Oxford University Press's Blog, page 312

October 16, 2017

A Chopin-inspired reading list

I have always read “classics,” alongside contemporary titles, as an editor who desires to be informed by the past in shaping new publications; and a human who loves to read. We bring our personal and political lens to any work, and what makes reading and re-reading classics such an intellectually pleasurable occasion is to engage in the complicated questions brought up by context. Who is a reader today to talk back to a master writer? They are the only reader, they are the living interpreter of stories. Our breath and eyes are what literally bring a book alive.

I also think by critical analysis from contemporary lens, we gain the skepticism needed to read the hyped books of today with the same arched eyebrow–an awareness of the ways our world dictates so much of the form and content of what is published, what is praised, and what is lucky to be lasting as “literature” (quote unquote).

When I was offered the flattering invitation to pick an Oxford World Classic edition to read and discuss at the Bryant Park reading group this summer, I was drawn to titles that had informed my political consciousness as a young reader (a teen who always had nose in book, alternating between the canon and new releases, one day Kafka and Lorrie Moore the next). I considered The Jungle (the storyteller as activist!), The Way We Live Now (oh, look, a con man billionaire takes power?), and The House of Mirth (oh how I love that book; but jealously discovered Suzzy Roche got to Wharton first). Ultimately, I chose The Awakening, Kate Chopin’s novella about Edna Pontellier, a young mother in Lousiana whose sexual and spiritual transformations lead her to leave her husband, children, and ultimately her life.

I am the editor of a feminist magazine for mothers, MUTHA, where we share personal stories about birth and also among other things: sex, mental health, and (the taboo!) regret in the parenting role. So, frankly, the novella seemed “on brand.” Also, it’s a summertime story and it was August in NYC. It was hot and the water sounded lovely (Awakening joke).

“I have gotten into a habit of expressing myself. It doesn’t matter to me, and you may think me unwomanly if you like,” Edna tells her lover.

In this post, I want to offer an idiosyncratic paired reading list of living writers. Published in the period following Chopin’s “rediscovery” by the 60s-70s women’s movement, these books represent voices rocked by the waves left from Edna’s final swim.

First must be Toni Morrison’s Beloved, already often discussed as a companion or counterpoint, by the scholars who have delved much deeper into the silenced or caricatured Black women in Chopin’s work. Joyce Dyer writes, “it is time that we give Morrison her full due. It is time that we say, infullvoice—with pleasure and abundant thanks—how great has been her influence on our understanding of Chopin’s treatment of race.”

Brit Bennett, a powerful new Black voice, recently published her lauded debut novel The Mothers, which explores themes of sexuality, becoming (and not becoming) mothers, and regrets. ““Writing about ordinary black people is actually extraordinary,” as Bennett is quoted in the New York Times,“It’s absolutely its own form of advocacy.”

Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels are a fascinating read-alongside, not only because they are brilliant in limning the mother-writer conflict, but because like Edna, Lila disappears… and why (and to where, metaphorical or actual) has as many interpretations.

After Birth by Elisa Albert follows a feminist scholar, of the riot grrrl era (like me) who is now a new mother, through her post-partum depression and resulting drama, and is a scathing, brutal immersion into mother-anger. Imagine if Edna had tapped into her fury after she flees the “scenes of torture” of her friend’s childbirth and it might get you close. Elisa herself suggested this list (of radical women’s literature) in addition (and told me she once had a line from The Awakening written on her bedroom wall, “and the realization that she herself was nothing, nothing, nothing to the young man was a bitter affliction to her. But he too went the way of dreams…”).

Brokeback Mountain and Stonebutch Blues provide only the start of a list of queer experience stories that rocked their readership with their powerful sexual “awakenings” and “transgressions.” I found myself fascinated in particular by how the suicides (both implied) paralleled in Proulx and Chopin’s tragic figures, who found themselves propelled to act so far out of the bounds of their society that to be themselves, they sacrifice themselves.

The novel turned TV show I Love Dick by Chris Kraus is hilarious and sharp as an investigation of desire and feminism, and follow similarly the questions of whether Edna’s love for Robert is infatuation, lust, or a (warped) mirror of herself.

“When Kraus exploded privacy, what she demolished was a house beyond repair—sweeping away “privacy” in its present contradictory state so something that could be enjoyed, for the first time, equally and freely by both men and women, might take its place.”—Elizabeth Gumport

It’s been re-released by Emily Books, who publish “weird books by women,” and are awesome.

Unterzakhn is a graphic novel by Leela Corman, one of my favorite creators in the form, set in the early 20th century in New York City’s Lower East Side, and following two sisters who follow divergent paths as women/mothers (or not)/sexual beings in “face of the abyss and a condemnation of arbitrary, rules-based ethics systems,” as the book’s Comics Journal review illuminates. “If there’s a villain to be found… it’s hypocrisy.”

Featured image credit: “Blonde Girl by Pexels CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A Chopin-inspired reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

How Oscar Wilde’s life imitates his art

The idea that life imitates art is one of Oscar’s best yet most often misunderstood. It is central to his philosophy and to his own life. Take The Decay of Lying, for example, an essay in the form of a dialogue that he wrote in the late 1880s. What did he call the interlocutors? Why Cyril and Vyvyan, the names of his two young sons, of course. But the piece’s intellectual party really gets started when Wilde has his learned young gentlemen interview each other. Naturally, what is uppermost in their minds is the relationship between life and art. Just like their clever father, Cyril and Vyvyan are curious about how the real world and the imaginary world mirror each other.

Doublings such as these are usually a clue in Wilde that he is working through some element of autobiography. By the time he penned the essay, he was in his mid-30s, and on the verge of hitting it big. He also had a wife and family to support. He hadn’t yet written The Importance of Being Earnest or any of the mischievous society comedies that would make his name throughout the world. But he had taken a double first from Oxford, accessorized it with the Newdigate Prize for poetry, cut a dash as a London dandy and gained a reputation as a heartthrob in the United States where “Oscar Dear” became the name of one of the many songs immortalizing his charms. When he wasn’t flirting, he was lecturing Americans and Canadians about art and interior decoration, editing a feminist women’s magazine, reviewing books, and writing essays.

All the world seemed to be a stage to him, and life itself a kind of performance. And that became the subject of one of his most memorable pieces, The Decay of Lying.

Photograph of Oscar Wilde by Napoleon Sarony. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Oscar Wilde by Napoleon Sarony. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.“Life imitates art,” he argued, illustrating his lesson by pointing to children’s tendency to imitate what they read in books and stories. To prove his point, he turned to the phenomenon of “the silly boys who, after reading the adventures of Jack Sheppard or Dick Turpin”, 18th century criminals, wreak havoc on unsuspecting citizens “by leaping out on them in suburban lanes, with black masks and unloaded revolvers.” Today, you still hear a version of this idea when people talk about violent video games causing tweens to lash out.

Wilde’s goal wasn’t to save the children. His real target was adults – those who pretend they aren’t influenced by art or, worse, that art doesn’t matter. That’s obviously untrue. I’ve met enough adult Harry Potter readers to know. Because of what they’ve read, they look at Oxford subfusc with a reverence that black polyester hardly deserves. Wilde thought that adults were hypocrites. They were more influenced by art but better at hiding it than kids. Growing up involves lying low.

“What is interesting about people in good society,” he wrote, “is the mask that each one of them wears, not the reality that lies behind the mask. It is a humiliating confession, but we are all of us made out of the same stuff.” He didn’t think of himself as an exception to this rule. He told the poet Violet Fane that his essay was “meant to bewilder the masses” but was “of course serious.” The daily show in which we all star, he argued, is called being polite and it requires that adults wear a mask.

This may seem like old news now, but it was revolutionary to the Victorians. In an era when sociology was still in its infancy, psychology wasn’t yet a discipline, and theories of performativity were still a long way off, Wilde touched on a profound truth about human behaviour in social situations. The laws of etiquette governing polite society were, in fact, a mask. Tact was merely an elaborate art of impression management.

Wilde made his own life into a tragic, exquisite, grotesquely gorgeous work of art. That was his legacy to the 21st century. Nowadays Wilde’s queerness is being embraced with open arms. In 2017, he was among 50,000 gay men posthumously pardoned by the Ministry of Justice for sexual acts that are no longer illegal. Everywhere you turn these days, there seems to be another shrine to Oscar going up somewhere, whether it’s the Oscar Wilde Bar and Oscar Wilde Temple in New York, or the Irish hotels set to open in London and Edinburgh. Wilde’s works, once considered to have a corrupting influence, are now taught in schools around the globe. He has become gay history’s Christ figure. The relics of his martyrdom have become attractions, sites of pilgrimage.

On his 163rd birthday, he’s having the time of his life. The 21st century’s most curious gift of all is that his extraordinariness now passes for ordinary. It was a long time coming, but that’s one hell of a good birthday present.

Featured image credit: Photograph of Oscar Wilde mural by thierry ehrmann. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr .

The post How Oscar Wilde’s life imitates his art appeared first on OUPblog.

Perpetual peace

In the fall of 1697, the great powers of Europe signed a series of peace treaties at Rijswijk [Ryswick], near The Hague, which ended the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697), in which France was opposed by a great coalition of the Holy Roman Emperor, Britain, the Dutch Republic, and Spain. In its first article, the peace treaty between Britain and France, signed on 20 September 1697 (21 CTS 409), stated that, henceforth, there would be ‘universal and perpetual peace’ (‘pax … universalis perpetua’). The peace between the two powers held for less than five years. On 4 May 1702, the British formally declared war on France. Britain and its partners in the Grand Alliance (Treaty of The Hague, 7 September 1701, 24 CTS 11), the emperor and the Dutch Republic, did this in reaction to the acceptance of the Spanish succession for his grandson Philip of Anjou, by then Philip V of Spain (1683–1746), by Louis XIV (1638–1715) and to his subsequent actions to gain control over the Spanish Netherlands and to acquire trade privileges from Spain in its American colonies. After more than a decade of war, a new peace was made between France, its ally Spain, and the members of the Grand Alliance. Britain and some other states of the alliance made their peace with France at Utrecht on 11 April 1713. The peace treaty between Britain and France of that date, in its first article, reiterated the very same words ‘pax universalis perpetua’ from the Treaty of Rijswijk. (See 27 CTS 475 for the French-language version of this treaty, which contains the equivalent wording.)

It was standard practice for European powers in early modern peace treaties to designate the peace as definite, using this word ‘perpetual’ or a word to the same effect (‘duratura’, ‘eterna’, ‘à toujours’). This indicated that the peace treaty, and the state of peace which followed from it, would endure without limitation. In view of the fact that the peace often broke down after a few years, as in the case of the Peace of Rijswijk, it seems strange, even to be point of being naive or cynical, that the promise of perpetual peace was constantly rehearsed. But apart from publicly expressing an intention, which could be genuine or not but was generally popular, the indication that the peace was to be eternal had specific legal implications.

“Treaty of Nijmegen between Sweden and the Holy Roman Empire” byGustav Nilsonne. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Treaty of Nijmegen between Sweden and the Holy Roman Empire” byGustav Nilsonne. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The perpetual character of peace was what separated it most from truces. Since the Late Middle Ages, scholars as well as diplomats conceptually distinguished between three categories of treaties to suspend or end war: short-term armistices (indutiae), long-term truces (treugae), and peace. Both the civilians and canonists of the Late Middle Ages and the early writers on the law of nations from the 16th and 17th centuries debated the differences between truces, which would sometimes be made for many years, even decades, and peace. This was a complicated matter because long-term truces, such as the ones made between the kings of England and France from the late 15th century or the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609–1621) between the Dutch Republic and Spain, would assume almost all the characteristics of peace treaties, but for their duration. Long-term truces might include stipulations which completely suspended the state of war by lifting and undoing wartime measures and completely restoring peaceful relations between the belligerents as they had existed before the war. Although there was much debate about the different legal implications of truce and peace, there was agreement that a peace ended the state of war, while a truce only suspended it. Whereas scholars did not agree on the question whether a new declaration of war was needed at the end of a truce before hostilities were resumed, there was consensus that the former belligerents had a right to resume the war after the truce without defaulting on their treaty obligations.

It is here where the real legal meaning of perpetual peace comes to the fore. Peace treaties ended the state of war between belligerents for all time. This meant, as Baldus de Ubaldis (1327–1400) had already indicated, that the conflicts which had caused the war and over which the war had been fought had found a final settlement in the treaty. This accorded more or less with peace treaty practice from the 15th to the 18th century. In peace treaties, outstanding conflicts between the parties were either settled through legally binding compromises, or a commitment was made by the signatories not to resort to force again about certain disputes which were left unsettled.

The final character of the settlement, or the perpetuity of the commitment not to resort to force over them, implied that treaty parties agreed that the peace treaty exhausted their right to resort to force or war in the future and for perpetuity for the conflicts that were covered by the peace treaty. It would take Samuel Pufendorf (1632–1694) to state this directly, but it could already be inferred e contrario from Baldus’s statement that the outbreak of a new war did not violate a peace treaty if it was fought for a cause, a conflict, which was not covered by that peace treaty. It was also standard practice. All over the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Ages, princes and republics were careful to argue, when they went to war with a power with which they had signed a peace treaty, either that the opponent had violated the peace treaty or that they were resorting to war for a new cause. When they declared war on France on 8 May 1702, the Estates General of the Dutch Republic explained in what manners France had broken its obligations under the Peace of Rijswijk, whereas Britain in its declaration focused on the direct causes of the war that had arisen from events occurring after 1697. In this, both of them were following standard practice.

Featured Image Credit: “Allegorie op de Vrede van Rijswijk, 1697 Rijksmuseum” by Johannes Voorhout. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Perpetual peace appeared first on OUPblog.

October 15, 2017

Disaster or disturbance: environmental science of natural extremes

Hurricane Harvey. Hurricane Maria. Natural disasters that will go down in the history of certain communities as ‘the big one’. Hurricanes and floods are disasters for human communities because of the loss of life and property and the damage to infrastructure. When I consider the recent hurricanes as an environmental scientist, however, I do not see them just as disasters. My perspective is informed by two fundamental aspects of environmental science: large hurricanes and other disturbances are a natural part of the environment, and our alterations of the natural environment may exacerbate the impacts of disasters on human communities.

In photographs taken since Maria, the forests of Puerto Rico are nearly unrecognizable. I remember a densely vegetated, intensely green forest from my visits there. Woody vines snake up the trunks of trees and twine through the forest canopy, where branches look furry in their coats of epiphytes and bromeliads. Malachite-green mosses cover fallen logs and emerald-green algae grow over the cobbles in the stream. Now the forests are the brown of stripped and scarified wood and fallen leaves. The one-two punch of Irma and Maria, and the shearing and pummeling of intense winds, shredded the greenery, leaving a tangle of downed wood and standing, splintered trunks. It looks like a disaster.

But, just as one woman’s trash is another woman’s treasure, this is an opportunity for many organisms. People who live in my part of the world – the dry interior of the western United States – have grown to understand that plants such as ponderosa pine only thrive in a landscape with periodic wildfires. The seeds of some plants can only sprout and grow following fire. Other plants require abundant sunlight to grow, which reaches the forest floor only after a wildfire reduces the shading from larger trees. Bark beetles move into a burned forest to burrow into the standing dead trees and woodpeckers follow the bark beetles. Even as new trees grow over the next few decades, cavity-nesting birds benefit from the standing dead trees left by the fire. Even extensive fires are capricious, leaving unburned patches scattered among the blackened, smoke-scented snags, and enhancing the diversity of plant and animal species and the age structure of the forest.

Sierra Palm forest, Puerto Rico, before the storm. Ellen Wohl, used with permission.

Sierra Palm forest, Puerto Rico, before the storm. Ellen Wohl, used with permission.When Hurricane Hugo roared through eastern Puerto Rico in 1989, environmental scientists who had studied the region for years watched in awe as the forest changed dramatically in a few days, and then rebounded within months. Stream ecologists found that formerly shaded streams experienced a population boom of algae as sunlight reached the stream bed and decomposing leaves provided critical nutrients. Aquatic insects that feed on algae became super-abundant, as did the freshwater shrimp that feed on algae and on leaves partly decomposed by microbes. Branches and palm fronds piled up in debris dams more than three feet high across small streams, increasing space for microbes, insects, fish, and shrimp to live in. Within six months, the debris dams gradually decayed and dispersed, vegetation regrew and once more shaded the streams, and the types of organisms in the streams resembled those present prior to the hurricane. This resilience is why ecologists refer to hurricanes or fires as disturbances, rather than disasters. Hurricanes kill some organisms and alter the ecosystem, but they do not destroy everything.

Forest ecologists watching trees spurt up to claim their place in the sun found that plant regrowth after Hugo was two to three times as fast as in portions of the forest not disturbed by the hurricane. Three years after Hugo, the forest had largely recovered the amount of vegetation it had previously, although the age and types of plants changed. One organism’s disaster is another’s disturbance-opportunity.

Like wildfires in dryland forests or floods in rivers, hurricanes and other natural disturbances can help to maintain ecosystem health by creating opportunities for pioneer species that increase biodiversity and for younger plants that increase the age and diversity of the forest. The rapid regrowth of plants and recolonization by animals following hurricanes illustrates how natural communities can be resilient to disturbance and even depend on periodic disturbance to maintain ecosystem health. This is an understanding of natural disasters that comes to us from the work of environmental scientists.

Puerto Rico after the storm. Omar Gutiérrez del Arroyo Santiago, used with permission.

Puerto Rico after the storm. Omar Gutiérrez del Arroyo Santiago, used with permission.Another understanding comes from environmental scientists who examine how human communities influence and respond to natural disasters. Environmental geologists illuminate the ways in which levees and river channelization exacerbate flood damages downstream by reducing the ability of water to spread onto floodplains, or roads increase landsliding during hurricanes by concentrating downslope movement of water. Environmental geologists also guide planners and citizens toward patterns of land use that may reduce death and economic damages during natural disasters. Ecologists and conservation biologists explain how river channelization, roads, removal of riverside vegetation, and urbanization limit the resilience of natural communities by reducing the abundance and diversity of new habitat following a disturbance and by limiting the migration pathways available to plants and animals following disturbance. Social scientists take note of the manner in which loss of life and property can bring members of a human community emotionally closer as they realize their interdependence and work to save each other. This facet of environmental science situates us, and our actions, in a context of dynamic natural systems that periodically experience extremes of climate and geology.

Disaster comes from ‘dis’ and ‘astrum’, as in star, and an older meaning for the word is ‘a baleful aspect of a planet or star’. Does the fault of a natural disaster lie in us or in our stars? A little of both. Geological records of natural disasters indicate that these disturbances have a history as long as that of living organisms on Earth. Our preparedness for natural disasters and our resilience to them depend on our understanding of these disturbances on our rapidly-changing planet. If we can continue to develop this understanding, we may be able to lessen the negative impact of disasters and in turn see a way to a brighter future.

Featured Image credit: Puerto Rico before the storm. Ellen Wohl, used with permission.

The post Disaster or disturbance: environmental science of natural extremes appeared first on OUPblog.

The point of depression

There has been a great deal of speculation about the evolutionary significance and origins of depression. What selective advantage does it confer?

Does it allow the patient to concentrate on complex and important problems? Is it a type of pain that, like physical pain, causes us to pull back from danger? Is it a type of behavioral quarantine, causing us to hole up in a safe place while dangers stalk around outside? Perhaps it reduces our libido and our appetite for social interaction in order to stop us getting or giving infectious disease? Is it a simple signal that we need help? Is it a sort of threat to others in our community that, unless they do something to help us, they will have a liability in their midst that could endanger them? Is it a sort of fuse, switching us off and causing us to back down when we are outgunned – so saving us from risky and costly conflicts with our peers?

These suggestions, and the many others in the literature, may seem insulting and insensitive. Isn’t it like asking the point of a disabling road traffic accident?

Well, possibly. But much disease is the result of the malignant transformation or manifestation of a physiological response that is usually useful. Auto-immune illness and allergy, for instance, are damaging consequences of facilities without which we would be dead. So the desire to squeeze depression into the neo-Darwinian paradigm is not necessarily misconceived. What is misconceived, I suggest, is the sheer fancifulness of many of these suggested explanations. Their authors are too clever, ingenious, and imaginative.

Image Credit: “Outlook and Contemplate” by PublicCo. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image Credit: “Outlook and Contemplate” by PublicCo. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Here’s an alternative suggestion, which at least has the advantage of not being so smart.

We need to start by deciding what depression really is. It is, I suggest, an ontological disorder. The main pathology in depression is the erosion or truncation of the Self. Depression robs us of the characteristics that make us us. ‘She’s not herself’, we’ll shrewdly say. The job of a psychiatrist is to ‘put the patient back in their right mind’. Depression makes us sit all day in our bedrooms, facing the wall: cutting ourselves off from all the relationships which define us and make our lives our lives. And if the depression isn’t treated, the threat to the Self can become desperately dangerous. We might annihilate the Self with razor blades or by jumping off a bridge.

Usually, though, the danger isn’t mortal. Most manifestations of depression, for most of us, most of the time, are premonitory signs. They tell us that the Self is vulnerable: that it needs some urgent TLC – or else.

Perhaps it doesn’t need to be stated (it’s really tautological), but of course a sense of Self is vital to our biological survival (which is Darwin’s main interest). It’s my sense of Self that makes me compete for a mate; which makes me look for my next meal; which makes me avoid harming myself.

So: most of the time, depression is acting to preserve the self. It doesn’t just cause us to run away from nasty stressors, as some of the other theories suggest. It acts too as a health education program, teaching us about effective therapies. Once you’ve had a small dose of depression, you recognize the symptoms next time, and reach more quickly for the remedy (whether it’s pills, a holiday, a walk in the sunshine, or a massive dose of friendship).

Depression, then, is a thief of Self which has been cunningly recruited by evolution to frustrate its own burglarious project.

Featured Image Credit: “Man Mourning” by HolgersFotografie. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post The point of depression appeared first on OUPblog.

Lionfish: the perfect invader

The invasion of the Caribbean by Indo-Pacific lionfishes happened seemingly overnight. In the early 2000s, the first papers were published about lionfish sightings in places like Florida, half a world away from their native range—by 2010, they were almost everywhere in the Caribbean, and even now, they continue to expand the edges of their invasive Atlantic range. The naïve fish on Caribbean reefs, where lionfish did not previously occur, were decimated by this voracious predator. Populations plummeted and some fishes got dangerously scarce.

When these alien fish appeared, very little was known about their ecology or evolutionary history. Christie Wilcox, then a PhD student at the University of Hawaii, wanted to work on the genetics of the invasive lionfish Pterois volitans. Maybe by looking at their genes, Christie might help managers understand these beautiful, mysterious fish. Genetic studies could reveal the source population to help understand why the invasive fishes spread so fast, grow so quickly, and become so large.

She never did find the source population for the invasive lionfishes. Instead, her work uncovered something bigger: the invasive species P. volitans was a hybrid.

There is an old saying that the big scientific discoveries aren’t “Eureka!” moments but rather “That’s funny…” moments. It certainly fits in our case; we didn’t set out to find hybrid lionfishes dominating the Atlantic invasion. Rather, they found us, appearing suddenly and unexpectedly in our data.

At first, we had only managed to get a few lionfish specimens. We hoped to create a phylogenetic tree of the lionfish subfamily Pteroinae, but to do that, we needed to find variable DNA sequences that could separate all of the different species, including close relatives like Pterois volitans and Pterois miles (both of which have been detected in the invasive range). We started testing genetic markers thanks to generous DNA donations from David Wilson Freshwater from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. While it was fairly straightforward to find mitochondrial DNA markers that were different between the species, we struggled to find any difference in the nuclear genome. We tried dozens of genetic loci, but couldn’t find any consistent differences between those two species.

Christie holding a juvenile lionfish from the invasive range. Photo Credit: Christie Wilcox.

Christie holding a juvenile lionfish from the invasive range. Photo Credit: Christie Wilcox.Then, a few tissue specimens from the Pacific native Pterois lunulata, arrived from the Biodiversity Research Center, Academica Sinica in Taiwan. When we sequenced the different gene regions for those samples, a strange pattern emerged. For mitochondrial markers, the P. lunulata samples looked like the invasive P. volitans, but for several of the nuclear markers, they were clearly distinct. When we constructed phylogenetic trees, the few P. volitans samples we’d sequenced jumped from P. miles to P. lunulata depending on the genetic locus.

Surprised by these results, we sought out more samples. Lucky for us, Hiroyuki Motomura at the Kagoshima University Museum in Japan, and Mizuki Matsunuma, now at Kochi University, were also looking into the same lionfish group. They had collected hundreds of lionfishes from a range of species, discovering several new species in the process. It was the treasure trove of genetic and morphological data that we needed to understand why the specimens seemed so strange. Collaborating with them, we sequenced one mitochondrial locus (a portion of the cytochrome oxidase gene) and two nuclear introns for over 200 lionfishes. That’s when it became clear: P. volitans consistently shared DNA with two other species of lionfishes: its presumed sister species P. miles in the Indian Ocean, and a lineage comprised of two Pacific species P. lunulata and P. russellii.

The finding that closely related species hybridize once in awhile is not remarkable. However those two lineages have been separated for several million years, based on the mitochondrial molecular clock—more than long enough to be considered separate species. It was as if the entire species of P. volitans was made from the mixing of these other species. We found even more evidence for hybridization when we looked at the animals themselves. Those that were intermediate at the genetic level also had intermediate morphological characteristics like fin ray numbers. The correlation of genotype and phenotype strongly indicated hybridization.

Hybridization was once considered rare in the marine realm, but over time, we’ve seen many examples of hybridization between marine fishes. Species split at known barriers—like P. miles and P. lunulata/russellii, which are found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, respectively—are particularly prone to such interspecies mingling. But so far, most hybrids are restricted to a thin range along the Indian/Pacific boundary. The hybrid P. volitans has a vast range across the Western Pacific. Given the success of P. volitans in its native range, these lionfishes may be getting a benefit from their mixed genes, a phenomenon called heterosis or hybrid vigor. Could the Atlantic invader be a superfish?

Lionfish Pterois miles from the Red Sea, one of the two species that make up the hybrid invader in the Atlantic. Photo Credit: Tane Sinclair-Taylor. Used with permission.

Lionfish Pterois miles from the Red Sea, one of the two species that make up the hybrid invader in the Atlantic. Photo Credit: Tane Sinclair-Taylor. Used with permission.Armed with this new information from the native range, we took a fresh look at the invasive Atlantic range. Nearly all of the invasive fishes we examined from the coast of North Carolina were hybrids.

If our findings are correct, then they suggest that to really understand the invasive lionfish, we can’t just look at similar lionfishes. We have to look at the biology and ecology of the lionfishes that served as the source of the invasive population—a source which remains a mystery.

Our findings also might explain why the lionfishes in the invaded range are doing so well. The invader is a fast growing, highly fecund, generalist predator armed with venomous spines, placed into a habitat free of its normal parasites, predators, and competitors. The combination of naïve prey in the invaded range, and hybrid vigor, may have produced the perfect invasion, a terrifying precedent in the annals of invasion biology.

Featured image by bachstroem. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Lionfish: the perfect invader appeared first on OUPblog.

October 14, 2017

Understanding physician-assisted death [excerpt]

When it comes to end-of-life treatment, patients currently have a few different options available to them. One option, refusal of treatment, is when a decisionally capable patient is put in the driver’s seat with respect to medical treatment under the doctrine of informed consent. Another option is pain management, where palliative medicine is administered to entirely eliminate, or reduce pain to a level that the patient finds tolerable. There is also terminal sedation, which is the practice of maintaining a patient in a state of deep and continuous unconsciousness until the point of death.

A fourth option, if the patient is in a jurisdiction that has legalized it, is physician-assisted death. In the following shortened excerpt from Physician-Assisted Death:What Everyone Needs to Know, L.W. Sumner helps us understand exactly what physician-assisted death (PAD) is.

What is physician-assisted death?

The end-of-life treatment options we have surveyed so far—refusal of life-sustaining treatment, aggressive pain management, and terminal sedation—are all relatively uncontroversial from an ethical standpoint (with the exception of some issues we have noted along the way). They are also legal in most jurisdictions, including the United States. However, our main topic is another end-of-life option that is neither ethically uncontroversial nor legal (except in a few places). So we need to be sure we understand exactly what physician-assisted death (PAD) is.

As we have seen, there are many ways in which physicians (and other health care providers) may assist their patients through the dying process. Furthermore, as we have also seen, at least some of these ways may have the effect of hastening the patient’s death. However, PAD refers exclusively to one particular way in which a doctor may help to hasten a patient’s death: by providing the patient with medication (typically a barbiturate) at a dose level that is intended to cause death and that does in fact cause death. There are two ways in which this may occur. In physician-assisted suicide the doctor prescribes the medication for the patient, who then self- administers it orally. In physician-administered euthanasia the doctor administers the medication to the patient intravenously or by means of an injection. The difference between these two forms of PAD is strictly one of agency: who ends up actually administering the medication to the patient. In either case the administration of the medication is the immediate, or proximate, cause of the patient’s death.

As the phrase suggests, PAD (in either form) is something done by a physician: it is physician-assisted death. So, while it is possible for others (family, friends, etc.) to assist someone’s death, even by providing or administering a lethal dose of medication, we are confining ourselves here to cases in which this is done by a doctor (or by another health care provider, such as a nurse, under the direction of a doctor). Unlike patient refusal of life-sustaining treatment, PAD involves administering treatment rather than withholding or withdrawing it. To put it differently, it is something that patients must request, not something they must refuse. In terms of a common (though misleading) distinction, PAD is therefore necessarily “active” (since it requires the administration of a lethal medication) rather than “passive.” The phrase “active euthanasia” is therefore redundant, and “passive euthanasia” is a contradiction.

“Unlike patient refusal of life-sustaining treatment, PAD involves administering treatment rather than withholding or withdrawing it.”

The best way to bring out the further features of PAD is to compare it to the other end-of-life treatment measures considered earlier. There are two important similarities among all of these measures. First, they all have at least the potential to hasten the patient’s death. This is obviously true for PAD, in which the administration of the medication is the cause of death. But it is also true for refusal of life-sustaining treatment (on the assumption that the treatment refused would have extended the patient’s life for however short a period) and for terminal sedation (at least on the assumption that the patient refuses artificial feeding and hydration while sedated) and may potentially be true for pain management (though, as we saw earlier, this is a matter of some controversy).

The second similarity is that all of these treatment options can be either voluntary or nonvoluntary. A treatment option is voluntary when it is requested (or, in the case of discontinuation of treatment, refused) by a patient who is decisionally capable at the time at which the treatment is to be administered. But they can be nonvoluntary as well: in the case of a currently decisionally incapable patient life-sustaining treatment can be refused, or higher doses of opioids or sedatives can be requested, by substitute decision makers. The same can be true for PAD in the case of a patient currently incapacitated by conditions such as severe dementia or irreversible unconsciousness.

Voluntary end-of-life measures that have the effect of hastening death are easier to defend than nonvoluntary ones since in these cases the factor of patient autonomy is fully in play: the patient himself or herself is making an informed request (or refusal) at the time at which treatment will be initiated (or discontinued). The situation becomes much more complicated when the patient is not currently capable of making such a request and even more complicated for patients who have never had this capacity.

There are equally important differences between PAD and the other end-of-life measures. One of these has to do with cause of death. In the case of PAD it is clear that the administration of the lethal medication is the immediate, or proximate, cause of death. This might also be said to be true for pain management or terminal sedation, if they do sometimes have the effect of shortening life. But in the case of treatment refusal it is at least arguable that the cause of death is the patient’s illness (though this is less arguable when the treatment refused is artificial ventilation or nutrition and hydration). The other difference is a matter of intention. When a patient refuses further treatment, it may often be misleading, or just downright wrong, to say that he or she is thereby intending to hasten death (though the same exceptions might apply). We have also seen that high doses of opioids or sedatives are normally administered in order to minimize or eliminate patient suffering; if they ever also hasten the patient’s death, then this is regarded as a further unintended effect. However, in the case of PAD the intent of the administration of the medication is precisely to cause death—or, to put it another way, to end the patient’s suffering by bringing about death.

So PAD appears to differ from other end-of-life treatment options in terms of both causation and intention. It is these differences that are often thought to define an ethical “bright line” dividing PAD from these other, less controversial measures.

Featured image credit: “Love Heartbeat” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Understanding physician-assisted death [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Nine things you didn’t know about love and marriage in Byzantium

The Byzantine civilization has long been regarded by many as one big curiosity. Often associated with treachery and superstition, their traditions and contributions to the ancient world are often overlooked. Referencing A Cabinet of Byzantine Curiosities, we’ve pulled together nine lesser known facts about love and marriage in Byzantium.

Beauty pageants

The imperial court would often organize bride shows, basically beauty pageants, to find a wife for the heir to the throne, who would give the winner a golden apple. The most famous show was for the Byzantine Emperor Theophilos. He was allegedly smitten by the beautiful but sharp-tongued Kasia, and tested her by saying, “the worst evil came into the world through woman,” referring to the temptation of Eve. To this she responded, “And so did the best of the best,” referring to the promise of salvation, Jesus, born of Mary. Theophilos didn’t like the riposte and chose Theodora instead, giving her the golden apple.

Rules and restrictions

By the eleventh century, the Church had put in place a complicated set of restrictions on marriage. Among other rules, marriage was forbidden between two persons who were connected by up to seven degrees of genealogical relation, counting inclusively. Additional rules prohibited marriage between persons related via spiritual kinship, especially that established by baptism, or by the prior marriage of mutual relatives. It was a complicated enough business that special treatises were required to sort it all out.

A Cinderella story

Court officials touring the provinces in search of suitable brides for the imperial prince were apparently given a painting of what a perfect or ideal match should look like, and they tried to match it to the candidates they met. They also carried an imperial shoe of the right length for the ideal bride and tested it on their feet.

Men and divorce

By law, a man could ask for divorce if his wife had questioned his masculine honor—say, through infidelity or immoral behavior; caused him bodily harm by attempts on his life through magic or physical violence, or jeopardized his attempts to procreate. He could also demand divorce if his wife was incapable of fulfilling her conjugal duties due to an incurable illness— say, madness or leprosy. Madness was sometimes distinguished from demonic possession, which did not constitute grounds for divorce.

Women and divorce

Women could demand divorce if the marriage threatened their chastity— say, through incitement to prostitution or accusations of infidelity; or their bodily integrity by attempts on their life through magic or physical violence; or if the man could not fulfill his duties because of an illness (again, madness or leprosy), was implicated in serious crimes, or was sexually impotent for more than three years or absent for more than five. A woman could also ask for divorce if her husband was convinced that she was cheating on him and persisted in this belief even after discovering that he was wrong.

Image Credit: “Emperor Theophilos Chronicle of John Skylitzes.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: “Emperor Theophilos Chronicle of John Skylitzes.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Fertility

Ecclesiastical writer and priest Anastasios of Sinai used soil as an analogy to explain why some rich people desire to have children but cannot, whereas many poor people can easily have many children: soil that has received too much water is not fertile, whereas soil that has been watered moderately is.

Chastity

There was a statue of Aphrodite near the hospital of Theophilos in Constantinople which was said to have the following power: if a woman was a virgin or a chaste wife, it would allow her to pass unmolested, but if she had been naughty or adulterous, it would cause her to lift up her dress and expose the shame of her privates for all to see. It was, accordingly, used to perform chastity tests. But the sister-in- law of the emperor Justin II had the statue destroyed because it did this to her when she was passing by on other business.

Dream interpretations

According to a book of dream-prediction attributed to Ahmet, if you dream that you have relations with

a classy escort, it means that you will become rich

a nun, it means that grief is in store for you

a common whore, your wealth will grow, but by unjust means

a beautiful woman, you will find joy and wealth within a year

an old woman, you will obtain power from an ancient source

Featured image credit: “Marriage Ring with Scenes from the Life of Christ” provided by the Walters Art Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Nine things you didn’t know about love and marriage in Byzantium appeared first on OUPblog.

When our tribes become bullies

I was recently reintroduced to the word “tribe” when my son-in-law described my grandson’s reaction to trying a new sport. Since the age of four, Sam, has been encouraged by his parents to participate in athletics, but his interest in anything to do with rolling or catching a ball is nil. He was so disinterested that at age five, during one of his soccer games, he raised his hand, and asked, “Who likes mac and cheese?”

The entire team stopped and raised their hands. By the age of 8, Sam was “baked” with regard to sports. That is, until, his friend introduced him to the World Wrestling Association. He was hooked.

After watching him morph into a “wrestling maniac”, his parents signed Sam up for wrestling classes. He was like a duck taking to water, or puppy discovering snow for the first time. My grandson was in heaven, describing the thrill he felt when he “pinned” his opponents. My son-in-law proudly reported, “Sam has found his tribe!”

This was a new definition of the word “tribe” for me. I thought that it pertained to folks connected by bloodline; kindred relations. So I looked up its definition and sure enough one of them in the Meriam-Webster Dictionary describes it as “a group of people who have the same job or interest.” (Merriam-Webster, unabridged, online, 9/18/2017)

My son-in-law used the word, “tribe” to describe his son’s positive connection with kids who share the same interest. It has given him a feeling of accomplishment and a sense of belonging; he’s discovered a “safe” place beyond his family of birth where he can be himself.

But recently I’ve also heard the term tribe used pejoratively, by political pundits to describe groups of people with less than noble political agendas. These factions, not related through bloodline, use intimidation and force against others they believe to be inferior. In other words, their form of tribal behavior equals bullying.

Tribalism’s slide into bullying has become seemingly pervasive. We’ve all seen how it contaminates schools, sports, and work. In all of these collective institutions there is a drive to form tribes—often motivated by a desire for constructive kinship, but just as frequently for purposes of control, and exclusion.

The change begins at home with parents who understand that hate causes violence. They hold the key to laying the ground-work when it comes to their children’s early learning.

Non-kinship tribal members bond through their passion and shared beliefs. Euphoric-visceral responses when evincing certain behaviors often prompts us to desire more of the same and are frequently encouraged within tribal settings. Tribes have the power to further enlighten or oppress our humanity.

In Sam’s case, his tribal affiliation is positive because he is building new skills and developing good sportsmanship. Conversely, people that engage in tribal bullying, are strangled by their biases and fears.

Because this behavior is so firmly rooted in how humans relate to one another, it is certain to continue unless we become vigilant about identifying it and calling it out. It won’t end when public announcements declare, “Just say no to bullying.” It will stop when people recognize and openly challenge it through education and discussion. And unless persons with serious personality disorders abound, most individuals can learn compassion when they experience kindness firsthand from someone they have previously held in contempt.

The change begins at home with parents who understand that hate causes violence. They hold the key to laying the ground-work when it comes to their children’s early learning. Their enlightened behavior provides the essential framework for their kids’ later behavior.

Our schools must develop more comprehensive and nuanced responses to bullying. School administrators need to write and train their teachers on specific, not general, guidelines to recognize and manage school bullying. These practices must be consistently maintained and not forgotten due to funding or time constraints. And administers should focus on strength-based management.

Workplaces must value their employees as much as their customers, lead through example, and implement zero tolerance for on-the-job bullying. Workers should not need to fear push-back when they file bullying complaints through their human resources departments. These simple business practices go a long way in retaining staff, saving money and elevating workplace behavior.

And recently, political gamesmanship in our government appears to have upstaged productive civil discourse and compromise. Many politicians have taken a “guerrilla warfare” approach to dealing with the opposition. This form of bullying has had a disturbing trickle-down effect with the public.

As individuals we can make a difference when it comes to challenging bad behavior. And it’s our responsibility to recognize and stand up to any type of bullying. Bullying thrives in the dark when people turn a blind eye. It takes courage to defeat the “bully monster” when we are the only ones standing. But we know, that when it’s all said done, monsters don’t live in the light.

A friend of mine often repeats: “change takes a very long time.” And that’s probably true, but I also think these times are ripe for change.

Featured image credit: gulls fun photo background by pixel2013. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post When our tribes become bullies appeared first on OUPblog.

October 13, 2017

How does circadian rhythm affect our lives?

The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to American biologists Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael W. Young for their discoveries of the molecular mechanisms that control circadian rhythm in organisms. Their work began in the 1980s with the study of fruit flies, from which they were able to identify the proteins that controlled the flies’ daily biological rhythms. Though flies and humans are vastly different, based on the Nobel laureates’ findings, it is now determined that the circadian rhythm of multi-cellular organisms function in similar ways. Circadian rhythm contains organisms’ “biological clocks” and is the self-sustaining system that provides organization to biological processes. It allows for animal, plant, and human life to prosper.

We’ve gathered these facts about circadian rhythm, its importance to daily life, and the impact that disrupted rhythms have on humans.

Circadian comes from the Latin words meaning “about” (circa) and “one day” (diem), and the circadian rhythm maintains the cyclic variations that organisms undergo over twenty-four- to twenty-five-hour periods called tau. External cues called zeitgebers “entrain” the circadian system to the twenty-four hour solar day, and sunlight (and lack thereof) is the main zeitgeber for humans. The ebb and flow of hormones is synchronized for use during daylight hours.

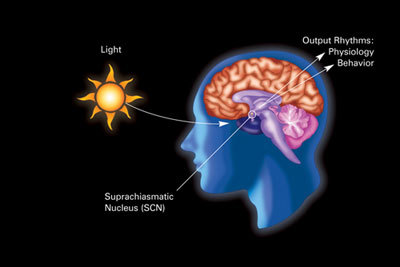

Animal research such as that of the Nobel laureates’ determined that the molecular machinery behind the circadian rhythm exists in each cell of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus, a small group of neurons in the brain. Studies in which SCN maintained in cell cultures still generated a twenty-four hour rhythm provide further evidence for this fact, though outside light is necessary for the resetting of the rhythm to keep the organism in sync with the solar day.

Exposure to artificial lighting and light pollution during night hours – time meant to recuperate and rest before the daytime cycle starts again – can greatly affect the health of humans. This is especially impactful on the elderly, whose weaker circadian rhythms can become confused as a result of light pollution. In 2009, the American Medical Association officially identified light pollution as a health risk.

Diagram illustrating the influence of dark-light rhythms on circadian rhythms and related physiology and behavior. National Institute of General Medical Sciences, 2008. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Diagram illustrating the influence of dark-light rhythms on circadian rhythms and related physiology and behavior. National Institute of General Medical Sciences, 2008. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Circadian rhythm is one of two processes that regulate the timing of sleep and wake. It interacts with the homeostatic sleep system to promote wake during the “biological day” and promote sleep during the “biological night.” The homeostatic drive to sleep, Process S, increases with time spent awake, while the circadian drive, Process C, increases or decreases depending on the time of day.

Because circadian rhythm affects the sleep cycle, studying the circadian rhythm of individuals can determine if someone is a morning or a night person, especially in children. The assessment of a person’s circadian rhythm and sleep cycle is called a chronotype, which is conventionally broken down into three groups: morning people or “larks,” evening people or “owls,” and those who fall in between, “neither.”

Sleep disorders such as the delayed sleep phase disorder (DSPD) and advanced sleep phase disorder (ASPD) are associated with circadian rhythms timed too late and too early. Bright light therapy and melatonin administration are two treatments for these disorders.

Jet lag is another frequently-experienced circadian rhythm disorder. The abrupt transport from one time zone to another presents a new set of external time cues to the individual, causing a feeling of “shifted time” and can lead to insomnia, poor mood, and loss of appetite. Approximately two-thirds to three-quarters of travelers experience jet lag after trans-meridian travel.

Featured image credit: “night and day” by qimono. CC0 via Pixabay .

The post How does circadian rhythm affect our lives? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers