphasis, but on a much larger scale. I’m most passionate about literature and teaching literature. Two years ago our national headquarters moved from Boston University to Catholic University, where I teach. The University has been very supportive. My current Dean, Aaron Dominguez, is a world class physicist who memorizes Derek Walcott’s verse. Our DC location is a big asset because it helps put us into direct contact with decision makers. There’s also a concentration of colleges and universities in the area. One of the ALSCW’s priorities is to enhance the ways literature is taught on the high school, undergraduate, and graduate levels. Our headquarters also helps with fundraising, and helps organize the annual national conference and local conferences. I think our troubled nation and world are in desperate need of what literature and the humanities offer. My work with the ALSCW involves making sure that literature and literary study enriches the lives of as many people as possible. We give out the Meringoff prizes in poetry, fiction, and the essay, and a high school prize for literary criticism. We give out an annual fellowship to a poet or translator through the Vermont Studio Center and another annual fellowship to a person writing his or her dissertation. The opportunity to help with Literary Imagination is something I relish.

Featured image credit: Books by StockSnap, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A conversation with ALSCW President Ernest Suarez- part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

From lawyer to librarian: one woman’s journey

Many paths can lead to the same destination. Though it might seem like a cliché, this statement proves to be true for Isabel Hermida Cornelio, a lawyer-turned-librarian from the Dominican Republic. In the post below, she shares the story of her career journey from the court houses to the circulation desk.

In our household, reading came as easily as breathing. It was a part of our identity, ingrained and passed down through generations of scholars, writers, and thinkers in our family tree. It was a joy and it felt necessary to life. Bedtime stories, visits to the bookstore, talks about books, and buying books on trips abroad with our parents were second nature to my sister and me. What was noticeably absent from this literary childhood were trips to a community library.

In the Dominican Republic of the 1990s, community libraries did not abound. Suffice it to say, my knowledge and awareness of libraries were given to me by my school libraries as I studied throughout the years, in some of the best private schools my country had to offer. Thus, my knowledge of librarians was also quite limited–except for Rose, the librarian of my childhood school, who would always point out good books to read to my sister (and later to me as I moved into the elementary grades). She always knew which books to recommend next. It never occurred to me that I could become a librarian; so, with a deep love for books, I thought I would become a writer.

As the years went by and my love for literature and reading grew, so too did my desire to study something related. Although we had excellent universities in the Dominican Republic, they mainly offered traditional career paths and so, having chosen to study in the DR, studying Creative Writing or Literature was not really an option for me. The adults in my life, and my vocational exam results, suggested Law. I had good writing and oral skills; I loved reading; I could make a good living out of being a lawyer; and, I could always read and write on the side, if I so chose. So I did. I went to college and became a lawyer, and worked for almost two years as an assistant at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of my country–an incredibly rewarding growth experience, but one that did not offer the vocational fulfillment I expected and desired from my work life.

“It never occurred to me that I could become a librarian.”

My mother was an educator, and had watched me over the years work in summer camps and afternoon tutoring programs, but had wisely allowed me to make my own choices. It finally dawned on me how much I loved working with children and young people while teaching Sunday school at my church. I asked for advice from my parents, and from my former high school principal, then promptly accepted a job working as a substitute teacher at my old school. I loved every minute of it. I loved teaching because it combined the intellectual and creative aspects of my personality, and it spoke to me in a way law never could. I probably would have become a classroom teacher had I not met and spoken with the librarian of the school at that time. She was the one who first explained to me the science and art of being a librarian, of being an information maverick and a literature savant. She left halfway through the school year; and, as a substitute, I had the privilege of stepping into her shoes multiple times for the rest of the semester.

I was hooked. I bided my time, completed a postgraduate program in education so that I could teach, and I waited until the position of librarian opened up at our school–and when it did, I jumped on it! I completed the credits necessary in school librarianship through an online program and I submerged myself into this magical and little known world that is librarianship. I read everything I could–books, magazines, and blogs. I watched webinars. I scoured the Internet for ideas and information.

What I discovered, once I dove into this profession, was how different it was from anything I had ever sought for myself. I never thought I could become a librarian. At most, when I was younger, I thought I could be a like Meg Ryan in You’ve Got Mail and become a bookstore owner. I loved how I could bring to the table the critical thinking and information skills I had acquired while studying law. Furthermore, I had first-hand knowledge of copyright, plagiarism, and ethics in the use of information, which I could impart to my students with the authority that I was, in fact, a lawyer, and the weight of the law was backing me up as I instructed them on how to become ethical information users.

“What I discovered, once I dove into this profession, was how different it was from anything I had ever sought for myself.”

I never realized this enriching career path could be available to me. Others didn’t either. It was an interesting conversation, having to explain to my father that after becoming a lawyer, then a teacher, that I now wanted to be a librarian. He thought I would be stamping books in a forgotten damp room somewhere. I had to explain that in the 21st century librarians are so much more than that – that we teach children how to access information in a way that is reliable, safe, and ethical; that we cultivate in our students a love for reading throughout their years at our school, celebrating activities and programs that allow them access to realities both foreign and familiar in an effort to give them a peek into the world through reading; that we train students, teachers, and staff members in good information practices and other literacies needed to be successful in their careers and in life; and, that we teach empathy and friendship through the stories we share and the communities that we build in our libraries.

Furthermore, our libraries are so much more than book depositories; they are alive as places to feel safe and make friends, to collaborate with others, to read, to work, to study, and to create. The best part, on this my 5th year in this job, is listening to my father explain to others in our community what it is that I do, and having him and my mother support this incredible career path that I have chosen to take.

Libraries are changing, and my country is as well. There is a beautiful public library for children and young adults that is working to give them access to not only books and information, but to a world so much larger than our beautiful island. Much work is being done in the public sector as it is in private schools like mine, where libraries and media centers are taking center stage and being given the opportunity and resources to flourish into the 21st century. Now, my greatest desire is to open windows for my students so that they can really explore all the different career and life paths that can be available to them, and – who knows! – maybe, one of them will come back and become the next librarian at our school!

Featured Image Credit: “roads-320371_640” by artvertau, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post From lawyer to librarian: one woman’s journey appeared first on OUPblog.

The switch to electric cars

Much has been written about autonomous, driverless vehicles. Though they will undoubtedly have a huge impact as artificial intelligence (AI) develops, the shift to electric cars is equally important, and will have all sorts of consequences for the United Kingdom. The carbon dioxide emissions from petrol and diesel cars account for about 10% of the global energy-related CO2 emissions, and the UK government has recently announced that all new cars sold in the UK after 2040 should be electric.

Contrary to some misconceptions, electric cars are effective in lowering emissions, as long as the electricity used to charge them is clean enough. While the carbon intensity (gCO2 emitted per kWh generated) of Britain’s electricity averaged 740 g/kWh in the 1980s and 500 g/kWh in the 2000s, it was just below 200 g/kWh during the period April-June 2017. This reduction has come from the switch from coal to gas and biomass fired power stations, and the significant increase in generation from wind and solar. The carbon intensity is now often below 100 g/kWh for short periods. The result is that, assuming electric cars are charged throughout the day with the current mix of generators, their CO2 emissions per mile are now less than half that of the best petrol or diesel cars. And this will get better as more renewable generation comes online.

Besides helping to reach the UK targets for reducing climate change, switching to electric cars cuts out the harmful particulates and nitrous oxides, emitted in particular by diesel engines. Since electric cars brake mainly by using their motors as generators, there are few particulates emitted from braking. However, the amount from tyre wear is similar to that from petrol or diesel cars, but this can be improved by reducing acceleration, deceleration, and weight. Autonomous driving, which is being promoted by electric cars, will help.

2011 Nissan Leaf photographed in Waldorf, Maryland, USA by IFCAR. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

2011 Nissan Leaf photographed in Waldorf, Maryland, USA by IFCAR. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.To provide the electricity for recharging the batteries of electric cars, the National Grid in their Future Energy Scenarios estimate that their generating capacity will need to increase significantly. In their lowest CO2 emission scenario, called ‘Two-Degrees’, an additional six gigawatts would be needed by 2050, when effectively all cars in the United Kingdom will be electric. The United Kingdom is fortunate in having very good wind resources, and electricity from on-shore wind farms is now as cheap as that from fossil fuel plants; within a few years it will be just as economic from off-shore wind farms, where space and visual impact are not such a concern. Together with solar and biomass, wind power can give the extra generating capacity the United Kingdom will need, but handling the variability in supply will require investment in energy storage, smart grids, and interconnectors.

There are several other factors that must be improved to speed up the switch to electric cars. Their performance is very good; but at present, they are too expensive, have too short a range, and recharge too slowly. Moreover, there are far too few charging points available. The UK government has started to address the lack of number of charging points, and some new electric cars are now equipped with batteries that give 300 miles range, which is similar to that of many present cars. These improvements should remove the ‘range anxiety’ that currently makes electric cars unattractive to some customers.

The time it takes to top up a lithium-ion battery also needs to be improved. Typically, it takes around 20-30 minutes. Faster charging batteries, one, for example, with the potential to charge in five minutes, are under development. To cope with many cars recharging at once, ‘filling’ stations with banks of batteries will be needed to smooth out the load. Also smart chargers in each electric car would enable the demand to be spread out over time, and help in deciding where to recharge.

The main hurdle to switching to electric cars is the cost. Electric cars have many fewer components than petrol and diesel cars, mainly because of the simplicity of electric motors, but their high price is primarily due to the cost of the battery. Research and development are driving down battery costs, and as global production increases, prices are falling; this is particularly true for lithium-ion batteries. There is a well-established link between production and cost called the ‘experience’ or ‘learning curve’: there is an approximately constant percentage fall in cost for each doubling in global production. This percentage is called the ‘learning rate’ and is typically around 20% for developing technologies.

For lithium-ion battery packs the learning rate was 19% during 2010-2016, and in 2016 their average cost was $273/kWh when the cumulative global production was ~40 GWh. Assuming the same learning rate, then by 2026 production is estimated to be ~1 TWh and the cost ~$100/kWh, and by 2031 ~3 TWh and ~$70/kWh. This would mean that by the end of the 2020s electric vehicles will be economically competitive with internal combustion engine cars.

So the performance and cost of car batteries look likely to be attractive enough for there to be a significant switch to electric cars over the next decade. Hybrid and plug-in hybrid cars will have a share of the market initially, but their complexity makes them expensive, and pure electric cars—such as the Nissan Leaf currently produced in Sunderland—will quickly dominate as battery prices fall. Many of these will be autonomous and shared, improving safety, and lowering the cost of travel, and will herald a new age of car transport.

Featured image credit: Charging Station by Mark Turnauckas. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The switch to electric cars appeared first on OUPblog.

Trump, trans, and threat

On 26 July, 2017, President Trump tweeted his plan to ban transgender individuals from serving in the military. Besides the “tremendous medical costs” that he cited (which is actually less than a thousandth of 1% of the Defense Department’s annual budget), Trump referenced the idea of “disruption.”

When I read the tweet, a thought crossed my mind: What exactly is being disrupted?

In short, the “natural” sex-gender order —where “what you have” is “what you are.” This is a conflation of “sex” and “gender.” Sex is considered “what you have”— genetic makeup, hormones, reproductive sex organs, membership in one of two biological categories. Gender, however, is socially constructed, certain characteristics perceived as associated with biological categories of male and female. These are known as masculinity and femininity, and often referred to as traditional gender roles. In other words, a binary biology determines your personality, your ability to excel in certain careers, even your salary. It determines who you will fall in love with: traditional gender roles predetermine a sexual default—heterosexuality. The privileging of this sexuality and its acceptance as given is called heteronormativity.

The sex/gender order is the foundation of what is known as the “patriarchy,” or patriarchal society. This societal system produces Insiders and Outsiders based on their conformity to this order; anyone who does not conform is considered weird, deviant, even dangerous. Examples include people who are trans or gender fluid (not identifying as male or female), or even “cis-gender” people (who identify with the sex they were born with) not acting “appropriately” feminine or masculine, like men who cry openly, or assertive women who are derided as “bitchy” or “bossy.” Race and class also play a role in determining Insiders and Outsiders. Any Outsider is perceived as a threat to society. Trump’s tweet is a response to this perceived threat, his action an example of the defense of the sex-gender order.

To minimize perceived “disruption,” public spaces are policed as non-trans zones (see trans “bathroom laws”). A 2015 National Center for Transgender Equality study in the US found that 46% of the 27,715 respondents were verbally harassed in the last year. As of 2015, trans people in 34 European countries could not change their name or registered gender without compulsory genital reassignment surgery, divorce, or until very recently, sterilization. The requirements are telling. Compulsory genital reassignment surgery removes any sense of grey zone between the binary—you are either male or female, and the parts must match the gender. Divorce and sterilization keep trans people from having families and children, maintaining its heteronormative and cis-gendered form.

By Jamie Bruesehoff/@hippypastorwife. Used with permission.

By Jamie Bruesehoff/@hippypastorwife. Used with permission.The sex-gender order is considered natural, but, as these examples and the infamous tweet show, is in fact an elaborate social construction that requires constant surveillance to maintain it. Individuals who fall outside this order are shunned and disciplined—by state control, by biopolitical regulation of trans bodies and minds, and by rejection from public spaces and state institutions. These mechanisms of repression are incredibly dangerous because they all build to warrant the final stage of threat removal—fatal violence.

The concept of trans-as-threat has been used as a legal defense of violent crime—even murder of trans individuals. The basis of the legal argument is that murder was justifiable (even provoked) because of the victim’s lack of normative gender-genital agreement. This is called the “trans panic” defense, and follows closely a long history of the “gay panic” defense, first utilized in 1965. A “trans panic” defense was used in 2004-5 in California by three defendants who had murdered trans woman Gwen Araujo. The lawyer for one of the defendants argued that they were “only” guilty of manslaughter on the basis of this “trans panic,” that the “discovery of [the victim’s] ‘true sex’ had provoked the violent response to what was represented as a sexual violation ‘so deep it’s almost primal’” (Bettcher 2007:44). This defense attempts to naturalize violence against threat, to propose that it came from a “biological,” “primal,” “normal” response to what is considered deviancy. And the jury was persuaded: three defendants were found guilty of lesser charges, and the murder was not deemed a hate crime.

Race also plays an important role in how threat is perceived. Trans people of color are especially targeted as racism, misogyny, and transphobia all intersect. In 2016, 27 trans people were murdered, one of the deadliest years on record, and most of them were women of color. The long history of institutionalized prejudice against people of color (including formal and informal segregation within the US military), with its innumerable injustices and violence, persists because the Western patriarchal order equates the “Insider” with “White.” People of color in America, along with people who live outside of the confines of the sex-gender order, are considered Outsiders. This Inside/Outside divide perpetuates and reinforces the idea of threat.

And as we have seen, this idea plays politically. Recent findings have shown that Trump’s base is motivated by perceived threat: racial resentment and fear of a “status shift” of their ethno-national majority. Trump’s racist, xenophobic, and now anti-trans language reinforces the Inside/Outside, the “Us” and “Them,” and the base responds positively to it. The trans ban is just another brick for his wall, a way to bolster the racial and gendered hierarchical order. Clearly, it is part of the 2018 midterm election strategy, as a Trump administration official stated.

Ultimately, policies like this resonate because of the ways our patriarchal culture privileges traditional gender roles and heterosexuality, because of the ways that threat is constructed and “resolved.” What is important to realize is the big picture: these policies and the attitudes they reflect will continue to persist, beyond this presidency, unless we move past these norms.

Featured image credit: Protest Trans Military Ban, White House, Washington, DC USA by Ted Eytan. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Trump, trans, and threat appeared first on OUPblog.

Smile like you mean it

“With a camera you can go into the stomach of a kangaroo,” mused Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. “But to look at the human face, I think, is the most fascinating.” It is hard to contest Bergman’s claim that “the great gift of cinematography is the human face” – or at least that it is one such gift. The face has long been an important subject in painterly and photographic portraiture, and it surely plays an important role in many forms of theater. Through its capacity to capture movement, to frame the face with unprecedented intimacy, and to render drama through facial expression, however, the art of film subsumes and intensifies the ancient artistic preoccupation with the face.

Denis Lavant in Rabbit in Your Headlights (Jonathan Glazer, 1998).

Denis Lavant in Rabbit in Your Headlights (Jonathan Glazer, 1998).It is not all about expression though. Often enough, the sheer look of a face is enough to capture our attention, from the varieties of beauty the world of filmmaking constantly parades before us, to the equally compelling focus on the memorably idiosyncratic faces that also grace our screens (consider the magnificently weird visage of Rossy de Palma – flanked here by María Barranco and Antonio Banderas – for example, or the rough-hewn landscape that is the face of Denis Lavant). The great Hungarian scenarist and film theorist, Béla Balázs, was the first to explore this feature of the new art of film in depth, extolling its capacity to illuminate the “microphysiognomy” of the face.

Rossy de Palma, María Barranco and Antonio Banderas in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Pedro Almodóvar, 1988).

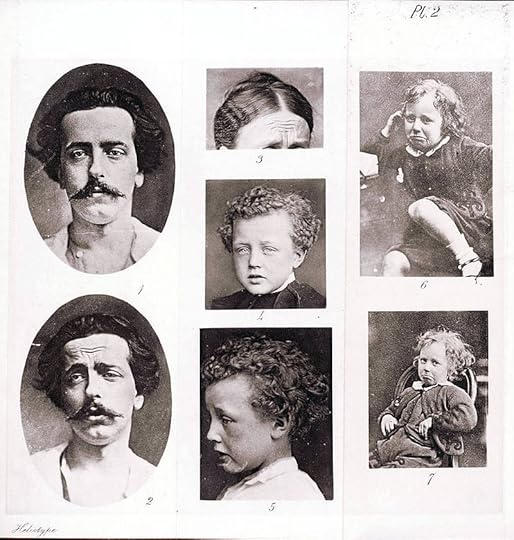

Rossy de Palma, María Barranco and Antonio Banderas in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Pedro Almodóvar, 1988).Cinema is a product of the late nineteenth century, and the facial close-up emerged as a central filmmaking device soon afterwards. The same period saw the formation of psychology as a scientific domain, and the impact of Darwinian ideas on both science and culture in general. Darwin’s third book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), forms a fascinating link between the apparently separate worlds of art and science. For in this classic work, Darwin not only made extensive use of cinema’s sister art, photography, to support and illustrate his investigation into the forms, functions, and evolutionary origins of emotional expression he also laid the foundation for a theory of emotion which greatly illuminates our understanding of facial expression in the arts. This, at least, is one of the hypotheses of my Film, Art, and the Third Culture, in which I seek to synergize the creativity of filmmakers working with the face and the dramatic expression of emotion, the insights of scientific psychologists unearthing the laws of emotion, and the interpretive skills of the critic – along with the theoretical acumen of the philosopher in showing how these superficially disparate elements, in the words of Wilfrid Sellars, do in fact “hang together.”

Darwin; The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Darwin; The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Consider the smile. On Darwin’s view, a smile is a way one individual conveys to another their positive state of mind to one or more other individuals. It is, precisely, an expressive behavior – revealing in behavior an individual’s current emotional state. So far, so familiar: like other expressions, a smile points inwards and outwards, conveying the happy state of mind of the smiling individual to the world outside. In this way, emotional expressions perform the critical function of socially co-ordinating individuals. But as Paul Ekman – perhaps the most eminent neo-Darwinian psychologist of the past fifty years – argues, smiles come in various shapes and sizes. Alongside uncomplicated smiles of joy, there are smiles of relief, pained smiles, rueful smiles, embarrassed smiles, and sadistic smiles to name but a few variations. Though arguably all of these variations depend on the felt, happy smile as a basic template, we cannot rest with the adage: a smile is a smile is a smile.

Billy Bob Thornton as Lorne Malvo in Fargo (Noah Hawley, 2014).

Billy Bob Thornton as Lorne Malvo in Fargo (Noah Hawley, 2014).Arguably the major distinction to mark among smiles – in Dacher Keltner’s words, “the first big distinction in a taxonomy of different smiles” – is that between the smile of happiness and the social smile. Among specialists, the former is known as the “Duchenne smile,” after the nineteenth-century French physiologist Duchenne de Boulogne who discovered the distinction (and upon whose photographs Darwin drew for his Expression of the Emotions). In a Duchenne smile, the muscles around the eyes are active along with the those that pull the sides of the mouth into the familiar upwards curve (the crow’s feet wrinkle and the eyes narrow); a social smile is, roughly speaking, only half a smile, the orbicularis oculi around the eyes remaining unresponsive.

Clarissa (Salome Kammer) gives a reassuring “social smile” to her mother in Heimat 3 (Edgar Reitz, 2004).

Clarissa (Salome Kammer) gives a reassuring “social smile” to her mother in Heimat 3 (Edgar Reitz, 2004).The social smile is as important as the felt smile, in life and in film, and insofar as we cannot take a social smile at face value, it opens up a world of complexity. In this scene from The Affair, Alison briefly adopts the smile we see here.

Alison (Ruth Wilson) in The Affair (Sarah Treem and Hagai Levi, 2014).

Alison (Ruth Wilson) in The Affair (Sarah Treem and Hagai Levi, 2014).Isolated from the unfolding action and abstracted from the moving image, it is difficult to identify this as a social smile, but in context it is clear enough to any attentive viewer. In the midst of sexual foreplay, Noah notices some marks on the inside of Alison’s thighs. Alison’s mood abruptly changes (“Hand me my fucking dress!”), and we understand that what Noah has discovered are the scars of self-harm we have witnessed Alison inflicting upon herself in flashbacks. Then the smile: a smile meant to reassure Noah even as she withdraws from sexual activity with him. Ekman suggests that an adopted expression like this will often be compromised by the “leakage” of felt emotions onto the face, and will lack “smoothness in the way that it flows on and off the face.” Alison’s smile is certainly only fleetingly adopted.

Alison (Ruth Wilson) in The Affair (Sarah Treem and Hagai Levi, 2014).

Alison (Ruth Wilson) in The Affair (Sarah Treem and Hagai Levi, 2014).As social creatures, we are highly sensitive to the subtle variations in emotional expression exemplified by the smile. Filmmakers use their craft to streamline and sculpt the expressive repertoire of the human face in different ways for different aesthetic ends. And so the play of emotions on the human face becomes part of the fabric of film.

Featured image credit: group photo by Creative Vix. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Smile like you mean it appeared first on OUPblog.

September 22, 2017

Love and hate politics

‘Love versus hate’ has become a standard frame for describing today’s primary political divide. In the face of the world-wide rise of right-wing movements and governments, and especially since the demonstration of fascist and white supremacist groups in Charlottesville, it is generally taken for granted that hatred is the prime motivation for the most horrible and destructive political forces.

This depiction of the political landscape, however, obscures the real nature and motivations of contemporary right-wing movements and, moreover, prevents us from recognizing what would be necessary for love to play a progressive and even revolutionary role.

The conception of a love versus hate political divide should be troubled, first of all, by the fact that those political forces charged with hate generally understand themselves in terms of love. Marine Le Pen, for instance, whose anti-migrant rhetoric echoes that of numerous other right-wing political forces, including Donald Trump and the Brexit campaign, insists that her real message is love. When accused of drawing on the anger of white voters and fomenting hatred against migrants during her 2017 presidential bid, she countered that “The banner I fly is love. Love that the French have for their country, their culture, their identity, their landscape, their history.”

On another occasion, Le Pen castigated the mainstream press for using the word ‘xenophobic’ to describe her supporters’ common chant “on est chez nous” – which could be translated as “we are at home” or, more aggressively, “this is our house.” “But no, gentlemen and ladies,” she asserted, “it is not a cry of xenophobia, it is a cry of love for what belongs to us, our country. Yes, you are at home!” The mistake of critics, according to Le Pen, is to interpret her followers as being motivated in relation to those outside, whereas their prime motivation is inward looking – a love of one’s own.

Germany’s Identitarian Movement (Identitäre Bewegung), an anti-migrant and anti-Islam movement that bears strong resemblances to segments of the alt-right in the United States, celebrates “homeland love” (heimatliebe) with a similarly inward orientation. “The love of one’s own and the consciousness of our ethno-cultural identity,” the group affirms on its website, “are a matter of course, for which we should not be ashamed.” This love is the basis for conducting projects such as a sea campaign to prevent rescue vessels from saving migrants in the Mediterranean.

People protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline stand in the street with signs and banners by Pax Ahimsa Gethen. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

People protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline stand in the street with signs and banners by Pax Ahimsa Gethen. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Even white supremacists insist they are guided by love. Sara Ahmed analyzed, for instance, how white supremacist “hate groups” conceive of themselves as “love groups,” driven by a deep pride in the “white racial family.” Acting out of love in such political movements does not mean, of course, that hate is not part of the mix. The point is that they love their own kind first and foremost; hatred of others is secondary, a consequence of love of the same. What appears as hate from the outside, then, is understood and experienced from the inside as love.

It may be tempting, when such violent and reactionary political movements claim they are motivated by love, to respond that, no, despite what they say and even what they feel, that is not really love. Seeking to disqualify claims of political love in this way, however, is not only condescending but also counterproductive because it prevents us from understanding the powers of attraction of these movements and grasping the experience and consciousness of participants. To admit that they act out of love does not justify or condone their actions but instead constitutes a first step toward understanding their worldview. (This was Wilhelm Reich’s point many years ago in studying the mass psychology of fascism and it is the basis for recent studies of Trump voters, like that of Arlie Hoschschild.) And recognizing this should focus critical attention on the mode of love that drives them – a vile, identitarian love.

So should we seek to ban love from politics entirely? Hannah Arendt came to that conclusion, and she warned against political invocations of love equally on the right and the left. In response to James Baldwin’s appeals to love, for example, Arendt declared that with regard to politics “hatred and love belong together, and they are both destructive.” Trying to ban love from politics, however, is probably a futile endeavor and, perhaps more importantly, it risks depriving politics of one of its most powerful and transformational forces.

All modes of political love are not equal. Reactionary movements deploy a love based on sameness: loving those who are like you, reinforcing an identity that is imagined to be pure, such as the white racial family or Christian Europe. Therefore if, as Che Guevara says, a true revolutionary is guided by strong feelings of love, then revolutionaries must first invent a new mode of love, which is open outward to engage with differences, which constructs strong social bonds based on multiplicity, and which uses its power to set in motion a process of social liberation.

Building blocks for such a notion of love can be found in many contemporary liberation movements. Lasting bonds based on multiplicity (even though not expressed in terms of political love) were developed, for example, at the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock. The protests brought together an historic gathering of North American tribes, as well as various environmental movements, other allies, and even military veterans. But the “water protectors” insisted that we need to learn to live in relation not only to each other but also to other species and to the earth itself, extending the need to form bonds to another level of multiplicity, well beyond the human. Naomi Klein reports that Brave Bull Allard, the official historian of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, conceives the aim of the protests as not only to protect the earth and the water but also “to help humanity answer its most pressing question: how do we live with the earth again, not against it?” This project can be conceived in terms of political love because, well beyond any rational calculus, it creates deep and lasting affective bonds that require those involved to undergo a radical subjective transformation. In other words, the point of such a political love, to extend Marx’s famous thesis, is both to change the world and to change ourselves.

The specific elements of the political love one might discern at Standing Rock are not as important to me as the logic of multiplicity on which the bonds are based. That logic can at least serve as one building block for a mode of love that might deserve to be called revolutionary.

Featured image credit: Meeting 1er mai 2012 Front National by Blandine Le Cain. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Love and hate politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Erich von Stroheim, the child of his own loins

Even though Erich von Stroheim passed away 60 years ago, it is clear that his persona is still very much alive. His silhouette and his name are enough to evoke an emblematic figure that is at once Teutonic, aristocratic and military. No one has forgotten his timeless characters—among others, Max von Mayerling in Sunset Boulevard, a talented film director who has become the devoted servant of the almost-forgotten silent film star whose movies he used to make, or von Rauffenstein, the prisoner of war camp commandant of La Grande Illusion with his neck stiff in a brace, perfectly symbolizing at once a world that is gradually passing away and a world that is being born. In the eyes of audiences, “the man you loved to hate”, as he was known, has lost none of his appeal.

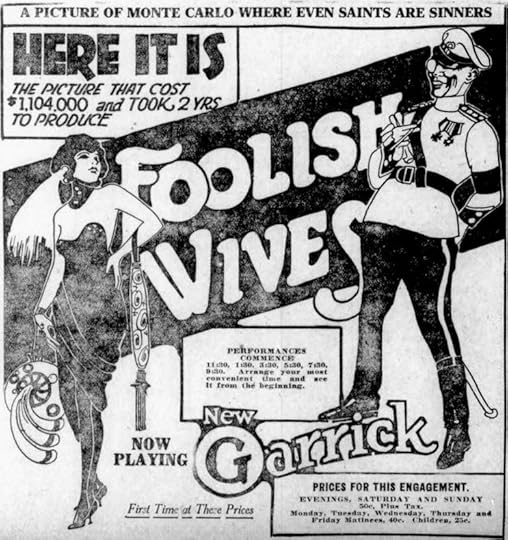

Alongside Griffith and Chaplin, Stroheim was also one of the most famous American silent film directors, who made such films as Blind Husbands, The Devil’s Pass Key, Foolish Wives, Merry-go-Round, Greed, The Merry Widow, The Wedding March, Queen Kelly and Walking Down Broadway. He was a filmmaker who was profoundly attached to realism, voicing his hope that cinema may grow into a more mature art form; a filmmaker who was an artist of excess, who was extravagant and flamboyant and whose nine films changed cinema forever despite having only come down to us in a fragmentary condition; a filmmaker reputed to be a loose cannon who, according to legend, was broken by the Hollywood system. He was the archetype of the accursed filmmaker, in other words.

The man was supposed to be the very personification of authenticity because he merely made films dealing with his own experiences and, as an actor, simply played his former self. However, he turned out to be at once a brilliant impostor and an immense artist who had worked hard to breathe life, one film at a time, into the fascinating character he had invented and who had fooled all and everyone until his last day.

In 1966, Denis Marion found out that Count Erich Hans Oswald Karl Maria Stroheim von Nordenwall was in fact the son of a humble Jewish hatter from Vienna and that his aristocratic particle was only a figment of his own imagination. Afterwards, other scholars stepped up to the plate and unearthed the academic and military parts of Stroheim’s past. It turned out that he had been a young man more gifted for languages than for economics, whose dreams of becoming a dragoon were shattered because he was of the Jewish persuasion. Even if the reasons that made him emigrate to America in 1909 still remain poorly known, it is safe to assume that they were related to his rejection of the life that lay ahead of him and to the antisemitism that held sway in Vienna at the time.

In a filmed interview, Marcel Dalio – who had never made a secret of his own Jewishness – expressed, in rather blunt fashion, his point of view on the man he knew quite well, showing a remarkable understanding of the endless vacillations that, according to him, haunted Stroheim: “He knew that he was somebody. Because he played all the life (sic) to be somebody. He is his own creation. He is his own father and mother, and that’s what he wanted. No friends, no wives, no mistresses: nothing! Stroheim–married to Stroheim, in love with Stroheim. But he paid the price…” For his part, the cinema historian Herman G. Weinberg praises the richness of the mosaic assembled by Stroheim: “I think it makes him [Stroheim] all the more fascinating…and I would be disappointed to learn that…he was, indeed, what he said he was.” Altogether, the famous filmmaker seems to remain as elusive as the title character of Citizen Kane, his own person as well has his work being only enriched by the contradictions they are steeped in.

Newspaper ad for the American film Foolish Wives (1922) on page 5 of the April 1, 1922 Duluth Herald. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Newspaper ad for the American film Foolish Wives (1922) on page 5 of the April 1, 1922 Duluth Herald. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.These contradictions were apparent in the 1921 film, Foolish Wives. The film takes place in Monaco and has falsehood as its central theme. A bogus Russian count and two equally bogus princesses deal in counterfeit money, cultivate duplicity and fake a whole range of sentiments. For the sake of realism, Stroheim chose to recreate the Monte Carlo Casino down to its minutest details.

On the opposite side of his directorial process, when he set about making Greed, his very next film, he hired non-professional performers, decided to shoot entirely on location, in the very places in which the events depicted in the plot took place. Stroheim claimed that “life isn’t something to be recreated but to be captured.” A problematic that belongs to the private sphere can go way beyond the person of an artist to spread throughout his entire work.

Stroheim is not only a major figure of cinema worldwide. He is also the author of an oeuvre that contains extremely modern artistic problematics: lying and creating; the truth in art–that is as a construction. This also relates to the modern notion of self-image, the image one constructs of oneself for the benefit of others but also as a way of finding oneself, at the risk of getting lost in the process.

Featured Image: Erich von Stroheim and Mae Busch in Foolish Wives, 1922 publicity still by Universal. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

This blog post has been translated by Civan Gürel.

The post Erich von Stroheim, the child of his own loins appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers