Oxford University Press's Blog, page 315

October 7, 2017

Pushed to extremes: the human cost of climate change

Across the Western world, many democracies recently faced turbulent election cycles, which saw increasing prominence of far right nationalist groups that were previously relegated to the fringe of social and political thought. Though each respective group supported a fervent nationalist agenda that promoted isolationist policies such as the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union or the Trump Administration’s promise to ban certain refugees and build a wall on the southern border, they also embraced a similar ideology. That ideology used the foreign nationalist, migrant worker, and above all the refugee, as the scapegoat for economic depression, weakened infrastructure, unstable job markets, and threats on national security. A new form of false patriotism has emerged in which anything and anyone perceived as a foreign entity is to be rejected or expelled. As a result, racism, ethnocentrism, and unabated xenophobia has taken center stage in national dialogues about what and who constitute American identity.

In the United States alone, undocumented immigrants, Muslims, refugees, foreign nationals, and Latinx groups have all found themselves on the receiving end of this hate and fear mongering. However, a parallel and equally disturbing trend is happening ecologically in the US, with the rejection of climate change science and the withdrawal from the Paris Accord. Though climate change may at first appear to be a separate issue from the xenophobia and anti-refugee mindset, they are more inextricably tied to one another than we are led to believe.

If one examines the Trump campaign and current agenda specifically, two hallmark issues have always stood out as emblematic of the image of what and whom they represent: banning refugee resettlement and total rejection of climate change policies. For supporters of Trump, both were to be scorned as they served as external threats to their perceived American cultural identity and national sovereignty. An identity that is overwhelmingly white and set apart from the multicultural populations of immigrants and refugees, who would have been afforded certain protections by “the globalists” like Hillary Clinton. Refugee resettlement as a whole falls under the auspice of the United Nations, which supersedes the bounds of individual nation states. Climate change agreements like the Paris Accord are similar in structure in that they convene in foreign nations, represent a globalist mentality, and hold individual nation states responsible to carry out international laws. Trump’s repeated mantra “I’m for Pittsburgh not Paris” encapsulates more than just the Paris Accord itself-it became an idiom for patriotism. Refugee resettlement and climate change were slowly and meticulously merged into one looming globalist threat on the very stability and identity of the United States itself.

Paris Protest by kellybdc. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Paris Protest by kellybdc. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Ironically, by rejecting climate change and the movement toward a progressively “green” economy, Trump is all but ensuring an increase in refugees as well as internally displaced people within our own country. In many areas of the world, dramatic rise in sea levels are already causing mass displacement such as the case in island nations of the South Pacific. The current influx of refugees from war stricken or politically unstable areas in the Middle East and North Africa is as much an ecological outcome as it is a political one. Global warming did not cause the Arab Spring, but scientific evidence has proven that unstable weather patterns caused by atmospheric warming contributed to widespread and catastrophic droughts in the year prior to the first Arab Spring protests. That drought led to a global market rise in the cost of wheat, the most important food staple in much of the Arab world, that combined with weak infrastructures and pathetic job markets made eating bread an impossible hardship for many. In places like Iraq which faced severe water shortages, ISIS recognized the water stricken Sunni majority western provinces as more easily receptive (at least initially) to their presence by arriving with much needed water and food staples. They were thereby projecting the largely Shia controlled Baghdad government as ineffective and prejudiced. When local communities became horrified with their manner of control, ISIS then cut off their access to water and food rendering them completely helpless. The choice to stay or to attempt to flee both come with the certainty of persecution and a very real risk of death, but only the latter option offers a glimmer of hope for a better life in peace and security.

The UN currently does not recognize “climate refugees”, therefore any who flee an area due to ecological reasons is labeled a migrant and thereby not afforded legal protection from international bodies. There are also no proactive solutions to ebbing the flow of such displaced people if we only view these areas of conflict through the lens of politics alone. There must be a holistic approach to such issues that takes into account how environmental disasters play into conflict and human migration. If we take the Trump approach and reject both, catastrophic environmental disasters will continue unabated and that will in turn contribute to not only more refugees, but also internally displaced people within the United States. Hurricanes Katrina, Harvey, Irma, and Maria, Super storm Sandy, raging California wildfires, Midwestern droughts, and unprecedented flooding have already displaced millions of people, caused untold amounts of damage, and are only increasing in intensity and occurrence.

This is no longer a “foreign” issue, but the “us versus them” mentality will manifest within our own borders-indeed it already has. Who receives emergency aid, who is able to safely evacuate and return, who are able to receive government assistance to rebuild their lives in the wake of such disasters will speak volumes as to who is valued.

Featured image credit: March protest rally by The Climate Reality Project. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Pushed to extremes: the human cost of climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

Does anyone know what mental health is?

The concept of mental health lives a double life. On the one hand it denotes a state today universally valued. Not simply valued but newly prioritised by governments, hospitals, schools, employers, charities and so on. Expressions such as “mental capital” or “mental wealth of nations” appear in official reports and high profile articles emphasising the importance of public policy aimed directly at enhancing mental health. You’d think that when something is so valuable and so uncontroversially prized, there’d be an accepted definition of it. I am not asking for knowledge of the nature mental health and its causes, just a statement of what counts and doesn’t count as mental health. After all it’s hard to value something when you don’t know what to point at when you name it. And yet when you look closely at the existing efforts to define mental health, all you see is a multitude of definitions being bandied around with little consensus. Mental health appears to be prized more as a label than as a concept.

On the face of it the World Health Organisation appears to provide such a definition:

Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.

This statement harks back to WHO’s definition of health which appeared in its 1948 constitution: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Mental health according to WHO is also a positive state: it is not enough to be free of depression, anxiety or schizophrenia, or any other diagnosable psychiatric condition, you also need to be well enough to thrive and flourish in your community.

Moved by similar considerations a growing number of public health scholars also identify mental health with “wellness” or “mental well-being.” This development probably stems from the rise of positive psychology – a field of social science that in the last decades has positioned itself as a science of well-being. Proponents of positive psychology like to say that the methods of measurement and data analysis have progressed so much that now it becomes feasible to have a science of happiness, flourishing, satisfaction, and fulfilment. One popular scale for measuring “mental well-being” is the Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale which asks people to judge the extent to which they feel optimistic, effective, useful, relaxed, able to get along with other people and to make up their mind about things.

But notice how different all these ideas are. WHO’s expansive definition describes a life that’s functioning in harmony with the norms of a given community – these norms set what counts as normal stress, productive work, and contribution to society (I hope the WHO realises the relativity of this definition to social norms, and some very modern ones at that). It is an explicitly objective definition in that it demands that the person actually meets these standards not just thinks they do. The Warwick and Edinburgh scale on the other hand is entirely subjective – it measures people’s own sense of their personal effectiveness for going through with basics of life. But if you look closer you’ll notice the difference between this sense of personal effectiveness on the one hand, and subjective well-being on the other. Intuitively the latter refers to our emotional well-being, our happiness, our fullness of heart, joy and contentment. Feeling happy takes more than just patting yourself on the back for being effective. And yet it is also common to come across this happiness-based definition, such as when mental health charities advertise “pathways to well-being” through engaging in those activities that maximise happiness.

Mental health appears to be prized more as a label than as a concept.

To take stock, there are at least three definitions here: functioning according to norms of society, feeling personally effective, and being happy. And that’s not counting the definition all of these three oppose – mental health as mere absence of psychiatric disease. Ironically it’s the latter much maligned minimalist definition that does much of the work when it comes to policy and advocacy. On the WHO website, just under their ambitious definition, we are invited to check out the top ten facts about mental health. With a few exceptions all these facts are actually about mental illnesses – how costly they are economically, how they exacerbate existing inequalities, and how much needs to be done to address them. Those few facts that are phrased in terms of mental health – for example, “Fact 8: Globally, there is huge inequity in the distribution of skilled human resources for mental health” – do not in fact need a definition of mental health in any other terms than absence of illness. It’s as if the positive definition is largely superfluous to the good efforts the WHO is advocating.

In my estimation this is a common pattern. The long search for a positive definition of mental health (the debate started after World War II and is ongoing) is a struggle to balance cross-cultural applicability, measurability, and conceptual validity. There are many valiant attempts, each of which faces basically the same objection: depending on context, being unhappy, idle, indecisive, or anti-social can be perfectly mentally healthy. Few people deny that defining mental health takes a value judgment, but which value judgments are robust enough to do this job is still a mystery.

Meanwhile the worthy work helping people with mental illness proceeds relatively untouched. This summer I attended an event in London at which academics, doctors, service providers, patients and their families were tasked with finding a standard by which a mental health intervention should be judged, i.e. what outcomes matter for evaluation of the state of a young person with mental illness. Karolin Krause of University College London listed twenty four different outcomes on a big poster – two of them were negative (having fewer symptoms and engaging less in harmful behaviour) and the rest were various shades of positive outcomes, from ability to focus, to getting on with others, feeling understood, etc. Krause asked participants to put stickers next to the outcomes they consider most important. At the end of the day the two negative outcomes, though they had many positive competitors, won the plurality of votes.

Arguments about the proper positive definition of mental health will rage on. But in the meantime just freedom from illness can be quite enough.

Featured image: Lake Water by Tyler Sturos. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Does anyone know what mental health is? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 6, 2017

Moses Jacob Ezekiel, Confederate soldier and American Jewish sculptor

Every few months brings news about the Confederate flag or Confederate monuments, and their legitimate or illegitimate place in American culture. Last spring lawmakers unsuccessfully urged The Citadel to take down the rebel flag that flies on the school’s campus, arguing that the school not be entitled to government money as long as the flag remained on view. In December 2016 a soaring, 70-foot tall Confederate monument, topped by a statue of Confederate States of America President Jefferson Davis and standing near the University of Louisville, was moved to a less visible location. This May saw the city of New Orleans removing the final of four Confederate monuments in the city, which included statues of Confederate General Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. Recent weeks have provoked an impassioned debate about the hundreds of remaining monuments on American soil, initiated by white supremacists protesting the removal of a statue of General Lee in Charlottesville.

Surely the most visible monument to the Confederacy stands at Arlington National Cemetery. Unveiled in 1914 and measuring 32-feet tall, the classically styled and highly allegorical bronze monument rests 400 yards away from the Tomb of the Unknown Solider. Comprising over thirty life-size figures and topped by a woman holding forth a laurel wreath of victory, the monument was sculpted by Moses Jacob Ezekiel, an American-born Jew of Sephardic ancestry and a cadet who fought in the Civil War.

While it comes as a surprise to many, a fair number of Jews did, in fact, support the Confederacy. The Confederate Secretary of State was a Jew named Judah Benjamin, who served earlier as Attorney General of the Confederacy and the Confederacy’s Secretary of War. Numbers differ, but historian Robert Rosen estimates that approximately 2,000 Jews fought on the Confederate side. Ezekiel offers one of the most public and prominent examples of a Jew who straddled the line between the values of his religion and a misplaced patriotism.

Born in Richmond, Ezekiel was the first Jew to attend the Virginia Military Institute. Serving as a cadet in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, Ezekiel fought in the bloody Battle of New Market. Although his family owned no slaves, Ezekiel allied with the Confederacy because, as he wrote in an after-the-fact evasion, he believed that each state should make its own autonomous decisions: “None of us had ever fought for slavery and, in fact, were opposed to it. . . . Our struggle . . . was simply a constitutional one, based on the constitutional state’s rights and especially on free trade and no tariff.” Regrettably, while coming from his own place of oppression, and grateful for the freedoms afforded Jews by living in America, Ezekiel was not immune to prejudicial thinking.

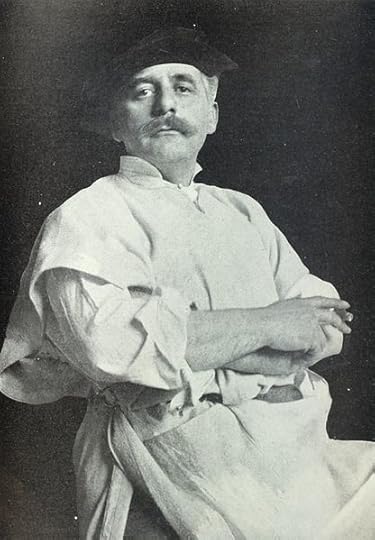

Portrait of Moses Jacob Ezekiel, 1909. The World’s Work, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Moses Jacob Ezekiel, 1909. The World’s Work, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Ezekiel’s portraits of American political luminaries affirm his fervent patriotism and grateful commitment to his native country. A proud Southerner, Ezekiel was disappointed when he was not asked to sculpt Robert E. Lee, whom he knew personally and socialized with after the war. According to Ezekiel’s autobiography, none other than Lee had encouraged him to pursue a career in art. He quoted the general: “I hope you will be an artist as it seems to me you are cut out for one. But whatever you do, try to prove to the world that if we did not succeed in our struggle, we are worthy of success. And do earn a reputation in whatever profession you undertake.”

Among the sculptures that Ezekiel did carve of prominent American figures are three portraits of Thomas Jefferson, a fellow Virginian. He first carved a marble bust (1888) for the Senate’s Vice Presidential Bust Collection. A later commission — from two Jewish philanthropist brothers –resulted in a nine-foot bronze statue of Jefferson, originally placed in front of the Jefferson County Courthouse in Louisville (1901). A smaller replica of that Jefferson sculpture (1910) was erected near the Rotunda at the University of Virginia, founded by Jefferson in 1819.

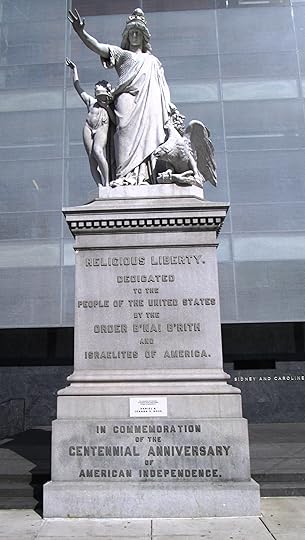

Jefferson stands atop the Liberty Bell, as drafter of the Declaration of Independence, holding the document outward. Ezekiel depicted Jefferson in his thirties, the future president’s age at the time when he wrote the Declaration. As a man who epitomized democratic ideals and who authored the Virginia Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, Jefferson stood for the very religious liberty that Ezekiel celebrated with his first major commission: a neoclassical, 25-foot allegory of Religious Liberty, which sits on the grounds of the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, beside Independence Mall. The sculpture was a commission from the Jewish fraternal organization B’nai B’rith in 1874 on the occasion of the upcoming 1876 Centennial Exposition.

Religious Liberty statue in front of the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, 1876. Beyond My Ken, 2013, GNU Free Documentation License via Wikimedia Commons.

Religious Liberty statue in front of the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, 1876. Beyond My Ken, 2013, GNU Free Documentation License via Wikimedia Commons.Allegorical in conception, the monument presents the classicized Liberty as an eight-foot woman wearing a cap with a border of thirteen stars to symbolize the original colonies. In one hand she holds a laurel wreath and the other hand extends protectively over the idealized young boy at her right, a personification of Faith who holds a flaming lamp. At Liberty’s feet an eagle representing America attacks a serpent symbolizing intolerance, and Faith steps on the serpent’s tail. The group stands on a pedestal that bears the inscription “Religious Liberty, Dedicated to the People of the United States by the Order B’nai B’rith and Israelites of America.”

Ezekiel was a study in contradictions: A fervent American and yet an expatriate for forty years, and a sculptor of religious liberty and yet an ardent memorializer of the Lost Cause. As an artist remarkable for his unique place in American history and in American art, Ezekiel opens up a conversation about how a Jew — an Other — can be an oppressor of a different Other. Victims of enslavement and prejudice, Jews seem unlikely supporters of white domination and oppression. Ezekiel also opens up a conversation about the place of Jewish American artists and of the place of Jewish art in a religiocultural heritage without a long history of artistic production. As Ezekiel aptly observed in his autobiography: “The race to which I belong had been oppressed and looked down upon through so many ages, I felt that I had a mission to perform. That mission was to show that, as the only Jew born in America up to that time who had dedicated himself to sculpture, I owed it to myself to succeed in doing something worthy in spite of all the difficulties and trials to which I was subjected.”

Featured Image credit: detail of the northwest frieze of the Confederate Monument by Moses Jacob Ezekiel at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. Tim1965, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Moses Jacob Ezekiel, Confederate soldier and American Jewish sculptor appeared first on OUPblog.

Fire prevention: the lessons we can learn

The United States spends more on health than any other economically comparable country, yet sees a consistently mediocre return on this investment. This could be because the United States invests overwhelmingly in medicine and curative care, at the expense of the social, economic, and environmental determinants of health—factors like quality education and housing, the safety of our air and water, and the nutritional content of our food. A deeper investment in contextual factors like these can help create healthy societies and prevent disease before it occurs. However, in making the case for this investment, it is important to make clear that a shift towards stopping disease before it starts does not mean pulling resources away from doctors and hospitals—our first line of defense when disease strikes. We need only look at the history of fire prevention in the United States to see how prevention does not have to come at the expense of cure. The issue of fire prevention has been much in the news lately, in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire in the United Kingdom. Despite the occurrence of such tragedies, however, the history of fire prevention in the United States has largely been an encouraging story, and instructive for the prevention vs cure debate. Over the years, we have managed to dramatically reduce fires, while at the same time maintaining a robust investment in the women and men who put them out when they happen.

Firefighting has a long history, dating back to the Roman era. However, modern fire prevention is largely the result of two tragedies that occurred on 8 October 1871. That was the day that both the Great Chicago Fire and the Wisconsin Peshtigo Fire broke out. The Great Chicago Fire took the lives of over 300 people; left 100,000 homeless; destroyed over 17,400 structures; and burned through over 2,000 acres. The Peshtigo Fire—the worst forest fire in US history—destroyed 16 towns and claimed over 1,000 lives. These blazes were so destructive that they changed attitudes towards fire safety in the United States. Not long after the Great Chicago Fire, the city began to mark the anniversary of the event with festivities. On the fire’s 40th anniversary, the Fire Marshals Association of North America chose to formalize the occasion, using the day to promote fire prevention education. Starting in the early 1920s, Fire Prevention Week has been marked annually on the Sunday through Saturday period during which 9 October falls. The week usually has a theme linked to fire prevention and emergency planning, such as having an emergency route worked out to escape in the event of fire. Fire Prevention Week would go on to become the longest running public health and safety observance on record. Calls for a prevention focus, with firefighters taking a leading role in these efforts, were also amplified in the media during the 1920s, further publicizing the call to stop fires before they start.

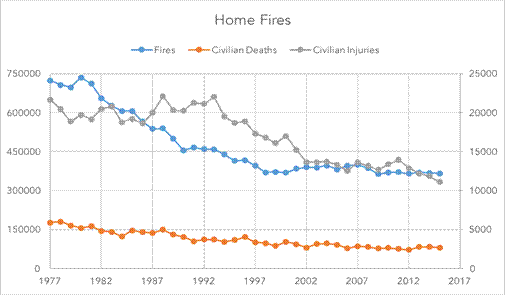

Figure 1. Home fires data from the National Fire Protection Association. Recreated by the author, used with permission.

Figure 1. Home fires data from the National Fire Protection Association. Recreated by the author, used with permission.Since then, fire prevention has become an important part of how we view fire safety in the United States and made a clear difference in the number of deaths and injuries caused by fires. In 1977, there were 723,500 home fires in this country, with 5,865 civilian deaths and 21,640 injuries. In 2015, those numbers had been cut to 365,500 home fires, with 2,650 civilian deaths and 11,075 injuries (Figure 1).

The success of prevention has not been limited to reducing home fires. Between 1980 and 2013, vehicle fires declined by 64 percent, and building fires declined by 54 percent. Prevention has also made a difference in cites, like New York City, where fire deaths reached their lowest number in a century last year, at 48 deaths. This represents a notable decline from New York’s 1970 peak of 310 deaths.

Why has prevention been so effective? Most fires are caused by correctable human error, or the absence of safety systems like smoke alarms and sprinklers. For this reason, preventive steps like fire education and installing smoke alarms can do much to create a safer environment. Simply adding smoke alarms, for example, can reduce the risk of dying in a reported home fire by half. Fire education can help to discourage unsafe behavior, and encourage individuals and families to develop a means of escape in the event of fire.

Critically, the success of these efforts has not come at the expense of the people and organizations who fight fires when prevention falls short. Quite the opposite— as we have reduced the number of fires, the number of firefighters has actually increased. Despite the fact that there are 50 percent fewer home fires than there were 30 years ago, there are about 50 percent more career firefighters; 237,750 in 1986 to 345,600 in 2015.

Matchstick House by Myriams-Fotos. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

Matchstick House by Myriams-Fotos. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.The United States has also seen an increase in the number of fire departments consisting of career or mostly career firefighters, rising from 3,043 in 1986 to 4,544 in 2015. This represents an increase of 49.3 percent. This increase has roughly coincided with a rise in government expenditures on local fire protection. Adjusted for inflation, this spending increased by 170 percent between 1980 and 2014, rising from $16.4 billion to $44.2 billion.

The history of fire prevention in the United States demonstrates that the rise of prevention does not necessitate the decline of cure. Our investment in reducing fires by creating an environment where they are less likely to occur has clearly paid off, yet this success has not changed our commitment to maintaining a network of professional firefighters, ready to respond in case of emergency. Further, we have managed to integrate a prevention focus into the work of these professionals— local fire departments often play a leading role in promoting prevention—demonstrating that the priorities of prevention and cure are not mutually exclusive.

What is the takeaway here for health? In the United States, our investment in population health vs curative care does not come anywhere near the balance struck by our fire preparedness infrastructure. Rather, our investment is deeply lopsided in favor of cure. The argument for greater focus on population health is not a case against this investment, it is a case against this lopsidedness. It stresses that a world with fewer “fires”—less disease—is beneficial to us all, even as we wish to always have well-resourced professionals on hand who can put out fires when they happen, and cure disease when it strikes. Such a world would reflect the high value we place on health, as we pursue wellbeing using every tool at our disposal, with prevention and cure working together to create a safer, healthier society.

A version of this post was originally published on Fortune.

Featured image credit: Firefighter by shutterbean. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Fire prevention: the lessons we can learn appeared first on OUPblog.

The frailty industry: too much too soon?

Fashions come and go, in clothing, news, and even movie genres. Medicine, including geriatric medicine, is no exception. When I was a trainee, falls and syncope was the “next big thing,” pursued with huge enthusiasm by a few who became the many. But when does a well-meaning medical fashion become a potentially destructive fad? Frailty, quite rightly, has developed from something geriatricians and allied professionals always did to become a buzz word even neurosurgeons bandy about. No bad thing for all professionals who see older people to have awareness of the recognition and management of this vulnerable and resource-intensive patient group. But increasingly vast amounts of resource are being devoted to the creation of frailty-related services for our older population in the absence of a sound evidence base. Indeed, recent studies quite rightly state that the evidence base for frailty (and the related “intervention” Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment) reported Edmonton Frailty Scale (REFS) is at best sketchy, with little apart from exercise making much of a difference, never mind any evidence at all of cost effectiveness.

So how did we get to this position, where front door frailty units, frailty clinics, frailty services for non-medical specialties, and the like are funded simply because they sound like a good idea? Partly an understanding of the pressing need to care for this patient group better, with many including a burgeoning number of trainees finding a cause to identify with; partly charismatic and passionate leadership; partly BGS sponsorship; and partly I suspect a bandwagon effect, particularly in the research arena, where frailty commands the older people’s medicine agenda spectacularly.

While advocating passionately for our patients, we must be honest about what we can and can’t achieve, and refuse to deliver services that we do not have an evidence base to support.

We have a threefold responsibility in relation to frailty (and indeed all other areas of practice): first, to care for those with frailty with expertise and compassion; second to develop the evidence base for frailty identification and management; and third to operate within our knowledge and evidence base to ensure rational resource use. We are not delivering on the third. We should. The evidence base for falls and syncope grew over time, but in an era when we had the luxury of trying new service models that made clinical sense without the financial pressures of the current NHS. While advocating passionately for our patients, we must be honest about what we can and can’t achieve, and refuse to deliver services that we do not have an evidence base to support. That is not to say that we should not serve frail patients expertly, within what we know. But we must not allow frailty to exclude other aspects of good patient care; by way of example, the prevention agenda is barely acknowledged currently within the BGS, the wider older people’s medicine professional community and the research arena related to older people, where frailty and that dreadful term “multimorbidity” hold sway.

A challenge for frailty aficionados – when did you ever make someone with moderately severe frailty less frail? Having asked many colleagues, from learned professors to jobbing geriatricians, juniors to seniors, BGS office bearers to allied professionals, the only one with a resounding affirmative response was a personal trainer running exercise classes for older people in the community. It is time for the frailty fad to own up to its fallibility and allow the fashion pendulum to swing in other directions, while not neglecting this vital component of geriatric medical care.

A version of this article was originally published on the BGSBlog.

Featured image credit: Elderly by StockSnap. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The frailty industry: too much too soon? appeared first on OUPblog.

Composer David Bednall in 23 questions- part 1

David Bednall is Organist of the University of Bristol, Sub Organist at Bristol Cathedral and conducts the Bristol University Singers. He has a busy career as a composer and has published many works. In this occasional series we ask Oxford composers questions based around their musical likes and dislikes, influences, and challenges. In the first of a two part Q&A we spoke with David about his typical day, his composing habits, and his most difficult work to write.

What does a typical day in your life look like?

This is very difficult to answer! They are very varied. I’m not a morning person, so my days do not usually end up starting very early… I like to get through the letters, arts, and cryptic crosswords sections of the papers with breakfast and a huge mug of tea in the mornings. What I do next will then depend entirely on whatever else is on that day. I am often teaching at Bristol University, playing for evensong at Bristol Cathedral, or doing something else musical. I like to have a walk around the city each day, and I try to be in bed for Sailing By and the Shipping Forecast.

What do you like to do when you’re not composing?

I’m a keen fan of music across the spectrum, so even when I’m not composing I may well be practising, reading about music, or getting to know pieces better. I’m also a great fan of TV Detective Series and box sets. Inspector Morse is an all-time favourite along with The Sopranos, and I’m currently working through The Wire. I’m interested in current affairs so try and keep up with the world, and I like to read New Scientist each week to find out what’s new. Reading is also a hugely enjoyable pastime for me.

What is the most difficult piece you’ve ever written and why?

I would say that each piece presents its own difficulties. The toughest in some ways was my 40–part motet Lux orta, which was written for Tom Williams and Erebus for the Bristol Proms 2015. The sheer size of the forces was a challenge in itself, and then were the practicalities of writing out the music (it takes several minutes to simply write a tutti chord with this many voices!). In addition, my hope that Lux Orta would be rehearse-able in a short space of time and prove to be a useful companion to Tallis’s Spem in Alium provided further difficulties. I spent a lot of time studying Spem, of course, and also Gabriel Jackson’s Sanctum est verum lumen before drawing up a big series of maps to decide what I was going to do and how I might go about it. It all seemed to happen, but involved a fair period of sleepless nights when I could think of nothing else – I even walked around town counting ‘alleluias.’ My Stabat Mater, from a similar time, was also very difficult to write as the length of the text makes it very difficult to do justice to; I really wanted to make a ‘whole’ out of the piece so that it hung together over the near hour of its duration. The writing of these pieces is certainly one of my proudest achievements.

David Bendall. Used with permission.

David Bendall. Used with permission.

[image error]

What is the most exciting composition you’ve ever worked on and why?

The above two, and also the Nunc dimittis that I wrote to accompany Finzi’s Magnificat. It is really an extended love letter to Finzi, and I was so deeply honoured to be asked to do this work. I adore Finzi, so it was lovely to write this piece and be permanently associated with him.

What is your inspiration/what motivates you to compose?

I tend to need a deadline to really get down to work. With choral music the inspiration is always the text, and I’m motivated by the desire to do this text as much justice as possible in my setting. When I don’t have a text to set, I often like an image to work towards (I usually want to try and work out a title before moving forwards with the writing). The countryside of Gloucester and my native Dorset are important, and also the sounds of voices in cathedral spaces.

How do you prepare yourself to begin a new piece?

If it’s a choral piece I write the text out by hand in fountain pen, as I find this helps me consider and feel closer to the words. I try and think a lot about the kind of piece and the kind of effect I want to create before writing. Lots of tea and procrastination mark the following stage, and then after that I begin composing at the piano. I write everything in pencil and use Sibelius only at the last stage – the working by hand is essential for me.

How do you begin to approach a new commission?

Much the same as above, but I would try to carefully consider the type of piece and the forces available for it. I never try and dumb down, but if it is a small amateur choir looking for a useful piece to do frequently then I would want to try and write differently to a commission for an expert group who want me to write them a showpiece.

Do you treat your work as a 9-5 job, or compose when you feel inspired?

Very much when inspired – 9 is not a time I really ever use!

What does success within a composition look like to you – how do you know when to stop editing a piece and that you’ve reached the end?

I think it is fine to do some tweaking after you first hear your piece played or within a short time frame. If you continue doing so long after the event, however, then you are almost tampering with someone else’s work. I likened it in my PhD commentary to going through a family photo album and trying to remove embarrassing hairstyles and jackets – you have to accept them for what they are. If something doesn’t work in terms of scoring, say, then that is different, but you can often end up changing things for the worse. That said, you do get stricter with experience and feel that every element of a piece needs to ‘belong.’ Overall, it’s important to leave a work or you never move on – making a recording is often a good opportunity to force yourself to leave it, I think.

Featured image credit: mistake error correction wrong by stevepb. Public domain via pixabay .

The post Composer David Bednall in 23 questions- part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Why do so many people believe in miracles?

In 2013, a five-year-old Brazilian boy named Lucas, fell 6.5 meters from a window, while playing with his sister. His head hit the ground, which caused a loss of brain tissue. Lucas fell into a coma and his heart stopped twice. The doctor had told Lucas’ parents that the boy would likely not survive, and that even if he had survived he could remain in a vegetative state. To the astonishment of everyone involved, however, he woke up soon after and was discharged from the hospital only a few days later.

Lucas’s family believe that his miraculous survival was due to their prayer to Francisco and Jacinta, Portuguese children who lived for only nine and ten years, respectively, at the beginning of the twentieth century. On 13 May 1917, in the small town of Fátima, the two children witnessed an apparition of the Virgin Mary. They reported that she looked “brighter than the sun, shedding rays of light clearer and stronger than a crystal goblet filled with the most sparkling water and pierced by the burning rays of the sun.” Mary appeared to them several times afterwards and shared secrets with them which included, among other things, predictions of the end of World War One and the start of World War Two. On 13 May this year—exactly 100 years after the first apparition—some half million people gathered at Fátima. Pope Francis canonised these children there on the basis of their posthumous miracles, including the cure of Lucas.

Belief in miracles, such as the ones mentioned above, is widespread. According to recent surveys 72% of people in the USA and 59% of people in the UK believe that miracles take place. Why do so many people believe in miracles in the present age of advanced science and technology? Let us briefly consider three possible answers to this question.

The first possible answer is simply that miracles actually do take place all the time. If they take place all the time it is not a surprise that many people witness them and believe in them. However, philosophers widely agree that miracles always involve a violation of the laws of nature. Such acts as healing a fatal injury instantly or turning water into wine are considered miracles primarily because they violate the laws of nature—they cannot be performed without defying the laws of physics, chemistry, biology and so on. Yet nature is a uniform and stable system. If the laws of nature were regularly violated, we would not be able to speak, walk, or even breathe. Hence, even if miracles can occur in principle, they simply cannot occur regularly.

The second possible answer is that belief in miracles is a projection of wishful thinking. According to this answer, many people believe in miracles because they want to think that they take place. There is some truth in this answer. One can argue that belief in miraculous healing is particularly common because people want to remain hopeful even when they suffer a serious illness or injury. However, it is not clear why so many people would believe something merely because they want it to be the case. For example, many people want to become millionaires but few believe that they are millionaires, unless they really are.

Believing in miracles seems to be incompatible with modern life.

The third answer is that belief in miracles has cognitive and developmental origins. According to recent psychological research, a cognitive mechanism that detects violations of the laws of nature is in place as early as infancy. In one experiment, two-and-a-half-month-old infants consistently showed ‘surprise’ when they witnessed their toys appearing to teleport or pass through solid objects. Some psychologists even argue that such a violation of expectations creates an important opportunity for infants to seek information and learn about the world. In these experiments, infants spent more time exploring toys that violated their expectations than toys that did not. Some of them were even eager to test their ‘hypotheses’ by banging the toys that appeared to pass through a wall or drop the toys that appeared to hover in the air. Some psychologists also argue that belief in miracles has survived for a long time because miracles have a common character: ‘minimal counterintuitiveness.’ That is, well-known miracles often deviate slightly from intuitive expectations but do not involve overly counterintuitive elements. They spread successfully through generations because while they offer an idea that is challenging enough to attract attention, they also avoid over-taxing people’s conceptual systems. The hypothesis of minimal counterintuitiveness has been supported by psychological experiments. Many well-known miracle stories—such as Jesus walking on water and Muhammad instantly restoring the sight of a blind person—are indeed minimally counterintuitive because they are only slightly counterintuitive.

The third answer, which appeals to the cognitive and developmental origins of belief in miracles, seems to be most compelling. It is important to note, however, that this answer does not imply that miracles can never take place. Consider a parallel example: Suppose that psychologists discover that hungry people tend to see illusions of biscuits in their cupboards. This does not mean that whenever hungry people see biscuits in their cupboards they are seeing illusions. It may well be the case that they really do have biscuits in their cupboards. Similarly, even if psychologists can explain that there are cognitive and developmental origins of miracle beliefs, whether miracles can actually take place is a separate question.

On the face of it, believing in miracles seems to be incompatible with modern life. It seems unlikely, however, that they will disappear any time soon as they have deep cognitive roots in human psychology.

Featured image credit: sky light cloudy miracle by Ramdlon. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Why do so many people believe in miracles? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 5, 2017

A prison without walls? The Mettray reformatory

The Mettray reformatory was founded in 1839, some ten kilometres from Tours in the quiet countryside of the Loire Valley. For almost a hundred years the reformatory imprisoned juvenile delinquent boys aged 7 to 21, particularly from Paris. It quickly became a model imitated by dozens of institutions across the Continent, in Britain and beyond. Mettray’s most celebrated inmate, gay thief Jean Genet depicts it in his influential novel Miracle of the Rose [1946] and it is also featured at the climax of philosopher Michel Foucault’s history of modern imprisonment, Discipline and Punish [1975]. The boys worked nine-hour days in the institution’s workshops – making brushes and other basic household implements; they dug its fields and broke stones in its quarries. Such labour was thought conducive to moral reform but it also enabled the institution – which was run by a profit-making private company – to balance its books. In his seventies, Jean Genet suspected that the reformatory was doing rather more than this: making then concealing huge profits from its forced labour. He set about, with a small team of helpers, trying to prove this by plundering the institution’s archives as well as reading widely in the historical sources. The result, The Language of the Wall, was a script for a three-part historical documentary drama for television which retells the story of Mettray from its foundation to its closure as a prison in 1937. Genet could find no hard evidence of profiteering but he dramatizes his own search for it in the script and retells the life of the institution over the hundred years by intertwining often violent incidents from the daily lives of prisoners with scenes from the corridors of power to show how closely the private institution worked alongside the state and how it survived successive changes of regime.

My return to Mettray’s archives in Tours was guided by Genet’s still unpublished script, versions of which are held at the regional archives in Tours and at IMEC. Although Genet rightly ridicules him for his reactionary politics, it is difficult not to admire the technical accomplishment of Mettray’s principal founder, the devout Frédéric-Auguste Demetz. Demetz had been sent to the United States by the French government with prison architect Abel Blouet in 1836 to follow up Alexis de Tocqueville’s earlier visit, the official purpose of which had been to investigate American prisons. Demetz and Blouet were to obtain more precise technical information about them, including detailed drawings.

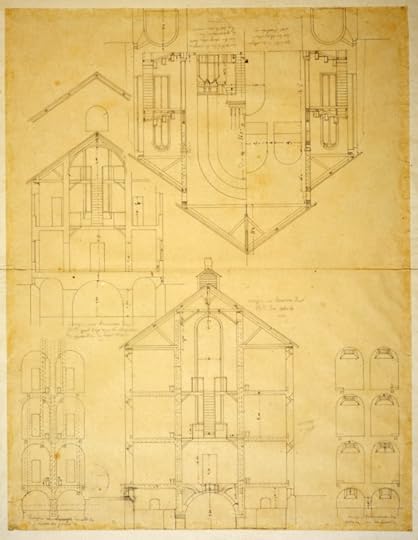

Abel Blouet, Maison Paternelle et Chapelle de la Colonie plan élévation, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J173

Abel Blouet, Maison Paternelle et Chapelle de la Colonie plan élévation, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J173Blouet subsequently produced drawings for Mettray’s chapel building which show cells in the crypt, as well as in the building behind, a unit which the institution ran as a money-making enterprise by encouraging middle-class families to send wayward sons for a short spell of “paternal correction,” during which they experienced individual tuition and could also hear Mass in the adjacent chapel from the privacy of their cells without having to mix with the working-class delinquents in the chapel. Demetz was a brilliant publicist for his institution, marketing it and carefully managing its visibility to the outside world. He boasted that Mettray was “sans grilles ni murailles” (without bars or walls) and in one sense this was true: there was no perimeter wall, yet in addition to the punishment cells concealed in the chapel and elsewhere there were frequent roll-calls and escapees were rounded up by the local peasantry, alerted by the ringing of the chapel bell, and incentivized by the payment of a reward. Sometimes they killed escapees. Demetz welcomed philanthropic tourists but only on Sundays, when they witnessed the institution’s weekly military parade, La Revue du Dimanche.

Colonie de Mettray – La Revue du Dimanche, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J344.

Colonie de Mettray – La Revue du Dimanche, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J344.The institution provided a hotel and even postcards for visitors to spread the news of its success in taking wayward criminal children and remoulding them into disciplined servants of the established order: inmates could leave Mettray a few years early if they joined the armed forces so many did, becoming troops in the colonial armies. Genet’s script is accurate in showing the presence of soldiers from Mettray at key moments in the colonisation of Algeria, as well as in Mexico and Indochina. Demetz was an expert carceral entrepreneur who not only governed the prison but also the surrounding local population, enlisting them as – in effect – auxiliary prison guards to substitute for the absent perimenter wall. In Paris he garnered financial support from the governing classes in a similar way. By capitalising on the fear of crime to further his own institutional agenda, Demetz’s approach points forward to the ubiquitous work of today’s “(in)security professionals,” to use Didier Bigo’s suggestive formulation.

Featured image credit: Colonie de Mettray – La Revue du Dimanche, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire

The post A prison without walls? The Mettray reformatory appeared first on OUPblog.

Why solar and wind won’t make much difference to carbon dioxide emissions

We all like the convenience of electrical energy. It lights our home and offices, and drives motors that are needed in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems that keep us comfortable no matter what the temperature is outside. It’s essential for refrigeration that secures our food supply. In short, it makes modern life with all its comfort and conveniences possible.

However, most electricity is generated from burning fossil fuels such as coal or natural gas, leading to carbon dioxide emissions that could be responsible for climate change. In many circles there is a comforting belief that renewables such as solar and wind can replace fossil fuel electrical generation and leave us free to live as we do without carbon dioxide emissions. Fundamental physics and engineering considerations show that this is not so.

Power needs fluctuate with time of the day and, to a lesser extent, day of the week. In most places, peaks occur in the evening when people come home, start cooking, and turn on lights and entertainment systems. In Arizona in summer, the peaks are even more extreme due to the air conditioners all cutting in. There are also morning peaks, as people get up and turn on lights and hair dryers. Commercial and industrial use generally doesn’t change much throughout the day. The electrical utilities call this a baseload.

Household appliances by Photo-Mix. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Household appliances by Photo-Mix. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.The wicked capitalist-monopoly electric utilities have spoiled us; we’ve gotten used to the idea that we can turn on the lights at night and run an electrical appliance at any time we want. Since electrical energy cannot be stored in sufficient quantities, the utilities are always continuously matching supply and demand. Power generation systems that take a long time to ramp up or down, like nuclear or coal, are left running continuously and used to meet baseload demand. Fast response turbines using natural gas are typically used to match peaks.

Solar and wind present two problems. One is low power density; massive areas have to be devoted to power generation. The other, more serious problem is intermittency. If we only wanted to run electrical appliances when the wind is blowing or the sun is shining, fine, but don’t expect to use solar to turn on your light at night! So solar and wind cannot manage on their own; it’s always solar or wind AND something else. It’s hard to make it all work. They need either extensive storage or to be used in combination with gas turbines.

Batteries are also not a solution. In principle, I could run my house in Arizona on solar energy because almost every day is sunny. However, I would need a battery as big as the one in the Tesla S, about eight times the size of the Powerwall marketed for homes, and it would have to be replaced every three years. As Elon Musk said “Batteries suck.”

On a large scale, the only practical solution is pumped hydroelectric, where water is pumped uphill when there’s sunshine or wind and runs downhill to generate electricity when the wind stops blowing or the sun doesn’t shine. In many places, the extended sunny days are in the summer, the windy periods are in March and October, but the electrical energy is needed in the winter. In such cases, very large reservoirs are needed, comparable to the 250-square-mile lakes like Lake Mead and Lake Powell. Very few places meet these conditions.

So in practice, solar and wind have to be combined with gas turbines to deal with the drop in electricity generated when the sun goes down or the wind dies away. If the solar or wind displaces coal it results in a reduction in carbon dioxide emissions. However if solar or wind displaces nuclear that cannot be ramped up and down, more carbon dioxide is emitted because gas turbines have to be used when the sun isn’t shining and the wind stops blowing. Displacing the highly efficient combined cycle natural gas power plants, on average, results in no change in emissions. The gains from not running the fossil fuel plant when the renewable is available are offset by the losses from running the less efficient gas turbine on its own when the renewable is not available.

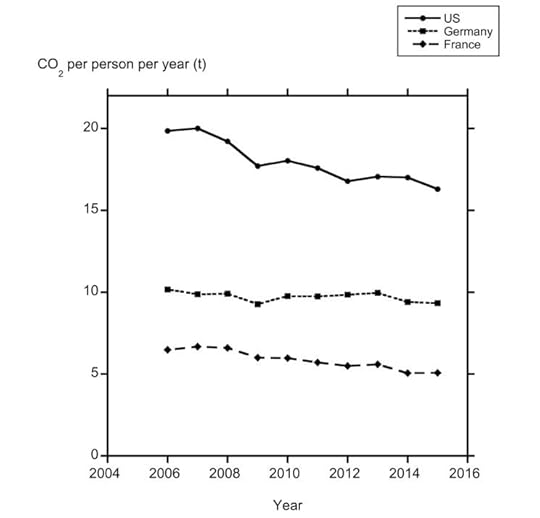

Carbon dioxide emitted in metric tonnes (t) per person per year. Data from Energy Information Agency for 2006-2013. The data for 2014 and 2015 was calculated from coal, oil, and gas consumption in the BP statistical review (2016), appropriately scaled to match the EIA data in 2006-2013.

Carbon dioxide emitted in metric tonnes (t) per person per year. Data from Energy Information Agency for 2006-2013. The data for 2014 and 2015 was calculated from coal, oil, and gas consumption in the BP statistical review (2016), appropriately scaled to match the EIA data in 2006-2013.One can easily verify this claim by looking to Germany, which has been in the forefront of adopting solar and wind in their Energiewende or energy transition. There is now as much solar and wind generating capacity in Germany as coal and natural gas. Has the increased reliance on renewables made any difference in Germany’s carbon dioxide emissions? Evidence suggests it hasn’t changed very much.

The careful reader may note that the French emit less carbon dioxide per person than the Germans and attribute it to the fact that the Germans are busy churning out BMWs and Bosch appliances, while the French lounge around on extended lunch breaks. However, the reality is more prosaic. The French baseload is almost completely nuclear with negligible carbon dioxide emissions.

If one really wants to reduce carbon dioxide emissions the best thing to do is substitute nuclear power for coal. However, that path is not available in the United States, where nuclear is a four letter word. Instead, we have achieved significant reductions in baseload carbon dioxide emissions over the last decade by substituting high-efficiency combined cycle natural gas for coal burning plants, a change made possible by the low cost of natural gas from fracking. The carbon dioxide emitted for each unit of electrical energy generated is approximately three to four times lower than in the corresponding coal-fired power plant, resulting from the higher thermal efficiency (50-60%) of combined cycle natural gas, compared to coal (30-35%) and the greater amount of energy from natural gas for a given quantity of carbon dioxide emitted.

To make a real difference one has to make a serious impact on the baseload. Intermittent renewables can’t do this, which is why they won’t significantly lower carbon dioxide emissions.

Featured image credit: Industry by Foto-Rabe. CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post Why solar and wind won’t make much difference to carbon dioxide emissions appeared first on OUPblog.

How Twitter enhances conventional practices of diplomacy

The attention given to each “unpresidential” tweet by US President Donald Trump illustrates the political power of Twitter. Policymakers and analysts continue to raise numerous concerns about the potential political fall-out of Trump’s prolific tweeting. Six months after the inauguration, such apprehensions have become amplified.

Take for instance Trump’s tweet in March 2017 that “North Korea is behaving very badly. They have been ‘playing’ the United States for years. China has done little to help!”, posted on the eve of US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s first official visit to China. The tweet complicated an already fractious relationship that Tillerson claimed was at “an inflection point.” Another example is Trump’s tweet on 24 January, 2017, regarding US national security and building the proposed US-Mexico border wall – “big day planned on NATIONAL SECURITY tomorrow. Among other things, we will build the wall!” This tweet signalled a steep decline in US-Mexico relations leading to Mexican President Enrique Peño Nieta’s cancellation of a planned meeting with Trump scheduled for the next week.

Such apprehension about the political effects of Twitter have often been linked to characterizations of the micro-blogging service itself as promoting overly negative, irrational, and unmoderated communication. There have even been calls to stop reading so much into Trump’s tweets. Yet we cannot deny that social media is increasingly used in diplomacy, and Twitter is especially rising in popularity as a foreign policy tool.

The power of Twitter emerges through how it challenges conventional diplomatic practices. Political leaders and policymakers frequently use Twitter alongside formal assemblies, social gatherings, and unofficial meetings, which have exemplified diplomacy over time. Two important aspects of Twitter stand out in facilitating this change: firstly, the public nature of tweets means an initial exchange between Twitter users can be shared with a much larger audience, leading to an incredible level of scrutiny. Secondly, the speed of this communication means there is much less time to digest and evaluate information, which can lead to a slow realization of change.

One noticeable outcome of the rapid and public nature of Twitter as a diplomatic tool is the insights it can provide into patterns of representations of both state identity and emotional expression, which are in turn central to the signalling of intentions between adversaries. How a state represents itself and recognizes others, often through boundaries of ‘us and them’, can be imbued with emotions that signal particular foreign policy positions.

We cannot deny that social media is increasingly used in diplomacy, and Twitter is especially rising in popularity as a foreign policy tool.

Consider a well-publicized acrimonious Twitter exchange between Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras and Turkish Prime Minister Davutoğlu in November 2015, during the EU-Turkey refugee summit. Tsipras publically “trolled” Davutoğlu over Turkey’s continued violation of Greek airspace and its apparent reluctance to find a solution to the refugee crisis in the Aegean Sea: “To Prime Minister Davutoğlu: Fortunately our pilots are not as mercurial as yours against the Russians #EUTurkey.” Davutoğlu tweeted back that “comments on pilots by @tsipras seem hardly in tune with the spirit of the day. Alexis: let us focus on our positive agenda.” Using representations of Turkey as unpredictable and volatile, Tsipras signaled continued Greek frustrations with Turkish actions. Davutoğlu, on the other hand, avoided escalating tensions further between the two states by framing his response within a positive affective disposition, calling for greater cooperation and understanding.

Another case of Twitter’s role in transformational diplomacy that stands out is Iran and US engagement via the microblogging platform in the lead up to the historic Iran and P5+1 nuclear deal in 2015, which saw sanctions against Iran lifted in exchange for a drawing down of its nuclear program.

Twitter played 2 key roles during this deal.

Firstly, Twitter became an alternative platform to official communication through which key stakeholders – US Secretary of State John Kerry, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, and Ayatollah Khamenei – could communicate and ‘talk honestly’ with one another, arguably helping to develop stronger trust between these counterparts. Consider the Iranian response to the open letter signed by 47 US Senate Republicans in April 2015, which claimed any executive agreement on the nuclear issue made between Obama and Khamenei could be swiftly revoked. Zarif tweeted directly to the instigator of the letter, US Senator Tom Cotton: “ICYMI my response. In English.” This tweet included a full page rejoinder emphasizing Iran’s good faith involvement in the nuclear negotiations. Zarif’s use of Twitter to reach out publically to Cotton allowed for a clear challenge to the representation of Iran as threatening and Irrational. In doing so, Iran was able to openly advocate for continued diplomatic efforts from all parties to the nuclear negotiations, signaling Iranian resolve to reach an acceptable deal.

Secondly, Twitter provided an alternative platform through which Iran could introduce slight shifts in representations of itself and the US. Key tropes of mutual respect proved to be a win-win; Iran as peaceful and progressive, and the negotiations were an instrumental opportunity in shifting the focus of Iranian communications to promoting positive aspects of its identity, rather than continually emphasizing negative representations of the US. This was a significant and public shift in the dynamics of recognition between these two states. These representations are key to understanding how, despite deep historical animosities on both sides, a more positive relationship was built that resulted in a successful nuclear deal. Unfortunately, Trump’s tweets about the ‘terrible’ nuclear deal demonstrate how easily, and quickly, good attempts at conflict resolution can be undermined. Representations that are deeply ingrained can also be easily deployed on social media, leading to greater potential for hostility.

Ultimately, diplomacy will continue to unfold through time-honored practices of engagement between states. However, dismissing the role of social media as a diplomatic engagement tool, particularly Twitter, means potential openings for transformative change might well pass before they can be acted upon.

Featured image credit: cell phone mobile by Free-Photos. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post How Twitter enhances conventional practices of diplomacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers