Oxford University Press's Blog, page 314

October 10, 2017

World Mental Health Day 2017: History of the treatment of mental illness

The tenth of October marks World Mental Health Day. Organized by the World Health Organization, the day works toward “raising awareness of mental health issues around the world and mobilizing efforts in support of mental health.” Mental health has been a concern for thousands of years, but different cultures have treated mental illnesses very differently throughout time. This timeline gives a broad overview of some of the most prominent ways in Western history people have approached trying to care for and cure mental illness.

Featured image credit: Jason-Blackeye-303521 by Jason Blackeye. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post World Mental Health Day 2017: History of the treatment of mental illness appeared first on OUPblog.

October 9, 2017

A short walk per day: a look at the importance of self-care

“What have you been doing that has been especially important over the past several years?” In the following video and shortened excerpt from Night Call, Robert J. Wicks explains how this question helped him realize the importance of striking a balance between compassion for others and self-care.

I received a call from an old friend from New York City. I was the best man at his wedding and when I relocated, he moved, and slowly we lost touch. It had been more than ten years since we had a meaningful conversation. I was thrilled to hear his voice and recognized it in an instant. You could tell that he was also pleased that we were able to reconnect. He opened the conversation by asking me how I was doing and what I was up to at work. In response, I enthusiastically shared all that I was involved in— not only as a university professor and author but especially in my consultancy and presentations to helping and healing professionals on resilience. I told him this is a work I truly love because it puts me in touch with leaders and novices in such areas as psychology, psychiatry, social work, counseling, ministry, education, medicine, and nursing. I loved it, but the intensity of work with helpers under great stress themselves that included long hours, frequent travel to other countries, and particularly my own concern about the impact I was having were all taking a real toll on me.

Finally, after sharing with him for a while what was happening in my life, I asked him, “Well, how are you doing, Fred?” In response, he said almost matter of factly, “Well, actually Bob, I’m dying.”

Since we were only in our thirties at the time and he was such a lively force— even then while he was speaking with me— he caught me completely off guard, and I said in an incredulous voice, “You’re dying? What do you mean, ‘you’re dying?’”

“Well, Bob, I have something called ‘astrocytoma,’ a rare form of brain cancer. My mother thinks I am going to experience a miracle, but you know when you are dying, and I’m dying, Bob.”

It took me a while to digest this, so we were both quiet for some time, and then finally I asked, “Where are you calling from Fred?” He responded, “Misericordia Hospital in Philadelphia.”

I was surprised. He wasn’t in New York City. He was actually near me for some reason. So I said, “Misericordia Hospital? Why you are only about forty minutes from where I live. Would you like me to visit?”

“Would it be a big deal?” he asked. “No. Not at all,” I told him. “Well, when are you coming?”

“Right now,” I responded with emphasis.

I went downstairs, quickly briefed my wife on the situation, told her I’d be gone for several hours, hopped in the car, and drove into Philadelphia.

After I arrived and was in the room for a few moments, I realized that even though he was convinced he was dying, he was still the same outrageous guy who lived up the street from me in Queens, New York City. As a result, I knew he would expect me not to be any different with him given his situation. I must have had this firmly planted in my mind, because when I asked him what his symptoms were and he told me he had two particularly irritating ones— he couldn’t hold his water so he had to wear a diaper, and he had lost his short- term memory so he couldn’t remember anything at all about the two weeks he had already been here in the hospital— I responded, “Well, that loss of memory is tragic!”

Image credit: “Man-Guy-Hat-Grass-Dried-Sky-Clouds-Sunlight” by StockSnap. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image credit: “Man-Guy-Hat-Grass-Dried-Sky-Clouds-Sunlight” by StockSnap. CC0 via Pixabay.In response, he looked puzzled and asked, “Why is my loss of memory of what has happened here tragic?” To which I quickly responded, “Because you don’t remember me sitting here by your bed for six hours each day for the past couple of weeks.”

For a moment he looked startled and then said something to me with such colorful language that I still laugh thinking about it. My comment accomplished what I felt was needed at that moment. He had probably been faced with friends and family who were so caught up in the tension and severity of the situation that they weren’t of much help to him. I could see from his facial expression and more relaxed demeanor in bed that he knew he could chat freely with an old friend who he wouldn’t have to reassure, as is the case with many people when they are faced with someone in their interpersonal circle going through a serious, traumatic situation as Fred was.

Once we had settled in and got caught up to date on his condition and both our lives since we had last seen each other, he asked me a question that I first thought was a simple throwaway inquiry: “Well, what have you been doing that has been especially important over the past several years?” Since during both the phone call and the first hour of our visit we had already gone into depth about what had been happening, I assumed he was referring to key accomplishments that I was proud of and so I began listing them.

He waved a hand of dismay at me and quickly let me know I wasn’t responding to what he was interested in and told me. “No. No. Not that stuff. The important stuff.”

“I am not sure what you are referring to then, Fred?”

“Bob, the important stuff.” He said these four words slowly, as if he were speaking to someone who spoke English as a second language and needed time to translate in his mind what was being communicated before answering it. Then, he started to tick off a number of questions:

Tell me about the quiet walks you take by yourself each day.

What museums do you belong to?

What books have you read and movies have you seen recently?

Where do you go fishing?

Tell me about your circle of friends and what are their psychological voices they provide for you so you don’t go astray?

You know, the important stuff.

I must admit, I sat there stunned. Here was someone who was dying and soon according to his sense of things would no longer be able to enjoy life as I should be doing, and he was teaching me about living, self- care, and not forgetting to live life to the fullest while it was there.

After I spoke about the renewing and fun things I was involved in as well as the people that gave me life in different enriching ways, he said, “I did want to ask you one more thing.”

“What is it, Fred?”

“Well, as I mentioned, I am dying, but I’m not afraid.”

“You’re not?” I asked.

“No. But I feel that shortly I will be entering a large silence, and I remember that you faithfully take time out each morning in silence and solitude and wrapped in gratitude. If you could tell me what happens in your periods of silence, I think it would help me die.”

As he had intimated, he did die several months after that, and I will never forget this interaction. It reminded me more forcefully than anything else that I needed to develop a self-care program for myself that was realistic, touched all aspects of my life, was well thought out, and immediately implemented in some way.

I began to realize that even if exercise only involved a quiet walk each day, I would benefit. Too often, the grayness I and others feel after work is not the result of something untoward happening during the day but the poor air circulation in some of the buildings and offices in which we work. A short walk each day would help with this.

I could also think more intentionally about the food I was eating to ensure that I wasn’t just grabbing whatever was around.

I needed to think through who was in my circle of friends and what different “voices” were present to help me remain encouraged, awake, flexible, and hopeful.

And finally, in preparing a self- care program for myself that touched all the bases, I needed to ensure that I had quiet time to renew, reflect, adjust, be in touch with myself, and simply breathe rather than taking in air and life in gulps.

As I drove home after visiting my friend Fred, and at later points in life, I also appreciated even more that one of the key psychological fruits of self- care, which included quiet time and good friendship, is a fuller appreciation of who I was becoming through the different situations and developing times of my life.

Featured image credit: “active-adult-animal-colors” by Fancycrave. CC0 via

Pexels.

The post A short walk per day: a look at the importance of self-care appeared first on OUPblog.

Avoiding World War III: lessons from the Cuban Missile Crisis

An American president, recently made aware of a new potential nuclear threat to US cities, declared that any nuclear missile launched against any nation in the western hemisphere would require “a full retaliatory response.” The chair of the House Armed Services Committee argued that the United States should strike “with all the force and power and try to get it over with as quickly as possible.” The US Air Force chief of staff asserted that “we don’t have any choice except direct military action.” Meanwhile, leaders on the other side accused the United States of “recklessly playing with fire” and “taking a step along the road of unleashing a thermonuclear world war.” Many Americans were frightened, and a White House counsel told his deputy to “find out all you can about the bomb shelter under the White House.”

Given the headlines about the nuclear and missile capabilities of North Korea, these statements may seem uncomfortably familiar. Actually, they were drawn from the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, which one historian called “the most dangerous moment in human history.” Nevertheless, this crisis did not lead to World War III. In fact, within a week US President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had moved decisively toward a compromise that met each leader’s essential needs: for Kennedy, the removal of the Soviet missiles from Cuba; for Khrushchev, an American pledge not to invade Cuba. When Khrushchev appeared to raise the stakes by demanding the removal of US Jupiter missiles based in Turkey to his original proposal, Kennedy’s advisors were strongly opposed. Kennedy, however, was determined to avoid war and so in a secret meeting with his more “doveish” advisors, he obtained their agreement the Turkey-Cuba “trade” as a secret codicil to the public agreement. That meeting, and that codicil, remained a well-kept secret for over 25 years, which led many Americans to believe—wrongly—that Kennedy had resolved the crisis by uncompromising determination and “standing tall.” (Over the next decade, that erroneous “lesson of history” would lead Lyndon Johnson—who was not at the secret meeting—to disaster in the jungles of Vietnam.)

…the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, which one historian called “the most dangerous moment in human history.”

So what are the real lessons of the Cuban Missile Crisis? First, both leaders were very much aware of the consequences of misjudgment. As the crisis began, Khrushchev told the Communist Party Presidium that “we do not want to unleash a war, we only wanted to threaten them, to restrain the USA with regards to Cuba… The tragic aspect is that they might attack and we will repulse it. It might turn into a big war.” And at the height of the crisis, Kennedy remarked to his press secretary, “Do you think the people in that room realize that if we make a mistake, there may be 200 million dead?”

Second, both leaders were able to get outside themselves and consider the situation from the perspective of others. Early on, Kennedy acknowledged that most US allies “think we’re slightly demented on this subject [of Cuba].” And during the later discussion of whether the US should agree to remove the missiles in Turkey, he remarked that “most people will regard this as not an unreasonable proposal,” later adding that if it were rejected, “then I don’t see how we’ll have a very good war.” In a letter to Kennedy, Khrushchev urged that both leaders consider each other’s perspective:

“Just imagine, Mr. President, that we had presented you with the conditions of an ultimatum which you have presented us by your action. How would you have reacted to this? I think that you would have been indignant at such a step on our part. And this would have been understandable to us.”

Finally, both leaders were able to put aside concerns of “honor” and ignore pressure from their generals. When one general criticized Kennedy’s choice of a “quarantine” as “a pretty weak response” that “would lead right into war” and then taunted Kennedy that “You’re in a pretty bad fix at the present time,” Kennedy refused to take the bait, instead replying coolly that “You’re in there with me—personally.” Khrushchev later recalled that his military advisers “looked at me as though I was out of my mind or, what was worse, a traitor.” He then added haunting words of wisdom that echo down through the 55 years since the crisis: “What good would it have done me in the last hour of my life to know that though our great nation and the United States were in complete ruins, the national honor of the Soviet Union was intact?”

Featured image credit: Map created by American intelligence showing Surface-to-Air Missile activity in Cuba, 5 September 1962 by Central Intelligence Agency. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Avoiding World War III: lessons from the Cuban Missile Crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Can marriage officers refuse to marry same-sex couples?

Freedom of religion and same-sex equality are not inherently incompatible. But sometimes they do seem to be on a collision course. This happens, for instance, when religiously devout marriage officers refuse to marry same-sex couples. In the wake of legal recognition of same-sex marriage around the world, states have grappled with civil servants who cannot reconcile their legal duties with their religious beliefs.

Some states have responded by giving priority to same-sex equality. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the courts ruled that same-sex equality outweighed the religious beliefs of a registrar who refused to register same-sex partnerships, which she considered ʻcontrary to God’s lawʼ. And in the Netherlands, the legislature recently passed a law to ban municipalities from hiring civil servants who refuse to abide by equality legislation.

But not all countries favour same-sex equality. South Africa, for instance, has inserted an exception in its same-sex marriage legislation, granting marriage officers the right to refuse to solemnize same-sex unions. Four out of every ten marriage officers in South Africa are now exempt from their legal duties, in recognition of their religious objections to same-sex marriage.

Other states are still grappling with the question or are likely to face it in the future. In the United States, for instance, a Kentucky clerk was briefly jailed after she refused to marry same-sex couples. The heart of her case, however, is still being considered by the courts. For now, it is an open question whether same-sex equality or religious freedom will prevail in the United States. In Australia, finally, the population is being asked to vote on the introduction of same-sex marriage. If the yes camp wins and same-sex couples gain a legal right to marry, Australia may well need to decide next whether registrars with conservative religious beliefs can refuse to register same-sex marriages.

“Church Wedding” by bencleric. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Church Wedding” by bencleric. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.The question raised in the title, then, does not have a straightforward answer. But we could also rephrase it in normative terms: should we allow marriage officers to refuse to marry same-sex couples? The answer to this new question depends on how we approach human rights clashes.

Different human rights surely seem to collide in the same-sex marriage case. But we could wonder if the conflict is inevitable. We could try to escape it in two ways. We could first argue that marriage officers are under a general duty to obey the law, without exception. On this argument, civil servants are free to abide by their religious beliefs in their private lives, but not to follow them in their public function. In the public realm, we could insist, there is no room for religious exercise by registrars. And thus their freedom of religion cannot clash with same-sex equality.

But we could also favour the opposite solution. We could argue that religious beliefs do not end where the public sphere begins. Instead, we could insist that same-sex couples are not affected by a marriage officerʼs religious beliefs, because they only have a right to receive a public service and no right to delivery of that service by a particular registrar. As long as another civil servant registers their same-sex marriage, we could submit, the equality rights of same-sex couples suffer no harm at all. On this account as well, there is no conflict.

But is it really desirable to circumvent human rights clashes at all costs? Should we not accept that human rights do collide, at least in some circumstances? If we accept that real conflicts exist, we can still pursue compromise solutions. We can acknowledge that human rights trade-offs are sometimes inevitable, but insist that one right should not be sacrificed to the other. In the same-sex marriage case, we could favour a pragmatic compromise solution. We could envision an administrative system under which couples who wish to register their marriage are received at a ʻdispatchʼ desk. There, same-sex couples could be directed to willing registrar and away from those who object to same-sex marriages.

“Mormons for Marriage Equality” by Tim Evanson. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Mormons for Marriage Equality” by Tim Evanson. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Whether such a pragmatic system can still function when a large segment of all marriage officers objects, as in South Africa, is doubtful. But we might also dismiss the compromise solution for principled reasons. We could favour a principled solution on which one of the human rights in conflict is overriding, so that it trumps the other. We could balance both rights and find that same-sex equality ʻweighsʼ more. Or that freedom of religion ought to prevail. We could even decide that the balance should categorically tilt in favour one of the human rights, regardless of the circumstances. Or we could pursue a more contextual approach, on which the balance is fine-tuned in every instance. In the same-sex marriage case, however, the contextual approach appears impractical. Meaningful variations across individual cases seem unlikely. We are probably better off deciding once and for all that same-sex equality trumps freedom of religion; or vice versa.

But in other scenarios the choice between a categorical and contextual approach may remain open. For example, when a church dismisses an employee for violating religious doctrine, for instance by having an extramarital affair, two avenues are available. We could follow the US Supreme Court and insist that courts should not second-guess church decisions, even if these infringe the rights of church employees. ʻThe First Amendment has struck the balance for usʼ, the Supreme Court has famously held. But we need not agree with the American court. We may instead want to follow the lead of the European Court of Human Rights. Rather than resort to categorical answers, the European Court has ruled that the balance should be struck anew in every case. Sometimes the church will prevail. Other times, its employees will win.

Ultimately, then, human rights conflicts belie easy answers. Myriad competing approaches are available and there is ample room for reasonable disagreement. Therein may well lie the beauty of arguing about human rights clashes: contrasting opinions are often equally defensible.

Featured image credit: “SCOTUS Marriage Equality” by tedeytan. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Can marriage officers refuse to marry same-sex couples? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 8, 2017

Energy and contagion in Durkheim’s The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life

Emile Durkheim was a foundational figure in the disciplines of sociology and anthropology, yet recapitulations of his work sometimes overlook his most intriguing ideas, ideas which continue to have contemporary resonance. Here, I am going to discuss two such ideas from Durkheim’s The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (originally published in 1912 and then in English in 1915), firstly his concept of energy and secondly, his concept of contagion.

At the heart of Durkheim’s theory of religion was his account of aboriginal religion or ‘totemism.’ According to Durkheim, aboriginal life was marked by two distinct phases: the first was characterized by the different totemic groups dispersing for the purposes of hunting and gathering while in the second, the dispersed groups came together to perform the totemic ritual. Durkheim characterized the first phase of hunting and gathering as of “mediocre intensity” and as being marked by activities unlikely “to awaken very lively passions.” However, once the groups had come together a transformation occurred. Durkheim described the rite as generating “a general effervescence” [une effervescence générale], a “current of energy” [afflux d’énergie] and “a sort of electricity” [une sorte d’électricité]. Durkheim understood that societies—if they were to be sustainable—had to withstand forces of disintegration (he explored these negative energies in The Division of Labor and Suicide where anomie functioned as an implosive principle, as disorganization, disaggregation, and disconnection, and as a kind of short circuit or misfire). According to Durkheim, the performance of ritual supplied so-called aboriginal society with the resources it needed to ensure the right balance between the generation of energy on the one hand, and the consumption of energy on the other. Durkheim, of course, could not have known how apposite this line of thought would be to we humans of the Anthropocene, a term coined to mark that moment in Earth’s history when human impact on eco-systems (notably the extraction of resources for generating energy) now threatens the sustainability of all human societies.

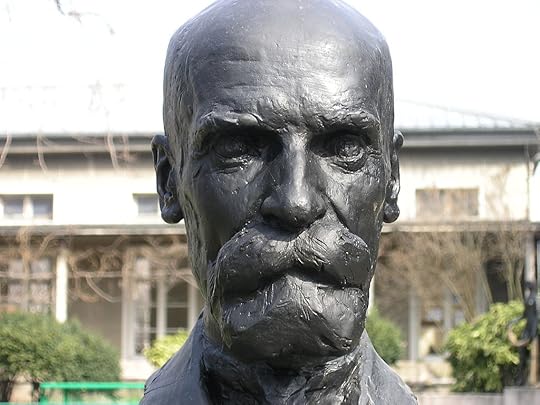

Bust of Emile Durkheim by Christian Baudelot. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bust of Emile Durkheim by Christian Baudelot. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.A second important and under-explored element of Durkheim’s theory of religion was his idea of the “contagiousness of sacredness” [la contagiosité du sacré]. New atheists and evolutionary psychologists have characterized religious beliefs as side-effects of ordinary psychological processes, and have characterized them as viruses that inhabit the mind, hijacking it for their own purposes. For the new atheists, beliefs, in order to be rational, should maximise the self-interest of the believer, and they argue that the striking feature of religious beliefs is that they do the reverse. Their promotion of epidemiological and genetic models for understanding the transmission and distribution of religious beliefs in a population may appear, at first sight, to have been anticipated by Durkheim’s use of the word ‘contagion’. However, for Durkheim—influenced perhaps by Gustave Le Bon’s (1841-1931) work on the psychology of crowds—contagion pointed to the social and emotional force of religious ideas. Ritual occasions—with their interdictions and transgressions—were precisely the moments at which the “contagiousness of sacredness” was evident.

Dead, white French professors whose work is out of fashion and whose empirical data is suspect might not seem the likeliest source of inspiration for our troubled times but, in Durkheim’s case, he is worth revisiting because his questions and the answers they furnished, are interesting. Since Durkheim, new atheists and evolutionary psychologists have made the individual the sum of their focus in the study of religions, a move which reflects a wider tendency in the humanities and social sciences to take the individual as the primary unit of analysis. One of the problems with focusing on the individual is that complex social, historical, political and economic contexts tend to be blurred or may even disappear entirely from view. Durkheim’s conceptions of energy and contagion remind us that the question of religion is a social question.

Featured image credit: title page of De la division du travail social by Emile Durkheim. Public Domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.

The post Energy and contagion in Durkheim’s The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life appeared first on OUPblog.

Biology Week 2017: 10 facts about fungus

Organised by the Royal Society of Biology, Biology Week (7-15th October) is a nationwide celebration of the biological sciences, from microbes to photosynthesis, from yeast to zooplankton. The 8th October is UK Fungus Day, so to celebrate this, and Biology Week as a whole, we’ve put together a list of things you may not know about fabulous fungi!

1. Fungi and fungus-like organisms encompass an estimated 1.5 million species. However, fewer than 5% (80,000) have been described.

2. A gruesome fact – Madurella mycetomatis is a type of fungus that erodes bones. This tropical mycosis, which spreads from a splinter wound in bare skin, can grow beneath human skin for months or years. Madurella will eventually erode bones, producing a “moth-eaten” appearance on X-rays. This disease will cause immobility and, if started in the head, neck, or chest, can prove fatal.

3. The cacao plant (the raw source of chocolate), is susceptible to multiple fungal diseases, including witches’ broom, frosty pod rot, and black pod. These diseases have been known to devastate some cacao crops. One of the most devastating instances of this was in the mid-1990s, when the fungus Crinipellis perniciosa caused Brazil’s ranking in global cacao production to drop from second to fifth place as a result.

Spores coming out of puffball fungus by Kalyanvarma. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Spores coming out of puffball fungus by Kalyanvarma. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.4. Zygomycete and ascomycete fungi have some of the most dramatic ways of spreading spores in the fungal kingdom. These fungi spread their spores through their own pressurized “squirt guns” that can shoot spore-filled balls called sporangia over distances greater than two meters.

5. Medical treatments or drugs which work for one individual may not necessarily produce the same benefits for another, and this variance in drug responses can have a genetic base. Researchers are therefore using baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as a model to calculate how genetic variation impacts the effectiveness of pharmaceutical treatments.

6. Ash dieback is a disease caused by the invasive alien fungal pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, which often has devastating consequences for the survival, growth and wood quality of ash trees.

7. Mushroom cultivation is a lot more complex to undertake than many people think. It involves adhering to precise procedures throughout, including during the selection of the appropriate species, ensuring a good-quality fruiting culture, preparation of suitable compost, and harvesting the mushrooms themselves.

8. Yeast, a type of fungus, is widely used in the brewing process for beer, and increased experimentation to meet customer demand for product diversity, has led to a greater appreciation of the role of yeast in determining the character of beer. Understanding the different properties of yeast has the potential to create new beer flavors, in addition to producing flavorsome non-alcoholic beers.

9. A large number of pathogenic microorganisms (fungal and bacterial) cause rice diseases that lead to enormous yield losses worldwide. This is troubling, because rice is a staple food for more than half the world’s population. Thankfully, over the last 20 years, extensive research has been done into the reasons for these diseases, and new management strategies are being implemented to try and combat them.

10. The earliest European description of Central Mexican mushroom rituals is that of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, the sixteenth-century Franciscan chronicler of Aztec civilization. The Aztec called the intoxicating mushrooms teonanacatl, “divine flesh” or “flesh of the gods.” According to Sahagún’s informants, when the priests and their communicants consumed mushrooms (with honey), they ate no more food but only had cacao (chocolate) drinks during the night. When the mushrooms took effect, they danced, then they wept. When the effects left them, they consulted among themselves and told one another what they had seen in visions.

Featured image credit: Fungus by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Biology Week 2017: 10 facts about fungus appeared first on OUPblog.

American personhood in the era of Trump

After the violence in Charlottesville, Virginia on 12 August, 2017, the people of the United States waited anxiously for a response from their president. Sure enough, the first response came that day, denunciatory but equivocal. He condemned the violence coming from “many sides,” a response many found dissatisfactory considering that it was not counterprotesters but the alt-right who were responsible for the death of thirty-two-year old Heather Heyer. And so, two days later, following widespread discontent with his first tepid foray, the president tried again, this time actually mentioning the people responsible—neo-Nazis and white supremacists. But the next day he once more changed course, doubling down on his initial reluctance to focus his condemnations solely on right-wing extremists. Among the torch-wielding alt-right protesters in Charlottesville were “very fine people,” he insisted.

Why was Trump so ambivalent in condemning what even many of his fellow Republicans easily denounced? There are likely many factors at play, but one that has gone mostly unrecognized is the importance of domination to Trump’s worldview and seemingly that of his supporters. In many regions in the ancient world, personhood was based on violence, physical dominance, and control over the bodies of inferiors. What do I mean by “personhood”? I define personhood as a recognition of an individual’s value that is conveyed by a community and accords to those recognized as persons rights such as protection from harm, as well as the ability to seek redress if one is harmed.

Most of us in contemporary North America think of personhood as something static—once a person, always a person—but in reality personhood can be nullified. This was very much the case in ancient Israel and Mesopotamia, where even the personhood of free males could be erased through violence, particularly if they threatened the dominance of a more powerful male. Personhood can be erased in our society, too. There a few contemporary cases from American society where this type of malleable, violence-based personhood is also present; these include the torture of enemy combatants at Abu Ghraib and police shootings of African-Americans.

Trump’s rhetoric shares a surprising amount in common with the rhetoric of ancient Near Eastern kings. Mesopotamian kings regularly described with great bombast their incomparability, magnificence, and mercilessness in trampling those who would dare attempt to rival them. One king wrote of himself: “I, Ashurnasirpal, strong king, king of the universe, unrivalled king…the king who subdues those insubordinate to him,” while also boasting of his strength and virility in language very much typical of Mesopotamian royal inscriptions (see A. Kirk Grayson, Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC [1114-859 BC], 2:194). Reliefs portray these kings as towering over vanquished enemies who appear minuscule, feeble, and feminized.

Ashurnasirpal II, British Museum, London by Yak. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Ashurnasirpal II, British Museum, London by Yak. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Like Assyrian monarchs who declared themselves to be “without rival,” Trump repeatedly points to his greatness. No one is more dominant, more impressive, more great than he is. Even his hands are “the most beautiful”; his virility, he guarantees us, is impressive. When any aspect of Trump’s purported greatness is challenged, his response is extremely aggressive and sometimes includes animalizing and/or violent language. For example, he has referred to women who challenged him as “pigs,” “dogs,” and “animals.” When he was confronted by a disabled reporter, his response was to humiliate the man publicly. He sometimes encouraged violence at his rallies and has publicly expressed support for torturing and killing not only terrorists (“animals”) but the families of terrorists. As we saw post-Charlottesville, he is uncomfortable denouncing violence unless he can in some way blame his opponents for it. This seems to be how he attempts to maintain a position of power despite having to denounce publicly the very type of social and physical dominance he clearly treasures and wishes to afford himself.

In the eyes of Mesopotamian kings, those who dared question their magnificence were unworthy of humanity—they were not just called animals, but slaughtered, mutilated, and displayed like animals. Only socially dominant males had the right to bodily integrity. Women’s bodies, slaves’ bodies, and perhaps especially rival kings’ bodies had to be publicly subordinated in order for dominant men to remain powerful and in control. While Trump has not had anyone decapitated, his rhetoric does seem to betray the same competitive view of social status—someone is either dominant or subordinate, and a man must fend off challenges to his dominance in forceful ways because of what subordination entails, which is humiliation, physical assaults, dehumanization, and even death. The infamous Access Hollywood bus tape demonstrates well that Trump sees women as subordinates whose bodies he, as a dominant male, may manipulate at will. But it is not just women Trump sees as subordinate and subject to humiliation and abuse. It is anyone, really—any rival, political, professional, social, or cultural. His reprobations fly on Twitter with a frequency that would astonish even Nebuchadnezzar. And Trump’s children have, it appears, learned well the ways of their father. Speaking of his father’s critics, Eric Trump stated: “To me, they’re not even people.”

More troubling, however, than the rhetoric of Trump or his son is Trump’s popularity. Many of his supporters apparently esteem him not despite his domination rhetoric but precisely because of it. This appears to indicate a shifting trend concerning views of personhood in American society. In the past hundred years, there had been a move toward ever more inclusive views of personhood. Children, women, racialized minorities, and animals have all seen expanded rights. However, the election of Trump and the related rise in hate groups, hate crimes, hate speech, and xenophobia seem to evince a backsliding toward a domination personhood centered in masculinity, racism, and not least of all violence.

If this assessment is correct, Charlottesville may well be just the beginning. After all, we have seen what happens when a society withdraws the protections of personhood, when being human is not enough to warrant basic rights. Racism, bigotry, white supremacy, Nazism—this rejection of broad attributions of personhood goes by various names. The resurgence of domination personhood should terrify all of us, perhaps even more than the marching of neo-Nazis or hooded Klansmen. After all, their newfound shamelessness would be impossible without it, and its influence is apparent not just on the margins of American society, but at its very core—with the presidency of Donald Trump himself.

Featured image credit: Robert Edward Lee Sculpture by Cville dog. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post American personhood in the era of Trump appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Confucius [infographic]

This October, the OUP Philosophy team honors Confucius (551 BC–479 BC) as their Philosopher of the Month. Recognized today as China’s greatest teacher, Confucius was an early philosopher whose influence on intellectual and social history extended well beyond the boundaries of China. Born in the state of Lu during the Zhou dynasty, Confucius dedicated his life to teaching, and believed he was called to reform the decaying Zhou culture.

A symbolic and controversial figure, his philosophy is primarily moral and political in nature. Confucius taught that moral order must be brought about by human action. His lessons emphasized moral cultivation, stressed literacy, and demanded that his students be enthusiastic, serious, and self-reflective. Confucius taught that all persons, especially members of the ruling class, must develop moral integrity through ritual action, expressing care and empathy in order to become a consummate person. An innovative teacher, his school was open to all serious students. Of the 3,000 students he is said to have had, only 72 mastered his teachings, and only 22 were close disciples. The legacy of Confucius survives through his teachings, recorded by his disciples in a text known as the Analects.

We’ve created the infographic below to highlight more from the life and work of Confucius. For more, follow @OUPPhilosophy and the hashtag #philosopherotm on Twitter.

Featured image: Kaohsiung, Taiwan, Kaohsiung Confucius Temple. Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the month: Confucius [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

October 7, 2017

Time for international law to take the Internet seriously

Internet-related legal issues are still treated as fringe issues in both public and private international law. Anyone doubting this claim need only take a look at the tables of content from journals in those respective fields. However, approaching Internet-related legal issues in this manner is becoming increasingly untenable. Let us consider the following:

Tech companies feature prominently on lists ranking the world’s most powerful companies. For example, on Foreign Policy’s list of “25 Companies Are More Powerful Than Many Countries” ten of the listed companies are from the tech industry, and perhaps somewhat less importantly, six of the top ten companies on Forbes’ list of the world’s most valuable brands are tech companies (with the four top spots being Apple, Google, Microsoft and Facebook);

With its more than two billion users, Facebook alone has more ‘citizens’ than any country on earth; and

No other communications media comes even close to the Internet’s ability to facilitate cross-border interactions – interactions that may have legal implications.

While statistics may be used to prove just about anything, the message stemming from the above is clear and beyond intelligent dispute: cross-border Internet-related legal issues are central matters in society and need to be treated as such in public and private international law.

“Smartphone Screen” by TeroVesalainen. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Smartphone Screen” by TeroVesalainen. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.A particularly relevant matter is that of Internet jurisdiction. The harms caused by the current dysfunctional approach that international law takes to jurisdiction are as palpable as they are diverse. The territoriality-centric approach to jurisdiction causes severe obstacles for law enforcement’s fight against both traditional and cyber-crime, it undermines the protection of important human rights, it amounts to an obstacle for e-commerce, and it creates uncertainties that undermine the stability online with an increased risk for cyber conflict as the result. Thus, Internet jurisdiction is one of our most important and urgent legal challenges. And we all need to get involved.

No more ‘regulatory sleep-walking’:

There are many notions regarding jurisdiction in general, and Internet jurisdiction in particular, that are widely relied upon in the academic community and beyond. The two key sources for those notions are the (in)famous 1927 Lotus case, and the widely cited, but poorly understood, Harvard Draft Convention on Jurisdiction with Respect to Crime 1935 – both seen to put the supremacy of the territoriality principle beyond question. With a somnambulant-like acceptance, these authorities are treated as clear, exhaustive, and almighty.

However, those who have truly studied jurisdiction in detail generally take a different view. For example, Ryngaert and Mann have both questioned whether the Lotus decision remains good law.

A new paradigm:

I believe that we must move beyond the current territoriality focused paradigm of how we approach jurisdiction, and have advanced an alternative jurisprudential framework for jurisdiction: In the absence of an obligation under international law to exercise jurisdiction, a state may only exercise jurisdiction where:

There is a substantial connection between the matter and the state seeking to exercise jurisdiction;

The state seeking to exercise jurisdiction has a legitimate interest in the matter; and

The exercise of jurisdiction is reasonable given the balance between the state’s legitimate interests and other interests. That work is, however, just a starting point for further discussions.

“Office” by StartupStockPhotos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Office” by StartupStockPhotos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Not just a matter for Internet lawyers:

Internet jurisdiction is not just a matter for Internet lawyers, it is not just a matter for the public international law crowd, and it is not just a matter for those inhabiting the domain of private international law – Internet jurisdiction is a key issue in all of these fields. And, importantly, it is a matter we will only be able to address when the experts from these fields join forces and approach jurisdiction in an open-minded manner.

To this we may add that addressing Internet jurisdiction is not just a matter for the academic or legal community. It is for us all— industry, government, courts, international organisations, civil society, and the academic community— to help achieve useful change. Furthermore, those engaged in capacity-building initiatives must recognize that they need to incorporate capacity building in relation to a sound understanding of the jurisdictional challenges and solutions.

Much work lies ahead. But it is crucially important work and we must now turn our minds to these issues to which we, for far too long, have turned a blind eye.

Featured Image Credit: “Hands and Laptop” by Jane Mary Snyder. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Time for international law to take the Internet seriously appeared first on OUPblog.

The history of the library

Our love of libraries is nothing new, and history records famous libraries as far back as those of Ashurbanipal (in 7th-century BCE Assyria) and Ancient Greek Alexandria. As society and culture have progressed, so too have our libraries. Even epochs such as the Middle Ages (known erroneously as the “Dark Ages” for its lack of learning and culture) had their share of renowned book collections. Indeed, the later Renaissance was only possible because of these stores of learning, preserved for centuries. The very concept of the Renaissance predicates access to a library, because if Antiquity were to be reborn, the guidelines for this rebirth had to emerge from research into the culture of Greece and Rome–which had to take place in a well-stocked library.

Today, libraries are celebrated all over the world, for their democratisation and dissemination of knowledge and literature. With this in mind, we’ve compiled some fascinating facts about the history of the library–from Cheng dynasty China to the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz.

In 26 BCE, Emperor Cheng (r. 33–7 BCE), with mounds of writing on bamboo and silk piled up inside and outside the palace precincts, launched a project that would begin China’s proud tradition of state library development and bibliographical scholarship over the next two thousand years. Stewards were sent to gather lost writings throughout the land, and a team of subject specialists led by Liu Xiang (79–8 BCE) were tasked to collate all the assembled bundles of bamboo slips and scrolls of silk with a view to establishing sound texts (a precursor to today’s subject classifications).

Libraries were a common fixture of many towns in the Roman Empire. There are relatively few records however, as many were destroyed by fire. In 356, the emperor Constantius II created a scriptorium (a room specifically set apart for reading and writing) that apparently serviced an imperial library, but it was destroyed by fire in 475. There was also a substantial collection in the Serapeum of Alexandria (an Ancient Greek Temple), but this too was destroyed by fire in 391.

Books in medieval libraries were acquired in three ways: by being produced in a monastic scriptorium, by donation or bequest, or by purchase. In 1289 the library of the University of Paris contained 1,017 volumes which, by 1338, had increased to 1,722—an increase of about 70%. The development of the universities affected the content, appearance, and production of books as well as their price (something that was also much affected by the use of paper rather than parchment). The positive effects of the printing revolution were not immediate however, and it is not until about 1500 that we begin to see its real revolutionary impact.

The most luxurious library of late medieval Hungary was that of King Matthias Corvinus (r. 1458–1490): the so-called Corvinian Library in the royal palace of Buda. Many of its manuscripts were copied and illuminated in Renaissance Florence, but the King established a scriptorium in Buda as well. The library suffered dispersion during the Turkish invasion in the early 16th century, but it is estimated that it contained around 200 manuscripts. They are now kept in more than twenty libraries around the world, including libraries in Budapest, Cambridge, Florence, New York, Venice, Vienna, and Wolfenbüttel.

Libraries were an incredibly important tool for the early American colonists. Faced with choices about what to bring across the Atlantic, many settlers privileged their books. Overall, libraries in this early era of colonization emerged largely from the efforts of individuals, one notable example being John Winthrop II. When Winthrop journeyed to America in 1631, he brought with him an impressive library that he assiduously added to over the years: by 1640, it was reputed to contain 1,000 volumes, making it the largest library in seventeenth-century British America. Winthrop’s collection was also unique in its emphasis on science, one of the owner’s intellectual passions.

Did you know that the philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz had a profound impact on library science? Leibniz discussed the order of books in a library in Nouveaux Essais sur l’Entendement humain, composed between 1703 and 1705. He pointed out one of the major difficulties encountered by librarians: since “one and the same truth may have many places according to the different relations it can have, those who arrange a library very often do not know where to place certain books”. In this regard, Leibniz maintains that the traditional, convenient, and therefore more applied “faculty system” that is, the division based on the four university faculties of theology, jurisprudence, medicine, and philosophy, “is not to be despised.”

Featured image via Pixabay .

The post The history of the library appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers